John G. Messerly's Blog, page 11

January 24, 2024

Science Has No Role To Play In An Analysis Of Free Will

by Laurence Houlgate

(Emeritus professor of philosophy at California Polytechnic State University)

Regarding your excellent review of the free will problem, I have two questions. First, when you say that the ability of the neurons to deliberate emerges from the water and chemicals that make up our bodies (along with our evolved consciousness), you are making an empirical judgment. As such, it requires proof/evidence. Are there any experiments that have been performed to show that this claim is true? If so, are the experiments similar to what happens when I make pancakes? I begin with flour, water, milk, egg, etc. and I end up with a mixture suitable for pouring on the griddle. The mixture is an observable simple chemical change. But even if there is evidence that the ability to deliberate emerges as a complex chemical soup, how does the determinist use it to prove that we have no free will when we walk, talk, eat, and do anything else that moves the body?

Second, in the section where you say that “I live as if I make free choices,” my question is why don’t you come right out and say, “I make free choices.” I don’t like the “as if” part. It implies that you are pretending to live making free choices. For example, compare “I made a free choice when I bought my new car,” with “I pretended to make a free choice when I bought my new car,” or “I believe I made a free choice when I bought my new car, but I’m not sure that it was a free choice.”

Finally, what I don’t like about determinist arguments to prove that we do not have free will is that they are using empirical observations and experiments to solve a philosophical problem. Philosophical problems are about concepts and their relationship to other concepts. As such, philosophy is not informative about the world (Gilbert Ryle). When we ask the question “Do we have free will” we are asking a question about the concept Free Will and that question can only be answered by an analysis of the concept as it is used by us in ordinary language, e.g. “Did you hand over your wallet to that man of your own free will, or did he force you to hand over your wallet?” Science has no role to play in this analysis.

January 21, 2024

Theories Of What Makes You, You

From 3 Quarks Daily, Nov. 27, 2023, by TIM SOMMERS*

One time, this guy handed me a picture of him and said, ‘Here’s a picture of me when I was younger.’ Every picture is of you when you were younger. – Mitch Hedberg

You are your soul

The trouble with this theory is not that it usually has a religious basis. That might be trouble later, but initially the trouble is that it is not very helpful. I am my soul. So, what’s my soul? Is the soul some mysterious, ghostly thing or a Platonic form or is it just whatever is essential to who I am? If the answer is that the soul is whatever is essential to who I am, this seems like just a restatement of the question.

Keep in mind, the great innovation of Christianity was not the soul, an idea that’s been around at least since Plato and Aristotle (who thought we had three souls). The Christian innovation was bodily resurrection.

You are your ego.

The ego may just be the secular soul. Descartes’ version of the ego theory, the most influential, is that a person is a persisting, purely mental, thing. But like the soul it’s hard to unpack the ego in an informative way. It is whatever unifies our consciousness. We survive as the continued existence of a particular subject of experiences, and that explains the unity of a person’s life, i.e., the fact that all the experiences in this life are had by the same person. This is circular, of course. Further, on this view, what happens if I fall into a dreamless sleep? Or get hit on the head and black out? Go in and out of a coma? Am fully anesthetized? When I wake up and start having experiences again, how do I know I am the same ego? How do I know that the ego is a persistent thing at all? Later, we will see what Hume has to say about this.

In the meantime, we are going to need a better theory of the ego or soul before either is going to be useful as a theory of personal identity.

You are your body.

Believe it or not, in Modern Philosophy, “animalism” – the view that you are your body – is a latecomer to the party. It’s easiest to explain by comparison. Suppose we take the anti-animalist view that identity is some kind of psychological, rather than physical, continuity. Here’s one animalist counter argument. Fetuses, at least early on, have no mental capacities. You can’t be psychologically continuous with a being that has no such capacities. But you used to be a fetus. So, whatever you are, it’s not a matter of psychological continuity.

I am not sure about this argument. Carl Sagan used to say, “We are made of star stuff…The nitrogen in our DNA, the calcium in our teeth, the iron in our blood, the carbon in our apple pies were made in the interiors of collapsing stars.” But notice, he doesn’t say that we used to be star stuff. Did we also use to be an unfertilized egg and a sperm at the same time?

I am not sure that settles the argument, but here’s a broader challenge.

You are your brain.

I like to call this view reductive neuro-animalism. But no one else in the world calls it that, so I probably shouldn’t.

Suppose identical twins are in a car crash together. Twin A has their body destroyed, except for their brain, and Twin B has their brain destroyed, but their body is fine. Surgeons manage to put Twin A’s brain into Twin B’s body and save one of them. But which one?

By volume, Twin B makes up the bulk of the survivor. But the brain is A’s brain. If you think that A is the survivor, that suggests that you believe that you are not your body as a whole, but one specific subpart. You are your brain.

You are your memories.

There are a number of pretty science-fictional challenges to the view that you are your brain. If you can be uploaded into a computer, teleported, or bodily resurrected, then you are probably not your brain. But let’s keep it simple.

Suppose one day we can treat certain brain issues by swapping out some biological neurons with artificial ones. Suppose over a long period of time you are treated until the point where none of your neurons are your original neurons. If you remain psychologically identical (or differ only in small, natural ways), are you still the same person? If so, you are not your brain.

The most influential psychological theory of identity is John Locke’s memory theory. You are the same person over time because of your memories. They make you, you. Here are two problems with that.

You don’t remember so much. You probably don’t remember being five, maybe, not even twenty-five (if you are old enough). We could just say if you lose enough memories, you are not you. But one worry is that most of us don’t have enough memories to count as a continuous person over our complete life. A possible fix is the idea of chain-connectedness. I don’t have to remember being five to be that person. I can remember being a twenty-five-year-old person who remembered themselves as five.

There’s a weirder problem. As it stands, the memory theory, like the ego theory, is circular. What makes me, me, is the memories that I have. Notice the “I.” I need the memories to be mine. But that means I need to define “mine” before I attribute memories to me.

One of the most influential responses to this problem is still weirder. Psychological continuity might be based on quasi-memories. Quasi-memories provide knowledge and/or acquaintance with past experiences without assuming that the rememberer and the experiencer are the same person. Maybe, all quasi-memories are also, in fact, regular old memories. Or maybe one day we will be able to share memories in some way. Either way, it’s not circular to say that psychological continuity is based on quasi-memories, rather than memories. Or, anyway, that’s what I have been told.

So, we could say…

You are your chain-connected, quasi-memories.

But memories hardly exhaust the categories of psychological continuities plausibly connected to our identity, including basic desires, character traits, tastes, thoughts, beliefs, and intentions. Since we don’t have to sort and pare this list down today, let’s keep it vague and say…

You are your chain-connected, quasi-psychological continuities.

So, there you go. That wasn’t as hard as you thought, right? Wait. Hume wants to say something.

“For my part, when I enter most intimately into what I call myself, I always stumble on some particular perception or other, of heat or cold, light or shade, love or hatred, pain or pleasure. I never can catch myself at any time without a perception, and never can observe anything but the perception…. If anyone, upon serious and unprejudiced reflection thinks he has a different notion of himself, I must confess I can reason no longer with him. All I can allow him is, that he may be in the right as well as I, and that we are essentially different in this particular. He may, perhaps, perceive something simple and continu’d, which he calls himself; tho’ I am certain there is no such principle in me.”

Derek Parfit calls this view the Bundle Theory. Buddha may have been the first bundle theorist. He taught “anatta” or the No-Self view.

The bundle theory does not deny that we are the confluence of a number of chain-connected, quasi-psychological continuities. They deny that these persist over an entire human life and that we can always distinguish continuities across person. We have quasi-psychological chain-connections with people who are not us, after all. Which means that there’s not always an answer (much less a binary answer) to the question of whether you are the same person over time. In fact, being you turns out to be a matter of degree.

I have said more about this elsewhere. But I will end here now. Or anyway the person that replaced me while I was writing this will end it here.

Reprinted with PermissionJanuary 15, 2024

Physics and Free Will

[image error]

Pursuant to my last post I would like to further explore the relevance of contemporary physics for the question of free will. The key idea made by physicists like Sabine Hossenfelder and others is that “The currently established laws of nature are deterministic with a random element from quantum mechanics. This means the future is fixed except for occasional quantum events that we cannot influence.” In other words, what we do today follows from the state of the universe yesterday and so on all the way back to the Big Bang. Still, we believe we have free will because we don’t know the results of our thinking before we have done it.

One of the only ways out of this reductionism of the macroscopic to the microscopic is through strong emergence. However many physicists argue that strong emergence isn’t possible. They claim that higher-level properties of a system derive exclusively and completely from lower levels (particle physics) and that there is no evidence that strong emergence is real.

Yes, we may feel we have free will but just as we understand that the “now” is an illusion in relativity theory, physics helps us see that free will is also an illusion. Again the salient point is that the future is fixed except for occasional quantum events that we cannot influence. And whether this eliminates free will depends on how you define free will.

This is a powerful argument and I don’t possess the expertise to resolve the issue. Perhaps none of us possess the intellectual wherewithal to resolve complex questions. Or perhaps our deepest questions—how did the universe begin; are we free; what does life mean—are irresolvable in principle.

At this point, I can appeal to my intuition and say “but it seems to me …” But intuition misleads us all the time. Afterall the earth is not flat and stationary, nor is the sun as small as it appears to my eye! Science constantly corrects our intuitions. And from the perspective of physics free will, as we usually define it, seems almost impossible.

Nonetheless from the perspective of biology free will might make sense if complex systems do take on properties that their constitutive elements don’t possess. Again I don’t know the answer to this question nor to other big questions. So in the end, I don’t know if we are free or not.

As I’ve written before, we simply live and die in a world we don’t totally understand. This situation may not be ideal, but I’ve come to terms with it.

January 14, 2024

What Is Free Will & Do We Have It?

[image error]

My last two posts have been by professional philosophers discussing the perennial question of whether or not human free will exists. (I have also published summaries of the free will/determinism question here and here.) But I thought my readers might be interested in where I stand on the issue so here goes.

DISCLAIMER

I’ll begin with a disclaimer. I’m not an expert on the free will problem. I have not published in the area and teaching the issue in introductory philosophy classes does not imply expertise. Philosophers have debated the issue for centuries and some contemporary philosophers have written multiple books on the subject. By comparison, my views on the issue are shallow. Nonetheless, at the request of a regular reader, I’ll share my thoughts.

COMPATIBILISM

Quoting from Professor Houlgate’s post, for a compatibilist

“free will” simply means that there are no impediments to what I am doing. When the jailer says to the prisoner who has served his term, “You are now free to go” he means that there is no impediment to prevent the prisoner from walking out of the jail. The impediment is the jail cell. The cell door is open. The prisoner is free to go.

… [Furthermore] “You are free to go” is perfectly compatible with the claim that the prisoner’s choice to leave the jail is an event that has a sufficient causal explanation.

This is no more than a thumbnail sketch of compatibilism, as at a minimum we have to carefully define our terms as Professor Danaher tried to do in his essay. But note here that this conception of free will is limited, i.e., there is no “ghost in the machine” doing anything outside the laws of physics when we (apparently) make choices. But how can this be?

LIBET’S EXPERIMENTS

When I first started teaching free will I was strongly influenced by Libet’s experiments which suggest that unconscious processes in the brain are the true initiator of volitional acts, and free will therefore plays no part in their initiation. However, there have been many criticisms of that experiment. For example, the philosopher Daniel Dennett argues that no clear conclusion about volition can be derived from Libet’s experiments.

According to Dennett, ambiguities in the timings of the different events are involved. Libet tells when the readiness potential occurs objectively, using electrodes, but relies on the subject reporting the position of the hand of a clock to determine when the conscious decision was made. As Dennett points out, this is only a report of where it seems to the subject that various things come together, not of the objective time at which they actually occur.[69][70]

Or, as another philosopher put it,

At the neurophysiological level, it has not been shown convincingly that a neural ‘decision’ sufficient to cause the movement occurs before the time of awareness of the decision to move. Even if this could be shown, it would not undermine the conceptions of free will that are defended by most philosophers.

While the criticisms of Libet’s experiments don’t end the discussion, I’m now no longer convinced by those experiments.

NOT ALL KNEE JERK RESPONSES

Moreover while teaching the issue many arguments challenged my belief in hard determinism.

First, the behavior of a knee jerking after being hit by a small hammer or an iris contracting after being hit by a light is just different, according to Steven Pinker, than behavior

that engages vast amounts of the brain, particularly the frontal lobes, that incorporates an enormous amount of information in the causation of the behavior, that has some mental model of the world, that can predict the consequences of possible behavior and select them on the basis of those consequences. All of those things carve out the realm of behavior that we call free will. Which it is useful to distinguish from brute involuntary reflexes, but which doesn’t necessarily have to involve some mysterious soul.

I always found this argument relatively compelling.

I’M NOT A ROCK

Moreover, I often thought “We just aren’t rocks!” Yes, we may be 99% determined, but we aren’t as determined by casual forces as rocks are. This just seems so intuitively plausible. Now I realize the danger of basing arguments on intuition, but still, I’m not a rock. I may be a machine but I’m a different kind of machine than a rock is.

Ok, but how about a dog or a chimp? Perhaps I’m more free than they are but they’re more free than rocks too. Or perhaps some humans are more free than others—say because of education for example that leaves them with more options about what to believe. So free will, like consciousness, is a gradient.

Now again none of this means that there is a little soul or ghost in my head outside the laws of physics. That is a ridiculous belief in the world revealed by modern science. So how then to better explain?

AN EMERGENT PROPERTY?

It may seem trite but the best I can do is to say what we call free will is an emergent property. Consciousness emerged in the evolutionary process and what we call free will (which I think of as the ability to deliberate) emerged concurrently. When brains become sufficiently complex the whole takes on properties the part doesn’t possess. Again, this doesn’t mean that consciousness is supernatural or something magical beyond its parts but that those parts in a certain relationship or configuration possess properties that parts by themselves do not.

Or think of it this way. You and I are not just the water and the chemicals that make up our bodies. Nor or we just the atoms and molecules and ultimately sub-atomic particles that make up the water and chemicals. And we are not just these parts plus some ghost or soul that (somehow) has free will. We are all those parts in a certain configuration, a certain relationship. When you put all those neurons together in a certain way they take on properties that they don’t possess by themselves. And along with our evolved consciousness emerged the ability of the neurons to deliberate.

Nonetheless, I accept that most of what we do and think is relatively predictable. If I knew everything about someone’s genes and environment I could almost predict what they would think and do. I believe we have a tiny bit of what is usually called free will. And determinism is compatible with this narrow view of free will which means “not coerced.” I think genes and environment coerce us, but not completely.

LIVING AS IF WE ARE FREE

Let me also say that I live as if I make free choices. I don’t know what it would mean to live assuming that all of your choices are determined. So I go along assuming I’m making choices while recognizing that so much of what I do and believe is largely determined.

MOST PHILOSOPHERS ARE COMPATIBILISTS

Finally note that the question of free will (among others) was asked in a 2020 survey of almost 1800 academic philosophers, mainly from university departments in North America, Europe, and Australasia. The results:

Libertarian free will – 18.8%

Compatibilism – 59.2%

No free will – 11.2%

Other – 11.4%

January 7, 2024

Free Will: A Conceptual Framework

by John Danaher

Free will, if it exists, is a property of agency. It is something that agents, in virtue of their constitution, can exhibit that non-agents cannot. Furthermore, free will may be the most morally, spiritually, and existentially important property of human agency.

It has occurred to me that I might like to look at some recent papers on the topic of free will on this blog. Those papers tend to assume that the reader is familiar with the ins and outs of the contemporary debate on this issue. I don’t like to make those kinds of assumptions, partly because you never know who might be reading a blog, and partly because reacquainting oneself with the basics of an issue is always worthwhile.

This post offers a conceptual framework for analysing the contemporary debate on free will. The framework comes in three sections. The first section examines the nature of free will as a property of agency; the second section considers the intellectual significance of the debate; and the third section outlines some of the positions one can take up in this debate.

1. The Nature of Free Will

No one would deny that the term “free will” is ambiguous. A lot of conceptual baggage has been attached to those two simple words over the years. This is one reason why the debate over free will (even in the philosophical literature) can be so frustrating: different authors apply different meanings to the term and often end up talking past on another.

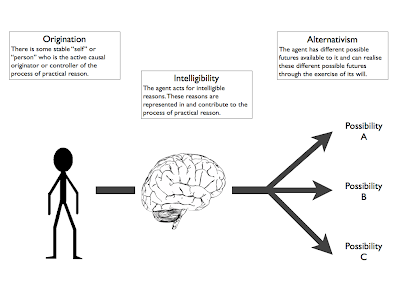

In an effort to cut through some of that confusion, I like to appeal to a model of free will that I first came across in Henrik Walter’s book The Neurophilosophy of Free Will[image error]. Walter’s contention is that when we talk about the property of free will, we are talking about a decision-making capacity with three components:

(i) Alternativism: this is the capacity to (meaningfully) choose between different possible futures. In other words, if X must choose whether to eat an apple or an orange, and if X chooses the orange, it must still be possible for X to choose the apple.(ii) Intelligibility: this is the capacity to act from intelligible reasons. In other words, X does not simply choose among possibilities at random, X chooses in accordance with reasons, intentions, desires and beliefs.(iii) Origination: this is the capacity to be the originator of actions. In other words, X is not simply a passive receptacle through which external causal forces exert themselves but is, in some sense, the active originator of causal forces.

There are two main advantages to thinking about free will in this way. First, by focusing on three elements, this model helps to avoid the pitfalls associated with thinking about only one of the elements. For example, most discussions of free will are preoccupied with the concept of alternativism. But a popular objection to this preoccupation is that an agent with alternativism and nothing else might amount to little more than a random choice-generator. This would not be the kind of morally salient choice with which we are concerned. The extra ingredients of intelligibility and originations are needed for that.

Second, this model is flexible enough to encompass the diversity of positions that exist on the nature of free will. The flexibility stems from the fact that each of the three components can be subjected to strong, moderate or weak interpretations.

For example, a strong version of alternativism might contend that the agent must have been able to realise different possible futures in the exact same circumstances as obtained at the moment of their original decision. A weaker version might argue that sensitivity to changes in circumstances is all that is required. In future entries we will consider the respective merits of such interpretations.

Because one can have different interpretations of the three components, one can think of this model as describing three dimensions along which different theories of free will can vary. It might be the case that weak interpretations do not deserve the label “free will”, but this is something that can be worked out after the different positions have been described.

2. Intellectual Significance

Why do people bother writing and debating the concept of free will? What’s at stake in this debate? I suggest that there are three separate issues to worry about (I think I’m taking this from something Patricia Churchland said, but I can’t be too sure):

Discussions of free will tend to blend these issues in different ways. This is understandable since how you resolve one of them will affect how you resolve the others. Nonetheless, it is worth keeping them distinct at the outset.

3. Different Positions on Free Will

After over two thousand years of sustained philosophical debate, one can imagine that numerous stances and positions have been identified on both the nature of free will and the moral and existential issues associated with it. It would be difficult to do justice to all of these positions, but thankfully most of the conversation tends to gravitate towards the following:

So there you have it, a conceptual framework for discussing free will. I will refer back to this post in future entries on this issue.

________________________________________________________________________

* “Positive” is meant here in the sense of “believes it to be true” and not “believes it to be a good or desirable thing”.

Note. This is just an introduction to the issue. Danaher explores the issue in depth here.)

This work by John Danaher is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

December 31, 2023

What is Free Will?

[image error]

by Laurence Houlgate

(Emeritus professor of philosophy at California Polytechnic State University)

John Searle vs Thomas Hobbes

Several years ago former University of California philosophy professor John Searle posted a YouTube video on the difficulty of finding a solution to the problem of free will. In the video, staged as an interview by an interlocutor, Searle begins with a description of the centuries-old stand-off between philosophers who say we have free will and those who deny this.

1. Philosophers who are pro-free will are often referred to as libertarians. Searle says that one of the libertarian arguments is based on our daily experience of free will (e.g. throwing a baseball, going to class, playing the piano). If I feel that I am free to either throw or not throw the baseball, then it must be that I am free to throw or not throw the baseball. If I feel that I am free to change my mind and not go to class today, then I am free to either attend or not attend.

Philosophers who are anti-free will are referred to as determinists. The determinist argument begins with the premise that every event has a sufficient cause. A decision or choice is an event. An event that has a sufficient cause is not free. Therefore, a decision or choice is not free. It follows that what one feels as one goes about one’s daily life is irrelevant. No matter how we feel when we throw the baseball or change our mind about going to class today, these choices have a causally sufficient explanation.

2. One popular way out of this dilemma is promoted by a theory called compatibilism. This theory says that the phrase “I threw the ball of my own free will” is compatible with “There is a causally sufficient explanation for throwing the ball.” When I say, “I threw the ball of my own free will” I mean that no one was stopping me from throwing the ball. This does not contradict the determinist claim that there is a causally sufficient explanation for my choice to throw the ball. If a neurobiologist says that she can explain why I threw the ball by examining my brain functions and the neural circuits that show how I decide or choose to behave, then this is perfectly compatible with my response that no one was stopping me from throwing the ball, that is, when I threw the ball I was doing so of my own free will.

One of the first philosophers to promote compatibility was the seventeenth century Thomas Hobbes (Leviathan 1651). Hobbes wrote that the concept “free will” simply means that there are no impediments to what I am doing (ch. 21). When the jailer says to the prisoner who has served his term, “You are now free to go” he means that there is no impediment to prevent the prisoner from walking out of the jail. The impediment is the jail cell. The cell door is open. The prisoner is free to go.

Hobbes also draws an analogy between (a) a man who “freely” gets out of a bed where he has been tied down by ropes and (b) “floodwaters are freely spilling over the riverbanks” (ibid.). Hobbes claims that if there is no objection to the use of “freely” in (b), then there should be no objection to the use of “freely” in (a). In both examples, the word “freely” does not mean that the events have no antecedent sufficient cause. The word simply means that there is no impediment preventing the man from getting out of bed or the water from spilling.

This being said, the so-called “problem of free will” evaporates. “You are free to go” is perfectly compatible with the claim that the prisoner’s choice to leave the jail is an event that has a sufficient causal explanation.

3. But Professor Searle does not agree. He says that compatibilism is a “copout.” It is a theory that “evades the problem” that every decision we make has an antecedent cause that compels the decision. If we can’t escape the chain of causation, then our actions and decisions are never free. Therefore, freedom to choose is “an illusion.” When I choose to throw the ball, decide to wash the dishes, or skip class, I am no different than a robot programmed to make the same choices.

4. Searle gets the last word. In the video he says that there is a “gap” between the chain of causation and one’s choices or decisions. The gap is not an empty space. It is “the conscious process of decision-making.” Searle’s example of this process (gap) is a situation in which you are weighing the pros and cons of two candidates for political office prior to making a decision to vote for one of them or (perhaps) not vote at all. Whatever you decide, your decision is not compelled by the process. The decision you make is entirely “up to you.” And that, Searle says, is free will.

Questions for thought and discussion:

1. Is Hobbes right about his version of compatibilism? Are there any defects in his theory that there is no conflict between libertarians and determinists about the meaning of free will? Are they both right?

2. Is Searle right about his version of libertarianism? Are there any defects in his “gap” version of libertarianism? How would a determinist respond to Searle’s gap theory?

3. Why does Searle say that compatibilism evades the problem of free will? Do you agree?

4. If determinism is right that no one can act of their own free will, then is it fair or just to punish people for wrongdoing?

5. How does a determinist spend their day? Do they just go about their business as if they had free will or should they sit down and wait for something to happen?

References:

Hobbes, Thomas. 1651. Leviathan.

Houlgate, Laurence. 2021. Understanding Thomas Hobbes (Amazon Kindle).

O’Connor, Timothy and Christopher Franklin, “Free Will”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2022 Edition)

Searle, John. 2023. Closer to Truth: What is Free Will. (YouTube with transcript).

DO YOU NEED HELP READING AND UNDERSTANDING THE CLASSICS OF WESTERN PHILOSOPHY?

Each study guide in the series you see below is written and designed for beginning and intermediate philosophy students. These guides can be reviewed and purchased at Amazon.com .

(or search on Amazon using the book title and my last name, e.g. Understanding Plato, Houlgate)

[image error]HERE IS ANOTHER BOOK THAT CAN HELP YOU UNDERSTAND, READ AND WRITE PHILOSOPHY

Understanding Philosophy, Third Edition (see book cover below) is a companion to the eight books in the Philosophy Study Guides series. It provides students with the grounding they need to read and better understand the classics of philosophy discussed in the series.

In Part I, the tools of the philosopher are described; for example, distinguishing between deductive and inductive arguments, recognizing valid argument forms, learning how logic and reasoning were used by the great philosophers, studying formal and informal fallacies, and other important distinctions between successes and pitfalls in reasoning.

Part II is about the important distinction, often ignored, between problems of philosophy and problems of science and the different methods used by each. (Hint: Have you ever seen a sign at your university that says “Philosophy Laboratory”? Or a memo that says “Philosophy field trip on Thursday. Sign up now.”?)

Part III provides students with a set of topics suitable for philosophy term papers, a seven-step approach to organizing and writing a paper, and solving a philosophical problem. Chapter 9 in Part III has a sample term paper on a problem that has recently gotten out of hand – and I mean this literally – by transforming a philosophical problem into a science problem. The problem is the age-old question about life after death, and the way it gets transformed is an excellent example of the wide difference between philosophical and scientific problems and methods.

Part IV shows how philosophical problems have been clarified and (sometimes) solved by the great philosophers using ‘reasoning’ (logic) in the analysis of key concepts. Examples of reasoning are taken from the works of Plato, Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Rene Descartes, Immanuel Kant, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and John Stuart Mill.

Part V is new. It focuses on four contemporary social issues: artificial intelligence, self-defense laws, offensive speech and behavior, and the current status of American democracy. Although most of these issues are not discussed in most classical works, I show that the methods of the great philosophers are nearly identical to the methods used by contemporary philosophers.

A word about ‘method’. I am using this term as “a way, technique, or process of or for doing something.” (MW). Applied to a philosophical problem, what I want to show beginning philosophy students are the techniques of clarifying and (hopefully) solving a philosophical problem.

I do not want to confuse the ways of doing philosophy with the philosophical debate about ways of knowing. There is an age-old debate between the schools of rationalism and empiricism. Without boring everyone with the details of this debate, I mention it here only because the debate presupposes the use of philosophical method, as described in Part I. Whether you are arguing for one school or the other you must rely on logic and reasoning.

Second, logic and reasoning are built into the definition of ‘philosophy’. Although this word also has several uses, Western philosophers would agree that philosophy is “critical reflection on the justification of basic human beliefs and analysis of basic concepts in terms of which such beliefs are expressed” (Edwards and Pap, xiv). This definition reaches at least as far back as the opening chapters of Plato’s Republic in which Socrates challenges his audience to define the concept of justice. This challenge marks the difference between philosophy and modern science.

And so, the philosopher’s parade that began 2,400 years ago continues to the present day. All you will need to join the parade is a desire to study our basic human beliefs and the concepts in which they have traditionally been expressed.

And since this is a parade of thought not legs, you won’t have to get out of your chair (or go on a field trip).

UNDERSTANDING PHILOSOPHY, 3rd edition

Now available at the Amazon.com

online bookstore

Go to Amazon.com and use the search terms ‘Houlgate’ and ‘Understanding Philosophy‘ or click on this link.

[image error]December 23, 2023

Americans turn to Stoicism in their search for meaning

[image error]Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism

by Sandra Woien, Arizona State University

(originally appeared in “The Conversation” Nov. 29, 2023)

Stoicism may be having a renaissance. For centuries, the ancient philosophy that originated in Greece and spread across the Roman Empire was more or less treated as extinct – with the word “stoic” hanging on as shorthand for someone unemotional. But today, with the help of the internet, it’s gaining ground: one of the biggest online communities, The Daily Stoic, claims to have an email following of over 750,000 subscribers.

Perhaps it’s not so surprising. The United States’ current political climate has parallels to the last few centuries B.C. in ancient Rome, home of notable Stoics like the the philosopher Epictetus, a former slave, and the emperor Marcus Aurelius. During this period of instability, including the fall of the Roman Republic, Stoicism helped its practitioners find community, meaning and tranquility.

Today, too, society faces widespread feelings of isolation, depression and anxiety. Meanwhile, more and more people are looking for answers outside of mainstream religion. According to a 2022 Gallup Poll, 21% of Americans now say they have no religious affiliation.

Riding this resurgence of interest in Stoicism, I designed a college philosophy class that covers both theory and practice. When I ask students why they enrolled, I hear not only a genuine interest in the subject but also a desire to find meaning, purpose and personal development.

Core principles

Ancient Stoicism aimed to be a complete philosophy encompassing ethics, physics and logic. Yet most modern Stoics focus primarily on ethics, and they typically adopt four Stoic principles.

The first is that virtue is the only or highest good, including the cardinal virtues of wisdom, temperance, courage and justice. Everything apart from virtue – including wealth, health and reputation – might be nice to have, but they do not directly contribute to human flourishing.

Marcus Aurelius: not just an emperor but a Stoic philosopher. Bibi Saint-Pol/Glyptothek/Wikimedia

Marcus Aurelius: not just an emperor but a Stoic philosopher. Bibi Saint-Pol/Glyptothek/WikimediaSecond, people ought to live in accordance with nature or reason. This principle reflects the Stoic belief that the universe exhibits a rational order, so we ought to align our beliefs and actions with eternal principles. Living in accordance with nature also reveals the interconnectedness of all things, showing how humans are part of a larger whole.

Third, a person can control only their own actions – not external events. Epictetus laid out this dichotomy in the opening sentence of The Enchiridion, a collection of his core teachings compiled by his student Arrian: “Things in our control are opinion, pursuit, desire, aversion, and, in a word, whatever are our own actions. Things not in our control are body, property, reputation, command, and, in one word, whatever are not our own actions.”

The fourth principle is that thoughts about external events are often the source of discontentment or distress – a view that has influenced modern cognitive behavioral therapy. Again, this idea comes directly from Epictetus: “Men are disturbed, not by things, but by the principles and notions which they form concerning things.”

Taken together, these principles form the bedrock of modern Stoicism, which aims to provide a coherent philosophy of life. Its hope is that once the practitioner accepts they are not entirely in control, they start building resilience and reducing anxiety. Not only is each individual the architect of their emotional life, but people can shape their own judgments in ways that are conducive to greater inner peace.

Stoicism in practiceIn Discourses, Epictetus unequivocally states that study is not enough – in order to become virtuous, a person must couple study with practice. “In theory, there is nothing to restrain us from drawing the consequences of what we have been taught,” he noted, “whereas in life there are many things that pull us off course.”

In other words, philosophy is not only an intellectual endeavor but a practical and spiritual one: a way of life designed to move practitioners toward the Stoic conception of the good. Learning to cultivate core Stoic principles involves certain spiritual exercises.

My class incorporates a variety of these exercises so students can get a taste of Stoicism in practice. One is the “view from above,” which encourages the practitioner to imagine their life and certain situations from a bird’s-eye view, putting the insignificance of their current troubles in perspective.

Another is “negative visualization”: contemplating the absence of something we value. Instead of worrying about losing something, a person intentionally meditates on its absence, with the intention of fostering gratitude and contentment. When doing this exercise in class, students have imagined the loss of a possession, a scholarship or even a beloved pet.

An illustration of Epictetus, likely drawn by William Sonmans and engraved by Michael Burghers, that served as frontispiece for a translation of Epictetus’ Enchiridion, printed in 1715. John Adams Library at the Boston Public Library/Aristeas/Wikimedia

An illustration of Epictetus, likely drawn by William Sonmans and engraved by Michael Burghers, that served as frontispiece for a translation of Epictetus’ Enchiridion, printed in 1715. John Adams Library at the Boston Public Library/Aristeas/WikimediaA third exercise is journaling to plan and review one’s day. Reflecting on thoughts and actions allows a more objective, rational way to judge whether someone is living in accordance with their principles.

Once the exercises are incorporated with theory, Stoicism can become a type of spiritual project. As Epictetus wrote, “For just as wood is the material of the carpenter, and bronze that of the sculptor, the art of living has each individual’s own life as its material.”

The way of the prokoptonSo what does it mean to be a practicing Stoic – a “prokopton,” in Greek?

For both ancient and modern practitioners, Stoicism is more than a set of abstract ideas. It is a set of guiding principles that permeate all aspects of one’s life. The goal is progress, not perfection – and exploring Stoic ideas alongside others is encouraged.

Today, there are at least three relatively robust Stoic communities online: The Daily Stoic, Modern Stoicism and the College of Stoic Philosophers.

By having dedicated communities, a guiding framework and distinctive spiritual exercises, parallels between Stoicism and many mainstream religions are undeniable. For modern people looking for such things, Stoicism may serve as a surrogate or complement to mainstream religion. People today tend to find the original Stoics’ notions about physics and theology implausible, but apart from those ideas, the core principles of modern Stoicism can be palatable to people who identify with contemporary faith traditions – or none.

The ancient Greeks believed that a philosophy of life is critical for human flourishing. Without a guiding ethos, they feared, individuals are likely to lead unstructured and unproductive lives, to pursue superficial pleasures and to feel that their lives lack purpose. Stoicism offered a path for some to follow – then, and now.

December 19, 2023

Blogging For Ten Years Old

An Opte Project visualization of routing paths through a portion of the Internet

An Opte Project visualization of routing paths through a portion of the Internet

I published my first post on this blog exactly ten years ago today. Since then I’ve published 1341 posts. However, I have reposted some old ones and had guest authors too so the number above exaggerates my productivity.

I’ve thoroughly enjoyed recording my thoughts, mostly in the hope that someone out there in the world finds them enjoyable and perhaps enlightening too. I’ve also been lucky to have communicated with many new people because of the blog. How many of them I wish I knew in person. But at least I’ve had the pleasure of corresponding with them.

It is easy enough to quickly wonder about the meaning of it all, the most common theme explored on the blog, as I think back on ten years of writing. But then in life, the best we can do is what’s in front of us, the things that we should do if we are fortunate enough to be able to do them—shopping for groceries, talking with friends, taking walks, caring for our children, etc. How deeply it hurts that so many don’t have the opportunity to live good human lives because of pain, poverty, loneliness, incarceration, etc.

So I’d like to thank my readers, particularly all those who send thoughtful comments. Although I don’t have time to respond to each one, I do read them all.

It’s weird to think I was 58 and still teaching when I started writing the blog and I’m now 68 and no longer in the classroom. But then time marches on. I so hope that humanity is evolving in a progressive direction and that the future will be better than the past. In the meantime, I’ll just keep jotting things down.

Bloggin For Ten Years Old

An Opte Project visualization of routing paths through a portion of the Internet

An Opte Project visualization of routing paths through a portion of the Internet

I published my first post on this blog exactly ten years ago today. Since then I’ve published 1341 posts. However, I have reposted some old ones and had guest authors too so the number above exaggerates my productivity.

I’ve thoroughly enjoyed recording my thoughts, mostly in the hope that someone out there in the world finds them enjoyable and perhaps enlightening too. I’ve also been lucky to have communicated with many new people because of the blog. How many of them I wish I knew in person. But at least I’ve had the pleasure of corresponding with them.

It is easy enough to quickly wonder about the meaning of it all, the most common theme explored on the blog, as I think back on ten years of writing. But then in life, the best we can do is what’s in front of us, the things that we should do if we are fortunate enough to be able to do them—shopping for groceries, talking with friends, taking walks, caring for our children, etc. How deeply it hurts that so many don’t have the opportunity to live good human lives because of pain, poverty, loneliness, incarceration, etc.

So I’d like to thank my readers, particularly all those who send thoughtful comments. Although I don’t have time to respond to each one, I do read them all.

It’s weird to think I was 58 and still teaching when I started writing the blog and I’m now 68 and no longer in the classroom. But then time marches on. I so hope that humanity is evolving in a progressive direction and that the future will be better than the past. In the meantime, I’ll just keep jotting things done.

December 17, 2023

Dropping An Atomic Bomb

[image error]by Chris Crawford

First, I have a good friend who is a hibakusha (survivor of an atomic bombing). She was ten years old and reading a book a little more than a mile from ground zero when the bomb exploded at Hiroshima. She was only slightly injured, but she very nearly died of radiation exposure. I helped her rewrite her memoirs, and we spent many hours discussing the events.

My own assessment is complicated. The Japanese were willing to surrender months earlier if only the Allies promised to respect the Emperor. But Roosevelt had agreed to the “unconditional surrender” specification and Truman refused to renege on that promise. Hiroshima and Nagasaki were therefore unnecessary and immoral.

HOWEVER, all too often we fail to take account of what the actors in historical events did and did not know when they made their decisions. It’s the fog of war. Truman’s knowledge of Japanese intentions was based on its public pronouncements, primarily its propaganda, which was ferociously defiant. Truman did not know that a careful diplomatic strategy would probably have yielded peace without the need for either an invasion or the use of the Bomb. Therefore, I conclude that, while he made what was, in the final analysis, the wrong decision, I think that his decision is excusable because he lacked the information necessary to reach the best conclusion.

Another point: there is only one way to conclude a war successfully, and that is to convince the enemy that he is defeated. The facts on the ground aren’t as important as the enemy’s perception of those facts. The worst way to fight a war is to impose a steady flow of casualties on the enemy. That can go on forever. You need something dramatic, something that stuns and demoralizes the enemy.

Israel’s strategy with respect to the Palestinians is just about the worst possible. They are imposing a steady stream of casualties on the Palestinians without ever doing anything to change Palestinian minds. They have been for years killing roughly ten Palestinians for every Israeli killed. (Side note: most of the Palestinian casualties come not from bombs and bullets but from all the constraints on normal civilian life imposed by the Israeli occupation. Roadblocks delay emergency trips to the hospital with deadly consequences. Inadequate sewage systems and irregular electricity supplies encourage the spread of disease. Unemployed youth commit suicide by cop)

Thus, Israel has been stoking the hatred of the Palestinians for decades. The Israeli government believes that it can eventually intimidate the Palestinians into a sullen acceptance of their fate at Israeli hands. It doesn’t work that way. Hitler’s Blitz on Britain didn’t intimidate the British. The Allied bombings of Germany killed huge numbers of Germans but never broke their morale. The American bombings in Vietnam were equally ineffective. Every hunter knows that the worst thing you can do is wound an animal without incapacitating it, but few governments, especially the Israeli government understand that principle. In the case of hunting animals, you must kill a wounded animal — but genocide of millions of Palestinians is not an option.

The only moral solution to the conflict is a peace based on the creation of a viable Palestinian state. Israel refuses to recognize this truth, and so the killing will go on forever, with one possible exception. At some point, the Palestinians will obtain a weapon of mass destruction: a nuclear weapon or a biological weapon. They will use this weapon and cause so much destruction that they will shock the Israelis into making a choice between outright genocide and making peace.