Justin Taylor's Blog, page 129

December 2, 2013

Resources for Christians Dealing with Same-Sex Attraction

From the new ministry and website, Living Out:

November 29, 2013

Does God Listen to Rap?

Recently a panel answered a question on reformed rap. Brent Hobbs has offered a transcript of the answers offered, along with a nice response to each of the arguments. (See also the responses from Owen Strachan and Mike Cosper.)

For those wanting to explore these issues further—and in my opinion, in a more biblically faithful way than the panelists offered—should consider picking up Curt Allen’s new book, Does God Listen to Rap? Christians and the World’s Most Controversial Music (Cruciform, 2013).

You can read the first chapter here.

And here’s a little video introduction for why you should consider this book:

November 28, 2013

G.K. Chesteron on Thanksgiving

“I would maintain that thanks are the highest form of thought, and that gratitude is happiness doubled by wonder.”—G. K. Chesterton

“The aim of life is appreciation; there is no sense in not appreciating things; and there is no sense in having more of them if you have less appreciation of them.”—G. K. Chesterton

“When it comes to life the critical thing is whether you take things for granted or take them with gratitude.”—G. K. Chesterton

“You say grace before meals. All right. But I say grace before the concert and the opera, and grace before the play and pantomime, and grace before I open a book, and grace before sketching, painting, swimming, fencing, boxing, walking, playing, dancing and grace before I dip the pen in the ink.”—G. K. Chesterton

“When we were children we were grateful to those who filled our stockings at Christmas time. Why are we not grateful to God for filling our stockings with legs?”—G. K. Chesterton

November 27, 2013

What Did the Pilgrims Really Eat for the First Thanksgiving Meal?

From John Turner’s summary in a review of Robert Tracy McKenzie’s The First Thanksgiving: What the Real Story Tells Us About Loving God and Learning from History (IVP, 2013):

In late September or early October, the Pilgrims celebrated their recently gathered harvest. They did so without pumpkin pie (no ovens), cranberry sauce (no sugar), and sweet potatoes (not native to North America). One of the settlers, Edward Winslow, recorded that they ate some kind of “fowl”—more likely to be goose or duck than turkey. Geese were much easier to shoot. The meal may also have included fish, shellfish, and perhaps eel, and the settlers would also have used vegetables such as turnips and carrots. Nor did they sit across from their native counterparts at a long table. Instead, McKenzie writes, “We should picture an outdoor feast in which almost everyone was sitting on the ground and eating with their hands.”

About 90 Wampanoag men and their chief Massasoit were present, but we don’t know whether they came with an invitation. A few years later, a delegation politely informed Massasoit that the Pilgrims “could no longer give them such entertainment as [they] had done.” It was, in any event, a fragile peace. In 1623, the Pilgrims placed the severed head of a Massachusetts Indian on their fort as a warning to native enemies and friends alike.

For the Pilgrims, this was not a holy day of thanksgiving, a long and solemn day of prayer, preaching, and worship. Instead, the “first” thanksgiving was a harvest celebration, including military drills and “recreations” (probably races, shooting contests, and so forth). Later generations of Americans temporarily managed to turn Thanksgiving into a church-centered day of worship and thanks, which eventually faded into an increased focus both on large family meals and football games.

Here is McKenzie himself talking about it:

Plymouth Colony Governor Edward Winslow

Our knowledge of this event comes from a letter written a couple of months later (December 13, 1621) by pilgrim Edward Winslow (1595-1655).Nathaniel Philbrick—the author of Mayflower: A Story of Courage, Community and War and the younger readers’ version The Mayflower and the Pilgrims’ New World—summarizes:

He describes a harvest festival that occurred not at the end of November but in late September or early October. Interestingly, Winslow does not call it a thanksgiving. He does not mention any turkeys.

What the pilgrims did have were ducks and geese. Winslow tells us that once they had harvested their crops, Governor William Bradford ordered four men to go fowling so that we might rejoice together after a more special manner.

In just a few days, the hunters secured enough ducks and geese to last the entire settlement a week. But what began as an English affair soon became an overwhelmingly native celebration.

Earlier that spring, the Wampanoag leader Massasoit had offered to form an alliance with the pilgrims. That fall, Massasoit arrived in Plymouth with 90 of his people and five freshly killed deer. Instead of the prim and proper sit-down affair of legend, the first Thanksgiving was an outdoor festival. Even if all the pilgrims’ furniture was brought out into the sunshine, most of the celebrants stood, squatted or sat as they clustered around fires where the deer and birds turned on wooden spits. Also simmering were pottages, stews into which meat and vegetables were thrown.

Winslow makes no mention of it, but the first Thanksgiving coincided with what was, for the pilgrims, a new and startling phenomena, the turning of the green leaves of summer to the incandescent yellows, reds and purples of a New England autumn.

In Britain, the cloudy fall days and warm nights cause the autumn colors to be muted and lackluster. In New England, on the other hand, the profusion of sunny, fall days and cool, but not freezing, nights unleashes the colors latent within the trees’ leaves. It was a display that must have contributed to the enthusiasm with which Winslow wrote of the festivities that fall.

For me, this is an instance when the historical reality is much more interesting than the myth. Instead of a pious warm-up for a glum Thanksgiving dinner with the in-laws, the Plymouth Harvest Festival of 1621 was more like Woodstock, an outdoor celebration that just sort of happened.

Here is the relevant text from Winslow’s letter:

Our corn [i.e. wheat] did prove well, and God be praised, we had a good increase of Indian corn, and our barley indifferent good, but our peas not worth the gathering, for we feared they were too late sown. They came up very well, and blossomed, but the sun parched them in the blossom. Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after a special manner rejoice together after we had gathered the fruit of our labors. They four in one day killed as much fowl as, with a little help beside, served the company almost a week. At which time, amongst other recreations, we exercised our arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and among the rest their greatest king Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five deer, which they brought to the plantation and bestowed on our governor, and upon the captain and others. And although it be not always so plentiful as it was at this time with us, yet by the goodness of God, we are so far from want that we often wish you partakers of our plenty.

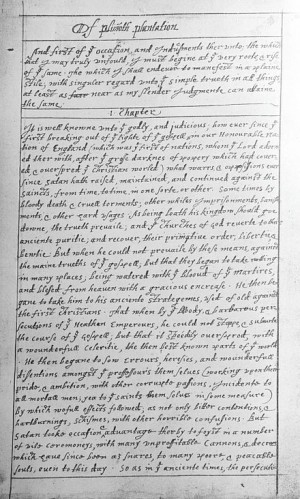

The first page of William Bradford's journal.

William Bradford (1590-1657) had become governor of the colony earlier that spring. He would later write a historical-narrative journal about the early days of Plymouth, recorded between 1630 and 1647. Here’s the relevant section where he looks back to 1621 (and mentions turkey!):

They began now to gather in the small harvest they had, and to fit up their houses and dwellings against winter, being all well recovered in health and strength and had all things in good plenty. For as some were thus employed in affairs abroad, others were exercising in fishing, about cod and bass and other fish, of which they took good store, of which every family had their portion. All the summer there was no want; and now began to come in store of fowl, as winter approached, of which this place did abound when they came first (but afterward decreased by degrees). And besides waterfowl there was great store of wild turkeys, of which they took many, besides venison, etc. Besides they had about a peck of meal a week to a person, or now since harvest, Indian corn to that proportion. Which made many afterwards write so largely of their plenty here to their friends in England, which were not feigned but true reports.

November 26, 2013

Malcolm Gladwell: A Mix of Moralism and Scientism?

John Gray, emeritus professor of European thought at the London School of Economics, writing in New Republic:

John Gray, emeritus professor of European thought at the London School of Economics, writing in New Republic:

What is striking about Gladwell’s work is not its distance from academic theorizing but the uncritical reverence that he displays toward the academic mind. He describes himself as a storyteller, but for him the story is never enough; it must be supported, and thereby legitimated, by prestigious academic studies and copious references. He is a high priest in the cult of “studies.” He feels on safe ground only when he is able to render his story into the supposed exactitude of quantitative social science. . . .

Perhaps this deference to academic authority reveals an underlying lack of intellectual self-confidence in the famously breezy writer. More likely it reflects his unthinking adherence to the idea that science can enable us somehow to transcend the dilemmas of morality and history. For it is not simply that Gladwell appeals to psychology and sociology as sources of intellectual authority. Along with many of those who promote them today, he believes that these disciplines can provide practical guidance—not just policy proposals, but wisdom for living. Psychology and sociology can turn the sayings and parables of less enlightened times into an expanding body of knowledge. Quantitative reason can take over from the fumbling human imagination.

Further:

Gladwell may seem to have devised a new variety of inspirational nonfiction, but it is one that has some clear precedents. He is finally in the self-help racket, and his books belong in the genre of which Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends & Influence People, from 1936, is the best-known example. There is a never-ending flow of manuals of optimism, offering untold wealth, sexual success, and enduring fame to those who read them and imbibe the lessons they contain. If Gladwell’s writings seem more serious-minded than most of those manuals, it is because his comforting tales of self-improvement and overcoming evil are given a thin gloss of scientific authority. It is this combination, together with the conceit of presenting counterintuitive truths, that makes his work so popular.

Uncharitably, some critics have suggested that this is a genre that risks becoming stale. But the mix of moralism and scientism is an ever-winning formula, as Gladwell’s career demonstrates. Speaking to a time that prides itself on optimism and secretly suspects that nothing works, his books are analgesics for those who seek temporary relief from abiding anxiety. There is more of reality and wisdom in a Chinese fortune cookie than can be found anywhere in Gladwell’s pages. But then, it is not reality or wisdom that his readers are looking for.

You can read the whole thing here.

For those who have read Gladwell’s work: What do you think? Fair or unfair?

Malcom Gladwell: A Mix of Moralism and Scientism?

John Gray, emeritus professor of European thought at the London School of Economics, writing in New Republic:

John Gray, emeritus professor of European thought at the London School of Economics, writing in New Republic:

What is striking about Gladwell’s work is not its distance from academic theorizing but the uncritical reverence that he displays toward the academic mind. He describes himself as a storyteller, but for him the story is never enough; it must be supported, and thereby legitimated, by prestigious academic studies and copious references. He is a high priest in the cult of “studies.” He feels on safe ground only when he is able to render his story into the supposed exactitude of quantitative social science. . . .

Perhaps this deference to academic authority reveals an underlying lack of intellectual self-confidence in the famously breezy writer. More likely it reflects his unthinking adherence to the idea that science can enable us somehow to transcend the dilemmas of morality and history. For it is not simply that Gladwell appeals to psychology and sociology as sources of intellectual authority. Along with many of those who promote them today, he believes that these disciplines can provide practical guidance—not just policy proposals, but wisdom for living. Psychology and sociology can turn the sayings and parables of less enlightened times into an expanding body of knowledge. Quantitative reason can take over from the fumbling human imagination.

Further:

Gladwell may seem to have devised a new variety of inspirational nonfiction, but it is one that has some clear precedents. He is finally in the self-help racket, and his books belong in the genre of which Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends & Influence People, from 1936, is the best-known example. There is a never-ending flow of manuals of optimism, offering untold wealth, sexual success, and enduring fame to those who read them and imbibe the lessons they contain. If Gladwell’s writings seem more serious-minded than most of those manuals, it is because his comforting tales of self-improvement and overcoming evil are given a thin gloss of scientific authority. It is this combination, together with the conceit of presenting counterintuitive truths, that makes his work so popular.

Uncharitably, some critics have suggested that this is a genre that risks becoming stale. But the mix of moralism and scientism is an ever-winning formula, as Gladwell’s career demonstrates. Speaking to a time that prides itself on optimism and secretly suspects that nothing works, his books are analgesics for those who seek temporary relief from abiding anxiety. There is more of reality and wisdom in a Chinese fortune cookie than can be found anywhere in Gladwell’s pages. But then, it is not reality or wisdom that his readers are looking for.

You can read the whole thing here.

For those who have read Gladwell’s work: What do you think? Fair or unfair?

November 25, 2013

20 Ways to Pray for the Seminaries

I recently heard Al Mohler, president of Southern Seminary, explain that he will often ask older supporters of the seminary whom they want pastoring their grandchildren some day. The answer, for good or for ill, is found in our seminaries. But I wonder how many of us ever stop to pray for them?

I’ve adapted the following from a piece written by John Piper. Perhaps it could serve as a prompt and a guide.

Goal: that seminaries would know the all-embracing goal of God’s glory.

Pray:

That the supreme, heartfelt and explicit goal of every faculty member might be to teach and live in such a way that his students come to admire the glory of God with white-hot intensity (1 Corinthians 10:31; Matthew 5:16).

Goal: that seminaries would cultivate a contrite and humble sense of human insufficiency (John 15:5; 2 Cor. 4:7; 2 Cor. 2:16).

Pray:

That, among the many ways this goal can be sought, the whole faculty will seek it by the means suggested in 1 Peter 4:11: Serve “in the strength which God supplies: in order that in everything God may be glorified through Jesus Christ.”

That the challenge of the ministry might be presented in such a way that the question rises authentically in students’ hearts: “Who is sufficient for these things?” (2 Corinthians 2:16).

That in every course the indispensable and precious enabling of the Holy Spirit will receive significant emphasis in comparison to other means of ministerial success (Galatians 3:5).

That teachers will cultivate the pastoral attitude expressed in 1 Corinthians 15:10 and Romans 15:18: “I worked harder than any of them, though it was not I, but the grace of God which is with me. . . . I will not venture to speak of anything except what Christ has wrought through me to win obedience from the Gentiles.”

That the poverty of spirit commended in Matthew 5:3 and the lowliness and meekness commended in Colossians 3:12 and Ephesians 4:2 and 1 Peter 5:5-6 will be manifested through the administration, faculty, and student body.

Goal: that seminaries would cultivate a great passion for Christ’s all-sufficiency; and that, for all our enthusiasm over contemporary trends in ministry, the overwhelming zeal of a pastor’s heart be for the changeless fundamentals of the faith (Phil. 3:7).

Pray:

That the faculty might impress upon students by precept and example the immense pastoral need to pray without ceasing and to despair of all success without persevering prayer in reliance on God’s free mercy (Matthew 7:7-11; Ephesians 6:18).

That the faculty will help the students feel what an unutterably precious thing it is to be treated mercifully by the holy God, even though we deserve to be punished in hell forever (Matthew 25:46; 18:23-35; Luke 7:42, 47).

That, because of our seminary faculties, hundreds of pastors, 50 years from now, will repeat the words of John Newton on their death beds: “My memory is nearly gone; but I remember two things: that I am a great sinner and that Jesus is a great Savior.”

That the faculty will inspire students to unqualified and exultant joy in the venerable verities of Scripture. “The precepts of the Lord are right, rejoicing the heart” (Psalm 19:8).

That every teacher will develop a pedagogical style based on James Denney’s maxim: “No man can give the impression that he himself is clever and that Christ is mighty to save.”

Goal: that the seminaries would cultivate strong allegiance to all of Scripture, and that what the apostles and prophets preached and taught in Scripture will be esteemed worthy of our careful and faithful exposition to God’s people (2 Tim 2:15).

Pray:

That in the treatment of Scripture there will be no truncated estimation of what is valuable for preaching and for life.

That students will develop a respect for and use of the awful warnings of Scripture as well as its precious promises; and that the command to “pursue holiness” (Hebrews 12:14) will not be blunted, but empowered, by the assurance of divine enablement. “Now the God of peace . . . equip you in every good thing to do His will, working in us that which is pleasing in His sight, through Jesus Christ, to whom be the glory forever and ever. Amen” (Hebrews 13:20).

That there might be a strong and evident conviction that the deep and constant study of Scripture is the best way to become wise in dealing with people’s problems. “All Scripture is inspired by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, for training in righteousness; so that the man of God may be adequate, equipped for every good work” (2 Timothy 3:16-17).

That the faculty may not represent the contemporary mood in critical studies which sees “minimal unity, wide-ranging diversity” in the Bible; but that they will pursue the unified “whole counsel of God” and help students see the way it all fits together. “For I did not shrink from declaring to you the whole purpose of God” (Acts 20:27).

That explicit biblical insights will permeate all class sessions, even when issues are treated with language and paradigms borrowed from contemporary sciences.

That God and his Word will not be taken for granted as the tacit “foundation” that doesn’t get talked about or admired.

That the faculty will mingle the “severe discipline” of textual analysis with an intense reverence for the truth and beauty of God’s Word.

That fresh discoveries will be made in the study of Scripture and shared with the church through articles and books.

That faculty, deans, and presidents will have wisdom and courage from God to make appointments which promote the fulfillment of these petitions.

And that boards and all those charged with leadership will be vigilant over the moral and doctrinal faithfulness of the faculty and exercise whatever discipline is necessary to preserve the biblical faithfulness of all that is taught and done.

—Adapted from John Piper, “Brothers, Pray for the Seminaries,” in Brothers, We Are Not Professionals: A Plea to Pastors for Radical Ministry, revised and expanded edition (B&H, 2013), 283-287.

November 22, 2013

Success in Ministry Is Dangerous, Accountability Doesn’t Work, and Other Thoughts on Falling from Grace

Recently I’ve spent some time with two friends who were in ministry but have fallen morally and so now find themselves out of a job that they loved, separated from their families and, in all honesty, struggling. I’ve showed what I’ve written to them and I wouldn’t say they were overjoyed at what I had to say but both agreed I could put this on here.

There’s a number of things that need to be said but, first of all, we need to recognise how fragile we are. These men were more gifted and more able than I ever will be. They are bright guys who were, in lots of our eyes, ‘successful’ in ministry. I’ve prayed with these men and shared in ministry with them. After meeting with them I came away upset and sad and slightly afraid; the reason being it could have been me. No one who has met with people who’ve just seen their lives implode and the speed at which sin can destroy a man can ever be proud. You can be angry with them and what they’ve done but you’ll be more aware of the fact that it could so easily have been me. ‘Therefore, let anyone who thinks that he stands take heed lest he fall’. 1 Corinthians 10:12

I’d encourage you to read the whole thing, as he offers several helpful thoughts in the following categories:

online life is a killer

success in ministry is a dangerous thing

accountability doesn’t work

marriage

the temptation to rehabilitate yourself

forgiveness is possible

C.S. Lewis (1898-1963): The Inconsolable Longing of a Romantic Rationalist

Today is the 50th anniversary of the death of C.S. Lewis.

These two talks by John Piper—the first delivered in 2010 and the second in 2013—are very thoughtful and helpful:

You can also read the manuscripts and listen to the audio, here and here.

November 21, 2013

Grieving a Loss with Hope in God

A strong message from Nancy Guthrie, a woman who knows how to grieve and knows how to persevere in hope:

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers