Nicola L.C. Talbot's Blog

April 14, 2024

Smile for the Camera: a cybercrime short story

Smile for the Camera is a my latest cybercrime short story (approximately 2,500 words) published as an ebook, following on from last year’s publication of Unsocial Media.

Smile for the Camera is a my latest cybercrime short story (approximately 2,500 words) published as an ebook, following on from last year’s publication of Unsocial Media.

Evelyn (Eve), a CCTV operator, sees too much information while she monitors a store’s self-service checkout tills.

For further details, including a sample, see the book’s home page.

April 27, 2023

Unsocial Media: a cybercrime short story

[Abridged from my article posted on the Dickimaw Books Blog.]

Unsocial Media is a cybercrime fiction short story (a little under 4,000 words) due out as an ebook on 12th May 2023. This is my first published work to be set in contemporary times (and also the first story with an unnamed first person narrator). The short story I've Heard the Mermaid Sing is set in 1928, the novel The Private Enemy is set in the future, The Fourth Protectorate (still in hiatus) is set in an alternative past, and Muirgealia (pending) is set in a fantasy world. (The children’s stories are in a world of anthropomorphic animals.)

Unsocial Media is a cybercrime fiction short story (a little under 4,000 words) due out as an ebook on 12th May 2023. This is my first published work to be set in contemporary times (and also the first story with an unnamed first person narrator). The short story I've Heard the Mermaid Sing is set in 1928, the novel The Private Enemy is set in the future, The Fourth Protectorate (still in hiatus) is set in an alternative past, and Muirgealia (pending) is set in a fantasy world. (The children’s stories are in a world of anthropomorphic animals.)

Greg has unwisely accepted a friend request from “Natalie”, a stranger who starts to stalk him after failing to hook him in a scam. The stalking moves from the digital world to real life when Natalie shares a photo of Greg with his neighbour Susie, in what looks like a compromising position. Unknown to any of them, Greg’s wife (the narrator) has a secret life of her own and is doggedly following Natalie’s trail.

The story is fiction but was inspired by various news articles in cybersecurity channels, anecdotes and posts, as well as behaviour and attitudes that I’ve encountered over the years in real life (names and other information have been changed and, no, the narrator isn’t me). Consider it a cautionary tale but, unlike The Foolish Hedgehog, this is a cautionary tale for adults. The cover image features what may look at first glance like a red elephant head with black areas around the eyes, but is, in fact, a red thumbs down emoji 👎 with a domino mask. Things aren’t always what they seem.

For further details, including a sample, see the book’s home page.

December 15, 2022

Hello E-Hedgehog

[Originally posted in the Dickimaw Books blog.]

A little hedgehog promises his grandmother that he won’t go onto the wasteland (the road) where the dragons (vehicles) live, but one day he’s tempted onto the road by a hungry crow. Will he manage to get home safely?

A little hedgehog promises his grandmother that he won’t go onto the wasteland (the road) where the dragons (vehicles) live, but one day he’s tempted onto the road by a hungry crow. Will he manage to get home safely?

Last year, my illustrated children’s books went out of print when Ingram retired their saddle stitch format, but now The Foolish Hedgehog is back again, this time as an ebook.

February 7, 2022

Muirgealia: A Tale of Temporal Enchantment

[Originally posted in the Dickimaw Books blog.] If you’ve looked at the [Dickimaw Books] book list recently, you may have noticed a new pending title called Muirgealia. Muirgealia is a land that was home to a mixture of enchanters (with various magical abilities, including telepathy, telekinesis and the power to create areas of stasis), mystics (who can see through time in the form of visions), and handcræfters (people with no magical ability, who are typically inventors, engineers or artisans). Five hundred years before the start of the story, two calamities (one natural and the other contrived) lead to the usurpation of power by the enchanter¹ Pelouana, a traitor who formed an alliance with the warlords from the neighbouring land of Acralund. A warning from the future allowed most of the Muirgealians to escape into exile before a curse hit both Pelouana and Acralund.

At the start of the story, Muirgealia is deserted, except for Pelouana who has been trapped there for five centuries as a result of a magical explosion that fractured a stasis field (where time is almost stopped) causing drifting pockets of stasis. Acralund is sparsely populated by the remnant descendants of the warlords, who are still affected by the curse that prevents them from rebuilding their civilisation. The descendants of the Muirgealians in exile are in hiding, waiting for their future ally to be born and grow up to help them regain their land.

The people of Langdene, to the north of Muirgealia, unwittingly became caught up in events when their king ordered a mass migration south to escape a savage winter. They pass through Muirgealia just after Pelouana has taken over. She murders the king, suspecting him of being the one who had cursed her (it was, in fact, one of his descendants), and a rift forms between the king’s two surviving sons who end up creating two new nations, Farlania and Barlaneland, in the land to the south of Acralund.

Five hundred years later, Luciana is the daughter of the king of Barlaneland and Rupert is the second son of the king of Farlania. Pelouana is finally freed by the Acran, who first target Rupert, believing him to be the one who cursed them, and then target Luciana, believing that they can get to Rupert through her. Meanwhile, the Muirgealians want revenge and their land back (which contains all their books and other cultural works locked up in time). More importantly, they need to destroy the stasis bubbles that will cause havoc if they break free from the loose tethers that are keeping them in Muirgealia and drift around the rest of the world.

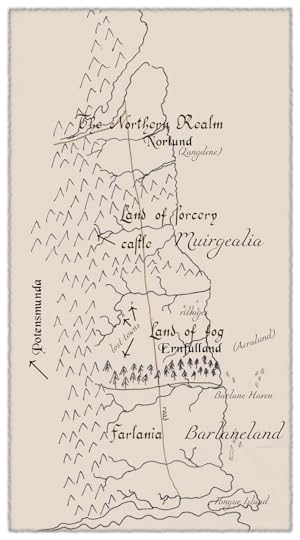

The “world” in question is an Earth-like planet with a single moon and orbiting a single star (or perhaps it is Earth in some forgotten past or other timeline). Langdene, Muirgealia, Acralund, Farlania and Barlaneland are all located in an eastern seaboard, bordered to the west by a mountain range. Well over a thousand years earlier, the entire continent was ruled by Potensmunda, a land beyond the mountains. The Potensmundan Empire was much like the Roman Empire. If you know any Latin, you might pick out the words “potens” (powerful) and “munda” (clean). The empire was like bleach, erasing all local languages and replacing them with Potensmundan. The empire has long since fallen, but the language and a few structures, including old roads, remain.

In universe, the above map was created long ago by people who didn’t have the modern surveyor’s tools that we have in our own world, so it’s not accurate. The three different fonts represent three different sets of handwriting, as the map has been modified over time. The translation convention applies here. English is used for modern dialects of Potensmundan, and the few words of ancient high Potensmundan are in Latin. The character names (which are a mixture of Roman, Anglo-Saxon and Germanic) can also be considered as having been translated into the closest match.

Incidentally, in case you’re wondering why I didn’t choose “Potensmundi” (powerful world) instead, there are two reasons. The first is aesthetic, I prefer the sound of Potensmunda. (I was looking for a four or five syllable name ending in an ahh sound, but don’t ask me why.) The second is pragmatic: an Internet search of “potensmundi” produces a huge load of hits (which isn’t particularly surprising, given its meaning) whereas “potensmunda” (or “potens munda”) isn’t so common, so I’m less likely to step into someone else’s digital footprints.

If you’re keen to know when Muirgealia is published, you can sign up to be notified, if you have a Dickimaw Bookssite account. Alternatively, you can subscribe to the RSS feed for this blog on GoodReads or follow the Dickimaw Books Facebook page.

What happened to The Fourth Protectorate, which I’ve previously posted about and is also still listed as pending? Life happened. When I wrote it, the social disorder of the 1980s seemed firmly in the past. Recent years have put me off it. The Fourth Protectorate is without doubt the biggest and bleakest of all my novels. Muirgealia is the shortest and lightest. The Private Enemy comes somewhere in between.

¹Muirgealians use “enchanter” as a gender-neutral term. They don’t use “enchantress”. The Acran and Langdeners use “sorceress” instead.

February 12, 2021

Farewell to the Hedgehog and Little Duck

[Originally posted in the Dickimaw Books blog.] Ingram (the parent company of Lightning Source, who print and distribute paperback titles published by Dickimaw Books) have announced that their saddle stitch format is being retired on 1st March 2021 because the software and equipment used to print that format have become obsolete. This means that the first editions of “The Foolish Hedgehog” and “Quack, Quack, Quack, Give My Hat Back!” will be going out of print on that date.

[Originally posted in the Dickimaw Books blog.] Ingram (the parent company of Lightning Source, who print and distribute paperback titles published by Dickimaw Books) have announced that their saddle stitch format is being retired on 1st March 2021 because the software and equipment used to print that format have become obsolete. This means that the first editions of “The Foolish Hedgehog” and “Quack, Quack, Quack, Give My Hat Back!” will be going out of print on that date.

The saddle stitch format is where the pages are held together by staples down the spine. This works well for these illustrated children’s books, particularly “Quack, Quack, Quack, Give My Hat Back!” which has double spread images. The other paperback titles published by Dickimaw Books all use perfect bound (and so aren’t affected by this change), which has a stiff, flat, rectangular spine. Perfect bound doesn’t work well for young children’s books which are often opened out flat.

If you have been thinking about buying a copy of either of these books then you will have to order them from an online book seller before 1st March 2021. After that date, there may still be copies available from the Dickimaw Books store (once it reopens) until existing stock runs out.

February 20, 2019

ASD and English GCSEs

For those of you who don’t know, I write both fiction and text books. These involve very different writing styles.

Creative writing involves metaphors, similes, double entendres, sub-text, hyperbole, synecdoche, litotes, aporia, aposiopesis, intertextuality and so on. Readers often enjoy discovering new meaning when they re-read their favourite books. The language used within the work can trigger emotional responses.

Technical writing requires plain English, written in a precise, unambiguous style. Customers don’t want to be told that the product they purchased doesn’t actually do what they thought because they didn’t interpret the subtle nuances within the product specifications. If I buy a DIY kit I don’t expect to have to analyse the instructions for hidden meaning. Technical manuals, user guides, official documents should all provide the reader with the information they require accurately and concisely. In our modern Internet age, people reading web pages may well be reading the text through a translation service. For example, this page is written in English, but if a non-English speaker wants to read it they can do so using, for example, Google Translate. These translation services work best with plain, unambiguous, well-written, error-free text. This is something that all businesses and organisations should bear in mind if they have an interest in the international community. I hope this is something I have achieved in my text books and whenever I post answers to technical questions on the Internet. (The temptation to slip into creative writing is always present, but I try to avoid it.)

In the UK (at least in England, I’m assuming it’s the same in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland), the secondary education system has two English GCSEs: English Literature and English Language. The first studies set books and analyses the creative writing used within that work. The second includes writing fiction and comprehending pieces of creative writing, where the samples are taken from classic novels or from articles.

Both GCSEs emphasize creative writing skills. This is as it should be for the English Literature course, but the lack of a specific technical writing GCSE is a cause for concern. Firstly from the point of view of employers who are aiming for the Crystal Mark. They need to know the technical writing skills of job applicants, but they can’t tell this from the English Language GCSE. The second problem bothers me even more: the current system discriminates against students on the Autistic Spectrum, who may have a wide vocabulary, good spelling, punctuation and a firm understanding of grammar, but because they can’t understand sub-text, emotional responses and non-literal phrases they fail the English Language GCSE. The education system labels them as illiterate even if they have far better technical writing skills than their neurotypical peers who are able to pass the GCSE because they can understand sub-text and can write about emotions.

I’m not faulting the English teachers here. There are many good teachers who are aware of this discrimination, but they are constrained by the curriculum. However I have also heard arguments along the lines of ‘They need to learn how to understand sub-text and non-literal expressions in case they encounter it in their profession.’ This has no more sense than saying that a colour-blind person needs to learn how to distinguish between colours in case they enter a profession that requires that ability. It shows a basic lack of understanding of disabilities.

I believe that the curriculum should consist of three separate English GCSEs:

English Literature. (As it currently is.)

Creative Writing. (Much of what the current English Language GCSE entails.)

Technical English.

This would not only help to end the curriculum’s current discrimination against Autistic pupils but will also benefit business and technical sectors who need employees with technical writing skills.

July 26, 2018

Localisation

The chances are that you’re reading this in a web browser. Perhaps it has a menu bar along the top with words like ‘Bookmarks’ or ‘History’, or perhaps it has a hamburger style menu that appears when you click on a button with three horizontal lines. However you interact with an application, the instructions are provided in words or pictures (or a combination). Commonly known icons, such as a floppy disk or printer, are easy to understand for those familiar with computers, but more complex actions, prompts, and warning or error messages need to be written in words.

For example, if you want to check your email, there might be a message that says ‘1 unread email(s)’ or ‘2 unread email(s)’. If the software is sophisticated, it might be able to say ‘1 unread email’ or ‘2 unread emails’. Naturally, you’ll want this kind of information to be in a language you can understand. Another user may be using the same application in, say, France or Germany, in which case they’ll probably want the messages in French or German.

An application that supports localisation is one that is designed to allow such textual information to be displayed in different languages, and (where necessary) to format certain elements, such as dates or currency, according to a particular region. This support is typically provided in a file that contains a list of all possible messages, each identified by a unique key. Adding a new language is simply a matter of finding someone who can translate those messages and creating a new file with the appropriate name.

The recommended way of identifying a particular language or region is with an ISO code. The ISO 639-1 two-letter code is the most commonly used code to identify root languages, such as ‘en’ for English, ‘fr’ for French and ‘de’ for German. (Languages can also be identified by three-letter codes or numeric codes.) The language code can be combined with an ISO 3166 country code. For example, ‘en-GB’ indicates British English (so a printer dialogue box might ask if you want the ‘colour’ setting), ‘en-US’ indicates US English (‘color’) and ‘fr-CA’ indicates French Canadian (‘couleur’).

On Friday 20th July 2018, Paulo Cereda presented the newly released version 4.0 of his arara tool at the TeX User Group (TUG) 2018 conference in Rio de Janeiro. For those of you who have read my LaTeX books, I mentioned arara in Using LaTeX to Write a PhD Thesis and provided further information in LaTeX for Administrative Work. This very useful tool for automating document builds has localisation support for English, German, Italian, Dutch, Brazilian Portuguese, and — Broad Norfolk.

Wait! What was that?

Broad Norfolk is the dialect spoken in the county of Norfolk in East Anglia. There’s a video of Paulo’s talk available. If you find it a bit too technical but are interested in the language support, skip to around time-frame 18:50. Below are some screenshots of arara in action. (It’s a command line application, so there’s no fancy point and click graphical interface.)

Here’s arara reporting a successful job (converting the file test.tex to test.pdf) with the language set to Broad Norfolk:

For those who can’t see the image, the transcript is as follows:

Hold yew hard, ole partner, I'm gornta hev a look at 'test.tex'

(thass 693 bytes big, that is, and that was last chearnged on

07/26/2018 12:09:08 in case yew dunt remember).

(PDFLaTeX) PDFLaTeX engine ..... THASS A MASTERLY JOB, MY BEWTY

(Bib2Gls) The Bib2Gls sof....... THASS A MASTERLY JOB, MY BEWTY

(PDFLaTeX) PDFLaTeX engine ..... THASS A MASTERLY JOB, MY BEWTY

Wuh that took 1.14 seconds but if thass a slight longer than you

expected, dunt yew go mobbing me abowt it cors that ent my fault.

My grandf'ar dint have none of these pearks. He had to use a pen

and a bit o' pearper, but thass bin nice mardling wi' yew. Dew

yew keep a troshin'!

For comparison, the default English setting produces:

For those who can’t see the image, the transcript is as follows:

Processing 'test.tex' (size: 693 bytes, last modified: 07/26/2018

12:09:08), please wait.

(PDFLaTeX) PDFLaTeX engine .............................. SUCCESS

(Bib2Gls) The Bib2Gls software .......................... SUCCESS

(PDFLaTeX) PDFLaTeX engine .............................. SUCCESS

Total: 1.18 seconds

For a bit of variety, I then introduced an error that causes the second task (Bib2Gls) to fail. Here’s the Broad Norfolk response:

For those who can’t see the image, the transcript is as follows:

Hold yew hard, ole partner, I'm gornta hev a look at 'test.tex'

(thass 694 bytes big, that is, and that was last chearnged on

07/26/2018 12:23:42 in case yew dunt remember).

(PDFLaTeX) PDFLaTeX engine ..... THASS A MASTERLY JOB, MY BEWTY

(Bib2Gls) The Bib2Gls sof....... THAT ENT GORN RIGHT, OLE PARTNER

Wuh that took 0.91 seconds but if thass a slight longer than you

expected, dunt yew go mobbing me abowt it cors that ent my fault.

My grandf'ar dint have none of these pearks. He had to use a pen

and a bit o' pearper, but thass bin nice mardling wi' yew. Dew

yew keep a troshin'!

For comparison, the default English setting produces:

For those who can’t see the image, the transcript is as follows:

Processing 'test.tex' (size: 694 bytes, last modified: 07/26/2018

12:23:42), please wait.

(PDFLaTeX) PDFLaTeX engine .............................. SUCCESS

(Bib2Gls) The Bib2Gls software .......................... FAILURE

Total: 0.91 seconds

Here’s the help message in Broad Norfolk:

For those who can’t see the image, the transcript is as follows:

arara 4.0 (revision 1)

Copyright (c) 2012-2018, Paulo Roberto Massa Cereda

Orl them rights are reserved, ole partner

usage: arara [file [--dry-run] [--log] [--verbose | --silent] [--timeout

N] [--max-loops N] [--language L] [ --preamble P ] [--header]

| --help | --version]

-h,--help wuh, cor blast me, my bewty, but that'll tell

me to dew jist what I'm dewun rite now

-H,--header wuh, my bewty, that'll only peek at directives

what are in the file header

-l,--log that'll make a log file wi' orl my know dew

suffin go wrong

-L,--language that'll tell me what language to mardle in

-m,--max-loops wuh, yew dunt want me to run on forever, dew

you, so use this to say when you want me to

stop

-n,--dry-run that'll look like I'm dewun suffin, but I ent

-p,--preamble dew yew git hold o' that preamble from the

configuration file

-s,--silent that'll make them system commands clam up and

not run on about what's dewin

-t,--timeout wuh, yew dunt want them system commands to run

on forever dew suffin' go wrong, dew you, so

use this to set the execution timeout (thass in

milliseconds)

-V,--version dew yew use this dew you want my know abowt

this version

-v,--verbose thass dew you want ter system commands to hav'

a mardle wi'yew an'orl

For comparison, the default English setting produces:

For those who can’t see the image, the transcript is as follows:

arara 4.0 (revision 1)

Copyright (c) 2012-2018, Paulo Roberto Massa Cereda

All rights reserved

usage: arara [file [--dry-run] [--log] [--verbose | --silent] [--timeout

N] [--max-loops N] [--language L] [ --preamble P ] [--header]

| --help | --version]

-h,--help print the help message

-H,--header extract directives only in the file header

-l,--log generate a log output

-L,--language set the application language

-m,--max-loops set the maximum number of loops

-n,--dry-run go through all the motions of running a

command, but with no actual calls

-p,--preamble set the file preamble based on the

configuration file

-s,--silent hide the command output

-t,--timeout set the execution timeout (in milliseconds)

-V,--version print the application version

-v,--verbose print the command output

In case you’re wondering why Broad Norfolk was included, Paulo originally asked me if I could add a slang version of English as an Easter egg, but I decided to take advantage of this request and introduce Broad Norfolk to the international TeX community as it’s been sadly misrepresented in film and television, much to the annoyance of those who speak it. As far as we know, it’s the only application that includes Broad Norfolk localisation support. (If you know of any other, please say!)

Having decided to add Broad Norfolk, we needed to consider what code to use. The ISO 3166-1 set includes a sub-set of user-assigned codes provided for non-standard territories for in-house application use. These codes are AA, QM to QZ, XA to XZ, and ZZ. I chose ‘QN’ and decided it’s an abbreviation for Queen’s Norfolk, as the Queen has a home in Norfolk.

April 29, 2018

Turbot the Witch

I had an interesting encounter with a couple of children as I was heading back into the village after walking around the muddy footpaths and byways around the area. (This is not only setting the scenic background detail, but also noting that I might’ve had a slightly dishevelled and windswept appearance as a result.) In general, I find it a bit awkward when unknown children want to strike up a conversation as on the one hand I don’t want to encourage them to talk to strangers, but on the other hand I don’t want to appear rude, so when they called out a friendly greeting, I gave a friendly acknowledgement without breaking my stride, but the girl called me back.

‘Hello, whoever you are. Who are you?’ she asked.

‘I live in the village,’ I replied, non-committally. Since she seemed to require more detail, I added: ‘My son used to go to the village school.’

‘Is he So-and-so?’ she asked.

(I don’t think I ought to disclose names in a public post, so let’s just stick with So-and-so.)

‘No,’ I said. ‘My son’s grown up and has left school now.’

‘Are you So-and-so’s granny?’

‘No.’

‘So-and-so’s granny is 68.’

‘I’m not that old,’ I said. ‘I’m not even 50.’

‘Are you 49?’ the boy asked.

I could see that this was going to lead to a guessing game, and he was only two off, so I decided to just cut straight in there with the answer.

‘No, I’m 47.’

‘I hope you don’t mind me saying this,’ the boy said, in a very polite tone of voice, ‘but you look much older.’

‘Are you a witch?’ the girl asked.

‘No,’ I said, ‘but if I was a witch, I might not admit it.’

I’m not sure if they grasped the sub-text there: people aren’t always what they claim to be (or not be).

‘Do you know So-and-so?’ the girl asked, reverting the subject back to whoever he is, but apparently he’s a boy in their school.

‘No, I don’t know So-and-so, and I think you should be careful about talking to strangers.’

‘Are you a stranger? What’s your name?’

‘I have two names,’ I replied. ‘My real name is Nicola Cawley, but my writing name is Talbot.’

‘Turbot?’

‘No, Talbot.’

Clearly, they haven’t yet heard of a local village author of children’s stories that are charmingly illustrated by a talented artist from nearby Poringland.

‘If you’re a witch,’ the girl said, ‘you could turn me into a dog.’

‘Witches don’t exist,’ the boy said.

‘Well, either I’m not a witch or I don’t exist,’ I replied.

All those years studying mathematics haven’t been wasted. I can still apply logical reasoning in a conversation with kids. As I finally walked away, a voice called after me:

‘Goodbye, Whatever-your-name-is Turbot.’

So now I feel that Turbot the Witch has to appear in a story. Perhaps she should join Sir Quackalot, Dickie Duck, José Arara and friends. Sir Quackalot, for those of you who don’t know, started life in the TeX.SE chatroom in a little story containing TeX-related jokes to amuse my friend Paulo who likes ducks and is the creator of an application called arara, which means macaw in Portuguese. The story was called ‘Sir Quackalot and the Golden Arara.’ The image of Sir Quackalot on the left is created using the tikzducks package. The code is:

So now I feel that Turbot the Witch has to appear in a story. Perhaps she should join Sir Quackalot, Dickie Duck, José Arara and friends. Sir Quackalot, for those of you who don’t know, started life in the TeX.SE chatroom in a little story containing TeX-related jokes to amuse my friend Paulo who likes ducks and is the creator of an application called arara, which means macaw in Portuguese. The story was called ‘Sir Quackalot and the Golden Arara.’ The image of Sir Quackalot on the left is created using the tikzducks package. The code is:

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage[T1]{fontenc}

\usepackage{tikzducks}

\begin{document}

\begin{tikzpicture}

\begin{scope}[rotate=-15,shift={(-0.5,0.2)}]

\draw[fill=black!40]

(1,0.5) -- (0.2,0.5) -- (0, 0.55) -- (0.2,0.6) -- (1, 0.6) -- cycle;

\end{scope}

\duck[cape=darkgray,shorthair=darkgray]

\begin{scope}[rotate=-20,shift={(.25,0.25)}]

\draw[fill=black!50]

(0,1) .. controls (0.05, 0.57) and (0.23, 0.23) .. (0.5, 0)

.. controls (0.77, 0.23) and (0.95, 0.57) .. (1, 1)

.. controls (0.83, 0.9) and (0.67, 0.9) .. (0.5, 1)

.. controls (0.33, 0.9) and (0.07, 0.9) .. cycle;

\node[orange,at={(0.5,0.5)}] {\bfseries\large Q};

\end{scope}

\end{tikzpicture}

\end{document}Sir Quackalot next made an appearance in LaTeX for Administrative Work as the author of titles such as ‘The Adventures of Duck and Goose’, ‘The Return of Duck and Goose’ and ‘More Fun with Duck and Goose’ in one of the sample datasets that accompanies the textbook. The more adventurous reader can, in Exercise 12 (Chapter 4), try to programmatically fetch the titles from the database to typeset an invoice for José Arara’s book order.

The sample data also includes a list of people, such as Dickie Duck, Polly Parrot, Mabel Canary and (to test UTF-8 support) José Arara of São Paulo. At various times in the textbook, they are customers (as in the above invoice exercise), letter recipients (Chapter 3, typesetting correspondence), job applicants (Chapter 5, typesetting a CV), and members of the Secret Lab of Experimental Stuff (and their co-researchers in the Department of Stripy Confectioners) who have to write memos, press releases, and minutes. They also have to redact classified information, use hierarchical numbering in their terms and conditions, prepare presentations, a z-fold leaflet advertising their highly classified projects, and collaborate on documents.

Dickie Duck also moonlights as the author of ‘Oh No! The Chickens have Escaped!’ illustrated by José Arara, whose paintings bear an uncanny resemblance to digitally manipulated photos of my mum’s chickens. In Chapter 10, they have to create a postcard and design an advance information sheet to advertise the book.

Sir Quackalot reappears in my testidx package, which is designed for testing indexing applications with LaTeX. My original plan was to use dummy text, but I’ve grown bored of lorem ipsum and I wanted the first few paragraphs to be informative. I also needed the index to cover the full Basic Latin letter groups A, …, Z as well as some extended Latin characters commonly used in European languages, such as Ð (eth), Þ (thorn) and Ø. After five pages of filler text, I discovered that some of the letter groups were still missing, so I added the story of ‘Sir Quackalot and the Golden Arara’, which provided an extra page of text and conveniently helped with the rather sparse Q letter group. The code to produce the document is quite simple:

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{imakeidx}

\usepackage{testidx}

\makeindex

\begin{document}

\testidx

\printindex

\end{document}For those who don’t have a TeX distribution, here’s a PDF I made earlier. That example only has the Basic Latin groups. There’s a fancier example with hyperlinks, extended letter groups, digraphs (IJ, Ll, etc) and a trigraph (Dzs): source code and the final PDF created from it (using XeLaTeX and bib2gls).

So if you read my textbooks or manuals, watch out for a cameo from Turbot the Witch. What does she look like? I think tikzducks can supply the answer again:

So if you read my textbooks or manuals, watch out for a cameo from Turbot the Witch. What does she look like? I think tikzducks can supply the answer again:

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{tikzducks}

\begin{document}

\begin{tikzpicture}

\duck[witch=black!70,longhair=brown!60!gray,jacket=black!70,magicwand]

\end{tikzpicture}

April 17, 2018

Alternative History

![[The Fourth Protectorate]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1523992446i/25392738.png) I mentioned my pending novel The Fourth Protectorate in my earlier Crime and SF blog post. I also spoke briefly about it during Keith Skipper’s July 2017 monthly mardle in Radio Norfolk’s Matthew Gudgin’s Teatime Show. For those who are interested, here’s a little more information about the novel’s genre.

I mentioned my pending novel The Fourth Protectorate in my earlier Crime and SF blog post. I also spoke briefly about it during Keith Skipper’s July 2017 monthly mardle in Radio Norfolk’s Matthew Gudgin’s Teatime Show. For those who are interested, here’s a little more information about the novel’s genre.

The Fourth Protectorate is an alternative history with supernatural elements, but what actually is alternative history? It’s sometimes referred to as a ‘what if?’ genre. What if something happened in the past that caused subsequent events to diverge from real life? That something is the point of departure, and the subsequent events form an alternate timeline (or history). I think the most well-known (but not the earliest) alternative history story is probably Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle (first published in 1962). The point of departure in that case was the different outcome of an attempt to assassinate US President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In real life, Giuseppe Zangara tried to shoot Roosevelt in February 1933. The premise of The Man in the High Castle is what if Zangara had succeeded? In real life, Roosevelt felt so strongly about supporting the Allies during WWII that he broke tradition and stood for a third term. The alternative timeline has Roosevelt replaced by an isolationist who keeps the USA out of the war, which changes the outcome.

The ‘what if so-and-so died at an earlier point in time?’ premise is a common point of departure. The reverse ‘what if so-and-so didn’t die?’ is also used (to comic effect with Red Dwarf and rather more seriously with Star Trek: The Original Series). Other points of departure can be somewhat vaguer, such as ‘what if a battle was lost instead of won?’ (as with Len Deighton’s SS-GB, where the Battle of Britain was lost), or the point of departure can be something seemingly trivial (‘for want of a nail’).

In the case of The Fourth Protectorate, which is set from 1984 to 1995, the principle point of departure is the Brighton Bomb. What if it had killed the Prime Minister and the entire Cabinet? The event occurs in the chapter that’s rather unimaginatively called ‘Point of Departure’, and you can accept that as the actual point of departure if you like but, whilst thinking about the exact differences between the alternative timeline of the story and real life, I came to the conclusion that the real point of departure occurs earlier, but the differences are much subtler until 1984 is reached. So what actually causes the divergence?

In the world of The Fourth Protectorate, the supernatural exists, although most people aren’t aware of it, but there’s a constant conflict between good and evil. One side is trying to make the world a better place and the other is trying to ruin it. Both sides have some ability to predict future events, but neither side can interfere with free will. They can, however, plant suggestions in people’s minds to influence outcomes. People are free to choose to follow or ignore those suggestions, but those who have a natural predisposition towards the suggestion or those who have a weak will are more likely to comply. So when is the actual point of departure?

What if during the Blitz a bomb toggle was operated a fraction later? A minor suggestion planted in the airman’s mind that causes a momentary delay. The dispersal pattern changes, a different set of buildings are destroyed and a different set of people die. The global outcome is unchanged, but minor deviations start to occur that can lead up to a bomb or some people being in a slightly different location a few decades later. It may also have led to more significant changes. The Prime Minister and other ministers are never named in the book, so they may not be the same as in our real timeline.

So the principle point of departure is the ‘what if so-and-so died?’ type but the actual point of departure is a seemingly insignificant change that had a knock-on effect. This conveniently means that any minor discrepancies from real life at the start of the book now have an explanation (such as the reason why famous/infamous people who lived in that region in real life don’t appear to exist in the story).

One of the interesting things I’ve encountered while writing the novel is the background research to refresh my memory of the 1980s (and the previous decade). It’s reminded me of just how volatile that era was. There were definitely a lot of ‘what if?’ moments.

August 2, 2017

The Private Enemy Giveaway

Following on from my previous post about Norfolk, I’ve set up a GoodReads giveaway for the second edition of The Private Enemy from 18 Aug to 11 Sep, 2017. This giveaway is only open to entrants from the United Kingdom to reduce postage costs, but I hope to run another at a later date that’s more widely available.

Following on from my previous post about Norfolk, I’ve set up a GoodReads giveaway for the second edition of The Private Enemy from 18 Aug to 11 Sep, 2017. This giveaway is only open to entrants from the United Kingdom to reduce postage costs, but I hope to run another at a later date that’s more widely available.

For those of you who missed my interview on Keith Skipper’s monthly mardle on Radio Norfolk’s Matthew Gudgin’s Teatime Show, there’s still a little time left to catch up on BBC iPlayer. (It’s available up to four weeks after the broadcast date.) I was on during the last hour of the three hour episode New money for “research school” (from around time frame 02:07:30).