Stephen W. Hiemstra's Blog, page 9

July 6, 2025

Oración Evangélica

Por Stephen W. Hiemstra

Dios Todopoderoso,

Tuyos son toda la alabanza y el honor, el poder y el dominio, la verdad y la justicia, porque en tu ley nos bendices y nos maldices según merecemos, pero en tu Evangelio por Jesucristo nos ofreces un camino de redención.

Confesamos que somos tentados a pecar, a transgredir tu ley y a cometer toda clase de iniquidades. Perdónanos. Ayúdanos a hacerlo mejor.

Damos gracias por las muchas bendiciones de esta vida: nuestra creación, nuestras familias, nuestra salud y el trabajo útil que realizar. Sobre todo, damos gracias por nuestra salvación en Jesucristo.

Con el poder de tu Espíritu Santo, atráenos hacia ti. Abre nuestros corazones, ilumina nuestras mentes, fortalece nuestras manos en tu servicio.

En el nombre de Jesús, Amén.

Oración Evangélica

Vea También:

Una Guía Cristiana a la Espiritualidad

Vida en Tensión

Otras Formas de Interactuar en Línea:

Sitio Web del Autor: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Sitio Web del Editor: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Boletín Informativo en: https://bit.ly/bugs_25 , Signup

The post Oración Evangélica appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

July 4, 2025

Deuteronomic Cycle

We love because he first loved us.

(1 John 4:19)

By Stephen W. Hiemstra

While the stories of Abraham and of the Exodus offer positive responses of faith of at least a remnant, the Deuteronomic cycle given by Moses (Deut 30:1-3) and cited by Brueggemann (2016, 59) offers an alternative response. Those who refuse faith garner the curse of scattering, an echo of the curse of Cain (Gen 3:14). Here the pattern is: collective sin, scattering and enslavement, crying out to the Lord, and the sending of a deliverer. This pattern is repeated throughout the Old and New Testaments. All are called; not all respond. One way or the other, through the instrumentality of the Holy Spirit: “To me every knee shall bow, every tongue shall swear allegiance.” (Isa 45:23)

Cycle in Judges

The Deuteronomic cycle is especially prominent in the Book of Judges. Probably the most familiar example is the story of Gideon. The cycle starts with sin and the resulting curse. In Judges 6:1 we read: “The people of Israel did what was evil in the sight of the LORD, and the LORD gave them into the hand of Midian seven years.” (Jdg 6:1) After being persecuted by the Midianites, the people cry out to the Lord in verse 6 and the Lord sends an angel to call on Gideon, who is busy hiding wheat from the Midianites in a winepress (verse 11).

Gideon then assembles an elite team three hundred men against the army of the Midianites described as too numerous to number like locusts ravaging the land. Responding to a vision in a dream, this team woke the Midianites in the middle of the night with trumpets and torches. Frightened in the night, the Midianites began slaughtering each other in the dark (Jdg 7:22).

In this manner, the Lord freed the Israelite people from the oppression of the Midianites and brought them the joy of salvation.

Cycle in Psalms

The Deuteronomic cycle usually applies to the people of Israel as a whole and brought salvation from oppression. Following the pattern established in Psalm 18, however, Psalm 116 applies salvation to the individual rather than the nation.

This should not come as a surprise. Wenham (2012, 7) writes: “I have called it Psalms as Torah out of my conviction that the psalms were and are vehicles not only of worship but also of instruction, which is the fundamental meaning of Torah.” If the Psalms serve as a commentary on the Books of the Law, then they should show how to apply things like the Deuteronomic cycle.

Note that the Deuteronomic cycle starts with the commission of sin—the curses of Deuteronomy 28 are a consequence of disobeying the Mosaic covenant. Thus, the cycle can once again be summarized as committing sin, earning the curse, crying out to the Lord, and, then, being redeemed.

The first four verses of Psalm 116 tell his story:

“I love the LORD, because he has heard my voice and my pleas for mercy. Because he inclined his ear to me, therefore I will call on him as long as I live. The snares of death encompassed me; the pangs of Sheol laid hold on me; I suffered distress and anguish. Then I called on the name of the LORD: O LORD, I pray, deliver my soul!”

Verse one here explains his joy: “I love the LORD, because he has heard my voice and my pleas for mercy.” Actually, English translations add the word, LORD, which does not appear in the original Hebrew or in the Septuagint Greek. The Hebrew simply reads: I have loved because he has heard my voice… We see an echo of the original Hebrew in John’s first letter: “We love because he first loved us.” (1 John 4:19)

Moving on to verse two, the psalmist reiterates the importance of being heard and takes a vow: “Because he inclined his ear to me, therefore I will call on him as long as I live.” This vow is interesting because if you pray or sing this psalm, as is the custom, you also repeat this vow.

Why is listening so important to the psalmist? Verse three reiterates the answer three times: “The snares of death encompassed me; the pangs of Sheol laid hold on me; I suffered distress and anguish.” In other words, death had surrounded me; hell had opened its doors to pull me in; and I was terrified. The repetition assures us that the psalmist’s vows in verse two are not to be taken lightly.

Verse four then closes the loop by returning to the second half of verse one. