David Boyle's Blog, page 5

April 27, 2021

Towards a different kind of leader

There is no doubt that – rightly or wrongly – we are feeling let down by our leaders these days, whether it is for their vacillation or greed or, listening to Keir Starmer, maybe for their steadfast failure to talk about what’s most important.

Personally, I think the emails between Boris Johnson and James Dyson are neither here nor there. And the NHS blogger Roy Lilley feels the same way: see his latest blog post about accessible leadership to see why.

Neither, actually, is what was or wasn’t said in the heat of the moment in No. 10 – especially as we have not in fact had bodies “piled in the street”.

Allegations about who paid for Johnson’s refurbishment in Downing Street are much more important. So of course is David Cameron’s insanely close relationship with the banker Greensill.

Then there is the other kind of flawed leadership, displayed by Post Office chief executive Paula Vennells, pursuing 700 sub-postmasters through the courts because their hopeless IT system said they were stealing money, some as far as prison or bankruptcy. Some of them have finally been exonerated after more than two decades.

The system began to go a little haywire a good 12 years before she took up the post, yet she carried on with a kind of cruel intransigence.

Why are our leaders so infected either with greed or tickbox? Why do they regard their job as a combination of deference to those above them and contempt for those below? Is that a peculiarly British combination?

Contrast that for a moment with Sarah’s experience on Sunday, getting her jab at the Brighton Centre, which was packed with humane, calm and generous volunteers giving up their weekend to help out after a hard week at various coalfaces.

She came back from her needle encounter bubbling over with enthusiasm for the volunteers – and asking why David Cameron had been taking his banker friend to see the Saudi crown prince, who appears to have been behind the killing and dismemberment of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi, when ordinary people were giving up their time to help out.

It is good question. It is almost as if our current crop of leaders render themselves useless for ordinary life after office, because power corrodes their humanity in some way.

So there is one element of radical centrist leadership. Somehow we have to roll back the myopic reliance by our leaders on single tickboxed indicators – whether that is money or what their the internal IT systems are telling them (my Tickbox book also explains how those who run the world, divorced from the frontline, are often the only ones who believe what their tickbox systems are telling them).

But there is a problem or the left here too, because the left also doesn’t believe that ordinary people can manage things brilliantly and humanely – and do so every day.

The predominant narrative on the left suggests that ordinary people are the source of sexism and racism – and must therefore be controlled by professionals and other tickbox systems – to make sure that only approved buzzwords are used.

That leaves the radical centre as the only section of politics where we can talk about the heroic ordinary, bringing up children every day, with great skill – before they get spied on at work or gaoled because the IT system of their employers claims they have got their fingers in the till.

http://bit.ly/RemainsoftheWay ...

March 30, 2021

The last of the bearded sandals

This post first appeared on the Radix blog.

This post first appeared on the Radix blog.When I first joined the Liberal Party (1979), and particularly when I started going to their assemblies (1982), the television cameras used to linger on those of us sporting beards or sandals.

There was one large fellow in both who used to sit at the front. I never discovered who he was.

It is hard to be precise about what sandals and beards used to mean in politics. I wrote about this in the Guardian after the first modern sandals went on display – and the peculiar way that genuine radicals seemed to flow towards this particular garb.

I mentioned that I occasionally wear socks as well and have never really been allowed to forget it.

Politically, beards and sandals became a symbol of the deep divide on the left, between Labour and Liberals, socialist and radical. For some reason, the look was never really foisted on the Greens – they tend to be portrayed more as kind of manic druids (“Go back to your constituencies and prepare for government,” said a Green cartoon in Private Eye after their spectacular Euro-election result in 1989, showing them gathered around Stonehenge, blowing trumpets).

No, beards and sandals were a Liberal radical uniform. Yet their Lib Dem successors seem to have dodged them in favour of suits and dangly ear-rings. After the very sad death of Tony Greaves last week, I’m hard pressed to think of a single be-sandalled Lib Dem.

Greaves was an inspiration when I joined the party, from his position running the sandalled Association of Liberal Councillors in bearded Hebden Bridge. Or with his weekly column in Liberal News. By the time I became editor in 1992, it was Lib Dem News and he was only writing the back page column once a month – but he could still pinpoint a confusing issue and show, clearly and inspiringly, the Liberal angle.

He wrote a piece in 1997 for the Liberal History Group on ‘Why I am a Lib Dem’, rather like Keynes’ essay ‘Why I am a Liberal’. The upshot was that, actually, he wasn’t – he didn’t know what it meant – but that he was a Liberal. It is a view I have come round to myself as, in practice, the liberal and social democrat ideologies seem to me to be getting further apart.

Greaves was also the personified engine room of community politics, urging Liberals to think like newspaper editors to get elected. Not too much though – “would you vote for your local paper editor?” he said.

Community politics has not really survived. Politicians of all parties badly need to understand the newer concept of ‘co-production’ (my colleagues Edgar Cahn and Chris Gray have published a pamphlet on co-production and social isolation) – but more on that another day.

Tony embodied the beards and sandals approach – what academics describe as the ‘distributist wing’ of the Lib Dems.

This is an obscure way of explaining a now sadly obscure wing of the party. I also realise that, as one of the few people in the UK to write about this largely forgotten element of Liberal theology, I may now be the only expert left. But by coincidence, I just wrote about these issues in the blog of the Social Liberal Forum – and I came to a similar conclusion there:

There are now political academics who use the term ‘distributist’, shorn of its Catholic accretions, as a shorthand for the bearded sandals wing of the party. As one of that persuasion myself, I feel myself increasingly alone and misunderstood by either technocratic wing – neither right nor left seem to understand why I might be against big business but in favour of small, why I might be in favour of entrepreneurs but against corporates.

So I am sorry for the passing of the beards and sandals tradition from the Lib Dems – and even more sorry for the passing of Tony Greaves, the best of them.

Get a free copy of my medieval Brexit thriller on pdf when you sign up for the newsletter of The Real Press

March 4, 2021

'No algorithms' and the tickbox robots

This post first appeared on the Radix blog.

I had my covid jab on Friday and it turned out to be the Pfizer version. Which meant, apparently, that that we all had to sit in the surgery for 15 minutes in case we collapsed immediately afterwards.

I had no idea that this had happened to anybody. So let me take this opportunity to repeat that I don’t think it helps the pro-vaxx cause to treat anyone who discusses side-effects like some kind of Trump supporter.

There is no doubt that, for a few individuals, vaccinations can be a bit of a lottery. But I had already decided that I should take a risk, if necessary – on the grounds that I, at least, need to show a little courage if we are ever going to get our world back again.

As they say, every little helps…

But I learned from the experience, thanks to the older man who managed the car park, the ancient doctor who looked like a retired car mechanic who administered the jab, and the huge numbers of smiling local volunteers who accompanied me through the whole process.

This seems to me to be the key; local volunteers can make things happen effectively and efficiently. compare that to the algorithm-laden robots in the government-procured private sector test and trace.

That is the most important lesson for me from the last few weeks.

I mention algorithms advisedly because, last week we had what I believe is the most important official admission so far of their potential for inhuman mischief, by the education secretary Gavin Williamson.

In fact he promised this year's teacher-assessed GCSE and A level exams would involve “no algorithms whatsoever”.

I take this is the first recognition that I was correct last year in my book Tickbox about where automated systems might belong, and where they definitely don’t.

The decision must have balanced the number of appeals against a flawed algorithm against how many against a marginally less flawed human teachers. In fact, this is a big opportunity for teachers it seems to me – to demonstrate the superiority of human decision-making about other uncategorisable humans.

Get a free copy of my medieval Brexit thriller on pdf when you sign up for the newsletter of The Real Press.

February 21, 2021

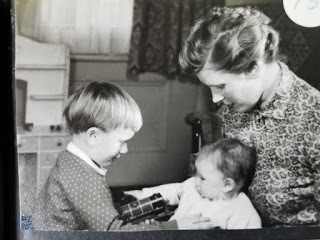

Farewell to a great generation

My mother died over last weekend. I say that partly to explain that, this time at least, my failure to meet deadlines has a reason. And partly to say something about the passing of an amazing generation.

In fact, as I understand it, the life expectancy of people born in 1931 took its biggest leap in history compared to those born in the previous year. My mum nearly made it to 90, so that very individual experience bears out the statistics.

Something about those born around the political crisis that led to a national government under Ramsay MacDonald seems to have meant that they were built pretty tough.

They were uncomplaining - rather than stiff-upper-lipped - weren’t they, the last generation to remember the Blitz and the doodlebugs? They survived rationing, deep winters in 1947 and 1963 without central heating, plus the new world of divorces, re-marriages, relationships-without-rules. Plus disastrous property slumps in 1975 and 1988.

And they did so with good humour and without complaint or moaning on as people tend to these days - just as they are currently doing with covid.

The following generation, the boomers, were those of us who came to take the extraordinary house price boom for granted - unfortunately so much so that most of our children won’t be able to afford to live near where they grew up.

Of course, I am partly remembering a very special person indeed, but there is a policy lesson here for anyone who - as I do - believe there was anything vital about the middle class life at its best.

It is this: our ruinously high house prices can never provide us with all we rely on them for - to fill the hole in our pensions, to pay for our social care and to set our children on the property ladder.

No, we have to ratchet our house prices back down before they ruin us all. And if that seems tough - my mum’s generation would have managed.

More about this in my book Broke.

This was the generation that took us into Europe, and brought us - in quick succession - all those previously foreign additions to UK life, from muesli, yoghurt, pasta to duvets (along with avocado pears, circa 1971-2).

During my wedding speech in 2003, I called her "one of the wooden walls of England", a reference to Nelson's warships. I don't think she liked the description much in retrospect, but I meant someone who buttresses people's lives - just as her generation has done throughout.

I'm sure nobody will complain about what I have written here, because I'm remembering someone special to me. But equally I'm aware that there will be some people who regard any positive mention of Englishness as somehow retrograde.

All I can say is that I'm not one of them...

Get a free copy of my medieval Brexit thriller on pdf when you sign up for the newsletter of The Real Press.

January 14, 2021

Why it is nearly time for a national government

Keir Starmer may just be a small phenomenon. I suppose that second guessing the current UK government is not actually terribly onerous. Starmer just has to stay a couple of days ahead of the government, as it twists and turns through the covid crisis, so perhaps it isn’t very hard to appear perspicatious.

But it does mean a difficulty for Boris Johnson and his government. It looks almost as if it is Starmer who is taking all the decisions.

Every time, the government does another U-turn, whether it is about locking down or closing schools, there is the opposition leader demanding it days before. Always rather magnanimously. Irritatingly so, in fact.

There will come a point when this becomes intolerable to the Conservatives. After all, why should not Starmer share some of the odium for the decisions he is apparently making?

Perhaps it doesn’t matter, they will tell themselves, if we are really in the dying days of the crisis because of the looming vaccine. But one of the lessons of covid is that there will be alarums and twists still to come.

The government is discussing the idea of tightening controls even more, after all.

In previous crises in 1915, 1931 and 1940, UK prime ministers have voluntarily shared power in these circumstances – whenever, in fact, they are forced to take such tough decisions about people’s lives that they need to share the blame.

So what I want to suggest – and I feel sure this is a scenario they have quietly discussed in corners of 10 Downing Street – is that, if anything gets unexpectedly worse again, the government should organise power-sharing and involving all parties.

The idea of locking us all in, enforced by the police, is so unBritish that governments simply can’t enforce changes like that by themselves. That means it maybe time for a national government.

Get a free copy of my medieval Brexit thriller on pdf when you sign up for the newsletter of The Real Press

January 12, 2021

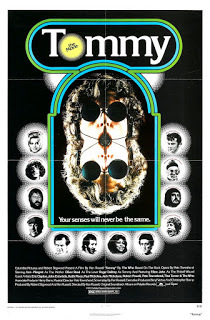

'I've a feeling '21 is going to be a good year...'

Not me, but the Who’s musical Tommy from 1969 – lyrics that are beyond the horizon of memory for most of us.

But equally, 2021 ought to be a pretty good year. Eventually. There should be a mini boom which perhaps may not be such a good experience for anyone buying a home…

Over Christmas, I have been thinking a little more about this elusive optimism. And it seems to me that we also have a couple of issues which may prevent this optimism coming to fruition.

The first of these is the widespread cynicism, that my colleague Joe Zammit-Lucia wrote about here before Christmas. Thinking back before Tommy, I’m not sure we have ever been quite as cynical as a society – especially on the Left (spent about five minutes looking at the comments below the line at the Guardian if you don’t believe me).

Did we feel so cynical about Willie Whitelaw or Ted Heath, though we might have disagreed with them passionately?

I don’t know and I would genuinely like to find out. Of course the cynics might say that there was nobody in office quite like Boris Johnson or Gavin Williamson.

That maybe so, but the all-pervading atmosphere of spin seems to have led directly to its cynical opposite.

It is true that we are entering a national lockdown, or its equivalent, for the third time, when the reasons we had to go into the first one have yet to tackled – the repeated failure of test and trace.

But we also have to remember what is really important now that we have, standing against us, the rise of a technocracy so total and unyielding, from China and elsewhere – and tickboxed at home too – that we have to fight it every moment if we want to win the emerging war for the right to our own souls.

So maybe need, at the start of 2021, to understand the plight of people like Loujain al-Hathloul (jailed in Saudi Arabia for campaigning on women’s issues) or Zhang Zhan (jailed in China for telling the truth about Wuhan last year) – and to realise that some of our online rage and sniping, that so dominates UK public discourse, might be missing the point.

In other words: we can make ‘21 a ‘good year’, but only if we shift our attention to what is most important – to realise why it is under threat and to act accordingly. Even if some of the symptoms of the tickbox disease are under our very noses.

Get a free copy of my medieval Brexit thriller on pdf when you sign up for the newsletter of The Real Press

December 17, 2020

They should have listened - they still could now...

“We created 400 clone towns nobody loves. We shouldn’t get upset – job losses aside – about changing them.”

So said Mark Robinson, co-founder of landlords Ellandi and chair of the government’s High Streets Task Force, on the BBC.

If we were more self-obsessed and rather less busy, we might reply, something like ‘we told you so’. Because one of the origins of New Weather, was in the highly prominent and successful Clone Towns campaign of 2003-8, where the organisation’s founders first met.

We even remember the moment that Andrew Simms came up with the ‘Clone Towns’ phrase to describe the bland, homogenising effects of chain stores on the places where we live. You know you are having an impact when people start using your language.

So if you believe the BBC report, the establishment has now swung behind one of our solutions for change – led perhaps by the government or local authorities buying up the empty properties.

Yet despite the success of the campaign, and all the verbal refuse thrown at us by regulators and retail experts alike, we underestimated how dead the squeezed middle of retailing had become, and how short the period of clones stores was going to be. From Top Shop to BHS, the clones have gone belly up, followed soon by the shopping centres we warned against back then.

There is a longing for the High Street, even for the unlovely shopping centres which have now fallen foul of the market. And that longing turns out not to be nostalgic or sentimental – but a longing for place and community. We meet, we saunter, we chat, we observe, we may buy – but mainly what we are doing is being sociable.

Places that went in the direction we urged back then have generally managed to weather the storm better, so far – those distinctive places that realised that high streets were opportunities for bustle, colour, market stalls, trainee entrepreneurs and untidiness, as envisaged by the American author and activist Jane Jacobs two generations ago in a pre-covid age in her landmark The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

That was the basis for the agglomeration economics so beloved but misunderstood by upholders of the status quo, like the Centre for Cities.

Places that did not listen are still cloned, but in a dull, boarded up kind of way. The truth is that the High Street has been captured by the venture capitalists and their impatience with long term profit or low profit. Chains that might have responded to love and care have been burdened with debt and then thrown to the wolves. Debenhams is a case in point. Café Rouge is another.

There is hope for the High Street. It will come after a serious and unprecedented reform of the whole rental economy, a root and branch improvement in local authority finances, so that they can have a business rate that is responsive to social and local economic good (your friendly local bakery or hairdresser) and doesn’t have to turn the screws to have the funds to look after children at risk. It will come, in short, when we recognise that some things are beyond price.

