Geri Schear's Blog, page 9

April 23, 2024

Writing the Author’s Bio

For beginner writers, this can cause a lot of angst. They fret over their lack of credentials and worry if they will look like amateurs. Well, leave those fears. While credentials are hugely helpful, a well-written manuscript and on-point supporting documentation, like your author’s bio, are far more valuable.

Here’s the most important thing to remember about writing your bio: Don’t draw attention to negativities. For instance, do not say, “Josh has never written anything before.” No, no, no. Keep your biography positive and on point.

You should write it in the present tense, and in the third person. Keep the information pertinent, but don’t be afraid to add some colour, particularly if reflects an element in the novel. For instance,

“Josh Jones is a former lion tamer who worked for fifteen years in Blogg’s Circus before his unfortunate accident. His experiences allow him to fill his first novel, Murder Under the Big Top, with the sort of inside information lovers of both mysteries and the circus will enjoy.”

Your bio doesn’t have to be long. You can include:

Where you were born and raised — if it is unusual or if it forms a part of your story. You can draw a picture of the environment: “Josh was born in a log cabin in Illinois… No, wait, that’s not right. Josh was born in the less elegant part of Manhattan on a snowy morning in November. A day ever referred to by his mother as ‘Black Tuesday.’

Any prizes your have won. Again, I would avoid drawing attention to the absence of such things, but you can make it funny if it is in keeping with the tone of your novel. For instance, “Josh never won anything. Not for writing, not even for tiddlywinks because that snot-nosed third grader Ben Billis stole the title that should have been his.”

If you have previous writing credits you can mention them, but keep it brief. If you have no credits you can skip this bit.

You can mention something about where your idea for your novel came from. My grandmother gave me a copy of The Hound of the Baskervilles when I was seven, and I’ve been obsessed with Sherlock Holmes ever since. This tidbit of information became part of my bio for my first novel.

It’s OK to add some piece of irrelevant (to the public) personal information just to give the readers something to relate to. “Having finally escaped from his mother’s basement, Josh now lives with his wife, Judy, his three sons, two cats, a one-eared King Charles spaniel called Dickens, and an unsightly mold on the ceiling.”

Keep your bio short, make it individual, and try to write it in a similar tone to the novel. I’m in a very silly mood today, as I’m sure you have noticed, so I’ve veered towards humour. You don’t have to do that; in fact, you should avoid it, especially if your novel is very dark or sad.

Don’t stress over it. write about three bullet points of things that people might find interesting about you. If you’ve ever attended one of those ‘team building’ events that ask participants to list three things that no one knows about them, you’ll have the idea. “I’m Josh, and I have three nipples,” probably isn’t what most of us want to know, but it’s a place to start.

As Passover starts today (Monday), I’m off and I haven’t yet figured out what next week’s blog will address. If there is something you want me to cover, let me know in the comments. Have a great week, and see you next week.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/..." data-large-file="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/..." width="1880" height="1249" src="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/..." alt="" class="wp-image-17145" srcset="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 1880w, https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 150w, https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 300w, https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 768w, https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 1024w" sizes="(max-width: 1880px) 100vw, 1880px" />Photo by Download a pic Donate a buck! ^ on Pexels.comApril 16, 2024

Writing the Synopsis

Have you ever been in a supermarket and had someone offer you a sample of a new product, a square of cheese, or a taste of new soda? Or perhaps your department store has offered you squirts of a perfume or an aftershave. That should give you an idea of what the synopsis needs to do.

A synopsis should tell as much of the story as you can get into a small bite and excite the appetite of the recipient, the agent or publisher, henceforth referred to as the reader.

It may be as short as a single page, or it may be a chapter-by-chapter breakdown running to twenty pages or more. Remember, it must match the intended reader’s guidelines.

Most synopses run 500 to 700 words, written in single-space.

It must be written in the third person, present tense.

Some writers advocate for writing the synopsis in the same voice as the novel so the reader can get a feel for your style. My preference is to keep the synopsis purely neutral. You’ve included a chapter or three and the reader can grasp your style from those.

Some also advocate putting the genre in the body of the text; I prefer to make it part of the header along with the novel’s title, name of the author, and word-count. It makes it easier for the reader to find the information. You may include intended readership if you feel it’s important: “Young adult for ages 16-23 who enjoy fantasy,” for instance.

There are two ways of approaching how you write the synopsis — well, any sort of writing, really. You can start small and enlarge, or start big and cut back. What do I mean?

If you start small, you write maybe one sentence describing the hero, another on his goal, one on what’s at stake. Then, when you have a paragraph or two, you can expand on the details until you reach the word count.

Alternatively, you can just write the synopsis with all the details you think are essential, and then edit it down to the appropriate size later.

Your draft should include:

Your hero and the problem he faces. How the environment in which he lives complicates matters.The event that drew the protagonist into the events of the novel, followed by:The key events in the story and how the are resolved — put this in the the most basic terms possible.The resolution and aftermath. Don’t try to be clever and tell your recipient that they’ll have to read the book if they want to know how it ends. Many a good book has been ruined by a bad ending; the reader needs to know that yours isn’t one of them.The above can be condensed into three or four paragraphs. If there are other events or characters that have a major impact on the story — perhaps our hero has a love interest who he is afraid of losing. Or maybe an old friend who is on his side — these deserve mention, too. Furthermore, you should include the setting and time-period. If this is a fantasy or science fiction explain some of the essential components of the society. Even if it’s set in 1980’s New York give us a feeling for the prevailing culture that impacts the characters. For instance, perhaps the hero has AIDS and doesn’t want anyone to find out.

Whatever approach you take, remember these essentials:

Do not waffle. You have a limited word-count so make every word, uh, count.Delete the adjectives and adverbs. This isn’t the place to describe your heroine as a petite beauty with golden hair and eyes the colour of sapphire. (Please tell me you don’t write like that!) Use strong nouns and active verbs. You should be doing that anyway.Don’t delve into the psychology of the villain — or the hero for that matter — unless it’s essential, and you can do so succinctly. Of course, if it’s a psychological thriller, go for it, just keep it on point.Don’t muddy the story with subplots and extraneous characters unless they are essential to the recipient understanding the plot development.If you have the option of presenting a longer synopsis, you can devote some space to the more essential subplots and characters, just make it clear who your hero is and what he wants / needs to achieve.Include enough colour to set your story apart from others of its kind. An example of the hero’s humour, or some other characteristics that set him apart.Let me know if you have any comments or questions.

Next week, we’ll look at the author’s biography.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/..." data-large-file="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/..." width="1880" height="1253" src="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/..." alt="" class="wp-image-17119" srcset="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 1880w, https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 150w, https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 300w, https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 768w, https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 1024w" sizes="(max-width: 1880px) 100vw, 1880px" />Photo by Laura James on Pexels.comApril 9, 2024

Writing the Cover Letter

The cover letter is your introduction to a publisher or agent. Yes, it involves writing, but this isn’t your opportunity to be ‘creative’ in your letter. This is a business letter, and you need to treat it as such. Therefore, the letter needs to be clean, typed, and printed on good quality paper.

Here are some essential points to remember:

As I have said previously, select your agent or publisher with great care. Don’t just make up a list of names that you like, “Ooh, her name is Lily Hill, what a hoot! Let’s pick her.” No. Stop it. Pick agents who work with writers who are a lot like you. Their books are similar. They come across as the sort of person you can work with. With a list of names on hand — we suggested 12, if you recall — try to read any articles or blogs they have written, especially if they cover things that they like and / or things that drive them bonkers.

Armed with as much information as you can find, next read the writer’s guidelines for that agent or company. And here’s a pro tip: Follow it to the letter. If they say they want the first fifty pages, do not send them the entire manuscript. If they want a one page synopsis, do not send them a 10-page one.

Clear?

Good.

Next, address your query to a specific person. The whole, ‘Dear Sir or Madam’ is not only passé , it’s rude. Do you research. Find the person who is interested in your genre, or whatever type of book you are writing. Do not assume sex or marital status. Address the letter to the full name of the person, “Dear Mary Jones”, for instance.

Make sure the salutation, as well as the rest of the letter, is spelled impeccably. Don’t assume Chris Smith is spelled Christopher Smith. Perhaps it’s Christine Smyth. Or Kris Smythe.

Don’t address the agency or publisher as in, “Dear Melvin Whatsisname and Co. Agency.” You are addressing an individual, not a corporation.

Your letter shouldn’t be too long. One page is perfect. You can get away with two pages, but make sure every word counts. And don’t try to circumvent this rule by writing your letter in a miniscule 6-point font. No one will appreciate that.

Different writers take different approaches with their letters. Some advocate starting with a description of the novel. In other words, the blurb (see last week’s blog). Others prefer to open with an introduction. The latter is particularly important if you have met the person or were recommended to them by someone they would be likely to respect (a fellow author, for instance.)

Don’t be cute. This is a business letter, not an opportunity for you to gloat about how your mother thinks this is the best thing she’s ever written. Don’t tell jokes, or make promises, or make jokes combined with promises. “If you don’t accept this novel, I will have Liam Neeson find you and kill you.” No!

Don’t be arrogant. But don’t be too self-deprecating either. As in, “This is the greatest novel ever written and you’re a fool if you pass it up.” Yikes! But, yes, people have written such nonsense, and with stunning regularity. Little success, but regularity.

Neither do you want to say, “I know this novel isn’t very good, but you can probably fix it…” or, “I know you won’t want to publish this book, but my friends say it’s not bad and I should send it to you anyway.”

Do not exaggerate. “This book will easily sell a million copies…” or, “Do you want to get rich? Then you have to publish this book.”

These days most submissions are sent via email, but in the days when paper ruled, a number of writers would turn one page upside down. The idea was if the MS was returned with that page right side up it meant the recipient had read the entire thing. What one was meant to make of that, I never learned.

Other people would include a pressed flower, or a dollar bill. Again, don’t ask me why. A bribe? In any case, if you have something in mind, don’t do it. No one finds it amusing.

In future weeks we’ll talk about handling rejection (and success), but for now all I’ll say is never, ever phone someone after they’ve rejected your work to try to cajole them, bully them, or scream abuse at them. There is a black list and you don’t want to be on it.

Next week, though, we’ll discuss the synopsis.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/..." data-large-file="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/..." width="1880" height="1253" src="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/..." alt="" class="wp-image-17101" srcset="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 1880w, https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 150w, https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 300w, https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 768w, https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 1024w" sizes="(max-width: 1880px) 100vw, 1880px" />Photo by Ethan Wilkinson on Pexels.comApril 2, 2024

The Blurb: Or How to Sell your Book in One Minute

It is, essentially, a sales pitch. It appears on the back cover of a book as well as on websites that are selling the book, to let potential readers know what to expect.

What a blurb isn’tIt’s not a summary of the story. It’s not a synopsis. It’s a teaser; the literary equivalent to the trailer for a movie.

What is a blurb for?In addition to appearing on sites and on the book cover itself, the blurb can be used to sell the story to editors and / or publishers. It can, and should be, incorporated into the cover letter. As you can imagine, there’s a lot riding on it, so it’s important that you make it as compelling as possible.

A blurb can be a sales pitch, the so-called ‘elevator pitch’, where you tell someone about your story in around 30 seconds. Once you’ve written your blurb, commit it to memory. You never know when it may come in handy. The elevator pitch is so called because it should be brief enough for you to tell a potential agent about the story in the space of a short elevator ride. Of course, you can deliver the pitch at any time: at a writers’ conference, after a lecture, or in a cover letter.

Finally, a lot of writers swear by writing the blurb first, before they ever write a word of their novel. They then use the blurb to stay focused on the main story.

Elements of the blurbBrief. The blurb should be short, around 150 to 200 words. The shorter the better. Generally, it runs about two paragraphs — three if they’re very short.

Third person, present tense. Even if the novel is written in the first person, or is autobiographical, the blurb should be written in the third person. It should also be written in the present tense.

Enticing. The blurb should whet the appetite of the potential reader, whether that’s the guy browsing in the bookshop, or the New York agent. A great blurb can stop people in their tracks, it catches the imagination, and it makes them want to know more. I have posted some samples of great blurbs below.

Focused. The blurb should focus on the main character and story-line. It’s no place for subplots or incidental characters, no matter how much you like them. But, yes, there are exceptions, as you’ll see in a couple of the examples below.

How to write itIt’s a weird thing, but the shorter a piece is, the harder it seems to be to write. You can spend a year writing a novel of 100,000 words, but a 100-word blurb can easily take a couple of months. Well, for me, but then I’m a slow writer. If you remember those old dot-matrix printers, that’s sort of the way I write. Back and forth, back and forth, until the prose is as crisp as I can make it. You may be much more efficient, but you still shouldn’t try to rush it.

Some writers will record the blurb as if they were telling a friend about the story, then they edit it. If it works for you, then the blessings of the Muse be upon you. If not, well, there are other options.

My method is to write several versions of the blurb, at least five or six, and then leave them for a while to fester. Ferment. Whatever. Come back a few weeks later, and try to narrow the options to two or three.

Eventually, you may pick one, or, as is often the case for me, a combination of two or three of the best blended together seamlessly. Easy, right?

Ha!

Your goal is to get your readers’ literary taste buds tingling. You do this by telling us:

Who is your main characterWhat they wantWhat’s at stakeReflect the tone of the novelAdd a hint of mystery, romance, or sexSuggest actionOffer just enough of the story to spark interest.That’s a lot to ask of a couple of paragraphs; no wonder it can take so long to write.

Obviously, you don’t want to give away the ending in your blurb, but don’t be afraid of sharing at least the crux of the story. Consider using the ‘Rule of Three’. This rule states that people react best to ideas that are presented in groups of three. In the examples below, the clearest depiction of this is the first, Stig Abell’s Death Under a Little Sky. Another, more famous example, is Shakespeare’s, “Friends, Romans, Countrymen,” but no doubt you can think of many more.

Some examplesHere are some of my favourite blurbs from various novels. Go through your bookcase and find others. Learn by example:

A detective ready for a new life

For years, Jake Jackson has been a high-flying detective in the city. One day he receives a letter from his reclusive uncle – he has left Jake his property in the middle of the countryside. It is the perfect opportunity for a fresh start.A rural idyll the stuff of dreams

Life in the middle of nowhere is everything Jake could wish for. His home is beautiful and his surroundings are stunning. While the locals are eccentric, they are also friendly, and invite him to join their annual treasure hunt.A death that disrupts everything

Death Under a Little Sky by Stig Abell

What starts as an innocent game turns sinister, when a young woman’s bones are discovered. And Jake is thrust once again into the role of detective, as he tries to unearth a dangerous killer in this most unlikely of settings.

‘Shoot all the bluejays you want, if you can hit ’em, but remember it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird.’ A lawyer’s advice to his children as he defends the real mockingbird of Harper Lee’s classic novel – a black man falsely charged with the rape of a white girl.

Through the young eyes of Scout and Jem Finch, Harper Lee explores with exuberant humour the irrationality of adult attitudes to race and class in the Deep South of the 1930s. The conscience of a town steeped in prejudice, violence and hypocrisy is pricked by the stamina of one man’s struggle for justice.

But the weight of history will only tolerate so much. To Kill a Mockingbird is a coming-of-age story, an anti-racist novel, a historical drama of the Great Depression and a sublime example of the Southern writing tradition.

To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

Ex-military policeman Jack Reacher is a drifter. He’s just passing through Margrave, Georgia, and in less than an hour, he’s arrested for murder. Not much of a welcome. All Reacher knows is that he didn’t kill anybody. At least not here. Not lately. But he doesn’t stand a chance of convincing anyone. Not in Margrave, Georgia. Not a chance in hell.

Killing Floor by Lee Child

With only a yellowing photograph in hand, a young man — also named Jonathan Safran Foer — sets out to find the woman who may or may not have saved his grandfather from the Nazis. Accompanied by an old man haunted by memories of the war; an amorous dog named Sammy Davis, Junior, Junior; and the unforgettable Alex, a young Ukrainian translator who speaks in a sublimely butchered English, Jonathan is led on a quixotic journey over a devastated landscape and into an unexpected past.

Everything is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer

As a professional wizard, Harry Dresden knows firsthand that the “everyday” world is actually full of strange and magical things–and most of them don’t play well with humans. And those that do enjoy playing with humans far too much. He also knows he’s the best at what he does. Technically, he’s the only at what he does. But even though Harry is the only game in town, business–to put it mildly–stinks.

So when the Chicago P.D. bring him in to consult on a double homicide committed with black magic, Harry’s seeing dollar signs. But where there’s black magic, there’s a black mage behind it. And now that mage knows Harry’s name…

Storm Front by Jim Butcher

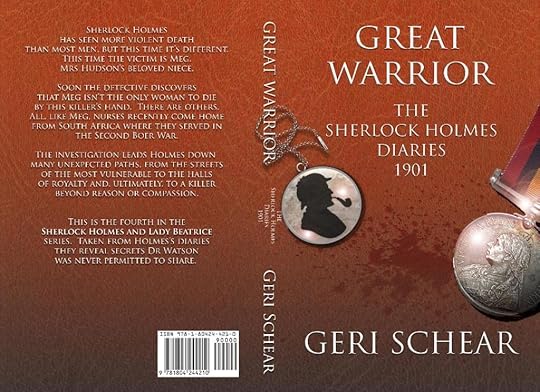

Finally, here’s one of my own. This is the blurb to my first published novel:

Sherlock Holmes thrives on danger. Sudden knife attacks, being stalked, and facing a network of assassins presents little more than a cheery break in the monotony. But the enigmatic Lady Beatrice presents danger of a different kind. Is she a murderer or a potential victim? Or something even more perilous? Uncovering her secrets could change Holmes’s life forever, and in ways even he cannot anticipate. The newly-discovered Holmes diaries shed light on a tale so potent, Watson was never permitted to reveal it.

A Biased Judgement: The Sherlock Holmes Diaries 1897 by Geri Schear

And below you’ll find the cover and blurb of my next novel, due out on May 15, 2024.

Next week, we’ll look at the cover letter.

March 26, 2024

The Submission Process

Over the next few weeks, we will cover the various items that you will need to include in your submission packet, but today I want you to think about two things:

How do you select the publishers or agents you want to send your manuscript to. AndHow will you track what you’ve sent, to whom, and when to expect a response.The answer to number one is to do your research. Look at books that are not dissimilar from your own and identify the agents or publishers for those authors. Go on any of the dozens of websites that list agents, especially those looking for new clients, or publishers who accept ‘over the transom’ (i.e., not represented by any agent) submissions. Once you have a list of names, I’d start with a dozen, then research each person or company. You want to know:

Are they accepting new clients? Some agents try to keep their numbers fairly low so they can do their best for everyone. Some publishers, indeed, the majority, never accept manuscripts except via an agent. If they aren’t accepting clients, don’t waste your time. Move on.If you identify an agent who is open to new clients, read their submission guidelines closely. Note: not every agent or publisher wants the same thing. Some want an author’s bio, some don’t; some want a 10-page synopsis, for others, a single page will done. Some agents want the first fifty pages, some three sample chapters, and some the entire manuscript. Make yourself familiar with the agent’s website. Often, agents will write a blog or some articles about the publishing industry and what they, themselves, are looking for. Getting a feel for the personality of the agent is worth your time especially if you mean to work with them.Check the organisation’s reputation. There are any number of sites that provide this information. If there are reports that the company or agent take an age to respond, you might want to skip them. Of course, if you have a particular fondness for this individual, you may decide it’s worth it. The choice is yours. More worrying is what the agent charges for. Some, for instance, will charge the author for making hard copies of the complete manuscript — that can get pricy. Also, postage, phone calls, and so forth. Know what to expect before you sign a contract.Keep an eye out for agents who attend writers’ conferences or other public events. If possible, try to attend some. If you live in a big city like London or New York, you may find there are plenty of opportunities available. Also, places like Hawaii, because even agents and publishers enjoy a bit of sun.Be prepared. Have what’s known as an ‘elevator pitch’ memorised. This is essentially a teaser that you could deliver in the time it takes an elevator to travel a couple of floors. Make it enticing. Don’t waffle. We’ll discuss that in more detail next week.Don’t waste your time pitching to an agent who doesn’t handle your sort of work. If they say, ‘Poetry only,’ don’t send them your multi-volume sexy space romp. Or if they say ‘Mysteries and Urban Fantasy only’, don’t try to sell them on your literary masterpiece.Once you’ve done your research, you need to keep a record of what you’ve sent to whom. By now, you’ve probably figured out that I love my spreadsheets. (I don’t know why I never see that embroidered on a sampler. Hmmph!), but there are other choices. Keep a notebook especially for agent / publisher information. I’d go with the loose-leaf type so it’s easier to move pages around and keep names in alphabetical order. Whatever approach you decide on, just make sure you keep it up to date. It’s frustrating for the author, and irksome for the agent or publisher when you submit a manuscript after you’ve already received a no. Here is the data you need to track:

Name of the company; name of the agent or editor — spelled perfectly, of course; email address; website; what they’re looking for; what their submission packet should contain; and notes, such as if you’ve met them, important quotes from their blog or something they said in a conference; anything else that stands out, such as awards they or their authors have won.

In addition, you need to include the name and type of manuscript you’ve sent; word count; date sent; and when to expect a reply. Yes, it’s a pain in the neck to write all this down — that’s one thing I like about the spreadsheet; I can copy and paste things like website addresses, or links to a blog, for instance.

Right now, you might be thinking this is an awful load of nonsense just to send an email, but in six months time when you’re still looking for an agent or publisher and can’t remember where you submitted your work, you’ll thank heaven — and me — that you had the good sense to keep a detailed record. Besides, even if you get lucky early on, you might need that info for subsequent manuscripts.

Next week we’ll look at the elevator pitch and the blurb in more detail.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/..." data-large-file="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/..." src="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/..." alt="" class="wp-image-17047" />Photo by Andrea Piacquadio on Pexels.comMarch 19, 2024

Before You Publish

Whether you plan to self-publish or submit your manuscript to an agent or traditional publisher, here is a checklist of what you need to do first. Since I’ve never self-published, I’m focusing on the traditional publishing approach. However, most of these items apply to both.

Final EditDo a line-by-line reading of your manuscript, checking every word is accurate and correctly spelled. There are several ways of making this more efficient:

Change the font before you read. I don’t know why this makes catching mistakes easier, but it does.Print the manuscript and edit the print copy.Use the audio function on Word. It will help you not only spot incorrect or misspelled words (because the programme doesn’t know how to pronounce them), but also when you have used the same word too many times in succession. The downside, though, is it can’t tell the difference between homophones, so if you’ve written ‘there’ instead of ‘their’, this approach on its own won’t help.Have someone Beta read the manuscript. I don’t know what I’d do without my BFF Jane, Beta-reader extraordinaire. If you decide to work with a Beta-reader, here are some things you should know in advance:

Decide your parameters in advance. Do you want a line-by-line analysis, or just a quick overview of the story? Be clear that you are not asking your Beta-reader to do any rewriting — unless that is what you want. Clarity now will prevent fall-outs later.Decide how feedback will be given. Do you want a marked-up manuscript returned, or a separate report, or a conversation. Set a time limit on how long the activity should take.Agree any form of recompense in advance.Be prepared for some friction as you both define your boundaries. Try not to take your reader’s feedback personally, and be ready to do some work after he / she has finished reviewing. Ideally, you want this feedback after your manuscript is mostly finished, but before that final draft. I should warn you that if your Beta-reader spots a major plot hole (or three), it can make you want to tear your hair out. But better you see these problems before you start submitting the manuscript. I know it wouldn’t work for everyone, but Jane frequently calls me while she is reviewing my stories. Sometimes she’s confused about something (generally it’s because I’ve done something goofy, such as accidentally deleted a page or duplicated one), or because she thinks she’s spotted a plot-hole. That allows me to review those issues immediately. A phone call can be much more effective than a later written report. For me, anyway.

Select a TitleThis is one of those things that sounds easy-peasy until you start to do it. Sometimes the title is obvious and you’ve had it in mind right from the beginning. My first novel in the Sherlock Holmes / Lady Beatrice series was called A Biased Judgement. I think I had the title from the minute I got the idea for the story. On the other hand, my most recent novel, Great Warrior, came after months of research and title-changes.

Whatever title you choose, it should be eye-catching and memorable. It can be useful, if you’re planning a series of books featuring the same character, to give the titles some element in common. Sue Grafton went with the alphabet, A is for Alibi, for instance. While Kathy Reichs used to use versions of ‘dead or death in hers — Death du Jour or Déjà Dead, though she seems to have moved on from that.

There used to be a rule that a title shouldn’t be longer than six words. Or maybe it was seven. I don’t think that’s true anymore. One-word titles remain popular. Try not to use anything too obscure, although, to be fair, if the book is good enough that isn’t necessarily a deal-breaker. Half the people who read The Big Sleep didn’t know it meant death, but it is still considered one of the best hard-boiled detective stories ever written. You can use quotes from scripture or poetry, or even suggested by the book itself. The Silence of the Lambs is a good example of the latter, as is To Kill a Mockingbird. Ultimately, pick a title you like, one that fits the story, and make it unique. A new novel called The Great Gatsby, for instance, is sure to confuse people.

Consider your OptionsConsider your publishing options. If you decide to go the self-publishing route, be prepared to do all the hard graft yourself. You’ll need to format the manuscript, get a cover designed, pay for an ISBN number, and take care of all the marketing. Depending on your temperament, you may recoil from any of these tasks; I know I would. Fortunately for me, I found a publisher who will do all these things for me. That doesn’t mean I have no role to play, but somehow I feel comforted by knowing that I have a publisher backing me.

If your novel fits into a genre, make sure the agent or publisher you are submitting to accepts stories of that sort. No, you’re not the one they’ll be sure to make an exception for. Save yourself some time and a lot of frustration and send it to people who will be likely to appreciate it.

If possible — and I’ll grant you, it’s a big ‘if’ — try to have some other pieces sold that fit the genre of your novel. Look up markets that specialise in, for instance, science fiction, and submit stories to them. Then, by the time you go hunting for a publisher, you’ll not only have credits to your name, but you’ll have credits specific to that genre. It can do a lot to move you up the slush pile.

Next week: we’ll start to look at the actual submission process.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/..." data-large-file="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/..." width="867" height="1300" src="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/..." alt="" class="wp-image-17012" srcset="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 867w, https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 100w, https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 200w, https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 768w" sizes="(max-width: 867px) 100vw, 867px" />Photo by Ron Lach on Pexels.comMarch 12, 2024

How to Use a Subplot

One of my favourite subplots in all the novels I’ve read lies in Catch-22 by Joseph Heller. It concerns Orr, a friend of Yossarian, the main character. Despite liking him, Yossarian can’t help but think that Orr is nuts. He does weird things. It’s not until the end of the book that Yossarian realises there was method in the madness. As Yossarian tries to find a way to escape the madness of WWII, the Orr subplot seems like a bit of light relief, at least at first. No, I won’t spoil it for you, all I will say is this book is the only one that, as soon as I finished reading it, I went back to the beginning and read it all over again. Because the Orr subplot is just that good.

A subplot can accomplish a lot of things in your novel. It can add to the tension, balance the grief or fear with humour, slow or speed up the pace, or reveal a new side to the main character.

Imagine this scenario:

The Subplot Must Stand AloneThere’s a new monster on the loose. Let’s say it’s a giant slug. The hero is warning people and trying various ways to get rid of the slug, but nothing works. In the meantime, there’s some comic relief: An old man, a retired gardener, is trying to build a new type of gun. The hero isn’t interested. A gun’s not going to impact the slug. But just when all hope seems lost, the old man shows up and attacks the slug with his giant gun, filled with salt. He sprays the slug who immediately melts away. Yes, the whole thing is very silly, but you get the idea.

I don’t mean it cannot intersect with the main storyline, but that it must have its own beginning, middle, and end. It must have its own structure which may or may not resemble the main storyline.

The Subplot Must Start Near the BeginningI’ve read a lot of nonsense about when the subplot should begin. Some say it should start at the beginning of the second act. Others say start with the subplot and then introduce the main story. My theory is… it depends. It depends on the story you’re writing, what contribution you want the subplot to make to that story, and what your gut tells you about when it should begin. In other words, toss the rulebook.

If your story is a mystery, let’s say a young woman is found dead in a river. Your story might begin with a man leaving a particular club, we’ll call it the Purple Jazz Night, or PJN for short. The man sees the girl getting into a gold-coloured car. Later, we find this man works at PJN and he’s obviously terrified of someone. This man with his anxieties and insecurities obviously knows something. The question is can our hero, the detective or perhaps the dead woman’s sister, find him before the villains do?

On the other hand, a romance can begin later. Perhaps the main storyline is about a man who buys a house in the country. He wants quiet and solitude. Then he discovers his next door neighbour is a single woman with two young kids. The subplot might be the woman’s mother trying to get them together — or keep them apart. Perhaps the man’s first wife died under mysterious circumstances and a nice policeman warns the woman to be careful of him. Now we may have two subplots.

The point is, you can make all the hard rules about writing that you like, but as long as the story works, no one will be too bothered. This is true not only of subplots, but of any aspect of writing you can imagine.

The Subplot Must Add to the Overall StoryRegardless of what your main story is about, the subplot must bring something to the narrative. It must impact the main character, though the main character may not even realise it — his ex-wife scuppers his relationship with a new woman, or perhaps an old friend helps him get the job of his dreams. Your subplot could be about the impact our hero (?) had on the lives of others, and they want to pay him back. For good or ill.

You could write a subplot about someone the main character has never met and will never meet. Say his great-grandmother. We have the hero travelling from American back to Ireland, where his family came from, and looking for his great-grandmother’s house. In the meantime, we have the grandmother’s account of her days and her struggles for survival. Perhaps the visitor will see a picture of the old woman, or will read some of her letters. That may be as close as he gets to her, but unknown to himself, he mirrors her character and even her experiences in many ways.

The Subplot May Differ in Style from the Main StoryYou may choose to write your main story in the first person, but you don’t have to write your subplot that way. You could opt to write it in the third person omniscient, or even in the second person. (See Bright Lights Big City for an example of this approach.) The subplot may be purely expositionary, perhaps written in the form of newspaper articles, or historical journals. The point is, you can add some texture to your novel by presenting your subplot in a different style.

The Subplot Must Intersect with the Main Storyline

There are many ways this can happen, even if the characters never meet. Perhaps the main character only feels the effects of the subplot character’s largess (or malevolence) through later events. I’m reminded of the end of The Lady of Shalott (by Tennyson). The lady is under a curse that she must weave a web and never leave the loom. She happens to see Sir Lancelot pass by and, on impulse, leaves the loom and runs out in hopes of seeing him. At the end, he finds her body in a boat and has no idea the part he played, albeit innocently, in her death.

