Andrew Welch's Blog, page 4

August 25, 2015

The second review

The second full review of The Value Crisis was published by the well-respected Alternatives Journal. I was totally blown away by this praise from such a prestigious journal. As with my first review, reprinting it here gives readers another forum where they can post comments and feedback.

Andrew Welch has a thing about numbers. He loves them. But as he gradually began to see the connection between growing, multiple global crises and the lack of awareness surrounding the day-to-day human behaviour that produces them, he began to wonder if humanity’s over-reliance on numbers was responsible. “We use debt to conjure up trillions of dollars from nothing; we voraciously run through our planet’s limited resources; and we recklessly contaminate our environment with waste, byproducts and dangerous substances.” The Value Crisis is the product of his attempts to reconcile this disconnect between behaviour and consequence.

The value crisis referenced in the title is the conflict between our human value system, which is ancient, and our number-based value system, which has developed over time, most of it very recently. Welch’s premise is that these two systems are incompatible and unbalanced and that fundamental human values are being displaced at great cost to us all – personally, as a species, and ultimately for every creature on the planet. This crisis of values is posited as the greatest challenge facing society and as the root cause of most of our environmental, economic and social ills.

Welch traces the origins of the value crisis from the beginnings of numeracy and the invention of math, through theories of decision making and indicators of well-being, to the history of money, the workings of the global economy and the nature of corporations. It’s quite a ride, and there are many fascinating side trips along the way.

For instance, he explains the concept of exponential growth (a phenomenon that is notoriously poorly understood), thoroughly and from several points of view. The examples are thoughtful and Welch relates them directly to the central premise of the book. And he performs this feat over and over again with such seemingly disparate concepts as the law of diminishing marginal utility, prospect theory, Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, the fractional reserve system and the pursuit of happiness.

The book is dizzyingly well researched, drawing on a wide range of contemporary scientific research, literature of all kinds and possibly more than one accounting textbook. It is also jam-packed with details, facts, quotes and equations. Fortunately, Welch seems to have an orderly turn of mind and his argument is well built and progresses logically. He makes good use of headings and text boxes to remind the reader where she is going and where he has been. Each chapter begins with an anecdote to ground the topic and ends with a comprehensive summary. He regularly returns to his central premise, showing how the new information he’s just introduced relates to the basic theme. Anything less would have made the book quite hard to follow and not nearly as useful. At the end he has gathered all the boxed text in a separate section and included page references.

There are many good reasons to read this book. For one thing, it will likely give you many excellent conversation starters. Did you know that capuchin monkeys make exactly the same poor financial decisions as humans? How about the fact that usury is a transaction in which money is acquired without goods or labour being exchanged (through the manipulation of numbers), that until recently it was considered unethical, and that it describes a great deal of today’s financial activity? Or that if corporations really were people, they would be classified as psychopaths?

Another reason is that this book is a great reference on the in and outs of economics, politics, finance and the human condition. But the best reason to read this book is for the basic background it can give the reader on how we got into our current environmental and social predicament – the historical and behavioural origins of a dysfunctional world.

Welch is remarkably free of blame for the groups of people operating within this dysfunctional system. He saves the blame for the system itself, explaining how what appears to be greed is simply an inevitable consequence, a side effect, of the numbers. Ultimately, numbers in general and money specifically, change the nature of our relationship to each other and to the world.

Along the journey, the author provides a number of possible solutions to the value crisis – some of them headsmackingly commonsensical and some of them wildly idealistic and unique. It is well worth reading this entertaining and accessible book to find out what those solutions are.

The Value Crisis: From Dollars to Democracy, Why Numbers are Ruining Our World by Andrew Welch, Caledon : Aanimad Press, 216 pages. Reviewed by Janet Kimantas

Published on August 25, 2015 14:17

March 13, 2015

The Village Against the World

Today, a reader shared a fascinating article on what they captioned "One solution to the Value Crisis??". The article was an edited extract from Dan Hancox's book "The Village Against the World". To put this post into context, you really have to read the article itself, printed in The Guardian in October, 2013.

In a nutshell (from his website), Dan's book is the story of the villagers of Marinaleda, Spain, "who expropriated the land owned by wealthy aristocrats and have, since the 1980s, made it the foundation of a cooperative way of life. Today, Marinaleda is a place where the farms and the processing plants are collectively owned and provide work for everyone who wants it. A mortgage is €15 per month, sport is played in a stadium emblazoned with a huge mural of Che Guevara, and there are monthly 'Red Sundays' when everyone works together to clean up the neighbourhood. Leading this revolution is the village mayor, Juan Manuel Sánchez Gordillo, who in 2012 became a household name in Spain after heading raids on local supermarkets to feed the Andalusian unemployed."

In a nutshell (from his website), Dan's book is the story of the villagers of Marinaleda, Spain, "who expropriated the land owned by wealthy aristocrats and have, since the 1980s, made it the foundation of a cooperative way of life. Today, Marinaleda is a place where the farms and the processing plants are collectively owned and provide work for everyone who wants it. A mortgage is €15 per month, sport is played in a stadium emblazoned with a huge mural of Che Guevara, and there are monthly 'Red Sundays' when everyone works together to clean up the neighbourhood. Leading this revolution is the village mayor, Juan Manuel Sánchez Gordillo, who in 2012 became a household name in Spain after heading raids on local supermarkets to feed the Andalusian unemployed."

Of course, accepting what they have done Marinaleda seems to sanction anarchy and lawlessness. When you adopt a value system which is contrary to that upon which most of the laws around you are based, those terms are the ones that most easily come to mind. However, while that is certainly the context, I would like to look at some of the principles being put forward. The article, being a brief extract, is not very detailed, but three specific characteristics of their model are highlighted:

"Land belongs to those who work it"

In my opinion this is an unfortunate wording of an even grander ideal. Personally, I believe that land should belong to no-one. The concept of personal territory is one thing - it occurs throughout nature. But owning land? Especially land that you might never have set foot on? Buying and selling something that was not in any way produced by us? I prefer our millennia-old tradition of the humans belonging to the land, not the other way around. What the villagers are really saying (in my preferred interpretation) is that the output of the land - the food - should belong to the people who put the effort into growing it. And why should it be any other way?

"Everyone in the co-op earns the same salary"

This does not mean that everyone contributes the same amount, or even that everyone necessarily deserves an equal share. This (again in my personal interpretation) acknowledges the fact that even Marinaleda exists within a system where, to provide the basic necessities of life, one must have money. They have not yet eliminated that concept from their society (even if they could). Working from that, it is relatively safe to say that all of the residents have the same basic needs of food and shelter, and so the same salary should cover those for each person. When money is being used to satisfy basic needs, as opposed to being a determinant of what value people are bringing to the community or how much their individual skills and talents are worth, then it takes on a whole new meaning. If you can stop measuring happiness by wealth, then the concept of equal salaries becomes fairly benign.

"Our aim was not to create profit but to create jobs"

Face it, if everyone has the money they need to buy what they need for a good life, what do they need next? They need something to do. They need to be able to contribute to the greater good of the community (and thus their own well-being). I choose to believe that this is not about choosing labour-intensive crops as a make-work lifestyle so that everyone can make money. It is about maximizing the resource that you have (labour) so that people can pursue other pleasures without it being at the expense of their neighbour's happiness. At some level, the pursuit of efficiency crosses over the line from working smarter to catering to a very specific set of values (at the expense of more important values). As many non-industrial farmers will soon tell you, there is a joy and connection that comes from working the land - from growing and eating your own food. As it is everywhere with the idea of repairing things, when we stop seeing labour as an evil to be minimized, we learn to find the time to make better, more respectful choices of how to manage the resources that this planet provides to us. We produce durable, esthetically-pleasing goods. And we also discover a surprising level of satisfaction from developing the skills to feed ourselves and maintain the items that are important to our lives.

What should be most interesting is to see how Marinaleda fares in the worsening economic crisis that Spain now finds itself in. It may not be long before your own 'village' is facing the same dilemma. It is challenging to be a qualitative-value island in the middle of a quantitative-value ocean. However, that particular ocean is not actually very deep. Money only has power and value as long as we believe it does. If the population loses that belief, the value of money vanishes, and that could actually happen overnight.

In a nutshell (from his website), Dan's book is the story of the villagers of Marinaleda, Spain, "who expropriated the land owned by wealthy aristocrats and have, since the 1980s, made it the foundation of a cooperative way of life. Today, Marinaleda is a place where the farms and the processing plants are collectively owned and provide work for everyone who wants it. A mortgage is €15 per month, sport is played in a stadium emblazoned with a huge mural of Che Guevara, and there are monthly 'Red Sundays' when everyone works together to clean up the neighbourhood. Leading this revolution is the village mayor, Juan Manuel Sánchez Gordillo, who in 2012 became a household name in Spain after heading raids on local supermarkets to feed the Andalusian unemployed."

In a nutshell (from his website), Dan's book is the story of the villagers of Marinaleda, Spain, "who expropriated the land owned by wealthy aristocrats and have, since the 1980s, made it the foundation of a cooperative way of life. Today, Marinaleda is a place where the farms and the processing plants are collectively owned and provide work for everyone who wants it. A mortgage is €15 per month, sport is played in a stadium emblazoned with a huge mural of Che Guevara, and there are monthly 'Red Sundays' when everyone works together to clean up the neighbourhood. Leading this revolution is the village mayor, Juan Manuel Sánchez Gordillo, who in 2012 became a household name in Spain after heading raids on local supermarkets to feed the Andalusian unemployed."Of course, accepting what they have done Marinaleda seems to sanction anarchy and lawlessness. When you adopt a value system which is contrary to that upon which most of the laws around you are based, those terms are the ones that most easily come to mind. However, while that is certainly the context, I would like to look at some of the principles being put forward. The article, being a brief extract, is not very detailed, but three specific characteristics of their model are highlighted:

"Land belongs to those who work it"

In my opinion this is an unfortunate wording of an even grander ideal. Personally, I believe that land should belong to no-one. The concept of personal territory is one thing - it occurs throughout nature. But owning land? Especially land that you might never have set foot on? Buying and selling something that was not in any way produced by us? I prefer our millennia-old tradition of the humans belonging to the land, not the other way around. What the villagers are really saying (in my preferred interpretation) is that the output of the land - the food - should belong to the people who put the effort into growing it. And why should it be any other way?

"Everyone in the co-op earns the same salary"

This does not mean that everyone contributes the same amount, or even that everyone necessarily deserves an equal share. This (again in my personal interpretation) acknowledges the fact that even Marinaleda exists within a system where, to provide the basic necessities of life, one must have money. They have not yet eliminated that concept from their society (even if they could). Working from that, it is relatively safe to say that all of the residents have the same basic needs of food and shelter, and so the same salary should cover those for each person. When money is being used to satisfy basic needs, as opposed to being a determinant of what value people are bringing to the community or how much their individual skills and talents are worth, then it takes on a whole new meaning. If you can stop measuring happiness by wealth, then the concept of equal salaries becomes fairly benign.

"Our aim was not to create profit but to create jobs"

Face it, if everyone has the money they need to buy what they need for a good life, what do they need next? They need something to do. They need to be able to contribute to the greater good of the community (and thus their own well-being). I choose to believe that this is not about choosing labour-intensive crops as a make-work lifestyle so that everyone can make money. It is about maximizing the resource that you have (labour) so that people can pursue other pleasures without it being at the expense of their neighbour's happiness. At some level, the pursuit of efficiency crosses over the line from working smarter to catering to a very specific set of values (at the expense of more important values). As many non-industrial farmers will soon tell you, there is a joy and connection that comes from working the land - from growing and eating your own food. As it is everywhere with the idea of repairing things, when we stop seeing labour as an evil to be minimized, we learn to find the time to make better, more respectful choices of how to manage the resources that this planet provides to us. We produce durable, esthetically-pleasing goods. And we also discover a surprising level of satisfaction from developing the skills to feed ourselves and maintain the items that are important to our lives.

What should be most interesting is to see how Marinaleda fares in the worsening economic crisis that Spain now finds itself in. It may not be long before your own 'village' is facing the same dilemma. It is challenging to be a qualitative-value island in the middle of a quantitative-value ocean. However, that particular ocean is not actually very deep. Money only has power and value as long as we believe it does. If the population loses that belief, the value of money vanishes, and that could actually happen overnight.

Published on March 13, 2015 20:42

February 25, 2015

Who will bell the cat?

Last week, I attended my first discussion night as guest author of a book club that was discussing The Value Crisis. Early on in my several pages of notes is a series of questions posed to the group by one of the readers. "I agree with the book, BUT are we prepared to give up economic growth? Are we prepared to have our taxes go up or to take a cut in pay? Who here is prepared to give up their car?" Everyone stared at the floor.

In some sense, this is a classic demonstration of the value personae conflict that I describe in Chapter 10, or as Robert Reich described the flipside: "As consumers and investors we want the great deals. As citizens we don't like many of the social consequences that flow from them." But I think there is more to it.

I'm reminded of a childhood fable. A group of house mice were being terrorized by the homeowner's new cat. They held many meetings to figure out how to deal with the problem. Finally, one mouse jumped up and announced a solution. The catch, he said, was that the cat was always sneaking up on them. This could easily be solved by putting a bell round the cat's neck so that the mice would always know when the cat was coming. The other mice thought this was an amazing idea and loudly praised it's clever originator until a small voice peeped up from a young mouse at the back: "Um, excuse me - I have a question. Who will bell the cat?"

Even when the solution becomes apparent, implementing it is quite another matter.

The scenarios questioned by that reader may seem unpleasant indeed, but they don't have to be that extreme. I don't know the exact socio-economic status of those book club members, but I'll take a stab at this (and pray I don't insult anyone). Imagine you were in that group and you just took a 20% cut in pay. How would someone in this particular crowd deal with that? Perhaps every fifth year you would skip the annual vacation south. Perhaps once a week the standard red meat entrée would be replaced by a delicious vegetarian option. Instead of dining out twice a month, it might be every three weeks. Or you start carrying a travel mug of your own coffee instead of that daily Starbucks stop. You might keep your car an extra two years, and borrow rarely-used tools rather than buy your own. Or swap a movie night out for a DVD in. Why not write a heartfelt letter instead of buying a birthday card? You could spend a whole lot less on frivolous gifts at Christmas, or buy 20% fewer new clothes and shoes. For more dramatic results, what would happen if you cancelled your cable TV service? (Lots of channels still come in free!) Then there are the really tough questions like: Is my residential footprint appropriate when it's only me living here? (Not long ago, the number of single-person housing units actually exceeded the number of multi-person units in Canada.)

These might look like austerity measures, but you'll get more useful and positive information if you Google " voluntary simplicity " instead. Don't think of it as an externally imposed pay cut. Treat it as a decision to spend and consume less - and to find equivalent or even more joy in other ways. You might even orchestrate it yourself by taking every Friday off. It's a value shift that is needed, not a happiness reduction. The readers in this book club had already taken the first step - they recognized the problem and wanted to do something. They just weren't sure what to do next.

Then there's another class of people who recognize the problem and consciously choose to do nothing. I used to think they were simply in conflict. Now I believe that quite a few of them might be NIMPLEs. These are the folks who are shamelessly stealing prosperity and survival chances from the generations that follow in order to line their own pockets. "Yes, there may be a massive crisis ahead, but I'm a NIMPLE, and that disaster is Not In My Personal Lifespan Expectancy, so you and the grandkids can go to hell."

Will the next century be hell? It really depends on what we choose to do now. One of the more telling quotes from my book club visit was this one "Why vote in this riding? We know it's going to go Conservative." (This happens to be one of the strongest Green Party ridings in Canada. However, 40-50% of the electorate don't bother to vote.)

It's as if we are passengers in a slowly dissolving papier-mâché boat, watching the tide take us further away from dry land, but reluctant to swim for it because we don't want to get wet. Instead, we look around, hoping that someone will dive overboard and lead the way to shore. Even then, the choice to abandon ship won't be easy and it won't be super-comfortable. But The Value Crisis does make a case for us all being potentially happier, right now, by making those choices. (Maybe you will actually find these tropical waters warm and refreshing!)

"Change is good. You go first."- Dilbert (Scott Adams)

You don't have to be the first. Some of us have already got a bell on our cats. It wasn't easy, but in many ways, after we shifted our value perspective, life is a whole lot better and we can sleep at night. Why not join us?

In some sense, this is a classic demonstration of the value personae conflict that I describe in Chapter 10, or as Robert Reich described the flipside: "As consumers and investors we want the great deals. As citizens we don't like many of the social consequences that flow from them." But I think there is more to it.

I'm reminded of a childhood fable. A group of house mice were being terrorized by the homeowner's new cat. They held many meetings to figure out how to deal with the problem. Finally, one mouse jumped up and announced a solution. The catch, he said, was that the cat was always sneaking up on them. This could easily be solved by putting a bell round the cat's neck so that the mice would always know when the cat was coming. The other mice thought this was an amazing idea and loudly praised it's clever originator until a small voice peeped up from a young mouse at the back: "Um, excuse me - I have a question. Who will bell the cat?"

Even when the solution becomes apparent, implementing it is quite another matter.

The scenarios questioned by that reader may seem unpleasant indeed, but they don't have to be that extreme. I don't know the exact socio-economic status of those book club members, but I'll take a stab at this (and pray I don't insult anyone). Imagine you were in that group and you just took a 20% cut in pay. How would someone in this particular crowd deal with that? Perhaps every fifth year you would skip the annual vacation south. Perhaps once a week the standard red meat entrée would be replaced by a delicious vegetarian option. Instead of dining out twice a month, it might be every three weeks. Or you start carrying a travel mug of your own coffee instead of that daily Starbucks stop. You might keep your car an extra two years, and borrow rarely-used tools rather than buy your own. Or swap a movie night out for a DVD in. Why not write a heartfelt letter instead of buying a birthday card? You could spend a whole lot less on frivolous gifts at Christmas, or buy 20% fewer new clothes and shoes. For more dramatic results, what would happen if you cancelled your cable TV service? (Lots of channels still come in free!) Then there are the really tough questions like: Is my residential footprint appropriate when it's only me living here? (Not long ago, the number of single-person housing units actually exceeded the number of multi-person units in Canada.)

These might look like austerity measures, but you'll get more useful and positive information if you Google " voluntary simplicity " instead. Don't think of it as an externally imposed pay cut. Treat it as a decision to spend and consume less - and to find equivalent or even more joy in other ways. You might even orchestrate it yourself by taking every Friday off. It's a value shift that is needed, not a happiness reduction. The readers in this book club had already taken the first step - they recognized the problem and wanted to do something. They just weren't sure what to do next.

Then there's another class of people who recognize the problem and consciously choose to do nothing. I used to think they were simply in conflict. Now I believe that quite a few of them might be NIMPLEs. These are the folks who are shamelessly stealing prosperity and survival chances from the generations that follow in order to line their own pockets. "Yes, there may be a massive crisis ahead, but I'm a NIMPLE, and that disaster is Not In My Personal Lifespan Expectancy, so you and the grandkids can go to hell."

Will the next century be hell? It really depends on what we choose to do now. One of the more telling quotes from my book club visit was this one "Why vote in this riding? We know it's going to go Conservative." (This happens to be one of the strongest Green Party ridings in Canada. However, 40-50% of the electorate don't bother to vote.)

It's as if we are passengers in a slowly dissolving papier-mâché boat, watching the tide take us further away from dry land, but reluctant to swim for it because we don't want to get wet. Instead, we look around, hoping that someone will dive overboard and lead the way to shore. Even then, the choice to abandon ship won't be easy and it won't be super-comfortable. But The Value Crisis does make a case for us all being potentially happier, right now, by making those choices. (Maybe you will actually find these tropical waters warm and refreshing!)

"Change is good. You go first."- Dilbert (Scott Adams)

You don't have to be the first. Some of us have already got a bell on our cats. It wasn't easy, but in many ways, after we shifted our value perspective, life is a whole lot better and we can sleep at night. Why not join us?

Published on February 25, 2015 06:51

February 11, 2015

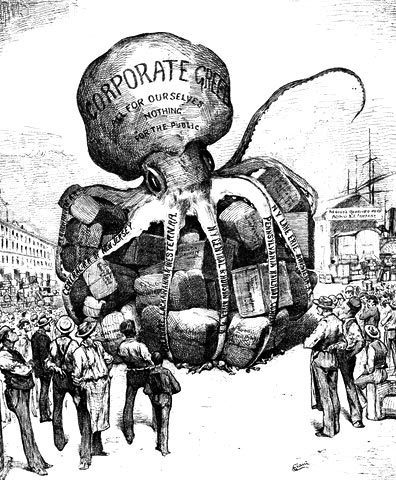

Corporate Greed? No such thing.

When I'm focused on writing, my reading naturally falls behind - especially when my reading would constantly be redirecting my writing! However, with The Value Crisis completed and published, I am at last trying to catch up, including taking an overdue dive into Naomi Klein's "This Changes Everything".

I have read "The Shock Doctrine" and generally find her work enlightening and inspiring. She has the kind of resources and contacts that I will never have, and I really appreciate her perspective. There is one philosophical point, however, that I believe she often defaults to - one that is shared by many people around the world - that is so fundamental, it deserves being questioned: Klein puts a lot of the planet's problems down to Corporate Greed.

My contention is that there is no such thing as corporate greed.

Some might say that I'm simply fussing over semantics, but I believe this is a worthy investigation. Words evoke framing and responses in the reader, and if they are inaccurate, they can send one down misleading and barren paths.

What is greed? I turned to a few dictionaries:

excessive desire to acquire or possess more than what one needs or deservesexcessive consumption of or desire for food; gluttonyexcessive desire, as for wealth or powerexcessive or rapacious desire, esp. for wealth or possessions; avarice; covetousness

The pivotal concept of greed is excess, or as wikipedia puts it: "desire to possess [...] far beyond the dictates of basic survival and comfort." So here's the critical point: If there are no dictates of sufficiency, there can be no greed.

For the purposes of this post, I discuss corporations with respect to publicly-traded, commercial corporations. These entities are created under very clear laws, defining their objectives, and setting out the criteria by which every one of their decisions and actions may be judged.

The number-one priority of any commercial corporation (imposed upon it by our laws) is the maximization of shareholder value. I have highlighted two key terms here: Maximization and Value. Let us begin with the second.

Value in the commercial world is measured exclusively by money - by number. Any other goals or interests must distill back down to a clear impact on the bottom line. This is a number-based value system, and, as I make clear in my book, one characteristic of such systems is that more is always of greater value - more is always better. The objective of value maximization is therefore easy and obvious, achieved by growth and the acquisition of more.

