Geri Schear's Blog, page 5

February 18, 2025

Tunnel Vision — Part II

Last week I said all I needed about how tunnel vision can impact your writing. Or so I thought. Later, I had a conversation with BFF Jane, and she pointed out some things that I had missed. What, she said, would a child narrator be expected to see? Or someone with mental illness? She offered many other examples. How bloody annoying — but I had to admit she was right.

So, what are the advantages of tunnel vision, and when should a writer use it?

The example I gave last week of the woman hearing footsteps coming up to her bedroom still stands. Any time the character is completely focused on one thing, then you should avoid any extraneous details. Keep it to those things the woman will be focusing all her attention on. And at the risk of stating the obvious, she’s not going to be thinking about her ‘heaving bosom.’ No, really. And don’t try to get around it by writing something like, “She didn’t even notice the sweat trickling between her heaving bosoms.”

Jane’s example of a child’s point of view is pertinent. While some, depending on their age, may be astute enough to see fairly broadly, they are unlikely to anticipate outcomes or consequences. I’ve watched a few videos of children being given hefty sentences for murder, and their shocked reaction is often, “I didn’t know this would happen.” However, a child will look at situations from the perspective of how it impacts them. I didn’t realise when I ate all the doughnuts that there would be none left for the rest of the family. I didn’t think that mum’s car crash would mean that I would have to live with my aunt for a few months.

Some writers do a very good job of capturing the way the child’s mind works. Harper Lee is one of the best examples. Even though her character, Scout, (To Kill a Mockingbird) is too young to realise the danger her father faces by defending a black man from a charge of rape, she conveys all the necessary information that allows the reader to see the potential consequences even though the child cannot.

Another example worth noting is the character who suffers from some sensory deficit. Perhaps he is blind. How does that impact his relationship with the world, or with other people? In The Heart is a Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers, the protagonist, John Singer, is deaf. This disability impacts how the people around him relate to him.

A person living in isolation, regardless of the reason, is also likely to have a limited ability to react to the world. Obviously, Robinson Crusoe has a wider world to consider than a prisoner in isolation, but both perspectives are limited to some degree.

As a writer who does not currently suffer any such disabilities, I find it a challenge to imagine the world as it must seem to a person who cannot see or hear. And yet these challenger are, for me, one of the joys of writing. Being able to enter such a different world and inhabit it, to develop a real appreciation for the things some people endure. To see the world through another’s eyes (or not see, as the case may be) is a privilege.

Then there’s delusional thinking. This has downed more planes than hurricanes. Well, I don’t know if that’s true, but I do know it’s a lot. How many times have you heard that the pilot thought he was flying in the right direction to the airport, only to crash into a mountain? Or he thinks he’s at a safe altitude, but it transpires that he’s flying upside down and so he plummets into the sea? People can be delusional about all sorts of things. The shadow of a tree on your bedroom wall can be taken for a monster. The wife of the man across the street is on holiday; her husband hasn’t bumped her off and buried her in the garden. (Take note, Alfred Hitchcock.)

I recently watched William Peter Blatty’s The Ninth Configuration. It’s an excellent film about a group of Vietnam soldiers who appear to be insane. They are being treated in a gothic-looking castle that is always pictured in rain or fog. A forbidding looking place. At the end, one of the characters returns, and we find it is actually a warm and welcoming building, surrounded by flowers and trees.

Delusions. What a great concept for a story.

My final example here is the person suffering from mental illness. I’ve worked in a mental facility during my nurse training, and later in a facility for educationally challenged people. I am in awe of people who manage to cope with these difficulties, as well as those who care for them. Trying to get inside the world of such people is a real challenge, but think what an outstanding novel you could produce if you could manage it. There have been, of course, many books and films about people dealing with mental illness. Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway, Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, and Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar to name some of the more illustrious examples.

In a nutshell, then, if the character or the circumstances reveal a narrow perspective, then that’s the way to go. I will say, though, that some of these books can make for tough reading, especially the ones dealing with mental illness. Perhaps that’s just me because I’ve seen some of these conditions up close and they continue to haunt me.

Ideally, at least in my opinion, a book should present a combination of both the narrow focus and the broad spectrum. Obviously, there are times when either one will suffice. But it’s your world. The world you created and inhabit. Have fun with it.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." data-large-file="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." width="1880" height="1253" src="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." alt="" class="wp-image-17974" srcset="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 1880w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 150w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 300w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 768w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 1024w" sizes="(max-width: 1880px) 100vw, 1880px" />Photo by Joyce Dias on Pexels.comFebruary 11, 2025

Tunnel Vision

I was watching a TV ad the other day and it hit an easy ten on the cringe meter. It’s for some security company or other and it goes like this:

Bubbly spokeswoman: “I ran into Jean today. Her house was burgled.”

Older woman: “Thank goodness I have XYZ protection.”

Bubbly spokeswoman: “You should tell her about it. It might give her peace of mind.”

Now, I realise it’s just a commercial and not Shakespeare, but normal people don’t speak like this. I mean, if I told you a friend’s house had been burgled, wouldn’t you ask how she was? Was much taken? Wonder how you might help? Okay, if you’re a total narcissist perhaps you’ll do the whole, I’m all right, Jack, sort of thing, but even a cunning narcissist will at least pretend concern about their friend.

So, if you were asked to write this scene, still with the idea of promoting the product, while making the dialogue more realistic, how would you do it? Here’s my attempt:

Bubbly spokeswoman: “I ran into your friend Jean today. Her house was burgled.”

Older woman: “Oh, no, poor thing! How can we help?”

Bubbly spokeswoman: “I told her about XYZ. She seemed very relieved.”

I know, that’s not Shakespeare either, but at least it’s a bit more credible than the original. And to be honest, the wicked streak in me (a mile long at last count) would go more like this:

Bubbly spokeswoman: “I ran into Jean today. Her house was burgled.”

Older woman: “Thank goodness I have XYZ protection.”

Bubbly spokeswoman: You should tell her about it. It might give her peace of mind.”

Older woman: “Oh, I can’t be bothered. I can’t stand Jean!”

Bubbly spokeswoman: “Mother!”

I know it’s wicked, but I bet you wouldn’t forget it. But to get back to the topic…

A lot of us tend to focus on one tree when we should be seeing a forest. We get so caught up in non-essentials that we lose sight of how our writing reads to other people

The other day while in the shower, I started mulling over three songs that have one thing in common. However, one of those things differs in one specific matter. (Cue Sesame Street song: One of these things is not like the other…) I’m going to list the songs and give you time to either read the lyrics, or recall them to mind. I’ll return to this further on, but I want you first to think about what the common thread is, and how one differs from the others. Ready? The songs are:

Coward of the County by Kenny RogersGypsies, Tramps & Thieves by CherIndiana Wants Me by R. Dean TaylorLet’s get back to tunnel vision.

There are times when it is necessary. When you need the sort of focus that shuts out all the irrelevancies. Imagine a woman waking up in a dark room in the middle of the night. She hears footsteps coming up the stairs, though she lives alone. Is it a killer? A burglar? A ghost? Whatever it turns out to be, her entire being is focused on those footsteps. In this scenario, the writer should be focused too. We don’t need any extraneous details such as her ‘heaving breasts’, or whatever she’s wearing. Our focus, like hers, should be on survival.

These scenarios are relatively few, of course. A whole book of these incidents would be a chore to read. Most of the time we want to be able to build a picture in our minds. Where are we? What time of day is it? Is the ambience welcoming or not? What does it smell like? Yes, smell. All these things that our brains notice albeit on a subconscious level. We’re not in a tunnel now. Time to look around and smell the roses, the coffee, or the incontinent cat. Bring the scene to life.

But there’s another aspect to tunnel vision I want you to consider. Buckle up, friends, this is where we talk about the music.

If you’ve taken the time to read or listen to the lyrics of the songs I listed, I wonder what struck you about them. The first and third are about a man taking revenge for his wife being violated and / or murdered. In both cases, despite the woman being the victim, the song is all about the man and his suffering. The woman is nothing more than a MacGuffin (this is “an object, event or character in a film or story that serves to set and keep the plot in motion despite usually lacking intrinsic importance.” according to the Merriam-Webster dictionary.) In other words, the male writer of these songs is looking to making himself seem heroic. The woman is nothing more than a convenience that allows him to do so.

In the Cher song, however, she is the main character and she is the subject of an assault — “Papa would have shot him if he knew what he’d done.” The character gives birth to a baby and life goes on. We know little about the boy who impregnated her, not even his name. All we know is that the Cher character is 16 and he’s 21. But we know enough about the girl’s parents and the girl herself. We even get a glimpse of the punters who, despite pretending they have higher ethics, will still “Come around and lay their money down.”

Now, I’m not trying to say that men are more likely to write self-absorbed fiction than women, only that it’s true in these songs. In fact, in Indiana Wants Me, the singer says he has a baby, but we have no indication of what will happen to this child. The wife and baby don’t matter, only the man.

Now consider one other song that takes more of a third-person point of view to a crime, that’s Smooth Criminal by Michael Jackson. We hear how the criminal broke in through the window and attacks the woman, Annie. Why he assaulted her, who he is, who she is, we don’t know. We just see the assault and the aftermath, “left bloodstains on the carpet.” And yet the lyrics are powerful enough to show us this event as much by what is left out as by what is said.

Now, these are songs, again, not Shakespeare, yet they tell us a fair bit about their lyricists. So, when you’re writing, think of Michael Jackson, and broaden your vision.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." data-large-file="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." width="1880" height="1058" src="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." alt="" class="wp-image-17950" srcset="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 1880w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 150w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 300w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 768w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 1024w" sizes="(max-width: 1880px) 100vw, 1880px" />Photo by George Becker on Pexels.comFebruary 4, 2025

5 Ways to Avoid Information Dumping

What do we mean by information dumping? It is just what it sounds like. You have a big chunk of information about something or someone, and you write it into the story in one big lump.

Why is it a problem? Because it’s boring. People skip over those pages or, worse, they skip the entire story. Even if your style of writing is generally entertaining, info dumping is a hard sell. It’s much better to find another way to feed us that information.

When are we most likely to use info dumping? The first is when we want to explain everything about one of our characters. The second is when we have some sort of technical or historical information to impart. Yes, I understand. But there are better ways.

The Trickle ApproachYou don’t have to load us up on backstory all in one lump. Let it come out in small amounts over several pages or chapters.

One of my favourite TV shows is ‘Would I Lie to You?’ on BBC. Two teams of three take turns relating events or situations that they claim to have experienced. The other team has to decide if the contestant is lying or not. One of the difficulties for the team member telling the story is that they have to read the events from a card. If the story is untrue, they have to make up the details on the fly as the other team asks questions. I bring this up because one regular contestant is comedian Chris McCausland. He is blind, so isn’t able to read the cards. He handles this by handing the card to the team captain saying, “Still blind.” The fact that it’s so succinct is why it’s so funny.

Just a tiny snippet of information that hints about an incident in a character’s past, or some obscure detail about a town or some historical event can add colour to a scene, and serve as a warning or a hint of things to come. The Daphne du Maurier novel, My Cousin Rachel, opens with this line:

They used to hang men at Four Turnings in the old days. Not any more though.

The shadow of that bleak past falls on the events of the tale that follows. No, I won’t spoil it by saying any more. Good book. Read it.

If you trickle information into chapter one about the heroine’s ‘unfortunate history’, but don’t specify anything about it, you’ve captured the reader’s attention. Maybe a few chapters later, you see her throw things in a temper tantrum. Hmm, maybe that’s why she has that reputation. And several chapters after that someone is cautioned not to trust the heroine. They don’t want to say why, but hint that it’s something terrible. Then, perhaps, a child dies and now the backstory is told: a child once died in the heroine’s care. She claims it was an accident, but you know how people talk… You really don’t need much more than that.

Can you see how this is more likely to keep the reader’s attention, rather than telling us all this back story on page one?

Data in DialogueOne of the advantages of writing a detective novel is your detective is expected to ask questions. This is a great way of revealing information. Also, don’t forget that some information may be tainted. People forget to add important details, or may not know the whole story. Human biases also come into play.

Even other types of stories allow for information to be revealed in dialogue. “Tell me, Ted, how did you lose your arm?” Maybe Ted will answer truthfully, but perhaps he’ll tell a different whopper every time the question comes up. “I woke up one morning and it was just gone.” “A bear ate it.” “A boomerang ripped it right off…” His humour is far more interesting than the mundane facts might be.

Of course, if the details are essential to the story, you can still reveal them in the dialogue.

“Hey, Ted, why are you using the XYZ revolver? Doesn’t it have a reputation for freezing?”

“I’ve had this one a long time and it’s never let me down. Anyway, it only freezes when you don’t keep it lubed. That’s not a mistake I’ve ever made.”

And before you say it, no, I don’t know anything about firearms. You’re right. It shows. The point, though, is revealing information in dialogue can tell us as much about the speakers as about the person or issue they’re discussing.

Information in ActionListen, you could spend three pages about how many times your character’s hair-trigger temper got him into trouble. Or you could just write a scene in which he explodes for no good reason. Likewise, you could give us a chapter on the history of sailing and explain in detail how to tie an anchor hitch. Or you might show us a sailor in action, watch him as he effortlessly ties his knots, and weave some of his character into the way he completes his tasks. Perhaps he’s old and his fingers are arthritic, but they have, as they say, lost none of their cunning.

Separating a character from your story is always something to be wary of. By this, I mean describing an event or an activity in a dispassionate manner. The kind of thing that sounds like some Public Broadcast documentary: “And now we see the blue whale gliding gracefully through the azure Pacific waves.”

Please.

The activity is fine, but we read for the characters, not for your poetic indulgences.

In my current novel, Great Warrior, a young woman is found dead on a London street. The novel opens with the police notifying the woman’s aunt, Mrs Hudson (Sherlock Holmes’s landlady). Over the next few chapters the reader learns that the dead woman, Meg, had been a nurse serving in South Africa during the Second Boer War. As the story progresses, different people offer their stories about the war and the role of nurses in it. Gradually, a picture of Meg’s life in South Africa emerges. Through it all, we see Holmes and Watson react to the information, worrying about their grief-stricken landlady, and feeling distressed by the violent death of a young woman they both knew.

Mystery writers are used to letting details bubble up to the surface at their own speed, but where we sometimes fall short is in showing the emotional connection to that information. Even something that is done automatically, driving a car, for instance, can demonstrate the character’s competence (or lack thereof) as the driver shifts gears and weaves through traffic. That information tells us something about the character, and may, in a mystery, turn out to be a clue.

Inserting News Items or Relevant ArticlesOne of my favourite Agatha Christie novels, A Murder is Announced, starts with a newspaper item: “A Murder is Announced’ it says, and, sure enough, a murder happens.

Some stories gain background information by including letters, diary entries, news articles, and so on. Stephen King’s first novel, Carrie, includes a lot of ‘news’ items about the Carrie White events.

In Great Warrior, I used diary entries, letters, a journalist’s reports to reveal the backstory.

In addition to presenting information that the reader needs, news items and so forth also add a feeling of authenticity to the story. Furthermore, it allows the author to completely change the tone of the story to something more akin to reportage.

My only caveat with this option is that a little goes a long way. Two or three paragraphs should be sufficient. If you need more, then I’d intersperse the ‘reports’ with dialogue and comments from the characters.

Skip ItBefore you try to figure out how to weave the information into the story, ask yourself this:

Does it matter?

Do your readers really need to know the weather conditions of the small town that your characters pass through? Do they need to know about your 40-something year old hero’s time in kindergarten? Or their summer holiday when they were twelve? Maybe there is some connection with the scene, but tell us the essentials. ‘John was struck by the scent of mimosa. It reminded him of his time in France when he was twelve…’ That’s enough. In fact, if the holiday is irrelevant to the story, I’d probably just have him smile at some unspoken memory. Mystery always trumps too much information.

The same goes for technical information. Yes, some authors love showing off their knowledge of computers or guns or whatever, but you’re not writing a text book. Unless there is an aspect that is pertinent to the story — say this particular weapon has a known flaw and this causes the gun to fail at a key moment — just give us the essentials that we need to understand the scene. I’ve already shown in the dialogue section how this gun issue could be handled.

PS: If ‘Would I Lie to You’ sounds like your sort of entertainment, it’s available on the BBC, and clips are on YouTube.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." data-large-file="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." width="867" height="1300" src="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." alt="" class="wp-image-17920" srcset="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 867w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 100w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 200w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 768w" sizes="(max-width: 867px) 100vw, 867px" />Photo by David McElwee on Pexels.comJanuary 28, 2025

Do Writers Need Role Models?

One of the few advantages of working in an office is the increased chance of finding a positive role model. People who work in academia may be similarly blessed. For those of us who spend our working days sitting at a desk facing down the impersonal blueness of the computer screen, finding any sort of human contact is difficult, much less one that would serve as an inspiring role model.

Even (now) famous writers have relied on their peers for support and feedback. Wilkie Collins was a friend of Charles Dickens, and there’s no doubt that the older and more experienced Dickens was an exceptional mentor to the Moonstone author. Centuries later, PD James and Ruth Rendell (also known as Barbara Vine) were close friends and allies.

Lucky is the writer who finds a peer who can help him along. If you attend a creative writing class or participate in a writers’ group, you may well find a kindred spirit there. Perhaps you are the only pair who love Lovecraft, or get your kicks with King. A role model doesn’t have to be way ahead of you in the writing world. You can learn a lot from combining information with your peers.

That said, if you are lucky enough to have a dynamic leader of your group or class, or if a successful author is a family friend or neighbour, you may strike the jackpot if they agree to offer you advice and feedback. Unfortunately, all these possibilities may be a pipe dream for many of us.

So, what are role models good for, and can you do without them? The ideal role model fulfills the following functions:

An example to emulateSomeone to discuss difficulties withA cheerleader for when things get toughCan you do without them? Probably, but as Bogie might have said, it’s better to have than have not. (Or something like that.) Writing a novel without anyone to give you honest feedback is hard. We can’t always see our own mistakes. That’s why they call them ‘blind spots’. It also helps to watch how someone you respect handles things like book launches, lectures, and many of the other non-writing tasks that we are often required to do. I should add, too, that seeing a famous writer behave badly at such an event can be a lesson of a different sort. We also need people to pick us up when we’re down. Your best friend who tells you that agent who rejected you is an idiot. Or that someone with your talent is going to make it big and they can’t wait to see it happen.

This is a lot to ask of one human being, but, fortunately, you may be able to spread these roles over a number of different people.

You don’t need to have a personal relationship with someone to try to emulate them. I’ve never met JK Rowling, but I’ve seen how she handles herself in public events. I see the compassion she has for children, and the enthusiasm she shows for her writing. I also like watching Stephen King interact with fans at conventions and book signings. I take bits that I like from my A-list group of authors and I try to follow those behaviours I most admire.

While having a professional author with whom you can discuss your writing and the issues you may be having is the optimal, any friend who is a good reader can offer invaluable feedback. In fact, they may be better judges, especially if you write in a genre they are well versed in. Unlike a fellow writer, they won’t be jealous that your writing is better than theirs.

The same good friend can also be your cheerleader and advocate. Just be grateful that you have them and remember to include them in your acknowledgements.

Finally, if you are lucky enough to find one (or three) individuals to serve as your role model, don’t mess around. Respect their time and their point of view. Telling people that they don’t know what they’re talking about is no way to nurture a relationship. It’s a good way to destroy a friendship, and to ignore what may well be excellent advice. Also — I say this from being on the receiving end — if a writer gives you advice and suggests ways you might rewrite a scene, don’t try to con them into doing it for you.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." data-large-file="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." width="1880" height="1254" src="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." alt="" class="wp-image-17907" srcset="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 1880w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 150w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 300w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 768w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 1024w" sizes="(max-width: 1880px) 100vw, 1880px" />Photo by Kampus Production on Pexels.comJanuary 21, 2025

How to Handle Those Uh-Oh Moments

I recently started a new book. I had been thinking about the opening for more than a month. I knew it would be complicated because it means introducing several characters and there are two murders before the story even begins. Still, I thought I’d figured it out, and a week or so ago I sat down to start work.

It is not going well.

Don’t misunderstand me, it isn’t awful. Even the bits I’m dubious about are beyond repair. All the same, I’m used to my stories flowing pretty well once I start writing. This isn’t happening this time. The writing seems full of knots and tangles, and I am, as you can imagine, frustrated.

I have posted previously about just moving forward. Leave yourself a note about what’s not working and, if you have them, some ideas for fixing the problem, and then return to it in your rewrite. Sometimes, though, if the mess is messy enough and, more importantly, if it is going to take your story in an entirely wrong direction, you may have to stop where you are, and go back to where the story was last going the right way, and begin writing again from that point. But as you will see, that’s not always the best thing to do. Sometimes just moving forward is best.

But before you do anything else, you need to analyse your writing and try to figure out what has gone wrong. Here are some possibilities:

You picked the wrong point of view / narrator to tell the storyThe tone of the story is offThe pace doesn’t workThe plot is a messThe good news is all of these problems can be fixed, and all but the first can be corrected in the second draft. The bad news is that the fixing will take time, concentration, and possibly cutting a big chunk of your story to get back on track. Obviously, you want to be very sure that you have correctly identified the issue before you start to work on fixing it.

Point of View (POV) / Narrator

Let’s suppose your story involves a murder mystery. What are your options for point of view? The most common choice is the detective who is investigating the case, but many excellent novels have been written from the point of view of a witness, or friend of the victim. Then again, one famous movie told the story from the perspective of the victim himself. And one famous novel is narrated from the point of view of the killer, although we don’t know he’s the killer until the end.

Ideally, your POV character should have access to plenty of information about the victim and the crime. However, leaving them with gaps in their information can make him or her an unreliable narrator. These can make for a very interesting narrative.

Of course, you don’t have to go with the first person. You could opt for third person, either limited or omniscient. If you have a number of scenes involving a variety of characters, then third person might be best.

I once deleted 30,000 words of a story in progress because the POV was wrong. It broke my heart, but it had to be done.

If I were approaching that issue today, I’d probably keep those 30,000 words and write the next chapter from a different point of view, or with a different narrator. Later, I can decide which works better. Some modern novels use a number of narrators, with each bringing his or her own perspective. John Connolly, for instance, writes his book with some chapters written the first person, and others in the third person. Perhaps something like that might work for you, too. It certainly beats cutting a big of your work, right?

Tone

Something that’s harder to nail is the tone. Some writers use the same tone for everything they write. It might be light and breezy, or it could be intense and full of foreboding. It isn’t necessary to use a dark tone in a murder mystery or any other dark topic. Sometimes, a light tone can work well even with the darkest of topics. See Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five about the bombing of Dresden as an example of a jovial tone despite the subject.

What establishes tone? A number of things: your attitude towards the character. Do you condone their bad behaviour? Try to keep impartial? Or write an undercurrent of tutting throughout the story? Things like your word choices can suggest your attitude. For instance, you could describe a character’s smile as genial, smug, or thin-lipped. How would the reader react to each of these choices? A group of men are planning to rob a casino. Do you describe them as clever, deadly, or inept? Can you see how this attitude will impact the overall tone of the novel?

Also, don’t forget that the tone of the story will change based on the events. A party may be told in light and frothy terms, but a war or a crime is full of darkness and bloodshed. If you want some examples of tone I’d suggest some short stories such as, Hills Like Elephants (Hemingway); You Should have Seen the Mess (Muriel Spark), or The Ones who Walk Away from Omelas (le Guin). Then there are a couple of speeches from Shakespeare, such as the St Crispin’s Day speech from Henry V, and the Friend, Romans, Countrymen speech from Julius Caesar that depict how a crowd can be manipulated by clever words.

Pace

Pacing is tricky to master. If you cram too much information into one paragraph, the reader won’t remember much of it. They will become confused, and may end up not finishing the book.

On the other hand, if you belabour the details, spend an age giving us irrelevant background information, for instance, you’re slowing down the action of the story. If this was 1825, you might get away with it, but not two centuries later.

Ideally, a novel should have a fairly consistent pace, but scenes of high action — a car chase, for instance — should be faster. How do you do that? Short sentences, short paragraphs, with little introspection. Some writers will include things like the hero’s heart beating faster, or feeling the sweat on his brow, but with adrenaline pumping, people don’t notice these things. You might even have heard soldiers or victims of violence saying things like, “I didn’t even realise I had been shot until later…” You might have the hero spit because of the metallic taste in his mouth: the taste is the result of the adrenaline rush. Of course, he doesn’t realise he’s even done it until later.

Read some action stories to get a feel for how these scenes are handled by the pros. Ian Fleming, CS Forester, and Michael Connelly write some excellent action scenes, so perhaps you might give them a try.

Alternatively, you don’t want your novel to be all fast-paced. It would be exhausting to read and, besides, a story is more interesting with peaks and troughs of action. Give the hero or heroine time to regroup, to review the events, to plan for whatever lies ahead.

I tend to pace too quickly during my first drafts. I rush events along like I’m in a race. By the second draft, I’m ready to take my time a bit more. Let the first murder settle. Let the characters react, grieve, and discuss the events. Then you can give us the second murder.

If you are worried your story is paced either too fast or too slow, just stay with it for the first draft. When you get to the first rewrite (yes, I said first. Suck it up, champ!) you can fix it.

Plot Issues

This is the really tricky one. It’s all too easy to get your plot into a muddle, but not so easy to fix. It’s like trying to untangle a knot, and requires just as much patience to fix. Here’s what I do:

Even if you don’t want to write an outline, at least create a list of events. Ideally, they should follow a cause-and-effect format. Consider this as an example:

Because the girl was left a house in a will, she left her London flat and moved into the house in Cornwall, for instance. Because of that, she discovers the house is haunted. Because of that, she meets and attractive paranormal investigator, (are there attractive paranormal investigators?) and so on. But, wait! Why was she left the house, and by whom? Who owned it before? Why did they leave it to the girl?

These ‘because’ items as well as the questions form your very basic draft. Now, you don’t have to follow this list in an A to Z fashion. You could start where she wakes up in the middle of the night and sees a ghost, or thinks she does. You could write some of the story in flashback. Or you could begin with her being a child visiting her Cornish aunt over the holidays.

Having a list is helpful because not only does it help remind you of all the cause-and-effect, but you can also decide what way you want to relay these events to your reader.

If you have placed an event too early in the story, you can cut it and move it to a separate folder and slot it back in when the time comes. That said, I often find that the original version doesn’t work later because many elements that it contains have been described or introduced earlier. Still, it can prove helpful as a way to create the scene.

Finally

If your story looks a mess, should you stop and fix it, or just keep going?

As you can see from the above, most issues that you find in a first draft can be corrected in subsequent drafts. Unless your story is irrevocably going in the wrong direction, you should probably keep going. In fact, even if it is going in the wrong direction, you may find yourself with a better story by the end. I’m a strong believer in the power of the subconscious to find avenues for your story that your conscious mind might not have thought of.

And, to leave you with a happy thought: By the time you finish that first draft and start on draft two, you will be a better writer. You have all that practice behind you that you didn’t have when you started. Now, you’ll see different ways to structure a scene, to write a sentence, and to develop your characters. A bad first draft is not only acceptable, it is almost expected.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." data-large-file="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." width="867" height="1300" src="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." alt="" class="wp-image-17889" srcset="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 867w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 100w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 200w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 768w" sizes="(max-width: 867px) 100vw, 867px" />Photo by Ron Lach on Pexels.comJanuary 14, 2025

5 Ways NOT to Start your Novel… Plus Some Exceptions

One: With the daily routine.

You’ve seen this before. The hero or heroine wakes with the alarm clock, thinks about what they’re going to wear; then shower, dress, etc., and by page 20, they finally close their front door behind them. This always smacks of ‘throat clearing’. The writer doesn’t really know what’s happening in the story, but they figure some idea will present itself as they keep on writing. Plus, they can tell their friends they’ve written 5,000 words, or whatever. There are, however, a couple of problems with this. In the first place, no reader is going to stay for long with a story where nothing happens. And, secondly, the writer is eventually going to have to come up with something that smacks of a plot. Some threat or action to start the story for real.

The exception: The only time you should consider giving us a small glimpse (accent on small, my friends) is when something significant has changed. A Twilight Zone sort of thing where the hero discovers he’s been captured by aliens and they’re watching his every move. Enjoy that shower, mate! On perhaps the woman has had a mastectomy and has to get used to the change in her self-image. Now her clothing choices take on a new significance. Even here, though, don’t take it too far. A page or two at most.

Two; With dull exposition.

Give us a dozen or more pages on the history of the American Civil War, its cost both in terms of lives and of finances. Then go on to tell us who designed the buildings of a particular town. The impact he had on the agriculture of the area, and then skep ahead a few generations to tell us about his descendant who is, at last, the hero of the story.

The exception:

Only go this route if it’s a) pertinent to the plot and b) unusual enough to warrant mention. For instance, Davy comes from a long line of wizards. He was (accidentally) blowing things up as an infant, even before they gave him his first wand. A brief review of how his ancestors all came to a bad end because of their wizardry may work if you can make it witty enough.

Three: With the weather

Yes, Dickens got away with it — see the opening of Bleak House — but that was a few hundred years ago. A more patient time where readers were not distracted by computers, TV, or any of the other trinkets of modern life. Telling us in tedious detail about global warming and various meteorological trends is well, dull. It tells us nothing about the characters or the challenges they’re facing.

The exception:

If some aspect of the weather is the crux of the conflict, then a small snippet of information may be interesting, as long as it hints at the chaos to come. Imagine you were writing a story about a volcano that suddenly erupts in a small town in Nebraska. You could open with a paragraph about

Little Plow, Nebraska, population 1608, boasts one of the most ignored dormant volcano in the midwest. Of course, everyone knows that one day Holy Smoke, as it’s affectionately called, will someday erupt.

What they don’t know is that day is today.

With this example, I would we be inclined to put this in the first person and have the narrator talk about the population of the town and add that he, his wife and children, his parents and his grandmother, make up the eight of that 1608. And then go on to talk about the volcano. This might be particularly powerful if you use the number eight in the title, And Only Eight were Saved, or something.

Four: With a character or incident who is never heard from again.

Listen, it happens. Sometimes we think of a character who seems really interesting and we start off gung-ho about him. But five pages later, we realise he has no legs (metaphorically) and we move on to someone more interesting. You might get away with it if the character dies and that impacts your hero in some way, but you really shouldn’t spend time describing some character in detail and then just forget about him. No one wants to come to the end of a book saying, “But, what about…?”

The exception:

You can keep this character’s secrets until the end, if you like, but you still have to make him relevant to the story. Perhaps he was a criminal who changed his name and is now the judge or even the hero. Perhaps he died in a mine and his body is found surrounded by gold. Perhaps he is symbolic of the evil or even the virtue to one of the main characters. One thing you can’t do is forget about him.

Five: With a description

Listen, it doesn’t have to begin with ‘it was a dark and stormy night’ to be bad. Description has its place, sure, but not at the beginning, not before there’s a story established. Yes, we want to know the setting of the story, and have some idea how various characters are perceived, but here’s something to remember:

Description is static. Plot is movement.

Several pages of flat description are not only boring, but add nothing to the plot. One of the worst examples of this is the hero who is studying himself in the mirror. This one is such a cliche, it’s laughable. The man examines himself in the mirror. Notes his strong jaw, his glossy black hair, his excellent posture, style, etc., etc. Please don’t do that.

The exception:

The best way to describe a character is to show them in action. This way you are un-static-ing the description. Think, for instance, a description of a flirtatious blonde. Yes, she’s beautiful, but we know nothing about her. Now think of the same blonde pulling off her bikini top and tossing it aside before she jumps off a cliff into the sea below. That got your interest, didn’t it?

Show us the character through the eyes of other people, preferably doing something very ‘him’. Perhaps he’s conning old people out of their money. Maybe he’s bullying a kid half his age and size. Maybe the heroine is being absolutely adorable. Now the story has a pulse.

Final Caveat:

You can break almost all the rules if your writing is witty, Few writers could match the late Douglas Adams for wit. Here’s his opening to The Restaurant at the end of the Universe:

The story so far: in the beginning, the universe was created. This has made a lot of people very angry and been widely regarded as a bad move.

Or you could deliver a punch of a different kind as Sylvia Plath did in The Bell Jar:

It was a queer, sultry summer, the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs, and I didn’t know what I was doing in New York.

There are many other examples. Some thought provoking, some fear-inducing, some puzzling, but the idea of the opening is to keep us reading. Do that,

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." data-large-file="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." width="1880" height="1254" src="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." alt="" class="wp-image-17873" srcset="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 1880w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 150w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 300w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 768w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 1024w" sizes="(max-width: 1880px) 100vw, 1880px" />Photo by David Kanigan on Pexels.comJanuary 7, 2025

How to Build a World

Hello, my friends. It feels great to be back to my usual routine. With this being the first post of the year, it seemed a good time to talk about world-building, and why it matters to novelists.

When I first heard the term, I thought it was specific to science fiction and fantasy. After all, I reasoned, if you set your story in the ‘real’ world, then you don’t need to create a world of your own. I later learned that the concept of world-building applies even to the most realistic of novels.

Think about your family. Once you are in your house together and the door closed, certain behaviours and patterns are accepted without question. When I was a child, the big black armchair in the corner was ‘daddy’s chair.” Sure, we could sit in it when he wasn’t home, but the minute he walked through the door, that seat was vacated for him. My dad was very old-fashioned, so he called all his daughters, ‘darling’, and on the rare occasions that he swore — ‘damn’ was about as bad as it got — he would apologise immediately. So many little customs that developed over the years, mostly without us even noticing. It was only when we went to friends’ houses that the differences caught us by surprise. This father swore incessantly, that husband not only beat his wife, but encouraged his sons to do so, too. This mother was always drunk, and that one smelled bad. Some houses were spotless, and others were filthy.

Your home is your world. Especially when you’re a child and have little say in how things are done. Whether we look back on those years with happiness or anger, they remain a part of who we are.

All families have their own internal rules. Sorry, Mr Tolstoy, but all happy families are not alike. The personalities, ages, finances, and geography will impact each individual and how they impact one another. I would add, too, that it’s perfectly possible to be miserable in an otherwise happy family.

When you start writing, you seldom think about the world in which your characters live, unless your story is set in another universe or a different planet. But if you are writing about a specific time and place here on planet Earth, you may not give the matter much thought. However, even stories set in the ‘real’ world have to follow certain rules.

Suppose you are writing a story set in 1972 in the US. Your hero is 19 and he has nothing on his mind but girls, cars, music, and girls. You write your whole story about this young man and you figure you did a good job with it. But, whoops, what about that whopping great elephant filing his nails in the corner? The one called Viet Nam. In that time, in that place, no man of that age would be able to ignore the draft and the odds of being called up. Now, you could write the story, still focusing on that young man, and not mention the events of South-East Asia. But maybe the young man is reckless and it’s not till the end, when he has to leave his home and join the army that we understand his behaviour.

The point is we all live in the larger world, just as much as we do in our intimate home-based world, and we cannot ignore the events happening outside our door. As I write historical mysteries, I always check what historical events are happening during the period in which my story is set. Not just the big events like death of Queen Victoria, but less obvious things, like the first motor-car related death, or setting up telephone lines around the country. For example, one of the threads that runs through my most recent book, Great Warrior, is the Second Boer War and the way it impacted people in England, even if they were non-combatants.

When you sit down to create the world in which your character lives, you need to think of all the components: the weather, the geography, the socio-economic status of the characters, their language and customs, and so on.

As you are writing, you need to keep the story consistent with that world, unless something happens to radically change the status quo. For instance, The Railway Children (1905) begins when the children’s father is arrested and they can no longer live in their comfortable house. They have to move to a cottage in Yorkshire and adjust to an entirely new world.

In an early, unpublished, novel that I wrote, I had a character who had been gifted with foresight and visions. However, when the story began, that gift had somehow vanished, and part of his problem was learning to adjust to his new ‘ordinariness’. What made his situation worse was that none of his friends or colleagues had ever experienced that gift, so they couldn’t understand his anguish.

What you can’t do, though, is make a change in the middle of the story and expect your readers to be all right with it. If an English family suddenly starts speaking with a French accent, we will wonder why. We will wonder why a poor family suddenly acts rich, or if a mansion turns into a hovel.

One of my favourite actors is Dirk Bogarde, but he made a film I cannot stand to watch, and it’s all because the world in which the story takes place is a mess. The Singer not the Song, as far as I can make out, concerns a bandit, Anacleto Comachi (Bogarde), who rules a small town with violence and corruption. One gets the sense that the town is in Mexico, but that, like many other details, is uncertain. It could easily be any South American town, or even somewhere in Spain. It doesn’t help that Bogarde’s character speaks with a clipped English accent. His antagonist, an Irish priest, is played by English actor John Mills (with a dreadful fake Irish accent that comes and goes). What’s worse is, at one part of the film, just as we’re accepted we’re in the late 1800s, a sports car appears.

I won’t go on, but you get the idea. If we don’t know where and when the story is set, it’s going to be very difficult to get on with it. Not surprisingly, The Singer not the Song bombed at the box office.

The one big rule about world-building is to keep it consistent. If something changes radically, you must explain it. Whether your story is set in a small Mexican town in 1950, or in a galaxy far, far away, create the appropriate world and stick with it, unless you explain the changes to your readers.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." data-large-file="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." width="867" height="1300" src="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." alt="" class="wp-image-17843" srcset="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 867w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 100w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 200w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 768w" sizes="(max-width: 867px) 100vw, 867px" />Photo by Clive Kim on Pexels.comDecember 17, 2024

End of Year Thoughts to Ponder

So, it’s almost the end of 2024. How was it for you? Yeah, me too. A bit of this, a bit of that, a bit of the other. Still, with year’s end rapidly approaching, it’s time we think about where we are in our writing journey. Have we achieved our goals? Have we at least made progress? If not, how can we improve things for next year. Here are some things for you to consider:

How much writing have you done this year? I haven’t done as much as I’d like, but, then, I always say that. How much is enough? Still, if you’ve done as much as you reasonably could, I’d say you can pat yourself on the back. Maybe you could try to do more next year. I know I will.

What are you particularly proud of? Did you finish that short story you’ve been struggling with? Have a story accepted for publication? Finish a draft of your novel? Whatever your accomplishments, give yourself credit for them. There’s no point in regretting the path not taken, or the incomplete journey. That’s all in the past. What matters now is the future, and how you can do better. And, to be clear, there are many things in life you can be proud of. Not letting your psycho boss have it right between the eyes. Winning £20 on a scratch card. Getting a personal note on the end of a rejection slip. Small victories are still victories and we ought to celebrate them more.

What writing lessons impacted you the most, and why? Was it something you read, or a video you watched? What was it that appealed to you? Sometimes it’s more about the can-do attitude of the facilitator rather than the actual lesson. At the risk of sounding like Pollyanna, we need to look more for positivity. There’s more than enough gloom and doom to go round.

What changes have you made to your writing routine? Did they work? Will you continue or change them? It takes time for new habits to form, so don’t be in too much of a hurry to dismiss something that you have only tried a handful of times. If they payoff is worth the effort, well… you don’t need a better argument than that, do you?

What books have you read? Before you answer that, let me tell you this: a writer who doesn’t read is a like a would-be cordon bleu chef who eats nothing but chicken goujons and fries, so let’s try that question again: What books have you read, just over the past year. All right, I won’t scold, but I will say you must do better. I’ve read roughly 50 books in the past year and I know that I can do better.

Even if you only read one thing, did you learn anything from it? Have you got a reading list? If not, make one. Put on it all those books you’ve wanted to read, no matter what genre they fall into. Reading widely is as important as reading at all. My list includes classics of various nations, mysteries, short stories and novels, plays and comedies and dramas. All reading is enriching and teaches you something — even if it’s how not to do something. I’m looking at you, Mr Edward Bulwars-Lytton, arguably the worst writer in history.

Anyway, I’m taking a couple of weeks off, and I’ll be back the second Wednesday in January. Have a wonderful holiday, whatever you celebrate. See you next year.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." data-large-file="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." width="868" height="1300" src="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." alt="" class="wp-image-17833" srcset="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 868w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 100w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 200w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 768w" sizes="(max-width: 868px) 100vw, 868px" />Photo by cottonbro studio on Pexels.comDecember 10, 2024

Un-Muddling Your First Draft

So, let’s assume you have spent several weeks or months hammering out your first draft. You haven’t reread any of it, made any corrections, and have just kept going. Now is the time to face the mess and see what you’ve got.

If you’ve been writing by hand, you can just start reading, but if you worked on the computer, you might want to print out your pages. There are a couple of reasons for this. In the first place, you can take pages with you anywhere. You can sit on the train, or on the beach and work through it. Also, there’s a psychological boost to having a thick batch of papers that is your story. Regardless of the work you still have to do, you should be proud of yourself. You have finished your first draft. Well done!

The Reading

Now, start reading. No, don’t make notes, not yet. Just read. If possible, try to read the entire manuscript at one shot. Of course, that may not be possible, but even if you have to spread it over a few days, try not to take any days off. You want to keep the continuity of the story fresh in your memory.

You will itch to start making corrections as you go along. Resist that temptation. Your job right now is to simply read and absorb the story you have created. You also need to resist the urge to make notes about your reading at the end of each session. Save it. The time for notes comes after you’ve read the entire manuscript. Only then can you get a feel for how the whole story fits together.

The Notes

Once you have finished reading your story, get comfortable with a pen and notebook and write down your observations. The things you want to note are:

What worksWhat doesn’tPlot lines that go nowhereItems that need to be researchedRepetitions that need to be tidied upMost of these items are self-explanatory, but let me just clarify that last point. Sometimes, you may forget a passage you wrote the day before or a couple of days ago, and find yourself repeating it. This is surprisingly common. I’ve even encountered it in published novels. The other thing you need to note is favourite words. I’m fond on crunchy as in Autumn leaves or gravel. Also amber. I have no idea why, but until I realised it, they showed up in every story I wrote. Weird. However, now I’ve noted these rascals I take pains to reduce my usages as much as possible.

The Plan

Once you have written your notes. You need to decide how you will attack the mess. Here are your options:

Begin at the beginning. Go on until you reach the end. Then stop.

Focus on all the bad bits first. Cut them, move them, or edit them so they fit with the rest of the story.

Start with all the good bits. Edit them first and colour-code them so you know you’ve worked on them.

Rearrange all the scenes that may be out of place and put them in some sort of an order. While you’re at it, you may want to delete all those duplicate bits.

The Project Outline

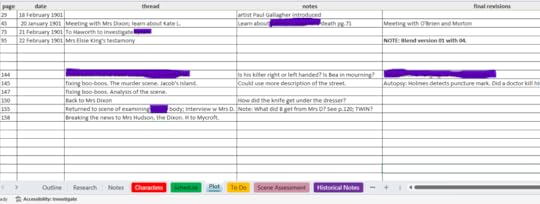

A novel is a big thing and it’s very easy to get lost in it. As I’ve said many times before, I like using a spreadsheet to keep track of my revisions as I go. Yes, it’s a pain to set up, and it does take time to keep it updated, but in my opinion, it’s worth it. Below is a sample from the revisions of my most recent novel, Great Warrior. As you can see, I note the page, the date the event takes place (because it’s historical fiction and some dates are significant). The thread means the specific item that needs attention. In addition to that, say, introducing a new character, I may note specific things I need to include. These items don’t necessarily mean I have to add those items immediately, but I need to keep them on my To Do list until I’ve either resolved them, or I’ve decided they don’t matter. One item below on page 144 asks if Bea is in mourning. This story begins not long after Queen Victoria’s death. Beatrice is the late queen’s goddaughter, so I needed to research how long she would be expected to follow the stringent Victorian rules of mourning. This update didn’t occur on page 144, but later. Once I’ve addressed an issue, I can cross it off.

Decide for yourself what items you want to include in your list. Perhaps you want to incorporate some of the elements of structure such as the act, inciting incident, climax, etc.

If you’re not the techy sort, you can create your own worksheet in your notebook. Alternatively, you can use Post-It notes. It helps if you have a big wall or at least some large space where you can, ah, post your Post-Its. The advantage of this approach is you can see where you are at a glance. Another advantage of this method is you can colour-code your notes by character, event, chapter, or whatever your preference may be. You can also move things around as you make changes.

One disadvantage, though, is this system isn’t portable, and it’s difficult to keep the information available after you’ve finished the story. I should add that I like to keep my template for the worksheet so I can use it again for future work. I can also use it to reference back for information on certain characters. This is particularly helpful if you are writing a series.

Different writers take different approaches to the Post-It system. If you want me to elaborate on this in a future blog, I’d be happy to do so. Alternatively, you can look up plot-boarding or how to do novel planning with Post-Its on Pinterest or other sites on the Internet. You’ll find more options than you can shake a stick at. Though why you’d want to shake a stick at them, I can’t imagine.

Some Don’ts

Your job here is sorting, so don’t spend too much time on each item. Your goal is to create a coherent storyline. It doesn’t have to be complete. If you’re missing a scene, for instance, just leave yourself a note where that scene should go with a brief explanation of the content. For instance, “This is where Joan tells Robert about Conrad’s shady past.”

Don’t mess with the grammar and spelling. You might spend hours fixing the language in a chapter, only to delete said chapter later. All your work has gone to naught. As a pedant, it pains me to say this. There’s nothing I like better than playing with grammar, punctuation, etc., but at this stage it’s like painting a building that’s due for demolition.

Don’t start any serious re-writing until you have your structure sorted. Know how your story begins, what they key plot points are, and how it ends. This is where that 3-Act Structure comes in handy. If you want more information on how to structure your novel, see my previous post here.

Finally, good luck with sorting out the story. I know it can be tricky and time-consuming, but you’ll feel very good when it’s done and you’re able to devote yourself to the more fun aspects of the rewrite.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." data-large-file="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." width="1024" height="682" src="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." alt="" class="wp-image-16894" srcset="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 1024w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 150w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 300w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 768w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 1880w" sizes="(max-width: 1024px) 100vw, 1024px" />Photo by Ron Lach on Pexels.com[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." data-large-file="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." width="867" height="1300" src="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con..." alt="" class="wp-image-17808" srcset="https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 867w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 100w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 200w, https://rycardus.wordpress.com/wp-con... 768w" sizes="(max-width: 867px) 100vw, 867px" />Photo by cottonbro studio on Pexels.comDecember 3, 2024

Just Do It

Last week, I talked about writing a quick first draft. Today, I want to look at that process a little more closely.

Some of the things you do when writing a speedy first draft are no different than when you write anything else. Set aside a specific time and place in which to work. Pick a time when you have the space to yourself. Avoid any interruptions or distractions. Keep all this in mind as we look at some ideas for taking a deep dive into your fictional world.

Get comfy

Before you begin, make sure you have everything at hand that you’re going to need. Adjust your seat, desk, lighting, etc. so everything works for you. You don’t want to lose your train of thought by getting a back pain because your chair is an, uh, pain. Adjustable chairs are great, but cushions can be helpful too, if you need back support.

Yes, you can wear your lucky hat if you need, but if you find you have to keep adjusting it, you’ll have to learn to do without. Maybe just put it on the shelf so it can smile benignly at you as you create your masterpiece.

Avoid distractions

Do not bring snacks, drinks, or anything else that may distract you into your writing area. Most of us will think about what happens next while we dip our coffee. The idea here is to move quickly. Don’t second-guess yourself. Just keep going. Promise yourself a snack when you’re done. That said, I wouldn’t try to force myself to work for too-long periods. Half-an-hour to an hour is probably best. You can probably manage to go without coffee for that long. Oh, stop whining. Of course you can! Also, if the work is going well, you can decide to keep going as long as you want. You also need to turn off your phone, the TV, and anything else that might invade your thoughts.

Music

If you really have to have music while you write, at least make sure you set up enough pieces that will keep you going during your writing session. You don’t want to have to turn the record over when you’re only half-way there. What do you mean, people don’t listen to records any more?

I recently discovered this classical music for writing on YouTube. It lasts two hours, which should be as much time as you need. You might enjoy putting together your own compilation, if your tastes run to jazz, rock, or something else. But there’s a lot to be said for silence, too.

Remind yourself that you’re working on a rough draft

One thing I find helpful when I’m working on a quickie first draft is to use a different font and colour. I like Ariel 14 in blue or purple because it is easy to read when I come to the rewrite. If you prefer to write by hand, use a different ink colour. It sends a message to your brain that this is just a first draft so you don’t need to fuss over it. It may take you a few days to get used to this being a draft, but once it sinks it, it will really loosen up those brain cells. Are loose brain cells a good thing? For the sake of argument, let’s say they are.

Eschew perfection

Don’t expect perfection or anything like it. All that matters is words on the page. Whether you organise your time by the clock or by wordcount, just keep going until you reach your goal. Don’t stop to correct mistakes, to look up a spelling, or research something. You’re only job is to put the words down. If you use a computer, disengage all the grammar- and spell-checks. They will only distract you from the task at hand.

Finally

The bad first draft is a stereotype for a good reason. Don’t even look at it again after you’ve written the whole thing. You may need to check where you left off by reviewing the paragraph before, but otherwise just keep going. Don’t worry about it being a hopeless muddle. All first drafts are, at least to some degree. Do not stop for anything. Okay, maybe if the house is on fire, but barring all genuine disasters, just keep going.

Photo by Geri

Photo by Geri