Mal Warwick's Blog, page 91

January 8, 2021

The year 2020 in review

This is for the record. You may not be the least bit interested, but I am. So, read on or not. In this post I’ll sum up what I’ve learned about the performance of this site in the past calendar year. And I must say I found a few surprises as I pondered the year 2020 in review.

What visitors read on this site

In the course of 2020, I posted a total of 198 individual book reviews, representing the following categories:

52 nonfiction books (including history, biography, politics, science)61 mysteries and thrillers (notably detective novels, spy thrillers, police procedurals, courtroom dramas) 52 science fiction books (particularly hard, science-based fiction)33 trade fiction (especially historical fiction and humor)

Far and away the most popular posts on this site in 2020 (and for years before that) were what I term “grouped reviews” rather than reviews of individual titles. You might prefer to call them “lists.” The five most popular in 2020 were:

The 10 best novels about World War IIThe 10 top espionage novels reviewed on this site5 top nonfiction books about World War II30 outstanding detective series from around the world20 top nonfiction books about history

If by some chance you visited one or another of these posts awhile ago, you might check it out again. I regularly update all these (and many other posts) as I continue to read books in the same categories.

Who were those readers?

In 2020, this site was visited by 269,000 readers from 221 countries. Now, you may not have known there are that many countries in the whole world. In fact, that many may not even exist. After all, the United Nations has admitted only 193 member states, and there are just two other countries that are UN observers. If you hunt and peck on Google, you’ll find claims that the total number is 196, 197, 201, or as many as 215. So, I don’t know where or how Google turned up 221 countries in its Analytics report. But there it is. Those extra countries probably represented wishful thinking.

Of those 221 countries, not all of which may be real, the five that brought the most visitors to this site were as follows:

USAUKCanadaIndiaAustralia

No surprise there. I’m American, and I speak and write English (at least far better than the other languages I’ve studied over the years).

Drilling down a little further, I learned that the top three referrals to this site were Medium, Facebook, and Berkeleyside. The last of these is no surprise, either, since I live in Berkeley. And when my reviews involve someone living in Berkeley, they’re reposted on that site.

According to Google Analytics once again, 55 percent of my readers in 2020 were male. An equal percentage were between the ages of 25 and 34. And I must admit that surprises me: I left those ages behind about a half-century ago. But it’s nice to know. I’ve long humored myself thinking I have a few things to teach young people.

So, that’s the year 2020 in review. Remember, you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.

The post The year 2020 in review appeared first on Mal Warwick Blog on Books.

January 6, 2021

An absorbing biography of Moe Berg, baseball player and WWII spy

Moe Berg (1902-72) was one of the most confounding men who ever donned a glove in Major League Baseball. He graduated magna cum laude from Princeton, earned a law degree from Columbia, and studied linguistics at the Sorbonne. Berg had a fair command of six foreign languages and could understand many more. He pored through up to ten daily newspapers and wore one of eight identical black suits every day. And during World War II, after a nineteen-year career as a catcher for a succession of American League teams, he enlisted in the OSS and pulled off one of the agency’s most spectacular espionage coups. But nearly all this information has come out elsewhere. If that’s all there were to the story, a biography of Moe Berg wouldn’t be worth reading.

Yet, there was much more to the man. Beyond the superficial facts, no one knew him. He never married and had no close friends. Even his brother and sister found him mysterious. Happily, Nicholas Dawidoff dug deeply into the man’s past and revealed what few knew about him. His biography of Moe Berg, The Catcher Was a Spy, is outstanding.

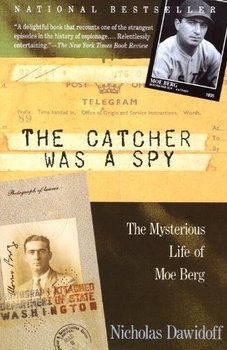

The Catcher Was a Spy: The Mysterious Life of Moe Berg by Nicholas Dawidoff (1994) 437 pages @@@@ (4 out of 5)

Morris “Moe” Berg played for a succession of professional baseball teams, most notably the Boston Red Sox and the Washington Senators. Image: New York Times

Morris “Moe” Berg played for a succession of professional baseball teams, most notably the Boston Red Sox and the Washington Senators. Image: New York Times A life story in four stages

Dawidoff’s biography of Moe Berg is organized conventionally, relating the story of the man’s curious life in roughly chronological order.