We also have to do something about pensions – many of the pensions of the right thinking are invested in the blood sucking commercial property market. We need to see how we have all become part of the issue that is undermining our only defence against monopoly power – our meagre pensions.

It is true that there are little points of hope in the High Street. The covid-induced recession we face will be survived by retailers with low overheads who know and understand their customers – the only ones capable of standing up against the powerful online oligopolies, like vacuum cleaners sucking up the available spending and removing it from circulation.

But these small retailers in high streets are going to struggle under the cosh of high rates – based on our UK obsession with property as the only safe haven for investment. It may be a time again, as Keynes put it, for the ‘euthanasia of the rentiers’.

Then the High Street will again become the living centre of the towns and cities we inhabit – open to social and commercial developments that respond to our needs and wishes. Places that are particular to who we are, and where others want to come. But we need to reimagine them as places for more than passive consumerism.

Empty spaces can provide spaces for the community, mutual aid groups that flowered during lockdown, they can provide bases for micro entrepeneurs, share sheds, tool libraries, book exchanges, local producers and culture, and for advice centres and hubs to help deliver the low carbon transition.

With great ambition but little infrastructure to back it up, for example, the massive energy retro-fit challenge for our homes would be hugely helped by having one-stop shop local advice centres that also helped to bring providers together.

Using our imagination, introducing more diversity, responding to challenges and taking opportunities – these are the ways we can bring high streets back to life.

Get a free copy of my medieval Brexit thriller on pdf when you sign up for the newsletter of The Real Press

November 20, 2020

Bye-bye, mein lieber Kier (and G4S, Serco and the others)

Outsourcing and privatisation died at 1518 on Wednesday 4 November 2020. Or thereabouts.

That was of course a misquotation of the great architectural critic Charles Jencks. It was also when the Guardian published the news that Randox, the company involved in a testing failure during the summer had just been handed another government contract worth £347m. Though it could perfectly well refer to the bankruptcy of Carillion on 15 January 2018.

It is strange when you think about it, but the more they have held on to life, the more that privatised utilities and outsourcers have become a byword for incompetence – rather as, once upon a time, it used to be with nationalised industries.

Ironically, this is both for similar reasons – both were far too big to be responsive.

In my new pamphlet for the New Weather thinktank, The End of Privatisation, I tell the strange story of privatisation, from its beginnings with Peter Drucker and Keith Joseph in the 1970s and the triumphant sell-off of British Telecom in 1984 – and the ideas at the heart of it: more entrepreneurial efficiency, less cost.

Nearly four decades have passed since then and those promises have turned to dust, and for similar reasons: most of the outsourcers are too big to operate effectively.

As Drucker wrote himself: “The most entrepreneurial, innovative people behave like the worst time-serving bureaucrat or power-hungry politician six months after they have taken over the management of a public service institution." And so it proved.

Even the outsourcers add another layer of costs during an unaffordable austerity years and their only expertise turns out to be provide the KPI and target data that ministers crave, and which only they believe.

They represent rule by tickbox – which, as we know – tends to spray costs elsewhere in the system by narrowing the definitions of success to what they can easily achieve.

That explains why this final hurrah of outsourcing to government friends during covid has put the final nail in the coffin of what was once a big idea.

So why does the body of privatised outsourcing still twitch? There is no practical or intellectual justification left for it. The only explanation is that this is all that ministers and officials in the Johnson administration – never the most thoughtful of people – know about. And possibly the only people they know remain the only remaining advocates of tickbox in the whole wide world.

So farewell then Serco, G4S and all the others, as E. J. Thribb used to say in the days when privatisation seemed like a pretty neat idea. It was a fine affair, but now it’s over – or it soon will be.

This first appeared on the New Weather blog

Get a free copy of my medieval Brexit thriller on pdf when you sign up for the newsletter of The Real Press.

November 1, 2020

What do they know of science who only science know?

This post first appeared on the Radix UK blog...

This post first appeared on the Radix UK blog...

What do they know of the England who only England know,” wrote the much-derided poet Rudyard Kipling more than a century ago. After listening to the excellent debate on science and politics last night, which Radix organised, I wondered whether we should say the same of scientists.

Or indeed anyone whose narrow field of expertise gets in the way of understanding the world. Should we also for example say: What do they know of epidemiology who only epidemiology know? I don’t know.

Some of the debate goes back to C. P. Snow’s famous paper on the Two Cultures. The critic F. R. Leavis condemned it without reading it - “To read it would be to condone it,” he said. And I have some sympathy with that on the grounds that Leavis was objecting, I think, to the idea that arts and science were somehow equal, with the same complexity and moral validity. Which they are not.

Still, everyone – however little they may think about molecules – has something to learn from scientific method, as mediated through the two great 20th century philosophers of science, Popper and Kuhn. Mere knowledge of human or bureaucratic processes is not expertise, for example. Nor is it science.

What seems to me to be, in the long run, unfair to scientists and their reputations is the way that the media use them to fight what are essentially political battles.

Take the Great Barrington declaration, for example, which has barely been reported at all in the UK, where the three top epidemiologists in the world denied that lockdowns were the most effective way forward - on the grounds that they killed as many people as they saved. They were immediately condemned in the American press for "advocating mass murder”.

The day Radix published their declaration in the UK – on the grounds that somebody should – they were the subjects of a hatchet job in the Guardian, in the grounds that one of them had been interviewed on a dodgy US radio programme and that some of the people who had signed their declaration turned out to be (shock horror!) homeopaths.

Now let us leave aside the fraught issue of homeopathy. It seems to that when nobody reports the three top epidemiologists, and when a former law lord like Jonathan Sumption can say (thank you Charlotte!): “This is how freedom dies. When societies lose their liberty, it is not usually because some despot has crushed it under his boot. It is because people voluntarily surrendered their liberty out of fear of some external threat” – then we have a problem.

We have not yet had the lockdown riots that are beginning to emerge in continental Europe. But if most of those who dare step forward and doubt the establishment consensus are right-wing nutcases, then we will be at their mercy for some time to come.

Get a free copy of my medieval Brexit thriller on pdf when you sign up for the newsletter of The Real Press.

October 2, 2020

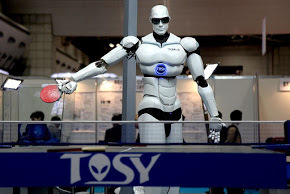

Robots in care homes? No thanks!

This post first apppeared on the Radix UK blog...

I am one of the few people in theUK to have written at any length about the need for authenticity. As such, it ought perhaps to be me who points out what a thoroughly bad idea it is to use robots in care homes to counteract loneliness.

That was the story on the front page of a recent Guardian, and it seems to me to suffer from the whole corrosive technocratic worldview which brought us exam grades by algorithm and government by tickbox.

It reminds me horribly of the ideas put about by Americans in the early 2000s about the non-existent difference between real and virtual. Why is it that Americans are so susceptible to this kind of nonsense?

“Once your house can talk to you, you may never feel alone again,” said The Futurist magazine. I’m not so sure. Nor was I convinced by Machines That Think author Pamela McCorduck about the geriatric minder robot that looks after people by saying “tell me again” to their stories – “and means it”.

Those interviewed in the Guardian article were at pains to point out that they were not suggesting that robots take over from human beings entirely. But that really isn't the point. The idea is that care home staff, run off their feet, might get a bit of a break by plugging their charges into one of these. As if there was any chance of going back to the human beings if that was ever to happen.

So, no doubt you are wondering why the older people in the experiment had 'improved mental health' as a result. That is simple for anyone who knows about the famous Hawthorne experiments in the 1920s and 30s.

It is because of all the attention paid to them by the researchers, not the ersatz attention paid to them by the machines.

It is an elementary mistake, and one that those schooled in the delusions of tickbox should be able to recognise.

Get a free copy of my medieval Brexit thriller on pdf when you sign up for the newsletter of The Real Press.

David Boyle's Blog

- David Boyle's profile

- 53 followers