Jane Alison Sherwin's Blog, page 2

June 18, 2015

The Period of Free Fall!

Many individuals with PDA appear to go into complete free-fall during a certain stage of development. The time that this period of free-fall ensues can vary from individual to individual. Mollie’s period of free-fall was between the ages of about 6-10 years old. Now don’t get me wrong, prior to free-fall she was extremely challenging, difficult to handle, avoidant of many demands, required constant attention, had numerous meltdowns both at home and at school and had boundless energy. However from the age of about six years old everything dramatically nosedived. I put this down to a combination of the increasing demands of society for age appropriate behaviour exceeding her ability to cope combined with an increasing awareness of her difficulties and how others viewed her.

The signs of free fall from my experiences of PDA were as follows

An increasing need for full control at all times over her own environment and the people in it

Avoiding demands increased and escalated to anything and everything

She almost appeared to regress before my eyes. What she could achieve at five years of age she was unable to achieve at 7 years of age

Really inappropriate behaviour began to escalate E.G. urinating in inappropriate places.

School refusal began at age six and continued

Huge issues surrounding sleep began at age six

Refusal to leave the home full stop began at about age seven

Meltdowns escalated to multiple times a day last for an hour or more over the tiniest of issues

Her need to cut me off from other people intensified to a suffocating level

At this stage, and it may happen at various ages depending on the individual, it is important to stand back and to take stock of the situation rather than to try to change the behaviour or to let things develop into a battle of wills. These are the warning signs that a complete crash maybe imminent. How you proceed now could alter the path for the future of the child. During this time much damage can be done by proceeding in the wrong direction and this can take years to undo. Alternatively proceeding down the correct path could significantly reduce the damage and make the road to recovery shorter and less bumpy.

What you can do at home

Reduce demands to a level that are tolerable for the child. For some children minor adjustments may need to be made but for others a drastic reduction of demands may be the only option.

Really try to focus on what things are really important and what things can be relaxed on, negotiated or when full control may need to be given to the child. This list will vary depending on age, personal circumstances and the severity of PDA exhibited by the child.

Try to make home as PDA friendly as possible, therefore creating a calm environment for the child. This may mean completely adapting your way of living and what you consider to be the norm in order to fit in with the child with PDA rather than expecting or hoping that the child with PDA will adapt to your normal living environment.

The needs of adults may need to take a back seat in the short term but the needs of siblings may still need factoring into the equation. The needs of siblings may become a non negotiable boundary.

What you can do about school

If your child has become school phobic and is increasingly distressed about attending school then continuing to try to get them into school may cause more harm than good.

The school may need to change their approach to the child and put the appropriate measures in place. School refusal due to school phobia is classed as a health issue and needs addressing by the school in the form of them adjusting the environment for the child in school and making reasonable adjustments.

If the school are unable to adapt or to put the appropriate support into place then if it is possible remove your child from school until a full understanding of your child’s difficulties and the appropriate measures that need to be put into place have been established.

Don’t let local authorities, schools or welfare officers bully you with the threat of fines and prosecution. Your child is not in school for a valid reason and this is different to truancy. The local authority has a duty to provide your child with an education, possibly at home, in the interim. This may not need to be a formal education but could be one that simply aims to re build and re establish trust and relationships. This previous post of mine may help re this situation http://understandingpda.com/2015/03/25/school-refusal-knowledge-is-power/

If your child is not already on the SEN register request that he or she is placed on it and that an Individual Education Plan (IEP) is put into place.

If your child is already on the SEN register then he or she should be able to access an additional £6,000.00 worth of funding per annum. If this funding is not being allocated to your child respectfully request that it is. If the school say that they don’t have the funds suggest that the school apply to the LA in order to have a top up on their SEN funding. This document goes into more detail re SEN funding and was kindly shared with me by another parent http://www.councilfordisabledchildren.org.uk/media/409191/cdc_funding_briefing_for_parents_-_final.pdf

If you feel that what the school can offer your child from their SEN funding falls short of the mark then apply for an Education Health and Care Plan (EHCP) in order to secure further funding to support your child. If your child is achieving academically then focus on the fact that their emotional needs and well being are not currently being met as stipulated in the SEN guidelines. Paras 6.28 to 6.35 describe the four broad areas of need that should be considered: – Communication and Interaction – Cognition and learning – social, emotional and health difficulties – sensory and/or physical needs 6.45 – (talking about the school’s assessment) It should also draw on … the views and experience of parents, the pupils own views and, if relevant, advice from external support services. Schools should take seriously any concerns raised by a parent. 6.17 – Class and subject teachers, supported by their senior leadership team, should make regular assessments of progress for all pupils … 6.18 – It can include progress in areas other than attainment – for instance where a pupil needs to make additional progress with wider development or social needs in order to make a successful transition to adult life.

Most EHCP’s are refused first time around but you can then go to mediation or appeal the decision. Don’t give up and follow each and every process through to the bitter end.

Securing the correct support for your child can be a long and tedious process but it can be achieved with persistence and tenacity. If you look at the process like a ladder then this can help, you can’t miss a rung out in your journey to the top but instead you may have to step on each and every rung during your climb in order to correctly fulfill the pathway to support.

Even with all of the above in place it can take years before tangible differences can be seen so please don’t expect quick results. Sometimes, regardless of the strategies and environment put in place for the child, it can be a case of waiting for the maturing years of the child to catch up.

Good luck in your journey and remember, never give up!

For more information about PDA please visit http://www.pdasociety.org.uk/ & http://www.pdaresource.com/

May 21, 2015

Mainstream Media Coverage at Last!!

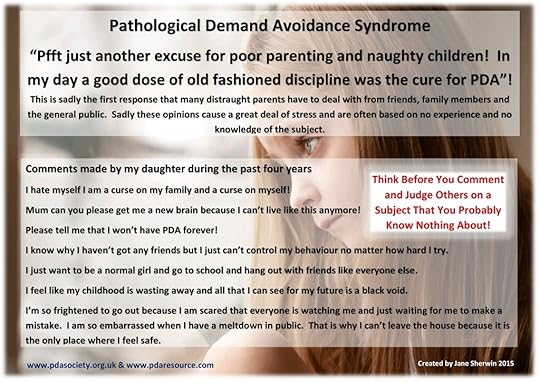

These are exciting times indeed for the PDA Community. At long last this condition is finally gaining some recognition and mainstream media coverage. Unfortunately along with this comes the usual and expected harsh, hurtful and uneducated comments from the ignorant, those who are simply blinkered and unwilling to learn or to understand.

To all of the wonderful parents out there who are living with PDA on a daily basis please, I implore you, simply ignore such rubbish and turn the other cheek. We know and we understand each other and what an amazing job we do in such incredibly trying and difficult circumstances. We are actually the polar opposite of bad parents because we have to be amazing parents in order to simply survive each day while simultaneously nurturing, guiding and managing the most complex of children. Not to mention factoring in the extra skill of often having to be our child’s teacher, advocate, physiologist, psychiatrist and occupational therapist all rolled into one.

Although this awareness will bring out the worst in the ignorant it will, on a positive note, help to transform the lives and long term prospects of so many children and their families. So if we ignore the bleating’s of the bad parenting brigade and focus only on the positives then only good can come out of this exciting time.

When I discovered PDA, five years ago, awareness was very thin on the ground and information and support on the net consisted of the PDA Society (formerly known as the PDA Contact Group), the National Autistic Society (who still had PDA in their related conditions section), Autism East Midlands ( formerly known as Norsaca), The Maze and the wonderful You Tube videos by Neville Starnes https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC6m8JcNEqX6e-2uBHE25BFw. Since then awareness has steadily grown and now it is absolutely mushrooming. I must confess that I did wonder if I would see this during my lifetime and I am stunned at how fast that it has all appeared to suddenly come together.

I can only hope that this coverage not only raises awareness for distraught parents who are desperately trying to understand their child’s complex and confusing behaviour but that it also raises awareness among professionals.

In the support group that I help to run we are having more and more parents joining us who have had professionals suggest PDA to them, in relation to their child’s difficulties, which is greatly encouraging. It wasn’t so long ago that NO professionals appeared to have heard of PDA. It really was a case of parents trying to educate the professionals and becoming increasingly frustrated at hitting brick wall after brick wall. Also, as a parent, when it dawns on you that your knowledge has become greater than the professional who you are turning to for support it does not instil a sense of confidence at all. So let’s just hope that this is a massive turning point for awareness and acceptance of PDA within the professional community also.

With special thanks to Elizabeth Newson, Phil Christie, Ruth Fidler and the PDA Society for their long term efforts to get PDA recognised, accepted and for leading PDA to where we find it today, PDA is coming out of the shadows.

Also thank you to Dr R Jayaram, Dr D Harper and Maverick TV for making a very sensitively approached series and for being brave enough to go public with PDA and to stamp their colours well and truly to the PDA mast.

Born Naughty? Channel 4, Episode 1 http://youtu.be/pMTc_799URA

‘This Morning’ interview discusses PDA with Dr Jayaram http://www.itv.com/thismorning/are-children-born-naughty

For more information about PDA please visit http://www.pdasociety.org.uk/ and http://www.thepdaresource.com/index.html

May 20, 2015

My daughter is autistic with ADHD and sensory issues- there was an issue with my parenting

Fantastic and amazing post by Dinky’s mum in answer to all of the uneducated people who think that kids with neurological conditions are simply naughty and why a different way of parenting is what is needed rather than the old fashioned way which just does not work!!!

Originally posted on Dinky and Me:

Originally posted on Dinky and Me:

Dinky has been diagnosed with autistic spectrum disorder-pathological demand avoidance, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and sensory integration difficulties (also known as sensory processing disorder).

Or for short

ASD-PDA, ADHD, and SPD.

Here in the UK there is a documentary series called ‘Born Naughty?’ (Click here for some info on the programme which features children with ASD-PDA)

There are so many comments like :

’No child is born naughty-it is a parenting issue.’

To an extent they have a point, but not in the way they think… Let me explain…

There was an issue with my parenting… I was made to believe that the only right parenting strategies were those for typically developing children. That was mistake number 1.

I read up on challenging children, watched supernanny and implemented lots of new behavioural strategies. They didn’t work.

Then I found out about PDA, had my lightbulb moment and this came with…

View original 468 more words

April 27, 2015

Two Steps Forward but Only One Step Back!

Well my last post on Mollie and her progress was so positive that even I could not believe the huge steps forward that Mollie was making. But then the period of ‘shutdown’ that is so familiar to so many parents, hit us with a much unexpected boom!!!

She had achieved so much but then she completely shut down and retreated to her room for several weeks. When this happens I am often perplexed and confused on how to move on in a successful manner. A few days of shutdown is one thing but a few weeks, not knowing when it will end, is another thing all together.

It was time to reassess and to re-group. Ok, so she had done tremendously well in accessing a home Education group, groups for children with emotional difficulties, playing out, going for walks and so on. I really and truly believed that we were out of the woods when it came to self-imposed social isolation but I was oh so wrong!

The anxiety associated with accessing the outside world coupled with difficulties playing on line with peers ultimately took their toll. She endured and she controlled herself but this only resulted in her needing major down time in order to recover from the onslaught of the NT world. The good news is that difficulties with social interaction no longer involve meltdowns of indescribable proportions, the bad news is that they do involve self-harm and a need to completely hide away. Difficulties are now internalised rather than externalised. She removed herself from the world and her skin on her arms and face have been picked and picked and picked.

I have cried, I have worried and I have been at a loss of what to do next for the best. Do I leave her to come out of this situation naturally and in her own time or do I try to speed up the situation? As ever, with PDA, there are no wrong or right answers, as parents we can simply only go by out gut instinct.

I left her to it but also went to efforts to reassure her and to remind her that I was here and that she was not alone. I sought advice from a fellow parent whose child also has an extreme presentation of PDA and she also helped to advice given her experiences of her own child. Mollie’s sleep was completely upside down and so it was hard to reach or to engage with her given that she slept during my waking hours.

I began to use the first few hours of the morning when we were both awake to simply sit next to her while we both coloured. I didn’t instigate communication or present demands we just sat quietly and coloured in together. In silence and without words she knew that we were together come ever what would be.

Eventually she began, very slowly to re-integrate back into family life. Wanting to watch a film with her dad or asking me to do something with her all became positive steps in the right direction. In fact just coming downstairs and leaving the comfort of her bedroom or mine, whichever one she had chosen for safety, became a major achievement and a sign that things were moving in the correct direction.

On Saturday Mollie came to a craft fair with me in order to sell our glass art. On Sunday she was up and about watering the garden, going out with her dad to take pictures and basically seeking more social engagement. Today she showered, washed her hair and wanted to go out. We have spent a lovely day together shopping, eating out and watching quizzes on TV.

As ever the cycle of social interaction and the need for ‘down time’ continues and from this I continue to learn. The good news is that periods of ‘down time’ are shorter (weeks rather than months or, in the past, years) and the periods of ‘out time’ are longer and more successful.

It really is a case of two steps forward and one step back but the ratio of 2:1 ensures that we are moving in the correct direction.

This is a picture of Mollie today and how she feels about herself. Underneath the robust exterior of a child with PDA is often a very fragile ego which this picture and the accompanying comments explains in such a concise and honest way.

Today I got out of bed had a shower

April 3, 2015

PDA is NOT ODD! Knowledge is Power!

Why Pathological Demand Avoidance Syndrome (PDA) is not the same as, or another way of, describing Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD)

PDA was proposed by Professor Elizabeth Newson to be seen as a definitive and separate sub group within the category of ‘Pervasive Developmental Disorders (PDD)’ (Newson et al 2003). Elizabeth Newson et al (2003) Pathological Demand Avoidance Syndrome: a necessary distinction within the pervasive developmental disorders; Archives of Diseases in Childhood. Since the publication of this paper terminology has changed and the term PDD has become synonymous with the term ASD. The importance of this is that PDA is now best understood as being one of or part of the Autism Spectrum Conditions (P Christie 2015).

PDA is not currently thought of, by the experts in this field, to be another name for ODD or to be another name to give to an individual with ASC and co morbid ODD. It may be that some individuals do indeed present with ASC and co morbid ODD however this may not always be the case. A child with PDA will have a unique profile that may not be accurately described or indeed helped by the mix and match of these two labels.

“It is inevitably the case that when conditions are defined by what are essentially lists of behavioural features there will be interconnections and overlaps. Aspects of both of these conditions can present in a similar way to those features that make up the profile of PDA. There is also the possibility of the co-existence or ‘co-morbidity’ of different conditions and where this is the case the presentation is especially complex.

ODD, Oppositional Defiant Disorder, itself often exists alongside ADHD, and is characterised by persistent ‘negative, hostile and defiant behaviour’ towards authority. There are obvious similarities here with the demand avoidant behaviour of children with PDA. PDA, though, is made up of more than this, the avoidance and need to control is rooted in anxiety and alongside genuine difficulties in social understanding, which is why it is seen as part of the autism spectrum. This isn’t the case with descriptions of ODD. A small project, supervised by Elizabeth Newson, compared a group of children with ODD and those with a diagnosis of PDA and found that the children with PDA used a much wider range of avoidance strategies, including a degree of social manipulation. The children described as having ODD tended to refuse and be oppositional but not use the range of other strategies. Many children with ODD and their families are said to be helped by positive parenting courses, which is less often the case with children with PDA.” (P Christie 2015 ‘My Daughter is Not Naughty’ p.g 310 – 311)

Recent research has concluded that there are indeed behavioural overlaps between individuals with PDA, typical ASD and ODD but that the PDA group had unique features that were not shared by either of the other two groups and that the PDA group were also atypical of the behavioural profile typically seen in individuals with ASD or conduct problems.

The findings of this research have being summarised in the following information cards and the source for that information is referenced in the cards.

The similarities and differences exhibited between children with PDA and children with ODD.

PDF Version please click here ODDvPDA1

The similarities and differences exhibited between children with a typical presentation of ASC and those with PDA

PDF version please click here ASDvPDA1

Further discussion From the Published Research that was the Source for my Information Cards

While these findings could indicate that the PDA group has an ASD with co-morbid conduct problems, plus additional extreme emotional symptoms, this does not fully accommodate the main difficulties in PDA as outlined in the ‘Introduction’ (of that research paper). Specifically, poor social cognition associated with autism appears inconsistent with instrumental use of social manipulation. Impoverished imagination in autism is inconsistent with role play and excessive fantasy engagement in PDA (e.g. taking on the role of a teacher when interacting with peers and telling tall tales). While children with conduct problems may resist complying in order to pursue their own interests – for example, to avoid a task they dislike – obsessive avoidance of even simple requests, regardless of the personal consequences, goes beyond this. PDA may represent a subset of those who tick boxes for ASD, conduct problems and emotional symptoms, with these additional very characteristic problematic features. However, current educational or therapeutic provision for ASD children with conduct problems does not seem to suit those described as having PDA. The term may well reflect disturbances in more circumscribed socio-cognitive pathways associated with social reciprocity or processing of incoming social cues. These hypotheses must be explored using cognitive-level paradigms. Elucidating the neurocognitive basis of this profile, and possible interventions, remain key issues for future research. O’Nions E, Viding E, Greven CU, Ronald A & Happé F (2013) Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA): exploring the behavioural profile; Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice.

As a result of recent research there has also been the development of the Extreme Demand Avoidance Questionnaire EDA. O’Nions, E., Christie, P., Gould, J., Viding, E. & Happé, F. (2013) Development of the ‘Extreme Demand Avoidance Questionnaire’ (EDA-Q): Preliminary observations on a trait measure for Pathological Demand Avoidance; Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry.

The EDA-Q was found to successfully differentiate children reported by parents to have been identified as having PDA from comparison groups reported to have other diagnoses or behavioural difficulties. It provides a potentially useful means to quantify PDA traits, to assist in identification and research into this behavioural profile.

Key points

• Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA) is a relatively new term that is increasingly being used as a clinical description in the United Kingdom. Children with PDA display an obsessive need to avoid everyday demands, and try to dominate interactions with others, often using socially shocking behaviour with apparently little sense of what is appropriate for their age.

• The present study describes the development and preliminary validation of a trait measure for PDA: the ‘Extreme Demand Avoidance Questionnaire’ (EDA-Q). Scores on this measure successfully differentiated individuals reported to have PDA from comparison groups reported to have other diagnoses or behavioural difficulties, including individuals with ASD, disruptive behaviour, or both. The sensitivity and specificity of the measure to identify PDA was good.

• The 26-item EDA-Q provides a potentially useful means to quantify PDA traits. Scores should be considered an indicator of the risk that a child exhibits the PDA profile, rather than a diagnostic indicator. Further studies are needed to validate the measure in a population for whom information from clinical assessments is available.

Extreme Demand Avoidance Questionnaire (EDA-Q): 26-item final version

Items 1–26 (apart from 14 and 20) are scored as follows: Not true = 0, Some-what true = 1, Mostly true = 2, Very true = 3. Items 14 and 20 are reverse scored: Not true = 3, Some-what true = 2, Mostly true = 1, Very true = 0. Total possible score for items 1–26 = 78.

Not true

Some-what true

Mostly true

Very true

1 Obsessively resists and avoids ordinary demands and requests

2 Complains about illness or physical incapacity when avoiding a request or demand

3 Is driven by the need to be in charge

4 Finds everyday pressures (e.g. having to go on a school trip/visit dentist) intolerably stressful

5 Tells other children how they should behave, but does not feel these rules apply to him/herself

6 Mimics adult mannerisms and styles (e.g. uses phrases adopted from teacher/parent to tell other children off)

7 Has difficulty complying with demands unless they are carefully presented

8 Takes on roles or characters (from TV/real life) and ‘acts them out’

9 Shows little shame or embarrassment (e.g. might throw a tantrum in public and not be embarrassed)

10 Invents fantasy worlds or games and acts them out

11 Good at getting round others and making them do as s/he wants

12 Seems unaware of the differences between him/herself and authority figures (e.g. parents, teachers, police)

13 If pressurised to do something, s/he may have a ‘meltdown’ (e.g. scream, tantrum, hit or kick)

14 Likes to be told s/he has done a good job

15 Mood changes very rapidly (e.g. switches from affectionate to angry in an instant)

16 Knows what to do or say to upset specific people

17 Blames or targets a particular person

18 Denies behaviour s/he has committed, even when caught red handed

19 Seems as if s/he is distracted ‘from within’

20 Makes an effort to maintain his/her reputation with peers

21 Uses outrageous or shocking behaviour to get out of doing something

22 Has bouts of extreme emotional responses to small events (e.g. crying/giggling, becoming furious)

23 Social interaction has to be on his or her own terms

24 Prefers to interact with others in an adopted role, or communicate through props/toys

25 Attempts to negotiate better terms with adults

26 S/he was passive and difficult to engage as an infant

Results

For children aged 5 to 11 a score of 50 and over…

For children aged 12 to 17 a score of 45 and over…

…identifies individuals with an elevated risk of having a profile consistent with PDA.

‘The EDA-Q should not be considered a diagnostic test. For diagnosis, a thorough assessment by an experienced professional is required.’ (PDA Society 2014)

Conclusion

PDA is a very real condition that should be seen as a definitive and separate subgroup with the autism spectrum conditions. Hopefully with continuing research, within this field, PDA will eventually and officially enter the diagnostic manuals. However, in the interim, there is nothing to stop many clinicians from diagnosing this condition based on their own clinical experience and expertise.

Being in a diagnostic manual is not a pre-exquisite required for diagnosis and should not prohibit a clinician from diagnosing PDA as stated by Dr Judith Gould at the Cardiff PDA Conference 2014. Being in a diagnostic manual simply means that finally research has finally caught up, but this can take decades. In the meantime many individuals and families are left without the correct diagnosis or support.

Although Asperger’s has being removed from the DSMV it isn’t that the condition has been deleted but simply that the terminology of individuals presenting with an Asperger’s profile has been changed. However in 1970 this condition or even this profile may not have even existed in diagnostic manuals, does this mean that the condition didn’t exist or merely that it was waiting for diagnostic manuals to catch up with what Hans Asperger’s had already discovered? This is where we are now currently standing with PDA, we are simply waiting for diagnostic manuals and research to catch up with what Professor Elizabeth Newson identified some thirty odd years ago.

The importance of the correct diagnosis is to better understand the child and to be signposted to the correct support and strategies (P Christie). Strategies that are often successful for individuals with ODD do not tend to be successful for individuals with PDA and can, infact, often intensify the issues.

My daughter is not willfully naughty or defiant and describes the need to avoid demands as instinct, something that she does not consciously decide to do but something that she is compelled to do. When she is met with a demand, even a pleasurable one, her stomach goes into somersaults and in order to stop the rising anxiety she simply has to try to avoid the demand. Giving her a countdown or a routine of the day’s activities makes her even worse as does direct eye to eye contract and firm, simple and direct demands. This may vary from child to child but these strategies do not work with her but PDA strategies do!

Published peer reviewed papers on PDA http://www.pdasociety.org.uk/resource...

For more information about PDA please http://www.pdaresource.com/index.html and http://www.pdasociety.org.uk/

March 29, 2015

The Evidence that PDA is Real, Knowledge is Power!

This information was originally collated by myself and Tom Crellin in order to assist a parent who was trying to seek validation with the professionals assessing her child that Pathological Demand Avoidance was a very real and valid diagnosis. I have replicated this as a blog post in the hope that it can help other parents in their journey.

In the 1980’s Professor Elizabeth Newson coined the phrase PDA to describe a group of children who all displayed a unique cluster of symptoms. During this period Professor Newson led the ‘Child Development Research Unit’ at Nottingham University. The cases that were referred to her were often complex and had an unusual developmental profile. The cases would often remind the referring clinician of a child with Autism or Asperger’s Syndrome but they didn’t quite fit this diagnostic profile in that they would often present with an atypical profile. (‘Understanding PDA in Children’ P Christie, R Fidler, M Duncan & Z Healy 2011)

These children had better imaginative play and better social and communication skills (at a surface level) than you would typically expect to see in children with a typical presentation of ASC. Indeed they had enough social insight and sociability to be able to manipulate others in their avoidance of demands and in order to remain in control of their immediate environment. They also all shared what was to become the defining feature of PDA ‘an obsessive need to avoid the demands of others’ (E Newson, K Le Maréchal and C David 2003).

In 2003 the first peer reviewed paper on PDA was published and in this paper Newson proposed that PDA be recognised as a separate sub group within the family of ‘Pervasive Developmental Disorders’ (E Newson, K Le Maréchal and C David 2003). Pervasive Development Disorder (PDD) was the recognised category used at that time by the current classification diagnostic manuals DSMVI and ICD10. (‘Pathological Demand Avoidance Syndrome – My Daughter is Not Naughty – Foreword and Introduction, Christie 2014).

Since the publication of Newson’s paper terminology has changed and the word Autism Spectrum Disorder/Condition has become synonymous with the term PDD. The National Autism Plan for Children, also published in 2003, talked about the term ASD /ASC ‘broadly coinciding with the term Pervasive Developmental Disorder’. The more recently published NICE Guidelines on Autism Spectrum Disorders (2011) described the two terms as being ‘synonymous’. The importance of this is that PDA is best understood as being part of the autism spectrum, or one of the autism spectrum conditions (‘Pathological Demand Avoidance Syndrome – My Daughter is Not Naughty – Foreword and Introduction, Christie 2014).

Although PDA is not currently specifically described in either of the current diagnostic manuals this does not mean that a clinician cannot diagnose this condition based on their own clinical judgment and expertise. Indeed many NHS trusts have no specific policy with regard to the diagnosis of PDA and in-fact advocate that their clinicians are free to diagnose PDA based on their own clinical judgment. This information has being gleaned by Tom Crellin following his request for information regarding the diagnosis of PDA from many NHS trusts via the freedom of information act. https://www.whatdotheyknow.com/search/Tom%20Crellin/all

Increasingly more and more NHS local authorities are diagnosing PDA and this has become very much a postcode lottery. Therefore a clinician saying that PDA is not accepted by the NHS as a real and accepted diagnosis is inaccurate because many of them now do diagnose PDA. It is often down to the individual clinician andl is not down to an NHS directive.

Dr Judith Gould speaking at the PDA conference in November 2011 emphasised that “Diagnostically the PDA sub-group is recognisable and has implications for management and support” and went on to state at the PDA Conference in Cardiff 2014 that the absence of PDA from a diagnostic manual should not be a sufficient reason for clinicians to not diagnose PDA.

The importance of PDA being highlighted and diagnosed is to better understand the child, what drives the behaviour and to signpost others to the correct and most successful handling strategies for PDA which are often different than those traditionally used for individuals with ASC. Therefore if a child has the profile as described in the diagnostic criteria for PDA then a diagnosis of ASD whose profile most closely fits that of PDA would be imperative for the long term management and understanding of that individual. This point is emphasised and discussed by Christie (2007) in ‘The Distinctive Clinical and Educational Needs of Children with Pathological Demand Avoidance Syndrome, Guidelines for Good Practice; Good Autism Practice Journal’.

http://www.pdasociety.org.uk/files/download/b7d5fcf5408a063

The following research helped to establish the differences and the similarities between children who fitted a typical profile of an autism spectrum condition (ASC), children who fitted a typical profile of conduct problems e.g. Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) and those who fitted the Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA) profile. Although behaviour overlaps were found between the PDA group and the ASC and CP group there were also distinct differences found.

http://m.aut.sagepub.com/content/early/2014/04/29/1362361313481861.full.pdf

O’Nions E, Viding E, Greven CU, Ronald A & Happé F (2013) Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA): exploring the behavioural profile; Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice.

The similarities and differences between a typical ASC profile and the profile of a child with PDA

The similarities and differences between a child with Conduct Disorder i.e. Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) and those with a PDA profile.

The ‘Extreme Demand Avoidance Questionnaire (EDAQ)’ which resulted from research conducted by O’Nions, E., Christie, P., Gould, J., Viding, E. & Happé, F http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24117718, is a screening tool to highlight the possibility of a child having PDA http://www.pdasociety.org.uk/resources/extreme-demand-avoidance-questionnaire

The Disco diagnostic tool, devised by Gould and Wing, has PDA specific questions included to indicate if a child may have ASD sub group PDA rather than a typical presentation of ASC.

At the Lorna Wing Centre, the Diagnostic Interview for Social and Communication Disorders (DISCO) is used as part of the diagnostic process.

The DISCO has over 500 questions relating to development and untypical behaviours.

Seventeen questions relate to the behaviour described by Professor Newson and her team.

DISCO

• Unusually quiet and passive in infancy

• Clumsy in gross movements

• Communicates through doll, puppet, toy animal etc

• Lacks awareness of age group, social hierarchy etc

• Rapid inexplicable changes from loving to aggression

• Uses peers as ‘mechanical aids’, bossy and domineering

• Repetitive role play – lives the part, not usual pretence

• Hands seem limp and weak for unwelcome tasks

• Repetitive questioning

• Obsessed with a person, real or fiction

• Blames others for own misdeeds

• Harasses another person – may like or dislike them

• Lack of cooperation, strongly resists

• Difficulties with others, tease, bully, refuse to take turns, makes trouble

• Socially manipulative behaviour to avoid demands

• Socially shocking behaviour with deliberate intent

• Lies, cheats, steals, fantasises, causing distress to others

(Judith Gould PDA Conference London 2011)

Leading professionals in the field of Autism appear to be in agreement that the PDA subgroup is definable and that this has implications for the successful management of the child. Unfortunately many clinicians who are not at the cutting edge of new research and developments are often unaware of recent advances and changes in terminology. I hope that this post may give you knowledge in order to successfully fight for your child and for him or her to receive the correct diagnosis and management because this is key to the long term prognosis for these children.

For more information about PDA please visit http://www.pdaresource.com/ and the http://www.pdasociety.org.uk/

If you require a friendly and non judgmental parent support group then please apply to join https://www.facebook.com/groups/pdagl...

March 25, 2015

School Refusal, Knowledge is Power!

During recent months I have become increasingly concerned at the huge amount of pressure that parents often face from schools and their Local Authority when their child refuses to attend school. For a child with PDA this refusal is often steeped in high anxiety and an inability to cope with the pressures of the school day and all of the demands that this may entail any longer. This is therefore a health and a special education needs issue and not a truancy issue and should therefore be treated as such by the local authority.

Parents who are already completely stressed out, struggling to cope with daily challenging behaviour and may be completely on their knees emotionally are often then subjected to, what I can describe as, bully boy tactics rather than support from their child’s school and the local authority. This is something that I am seeing all too often in the support group that I help to run.

Whether local authorities and the professionals involved, in many of these cases, are actually trying to pull the wool over parent’s eyes or are simply unaware of the correct procedure that they should actually be following remains unclear and the waters are indeed murky.

Therefore it is essential for parents to fully educate themselves on their rights and the duties of their local authority in order to become empowered in these situations and to not feel intimidated by threats of fines or prosecution. The Local Authority, the school and the other professionals involved in your case should be supporting you, working with you to solve the issue, listening to you and taking your concerns seriously and should not be threatening you with fines and prosecution. In fact the local authority should be providing your child with an education at home in the interim rather than blaming you for your child not currently being educated.

Yes, if the child is registered on the school roll then it is in everyone’s best interests, including the interests of the child, for school attendance to be re-established. However it is not in the best interests of the child for school attendance to be re-established as quickly as possible without the correct support being put in place first. A carefully planned transition back into the school placement is often also required so that the child can take small baby steps and gradually re build their confidence and trust in the school.

The child with PDA will often only have a very limited ability to be affected by the mistakes of others and not getting things right as soon as possible could cause the situation to become irreversible. Therefore time is not of the essence but patience and the correct support package is. A child with PDA who is school refusing cannot be forced into school by their parents due to the huge detriment that this could potentially cause to the child’s emotional well-being and to the long term damage that this could cause. Mistakes made at this stage could cause the child to become a long term and permanent school refuser, so treading carefully and slowly now could make all of the difference for the child’s ability to attend school in the future.

What you need to do if your child is school refusing.

Inform the school immediately and explain why your child is unable to attend. School phobia, anxiety and depression all fall under health and are legitimate reasons for your child to be off school. It is helpful, but not essential, to try to provide the school with some kind of medical evidence in the form of a GP note, letter from CAMHS or if your child has a diagnosis of an ASC, specifically stating the PDA sub group or otherwise then this is in itself evidence that your child will potentially have high levels of anxiety.

If you don’t have a diagnosis or any professional input at this stage then make an appointment with your GP with a view to enlist the help and support of CAMHS or other mental health professionals. Simply being in the system and been seeing to be pursuing professional help will assist you to validate what you are reporting to the school re your child’s mental health issues.

Keep all contact with the school via email so that there is a paper trail of your efforts to keep the school informed. Also keep the school informed of methods that you have tried in order to assist your child back into school and keep them updated of how your child is coping and the steps/measures that you are taking to try to solve this issue. E.G. GP appointments and so on.

If your child cannot attend school due to a health problem E.G. anxiety, depression, school phobia or school refusal, after 15 days the council must intervene and provide a suitable education. The education arranged by the local authority should be on a full time basis, unless, in the interests of the child, part-time education is considered to be more suitable. This would be for reasons relating to the child’s mental health. The local authority should provide a minimum of five hours per week but in the case of a school refuser or school phobic councils should not assume that this is adequate. The hours allocated to a child should be regularly reviewed and adjusted in accordance with how much the child can manage.

Apply for an Education, Health & Care Plan assessment in order to access support and funding for your child within the school placement. This is likely to be initially refused but then follow the process through. Request mediation and if this fails request a mediation certificate and appeal the decision. It can be a long road and many doors will shut in your face but each time one does just pick up the baton again and keep going until another door opens. For many children with PDA maintaining a healthy attendance record at school while simultaneously ensuring that the child’s emotional well-being is being adequately catered for may require additional funding and support in the form of an EHCP.

The source for this information is ‘Local Government OMBUDSMAN – Out of school…….out of mind? Focus Report: learning lessons from complaints. Focus-report-Out-of-school-Sept-2011 I would advise any parents who are experiencing issues leading to school refusal or who are considering removing their child from school until appropriate provision is put into place for their child to read this document fully and in depth.

www.lgo.org.uk

This report also features lots of other advice and information re other reasons why a child may not be in school and what the duties of the local authority are, including if the child has being permanently excluded. It also features very useful and informative case studies of when local authorities have not responded accordingly with their duty to provide a suitable education for children who are out of school. If the local authority fails in its duties to provide an education for a child who is out of school they can be prosecuted and the parents can receive compensation.

Thank you for reading this post. For more information please visit http://www.pdaresource.com/ and http://www.pdasociety.org.uk/

March 20, 2015

Mollie Goes From Strength to Strength

I began writing this blog nearly two years ago, my how time flies. At that stage the worst and most debilitating years in our PDA journey were thankfully behind us and this blog detailed the journey of our recovery. I say ‘our’ because it has seen improvements and many changes for both Mollie and me.

Two years ago we were both, crushed, broken and battered (not literally) by each other and by the system. Two years later and we have a much more positive story to share and to tell.

Mollie has being making sudden and dramatic improvements which have truly exceeded my wildest expectations. Following two years of hard slog, taking one step forward followed by two steps back and times when I truly never thought that I would see the light at the end of the tunnel I am pleased to say that I am now positively basking in the warm glow of the light.

The real big changes have come in just the last few months or so. It could be that puberty has had a major influence in this or it could be a combination of very many factors coming together and finally pulling in the same direction all at once. Two years of social and demand detox combined with an all round holistic approach and maturing years may, finally, be beginning to really pay dividends.

Mollie is generally far, far happier and her emotional well being is far improved from what it once was. She is now able to socialise and to interact much more successfully without feeling the need to, or perhaps with now being able to supress her need to control all interactions. Large family occasions which would have at one time being either avoided or would have ended in disaster are now being achieved with ease and with regularity. Christmas day was a huge success and passed by without incident.

Our glass fusing project is coming on in leaps and bounds and I will shortly be booking our first craft fair. Making these items is so deeply calming and really helps to clear my mind. Mollie occasionally joins me but this has really turned out to be my pastime but my mental health is important too. Mollie fully intends to join me when we sell the goods though and to pocket half of the cash ha ha. This will give her more social exposure and the chance to converse with other people.

Mollie also beginning to show much better control, in general, over how she deals with stressful situations and also awareness and empathy to those who may be affected. She will often apologise if she has being snappy and explain why or how she was feeling at that given moment.

Only last night she had attended an event that she had found stressful and she showed great awareness of her internal state and demonstrated her own problems solving techniques for helping to overcome this. She told me that she was stressed and asked if we could call in Aldi on the way home so that she could get some ice cream as this would help to calm her down.

During meals out if she is stressed, rather than exploding, she sits under the table. Either Lee or I will pick up on this and ask her if she would like to go outside for a breather. If we are at a family gathering at my mums she will ask me to go and relax in my mum’s bedroom with her if things are becoming too much and of course there is always the option of coming home if dealing with things are becoming impossible for her.

Mollie had her bedroom redecorated just after Christmas and she handpicked everything. Since then she has being sleeping in her own room and going up to bed by herself. She has had her computer, XBox and everything else transferred into her room which is now a place that she refers to as her own special retreat. Just recently she has begun playing online with her peers and she is doing remarkably well and does not appear to be over bossy or argumentative with them.

Within the last few weeks she has had her hair dip dyed at the hairdressers and the bleached ends have now being coloured with Pink dye. She has being going out more regular and she has become a very entertaining companion for me. We are enjoying shopping trips, walks with the dog, meals out and so on.

She has also recently accessed the following service in order to try to help her meet other children of a similar age and to establish some friendships. She has only being to one social night but it went very well and she came home beaming. She found the ‘Wellbeing Workshop’ very difficult due to being expected to discuss her feelings which isn’t something that she is comfortable with at all. But it is still good news because she at least has access to social nights and outings. This is a major achievement for her indeed.

http://www.changes.org.uk/html/young_people.html

Mollie is also starting to show a very real and exceptionally good flair for art and she loves photography. So after two years of radical unschooling clear and positive interests are beginning to become very apparent. Today we went for a walk to watch the solar eclipse and Mollie also took lots of photos which she wanted to draw in the next few days.

I suggested that if she was interested I could see if there were any local photography and art courses or groups that she could join. She was very interested indeed and has asked me to investigate this possibility for her. We then went to town in the afternoon and stocked her up with paper, charcoals, pencils and so on so that she fully stocked ready to start her artwork. I also advised that perhaps she could set up her own ‘Mollie’s Art and Photography’ facebook page and to post her work on there.

Here is some of Mollie’s recent artwork, all drawn completely freehand. If she can achieve this at only 11 years of age then the possibilities for the future really are endless

This is Mollie’s self portrait.

This is Ann, her personal assistant and respite provider for me.

This is her birdhouse that she built herself from flat pack and painted. The designs on it have being drawn freehand by Mollie.

We both find ourselves so much happier and calmer than either of us have being in years. I really feel that we have seen dramatic and sudden progress on the back of a very slow burn. I am beginning to finally see a future for Mollie, I am beginning to dream of what I never thought would be possible. With how things are progressing I can see no reason why she shouldn’t be able to manage some type of part-time college course for art, photography or design by the time she is sixteen.

Thank you for reading this post and for more information on PDA please visit

February 21, 2015

Traditional ‘Rewards and Consequences’ Knowledge is Power

Traditional ‘Rewards and Consequences’ (as they relate to an individual with PDA)

It is fairly well documented by professionals, experienced in Pathological Demand Avoidance Syndrome that rewards and consequences do not tend to help the individual with PDA to modify their behaviour or to comply with requests or demands. That being said, there will always be exceptions to the rule. Even an individual, for whom this approach would usually be met with resistance or even anger, may occasionally take the bait and be able to comply in order to achieve the reward. This may wrongly lead others to assume that rewards and consequences do have their place in successful PDA management. But the reality of the situation may be that the reward only worked today because the individual’s anxiety levels allowed him to comply, rather than the reward being the pivotal feature. The difficulty with rewards and consequences is that results can often be short lived and may seldom produce any long term benefits or changes. Also the use of rewards and consequences can, in many cases, actually cause an increase in challenging behaviour and appear to make it even more difficult for the individual to comply.

Possible Reasons Why Rewards and Consequences Do Not Tend to Work for Individuals with PDA

The most important reason may be that the individual simply can’t do what is being asked of them, regardless of the reward or the consequence that is on offer. High anxiety and an instinctive need to avoid and to be in control at all times may simply override the ability of the individual to change who they instinctively are, in order to receive a reward or to avoid a consequence.

The individual may desperately want the reward or may desperately want to avoid the consequence but simply can’t, rather than won’t, do what is being asked of him or her. Does offering rewards and consequences work as a successful strategy for making an individual with an eating disorder compliantly eat food? Does offering rewards and consequences work as a successful strategy for helping the individual with OCD to stop obsessive thoughts, eliminate compulsive behaviour, that they need to do in order to reduce stress and feel calm, or to do things that their OCD may prevent them from doing so like swimming in a public pool that, in their eyes, is a pool of contamination?

I think that the answer on both counts would be no, because these individuals have complex mental health issues that need careful intervention and therapy. Rewards and Consequences seldom help the individual with PDA to comply or to moderate their behaviour because, just like the individual with OCD or an eating disorder, they also need careful intervention and a different method of reaching and helping them to adjust challenging behaviour that stems from high anxiety, caused by a neurological condition.

The child with PDA may often feel like an adult and has difficulty in understanding why they are not allowed to have the same rights and choices as an adult. Why do we expect children to never show the same behaviours that adults freely exhibit like being grumpy, short tempered, using bad language, shouting, having control over their own lives and so on. The individual with PDA may feel deeply offended and patronised by being treated like a child, which is essentially who ‘rewards and consequences’ are typically aimed at, as a strategy of behaviour modification. We don’t expect adults to have a reward chart on the wall where every aspect of daily life and behaviour are either rewarded or reprimanded with a consequence and so I guess that children with PDA do not expect to have this either. I must say that I can see their point.

The individual with PDA may feel that a reward or consequence is deeply unfair and unjust if the thing that is being asked of them is something that they simply can’t achieve, due to high anxiety about complying, rather than being something that they simply refuse to do due to bring wilful and defiant. Mollie has described rewards and consequences as nothing but blackmail and that the use of them makes her more angry and stressed and even less likely to be able to comply. The use of rewards and consequences can actually have the opposite effect and make the individual less able to comply due to the applied pressure that the use of such strategies may present to the individual. Rewards and consequences may only serve to make the individual feel even less in control, by giving the person administering the rewards and consequences the balance of control, having the armoury of the ‘carrot’ or the ‘stick’.

Not only can rewards and consequences be unsuccessful for changing the behaviour of an individual with PDA, they can actually be detrimental to the individual with PDA. The use of rewards and consequences can be instrumental in raising anxiety levels, which may only serve to make the individual feel even more out of control of his or her own environment which can, in turn, lead to panic and meltdown.

Other Ways to Try to Deal with Challenging Behaviour

This, of course, doesn’t mean that individuals with PDA should be able to display all types of inappropriate or offensive behaviour, because that is not acceptable or fair on other members of the family or society. What it simply means is that there may be more productive ways of reaching the desired outcome.

Activities that are against the law or pose a health and safety risk to themselves, or others obviously, need to be stopped. However stopping a behaviour or removing an individual from a situation, where things are out of control for the safety of the individual or for others, is not the same as giving a planned consequence. We are removing them as a natural consequence to non-negotiable behaviour but we are not then punishing the behaviour itself.

Individuals with PDA often follow rules and laws from a higher power and so, for many individuals, breaking the law is hopefully not going to be an issue. Using a higher power or health and safety can help to enforce some rules and also a visual rule (e.g. a poster that says do not run at the side of the swimming pool) can be useful, productive and can be utilised for other areas of difficulty.

If the individual feels calm they are more likely to be able to follow simply demands, and so providing the individual with the correct environment is often key to helping produce positive behaviours. The calmer and the more in control the individual feels, of his or her own environment, is the most likely to be a successful way of reducing challenging behaviour. Helping the individual with PDA to present with acceptable behaviour is often more about a whole round holistic approach that simultaneously tackles many different angles at the same time, rather than simply trying to discipline challenging behaviour out of the individual.

Key areas to try to help keep the individual with PDA calm and therefore to reduce challenging behaviour

Getting school right and as PDA friendly as possible.

Getting home right with as much of a demand free and PDA friendly approach as possible, within the family unit.

The consistent use of basic PDA strategies by all people and agencies involved with the individual is a must.

Listen to the individual and learn to notice subtle hints that they are not coping and are struggling, and adjust your expectations accordingly.

Reduce triggers that may cause a flashpoint, or think of ways to reduce the stress that these triggers may produce.

Accommodate any sensory issues.

Work on promoting emotional well-being and confidence in the individual, because feeling worthless can cause deep unhappiness which can affect behaviour.

Caveat: I am not a professional and so this information is based solely on my own experiences of living with a child with PDA as well as from many years within support groups, along with advice and literature from professionals within this field and advice from other parents. I have written this following a request from another parent and it is not my attention for this paper to in any way tell other parents how to deal with their children. This is simply the method that has bought us the best results and my understanding of how rewards and consequences may be perceived by the individual, and why they appear to be an unsuccessful methods of modifying behaviour for the individual with PDA.

·

Traditional ‘Rewards and Consequences’

Traditional ‘Rewards and Consequences’ (as they relate to an individual with PDA)

It is fairly well documented by professionals, experienced in Pathological Demand Avoidance Syndrome that rewards and consequences do not tend to help the individual with PDA to modify their behaviour or to comply with requests or demands. That being said, there will always be exceptions to the rule. Even an individual, for whom this approach would usually be met with resistance or even anger, may occasionally take the bait and be able to comply in order to achieve the reward. This may wrongly lead others to assume that rewards and consequences do have their place in successful PDA management. But the reality of the situation may be that the reward only worked today because the individual’s anxiety levels allowed him to comply, rather than the reward being the pivotal feature. The difficulty with rewards and consequences is that results can often be short lived and may seldom produce any long term benefits or changes. Also the use of rewards and consequences can, in many cases, actually cause an increase in challenging behaviour and appear to make it even more difficult for the individual to comply.

Possible Reasons Why Rewards and Consequences Do Not Tend to Work for Individuals with PDA

The most important reason may be that the individual simply can’t do what is being asked of them, regardless of the reward or the consequence that is on offer. High anxiety and an instinctive need to avoid and to be in control at all times may simply override the ability of the individual to change who they instinctively are, in order to receive a reward or to avoid a consequence.

The individual may desperately want the reward or may desperately want to avoid the consequence but simply can’t, rather than won’t, do what is being asked of him or her. Does offering rewards and consequences work as a successful strategy for making an individual with an eating disorder compliantly eat food? Does offering rewards and consequences work as a successful strategy for helping the individual with OCD to stop obsessive thoughts, eliminate compulsive behaviour, that they need to do in order to reduce stress and feel calm, or to do things that their OCD may prevent them from doing so like swimming in a public pool that, in their eyes, is a pool of contamination?

I think that the answer on both counts would be no, because these individuals have complex mental health issues that need careful intervention and therapy. Rewards and Consequences seldom help the individual with PDA to comply or to moderate their behaviour because, just like the individual with OCD or an eating disorder, they also need careful intervention and a different method of reaching and helping them to adjust challenging behaviour that stems from high anxiety, caused by a neurological condition.

The child with PDA may often feel like an adult and has difficulty in understanding why they are not allowed to have the same rights and choices as an adult. Why do we expect children to never show the same behaviours that adults freely exhibit like being grumpy, short tempered, using bad language, shouting, having control over their own lives and so on. The individual with PDA may feel deeply offended and patronised by being treated like a child, which is essentially who ‘rewards and consequences’ are typically aimed at, as a strategy of behaviour modification. We don’t expect adults to have a reward chart on the wall where every aspect of daily life and behaviour are either rewarded or reprimanded with a consequence and so I guess that children with PDA do not expect to have this either. I must say that I can see their point.

The individual with PDA may feel that a reward or consequence is deeply unfair and unjust if the thing that is being asked of them is something that they simply can’t achieve, due to high anxiety about complying, rather than being something that they simply refuse to do due to bring wilful and defiant. Mollie has described rewards and consequences as nothing but blackmail and that the use of them makes her more angry and stressed and even less likely to be able to comply. The use of rewards and consequences can actually have the opposite effect and make the individual less able to comply due to the applied pressure that the use of such strategies may present to the individual. Rewards and consequences may only serve to make the individual feel even less in control, by giving the person administering the rewards and consequences the balance of control, having the armoury of the ‘carrot’ or the ‘stick’.

Not only can rewards and consequences be unsuccessful for changing the behaviour of an individual with PDA, they can actually be detrimental to the individual with PDA. The use of rewards and consequences can be instrumental in raising anxiety levels, which may only serve to make the individual feel even more out of control of his or her own environment which can, in turn, lead to panic and meltdown.

Other Ways to Try to Deal with Challenging Behaviour

This, of course, doesn’t mean that individuals with PDA should be able to display all types of inappropriate or offensive behaviour, because that is not acceptable or fair on other members of the family or society. What it simply means is that there may be more productive ways of reaching the desired outcome.

Activities that are against the law or pose a health and safety risk to themselves, or others obviously, need to be stopped. However stopping a behaviour or removing an individual from a situation, where things are out of control for the safety of the individual or for others, is not the same as giving a planned consequence. We are removing them as a natural consequence to non-negotiable behaviour but we are not then punishing the behaviour itself.

Individuals with PDA often follow rules and laws from a higher power and so, for many individuals, breaking the law is hopefully not going to be an issue. Using a higher power or health and safety can help to enforce some rules and also a visual rule (e.g. a poster that says do not run at the side of the swimming pool) can be useful, productive and can be utilised for other areas of difficulty.

If the individual feels calm they are more likely to be able to follow simply demands, and so providing the individual with the correct environment is often key to helping produce positive behaviours. The calmer and the more in control the individual feels, of his or her own environment, is the most likely to be a successful way of reducing challenging behaviour. Helping the individual with PDA to present with acceptable behaviour is often more about a whole round holistic approach that simultaneously tackles many different angles at the same time, rather than simply trying to discipline challenging behaviour out of the individual.

Key areas to try to help keep the individual with PDA calm and therefore to reduce challenging behaviour

Getting school right and as PDA friendly as possible.

Getting home right with as much of a demand free and PDA friendly approach as possible, within the family unit.

The consistent use of basic PDA strategies by all people and agencies involved with the individual is a must.

Listen to the individual and learn to notice subtle hints that they are not coping and are struggling, and adjust your expectations accordingly.

Reduce triggers that may cause a flashpoint, or think of ways to reduce the stress that these triggers may produce.

Accommodate any sensory issues.

Work on promoting emotional well-being and confidence in the individual, because feeling worthless can cause deep unhappiness which can affect behaviour.

Caveat: I am not a professional and so this information is based solely on my own experiences of living with a child with PDA as well as from many years within support groups, along with advice and literature from professionals within this field and advice from other parents. I have written this following a request from another parent and it is not my attention for this paper to in any way tell other parents how to deal with their children. This is simply the method that has bought us the best results and my understanding of how rewards and consequences may be perceived by the individual, and why they appear to be an unsuccessful methods of modifying behaviour for the individual with PDA.

·