Andrew Welch's Blog, page 3

May 11, 2020

Money for Nothing

Readers of my work will know that the core of my studies is number-based values. A key attribute of these values is the absence of any inherent concept of sufficiency - by definition, more is always worth more. Money is the most obvious example of a number-based value, and in the case of our society, money is structured such that the more money one has, the faster one can accumulate even more of it. In other words, significant wealth has a positive feedback loop. The implication for some very fortunate people (in the absence of serious risk-taking) is a lifetime of potential near-guaranteed financial growth. "Lifetime" is the operative word in this case - nature has its own way of limiting the amount of time one has to accumulate and wield financial wealth.

However, there are two exceptions to nature's mortality constraint: corporations and inheritances. I have dealt with the endless growth potential of corporations, perhaps most interestingly in this musing on a theoretical corporate endgame. On the other hand, the concept of inheriting wealth is a new exploration for me, but it should be a significant one. By some estimates, 60% of the wealth in the United States is inherited, and in 2004 one half of the over $200 billion of inherited wealth was attributed to just the top 7% of the estates. (Those numbers have likely become even more concentrated since then.) [Critics of these assumptions often point to the anecdotal evidence of the very wealthiest people. For example, more than half of the world's billionaires are supposedly 'self-made'. But on closer examination, these are (as we might well expect) anomalies - smart privileged men who managed to leverage the pre-existing infrastructure of the global internet to be the first to get their oligopolies out there. Contrast this with the data gathered by researchers like Thomas Piketty, which included all incomes, not just a few outliers at the top.]

The first thing to note is that society has a long held precedent that the assets of parents should naturally(?) be passed on to their children after death. There are several important historical differences at play when considering the applicability of that paradigm to the present day. Lifespans used to be a lot shorter, and social structure was such that your birth lineage determined your social status and position for life. As times have obviously changed, I began to wonder what moral justification could possibly be made for offspring to automatically claim their dead parents' assets. I posed the question to several colleagues, and got a great deal of insightful feedback - possibly because they are of an age where (given today's lifespans) they are both recipients and architects of estate wealth management.

In regards to wealth, the briefest summation of this small survey of diverse and intriguing opinions from an astute and thoughtful circle would be:

A parent can say where they want their assets go (before and after death), but beyond that, a child does not have any moral claim to such wealth.

Parents have a valid biological imperative to offer their child every possible advantage in life.While I recognize the biological impulses, I will go out on a limb and say that I believe the inheritance of massive wealth is a social injustice – power and assets being conveyed to another simple by nature of birth. Extremely large inheritances perpetuate and are key to greatly expanding global wealth inequity, using principles with shaky moral foundations.

We already know that the children of wealthy parents start life with very significant advantages. It also can’t be avoided that rich parents are in the position to give significant gifts of wealth to their kids if they choose. I don’t believe that inheritance rights are the same thing. Yes, of course, if society were able to limit wealth inheritance (say, by dramatically increasing estate taxes), the actual transfer could also be accomplished through gifting before death. However, subtly perhaps, I don’t believe the two transfers are the same, and restricting the first would cause all of society to rethink the second.

One more set of figures might be useful: A 2011 study by Edward Wolff and Maury Gittleman found that the wealthiest 1% of U.S. families had inherited an average of $2.7 million from their parents. (447 times more than those with wealth less than $25,000 had inherited.)

So I challenged myself to come up with a theoretical proposal - not something that would ever likely be implemented under society's current paradigm. Rather, it's an exercise in completing the thoughts surrounding my assertion. If I'm going to question a global precedent, it is only fair that I eventually turn my mind to an alternative that would address the issues raised. Here's one possibility:

To those who would protest that such a system would be 'unfair',

However, there are two exceptions to nature's mortality constraint: corporations and inheritances. I have dealt with the endless growth potential of corporations, perhaps most interestingly in this musing on a theoretical corporate endgame. On the other hand, the concept of inheriting wealth is a new exploration for me, but it should be a significant one. By some estimates, 60% of the wealth in the United States is inherited, and in 2004 one half of the over $200 billion of inherited wealth was attributed to just the top 7% of the estates. (Those numbers have likely become even more concentrated since then.) [Critics of these assumptions often point to the anecdotal evidence of the very wealthiest people. For example, more than half of the world's billionaires are supposedly 'self-made'. But on closer examination, these are (as we might well expect) anomalies - smart privileged men who managed to leverage the pre-existing infrastructure of the global internet to be the first to get their oligopolies out there. Contrast this with the data gathered by researchers like Thomas Piketty, which included all incomes, not just a few outliers at the top.]

The first thing to note is that society has a long held precedent that the assets of parents should naturally(?) be passed on to their children after death. There are several important historical differences at play when considering the applicability of that paradigm to the present day. Lifespans used to be a lot shorter, and social structure was such that your birth lineage determined your social status and position for life. As times have obviously changed, I began to wonder what moral justification could possibly be made for offspring to automatically claim their dead parents' assets. I posed the question to several colleagues, and got a great deal of insightful feedback - possibly because they are of an age where (given today's lifespans) they are both recipients and architects of estate wealth management.

In regards to wealth, the briefest summation of this small survey of diverse and intriguing opinions from an astute and thoughtful circle would be:

A parent can say where they want their assets go (before and after death), but beyond that, a child does not have any moral claim to such wealth.

Parents have a valid biological imperative to offer their child every possible advantage in life.While I recognize the biological impulses, I will go out on a limb and say that I believe the inheritance of massive wealth is a social injustice – power and assets being conveyed to another simple by nature of birth. Extremely large inheritances perpetuate and are key to greatly expanding global wealth inequity, using principles with shaky moral foundations.

We already know that the children of wealthy parents start life with very significant advantages. It also can’t be avoided that rich parents are in the position to give significant gifts of wealth to their kids if they choose. I don’t believe that inheritance rights are the same thing. Yes, of course, if society were able to limit wealth inheritance (say, by dramatically increasing estate taxes), the actual transfer could also be accomplished through gifting before death. However, subtly perhaps, I don’t believe the two transfers are the same, and restricting the first would cause all of society to rethink the second.

One more set of figures might be useful: A 2011 study by Edward Wolff and Maury Gittleman found that the wealthiest 1% of U.S. families had inherited an average of $2.7 million from their parents. (447 times more than those with wealth less than $25,000 had inherited.)

So I challenged myself to come up with a theoretical proposal - not something that would ever likely be implemented under society's current paradigm. Rather, it's an exercise in completing the thoughts surrounding my assertion. If I'm going to question a global precedent, it is only fair that I eventually turn my mind to an alternative that would address the issues raised. Here's one possibility:

Imagine, a system with no estate or inheritance taxes. Instead, estates would only be permitted to bequeath a maximum of $1 million dollars in negotiable assets to any single entity or trust (not including for-profit corporations), and up to an additional $1 million in non-negotiable assets (that were non-negotiable assets at the time of death) to any offspring or dependents. A higher amount could be willed to a charity or other public institution, subject to a review by a standard community board set-up for such reviews.By tossing this thought out there, I realize that there will be many who will find fault with the experiment. And I look forward to hearing from them, so long as their criticism advances the philosophical and ethical objectives. (To begin with the amounts are somewhat arbitrary but should convey the essential intent. Feel free to comment.)

Any entitiy could also be granted right of first refusal on the purchase of specified assets at fair market value.

All surplus funds would be used by the community/public sector to pay for important programs like national healthcare and a Guaranteed Basic Income plan. If this resulted in a surplus of public funds, income tax would be lowered accordingly for all citizens.

Note that, prior to their death, any parent would still be free to gift any asset to anyone, without restriction (although there might have to be some mechanism to review massive gifts transacted within, say, the same window that we use for requests of medically-assisted death when such a death is considered imminent). Beating the 'deadline' by a day or two is obviously cheating!

To those who would protest that such a system would be 'unfair',

...I challenge them to argue for the 'fairness' of the existing system.To those who would protest that such a limitation would be meaningless if unlimited gifting before death were still allowed,

...I say: "Well then, what's the problem?" Personally, as mentioned above, I believe that gifts in-person are NOT the same. Such gifts carry social obligations and also remove wealth from the still-living parent. Time would tell how that dynamic would play out.To those who protest that such a system could never be enforced - that there would be workarounds just as assuredly as there are billionaires with offshore accounts who pay no tax,

...I remind them that, for the sake of this exploration, let's assume that a society could exist where such a system could be realistic and pragmatic, and work from there.Your thoughts?

Published on May 11, 2020 15:00

April 11, 2020

Where Do We Start?

You see this crisis as an opportunity? Great!You got a plan? No? Well I do.

Not too surprisingly, my previous post here was similar in nature to a lot of other posts that are showing up in progressive blogs around the globe, all saying essentially the same thing:

Please, don't kid yourself.

Personal changes to your life will be wonderful. They may bring you happiness and renewed purpose. They may shine new light in your tiny corner of the world. Don't get me wrong - that is awesome! But how are we going to take this opportunity that you see and actually do something with it? What are you actually going to ask your leaders to do that hasn't fallen on deaf ears before? What do you think is really going to happen?

Whether we follow China's timetable and end the lockdown by the end of May or whether it drags on into June or July, when we do get the green light to return to normal, we will sprint for it. The marketing might of every industry on Earth will be pulling us back into their line of thinking with every fibre of their very powerful being. And we'll go back to the old status quo, not because all of us want to, but because we don't know how to fight that. We don't know anything else. The world we want hasn't been done before. We don't know where to begin. This is all unprecedented.

Economic catastrophes, on the other hand, are not unprecedented, and governments have been continually refining how to restore their monetary paradigm. After the economic crisis of 2008, and for the next four years, the U.S. Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, and others started madly creating money out of thin air in order to avert total economic collapse. Multiple trillions of dollars were printed with nothing but a prayer for the return of economic growth for decades into the future to back them. And by their measures, it worked. Meanwhile, the social values got worse. Entire countries suffered austerity measures that they have yet to come out from under, millions more displaced peoples wander the globe seeking refuge from conflict and devastation, and populism has made a mockery of democracy and past advances in social justice and environmental protection.

This may be an opportunity to move forward, but all precedents point to a move backward - a loss of past gains and even deeper entrenchment in maniacally obsessive economic growth. We are nowhere near the end of this crisis and look at what your government has already started. The business bailouts have begun and the pitches have already started to have our economies roaring back sooner rather than later. No-one on the news or in authority ever questions that objective as being what we all want.

On the flip side, those who long for change have no meaningful plan. They are split between environmentalists, social justice seekers, climate change activists, spirituality aficionados, and biodiversity promoters. Everything that they call for threatens jobs and the economy. Yes, that is the point, but that point is lost on those that fear for their lives and understand that jobs and the economy are the keys to their survival. I said it in my previous post, but it's worth saying it again:

Except for One Possibility...

Personally, so far, I see one chance for change. One.

Consider what attributes any real change agent would have to have:

Something that did not directly threaten the status quo paradigm.Something that, at face value, might even look like it would support the old status quo.Something that had been tried already and shown to have success potential.Something that does not immediately lower the corporate bottom line or the power of the super-wealthy.Something that already has support on both ends of the political spectrum.Something that could easily gain broad support from all the people.Something that suited the circumstances.And most importantly...

Something that could start small and had the potential of being a total game changer.To figure out what that might be, I ask you: What holds us back, every time? Pandemics aside, what is our universal everyday fear? What defeats the most progressive decisions of governments the world over? What is the one thing you see touted on every party platform, regardless of where they lie on the political spectrum?

Jobs.

We must have jobs, preserve jobs, create jobs. It's a policy with universal appeal because losing our job is the ubiquitous modern-day fear that the non-wealthy have in this country. What if I lost my income? What if my savings were wiped out? What if I want to retire? And so every single decisive move that any government wants to make gets weighed against the all-important job question because they know that's the deal maker or breaker. So how might we ever escape this paradigm?

With a guaranteed basic income.

I am convinced, more than ever, that a guaranteed basic income (GBI) would be humanity's foot in the door that leads to the change we all want. Free survival removes the survival imperative of having a job. It is our best, most pragmatic, most realistic shot at turning this massive cruise ship around. I see it as a first step towards restoring human values and literally changing our world. Describing that process would take more time than I have in a single blog post. I already posted a case for how a GBI might work in Canada, and what the benefits would be. Perhaps in a later post, I will attempt to extract more from my second book-in-progress so that the pathway can be more comprehensively laid out.

Meanwhile, to all of you who have been reading my posts and others, cheering on the visionary writers, and spreading your hopeful optimism - to all of you who can truly see this tragic pandemic for the huge opportunity that it is - where are you going to start?

Let's throw our collective weight behind something that might actually achieve that brave new world. Demand a federal guaranteed basic income. That's where I think we should start. And start now.

That's my idea. I'd like very much to hear others...

Not too surprisingly, my previous post here was similar in nature to a lot of other posts that are showing up in progressive blogs around the globe, all saying essentially the same thing:

"This could be our best chance for a better world!"It's all very heartwarming and uplifting. It gives us hope for a brighter future while we are trapped in our own homes, unable to socialize, unable to reach out and hug one another, unable to share the joy of being alive in-person with others. A new world is possible!

"During lockdown, the pollution cleared and the birds were singing, showing us the environment that is possible!"

"We've had to lots of time to think about what's important. Now we just have to make that happen!"

Please, don't kid yourself.

Personal changes to your life will be wonderful. They may bring you happiness and renewed purpose. They may shine new light in your tiny corner of the world. Don't get me wrong - that is awesome! But how are we going to take this opportunity that you see and actually do something with it? What are you actually going to ask your leaders to do that hasn't fallen on deaf ears before? What do you think is really going to happen?

Whether we follow China's timetable and end the lockdown by the end of May or whether it drags on into June or July, when we do get the green light to return to normal, we will sprint for it. The marketing might of every industry on Earth will be pulling us back into their line of thinking with every fibre of their very powerful being. And we'll go back to the old status quo, not because all of us want to, but because we don't know how to fight that. We don't know anything else. The world we want hasn't been done before. We don't know where to begin. This is all unprecedented.

Economic catastrophes, on the other hand, are not unprecedented, and governments have been continually refining how to restore their monetary paradigm. After the economic crisis of 2008, and for the next four years, the U.S. Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, and others started madly creating money out of thin air in order to avert total economic collapse. Multiple trillions of dollars were printed with nothing but a prayer for the return of economic growth for decades into the future to back them. And by their measures, it worked. Meanwhile, the social values got worse. Entire countries suffered austerity measures that they have yet to come out from under, millions more displaced peoples wander the globe seeking refuge from conflict and devastation, and populism has made a mockery of democracy and past advances in social justice and environmental protection.

This may be an opportunity to move forward, but all precedents point to a move backward - a loss of past gains and even deeper entrenchment in maniacally obsessive economic growth. We are nowhere near the end of this crisis and look at what your government has already started. The business bailouts have begun and the pitches have already started to have our economies roaring back sooner rather than later. No-one on the news or in authority ever questions that objective as being what we all want.

On the flip side, those who long for change have no meaningful plan. They are split between environmentalists, social justice seekers, climate change activists, spirituality aficionados, and biodiversity promoters. Everything that they call for threatens jobs and the economy. Yes, that is the point, but that point is lost on those that fear for their lives and understand that jobs and the economy are the keys to their survival. I said it in my previous post, but it's worth saying it again:

The bulk of the world will never change its value system until it sees a real benefit in doing so, but the only way to see that benefit is if you are using a different value system.I do not doubt that the scope of this pandemic, the pause effect on our lives, and all those other effects on the common person will have an impact. At best, there will be many more who are drawn to a desire for change. But chances are, the only real outcome will be a slightly higher proportion of the world population being distressed with the direction we're headed in. Climate change and all the other global disasters will be back on track in no time.

Except for One Possibility...

Personally, so far, I see one chance for change. One.

Consider what attributes any real change agent would have to have:

Something that did not directly threaten the status quo paradigm.Something that, at face value, might even look like it would support the old status quo.Something that had been tried already and shown to have success potential.Something that does not immediately lower the corporate bottom line or the power of the super-wealthy.Something that already has support on both ends of the political spectrum.Something that could easily gain broad support from all the people.Something that suited the circumstances.And most importantly...

Something that could start small and had the potential of being a total game changer.To figure out what that might be, I ask you: What holds us back, every time? Pandemics aside, what is our universal everyday fear? What defeats the most progressive decisions of governments the world over? What is the one thing you see touted on every party platform, regardless of where they lie on the political spectrum?

Jobs.

We must have jobs, preserve jobs, create jobs. It's a policy with universal appeal because losing our job is the ubiquitous modern-day fear that the non-wealthy have in this country. What if I lost my income? What if my savings were wiped out? What if I want to retire? And so every single decisive move that any government wants to make gets weighed against the all-important job question because they know that's the deal maker or breaker. So how might we ever escape this paradigm?

With a guaranteed basic income.

I am convinced, more than ever, that a guaranteed basic income (GBI) would be humanity's foot in the door that leads to the change we all want. Free survival removes the survival imperative of having a job. It is our best, most pragmatic, most realistic shot at turning this massive cruise ship around. I see it as a first step towards restoring human values and literally changing our world. Describing that process would take more time than I have in a single blog post. I already posted a case for how a GBI might work in Canada, and what the benefits would be. Perhaps in a later post, I will attempt to extract more from my second book-in-progress so that the pathway can be more comprehensively laid out.

Meanwhile, to all of you who have been reading my posts and others, cheering on the visionary writers, and spreading your hopeful optimism - to all of you who can truly see this tragic pandemic for the huge opportunity that it is - where are you going to start?

Let's throw our collective weight behind something that might actually achieve that brave new world. Demand a federal guaranteed basic income. That's where I think we should start. And start now.

That's my idea. I'd like very much to hear others...

Published on April 11, 2020 17:58

April 7, 2020

Lest We Forget

"We can't return to normal, because the normal that we

had was precisely the problem." – spray-painted on a wall in Hong Kong

On September 11, 2001, a group of terrorists launched four coordinated attacks in the United States, using commercial aircraft as weapons. We later learned that two strategic objectives of the attacks were to goad the United States into initiating conflicts in the Middle East, and the diversion and depletion of the American economy (although the second goal was paradoxically defeated by the first – war on foreign soil is always good for business).

However, there was another impact, felt all over the world: a unilaterally drop in civil liberties (and common sense). For example, for the last two decades, we have all paid the enormous price for continually enhanced screening measures in airports the world over, and air travellers have wasted untold hours in line ups and suffered the frustration and costs of denied items. Why? One lesson learned on that September morning was that aircraft pose a unique threat. If terrorists can take control of an aircraft, or get explosives on-board, the potential loss of life extends well beyond that of the passengers, and the images of destruction will haunt generations. So you make the cockpits secure and you screen for bombs, right?

What does that have to do with scissors or pocket knives or knitting needles? How could a person possibly inflict more damage with those on a aircraft than they could on a train or bus or subway? Why is a drill bit a lethal weapon but a heavy metal ballpoint pen isn't? Why does the word "knife" make one-third of plastic cutlery inadmissible? Why was my masking tape confiscated (as a possible hand-binding item) but my computer mouse with the 6-foot wire cord was not? (True story.) When will we learn that humans in general are appallingly bad at the simple math of risk assessment in any aspect of their lives? And when do we realize that even the supposed security experts are mainly putting on a charade, as if all terrorists had the imagination of a carpet tack.

There is nothing new in any of the foregoing – we've ranted about it for years. And this only considers one tiny aspect of the significant changes to our civil liberties and social well-being. But it tells a phenomenally important story about what we are about to face...

Plenty of people are asking when this CoViD-19 pandemic will all be over. That depends on your perspective. The 9-11 attacks were over in a matter of hours, and yet it has been more than 18 years and the 9-11 attacks still show no signs of ending any time soon. Sadly, I think it very likely that we will be pressured to make exactly the same mistakes all over again.

Pandemic MiseryThis pandemic is not just a freak of nature. New viruses wink in and out of existence all the time. If they happen to get the perfect chemistry going, they can become virulent and deadly to humans, but that's only a small part of the story. Pandemics can only spread using the channels that we explicitly create for their transmission. We carve those grooves into the social landscape, and the virus simply flows along the lines that we have been establishing over decades. For cholera and typhoid, it was crowded urban centres with inadequate sanitation. For HIV/AIDS it was unprotected sex and unsafe practices in the use of illicit intravenous drugs. For something as large and widespread as CoViD-19 the grooves had to be deep and extensive. Here's a diverse selection of those factors required in order to achieve the resulting human misery, with more coming to light each day:

Conditions like those found in live wild animal markets where viral mutations can effectively transition between species.Staggeringly important decisions made, based on economics, not medicine.Millions of people rapidly crisscrossing the globe by air.A scarcity-equals-value mindset that, combined with selfishness, leads to hoarding, even of items that are non-essential.Ongoing trade wars and conflicts being fought with crushing sanctions.Divided populations who treat everything as a partisan issue.Longstanding and continual governments cuts to healthcare, emergency planning, scientific research, and social safety nets.Small regions that create more than half of the world's supply of critical items, such as face masks (Hubei province, China) and nasopharyngeal swabs (Lombardy, Italy).Politicians with zero credibility.Ubiquitous tools for anyone to spread misinformation, panic, and propaganda.The marginalization of bottom-tier labour that (it turns out) is essential to our survival.Treating the movement of medical essentials as a commercial supply chain.Generations of people '(re-)educated' to dispute scientific evidence.Popular crisis reactions being hoarding, price gouging, and scams to steal money.Emergency plans that focus on economic bailouts as opposed to humanitarian imperatives.Complacency or denial surrounding issues that pose a threat to our species or others.A near total absence of community resiliency and self-sufficiency.Huge populations unable to access clean water for washing because international aid was conditional on water resources being privatized.Governments motivated and willing to repress information and/or deny reality.Concentrations of vulnerable populations in places like long-term care homes and slums.The obsessive pursuit of 'economic efficiency' to the detriment of back-up redundancy and resilience.Each and every one of these characteristics of our twenty-first century world had (and is having) a direct impact on whether or not a pandemic occurred, how many would die, and how we are all affected. The question, then, is not "When will this all be over?" The question is "How many of those factors do we wish to retain as part of the brand new status quo?", for there is absolutely no question that, even more than the legacy of the September 11th attacks, a clear delineation will been made between the world of before and the world after. Our societal norms and value systems are going to change. Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that they are going to be changed – intentionally.

Indeed, they already have been, which leads us to an even more immediate consideration. In The Shock Doctrine, Naomi Klein compellingly documents how states and powerful economic players have taken advantage of (or even facilitated) significant social, political, and economic crises in order to impose profound structural changes on populations who are initially in a state of total shock. Emergency powers are created or invoked for the temporary management of the crisis, but once in place, those powers never quite completely disappear. Laws are rewritten. Neighbourhoods levelled by war or natural disasters are seized and/or transferred to well-connected developers for pennies. Once again, there is a very real concern for the resurgence of what Klein calls disaster capitalism, especially as projections for the timeline of our current crisis grow ever longer. To make things even more dangerous, the present conditions make effective discussion, court challenges, and debate of their implications impossible.

It is not just nefarious changes that we have to be fearful of. As the weeks of self-isolation and emergency coping turn into months, we will unquestionably be forming new habits of our own. (A study by Phillippa Lally at University College London showed that, while a new habit took anywhere from 18 to 254 days to become automatic, the average was 66 days.) When we emerge from sheltering-in-place, I think we'll soon return to shaking hands – it is the kind of contact we have been craving, but replacement habits such as inflated social media time, online entertainment, videoconferencing, and moderate physical distancing may not be fading quite so quickly. How soon will the new Plexiglas barriers at grocery checkouts be coming down? I suspect they'll still be there long past their pragmatic relevance.

So, while the experts seek a vaccine or treatment, it makes sense for the rest of us to take a serious look not at the SARS-CoV-2 virus as much as the context for the whole pandemic and everything that was wrong with our approach to life long before it struck. I like the way visionary author Charles Eisenstein puts it: When your goldfish gets sick, do you attempt to treat the fish or do you clean the long-neglected tank?

Brave New World?It did not take long for some hopeful progressives to see this crisis as an opportunity. As someone who devotes a lot of time to thinking and writing about value systems, I'm definitely one of those people. Consider: I proposed in The Value Crisis that humankind places far too much emphasis on values measured by number – those being values where more is always worth more. They have no built-in sufficiency and thus lead to obsessions with impossible maximization. Such values now consistently trump non-numeric values such as happiness, justice, beauty, compassion, and so on. (You might note that most of the pandemic-misery factors I listed above can be derived directly from number-based values related to economic growth, profit maximization, dismissing ecological concerns, etc.) But there's a Catch-22 conundrum:

The desire to return to the old incumbent socioeconomic paradigm will have powerful leadership, momentum, and broad support. The previous status quo will be the well-defined default, and life, in general, abhors change. It is only if the changes imposed by the crisis itself are profound enough (and, sadly, devastating enough) that the opportunity for the acceptance of a new paradigm will open up. Lasting changes to the way we manage our economies, for example, will require new policies and new legislation. Such retooling is going to need much longer than a single term of government to achieve, and as such, it's going to need constant and extended support from the electorate.

In March 2020, one week before the pandemic reached Canadian shores, I had just submitted the first complete draft of a second book to my editor. The objective of that new work was to propose concrete actions to promote human (i.e. non-numeric) values in one's individual life, and to share alternatives to number-based social paradigms in general. It's not that we don't understand qualitative human values – of course we do! The problem is that they are consistently trumped by quantitative values. My first goal, then, was to encourage individual readers to experiment with all kinds of actions that would allow them to enjoy the benefits of thinking differently – to restore some balance in our choices of which value systems take precedence in different aspects of their lives. My second goal was to show that, while the current collective systems will often try to devalue such actions or make them appear irrational, there are also fully pragmatic societal solutions that would respect such values at the community and state level.

In other words, I wanted to show that you can experience true joy by easily acting more intentionally on human values, and that there are plausible economic adjustments for society that would actually work to embrace those same values for all. The idea is not to replace one value system for another – it is to restore a balance so that one does not consistently override the other. We need both number-based and qualitative values to function in this world!

My hope at the time was that individuals, families, and small communities could conceivably transition in small pockets, and there might be a growing familiarity with societal alternatives, should the opportunity ever arise. I never expected that the potential for that opportunity might appear within a week of my manuscript being completed and submitted! Not surprisingly, that work is now being redrafted to reflect some of the new context – a non-trivial exercise, since the context itself continues to change.

A Dire WarningThere will be enormous pressure, both from within ourselves and from the world's most powerful players to restore as much of the past status quo as possible when this pandemic subsides. The only changes the privileged few will want to see are those that even further enhance the ability of the old value system to trump the new one. The obsessive pursuit of power through financial wealth and devastation perpetrated in the impossible pursuit of continued economic growth will continue to take precedence over sustainability, happiness, justice, compassion, giving, collaboration, creativity, spirituality, and all those other values with no price tag. Those old values were already hurtling us towards global inequity, biodiversity extinction, climate change, environmental destruction, economic collapses, and more. We now have an even clearer picture of the before, the effect, and the possible after.

As many of us sit at home in isolation, considering our own mortality and what's really important, and looking out the window at the world we are leaving for our children, there are some among us who will wisely take some of that time to rethink our values. They will seethe with anger at the way some leaders and industries are showing their true colours – and beam with pride for others. They will begin to read about previously marginalized 'radical' ideas like Guaranteed Basic Incomes and the like. They will look at grocery store workers and hospital cleaners differently. They will feel the visceral connection to those in their community desperate to show compassion, and the contrasting gut reaction to those out to profit from despair. They will regret the untold extra hours they had previously discarded to work and pursuit of wealth instead of being with family and friends. They will begin to envision how things might be different.

But wishing for a new world will be like wishing for their evening meal – it won't make itself. The odds are overwhelmingly not in our favour. We have to talk about this. We have to be open to change and actively explore new ideas. We have to live our own lives a little differently, as well as standing up and calling for new paradigms for our communities and nations.

Lest we forget.

had was precisely the problem." – spray-painted on a wall in Hong Kong

On September 11, 2001, a group of terrorists launched four coordinated attacks in the United States, using commercial aircraft as weapons. We later learned that two strategic objectives of the attacks were to goad the United States into initiating conflicts in the Middle East, and the diversion and depletion of the American economy (although the second goal was paradoxically defeated by the first – war on foreign soil is always good for business).

However, there was another impact, felt all over the world: a unilaterally drop in civil liberties (and common sense). For example, for the last two decades, we have all paid the enormous price for continually enhanced screening measures in airports the world over, and air travellers have wasted untold hours in line ups and suffered the frustration and costs of denied items. Why? One lesson learned on that September morning was that aircraft pose a unique threat. If terrorists can take control of an aircraft, or get explosives on-board, the potential loss of life extends well beyond that of the passengers, and the images of destruction will haunt generations. So you make the cockpits secure and you screen for bombs, right?

What does that have to do with scissors or pocket knives or knitting needles? How could a person possibly inflict more damage with those on a aircraft than they could on a train or bus or subway? Why is a drill bit a lethal weapon but a heavy metal ballpoint pen isn't? Why does the word "knife" make one-third of plastic cutlery inadmissible? Why was my masking tape confiscated (as a possible hand-binding item) but my computer mouse with the 6-foot wire cord was not? (True story.) When will we learn that humans in general are appallingly bad at the simple math of risk assessment in any aspect of their lives? And when do we realize that even the supposed security experts are mainly putting on a charade, as if all terrorists had the imagination of a carpet tack.

There is nothing new in any of the foregoing – we've ranted about it for years. And this only considers one tiny aspect of the significant changes to our civil liberties and social well-being. But it tells a phenomenally important story about what we are about to face...

Plenty of people are asking when this CoViD-19 pandemic will all be over. That depends on your perspective. The 9-11 attacks were over in a matter of hours, and yet it has been more than 18 years and the 9-11 attacks still show no signs of ending any time soon. Sadly, I think it very likely that we will be pressured to make exactly the same mistakes all over again.

Pandemic MiseryThis pandemic is not just a freak of nature. New viruses wink in and out of existence all the time. If they happen to get the perfect chemistry going, they can become virulent and deadly to humans, but that's only a small part of the story. Pandemics can only spread using the channels that we explicitly create for their transmission. We carve those grooves into the social landscape, and the virus simply flows along the lines that we have been establishing over decades. For cholera and typhoid, it was crowded urban centres with inadequate sanitation. For HIV/AIDS it was unprotected sex and unsafe practices in the use of illicit intravenous drugs. For something as large and widespread as CoViD-19 the grooves had to be deep and extensive. Here's a diverse selection of those factors required in order to achieve the resulting human misery, with more coming to light each day:

Conditions like those found in live wild animal markets where viral mutations can effectively transition between species.Staggeringly important decisions made, based on economics, not medicine.Millions of people rapidly crisscrossing the globe by air.A scarcity-equals-value mindset that, combined with selfishness, leads to hoarding, even of items that are non-essential.Ongoing trade wars and conflicts being fought with crushing sanctions.Divided populations who treat everything as a partisan issue.Longstanding and continual governments cuts to healthcare, emergency planning, scientific research, and social safety nets.Small regions that create more than half of the world's supply of critical items, such as face masks (Hubei province, China) and nasopharyngeal swabs (Lombardy, Italy).Politicians with zero credibility.Ubiquitous tools for anyone to spread misinformation, panic, and propaganda.The marginalization of bottom-tier labour that (it turns out) is essential to our survival.Treating the movement of medical essentials as a commercial supply chain.Generations of people '(re-)educated' to dispute scientific evidence.Popular crisis reactions being hoarding, price gouging, and scams to steal money.Emergency plans that focus on economic bailouts as opposed to humanitarian imperatives.Complacency or denial surrounding issues that pose a threat to our species or others.A near total absence of community resiliency and self-sufficiency.Huge populations unable to access clean water for washing because international aid was conditional on water resources being privatized.Governments motivated and willing to repress information and/or deny reality.Concentrations of vulnerable populations in places like long-term care homes and slums.The obsessive pursuit of 'economic efficiency' to the detriment of back-up redundancy and resilience.Each and every one of these characteristics of our twenty-first century world had (and is having) a direct impact on whether or not a pandemic occurred, how many would die, and how we are all affected. The question, then, is not "When will this all be over?" The question is "How many of those factors do we wish to retain as part of the brand new status quo?", for there is absolutely no question that, even more than the legacy of the September 11th attacks, a clear delineation will been made between the world of before and the world after. Our societal norms and value systems are going to change. Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that they are going to be changed – intentionally.

Indeed, they already have been, which leads us to an even more immediate consideration. In The Shock Doctrine, Naomi Klein compellingly documents how states and powerful economic players have taken advantage of (or even facilitated) significant social, political, and economic crises in order to impose profound structural changes on populations who are initially in a state of total shock. Emergency powers are created or invoked for the temporary management of the crisis, but once in place, those powers never quite completely disappear. Laws are rewritten. Neighbourhoods levelled by war or natural disasters are seized and/or transferred to well-connected developers for pennies. Once again, there is a very real concern for the resurgence of what Klein calls disaster capitalism, especially as projections for the timeline of our current crisis grow ever longer. To make things even more dangerous, the present conditions make effective discussion, court challenges, and debate of their implications impossible.

It is not just nefarious changes that we have to be fearful of. As the weeks of self-isolation and emergency coping turn into months, we will unquestionably be forming new habits of our own. (A study by Phillippa Lally at University College London showed that, while a new habit took anywhere from 18 to 254 days to become automatic, the average was 66 days.) When we emerge from sheltering-in-place, I think we'll soon return to shaking hands – it is the kind of contact we have been craving, but replacement habits such as inflated social media time, online entertainment, videoconferencing, and moderate physical distancing may not be fading quite so quickly. How soon will the new Plexiglas barriers at grocery checkouts be coming down? I suspect they'll still be there long past their pragmatic relevance.

So, while the experts seek a vaccine or treatment, it makes sense for the rest of us to take a serious look not at the SARS-CoV-2 virus as much as the context for the whole pandemic and everything that was wrong with our approach to life long before it struck. I like the way visionary author Charles Eisenstein puts it: When your goldfish gets sick, do you attempt to treat the fish or do you clean the long-neglected tank?

Brave New World?It did not take long for some hopeful progressives to see this crisis as an opportunity. As someone who devotes a lot of time to thinking and writing about value systems, I'm definitely one of those people. Consider: I proposed in The Value Crisis that humankind places far too much emphasis on values measured by number – those being values where more is always worth more. They have no built-in sufficiency and thus lead to obsessions with impossible maximization. Such values now consistently trump non-numeric values such as happiness, justice, beauty, compassion, and so on. (You might note that most of the pandemic-misery factors I listed above can be derived directly from number-based values related to economic growth, profit maximization, dismissing ecological concerns, etc.) But there's a Catch-22 conundrum:

The bulk of the world will never change its value system until it sees a real benefit in doing so, but the only way to see that benefit is if you are using a different value system.In other words, one point of view says that real change can only come when the existing value system fails (and fails catastrophically). Many assumed that climate change would be that alarm bell. Could the natural world be giving us yet another wake-up call (with no snooze button this time)?

The desire to return to the old incumbent socioeconomic paradigm will have powerful leadership, momentum, and broad support. The previous status quo will be the well-defined default, and life, in general, abhors change. It is only if the changes imposed by the crisis itself are profound enough (and, sadly, devastating enough) that the opportunity for the acceptance of a new paradigm will open up. Lasting changes to the way we manage our economies, for example, will require new policies and new legislation. Such retooling is going to need much longer than a single term of government to achieve, and as such, it's going to need constant and extended support from the electorate.

In March 2020, one week before the pandemic reached Canadian shores, I had just submitted the first complete draft of a second book to my editor. The objective of that new work was to propose concrete actions to promote human (i.e. non-numeric) values in one's individual life, and to share alternatives to number-based social paradigms in general. It's not that we don't understand qualitative human values – of course we do! The problem is that they are consistently trumped by quantitative values. My first goal, then, was to encourage individual readers to experiment with all kinds of actions that would allow them to enjoy the benefits of thinking differently – to restore some balance in our choices of which value systems take precedence in different aspects of their lives. My second goal was to show that, while the current collective systems will often try to devalue such actions or make them appear irrational, there are also fully pragmatic societal solutions that would respect such values at the community and state level.

In other words, I wanted to show that you can experience true joy by easily acting more intentionally on human values, and that there are plausible economic adjustments for society that would actually work to embrace those same values for all. The idea is not to replace one value system for another – it is to restore a balance so that one does not consistently override the other. We need both number-based and qualitative values to function in this world!

My hope at the time was that individuals, families, and small communities could conceivably transition in small pockets, and there might be a growing familiarity with societal alternatives, should the opportunity ever arise. I never expected that the potential for that opportunity might appear within a week of my manuscript being completed and submitted! Not surprisingly, that work is now being redrafted to reflect some of the new context – a non-trivial exercise, since the context itself continues to change.

A Dire WarningThere will be enormous pressure, both from within ourselves and from the world's most powerful players to restore as much of the past status quo as possible when this pandemic subsides. The only changes the privileged few will want to see are those that even further enhance the ability of the old value system to trump the new one. The obsessive pursuit of power through financial wealth and devastation perpetrated in the impossible pursuit of continued economic growth will continue to take precedence over sustainability, happiness, justice, compassion, giving, collaboration, creativity, spirituality, and all those other values with no price tag. Those old values were already hurtling us towards global inequity, biodiversity extinction, climate change, environmental destruction, economic collapses, and more. We now have an even clearer picture of the before, the effect, and the possible after.

As many of us sit at home in isolation, considering our own mortality and what's really important, and looking out the window at the world we are leaving for our children, there are some among us who will wisely take some of that time to rethink our values. They will seethe with anger at the way some leaders and industries are showing their true colours – and beam with pride for others. They will begin to read about previously marginalized 'radical' ideas like Guaranteed Basic Incomes and the like. They will look at grocery store workers and hospital cleaners differently. They will feel the visceral connection to those in their community desperate to show compassion, and the contrasting gut reaction to those out to profit from despair. They will regret the untold extra hours they had previously discarded to work and pursuit of wealth instead of being with family and friends. They will begin to envision how things might be different.

But wishing for a new world will be like wishing for their evening meal – it won't make itself. The odds are overwhelmingly not in our favour. We have to talk about this. We have to be open to change and actively explore new ideas. We have to live our own lives a little differently, as well as standing up and calling for new paradigms for our communities and nations.

Lest we forget.

Published on April 07, 2020 14:21

April 2, 2020

Free Survival

The Concise Case for a Guaranteed Basic Income in Canada

Installing a floor in a house with no ceiling.

Imagine you lived in a country where every permanent resident was guaranteed a basic income that provided for the barest essentials of life. Don’t question where the money will come from – we’ll get to that in a moment. Simply imagine that the poorest people in the land each received, say, $1000 every month, no questions asked. How would that country be changed?

Now imagine a contrasting scenario, where you live in a country that has no universal single-payer health insurance. (Canadians can easily observe such an example below our southern border.) What would happen if you slipped and badly broke a bone, or got a viral infection during a global pandemic, or had a child who needed urgent care, and you could not afford to pay for a doctor or a hospital visit or an essential operation? Would any Canadian ever want to go back to the days before 1962 when that was actually the case?

If you are still having trouble with imagining the first scenario, but are all in favour of universal healthcare, ask yourself why medical treatment should be free but essential survival should not be. Canadians don’t apply to be accepted to a hospital when they are sick – they are simply taken in and treated. So why should a homeless person get free food and shelter from their government when they are in a hospital, but not outside of one? How did creating wealth for someone else (i.e. a job) become a prerequisite for life?

The Status QuoLike most wealthy countries, Canada generally offers social assistance – welfare – to those who apply for it and meet the eligibility criteria. We don’t like to see people starving on our streets. In poorer countries, such people might turn exclusively to begging in order to survive. As a society, we don’t tend to hold welfare recipients or beggars in very high regard. For those of us not fortunate enough to inherit our wealth, we have to work to earn a living, and it’s a bit irksome to see welfare money (our tax dollars) going to those who seemingly don’t.

While being on welfare and begging can certainly have a similar feel and stigma, the differences between the two are not all one-sided. Social assistance is perhaps more predictable and has a less visible indignity, but at least if one works harder at begging, one can potentially earn more money. Most welfare programs, on the other hand, are set up such that if you attempt to better your lot by getting work, every dollar that you earn is subtracted from your assistance cheque. That’s a tax rate of 100% on our lowest income earners. Indeed, there are some scenarios in which one or more part-time minimum-wage jobs might actually take the overall household income below the welfare payment level, discouraging recipients from even trying.

A guaranteed basic income (GBI) is different. It is a commitment from the Government of Canada that no-one will be denied the chance to live. It would be available to every adult citizen and permanent resident, linked to their social insurance number (SIN), and paid every month. Every Canadian would receive the same amount, regardless of what province they live in or how much they earn. If a recipient earns more than a defined threshold in any given year, the excess could be taken back at tax time. Anyone can opt in or out at any time.

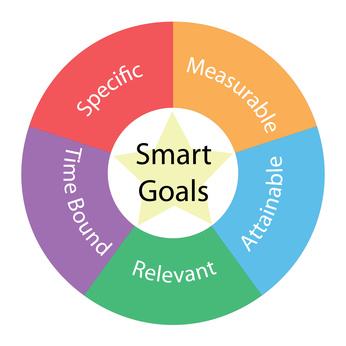

The remainder of this work will be devoted to answering the following questions:

Has this ever been tried anywhere?What are the benefits of a GBI?Wouldn’t people stop working?What are the social costs of a GBI?Where will the money come from?Where else might the money come from?Isn’t a GBI total socialism?Why does anyone deserve a GBI?Where could this lead?

Has this ever been tried anywhere?Absolutely. Minimum income schemes are not just pipe dreams. In the last 50 years there have been more than 30 such programs introduced on an experimental basis around the world – with very promising results. In Canada, a pilot project in Dauphin, Manitoba was conducted in the mid-70s, and in three communities in Ontario (2017-19). Around the same time, another guaranteed basic income program was tried in Finland. Furthermore, at the time of writing, there is an all-party committee putting together the plan for a province-wide pilot program in Prince Edward Island, and a separate commission of inquiry looking at basic income programs for British Columbia. We’ll examine some of their results in the responses to more questions below, but generally speaking, the outcomes have been overwhelmingly positive, and fiscally responsible.

What are the benefits of a GBI? The straightforward benefits in terms of poverty reduction should be obvious. If someone has a guaranteed basic income every month, regardless of other circumstances, at least they have a fighting chance. Poverty is not caused by a moral failing, or a shortage of will, or a lack of character. Poverty is not a mindset, or a choice, or laziness. Poverty is caused by having insufficient funds. Period.

Money doesn’t solve everything. But the benefits of having a guaranteed basic income go far beyond the bank account and dinner table. Where GBI pilot projects have been run, the improvements to social well-being were irrefutable. Generally speaking, the physical and mental health outcomes of participants improved, education and graduation rates went up, and negative encounters with the law went down.

New mothers have more options; youth have more options; the homeless have more options; former inmates trying to rebuild their lives from scratch have more options; people stuck in dead-end jobs have more options. Artists and entrepreneurs can survive while pursuing their dreams and making our world a better place. While one person’s GBI might not pay the full rent in some cities, recipients can band together and pool their resources.

Those in need can get immediate assistance, with their dignity intact – no applications, no assessments, no ongoing administration. When there is no longer a need for soup kitchens and food banks, charitable giving can then be redirected to other worthy causes.

The simplicity and summary benefits of a GBI have yet another significant benefit. Most of us (certainly in prosperous nations with insurance safety nets) now live without the daily fear of being attacked by a predatory animal, or succumbing to a minor natural catastrophe, or being killed by a rival tribe group, or losing everything in a fire, or suffering a medical trauma. What fear could nearly universally apply to anyone in today’s society (pandemics aside)? Unemployment. Losing it all. Not having the money to live in the manner to which one has become accustomed. Not having the savings to retire from a life of labour. It’s a serious fear. (Yes, there was the CoViD-19 pandemic. And what did the Canadian government do? Did its bail-out package save the people? No. It attempted to save pre-existing workers and the economy. The concern was not feeding the population – it was saving the jobs! Those who were already vulnerable got nothing.) Knowing that there is a guaranteed secondary safety net, even if savings and friends are no longer able to help, means a huge stress point is alleviated for every single Canadian.

Speaking of pandemics, imagine what would have happened if a GBI program had already been in place when that global crisis occurred. The back-up system would have been well-defined and ready to go. The universal income amount could have been tweaked as necessary, and all non-essential workers could have immediately gone home to ride it out.

Wouldn’t people stop working?A GBI is no free ride. On the contrary, it provides the bare minimum needed for survival. It just moves the starting line up for people trying to lift themselves out of abject poverty. It’s also the backup safety system that many need for taking new risks and exploring new opportunities; getting the education that truly appeals to them; weathering a sudden personal disaster; taking the time to find a vocation that is a great fit for their talents and interests. Humans do not want to be idle all their life. If they are given the keys to the many doors of opportunity standing before them, they at least have a chance to starting opening them and to better themselves.

A basic minimum income would not pay for a standard of living that anyone would choose for themselves. If you want a nice place to live, internet access, a car, a cell phone, nice clothes, and all the other great things that many of us enjoy in Canada, you are absolutely going to need a job. For example, if the GBI were $1000/month, nobody is going to choose to live on $12,000 per year. (But it might just save your life if that’s all you had.)

This conclusion is borne out by the GBI pilot projects which consistently demonstrate that there was no inclination for participants to work less. Notable exceptions were new parents who chose to spend longer periods out of the workforce to be with their babies, and youth who chose to further their education instead of taking the first job that they could find. The collective benefits of both of those types of decisions are clear.

Moreover, as mentioned earlier, some of the present traditional social assistance programs do actually discourage people from working – especially those with dollar-for-dollar claw backs. A properly-designed GBI does not work that way, and would not have the same effect. However, it does open up alternatives so that the most disadvantaged are not slaves to demeaning sweat labour just to survive another day.

What are the social costs of a GBI?One very sad criticism of GBIs is that the money will simply be wasted by the recipients. This is of course nonsense. The people living at the bottom of our social pyramid are the ones most likely to know what they need to survive. Indeed, they are probably in a better position to make those decisions than some government bureaucrat designing a social assistance program in a committee room somewhere. The flexibility of a GBI gives people the dignity and options to make the choices that are right for their individual circumstances.

The other thing you will hear is that a GBI will simply be used to enable addictions such as alcohol, drugs, and gambling. This kind of distorted thinking is ridiculously biased and narrow. Addictive behaviours can be found at every income level of society. These problems are by no means limited to the poor or marginalized people, nor would they be attributes of the vast majority of those that need financial assistance. Our mental health system should be focussed on treating these addictions, wherever they show up in our communities, not on treating the despair and anguish of poverty.

Furthermore, studies show that even those with addictions do not view such income as something to spend on their unhealthy habits. On the contrary, knowing that such an ongoing benefit could (and likely will) turn their life around, they take the opportunity to improve their well-being and live better lives. Many addictive behaviours are born of despair for any hope for the future. A GBI can supply that missing hope.

Another argument is that a GBI will make people dependent on the government for their survival. This is far more likely an outcome of the existing welfare systems that pay supplements well below the poverty line, thereby keeping people in poverty. Even for those rare cases where, for whatever reason, an individual is not able to capitalize on all of the benefits listed earlier and is forced to continue to rely on their GBI payments in order to live – is there really anything wrong with that? Plenty of average citizens have exactly the same dependence on our universal healthcare system. If you can’t fall back on the basic humanity of your country, what hope is there?

Where will the money come from?While this might be the most obvious question to pose, I saved it until now because some of the responses to the earlier questions set the stage for this one. The answer must also be prefaced with the fact that while we can fairly easily calculate the costs of a GBI program, there are likely to be even more indirect financial benefits than have already been confirmed by pilot programs. This is because a GBI inspires profound longer-term changes to society itself as well as individual well-being.

To begin with, there is the money from existing programs that would no longer be needed. A GBI can replace social assistance, income supplements, tax incentives, subsidies, and more. These kinds of savings include not just their outputs but also the costs associated with managing their applications, assessments, and ongoing administration. Under at least one proposed GBI implementation, these federal and provincial savings alone would cover 60% of the direct costs.

Then there are the secondary savings that have always gone hand-in-hand with real poverty reduction: reduced healthcare costs, lower crime rates, reductions in serious family conflict, etc., all of which otherwise represent a significant burden on the government coffers.

Even after all of that, will a GBI be a net-zero cost program? Probably not. However, any net cost would arguably be an effective investment in universally raising the quality of life for every Canadian, whether getting the GBI or not, because of an overall improvement in the well-being of our communities.

Where else might the money come from?Unsurprisingly, critics of GBI and similar programs immediately translate such proposals into a massive tax increase. Why, they ask, should we be working hard and paying taxes so that it can be given away to the people at the bottom layer of society? Since the implementation of a GBI might very well entail some changes to the distribution of the tax burden, those are valid questions to consider.

And yet, would it not make even more sense to ask why that same majority should be working hard and paying taxes, while some of the highest income earners in the land work complex loopholes, finagle trusts, hide income off-shore, and generally leverage their existing wealth to generate new wealth for themselves at a rate that most could not begin to imagine? While it is extremely important for society to address poverty, it is equally important to address income inequity as those gaps widen ever further. So yes, I think it safe to assume that the introduction of a universal GBI for Canadians is also going to involve some of the country’s wealthiest individuals and corporations paying taxes that more closely reflect their actual earnings.

That being said, it is also true that putting more money into the hands of more people also clearly leads to more economic growth. If the poorest people in Canada can suddenly afford more food and other essentials, that buying power translates directly into a healthier economy. That means more revenue overall to help pay for the GBI that made it all happen. As prosperity grows, the demands on the GBI actually decrease. (By contrast, under the status quo, poverty is self-replicating – it reinforces its own permanence.)

Isn’t a GBI total socialism?Technically, no it isn’t and I’ll say why. But before I do, dismissing an initiative that has the proven benefits outlined above, just because of its apparent political genre is the kind of closed-minded thinking that can hold back an entire nation. Unfortunately, it is also the most common form of knee-jerk criticism when a GBI is debated in the general population.

Socialism, in the literal sense, is where the means of production, distribution, and exchange is owned and/or regulated by the community – none of which are really attributes of a GBI. However, in common usage, the term “socialism” is often applied whenever the government is seen to be giving something away. Universal healthcare, which the vast majority of Canadians support wholeheartedly, is closer to socialism, since the government does indeed define what healthcare is offered and control how it is delivered.

The existing social assistance programs are also closer to socialism than a GBI, since they are much more tightly regulated by the governments administering them. It might surprise those on the right of the political spectrum to know that there is significant support among conservatives for GBI initiatives. Even Milton Friedman, that great champion of neoclassic economics and libertarianism, was a supporter of minimum basic income programs (which he called a “negative income tax”). Such programs appealed to him because it put the money and spending decisions in the hands of the people, not a central planning authority (and as such, were the opposite of socialism). It is also worth noting that the recent three-year GBI pilot program introduced in Ontario in 2017 had the explicit support of all three major parties, and was in fact designed by a long-standing Conservative, former senator Hugh Segal.

Why does anyone deserve a GBI?There are several ethical arguments for a national GBI. Here are a few:

Firstly, for the same reason that you deserve free healthcare. In a country of so much abundance, the essentials of life should be provided to those with no other option. A GBI offers survival with dignity, so that every person has a chance to become a contributing member of society. The status quo does nothing to eradicate poverty – it simply keeps people there. That is not the objective of society or humanity. You might be lucky enough to not have to sleep on the street, but how does it feel to you when you see others forced to do that? Everyone benefits when the lowest point of society is lifted.

Secondly, ask yourself: What is the source of any other money in our present economy? A large percentage of it comes from the real wealth of the nation – its natural resources, its sustainable energy sources, its collective technological know-how, and its broadly held culture and stories. These are things that arguably every resident has equal claim to, so why shouldn’t everyone receive a dividend from this wealth? Putting it another way, ask yourself why those few super-wealthy people who presently take significant wealth from such common national resources deserve to do so.

Thirdly, we must never forget that a GBI applies to everyone, regardless of upbringing, social status, or former income level. It does not just rewrite the future prospects of our most vulnerable and disadvantaged populations; it also completely changes the way each and every one of us think about our own job security and our freedom to make choices that are right for us. A GBI is there for everyone, and anyone can activate that safety net, if and when they need it. This includes middle-income people with no savings fleeing domestic violence. It includes victims of natural disasters or fraud who have lost everything. It includes the disillusioned elite who need some time to redefine their life’s purpose. It includes visionaries who choose voluntary simplicity and a life of volunteerism to help their fellow human beings. A GBI changes the entire paradigm.

Where could this lead?Already, a guaranteed basic income is a better solution for ‘current’ times. It can be designed to provide a fiscally and socially responsible way to provide more effective help for those in need under the economic paradigm that we have lived under for decades. But it can also be a total game changer, ushering in a whole new economic paradigm.

As we live today, survival is largely predicated on wages. We exist in the relentless pursuit of money, a number-based value that has no concept of sufficiency. More is always worth more. The universal objective becomes the maximization of wealth, when the horrible truth is that wealth cannot be maximized – we can always earn more. There is no maximum! We devote our incredible life potential in pursuit of the impossible. No matter what wondrous creativity we possess, it is held to have no value if it cannot be monetized. “Not good enough – you need a real job.” Where does this value distortion come from?

It comes from civilization’s present manifestation of the bottom layer of Maslow’s famous Hierarchy of Needs. Physiological needs are the most basic of human requirements, and our modern framework says that to meet those we need money. For many tens of thousands of years, this was never the case. For our ancestors, just like for every other species on the planet, the essentials of life were supplied by the natural world.

When money became essential for life, its value was inextricable from survival. We were taught from the earliest age that we were put on Earth to work non-stop so that we could eat. Our education was entirely geared to preparing our money-earning potential because this is how we were going to spend the rest of waking lives: working. At first, most of the work was productive to society and perhaps aligned with our collaborative instincts. However, over time, work has become more of a life of earning money for those at the top of the pyramid – or worse, for faceless corporations that now rule over our societies. The consumption of planetary resources is no longer for our survival – it takes place to create an economy with two different objectives: (1) to enrich those who already have far more than anyone could ever need, and (2) to create enough jobs so that the workers can all continue to work and afford to consume what is being created so that the cycle may continue.

We all fully understand that success takes work. Happiness and productive lives require some effort. But what if survival was free? What if the ability to afford the essentials of life was something you never had to worry about? Imagine the phenomenal freedom that such a societal evolution would release us into! Why couldn’t our public revenue (especially corporate taxes) be used in that way? Why shouldn’t they be? Such a base line would buy all of us the precious time that we need to rethink our economies and our actions on this planet. We could change the course of society without the constant paralysis caused by the law of job preservation trumping every other major change initiative.

It is very hard to predict what such a world would look like, but it is easy to see that it would be better than the obsessive and unsustainable pursuit of growth that we are stuck in now. Perhaps guaranteed basic incomes would extend to become universal basic incomes, available to everyone, rich or poor. Perhaps money would be entirely uncoupled from survival somehow. Perhaps food and shelter would simply be given, and our economies would focus on science or the arts or healing our planet. Who knows?

More reading:

Basic Income Canada Network

Basic Income Earth Network

[Dear Reader: I'd love to have your comments, but NOTE: Blogger will only accept comments here if your browser's Third Party Cookie blocking is turned OFF (even temporarily). Sorry! Not my software...]

Installing a floor in a house with no ceiling.

Imagine you lived in a country where every permanent resident was guaranteed a basic income that provided for the barest essentials of life. Don’t question where the money will come from – we’ll get to that in a moment. Simply imagine that the poorest people in the land each received, say, $1000 every month, no questions asked. How would that country be changed?

Now imagine a contrasting scenario, where you live in a country that has no universal single-payer health insurance. (Canadians can easily observe such an example below our southern border.) What would happen if you slipped and badly broke a bone, or got a viral infection during a global pandemic, or had a child who needed urgent care, and you could not afford to pay for a doctor or a hospital visit or an essential operation? Would any Canadian ever want to go back to the days before 1962 when that was actually the case?

If you are still having trouble with imagining the first scenario, but are all in favour of universal healthcare, ask yourself why medical treatment should be free but essential survival should not be. Canadians don’t apply to be accepted to a hospital when they are sick – they are simply taken in and treated. So why should a homeless person get free food and shelter from their government when they are in a hospital, but not outside of one? How did creating wealth for someone else (i.e. a job) become a prerequisite for life?

The Status QuoLike most wealthy countries, Canada generally offers social assistance – welfare – to those who apply for it and meet the eligibility criteria. We don’t like to see people starving on our streets. In poorer countries, such people might turn exclusively to begging in order to survive. As a society, we don’t tend to hold welfare recipients or beggars in very high regard. For those of us not fortunate enough to inherit our wealth, we have to work to earn a living, and it’s a bit irksome to see welfare money (our tax dollars) going to those who seemingly don’t.