Early life as the son of immigrants

Morris, known as Moe from the start, was the youngest of three children of hard-working Ukrainian Jewish immigrants who had moved to a Christian neighborhood in Newark, New Jersey. Berg was a prodigy of sorts, learning to read almost from the time he started talking. He was an outstanding student and gained admission to Princeton. There, once again a Jew isolated among Christians, he proved himself to be a star student. He studied philology and phonetics and picked up numerous languages.

But Berg gained fame at Princeton as a shortstop on the baseball diamond. He was “the best baseball player in the school’s history.” The press took notice, but his father didn’t. In fact, throughout Berg’s life, the old man didn’t attend a single one of the baseball games Berg played in. Bernard Berg was disdainful of sports and pressured his son to leave baseball to become a lawyer.

19-year baseball career

Berg’s standout performance at Princeton gained him a berth with the Brooklyn Dodgers, then known as the Robins. During the nineteen seasons that ensued, he played for a succession of professional teams, most of the time as a catcher. Although he demonstrated early flashes of stardom, those episodes were brief and rare. Most of the time he was a benchwarmer who rarely ventured onto the field.

“The brainiest man in baseball”

Moe Berg was “The brainiest man in baseball.” As his obituary in the New York Times noted, “‘He can speak 10 languages,’ his friends used to joke, ‘but he can’t hit in any of them.'” However, managers kept him on the roster because he boosted team morale as a friend and sometime mentor to other players, enthralling them with stories about his adventures in Europe, Japan, and elsewhere. And it surely didn’t hurt that he was a magnet for sportswriters, too. “Every day Berg sat in the dugout before the game and told stories to crowds of reporters.” The press couldn’t get enough of “Professor Berg.” In fact, as this perceptive biography of Moe Berg makes clear, it was the press, and especially the New York Times sports columnist John Kieran, who “created the public Berg.”

“A life of abiding strangeness”

“There were crumbs of truth in every story,” Dawidoff notes, “yet the jolly world of Professor Berg was false at the center. This was not the man, it was caricature on a grand scale. Which didn’t bother Berg. In fact, he encouraged the burlesque and guided the creation of this shimmering distortion.” The reality was starkly different. “Berg’s was a life of abiding strangeness. The secret world of Moe Berg was charming and seamy, vivid and unsettling, wonderful and sad.”

Familiarity with at least 16 languages

Berg’s command of languages was endlessly fascinating to those around him, but exaggerations abounded. Press reports variously credited him with speaking—fluently, of course—anywhere from ten to twenty-seven languages. In fact, when he applied to the OSS much later, “Berg lists his French, Spanish, and Portuguese as ‘fair,’ and his Italian, German, and Japanese as ‘slight.'” However, Dawidoff reports that “during his life he also took a passing interest in, among other languages, Russian, Polish, Mandarin, Chinese, Arabic, Old High German, and Bulgarian.” And at various points throughout this book, Dawidoff also has Berg speaking Greek and Latin and reading Sanskrit (which was not a spoken language).

War work for the OSS

Nobel laureate physicist Werner Heisenberg, who led Nazi Germany’s quest for the atomic bomb in World War II. Image: Askey Physics

Nobel laureate physicist Werner Heisenberg, who led Nazi Germany’s quest for the atomic bomb in World War II. Image: Askey PhysicsMoe Berg’s fame as a spy rests on a single encounter with the Nobel Prize-winning physicist who headed Nazi Germany’s quest for an atomic bomb. The OSS had dispatched him to Switzerland in December 1944. There, he was to attend a lecture by Werner Heisenberg and attempt to ascertain whether the Nazis were on the verge of building a bomb—or even had one already. He had been tutored in nuclear physics and devoured books on the subject in preparation—to such an extent that some physicists expressed amazement with his understanding. If Berg determined the Germans were on track to a bomb, he was to stand up in the lecture hall, pull out a revolver he’d been issued, and shoot Heisenberg.