It is not possible under such a value system (and under such laws) to say that any corporate desire is excessive. In excess of what? There is no concept of sufficiency. We have instructed (indeed, demanded) that this entity continue to maximize shareholder value, continue to grow, continue to produce revenue. What is needed to maintain that growth will itself grow.

At this point, I should make some key distinctions. Rex Tillerson, CEO of Exxon Mobil, pays himself $100,000 every day. Excess? Greed? An insult to humanity? You bet. However, who can say what the sufficient annual revenue should be for Exxon Mobil? His societal obscenity simply follows from our inability to deal with the real question: why have we facilitated (and indeed encouraged) his excess by defining corporations as we have?

I wrote this post because I believe we are at great risk of confusing the lucky 1% at the top with the system that put them there. To go into the psychology of the folks at the top of the pyramid would be a separate exploration altogether. What I caution is the use of the term "corporate greed". It implies that corporations are improperly taking more than their fair share, when in reality, there is no such thing as a defined fair share. It implies that corporations have gone astray, when in reality, they are performing precisely as we have programmed them to do.

If anything, it is our greed that inspires these creations, keeps them focused on profit, and satisfies their need for consumers to buy their goods.

Published on February 11, 2015 08:29

January 19, 2015

Reflections on "The Value Crsis"

The original publication of "The Value Crisis" has proved to be quite popular with book clubs. As a result, I prepared a number of questions, organized by chapter, that might serve as a good inspiration for self-reflection or group discussion. I share them here, both for other readers to make use of, and in the hope that some answers might be posted in the comments section below. Please add your thoughts!

Introduction

Do you ever think about any of the questions on page 10 (listed below)?

Why do we have to consume and throw out so much stuff?Why do certain individuals get paid so much money for doing so little?Why do we seem to have less time than previous generations, not more?Why does it cost more to repair things than to replace them?Why are labour disruptions, disliked on all sides, still common?Why do we in democracies disagree so much with our elected leaders and governments?Why do we consciously choose to poison our own natural environment?Why are so many of us not even sure what makes us happy anymore? How would you answer them now?

Chapter 1 – The Rise of Numbers

How would you answer the three questions on page 30/31 (listed below)?

What happens if our natural value systems are pushed aside in favour of numerical ones?Are number-based value systems really objective? Can they be trusted?What happens when we try to combine qualitative and quantitative value scales?What qualitative values are important to you? Are there number-based values that threaten their influence?

Chapter 2 – Decision-Making and Numbers

Can you think of any decisions you made where you consciously decided to ignore or downplay the relevant numbers? What happened?

Chapter 3 – Money: The Number Culture

What practices would you follow when buying goods in a developing country?

How does country of origin affect your shopping choices? Why?

Chapter 4 – What’s Your Motiviation?

In what ways is money a motivator for you? How might that affect your emotional well-being?

Chapter 5 – The Value of Time

The author proposes that we should pay more for materials and less for labour. What do you think of this concept?

If you could, how would you alter the amount of time you have and how would you spend it? What prevents you from doing this?

Chapter 6 – Banking on Numbers

The author proposes that value creation based on math alone should be dispensed with, including interest charges. Do you agree or disagree?

Chapter 7 – Numbers Incorporated

Do you think a hierarchy of needs can be generally applied to corporations? Would you agree with the author’s choices for the levels?

Chapter 8 – Numbering Our Days

The concept of polarities is a powerful one. Can you think of other pairs of conflicting forces in your life that might be a polarity, to be managed instead of solved?

Chapter 9 – Numbers Rule

The author considers chapter 9 to be something of a ‘rogue’ chapter. Perhaps his most radical proposal is to question the superior value of choices just because they get more votes. What was your reaction to this somewhat ‘radical’ thinking?

Chapter 10 – Value Systems in Conflict

Can you think of examples where your personal value personae are in conflict? How do you resolve that conflict?

If the author is right that our ‘citizen’ values are not properly championed in modern society, how might we try to collectively bring all three value types back into balance?

Conclusion

The author envisions the inevitable collapse our current state of affairs, one way or another. Do you agree? How would you prepare for such a collapse?

Has the book changed your perspective on any of the world around you? Is there anything you might now consider doing differently?

The author would greatly value feedback of any kind on this book. Please consider adding a comment below or to GoodReads.com or via direct email.

Introduction

Do you ever think about any of the questions on page 10 (listed below)?

Why do we have to consume and throw out so much stuff?Why do certain individuals get paid so much money for doing so little?Why do we seem to have less time than previous generations, not more?Why does it cost more to repair things than to replace them?Why are labour disruptions, disliked on all sides, still common?Why do we in democracies disagree so much with our elected leaders and governments?Why do we consciously choose to poison our own natural environment?Why are so many of us not even sure what makes us happy anymore? How would you answer them now?

Chapter 1 – The Rise of Numbers

How would you answer the three questions on page 30/31 (listed below)?

What happens if our natural value systems are pushed aside in favour of numerical ones?Are number-based value systems really objective? Can they be trusted?What happens when we try to combine qualitative and quantitative value scales?What qualitative values are important to you? Are there number-based values that threaten their influence?

Chapter 2 – Decision-Making and Numbers

Can you think of any decisions you made where you consciously decided to ignore or downplay the relevant numbers? What happened?

Chapter 3 – Money: The Number Culture

What practices would you follow when buying goods in a developing country?

How does country of origin affect your shopping choices? Why?

Chapter 4 – What’s Your Motiviation?

In what ways is money a motivator for you? How might that affect your emotional well-being?

Chapter 5 – The Value of Time

The author proposes that we should pay more for materials and less for labour. What do you think of this concept?

If you could, how would you alter the amount of time you have and how would you spend it? What prevents you from doing this?

Chapter 6 – Banking on Numbers

The author proposes that value creation based on math alone should be dispensed with, including interest charges. Do you agree or disagree?

Chapter 7 – Numbers Incorporated

Do you think a hierarchy of needs can be generally applied to corporations? Would you agree with the author’s choices for the levels?

Chapter 8 – Numbering Our Days

The concept of polarities is a powerful one. Can you think of other pairs of conflicting forces in your life that might be a polarity, to be managed instead of solved?

Chapter 9 – Numbers Rule

The author considers chapter 9 to be something of a ‘rogue’ chapter. Perhaps his most radical proposal is to question the superior value of choices just because they get more votes. What was your reaction to this somewhat ‘radical’ thinking?

Chapter 10 – Value Systems in Conflict

Can you think of examples where your personal value personae are in conflict? How do you resolve that conflict?

If the author is right that our ‘citizen’ values are not properly championed in modern society, how might we try to collectively bring all three value types back into balance?

Conclusion

The author envisions the inevitable collapse our current state of affairs, one way or another. Do you agree? How would you prepare for such a collapse?

Has the book changed your perspective on any of the world around you? Is there anything you might now consider doing differently?

The author would greatly value feedback of any kind on this book. Please consider adding a comment below or to GoodReads.com or via direct email.

Published on January 19, 2015 09:58

December 10, 2014

The first review

The first full review of The Value Crisis was just published in Tapestry Magazine (King Township, Winter 2015) Reprinting it here gives me an open forum where other readers can post comments and feedback. Please chime in!

Thank you for that, Hugh Marchand. My next major initiative is to offer book club sets to book clubs and libraries. Book clubs are the perfect forum to find readers eager to discuss these ideas. Having an author that is willing to attend their discussion night is even better!

reviewed by Hugh Marchand

"In The Value Crisis, Andrew Welch voices the concern – and examines the causes - that many of us have but cannot articulate as well as he does: that human values everywhere are decaying at an alarming rate. And yet, collectively, we seem helpless or resistant to doing anything about it. Why? He adroitly sidesteps the blame games played by competing ideologies and economic interests and suggests instead a more fundamental cause – that we are witnessing the growing dominance of number-based value systems to the detriment of age-old human value systems. Human value systems deal with quality of life, while number-based systems value quantity, and implicit in that is the possibility (and danger) of unchecked growth.

This is an elegant thesis that is launched through a series of simple questions that any uneasy person might ask. An example: “Why does it cost more to repair things than to replace them?” Reviewing all the questions piques our curiosity. We want to know what it is that underlies this list of seemingly unrelated inquiries.

The author does not disappoint us; this is no stodgy economics text book, and anyone who suffers from math phobia has nothing to fear from this book. The language is plain and jargon-free; technical terms where needed for understanding, are reduced to simple expressions. Given the seriousness of the present situation as the author presents it, and the implications for the future, this is a surprisingly upbeat read.

The impact of undue reliance of number-based value systems is examined in detail in topics as wide-ranging as decision-making, international banking and currency, the unregulated power of corporations, and the erosion of our democratic institutions. Welch brings to the discussion his interests and expertise in the arts, environmental and social issues, and his solid grounding in education, business and mathematics. Throughout the piece his linking of personal anecdotes to the study of the larger issues provides remarkable clarity to what he has to say.

His objective is also clear, as evidenced by www.TheValueCrisis.com and the associated open blog: To inspire discussions for a new way of considering the multiple challenges facing us.

The thrust of Andrew Welch’s book is to bring awareness of the coming and seemingly inevitable catastrophe. His call to action is realistic and not devoid of optimism: We cannot prevent what is coming, he states, but we can “ease the transition” and he cites examples of what can be done. His speculation that a catastrophe may sweep away many elements of number-based value systems and improve the quality of life for many, is based on plausible economic theory. This is a thought-provoking book that you should read, act upon, and share."

Thank you for that, Hugh Marchand. My next major initiative is to offer book club sets to book clubs and libraries. Book clubs are the perfect forum to find readers eager to discuss these ideas. Having an author that is willing to attend their discussion night is even better!

Published on December 10, 2014 20:23

October 31, 2014

David Welch meets Goliath Gladwell

Another reader wrote to me, having just finished The Value Crisis:

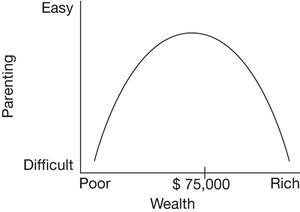

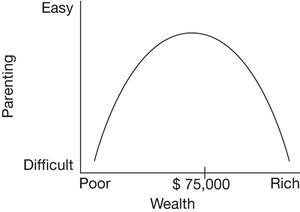

To briefly summarize Gladwell's presentation of an Inverted-U Curve, he was describing how one might graph the difficulty of parenting versus the wealth of the parent (see the graph below). While it is easy to see that parenting is hard for a poor parent and gets easier as wealth increases, the argument is that parenting is also hard for very rich parents. (This Deseret News article explains.) So the graph goes up (towards easier parenting) as wealth increases, but then it reaches a peak and curves back down - thus the label "Inverted-U Curve".

This curve is presented to counter our intuitive assumptions about parenting getting easier as wealth increases - it is not the straight line graph that we might expect. He suggests that the same curve would apply if we are graphing academic achievement against class size. In other words, more of a good thing is not always a good thing. This is something I talk about a lot in The Value Crisis.

(I don't know where the $75,000 figure came from for the graph's peak - Gladwell is notorious for letting the science take a backseat to a good story. I note that other research talks about general happiness leveling off when annual income reaches about $75,000. Perhaps this is an interesting correlation or perhaps Gladwell simply borrowed the same figure for his graph.)

The interesting thing for me about Inverted-U Curves is that they suggest there is often an optimal value for things. In most situations this point is obvious, but we more often get tripped up when the horizontal axis is measuring a number-based value system. In the monetary number-based value system, more wealth is always worth more. So we assume that the same valuation applies to the qualitative human circumstances such as ease of parenting. Not so.

The optimal peak value might also represent the concept of "enough". However, I caution the idea that such values can be empirically determined and then used as human or policy goals. The reality for most things in life is that they manifest themselves as polarities - unsolvable problems with no single optimum solution. An example of a polarity in the business world is teamwork versus individual effort. Neither is the optimum approach to work. Sometimes we do better with one, sometimes with its opposite.

Here's another Inverted-U Curve, showing the business relationship between incentives for innovation and levels of competition:

With no competition, there is no incentive to innovate. When competition is high, the cost of innovation can be detrimental. So a business will be most successful when the level of competition corresponds to the innovation sweet spot, right? Not quite. Sometimes, innovation itself is bad for business, and a maintenance of tradition is the preferred strategy. (Innovation and Tradition are two opposite poles of a polarity.) Using the same forces at work in the above innovation graph, we can argue that incentives for maintaining tradition will be high when the competition is low and also when the competition is fierce. There will also be a spot directly below the innovation incentive peak, where it will be most difficult to maintain tradition.

Overall, there is no sweet spot for level of competition. Sometimes, the level of competition will increase the incentive for innovation, sometimes it will increase the incentive for tradition, and both can be good.

Malcolm Gladwell argues that more of a good thing is not always a good thing, and that sometimes, if we apply the right value system, we will discover optimal states - the concept of "enough". The Value Crisis argues the same thing, but also suggests that we should be aware of what situations in life are polarities, with no optimal solutions.

The bottom line is that number-based value systems - where more is always worth more (by definition) - are incompatible with the qualitative natural values that are necessary to our happiness and continued existence on this planet. Decisions that support the maximization of number-based values (such as wealth or sales or economic growth or volume of resources extracted) will eventually go way past the optimal point.

So here's the real question: Why do we so blindly run our lives and our world in constant pursuit of maximization on the horizontal axis instead of on the vertical one?!

I have just also read 'David & Goliath' by Malcolm Gladwell. You would enjoy chapter two and its description of the Inverted U. I'm not sure how this might transfer to the world of money - although the book does give one or two limited examples. See what you think.While I was familiar with Gladwell's interesting take on David and Goliath from a TED talk, I had not yet read his book, so I went to the library to read up. Sure enough, some interesting ideas emerged. (I confess that this post might hint at some hefty mathematical concepts, but I'll try to keep it simple.)

To briefly summarize Gladwell's presentation of an Inverted-U Curve, he was describing how one might graph the difficulty of parenting versus the wealth of the parent (see the graph below). While it is easy to see that parenting is hard for a poor parent and gets easier as wealth increases, the argument is that parenting is also hard for very rich parents. (This Deseret News article explains.) So the graph goes up (towards easier parenting) as wealth increases, but then it reaches a peak and curves back down - thus the label "Inverted-U Curve".

This curve is presented to counter our intuitive assumptions about parenting getting easier as wealth increases - it is not the straight line graph that we might expect. He suggests that the same curve would apply if we are graphing academic achievement against class size. In other words, more of a good thing is not always a good thing. This is something I talk about a lot in The Value Crisis.

(I don't know where the $75,000 figure came from for the graph's peak - Gladwell is notorious for letting the science take a backseat to a good story. I note that other research talks about general happiness leveling off when annual income reaches about $75,000. Perhaps this is an interesting correlation or perhaps Gladwell simply borrowed the same figure for his graph.)

The interesting thing for me about Inverted-U Curves is that they suggest there is often an optimal value for things. In most situations this point is obvious, but we more often get tripped up when the horizontal axis is measuring a number-based value system. In the monetary number-based value system, more wealth is always worth more. So we assume that the same valuation applies to the qualitative human circumstances such as ease of parenting. Not so.

The optimal peak value might also represent the concept of "enough". However, I caution the idea that such values can be empirically determined and then used as human or policy goals. The reality for most things in life is that they manifest themselves as polarities - unsolvable problems with no single optimum solution. An example of a polarity in the business world is teamwork versus individual effort. Neither is the optimum approach to work. Sometimes we do better with one, sometimes with its opposite.

Here's another Inverted-U Curve, showing the business relationship between incentives for innovation and levels of competition:

With no competition, there is no incentive to innovate. When competition is high, the cost of innovation can be detrimental. So a business will be most successful when the level of competition corresponds to the innovation sweet spot, right? Not quite. Sometimes, innovation itself is bad for business, and a maintenance of tradition is the preferred strategy. (Innovation and Tradition are two opposite poles of a polarity.) Using the same forces at work in the above innovation graph, we can argue that incentives for maintaining tradition will be high when the competition is low and also when the competition is fierce. There will also be a spot directly below the innovation incentive peak, where it will be most difficult to maintain tradition.

Overall, there is no sweet spot for level of competition. Sometimes, the level of competition will increase the incentive for innovation, sometimes it will increase the incentive for tradition, and both can be good.

Malcolm Gladwell argues that more of a good thing is not always a good thing, and that sometimes, if we apply the right value system, we will discover optimal states - the concept of "enough". The Value Crisis argues the same thing, but also suggests that we should be aware of what situations in life are polarities, with no optimal solutions.

The bottom line is that number-based value systems - where more is always worth more (by definition) - are incompatible with the qualitative natural values that are necessary to our happiness and continued existence on this planet. Decisions that support the maximization of number-based values (such as wealth or sales or economic growth or volume of resources extracted) will eventually go way past the optimal point.

So here's the real question: Why do we so blindly run our lives and our world in constant pursuit of maximization on the horizontal axis instead of on the vertical one?!

Published on October 31, 2014 12:41

October 9, 2014

SMART Goals and Anecdotal Evidence

A reader who works as a teacher wrote to me the other day:

Such targets are often referred to as SMART goals - goals that are (S)pecific, (M)easurable, (A)cheivable, (R)elevant, and (T)imelined. Since The Value Crisis talks about how that which cannot be measured is dismissed in this age of scientific thinking, I started to wonder whether that also means that unmeasurable goals therefore 'lack validity' in modern society.

Such targets are often referred to as SMART goals - goals that are (S)pecific, (M)easurable, (A)cheivable, (R)elevant, and (T)imelined. Since The Value Crisis talks about how that which cannot be measured is dismissed in this age of scientific thinking, I started to wonder whether that also means that unmeasurable goals therefore 'lack validity' in modern society.

I'm guessing there are three reasons for making a goal measurable. The first is so that you can track progress and see if you are doing the right things. The second is so that you will know when you have achieved your goal and can celebrate accordingly. The third (more cynical reason) is for promises made in the public sphere, so that you can prove to others that, despite appearances, your target has been reached, according to objective measure. (This might be where classic manipulations of statistics come into play.)

But what if your goal can't be measured so easily? What if your aim is to be a better parent or to be happier? The experts would say that you need some way of measuring this. I say that's nonsense. If you didn't need a measurement to identify the need for the goal in the first place, you don't need a measurement to know if you are experiencing success.

(I tried to come up with a new M-word for qualitative SMART goals. So far, the best that I've come up with is "Motivational": If you are motivated to continue what you're doing, you are likely moving towards the goal that you desired in the first place. Please make better suggestions!)

So if you're not measuring your progress by some quantifying means, what can you use for feedback on your goal? Well, you might go with anecdotal evidence. <Insert dramatic organ chord.> Anecdotal evidence! The mere use of the term immediately raises the hackles on statisticians' necks. Well, I'm here as the Devil's Advocate to suggest that anecdotal evidence still has plenty of value when drawing general conclusions. On the other hand, the scientific method, when applied inappropriately, can actually the lower value of information.

I'll illustrate this with an old story (an anecdote!) of three professors traveling on a train through a foreign land. The historian, looking out the window and seeing a black sheep grazing alone on the hillside, says: "How interesting! The sheep of this land are black." The statistician looks out and says: "Well, to be more correct, what we know is that in this part of the country there is one sheep that is black." The philosopher, without looking up from his book, immediately corrects him: "Actually all we can say for certain is that in this specific area there is a sheep which is black on one side."

Had I been in the next seat, I might have added my own quip: "Excuse me, gentlemen, but I believe the only conclusion you can draw is that, looking out the window of this train, an object was observed that looked like what you know of as a sheep, whose wool (at least what you could see) appeared to be very dark in colour." The historian's statement could clearly be misleading. The statistician tried to make a more accurate (and thus, presumably, more valuable) statement. However, further refinements reduced what began as a simple observation to a meaningless statement, of no practical value to anyone. So where does anecdotal evidence cross the line from being a scientific menace to being meaningful and useful information?

As a scientist, I am fully aware of the abuse heaped upon anecdotal evidence - and rightly so, when it is used to 'prove' things that can only be proved by more rigorous analysis. On the flip side, one might argue that almost everything we know, as individuals, comes from anecdotal evidence. We know that last year's vacation was enjoyable or that last night's movie was boring because that was how we experienced them. We know that flying insects with yellow-and-black-striped bodies can inflict pain, either through personal history or from the anecdotes of others - that might not be 100% true every time, but it is certainly very useful information. Indeed, at one time, the entire store of mankind's knowledge was anecdotal and communicated through story-telling. You may say that it was naive and imperfect, but if I were stranded in the wilderness, I would take the knowledge of our Stone Age ancestors over that of your average physicist any day of the week.

The very things that make anecdotal evidence suspect - such as our innate propensity to focus on exceptional events (confirmation bias) can have their own value. For example, one adult, telling a child that they are clever enough to do well in school, can alter that child's self-esteem, willingness to work hard, and ultimately improve their academic performance, even if many other adults are providing only discouragement. (I heard about that happening once, so it must be true. ;-) Even medical researchers have to concede the validity of the placebo effect, in which measurable outcomes can be altered by our own beliefs in anecdotal evidence.

So where am I going with all this?

Our brains are wired to make use of anecdotal evidence, and while we sometimes get it wrong, I'll wager that it is (more often than not) useful and valuable information. A single anecdote, such as being out of breath after climbing some stairs, can suggest to us that perhaps we are out of shape and need to exercise more. If a few more pieces of breathless anecdotal evidence confirm this, we might set a goal to improve our physical fitness. If we start being more active because of this and find that we can now take the same set of stairs two steps at a time with ease, then we there is no need for science to measure whether or not we have improved our muscle tone or cardiac output. It is sufficient and rewarding enough for us to feel we have succeeded in what we set out to do and be happier for the effort.

Similarly, in life, if it is our goal to be happier (and who wouldn't want that?), then we don't need measurable 'SMART' goals to tell us if we are doing the right things. As for my teacher friend, while you might want quantifiable studies to alter policies for the entire board, that does not change the fact that in a specific classroom, for a specific child, anecdotal evidence is the best proof available that what you are doing is working, or not. So why does number-based policy so often trump anecdotal evidence for individual circumstances?

P.S. If classroom marks were the truest indicator of value and potential, I wouldn't be here.

I thought of your book once again this week, in an all day meeting of our school leadership team. We spent the morning confirming that there is much more to educating young people than just generating marks, and that just focusing on numeric measures was the wrong way to go. And then we spent the afternoon talking about nothing but numbers. Stupid numbers. Like the TDSB Director's vision to decrease the number of students needing Special Ed support by 50%. (Maybe they just need extra vitamins.) And stupid comparisons of unrelated data, like the achievement of one group of 14-year-olds vs the achievement of an entirely different group of 14-year-olds a year later. Actually understanding statistics has become a curse!The Toronto District School Board (TDSB) comment got me curious, so I looked on the web and found their Years of Action: 2013-2017 report. This document promises 36 separate actions, resulting in 102 different outcomes - most of which have numeric measurements attached. Wow. 102 targets that the TDSB can be directly scored on.

Such targets are often referred to as SMART goals - goals that are (S)pecific, (M)easurable, (A)cheivable, (R)elevant, and (T)imelined. Since The Value Crisis talks about how that which cannot be measured is dismissed in this age of scientific thinking, I started to wonder whether that also means that unmeasurable goals therefore 'lack validity' in modern society.

Such targets are often referred to as SMART goals - goals that are (S)pecific, (M)easurable, (A)cheivable, (R)elevant, and (T)imelined. Since The Value Crisis talks about how that which cannot be measured is dismissed in this age of scientific thinking, I started to wonder whether that also means that unmeasurable goals therefore 'lack validity' in modern society.I'm guessing there are three reasons for making a goal measurable. The first is so that you can track progress and see if you are doing the right things. The second is so that you will know when you have achieved your goal and can celebrate accordingly. The third (more cynical reason) is for promises made in the public sphere, so that you can prove to others that, despite appearances, your target has been reached, according to objective measure. (This might be where classic manipulations of statistics come into play.)

But what if your goal can't be measured so easily? What if your aim is to be a better parent or to be happier? The experts would say that you need some way of measuring this. I say that's nonsense. If you didn't need a measurement to identify the need for the goal in the first place, you don't need a measurement to know if you are experiencing success.

(I tried to come up with a new M-word for qualitative SMART goals. So far, the best that I've come up with is "Motivational": If you are motivated to continue what you're doing, you are likely moving towards the goal that you desired in the first place. Please make better suggestions!)

So if you're not measuring your progress by some quantifying means, what can you use for feedback on your goal? Well, you might go with anecdotal evidence. <Insert dramatic organ chord.> Anecdotal evidence! The mere use of the term immediately raises the hackles on statisticians' necks. Well, I'm here as the Devil's Advocate to suggest that anecdotal evidence still has plenty of value when drawing general conclusions. On the other hand, the scientific method, when applied inappropriately, can actually the lower value of information.

I'll illustrate this with an old story (an anecdote!) of three professors traveling on a train through a foreign land. The historian, looking out the window and seeing a black sheep grazing alone on the hillside, says: "How interesting! The sheep of this land are black." The statistician looks out and says: "Well, to be more correct, what we know is that in this part of the country there is one sheep that is black." The philosopher, without looking up from his book, immediately corrects him: "Actually all we can say for certain is that in this specific area there is a sheep which is black on one side."

Had I been in the next seat, I might have added my own quip: "Excuse me, gentlemen, but I believe the only conclusion you can draw is that, looking out the window of this train, an object was observed that looked like what you know of as a sheep, whose wool (at least what you could see) appeared to be very dark in colour." The historian's statement could clearly be misleading. The statistician tried to make a more accurate (and thus, presumably, more valuable) statement. However, further refinements reduced what began as a simple observation to a meaningless statement, of no practical value to anyone. So where does anecdotal evidence cross the line from being a scientific menace to being meaningful and useful information?

As a scientist, I am fully aware of the abuse heaped upon anecdotal evidence - and rightly so, when it is used to 'prove' things that can only be proved by more rigorous analysis. On the flip side, one might argue that almost everything we know, as individuals, comes from anecdotal evidence. We know that last year's vacation was enjoyable or that last night's movie was boring because that was how we experienced them. We know that flying insects with yellow-and-black-striped bodies can inflict pain, either through personal history or from the anecdotes of others - that might not be 100% true every time, but it is certainly very useful information. Indeed, at one time, the entire store of mankind's knowledge was anecdotal and communicated through story-telling. You may say that it was naive and imperfect, but if I were stranded in the wilderness, I would take the knowledge of our Stone Age ancestors over that of your average physicist any day of the week.

The very things that make anecdotal evidence suspect - such as our innate propensity to focus on exceptional events (confirmation bias) can have their own value. For example, one adult, telling a child that they are clever enough to do well in school, can alter that child's self-esteem, willingness to work hard, and ultimately improve their academic performance, even if many other adults are providing only discouragement. (I heard about that happening once, so it must be true. ;-) Even medical researchers have to concede the validity of the placebo effect, in which measurable outcomes can be altered by our own beliefs in anecdotal evidence.

So where am I going with all this?

Our brains are wired to make use of anecdotal evidence, and while we sometimes get it wrong, I'll wager that it is (more often than not) useful and valuable information. A single anecdote, such as being out of breath after climbing some stairs, can suggest to us that perhaps we are out of shape and need to exercise more. If a few more pieces of breathless anecdotal evidence confirm this, we might set a goal to improve our physical fitness. If we start being more active because of this and find that we can now take the same set of stairs two steps at a time with ease, then we there is no need for science to measure whether or not we have improved our muscle tone or cardiac output. It is sufficient and rewarding enough for us to feel we have succeeded in what we set out to do and be happier for the effort.

Similarly, in life, if it is our goal to be happier (and who wouldn't want that?), then we don't need measurable 'SMART' goals to tell us if we are doing the right things. As for my teacher friend, while you might want quantifiable studies to alter policies for the entire board, that does not change the fact that in a specific classroom, for a specific child, anecdotal evidence is the best proof available that what you are doing is working, or not. So why does number-based policy so often trump anecdotal evidence for individual circumstances?

P.S. If classroom marks were the truest indicator of value and potential, I wouldn't be here.

Published on October 09, 2014 19:51

September 19, 2014

Taking Action - What Now?

Early feedback on my book sometimes bemoaned the lack of concrete actions given that can be taken in response to the value crisis that is posited by the work. There are a number of reasons for this: I did not set out to propose solutions - my objective of presenting civilization's greatest challenges from a new perspective was daunting enough. I needed to first discover if my approach would have resonance with others. Moreover, I didn't have specific actions in mind. Frankly, my idealism surpasses my formal training or practical experience in global sociological change.

All that being said, if readers did accept my paradigm, I could not simply ignore the frustrating question of "So what do about all this?"

Indeed, I don't think it was ignored, but my responses may not have been very clearly spelled out. For example, one of the consistent approaches that I adopted was to present each chapter topic in the context of a personal anecdote - often the event that inspired my original thoughts in the first place. One could certainly derive actions from some of the behaviours described that I have found useful for myself.

Also, an important element of the book is the boxed text "Key Ideas" that appear throughout the work. Reading through the summary of these ideas, listed after the Conclusion, it is not difficult to derive some specific actions that motivated readers could take in response the the value crisis. Let's look at what some of these might be.

1. ACCEPT that you can never maximize a number-based value such as wealth, so that is meaningless as a goal.

2. RECOGNIZE that true values are specific to context, culture, and individual. They cannot be translated into a number.

3. SPEND your hours in ways that produce genuine non-numeric value for yourself and for others.

4. AVOID usury, debt of any kind, and false wealth creation by math alone.

5. KNOW that corporations are driven by our actions. If we change, they will too.

6. REFUSE to accept economic growth as a goal or even a measure of your government’s success.

7. VOTE out false democracies and flawed systems such as “first-past-the-post”.

8. START your own transition now, before the system collapse does it for you.

There, that should get the some of the conversation started...!

All that being said, if readers did accept my paradigm, I could not simply ignore the frustrating question of "So what do about all this?"

Indeed, I don't think it was ignored, but my responses may not have been very clearly spelled out. For example, one of the consistent approaches that I adopted was to present each chapter topic in the context of a personal anecdote - often the event that inspired my original thoughts in the first place. One could certainly derive actions from some of the behaviours described that I have found useful for myself.

Also, an important element of the book is the boxed text "Key Ideas" that appear throughout the work. Reading through the summary of these ideas, listed after the Conclusion, it is not difficult to derive some specific actions that motivated readers could take in response the the value crisis. Let's look at what some of these might be.

1. ACCEPT that you can never maximize a number-based value such as wealth, so that is meaningless as a goal.

As Benjamin Franklin wisely said: "Money never made a man happy yet, nor will it. There is nothing in its nature to produce happiness. The more a man has, the more he wants. Instead of filling a vacuum, it makes one. If it satisfies one want, it doubles and trebles that want another way." Money is a tool - a means to a goal of real value. Determine what that real objective is for you, and pursue that instead. By doing so, you define wealth sufficiency. Let your standard of living determine your income, not the other way around. Reducing the amount of money that you need will achieve happiness far more easily than trying to increase your income.

2. RECOGNIZE that true values are specific to context, culture, and individual. They cannot be translated into a number.

Make a conscious effort to stop thinking about value in terms of numbers. Choose quality over quantity. Don't measure your love for others by the amount of money you spend on unneeded gifts. Yes, the plight of low-income families in the West is such that shopping at WalMart for cheap goods from China might be a necessity. But those big box and dollar stores are also filled with plenty of well-heeled shoppers looking for bargains and deals. Stripping resources for goods that won't last and filling up land-fills with single-use products shows no respect for the planet we leave to our children. Instead of asking "How can I pass up on this great price?", ask yourself "Do I really need this item?" I do appreciate the very human joy that can come from getting a great deal - we are all wired that way. So try barter, borrowing and gifting with your friends and neighbours. Those are real win-win transactions.

3. SPEND your hours in ways that produce genuine non-numeric value for yourself and for others.

This is usually done through activities that number-based thinking would consider a “waste of time”. No, you don't have to start weaving your own clothing - unless that brings you joy. You can start by simply repairing more things, reusing more resources, volunteer more, help out your neighbour, be productive in a non-quantitative way. Such pursuits can truly be rewarding beyond measure.

4. AVOID usury, debt of any kind, and false wealth creation by math alone.

Contrary to modern usage, the term "usury" actually applies to any agreed transaction where wealth is transferred without a corresponding addition of value or sharing of risk. Money should represent a transfer or storage of real (past) value. So don't borrow money from banks. When you get a bank loan, it does not come from the money on deposit with the bank. Instead, the bank creates this money from nothing, based on your signature. Money borrowed from a bank represents future wealth that does not yet exist - wealth that must be created by society from nothing, just to cover the interest. Buying now and paying later is not just a trick for instant gratification - that debt accumulates on our planet as well as on our account. It is a mindset that will eventually destroy the ability for the planet we live on to cough up the balance that we need for survival.

5. KNOW that corporations are driven by our actions. If we change, they will too.

So change your actions. Mining and petroleum conglomerates might be wreaking environmental havoc in search of profit, but the demand and the money come from us. If we are willing to buy motion-activated plug-in air fresheners that spray chemicals into our living space, someone will make them.

6. REFUSE to accept economic growth as a goal or even a measure of your government’s success.

Managing the economy is the job of the marketplace and the corporations. They are both focused on growing the economy. The mandate of government should be to represent our unquantifiable citizen values. We must demand that governments end their false mandate of focusing on Consumer and Investor values. Citizen values must come first, not economic growth. The first step is to measure Genuine Wealth instead of GDP. This is an initiative that has been started all over the world and is being promoted by the UN. Insist that your own governments start adopting those measures.

7. VOTE out false democracies and flawed systems such as “first-past-the-post”.

Here's a bold claim: Representative democracies are unfair and ineffective. You'll have to read Chapter 9 to know how I backup that assertion. That chapter also introduces the concept of a wikiocracy - believe it or not, they are already out there. I suggest that we all try to support alternative systems that allow for increased involvement in decision-making for anyone who chooses to get involved. Participative democracies are slowly being established in some forward-thinking municipalities. Make yours one of them.

8. START your own transition now, before the system collapse does it for you.

The crisis is coming. I can't tell you whether it will be an economic collapse of an energy shortage or an environmental disaster or all three. But maintaining the current system is impossible. Why wait for the rug to be pulled out from under you? The good news is that achieving greater self-sufficiency, neighbourly interdependence, community resilience, and human value prominence can give us a higher quality of life right now.

There, that should get the some of the conversation started...!

Published on September 19, 2014 12:39

August 18, 2014

The Stray Coin

Early in the writing of The Value Crisis, I was trying to wrap my head around different behaviours that I was observing in myself and others. It seemed to be that some people used number-based value thinking more than others, and I tried to find a simple way to illustrate this and perhaps even test for whether or not they were "Quantifiers" or not.

I have since abandoned the idea of trying to divide people into "Quantifiers" and "Qualifiers" in preference for the Value Personae theory that I based on the work of Robert Reich. In Supercapitalism, Reich described different mindsets that we operate under: the consumer/investor and the citizen. In Chapter Ten, I consider these as three distinct versions of what I call our value personae, and explore how they operate in an individual and collectively at the societal level.

Still, one scenario (that didn't make it into the book) remained as a useful way to consider these different behaviours. It went something like this:

You’re walking down the street on a sunny day with no one else around, when you glance down at the clean sidewalk and see a shiny dime. Do you pick it up? If your answer would be “Yes”, would you also pick up a nickel or a penny? If you said “No” to the dime, for what coin denomination would you stop and pick it up? If your original find were two nickels, would that change your answer?

I posed this series of questions to a number of people, and two distinct styles of decision-making emerged.

Sometimes, their decision to stop and pick up the money depended on how much money was there. If they said “No” to the dime, then we would move on to increasingly larger values of cash until they said “Yes”. In such instances, each one of these people had a tipping point – a numeric value at which their answer changed from “No” to “Yes”. Of course, there are other factors, such as multiple coins versus a single coin, for example, that might affect their tipping point. (Someone who would pick up a dime might not bend down to retrieve ten pennies.) Their choice might also change if they were the ones that dropped the money in the first place. However, the key point is that these people were always making a number-based decision. A lower face value lowered the beneficial value of the act itself, resulting in a decision to leave the cash where it was and keep walking. If they came across a sufficiently higher face value, the value of the money and the act of picking it up both increased in direct proportion, and a different choice was made: to stop and pick it up.

While this relationship between monetary value and likelihood of picking up a coin seems simple enough, a near-equal number of friends gave very different responses – saying they would pick up any coin, regardless of the amount. They explained that for them this was not a number-based decision at all, but was related to a personal value: sometimes the joy of finding something for nothing, or a belief in the luck acquired by picking it up, or an aversion to waste, or an attraction to money of any amount. The act of picking up the money had real value to them, which was not necessarily determined by the quantifiable value of the money itself.

This inquiry is not so much about dividing people as dividing behaviours in a specific situation. Of course, if we switch the question from a coin to a bill, then it probably becomes a number-based decision every time for everyone. However, for the original coin example, there is no question that two types of decision-making were used: Some said they based their decision on coin value, some said they didn’t.