Jean Sheldon's Blog

December 12, 2020

A New Administration and Reasons for Hope

In mid-2020, I began searching for ways to occupy my time during the pandemic. I wondered if there were others like me, who, needing an outlet, would consider contributing to an anthology. The response was heartening and we have compiled those offerings into Now We Heal: An Anthology of Hope. The volume is unique and, we feel, a fitting way to celebrate the inauguration of our new administration in 2021. It is no secret that we have our work cut out for us in the coming years, but I am confident that together we can "build back better". Perhaps the easiest way to describe the book is to post the foreword which sums it up fairly well.

In mid-2020, I began searching for ways to occupy my time during the pandemic. I wondered if there were others like me, who, needing an outlet, would consider contributing to an anthology. The response was heartening and we have compiled those offerings into Now We Heal: An Anthology of Hope. The volume is unique and, we feel, a fitting way to celebrate the inauguration of our new administration in 2021. It is no secret that we have our work cut out for us in the coming years, but I am confident that together we can "build back better". Perhaps the easiest way to describe the book is to post the foreword which sums it up fairly well.

Foreword

One sunny day, pre-COVID-19, while walking in my neighborhood, I saw a group of young people in the local park playing soccer. A break was in order, so I found a patch of grass and took a seat to watch. Peppering the sidelines were a variety of onlookers, mostly parents and siblings I’d guessed, but there was also a young boy from the neighborhood who was there with what seemed a single intent—to cheer. He didn’t cheer for one side or the other, he simply cheered. He ran up and down the sidelines with the players and when anyone scored or made a great play, he cheered. His behavior never wavered, even lasting for several enthusiastic minutes after the final whistle. And along with his cheers came laughter. He laughed and cheered, cheered and laughed. It was puzzling at first, but as my mind and heart opened, I realized his behavior was not a misguided youthful response—he had figured out a far more important truth. While most attendees supported one side or the other and enjoyed only part of the game, he had found a way to appreciate every moment. With no investment in a winner, every success was reason to celebrate. How about that as a path to joyous and fulfilled living?

Our search for reasons to celebrate and be joyful in light of recent events has been challenging. We face change and disruptions that were unimaginable only a short time ago. EVERYONE is affected, which weighs heavily on our collective consciousness. In June of 2020, during a particularly discouraging stretch, the thought occurred that although I couldn’t change what life was offering, I could change my focus. I began to search online for new voices, new faces, and new ideas on how to move forward in our present difficulties. It was stirring to find the internet alive with people and organizations promoting positive ways of being, and offering solid ideas for change and growth. One thought, repeated often in cyberspace, finally caught my attention—be the change. It was time to stop looking for others to give me hope, and be a part of bringing hope to the forefront. But honestly, I wasn’t sure what I could do. After some effort reviving “lockdown” brain cells from their stupor, I considered that I could use my skills as a writer and publisher to share the stories others had to offer. A collection focused on hope and healing had potential because, judging by responses on social media, the world was starved for both.

My first outreach was to friend and fellow author, Dr. Veronica Esagui, who was enthusiastic about the idea and anxious to help. We shared our intentions with friends and family, posted our call to authors on social media and other venues and waited for a response.

Our request was for articles that showed who we are without hate, anger or rage. Stories that highlighted compassion and healing to move us forward and perhaps confront the painfully unresolved issues in our society that have become clear. We asked for stories that remind us of our boundless inner strength and the gifts we can offer because of it. We welcomed all genre, and, remarkably, many were submitted!

What will you find in this collection? One of our authors introduces you to an intergalactic granny who joins with protestors to save their planet. Another author, who lost loved ones to heart disease, shares her experience and knowledge on the advantages of a plant-based diet. From another, readers can explore an informative and enlightening introduction to the music of Gustav Mahler. Or perhaps you’ll find comfort in what an octogenarian shares about how her own life lessons enable her to thrive in this time of global pandemic. There are stories of a healing present and a healing future. Stories of resilience and hope. Stories that suggest ways to save the planet and the animals with which we share it. And if those aren’t enough to entice you, several poets share their inspirations in ways that only poets can.

With the uniqueness of our times in the forefront, I was aware that it took a good deal of inner fortitude to focus and write for this anthology. Because of that, I am doubly grateful to those who contributed. Thank you! Thank you also to Catherine and Jude for positive feedback and support during the mulling stages and beyond.

I’m glad to have had the opportunity to read and share the caring and healing words of our contributors. In the end, I guess I did look to others to find hope, but perhaps finding hope in each other is the real lesson after all. My hope is that you will find yours. And if you need me, I’ll be on the sidelines, laughing and cheering your every goal, your every success and your every effort.

A list of our wonderful contributors:Laurel Eloise LadwigJudy Fleagle

RC deWinter

Esther Halvorson-Hill

Veronica Esagui

Pat Fuller

Joan Maiers

Judy Stone

V. Falcón Vázquez

Marilyn Johnston

John C. Fraraccio

Carolyn Clarke

Jean Sheldon

Rosalyn Kliot

Lori L. Lake

Donna Reynolds

Rena Robinett

Kim Conrad

Keith Manuel

WellWorth Publishing

Paperback : 182 pages $12.95

Kindle: $3.99

ISBN-13 : 978-0983813668

November 16, 2018

Then We Can Say—This IS Who We Are

Four years into the 21st Century the launch of Facebook changed the way the world socialized. It was followed in a short time by Twitter and a still growing variety of information exchange hangouts. I was drawn to the little blue bird nest where you can often find me “tweeting with my peeps.” (I can’t help but chuckle just writing that

Four years into the 21st Century the launch of Facebook changed the way the world socialized. It was followed in a short time by Twitter and a still growing variety of information exchange hangouts. I was drawn to the little blue bird nest where you can often find me “tweeting with my peeps.” (I can’t help but chuckle just writing thatTweets are, in a perfect world, brilliant and witty 280-maximum character comments, and peeps are those who follow you. Besides offering instant information, Twitter can be exciting, it can be aggravating, and, on an occasion or two, it can be downright fun. What makes it enjoyable for me is what makes most things enjoyable—the people. They are diverse, spunky, irreverent and all those things that make us uniquely human. It was on Twitter that I met Elizabeth Leonard.

Elizabeth is a Professor of History at Colby College in Maine, a Civil War historian, and an author. Two of her books examine the roles of women in the Civil War. Yankee Women: Gender Battles in the Civil War, shares the experience of three women who stepped outside traditional roles to serve in the Union Army, and All the Daring of the Soldier: Women of the Civil War Armies, discusses the varied reasons and roles of women who joined on both sides of the conflict. Other books from Professor Leonard include: Lincoln's Avengers: Justice, Revenge, and Reunion after the Civil War; Men of Color to Arms! Black Soldiers, Indian Wars, and the Quest for Equality; and Lincoln’s Forgotten Ally: Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt of Kentucky. Those endeavors alone are enough to keep a person busy full time, but the professor is also a guitarist, singer/song writer, a political activist and a knitter.

Elizabeth is a Professor of History at Colby College in Maine, a Civil War historian, and an author. Two of her books examine the roles of women in the Civil War. Yankee Women: Gender Battles in the Civil War, shares the experience of three women who stepped outside traditional roles to serve in the Union Army, and All the Daring of the Soldier: Women of the Civil War Armies, discusses the varied reasons and roles of women who joined on both sides of the conflict. Other books from Professor Leonard include: Lincoln's Avengers: Justice, Revenge, and Reunion after the Civil War; Men of Color to Arms! Black Soldiers, Indian Wars, and the Quest for Equality; and Lincoln’s Forgotten Ally: Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt of Kentucky. Those endeavors alone are enough to keep a person busy full time, but the professor is also a guitarist, singer/song writer, a political activist and a knitter. A few weeks ago, to my good fortune, I noticed a tweet announcing the release of her new CD “Mother’s Day.” After several days listening to the delightful collection, it occurred to me to share my thoughts, and, with the author’s permission, a few snippets from the recording. The music is American folk, a genre that musician Mike Seeger (Pete’s half-brother) defined as “all the music that fits between the cracks.” Folk musicians are story tellers, and Leonard’s knowledge of history and her story telling talents are evident in a number of songs. Also evident is her dedication to imagining and working toward the best for our country, our world, and humanity. Her music draws inspiration from what she sees around her, and she in turn stirs us with her music. Take a few minutes to listen and read, and, if you’re like me, you’ll catch the underlying sense of hope for our future because strength and resilience exists in each of us.

A few weeks ago, to my good fortune, I noticed a tweet announcing the release of her new CD “Mother’s Day.” After several days listening to the delightful collection, it occurred to me to share my thoughts, and, with the author’s permission, a few snippets from the recording. The music is American folk, a genre that musician Mike Seeger (Pete’s half-brother) defined as “all the music that fits between the cracks.” Folk musicians are story tellers, and Leonard’s knowledge of history and her story telling talents are evident in a number of songs. Also evident is her dedication to imagining and working toward the best for our country, our world, and humanity. Her music draws inspiration from what she sees around her, and she in turn stirs us with her music. Take a few minutes to listen and read, and, if you’re like me, you’ll catch the underlying sense of hope for our future because strength and resilience exists in each of us.Being a long-time feminist, I was moved by the song We’re Still Here. The CD liner notes explain that it was inspired by “wonderful, clever signs” at the recent women’s marches.

To listen click the link below.

We’re Still Here

We are, we are, we are here.

Daughters of the witches you could not burn,

Working our magic for a better world.

We are here, we’re still here,

Working our magic for a future without fear.

We are, we are, we are here.

Daughters of the workers whose wages you stole,

Still fighting for equality at work and at home.

We are here, we’re still here,

Fighting for justice and a future without fear.

Click link to listen:

Some browser require double click to access audio

We're Still Here audio

Most of us are familiar with this country’s long struggle to end bigotry and hate, but decades of research focused on race and gender in the Civil War give Elizabeth Leonard unique and expansive insight. The Battle of Charlottesville offers a painful reminder that events in Charlottesville, Virginia in August of 2017, show the long way we still have to go.

The Battle of Charlottesville

You say, that the Battle of Charlottesville

is not who we are, well I disagree.

With these well-chosen markers of an ugly American past

It’s who we are, who we’ve been, but not who we can be

If we remember, we remember,

All the ones who bled and died that summer day.

In the great battle of Charlottesville,

Where white bigotry and hatred were so proudly on display.

If we remember, we remember,

Who we are is not who we must be.

If we remember the battle of Charlottesville,

Someday we’ll end this war,

We’ll set each other free.

Remember.

Click to listen:

The Battle of Charlottesville

Thomas Jefferson said: "When injustice becomes law, resistance becomes duty." For NFL player Colin Kaepernick, the unjust killing of scores of African Americans by police was reason to resist. Below is a link to the powerful song, Take a Knee, in its entirety. From the liner notes: “This song, combining a modified version of the hymn Lift Every Voice and Sing with story-telling verses whose rhythm and chord progression are based on the Star-Spangled Banner, honors the long history of Americans challenging the blind worship of our national symbols.”

Click to hear Take a Knee

There are 14 diverse and thought-provoking songs on this recording. I love them all. Each evoke images—from a fist clenched in protest to a mother’s hands meditatively knitting; from humanity gathered for battle, to humanity gathered in love and support. This old folk music fan found the voices, words and instruments akin to a warm, embracing hug, and the sad and angry refrains reminded me that I am not alone in the struggle as our nation searches for who we are, and who we will become. I have hope for us, for our country, and for our world. I have hope because of the work people like Elizabeth Leonard contribute creatively, intellectually, emotionally and physically to move us forward so that someday we can say—with our heads high and our hearts open—this IS who we are!

One final song, because it makes me smile and because, should reincarnation indeed be what the future holds, I know my preference If I Get to Come Back.

If I Get to Come Back

I always say, if I get to come back.

I don’t need a pedigree, papers or plaques.

I don’t need a castle, or a throne with gold tassels.

Just let me return as a pampered house cat.

I always say, if I get to come back.

I don’t really care if I’m white, brown or black.

Docile or crabby, calico or tabby.

Just let me return as a pampered house cat.

Click to listen:

We're Still Here audio

If you’re interested in acquiring a copy of the CD for you or to share as a gift, they are $10 each and you can do so by emailing edleonar@colby.edu

Mother’s Day by Elizabeth LeonardList of songs: If I Were a House; Button, Button; The Battle of Charlottesville; We’re Still Here; This Path We’re On; If I Get to Come Back; The Knitter’s Tao; Reasons to Stay; How to Silence a Problem Child; Take a Knee; Not; Mother’s Day; Passages; Don’t You Worry

This article was originally published on Me-AtLast.

October 1, 2012

Helen Keller Social Activist

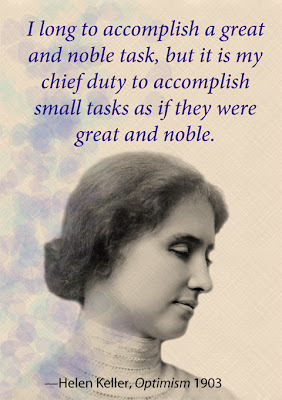

Helen Keller was born on June 22, 1880, in Tuscumbia, Alabama with both sight and hearing. At 19 months, she contracted a disease that although short lived, left her deaf and blind. The story of her astonishing achievements against what seemed impossible odds inspired movies, newspaper and magazine articles, and books. Many focused on the years with her teacher, Anne Sullivan, which is why she is often remembered as an author and lecturer who worked tirelessly for the blind and deaf around the world. It may also be why she is less known for her active role in labor movements, woman suffrage, socialism, and pacifism.

Helen Keller was born on June 22, 1880, in Tuscumbia, Alabama with both sight and hearing. At 19 months, she contracted a disease that although short lived, left her deaf and blind. The story of her astonishing achievements against what seemed impossible odds inspired movies, newspaper and magazine articles, and books. Many focused on the years with her teacher, Anne Sullivan, which is why she is often remembered as an author and lecturer who worked tirelessly for the blind and deaf around the world. It may also be why she is less known for her active role in labor movements, woman suffrage, socialism, and pacifism.Her passionate and sometimes vocal involvement annoyed people who believed a person with disabilities (and women) should remain silent. Southern relatives disapproved of her support of the NAACP and her involvement in the establishment of the ACLU. The Nazis burned her books, and her writings and activities interested the United States government enough to earn her a file with the FBI. As she became more vocal, her fame came under attack. Some even claimed her political leanings were because of her disabilities. I suppose that could hold a grain of truth. It was because of her disabilities that she began working for others like her, and became aware of the disproportionate numbers of disabled in lower income brackets.

It was not criticism of her beliefs that prompted her to soften her Socialist rhetoric, but rather an overwhelming desire to further the work of the American Foundation for the Blind (AFB). She was afraid her own political views would take away support from the organization. That did not stop her from working for her causes. She continued less visibly, but with equal passion.

The aim of all government should be to secure to the workers as large a share as possible of the fruits of their toil. For is it not labor that creates all things? 1924 letter to Senator Robert M. La Follette from Helen Keller.

When Helen graduated from Radcliffe in 1904, she had already published her autobiography The Story of My Life, 1902, and Optimism an Essay, 1903.

When Helen graduated from Radcliffe in 1904, she had already published her autobiography The Story of My Life, 1902, and Optimism an Essay, 1903. "The highest result of education is tolerance. Long ago men fought and died for their faith; but it took ages to teach them the other kind of courage—the courage to recognize the faiths of their brethren and their rights of conscience. Tolerance is the first principle of community; it is the spirit which conserves the best that all men think. No loss by flood and lightning, no destruction of cities and temples by the hostile forces of nature, has deprived man of so many noble lives and impulses as those which his intolerance has destroyed." Helen Keller, Optimism An Essay

On Woman Suffrage

From the essay, Why Men Need Woman Suffrage, 1913"Anyone that reads intelligently knows that some of our old ideas are up a tree, and that traditions are scurrying away before the advance of their everlasting enemy, the questioning mind of a new age. It is time to take a good look at human affairs in the light of new conditions and new ideas, and the tradition that man is the natural master of the destiny of the race is one of the first to suffer investigation.

The dullest can see that a good many things are wrong with the world. It is old-fashioned, running into ruts. We lack intelligent direction and control. We are not getting the most out of our opportunities and advantages. We must make over the scheme of life, and new tools are needed for the work. Perhaps one of the chief reasons for the present chaotic condition of things is that the world has been trying to get along with only half of itself." See the entire essay,

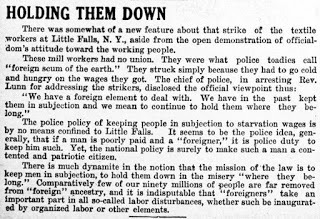

On Workers RightsA letter and donation to the striking Little Falls, NY textile workers

The Tacoma Times, November 13, 1912"I am sending the check which Mr. Davis paid me for the Christmas sentiments I sent him. Will you give it to the brave girls who are striving so courageously to bring about the emancipation of the workers at Little Falls? They have my warmest sympathy. Their cause is my cause. If they are denied a living wage, I also am denied. While they are industrial slaves, I cannot be free. My hunger is not satisfied while they are unfed. I cannot enjoy the good things of life which come to me, if they are hindered and neglected, I want all the workers of the world to have sufficient money to provide the elements of a normal standard of living—a decent home, healthful surroundings, opportunity for education and recreation. I want them all to have the same blessings that I have. I, deaf and blind, have been helped to overcome many obstacles. I want them to be helped as generously in a struggle which resembles my own in many ways."

On SocietyFrom an article in the Socialist newsletter Justice. October 1913"The structure of a society built upon such wrong basic principles is bound to retard the development of all men, even the most successful ones because it tends to divert man's energies into useless channels and to degrade his character. The result is a false standard of values. Trade and material prosperity are held to be the main objects of pursuit and conquest, the lowest instincts in human nature—love of gain, cunning and selfishness—are fostered."

On SocietyFrom an article in the Socialist newsletter Justice. October 1913"The structure of a society built upon such wrong basic principles is bound to retard the development of all men, even the most successful ones because it tends to divert man's energies into useless channels and to degrade his character. The result is a false standard of values. Trade and material prosperity are held to be the main objects of pursuit and conquest, the lowest instincts in human nature—love of gain, cunning and selfishness—are fostered."

In 1932, Helen Keller had the opportunity to visit the top of the Empire State building, after which she received a letter from Dr. John Finley, inquiring about her experience.

I am only one, but still I am one. I cannot do everything, but still I can do something; and because I cannot do everything, I will not refuse to do something that I can do. Helen Keller

Frankly, I was so entranced "seeing" that I did not think about the sight. If there was a subconscious thought of it, it was in the nature of gratitude to God for having given the blind seeing minds. As I now recall the view I had from the Empire Tower, I am convinced that, until we have looked into darkness, we cannot know what a divine thing vision is.

Perhaps I beheld a brighter prospect than my companions with two good eyes. Anyway, a blind friend gave me the best description I had of the Empire Building until I saw it myself....

But what of the Empire Building? It was a thrilling experience to be whizzed in a "lift" a quarter of a mile heavenward, and to see New York spread out like a marvellous tapestry beneath us.

There was the Hudson – more like the flash of a sword-blade than a noble river. The little island of Manhattan, set like a jewel in its nest of rainbow waters, stared up into my face, and the solar system circled about my head! Why, I thought, the sun and the stars are suburbs of New York, and I never knew it! I had a sort of wild desire to invest in a bit of real estate on one of the planets. All sense of depression and hard times vanished, I felt like being frivolous with the stars. But that was only for a moment. I am too static to feel quite natural in a Star View cottage on the Milky Way, which must be something of a merry-go-round even on quiet days. See the entire letter.

Her vision is even more astonishing when you remember it came without sight and hearing. She taught that we are all one. That each of us has something to offer. How many of us "see" with that clarity?

Her vision is even more astonishing when you remember it came without sight and hearing. She taught that we are all one. That each of us has something to offer. How many of us "see" with that clarity? No pessimist ever discovered the secrets of the stars, or sailed to an uncharted land, or opened a new heaven to the human spirit. Helen Keller Optimism an Essay

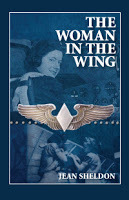

Jean Sheldon Mystery Writer

August 1, 2012

Matilda Josyln Gage

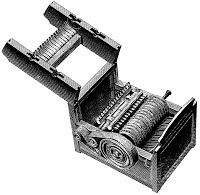

Cotton GinThe sudden death of her husband, General Nathanial Greene in 1786, left Catherine Littlefield Greene to raise five children and run a struggling plantation. She hired and manager and succeeded in both. In 1792 she rented a room to a young teacher named Eli Whitney, but was less interested in his scholarly work than his mechanical skills. She explained the difficulties of separating the course hulls of green-seed cotton and suggested an idea for a cotton gin. How much involvement she had in the design and construction isn't clear, although there is evidence that Whitney's original design had wooden teeth that didn't work and it was Catherine Green who recommended wire as was used in the successful model. Whitney patented the product and was credited with the invention. He paid Green royalties on the patent.

Cotton GinThe sudden death of her husband, General Nathanial Greene in 1786, left Catherine Littlefield Greene to raise five children and run a struggling plantation. She hired and manager and succeeded in both. In 1792 she rented a room to a young teacher named Eli Whitney, but was less interested in his scholarly work than his mechanical skills. She explained the difficulties of separating the course hulls of green-seed cotton and suggested an idea for a cotton gin. How much involvement she had in the design and construction isn't clear, although there is evidence that Whitney's original design had wooden teeth that didn't work and it was Catherine Green who recommended wire as was used in the successful model. Whitney patented the product and was credited with the invention. He paid Green royalties on the patent. In 1798, twelve year old Betsey Metcalf of Providence, Rhode Island couldn't afford the hat she saw in a shop window and invented a method of braiding straw from her family's barn to make one of her own. Like Catherine Greene, Betsey Metcalf, afraid of social criticism, did not patent her idea. Mary Kies, of Killingly, Connecticut cared little about what the neighbors had to say and applied for and received the patent. Because of these women and a ban on imports, the straw hat industry grew rapidly in New England.

Anna Ella CarrollAre you familiar with the Tennessee River Campaign of 1862? An investigation into the Civil War would tell you it was considered by many as the Union army's first major success. Further research would credit Ulysses S. Grant with the campaign's triumph but might not reveal that the plan changing the course of the war came from Anna Ella Carroll of Maryland. Assistant Secretary of War Thomas A. Scott and others at the War Department recognized the strategy was written by a military genius—a genius known as A.E. Carroll. After the war, an attempt to enter Carroll's role in the official record was squelched for fear that it would outrage the general population to find the war had been directed not only by a civilian, but a female civilian. She received no compensation or credit for the action that saved the union.

Anna Ella CarrollAre you familiar with the Tennessee River Campaign of 1862? An investigation into the Civil War would tell you it was considered by many as the Union army's first major success. Further research would credit Ulysses S. Grant with the campaign's triumph but might not reveal that the plan changing the course of the war came from Anna Ella Carroll of Maryland. Assistant Secretary of War Thomas A. Scott and others at the War Department recognized the strategy was written by a military genius—a genius known as A.E. Carroll. After the war, an attempt to enter Carroll's role in the official record was squelched for fear that it would outrage the general population to find the war had been directed not only by a civilian, but a female civilian. She received no compensation or credit for the action that saved the union.During my research, I came across a YouTube video (actually an audio recording), of Agnes Moorehead performing in a Cavalcade of America radio episode about Anna Ella Carroll. It aired in June of 1941. It is interesting to realize that this story, omitted from history books, played on the radio. (If the video doesn't start, click on the YouTube button on the lower right and listen to it there. It's worth it. Just remember to come back.)

Matilda Joslyn GageBut, this post is not about Catherine Green, Betsey Metcalf, or Anna Ella Carroll. So why all these interesting facts? I learned about Greene and Metcalf from a pamphlet called Woman as Inventor written by Matilda Josyln Gage and published by the New York Woman Suffrage Association in 1883. A piece called Who Planned the Tennessee Campaign of 1862: A few generally unknown facts in regard to our Civil War, also by Gage, revealed the remarkable story of Anna Ella Carroll.

Matilda Joslyn GageBut, this post is not about Catherine Green, Betsey Metcalf, or Anna Ella Carroll. So why all these interesting facts? I learned about Greene and Metcalf from a pamphlet called Woman as Inventor written by Matilda Josyln Gage and published by the New York Woman Suffrage Association in 1883. A piece called Who Planned the Tennessee Campaign of 1862: A few generally unknown facts in regard to our Civil War, also by Gage, revealed the remarkable story of Anna Ella Carroll. You might be familiar with Matilda Gage for her role as co-editor with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony of the first three volumes of The History of Woman Suffrage (1881-1887). Or, you might have read the book written five years before her death, Woman, Church and State. It is more likely that you know very little about Gage.

Matilda Electa Joslyn, an abolitionist, suffragist, author, lecturer, and radical thinker, was born in Cicero, New York in 1826. Her family home was a stop on the Underground Railroad. After her marriage in 1845 to Henry Hill Gage, their home also became a stop.

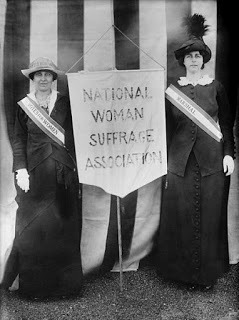

In 1848, with small children at home, Gage was unable to attend the first National Women's Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, New York. She made her public speaking debut in 1852 at the Syracuse convention. The movement, on hold during the Civil War, reconvened as the American Equal Rights Association, but with growing internal friction. Gage opposed supporting the ratification of the 15th Amendment unless it allowed votes for women. Others felt that securing the vote for all men would help women. The amendment, ratified in February of 1870, said: "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude." In 1869, Gage, Anthony, and Stanton founded the National Woman Suffrage Association. Two years later, Gage and other members tried to vote, only to find that women were not considered citizens. In 1872, Susan B. Anthony successfully cast a vote and was arrested. Gage said: "Susan B. Anthony is not on trial; the United States is on trial."

In 1848, with small children at home, Gage was unable to attend the first National Women's Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, New York. She made her public speaking debut in 1852 at the Syracuse convention. The movement, on hold during the Civil War, reconvened as the American Equal Rights Association, but with growing internal friction. Gage opposed supporting the ratification of the 15th Amendment unless it allowed votes for women. Others felt that securing the vote for all men would help women. The amendment, ratified in February of 1870, said: "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude." In 1869, Gage, Anthony, and Stanton founded the National Woman Suffrage Association. Two years later, Gage and other members tried to vote, only to find that women were not considered citizens. In 1872, Susan B. Anthony successfully cast a vote and was arrested. Gage said: "Susan B. Anthony is not on trial; the United States is on trial."In 1878, Gage bought a journal called The Ballot Box, which she renamed The National Citizen & Ballot Box and became editor and publisher. Stanton and Anthony were co-editors and the paper became the voice of the NWSA. This is a remarkable publication in any era, but especially in the late 1870s. Here are a few details from the prospectus:

The National Citizen will advocate the principle that Suffrage is the Citizen's right and should be protected by National Law, and that while States may regulate the suffrage, they should have no power to abolish it.

It will support no political party until one arises which is biased upon the exact and permanent political equality of man and woman.

The National Citizen will have an eye upon struggling women abroad, and endeavor to keep its readers informed of the progress of women in foreign countries.

As nothing is quite as good as it may yet be made, the National Citizen will, in as far as possible, revolutionize the country, striving to make it live up to its own fundamental principles and become in reality what it is but in name—a genuine Republic.

Gage's radical views became unpopular with the increasingly conservative movement. In 1890, she left the organization to found the Women’s National Liberal Union, fighting religious fundamentalists working to amend the Constitution and proclaim the United States a Christian nation. In 1893, she published Woman, Church and State and made clear her belief that the church was the greatest oppressor of women. I believe those views contributed to her near complete omission from historical records.

But Matilda Joslyn Gage is not forgotten. Not completely. A growing amount of information is available, much because of another remarkable women, Dr. Sally Roesch Wagner.

The Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation took root in 2000 when Sally Roesch Wagner, the leading authority on Gage, brought together a nationwide network of diverse people with a common goal: to bring this vitally important suffragist back to her rightful place in history. From the website of the Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation

Video streaming by Ustream Sally Roesch Wagner portrays Matilda Joslyn Gage at Bioneers in October of 2009.

Problems with the video? Try this link: Sally Roesch Wagner's website.

It was Sally Roesch Wagner's book

Sisters in Spirit

that prompted this month's post. In it, Wagner tells the remarkable story of how Native American women influenced our nation's early feminist. As we face another critical moment in the struggle for equality, the work of previous women must not be forgotten. Their voices will remain silent only if we allow that to happen.

It was Sally Roesch Wagner's book

Sisters in Spirit

that prompted this month's post. In it, Wagner tells the remarkable story of how Native American women influenced our nation's early feminist. As we face another critical moment in the struggle for equality, the work of previous women must not be forgotten. Their voices will remain silent only if we allow that to happen. There is a word sweeter than Mother, Home or Heaven; that word is Liberty. Matilda Joslyn Gage

July 1, 2012

Dorothea Tanning

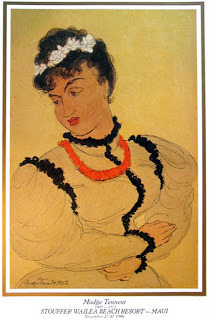

Dorothea Tanning | 1946Photograph by Man Ray © Man Ray Trust

Dorothea Tanning | 1946Photograph by Man Ray © Man Ray Trust

I recently read Dorothea Tanning's autobiography Between Lives: An Artist and Her World, published in 2001. Tanning died on January 31, 2012, at her home in New York. She was 101. The previous year, she published her second book of poetry, Coming to That. An artist, poet, and sculptor, Tanning is, unfortunately, more widely known as the wife of Max Ernst. As unfortunate as that might be, it troubled her less than to find her name permanently identified with surrealism. Although she was a member of the early movement, a style change in the mid-fifties took her to another level as an artist.

She was born August 25, 1910 in Galesburg, Illinois, about 50 miles east of the Mississippi River and 200 miles west of Chicago in the nation's heartland. It was a place she described as "…where you sat on the davenport and waited to grow up". At 16 Dorothea worked at the library and after high school attended Knox College, "the college that tried to teach me something, anything." But she was not a Midwestern girl at heart, having decided at age seven to live in Paris. At 20 she moved to Chicago to become an artist, concluding that it was on the way to Paris.

I like to think of it [my life] as a garden, planted in 1910 and, like any garden, always changing. There are expansions and diminishments as well as replacements, prunings, additions. One person’s garden, one person’s life. So far.

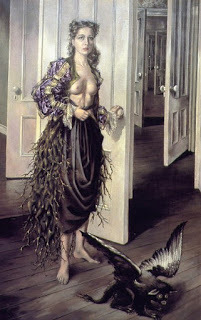

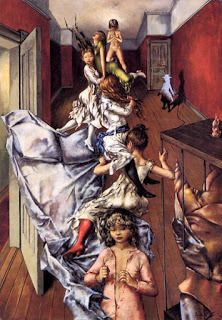

Birthday | 1942 | Oil on canvasPhiladelphia Museum of ArtShortly after her arrival in Chicago, she found a job as a hostess and attended drawing classes at The Chicago Academy of Art. Her teacher had little hope for her artistic talents, and as soon as she realized the school leaned toward commercial art, she had little hope of a lasting relationship. It was the only formal art training Tanning received and learned to paint by studying others' work. After losing her job at the restaurant, a move seemed inevitable. With $25 dollars in her pocket, she took one step closer to Paris—New York City.

Birthday | 1942 | Oil on canvasPhiladelphia Museum of ArtShortly after her arrival in Chicago, she found a job as a hostess and attended drawing classes at The Chicago Academy of Art. Her teacher had little hope for her artistic talents, and as soon as she realized the school leaned toward commercial art, she had little hope of a lasting relationship. It was the only formal art training Tanning received and learned to paint by studying others' work. After losing her job at the restaurant, a move seemed inevitable. With $25 dollars in her pocket, she took one step closer to Paris—New York City.In many ways, New York was no different than Chicago. She shared a flat with another woman artist and did odd jobs to pay the rent, but in 1936 she saw the Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and was changed forever. "But here, here in the museum, is the real explosion, rocking me on my run-over heels. Here is the infinitely faceted world I must have been waiting for. Here is the limitless expanse of possibility, a perspective having only incidentally to do with painting on surfaces. Here, gathered inside an innocent concrete building, are signposts so imperious, so laden, so seductive, and, yes, so perverse...they would possess me utterly."

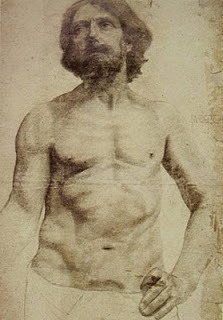

Avatar | 1947 | Oil on canvasIn 1943, Tanning was one of 31 women chosen for a first of its kind show in New York—all female artists. Also included were Leonore Carrington, Buffie Johnson, Frida Kahlo, Louise Nevelson, Meret Oppenheim, I. Rice Pereira, Kay Sage, Hedda Sterne, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Hazel Guggenheim, Pegeen Vail Guggenheim, Barbara Poe Levee, Alice Trumbull Mason, and others. Peggy Guggenheim, who produced the show, was said to have commented later that she should have been satisfied with 30 artists. It was her husband, Max Ernst, who was greatly attracted to Tanning's self-portrait, Birthday and suggested her for the show. He was also greatly attracted to the artist. After his initial visit, Dorothea and Ernst played chess every day for a week. Then he moved in and they stayed together until Max's death in 1976.

