Justin Taylor's Blog, page 276

October 12, 2011

On Defining the Label "Celebrity Pastors" (Updated)

Thabiti Anyabwile has a good post here, trying to work through the definition(s) of "celebrity" that is often used as a term of derision toward some prominent evangelical pastors.

Thabiti Anyabwile has a good post here, trying to work through the definition(s) of "celebrity" that is often used as a term of derision toward some prominent evangelical pastors.

Here's the upshot of the article: "It's better to describe and explain what we're talking about than to use the label that miscommunicates so much."

And here's his conclusion:

If you don't know what a word or phrase means, don't use it. Plain and simple. Know what you're talking about, otherwise avoid that term. This entire "celebrity" discussion reminds me of that principle. Until we know what we're talking about, we should avoid the terms—especially when there are more respectable ways of referring to prominent people, like "prominent," "high-profile," "public" and so on. As Christians, we should show honor even when we're attempting to point out serious problems.

Agree or disagree, the whole post is worth reading, not least for the attempt to work out the distinctions and the definitions.

Update: Carl Trueman responds with a perspective also worth hearing. Conclusion:

Call it what you like. I call it the culture which grows up around celebrities. Maybe I am hopelessly wrong in my choice of terms. You may certainly choose others which fit better. But like internet pornography, I would rather spend time exposing the problems for what they are than debating semantic qualifications.

You can read his whole post here.

Some Tips for Interpreting the Rituals, Ceremonies, & Sacrifices in Leviticus

The Introduction to Leviticus in the ESV Study Bible is helping in sorting through some of the foreign concepts we find in the book. For example, Moses uses unclean, clean, and holy differently than we use these terms today.

The Introduction to Leviticus in the ESV Study Bible is helping in sorting through some of the foreign concepts we find in the book. For example, Moses uses unclean, clean, and holy differently than we use these terms today.

With "unclean" and "clean," for example, most modern readers are tempted to think of that which is "nonhygienic" or "hygienic."

In Leviticus, however, these words do not refer to hygiene at all. Rather, they refer to "ritual states." (The word "holy" is also used in many contexts to describe a ritual state.) Understanding the concept of ritual states is very important to understanding Leviticus as a whole.

In Leviticus there are three basic ritual states:

the unclean

the clean, and

the holy.

On the one hand, these categories guide the community with reference to the types of actions a person may (or may not) engage in, or the places that a person may (or may not) go. Those who are unclean, e.g., may not partake of a peace offering (7:20), while those who are clean may (7:19). (A modern analogy might be that of registering to vote: a person who is "registered" may vote, whereas a person who is "unregistered" may not.)

There is an important distinction between "ritual states" and "moral states."

One who is in the ritual state of holiness is not necessarily more personally righteous than a person who is simply clean or unclean (just as a person who is "registered" to vote is not necessarily more righteous than a person who is not).

Though they are distinguished, we should be careful not to separate them:

Even though ritual states and moral states are different, the ritual states also seemed to represent or symbolize grades of moral purity.

The highest grade of moral purity was that of the Lord himself, who was "holy" and who dwelt in the "Holy of Holies."

By constantly calling the Israelites to ritual purity in all aspects of life, the Lord was reminding them of their need for also seeking after moral purity in all aspects of life (20:24-26).

Another challenge in Leviticus is knowing how to interpret and apply the rituals and ceremonies.

In particular, how should the individual acts and objects that make up a ritual be understood? Answering this question can be difficult, for the simple reason that Leviticus rarely explains what various ritual actions or objects mean. (One of the few exceptions is 17:11, where sacrificial animal blood is said to be the "life" of the animal.)

Some help is provided, however, by asking questions about the general function(s) and the specific function(s) of the ritual.

Generally speaking, rituals may function in several ways: e.g.,

to address aspects of the human condition (such as impurity or sinfulness),

to serve as a way for the offerer to express emotions or desires to the Lord, and

to underscore various truths about the Lord or the human condition.In many instances, one ritual may accomplish all of these things.) It is helpful to ask which of these general functions is in view in the ritual being considered.

Related to this, one should also ask, "What is the specific goal/function of this particular ritual as a whole?"

Answering these two questions provides an interpretative framework in which to understand the individual actions of the ritual (much as a paragraph is an interpretative framework for the sentences in it). For example, if a ritual as a whole is meant to express an emotion (general), and more specifically to express praise (specific), then the individual actions or objects of the ritual should somehow contribute to this goal.

Though this approach may still leave some questions unanswered, it will usually provide helpful guidelines and protect readers from some of the interpretative excesses of the past.

In his introductory textbook Exploring the Old Testament: A Guide to the Pentateuch Gordon Wenham makes an important point about the importance of the imagination in interpreting the sacrifices in Leviticus:

It is very difficult for modern readers to picture the sacrifices described in Leviticus, because they, unlike ancient Israelites, have never seen, let alone participated in a sacrifice. What we really need is a video showing all the different kinds of sacrifices, the burnt offerings, the peace offering, the sin offering, and so on! Just as the stories in the Old Testament are designed for reading aloud, not silently, so these ritual texts are meant for people who already have a good idea of how to sacrifice. They are just underlining important or controversial points, so that anyone offering a sacrifice would do it in a way acceptable to God.So how can we proceed? The best way is to act them out, or alternatively, if one is more artistically inclined, produce a sort of comic strip showing each step in action. Then it becomes much easier to grasp the steps in the process and see the direction of the ceremony. But it will also show up the gaps in the instructions, things that the first readers just took for granted.

For example, Leviticus never says that the sacrificial animals had to have their legs tied before being killed. But this was the procedure in other parts of the ancient Near East and Genesis 22:9 suggests it was done in ancient Israel.

Another thing that Old Testament nearly always leaves out are the words said or sung during the ceremonies. But one can hardly suppose that the worshipper did not explain to the priest why he was bringing a sacrifice or afterwards that the priest did not give some assurance that the sacrifice had been accepted.

In Leviticus one has the rubric setting out how a ceremony is to be performed, but none of the accompanying words. It is often surmised that the Psalms were used in temple services, presumably as the sacrifices were being carried out, but again there is no hint of this in Leviticus.

Therefore, readers need to use much imagination to recreate the mood and atmosphere of the rites as well as attending carefully to the exact procedures set out in the text. (pp. 82-83)

For some more help and examples on preaching from Leviticus, this is a helpful resource.

Os Guinness: "Time for Truth: Living Free in a World of Lies, Hype, and Spin"

Os Guinness spoke at the Veritas Forum at Stanford University in 2002 summarizing his book Time for Truth: Living Free in a World of Lies, Hype, and Spin. He speaks for 45 minutes (I've outlined it below), and then he answers questions for 45 minutes.

Two companion crises to the crisis of truth:

The crisis of ethics

The crisis of character

Two arguments for truth (for believers):

The lesser argument: Without truth we cannot answer the fundamental objection that faith in God is simply a form of "bad faith" or "poor faith."

The greater argument: Truth matters infinitely and ultimately because it is a question of the trustworthiness of God himself.

Two arguments for truth (even for those who do not believe in it):

The negative argument: Without truth we are all vulnerable to manipulation.

The positive argument: Without truth there is no genuine freedom and fulfillment.

Two arguments for truth by Peter Berger (for those who are deeply skeptical)

The negative argument: The relativizers are relativized. Some truths can be argued but not lived.

The positive argument: Point out the signals of transcendence.

Truth has a double-challenge (for all of us)

Do we:

shape truth to our desires? or

shape our desires to truth?

In Defense of Proof-Texting

In the latest issue of of JETS—the Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 54.3 (September 2011) 589-606—Michael Allen (of Knox Theological Seminary) and Scott Swain (of Reformed Theological Seminary, Orlando) offer a helpful defense of (good) proof-texting.

Here is their opening:

Proof-texting has been maligned as of late, charged in the court of theological inquiry. Many biblical scholars snicker and jeer its employment, while many systematic theologians avoid guilt by association.

In this context, we wish to mount an argument in defense of proof-texting. In so doing, we claim neither to defend all that goes under the name of prooftexting, nor to dismiss its critics' charges. Rather we argue that proof-texting is not necessarily problematic. What is more, historically it has served a wonderful function as a sign of disciplinary symbiosis amongst theology and exegesis. We believe that a revived and renewed practice of proof-texting may well serve as a sign of lively interaction between biblical commentary and Christian doctrine.

For systematicians, they offer two suggestions:

1. "Systematic theologians must be aware of the burden of proof upon them to show that they are using the Bible well in their theological construction. They should seek to promote a biblically saturated culture amongst fellow evangelical systematic theologians."

Under this point, they suggest "two ways in which to promote a biblically saturated culture amongst evangelical systematic theologians."

a. "Engage in writing theological commentary (whether of whole books of the Bible or simply of particular passages in journal articles)."

b. "Enrich dogmatic arguments with a great deal of exegetical excurses and engagement with works of exegetical and biblical-theological rigor."

2. "Biblical scholars should expect rigorous exegesis to lie behind such proof-texting and should engage it conversationally and not cynically."

For those interested in the interplay between systematic theology and biblical theology, this is a good piece that points the way forward.

On Defining the Label "Celebrity Pastors"

Thabiti Anyabwile has a good post here, trying to work through the definition(s) of "celebrity" that is often used as a term of derision toward some prominent evangelical pastors.

Thabiti Anyabwile has a good post here, trying to work through the definition(s) of "celebrity" that is often used as a term of derision toward some prominent evangelical pastors.

Here's the upshot of the article: "It's better to describe and explain what we're talking about than to use the label that miscommunicates so much."

And here's his conclusion:

If you don't know what a word or phrase means, don't use it. Plain and simple. Know what you're talking about, otherwise avoid that term. This entire "celebrity" discussion reminds me of that principle. Until we know what we're talking about, we should avoid the terms—especially when there are more respectable ways of referring to prominent people, like "prominent," "high-profile," "public" and so on. As Christians, we should show honor even when we're attempting to point out serious problems.

Agree or disagree, the whole post is worth reading, not least for the attempt to work out the distinctions and the definitions.

When You Shouldn't Adopt

From Russell Moore's post "Don't Adopt!"

Children shatter your life-plan. Adoption certainly does.

It's worth it.

But Jesus tells us we ought to know that a king going into battle must measure his troops, a tower-builder must count the expenses of the project (Lk. 14:28-31). Those who see adoption as a warm, sentimental way of having a baby are mistaken and dangerous. There are far too many who plunge in without counsel, without a commitment to fidelity no matter what. They search around for a baby who fits their specifications. And babies never fit your specifications…at least not when they grow up.

If what's behind all of this isn't crucified, war-fighting, eyes-open commitment, you are going to wind up with a child who is twice orphaned. He or she will be abandoned the first time by fatherlessness and the second time by the rejection of failing to live up to the expectations of parents who had no business imposing such expectations in the first place.

We need a battalion of Christians ready to adopt, foster, and minister to orphans. But that means we need Christians ready to care for real orphans, with all the brokenness and risk that comes with it. We need Christians who can reflect the adopting power of the gospel, which didn't seek out a boutique nursery but a household of ex-orphans who were found wallowing in our own blood, with Satan's genes in our bloodstreams.

If what you like is the idea of a baby who fulfills your needs and meets your expectations, just buy a cat. Decorate the nursery, if you'd like. Dress it up in pink or blue, and take pictures. And be sure to have it declawed.

You can read the whole thing here.

The Closing of the American Bookstore

Magers & Quinn in Uptown, Minneapolis

Dan Gregory from Between the Covers Rare Books has an insightful post here about the closing of bookstores like Serendipity Books in Berkeley, CA, and the original Borders Books in Ann Arbor, MI.

Here is his conclusion:

Owning and operating a bookstore has NEVER been an easy way to make a living. But booksellers are an obstinate and romantic lot. From their corps arise, from time to time, people with enough business sense to actually support their Quixotic dreams. Serendipity and Borders have closed, but independent bookstores like them will always be around.

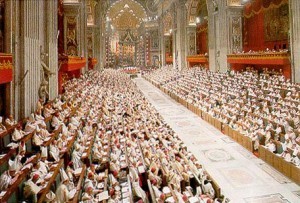

A Primer on Vatican II for Protestants

"Yesterday was the anniversary of the opening of the Second Vatican Council. Forty-nine years later, many Protestants (like me) still have no idea what our Catholic friends are talking about when they refer to the changes in Catholicism that occurred because of that council. Fortunately, evangelical theologian Fred Sanders has put together a brief primer (based on a work by Avery Dulles) that explains some of the key issues."

October 11, 2011

Carson and Keller on The Gospel Coalition, Confessionalism, Boundaries, & Acccountability

This is a helpful, clarifying, insightful statement from D. A. Carson and Tim Keller with regard to The Gospel Coalition, The Elephant Room, and the broader issues of confessionalism, boundaries, and accountability. I encourage you to read the whole thing, but I've taken the liberty of outlining the main points below.

Recent discussion, mostly in blogs, regarding the forthcoming Elephant Room conference, sponsored by James MacDonald and Mark Driscoll, provides an opportunity to write a few clarifying paragraphs on confessionalism, boundaries, and discipline.

Whatever else The Gospel Coalition has or has not done, it has not prohibited mutual criticism among Council members. We disagree not only on some historic dogmatic matters (e.g., baptism, church governance) but also on an array of pastoral judgments (e.g., multi-site churches, approaches to evangelism)—which are of course themselves grounded in our respective understandings of theological issues. On some matters where all Council members are on the same "side" (e.g., complementarianism), we find ourselves in somewhat different places when it comes to implementing our shared theological commitments. At the same time, the richness and detail of our Confessional Statement and our Theological Vision of Ministry demonstrate that we wish to avoid lowest-common-denominator theology. But how do we negotiate the difficult occasions when our foundation documents appear to be skirted, or where boundaries become too porous?

Carson and Keller offer seven reflections:

"From the beginning TGC has distinguished between a boundary-bounded set and a center-bounded set. . . . For TGC, the center is defined by our Confessional Statement (CS) and Theological Vision of Ministry (TVM) and sustained by the Council members. There we expect unreserved commitment to these foundation documents."

"If someone on our Council espouses something not in line with our CS and TVM, that person is challenged. . . . In other words, at the center there is unqualified accountability."

"The kind of allegiance to the gospel and the Scriptures we expect at the center, expressed in our CS and TVM, extends beyond mere personal allegiance. . . . The most recent kerfuffle in TGC was initially precipitated when James MacDonald (as he has acknowledged), though he espoused the doctrine of the Trinity classically understood, gave the impression that other formulations might be acceptable—formulations that sounded a great deal like modalism (Sabellianism). James has turned away from some of what he wrote: a modalist God, he has told some of us repeatedly, cannot save. James was not the first to be challenged on something he said, and will doubtless not be the last. So far as our CS and TVM are concerned, Council members must not be 'in process of re-thinking' fundamental matters: for us, they are settled."

"Within these bounds, Council members discharge ministries that are highly diverse, with their own networks, specific aims, and relationships with many people outside the Council. . . . But those are judgment calls."

"One of the things that brought James MacDonald's associations in the Elephant Room into dispute was another factor that cannot be ignored. . . . The problem with the Elephant Room was that as initially envisaged it was designed to bring together Christian brothers. To invite someone to such a gathering where that person has not, at the very least, distanced himself from the modalism in which he was reared and which is at odds with Christian convictions in every branch and corner of orthodox Christendom, seemed not only to lack wisdom but to allow tolerance levels to rise to the point where confessionalism is being swamped (see our third point, above). In fact, the design and purposes of the Elephant Room changed at a rate of speed that eclipsed its mission statement. James has in recent days tried to set the record straight. Many, we suspect, will now wait and see how the hosts of the Elephant Room handle themselves and interact with their guests in the sessions ahead. If they do so with understanding of the truths they discuss, coupled with firmness on the one hand and courtesy on the other, they will go a long way toward stilling doubts. If (God forbid) they were to give the impression that foundational Christian truths do not matter, inevitably serious questions will be raised, and rightly so."

"We suspect that some of the blog exchanges on this subject have slipped past one another in indignant disarray because one party was calling for gospel cohesion and the other was calling for a charitable answer to the question of who may be saved."

"The blogosphere encourages very rapid responses. Sometimes that enables Christians to address challenges in a timely way. . . . But the blogosphere's very speed sometimes encourages polarized or intemperate responses before enough time has elapsed for faithful and mature thought to put things in perspective."

Spurgeon's One Qualm with Pilgrim's Progress

Charles Spurgeon loved John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress. He first read the book as a young boy, and he began his commentary on the classic with these words: "Next to the Bible, the book I value most is John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress. I believe I have read it through at least a hundred times. It is a volume of which I never seem to tire; and the secret of its freshness is that it is so largely compiled from the Scriptures." As Spurgeon said elsewhere, he loved Bunyan because Bunyan bled Bible.

But he did have one qualm with the great book:

Painting by Mike Wimmer

I am a great lover of John Bunyan, but I do not believe him infallible; and the other day I met with a story about him which I think a very good one.

There was a young man, in Edinburgh, who wished to be a missionary. He was a wise young man; he thought—"If I am to be a missionary, there is no need for me to transport myself far away from home; I may as well be a missionary in Edinburgh." . . .

Well, this young man started, and determined to speak to the first person he met. He met one of those old fishwives; those of us who have seen them can never forget them, they are extraordinary women indeed. So, stepping up to her, he said, "Here you are, coming along with your burden on your back; let me ask you if you have got another burden, a spiritual burden."

"What!" she asked; "do you mean that burden in John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress? Because, if you do, young man, I got rid of that many years ago, probably before you were born. But I went a better way to work than the pilgrim did. The evangelist that John Bunyan talks about was one of your parsons that do not preach the gospel; for he said, 'Keep that light in thine eye, and run to the wicket-gate.' Why—man alive!—that was not the place for him to run to. He should have said, 'Do you see that cross? Run there at once!' But, instead of that, he sent the poor pilgrim to the wicket-gate first; and much good he got by going there! He got tumbling into the slough, and was like to have been killed by it."

"But did not you," the young man asked, "go through any Slough of Despond?"

"Yes, I did; but I found it a great deal easier going through with my burden off than with it on my back."

The old woman was quite right. John Bunyan put the getting rid of the burden too far off from the commencement of the pilgrimage. If he meant to show what usually happens, he was right; but if he meant to show what ought to have happened, he was wrong.

We must not say to the sinner, "Now, sinner, if thou wilt be saved, go to the baptismal pool; go to the wicket-gate; go to the church; do this or that."

No, the cross should be right in front of the wicket-gate; and we should say to the sinner, "Throw thyself down there, and thou art safe; but thou are not safe till thou canst cast off thy burden, and lie at the foot of the cross, and find peace in Jesus."

Sermon: "The Dumb Become Singers"

HT: Tony Reinke

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers