John G. Messerly's Blog, page 147

April 14, 2014

Book Dedications

For the first time since beginning to blog, I did not write an entry on consecutive days. The weather was beautiful here in the northwest and the mountains were calling. I appreciate the hundreds of readers who visited the site during the lull in my productivity.

Today I was thinking about book dedications. I have always tried to write meaningful ones and have always enjoyed reading the dedications of others. he first one I wrote was for my master’s thesis in graduate school.

“To my father, who approved of my being inquisitive.”

This was a remembrance of a dinner table conversation when I was young. My father told me I was inquisitive and I asked what the word meant. After he told me I asked if it was good to be inquisitive. He said yes. My next one was for my doctoral dissertation.

To my mother and father

whose love nurtured me,

And to Jane,

whose love sustains me …

I suppose that represented the transition from focusing on parental love to the love of my spouse. The next was for a college ethics textbook:

For Jane

“a lily among the thistles …” (Song of Solomon 2:2)

Anyone who knows me will find it ironic that I quote the Bible. But I had recently run across the quote and was trying to capture the sense in which Jane is incorruptible, unlike so many in this world. I dedicated my next book to my graduate school mentor Richard J. Blackwell, whom I discussed in my very last post. He was the inspiration for that piece of research so it seemed appropriate. Talking with him years later he told me that I was the only one to have ever dedicated a book to him, and he seemed pleased with my decision.

To Richard J. Blackwell

an exemplar of moral and intellectual virtue.

My most recent work on the meaning of life bore this inscription:

For my children—John Benjamin, Katie Jane, Anne Marie, and Joshua Harrison—that you may live forever in a good, beautiful, and meaningful world;

And for Jane … that together we may somehow join them.

Perhaps this represents the gradual transition from parents to spouse to children, as well as my hope that somehow the future will be better.

Finally here are my two favorite dedications, both from two of my intellectual heroes. The first is Will Durant’s dedication to his wife Ariel in his 1926 book, The Story of Philosophy, still one of the best-selling philosophy books in the history of American publishing. At the time Durant was in his early forties and his wife was in her late twenties. Clearly it was written with the expectation that she would outlive him. As it turned out they died a few days apart after almost seventy years of marriage. It is most so beautiful.

Grow strong, my comrade … that you may stand

Unshaken when I fall; that I may know

The shattered fragments of my song will come

At last to finer melody in you;

That I may tell my heart that you begin

Where passing I leave off, and fathom more.

― Will Durant, The Story of Philosophy

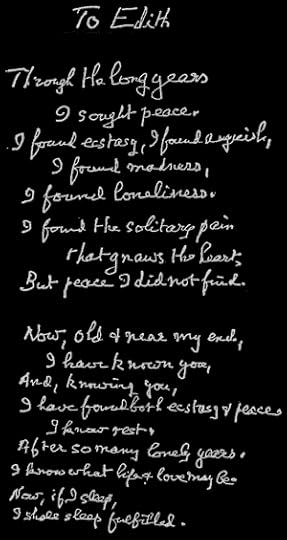

Finally there is this hand-written dedication by Bertrand Russell to his last wife Edith. It was written when Russell was almost 80 years old, after many attempts at finding love. It is wistful reminder that love and peace can be found.

.

(And for those who don’t read cursive anymore here is the text.)

To Edith

Through the long years

I sought peace,

I found ecstasy, I found anguish,

I found madness,

I found loneliness,

I found the solitary pain

that gnaws the heart,

But peace I did not find.

Now, old & near my end,

I have known you,

And, knowing you,

I have found both ecstasy & peace,

I know rest,

After so many lonely years.

I know what life & love may be.

Now, if I sleep,

I shall sleep fulfilled.

April 11, 2014

Optimism

Should we be optimistic? Is optimism rationally justified? Is it practically justified? I contend that optimism is preferable to pessimism, even though it is no more justified by the facts of reality than pessimism. For optimism is not a description of the world at all, it is an attitudinal response to it, and one conducive to both our happiness and to human flourishing. In short, optimism is reasonable because it leads to happiness.

Now consider beliefs. Beliefs play the role of representing reality. If we find that beliefs don’t adequately do this, then we ought to reject them; if beliefs do adequately represent reality, then we ought to keep them. Now what counts as making a belief rational? Here we distinguish between strongly rational beliefs—for which the evidence is nearly irrefutable—and weakly rational beliefs—which we believe as a practical necessity in order to act in the world.

But beliefs are just one attitude we can take toward reality. We can also adopt an optimistic attitude which does not assume any cluster of beliefs, and which cannot be undermined for being irrational like a belief can. Of course optimists may lose their optimism when bad fortune strikes, but we are all happier when we are optimistic and less so when we are pessimistic—and this is the rational ground for optimism.

Yet optimism is not wishful thinking. Wishful thinking involves false beliefs, whereas optimism doesn’t necessarily involve any beliefs. Optimism also has positive results. Consider David Hume’s attitude toward his impending death. Diagnosed with a fatal disease, Hume begins his ruminations thus: “I was ever more disposed to see the favorable than unfavorable side of things: a turn of mind which it is more happy to possess, than to be born to an estate of ten thousand a year… It is difficult to be more detached from life than I am at the present.”1 While many fear death or react in ways that disturb tranquility, Hume’s sanguine resignation shines forth as a beacon of reasonableness. Optimism is a reasonable and beneficial response to the human condition.

A similar sentiment was shared with me about twenty years ago in a hand-written letter (remember those?) from my friend and graduate school mentor, Richard J. Blackwell. This man of equanimity gave me the most salutary advice Replying to my queries about the meaning of life he wrote:

As to your “what does it all mean” questions, you do not really think that I have strong clear replies when no one else since Plato has had much success! It may be more fruitful to ask about what degree of confidence one can expect from attempted answers, since too high expectations are bound to be dashed. It’s a case of Aristotle’s advice not to look for more confidence than the subject matter permits. At any rate, if I am right about there being a strong volitional factor here, why not favor an optimistic over a pessimistic attitude, which is something one can control to some degree? This is not an answer, but a way to live.

Today Professor Blackwell is old and infirmed, but I will never forget the contribution he made to my education. And I still have that letter.

1. “My Own Life,” Preface to David Hume’s The History of England (New York: John B. Alden Publisher, 1885) vii, xi-xii.

April 10, 2014

Predicting Our Own Happiness

In the last few decades there has been a lot of research on human happiness. Surprisingly, Daniel Gilbert found that we are bad at predicting our own happiness, thus we don’t so much steer our way to happiness as stumble into it. (See links to books below.) Gilbert’s researches something called “affective forecasting,” the forecasting of future emotional states. Needless to say this is important since our decisions, preferences, behaviors, and the quality of our lives depend on our assessment of future states.

Why are we so bad at predicting future happiness? Researchers have found that cognitive biases–impact bias, focalism, immune neglect, projection bias, misconstruels, cause forecasting errors, time discounting, expectation effects, memory, and emotional evanescence–are the cause. I accept the research, but what should we do with this knowledge?

Obviously, if the goal is to be happy, we should minimize the cognitive biases that mislead us. To do this we might develop our critical thinking skills, reflect more deeply about our choices, study the feelings of, and consult with, others, and try to better understand our own psychology. But there is no foolproof way to proceed. We would do best to cultivate wisdom, that slow accumulation of experiences as to how best to live. For instance, experience has taught me that I need to exercise to be emotionally stable, write to express myself, drink and eat less to think more clearly, and converse with others to escape the prison of loneliness. As Socrates advised long ago, we should strive to “know thyself.”

But there are no shortcuts.

If the way I have shown to lead to these things now seems very difficult, still, it can be found. Indeed, what is so rarely discovered must be hard. For if salvation were ready at hand, and could be found without great effort, how could nearly everyone neglect it? But all things noble are as difficult as they are rare. ~ Baruch Spinoza

The How of Happiness: A New Approach to Getting the Life You Want

Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being

Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience

April 9, 2014

Robots and the Economy

My post of March 31, 2014, “Do We Need A New Economic System?” briefly mentioned the computer scientist Marshall Brain’s thoughts on robotics and the future of the economy. Brain penned these prescient thoughts more than ten years ago in three essays and a FAQ section on his website. Because of their importance and insight, I wanted to summarize them for my readers, staying as close to the original texts with little commentary.1 (As you read, remember all these predictions were made more than ten years ago.)

Robotic Nation

Overall Summary

The Tip of the Iceberg – We now see technology’s impact on employment because of

Moore’s Law – Exponential growth is leading to a

The New Employment Landscape – where the equation

Labor = Money – will no longer hold, necessitating new economic models.

The tip of the Iceberg – Brain believes every fast food meal will be (almost) fully automated within a few years, and this is just the tip of the iceberg. Right now we interact with automated systems: ATM machines, gas pumps, self-serve checkout, etc. These systems lower cost and prices, but “these systems will also eliminate jobs in massive numbers.” There will be massive unemployment in the next decades as we enter the robotic revolution.

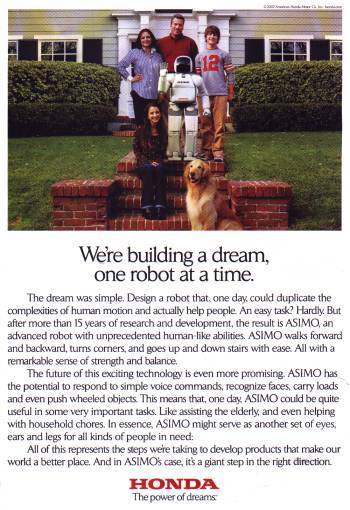

A feasible scenario suggests that in the next fifteen years most retail transactions will be automated and 5 million retail jobs lost. Next, walking, human shaped robots will begin to appear–Honda’s Asimo is an early example. By 2025 we may have machines that hear, move, see, and manipulate objects with roughly the ability of humans. These machines will be equipped with AI systems, making them seem humanlike. Robots will get cheaper and become more human shaped to easily facilitate their use of cars, elevators, and other objects in the human environment. By 2030 you will buy a $10,000 robot that will clean, vacuum, mop, sweep, mow grass, etc. These robots would last for years, need no vacation or sick time, and eliminate human jobs. Robotic fast food places will open shortly thereafter and by 2040 will be completely robotic. By 2055 robots will replace half the American workforce leaving millions unemployed. Restaurants, construction, airports, hospitals, malls, amusement parks, truck drivers and airplane pilots are just some of the jobs and locations that will have mostly robotic workers.

While robotic vision or image processing is currently a stumbling block, Brain thinks we will make significant progress in this field in the next twenty years. This single improvement will yield catastrophic changes, just as the Wright brothers breakthrough brought about aviation. Brain applauds these developments. After all, who wants to clean toilets, flip burgers, and drive trucks? “These activities represent a massive waste of human potential.”

If all this sounds crazy, Brain asks you to consider a prediction of faster than sound aircraft in 1900; a time when there were no radios, model T’s or airplanes. Then many thought heavier than air flight was impossible, and one who predicted it was often ridiculed. Such considerations lead to the conclusion that the employment world will change dramatically over the next fifty years. Why? The fundamental answer is Moore’s Law, that CPU power doubles every 18 to 24 months. Computers in 2020 will have the power of the NEC Earth Simulator. By 2100 we may have the power of a million human brains on our desktop. Robots will take your job by 2050 with the marriage of: a cheap computer with the power of a human brain; a robotic chassis like Asimo; a fuel cell; and advanced software.

While the employment landscape is not so different from the one of 100 years ago, it will be vastly different once robots that see, hear, and understand language compete with humans for jobs. The 50 million jobs in fast food, delivery, retail, hotels, restaurants, airports, factories, construction will be lost in the next fifty years. But America can’t deal with 50 million unemployed. And the economy will not create 50 million new jobs. Why?

In the current economy people trade labor for money. But without enough work people wont’ be able to earn money. What then? Brain thinks we might erect housing for the unemployed since you can’t live without a job, and we need to have a guaranteed income. But whatever we do, we had better start thinking about the kind of societal structures needed in a “robotic nation.”

Robots in 2015

Overall Summary

We Will Replace all the Pilots – and then

Robots in Retail – but we won’t

Create New Jobs – which means there will be

A Race to the Bottom – so

Where Do We Want to Go?

If you went back to 1950 you would find people doing most of the work just like they do in 2000. (Except for ATM machines, robots on the auto assembly line, automated voice answering systems, etc.) But we are on the edge of the robotic nation and half the jobs will be automated in the near future. Robots will be popular because they save money. For example, if an airline replaces expensive pilots, the money saved will give them a competitive advantage over other airlines. We’ll feel sorry for the pilots at first, but forget about them when the savings are passed on to us. Next will be the retail jobs and then others will follow. What about new job creation? After all, the model T created an automotive industry. Won’t the robotic industry do the same? No. Robots will assemble robots and engineering and sales jobs will go to those willing to work for less.

The robotic nation will have lots of jobs—for robots! Our economy does not create many high paying jobs. (And for those there is intense competition.) Instead there is a “race to the bottom.” A race to pay lower wages and benefits to workers and, if technologically feasible, to eliminate them altogether. Robots will make the minimum wage—which has declined in real dollars for the last forty years—irrelevant; there will be no high paying jobs to replace the lost low-paying ones. So where do we want to go? We are on the brink of massive unemployment unknown in American history, and everyone will suffer because of it. We need to answer a fundamental question: How do we want the robotic economy to work for the citizens of this nation?

Robotic Freedom

Overall Summary

The Concentration of Wealth – is accelerating bringing about

A Question of Freedom – why not let us be free to create

Harry Potter and the Economy – which leads us to

Stating the Goals – increase human freedom by weaning away from unfulfilling labor by

Capitalism Supersized – economic system that provides for all people which has

The Advantages of Economic Security – better for everyone because

You, Personally, and the Robots – because even your job is vulnerable.

We are on the leading edge of a robotic revolution that is beginning with automated checkout lanes; the pace of this change will accelerate in our lifetimes. Furthermore, the economy will not absorb all these unemployed. So what can we do to adapt to the catastrophic changes that the robotic nation will bring?

People are crucial to the economy. But increasingly there is a concentration of wealth in the hands of a few–the rich make more money and the workers make less. With the arrival of robots, all the income of corporations will go to the shareholders and executives. But this automation of labor—robots will do almost all the work 100 years from now—should allow people to be more creative than ever. Can we design the economy to do this? Why not design an economy where we abandon the “work or don’t eat” philosophy?

This is a question of freedom. Consider J.K. Rowling, author of the Harry Potter books. Amazingly she wrote them while on welfare and would not have done so without public support. Think how much human potential we lose because people have to work to eat. How much music, art, science, literature, and technology have never been created because people had to work. Consider that Linux, one of the world’s best operating systems, was created by people in their spare time. Why not create an economic model that encourages this kind of productivity? Why not create an economic model where we don’t have to hope the aged die before they collect too much social security, where we don’t have so many working poor, or people sleeping in the streets? Brain says “we are entering an historic era that has the potential to completely change the human condition.”

Brain argues that we shouldn’t ban robots because that leads to economic stagnation and lots of toilet cleaning. Instead he states the goals: raise the minimum wage; reduce the work week; and increase welfare systems to deal with unemployment. What is needed is a complete re-thinking of economic goals. The primary goal of the economy should be to increase human freedom. We can do this by using robotic workers to free people to: choose the products; start the businesses, creative projects; and use their free time as they see fit. We need not be slaves to the sixty hour work week “the antithesis of freedom.”

The remainder of the article offers specific suggestions (supersize capitalism, guaranteed economic security) of how we would fund a society in which persons actualize their potential to create art, literature, science, music, etc. without the burden of wage slavery. The advantages of such a system would be significant. (If all this seems fanciful, consider how fanciful our world would be to the slaves and serfs that most humans have been throughout history.) Brain says we are all vulnerable to the coming robotic nation.Let us then rethink our world, and welcome the robotic workers who will give us the time and the the freedom we all so desperately desire.

“Robotic Nation FAQ”

Question 1 - Why did you write these articles? What is your goal? Answer - Robots will take over half the jobs by 2030 and this will have disastrous consequences for rich and poor alike. No one wants this. I’d like to plan ahead.

Question 2 - You are suggesting that the switchover to robots will happen quickly, over the course of just 20 to 30 years. Why do you think it will happen so fast? Answer - Consider the analogy to the auto or computer revolutions. Once things get going, they proceed rapidly. Vision, CPU power, and memory are currently holding robots back—this will change. Robots will work better and faster than humans by 2030-2040.

Question 3 – In the past technological innovation created more jobs, not less. When horse-drawn plows were replaced by the tractor, security guards by the burglar alarm, craftsman making things by factories making them, human calculators by computers, etc., it improved productivity and increased everyone’s standard of living. Why do you think that robots will create massive unemployment and other economic problems? Answer - First, no previous technology replaced 50% of the labor pool. Second, robotics won’t create new jobs. The work created by robots will be done by robots. Third, we are creating a second intelligent species which competes with humans for jobs. As this new species gets better, it will do more of our work. Fourth, past increases in productivity meant more pay and less work but today worker wages are stagnant. Now productivity gains result in concentration of wealth. This may work itself out in the long run, but in the short run it is devastating.

Question 4 – There is no evidence for what you are saying, no economic foundation for your proposals. Answer – Just Google ‘jobless recovery,’” for the evidence. Automation fuels production increases but does not create new jobs.

Question 5 – What you are describing is socialism. Why are you a socialist/communist? Answer – I am a capitalist who has started three successful businesses and written a dozen books. “I am all for free markets, innovation and investment.” Socialism is the view that producing and distributing goods is done collectively by centralized governmental planning. He argues that individuals should own the means of producing and be free “to earn whatever they can with their products, services, and innovations.” By giving consumers a share of the wealth–which they won’t be able to earn with work–we will “enhance capitalism by creating a large, consistent river of consumer spending. It is also a way of providing economic security to every citizen…” Communism is usually identified by the loss of freedom and choice, whereas he wants people to have “economic freedom for the first time in human history…”

Question 6 – Why do you believe that a $25,000 per year stipend for every citizen is the solution to the problem? Answer - With robots doing all the work, we will finally have an opportunity to do this, which is better for everyone.

Question 7 – Won’t your proposals cause inflation? Answer - Tax rebates, similar to his proposals, don’t cause inflation. Neither do taxes, social security or other programs that re-distribute wealth.

Question 7a – OK, maybe it won’t cause inflation. But there is no way to give everyone $25,000 per year. The GDP is only $10 trillion. Answer - Brain argues that we should do this gradually. Remember $150 billion, about what the US spent on the Iraq war in 2003, is $500 for every man, woman, and child in the US. It isn’t that much in our economy. At the moment our government collects about $20,000 per household in taxes each year and so “it is very easy to imagine a system that pays US citizens $25,000 per year.”

Question 7b – Is $25,000 enough? Why not more? Answer - “As the economy grows, so should the stipend.”

Question 8 – Won’t robots bring dramatically lower prices? Everyone will be able to buy more stuff at lower prices. Answer - True. But current trends show that most of the wealth will end up in the hands of a few. Also, if you have no wealth it won’t matter that prices are lower. To let every citizen benefit from the robotic nation distribute the wealth to all.

Question 9 – Won’t a $25,000 per Year Stipend Create a Nation of Alcoholics? Answer – Brain notes this is a common question since many people assume that if we aren’t forced to due hard labor we’ll just do nothing or drink all day. He says he has no idea where this fear comes from (probably from political, philosophical, moral, and religious ideas promulgated by certain groups.) He dispels the idea with examples: a) he supports his wife who works at home; b) his in-laws are retired and live on a pension and social security; c) he has independently wealthy friends; d) he knows students supported by loans; and e) many are given free education and training. None of these people are lazy or alcoholics! (Perhaps its the reverse, with no possible source of income people give up.)

Question 9a – Yes, stay-at-home moms and retirees are not alcoholic parasites, but they are exceptions. They also are not productive members of the economy. Society will collapse if we do what you are talking about. Answer - Everyone participates in the economy by spending money. Unless there are people with money there’s no economy. The cycle of getting paid by a paycheck and spending it at businesses who get the money from customers is just that–a cycle—which will stop if people have no money. And giving a stipend won’t stop people from trying to make more money, create, invent or play. Some people will become alcoholics though, just as they do now, but Brain thinks we’ll have less lazy alcoholics “if we give them enough money to live decent, dignified lives…”

Question 10 – Why not let capitalism run itself? We should eliminate the minimum wage, welfare, child labor laws, the 40-hour work week, antitrust laws, etc. Answer - “…because of the power of economic coercion.” This economic power is why companies pay wages of a few dollars a week in most parts of the world. “We, The People, should enact the stipend to give ourselves true economic independence.”

Question 11 - Why didn’t you include the whole world in your proposals–why are you U.S. centric? Answer - Ideally, the global economy would adopt these proposals.

Question 12 – I love this idea. How are we going to make it happen? Answer – We should spread the word.

Thanks you Marshall Brain for such an uplifting vision.

1. The articles in their entirety can be found at http://www.marshallbrain.com/

April 8, 2014

A Review of Martin Rees’, Our Final Hour

Our Final Hour: A Scientist’s Warning

Martin Rees is one of the most distinguished theoretical astrophysicists in the world. He has held some of the most honored positions in science, among which is his current title–England’s Astronomer Royal. It has been more than ten years since Rees published, and I first read, Our Final Hour: A Scientist’s Warning: How Terror, Error, and Environmental Disaster Threaten Humankind’s Future in this Century—On Earth and Beyond.(Interestingly, the book’s title when published in England was Our Final Century: … I have heard they changed the title to make the issue more dramatic for American audiences.) I thought it was time to revisit it.

Rees begins by acknowledging technology shock: “21st century science may alter human beings themselves—not just how they live.”1 He accepts the common wisdom that the next 100 years will see changes that dwarf those of the past 1000 years, yet he is skeptical about the validity of specific predictions. He gives numerous examples of forecasts that were wrong, of forecasts that were nearly impossible to make because a particular technology seemingly came out of nowhere, and of the forecasts that were never made—x-rays, nuclear energy, antibiotics, jet aircraft, computers, transistors, the internet, and more.

Despite these failed forecasts Rees insists: “Over an entire century, we cannot set limits on what science can achieve, so we should leave our minds open, or at least ajar, to concepts that now seem on the wilder shores of speculative thought. Superhuman robots are widely predicted for mid-century. Even more astonishing advances could eventually stem from fundamentally new concepts in basic science that haven’t yet even been envisioned and which we as yet have no vocabulary to describe.”2 In this context Rees argues that nanotechnology will enable computing power to progress according to Moore’s law for the next few decades, by which time computers will match the processing power of the human brain.

Rees, a most sober prognosticator, accepts as reasonable speculative claims concerning the malleability of our physical and psychic selves; there is a real possibility that our descendants will be immortal post-humans. With the caveat that present trends continue unimpeded, there are good reasons to think that some living now may live forever. He also accepts the plausibility of superintelligence: “A superintelligent machine could be the last invention humans ever make. Once machines have surpassed human intelligence, they could themselves design and assemble a new generation of even more intelligent ones. This could then repeat itself, with technology running towards a cusp, or ‘singularity, at which the rate of innovation runs away towards infinity.”3 Nonetheless he thinks such ideas exist on the fringes of science, bordering on science fiction, and he is not convinced that a singularity awaits our species even if science continues to advance unimpeded.

Thus I see Rees as forging a middle path. He recognizes the immense potential of scientific knowledge to transform reality, taking even the most fantastic predictions seriously, but he cautions us that some predictions are unlikely to ever come true. This brings us full circle back to the beginning of the book. Many forecasts will fail, many are impossible to make, and many things we don’t forecast will come to be. One of the main reasons for this, Rees says, is that technology doesn’t always proceed as fast as it would if there were only technical barriers to be overcome. There may be social, religious, political, ethical, or economic considerations that impede swift development of new technologies. In short, its hard to predict … especially the future!

Of course any prediction about the future comes with the caveat that we don’t destroy ourselves. Rees takes such extinction scenarios seriously. “Throughout most of human history, the worst disasters have been inflicted by environmental forces—floods, earthquakes, volcanoes, and hurricanes—and by pestilence. But the greatest catastrophes of the 20th century were directly induced by human agency…”4 What Rees has in mind are the nearly 200 million persons were killed by war, massacre, persecution, famine, etc. in the 20th century alone. (Despite such somber statistics Steven Pinker has argued that we live more peacefully than ever before in human history.) The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

Rees lists multiple extinction scenarios: global nuclear war; nuclear mega-terror; biothreats (the use of chemical and biological weapons); laboratory errors (for example, accidentally create a new virulent smallpox virus); nanotech “grey goo” (nanobots out of control that consume all organic matter—although this has recently been downplayed by Eric Drexler and others); particle physics experiments gone awry; environmental or climate change, asteroid impacts; and super-eruptions from Earth that block the sun. He notes that most of the threats to our survival come from us. Rees himself has wagered $1000 on the following proposition: “That by the year 2020 an instance of bioerror or bioterror will have killed a million people.”5

In the end Rees argues that one of two fates will befall humankind: 1) they will go extinct; or 2) they or their descendants will expand throughout space. Which will happen is unknown; after all it is hard to predict the future. Yet Rees books serves as a reminded that the human future is largely up to us.

1. Our Final Hour, 9.

2. Our Final Hour, 16.

3. Our Final Hour, 19.

4. Our Final Hour, 25.

5. Our Final Hour, 74.

April 7, 2014

On Living Well

Some interesting conversations yesterday caused me to think again about what makes a good life–specifically the role played by relationships and work. Some seemed to think important, productive, meaningful work was more important; others that relationships with family and friends were more important. I would say both are part of a good life, thus we should not mistake either as the whole of the good life.

This was exactly Aristotle’ position–we should not mistake a part of the goods for the whole of the goods. He thought that the good life consists in the possession, over the course of a lifetime, of all those things that are really good for us. What is really good for us corresponds to natural needs that are the same for all human beings. So what are the real goods that a person should obtain in order to live well? According to Aristotle they are:

1) bodily goods – health, vitality, vigor, and pleasure;

2) external goods (wealth) – food, drink, shelter, clothing, and sleep; and

3) goods of the soul – knowledge, skill, love, friendship, aesthetic enjoyment, self-esteem, and honor.

This list, or something like it, are referred to as “universal human goods.” But again it is a not a question of which good is the most important (the “summum bonum” or highest good), but that they are all important (the “totum bonum” or whole of the goods.) We error if we mistake a part for the whole.

Look again at the list to see why. Suppose I think only bodily goods are important. I do nothing but jog or lift weights all day, developing my body but not my mind, thereby missing the knowledge that is crucial to a good life. Or suppose I do nothing but accumulate wealth. I may have multiple cars, homes, and bank accounts, but I may have no friends. Again I have mistaken a good, wealth, for the whole of the goods. Consider the miser, asked Aristotle, who had wealth but no friends. Would we call him happy?

Even specific goods of the soul are susceptible to this analysis. Aristotle thougth that knowledge and friendship are unlimited good–we cannot have to much of them–but we can still mistake one of them for the whole of the goods. If I am the world’s greatest mathematician but have no friends or family, I do not live as well as I would otherwise. If I am a loving person but know nothing, I would live better if I were more knowledgeable.

The important point is the role that moderation plays in a good life. As Aristotle said, excellence is the mean between the extremes. Doing good work for the world, sacrificing for your family, or being a great scholar are all wonderful things to do, but they are part of living well, not the whole of a good life. Again, the good life consists in the possession, over the course of a lifetime, of all those things that are really good for us.

I always thought this was sound advice.

April 6, 2014

The Weather

“Hush, please. That is enough, Margaret. If you cannot think of anything appropriate to say, you will please restrict your remarks to the weather.” (Mrs. Dashwood to her daughter in the movie adaptation of Jane Austin’s “Sense and Sensibility.” 1995)

The weather is the quintessential default topic. If you don’t want to discuss “heavy” topics like politics or religion, you talk about the weather. It’s amazing how interested humans are in the weather. We have multiple internet sites devoted to it, local TV channels discuss it throughout the day, and an entire cable channel talks weather 24 hours a day!

When I was a child we had three basic sources for the weather: 1) the newspaper; 2) the weather segment of the TV news and; 3) the groundhog “Punxsutawney Phil .” Let me discuss each in turn, especially for my younger audience.

This “newspaper” was a product made of wood pulp upon which ink was pressed–in the old days by a linotype machine–then loosely bound together and subsequently bought from a vendor or delivered to your home by a person who threw this bundled-up paper on your lawn, driveway, doorstep, or your neighbor’s yard. If it was raining this paper got wet, rendering some of it unreadable. After walking outside to pick it up, you read it, washed the residual newspaper ink off your fingertips, (else you would touch your face and look like a chimney sweep) and then discarded the remains in the trash because there was no recycling in those days. Then the process was repeated day and day, year after year, decade after decade until … we invented the internet.

This “TV weather” was like our modern TV weather only everything on the screen existed colorless in shades of gray, it had an audience, and you couldn’t skip the commercials. It was also different because the people stood still and calmly read the weather against the background of immovable maps that you couldn’t read. Now they “put the clouds in motion” against the background of virtual 3D maps taking ten minutes to give you thirty seconds worth of information. The basic problem with the old-time weather was that their predictions were not good. If they said it would be sunny … bring your umbrella.

As for the groundhog, my mother seemed to literally believe in this prognosticator, so I planned the start of baseball season around the groundhog’s predictions. If told it would be an early spring, I put my winter clothes away and oiled my baseball glove; told it would be a late spring, I did the opposite. Later, when I was about 40, I saw the movie “Groundhog Day” and realized there was nothing scientific about the groundhog. Just kidding, I already knew that! (I also discovered that “Groundhog Day” is one of the greatest films ever made; it is largely about Nietzsche’s doctrine of eternal recurrence.)

Finally, there was one other option. We could also dial a special number called “time and temperature” and get those two pieces of data anytime, assuming the number wasn’t busy. Dialing on a rotary dial phone whose cord tethered you to the wall … all so you knew the time and the temperature.

Of course the weather forecast wasn’t very reliable in the day before “Doppler radar” and satellites. Weather is notoriously difficult to forecast–it is a chaotic system subject to small perturbations–and the fact that it is so reliably predicted today is a testimony to the power of science. Science, not Nostradamus, really predicts the future. (That’s why we know when Halley’s comet will come next!) Now we have nearly perfect daily forecasts and even four or five days into the future the predictions are quite good.

When it comes to weather, people have different preferences. Some like it hot, like Marilyn Monroe, some love the snow, some hate winter, and some love four seasons. I once knew a philosophy professor in Las Vegas who told me “perpetual sunshine is depressing.” When she told me this I thought of all those souls back in Buffalo who dreamed of leaving behind three feet of snow for that depressing perpetual sunshine. I was talking to a visitor from New York yesterday who said they would hate the winter cloudiness here in Seattle. Of course I lived in Cleveland for years and a winter of mild temperatures and a few clouds is great–I can play golf in January. But then to each his or her own.

So what is the perfect weather? Parts of Hawaii are in the 70s almost all the time so that’s great. But if one lived there would one say “perpetual 70s is depressing.” Maybe a near perfect place would be one that had multiple climates close by and you could constantly migrate between them. If you lived in a place with a rain shadow for instance, you could drive a few miles and experience plenty of rain. Or you could live on say the dry east side of the Cascades, and journey just a bit to the west for more rain. Or you could have an advanced climate controlled system in your own house and change the weather continually, or stick forever with the one you liked.

Very interesting how much we care about the weather. I would guess there are two main causes of this fascination. First, in our evolutionary history weather was crucial to our survival–so there must be some small genetic component to this concern, some innate desire to know the weather. Second, cultural amplifies this concern since we do a lot outdoors–picnics, hikes, ballgames, parades, etc. So we simply want to know if it will rain or snow.

Still, the most important thing to remember about the weather comes Mark Twain:

“It is best to read the weather forecasts before we pray for rain.”

April 5, 2014

Aristotle, Robots, and a New Economic System

My post of March 31, 2014,”Do We Need A New Economic System?” discussed the role that technology plays in both eliminating jobs and increasing income inequality. That post mentioned Jaron Lanier, whose recent book “Who Owns the Future?” touches on this topic. Early in the book Lanier quotes from Aristotle’s Politics:

If every instrument could accomplish its own work, obeying or anticipating the will of others, like the statues of Daedalus, or the tripods of Hephaestus, which, says the poet, ”of their own accord entered the assembly of the Gods;”if, in like manner, the shuttle would weave and the plectrum touch the lyre without a hand to guide them, chief workmen would not want servants, nor masters slaves.

Aristotle saw that the human condition largely depends on what machines can and cannot do, and we can imagine that machines will do much more. If machines did more of our work he thought, everyone, even slaves, would be freer. How then would Aristotle’s respond to today’s technology? Would he advocate for a new economic system that met the basic needs of everyone, including those who no longer needed to work; or would he try to eliminate those who didn’t own the machines that run society?

Surely this question has a modern ring. If, as Lanier suggests, only those close to the computers that run society have income, then what happens to the rest of us? What happens to the steel mill and auto factory workers, to the butchers and bank tellers, and, increasingly, to the accountants, professors, lawyers, engineers, and physicians when artificial intelligence improves? (Lanier discusses how this will come about in his book.)

Lanier worries that automata, especially AI and robotics, create a situation where we don’t have to pay others. Why pay for maid service if you have a robotic maid, or for software engineers if computers are self-programming? Aristotle used music to illustrate the point. He said that it was terrible to enslave people to make music (playing instruments in his time was undesirable and labor intensive) but we need music so someone must be enslaved. If we had machines to make music or could get by without it, that would be better. Music was an interesting choice because now so many want to play music for a living, although almost no one makes money for their music through internet publicity. People may be followed online for their music (or their meaning of life blog), but they don’t get paid for it.

So what do we do? Should we eliminate the apparently unnecessary people, so we no longer have to deal with them? (Remember that virtually all of us will become unnecessary in the near future!) Should we retire to the country or the gated community where our apparent safety is purchased by the empire’s military outposts and their paid mercenaries around the world? Where the first victims of society sleep on street corners, populate our prisons, endure unemployment, or involuntarily join our voluntary armies?.(Remember all you accountants, attorneys, professors and software engineers, this world is coming for you too!) Or should we recognize how we benefit from each other, from our diverse temperaments and talents, from the safety and sustenance we achieve in numbers?

So a question we now face is this: what happens to the extra people, almost all of us, when technology does all the work or one is unpaid for the work that the machines cannot do? Are the rest of us killed or slowly starve? Surprisingly Lanier thinks these questions are misplaced. After all human intelligence and human data drives the machines. Rather the issue is how we think about the work that machines can’t do.

I think that Lanier is on to something here. We can think of the non-automated work as anything from essential to frivolous. If we think of it as frivolous, then so too are the people that produce it. If we don’t care about human expression in art, literature, music, play or philosophy, then why care about the people that produce it.

But even if machines write better music or poetry or blogs about the meaning of life, we could still value human generated effort. Even if machines did all of society’s work we could still share the wealth with people who wanted to think and write and play music. Perhaps people just enjoy these activities. No human being plays chess as well as the best supercomputers, but people still enjoy playing chess; I don’t play golf as good as Tiger Woods, but I still enjoy it.

I’ll go further. Suppose someone wants to sit on the beach, surf, ski, golf, smoke marijuana, watch TV, or collect coins. What do I care? Perhaps that’s a much better society than one informed by the Protestant work ethic. A society of stoned, TV watching, skiers, golfers and surfers would probably be a happier one than we live in now. (The evidence shows that the happiest countries are those with the strongest social safety nets, the ones with the most paid holidays and generous vacation and leave policies; the Western European and Scandinavian countries.) People would still write music and books, lift weights, volunteer, and visit their grandchildren. They would not turn into drug addicts!

This is what I envision. A society where machines do all the work that humans don’t want to do; and humans would express themselves however they liked, without harming others. A society much more like Denmark and Norway, and much less like Alabama and Mississippi. Yes I believe that all persons are entitled, yes entitled, to the minimal amount it takes to live a decent human life. All of us would benefit from such an arrangement, as we all have much to contribute to each other. I’ll leave with some words inspiring words from that young auto-didactic Eliezer Yudkowsky

There is no evil I have to accept because ‘there’s nothing I can do about it’. There is no abused child, no oppressed peasant, no starving beggar, no crack-addicted infant, no cancer patient, literally no one that I cannot look squarely in the eye. I’m working to save everybody, heal the planet, solve all the problems of the world.

More on Needing a New Economic System

My post of March 31, 2014,”Do We Need A New Economic System?” discussed the role that technology plays in both eliminating jobs and increasing income inequality. That post mentioned Jaron Lanier, whose recent book “Who Owns the Future?” touches on this topic. Early in the book Lanier quotes from Aristotle’s Politics:

If every instrument could accomplish its own work, obeying or anticipating the will of others, like the statues of Daedalus, or the tripods of Hephaestus, which, says the poet, ”of their own accord entered the assembly of the Gods;”if, in like manner, the shuttle would weave and the plectrum touch the lyre without a hand to guide them, chief workmen would not want servants, nor masters slaves.

Aristotle saw that the human condition largely depends on what machines can and cannot do, and we can imagine that machines will do much more. If machines did more of our work he thought, everyone, even slaves, would be freer. How then would Aristotle’s respond to today’s technology? Would he advocate for a new economic system that met the basic needs of everyone, including those who no longer needed to work; or would he try to eliminate those who didn’t own the machines that run society?

Surely this question has a modern ring. If, as Lanier suggests, only those close to the computers that run society have income, then what happens to the rest of us? What happens to the steel mill and auto factory workers, to the butchers and bank tellers, and, increasingly, to the accountants, professors, lawyers, engineers, and physicians when artificial intelligence improves? (Lanier discusses how this will come about in his book.)

Lanier worries that automata, especially AI and robotics, create a situation where we don’t have to pay others. Why pay for maid service if you have a robotic maid, or for software engineers if computers are self-programming? Aristotle used music to illustrate the point. He said that it was terrible to enslave people to make music (playing instruments in his time was undesirable and labor intensive) but we need music so someone must be enslaved. If we had machines to make music or could get by without it, that would be better. Music was an interesting choice because now so many want to play music for a living, although almost no one makes money for their music through internet publicity. People may be followed online for their music (or their meaning of life blog), but they don’t get paid for it.

So what do we do? Should we eliminate the apparently unnecessary people, so we no longer have to deal with them? (Remember that virtually all of us will become unnecessary in the near future!) Should we retire to the country or the gated community where our apparent safety is purchased by the empire’s military outposts and their paid mercenaries around the world? Where the first victims of society sleep on street corners, populate our prisons, endure unemployment, or involuntarily join our voluntary armies?.(Remember all you accountants, attorneys, professors and software engineers, this world is coming for you too!) Or should we recognize how we benefit from each other, from our diverse temperaments and talents, from the safety and sustenance we achieve in numbers?

So a question we now face is this: what happens to the extra people, almost all of us, when technology does all the work or one is unpaid for the work that the machines cannot do? Are the rest of us killed or slowly starve? Surprisingly Lanier thinks these questions are misplaced. After all human intelligence and human data drives the machines. Rather the issue is how we think about the work that machines can’t do.

I think that Lanier is on to something here. We can think of the non-automated work as anything from essential to frivolous. If we think of it as frivolous, then so too are the people that produce it. If we don’t care about human expression in art, literature, music, play or philosophy, then why care about the people that produce it.

But even if machines write better music or poetry or blogs about the meaning of life, we could still value human generated effort. Even if machines did all of society’s work we could still share the wealth with people who wanted to think and write and play music. Perhaps people just enjoy these activities. No human being plays chess as well as the best supercomputers, but people still enjoy playing chess; I don’t play golf as good as Tiger Woods, but I still enjoy it.

I’ll go further. Suppose someone wants to sit on the beach, surf, ski, golf, smoke marijuana, watch TV, or collect coins. What do I care? Perhaps that’s a much better society than one informed by the Protestant work ethic. A society of stoned, TV watching, skiers, golfers and surfers would probably be a happier one than we live in now. (The evidence shows that the happiest countries are those with the strongest social safety nets, the ones with the most paid holidays and generous vacation and leave policies; the Western European and Scandinavian countries.) People would still write music and books, lift weights, volunteer, and visit their grandchildren. They would not turn into drug addicts!

This is what I envision. A society where machines do all the work that humans don’t want to do; and humans would express themselves however they liked, without harming others. A society much more like Denmark and Norway, and much less like Alabama and Mississippi. Yes I believe that all persons are entitled, yes entitled, to the minimal amount it takes to live a decent human life. All of us would benefit from such an arrangement, as we all have much to contribute to each other. I’ll leave with some words inspiring words from that young auto-didactic Eliezer Yudkowsky

There is no evil I have to accept because ‘there’s nothing I can do about it’. There is no abused child, no oppressed peasant, no starving beggar, no crack-addicted infant, no cancer patient, literally no one that I cannot look squarely in the eye. I’m working to save everybody, heal the planet, solve all the problems of the world.

April 3, 2014

Review of Paul Thagard’s, “The Brain and the Meaning of Life”

The Brain and the Meaning of Life

Paul Thagard is professor of philosophy, psychology, and computer science and director of the cognitive science program at the University of Waterloo in Canada. His recent book, The Brain and the Meaning of Life (2010), is the first book length study of the implications of brain science for the philosophical question of the meaning of life.

Thagard admits that he long ago lost faith in his childhood Catholicism, but that he still finds life meaningful. Like most of us, love, work, and play provide him with reasons to live. Moreover, he supports the claim that persons find meaning this way with evidence from psychology and neuroscience. (He is our first writer to do this explicitly.) Thus his approach is naturalistic and empirical as opposed to a priori and rationalistic. He defends his approach by noting that thousands of years of philosophizing have not yielded undisputed rational truths, and thus we must seek empirical evidence to ground our beliefs.

While neurophysiology does not tell us what to value, it does explain how we value—we value things if our brains associate them with positive feelings. Love, work, and play fit this bill because they are the source of the goals that give us satisfaction and meaning. To support these claims, Thagard notes that evidence supports the claim that personal relationships are a major source of well-being and are also brain changing. Similarly work also provides satisfaction for many, not merely because of income and status, but for reasons related to the neural activity of problem solving. Finally, play arouses the pleasures centers of the brain thereby providing immense psychological satisfaction. Sports, reading, humor, exercise, and music all stimulate the brain in positive ways and provide meaning.

Thagard summarizes his findings as follows: “People’s lives have meaning to the extent that love, work, and play provide coherent and valuable goals that they can strive for and at least partially accomplish, yielding brain-based emotional consciousness of satisfaction and happiness.”[i]

To further explain why love, work, and play provide meaning, Thagard shows how they are connected with psychological needs for competence, autonomy, and relatedness. Our need for competence explains why work provides meaning, and why menial work generally provides less of it. It also explains why skillful playing gives meaning. The love of friends and family is the major way to satisfy our need for relatedness, but play and work may do so as well. As for autonomy, work, play, and relationships are more satisfying when self-chosen. Thus our most vital psychological needs are fulfilled by precisely the things that give us the most meaning—precisely what we would expect.

Thagard believes he has connected his empirical claim the people do value love, work, and play with the normative claim that people should value them because these activities fulfill basic psychological needs for competence, autonomy, and relatedness. Our psychological needs when fulfilled are experienced as meaning.

[i] Paul Thagard, The Brain and the Meaning of Life (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), 165.