Justin Taylor's Blog, page 95

September 13, 2014

Matthew Lee Anderson: A Novel Every Christian Should Consider Reading

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

Matthew Lee Anderson is the author of The End of Our Exploring: A Book about Questioning and the Confidence of Faith and the Lead Writer at the blog Mere Orthodoxy.

He is a DPhil candidate in Christian Ethics at the University of Oxford.

There was a story, invented by himself, that The Times had once sent a representative to ask for explanations about a new play, and that Stanhope, in his efforts to explain it, had found after four hours that he had only succeeded in reading it completely through aloud: “Which,” he maintained, “was the only way of explaining it.”

There was a story, invented by himself, that The Times had once sent a representative to ask for explanations about a new play, and that Stanhope, in his efforts to explain it, had found after four hours that he had only succeeded in reading it completely through aloud: “Which,” he maintained, “was the only way of explaining it.”

Stanhope, a playwright, is one of the central characters of Charles Williams’ elusive Descent into Hell, a novel that is as terrifying as it is good. It may seem like a contradiction to describe Descent as Christianized horror novel, but I think the label fits. While other horror stories might invoke our fear of the unknown or death, Williams’ universe is even more freighted, and hence more terrifying. It is a Christian universe, after all, and for Williams the stakes between our choices are nothing less than the triumph of heaven or the solitary dissolution of hell. No book I have ever read has captured the joy and dread embedded in that line from Paul, “Awake, oh sleeper, and rise from the dead” (Eph. 5:14).

Charles Williams is not the household name that C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien were, yet as a member of the Inklings he was known by them both, and particularly admired by Lewis. Williams’ writing does not flow as easily as Dickens, nor is he as existentially tormenting as Dostoyevsky. Yet his visionary landscape in Descent is populated by phantasms and other supernatural creatures which seem to exteriorize and so heighten the interior drama of the spiritual life. Lewis articulates well why his novels are so unique here:

Descent into Hell has its darker creatures—a succubus makes an appearance, for instance—and while Williams is never grotesque or lewd, the book touches some mature themes. Which is why I can only give it a qualified commendation: I think every Christian should consider reading the book, even if they do not decide (in the last analysis) it would be good for them to do. I have read through the book with high schoolers, who have enjoyed and learned from it. But it is a book that needs a conversation (or two) after, if only to figure out what has gone on in Williams’ world. Read Descent into Hell, but maybe not alone.

The disturbing quality at the heart of Descent into Hell, though, is of the best and most memorable sorts. And while the drama of the book takes an obvious form, Williams’ awareness throughout is as subtle as the temptations we face on a regular basis. As he writes of one young woman who asks for help from Stanhope for the cast of his play, yet refuses to acknowledge her self-interest, “Nothing personal in this desire to clothe immortality with a career?” Williams subtle insight is akin to Lewis’s much more famous line about playing with mud-pies while we have been made for a holiday at the sea: yet where Lewis managed to capture the light-hearted nature of joy, Williams (in this novel) gives it a graver, much more serious hue. Descent into Hell is a reminder that joy is not necessarily akin to frivolity, that in the conflict with dark powers it comes to us as a tremendous power.

The conjunction and terror and goodness may find some readers as overwrought, and others as simply strange. In a world where we have domesticated the angels and so rendered the “Fear not” which they repeatedly announce themselves entirely unnecessary, encapsulating a “terrible goodness” requires the kind of shocking, marvelous visions that Williams provides. But for Williams, the terror and the awe is embedded within the meaning and flows from it. It is goodness, not horror, which governs his vision and which makes him worth reading. I close with his own words on the matter:

“The substantive governs the adjective; not the other way round.”

“The substantive? Pauline asked blankly.

“Good. It contains terror, not terror good.”

September 12, 2014

R. C. Sproul: A Novel Every Christian Should Consider Reading

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

R.C. Sproul (Drs, Free University of Amsterdam) is chancellor of Reformation Bible College, co-pastor of Saint Andrew’s Chapel in Sanford, Florida, founder and chairman of Ligonier Ministries, and author of numerous books, including Everyone’s a Theologian.

If your goal is to write the Great American Novel, I have bad news for you. Herman Melville accomplished that feat more than one hundred and fifty years ago when he wrote Moby Dick.

If your goal is to write the Great American Novel, I have bad news for you. Herman Melville accomplished that feat more than one hundred and fifty years ago when he wrote Moby Dick.

The greatness of Moby Dick is in its unparalleled theological symbolism that is sprinkled abundantly throughout the novel. For example, consider its use of biblical names for characters such as Ahab, Ishmael, and Elijah, and ships such as Jeroboam and Rachel.

Melville scholars disagree on the meaning of the central symbolic character of the novel—the great white whale, Moby Dick.

Many argue that he symbolizes the incarnation of evil. Ahab certainly holds this view, as he is driven by a monomaniacal hatred for this creature that took his leg and left him permanently damaged in body and soul.

Other scholars are convinced that the whale symbolizes God Himself. Thus, Ahab’s pursuit of the whale is not a righteous pursuit of God but natural man’s futile attempt in his hatred of God to destroy the omnipotent deity.

I favor this second view.

I believe that Moby Dick contains the greatest chapter ever written in the English language: “The Whiteness of the Whale.” Here we find insight into Melville’s profound symbolism as he explores how whiteness is used in history, religion, and nature. The terms he uses to describe the appearance of whiteness in these areas include elusive, ghastly, and transcendent horror, as well as sweet, honorable, and pure. Melville writes:

But not yet have we solved the incantation of this whiteness, and learned why it appeals with such power to the soul; and more strange and far more portentous—why, as we have seen, it is at once the most meaning symbol of spiritual things, nay, the very veil of the Christian’s Deity; and yet should be as it is, the intensifying agent in things the most appalling to mankind. Is it that by its indefiniteness it shadows forth the heartless voids and immensities of the universe, and thus stabs us from behind with the thought of annihilation, when beholding the white depths of the milky way? Or is it, that as in essence whiteness is not so much a colour as the visible absence of colour; and at the same time the concrete of all colours; is it for these reasons that there is such a dumb blankness, full of meaning, in a wide landscape of snows—a colourless, all-colour of atheism from which we shrink? . . . And of all these things, the albino whale was the symbol. Wonder ye then at the fiery hunt?

If the whale embodies everything symbolized by whiteness—that which is terrifying; that which is pure; that which is excellent; that which is horrible and ghastly; that which is mysterious and incomprehensible—does he not embody those traits that are found in the perfections of God Himself?

Who can survive the hostile pursuit of such a being? Only those who have experienced the sweetness of reconciling grace can look at the overwhelming power, sovereignty, and immutability of the transcendent God and find peace rather than a drive for vengeance.

Read Moby Dick—and then read it again.

September 11, 2014

Gene Fant: A Novel Every Christian Should Consider Reading

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

Gene C. Fant Jr. (PhD, University of Southern Mississippi) serves as provost and professor of English at Palm Beach Atlantic University in West Palm Beach, Florida.

He is the author of The Liberal Arts: A Student’s Guide and God as Author: A Biblical Approach to Narrative.

Occasionally American literature students are assigned William Faulkner’s 1930 novel As I Lay Dying. The choice is somewhat pragmatic, as Faulkner is one of the 20th Century’s great fiction writers but his masterwork, The Sound and the Fury, is incredibly difficult to read. As I Lay Dying is brief and the plot is intriguing (a backwoods family’s preparations for the matriarch’s burial, stymied by a difficult journey to the family plot). One chapter is composed entirely of one sentence (“My mother is a fish”), which has led to many a perplexed and exasperated student. At least there is now a film adaptation directed by uber-cool James Franco.

For Christians, As I Lay Dying offers a bonanza of theological discovery, not in terms of devotional affirmation of orthodoxy but in terms of its sober reminders of the necessity of faith. Faulkner adored the Old Testament but was less enamored of the New, believing that the stories of the Hebrew Scriptures were more compelling. My sense is that he was a crypto-Calvinist who believed the atonement to be so limited (and God to be either so holy or so cruel) that no one is elect. God is a just Judge who rightly sentences everyone to death. Each of us, then, lives on a constant trajectory toward death; vultures circle each of our corpses, at least metaphorically.

I have heard it said that Western culture, American culture in particular, is enamored with the Gospel’s fruit even as it dismisses its roots in Christ’s sacrificial, grace-filled ministry that calls us to humble repentance. As I Lay Dying depicts a dreadful world that has neither the Gospel’s root nor its fruit.

The novel ponders the nature of manhood and femininity.

It confronts us with the desperation that accompanies abortion.

It provides us with an fictive incarnation of the Darwin Awards‘ most thick-skulled stupidity.

For those of us who become Christ-followers at a young age, there is a constant risk of forgetfulness about what life is like without the hope of the Gospel. We simply cannot remember what it feels like to live without hope, which is the state of our friends and neighbors apart from Christ. As I Lay Dying is a way to empathize afresh with this hopelessness. When we get to the closing pages, we are overcome: Oh! Would that the world did not have to be like this! Would that we were more than dying animals trapped in a dying world! Would that there were a Savior who could rescue us from our stupidity and mortality!

Ah, there is the lesson. Salvation comes from outside of this sphere. Until we humble our hearts and lift up our eyes, we cannot see what is transcendently present: Christ’s offer of grace.

September 10, 2014

John Mark Reynolds: A Novel Every Christian Should Consider Reading

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

John Mark Reynolds (PhD, University of Rochester) is the provost of Houston Baptist University.

Prior to joining Houston Baptist, he was the founder and director of the Torrey Honors Institute (a great books program) and associate professor of philosophy at Biola University.

His books include When Athens Met Jerusalem: An Introduction to Classical and Christian Thought: Excerpts and Essays on the Most Influential Books in Western Civilization, and he was the editor of The Great Books Reader. His latest book is a fantasy novel, Choosing Shadows.

You can follow him on Twitter at @JMNR.

Langston Hughes (1902-1967) is the greatest American literary talent: poet, essayist, short-story author, and novelist. Joseph Smith sells more books, but lacks his artistry. Mark Twain is more frequently read, but he was no poet. James Fennimore Cooper is one long series of adjectives. Moby Dick is a great book, but Melville is not as consistently readable as Hughes.

Langston Hughes (1902-1967) is the greatest American literary talent: poet, essayist, short-story author, and novelist. Joseph Smith sells more books, but lacks his artistry. Mark Twain is more frequently read, but he was no poet. James Fennimore Cooper is one long series of adjectives. Moby Dick is a great book, but Melville is not as consistently readable as Hughes.

A collection of short stories, The Ways of White Folks is an excellent introduction to his work. Hughes writes of how some white folks deal with the humanity of black people in their midst. Attitudes range from the Carraways, “benevolent” racists who are into the ways of black folks, to the story of plantation owner Colonel Thomas Norwood who cannot acknowledge his love for his black common-law wife or their children. The end of that story is one of the most heartbreaking an American can read.

If racism and race-based slavery was America’s original sin, Hughes demonstrates that racism and the legacy of slavery were alive and killing us in the middle of the last century. Conservative Christians know that history matters, ideas have consequences, and the wages of continued sin keep being death.

And while Hughes’s African-American characters may be harmed by the ways of (some) white folk, white folk do not govern the real lives of black folk. Mrs. Ellsworth may patronize her protégé Oceola, but Oceola lives her own life and creates her own art.

Hughes’s black folks are forced to deal with the white majority, and there is no easy triumph or “lessons” learned. Hughes presents characters that are human: white folk and black folk. All humans inherit bad and good ideas and all humans have the capacity to create, but no human can ever simply be an object of hate or even of pity. The young Arnie will not remain a “poor little black fellow,” but grows up to become a man.

The short stories are not hopeful in themselves, mostly ending bleakly, but there is hope in characters themselves. The racist is a man when he is a racist: a bad man. The African-American is no less a man when he succumbs to racial stereotypes, as some of Hughes’s characters do to survive, but he is an oppressed man. For Hughes, humanity—sheer cussed humanness—is always breaking out and defying the lies of the racialist.

Langston Hughes promotes the existence, not just the possibility, of African-American culture for itself. In his stories, the jazz and the renaissance of art in the big cities is not something for white folk to consume, but the creation of a people group, because they are a people group.

Black folk exist for black folk.

Hughes’s poetry, and his short stories, are full of allusions to Christianity. In his own life, Langston Hughes rejected Christianity and considered secular solutions—a few (like the Soviet Union) monstrously evil. Hughes’s imagination, however, remained haunted by Christian images and ideas. If he died without Jesus—and who can be sure of such things?—Hughes always had the story of Jesus in his mind and heart.

Christians failed Langston Hughes, even if Christ did not, but Hughes never lost faith in people, especially his people. I think, perhaps, he saw the image of God so plainly there that even his non-theism ended up God-haunted.

Perhaps.

Hughes is, however, great enough that he cannot be pigeonholed or dismissed by such as I am. Hughes must be read, considered, and allowed to stand as a great author always to be considered and as a man who has a great deal to teach us.

September 9, 2014

Gene Veith: A Novel Every Christian Should Consider Reading

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

Gene Edward Veith Jr. (PhD, University of Kansas) is the provost and professor of Literature at Patrick Henry College, the Director of the Cranach Institute at Concordia Theological Seminary, a columnist for World Magazine and , he satirizes the conflict between what Christianity teaches and the cultural Christianity of the time. Thus, the Grangerford family is warm and kind, full of sincere Christian piety and good works—except that they are engaged in a blood feud with the equally devout Shepherdsons, and they have been killing each other’s children for generations, even though no one can remember how it all started or why they hate each other so much.

The turning point of the novel is when Huck decides to violate his conscience and everything he had been taught in Sunday School by helping Jim attain his freedom. Huck describes how he decided to turn his life around and follow the path of righteousness by turning in Jim to his rightful owners. But then, getting a glimpse of Jim’s humanity, Huck decides to help Jim escape, even though this would be stealing, and even though this crime would surely condemn him eternally. “All right, then,” Huck decides. “I’ll go to Hell.” That line has to make any Christian cringe. But one reason why we cannot be saved by our good works is that when we do them thinking that they will cause us to merit Heaven, that takes away their moral significance. Our sinful nature is such that we can even do good works for a selfish motive. With Huck, the moral universe is so topsy-turvy that a bad work (betraying a friend) is thought to be a good work, and a good work (helping a friend) is construed as a bad work. Instead of doing what is right in return for an eternal reward, Huck does what is right—loving and serving his neighbor—even though he expects it will earn him an eternal punishment. Again, more irony that can put many readers off. But in general, it is good for Christians to endure satires against hypocrisy and their own un-Christian attitudes and behavior. They help keep us in a state of repentance. In the last section of the novel, the poor but virtuous and realistic Huck meets up again with his friend Tom Sawyer with his middle-class status and wildly romantic ideals. Hemingway says that we should skip this last part, which just gets silly and turns the noble Jim into more of a clown. At the very end, Huck decides to do what Americans always used to do (when they could) after running into intractable problems: “light out for the Territory.” Go West, head for the frontier, start a new life. That’s basically what Mark Twain did in leaving the war-torn South for the silver mines of Nevada. The novel reminds the Christian reader that sin goes deep into the human heart and into human society and that it makes us all slaves; and it awakens a desire for freedom that can only come from Christ, who died to set us free. Others may not get that from the story. But Christians will.

September 8, 2014

Bonhoeffer on What a Christian Under the Cross Can Offer that a Secular Therapist Cannot

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Life Together:

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Life Together:

Whoever lives beneath the cross of Jesus, and has discerned in the cross of Jesus the utter ungodliness of all people and of their own hearts, will find there is no sin that can ever be unfamiliar.

Whoever has once been appalled by the horror of their own sin, which nailed Jesus to the cross, will no longer be appalled by even the most serious sin of another Christian; rather they know the human heart from the cross of Jesus.

Such persons know how totally lost is the human heart in sin and weakness, how it goes astray in the ways of sin—and know too that this same heart is accepted in grace and mercy.

Only another Christian who is under the cross can hear my confession. It is not experience with life but experience of the cross that makes one suited to hear confession. The most experienced judge of character knows infinitely less of the human heart than the simplest Christian who lives beneath the cross of Jesus.

The greatest psychological insight, ability, and experience cannot comprehend this one thing: what sin is. Psychological wisdom knows what need and weakness and failure are, but it does not know the ugliness of the human being. And so it also does not know that human beings are ruined only by their sin and are healed only by forgiveness. The Christian alone knows this. In the presence of a psychologist I can only be sick; in the presence of another Christian I can be a sinner.

The psychologist must first search my heart, and yet can never probe its innermost recesses. Another Christian recognizes just this: here comes a sinner like myself, a godless person who wants to confess and longs for God’s forgiveness.

The psychologist views me as if there were no God. Another believer views me as I am before the judging and merciful God in the cross of Jesus Christ.

When we are so pitiful and incapable of hearing the confession of one another, it is not due to a lack of psychological knowledge, but a lack of love for the crucified Jesus Christ.

—Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Life Together and Prayerbook of the Bible, Dietrich Bonhoeffer Works, vol. 5 (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1996), 114-16.

Karen Swallow Prior: A Novel Every Christian Should Consider Reading

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

Karen Swallow Prior (PhD, State University of New York at Buffalo) is Professor of English at Liberty University.

Dr. Prior is the author of Booked: Literature in the Soul of Me and the forthcoming Fierce Convictions: The Extraordinary Life of Hannah More—Poet, Reformer, Abolitionist (releasing in November).

She is a Research Fellow with the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission and a member of the Faith Advisory Council of the Humane Society of the United States.

Most of us who read novels today can’t imagine a world without novels and may not realize that the novel is a relatively recent literary invention, a product, in fact, of modernity. While its history is long and complicated, literary critics usually point to two particular works that gave rise to the novel. Samuel Richardson, the author credited as the “father of the novel,” published a series of letters purportedly written by a young servant girl named Pamela (the title of the work) whose virtue overcomes the unscrupulous pursuits of her rich master. Pamela, published in 1740, took the British nation by storm and was so popular that it was the first novel to be published across the pond here in America.

Most of us who read novels today can’t imagine a world without novels and may not realize that the novel is a relatively recent literary invention, a product, in fact, of modernity. While its history is long and complicated, literary critics usually point to two particular works that gave rise to the novel. Samuel Richardson, the author credited as the “father of the novel,” published a series of letters purportedly written by a young servant girl named Pamela (the title of the work) whose virtue overcomes the unscrupulous pursuits of her rich master. Pamela, published in 1740, took the British nation by storm and was so popular that it was the first novel to be published across the pond here in America.

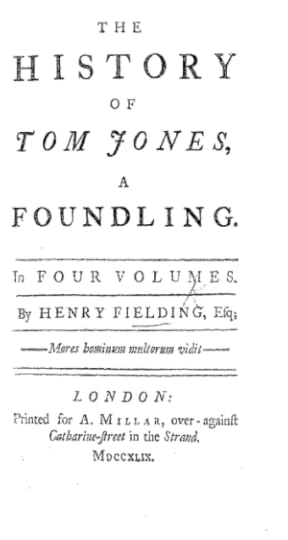

Enter Henry Fielding, a classically-schooled playwright and aristocrat who was scandalized that an upstart middle-class printer took center stage in the world of letters with such a low work. The History of Tom Jones, A Foundling is Fielding’s literary rebuttal to Pamela.

Tom Jones is a masterpiece. Like Richardson, Fielding did not use the term “novel.” The sorts of works called “novels” at this time were disreputable tales of illicit love and adventure; no serious author would seek to adopt the label until the nineteenth century. Instead, Fielding modeled Tom Jones after the classical epic: the book is epic in length and structured into volumes, books, and chapters. It tells an expansive tale of a foundling boy who traverses from the English countryside to London and back again in search of his rightful identity and home—and, of course, love, for it’s a comic as well as an epic story.

Tom Jones is also influenced by the allegory of John Bunyan. Tom’s journey is an allegorical one, although not nearly as obviously so as in Pilgrim’s Progress. His adoptive father, Squire Allworthy, for example, is a very worthy man, and serves as a benevolent deity over his estate, named Paradise Hall (from which Tom is expelled for a time). Tom’s main love interest (there are many—this novel is not for the prudish reader!) is named Sophia. As Tom pursues her, he is also pursuing wisdom (the meaning of the Greek word sophia).

In addition to the grandness of the story and the richness of its layers of meaning, Tom Jones offers a veritable crash course in this period of church history. In his latitudinarian Anglicanism, Fielding takes on the rising Methodism (which would birth evangelicalism) of the day (particularly manifested in the pietistic Pamela). In Tom Jones can be seen the seeds of theological liberalism, yet at the same time, the correction it offers to extreme pietism—as well as other extremes such as deism and asceticism—instructs by delighting: Tom is a good-hearted rogue who errs and learns as he encounters countless scoundrels, ladies, less-than-ladies, and lessons on his way.

And this is the most important point: Tom Jones is a fun novel. The reader has to work a little (actually, a lot) to gain the novel’s rich rewards—the novel is long, erudite, meandering, and of a very different age—but the investment is well worth the effort. I highly recommend the Wesleyan edition for its copious footnotes which will not only assist in the reading but increase understanding so as to produce even more laughter. After you’ve read the novel, treat yourself to the 1963 Oscar-winning film adaptation (which, while very good, does not come close to conveying all that the novel holds).

The History of Tom Jones is the best kind of novel: one that provokes both wisdom and laughter and invites many re-readings.

September 6, 2014

Philip Ryken: A Novel Every Christian Should Consider Reading

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

Philip Graham Ryken (DPhil, University of Oxford) is the eighth president of Wheaton College and has served in that capacity since 2010. Prior to his appointment at Wheaton, he served as senior minister at historic Tenth Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia.

His newest book is Loving Jesus More (which releases on Monday), and he is the co-author (with Leland Ryken and Todd Wilson) of Pastors in the Classics: Timeless Lessons on Life and Ministry from World Literature.

Cry, the Beloved Country is widely regarded as the definitive novel of the South African experience. Although the book was written more than half a century ago and published before apartheid was established as a system of racial segregation, its hopeful yet honest treatment of social issues has ongoing relevance for South Africa and the world. Alan Paton invited his readers to embrace this global perspective when he described his novel as “a song of love for one’s far distant country . . . the land where you were born.”

Cry, the Beloved Country is widely regarded as the definitive novel of the South African experience. Although the book was written more than half a century ago and published before apartheid was established as a system of racial segregation, its hopeful yet honest treatment of social issues has ongoing relevance for South Africa and the world. Alan Paton invited his readers to embrace this global perspective when he described his novel as “a song of love for one’s far distant country . . . the land where you were born.”

To read Cry, the Beloved Country is to become immersed in the tragic complexities of racial conflict that gripped South Africa in the 1940’s and afterwards. Paton vividly evokes the events of that time and place: the political speeches, the rise of the black shanty towns, the mining and transportation strikes, the personal sacrifices that blacks and whites both made in order to serve one another across racial lines.

He also addresses some of the hardest challenges that remain for South Africa, such as the corruption of power, the ever-present danger of criminal violence, and the need for new social structures to rebuild broken families in divided communities.

All of this forms the setting for the dramatic story of loss and forgiveness that Paton tells about one man—a priest named Kumalo—who endures painful suffering in a fallen world and struggles to understand the purposes of God for his life, his family, his church, and his community.

I read Cry, the Beloved Country to renew my hope in what one person can do in response to the world’s heartbreaking need for justice and mercy. Kumalo knows what he is up against: “the house that is broken, and the man that falls apart when the house is broken, these are the tragic things. That is why children break the law, and old white people are robbed and beaten.” At the same time, Kumalo knows that God has called him to bind the wounds of the broken with truth and mercy.

I also read Paton’s novel to renew my sense of calling as a minister of the gospel. Despite his own weakness and sin—including his failings as the father of a prodigal son—Kumalo perseveres in his God-given ministry. In one of the novel’s transformative scenes, the priest goes up the mountain above his village to remember his sins “as well as he could” and to repent of them “as fully as he could,” praying for God’s forgiveness.

His soul renewed by repentance, Kumalo returns to face the challenges of serving his humble, beautiful congregation. Even when he is tempted to believe that there is “nothing in the world but fear and pain,” Kumalo continues to pray, to preach, and to serve his community with the love of Jesus.

Cry, the Beloved Country has similar effects on my own ministry. Paton’s novel captures the tragic beauty of human brokenness in ways that inspire humble repentance, genuine faith, and faithful ministry.

September 5, 2014

Wesley Hill: A Novel Every Christian Should Consider Reading

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

Welsey Hill (PhD, University of Durham) is assistant professor of New Testament at Trinity School for Ministry (Ambridge, PA).

He is the author of Washed and Waiting and the forthcoming revision of his dissertation, Paul and the Trinity: Persons, Relations, and the Pauline Letters (you can read an interview about the book here.)

He blogs at Spiritual Friendship, has a commonplace book, and can be followed on Twitter at @wesleyhill.

A few months ago I was sitting in a circle of evangelical Christian academics, all of whom teach at a Christian college. The conversation steered its way through various currents and eddies, disagreements emerging here and there like choppy waters—until we came to the topic of Chaim Potok’s novels. About those we had no disagreement at all, nor even much variation in our reading experiences: We all, at some point in our intellectual pilgrimages, had had strikingly similar encounters with Potok’s work.

From his context in Orthodox Judaism, Potok named something common to us evangelicals who had found ourselves, at first, reading widely, then entering university and graduate school, and then, ultimately, accepting teaching posts at universities or graduate schools ourselves. Potok helped us see and understand our shared situation, our (at times fraught, at times joyful) struggle to maintain allegiance to the faith we were raised in while exploring competing ideas and ways of life in the wider world.

Chaim Potok is best known as a novelist and a rabbi. Born in 1929, he published a litany of books that each, in its own way, delves into the same complex thicket of conflicts. Many of his characters, not least the protagonists of his most acclaimed work The Chosen, are Hasidic Jews who are somehow confronted with the fact that the worlds they are drawn to—the worlds of art, biblical criticism (in The Promise and In the Beginning), and the secular academy, for instance—pose searching challenges to their pre-existing beliefs and patterns of life.

The first Potok novel I read remains my favorite: . Its plot is elegantly simple, and it builds to a quietly devastating conclusion. We meet Asher Lev in the book’s opening pages as an adult who is known for painting the Brooklyn Crucifixion. As subsequent chapters unfold, we see how he became that artist—and at what cost.

Raised in a strictly observant home in post-war New York, Asher finds that he has a gift for painting. At first he doesn’t recognize it as such, but his parents, friends, and teachers help him take appropriate pride in his eye for beauty and his skill in portraying it.

As he cultivates this gift, Asher enters more and more deeply into the world of the goyim, the world outside synagogue and yeshiva, and finds himself inexorably pulled toward depicting Jesus’ crucifixion. This isn’t, for Asher, about conversion to Christianity; it’s rather about taking the supreme moment of redemptive human suffering and employing it to speak to his people’s own contemporary suffering and beyond. But how can this be, Asher’s family wonder, when the Holocaust is such a recent chapter in the Jewish people’s story? How can Asher take up the religious symbol of the Jewish people’s persecutors? Such an act can only be a betrayal of his Judaism—or might there be some new way of being Jewish that he hasn’t yet fathomed?

isn’t a heavy-handed apologetic for a more liberal, tolerant form of faith. Nor is it ultimately a confirmation that more conservative forms need no maturation. What Potok offers instead is a lovingly drawn portrait of a modern believer, one who learns the difference between “believing still” and what W. H. Auden has called “believing again.” In addition to all the delights of great literature, there are lessons here for us evangelicals. We too, after all, are a chosen race and faithful exiles in a foreign land (1 Peter 1:2; 2:9).

September 4, 2014

How a Christian Is Like a Little Child

Jonathan Edwards:

The tenderness of the heart of a true Christian, is elegantly signified by our Savior, in his comparing such a one to a little child. . . .

A little child has his heart easily moved, wrought upon and bowed: so is a Christian in spiritual things.

A little child is apt to be affected with sympathy, to weep with them that weep, and can’t well bear to see others in distress: so it is with a Christian (John 11:35, Romans 12:15, I Corinthians 12:26).

A little child is easily won by kindness: so is a Christian.

A little child is easily affected with grief at temporal evils, and has his heart melted, and falls a weeping: thus tender is the heart of a Christian, with regard to the evil of sin.

A little child is easily affrighted at the appearance of outward evils, or anything that threatens its hurt: so is a Christian apt to be alarmed at the appearance of moral evil, and anything that threatens the hurt of the soul.

A little child, when it meets enemies, or fierce beasts, is not apt to trust its own strength, but flies to its parents for refuge: so a saint is not self-confident in engaging spiritual enemies, but flies to Christ.

A little child is apt to be suspicious of evil in places of danger, afraid in the dark, afraid when left alone, or far from home: so is a saint apt to be sensible of his spiritual dangers, jealous of himself, full of fear when he can’t see his way plain before him, afraid to be left alone, and to be at a distance from God; Proverbs 28:14, “Happy is the man that feareth alway; but he that hardeneth his heart shall fall into mischief.”

A little child is apt to be afraid of superiors, and to dread their anger, and tremble at their frowns and threatenings: so is a true saint with respect to God; Psalms 119:120, “My flesh trembleth for fear of thee, and I am afraid of thy judgments.” Isaiah 66:2, “To this man will I look, even to him that is poor, and trembleth at my word.” V. 5, “Hear ye the Word of the Lord, ye that tremble at his word.” Ezra 9:4, “Then were assembled unto me, everyone that trembled at the works of the God of Israel.” Ch. 10:3, “According to the counsel of my Lord, and of those that tremble at the commandment of our God.” A little child approaches superiors with awe: so do the saints approach God with holy awe and reverence. Job 13:11, “Shall not his excellency make you afraid, and his dread fall upon you.” Holy fear is so much the nature of true godliness, that it is called in Scripture by no other name more frequently, than the fear of God.

Religious Affections, WJE, pp. 360-61.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers