Andrew Sullivan's Blog, page 176

August 23, 2014

Running The Numbers On Relationships

Daniel A. Medina presents new findings on how race relates to success at online dating:

The breakthrough came when the researchers found that three multiracial groups were favored more than anyone else, something they referred to as the “bonus effect.” These three groups were Asian-white women, who were viewed more favorably than all other groups by white and Asian men, and Asian-white and Hispanic-white men, who were given “bonus” status by Asian and Hispanic women. … This “bonus effect,” which the researchers said was “truly unheard of in the existing sociological literature,” goes against the long established “one drop rule” amongst American sociologists. Usually applied to people with partial African descent, the rule essentially states that multiracial people even who are even a small part non-white are viewed simply as part of the lower-status (non-white) group.

Of course, even those who’ve parlayed their most desirable qualities (including, apparently, multiracial-ness) into coupledom aren’t guaranteed relationship success. Luckily, Emily Esfahani Smith and Galena Rhoades discuss research (pdf) on how healthy relationships progress:

The freedom to choose any relationship sequence has benefits, but it may also come at a cost long-term. Couples today seem less likely to move through major relationship milestones in a deliberate, thoughtful way. Rather, the new data show that they tend to slide through those milestones. Think of the college couple whose relationship began as a random hookup, the couple who moved in together so that they could pay less rent, or the couple who chose to elope on a whim rather than have a formal wedding. These are couples who, often without realizing it, slid through relationship transitions that could have been planned out, discussed, and debated.

The data show that couples who slid through their relationship transitions ultimately had poorer marital quality than those who made intentional decisions about major milestones. How couples make choices matters.

And how those relationships start also matters. Tom Jacobs flags a study that casts doubt on the longevity of relationships that begin when one partner swoops in and “poaches” the other from an existing relationship:

In three studies, “individuals who were poached by their current romantic partners were less committed, less satisfied, and less invested in their relationships,” reports a research team led by psychologistJoshua Foster of the University of South Alabama.

“They also paid more attention to romantic alternatives, perceived their alternatives to be of higher quality, and engaged in higher rates of infidelity.”

Being poached by your current partner, the researchers conclude, is both fairly common (10 to 30 percent of study participants reported their relationship began that way), and “a reliable predictor of poor relationship functioning.”

Hot And Heavy In The 17th Century

Hal Gladfelder traces the history of outrage over porn:

The brave new world of “sexting” and content-sharing apps may have fueled anxieties about the apparent sexualization of popular

culture, and especially of young people, but these anxieties are anything but new; they may, in fact, be as old as culture itself. At the very least, they go back to a period when new print technologies and rising literacy rates first put sexual representations within reach of a wide popular audience in England and elsewhere in Western Europe: the late 17th and early 18th centuries.

Most readers did not leave diaries, but [English diarist Samuel] Pepys was probably typical in the mixture of shame and excitement he felt when erotic works like L’École des filles began to appear in London bookshops from the 1680s on. Yet as long as such works could only be found in the original French or Italian, British censors took little interest in them, for their readership was limited to a linguistic elite. It was only when translation made such texts available to less privileged readers – women, tradesmen, apprentices, servants – that the agents of the law came to view them as a threat to what the Attorney General, Sir Philip Yorke, in an important 1728 obscenity trial, called the “public order which is morality.”

(Illustration from the Marquis de Sade’s Justine [1791] via Wikimedia Commons)

Drinking Straight From The Box

Megan Kaminski believes it’s well past time for us to take boxed wine seriously:

In America, boxed wine selection has been generally limited to red alcoholic fruit punch and white alcoholic fruit punch. European and Australian winemakers have been putting quality wines in boxes for decades. In some ways, boxed wine is a natural extension of the French tradition of bottles and casks that can be refilled at wineries; they provide efficient and ecologically sound ways of selling and storing wine. They also add to the longstanding tradition of having a house wine—a reliable standby, free from the pomp-filled expectations associated with “discovering” a new bottle. …

Every glass tastes as if it is from a fresh bottle. Gone are concerns about a half bottle of oxidized wine left over from the night before. Boxed wine is also easy to transport on foot. I know from experience that lugging four bottles of wine home from the store is less pleasant than toting a slender box.

She thinks wine culture could use a little more egalitarianism as well:

The fetishized wine bottle might be relegated, rightfully, to the realm of fine wines. And we could be done with pretense—no need to fake proper French pronunciation of some made-up “chateau” from a California mass-producer, no tired discussion of vintage and whether it was a good year for a wine that is clearly not meant to age, no listening to remarks about the charming animals that adorn the label. It’s hard to talk about terroir or feel snooty when you are drinking a wine that in an ounce per ounce comparison costs about as much as a latte.

A Poem For Saturday

I have been luxuriating this August in a college textbook, Tudor Poetry and Prose, edited by five superior scholars (J. William Hebel is first on the list). I’ve been hugely rewarded by the selections as well as the notes and biographies of the poets.

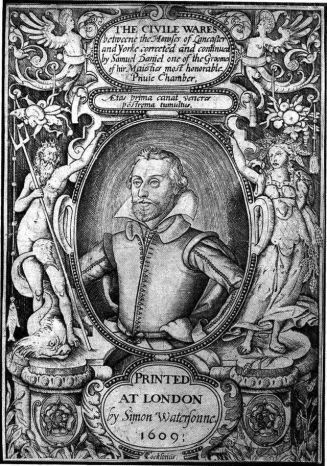

So we’ll add to our summer store of poems on love and courtship (and thwarted and vaunted wooing, as you shall see). We’ll begin with sonnets by Samuel Daniel (1562-1619), who was educated at Magdalen Hall, Oxford and made his early living mostly as tutor to the children of exceptionally well-placed people—among them, the sister of Sir Philip Sidney, Mary Herbert, Countess of Pembroke, whose literary circle Daniel considered his “best school.”

In 1591, twenty eight of his sonnets appeared in the “surreptitious” edition of Sidney’s Astrophil and Stella. (Please investigate this fascinating episode of English literary history.) The next year saw his authorized publication of a volume of sonnets, and in 1604, he was commissioned to write the first masque for the court of the new king, James I, patron of Shakespeare and force behind the third and ever-glorious translation of the Hebrew Bible into English.

In the 19th century, Coleridge described the style which Daniel’s contemporaries praised in similar terms (Sir Thomas Browne referred to him as “well-languaged Daniel”) as “just such as any very pure and manly writer of the present day—Wordsworth, for example—would use,” adding “Thousands of educated men could become more sensible, fitter to be members of Parliament or Ministers, by reading Daniel.”

From the sonnet sequence, To Delia by Samuel Daniel:

Fair is my love, and cruel as she’s fair:

Her brow shades frowns, although her eyes are sunny,

Her smiles are lightning, though her pride despair,

And her disdains are gall, her favors honey.

A modest maid, decked with a blush of honor,

Whose feet do tread green paths of youth and love;

The wonder of all eyes that look upon her,

Sacred on earth, designed a saint above,

Chastity and beauty, which were deadly foes,

Live reconciled friends within her brow;

And had she pity to conjoin with those,

Then who had heard the plaints I utter now?

For had she not been fair and thus unkind,

My muse had slept, and none had known my mind.

(Frontispiece engraving of Daniel for his poem The Civile Ware, 1609, via Wikimedia Commons)

Mental Health Break

The Internet is Neither Open Nor Free

There’s been lots of talk, going around, about the demise of the comments section. This has been spurred in long part by some truly noxious trolling and the seemingly intractable problem of online harassment. Given those realities, I’m amenable to major changes, although I doubt you can really solve this kind of problem. These aren’t platform problems or technology problems. They’re human problems. Humanity exists online, and this is the way humanity is. But if we can avoid even a little of the terrible abuse that people receive online, women especially, it might be time to consider letting comments go, at least in many places. And I say that as someone with an obvious affection for how good comments can occasionally be.

I do think, though, that this is a good opportunity to finally let some of our old myths about the internet die. It’s still common to hear people talk about the internet as this open space where only talent matters and where everyone has a chance to impact the discussion. And it’s time we put those myths to bed.

It’s not like people are totally unaware of all this. Certainly, the way in which major bloggers were largely absorbed into legacy media companies and think tanks is part of the story. One of the things I’ve always liked about Matt Yglesias and Ezra Klein is that they’ve both always been upfront about the fact that their success depends in part on having been in the right place at the right time, and that building a career now is a lot harder than it used to be. Hierarchies harden, alliances form, and given the brutal economic realities of the online writing profession, the game of musical chairs gets more and more brutally competitive. The end result is, inevitably, that people feel more and more pressure to find a niche and to be liked. It’s a word of mouth business. And while the world of commenters may seem far from that of the pros, I think that many of us envisioned a future where commenters could, at their best, provide a kind of counterweight when professional and social pressures influence what the pros think and say. Well, I’m not sure it ever worked that way, but it was nice to dream.

The only people who can really watch the watchers is each other, and like all human beings, they have human concerns which make that job impossible. Is Politico’s clumsy hack job on Vox a clumsy hack job? Yes. Are people defending Vox out of purely principled motives? Um, I doubt it! I’m not impressed by it. But I guess I understand. I mean, you can’t ask people to act as impartial arbiters of their own institutions. In the original telling, naive though it may have been, commenters helped to play that role.

I dunno. Maybe I’ve grown soft in my old age. Or maybe I’m just sensitive to broken labor markets, given that I’m in one myself. (Lord knows, the professional-social dynamics of academia can be as unhealthy and pernicious as you can possibly imagine.) But as I tried to say in the first piece I wrote this week: I don’t know that there’s such a thing as political and intellectual independence when there’s so little economic and labor security. The unemployment rate is down, but I don’t know many people who really feel secure. The terrible condition of the American worker spreads out into everything and hurts people in all industries– even those who would prefer to say, for political reasons, that everything is alright.

I don’t know if there was ever a time when the internet in general, and the world of blogging and online journalism specifically, were these open cultures where anyone truly had a chance to get ahead. And there’s a simple rejoinder to all of this: commenters never were some sort of principled check on bloggers and writers. They brought the rape gifs and the misogyny and the racism and none of the checks and balances. I get that, too. I just think that it’s time for us all to reckon with the fact that the mythology is well and truly dead. The internet is a social system, which means it’s defined by inequalities in power, and those inequalities determine what gets heard and by whom. I will never stop criticizing those writers who decide that they are a very big deal, or stop pointing out the social and professional hierarchies that they care about deeply while pretending they don’t. And as much as criticisms of comment sections are accurate, they are also self-serving, a way for the various Big Deals online to lord it over the proles. But I do hope that I always keep in mind the fact that structural, economic factors are ultimately to blame for our hierarchical, unequal media, not individuals. And that my own pretensions and self-aggrandizement are no kind of alternative.

The whole thing is so… human.

A Perfect Gentleman

Paul Ford sings the praises of politeness:

Here’s a polite person’s trick, one that has never failed me. I will share it with you because I like and respect you, and it is clear to me that you’ll know how to apply it wisely: When you are at a party and are thrust into conversation with someone, see how long you can hold off before talking about what they do for a living. And when that painful lull arrives, be the master of it. I have come to revel in that agonizing first pause, because I know that I can push a conversation through. Just ask the other person what they do, and right after they tell you, say: “Wow. That sounds hard.”

This politeness, according to Ford, can come naturally, even when socially compelled to discuss Jessica Simpson’s jewelry selection:

There is one other aspect of my politeness that I am reluctant to mention. But I will. I am often consumed with a sense of overwhelming love and empathy. I look at the other person and am overwhelmed with joy. For all of my irony I really do want to know about the process of hanging jewelry from celebrities. What does the jewelry feel like in your hand? What do the celebrities feel like in your hand? Which one is more smooth?

Olga Khazan responds, noting the connection between politeness and empathy:

There are multiple ideas of what it means to be polite. The oldest, coined by the British philosopher Lord Shaftesbury in the early 1700s, holds that “‘politeness’ may be defined a dext’rous management of our words and actions, whereby we make other people have better opinion of us and themselves.” That is, we behave politely so as to boost our own social standing among our peers.

But I prefer the definition offered by Brendan Fraser’s Cold-War-era Prepper character in the 1999 feature film Blast from the Past: “Manners are a way of showing other people we care about them.” Signaling that you understand how hard someone else’s situation is certainly makes you better at cocktail parties. But empathy—or “politeness,” or “manners”—isn’t just there at the start of interpersonal relationships; it also holds them together.

August 22, 2014

What Is Christianity For?

That’s the question Rod Dreher asks in a searching reply to my thoughts earlier this week on Christianity and modern life. Some of Rod’s response is a gentle correction to my characterization of the “Benedict Option,” which, in his original essay, he summarizes as “communal withdrawal from the mainstream, for the sake of sheltering one’s faith and family from corrosive modernity and cultivating a more traditional way of life.” To take one example, I described Eagle River, Alaska, as a remote village, while it’s actually in suburban Anchorage – I regret getting that wrong. More importantly, Rod argues that I created something of a straw man, portraying those who pursue the Benedict Option as running for the hills while the world burns. My rhetoric did slip in that direction, and there are nuances to the ways the Benedict Option can be pursued I didn’t capture in my original post. Not all who favor it, and certainly not Rod, argue for “strict separatism” as a response to modern life.

The deeper issue Rod raises, however, goes beyond haggling over this or that detail of the Benedict Option and its various instantiations. Really, arguments about the Benedict Option amount to arguments over the place of, and prospects for, Christianity in the modern world – how Christians should try to live faithfully in our day and age. Here’s the gauntlet Rod throws down:

The way a Christian thinks about sex and sexuality is a very, very good indication of what he thinks about living out the faith in modernity. The reason it is so central is because it reveals, more than any other question now, how a Christian relates to authority and moral order. Matt is a kind and honest interlocutor, and I sincerely appreciate his attention, so please don’t take this in any way snarky or hostile towards him or Christians who share his viewpoint … but the questions have to be put strongly: Where is the evidence for being hopeful about Christianity’s place in modern life? Why should anyone think that the message of Jesus will retain its power in modernity if a Christian experiences little conflict between his faith and the world as it is?

To get to the heart of it: What is Christianity for?

Those obviously are very big questions, but at least a few points can be made to clarify how I approach these matters.

One reason I reacted the way I did to Rod’s essay is because it’s premised on assumptions about modern life I don’t share. It’s not hard to misconstrue those living out the Benedict Option, taking them to perhaps be more separatist than they are, when descriptions of what they are trying to do are prefaced with references to Alistair MacIntyre and suggestions that we are “living through a Fall of Rome-like catastrophe” or worries about “signs of a possible Dark Age ahead.” I’ve never quite bought this line of thinking, never understood modernity as being a rupture or break from a virtuous past. Instead, the formulation I use is that things are getting better and worse at the same time, all the time. The dazzling achievements of modern life are real but also can have a dark underbelly, which means it’s not always possible to clearly separate out what is “good” from what is “bad.” I resist narratives of decline because they seem to miss this, which means the task of discerning the signs of the times, thinking through them as a Christian, is a complex and difficult task. I reject both optimism and despair about modern life.

It’s worth mentioning here that I never argued for full assimilation into modern life, for Christians to be uncritical of what they see around them. I do experience conflict between my faith and the world as it is. But that tends to take the form of deep sadness at the loneliness so many feel in our society, our callous indifference to suffering, and the rampant materialism and worship of power and wealth characteristic of our times, to name just a few examples. And yet this incomplete list betrays the tension I noted above – were there not real problems with more traditional forms of community that, while largely free of the individualism and mobility that contribute to loneliness and neglect, sometimes were repressive and too averse to change or difference? Isn’t our materialism at least partly a function of an economic system that has pressing problems, but also lifted many out of a life of mere subsistence? I don’t mean for these examples to seem trite or too easy, but they get at why, even when I feel conflicted about modern life, it doesn’t take the form of viewing it as a catastrophe or a new Dark Ages.

I admit, too, that I differ with Rod on the question of homosexuality – I hope that even conservative churches come to bless gay relationships. But as the preceding shows, I don’t think that accounts in full for my attitude toward living as a Christian in the modern world. I see it as one more issue that’s of a piece with the complexity of the world around us. The increasing visibility of gay people is a fact that must be dealt with by the Church, and even many traditionalist Christians, like Rod, would be happy to concede that they are glad gay people face better prospects, in society at large, than they would have decades ago. Sexual modernity has made many people, even traditional Christians, more attentive to the ways in which gay people and women, to take the two most prominent examples, suffered in previous eras. Traditional Christians themselves, even when holding the doctrinal line, often understand these matters in ways quite different than they did just a few decades ago, showing more sympathy and humaneness than in the past. I would go so far as to say that Christians have been taught, through the changes brought by modern life, how to be more genuinely loving and decent in these areas than they have been in the past. That is not to dismiss the deep challenges modern life poses, for traditionalists like Rod, to a conservative sexual ethic – I understand, even if I do not fully share, his concerns. I just can’t view the coming of sexual modernity simply as the triumph of hedonism, if for no other reason than that it has led to grappling with real injustices.

The word that I used to describe my approach to these matters is hopeful, and Rod wonders at my use of that term, at least with regard to Christianity’s place in the modern world. I’ve gone on at length – perhaps too long – explaining how I think about modern life because I believe it goes some way toward suggesting an answer. Living hopefully, in light of this, amounts to patiently, humbly sifting through the complexity I described. It means trying to see the truths revealed by modern life as well as working to restrain it’s excesses and problems. And I’m not sure Christians can best do this by withdrawing from the mainstream, rather than critically engaging it.

When we do engage the modern world, joyfully and without rancor or fear, I still believe Jesus’ message of grace and mercy will resonate. To see the good in modern life is not to deny the need for real, costly love in the world, a love that reaches out to the poor and the lonely and the marginalized, a love that looks with compassion on all who suffer and struggle. What is Christianity for? To teach us how to do that, which sounds awfully pious, I know. And that’s certainly not all that can be said about the Christian faith. But when I look around me, I can’t help but see both the remarkable achievements of modern life and, despite those achievements, a world still fraught with injustice and pain. My hope is that we can sustain and extend the former while struggling to embody Christ’s love in the midst of the latter.

(Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus, 1601, via Wikimedia Commons)

Our Government’s Inability To Govern

Frum blames it on reform efforts. He argues that “for 50 years, Americans have reformed their government to allow ever more participation, ever more transparency, ever more reviews and appeals, and ever fewer actual results”:

Journalists often lament the absence of presidential leadership. What they are really observing is the weakening of congressional followership. Members of the liberal Congress elected in 1974 overturned the old committee system in an effort to weaken the power of southern conservatives. Instead—and quite inadvertently—they weakened the power of any president to move any program through any Congress. Committees and subcommittees multiplied to the point where no single chair has the power to guarantee anything. This breakdown of the committee system empowered the rank-and-file member—and provided the lobbying industry with more targets to influence. Committees now open their proceedings to the public. Many are televised. All of this allows lobbyists to keep a close eye on events—and to confirm that the politicians to whom they have contributed deliver value.

In short, in the name of “reform,” Americans over the past half century have weakened political authority. Instead of yielding more accountability, however, these reforms have yielded more lobbying, more expense, more delay, and more indecision.

Face Of The Day

Noriah Daud, the mother of late co-pilot Ahmad Hakimi Hanapi, who perished aboard flight MH17 when it was shot down in eastern Ukraine, attends a burial ceremony in Putrajaya, outside Kuala Lumpur on August 22, 2014. Black-clad Malaysians paused for a minute of silence August 22 on a nationwide day of mourning held to welcome home the first remains of its 43 citizens killed in the MH17 disaster. By Mohd Rasfan/AFP/Getty Images.

Our coverage of the ongoing conflict in Ukraine is here.

Andrew Sullivan's Blog

- Andrew Sullivan's profile

- 153 followers