Avatar | 1947 | Oil on canvasIn 1943, Tanning was one of 31 women chosen for a first of its kind show in New York—all female artists. Also included were Leonore Carrington, Buffie Johnson, Frida Kahlo, Louise Nevelson, Meret Oppenheim, I. Rice Pereira, Kay Sage, Hedda Sterne, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Hazel Guggenheim, Pegeen Vail Guggenheim, Barbara Poe Levee, Alice Trumbull Mason, and others. Peggy Guggenheim, who produced the show, was said to have commented later that she should have been satisfied with 30 artists. It was her husband, Max Ernst, who was greatly attracted to Tanning's self-portrait, Birthday and suggested her for the show. He was also greatly attracted to the artist. After his initial visit, Dorothea and Ernst played chess every day for a week. Then he moved in and they stayed together until Max's death in 1976.  Palaestra | 1947 | Oil on canvas

Palaestra | 1947 | Oil on canvas

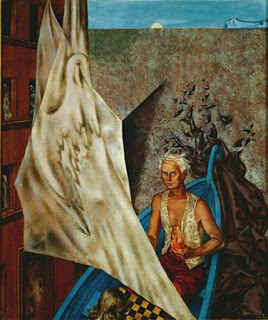

Max in a Blue Boat | 1947 | Oil on canvasMax Ernst Museum, Brühl

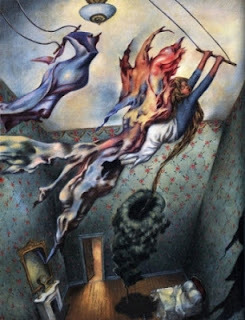

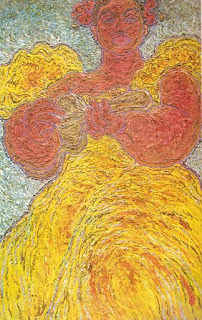

Max in a Blue Boat | 1947 | Oil on canvasMax Ernst Museum, Brühl  A Very Happy Picture | 1947 | Oil on canvasMusée National d’Art ModerneThe couple moved to Sedona, Arizona in 1946 and built a two room house. The shelter, though sturdy, lacked running water and electricity. Eventually those needs were met and kerosene lights gave way to incandescent bulbs and a well and pump supplied tap water. Even before their arrival, Tanning painted. Over the next three years she created Guardian Angels, Palaestra, Max in a Blue Boat, Maternity, A Very Happy Picture, Avatar, and others. In 1949, Dorothea and Max moved to Paris.

A Very Happy Picture | 1947 | Oil on canvasMusée National d’Art ModerneThe couple moved to Sedona, Arizona in 1946 and built a two room house. The shelter, though sturdy, lacked running water and electricity. Eventually those needs were met and kerosene lights gave way to incandescent bulbs and a well and pump supplied tap water. Even before their arrival, Tanning painted. Over the next three years she created Guardian Angels, Palaestra, Max in a Blue Boat, Maternity, A Very Happy Picture, Avatar, and others. In 1949, Dorothea and Max moved to Paris.I think I’ve been a renaissance man—if he could have been a woman.

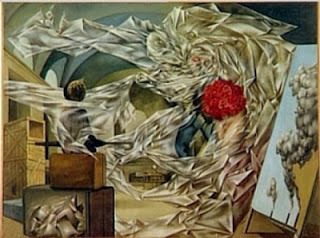

Le Mal Oublié (The Ill Forgotten)1955 | Oil on canvasIn the mid 50s, although the surrealist movement continued, Tanning was once again ready for change. That change came in her painting. In Between Lives she wrote that "Around 1955, my canvases literally splintered. Their colors came out of the closet, you might say, to open the rectangles to a different light. They were prismatic surfaces where I veiled, suggested, and floated my persistent icons and preoccupations, in another of the thousand ways of saying the same things"

Le Mal Oublié (The Ill Forgotten)1955 | Oil on canvasIn the mid 50s, although the surrealist movement continued, Tanning was once again ready for change. That change came in her painting. In Between Lives she wrote that "Around 1955, my canvases literally splintered. Their colors came out of the closet, you might say, to open the rectangles to a different light. They were prismatic surfaces where I veiled, suggested, and floated my persistent icons and preoccupations, in another of the thousand ways of saying the same things"  Naufrage en rose (Shipwreck in Pink)1958 | Oil on canvas

Naufrage en rose (Shipwreck in Pink)1958 | Oil on canvas

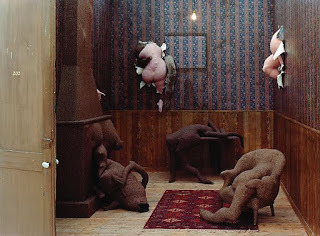

Insomnies (Insomnias)1957 | Oil on canvasModerna Museet, StockholmBy the late 60s and into the early 70s, Tanning experimented with soft sculptures. Of one called Canapé en temps de pluie (Sofa on a Rainy Day) she said the work "...was, more than anything, a challenge to myself, a bet that I made with myself, and only me, that I would give real physical life to a bunch of tweeds and stuffing." Dorothea Tanning: Birthday and Beyond. Exhibition brochure. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2000.

Insomnies (Insomnias)1957 | Oil on canvasModerna Museet, StockholmBy the late 60s and into the early 70s, Tanning experimented with soft sculptures. Of one called Canapé en temps de pluie (Sofa on a Rainy Day) she said the work "...was, more than anything, a challenge to myself, a bet that I made with myself, and only me, that I would give real physical life to a bunch of tweeds and stuffing." Dorothea Tanning: Birthday and Beyond. Exhibition brochure. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2000.  Hôtel du Pavot, Chambre 202 (Poppy Hotel, Room 202 Fabric, wool, synthetic fur, cardboard, and Ping-Pong ballsMusée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou

Hôtel du Pavot, Chambre 202 (Poppy Hotel, Room 202 Fabric, wool, synthetic fur, cardboard, and Ping-Pong ballsMusée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou

Convolotus alchemelia (Quiet-willow window)

Convolotus alchemelia (Quiet-willow window)1998 | Oil on canvas | 56 x 66 in.After the death of Max Ernst in 1976, Tanning felt unable to paint. Her good friend, poet James Merrill, convinced her to work. He “more than anyone at that point of my life, made me realize that living was still wonderful even though I felt that my loss, Max, had left nothing but ashes.” In 1979 she returned to New York and painted for the next 20 years, publishing her first memoir, Birthday, in 1986.

In 1998 Dorothea did a series of twelve paintings that were published along with poetry by various writers whose work she admired, Adrienne Rich, John Ashbery, James Merrill, and others, in Another Language of Flowers. "A new hybrid of flower has always occasioned celebration by gardeners and amateur botanists everywhere. It is hard to think of anything more innocently irresistible than a flower, new or familiar, while an imagined one must surely bring a special frisson of excitement. Or so I thought, on the day in June when such a flower grew in my mind's eye and demanded to be painted. Once begun, the experiment widened into an entire garden. They bloomed all at once, as if to race with a short summer, and soon there were twelve canvases of twelve flowers waiting to be named. Dorothea Tanning: Birthday and Beyond. Exhibition brochure. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2000.

One would think that was a large enough portfolio for anyone. Not so for Dorothea Tanning. In the late 1990s, she began writing poetry and published her first collection, A Table of Content in 2004, and her second, Coming to That, in 2011. Reading her poetry, actually any of her writing, is much like looking at her paintings. She presents life from a different perspective, a little unsettling, but familiar and at times, amusing. If you find yourself on public transportation in New York, you could be inspired by this Tanning poem posted in subway cars for the Poetry in Motion program.

This is a small sample of the prolific artist, and I have to admit, it was difficult to choose favorites. Why did we not hear more about this remarkable woman? Why is she not as well known as those with whom she lived and worked? I can't answer that, but I can share. Visit the vast collection of work by Dorothea Tanning at her website and enjoy.Graduation

He told us, with the years, you will come

to love the world.

And we sat there with our souls in our laps,

and comforted them. Dorothea Tanning 1910-2012

Touristes de Prague III (Tourists of Prague III)1961 | Oil on canvas | The Menil Collection, Houston

Touristes de Prague III (Tourists of Prague III)1961 | Oil on canvas | The Menil Collection, HoustonArt has always been the raft onto which we climb to save our sanity. I don’t see a different purpose for it now.

June 1, 2012

Colette

For many, the name Colette conjures vague images of a French dancer with a questionable reputation...and didn't she do some writing? In the U.S. she is best known for Gigi, published in 1945 when she was seventy-two. There were over fifty novels written before that.

For many, the name Colette conjures vague images of a French dancer with a questionable reputation...and didn't she do some writing? In the U.S. she is best known for Gigi, published in 1945 when she was seventy-two. There were over fifty novels written before that.Colette was born Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette on January 28, 1873 in Saint-Sauveur-en-Puisaye, France. Her father, Jules-Joseph Colette, retired from the army and worked as a tax collector. Her mother, Adele Eugenia Sidonie Landois, Sido—a wise, down-to-earth Maman—became known to many through Colette's stories, My Mother's House and Sido.

Her first books, the Claudine series, were published between 1900 and 1903 under her husband Henri Gauthier-Villarspen's pen name "Willy". She was 20 when she married Henri, 14 years her senior. It was said that he locked her in a room, refusing to release her until she'd written a few tantalizing chapters of her escapades at boarding school. There were five books in the series from which came a line of Claudine products. Everything from cigarettes and perfume to chocolates and cosmetics made Gauthier-Villars a wealthy man. Things did not go as well for Colette who divorced him in 1906 and supported herself as a dancer and a mime in Parisian music halls.

Her first books, the Claudine series, were published between 1900 and 1903 under her husband Henri Gauthier-Villarspen's pen name "Willy". She was 20 when she married Henri, 14 years her senior. It was said that he locked her in a room, refusing to release her until she'd written a few tantalizing chapters of her escapades at boarding school. There were five books in the series from which came a line of Claudine products. Everything from cigarettes and perfume to chocolates and cosmetics made Gauthier-Villars a wealthy man. Things did not go as well for Colette who divorced him in 1906 and supported herself as a dancer and a mime in Parisian music halls.You will do foolish things, but do them with enthusiasm.

She reportedly pained over every word, and yet her writing flows sensually whether the topic is food, a garden, or a lover. It is, no doubt, that sensuality that stokes her reputation. At a time when women were told to learn to write like men, Colette was unapologetic about her gender or the passion of her writing. She wrote with the same intensity that she lived, and she lived a remarkable life. She was equally adept at stunning descriptive prose as she was at sometimes vicious humor. Her words entice you to love and hate as she does, yearn for a visit to her childhood home, learn French, or join a group of friends for a long dinner instead of the brief encounters so common these days.

Her efforts did not go unacknowledged. She was the first woman admitted to the prestigious Goncourt Academy and in 1953 was elected to the Legion of Honour. She died in 1954. I've done a great deal of reading by and about Colette, but she was complex, and it is difficult to judge from her writings what is autobiographical and what is fiction. What I do know is that her writing engages me on many levels. I'll let you judge for yourself.

Bella Vista

The night was murmurous and warmer than the day. Three or four lighted windows, the clouded sky patched here and there with stars, the cry of some night bird over this unfamiliar place made my throat tighten with anguish. It was an anguish without depth; a longing to weep which I could master as soon as I felt it rise. I was glad of it because it proved that I could still savor the special taste of loneliness.

Bygone Spring

Everything rushes onward, and I stay where I am. Do I not already feel more pleasure in comparing this spring with others that are past than in welcoming it? The torpor is blissful enough, but too aware of its own weight. And though my ecstasy is genuine and spontaneous, it no longer finds expression. "Oh, look at those yellow cowslips! And the soapwort! And the unicorn tips of the lords and ladies are showing!..." But the cowslip, that wild primula, is a humble flower, and how can the uncertain mauve of the watery soapwort compare with a glowing peach tree? Its value for me lies in the stream that watered it between my tenth and fifteenth years. The slender cowslip, all stalk and rudimentary in blossom, still clings by a frail root to the meadow where I used to gather hundreds to straddle them along a string and then tie them into round balls, cool projectiles that struck the cheek like a rough wet kiss.

October

My thoughts turn to the house, to the fire and the lamp; there are books and cushions and a bunch of dahlias the color of dark blood; in these short afternoons, when the early evenings turn the bay windows blue, decidedly it's time to be indoors. Already on the tops of the walls on the still-warm slates of the roofs, there appear with tails like plumes, wary ears, cautious paws, and arrogant eyes, those new masters of our gardens, the cats.

A long black tom keeps continual watch on the roof of the empty kennel; and the gentle night, blue with motionless mist that smells of kitchen gardens and the smoke of green wood, is peopled with little velvety phantoms. Claws lacerate the barks of trees, and a feline voice, low and hoarse, begins a thrilling lament that never ends.

My Mother's House

My Mother's House

It was not until one morning when I found the kitchen unwarmed and the blue enamel saucepan hanging on the wall, that I felt my mother's end to be near. Her illness knew many respites, during which the fire flared up again on the hearth, and the smell of fresh bread and melting chocolate stole under the door together with the cat's impatient paw. These respites were periods of unexpected alarms. My mother and the big walnut cupboard were discovered together in a heap at the foot of the stairs, she having determined to transport it in secret from the upper landing to the ground floor. Whereupon my elder brother insisted that my mother should keep still and that an old servant should sleep in the little house. But how could an old servant prevail against a vital energy so youthful and mischievous that it contrived to tempt and lead astray a body already half fettered by death? My brother, returning before sunrise from attending a distant patient, one day caught my mother red-handed in the most wanton of crimes. Dressed in her nightgown, but wearing heavy gardening sabots, her little grey septuagenarian's plait of hair turning up like a scorpion's tail on the nape of her neck, one foot firmly planted on the crosspiece of the beech trestle, her back bent in the attitude of the expert jobber, my mother, rejuvenated by an indescribable expression of guilty enjoyment, in defiance of all her promises and of the freezing morning dew, was sawing logs in her own yard.

The Vagabond

Come now, this won't do. I'm too clear-sighted this evening, and if I don't pull myself together my dancing will suffer for it. I dance and dance. A beautiful serpent coils itself along the Persian carpet, an Egyptian amphora tilts forward, pouring forth a cascade of perfumed hair, a blue and stormy cloud rises and floats away, a feline beast springs forwards, then recoils, a sphinx, the color of pale sand, reclines at full length, propped on its elbows with hollowed back and straining breasts. I have recovered myself and forget nothing. Do these people really exist, I ask myself? No, they don't. The only real things are dancing, light, freedom, and music. Nothing is real except making rhythm of one's thought and translating it into beautiful gestures. Is not the mere swaying of my back, free from any constraint, an insult to those bodies cramped by their long corsets, and enfeebled by a fashion which insists that they should be thin?"

The Ripening Seed

All that could be seen through the window was the August tide, bringing rain in its wake. The earth came to an abrupt end out there, at the edge of the sand hills. One more squall, one more upheaval of the great grey field furrowed with parallel ridges of foam, and the house would surely float away like the ark…but Phil and Vinca knew the August seas of old and their monotonous thunder, as well as the wild, white-capped seas of September. They knew that this corner of a sandy field would remain impassable, and all through their childhood they had scoffed at the frothy foam-scuds that danced powerlessly up to the edge of man's dominion.

The Pure and the Impure

Voluptuaries, consumed by their senses, always begin by flinging themselves with a great display of frenzy into an abyss. But they survive, they come to the surface again. And they develop a routine of the abyss: 'It's four o clock. At five I have my abyss...'

Sit down and put down everything that comes into your head and then you're a writer. But an author is one who can judge his own stuff's worth, without pity, and destroy most of it.

Cheri

Lea, leaning on her elbow, looks at him. In the merciful half-light, she shows what a pretty fifty-year-old woman, well cared for and in good health, can show: the bright complexion, somewhat ruddy and a bit weathered, of a natural blonde, shapely, solid shoulders, and celebrated blue eyes which have kept their thick chestnut lashes. But she is now a redhead, because of her hair, which is turning gray.

She loves to chat in bed, almost invisible, while her magnificent arms and expressive hands comment on her wise words. Nearing the end of a successful career as a sedate courtesan, she is neither sad nor spiteful. She keeps the date of her birth a secret, but willingly admits, as she settles her calm gaze on Cheri, that she is approaching the age when one is permitted little comforts...

Cheri was made into a film in 2009

I write with my senses, with my body...all my flesh has a soul.

May 1, 2012

The First Fictional Women Sleuths

Today, the fictional women who fight crime and solve mysteries are PIs, attorneys, cooks, members of every branch of law enforcement and every imaginable occupation. They are old, young, married, and single, from every race and every corner of the globe. The list is long and satisfying, but this month, I present some of the earlier fictional females sleuths created by women writers when neither act was warmly welcomed.

In 1894, author Catherine Louisa Pirkis introduced the Victorian lady sleuth, Loveday Brookein The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective. Loveday, in her thirties, had been a member of the upper class until circumstances forced her to earn a living. She was unmarried, bright, and too easily bored to settle for traditional 'women's work' and became an agent at a London Detective Agency. Her boss, Ebenezer Dyer had the greatest respect for her sharp mind and deductive reasoning. At a time when Sherlock Holmes brought mysteries to the forefront, Loveday Brooke became the most popular fictional female detective of her day. Pirkis described her "in a series of negations. She was not tall, she was not short; she was not dark, she was not fair; she was neither handsome nor ugly. Her features were altogether nondescript; her one noticeable trait was a habit she had, when absorbed in thought, of dropping her eyelids over her eyes till only a line of eyeball showed, and she appeared to be looking out at the world through a slit, instead of through a window."

In 1894, author Catherine Louisa Pirkis introduced the Victorian lady sleuth, Loveday Brookein The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective. Loveday, in her thirties, had been a member of the upper class until circumstances forced her to earn a living. She was unmarried, bright, and too easily bored to settle for traditional 'women's work' and became an agent at a London Detective Agency. Her boss, Ebenezer Dyer had the greatest respect for her sharp mind and deductive reasoning. At a time when Sherlock Holmes brought mysteries to the forefront, Loveday Brooke became the most popular fictional female detective of her day. Pirkis described her "in a series of negations. She was not tall, she was not short; she was not dark, she was not fair; she was neither handsome nor ugly. Her features were altogether nondescript; her one noticeable trait was a habit she had, when absorbed in thought, of dropping her eyelids over her eyes till only a line of eyeball showed, and she appeared to be looking out at the world through a slit, instead of through a window." Free HTML copy of The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective.

It would never do for me to lose my wits in the presence of a man who had none too many of his own. —Miss Amelia Butterworth

In 1897, Anna Katharine Green introduced Amelia Butterworth in That Affair Next Door. Butterworth was the first notable spinster sleuth in fiction. She offered her not completely welcomed assistance to Green's main character, Detective Ebenezer Gryce of the New York Police. Unlike Brooke, Butterworth was financially comfortable and had little to occupy her time other than observing the comings and goings of her neighbors. It was one of those observations that involved her in a murder investigation. "I am not an inquisitive woman, but when, in the middle of a certain warm night in September, I heard a carriage draw up at the adjoining house and stop, I could not resist the temptation of leaving my bed and taking a peep through the curtains of my window."

Although the elderly spinster was seen by most as nosy, Gryce recognized her ability to spot and evaluate important details that many missed. Amelia Butterworth appeared again in Lost Man’s Lane, 1898, and The Circular Study, 1900. Some believe that Butterworth inspired Patricia Wentworth's Maud Silver, Agatha Christie's Jane Marple, Mary Roberts Rinehart's Rachel Innes, and others.

Although the elderly spinster was seen by most as nosy, Gryce recognized her ability to spot and evaluate important details that many missed. Amelia Butterworth appeared again in Lost Man’s Lane, 1898, and The Circular Study, 1900. Some believe that Butterworth inspired Patricia Wentworth's Maud Silver, Agatha Christie's Jane Marple, Mary Roberts Rinehart's Rachel Innes, and others. In 1915, Green created the first girl detective in The Golden Slipper and Other Problems for Violet Strange. The character, Violet Strange, was a wealthy young woman who took the occasional case to earn money that didn't come from her father. He was quite unaware of her investigations and she was selective about the ones she accepted. "If you have a case of subtlety without crime, one to engage my powers without depressing my spirits, I beg you to let me have it."

Download The Golden Slipper from Project Gutenberg.

It's well enough for you, Tish Carberry,

It's well enough for you, Tish Carberry, to talk about gripping a horse with your kneesIn 1908, Mary Roberts Rinehart, sometimes called 'The American Agatha Christie,' introduced Rachel Innes, a fifty something spinster heiress in The Circular Staircase. In the novel, Innes, along with her niece and nephew rent a house for a summer vacation that turns into a complex web of murder and intrigue that is eventually solved by the heroine. The book became a successful stage play called The Bat.

In 1910, Rinehart created a character to voice her feminist beliefs. Letitia (Tish) Carberry was a middle aged spinster who along with her friends Aggie and Lizzie behaved in ways unbecoming and unacceptable in women at the beginning of the 20th century. They raced cars, hunted, drove ambulances, and flew airships. Rinehart introduces Tish by explaining an unfavorable newspaper story. "So many unkind things have been said of the affair at Morris Valley that I think it best to publish a straightforward account of everything. The ill nature of the cartoon, for instance, which showed Tish in a pair of khaki trousers on her back under a racing-car was quite uncalled for. Tish did not wear the khaki trousers; she merely took them along in case of emergency. Nor was it true that Tish took Aggie along as a mechanician and brutally pushed her off the car because she was not pumping enough oil. The fact was that Aggie sneezed on a curve and fell out of the car, and would no doubt have been killed had she not been thrown into a pile of sand."

In 1914, we meet Hilda Adams, known as Miss Pinkerton, a nurse who does her fair share of sleuthing. Her detecting career begins in the story The Buckled Bag, when a patient she attends, a detective, suggests she might work for the police.

In 1914, we meet Hilda Adams, known as Miss Pinkerton, a nurse who does her fair share of sleuthing. Her detecting career begins in the story The Buckled Bag, when a patient she attends, a detective, suggests she might work for the police. All of Rinehart's female detectives are intelligent and possess the one absolutely necessary tool for people who live and work outside the box—a sense of humor.

Download The Circular Staircase at the Gutenberg ProjectDownload Tish, The Chronicle of Her Escapades and Excursions at the Gutenberg Project

Millicent Newberry, created by Jeanette Lee, appeared in three novels beginning in 1917 with The Green Jacket. Unlike many of the female detectives of the era who worked for other agencies or police departments, Millicent began working at Tom Corbin's firm, but left to start her own detective agency. She was single, older, and from a middle class background, and lived with her ailing mother and a caretaker. Along with a great interest in psychiatry, Newberry had a unique approach to taking notes. She would knit while conversing with clients and encode her notes into the stitches. In 1922 she appeared in The Mysterious Office, and in 1925 in Dead Right. The other unconventional aspect of her practice was that she decided that if the criminal deserved a second chance, she did not report her findings to the police.

The Mysterious Office on Google Books onlineThe Green Jacket on Google Books online

Patricia Wentworth introduced Miss Maud Silver in the 1928 mystery Grey Mask as a secondary character. She was, according to Wentworth, a person with "small, neat features and the sort of old-fashioned clothes that were not so much dowdy as characteristic." She was also known for quoting the Bible and Tennyson. It wasn't until 1937 in The Case is Closed when the retired governess came into her own as 'a private enquiry agent' often assisting Scotland Yard, Inspector Abbott.

Patricia Wentworth introduced Miss Maud Silver in the 1928 mystery Grey Mask as a secondary character. She was, according to Wentworth, a person with "small, neat features and the sort of old-fashioned clothes that were not so much dowdy as characteristic." She was also known for quoting the Bible and Tennyson. It wasn't until 1937 in The Case is Closed when the retired governess came into her own as 'a private enquiry agent' often assisting Scotland Yard, Inspector Abbott. In Death at the Deep End, book 20 of the 32 books in the series, Abbot described the comfort he derived from the woman. "Miss Silver, smiling at him from the other side of the hearth, her hands busy with her knitting, remained a stable point in an unsettled world. Love God, honour the Queen, keep the law, be kind, be good, think of others before you think of yourself, serve Justice, speak the truth—by this simple creed she lived. Si sic omnes!..."

Like so many of the heroines of these early stories, Silver was effective because she wasn't taken seriously. She was a professional who relied on deductive reasoning and paid little attention to smug smiles and subtle or oblique criticism of her looks or skills.

Dorothy L. Sayers introduced Miss Alexandra Katherine "Kitty" Climpson in Unnatural Death (1927). She owned a secretarial agency nicknamed the Cattery, which Lord Peter Wimsey helped to establish with an ulterior motive—to use her services in ways that often involved more investigating than filing or stenography. Kitty developed into an intelligent and resourceful member of his investigative team. It was Miss Climpson's determination and clever planning that solved the mystery in Strong Poison (1930) and saved the life of another Sayers' female character of note, Harriet Vane.

Dorothy L. Sayers introduced Miss Alexandra Katherine "Kitty" Climpson in Unnatural Death (1927). She owned a secretarial agency nicknamed the Cattery, which Lord Peter Wimsey helped to establish with an ulterior motive—to use her services in ways that often involved more investigating than filing or stenography. Kitty developed into an intelligent and resourceful member of his investigative team. It was Miss Climpson's determination and clever planning that solved the mystery in Strong Poison (1930) and saved the life of another Sayers' female character of note, Harriet Vane.Harriet Deborah Vane was a crime fiction writer who Peter met and fell in love with after she was arrested for the murder of her boyfriend. That fact that she lived with a man out of wedlock made her a criminal in the eyes of much of society, and her career as a writer of police fiction sullied her reputation further. Wimsey proposed to Vane while she was still in prison, but she refused his offer, before and after he proved her innocent. She worked with Peter on a case in the 1932 book, Have His Carcase, but it wasn't until the next Wimsey book, Gaudy Night (1935) that she accepted his proposal. The couple married in Busman's Honeymoon (1937). Sayers claimed to have introduced Harriet Vane to marry off Lord Wimsey and end the series, but the couple became such a hit that she continued their relationship and their characters with even more passion. Gaudy Night is considered by some as the first feminist mystery novel, and Sayers did indeed comment on the growing restrictions on women in Nazi Germany.

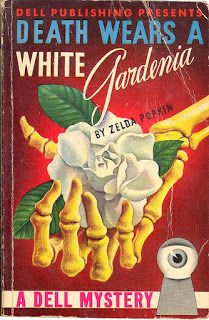

In 1938, Zelda Popkin introduced Mary Carner, considered the first modern female detective, in Death Wears a White Gardenia. Carner was a member of the security staff of a department store in New York City. According to Popkin, "Mary looked like year before last's debutante, last June's bride, this year's young matron. Prospective shoplifters, hesitating before a haul, never guessed that the pretty, well-groomed young woman in the oxford gray suit and kolinsky scarf, standing beside them at the counter, was far more interested in the behavior of their nimble fingers than in the quality of the step-ins, marked down from five-ninety-eight to three and a half."

In 1938, Zelda Popkin introduced Mary Carner, considered the first modern female detective, in Death Wears a White Gardenia. Carner was a member of the security staff of a department store in New York City. According to Popkin, "Mary looked like year before last's debutante, last June's bride, this year's young matron. Prospective shoplifters, hesitating before a haul, never guessed that the pretty, well-groomed young woman in the oxford gray suit and kolinsky scarf, standing beside them at the counter, was far more interested in the behavior of their nimble fingers than in the quality of the step-ins, marked down from five-ninety-eight to three and a half."I had not read this series, but after reading the Time Off for Murder (1943) preview on Google books, have added them to my 'to read' pile. The series: Murder in the Mist,1940; Dead Man’s Gift, 1941; and No Crime for a Lady, 1942.

“You do not conceive a novel as easily as you conceive a child, nor even half as easily as you create nonfiction work. A journalist amasses facts, anecdotes and interviews with top brass. Enough of these add up to a book. A novelist demands quite different things. He has to find himself in his materials, to know for sure how he would feel and act and the events he writes about. In addition, he requires a catalyst—a person, idea, or emotion which coalesces his ingredients and makes them jell into a solid purpose.” ―Zelda Popkin

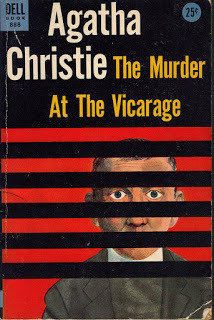

And last, but not least, the most familiar member of our female sleuth club, Miss Jane Marple. Agatha Christie introduced the well meaning meddler in 1926 in a magazine piece called The Tuesday Night Club. The story eventually became the first chapter of the 1932 book The Thirteen Problems, but it was in 1930, in The Murder at the Vicarage, where we first visited Jane in her home town of St. Mary Mead. Dame Christie revealed in her autobiography that the inspiration for Marple: "the sort of old lady who would have been rather like some of my grandmother's Ealing cronies—old ladies whom I have met in so many villages where I have gone to stay as a girl"

And last, but not least, the most familiar member of our female sleuth club, Miss Jane Marple. Agatha Christie introduced the well meaning meddler in 1926 in a magazine piece called The Tuesday Night Club. The story eventually became the first chapter of the 1932 book The Thirteen Problems, but it was in 1930, in The Murder at the Vicarage, where we first visited Jane in her home town of St. Mary Mead. Dame Christie revealed in her autobiography that the inspiration for Marple: "the sort of old lady who would have been rather like some of my grandmother's Ealing cronies—old ladies whom I have met in so many villages where I have gone to stay as a girl"We spend our lives solving puzzles, problems, and mysteries of various kinds. It is no surprise that the intuitive abilities to which women readily turn, offer some of the best solutions.

As you may have guessed, this post was a pleasure to research and share. Because of these women, (and others there wasn't room to list) the very popular category of 'female sleuth' continues to entertain and delight readers around the world. That is great inspiration for someone who has only been writing mysteries since 2004. I am humbled, inspired, and anxious to continue learning from these remarkable voices.

March 1, 2012

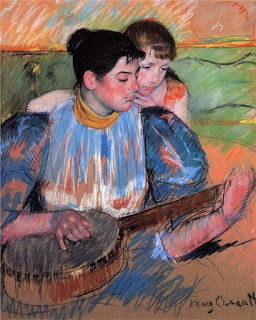

Mary Cassatt

Portrait of Mary Cassatt Holding Cards

Portrait of Mary Cassatt Holding CardsEdgar Degas c. 1876–1878 oil on canvas

It was during my research for this post that the current round of attacks on women came to the forefront, reminding me that the struggle is an old one. The Women's Rights Movement in the United States began at a convention in Seneca Falls, New York in 1848. Sixty-eight women and thirty-two men adopted resolutions calling for equal treatment under the law and voting rights for women. Mary Cassatt was four, but in a short time, her rebellion against societal and artistic convention would help redefine the role of women. What an immense loss to the art world had she not been 'allowed' to paint.

Born on May 22, 1844 in Allegheny City, Pennsylvania, Mary's well-to-do family believed travel was an important part of a child's education. Perhaps it was this early exposure to Europe's abundant art resources that prompted her to become an artist. Or perhaps the limited options available to wealthy young women of her time compelled her to enroll in the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. The choice to have a career rather than a family was her first challenge. The decision to participate in a male dominated field, the second.

Spanish Dancer Lace Mantilla

Spanish Dancer Lace Mantilla 1873 Mary Cassatt oil on canvas

Smithsonian American Art MuseumI can only imagine the prejudice she faced. My own, much less brutal experience came in 1970 when I began studying graphic arts. I was stunned to hear one of our instructors question the women in the class as to why they even bothered. According to him, Commercial Art, (as it was called at the time), was a male occupation and women should be home…well, you know the rest. Needless to say, I continued doing graphics, and luckily for all of us, Mary Cassatt ignored critics and continued painting. It is interesting to note that she studied at the Academy from 1861 to 1865, the Civil War years.

Two Women Throwing Flowers

Two Women Throwing FlowersDuring Carnival

Mary Cassatt oil on canvas 1872In 1866, she further sullied her reputation by moving to Paris, considered the center of the art world. To many conservative Americans, it was a city of sin. Although enrolled in private lessons, she felt stifled and spent most of her time in museums studying and copying the Old Masters. The beginning of the Franco Prussian War in 1870 sent her, unwillingly, back to the United States where her artistic temperament was less tolerated. For sixteen months, she received no support from her family beyond room and board, and had no money to buy art supplies. What was worse, America, not yet a nation known for collections of fine art, offered little to study. She struggled to mount exhibitions and sell previous works to return to Europe. In 1871 Cassatt managed to show two paintings, first in New York and then Chicago, only to have them lost in the flames that destroyed the great Midwestern city.

A Corner of the Loge (In the Box)

A Corner of the Loge (In the Box)Mary Cassatt 1879 Oil on canvas

Private collectionIronically, it was the Archbishop of Pittsburgh who rescued the artist by commissioning her to copy paintings of Antonio Allegri da Correggio in Parma, Italy. She was beside herself with joy, not only to be painting again, but to savor the abundance of art treasures. Her return was a triumph, and the Salon de Paris exhibited her paintings from 1872–1874.

In 1874 she saw her first impressionist pieces at a show by Edgar Degas. Years later she wrote to her friend and patron, Louisine Havemeyer, “How well I remember, nearly forty years ago, seeing for the first time Degas’ pastels in the window of a picture dealer on the Boulevard Haussmann. I used to go and flatten my nose against that window and absorb all I could of his art. It changed my life. I saw art then as I wanted to see it.” That same year, Degas saw her work Ida, at the Salon and invited her to the Société Anonyme des Artistes, often called the Independents. The rest of the art world called them the Impressionists. The Salon jurists, often criticized for their conventional tastes and constraints on artists, made her decision easy. Only three women were invited to join the Independents, and only one American, Mary Cassatt. She showed in 1879, 1880, 1881, and in the group's final show in 1886.

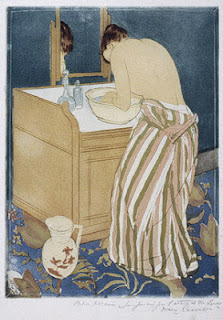

Woman Bathing (La Toilette)

Woman Bathing (La Toilette)Mary Cassatt 1890-1891

Drypoint and aquatint from three platesHer success continued until in late 1881 she had to return home to care for her sister and mother who were both ill. Although her mother recovered, her sister Lydia, who had battled illness throughout her life, did not. The usually prolific Cassatt produced little over the next years, but began advising Havemeyer and other American friends and family to collect impressionist art. In 1886, she entered two of her paintings in the first impressionist exhibition in the United States.

The Boating Party,

The Boating Party, Mary Cassatt 1893/1894 oil on canvas