Scott Timberg's Blog, page 19

January 5, 2015

Postmodernism and the Human Condition

ONE of our favorite controversies over the last few moths has been the tussle over Excellent Sheep, the William Deresiewicz book that criticizes the obsessive pragmatism and money worship that’s come to define the Ivy League experience. Simultaneously, one of our least favorite recent developments has been the destruction of the magazine The New Republic by a callow Silicon Valley rich boy and his tech-utopian sidekick.

I would not have thought of connecting these two issues, but they seem to have a natural affinity: In a Salon interview, Deresiewicz reminds me why I’ve come to read his work so avidly. “We’ve basically reduced what it means to be human to market terms, to getting and spending,” he says. One of his culprits is postmodernism, which he associates not with Thomas Pynchon or the films of Godard but “the time of neoliberalism or Reaganomics or market fundamentalism, where the only thing that matters about you is your function in the marketplace.”

We’ve always been a society where the market has been the dominant cultural and political factor but, historically, most of the time there have been counterbalancing institutions— and we can broadly call those institutions “culture.” That’s meant the churches and the universities and art and thought and journalism.

What we have today is, first of all, a time when the balance is really getting out of whack. The market has come to predominate in a way that it hasn’t in a long time. The other thing is that those very institutions of culture whose job it is to fight for and speak for other values like learning for its own sake, or beauty or justice or truth, they are being captured by the market. They have been bought by the market and been turned to serve the ends of the market. That’s true in higher education and it’s true in journalism. It’s also true in the churches, if you think about, for instance, the prosperity gospel.

What [New Republic owner] Chris Hughes doesn’t understand is that The New Republic has never made money. The Nation loses money now, Harper’s loses money now, and they’ve been reliant on benevolent plutocrats who recognize that there are more important things than the market and are willing to run them not as profit-making institutions but as institutions that have value for other reasons.

The whole interview is worth reading, especially when he calls Hughes an “entitled little shit.”

January 4, 2015

The Dark Vision of Neil Postman

ONE of my all-time favorite social critics is the late, great author of Amusing Ourselves To Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. (I’m even fonder of his book Technopoly, which came out in the early ’90s but remains one of the great books about what the Internet would do to us.)

So my senses were stirred when I began to see writers on various sides of the spectrum — Matt Bai on politics, Jaron Lanier on technology and economics, Sherry Turkle and digital gadgets and our souls — drawing from his vision.

The result is my new piece on Salon, here. I begin it this way:

The result is my new piece on Salon, here. I begin it this way:

These days, even the kind of educated person who might have once disdained TV and scorned electronic gadgets debates plot turns from “Game of Thrones” and carries an app-laden iPhone. The few left concerned about the effects of the Internet are dismissed as Luddites or killjoys who are on the wrong side of history. A new kind of consensus has shaped up as Steve Jobs becomes the new John Lennon, Amanda Palmer the new Liz Phair, and Elon Musk’s rebel cool graces magazines covers. Conservatives praise Silicon Valley for its entrepreneurial energy; a Democratic president steers millions of dollars of funding to Amazon.

It seems like a funny era for the work of a cautionary social critic, one often dubious about the wonders of technology – including television — whose most famous book came out three decades ago.

Like anyone who wrote in decades past, some of his work has dated. But much of it is more relevant than ever.

December 30, 2014

Brooklyn’s Warehouse Clubs Crumble

TECHNO-utopians, heartless neoliberals and market-worshipping optimists will tell you that when creative destruction hits, it’s only weeding out the losers, casting off the dead wood, allowing the invisible hand — which works in mysterious ways — to do its work. And it’s easy to imagine, say, an acoustic folk club or a jazz cellar not being able to make it in a big, expensive city like New York.

But what we’re seeing now is some of the coolest spots — indie rock and electronica clubs — on the edgy edge of Brooklyn collapse under the pressure of the the city’s plutocrat-driven real estate market. Here’s John Caramanica in a NY Times piece:

Every few months, it seems, one of the spaces that transformed Williamsburg from warehouse-heavy cultural dead zone to warehouse-heavy primordial soup for the city’s creative life finally surrenders to the neighborhood’s ongoing condo-fication, literal and metaphorical. At the beginning of the year, it was 285 Kent, which not that long ago was followed into the ether by Death by Audio. Now it’s Glasslands’s turn.

As even the most far-flung and bohemian spots in New York get gentrified and corporate-tized to within an inch of their lives, we’ll be seeing a lot more of this. (Goodbye, Glasslands , and fare well on the other side.)

, and fare well on the other side.)

Another piece from the New York Times notes: “It’s a familiar New York story, but sped up, with waves of gentrification and still-rising real estate prices disrupting the music scenes that blossomed in earlier, increasingly short-lived iterations of the neighborhood.”

Disappointing to see the city turn into a shopping mall. In a time when even Hoboken — once the home of what may be my favorite rock club, Maxwell’s — has been conquered by junior bankers, perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised.

December 26, 2014

Science, Religion and the Arts

ARE there subjects science, metrics, Big Data, and rational thought can’t entirely address? I sometimes thinks that these issues are the ones arts and culture are about, but I’m coming to realize that there’s another lineage that engages with them as well: Religion.

To many, this will sound obvious, but the relationship between religion and culture is hardly simple. (It’s also one that as as lifetime agnostic, I wish I had a firmer and more complete sense of.)

In any case, I was brought to brood on some of these unfathomables by a new interview with the religion scholar and writer Jack Miles, the editor of the new Norton Anthology of World Religions. The piece (by my wife, Sara Scribner), includes this line:

There are questions that remain in the human mind even when science doesn’t address them.

This may be the best description I’ve heard lately about the role of the arts and culture. It’s certainly one that sticks with me as I celebrate an agnostic’s Christmas.

This site will be up and running more fully in a few days. Wishing everyone a happy holiday season and new year.

December 19, 2014

Has Architecture Lost Its Connection?

ARCHITECTURE is a funny field: Much of its most important, most talked-about work is done for a tiny number of clients — we’ll call them rich people — but the profession has a lingering (and in some cases sincere) social conscience and concern for the broader built environment the rest of us live in.

That blend of ambitions has come unstuck, an architect and a journalist argued the other day in this New York Times story. Here are Steven Bingler and Martin C. Pedersen:

For too long, our profession has flatly dismissed the general public’s take on our work, even as we talk about making that work more relevant with worthy ideas like sustainability, smart growth and “resilience planning.”

Frank Lloyd Wright

… The question is, at what point does architecture’s potential to improve human life become lost because of its inability to connect with actual humans?

… We’re brilliant at devising sublime (or bombastic) structures for a global elite who share our values. We seem increasingly incapable, however, of creating artful, harmonious work that resonates with a broad swath of the general population, the very people we are, at least theoretically, meant to serve.

… Architecture’s disconnect is both physical and spiritual. We’re attempting to sell the public buildings and neighborhoods they don’t particularly want, in a language they don’t understand. In the meantime, we’ve ceded the rest of the built environment to hacks, with sprawl and dreck rolling out all around us.

I have little disagreement with the authors, and their descriptions of working in post-storm New Orleans are quite persuasive. But I’ll suggest the problem is not simply with the culture of high-end architecture, but also a larger “culture of culture” — that is, in a pragmatic Anglo-American world that increasingly thinks that the fine arts and design are for the rich, and where there is very little education in architecture and urbanism for non-practitioners. If architects and the general public are estranged, both could benefit from moving towards each other a bit.

The piece is not long, but it’s fairly complex. I urge my readers to check it out in full. And I’ll look forward to the authors’ upcoming book, Building on the Common Edge.

Nature Painting and Weimar Film at LACMA

SOME days all the planets line up and a visit to a museum really can offer “fun for the whole family.” That’s what happened at the LACMA a few days ago, where the ups and downs of exhibit schedules meant a show of samurai armor, another of Hudson River school 19th c. painting, and another of German Expressionist Cinema.

I spent most of my time in the latter two (my son loved the Japanese stuff, most of which comes from the 14th to 19th centuries.)

The so-called Hudson River painters were among the first artists to come up with a distinctly American way of rendering the continent’s landscape. In some ways they are parallel to the literary generation of Emerson and Thoreau, though some of their influences were British — such as Turner — and Thomas Cole, the most seminal of the bunch, was born in England. The influence of English poetic romanticism is also strong on their work, but they are working to capture what’s distinctive about our rivers and mountains and forests, as well as our light.

The LACMA show — Nature and the American Vision: The Hudson River School — is small to medium in size, but it’s full of wonders, including Cole’s important The Course of Empire paintings.

The exhibit concentrates on Cole, Durant, Bierstadt in the Hudson River Valley and elsewhere; one of the most intriguing sections looked at painters bringing their style and sensibility to Italy, a land they saw as old and perhaps as haunted as America was new and open. While it’s hardly definitive, it’s a powerful show I will return to contemplate again.

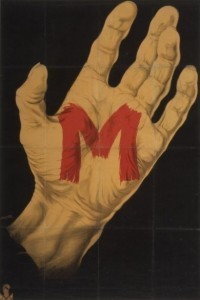

Haunted Screens: German Cinema in the 1920s, is even more breathtaking. The show concentrates on the dark, shadowy Expressionist films that would become crucial inspirations for American noir cinema. Some of the movies, like Murnau’s Sunrise, reflect the humanism of Weimar. Others draw from German romanticism and folklore. Still others (Fritz Lang’s chilling M.) foreshadow or engage in symbolic terms the rise of fascism.

The show includes original artwork, some of it anonymous, for set designs, striking, sharp-angled posters, and scenes from a handful of films. Even the roughest sketches show the German Expressionist genius.

The show includes original artwork, some of it anonymous, for set designs, striking, sharp-angled posters, and scenes from a handful of films. Even the roughest sketches show the German Expressionist genius.

Michael Maltzan, one of L.A.’s greatest and most imaginative architects, worked on the exhibition design. Between Gehry’s design for the Calder exhibit, LACMA is making very good use of Southland architects.

I spent a lot of time in this show, but am even more eager than I am with the Hudson River School exhibit to view it again. Don’t miss it.

December 18, 2014

Novelist Janet Fitch Joins Culture Crash at Skylight Books

IT’s been both gratifying and frustrating to have my book launch at the LA Central Library fill up so quickly. (Tickets went in a single day.) Now Los Angeles audiences have another chance to see me discuss the subjects I dig into on this blog and in my upcoming book — at Skylight Books.

And I’m glad to say that Janet Fitch, the LA novelist (White Oleander, Paint it Black) — a fellow advocate of independent bookstores who is congruent with my thinking on many matters — will join me for a conversation on Sunday March 15. Skylight, of course, is one of LA’s best bookstores, and I’ve seen a lot of great author readings and discussions there over the years. One of the store’s longtime employees is mentioned in my chapter on bookstore clerks; I won’t menti on his name here because it embarrasses him. But they’ve got a wonderful staff.

on his name here because it embarrasses him. But they’ve got a wonderful staff.

Our Department of Self Promotion would also like to point out that the Central Library’s ALOUD series — the event there is January 13 — always leaves some tickets for walk-ins, so you may still be able to get in.

I’ll be posting a complete lists on the events on this site soon.

December 16, 2014

The Middle Class Gets Crushed

ONE of my guiding principles on this site and in the soon-to-be-published book it accompanies is that the creative class it almost entirely embedded within the middle class, and that musicians, writers, artists, etc. are even more exposed to contemporary economic pressures than the average burgher. This is despite the fact that the artists we tend to hear about are typically gazillionaire superstars; the counter-myth, of course, is that artists are gutter-dwelling absinthe sniffers.

So I’m especially gratified to see what’s starting out as a sharp, vividly written and illustrated  series on the Washington Post about “Why America’s Middle Class is Lost.”

series on the Washington Post about “Why America’s Middle Class is Lost.”

Yes, the stock market is soaring, the unemployment rate is finally retreating after the Great Recession and the economy added 321,000 jobs last month. But all that growth has done nothing to boost pay for the typical American worker. Average wages haven’t risen over the last year, after adjusting for inflation. Real household median income is still lower than it was when the recession ended.

Make no mistake: The American middle class is in trouble.

That trouble started decades ago, well before the 2008 financial crisis, and it is rooted in shifts far more complicated than the simple tax-and-spend debates that dominate economic policymaking in Washington.

It used to be that when the U.S. economy grew, workers up and down the economic ladder saw their incomes increase, too. But over the past 25 years, the economy has grown 83 percent, after adjusting for inflation — and the typical family’s income hasn’t budged. In that time, corporate profits doubled as a share of the economy. Workers today produce nearly twice as many goods and services per hour on the job as they did in 1989, but as a group, they get less of the nation’s economic pie. In 81 percent of America’s counties, the median income is lower today than it was 15 years ago.

Why are median wages flat or declining? Why are jobs, in many places — like onetime aerospace hub Downey, CA, where the series opens — not coming back, or only returning with lower pay? What has caused the rise of inequality and why does neither political party seem capable of fixing it? The opening article has valuable personal stories as well as lots of maps and data.

The opening story is called “Liftoff & Letdown,” in reference to Downey’s role in the Apollo moon launch.

(It’s probably not useful for me to point out that those of us on the left — or dwelling in the middle class — have been well aware of the demise of the middle class for years now.)

I’ll try to post on the next two parts of the series, as well.

December 15, 2014

Nicholas Carr’s “The Shallows”

ONE of the best books on life in the digital age — and perhaps the one closest to my own point of view — is Nicholas Carr’s The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains. I like it for a host of reasons, among them Carr’s elegant style, cool tone, and literary and humanistic sensibility. Among my favorite passages:

When I summon up images from my early years, they seem at once comforting and alien, like stills from a G-rated David Lynch film. There’s the bulky mustard-yellow telephone affixed to the wall of our kitchen, with its rotary dial and long, coiled cord. There’s my dad fiddling with the rabbit ears on top of the TV, vainly trying to get rid of the snow obscuring the Reds game. There’s the rolled-up, dew-dampened morning newspaper lying in our gravel driveway. There’s the hi-fi console in the living room, a few record jackets and dust sleeves (some from my older siblings’ Beatles albums) scattered on the carpet around it. And downstairs, in the musty basement family room, there are the books on the bookshelves – lots of books – with their many-colored spines, each bearing a title and the name of a writer.

This is one of many epigraphs I originally included in Culture Crash the book, but which ended up on the cutting room floor. (I could publish an entire, shortish book made up of quotes that almost went into Culture Crash.)

I’ve just started to read Carr’s new book, The Glass Cage: Automation and Us . An important writer and thinker, and someone who sees through a lot of the hype.

. An important writer and thinker, and someone who sees through a lot of the hype.

December 12, 2014

Culture Crash the Book Goes to Washington

THE august D.C. bookstore Politics and Prose will host an event for my book a few days after publication, on Saturday evening, January 17.

This is a great bookstore with a smart staff and a great hand-picked selection; it’s exactly the kind of place I write about in the book, and the kind of place that tends to disappear in the digital age unless there is very committed management, a loyal readership, and a lot of luck. An honor to appear there.

President Obama recently visited the shop. A former employee once told me a story of Clinton coming in and buying a lot of noir novels.

A FEW days ago I annou nced a New York date (January 21 at McNally Jackson.) There’s at least one more, maybe two more, events coming — I’ll try to post the whole slate on my site soon.

nced a New York date (January 21 at McNally Jackson.) There’s at least one more, maybe two more, events coming — I’ll try to post the whole slate on my site soon.

Scott Timberg's Blog

- Scott Timberg's profile

- 7 followers