His most famous exploit was a bust

Fortunately, there was not even a hint in the physicist’s lecture that he was even engaged in nuclear research, and Berg left the man in peace. Ironically, Heisenberg was indeed conducting research in nuclear physics. But he was struggling against scientific roadblocks and interference by Nazi functionaries. And the Allies had already received through other means abundant evidence that the Nazi atomic bomb program was floundering, years behind the Manhattan Project. But of course Berg didn’t know any of this, and nor did his handlers in the OSS.

Befriending prominent German, Swiss, and French scientists

Some of Berg’s other work for the OSS was of greater consequence for the war effort and the Allies’ postwar scientific research efforts. Berg was detailed to the Allies’ Alsos Mission, which had been organized primarily to dig up information about the Nazi bomb project but secondarily to connect with Axis scientists, learn whether they were developing biological or chemical weapons, secure Nazi supplies of uranium and heavy water, and begin the process of enticing the best scientists to move to Britain or the United States. Berg clashed with Colonel Boris Pash, the commander of the Alsos Mission, and operated independently as a consequence. But it was his efforts befriending prominent German, Swiss, and French scientists that helped lure them westward as the war wound down. Pash and his team were less successful.

Life after World War II

Berg lived for twenty-five years after he left the OSS in 1947. Although he doggedly hid the information from everyone outside his family, he lived with his brother “Dr. Sam” from 1947 to 1964 and then, after Dr. Sam kicked him out, with his spinster sister Ethel until his death in 1972. In succession, his two siblings housed, fed, and dressed him and gave him money for his nearly incessant travel and incidentals. But neither of them could figure him out. At one point during the war, “Berg [had] brought Chico Marx along for dinner [with his brother] one evening. Sam hadn’t known that his brother socialized with the Marx brothers, but Berg wasn’t explaining that, either.” In fact, Berg was a celebrity of sorts and connected with a great many luminaries of the era. He even spent a couple of lively afternoons on a visit to Princeton talking about baseball and relativity with Albert Einstein. It seems he could speak about nearly any subject at length and in detail—and in several languages.

Berg was not among the one out of ten OSS employees asked to join the new CIA in 1947. Under wartime conditions and Bill Donovan‘s undisciplined management, the OSS had been a freewheeling operation that tolerated Berg’s eccentricities and his occasional disappearances. The CIA would not. Apart from a few brief stretches when the agency later hired him on a contract basis, and for other short periods when friends employed him as a way to support him, he never worked for the rest of his life.

What might a psychiatrist say about this man’s life?

At some ill-defined point, eccentricity crosses the line into mental illness. I’m no psychiatrist—my brother is the shrink in the family—but it seems clear to me that Moe Berg was ill for a great many years. Dawidoff doesn’t indulge the temptation to engage in psychological speculation. Like other writers, he repeatedly refers to Berg as eccentric. But surely the man’s surpassingly strange behavior over a quarter-century following the war would merit a psychiatric evaluation. You might well imagine that a biography of Moe Berg would include such speculation.

About the author

The author during a term as a Distinguished Fellow at Princeton. Image: Princeton Alumni Weekly

The author during a term as a Distinguished Fellow at Princeton. Image: Princeton Alumni WeeklyThe Catcher Was a Spy was the first of Nicholas Dawidoff‘s six nonfiction books to date, one of four about professional American sports. He is a magna cum laude graduate of Harvard and a former Guggenheim Fellow.

For additional reading

Check out Great biographies I’ve reviewed: my 10 favorites.

You might also be interested in:

5 top nonfiction books about World War II (plus many runners-up)The 10 best novels about World War II (with 30+ runners-up)7 common misconceptions about World War II

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.

The post An absorbing biography of Moe Berg, baseball player and WWII spy appeared first on Mal Warwick Blog on Books.

January 5, 2021

A deeply affecting tale of child trafficking in India today

Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line is one of the most highly praised novels of the past year. It’s the fiction debut of Deepa Anappara, an Indian journalist transposed to London. It seems likely that in other hands, the story she tells in this novel might well have wandered off into sensationalism, pathos, or worse. But Anappara deftly relates a horrific tale of child abductions in a New Delhi slum by telling it through the voices of children. It’s a virtuoso performance, at the same time both deeply affecting and revealing. The book lays bare the harsh reality of child trafficking in India today more poignantly and more memorably than any journalistic account.

Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line by Deepa Anappara (2020) 345 pages @@@@@ (5 out of 5)

An all-too-typical slum settlement in New Delhi like the basti of the novel.

An all-too-typical slum settlement in New Delhi like the basti of the novel. Image: The Indian Express

A nine-year-old boy tells the tale

The protagonist of this novel is nine-year-old Jai, a reluctant schoolboy who lives with his parents and his big sister, Runu, in a one-room home we would consider a shack. Their basti (neighborhood) is located adjacent to several high-rise luxury towers and not far from the Purple Line of the Delhi Metro. Jai is a devotee of cop shows on TV, and when a schoolmate named Bahadur goes missing, he attempts to enlist two of his friends to join him as detectives. Pari is a girl who is one of the school’s top students and is far smarter than Jai. Faiz, who is Muslim, is convinced that djinns (ghouls) have snatched Bahadur and is terrified of crossing them. And he won’t let Jai boss him around.

Police indifference to child trafficking in India today

Local police refuse to investigate, even when the boy’s mother bribes the senior officer. They insist that he simply ran off and will soon return. But Jai and Pari set out to learn what happened to Bahadur. Their search takes them far and wide and exposes them to the ever-present dangers of India’s densely crowded capital. Along the way they have a close encounter with child traffickers, spend time with a gang of resourceful street children, and witness tension on the verge of open violence between Hindus and Muslims in the basti.

A microscopic view of the nationalism and authoritarianism driving India today

Anappara adroitly conjures up the troubling outcome of Narendra Modi‘s increasingly authoritarian and nationalistic policies. There is a great deal of good in India, and hundreds of millions live rewarding lives, but they’re not portrayed in this novel. Instead, the book brings a microscope to bear on what so many of India’s poor experience on a daily basis. Violence-prone anti-Muslim demonstrations by Modi’s followers. Ineffectual and indifferent public school teachers. The petty corruption of the local police. Senior officials who share the proceeds of criminal enterprises. And among the worst of those crimes is child trafficking, which is all too common in India today. According to a report by the country’s National Human Rights Commission, 40,000 children are abducted each year and sent into slavery as servants, factory workers, or prostitutes. In the people of Jai’s basti, Anappara brings that reality home.

About the author

Deepa Anappara was born in Kerala in southwestern India and worked as a journalist in India for eleven years. Her reports on the impact of poverty and religious violence on the education of children won numerous awards. Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line is her first novel. She now lives in London.

For further reading

Check out 25 good books about India, past and present and especially Behind the Beautiful Forevers: Life, Death, and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity by Katherine Boo (A searing look at poverty in India that reads like a novel).

You might also enjoy my posts:

Top 10 mystery and thriller series;20 excellent standalone mysteries and thrillers;5 top novels about private detectives; andTwo dozen outstanding detective series from around the world.

For an abundance of great mystery stories, go to Top 20 suspenseful detective novels (plus 200 more). And if you’re looking for exciting historical novels, check out Top 10 historical mysteries and thrillers reviewed here (plus 100 others).

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.

The post A deeply affecting tale of child trafficking in India today appeared first on Mal Warwick Blog on Books.

January 4, 2021

Journey to a newly discovered planet far out from the sun

Four humans and a cleaning robot with a mind of its own are on their way in a stolen spaceship to a newly discovered planet beyond the orbit of Neptune. Amphitrite, the title of this book as well as the new planet’s name, is the entertaining story of why they’re on their way and what happens when they get there. This is hard science fiction from the fertile mind of astrophysicist Brandon Q. Morris. So, as unlikely as some of the events and circumstances might appear, there’s logic in them. And reading this novel you might end up learning a few new things about the solar system.

Amphitrite (Black Planet #1) Brandon Q. Morris (2020) 344 pages @@@@ (4 out of 5)

In school we learn about the sun and the eight major planets. But the solar system is much, much bigger than that. Most of the comets we see originate in the Oort Cloud, which extends as much as 2,500 times as far from the sun as the outermost planet, Neptune.

In school we learn about the sun and the eight major planets. But the solar system is much, much bigger than that. Most of the comets we see originate in the Oort Cloud, which extends as much as 2,500 times as far from the sun as the outermost planet, Neptune.A murder, a hijacking, and a race for freedom

It’s the year 2078. Juri is a miner, German despite his Russian name. He’s part of a small crew exploring the asteroid Hektor. His Bulgarian colleague, Grigori, is obnoxious but his exasperating behavior always seems to stop just this side of truly dangerous. However, when Grigori attempts to rape Denise, the small company’s pretty French chemist, Juri loses it. Carried away with rage, he chokes Grigori to death. Now Juri is certain their by-the-book boss, Chen, will ship him off to prison and possible execution in the Chinese penal system. To avoid that unpleasant fate, he knows he has to get off Hektor and disappear. Along with two of his colleagues, Denise and a Russian woman named Irina, Juri hijacks a visiting spaceship, the Ganymede Explorer.

On board, they discover they’re not alone. The ship’s captain, an officer of Turkish origin in the European Space Agency named Meltem, has been sleeping in her cabin rather than in the cramped mining settlement. And a small cleaning robot named Oscar turns up, too. Oscar resembles a Roomba with a long extendable arm that ends in digits containing an array of tools. And Oscar can talk. Oh, and you can’t trust Oscar, either. It lies.

A seven-month journey to a newly discovered planet

Together, this motley crew heads off into space. They have no destination except a desire to go where no one will think to look for them. Then a brilliant hacker they contact helps them identify a previously undiscovered planet. She names it Amphitrite. And after an eventful seven-month journey to the farthest reaches of the solar system, they arrive at the new planet. At which point the dangers they encountered along the way fade into insignificance in the face of what the black planet has in store for them.

A phantom planet far, far from the sun

For many years astronomers have speculated that one or more planets lie far beyond the orbit of Neptune in the Kuiper Belt or the Oort Cloud. In Brandon Morris’ imagination, Amphitrite—named for Poseidon’s (Neptune’s) wife—is one such planet. Observers have failed to discover it because of its low albedo (reflectivity). It appears to be uniformly black. And it’s unusual in at least one other major way as well. The eight known planets in the solar system revolve around the sun in orbits like Earth’s through what is known as the plane of the ecliptic. Amphitrite doesn’t. Instead, the orbit of this newly discovered planet runs at a steep angle to the plane and at distances from the outermost planets at least 250 times as great from the sun. But Amphitrite—and Brandon Morris—are full of surprises, as the crew of the Ganymede Explorer discover in this novel.

About the author

Brandon Q. Morris is a physicist and space specialist. I count twenty-three novels on his website, all of them hard science fiction that displays his command of the science involved. In his blog, Morris explores some of the same questions that appear in his fiction. But expect to encounter material that’s a little more technical than the novels.

For further reading

See Good books about space travel, including both nonfiction and fiction.

For more good reading, check out:

The ultimate guide to the all-time best science fiction novels;Great sci-fi novels reviewed: my top 10 (plus 100 runners-up);Seven new science fiction authors worth reading; andThe top 10 dystopian novels reviewed here (plus dozens of others).

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.

The post Journey to a newly discovered planet far out from the sun appeared first on Mal Warwick Blog on Books.

Science fiction reviewed here in 2021

Amphitrite (Black Planet #1) Brandon Q. Morris—Journey to a newly discovered planet far out from the sun

The post Science fiction reviewed here in 2021 appeared first on Mal Warwick Blog on Books.

Nonfiction reviewed here in 2021

Mysteries and thrillers reviewed here in 2021

xx

xx

The post Mysteries and thrillers reviewed here in 2021 appeared first on Mal Warwick Blog on Books.

Trade fiction reviewed here in 2021

December 31, 2020

A gripping tale about the early American labor movement

For several decades in the mid-twentieth century, America’s middle class prospered and grew. A vigorous labor movement gained livable wages and steadily expanding benefits for millions. To some extent, labor owed its central role in the economy to the reforms of the New Deal and the social change wrought by World War II.

From an historical perspective, however, the success of trade unionism rested on the heroic efforts of labor organizers beginning late in the nineteenth century as they battled the entrenched power of the Robber Barons who dominated American industry. The better histories of the period between the Civil War and the First World War give some sense of the monumental challenges the early American labor movement faced from rich men unafraid to use the most extreme violence to protect their millions. But it takes a novelist to convey the intimate detail that makes their stories truly memorable—as Jess Walter has done so brilliantly in The Cold Millions.

The Cold Millions by Jess Walter (2020) 351 pages @@@@@ (5 out of 5)

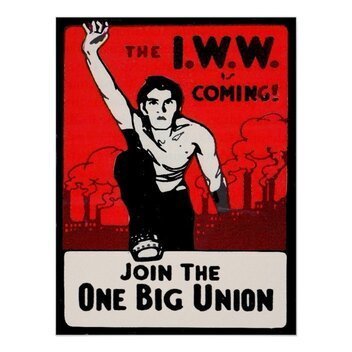

The IWW snared headlines across America in its dangerous efforts to build a militant labor movement.

The IWW snared headlines across America in its dangerous efforts to build a militant labor movement.The story in a nutshell

The Cold Millions opens in 1909 in Spokane, Washington, then a bustling frontier city and one of the nation’s most active centers of labor organizing. Gregory (“Gig”) Dolan, a laborer, has joined the IWW (Industrial Workers of the World) in a protest against an anti-union ordinance outlawing “soapboxing.” Gig is among the five hundred men rounded up and jailed in a protest against the law. Unfortunately, his sixteen-year-old brother, Ryan (“Ry”), has defied Gig’s demand he stay away and is thrown in jail, too.

Once Ry gains his release from jail as a minor through the clever arguments of an IWW attorney, he sets out to gain Gig’s freedom as well. He tags along with the famous young IWW organizer, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, and joins her on a fundraising trip around the region. Both are teenagers; she is just nineteen, newly married, and pregnant. As they travel across the Northwest, they gain perspective on the ugly and dehumanizing conditions in which most working families then lived—and the arrogance and greed of the men who refused to recognize their demands for better wages and working conditions. The Cold Millions artfully opens a window onto the now long-forgotten work of the early American labor movement.

The historical backdrop

From its founding in 1905 until about 1920, the IWW and its predominantly socialist and anarchist members, known as Wobblies, struck terror in the hearts of the millionaires who owned the nation’s mines and factories. They struck back with often lethal violence. Regiments of Pinkerton agents and local police forces—sometimes even state militias as well—overpowered the badly overmatched Wobblies. The violence was most pronounced in the American Northwest. A cofounder, and perhaps its best-known leader, was William D. (“Big Bill”) Haywood, who often bore the brunt of the reaction. But other names grabbed headlines and unwelcome attention, too, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn most prominent among them.

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn gained fame as an organizer for the IWW early in the 20th century, cofounded the ACLU, and later chaired the Communist Party of the USA. Image: ThoughtCo

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn gained fame as an organizer for the IWW early in the 20th century, cofounded the ACLU, and later chaired the Communist Party of the USA. Image: ThoughtCoThe IWW is still in operation today, but its suppression during the First Red Scare following World War I dramatically shrank its membership rolls and its impact. As of 2005, the 100th anniversary of its founding, the IWW had around 5,000 members, compared to 13 million members in the AFL-CIO. But its central role in the early American labor movement should never be forgotten.

About the author

Spokane-based author and journalist Jess Walter has written seven novels, a collection of short stories, and a nonfiction book. He has won numerous literary awards, including the Edgar and the LA Times Book Prize and was a finalist for the National Book Award for Fiction.

For further reading

For a superb work of nonfiction that casts additional light on the labor struggle during the same period, read Rebel Cinderella: From Rags to Riches to Radical, the Epic Journey of Rose Pastor Stokes by Adam Hochschild (Early 20th-century America viewed through the life of one extraordinary woman). Stokes was Flynn’s contemporary and sometime friend.

You might also be interested in:

20 most enlightening historical novels (plus dozens of runners-up)Top 10 great popular novels reviewed on this site (plus dozens of runners-up)Top 20 popular books for understanding American history20 top nonfiction books about history plus more than 80 other good ones

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.

The post A gripping tale about the early American labor movement appeared first on Mal Warwick Blog on Books.

December 30, 2020

An investigative journalist tackles the American supermarket

If you sometimes wonder, as I do, what good civilization has done for us, consider food. For most of the 300,000 years during which homo sapiens has walked on Earth, we devoted nearly all our waking hours to finding and securing food. That began to change about 10,000 years ago with the advent of agriculture. But as late as 1900, we Americans, living in one of the world’s most industrialized countries, still allocated forty percent of our income to pay for the stuff that sustains our lives. Now the comparable figure is ten percent—and “less than 3 percent of our population produces enough food to feed us all.” But, as Benjamin Lorr relates in The Secret Life of Groceries, we pay a high price for the marvels of the American food supply chain and its finest expression, the supermarket. It’s not a pretty picture. Not pretty at all.

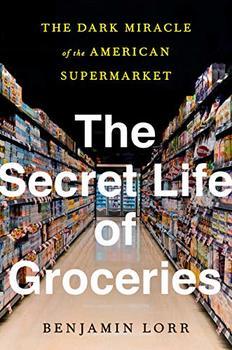

The Secret Life of Groceries: The Dark Miracle of the American Supermarket by Benjamin Lorr (2020) 336 pages @@@@ (4 out of 5)

America’s 38,000 supermarkets carried an average of 28,000 different items in 2019.

America’s 38,000 supermarkets carried an average of 28,000 different items in 2019.An in-depth picture of how food gets to our tables

This book “is the product of five years of research, hundreds of interviews, and thousands of hours tracking down and working alongside the buyers, brokers, marketers, and managers whose lives and choices define our diet.” And all that effort shows. Lorr traces the history of the American supermarket, but only briefly. Instead, he drills down into the industry as it operates today. He combines engaging human-interest reporting with in-depth investigative journalism to paint an impressionistic picture of the $683 billion industry that puts food on our tables.

Six character-driven chapters

Lorr lays out his story in six chapters, each devoted to one aspect of the grocery industry; most focus on a single individual. The cast of characters alone is instructive.

Joe Coulombe (1930-2020) founded and ran Trader Joe’s. Widely regarded as a genius, Coulombe revolutionized the American supermarket with a radically new approach to merchandising food. Lynne Ryles is a veteran of the trucking industry whose troubled experiences hauling groceries epitomize the difficulties faced by so many of the nation’s 600,000 long-haul truckers. Entrepreneur Julie Busha runs a small North Carolina company that markets a condiment called Slawsa, which is sold in more than 4,200 stores nationwide.“Walter” is a supervisor at the Bowery Whole Foods Market in Manhattan. He stays on despite the inattention to quality, shrinking benefits, and deteriorating working conditions introduced by Amazon after its 2017 purchase of the company. The author worked there on the fish counter. Kevin Kelley consults with supermarket executives about how to exit from the race to the bottom that has so many stores futilely attempting to compete only on price. Tun-Lin was for many years a slave working on a Thai ship in the Andaman Sea trawling for shrimp. The billion-dollar Thai shrimp industry accounts for “just under 10 percent of the global supply,” and the United States buys more than fifty percent of it. “NGOs estimate 17 to 60 percent of Thai shrimp includes slave labor like Tun-Lin.”

An even-handed approach, both muckraking and goggle-eyed wonder

Lorr’s approach in The Secret Life of Groceries is even-handed. The book would make muckrakers such as Upton Sinclair and Lincoln Steffens proud in its exposé of the trucking industry and the slave labor that supplies so much of our shrimp. Yet it’s impossible to read this book and emerge without a sense of wonder at how extraordinarily intricate and vast is our food supply chain. Nobody could possibly invent the American supermarket from a standing start. It’s so complicated, it seems as though it really shouldn’t work. But somehow it does. And Benjamin Lorr does yeoman’s work explaining how.

For further reading

Recently I reviewed another fascinating book about the merchandising of food: Chocolate Wars: The 150-Year Rivalry Between the World’s Greatest Chocolate Makers by Deborah Cadbury (In Chocolate Wars, what’s gone wrong with business).

You might also be interested in:

My 10 favorite books about business history (plus dozens of others)Top 20 popular books for understanding American history

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.

The post An investigative journalist tackles the American supermarket appeared first on Mal Warwick Blog on Books.