The Lady of Shalott by John William Waterhouse

In most cases, though, the main character eventually will find himself enmeshed in that subplot. Perhaps the teenager who seemed no more than annoying is actually a vampire hunter and soon the ‘hero’ will be toast. Uh, dust. Another good example is the Bertha Mason subplot in Jane Eyre. This ends up having a few tentacles: the man who comes from the West Indies to see Bertha has ties to Jane’s own family. He also reveals (much later) that Bertha is actually Rochester’s wife. Dirty pool to reveal that at the moment when Rochester and Jane are to be married, but you can’t beat it for tension.

How to Add a SubplotA lot depends, of course, on how you approach your story. If you are, like me, more of a pantser than a planner, you just follow your instinct and add the subplot narrative as you go along. One word of caution, however: if you write a subplot you have to bring it to an end. Don’t let it tail off somewhere in chapter five and forget about it. The ending of the subplot must tie in with the main narrative.

If you are more a planner and like to know as much about your story as possible before you start writing, then you should determine what your subplot should be, where it begins, and where you need to place it in the narrative.

As I’ve said before, I have my own way of working. I start with a premise, some idea of the ending, and maybe one or two key points along the way. I know who my main character is and what they want. Then I write my first draft. I make it as complete as possible and it always amazes me how often I end with whole scenes that need little or no revision.

Sometimes my first draft is several thousand words too long; sometimes it’s too short. It doesn’t matter, because fixing it is what subsequent drafts are for.

With that first draft complete, I can see where I want the subplot to go. I know what it should be about, and what impact it will have on the main story. That’s assuming I haven’t already set the subplot in place. Speaking purely for myself, having the subplot in mind right from the beginning is far and away the best way to add it. However, if you have a decent first, or even second draft, you can still add a subplot if you find the narrative is lacking something.

Because I write mystery stories, I like to give small hints about the subplot fairly early on. The hints become more frequent over the next few chapters. Then, once I’m sure that I’ve piqued the reader’s interest, I give more specific information and let the subplot grow.

In my most recent book, Great Warrior (Shameless Plug: due to be published by MX on May 15 2024) The main story concerns Sherlock Holmes being awakened from a deep sleep by a woman’s scream. He drags himself downstairs and learns that Mrs Hudson’s niece, a nurse who was living with Mrs H, has been murdered.

The subplot is almost invisible unless the astute reader asks, why is Holmes so exhausted. The reasons for this are revealed slowly and we’re about a third of the way through the novel before we get the full story. No, I’m not going to spoil it, except to say it brings in another layer of mystery and tension, and is not resolved until close to the last page.

One important thing to remember when you are planning your subplot is what you want it to achieve. If it’s to help you manage the tension in the story, then choose the points where you will add the continuation of the subplot. Perhaps right after a moment o crisis, as the hero is in trouble and has no idea how to get out of it. Then, as if it were a film, you switch to a different character, a different part of the plot. This drives readers crazy — but in a good way! To quote Willy Wonka, “The tension is terrible. I hope it lasts.”

You may choose to add the subplot in whole chapters. I’ve seen some writers do this with every alternative, or third or fourth chapter. Unless you’re writing in a completely different style, you need to signpost to the reader that this is a secondary narrative. Some writers will use different fonts, or will name the chapter for the character involved. Perhaps the main character is Barbie, and the subplot is Ken. Unless you want to have all Barbie’s story in pink (not recommended!), it would be easier for the reader if you just title the chapters differently.

Another way to add the subplot is to find elements that connect it to the main story and use those. What do I mean? Well, in addition to adding a subplot passage at the peak of the main story’s tension, you can find elements that the two threads have in common. For instance, main character is eating an orange. Subplot appears and tells about that secondary character picked oranges one summer in Greece. You don’t have to do this every time, but it can be a nice touch as you come to the end of both storylines, to suggest the threads coming together.

Whole books have been written about writing subplots. It’s not an easy subject, and getting it right can be tricky. But with practice and with learning just listen to your subconscious, you will master it.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/..." data-large-file="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/..." width="867" height="1300" src="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/..." alt="" class="wp-image-16962" style="width:415px;height:auto" srcset="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 867w, https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 100w, https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 200w, https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 768w" sizes="(max-width: 867px) 100vw, 867px" />Photo by cottonbro studio on Pexels.comMarch 5, 2024

What You Should Know About Exposition and Pacing

Exposition. It’s not a dirty word, though many people would have you believe that it is. It’s an essential part of fiction and, handled correctly, it is as valuable as any of those scenes we talked about last week. Exposition is not only essential to the story itself, but it can help you pace your story in a more effective way. So, what is exposition?

If you look at the dictionary, you’ll see some guff about how exposition comes at the beginning of the story to introduce the characters and set the scene. Yikes! Be very careful about opening a story with exposition. You’re much better off starting, as I’ve said before, in medias res, or in the middle of the action. Alternatively, you can open with a change in the status quo: the character just received a terrible diagnosis, or a handsome stranger just arrived in town.

My definition of exposition is it’s essential information, either factual or novel-specific. It answers the who, why, where, when, how, and what of the story. Where and when the story takes place. The weather. The characters and how they relate to one another. In a story based in a very specific world, literally as in science fiction, or figuratively as in a submarine, a government department, or a little town called Hobbiton in the Shire, you have to make it believable and understandable to the reader.

There are a number of ways to weave that ‘background’ information into the action: Let’s look at some of them:

“I can’t see,” Gail said with a sneeze. “It’s black as pitch in here. It’s probably haunted.”

“Well, it’s no lighter outside, honey,” Scott said, reassuring as always. “And at least it’s dry. Anyway, it will be dawn soon. Look, I know this creepy old house isn’t ideal, but it’s better than being stuck out there in some bloody Irish field miles from civilization in the middle of a gale.” He paused. “I’d be more worried about rats than ghosts.”

This my attempt at showing how you can establish time of day, location, and a sense of the environment without any expositioning whatsoever. Well, the exposition is actually there, it’s just carefully disguised.

Dialogue is an excellent way of revealing details to the reader. However, you have to be subtle. Don’t have one character tell another something they already know. For instance:

“As you know, Michael, I’m a single mother with two boys, Brian aged six, and Steve aged four…” At which point Michael replies, “For goodness sakes, Janice, I’ve lived next door to you for twenty years. Why are you telling me things I already know?”

A minor caveat to that would be if the character doing the explaining is suffering from a brain trauma and doesn’t remember things. There may be other reasons for such inelegant information-dropping, but I can’t think of any.

Compare that exchange between Janice and Michael with the small dialogue exchange I posted above it. It tells you the characters are in Ireland, in an abandoned house, just before dawn, in a storm. Sure there are things we’re not told — what were they doing in the field in the middle of the night, for instance — but if the writing is lively enough, we’re happy to keep reading and let the writer reveal more information as she goes along.

Another way is to reveal details in the thoughts of the characters, even in the middle of the action. CS Forester (The African Queen; the Horatio Hornblower stories), was an expert at this. Look at this brief paragraph:

“The French nobleman who had given Hornblower fencing lessons had spoken of the coup des deux veuves, the reckless attack that made two widows — here was an example of it.”

CS Forester: ‘Hornblower During the Crisis‘

In thirty words, Forester has revealed that Hornblower is a trained swordsman, and trained by a Frenchman, which implies excellence. The author demonstrates that Hornblower is familiar with fencing terminology, and that he is facing an opponent who is not nearly as clever as Hornblower himself.

We can also see that this brief comment comes in the middle of a swordfight, one in which our hero’s life is on the line (the comment about the move making two widows suggests both opponents are likely to die as a result of this manoeuver), but he is still clear-headed enough to identify the move, and remember his training.

In the famous fencing scene in The Princess Bride (you saw it coming, didn’t you?), Inigo and the Man in Black exchange banter about various fencing masters as they duel. I have it on good authority (BFF, Jane), that the comments are accurate. The conversation reveals two well-matched swordsmen, both men of honour, who have studied their craft with equal zeal. Oh, and neither is left handed!

Dialogue isn’t the only option. For instance, you can use the character’s internal monologue to convey the same information. Here are two examples, the first a flat ‘just give me the facts, ma’am,’ version, and the second in the form of an internal dialogue. See which you prefer.

HMS Belfast is 613 feet six inches long. She is a cruiser of the third Town class and is moored near Tower Bridge on the Thames.. In 2019 she received 327,000 visitors.

OR

In his soul, Danny had been born a seafarer. Not a sailor, which suggested little white hats and lots of deck scrubbing. No, he wanted to be a seafarer, complete with weathered cheeks and a bushy beard like he saw in his storybooks. The nearest he ever came to this dream, alas, was during his monthly visits to HMS Belfast moored on the Thames. He still felt a thrill as he ran his hand up her polished wood. Almost, he thought, he could hear her purring in appreciation. He’d visited her so often that he felt he knew every inch of her 613 feet and six inches. Don’t forget those inches, son, every one of them counts. He smiled up at his father. He got it. Dad was as much married to the sea as he ever was to Danny’s mother. So he only worked on the ferry to Spain, he was still a mariner. That was another good word, Danny thought. As soon as he was old enough, he’d join the navy. Maybe one day he’d be stationed upon a ship even more impressive than this cruiser, HMS Belfast.

Now, I know the second is about twice as long as the first, but it humanises the details. It reveals those dull statistics in a way that seems romantic to Danny and his father, as well as revealing Danny’s obsession. This is one of several ways you can weave exposition into the narrative without it deadening the flow.

Our next option is Letters. These can be a helpful way of inserting essential information into the story. For one of my favourite examples, read the lyrics of The Mountains of Mourne by Percy French. Here’s the first verse as a teaser:

Oh, Mary, this London’s a wonderful sight,

Percy French, ‘The Mountains of Mourne’

With the people here working by day and by night.

They don’t sow potatoes, nor barley, nor wheat,

But there’s gangs of them digging for gold in the street.

At least when I asked them that’s what I was told,

So I just took a hand at this digging for gold,

But for all that I found there I might as well be

Where the Mountains of Mourne sweep down to the sea.

These lyrics reveal how a talented writer can capture facts, a sense of place, and a sense of homesickness in a letter to his girlfriend back home in Ireland. There are many other examples, Dracula (Bram Stoker), Pride and Prejudice (Jane Austen), and The Old Curiosity Shop (Charles Dickens) are just a few examples. The most important thing about using letters as a means of inserting exposition is to remember it’s supposed to be a letter. Yes, it should relate the important information you want the reader to know, but you also need to make it reflective of the character writing it, as well as the relationship between them and the intended recipient. Take a leaf out of Percy French’s book and make the letter entertaining, fun, and heartfelt.

Likewise, exposition can come in the form of a flashback. This is, or can be, closer to the simple prose but you can probably guess the important difference: Suppose that you’ve already established the predicament your character is in at the start of the book, and so hooked the reader. Now you have to explain how the character got there. In Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights the story begins with a visitor being given the owner, Heathcliff’s, bedroom and subsequently encounters the ghost of Heathcliff’s dead lover, Cathy. Then the housekeeper starts to tell the story of their doomed romance, all of it a flashback.

Imagine you were writing a story about a catastrophe, for instance. Let’s say it’s the sinking of a huge ship. You could, of course, start the tale with the passengers coming on board and sharing information about this great liner. Or, you could start when the ship hits, let’s say, an iceberg. As your main character tries to find a lifeboat, she flashes back to the first time she ever heard of the ship. Or you could start the story in the lifeboat and then go back to the beginning. Opening with the action piques the reader’s interest and will keep them reading even when you have to introduce some backstory.

I’d suggest you read as widely as possible to see how writers use these techniques. My favourite practitioners of making exposition seem seamless are Tolkien, Frederick Forsyth, and CS Forester. Here’s a great example of Forsyth telling us the time and the temperature in a way that we almost don’t notice:

It is cold at six-forty in the morning on a March day in Paris, and seems even colder when a man is about to be executed by firing squad

Frederick Forsyth, ‘The Day of the Jackal’

It’s wonderful, isn’t it? And notice, too, how he saves all his punch for the last four words. How can we stop reading at that point?

Finally, there’s the paragraph or more of information you want the reader to know. World-building, you might call it. The details may include the time, day, year, location, and any technical data it’s essential for your reader to know. If your character is an astronaut, for instance, you may need to tell us something about his training and his concerns as he prepares to launch. The reader doesn’t need to be a rocket scientist to understand what you’re telling us, but if he is a rocket scientist he needs to be sure that you know what you’re talking about.

Exposition and PacingThere is a time, however, when putting in a paragraph of exposition all on its own is important, and the best example of this is when you need to cool down the action.

In one of the scenarios I offered above, I suggested you might write a story about someone on an ocean liner that sinks. Imagine your heroine feels the ship lurch and hears people screaming. She asks a crewman where she can get a lifeboat. “Ain’t none left, love,” he says and hurries away.

Now that you have the reader’s attention and concern — maybe the woman has a baby, or is pregnant, adding to the tension — you can leave her standing there and give us a paragraph of exposition. This is carefully calculated to ensure the reader doesn’t toss the book. They want to know what happened to that nice lady who helped others into the last lifeboat and said she’d wait. You could add to the tension by moving on to the Captain giving the order to abandon boat. Or our heroine’s husband who is waiting for her in New York. But if exposition is needed, use it to your advantage and place it where it will control the pace of the story.

Everyone wants to write a page-turner. Unfortunately, some writers feel there should constant action, rushing from one climax to the next without drawing a breath. No, that’s just as bad an idea as no action at all. As I said in my post about structure, the story needs to have a series of rising and falling actions. Nothing drops the action more effectively than a poorly executed block of exposition. But if you use it carefully, disguise it when you can, and include it when you need to. Written with grace and style, of course.

Next week: We’ll look at subplots.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/..." data-large-file="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/..." width="1734" height="1300" src="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/..." alt="" class="wp-image-16939" srcset="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 1734w, https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 150w, https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 300w, https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 768w, https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 1024w" sizes="(max-width: 1734px) 100vw, 1734px" />Photo by Luan Rezende on Pexels.comFebruary 27, 2024

Making a Scene

Last week, we talked about the overall structure of the novel. This week I want to focus on the core element of every story, the scene.

Some writers create a list of every scene that will appear in their novel before they start writing. Although I don’t do that, I can understand the benefits of the approach. One being that if you find it difficult to write your story in a linear manner, you can write whatever scenes most appeal to you at that moment. You can also move scenes around in order to increase the pace or the tension. Yes, you can do that in writing a linear approach, too, but keeping a list of the scenes can be helpful when it comes to looking at the structure.

What is a scene?A scene is a component of a larger work, a novel or a play, for instance. While it is essential to the whole, it can also stand on its own.

What are the essential elements of a scene?The settingThe character / charactersThe objective ConflictSuccess or failureI would add that the scene should also contain a point of view and a plot. I’m sure that comes as no surprise, however, it’s important to make a distinction between the plot-driven scene, and the exposition-heavy elements that add to the reader’s understanding irrespective of the plot. For instance, perhaps while he is planning his hike, Mark does some research and learns a lot about the moors. The flora and fauna, weather patters, and how many people get lost there every year. These are merely facts, but knowing them will add to the tension if Mark later gets lost on the moor.

You already know whose story you’re writing, at least, I hope you do. If this is Mark’s story, we can probably infer that he will survive his ordeal on the moor. Unless like Hitchcock you plan to kill off your main character half-way through the story (as in Psycho), the main character’s survival is usually a foregone conclusion. However, you may have selected a different main character, perhaps it’s Mark’s brother, or it’s a policeman who is investigating Mark’s disappearance. You can certainly open the story with Mark having some compelling, but unspecified reason for venturing out on the moor. He disappears in the mist so the reader doesn’t know what has happened to him, until someone starts investigating.

No matter whose story it is, you have to give us a point of view. Is can be omniscient third person, or limited first person, or whatever suits the story.

The Setting: Time and Place

As with the novel, the individual scene needs a sense of location and time. If you ever read a script you will see that each scene includes things like: “Joe’s apartment. 2023. Noon. Enter Joe and Mike.”

The setting means the place, but broad and specific. By that I mean it can include the country, as well as the specific environment where the scene occurs. For instance, a hotel room in the bad part of Liverpool; Mark’s penthouse on Park Avenue, New York; or something like, ‘the middle of the Yorkshire moors.’

In addition, you should convey some sense of the time of year. You can reflect this in nature — from a distance, the New York streets look like they’ve been doused with Cornflakes thanks to all those fallen leaves. Or a character’s reference — it would be Christmas in two weeks. Or connect the time of year with some other specific event, He glanced at the watch Paul had given him for his birthday. Amazingly, it still ran three whole weeks later. Paul was so cheap and he was always looking for a ‘bargain.’ Plus, he always took advantage of the fact that Mark’s birthday was on New Year’s Day. For as long as he could remember, Mark always got a one-for-two sort of present from his stingy brother.

It helps, too, to note the time of day. Depending on the scenario and the goal, it gives the reader an idea of how pressing the situation may be to the character. For instance, Dave needs to get money into the bank by 5pm or his bid on the house of his dreams will be neglected. Or his electric payment won’t go through and the power will be shut off, and his wife will accuse him of being a loser and walk out on him.

By making an event time-specific, you increase the tension in the scene.

As an example, let’s imagine a scene in which a man is hiking across the moors. He’s hoping to get to an inn before nightfall. Right now it’s mid-afternoon, but the weather is turning. A light rain is falling, the temperature has dropped, and he can see fog coming in.

For a minute Mark thought his watch was running fast. It would be just like his crummy brother to give him a cheap knock-off for his combined birthday and Christmas, though, as Mark had pointed out many times, a New Year’s Day birthday wasn’t the same thing. But after examining the watch for a minute and comparing the time with his phone, he saw the thing was working fine, and after three whole months, too. Still, 4pm. How on earth did it get so late? He’d expected to find an inn by three, at the latest. Not for the first time he had doubts about the compass Paul had given him the year before. It looked suspiciously like a cheap prize in a Christmas cracker, but he, Mark, had said nothing, wanting to keep the peace.

He shook his head as if he could banish all thoughts of his brother by the exertion. All he needed right now was to get lost in the middle of the moor. People died here, he knew. Went for a hike, just like him, and were never seen again. And as if some bloody-minded stage-hand were trying to add to his misery, it started to rain. That thin, misty type of wetness that soaks a man as surely as a deluge. It would be dark soon and, oh great, was that a mist rolling in?

This is a quick first draft piece, written to make that point that you can encapsulate the time and place, as well as the man’s predicament, and his goal: to reach an inn by nightfall — indeed, with the fog coming in that might be even more urgent a need. We don’t need to spell out the consequences for failure, it’s already implied in the comment that people had died on the moor.

Character / Characters

There is just the one character in this scene. We’ll call him Mark. As this is a scene in a longer work, we might already know why he’s walking on the moor. Maybe he’s trying to lose weight, or he’s trying to win a bet. Perhaps there’s a beautiful woman who lives in a nearby town, and he’s hoping to meet her by ‘casually’ showing up as a hiker. Or perhaps he’s hoping to get to some remote village where an old friend of his mother’s lives. A friend who might know something about his mother’s disappearance. It’s your story, so you can decide why Mark is there. By the way, you don’t have to tell your readers everything up front. A little mystery in any sort of novel is a plus. You can show Mark on this long walk without explaining what he’s up to, and reveal that information later, perhaps in another scene.

The Objective

It’s fine if you decide to hold back Mark’s reason for walking across this lonely moor on is own, and reveal it later. One caveat, though: If you decide to play coy with the reader, the reveal must be worth something when it comes. If you give us a lot of drama about how Mark is enduring these hardships but imply he has a good reason for it, we won’t be impressed if it turns out that he’s hoping to win a fiver from a mate. Then again, he could still be trying to win a bet because if he does his brother (let’s say) has agreed to donate bone marrow to Mark’s sick daughter.

If the motivation is minor — losing weight, as I said before — then you can reveal it up front. But you need to show the reader that he has a good reason for wanting to do so. Perhaps he’s in danger of a heart attack if he doesn’t drop a few pounds. Or perhaps he’s been struggling with depression and he thinks improving his health and fitness will raise his spirits. Whatever the reason may be, we need to be clear about the consequences of failure.

Conflict

The first thing that comes to most of our minds when we think of conflict is fist-fights, brawls, wars, and other types of violence. Those are certainly forms of conflict, but there are others. In the following examples I’ve written ‘man’ but, of course, that includes women, too. For instance:

Marital disputesStrong-willed childrenNasty neighboursMan against animals (naughty dog, savage wolf, a flea infestation. You get the idea.)Man against the environment. Mark alone on the moor with a fog coming in. Man on a desert island. Man alone in the ocean trying to reach land. Or David Bowie’s Major Tom ‘floating round a tin can’ in space. Man against machines, for instance a broken washing machine. A printer that constantly jams. A computer that seems to have a mind of its own.Man against god. This can be a character railing against the believers of a different religion or cult; blaming the Almighty for the death of his child; or feeling ‘called’ to something like the priesthood and not wanting to do it.Outcome

As with the elements of the structure, the outcome of the issue can be one of the following:

Complete success. Mark finds the inn just in time, and meets the girl, loses the weight, wins the bet, etc.

Partial success. He gets to the inn but doesn’t meet the girl, or finds that she’s married; he loses weight, but his health is no better; he wins the bet, but his brother reneges.

Complete failure: He doesn’t get to the inn and has to spend the night on the moor. He ends up going home, cold, wet, and hungry, and hasn’t come close to meeting his objectives.

Indeterminate: The scene ends with Mark walking into the fog. The next scene shows us two of Mark’s friends discussing his disappearance.

Rising and Falling ActionJust like the structure of the novel, the scene needs the rising falling action. There’s the status quo: Mark on the moor. Perhaps you could begin on the train before he gets there. If so, you could have a local warn him that it will be foggy later. Then the rising action when he realises it’s getting dark and he’s no closer to his destination. The climax might be him losing his compass, realising he’s lost, or he admits defeat and decides to go back to the railway. This is the decline from the climax as he essentially returns to the start. These are just some top-of-my-head ideas. Perhaps he finds a body on the moor. Or he hears a wolf in the distance. Or, perhaps he meets a couple of dangerous looking men. It’s your tale, take it where you wish. Just remember that by the end of the scene, the character should be either closer to his primary goal, or further away from it.

That’s it for this week, my friends. Next week, we’ll look at exposition and pacing. I hope you’ll join me.

February 20, 2024

How to Structure your Novel

There are any number of structures that have been developed by canny writers. The graphic images of these are all over the internet. They range from the simple inverted V, the W, and a number of rising and falling lines that resemble an ECG (EKG if you’re American). None of these are perfect. Some will work better for your story than others. This is one reason I suggest completing your first draft / outline before you pay any attention to the structure. Once you have an idea of all the important plot points, you can then make sure you have a good foundation already in place. I tend to do this instinctively, and I’m sure writers in ages past did, too. Before there were books on writing, videos explaining how to build tension and so forth, writers were guided by the books they’d read, and what kept readers reading.

You may prefer to select a structure before you begin writing, and use that as a guide. There’s nothing wrong with this approach. Just think of the structure as a road map.

Different approaches appeal to different writers. Also, you may find that what works for one novel doesn’t really cut it for another. This is one reason why I prefer to work instinctively and let the story guide me.

Types of Novel StructureThere are several types of structure — like the difference between the bungalow, the 2-story house, and the flat. You can’t say one is better than the other, it depends on your needs.

Here are the most common approaches:

Classical (or basic). This looks like a right angle triangle. Leading to the base on the left is the beginning or status quo. Then we go up the left side of the triangle to indicate the rising action. At the peak is the climax, then, coming down on the right, we have the falling action which levels on the bottom to suggest a resolution or return to the status quo.Freytag’s Pyramid is essentially the same as above, though some versions will use ‘exposition’ rather than ‘beginning’ or ‘status quo’. I’m not a fan of this because it suggests the writer can tell rather than show. However, this type of structure was used by the ancient Greeks and they had no problem having a chorus telling us what the situation is at the start of the play. Likewise, fairy tales generally begin with a summary of the situation. Also, some versions of this format will depict the final, line instead of being at the same level as the first,, is higher, indicating that nothing is exactly the same. Cinderella has married the prince, Antigone has died for her principles (and the king’s son has joined her). The Hero’s Journey. Whole books have been written about this, but it all began with the seminal Joseph Campbell book. Or you could go with Christopher Vogler’s more simplified version. The hero’s journey starts with the hero being offered an adventure of some sort. He refuses. Then he encounters someone who acts as a mentor. There follows a series of challenges, success or failure, and the return home. If you want to see this in action, almost any heroic tale with do, or for something less weighty, try The Hobbit.The Fichtean Curve. When I mentioned that some some graphs look like ECGs, this is the one I was thinking of. While I don’t set out to use any particular novels, my stories tend to end up this way. It starts with the action and gets right into things. Then, the rising action is a series of bumps as the hero faces complication after complication on the road to resolution. It culminates with the climax followed by the falling action. Many suspense novels use this structure. 27 Chapters. Some people like to take a methodical, mathematical approach to writing. Let me introduce you to the so-called 27 chapters method. As a more spontaneous writer, I’m not a fan. However, many writers like these sort of rules because they offer a sort of template to work from. If this this appeals to you, or if you’re curious to know more, click on the link.Three Act Structure. Possibly the most common today, if only because TV writers seem particularly fond of it. One of the things that works so well about it is its adaptability. Even the hero’s journey or the Fichtean Curve can work in the three act structure. You’ve heard that every story needs a beginning, a middle, and an end? Well, here’s what that looks like:ACT 1: The Status QuoWe enter the world of the story. This includes the physical environment, the time period, the main character(s) and what they want, and the general tone of the story. We meet the protagonist(s) and learn what his goal is. We also discover what he is up against.

Once we have established the status quo, we learn what has happened to disrupt it. For Harry Potter it’s discovering that he’s a wizard and has a place in Hogwarts. Frodo learns that the ring Bilbo gave him is most likely the One Ring created by Sauron. For Jane and Elizabeth Bennet it’s learning that the wealthy (and single!) Mr Bingley and his friend Mr Darcy have come to stay in the neighbourhood. This disruption to the status quo, even if it’s positive it’s still a disruption, is the inciting incident. It’s the first domino to be toppled.

The first act also shows the hero responding to the inciting incident. They decide to accept the challenge, whatever that challenge may be. And, of course, you may opt to have the hero refuse the challenge, but accept it later.

ACT 2: The Rising ActionThis is, arguably, where most writers come unstuck. It’s not too difficult to imagine the beginning of the story, or the ending. But the middle bit? Yes, that’s often a challenge.

Act 2 is often called the rising action. This is when things get complicated. As the protagonist makes steps towards reaching his goal, he meets obstacles all along the way. It’s a one-step-forward-two-steps-back situation. After all, if the protagonist reaches their goal without much difficulty, it’s, first, not much of a challenge for him, and second, it makes for very boring reading.

Depending on the sort of story you’re writing, the following sort of things happen:

The boy and girl have a fight. Or she learns that he has (apparently) lied. Or has a wife locked up in the attic. Or is getting ready to emigrate to Australia. The list of suspects increases, the red herrings abound, and the bodies are piling up.The aliens that you were suspicious of now seem downright dangerous, but no one will believe you.The middle point. This is where things all seem to fall apart. Elizabeth Bennet learns that Mr Darcy kept Bingley from seeing Jane, Elizabeth’s beloved sister, when both Jane and Bingley were in London. Or the suspect that everyone believed was the killer is proved conclusively to be innocent. Or the hero fails to win the scholarship he was counting on so he could get into university. It is, in short, a shambles.

Additional complications. You don’t have to offer this, but depending on the type of novel, you may find it useful. For instance, once it seems impossible for the prime suspect to be the killer, the detective is taken off the case. He’s still sure he’s right, but how can he prove it when someone else has taken over taken over the case? His case.

The lad whose scholarship has been denied has been helping an old man with some menial chore. This has seemed like comic relief up to this point. Then it turns out the old man is very wealthy or influential with the university, and thanks to him the lad is accepted. Or maybe the scholarship went to some underhanded rival of our hero. Someone hears the rival boasting about how he cheated, and the scholarship is taken from him and given to the hero instead. All that matters is that both the complication and the resolution arise plausibly from the elements you have already written.

What if you haven’t written it? Don’t panic! This happens more times than I’ve had hot dinners. Once you decide what your complication should be, you can go back and set it up several chapters earlier. Give readers a hint that the rival is going to cheat. And, by the same token, the elements of the resolution can also be inserted earlier, ready for you to use them at the proper moment. This is why you were leaving all those notes for yourself in the first draft. And, my, won’t you look clever!

Act 3: Crisis and ResolutionThe crisis is when things seem to fall apart. The scholarship lad discovers he will have to pay for his own books, but he can’t afford it. The detective happens upon a piece of evidence that seems to prove conclusively that the killer could not be his suspect. Elizabeth Bennet learns that her young sister, Lydia, has eloped with the dastardly Mr Wickham. The family is ruined! How will she ever win Mr Darcy now? How will Jane find happiness with Mr Bingley? Oh, what a tragedy.

Once everything seems to fall apart, you can either fix it — that is, your character can — or you can let this calamity destroy the hero’s life. If you opt to take the latter approach, the last part of the novel shows the hero’s descent. Or, he could find a new direction with lessons learned from his failure. Or perhaps he can overcome the crisis and emerge victorious.

However you choose to resolve the climax, the resolution must arise from pre-established facts and characters. No fair introducing fairy godmothers or Greek gods unless they’re already part of the backstory. For instance, the schoolboy has been given a special skateboard that flies, he is told, as a birthday present. He’s never tested it because he’s a) scared and b) doesn’t believe it can fly. But he has it with him when he and his friend a trapped on the wrong side of a raging river. Now is the time to bring his courage to bear and rescue himself and his buddy.

The last part of the novel introduces the new status quo. This might be better than where we started, or it could be worse. You need to ask yourself how the hero has changed, and how he has impacted the people around him.

Finally, I had planned to discuss that essential building block of the novel, the scene, but this piece is already much too long. So, I shall cover that next week, and show how the scenes build the narrative.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/..." data-large-file="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/..." width="1880" height="1253" src="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/..." alt="" class="wp-image-16894" srcset="https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 1880w, https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 150w, https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 300w, https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 768w, https://rycardus.files.wordpress.com/... 1024w" sizes="(max-width: 1880px) 100vw, 1880px" />Photo by Ron Lach on Pexels.com