Andrew Sullivan's Blog, page 174

August 25, 2014

Ally With Assad?

Assad and ISIS as drawn by Iranian artist Mana Neyestani who exposes Assad's brutal manipulation of terror. http://t.co/oy2XHYny1k—

Larry Deyab (@larrydeyab) August 25, 2014

Hassan Hassan argues that we shouldn’t, because he hasn’t really been fighting ISIS in the first place:

One might argue that Assad’s strategy was a cynical game and that once he is assured of his survival, he would be well-positioned to fight the group. But even that argument ignores basic dynamics: If Assad genuinely wants to fight ISIS today, he is as capable of doing that as Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki was when ISIS took over three Iraq provinces. ISIS controls large swathes in rebel-held Syria, areas that have been outside the regime’s control for one to three years. How could the Assad regime fight against ISIS in Raqqa or Deir Ezzor, for example? Would the local population fight side by side with the regime? That is extremely unlikely, given that people have condemned reports that the United States intends to strike against ISIS in Syria while ignoring the regime’s atrocities for more than three years.

A more prudent approach is to look at the rise of ISIS as a long-term menace that can only be addressed through a ground-up pushback. The opposition forces are not only possible partners, they’re essential in the fight against ISIS. After all, they’re the ones who have been fighting ISIS since last summer, and drove it out of Idlib, Deir Ezzor and most of Aleppo and around Damascus. It cost them dearly: more than 7,000 people were killed. Fighting ISIS should be part of a broader political and military process that includes both the regime and the opposition, but not Assad.

Max Abrahms sees the situation differently:

Our national security ultimately depends on crushing ISIS not only in Iraq, but also in Syria. In the past, Assad’s forces were reluctant to engage ISIS directly. But the gloves have come off in the last couple of weeks. If Assad perceives ISIS as an existential threat, he will tolerate — even secretly welcome — U.S. military assistance. This is an opportunity Washington should seize not for him, but for us.

But James Antle seeks out the genuinely “realist” position:

Contrary to the BuzzFeed headline, few foreign-policy experts want a full operational alliance with Syria or Iran. Some have called for what Crocker, Luers, and Pickering have described as “mutually informed parallel action” against ISIS. Others have merely suggested the U.S. not destabilize ISIS’s enemies in the region, while the al-Qaeda offshoot is beheading American journalists and terrorizing religious minorities in Iraq. Even without any practical cooperation, it is hard to see how Syria and Iran wouldn’t to some extent be beneficiaries of any successful military action against ISIS. But for all the tyranny and terror ties of those regimes, ISIS is most directly the progeny of those who toppled with twin towers and attacked the United States on 9/11. After more than a decade at war in Afghanistan in response to the Taliban providing a safe haven for Osama bin Laden, wouldn’t an ISIS state in parts of Iraq and Syria be a worse outcome?

Keating believes Assad has played his cards perfectly and gotten just what he wanted:

There’s been speculation for some time that the Syrian leader would seek to use the crisis in Iraq to his advantage. It’s pretty apparent that Syrian forces tolerated the rise of the group in a bid to divide the rebels and scare off wary Western supporters, and only began attacking it after the Iraq crisis began this summer. It was a high-stakes gamble given that ISIS now reportedly controls about a third of Syrian territory, but one that could finally be paying off for the internationally isolated Syrian leader. …

Even if the U.S. doesn’t coordinate with Assad’s government—the White House position as expressed by Deputy National Security Adviser Ben Rhodes is still that he’s “part of the problem”—the shift in priority to ISIS does make it more likely that the American government is going to accept Assad remaining in power. Or at least it makes it less likely that the U.S. will take any major steps to remove him. Assad played the long game with a pretty weak hand and now appears to be winning.

Although they don’t necessarily make the case for an alliance, Ishaan Tharoor observes that the events of the past three years have sort of proven Vladimir Putin right about the folly of pushing regime change in Syria:

In his New York Times op-ed, Putin reminded readers that from “the outset, Russia has advocated peaceful dialogue enabling Syrians to develop a compromise plan for their own future.” That “plan for the future,” the Russians insisted, had to involve negotiation and talks between the government and the opposition, something which the opposition rejected totally at the time. In November 2011, Putin’s foreign minister Sergei Lavrov criticized other foreign powers, including the United States, for not helping pressure opposition forces to come to the table with the Assad regime. “We feel the responsibility to make everything possible to initiate an internal dialogue in Syria,” Lavrov said at a meeting of APEC foreign ministers in Hawaii.

The Arab Spring was in full bloom and U.S. officials thought regime change in Syria was an “inevitable” fait accompli. That calculus appears to have been woefully wrong. Now, the conflict is too entrenched, too polarized, too steeped in the suffering and trauma of millions of Syrians, for peaceful reconciliation to be an option.

A Hobby Lobby Patch For Obamacare

On Friday, the Obama administration proposed a fix to the ACA’s contraceptive mandate that it hopes will render the effects of the Hobby Lobby ruling moot by providing a way for employees of closely-held corporations with religious objections to the mandate to obtain contraception coverage. Sarah Kliff outlines the new rule, on which the administration is now seeking comment:

The Obama administration wants to extend the accommodation for religious non-profits — where the health insurance plan, rather than the employer, foots the bill for birth control — to objecting for-profit organizations. At a company like Hobby Lobby, for example, this would mean that the owners would notify the government of their objection to contraceptives. The Obama administration would then pass that information along to Hobby Lobby’s health insurance plan, which would be responsible for paying for the birth control coverage. …

The White House will also give more leeway to religious non-profits, like hospitals and colleges, that do not want to comply with the contraceptive mandate. These non-profits will no longer be required to notify their health plan that they will not provide contraceptives, as preliminary regulations would have required. Instead, these employers will now only be required to notify the federal government of their objection and the government will have the responsibility of notifying the insurance plan.

But religious organizations that object to the mandate in and of itself are not satisfied:

“Here we go again,” said Russell Moore, president of the policy arm of the Southern Baptist Convention, the largest U.S. Protestant denomination. “What we see here is another revised attempt to settle issues of religious conscience with accounting maneuvers. This new policy doesn’t get at the primary problem.”

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops said it’s worried that the administration’s proposal could limit which for-profit businesses can receive a religious exemption. “By proposing to extend the ‘accommodation’ to the closely held for-profit employers that were wholly exempted by the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Hobby Lobby, the proposed regulations would effectively reduce, rather than expand, the scope of religious freedom,” the group’s statement read.

Charles Pierce expected as much:

After all, the opposition to birth control is not based on the opposition to a government mandate. It’s based on the opposition to the medicine, and the purpose that medicine serves. The question being litigated — in public and, sadly, in the courts — is not constitutional. It’s theological. The essential text is not the Constitution. It’s Humanae Vitae.

Scrutinizing how this rule change will adjust the terms of the debate over the mandate, Marty Lederman argues that the religious objectors have few legal legs left to stand on:

The regulation does not require the organizations to contract with an issuer or a TPA–and if they do not do so, then the government currently has no way of ensuring contraceptive coverage for their employees. But even if that were not the case–i.e., even if federal law coerced the organizations to contract with such an issuer or TPA–Thomas Aquinas College and the other plaintiffs haven’t offered any explanation for why, according to their religion, the College’s responsibility for this particular match between TPA and employees would render the College itself morally responsible for the employees’ eventual use of contraceptives, when (i) such employees would have the same coverage if Aquinas had contracted with a different TPA; (ii) such employees would continue to have coverage if they left the College; and (iii) the College itself does not provide, subsidize, endorse, distribute, or otherwise facilitate the provision of, its employees’ contraceptive services.

Be that as it may, it appears that this will now be the primary (if not the only) argument the courts will have to contend with in light of the government’s newly augmented accommodation.

And Jonathan Cohn wonders what the Supreme Court will make of it:

With Hobby Lobby, the justices implied strongly that the old workaround—the one the Administration was already providing churches and the like—was acceptable. With Wheaton, the Court said that, no, asking employers to write a letter to insurers infringed upon their religious freeom. That’s what made Justice Sonya Sotomayor and two of her colleagues angry enough to write a blistering dissent: The second directive seemed to undermine the spirit of the first. With this new regulation, the Administration is basically calling the Court’s bluff, as Ian Millhiser puts it at ThinkProgress—to force the Court, once and for all, to decide whether any workaround passes muster or if the contraception requirement itself is simply unacceptable.

Ebola Is Mostly Killing Women

Lauren Wolfe wants more attention paid to that fact:

Data show that many infectious diseases affect one gender more than another. Sometimes it’s men, as with dengue fever. Sometimes it’s women generally, as with E. coli, HIV/AIDS (more than half the people living with the virus are female), and Ebola in some previous outbreaks. Sometimes it’s pregnant women and mothers, as with H1N1 (an outbreak in Australia is currently infecting women over men by a 25 percent margin).

Yet when women are the primary victims of an epidemic, few are willing to recognize that this is the case, ask why, and build responses accordingly. Indeed, experts say that too little is being done to put even the small amount that is known about gender differences and infectious diseases into practice — to determine in advance of outbreaks, for instance, how understanding gender roles might help in the development of a containment or prevention strategy. Not only that, but there is too little research being done to understand how infectious diseases affect the sexes differently on a biological level. It’s like Groundhog Day each time a disease surges, and people are losing their lives because of it. “We can’t get past the ‘interesting observation’ stage,” says Johns Hopkins University professor Sabra Klein. Public health officials generally gather data on age and sex in a crisis, but “nobody goes somewhere with it.”

(Photo: A West Point slum resident looks from behind closed gates on the second day of the government’s Ebola quarantine in her neighborhood on August 21, 2014 in Monrovia, Liberia. By John Moore/Getty Images)

Summer’s End

Yikes, I’ve been looking forward to doing this ever since Andrew asked in mid-summer, but now I feel like Sue and I have been given the keys to a shiny car that we’re a little unsure how to drive. I note with some relief that the week before Labor Day is the temporal equivalent of the empty mall parking lot, and that the regular Dish staff, in addition to doing most of the posting, also oversees what we write, a bit like the driving instructor with the extra set of brakes on his side of the floorboard. But I’m thrilled to be here, because like Sue I’ve been following Andrew around the web for years, and find myself strangely moved be part of the inquiring and eloquent community of readers that has developed here.

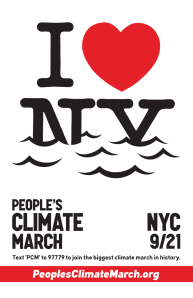

I’m best known as an environmental writer and activist. My preoccupation is global warming, about which I wrote what is commonly regarded as one of the first books for non-scientists. The End of Nature came out a quarter-century ago next month—and I will cap that 25 years of involvement by helping organize what will (we hope) be the largest climate demonstration in human history on Sept. 21st in New York. (You sign up here and yes I will mention it again). Thinking about climate has molded my outlook enormously. I’ve come to think that the culture, including the blogosphere, pays far too little attention to the ongoing collapse of our physical systems: yes, the planet is burning in Diyala province, in the streets of Aleppo, in the country around Donetsk, in the fearful alleys of Gaza City, and in a dozen other places. But the planet is also burning—last month the demographers told us that a majority of the planet’s population has never known a month where the globe was cooler than the 20th century average. Climate change is no longer a future threat—it’s the single most distinctive fact about our time on earth, so it tends to preoccupy me.

of the first books for non-scientists. The End of Nature came out a quarter-century ago next month—and I will cap that 25 years of involvement by helping organize what will (we hope) be the largest climate demonstration in human history on Sept. 21st in New York. (You sign up here and yes I will mention it again). Thinking about climate has molded my outlook enormously. I’ve come to think that the culture, including the blogosphere, pays far too little attention to the ongoing collapse of our physical systems: yes, the planet is burning in Diyala province, in the streets of Aleppo, in the country around Donetsk, in the fearful alleys of Gaza City, and in a dozen other places. But the planet is also burning—last month the demographers told us that a majority of the planet’s population has never known a month where the globe was cooler than the 20th century average. Climate change is no longer a future threat—it’s the single most distinctive fact about our time on earth, so it tends to preoccupy me.

That said, I’m conscious we’re at summer’s end—I feel the need to wring the last easy joys out of the season before the world really begins again a week from tomorrow. So with any luck I’ll manage a post or two of the slightly less-dire variety. It’s useful to me to remember that when it gets hot out one should build a giant protest movement (in my case I’ve volunteered at 350.org since I helped found it six years ago) but one might also consider going for a swim.

Framing A Hidden Paris

Jonathan Curiel explores photographer Michael Wolf‘s new series capturing the city’s rooftops:

Wolf, whose previous photo series have been mostly centered in China and Japan, wandered along Paris’ rooftops to find an architectural side of Paris that is cracking and atrophying out of public view. Wolf — as he did with his acclaimed “Architecture of Density” series from Hong Kong — squeezes the skyline out of each scene, condensing what could be sprawling vistas into tight layers of metal and cement. Dotting Wolf’s roofs are scores of orange, red, and blueish vents that look like patterns of pottery or even engorged Lego pieces. The title of Wolf’s exhibit, “Paris Abstract,” advertises his photos’ location but also his aim: to disconnect Paris from its idealized reputation — to, in a sense, “de-Paris” Paris.

“When I went up on rooftops, I realized that it’s a perspective that most people don’t see,” says Wolf during a visit to Robert Koch Gallery in downtown San Francisco, where his exhibit is on display through [Sept 6]. “If you see Paris from the foot perspective, it’s all polished and perfect, and there’s nothing improvised or broken or damaged. The rooftops are totally different. The people who work up there say, ‘Oh, no one’s going to see this anyway,’ and they dump something, or the chimney is broken. In that sense, it was a Paris that I found very sympathetic.”

A few more images from the series after the jump:

The Dish previously featured Wolf’s urban-Asia photographs here. His other Paris series, utilizing Google Street View, is here. You can also follow him on Facebook.

And So We Begin

Greetings, People of the Dish. My name is Sue Halpern and I have been one of you for at least a decade, having followed this blog from independence to Time to the Atlantic to the Daily Beast and back to independence. When The New York Review of Books, my spiritual and intellectual home, was in the beginning stages of designing its own blog, I suggested to my friends there that that they take a page or two out of Andrew’s playbook because The Dish, it seemed to me then, as it does to me now, manages to combine the serious and the playful, skips the mean part (no comments, thank you very much), all the while trading on serendipity and engagement. That’s what drew me in as a reader, even though my own unrepentant liberal politics stood at a sharp angle from Andrew’s studied conservatism. But over time there has been an unlikely convergence and the angle has largely collapsed. Not completely, but more often than not.

Pransky At Work

Over those same years, though, I’ve found that my “belief” in politics, has diminished. If, before, I thought that electoral politics mattered—and I did; I was the one going door-to-door in swing states—now I have a hard time holding on to that belief. If I thought that government, our government, because it is of and by and for the people—that is, because it is us—existed to make our lives together more tenable, well, let’s just say that with my tax dollars going to support Gitmo, the militarization of the police, subsidies to oil companies, and on and on, I’ve become much more cynical. Wouldn’t it be nice if, when we paid our taxes we could tell the government where we wanted our money to go—to the National Parks, say, and not to those oil companies—but of course that’s not the nature of democracy. If faith is the belief in things unseen, then I guess I will continue to have faith in “we the people,” but it is, and will be, a faith sorely tried by doubt.

Did I say that I have a doctorate in political theory from Oxford? Or that I’m married to a man who has been manically trying to bring together people from all over the world into a concerted movement to redirect the trajectory of climate change? Or that I live in Vermont, where neighborliness is a good part of our politics? Scale, it turns out, matters. Scale things up and no one knows anyone, and decisions are made using algorithms and rubrics. Am I suspicious of big government? I guess by now I am. Are most Americans with me? Not as much as you might imagine. A few weeks ago I wrote a piece for the New York Review of Books about Edward Snowden, Glenn Greenwald, and the NSA, in which I noted that when George W. Bush was in office, the majority of Democrats were opposed to indiscriminate government surveillance and the majority of Republicans were fine with it, while that under Obama, those responses flipped, and Democrats were cool with government spying. To my mind, we maintain a naïve understanding of the power of bureaucracy to direct government when we think it’s okay for one party to do something that we revile if the other party were to do the same.

I’ve been writing about privacy issues, and technology, for a long time, and not always in tandem. I appreciate technology—I am a sucker for the latest Indiegogo gadgetry and know more about the iPhone 6 than I care to admit—but I also appreciate the vigilance it should, but rarely does, inspire in us. Meanwhile privacy, which I have taken as a social good, and as a right, and as a part of my DNA and yours, no longer seems a given. Instinctively I think that’s bad, but I’m willing to consider the opposite.

So let’s talk about dogs. My most recent book, “A Dog Walks Into A Nursing Home,” is about the work my canine partner, Pransky, and I do, as a therapy team at our local public nursing home. (I did an “Ask Anything” about it when the book came out last year.) I am thrilled to be writing for a publication that has a baying beagle as its mascot, so be prepared, over the next seven days, to help me ponder the essential bond we have with our dogs.

I am thrilled, too, to be sharing this virtual space with the man with whom I share real, physical, tangible space. After decades of what the child psychologists call “parallel play,” career-wise, we have spent the past year collaborating on a series of pieces for Smithsonian that combine our passion for ethnic food with our interest in the immigration, and have found that we really like working together. So thank you Andrew and crew for this opportunity to double-team the Dish. And here we go.

Unfair Trade

Oscar Abello suggests fair-trade coffee might actually be bad for workers:

Fair-Trade certified coffee has become known as an easy way for coffee drinkers to make the world a better place for coffee growers, many of whom are among the world’s poorest people. But a study released in April 2014 seriously questions how much fair-trade certification really does for them. Limited to 12 research sites in Ethiopia and Uganda, the study found that non-fair-trade certified farms paid better wages and provided better working conditions than fair-trade certified farms. The study authors surveyed 1,700 farm workers, going beyond the usual farm owner or farming co-op member that has historically been the beneficiary at the heart of fair trade’s story. …

So why are farm workers finding a better deal on non-fair-trade certified farms? Scale could be one reason. Until recently, only small farms, loosely defined as 10 acres or less, have been eligible for fair-trade certification. The report says larger farms appeared to be in better financial position to offer higher pay, more annual days of work, and better working conditions. Regulatory requirements like paid maternity leave for agricultural workers may also apply only to larger farms, the study found.

(Photo by Eric Magnuson)

The Cost Of Pop-Ups

Ethan Zuckerman, who helped invent the pop-up ad, expresses regret about where ads have taken the Internet:

I have come to believe that advertising is the original sin of the web. The fallen state of our Internet is a direct, if unintentional, consequence of choosing advertising as the default model to support online content and services. Through successive rounds of innovation and investor storytime, we’ve trained Internet users to expect that everything they say and do online will be aggregated into profiles (which they cannot review, challenge, or change) that shape both what ads and what content they see. Outrage over experimental manipulation of these profiles by social networks and dating companies has led to heated debates amongst the technologically savvy, but hasn’t shrunk the user bases of these services, as users now accept that this sort of manipulation is an integral part of the online experience.

Users have been so well trained to expect surveillance that even when widespread, clandestine government surveillance was revealed by a whistleblower, there has been little organized, public demand for reform and change.

Zuckerman encourages sites to “charge for services and protect users’ privacy.” Meanwhile, DJ Pangburn is skeptical users would cough up the cash for an internet without ads:

Paying for an ad-free internet would be cheaper than cable, but nearly zero people do so.

By dividing digital advertising spending in the UK in 2013 (£6.4 billion) by the total number of UK internet users (45 million), Ebuzzing found that an ad-free internet would cost around £140 ($232.24) a year. The survey also found that 98 percent of UK consumers would be unwilling to pay that amount of money for an ad-free internet.

August 24, 2014

A Poem For Sunday

Another from Samuel Daniel’s sonnets, To Delia:

Why should I sing in verse, why should I frame

These sad neglected notes for her dear sake?

Why should I offer up unto her name

The sweetest sacrifice my youth can make?

Why should I strive to make her live forever,

That never deigns to give me joy to live?

Why should m’afflicted muse so much endeavor

Such honor unto cruelty to give?

If her defects have purchased her this fame,

What should her virtues do, her smiles, her love?

If this her worst, how should her best inflame?

What passions would her milder favors move?

Favors, I think, would sense quite overcome,

And that makes happy lovers ever dumb.

(Photo by Pavlina Jane)

A Novel Idea For A Book

Dan Piepenbring calls Cory Arcangel’s Working on My Novel “a brilliant litmus test—there are those who will read it as a paean to the fortitude of the creative spirit, and those who will read it as a confirmation of the novel’s increasing impotence”:

Arcangel suggests there’s something inherently ennobling in trying to write, but his book is an aggregate of delusion, narcissism, procrastination, boredom, self-congratulation, confusion—every stumbling block, in other words, between here and art. Working captures the worrisome extent to which creative writing has been synonymized with therapy; nearly everyone quoted in it pursues novel writing as a kind of exercise regimen. (“I love my mind,” writes one aspirant novelist, as if he’s just done fifty reps with it and is admiring it all engorged with blood.)

It’s also a comment on the peculiar primacy the novel continues to enjoy—not as an artistic mode but as a kind of elevated diary, a form of what we insidiously refer to as “self-expression,” as if anyone’s self is static enough to survive transmission to the page. Not for nothing do we have Working on My Novel instead of Working on My Screenplay or Working on My Scrimshaw, because the novel, with its rich intellectual-emotional tradition and its (very occasional) commercial viability, is still perceived as the ideal vehicle for saying something ambitious. Even as fewer people read novels, we’re made to feel that writing one is a worthy, rigorous enterprise for serious thinking people, a means of proving that we have reservoirs of mindfulness and discipline deeper than our peers’. And so we try to write fiction, though certainly we don’t need to, and, as this book attests, we often don’t especially want to, even if we greet the task steeled by a perfect cup of coffee, a glass of red wine and a hot bath, or an Eminem song.

Andrew Sullivan's Blog

- Andrew Sullivan's profile

- 153 followers