Andrew Sullivan's Blog, page 412

December 13, 2013

Before Newtown And Columbine

S.T. VanAirsdale reports from Stockton, California, where the first mass school shooting of the cable-news era took place a quarter century ago:

Much else has faded about the Cleveland [Elementary School] shooting since it seized the American imagination – since Time grimly proclaimed “ARMED AMERICA” in a cover story three weeks after the massacre and, later in 1989, Esquire painstakingly deconstructed the last days of Patrick Purdy. No less a pop cultural eminence than Michael Jackson invited himself to Stockton on Feb. 7 of that year, where his attempts to cheer up the Cleveland community only meant more emergency vehicles, more police, more helicopters and more campus bedlam that just recalled the panic that Jackson had sought to assuage in the first place.

Several child survivors are now gun enthusiasts:

Brandon Smith, now 34, is a paramedic for a private ambulance company in Stockton. He credits his time spent in the hospital as a Cleveland victim with igniting an interest in doctors and nurses. By the time he was 12, he’d resolved to become a medic. He speaks to few people about being shot 25 years ago or about the arsenal he has acquired as an adult. “In fact,” he says, “I own the very gun I was shot with – an AK-47.”

Smith explains how the rifle complies with all state and federal laws – domestically manufactured, 10-round detachable magazine with a modified manual release – and that he doesn’t see anything macabre or strange about buying it. It’s simply the gun he likes to fire off at the shooting range. “It’s not like only crazy people are going to like that gun, or people who want to kill others are going to be attracted to that gun,” he says. “It’s just a firearm.”

(Hat tip: Slate)

Unable To Conduct Himself, Ctd

A reader writes:

I saw your post on Bernstein, and Gottlieb’s remarks, which could not have been more incongruent with the video. I have a doctorate in orchestral conducting from the #1 ranked conducting program in the nation, so I’m not a layman on this topic. Watch the video again. And notice the camaraderie. The respect. The ease with which he rehearses them. This kind of rapport doesn’t exist anymore, except at off-the-radar orchestras in mid-level locales and certain lucky academic institutions. The top-level orchestras have become sanitized from this kind of warm, collegial, sometimes jocular style of rehearsing, partially because of the extreme reaction to the angry dictator-conductor (think crazy hair, and the yelling white European male). But also because now, the skill level of professional orchestral musicians is so ridiculously high. You’d have to look to Navy SEALs or brain surgeons to find the same level of expertise nowadays. That’s not hyperbole.

Yes, Bernstein was a narcissist, in his own right. But don’t throw out the baby with the bath water. Seriously. The cure for our sustained disinterest in anything requiring more than seconds of our time is the depth and richness of classical music, literature, film, and dance. Just spend two minutes watching this upending performance of Bernstein conducting Vienna in Sibelius’ Symphony No. 2, which will never be rivaled.

Another:

I was lucky to do copying and editing work for Bernstein late in his life and spent a good deal of time at his apartment at the Dakota as well as his house in Fairfield.

I have stories, but would prefer not to air dirty laundry. Yes, not surprisingly, he was sometimes childish, inappropriate, and self-centered. But he was also kind and learned, and loved teaching. Unlike some other men who liked to claim how he hit on them, he always treated my like my nice Jewish grandfather. Perhaps he knew I wasn’t interested. Perhaps he wasn’t interested. But I’d also like to point out that as a conductor, specifically when he was doing his later Mahler cycle, he was fucking brilliant. The moments when handlers disappeared and we talked, or simply watching him in rehearsal with the NY Phil are some of my most treasured memories. Getting a bit choked up while telling me which works he wrote at his studio desk in Fairfield is hard to beat at a moment, especially when those works include Chichester Psalms.

For all of his compositional unevenness he was incredibly skilled and sometimes devastatingly hit the mark in his work. That he never received the Pulitzer I believe irked him to no end and probably was due to a combination of his fame and their jealousy, his ability to suck all of the air out of a room, and – worst of all – being looked down upon by the establishment because he also wrote musical theater. He lived through a “Cold War” in composition, the ascendancy of the modernist and serialist composers and a near-total separation between pop and classical music. It was not easy being Bernstein then. He was always told he did too much and wasted his talents, as opposed to how amazing it was that he did so many things brilliantly. When I look at the number of composers who have received the Pulitzer in the last 3 decades since he died I have to wonder. It’s crazy that he did what they are doing now – combined high and populist art, kept the tonal tradition alive – in a far an earlier time, when it was more detrimental to your reputation, and often with far more skill and sophistication they they did. And yet… they have the award, not him. This goes for both concert and theater music. The score to West Side Story not better than Rent? Are you kidding?

I do agree that later in life, after his wife’s death, he did lose his moorings a bit. There weren’t enough people around him to tell him no. That always left me profoundly sad. That he was difficult and narcissistic isn’t a trait unique to him. Ever meet a rock star, a conductor, or – worse – a politician?

Keeping Your Kid Safe From Guns

Some advice from Justin Peters:

There are a few simple rules that, if followed, would almost entirely eliminate unintentional child shooting deaths. Always keep your gun on your person or at arm’s length. If it is not on your person, it should be in a gun safe, preferably unloaded. When you are unloading the gun, check to see if the chamber is clear. Never let your children use a gun unsupervised.

These are not controversial rules. They’re common sense. But rather than make them explicit, we tend to assume that gun owners understand them. That’s the first faulty assumption. It begets others.

He wants to pass child access prevention (CAP) laws to enforce those rules:

CAP laws provide criminal penalties for parents and guardians who unlawfully allow children to access their guns without supervision, either under direct permission or through unsafe gun storage practices. These laws vary in scope and severity from state to state. In Massachusetts, for instance, a person can be held liable for negligent firearm storage even if the gun is unloaded. In Mississippi the law is only triggered if a parent or guardian “knowingly” allows a minor to possess a restricted weapon.

CAP laws get little attention from gun control advocates. They are no one’s top legislative priority. As far as I can tell, there are no organizations exclusively devoted to lobbying in their favor. And yet they still manage to attract a surprising amount of support. Twenty-seven states and the District of Columbia have some form of CAP law, and some of these states—including Oklahoma and Utah—are among the reddest on the map. In a nation where it is difficult to pass any firearms restrictions whatsoever, CAP laws are among the most palatable gun policy solutions around.

Face Of The Day

A man pours water on the head of a pregnant woman who nearly fainted during a food distribution of the UN World Food Programme (WFP) near a camp for internally displaced persons in Bangui on December 13, 2013. More than 600 people have been killed in the sectarian violence tearing though the Central African Republic in the past week, the UN said today. The resource-rich but poverty-stricken majority Christian country was plunged into chaos following a March coup by mainly Muslim Seleka rebels. A fresh wave of violence enveloped the country on December 5, prompting French troops to deploy in a bid to stop communal strife that had sparked global alarm and talk of a possible genocide. By Sia Kambou/AFP/Getty Images.

Languages The Internet Doesn’t Speak

Keating notes that the web will play a key role in determining which of the world’s languages survive:

It’s not news that we’re currently in a period of mass linguistic extinction. One of the world’s languages falls out of use about every two weeks, and about half of those remaining are in danger of extinction this century. But Andras Kornai of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences believes these numbers actually understate what’s happening by failing to account for the fact that very few of the world’s languages are developing any presence online. …

All in all, Kornai’s survey on languages online estimates that at most 5 percent of the world’s 7,000 active languages will be capable of ascending. It’s fair to wonder just how much of a tragedy this really is: While we’re losing some local identity, more people around the world are now able to communicate with one another than ever before. It is safe to say, however, that we’re at something of a key turning point in the history of culture.

Caitlin Dewey remarks on efforts to keep these languages alive:

Plenty of organizations, including Wikipedia and the Alliance for Linguistic Diversity, have devoted resources to that cause: The ALD has a massive crowd-sourced encyclopedia of endangered languages, complete with sample texts in tongues such as Nganasan (500 speakers, Russia) and Maxakali (802 speakers, Brazil). Wikipedia has an “incubator” to encourage projects in new languages (or very old ones). Kornai thinks the Wikipedia project has potential — in fact, he argues that endangered languages need a core of digital fanatics, like Wikipedia moderators or educational app developers, to survive.

But that isn’t enough to keep a fading language viable in the long term, particularly if there’s another, more dominant language that’s easier for people to use online. Even if you have a killer Cherokee wiki, for instance — which, it turns out, some people do – you’re not necessarily going to be able to Google or Facebook or tweet in that language.

The Great American Artform

Ads:

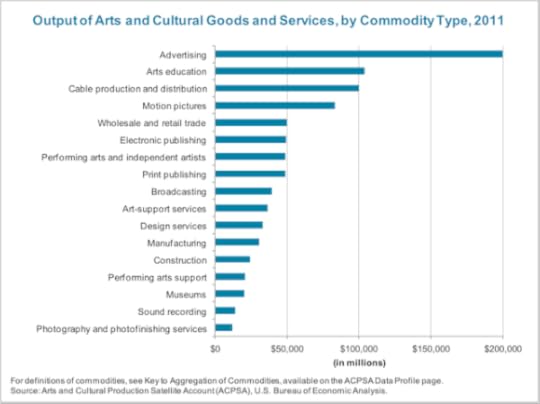

The preliminary report, a joint effort of the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis and National Endowment for the Arts, reveals that advertising dwarfs the economic clout of every single other creative endeavor, followed by arts education in a distant second place. The report finds that the total size of the arts and culture economy is 3.2 percent of GDP, coming in at $504 billion. In the broader leisure economy, the report notes, this sector supplants travel and tourism, which clocks in at 2.8 percent of GDP. The report also finds that the national economic recovery has lagged, jobs-wise, in the culture sector.

That advertising is a major fiscal engine should of course not be terribly surprising, but the small size of the “Independent artists and performing arts” ($48.9 billion) compared to the “Arts education” category ($104 billion) should provide some pause as far as the economic linkage that exists between arts education and the production of what we consider high (or “fine”) art: teaching art — i.e. the promise of art — is a more lustrous pearl than the actual messy business of producing it.

Lazy Charity

Ken Stern urges us to do our homework and get smart about donations:

In 2010 Hope Consulting, a San Francisco–based consultancy, undertook one of the most comprehensive surveys ever of donor habits. It found that two-thirds of all donors report doing no research at all on their charitable contributions each year, and just 5 percent do two or more hours of research. On average, Americans spend about four times as long to research television purchases (four hours) and eight times as long researching computer purchases (eight hours) than they do with more expensive investments in charities (one hour). Indeed, some of the latest research suggests that Americans may subconsciously avoid finding out the facts in fear of undermining the “warm glow” they get from giving.

Instead of doing research, Americans give out of habit: Almost 80 percent of all gifts are labeled as “100 percent loyal,” meaning most people give to the same familiar brands year after year. Donations flow to alma maters, or to a friend’s charity, or to the charity that is easiest to give to through work. That’s a big reason why the list of America’s largest charities has remained remarkably inert over the last 40 years—because they’re rewarded for familiarity rather than any measure of effectiveness or innovation.

Among his advice:

Go for a high-impact donation. This might sound like it’s from the “No Kidding” Academy of Donor Advice. But in fact only a small subset of donors—representing 16 percent of all donors and 12 percent of all donations—define themselves as “high impact,” supporting the charities that create the most social good. The rest fall into categories such as “Repayers,” who give to their alma maters, “Personal Ties,” for people who give to their friends’ organizations, or “Casual Givers,” who give to well-known nonprofits through payroll deductions or who buy a table at a charity event. All these reasons for giving are completely unrelated to rewarding the most effective charities. Until you think and act like a high-impact donors, you’ll get less than what you pay for.

Have We Given Up On The Syrian Rebels?

The US and Britain have suspended aid to rebels in northern Syria after learning that the warehouses holding the supplies have been taken over by jihadists. With that in mind, Dan Murphy eulogizes Obama’s Syria policy:

That it was on life support has been clear for a long time. But with the routing of the US-backed Free Syrian Army (FSA) from its headquarters recently by Islamist rebel fighters, the plug should be pulled. The US can insist that its suspension of non-lethal aid (and a trickle of weapons) to the FSA via a group called the Supreme Military Council (SMC) is temporarily all it wants, but the momentum now belongs to Islamist rebels who are as hostile to US interests as they are to those of Bashar al-Assad. Meanwhile, Assad’s military has won a series of victories around Damascus and Syria’s second city, Aleppo, and its evolving alliance with the Lebanese Shiite military Hezbollah has strengthened both sides. …

What are the options going forward for a real US strategy in Syria – where the conflict continues to cast a shadow of destabilization over Lebanon, Iraq, Jordan, and to some extent Turkey?

None particularly obvious. Direct military involvement is so unlikely as to not worth being considered. A major outreach to the non-Al Qaeda Islamists, coupled with a major diplomatic effort to convince the Saudis to arm-twist their clients into compromise? Perhaps that’s a way forward – though it would mean the US is supporting a group that is pushing Sunni hegemony in Syria, a country with meaningful Christian, Shiite, and Alawite minorities. The US government’s mantra of support for democracy would seem to preclude that.

What else? No good options are left. In retrospect, the US might have held its nose and armed moderate rebels that could stand up to the Islamist armies. But the rebels friendly to US interests were never very obvious or well organized. The notion of a national level “Free Syrian Army” with meaningful command and control at anything beyond the local level has been mostly aspirational.

Bob Dreyfuss agrees:

It’s pretty much a complete and total collapse of the American efforts to back opposition to Assad, whose own forces have put together a string of military victories since the spring, retaking important strongholds and using aid from Russia, Iran and the Lebanese Shiite group, Hezbollah, to do so.

Tony Blinken, the top White House foreign policy official and former aide to Vice President Joe Biden, told a conference that the radicalization of the conflict and the strength of the Islamists might convince everyone involved from the outside to seek a peace accord. But a closer reading of Blinken’s comments seemed to indicate that he was suggesting that Russia would feel compelled to lessen its support for Assad because it fears that the Islamist rebels—who include a number of extremist Chechen fighters who’ll try to wreak havoc in Russia when they return. …

Fact is, the United States and Russia have a joint interest in suppressing and eliminating the Islamist rebels. And that’s it. One danger is that Saudi Arabia, which is apoplectic about the impending US-Iran accord and which is equally angry about the US-Russia diplomacy over Syria, may be pouring funds into the non–Al Qaeda Islamist radicals, such as the Islamist Front, just to give the United States a black eye. If so, Washington had better read the riot act to Riyadh.

Gayle Tzemach Lemmon faults Obama’s inconsistency for the disarray:

All along, President Obama’s hesitancy has called into question what, exactly, American policy is and was in Syria. In the summer of 2011, Obama said that the “time has come for President Assad to step aside.” Yet, the actual policy of the U.S. in Syria has looked more like containment than regime change. Joint Chiefs Chairman Gen. Martin Dempsey this year publicly recommended using the military to keep the conflict from spreading outside of Syria, but not to intervene with direct military force. The administration’s decision this fall to abort military strikes in favor of negotiating a deal with Assad to destroy his chemical weapons stockpiles only furthered that impression.

“It is not at all clear what our objective is,” says Amb. Dennis Ross, who served as special advisor on Iran for Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton. “Without an objective you can’t identify what are the appropriate means to mobilize. We don’t have any leverage.”

Ross sees our engagement in Syria evolving into a counterterrorism policy:

For his part, Ross says that the threat of foreign fighters plus the desire to avoid boots on the ground make counterterrorism an increasingly possible path. “We have been very reluctant to use force. CT means many different things, including training those forces we can support. It also means drones. We do that in Yemen against al-Qaeda. Are we headed toward that in Syria? Could be.”

But that again, Ross argued, raises the question of what exactly is America’s aim in Syria? Is it to keep the country together and fulfill the June 2012 Geneva Declaration’s goal of creating a “transitional governing body” that “would exercise full executive powers?” Or is it simply to protect the United States from the potential threat posed by extremist fighters energized by the battle to oust Assad? “CT is still a means, not an objective,” he said.

Update from a reader:

It just amazes me that we’re still seeing articles basically trying to figure out how exactly the US screwed up the whole Syria problem. Because that implies that we actually at some point had a real possibility at deciding how it would turn out. Why anybody would think that after the experiences of the past decade is just unfathomable to me. We waltzed into two different nearby countries and basically ran them for years, and we still couldn’t do much to dictate the conditions of those countries. If that sort of engagement doesn’t give us a real say about things, than why should we expect that a lighter intervention would be any more successful?

For various long-term and complicated reasons, the region is a giant political/sectarian/religious mess being fought over by a bunch of people who could not care less about the interests or desires of the US. Nothing we can do will change that. More decisiveness by Obama wouldn’t have changed that. Sure, we could go in and remove Assad if we really wanted, but even that wouldn’t give us much of a say on how the country ended up being run in the long term.

There were never any good options for the US here. There was no winning strategy waiting to be discovered. People just need to accept that things happen in the world that even the might US military can’t control.

Amen.

(Photo: Fighters loyal to the Free Syrian Army (FSA) pose with their weapons in a location on the outskirts of Idlib in northwestern Syria on June 18, 2012. By D. Leal Olivas/AFP/Getty Images)

Running Against Their Own Ideas

Chait watches as Republicans “turn from denouncing the health-care law for its lack of high-deductible insurance to denouncing the health-care law for its high-deductible insurance”:

Insurance plans with low premiums and high deductibles were a major centerpiece of conservative health-care thinking. Until quite recently, conservatives seemed to believe that Obamacare prevented such plans from existing, which was totally false. As they’ve come into existence, conservatives have transitioned seamlessly into denouncing these plans for their horrible, high deductibles.

Episodes like this one have grown so familiar that they’ve lost all capacity to surprise. Conservative health-care-policy ideas reside in an uncertain state of quasi-existence. You can describe the policies in the abstract, sometimes even in detail, but any attempt to reproduce them in physical form will cause such proposals to disappear instantly.

Drum piles on:

Republicans have spent years claiming that their preferred health care solution involves a combination of high-deductible health plans and tax-free HSAs. The idea is that your HDHP handles catastrophic illnesses, while the money you use for routine medical care isn’t taxed, which puts it on a par with employer health care. But their idea of “high deductible” has always been on the order of a few thousand dollars. A bronze plan under Obamacare typically has a deductible of $5,000 or more ($10,000 or more for a family). And while Obamacare doesn’t feature tax-free HSAs, it does feature annual premiums with much of the cost offset via tax credits. Conservatives will never admit this (and maybe not liberals either), but the end results aren’t really all that dissimilar.

Jonathan Cohn looks at where conservative and liberal health care policies diverge:

“Giving consumers the choice of narrower physician networks and higher deductibles, in exchange for lower premiums, is a good thing,” [Avik] Roy says. “The problem with Obamacare is that people are trading narrower networks and higher deductibles for higher premiums. And that’s because of all the other stuff that Obamacare does to the insurance market.”

Precisely. The real difference between left and right now is the “other stuff” Obamacare does to the insurance market. And what’s that other stuff? It’s “guaranteed issue” and “community rating”—the requirements that insurers sell to anybody, regardless of pre-existing condition, with varying rates or benefits. It’s the creation of a minimum standard for coverage, so that all plans must cover at least 60 percent of the typical person’s medical bills and include a set of “essential health benefits” from hospitalization to mental health to rehabilitative services to maternity care. It’s the availability of generous tax credits, available to people with incomes as high as four times the poverty line and worth thousands of dollars a year in some cases. And it’s the individual mandate—the requirement that people pay a fine if they decline to get coverage when it is both available and affordable.

Ezra wonders what healthcare policies Republicans could possibly support:

One option was for Republicans to build as many of their ideas into the Affordable Care Act and force Democrats to take partial responsibility for these hideously unpopular, but fairly reasonable, ideas. They didn’t do that. Then Democrats picked some of the ideas up anyway. So Republicans again had a chance to focus their fire on the parts of the law they hated — like the Medicaid expansion — in the hopes of moving the health-care system in the direction they prefer. Instead, they’re aiming at the least popular policies in the law — which just so happen to also be the exactly policies that they support.

We’ll see whether Obamacare withstands the onslaught. But either way, once the assault is over, what kind of health policy will Republicans be left with? How can they propose anything that will cancel plans or raise deductibles or tighten networks? How can they propose anything at all?

Mental Health Break

Andrew Sullivan's Blog

- Andrew Sullivan's profile

- 154 followers