Andrew Sullivan's Blog, page 409

December 16, 2013

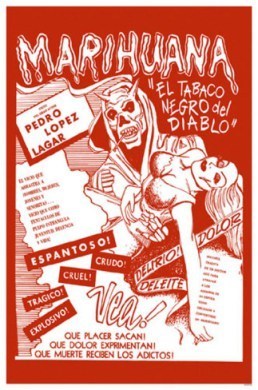

Why Do We Call It “Marijuana”?

It was “cannabis” throughout the 19th century. Then came the Mexican Revolution:

Following the upheaval of the war, scores of Mexican peasants migrated to US border states, bringing with them their popular form of intoxication, what they termed “mariguana.” Upon arrival, they encountered anti-immigrant fears throughout the U.S. Southwest – prejudices that intensified after the Great Depression. Analysts say this bigotry played a key role in instituting the first marijuana laws – aimed at placing social controls on the immigrant population.

In an effort to marginalize the new migrant population, the first anti-cannabis laws were targeted at the term “marijuana,” says Amanda Reiman, a policy manager at the Drug Policy Alliance. Scholars say it’s no coincidence that the first U.S. cities to outlaw pot were located in border states. It is widely believed that El Paso, Texas, was the first US city to ban cannabis, when in approved a measure in 1914 prohibiting the sale or possession of the drug. …

But nobody played a larger role in cementing the word in the national consciousness than Harry Anslinger, director of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics from 1930 to 1962. An outspoken critic of the drug, Anslinger set out in the 1930s to place a federal ban on cannabis, embarking on a series of public appearances across the country. Anslinger is often referred to as the great racist of the war on drugs, says John Collins, coordinator of the LSE IDEAS International Drug Policy Project in London.

Collins is not certain if Anslinger himself was a bigot. “But he knew that he had to play up people’s fears in order to get federal legislation passed,” Collins said. “So when talking to senators with large immigrant populations, it very much helped to portray drugs as something external, something that is invading the U.S. He would use the term ‘marijuana’ knowing that it sounds Hispanic, it sounds foreign.”

(Image: Poster for Marihuana [The Marijuana Story], 1950)

What Broke The Government?

Francis Fukuyama argues that a primary driver of inefficiency and dysfunction in the American government is the outsize role of courts and legislatures in controlling functions normally performed by executive bureaucracies:

The decay in the quality of American government has to do directly with the American penchant for a state of “courts and parties”, which has returned to center stage in the past fifty years. The courts and legislature have increasingly usurped many of the proper functions of the executive, making the operation of the government as a whole both incoherent and inefficient. The steadily increasing judicialization of functions that in other developed democracies are handled by administrative bureaucracies has led to an explosion of costly litigation, slow decision-making and highly inconsistent enforcement of laws. The courts, instead of being constraints on government, have become alternative instruments for the expansion of government. Ironically, out of a fear of empowering “big government”, the United States has ended up with a government that is very large, but that is actually less accountable because it is largely in the hands of unelected courts.

Meanwhile, interest groups, having lost their pre-Pendleton Act ability to directly corrupt legislatures through bribery and the feeding of clientelistic machines, have found new, perfectly legal means of capturing and controlling legislators. These interest groups distort both taxes and spending, and raise overall deficit levels through their ability to manipulate the budget in their favor. They use the courts sometimes to achieve this and other rentier advantages, but they also undermine the quality of public administration through the multiple and often contradictory mandates they induce Congress to support—and a relatively weak Executive Branch is usually in a poor position to stop them.

All of this has led to a crisis of representation. Ordinary people feel that their supposedly democratic government no longer reflects their interests but instead caters to those of a variety of shadowy elites.Ordinary people feel that their supposedly democratic government no longer reflects their interests but instead caters to those of a variety of shadowy elites.

Drum recommends the essay but quibbles:

There’s not much question that lobbying has exploded over the past half century, nor that the rich and powerful have tremendous sway over public policy. But do powerful interest groups really have substantially more influence in the United States than in other countries? Or do they simply wield their power in different ways and through different avenues? I’d guess the latter. Nonetheless, even if America’s powerful are no more powerful than in any other country, the fact that they wield that power increasingly via Congress and, especially, the judiciary might very well make their influence more baleful.

Andrew Sprung adds his thoughts:

Are other developed democracies better equipped to deal with today’s challenges, such as galloping inequality and slow growth? I imagine that fans of the U.S.’s highly participatory and less-than-majoritarian democracy, like, say, Jonathan Bernstein, would have something to say about that.

In Fukuyama’s telling, the three causes of democratic decay — undue power of interest groups, legislation through the courts, and vetocracy — feed on each other. Interest groups like recourse to the courts; the courts have further empowered interest groups; the courts themselves remain one powerful veto point in our legislative process. In this relatively short piece, however, it remains unclear why we’ve arrived at implied crisis now – why our system has muddled through to adapt to past challenges but now seems stuck. That may be a matter of degree: past reforms have been forced by crisis. But here Fukuyama seems to imply that Constitutional reform — a fundamental change in our structure of government — might be required if the U.S. is to address current challenges effectively.

Will China Spark Another Space Race?

A mugshot of China’s first moon rover, Yutu, was transmitted back to Earth. China’s national flag was displayed. pic.twitter.com/p9gtf3WUWy

— Xinhua News Agency (@XHNews) December 16, 2013

Annalee Newitz applauds the Chinese:

Yutu, similar to rovers like Curiosity on Mars, is the first robotic observer to be deployed on the Moon in roughly three decades — and it’s a first for China, which has now taken the next step on its path into the Space Age. CNSA [the China National Space Administration] will be sharing all the data it gathers with scientists in other nations. This is truly a time to put aside national interests, and celebrate the international achievements of scientists and explorers working together to make new discoveries in space.

David Cyranoski details why scientists “around the world are excited by the possibilities”:

Carle Pieters of Brown University, in Providence, Rhode Island, responded to the news of the location in an email to a lunar community group. “Terrific! That landing site is in some of the unsampled young hi-ti [high titanium] basalts!” she said, referring to the relatively late-forming magmatic rock that scientists hope will hold clues to the Moon’s evolution. The landing success was followed about seven hours later with more celebration when Yutu, the “Jade Rabbit” rover, drove off the lander via a ramp. The six-wheeled, 140-kilogram [309-pound] machine is due to carry out a three-month tour of the Moon’s surface. Its most important challenge, [chief scientist Jun] Yan says, will be to use its deep-probing radar – capable of reaching 100 meters below the surface – to survey the composition of shallow subsurface and lunar crust. The next milestone, Yan says, will be analyzing the composition and distribution of minerals on the surface with it infrared spectrometer and alpha particle X-ray spectrometer.

Becky Ferreira is impressed by the sophistication of the venture:

[T]he Chinese have made no secret of their ambition to achieve leadership in outer space, and Chang’e-3 is a compelling piece of evidence that the country is not messing around. China expects to launch a permanent space station in roughly seven years, followed by a manned moon landing during the 2020s.

Space exploration advocates, damaged as we are by decades of watching lofty goals fail to pan out, are right to be skeptical of such claims. Even so, the sophistication of the Chang’e-3 genuinely speaks to the nation’s dedication to more aggressive space exploration. For example, in addition to being China’s first soft-lander, the Chang’e-3’s is equipped with a lunar-based ultraviolet telescope (LUT) and an extreme ultraviolet imager (EUV). These instruments make it the world’s first moon-based observatory.

And while some commentators disapprove of the Chinese government spending so much on the venture, Alex Berezow sounds a little envious:

It may be tempting for Americans to think, “Been there, done that.” However, China is now envisioning the very same sort of ambitious megaprojects that the US once dreamt of more than 50 years ago, when President John F. Kennedy urged America to “commit itself to achieving the goal … of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.” For instance, China hopes to mine the moon for natural resources and to use it as a staging ground for further space exploration, although some believe the former goal is unrealistic because the cost is likely to exceed the value of the materials.

Still, China’s wild-eyed aspirations are inspiring. It should make us yearn for the days when we, too, thought we could do anything. But those days now seem so long ago.

Meanwhile, Glenn Harlan Reynolds notes that if China wants to make a territorial claim, “there’s not a lot to stop them.” But that doesn’t mean he’s worried:

If the Yutu rover finds something valuable, Chinese mining efforts, and possibly even territorial claims, might very well follow. And that would be a good thing.

What’s so good about it? Well, two things. First, there are American companies looking at doing business on the moon, too, and a Chinese venture would probably boost their prospects. More significantly, a Chinese claim might spur a new space race, which would speed development of the moon. The 1960s space race between the United States and the old Soviet Union saw rapid progress in space technology. We went from being unable to put people in Earth orbit to landing men on the moon and returning them safely to earth, repeatedly, in less than a decade. It happened so fast because each nation was afraid the other would get there first.

Face Of The Day

An activist gestures during a demonstration near the Museu do Indio (Indian Museum) ‘Aldea Maracana’ (Maracana Village) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on December 16, 2013. The demonstrators, among whom there were some 30 Amazonic natives, seized the museum protesting against its scheduled demolition to continue the works in the Mario Filho ‘Maracana’ stadium ahead of the 2014 World Cup. By Tasso Marcelo/AFP/Getty Images.

What Does “Slut-Shaming” Mean Anyway?

Callie Beusman argues that “the term is deployed basically every time someone does or says something not completely celebratory about sex” and is now just “a nebulous blob of a buzzword”:

[I]n accusing someone of slut-shaming a public figure, you dismiss their tone as judgmental and not sex-positive. You characterize them as prudish and a bad or backwards feminist and, as such, you don’t deign to engage with the content of what they’re saying. All this talk of “slut-shaming” causes us to plow blindly through nuance and to get worked up over distracting trifles. When we tell women that it’s ignorant or old-fashioned to feel uncomfortable with over-sexualized depictions of women in the media, we lose sight of the context in which those depictions take place. Because of this, the way we tend to talk about “slut-shaming” can be harmfully reductive.

Saying that feminist discomfort with commoditized sexiness is automatically “shaming” encourages a “you’re either with us or against us” logic. It facilitates sweeping value judgments:

i..e, Lady Gaga’s thong is either good for women or it’s bad for women; Miley Cyrus’ naked music video is either empowering or objectifying. But there’s power in recognizing that a specific performance of sexuality can be at once subversive and pandering: yes, a pop star’s decision to wear a thong and twerk and flaunt her sexuality can be a celebration of the female body and of female sexual agency; yes, it can be an inspiring rejection of the misogynistic notion that women should behave chastely and “appropriately” in the public sphere.

However, such decisions occur in a very specific context. The entertainment industry has a history of commoditizing female sexuality and objectifying women in order to market the idea of sexual availability. When Miley Cyrus, Lady Gaga, Rihanna, Ke$ha, Nicki Minaj, Katy Perry, et. al. make overtly sexual music videos and put on blatantly erotic performances, it’s both a reaction against prohibitive, oppressive attitudes about female sexuality and a canny response to the established fact that (young, heterosexual, female) sex sells. We don’t have to choose between Team Empowerment and Team Oppression in reacting to that.

Mental Health Break

Is Polygamy Headed For The Supreme Court?

In a lawsuit brought by Kody Brown, star of the reality show Sister Wives, a federal judge in Salt Lake City on Friday struck down part of Utah’s 1973 anti-bigamy law, finding that while a man does not have the right to legally marry multiple women, the state cannot prevent cohabitation with multiple “wives” as a religious practice. Lyle Denniston explains the ruling:

Judge Waddoups drew some inspiration for his ruling from the Supreme Court’s 2003 decision in Lawrence v. Texas, declaring a constitutional right of adult same-sex couples to engage in private sexual conduct. But he said he could not rely directly and fully on that ruling, because the Tenth Circuit has given it a narrow reading. Instead, the judge relied mainly upon a 1993 decision, Church of the Lukumi Bablu Aye v. Hialeah, a ruling that barred government interference with the religious rituals of animal sacrifice of the minority faith, Santeria. From that decision, Judge Waddoups found a requirement that the Utah law’s ban on religious cohabitation could not survive a “strict scrutiny” analysis.

While the state law’s ban on cohabitation with another person is formally neutral as written, the judge said it nevertheless is not neutral in its actual operation in banning religious cohabitation. That portion of the 1973 state law discriminates against cohabitation only when it is practiced by those who do so as a matter of religious faith, the judge said. The state of Utah, the judge noted, does not prosecute those who engage in cohabitation as an act of adultery — that is, a married person having intimate relations with a person who is not the spouse. The state thus threatens prosecution only for those who cohabit as a religious activity, according to the judge.

David Copel expects the case to go to higher courts:

It would not be surprising if the case were appealed to the Tenth Circuit, and Judge Waddoup’s opinion seems careful to color within the lines of the Tenth Circuit’s cases interpreting (rather narrowly) the aforesaid modern Supreme Court cases. Should the Browns prevail in the 10th Circuit, the case seems a good candidate for the Supreme Court. The Tenth Circuit has several anti-polygamy decisions within the past few decades, and Judge Waddoups worked hard to distinguish them. Whether the 10th Circuit will consider the distinctions persuasive remains to be seen.

It is important to remember Brown v. Burnham in no way establishes a constitutional right to plural marriage. Nor does the Brown decision challenge ordinary state laws against adultery. Rather, the decision simply strikes down an unique state law which defined cohabitation as “bigamy.” Even then, the statute might have been upheld but for the government’s policy of reserving prosecutions solely for cohabitators who for religious reasons considered themselves to be married to each other under God’s laws, and who fully conceded that they were not married under the civil law of the state.

Mataconis analyzes the ruling’s implications:

Does this mean that the Browns should be permitted to take the next step and established a legal polygamous marriage that would be entitled to the same legal benefits that two-person marriage is throughout the United States? That is, admittedly, a more difficult question. Recognizing a marriage legally ends up creating a whole host of rights and obligations under state and Federal law that may not translate well to multiple person marriage. That, however, is a practical observation rather than a principled one. It’s also a question for another day because it’s not one that the Browns are raising, even if it will be one that conservative critics of the decision will raise as they react to this decision.

Anticipating another argument that many on the right will likely make in response to this decision, it strikes me that this decision is only tangentially related to the issue of same-sex marriage. It’s related in the sense that the 14th Amendment arguments regarding the rights of people to live their private lives and consensual obligations free from state interference are issues in both situations, and also in the sense that the Utah law against “religious cohabitation” clearly treats a certain class of people differently in violation of the Equal Protection Clause.

However, it’s unrelated in the sense that the arguments for same-sex marriage are merely seeking to extend to gay and lesbian couples the same rights and legal privileges already granted to opposite sex couples, whereas this case seeks to attack a provision of Utah law specifically punishing people for their religious beliefs. Indeed, for the most part, there is very little in this opinion that would be applicable outside of Utah and outside of the specific facts of this case. So, when you see the “slippery slope” crowd worrying that the next step along the road is, as Professor Bainbridge puts it, the legalization of adult incestuous marriage or the end of laws against incest themselves, you can largely dismiss it as little more than political rhetoric.

Tobin is also on that slippery slope:

While gay marriage advocates have sought to distance themselves from anything that smacked of approval for polygamy, Waddoups’s ruling merely illustrates what follows from a legal trend in which longstanding definitions are thrown out. The inexorable logic of the end of traditional marriage laws leads us to legalized polygamy. Noting this doesn’t mean that the political and cultural avalanche that has marginalized opposition to gay marriage is wrong. But it should obligate those who have helped orchestrate this sea change and sought to denigrate their opponents as bigots to acknowledge that the end of prohibitions of other non-traditional forms of marriage follows inevitably from their triumph.

Dreher foresees ”the collapse of Christianity as the basis for Western society”:

Waddoups calls a 19th-century Supreme Court ruling banning polygamy “racist” and “orientalist,” because it asserted that Christianity’s teaching on marriage is superior to the polygamous arrangements that some Africans and “Asiatics” (presumably this means Arab Muslims) live by. This is an important point, it seems to me. If Christianity and the Christian moral and societal framework is no longer viewed as normative in laws governing sexual practice, then the slippery slope to legalizing polygamy is here. We already know from the Lawrence ruling that the state may not regulate private consensual sexual conduct; if the principle that privileging Christian marital norms is impermissible is accepted, by what standard do we prevent polygamy? I suppose you could say it harms society in some way, but this judge rejected that argument. Scalia’s Lawrence dissent was correct.

Eugene Kontorovich, on the other hand, praises Waddoups for his “courageous civil rights ruling”:

Most sexual liberties decisions going all the way back to Griswold v. Connecticut come at a time when the relevant practices have won very broad acceptance, especially among the educated elites. Not so with polygamy, which is quite far from the lives of the elites, and is opposed by a Baptists and bootleggers coalition of religious conservatives (bad for the “traditional family,” smacks of Mormonism) and secular liberals (bad for women, smacks of Mormonism). The judge will make few friends with his ruling. Editorialists will not liken it to great civil rights breakthroughs. It will surely be overturned, with conservative judges fearing an expansion of substantive due process, and liberal ones fearing a backlash. And that is what makes it brave, whether right or wrong.

Tropical Diseases In The US

They’re making a comeback:

“It’s so sad,” says Peter Hotez of Baylor College of Medicine, who founded the US’s first dedicated school of tropical medicine in 2011. He estimates that Chagas [disease], worms and other diseases typically associated with the developing world could afflict some 14 million impoverished people in the US. “They are called neglected tropical diseases,” says Hotez. “But in reality, this is about poverty, not climate.”

Worryingly, both situations are getting worse.

In 2008, Hotez made initial calculations of the number of cases in the US for several NTDs, most of which still stand as the best estimates available. Updated work on two parasites, however – Trichomonas vaginalis and Toxoplasma gondii – shows that many more people have the infections than was thought five years ago.

Much is specific to minority communities: 29 per cent of black American women carry T. vaginalis, versus 38 per cent of women in Nigeria. In the US, black women are 10 times as likely as white or Hispanic women to have the parasite, which increases the heterosexual spread of HIV and boosts the risk of a low-birthweight baby. Highly sensitive diagnostic tests were recently developed, and trichomoniasis can be cured with one oral dose of a common drug, metronidazole. But the startling prevalence of the disease suggests neither test nor treatment is routinely used.

Meanwhile, about 8 million people have Chagas disease worldwide, mostly very poor people across Latin America. In the US it mainly affects Hispanic communities. “Kissing bugs” that live in cracks in poor housing pass it to people by defecating while sucking their blood.

(Photo: An Aedes aegypti mosquito – the sort that caused Dengue fever outbreaks in Florida and Texas this summer – bites a human. By Matti Parkkonen.)

The UN vs Drug Reform

The United Nations’ International Narcotics Control Board is upset with Uruguay for legalizing marijuana. Julio Calzada, one of the architects of the new law, holds firm:

We feel that we’re acting within the spirit of the treaties. They provide for different methods, so long as they contribute a solution to the drug problem and aim to improve public health. … Uruguay is a sovereign country, with an elected parliament and a strong democratic tradition, so we’re going to continue with this policy in accordance with our sovereign and democratic rights.

Uruguay’s president is also fighting back:

Mujica dismissed the criticism as a double standard, pointing out that the U.S. states of Colorado and Washington have already legalized weed and that both of the states’ populations individually exceed Uruguay’s 3.4 million inhabitants. “Do they have two discourses, one for Uruguay and another for those who are strong?” Mujica asked.

Under the new law, the government will grow and sell marijuana, but Raul Gallegos wonders about the logistics:

The government has talked about charging $1 per gram of cannabis in order to price traffickers out of the market. Senator Lucia Topolansky, [President Jose] Mujica’s wife, has said the state may provide “cloned seeds,” which allow for a traceable type of plant, to best identify legal pot from the illegal kind. If making quality marijuana available cheaply sounds too good to be true, it probably is. “The costs of production will be higher so the only way to match” illegal pricing “will be a subsidy,” Senator Jorge Larranaga, an opponent of the law, argued in the National Party’s magazine.

The new pot-growing clubs may find costs far too high as well. Uruguay’s law puts a cap on 45 members per club. Laura Blanco, president of Uruguay’s Association of Cannabis Studies, has called this an “expensive proposition when it comes to sharing the cost burden, above all the fixed costs.”

Keating suggests that Uruguay’s legalization will spark a regional trend:

The move has been heavily criticized by neighboring Brazil and Argentina as well as the United Nations. But it’s also being watched closely in a region fed up with years of brutal and seemingly pointless drug violence. Much to Washington’s dismay, Latin American leaders—notably Otto Pérez Molina of Guatemala and Laura Chinchilla of Costa Rica—have been talking openly about the possibility of legalization. Unless Uruguay’s experiment turns into a complete fiasco, other countries are likely to follow its lead soon.

The Computers You Grew Up With

David Banks maps his life through the gadgets that thrilled him as a young nerd in the 1980s and 1990s. On his family’s first computer, the IBM 5150:

[W]hat I remember most about it was how mechanical it was: All the different, almost musical sounds it made when it was reading a floppy or printing something on its included dot-matrix printer. The spring-loaded keys on its impossibly heavy keyboard made the most intriguing sound; when all ten fingers were on that keyboard it sounded like a mechanical horse clacking and clinking. My favorite part of the computer was when you’d turn it off and it would make a beautiful tornado of green phosphorus accompanied by a sad whirling sound. It sounded like this almost-living thing was dying a small death every time you were finished with it. I loved killing that computer.

Why it’s difficult to abandon even the crappiest phones:

I find myself imprinting a small portion of my love for people onto the device that connects me to them. When I switch phones I get a pang of nostalgia. Not for the phone itself, but for the news I got on it. The anxious moments I stared at it waiting for a crush to text me; the bizarre friendship I made with someone who also owned the Motorola PEBL; the phone I used to tell my parents I was engaged. These are intimate moments that are about people, but are mediated through these tiny devices.

(Photo: A child with an IBM 5150 in April 1988. By Engelbert Reineke)

Andrew Sullivan's Blog

- Andrew Sullivan's profile

- 154 followers