David Boyle's Blog, page 3

April 19, 2022

Why Boris and Biden need to be a little more measured about Ukraine

This post first appeared on the Radix UK blog...

When I was writing my Tickbox book, I found myself researching the great American technocrat Robert McNamara,

Like many other people in deep thrall to Tickbox, McNamara was also pretty emotional. His career was characterised by extreme loyalty, not just to Kennedy, but for a time also to Lyndon Johnson, his successor. It was a passion that nearly sent him insane, but it also led to his egregious habit of quoting selective numbers in public to defend his president – even, as it turned out, as he turned against the Vietnam War.

Still, it was the calculating element of McNamara’s personality, not the romantic side, that first brought him into conflict with the US defence establishment as Kennedy’s Defense Secretary – and particularly with his old boss, the USAAF general Curtis LeMay.

As such, McNamara was next to Kennedy throughout the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, urging a blockade rather than the massive strike favoured by some of the top brass. The most implacable of his opponents was his old chief Curtis LeMay, now also reputed to be the original for the Peter Sellers film Dr Strangelove.

“Kennedy was trying to keep us out of war,” McNamara said much later. “I was trying to help him keep us out of war but General Curtis LeMay, with whom I served as a matter of fact in World War II, was saying; ‘Let’s go in. Let’s totally destroy Cuba’.”

More helpfully, the US ambassador to Moscow Tommy Thompson was also there and urged Kennedy to reply directly to Khrushchev’s earlier, less aggressive message, where he promised to remove the missiles in return for a face-saving undertaking that the US would not invade Cuba. He worked out that Khrushchev needed a device to allow him to step back, and – as it turned out – he was right.

As McNamara tightened his grip over US defence policy, LeMay became increasingly implacable. He ended his career as running mate to the racist governor George Wallace in the 1968 presidential election. But that is beside the point.

The real point I am making here is about the importance of finding a face-saving formula. McNamara and Thompson realised this, and so did Kennedy.

The problem we have is that the situation in Ukraine is increasingly dangerous because both the British prime minister and the US president seem determined to ‘win’ the conflict there.

They are neither of them stupid, but the truth is that the Ukrainian war came as a godsend to both men. Johnson could grandstand and avoid the fallout from ‘partygate’…

What result are they really intending? That somehow the cavalry will sweep through and arrest Putin, bearing him off to the Hague and his personal war crimes prosecution?

That isn’t going to happen. Khrushchev did not long survive the Cuban crisis. He was removed from power by Kremlin insiders like Leonid Brezhnev, partly because of what had happened there. He was retired from 1964-71.

Putin may well need to be ousted, as Biden says, but – since we are not into regime change any more these days – then that can’t be our decision.

The Russians will have to do it. And only then – maybe – we might find a way to putting him and other war criminals behind bars.

I am not drawing parallels with Khrushchev. The Cuban Missile Crisis was nothing like the war in Ukraine. But we may still be heading for some kind of Cuban style stand-off.

That is the point when I am praying, for the sake of the world, that there is someone like McNamara or Thompson to put the case for a chink of hope, rather than just unthinking gung-ho voices like Biden and Johnson.

There can be no winners in these conflicts and, although the Ukrainians are at the moment pushing back the Russians – with huge skill and courage – I am not sure how long this will last.

And even if it does, we don’t want to push Putin into such a tight corner that he does something even stupider.

http://bit.ly/HowToBecomeAFreeanceWriter

April 11, 2022

Why we need to start embracing complementary health

This first first appeared on the Radix UK blog...

I am treading on eggshells here and I am far from sure I will reach safely to the other side. We shall see.

As many of you will know, I have been diagnosed with parkinsonism – a variant (though nobody is quite sure which) of Parkinson’s Disease. That has made me peculiarly interested in complementary health of all kinds – even if I hadn’t had chronic eczema for years too.

The difficulty is just how little there is of it over here. Rather as alternative education has been squeezed out by the ‘consensus’ in the UK, so has complementary health. It is as if we in the UK have started believing our systems so much that we can imagine no alternative.

I have found acupuncture, osteopathy and homeopathy really helpful – especially, perhaps, the latter. Nutrition is not really complementary in the same way, but I kind of think I would have been better if I had changed my diet earlier.

I mention this because homeopathy has been the focus of huge negativity from both sides of the political spectrum.

There is something naive about the mainstream opinion that there is no ‘evidence’ for any of these – as if any pharmaceutical company was dashing to carry out the research, or any medical researcher was keen to destroy their career by asking them to fund it.

I am not being 'anti-science' here - as I am occasionally being accused of. Quite the reverse: I am a follower of Karl Popper. I really believe political rhetoric as shifted us too far from scientific method.

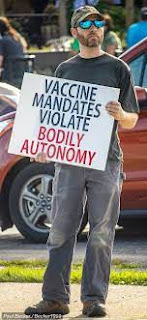

Nor am I an anti-vaxxer – I’ve had three jabs and covid too – but equally it has been clear to me for some time that there was an emerging issue about our immune systems. I have no idea whether this has anything to do with overloading our immune systems with childhood immunisations – or maybe it’s our appalling food, air quality or the strange electro-magnetic pulses we need to keep the economy ticking over, or something else.I’m not a medic or a scientist, so I don’t know – I am asserting this as a patient. But I think we will need to look beyond our current systems and knowledge at some point.

Yet although I’m finding it hard to hear anyone discussing these issues in the UK, there is a huge underground cascade of videos from the USA on these subjects – mainly related to the peculiar experience of the pandemic we have all just lived through.

The trouble is that, largely because of the two political camps in the USA, this debate can’t really take place openly – because of the assumption from both sides that anyone at all sceptical of prevailing medical opinion in the USA must be a Trump supporter.

That makes many of my own more sceptical opinions (which I am too nervous to spell out here) shunnable by the mainstream. It isn't hard to understand why so many American sceptics are veering off towards Trump-style populism.

Why is everyone so sick these days, I asked in a recent blog? Why are our immune systems so often malfunctioning? These are important issues which can’t be dodged forever. They will emerge again, and you can see some of those US doctors – who have been cancelled in various ways – beginning to articulate a series of new approaches, while the mainstream is still trying to push opposing views under the carpet. And especially on the left: hence the danger here.

In fact, I believe that those who have suffered chronic health problems – who have in some ways found themselves maintained in that by the health and pharma systems – may over the next few years forge themselves into an important and influential movement. They will be looking afresh at issues like 5G and other mass experiments, or low-level radiation.

They may well be sceptical abut 'experts', as Michael Gove was - drawing a distinction, as I do, between genuine expertise and those who are just steeped in the current system or ways of working, as i set out in my book Tickbox.

It may be 20 years before this alliance feels themselves as strong politically as they need to be – but if they find themselves aligned with Trump and other climate sceptics then these will also be carried along to power alongside them.

That is why it is so vital to organise some kind of post-pandemic rapprochement between complementary health and the radical centre. Don’t forget that was how the Five Star movement took its first steps to power in Italy by linking with everyone they could find online with an interest in complementary health.

The alternative is that we will be forced to face down another version of Trump when it really matters for people and planet. There is no necessary link between climate scepticism and medical scepticisms. And we need the latter to defeat the former – before it's too late!

http://bit.ly/HowToBecomeAFreeanceWriter

April 3, 2022

Forty years on: don't let's go back there!

This post first appeared on the Radix UK blog...

It feels a little exhausting to say so, but the invasion of the Falkland Isles took place exactly four decades ago on Saturday. Ah yes, I remember it well.

I was a junior reporter, a trainee, on the Oxford Star in those days. On that particular day (2 April 1982), I was heading for a weekend training course in Oxfordshire with other trainees and I remember picking up a hitchhiker on the Oxford bypass, who turned out to be a naval rating who had been unexpectedly ordered back to his ship.

It was my first indication that something was really happening.

I have two points I want to make about that time.

First, just how unusual war felt in those days. I did not remember any conflict – apart from Northern Ireland, of course – for my whole childhood (I was born two years after the Suez debacle). Harold Wilson had managed to keep us out of the Vietnam war. There had been British peacekeepers sent on to the island of Anguilla in 1966, but in the end the government sent London bobbies (the New York Times headlined the affair ‘The Lion that Miaowed’)!

These days, when we have endless military challenges, it is hard to remember what it felt like then to end a period of almost complete peace.

That was one reason why I was, at the age of 23 and newly obsessed with politics, so keen to dash back to my bedroom between lectures to listen in to the debate in the Commons – and it was strange to find only one of my colleagues seemed keen to discuss it (how are you, Candida?).

Looking back to that debate, it was amazing to remember how bellicose Michael Foot and the Labour opposition were in the immediate aftermath of invasion – perhaps because they smelled blood: the Thatcher government was desperately unpopular at that stage, and Foot may have believed that nothing could be done and that this would prove their final straw.

The second point I want to make was that the recovery of Margaret Thatcher’s reputation and the apparent success of her government can be dated pretty accurately to the moment that the destroyer HMS Sheffield was sunk by an Exocet missile (4 May).

I had been out canvassing for the Liberals that evening in south Oxford (for Victoria Mort) and I took a break – and, like everyone else – I saw the lugubrious Ministry of Defence spokesperson Ian Mcdonald announcing about the sinking.

Going out again afterwards. I found the mood had completely changed. Someone had even nailed a copy of the Labour election address to a telegraph poll and scrawled the word ‘TRAITOR’ across it.

Looking back, I have a feeling that was when the tide turned against the Liberal-SDP Alliance.

You can see the same difference with the fly-on-the-wall documentary Warship¸ two series of which I have been watching on My5 – which is upbeat, thrilling and a relaxed view of the navy, as the Duncan is involved in a missile strike on Syria after it used chemical weapons. Compare that to the 1976 series Sailor, an uptight, class-obsessed view of the oldest ship in the fleet, the Ark Royal – where Captain Gerard-Pearse is seen complaining that none of his instruments are working correctly.

It was the same distinction between the film Chariots of Fire (1981) and Lindsay Anderson’s last film Britannia Hospital (1982), with Leonard Rossiter playing a slightly cynical hospital manager trying to smuggle the Queen in through the picket lines outside.

Say what you like about the old ways of seeing the world, I definitely prefer Chariots of Fire, the unexpected success to the unexpected, and undeserved flop. It looked back beyond that feeling of exhausted cynicism that prevailed in Britannia Hospital – or in Ark Royal in Sailor or any other metaphors for the nation in the late 1970s.

For all my frustrations with the current state of the nation, I don’t want to go back there.

Picture courtesy of Argentina.gob.ar (Gobierno de Argentina) - https://www.argentina.gob.ar/armada/gesta-de-malvinas/la-aviacion-naval

http://bit.ly/HowToBecomeAFreeanceWriter

March 29, 2022

We may be more generous than we fear we are

This first appeared on the RadixUK blog...

It is strange what a difference a few weeks make. As the refugees began to stream out of war-torn Ukraine, pouring into Poland and finding it hard to get to the UK, because of the usual, embarrassing bureaucratic barriers, many of us watched with comfort and shame – a mixture of the two – to watch BBC news film of the generous Germans crowding into Berlin railway station to offer their homes to desperate Ukrainian families.

It just went to show, something or other – we said to ourselves, fearing that it was just the Germans or just the continentals. If only we British could be a little more like that – or so we thought…

Fast forward a couple of weeks, to Michael Gove’s announcement about how we might do something similar, earning £350 a month by doing so – and we now all feel a little happier about it.

Then suddenly, 25,000 people had signed up for the refugee scheme within the first hour. OK, then there were more barriers to surmount…

But it demonstrated that the ordinary British were as hospitable as any other nation. It made us feel good about ourselves – which is tantamount to actually becoming better people (as Cressida Dick showed us back in 2017).

The implications are important. That when our political system is designed and interpreted by people who are more suspicious and nervous about people’s motives, then we will be too.

Nor is this just a problem about governments of the political right. Socialism seems in practice to encourage a kind of corrosive cynicism. In fact, both ends of the political spectrum are intolerable in different ways.

Instead, what we need to do is to share the business of government with people – a process known as co-production – because, as the late, great social innovator Edgar Cahn used to say, people have a fundamental need to feel useful.

Everyone does – not just those who are qualified to run public services. And I know from the experience of starting time banks, for example, that when you give people who have only been receiving care their whole lives the chance to give back, then you can transform their lives.

That seems to be to be an indication of what radical centrism might mean: it is the opposite of Home Office style tickbox suspicion and Leftist cynicism too.

http://bit.ly/HowToBecomeAFreeanceWriter

March 21, 2022

Why is everyone so sick these days?

This post first appeared on the Radix UK blog

This post first appeared on the Radix UK blogWhy are we so sick these days? I mean, really?

It wasn’t suppose to be like this – thanks to Beveridge, we had assumed that when you start treating people for free then it should cost less, year on year to keep people healthy. But it hasn’t worked out like that anywhere.

Of course, there are conventional reasons why health is so expensive - from changing diseases to the survival of more premature babies. But I don't think any of those are really adequate explanations.

There seems to be something about the way we live has made health as expensive as it has become. Because it is also the service of last resort, where all our problems come home to roost – including issues that the NHS was never designed to deal with. It hardly matters what it is – if it affects people adversely, then in the end it adds to the weight on the NHS.

So why? The first answer is that this to have something to do with the rise of mental ill-health. The WHO says that up to 300m around the world living with depression – which is pretty amazing, given that depression has only really been known as a problem since 1980.

I have been reading and absolutely fabulous book (full disclosure: the author, Susan Holliday, is a friend of mine), called Hidden Wonders of the Human Heart).

Back in 1975, the great psychologist James Hillman warned that “in psychiatry, words have become schizophrenic, themselves a cause and source of mental disease”.

I understand her quotation from a patient along these lines, when she describes “the frustration of trying to put something into a box that is slightly too small.”

I understand this also as a parallel to the related problem of Tickbox, where we are equally trying to break out of the stultifying definitions. The “words we use today to articulate our emotions arrive preconfigured,” writes Susan Holliday. "[They] become desiccated and opaque, like cataracts.”

Sue is describing the antidote to this problem, how to really see to “the ecology of the human heart”. I thoroughly recommend her book.

But of course there may be other reasons for the rise of chronic ill-health.

There are waves of online lectures crossing the Atlantic these days about various generalised interpretations of the huge numbers of people who are suffering from ill-defined combinations of anything from digestion to neurological issues, whether they have something to do with the gut-mind link or auto-immunity (see for example, Dr Peter Kan).

The danger is that we may no longer be allowed to question some of the central tickboxes of NHS delivery, on the grounds that our tramlines are “based on the science” and only those who are steeped in the existing ways are qualified to question them. Or on the grounds that the research has been done – without understanding that some theories will never get funded for testing.

That is why we still have to be vigilant about some of those technologies that our masters most approve of – like 5G or the next generation of nuclear energy. In case their failure to see outside their own definitions and boxes blinds us all to why we are no longer healthy.

March 7, 2022

Ukraine: when they start co-producing defence

This post first appeared on the Radix UK blog...

This post first appeared on the Radix UK blog...It is now a staggering three decades ago – half my lifetime – since I went to the city they are now calling Kharkiv, but which in those days we called Kharkov, in Ukraine.

I was going with a Russian film crew to meet up with Richard Denton, the British documentary film-maker. I had been working in a film called ‘Alec the Pole’, with the help of the brilliant Sandra Singer of the Red Cross and some Ukrainian tracers from Canada, to track down the family of Alec Kravchenko – who had recently told his daughter that the family wasn’t Polish at all, they were Ukrainian.

As it turned out, Alec had grown up through the terrible famine in the 1930s – deliberately created by Stalin to force the small farmers of he Ukraine into collective farms. Then he had spent his teenage years struggling as the war washed backwards and forwards over them. When the Soviets were in charge of the Kharkov area, his brother joined the Red Army; but Alec joined the Germans when they were conquering (a unit called Ostwach 555, which went straight to Italy, where he swapped sides and found himself in the Polish army).

He took the surname ‘Krawczynski’ and was known as Alec the Pole by friends and neighbours alike, living near Forres for the next four decades.

This probably saved his life, since captured Ukrainians were send back to the tender mercies of Stalin, after an agreement made at Yalta.

It was hardly surprising that extreme care and deep fear was the main feature of the few Ukrainians I met in those days – they had needed to learn to be.

They were also grief stricken and highly emotional. All Alec’s long-lost sisters we interviewed broke down rather than speak of the past – often just as we switched the camera on. To my great surprise, the same was also true of the next generation – those born after the war ended.

The other sense was that, although this was right at the end of the Soviet period – and the shops were empty and dismal – with its black soil and villages with domed churches at their heart, it felt European.

Yet despite the fear 30 years ago, contemporary Ukrainians and their heroic prime minister Vollodymyr Zelensky appeared to have recovered in an extraordinary way.

Although so many of the invaded nations of western Europe generated their own resistance movements, with the help of the BBC (see my book V for Victory ) in 1940-2, probably only the British and Finns faced potential invasion in this way. Churchill even wanted a poster with the slogan “You can always take one with you!”

I have been writing about co-production, when some of the functions of the state are shared out with ordinary beneficiaries, but I had not expected to see it in a war zone. Even so, I can’t think of any other way of categorising their new citizen army making their molotov cocktails (the term was coined by Finns fighting invading Russians in 1940).

I fear this period won’t last. I don’t think co-produced resistance can survive drone strikes and worse. I don’t believe that Wordsworth could have written that “bliss was in that dawn to be alive” in Paris if the ancien regime had been prepared to bombard the revolutionaries. Certainly he could not have said that “to be young was very heaven…”

We shall see. Unfortunately both Elinor Ostrom who coined the ‘co-production’, and Edgar Cahn who developed it, have both gone on to higher things. So there are few of us around interested in what it means – and what happens – when an army co-produces the defence of a nation.

In the long run, it clearly makes a difference to those taking part, and it gives them a real stake in the future – which is also how the same phenomenon works in the NHS and schools, for example. It is just how we get from here to there that worries me…

http://bit.ly/HowToBecomeAFreeanceWriter

http://bit.ly/HowToBecomeAFreeanceWriter

March 2, 2022

The scariest element: nuclear tickbox

This post first appeared on the radixuk.org blog.

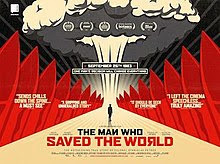

It was September 1983. Three weeks before, the Soviet air force had shot down a Korean airliner and Cold War tensions were running high. Stanislav Petrov, the hero of this story, was duty officer in the Soviet missile early warning centre at Oko, when the computers reported that a ballistic missile had been fired from the USA, closely followed by five more.

Within seconds, the system had gone through thirty stages of confirmation. The attack was real.

What was he to do? His training and military protocol demanded that he should report it. His colleagues who had trained entirely in the military (Petrov was trained as an engineer) certainly would have done so. There then would have followed the most tremendous nuclear holocaust, resulting in death and destruction on both sides. But he had a nagging doubt. He had been led to expect that any attack from the Americans would be overwhelming. Why fire only six missiles? What was the point?

So Petrov reported a false alarm, and thereby saved the world. It transpired that the system had been triggered by an unusual combination of clouds and sunlight as the Soviet satellite flew over North Dakota. He was praised to start with, but was eventually reprimanded for failing to organise the paperwork properly (tickbox, Soviet-style).

Then he was moved to a less sensitive position. Almost certainly, the NATO military would have acted the same way – missing the point, as tickbox does. The real point is that sometimes you have to break the rules or depart from the process to do a good job.

And in today’s tickbox world, that may often happen.

At the same time, tickbox is expanding everywhere. Judges in some US states are using predictive software to work out how likely it is that a guilty prisoner will reoffend so that they can impose the right sentence. Bear in mind that the prisoners will not yet have reoffended and that the algorithm puts a great deal of weight on their answers to questions like: ‘Is it ever right to steal to feed your children?’ The software tends to predict that black people are twice as likely to reoffend as white people.

The problem is that human beings need to provide some oversight, as Stanislav Petrov managed to do so heroically. The political problem is that tickbox can’t always tell the difference between what a group of people might need, sometimes for the good of the group as a whole, and what an individual might need.

In medicine, it may only be a matter of time before some individuals can be treated entirely by algorithm, but it is not clear that any tickbox system – however sophisticated – can ever treat everyone or provide a fair assessment of how likely it is that a criminal will abscond or reoffend, or that a small business owner will thrive or fail. In order to be fair, those kind of decisions require an element of trust, intuition and understanding of context.

This is the opposite direction of travel from that currently happening. That story is one that I included in my Tickbox book, and I couldn’t help thinking about it – not just in relation to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, but especially since Putin put his nuclear forces on ‘special alert’, whatever that means.

The problem here is exactly the same as the post office scandal – that when you are very senior in an organisation, you lose touch with reality. You tend to believe whatever figures are produced by computer programmes are true – in fact the tickbox delusion only really afflicts those who run the world.

This is increasingly a problem. “Computer-says-no culture runs the world,” said Marina Hyde in the Guardian about the postmasters and mistresses scandal:

“Today, technology is deferred to even in the face of human tragedy far more than it was 20 years ago. Spool onward in the timeline and you will find more and more examples of ways in which technology was deemed to know best. In 2015, it emerged that in one three-year period, 2,380 sick and disabled people had died shortly after being declared “fit for work” by a computerised test, and having their sickness benefits withdrawn. Today, bereaved parents are told that nothing can be done about the algorithms that pushed their teenage children remorselessly in the direction of content they believe ultimately contributed to them taking their own lives, even as a Facebook whistleblower recently said that firm was “unwilling to accept even little slivers of profit being sacrificed for safety…”

This has a clear implication for war – which is increasingly tickboxed – and it underlines the peril the world now finds itself…

We have a brief moment when everyone feels more proud and connected – thanks to the unprecedented feeling of unity across Europe, not just Germany and France but also Poland and Hungary.

But this is also now highly dangerous and, although we are in the early stages of this conflict now – and we don’t yet know how insane Putin has become – we need to peer ahead a little, if we can.

So what is likely to be on our minds, once the ‘gallant Belgium’ period is over and Liz Truss’s volunteer fighters will have been part of the Ukrainian international brigade for some weeks? I believe our own government may be facing complaints – rather as they were early in the Second World War – about their failure to pay anything towards protecting their own population.

If there is a tickbox issue about nuclear weapons on either side, it amounts to much the same thing. It is right that I should feel insecure for myself and my family – given what they are going through in the Ukraine – but is it right that I should feel quite as vulnerable as I do?

January 24, 2022

Why are we wrestling over Munich – all over again?

This post first appeared on the Aspects of History blog...

Why are we arguing again about appeasement, the Munich crisis and Neville Chamberlain, UK prime minister from 1937-40?

The immediate hook is the film of the Robert Harris novel, Munich: The edge of war – and its obvious agenda to rescue Chamberlain for history.

You will remember, especially if you have seen the film - which has been available on Netflix from last weekend - that Chamberlain’s 1938 Munich agreement handed over the northern region and defences of Czechoslovakia to Hitler without firing a shot.

The film itself is beautifully acted by an Anglo-German cast, and there is a brilliant performance by Jeremy Irons as an avuncular, inspirational Chamberlain.

I’m sure than Chamberlain was inspirational, in his way. But I am far less sure that we are right to regard Munich as tribute to what the historian AJP Taylor called “a triumph for all was best and most enlightened in British life”.

I have been fascinated by Munich because I have a family connection to those events – my great-aunt, Shiela Grant-Duff was Observer correspondent in Prague in the late 1930s and was engaged at the time in an increasingly desperate debate with Adam von Trott – who features in the film as the original of Paul von Hartmann, the anti-Nazi co-hero.

The other reason I have an interest is that I wrote a book about Munich (Munich 1938), with the context included – especially the plot to depose Hitler by his own generals the moment he had ordered an advance into Czechoslovakia, which Chamberlain so fatally undermined.

Two arguments have emerged that imply some kind of rethink might be necessary. First, that Hitler bitterly regretted not going to war in 1938 – though, as we saw in the film, he probably would have been deposed and shot if he had.

Second, was Chamberlain’s justification for getting Hitler to sign his paper promising never to go to war with Britain again: that the whole world would then see that he had broken his word.

But Chamberlain explained this to Lord Dunglass, his young PPS (later Alec Douglas-Home) on the plane home – not, as the film shows, to justify himself to Hugh Legat beforehand. It was actually a justification after the fact.

The problem was not that Chamberlain took no notice of the German army plot to depose Hitler. He never actually got that kind of approach in Munich. Partly because Adam von Trott was still living in China and still involved in his passionate debate with my great-aunt, which she described in her book The Parting of Ways.

Nor could he have done so at that stage anyway, as Irons-as-Chamberlain explains.

Yet Foreign Office officials in London and Paris had in fact already met representatives of the opposition, some months before. There was also a feeling among the British that they could not trust people who would betray their own government.

It wasn’t until 1943, when Dietrich Bonheoffer met George Bell, the bishop of Chichester, secretly in Stockholm, that the opposition took the British into their confidence by listing some of the conspirators – so many of the German army top brass. But even then, Anthony Eden would not, or could not, row back from the British position that they would insist on unconditional surrender, come what may.

The UK government definitely let down the German opposition to Hitler, and not just in 1938. But the real problem was what was done to Czechoslovakia in Munich.

The film makes it clear that the Czechs were not included in the four-partite conference. That was unfortunately only half true. In fact, there were Czech government representatives in the same building, but virtually under house arrest.

After the signing ceremony, Chamberlain and the French PM Daladier went to browbeat them into submission. “Can we not at least be heard before we are judged?” asked the Czech diplomat Hubert Masarik. The British and French shook their heads sadly.

The real problem with Munich was whether it is ever right to guarantee peace by forcing a smaller nation to accept invasion without fighting back.

It is true that war was avoided for a year – which gave both sides the chance to re-arm – but the Czechs had a sophisticated army which gave up without a fight, and 400 of their tanks (plus the factories that made them) became part of the Wehrmacht. When the British were forced back to Dunkirk 18 months later, they were pursued mainly by former Czech armour.

It wasn’t really the weakness of Czechoslovakia but its strength that so scared Chamberlain and his colleagues – the fear that, if the Czechs defended themselves, then we and the French would be drawn in (and the Russians).

That is why, after the agreement was signed, the British and French ambassadors to Prague roused President Beneš from his sleep to tell him that, if war broke out, not only would neither we nor the French intervene, but they would hold the Czechs responsible for any catastrophe which followed.

The following day, Beneš capitulated.

Ironically, Daladier recognised the truth - which is why he called his cheering Parisian crowd 'morons'. Chamberlain was appearing on the balcony of Buckingham Palace to acknowledge his own cheers at the same time.

But why are we having this debate now? (see what I wrote in Prospect, for example). Strangely, the divisions are along traditional lines, with the Times – the very heart of appeasement in the 1930s – backing Chamberlain now.

Luckily, I’m not the only one defending the Churchillian version of events - the Financial Times has now weighed in against the appeasers.

The divisions in UK politics were resolved after Dunkirk by the sacking of most of the senior positions in the nation. And as Labour leader a generation later, Michael Foot opened his 1983 election campaign by accusing the Tories of still being the ‘guilty men of Munich’, a faint memory of his Guilty Men book about Munich in 1940.

Perhaps the establishment has yet to get over their wounds from 1940 – and they want traditional Conservatism back. Just as the current standard-bearer seems to be in difficulties.

Was it really a coincidence that, the day before the film came out, David Davis used the same words to Boris Johnson that Leopold Amery did to Chamberlain in the no-confidence debate after the Norwegian campaign?

January 22, 2022

How can we avoid our politics drifting the way of the USA?

This post first appeared on the RADIXUK blog...

This post first appeared on the RADIXUK blog...What does a sceptical liberal do about great conspiracy theories like QAnon, the bizarre Republican party idea that Donald Trump is leading resistance to cabal of satanic paedophiles who have taken over the US government, led by his last presidential opponent Hilary Clinton?

I agree with Ben Rich last week – both that American politics seems to have descended into an abyss where facts no longer matter, compared to competing narratives, and that Gabriel Gatehouse’s BBC series is absolutely compelling on the subject.

Gatehouse dates the QAnon story to the death of Bill Clinton’s friend Vince Foster in 1993 – who killed himself by the Potomac and became the focus of an amazing series of stories, building on each other, via internet chat rooms into a whole parallel reality. And bizarrely spread partly by our very own Sunday Telegraph.

Now, I know from my past in television how quickly the death of politicians and gather about them the lurid patina of conspiracy. Like the death of the SNP vice chair Willie McRae, who is now widely regarded as having been murdered by the state, when in fact he killed himself (how do I know? I will explain another day…).

I am not a fan of conspiracy theories – for the reasons I set out before. But that does not make me entirely credulous about every official statement, no matter how many times I am told by the Left to “follow the science”.

In fact, like so many others who became politically aware during the 1970s, I’m not going to dismiss every scare story as nonsense. Because of that, I became a journalist and because of that that I presumably became a card-carrying Liberal at about the same time.

So yes, I am a sceptic, because I remember what happened with drugs like thalidomide. I am sceptical about the safety of 5G to human, animal and plant life – not because I believe it caused covid – but for the same reason I can’t believe that every vaccine is safe for everyone. They won’t kill most people, but there are a few for whom they can be dangerous.

Why? Because I remember the stories that have come and gone since 1980 which showed me that governments and establishments prefer their stories simple – especially when it comes to technological breakthroughs.

So when they vaccinated British troops bound for the first Gulf War in 1991 with a cocktail of different vaccines, there was a significant minority whose immune systems were overloaded – with disastrous effects.

So when a UK researcher discovered the human form of BSE – known by the tabloids as Mad Cow Disease and caused by adding dead cows to cattle feed - he was hounded out of his job by the security services.

This was not really the fault of politicians – which was how agriculture minister John Selwyn Gummer could find himself feeding his daughter a beef burger on live TV to show how safe it was. He was as much a victim of groupthink as everyone else.

That was how those middle class types who invested in Lloyds of London were hung out to dry some years later – because nobody official had accepted that, for the previous six decades, asbestosis had been killing people (more about this in my book Broke).

So what should we radical centrists do when you are confronted with so many bizarre tales about vaccines and the real causes of the pandemic.

This is what I think we should do – because a sort of polite scepticism is probably the right stance for most official pronouncements:To remember that deliberate conspiracies very rarely work – they are too complicated (like QAnon).To know that if the future of fake food threatens to damage our health, they will eventually be discovered in the end – and those who failed to investigate will reap the whirlwind.To seek out the voices that cling to objective reality.Like, for example, the fearless American writer Bari Weiss (I have been listening to her fascinating investigation into the story of Amy Cooper – who lost her job and was driven from her home for calling the police about a black birdwatcher in New York’s Central Park).

Because I don’t believe we have reached the level they have in the USA, where the competing narratives have disconnected themselves so completely from the facts that most people believe some kind of civil war is inevitable. In the UK, we need to avoid this kind of mob rule by clinging to civilised argument, both sceptically and optimistically.

The French philosopher Jacques Ellul used to say that, when you fight anyone, you get like them - and there is a sense that both sides of the American debate are getting increasingly like each other - certainly responsible for each other.

So let us end with what Bari Weiss says, in her review of the year since she resigned from the New York Times:

"Doomsday thinking is pleasing. Among liberals and progressives, I think it comes from a sort of self-indulgence and self-absorption. It makes you feel like the star of the show, struggling to survive under late capitalism, just one election away from the End of Democracy, and probably months from violent civil war. On the right, I think much of this comes from a kind of nihilism, or a justification for sitting back and doing nothing. Falling too deep into American catastrophe porn (let’s say, Libs of TikTok videos) lets you check out and take the blackpill. Liberalism tried and failed. These are the end times. Let’s get the popcorn and watch civilization collapse. But: What if America is actually in pretty good shape? What if we’re not in the last days, on the edge of slaughtering each other? Things always need improving. Suffering needs alleviating. (I wouldn’t be a writer if I didn’t think that.) But what if we took the panic level down a few notches...."

http://bit.ly/HowToBecomeAFreeanceWriter

http://bit.ly/HowToBecomeAFreeanceWriter

December 22, 2021

Do the Red Wall MPs hold the key to the centre ground?

This post first appeared on the Radix UK blog,,,.

This post first appeared on the Radix UK blog,,,.

I have to say that I feel sorry for Allegra Stratton. I completely agreed with Matthew Parris about her predicament – that was no laugh of hilarity against sick people, or anything remotely like it. It was a laugh of nervous embarrassment. As Boris Johnson must also have recognised.

So when he hung her out to dry, by implying otherwise, I felt pretty ashamed to have him as prime minister.

I’m not sure I can remember a time when everyone I met in southern England seemed so united in their rage at any prime minister. The conservative ladies around here can’t stand him, and my builders want the Queen to step in…

Yet, really – as Joe Zammit-Lucia suggested during the crucial week – Boris’ parties are really neither here nor there compared with issues around the latest covid Christmas.

It may be that when we find that the government has gone back to its old, incompetent ways, trying to tickbox their way to delivering the booster jab centrally at the same as encouraging panic – so that nobody can get one.

Personally, I find the whole business of queuing online out-tickboxes even tickbox (it involves the classic Tickbox situation whereby those at the centre are reassured by the numbers, and only those at the sharp end understand the chaos).

That is when people get seriously angry.

The question is whether the radical centre can profit by it in some way. I would suggest that there is an emerging political force that we could learn from, and perhaps vice versa: the Red Wall Conservative MPs.

These are people, as we keep being told, who are semi-detached from mainstream Conservatism. They are also less complacent and angrier than many of their fellow Tories.

Their only hope of being re-elected seems to me to lie in some kind of separate identity from the government.

I’m not suggesting some mass resignation. I am suggesting that, like the Liberal Unionists more than a century ago – or like the Co-operative Party inside Labour – they might begin to develop their own semi-autonomous leadership in the Commons. And with it, that sense among their constituents of who they are: standing for competence and devolution.

When they do that, I believe they might be the key factor in the major devolution of power that is so urgently needed in the UK. They might even be the means by which the Trusting the People report – published at the Conservative Party conference in October – might see the light of day as law. But they have to act together.

I hope that, if they did that, then we at Radix - alongside the New Social Covenant Unit - could help them think through where they stand as a party within a party…

http://bit.ly/HowToBecomeAFreeanceWriter

http://bit.ly/HowToBecomeAFreeanceWriter

David Boyle's Blog

- David Boyle's profile

- 53 followers