Justin Taylor's Blog, page 274

October 18, 2011

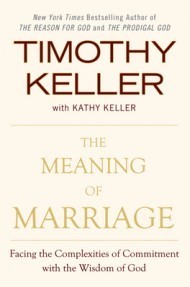

An Outline of the Kellers' Book on Marriage

From the introduction to Tim and Kathy Keller's The Meaning of Marriage: Facing the Complexities of Commitment with the Wisdom of God:

From the introduction to Tim and Kathy Keller's The Meaning of Marriage: Facing the Complexities of Commitment with the Wisdom of God:

* * *

The substance of this book draws on St. Paul's great passage on marriage in Ephesians 5, not only because it is so rich and full in itself, but also because it connects and expounds on the other most important Biblical text on marriage, Genesis 2.

In chapter 1 ["The Secret of Marriage"], we put Paul's discussion into today's cultural context and lay out two of the most basic teachings by the Bible on marriage—that it has been instituted by God and that marriage was designed to be a reflection of the saving love of God for us in Jesus Christ. That is why the gospel helps us to understand marriage and marriage helps us to understand the gospel.

In chapter 2 ["The Power for Marriage"], we present Paul's thesis that all married partners need the work of the Holy Spirit in their lives. The work of the Spirit makes Christ's saving work real to our hearts, giving us supernatural help against the main enemy of marriage: sinful self-centeredness. We need the fullness of the Spirit if we are to serve one another as we should.

Chapter 3 ["The Essence of Marriage"] gets us into the heart of what marriage is all about—namely, love. But what is love? This chapter discusses the relationship of feelings of love to acts of love and the relationship of romantic passion to covenantal commitment.

Chapter 4 ["The Mission of Marriage"] addresses the question of what marriage is for: It is a way for two spiritual friends to help each other on their journey to become the persons God designed them to be. Here we will see that a new and deeper kind of happiness is found on the far side of holiness.

Chapter 5 ["Loving the Stranger"] lays out three basic skill sets though which we can help each other on that journey.

Chapter 6 ["Embracing the Other"] [written by Kathy] discusses the Christian teaching that marriage is a place where the two sexes accept each other as differently gendered and learn and grow through it.

Chapter 7 ["Singleness and Marriage"] helps single people use the material in this book to live the single life well and to think wisely about seeking marriage themselves.

Finally, chapter 8 ["Sex and Marriage"] takes on the subject of sex, why the Bible confines it to marriage, and how, if we embrace the Biblical view, it will play out in both the single life and in marriage.

* * *

They explain that their book will assume the Bible's teaching that marriage is designed to be a monogamous heterosexual union:

In this book we examine the Christian understanding of marriage. It is based, as we have said, on a straightforward reading of Biblical texts. This means we are defining marriage as a life long, monogamous relationship between a man and a woman. According to the Bible, God devised marriage

to reflect his saving love for us in Christ,

to refine our character,

to create stable human community for the birth and nurture of children, and

to accomplish all this by bringing the complementary sexes into an enduring whole-life union.It needs to be said, therefore, that this Christian vision for marriage is not something that can be realized by two people of the same sex. That is the unanimous view of the Biblical authors, and therefore that is the view that we assume throughout the rest of this book, even though we don't directly address the subject of homosexuality.

With an eye—as usual—toward those who might be skeptical of the biblical worldview, the Kellers encourage readers to consider this countercultural approach:

The Bible's teaching on marriage does not merely reflect the perspective of any one culture or time. The teachings of Scripture challenge our contemporary Western culture's narrative of individual freedom as the only way to be happy. At the same time, it critiques how traditional cultures perceive the unmarried adult to radically critiques the institution of polygamy, even though it was be less than a fully formed human being. The book of Genesis the accepted cultural practice of the time, by vividly depicting the misery and havoc it plays in family relationships, and the pain it caused, especially for women. The New Testament writers, in a way that startled the pagan world, lifted up long-term singleness as a legitimate way to live. In other words, the Biblical authors' teaching constantly challenged their own cultures' beliefs—they were not simply a product of ancient mores and practices.

We cannot, therefore, write off the Biblical view of marriage as one dimensionally regressive or culturally obsolete. On the contrary, it is bristling with both practical, realistic insights and breathtaking promises about marriage. And they come not only in well-stated propositions but also through brilliant stories and moving poetry. Unless you're able to look at marriage through the lens of scripture instead of through your own fears or romanticism, through your particular experience, or through your culture's narrow perspectives, you won't be able to make intelligent decisions about your own marital future.

The History of the Global Church in One Volume

[image error]Doug Sweeney (Trinity Evangelical Divinity School) on the new book, The Church from Age to Age: A History from Galilee to Global Christianity (Concordia Publishing House, 2011):

"The Church from Age to Age is a marvelous survey text. Replete with a lengthy, detailed timeline, fifteen different maps, lists of popes, eastern patriarchs, church councils and assemblies, peppered with primary source readings and, most importantly, founded on a meaty, spiritually edifying, and global historical narrative, it offers students of all kinds a wealth of information in a reader-friendly format. Though produced by confessional Lutherans from a Protestant point of view, it is accurate, reliable, and much broader in scope than most traditional Protestant histories. Its global frame of reference will be especially helpful to many. I strongly recommend this text for use in Christian colleges, seminaries, churches, and Protestant homes around the world. I will certainly be using it in my own teaching ministry."

You can read online for free Paul Maier's foreword, the detailed table of contents, and an excerpt from the chapter on Christianity after WW2.

What Is God Sovereign Over?

The Bible verses below are far from exhaustive, and each should be interpreted according to its genre and context. But I am convinced that these verses—rightly interpreted—definitively establish God's absolute sovereignty over all things. And since compatiblism is true, none of this contradicts the equally biblical teaching that Satan is "the god of this world" (2 Cor. 4:4) and that human choices are genuine and significant.

God Is Sovereign Over . . .

Seemingly random things:

The lot is cast into the lap,

but its every decision is from the LORD.

(Proverbs 16:33)

The heart of the most powerful person in the land:

The king's heart is a stream of water in the hand of the LORD;

he turns it wherever he will.

(Proverbs 21:1)

Our daily lives and plans:

A man's steps are from the LORD;

how then can man understand his way?

(Proverbs 20:24)

Many are the plans in the mind of a man,

but it is the purpose of the LORD that will stand.

(Proverbs 19:21)

Come now, you who say, "Today or tomorrow we will go into such and such a town and spend a year there and trade and make a profit"—yet you do not know what tomorrow will bring. . . . Instead you ought to say, "If the Lord wills, we will live and do this or that."

(James 4:13-15)

Salvation:

"I will have mercy on whom I have mercy, and I will have compassion on whom I have compassion." So then it depends not on human will or exertion, but on God, who has mercy.

(Romans 9:15-16)

As many as were appointed to eternal life believed.

(Acts 13:48)

For those whom he foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son, in order that he might be the firstborn among many brothers. And those whom he predestined he also called, and those whom he called he also justified, and those whom he justified he also glorified.

(Romans 8:29-30)

Life and death:

See now that I, even I, am he,

and there is no god beside me;

I kill and I make alive;

I wound and I heal;

and there is none that can deliver out of my hand.

(Deuteronomy 32:39)

The LORD kills and brings to life;

he brings down to Sheol and raises up.

(1 Samuel 12:6)

Disabilities:

Then the LORD said to [Moses], "Who has made man's mouth? Who makes him mute, or deaf, or seeing, or blind? Is it not I, the LORD?"

(Exodus 4:11)

The death of God's Son:

Jesus, [who was] delivered up according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God, you crucified and killed by the hands of lawless men.

(Acts 2:23)

For truly in this city there were gathered together against your holy servant Jesus, whom you anointed, both Herod and Pontius Pilate, along with the Gentiles and the peoples of Israel, to do whatever your hand and your plan had predestined to take place.

(Acts 4:27-28)

Yet it was the will of the LORD to crush him;

he has put him to grief. . . .

(Isaiah 53:10)

Evil things:

Is a trumpet blown in a city,

and the people are not afraid?

Does disaster come to a city,

unless the LORD has done it?

(Amos 3:6)

I form light and create darkness,

I make well-being and create calamity,

I am the LORD, who does all these things.

(Isaiah 45:7)

"The LORD gave, and the LORD has taken away; blessed be the name of the LORD." In all this Job did not sin or charge God with wrong. . . . "Shall we receive good from God, and shall we not receive evil?" In all this Job did not sin with his lips.

(Job 1:21-22; 2:10)

[God] sent a man ahead of them, Joseph, who was sold as a slave. . . . As for you, you meant evil against me, but God meant it for good, to bring it about that many people should be kept alive, as they are today.

(Psalm 105:17; Genesis 50:21)

All things:

[God] works all things according to the counsel of his will.

(Ephesians 1:11)

Our God is in the heavens;

he does all that he pleases.

(Psalm 115:3)

I know that you can do all things,

and that no purpose of yours can be thwarted.

(Job 42:2)

All the inhabitants of the earth are accounted as nothing,

and he does according to his will among the host of heaven

and among the inhabitants of the earth;

and none can stay his hand

or say to him, "What have you done?"

(Daniel 4:35)

Two Ways of Doing Life: Psalm 23 versus Antipsalm 23

From Jesus' point of view, there are two fundamentally different ways of doing life.

One way, you're connected to a God who's involved in your life. Psalm 23 is all about this: "The LORD is my shepherd . . . and his goodness and mercy surely follow me all the days of my life."

The other way, you're pretty much on your own and disconnected. Let's call this the antipsalm 23: "I'm on my own . . . and disappointment follows me all the days of my life."

We'll look first at the antipsalm way of doing life.

Antipsalm 23

I'm on my own.

No one looks out for me or protects me.

I experience a continual sense of need. Nothing's quite right.

I'm always restless. I'm easily frustrated and often disappointed.

It's a jungle—I feel overwhelmed. It's a desert—I'm thirsty.

My soul feels broken, twisted, and stuck. I can't fix myself.

I stumble down some dark paths.

Still, I insist: I want to do what I want, when I want, how I want.

But life's confusing. Why don't things ever really work out?

I'm haunted by emptiness and futility—shadows of death.

I fear the big hurt and final loss.

Death is waiting for me at the end of every road,

but I'd rather not think about that.

I spend my life protecting myself. Bad things can happen.

I find no lasting comfort.

I'm alone . . . facing everything that could hurt me.

Are my friends really friends?

Other people use me for their own ends.

I can't really trust anyone. No one has my back.

No one is really for me—except me.

And I'm so much all about ME, sometimes it's sickening.

I belong to no one except myself.

My cup is never quite full enough. I'm left empty.

Disappointment follows me all the days of my life.

Will I just be obliterated into nothingness?

Will I be alone forever, homeless, free-falling into void?

Sartre said, "Hell is other people."

I have to add, "Hell is also myself."

It's a living death,

and then I die.

The antipsalm tells what life feels like and looks like whenever God vanishes from sight. . . . The antipsalm captures the drivenness and pointlessness of life-purposes that are petty and self-defeating. It expresses the fears and silent despair that cannot find a voice because there's no one to really talk to. . . . Something bad gets last say, when whatever you live for is not God.

And when you're caught up in the antipsalm, it doesn't help when you're labeled a "disorder," a "syndrome," or a "case." The problem is much more serious. The disorder is "my life." The syndrome is "I'm on my own." The case is "Who am I and what am I living for?," when too clearly I am the center of my story.

But the antipsalm doesn't need to tell the final story. It only becomes your reality when you construct your reality from a lie. In reality, someone else is the center of the story. Nobody can make Jesus go away. The I AM was, is and will be, whether or not people acknowledge.

When you awaken, when you see who Jesus actually is, everything changes. You see the person whose care and ability you can trust. You experience his care. You see the person whose glory you are meant to worship. You love him who loves you. The real Psalm 23 captures what life feels like and looks like when Jesus Christ puts his hand on your shoulder.

Psalm 23

The LORD is my shepherd, I shall not be in want.

He makes me lie down in green pastures.

He leads me beside quiet waters.

He restores my soul.

He leads me in paths of righteousness for his name's sake.

Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death,

I will fear no evil, for you are with me.

Your rod and your staff, they comfort me.

You prepare a table before me in the presence of my enemies.

You anoint my head with oil.

My cup overflows.

Surely goodness and mercy will follow me all the days of my life,

and I will dwell in the house of the Lord forever.

Can you taste the difference?

You might want to read both antipsalm and psalm again, slowly. Maybe even read out loud. The Psalm is sweet, not bitter. It's full, not empty. You aren't trying to grab the wind with your bare hands. Someone else takes you in his hands. You are not alone.

Jesus Christ actually plays two roles in this most tender psalm.

First, he walked this himself. He is a man who looked to the Lord. He said these very words, and means what he says. He entered our predicament. He walked the valley of the shadow of death. He faced every evil. He felt the threat of the antipsalm, of our soul's need to be restored. He looked to his Father's care when he was cast down—for us—into the darkest shadow of death. And God's goodness and mercy followed him and carried him. Life won.

Second, Jesus is also this Lord to whom we look. He is the living shepherd to whom we call. He restores your soul. He leads you in paths of righteousness. Why? Because of who he is: "for his name's sake." You, too, can walk Psalm 23. You can say these words and mean what you say. God's goodness and mercy is true, and all he promises will come true. The King is at home in his universe. Jesus puts it this way, "It is your Father's good pleasure to give you the kingdom" (Luke 12:32). He delights to walk with you.

How I Wish the Homosexuality Debate Would Go

Outstanding post by Trevin Wax.

October 17, 2011

The Worldview of C. S. Lewis and The Voyage of the Dawn Treader

Peter Kreeft lectured for the Richmond Study Center at St. Giles Presbyterian Church (January 14, 2011) on the worldview of C.S. Lewis, comparing the movie and the book for The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. You can listen to the audio or watch it below.

Metamorphosis: The Miracle of Dying to Be Transformed

The trailer for an informative and attractive new Intelligent Design documentary Metamorphosis: The Beauty and Design of Butterflies:

See also the other films in this collection.

What Is Hebrew Poetry? Illustrated in Psalm 19

[image error]

David Reimer's "Introduction to the Poetic and Wisdom Literature" in the ESV Study Bible reminds us that there is always more to see in what we see. Here is a section on some aspects of poetry illustrated with just Psalm 19:

Poetry is commonly recognized by lines exhibiting rhythm and rhyme, readily exemplified by nursery rhymes: even the simple "One, two, buckle my shoe" demonstrates both aspects. This brief snippet exhibits rhythm (óne, twó, [pause] búckle my shóe), terseness, assonance (the resemblance of the vowel sounds in "one" and "buckle", and "two" and "shoe"), and rhyme—and this sort of wordcraft can also be seen in the work of the ancient Hebrew poets. Apart from rhyme, conventions such as terse expression, freedom in word order, and an absence of typical prose particles also distinguish biblical Hebrew poetry from prose.

One prominent feature of biblical poetry not found in English poems is that of the "seconding sequence"; that is, a line of Hebrew poetry generally has two parts. The poet's art allows the relationship between those parts to be crafted in manifold ways. Here is Psalm 19:1:

The heavens declare the glory of God,

and the sky above proclaims his handiwork.

Hashamayim mesapperim kebod 'El

Uma'aseh yadaw maggid haraqia'

In the opening of Psalm 19, the heavens in the first part finds an echo in the sky above in the second part; likewise, declare parallels proclaims, and the glory of God partners his handiwork. With nearly one-to-one correspondence, it is obvious why such poetic parallelism has often been called "synonymous"—one of three such categories, the others being "antithetical," where the second part provides the opposite to the first part (e.g., "A wise son makes a glad father, but a foolish son is a sorrow to his mother," Prov. 10:1), and "synthetic," where the two parts of the line do not display either of these kinds of semantic relationship.

Assigning a line of poetry to one of these simple categories represents only a first small step in discerning the poet's art. This "parallel" structure offers the poet a surprisingly rich framework for artistic development: the poet is not simply saying the same thing twice in slightly different terms. The parallel line structure provided Hebrew poets with a means of exploiting similarity and difference on the levels of sound, syntax, and semantics to achieve an artistically compelling expression of their vision. Unfortunately, of these three elements, the first two (sound and syntax) usually do not survive translation. In the Hebrew of Psalm 19:1, both parts of the line are roughly 11/12 syllables, with three stresses in the first part, and four in the second. Syntactically, they form a very neat "envelope" structure, of the a-b-c/c–b–a- pattern: subject-verb-object/object-verb-subject. Such symmetry already begins to express the totality of the poet's vision.

However, semantics—the meanings of words—are observable in translation. Of course, complete overlap of the meanings of words cannot be sustained across languages, so there is still an advantage to those who can enjoy the poetry in its original setting. While the simple matches across the parts of this first line of Psalm 19 were noted above, there is yet more to be observed.

The a:a- pair ("heavens" and "sky above") are not precise synonyms. "Heavens" is the more generic term, and occurs well over 400 times in the OT; by contrast, "sky above" (Hb. raqia') occurs only 17 times, and nine of those are in the creation account of Genesis 1. Even in this apparently simple development, which exploits the seconding pattern of the parallel line structure, the poet moves from the more generic assertion in the first part to the more specific in the second to display God's glory in his creative acts ("handiwork"). (Confirmation of this allusion to creation comes in Ps. 19:4, which partners "earth" and "world" so that Ps. 19:1 and Ps. 19:4 together allude to the "heavens and earth" of Gen. 1:1.)

Something similar could be noted of the verbs: "declare" (Hb. mesapperim) refers to the simple act of rehearsal or recounting; "proclaim" (Hb. maggid) on the other hand brings the nuance of announcement, of revelation, of news. This invitation to savor the wonder of creation's wordless confession of the glories of God (Ps. 19:1-4a), then, forms a profound counterpart to the famous reflection on the verbal expressions of the will of the Lord found in the law (Ps. 19:7-11).

Many lines of Hebrew verse do not offer this kind of parallel correspondence, however. Sometimes simple grammatical dependency binds the parts together (e.g., Ps. 19:3), or the first part asks a question that the second part answers (Ps. 19:12). Sometimes there is a narrative development (Ps. 19:5, 13), sometimes an escalation or intensification of terms (Ps. 19:1, 10).

These few examples are drawn from a single psalm with fairly regular features; surveying the entire poetic corpus would add a myriad of possibilities. Consistently, however, the art and craft of the Bible's poems offers an invitation to read slowly, to have one's vision broadened, one's perception deepened—or, as it was put above, to see literary reflection in the service of worship and godly living.

What Is the Mission of the Church?

Scott Anderson interviews Kevin DeYoung and Greg Gilbert on their new book What Is the Mission of the Church? Making Sense of Social Justice, Shalom, and the Great Commission.

There Are No Ordinary People; You Have Never Talked to a Mere Mortal

C.S. Lewis:

It may be possible for each to think too much of his own potential glory hereafter; it is hardly possible for him to think too often or too deeply about that of his neighbor.

It may be possible for each to think too much of his own potential glory hereafter; it is hardly possible for him to think too often or too deeply about that of his neighbor.

The load, or weight, or burden of my neighbor's glory should be laid daily on my back, a load so heavy that only humility can carry it, and the backs of the proud will be broken.

It is a serious thing to live in a society of possible gods and goddesses, to remember that the dullest and most uninteresting person you talk to may one day be a creature which, if you saw it now, you would be strongly tempted to worship, or else a horror and a corruption such as you now meet, if at all, only in a nightmare.

All day long we are, in some degree, helping each other to one or other of these destinations.

It is in the light of these overwhelming possibilities, it is with the awe and circumspection proper to them, that we should conduct all our dealings with one another, all friendships, all loves, all play, all politics.

There are no ordinary people.

You have never talked to a mere mortal.

Nations, cultures, arts, civilization—these are mortal, and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat.

But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub, and exploit—immortal horrors or everlasting splendors.

This does not mean that we are to be perpetually solemn.

We must play.

But our merriment must be of that kind (and it is, in fact, the merriest kind) which exists between people who have, from the outset, taken each other seriously—no flippancy, no superiority, no presumption.

And our charity must be real and costly love, with deep feeling for the sins in spite of which we love the sinner—no mere tolerance or indulgence which parodies love as flippancy parodies merriment.

Next to the Blessed Sacrament itself, your neighbor is the holiest object presented to your senses.

—The Weight of Glory (HarperOne, 2001), pp. 45-46.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers