Justin Taylor's Blog, page 94

September 25, 2014

Dane Ortlund: Edwards on the Christian Life

I am so thankful for Dane Ortlund’s new book, Edwards on the Christian Life: Alive to the Beauty of God. As George Marsden notes in his foreword, “Books such as Edwards on the Christian Life are especially welcome as part of the current Edwards revival precisely because Edwards is so many-sided and complex. The essence of his theology needs to be distilled from his many writings and to be presented in practical terms for Christians today. Dane Ortlund does just that. Reading Edwards’s own works can inspire Christians today, but often it is best to start with a more accessible introduction, such as the present one.”

I am so thankful for Dane Ortlund’s new book, Edwards on the Christian Life: Alive to the Beauty of God. As George Marsden notes in his foreword, “Books such as Edwards on the Christian Life are especially welcome as part of the current Edwards revival precisely because Edwards is so many-sided and complex. The essence of his theology needs to be distilled from his many writings and to be presented in practical terms for Christians today. Dane Ortlund does just that. Reading Edwards’s own works can inspire Christians today, but often it is best to start with a more accessible introduction, such as the present one.”

In Ortlund’s introduction he provides an outstanding overview of where he is going:

Our strategy will be to ask twelve questions about the Christian life and provide, from Edwards, corresponding answers. These will form the chapters of this book, with a final thirteenth chapter diagnosing four weaknesses in Edwards’s view of the Christian life. Twelve chapters identify what we can learn from Edwards; one chapter identifies what he could learn from us. In brief the twelve questions and answers are:

1. What is the overarching, integrating theme to Edwards’s theology of the Christian life?

Answer: Beauty.

2. How is this heart-sense of beauty ignited? How does it all get started? What must happen for anyone to first glimpse the beauty of God?

New birth.

3. Having begun, what then is the essence of the Christian life? What does seeing God’s beauty create in us? What’s the heart and soul of Christian living?

Love.

4. How does love fuel the Christian life? What’s the non-negotiable of all non-negotiable that will keep us loving? What does divine beauty give to us?

Joy.

5. And what uniquely marks such love and joy? What is the aroma of the Christian life? What does Edwards diagnose about the Christian life that is most important for recovery today?

Gentleness.

6. Where do I go to get this love, joy, and gentleness? How can I find it? What,

concretely, sustains this kind of life, through all our ups and downs?

The Bible.

7. But as I go to the Bible, what do I do with it as I read? How do I own it, make it mine,

turn it into this joy-fueled love?

Prayer.

8. What then is the overall flavor of the Christian life? What is the aura, the feel, of following Christ in a world of moral chaos and pain?

Pilgrimage.

9. As new birth, Bible, prayer, and all the rest go in, what comes out? What is the fruit of the Christian life?

Obedience.

10. Who is the great enemy of Christian living? Who wishes above all to prevent loving, joyful, gentle lives?

Satan.

11. What is the great concern of the Christian life? Toward what, supremely, should our

efforts be directed as we walk with God?

The soul.

12. Finally, what does all this funnel into? When will we be permanently and fully and unfailingly alive to beauty? What, above all else, is the great hope of the Christian life?

Heaven.

He closes with four criticisms—which alone (in my opinion) is worth the price of the book.

You can watch a video interview with Ortlund above, and/or listen to this podcast conversation he had with Tony Reinke.

Here are some commendations:

“In his theological concern for the beautiful and the beauty of God, Jonathan Edwards stands at the end of a long theological tradition that reaches back to Augustine and beyond, even to the Scriptures themselves. In the last two centuries, however, this area of theological inquiry seems to have dropped off the radar for Christian theologians and practitioners, which may explain why students of Edwards’s corpus of writings have not tackled the subject. Ortlund’s study nicely fills this lacuna, for he rightly shows, from a multitude of angles, that beauty is the fulcrum of Edwards’s thinking. A joy to read and to ponder!”

—Michael A. G. Haykin, Professor of Church History and Biblical Spirituality, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary

“Jonathan Edwards is widely known as a hellfire-and-brimstone preacher. Serious students, like Dane Ortlund, have long known he was much more. In this book Ortlund puts his careful research to good purpose as he demonstrates convincingly that the center of Edwards’s concern was always and supremely beauty—in God, from God, and for God. Grateful readers will find this book highly informative on Edwards and deeply encouraging for the Christian life today.”

—Mark A. Noll, Francis A. McAnaney Professor of History, University of Notre Dame

“No one has taught me more about the dynamics of Christian living than has Jonathan Edwards. And no one has more clearly articulated the role of beauty in Edwards’s understanding of the Christian life than has Dane Ortlund. If you’re unfamiliar with Edwards, or if you wonder how beauty could possibly have any lasting effect in your growth as a Christian, this book is for you.”

—Sam Storms, Lead Pastor for Preaching and Vision, Bridgeway Church, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

“What a delight to see a book on Edwards’s conception of the Christian life. And how beautiful it is that it depicts the Christian life as ordered by and to the beauty of God. This book will help strengthen the fertilization of today’s churches by Edwards’s vision of God’s triune beauty.”

—Gerald R. McDermott, Jordan-Trexler Professor of Religion, Roanoke College; co-author, The Theology of Jonathan Edwards

“‘The supreme value of reading Edwards is that we are ushered into a universe brimming with beauty,’ writes Ortlund. I couldn’t agree more. And one would be hard-pressed to find a more engaging introduction to this universe for the church. Even the final chapter, on ways in which we should not follow Edwards, offers crucial Christian wisdom. Ortlund’s criticisms of Edwards hit the mark—and deserve consideration by Edwards’s growing number of fans. I plan to use them with my seminary students in years to come. Please peruse this beautiful book. It’s good for the soul.”

—Douglas A. Sweeney, Professor of Church History, Director of the Jonathan Edwards Center, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School

“Edwards is profound, and this book breaks down the complexity into manageable portions around the theme of beauty, thus engaging readers in a fresh vision of the importance of Edwards’s theology to contemporary living.”

—Josh Moody, Senior Pastor, College Church, Wheaton, Illinois; author, Journey to Joy: The Psalms of Ascent

This book is the latest entry in Crossway’s Theologians on the Christian Life series, which I edit with Stephen Nichols.

Here are the other books published in the series so far:

2012

Fred Zaspel, Warfield on the Christian Life: Living in Light of the Gospel

2013

William Edgar, Schaeffer on the Christian Life: Countercultural Spirituality

Stephen J. Nichols, Bonhoeffer on the Christian Life: From the Cross, for the World

Fred Sanders, Wesley on the Christian Life: The Heart Renewed in Love

2014

Michael Horton, Calvin on the Christian Life: Glorifying and Enjoying God Forever

And here are the volumes forthcoming:

2015

Carl Trueman, Luther on the Christian Life: Cross and Freedom (February)

Tony Reinke, Newton on the Christian Life: To Live Is Christ (May)

Sam Storms, Packer on the Christian Life: Knowing God in Christ, Walking by the Spirit (June)

John Bolt, Bavinck on the Christian Life (August)

Michael A.G. Haykin and Matthew Barrett, Owen on the Christian Life (September)

Gerald Bray, Augustine on the Christian Life (October)

2016

Jason Meyer, Lloyd-Jones on the Christian Life

2017

Michael Reeves, Spurgeon on the Christian Life

Derek Thomas, Bunyan on the Christian Life

September 24, 2014

Jared Wilson: A Novel Every Christian Should Consider Reading

This is the final entry in a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

This is the final entry in a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

Jared Wilson is the pastor of Middletown Springs Community Church in Middletown Springs, Vermont.

He is the author of several books, the latest two of which are The Storytelling God: Seeing the Glory of Jesus in His Parables and The Wonder-Working God: Seeing the Glory of Jesus in His Miracles.

He blogs at Gospel-Driven Church and you can follow him on Twitter, @JaredCWilson.

My first encounter with Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair was in reviewing the Neil Jordan film adaptation with Ralph Fiennes and Julianne Moore for my college newspaper. I hated it. There was a spirit of something intriguing there about faith and disbelief, but the whole thing seemed muted, hazy, smeared over with the maudlin romanticism so common in Hollywood period pieces. Someone later convinced me to pick up the source material, however, and I discovered in Greene’s work, the fourth of his more explicitly Christian novels, what could not be captured on screen—the often maddening complexities of belief and disbelief, and the thin line between raging against God and fearing him.

My first encounter with Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair was in reviewing the Neil Jordan film adaptation with Ralph Fiennes and Julianne Moore for my college newspaper. I hated it. There was a spirit of something intriguing there about faith and disbelief, but the whole thing seemed muted, hazy, smeared over with the maudlin romanticism so common in Hollywood period pieces. Someone later convinced me to pick up the source material, however, and I discovered in Greene’s work, the fourth of his more explicitly Christian novels, what could not be captured on screen—the often maddening complexities of belief and disbelief, and the thin line between raging against God and fearing him.

“A story has no beginning or end,” Greene’s story begins. There is something else that has no beginning or end—or Someone else, rather, and his shadow looms large over each page of the novel, which chronicles the adulterous affair between writer Maurice Bendrix and Sarah Miles, the wife of a British officer.

The illicit romance seems routine enough: passionate artist type woos the bored wife of a boring man. But during one of their encounters a bomb blast during the German blitzkrieg of London destroys their room, nearly killing Bendrix. After this traumatic event, the romance mysteriously sours, and Bendrix is sent into a tailspin of jealousy and lust.

He believes he’s been traded in for a new lover, so he hires a private investigator who discovers that indeed Bendrix has been. But Sarah’s new lover turns out to be the source of all love himself. When Bendrix nearly died, she prayed for his safety and made a commitment to God that if his life was spared, she would not see him any longer. As painful as it was to give up her illicit dalliance, the alternative was more painful. She feared not for body first, but for soul. And here we find something rather strange and rather unique in the great midst of literary exploration of sexual sin. Where so many romantic works treat adultery as “natural,” totally legitimized by Romance, the great theoretical justifier of all things, here is a little book where the woman loves her lover by not “loving” him.

This of course infuriates the worldly Bendrix, who comes to see religion as another boring husband dampening all his romantic fury, frustrating the artistic expression of his very appetites. And when Sarah later catches tuberculosis and dies, he sees her God not just as an interloper, but a villain.

And there is where the tale deepens. In her withholding, in her painful disengagement, and now in her cruel death, Sarah has taught Bendrix more about love than she ever could have in the immoral passion of their previous life together. And Bendrix is now forced for the first time to reckon with the great Enemy of his fleshly appetites, the great unbounded Author who had so unfairly deleted his story.

I am reminded of C. S. Lewis’s line about his youthful atheism: “I did not believe that God existed,” he said, “and I was very angry with him for not existing.” Indeed, in the end, as Bendrix shakes his fist at Sarah’s God, rejecting the object of her prayers on his behalf, proclaiming defiantly even his hatred for God—“I wanted Sarah for a lifetime and You took her away. With Your great schemes You ruin our happiness like a harvester ruins a mouse’s nest: I hate You, God, I hate You as though You existed”—we think he doth protest too much. He doesn’t even seem to realize he’s praying.

No, being angry with God is not right or just. But it’s a start. When The End of the Affair‘s story ends, Bendrix’s Jacobean wrestling is just beginning. We are sure, by the last lines, gleaming with a sliver of hope, like a light through a cracked door—“I said to Sarah, all right, have it your way. I believe you live and that He exists”—that Bendrix will not walk away from his wrestling unchanged. The reader walks away, in fact, with the great hope that hatred may have a peculiar advantage over ambivalence in that it is at least a kind of caring, a passion that is simply waiting for the redirection of the transforming gospel.

September 23, 2014

Rick Segal: A Novel Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

Rick Segal is Vice President of Advancement and Distinguished Lecturer of Commerce and Vocation at Bethlehem College & Seminary, following a 30-year career as entrepreneur and global advertising executive. He is responsible for donor relations and institutional communications, as well as teaching and writing related to his role as Lecturer.

He and his wife Adrien have four grown sons.

A promotional slug on the cover of my 1993 edition of Quo Vadis by Henryk Sienkiewicz declares the book to be, “Worldwide #1 Bestselling Novel of All Time.”

A promotional slug on the cover of my 1993 edition of Quo Vadis by Henryk Sienkiewicz declares the book to be, “Worldwide #1 Bestselling Novel of All Time.”

The claim is unattributed, and a online search 21 years later suggests it may be dubious.

What is objective is that this historical novel of Rome in Christianity’s first century, indeed its first decades, has been in continuous publication since 1895, translated into more than 50 languages, the inspiration of four American and three European film versions, and partially responsible for earning its author the Nobel Prize for literature.

Quo Vadis derives its name from the Latin, “Quo vadis Domine,” “Where are you going, Lord?”, an allusion to an event described in the apocryphal Acts of Peter in which the saint while fleeing Rome encounters Christ heading toward the city.

“Where are you going, Lord?,” Peter asks.

“I am going back to be crucified, again.”

Peter takes this as his cue to turn back and accept martyrdom.

This is Rome in the last earthly days of both Peter and Paul. The Gospel has found a home in the hearts of a small community of believers living in the shadows of Nero’s temples and obelisks. It is a human-scale story of a cataclysmic culture clash, played out in the broad strokes of historical events, and in a love story about a young Christian woman, Ligia, and a Roman patrician, Vinicius.

The clash is exposed in exchanges like this excerpt from letter sent by the fictional Vinicius to the real-life Petonius, Nero’s Arbiter of Excellence:

O Petronius, you do not realize what a comfort and consolation our religion can be in misfortune, how much patience and courage it inspires before death. So come and see for yourself how much happiness it can give in ordinary day-to-day living. People up to now did not know a God Whom they could love hence they did not love one another. From this came misfortune because as the light comes from the sun so too happiness comes from love. Languages, philosophies did not teach this truth and it did not exist in Greece nor in Rome; and when I say Rome, I mean the whole world.

The book’s graphic descriptions of the persecution of Christians were undoubtedly informed by Foxe. This is why some current reader reviews online regard the book as too disturbing to complete. It is, however, the essential argument for reading Quo Vadis. Vats have gathered the blood of martyrs all along the way to the present. Persecution of believers is yet promised. Quo Vadis tells the story of those found first-faithful in persecution’s face.

I am no spoiler to share:

The road to the execution place was long. . . . Paul felt this peace in his heart and he thought with gladness that by his life he has added notes of harmony without which the whole earth was sounding brass or tinkling cymbals. . . . Inwardly, he repeated the words of one of his epistles: “I have fought the good fight. I have finished my course. I have kept the faith. Henceforth, there is waiting for me a crown of glory.”

September 22, 2014

Mike Cosper: A Novel Every Christian Should Consider Reading

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

Mike Cosper is one of the founding pastors of Sojourn Community Church in Louisville, Kentucky, where he serves as the pastor of worship and arts.

He is the founder of Sojourn Music and contributes regularly to the Gospel Coalition blog, where he writes about worship and culture.

He is the co-author of Faithmapping and the author of Rhythms of Grace: How the Church’s Worship Tells the Story of the Gospel. His latest book is The Stories We Tell: How TV and Movies Long for and Echo the Truth (foreword by Tim Keller).

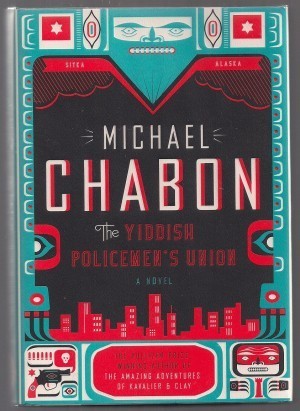

“My homeland is my hat.”—Meyer Landsman, The Yiddish Policeman’s Union

“My homeland is my hat.”—Meyer Landsman, The Yiddish Policeman’s Union

Author Michael Chabon was wandering a bookstore when he came across a book called Say It in Yiddish. It was a phrase book for travelers who might find themselves needing directions, a meal, or (the book seriously provides this) a tourniquet. It struck Chabon as deeply nostalgic and tragic. “Where,” Chabon wondered, “would be the most fabulous kingdom you could have taken this phrase book to, if the Holocaust hadn’t happened?” In a post-WW2 world, the idea of a Yiddish-speaking community seemed both sad and magical.

What emerged from this question was The Yiddish Policeman’s Union, a Hugo-Award winning novel that weaves together a Noir-style detective story, a wholesale reimagination of 20th-century global politics, and Chabon’s own voice, which is it once funny and provocative. What if, Chabon supposes, the United States had opened Sitka, Alaska, as a temporary refuge for European Jews fleeing Hitler, and what if the fledgling state of Israel had been conquered in 1948? The resulting world weaves together American, European-Jewish, and Tlingit Alaskan Native cultures, a world that is at once culturally rich and sad.

The story picks up 60 years after the refuge’s establishment, when the land is about to revert to U.S. rule. On page one, we’re introduced to Meyer Landsman, an embattled, alcoholic detective, and the dead body of Mendel Shpilmen, the son of a well-respected rebbe, who also happens to be something of a crime boss in the region. Both are presently occupying the same flea-bag motel, and Landsman feels a strong empathy for the dead young man, who was once a figure of promise and intrigue in Sitka.

The pressure is on for the Jewish police department to close their cases, pack their bags, and get out of the way for the Americans who are taking over, which adds a hurry-up factor to Landsman’s investigation. Further complicating things is the fact that Landsman’s boss at the soon-to-be-defunct department is his ex-wife, and relations between them remain a mix of bitterness and longing.

What Chabon does with this odd mix of ingredients is both thrilling and heartbreaking. The tone of his writing is, in many ways, a Raymond Chandler-style hard-nosed detective story, but the spiritual and political backdrop of the story serves to heighten the tensions and further illuminate the characters at the foreground. Landsman has no homeland, no family, and no ties to the world he inhabits. He travels amongst Sitka’s citizens—most of whom are far more faithful, ambitious, and serious than he—trying to both solve the crime and untangle the mess of his own life.

The dead man’s story reveals a broad sense of homesickness and exile in Sitka’s Jewish community, and paints a startling picture of messianic longing. Redemption, for many of the Sitka exiles, seems only possible through violence, and I found Chabon’s story illuminating (albeit in an odd, sideways kind of way) of the longing that must have occupied a large part of the hearts of the authors of the New Testament. And like that (truer, better) story, the redemption that Landsman finds is much more simple, sad, and surprising than anyone could have dreamed on their own.

September 19, 2014

Tony Woodlief: A Novel Every Christian Should Consider Reading

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

Tony Woodlief is a writer who lives in North Carolina.

His essays have appeared in The Wall Street Journal and The London Times, and his short stories appeared in Image, Ruminate, Saint Katherine Review, and Dappled Things.

He is also the author of the book, Somewhere More Holy: Stories from a Bewildered Father, Stumbling Husband, Reluctant Handyman, and Prodigal Son.

His website is www.tonywoodlief.com.

God’s grace is freely given to humanity, but novels should earn it. We’ve all endured ones that don’t, that brim instead with what Dietrich Bonhoeffer called “cheap grace,” reading more like sentimental greeting cards than stories of actual lives. In the real world we work out our salvation with fear and trembling, while the wicked revel. Our grief is tainted with bitterness, our joy with envy, our righteous anger with pride. These truths persist because our hearts, Jeremiah says, are deceitful and dreadfully sick. Any novel that does not reflect this is lying.

God’s grace is freely given to humanity, but novels should earn it. We’ve all endured ones that don’t, that brim instead with what Dietrich Bonhoeffer called “cheap grace,” reading more like sentimental greeting cards than stories of actual lives. In the real world we work out our salvation with fear and trembling, while the wicked revel. Our grief is tainted with bitterness, our joy with envy, our righteous anger with pride. These truths persist because our hearts, Jeremiah says, are deceitful and dreadfully sick. Any novel that does not reflect this is lying.

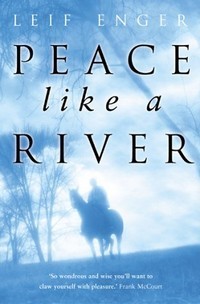

Leif Enger’s Peace Like a River does not lie, but this is not the reason you should read it. You should read it because it is earnest and beautiful in a world of smirks and ugliness, yet more realistic about fallen man than most grim-eyed modern novels wallowing in weltschmerz.

Here is the book’s narrator, recounting the story of his stillbirth:

“In these cases,” said Dr. Nokes, “we must trust in the Almighty to do what is best.” At which point Dad stepped across and smote Dr. Nokes with a right hand, so that the doctor went down and lay on his side with his pupils unfocused. As Mother cried out, Dad turned back to me, a clay child wrapped in a canvas coat, and said in a normal voice, “Reuben Land, in the name of the living God I am telling you to breathe.”

And Reuben did, because miracles fall from his father, Jeremiah, like tears from his prophetic namesake. Yet this novel keeps in our minds what many Christian novels suppress: It is terrifying to fall into the hands of the living God. “A miracle,” Reuben explains, “is no cute thing but more like the swing of a sword.” That sword will swing many times as Reuben, with his father and sister, search for his wayward older brother, Davy.

Unlike Jeremiah and Reuben, Davy has no stomach for miracles. “You think God looks out for us?” he asks Reuben. “You want Him to?” Davy is repulsed by his father’s often-told story of being carried unharmed by a tornado. “It didn’t make sense,” he says. “It wasn’t right.” Davy is self-sufficient and cynical. He is what sophisticated types call a realist.

It is Jeremiah who is the true realist, however, because he walks open-eyed through a Christ-haunted world. It’s a world where all things work together for good, to those who love God, just as the Bible promises. But unlike a sentimental storybook, that good isn’t always apparent on this side of the veil. When his children ask what they should do, following a tragedy, Jeremiah simply says: “‘Persevere.'”

“It was a better answer,” Reuben says, “than we wanted.” Thankfully that can’t be said of this novel, which was a bestseller. It reached beyond a Christian audience not despite being permeated with faith, but because of it, because everyone senses the truth in Jeremiah’s admonition:

“We and the world, my children, will always be at war.

Retreat is impossible.

Arm yourselves.”

September 18, 2014

Sarah Kinnard: A Novel Every Christian Should Consider Reading

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

Sarah Kinnard studied English and Education at Wheaton College.

A former middle and high school English teacher, she now homeschools her own children and tries to squeeze in a morning run and a little reading.

She blogs at goingsgraces.wordpress.com.

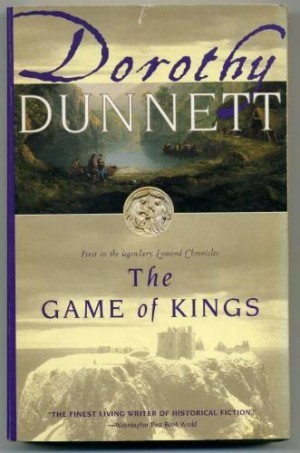

Dorothy Dunnett’s novel The Game of Kings opens a six-book series that is spectacularly written, exhaustively researched, profoundly thought-provoking, and utterly absorbing. As far as I know, Dunnett was not a Christian, nor are her main characters. But her books illuminate the histories of cultures, nations, and individuals in ways Christians would do well to ponder. I think they are novels every Christian should consider reading.

Dorothy Dunnett’s novel The Game of Kings opens a six-book series that is spectacularly written, exhaustively researched, profoundly thought-provoking, and utterly absorbing. As far as I know, Dunnett was not a Christian, nor are her main characters. But her books illuminate the histories of cultures, nations, and individuals in ways Christians would do well to ponder. I think they are novels every Christian should consider reading.

The Lymond Chronicles actually form one continuous story with the seven-volume House of Niccolò series that follows. I’d start by recommending the entire cycle to you, but I don’t want to scare you off. So I will focus on Lymond, sure that anyone who is entranced, like me, by Dunnett’s story will be compelled to read the whole thing.

Francis Crawford of Lymond is a complex figure of fabulous talents and deep wounds. He is looking for a leader worth following and a nation worth serving, and for a purpose that will conquer his past. Dunnett sets her books in the flowering Renaissance, sweeping toward the upheaval of the Reformation, amid all the chaos and opportunity of that rapidly changing world. In such a time, a brilliant man could access the levers of history by using his gifts in the service of kings. Lymond does not seek power for himself; he seeks a monarch who will let him help shape an unsteady young country into greatness. In Dunnett’s world, that ideal arena is her beloved Scotland, poised here between a turbulent past and a stable future. We know from history that this conflict-scarred land is soon to become one half of a remarkable compromise that will secure a Protestant United Kingdom and produce the King James Bible. Dunnett places her fictional characters in the meticulously drawn historical scene, giving a glimpse of how such massive changes might have been wrought.

The future, both of nations and families, is of deep concern to Dunnett. Lymond grapples with the identity dealt to him and the heritage he will pass on in turn. He carries a hidden anguish at the injustice that has dogged his steps, but he continues to make choices that befuddle the reader and alienate those who love him—because he is working toward a future that he sees more clearly than anyone else. In the metaphorical (and sometimes literal) chess match alluded to in the titles of all six books, Lymond operates several moves ahead, often misunderstood and reviled by those he has silently shielded and saved. Ultimately, he sacrifices justice for love; rather than claiming what is due him, he chooses to pass on the heritage of one to whom love and loyalty mean more than fairness.

Though he sometimes acts in ways we would consider immoral, Lymond actually lives by a very specific moral code, with motives much better than they first appear. Christians may not agree that his ends justify his means, but the dilemmas he faces are worth discussing: what constitutes true loyalty? How does one unmask a hypocrite whom everybody loves? What sorts of hurts can be forgiven? And most importantly, what makes a life worth continuing?

Dunnett tackles these heavy questions sidelong, through story. Her prose is vivid and dense, and it rewards careful reading. Like many great stories, it can take a while to draw you in; so don’t give up too early. Keep reading, and you’ll be glad you did. A note: though they take up both the theological (Reformation) and mystical (astrology and second sight) ideas of the time, these are not what one might call “Christian” fiction. Instead, they explore some of the darker realities of the broken world—in which Christians, both then and now, have to live. There are portrayals of sin, but no wallowing in it.

Reading novels is not a utilitarian exercise in self-improvement, but in a mysterious way, if we read the right kinds of books, they do improve our selves—they transport us out of our necessarily small and bounded worlds to other times, other places, and a variety of human hurt and happiness which no one person could ever experience. Such novels can make us better people, more compassionate, more observant, more thoughtful. As swashbuckling adventure tales, the Lymond Chronicles certainly meet the hedonistic criterion for literature mentioned by Dr. Ryken (my favorite college English professor), for they are immensely enjoyable. I also think they enlarged my heart, and I am better for it.

September 17, 2014

An Interview on “The Unfinished Church”

I recently enjoyed talking with Rob Bentz about his new book, The Unfinished Church: God’s Broken and Redeemed Work-in-Progress:

Timestamps

00:13 – Tell us a little about yourself.

00:30 – Why did you choose “unfinished” as the main metaphor you use to describe the church?

02:09 – What sets this book apart from other books about the church?

03:31 – What do you think of the statement, “I love Jesus . . . it’s the church I can’t stand”?

04:46 – What do you mean when you talk about the “church of the mirror”?

05:44 – Why is genuine biblical encouragement so important for the church?

07:00 – How does the ongoing process of sanctification relate to the ongoing presence of sin in the church?

Learn more about the book and download an excerpt.

Russell Moore: A Novel Every Christian Should Consider Reading

Russell D. Moore (PhD, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary) is President of the Southern Baptist Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission, the Southern Baptist Convention’s official entity assigned to address social, moral, and ethical concerns.

Russell D. Moore (PhD, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary) is President of the Southern Baptist Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission, the Southern Baptist Convention’s official entity assigned to address social, moral, and ethical concerns.

He blogs frequently at his “Moore to the Point” website, and is the author or editor of five books, including Tempted and Tried: Temptation and the Triumph of Christ, Adopted for Life: The Priority of Adoption for Christian Families and Churches, and The Kingdom of Christ: The New Evangelical Perspective.

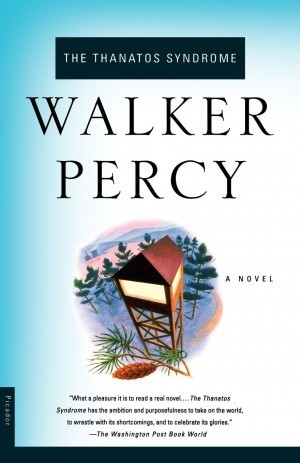

Imagine Left Behind if what were raptured were not persons but inhibitions. That still wouldn’t be this novel. You would have to further imagine the book showcasing zombies with nothing much left of their humanity but their appetites, combated by a physician with a tendency toward witty asides about culture, religion, and human psychology. And you’d have to further imagine the novel written by an Old Testament prophet with literary superpowers peering into the future set before us. Then you’d start approaching what Walker Percy’s The Thanatos Syndrome is like, and why you should read it.

Imagine Left Behind if what were raptured were not persons but inhibitions. That still wouldn’t be this novel. You would have to further imagine the book showcasing zombies with nothing much left of their humanity but their appetites, combated by a physician with a tendency toward witty asides about culture, religion, and human psychology. And you’d have to further imagine the novel written by an Old Testament prophet with literary superpowers peering into the future set before us. Then you’d start approaching what Walker Percy’s The Thanatos Syndrome is like, and why you should read it.

Walker Percy (1916-1990) was the heir of one of Mississippi’s most powerful political and literary families. He was medical doctor in Covington, Louisiana (round about New Orleans) with expertise in philosophy and semiotics. He was also a keen observer of popular culture. When visiting with the literary genius Eudora Welty, it’s reported that they were overheard discussing not Faulkner or Chekhov but The Incredible Hulk. He was a Christian deeply immersed in the thought of Augustine and Søren Kierkegaard. And he was estranged enough from American culture to be able to watch it, as though from afar.

The protagonist of this novel, Percy’s last, is an alcoholic physician who’s done some jail-time, and has now returned home to find that the cast of characters is the same as he left them, but they seem to be reading from a different script. He discovers that his neighbors are being pharmaceutically engineered in a way that removes their human troubles, their human fears, their human reluctances, but, with all of that, it seems, their humanity itself.

The story is brisk, and fun, in its own right, but embedded in the story is a jeremiad of what Percy saw bubbling beneath the surface of American culture. Taking aim at a kaleidoscope of targets, Percy gives us More, to the point. At the heart of his prophetic critique is the division of body from soul.

This starts with the book’s view of science, which divides body from soul by replacing the concept of soul altogether. Near the beginning of the novel, Dr. More complains that psychologists who actually believe in a psyche are near extinct, replaced by “brain engineers” who reduce everything to synapses and chemicals. “If one can prescribe a chemical and overnight turn a haunted soul into a bustling little body, why take on such a quixotic quest as pursing the secret of one’s very own self?”

This quest for engineered happiness, at the heart of the narrative, is what happens when abstract reason and data replace the mystery of human existence. The result of rationalism isn’t, ultimately cool detachment, but hedonism. He sums up the thought of B.F. Skinner this way: “The object of life is to gratify yourself without getting arrested.”

This wild coldness that starts with the dehumanization of the self continues toward the dehumanization of others. And that begins with words. “Neonates” are infants and “euthanates” are the elderly, both of whom are killed. In a cunning use of language, the Supreme Court does not deprive them of a right to life, but instead rules for them, with a “right to death.” The infants are lacking in a right to life because they are not conscious of themselves, and if self-consciousness is what it means to be human, well, then what are they?

The cruel experiments at the heart of this book are pictured not as self-consciously cruel, but as attempts at philanthropy, to “fix” what’s wrong with people. It turns out thought that if one doesn’t know, as Wendell Berry would put it, “what people are for,” this is awful. And if one no longer knows what humanity is, one can kill without ever feeling bloodthirsty. In fact, you can feel as though you are saving the world.

The body/soul division shows up not just in secularizing, utopian science but also in American religion. Percy was, I think, the keenest observer in our time of the almost-gospels of the Bible Belt. He talks here about “educated Episcopal-type unbelievers,” who need the social cache of religion but not much else. He mentions that Louisiana is more Christian than ever, “not Catholic Christian but Texas Christian.”

Even this enthusiastic evangelicalism, though, is often a matter of fitting into the culture. These Cajuns were converted, he notes “first by Texas oil bucks, then by Texas evangelists.”

These evangelicals are hard-working, dependable, quick to call one “brother” and to shout “Hallelujah” in conversation. More says, “I’ve nothing against them, but they give me the creeps.”

In the character of Ellen, he describes a woman who makes the trek from southern Presbyterianism to Pentecostalism, put off by the liberalism of mainline Protestantism. Her new birth, though, disconnected spirit from matter, in her mind. “She loves the Holy Spirit but says little about Jesus,” he reflects. This, like the move from psychology to psychopharmacology, has consequences.

“She is herself a little holy spirit hooked up to a lusty body,” he says. “In her case the spirit has nothing to do with the body. Each goes its own way.” This shows up in her attitude toward the Lord’s Supper, which she sees as “Catholic trafficking in bread, wine, oil, salt, water, body, blood, spit—things. What does the Holy Spirit need with things? Body does body things. Spirit does spirit things.”

As with science, this sort of disconnection of soul from body, doesn’t stop carnality; it just results in the worst sort of carnality, that without a soul or conscience.

Every Christian should read this novel because in it you will start to see why some of the ethical anarchy around us is happening. You’ll recognize a society that thinks it can medicate away the fear of death, a society that thinks human existence is the sum total of neurons firing. You’ll recognize why, for instance, the advocates of abortion rights increasingly no longer bother to argue that unborn life isn’t human. One need only argue that it isn’t happy, and there are always those who can “fix” unhappiness with a pill or a scalpel.

But, at the same time, Percy’s novel isn’t a politicized caricature of why the other side must be stopped. There are not villains of all-encompassing wickedness and heroes of imitable virtue. The culture of death, in this book, isn’t just a political issue or a cultural force or a “worldview.” It’s a spirit of the age that is cunning enough not to stay on just one side of culture war fence. In this book, Percy shows us the culture of death—and shows us our own faces there. Like all prophets worth the name, he recognizes that judgment starts with the household of God.

September 16, 2014

John Wilson: A Novel Every Christian Should Consider Reading

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

John Wilson is editor of Books & Culture and editor at large for Christianity Today magazine.

Wilson received a B.A. from Westmont College in Santa Barbara, Calif., in 1970 and an M.A. from California State University, Los Angeles, in 1975.

His reviews and essays appear in the New York Times, the Boston Globe, First Things, National Review, Commonweal, and other publications.

He and his wife, Wendy, are members of Faith Evangelical Covenant Church in Wheaton; they have four children.

“Why don’t these writers just say what they mean?”

“Why don’t these writers just say what they mean?”

The speaker, clearly exasperated, was a distinguished theologian. The setting was a discussion among roughly eighteen people from various walks of life (two-thirds of them academics) who had read some interesting texts together, more or less equally divided between theology and literature. The theologian, as you might guess, was reacting to the literary texts on the table (works by Dostoevsky and Flannery O’Connor, for instance): shifty, hard to pin down.

Fiction is often like that, and some fiction in particular—the fiction of Muriel Spark, for instance. Spark (1918-2006) did not publish her first novel until she was thirty-nine years old, three years after her conversion to Catholicism. But having made this late debut, she never stopped writing superb novels; her last, The Finishing School, appeared when she was eighty-six. She may be best known for The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, which was made into a movie starring Maggie Smith. My own favorite among her books is Memento Mori, but you could close your eyes and pick one of her novels from the shelf at random and not go wrong.

Your hand might fall on The Only Problem, which was published in 1984. Here is the first paragraph:

He was driving along the road in France from St Dié to Nancy in the district of Meurthe; it was straight and almost white, through thick woods of fir and birch. He came to the grass track on the right that he was looking for. It wasn’t what he had expected. Nothing ever is, he thought. Not that Edward Jansen could now recall exactly what he had expected; he tried, but the image he had formed faded before the reality like a dream on waking. He pulled off at the track, forked left and stopped. He would have found it interesting to remember exactly how he had imagined the little house before he saw it, but that, too, had gone.

Notice how the book begins with the confident precision we associate with a kind of fiction that gets called (with a straight face) “realistic,” and yet by the third sentence the ground has already begun to shift under our feet. “It wasn’t what he had expected. Nothing ever is, he thought.” The often shifty quality of fiction turns out (in one respect) to be truer to our experience than any “just the facts” chronicle.

This novel has an epigraph from the Book of Job: “Surely I would speak to the Almighty; and I desire to reason with God.” Edward, whom we met in the first paragraph (formerly a vicar, now an actor), has come to France to see his wealthy friend Harvey, who has been working for some time on a book about Job “and the problem it deals with. For he could not face that a benevolent Creator, one whose charming and delicious light descended and spread over the world, and being powerful everywhere, could condone the unspeakable sufferings of the world. . . . ‘It’s the only problem,’ Harvey had always said.”

How the unfolding events of the novel—quite a short one, as was typical of Spark, without a word wasted—shed light on this “problem” is for you to discover. (Certainly, you will say at the end, “it was not what I expected.”) Are Harvey’s nagging questions answered? Do they admit to a human answer?

If you find The Only Problem to your taste, you have a lot more Spark to savor. But even if you stop after this book, I don’t think you will have wasted your time.

September 15, 2014

Kathleen Nielson: A Novel Every Christian Should Consider Reading

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

I am doing a blog series on Novels Every Christian Should Consider Reading.

Kathleen B. Nielson (PhD in literature, Vanderbilt University) serves as director of women’s initiatives for The Gospel Coalition.

Author of the Living Word Bible Studies, she speaks often at women’s conferences and loves working with women in studying the Bible. Her latest book, co-edited with D. A. Carson, is Here Is Our God: God’s Revelation of Himself in Scripture.

Till We Have Faces is C. S. Lewis’ final novel—and a favorite of Lewis himself. That might be enough reason to read it. The problem is that, once you’ve read it, you have to read it again. It’s not that you don’t get it the first time. It’s that you want to get the layers of it. This novel keeps unfolding in remarkable ways, on repeated readings.

What unfolds is not a new story but a retelling of the myth of Cupid and Psyche, set by Lewis in a little kingdom called Glome somewhere north of Greek lands, several hundred years B. C. His tale is as universal as the stuff of myths but as concrete as the frozen spills of milk and puddles and dung in the palace courtyard where the children are sliding as the book opens. It is narrated in first person by Glome’s Queen Orual, Psyche’s sister, with the stated purpose of accusing the gods. Part I is Orual’s charge, her record of how the gods have taken away her beautiful beloved Psyche.

Lewis creates a strong, clear, personal voice for this intelligent woman who rules long and well with a veil covering her ugly face (and relentless work veiling her broken, bitter heart). Through Orual he reveals the struggle to believe in what is invisible. He is telling the story of faith—his own story, and the story of every person who comes to believe in God.

The crucial change in Lewis’ version of the myth is that the shining palace where Psyche goes to live with her god-husband is made invisible to mortals (except Psyche). Orual does not see it (except for a fleeting glimpse). On this basis she justifies her actions that destroy her loved-one’s happiness. How could Orual have known it was all real? Why do the gods not show themselves? Orual lives out the struggle to reconcile the light of reason (shown by “Fox,” Orual’s Greek tutor) with the more opaque, mysterious realm (shown by Glome’s gods) where blood sacrifices must be made.

Struggle to see the gods is at the heart of Orual’s struggle to see herself, in light of them. Orual shows us the process of confronting both self-deception and bare truth about who we fallen human beings are. It is wonderful to come to Part II, which Orual writes because, in a climactic moment of vision when called to read her charge (Part I) before the gods, she sees she has not told her story truly. She has called “love” what was not love but self-serving jealousy. She has refused to see. She has veiled her face and hidden from herself. But now at last she sees herself:

When the time comes to you at which you will be forced at last to utter the speech which has lain at the center of your soul for years, which you have, all that time, idiot-like, been saying over and over, you’ll not talk about the joy of words. I saw well why the gods do not speak to us openly, nor let us answer. Till that word can be dug out of us, why should they hear the babble that we think we mean? How can they meet us face to face till we have faces?

The light of true seeing pierces through, at this novel’s end. There is a Job-like answer to Orual’s charge, and there is the kind of losing oneself and finding oneself that happens ultimately only in Christ.

Of course, having finished, you want to go back and read Part I again, in light of Part II. With each rereading comes a bit more light, as this novel’s layers masterfully unfold.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers