Justin Taylor's Blog, page 131

November 12, 2013

A Reading Plan for Paradise Lost

Last week I posted Michael Haykin’s suggested reading guide to Augustine’s The City of God.

Here is Leland Ryken’s reading guide to John Milton’s Paradise Lost:

The best way by far to read Milton’s masterpiece is to read it as a story, starting at the beginning, settling down for the archetypal “long read,” and moving forward as fast or slowly as one’s time and attention span allow. As C. S. Lewis once said of long poems, a reader needs to be prepared for flats and shallows as well as mountaintops.

For people who find the prospect of reading the entire poem daunting, my advice is to read more topically and meditatively, foregoing the narrative as a whole.

Here are the key passages that can comprise such a reading:

Book 1:

Satan and the demons in hell, a spectacle of evil and its punishment.

Book 3, lines 1-415

God and the Son in heaven, determining what to do about the impending fall of Adam and Eve.

Book 4

The best of the best! Milton’s portrayal of life in paradise, offered as a picture of how God intends human life to be lived.

Book 9

The temptation and fall of Adam and Eve.

Book 12, lines 552 to the end:

Adam’s response to the vision of future history, followed by Milton’s magnificent description of Adam and Eve’s departure from the garden; everything is a balance between sadness and consolation here at the end.

—Leland Ryken, “Paradise Lost by John Milton (1608-1674),” The Devoted Life: An Invitation to the Puritan Classics (IVP, 2004), 150-151.

See also Ryken’s entry on Paradise Lost in his Christian Guides to the Classics.

Why You Should Become Familiar with Samuel Rutherford’s Letters

Charles Spurgeon once wrote: “When we are dead and gone let the world know that Spurgeon held Rutherford’s Letters to be the nearest thing to inspiration which can be found in all the writings of mere men.”

Charles Spurgeon once wrote: “When we are dead and gone let the world know that Spurgeon held Rutherford’s Letters to be the nearest thing to inspiration which can be found in all the writings of mere men.”

Sinclair Ferguson says, “Surprising though it may seem in a world of large books, of all those owned by our family this may be the one we have most often lent or quoted to friends.”

For a contemporary gift edition, I’d recommend this.

And for an intellectual biography of Rutherford, this is the book to get.

The Greatest Sonnet in the English Language

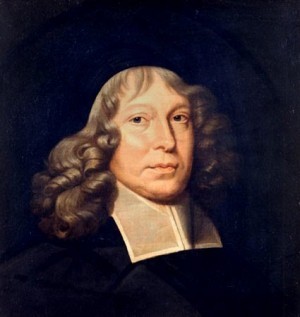

Leland Ryken writes that John Milton’s “When I Consider How My Light Is Spent” is to him “the greatest sonnet in the English language.” During the middle phase of Milton’s life (1640-1660) he focused on supporting the Puritan cause and largely set aside his poetic vocation. By 1654, at the age of 55, he had gone completely blind, and probably composed this sonnet around this time.

Leland Ryken writes that John Milton’s “When I Consider How My Light Is Spent” is to him “the greatest sonnet in the English language.” During the middle phase of Milton’s life (1640-1660) he focused on supporting the Puritan cause and largely set aside his poetic vocation. By 1654, at the age of 55, he had gone completely blind, and probably composed this sonnet around this time.

When I Consider How My Light Is Spent

by John Milton

When I consider how my light is spent,

Ere half my days in this dark world and wide,

And that one talent which is death to hide

Lodged with me useless, though my soul more bent

To serve therewith my Maker, and present

My true account, lest He returning chide;

“Doth God exact day-labor, light denied?”

I fondly ask. But Patience, to prevent

That murmur, soon replies, “God doth not need

Either man’s work or His own gifts. Who best

Bear His mild yoke, they serve Him best. His state

Is kingly: thousands at His bidding speed,

And post o’er land and ocean without rest;

They also serve who only stand and wait.”

November 11, 2013

Mark Noll and John Piper on Jesus Christ and the Life of the Mind

A conversation with Mark Noll (author of Jesus Christ and the Life of the Mind) and John Piper (author of Think: The Life of the Mind and the Love of God), moderated by Ryan Griffith, Assistant Professor of Christian Worldview and Director of Undergraduate Studies at Bethlehem College and Seminary. They discuss the best way to approach education and the life of the mind. Following the conversation you can watch lectures each of them gave on this topic.

Kathy Keller: Why Sarah Young’s “Jesus Calling” Is Unhelpful and to Be Avoided

Kathy Keller of Redeemer Presbyterian Church:

If Sarah Young, the author of the words attributed to Jesus, had only used “He” instead of “I” in her book, about half of my objection to it would be gone. However, in publishing these as messages she received from “listening to God,” she has left us in a quandary.

Although in the Introduction she acknowledges that she “knew that these writings were not inspired as Scripture is” and a few pages later she says “The Bible is, of course, the only inerrant [without error] Word of God,” then why are the messages she received from Jesus put in the first person? If it is not truly Jesus speaking, she could have said “Jesus wants you to come to him and have rest in him.” But when she says “Keep your ‘antennae’ out to pick up even the faintest glimmer of My Presence,” and those words are attributed directly to Jesus (and they don’t sound like anything else he has ever said), then they have to be received on the same level as Scripture, or she has put her own thoughts into the mouth Jesus.

Read the whole thing here.

See also Michael Horton’s review.

Christianity Today recently profiled Sarah Young and included a roundup of some of the criticism.

C.S. Lewis on the Need to Translate Theology for Lay Poeple

William Pittenger (1905-1997) was a liberal Anglican theologian known for his defense of process theology and offered an early Christian defense of homosexual relationships among Christians.

In October of 1958 he published a piece entitled “Apologist Versus Apologist: A Critique of C. S. Lewis as ‘Defender of the Faith,’” The Christian Century LXXV (October, 1958): 1104-1107.

The following month Lewis penned a response in the November 1958 issue. It is a delightful response in many ways as Lewis acknowledges error, chides misinterpretation, muses about the sledgehammer of the Sermon on the Mount, and closes with a lament about the lack of theological translation in our day.

Here are the closing paragraphs:

He judges my books in vacuo, with no consideration of the audience to whom they were addressed or the prevalent errors they were trying to combat. The Naturalist becomes a straw man because he is not found among ‘first-rate scientists’ and readers of Einstein. But I was writing ad populum, not ad clerum. This is relevant to my manner as well as my matter.

It is true, I do not understand why it is vulgar or offensive, in speaking of the Holy Trinity, to illustrate from plane and solid geometry the conception that what is self-contradictory on one level may be consistent on another. I could have understood the Doctor’s being shocked if I had compared God to an unjust judge or Christ to a thief in the night; but mathematical objects seem to me as free from sordid associations as any the mind can entertain.

But let all that pass. Suppose the image is vulgar. If it gets across to the unbeliever what the unbeliever desperately needs to know, the vulgarity must be endured. Indeed, the image’s very vulgarity may be an advantage; for there is much sense in the reasons advanced by Aquinas (following Pseudo-Dionysius) for preferring to present truths sub figuris vilium coporum. . . .

When I began, Christianity came before the great mass of my unbelieving fellow-countrymen either in the highly emotional form offered by revivalists or in the unintelligible language of highly cultured clergymen. Most men were reached by neither. My task was therefore simply that of a translator—one turning Christian doctrine, or what he believed to be such, into the vernacular, into language that unscholarly people would attend to and could understand. For this purpose a style more guarded, more nuancé, finelier shaded, more rich in fruitful ambiguities — in fact, a style more like Dr Pittenger’s own—would have been worse than useless. It would not only have failed to enlighten the common reader’s understanding; it would have aroused his suspicion. He would have thought, poor soul, that I was facing both ways, sitting on the fence, offering at one moment what I withdrew the next, and generally trying to trick him. I may have made theological errors. My manner may have been defective. Others may do better hereafter. I am ready, if I am young enough, to learn. Dr Pittenger would be a more helpful critic if he advised a cure as well as asserting many diseases. How does he himself do such work? What methods, and with what success, does he employ when he is trying to convert the great mass of storekeepers, lawyers, realtors, morticians, policemen and artisans who surround him in his own city?

One thing at least is sure. If the real theologians had tackled this laborious work of translation about a hundred years ago, when they began to lose touch with the people (for whom Christ died), there would have been no place for me.

HT: John Piper

Our Family’s Fourth Adoption

Our family is currently in the process for our fourth adoption.

Our family is currently in the process for our fourth adoption.

If anyone feels led to help us financially in this endeavor (and please feel no pressure to do so!), we have set up a page that facilitates this.

God has graciously used the gift of adoption to build our family and to remind us of the beauty of our spiritual adoption in him. We are eager to receive more blessing by welcoming another baby into our home.

Many thanks for your kind consideration.

And if you are wondering why adoption is such a big deal for Christians, it’s because of the foundation of our faith.

After all, the church is an organic collection of individual orphans turned adopted children, brothers and sisters in Christ.

Jesus promised his disciples that he would not leave them as orphans (John 14:8).

The reason Jesus was born, according to Galatians 4:4-8, is so that Jesus could redeem us (v. 4); and the reason he came to redeem us is so that God could adopt us as sons (v. 5).

The result is that the Father sends the Spirit of his Son into our hearts so that we can cry “Abba, Father!” (v. 6).

Now that we are adopted sons instead of slaves in bondage, we have an eternal inheritance through God. It’s because of teaching like this that J. I. Packer writes:

Our understanding of Christianity cannot be better than our grasp of adoption. . . . If you want to judge how well a person understands Christianity, find out how much he makes of the thought of being God’s child, and having God as his Father. If this is not the thought that prompts and controls his worship and prayers and whole outlook on life, it means that he does not understand Christianity very well at all.

Because God is a Father to the fatherless and a protector of widows (Ps. 68:5), he commands his adopted children—the bride of Christ—”to visit orphans and widows in their affliction” (James 1:27). Adopting, assisting with adoption, and foster care are some (though not the only) means of fulfilling this biblical vision and command.

Fred Sanders Responds to Peter Leithart on “The End of Protestantism”

Fred Sanders responds to Peter Leithart’s blog post at First Things on “The End of Protestantism“:

Leithart calls us away from that kind of small-minded, knee-jerk, unimaginative, amnesiac man of ressentiment, and conjures instead something free and fully realized. He calls it Reformational Catholicism, and builds up its portrait in bright, not to say self-congratulatory, colors, in contrast to the dark tones he has just used.

To put it this way is to point out that the essay labors under an inconsistency between its message and its method. You don’t beat the man of ressentiment by resenting him harder. And this “End of Protestantism” essay has a squint, a stoop, a cramp, a kink in the hose. It deplores more than it deploys. The spring in its engine is the decision to turn the word “Protestant” into a term of abuse, and use it as a label to catch all the mockery directed at the know-nothings depicted above. I’m not sure who that’s supposed to help. It seems likely to quench the smoking flax of any actual Protestant interest in the great tradition.

Further:

What bothers me about “The End of Protestantism” is that it gives people like this [= the students at an evangelical institution like Biola who discover the great tradition through their coursework] the message that the trailhead to the great heritage cannot be picked up in their own church. The trailhead must be in some other church or denomination. Letihart’s unfortunate language effaces all signs of the trailhead, covers the tracks that we could follow back, demands a leap. The face of Luther glowers ambiguously from the top of the page, but we are assured that there are ”unplumbed depths in Scripture, never dreamt of by Luther and Calvin.” I expect this kind of dismissiveness from someone who hasn’t spent any time reading the exegesis of Luther and Calvin. But I always assume Leithart’s read everything, so I boggle at his false dichotomy between the Reformers and the ancient church.

You can read the whole thing here, as he analyzes what he takes to be a “misleading,” “misconceived,” and “convoluted” case.

November 9, 2013

How John Owen Might Have Responded to the Modern Charismatic Movement

In an essay on “John Owen on Spiritual Gifts” in A Quest for Godliness, J. I. Packer points that spiritual gifts were not much debated in Puritan theology and that Owen’s Discourse on Spiritual Gifts (published posthumously) is the only full-scale treatment of the subject by a major writer. Some of the questions we are asking today were not even raised at this time. For example, Packer writes, “Seventeenth-century England did not, to my knowledge, produce anyone who claimed the gift of tongues. . . .”

So how would the great John Owen have interacted with our contemporary debates? Packer writes: “it may be supposed (though this, in the the nature of the case, can only be a guess) that were Owen confronted with modern Pentecostal phenomena he would judge each case a posteriori, on its own merit, according to these four principles:”

1. Since the presumption against any such renewal is strong, and liability to ‘enthusiasm’ is part of the infirmity of every regenerate man, any extra-rational manifestation like glossolalia needs to be watched and tested most narrowly, over a considerable period of time, before one can, even provisionally, venture to ascribe it to God.

2. Since the use of a person’s gifts is intended by God to further the work of grace in his own soul (we shall see Owen arguing this later), the possibility that (for instance) a man’s glossolalia is from God can only be entertained at all as long as it is accompanied by a discernible ripening of the fruit of the Spirit in his life.

3. To be more interested in extraordinary gifts of lesser worth than in ordinary ones of greater value; to be more absorbed in seeking one’s own spiritual enrichment than in seeking the edifying of the church; and to have one’s attention centred on the Holy Spirit, whereas the Spirit himself is concerned to centre our attention on Jesus Christ—these traits are sure signs of ‘enthusiasm’ wherever they are found, even in those whom seem most saintly.

4. Since one can never conclusively prove that any charismatic manifestation is identical with what is claimed as its New Testament counterpart, one can never in any particular case have more than a tentative and provisional opinion, open to constant reconsideration as time and life go on. Owen was deeply concerned to bring out the supernaturalness of the Christian life, and to do justice to the Spirit’s work in it, but whether he could have felt close sympathy with any form of modern Pentecostalism is a question about which opinions might differ.

November 7, 2013

A Message on the Cross of Jesus Christ from Billy Graham and Lecrae

This is very well done. Pass it along:

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers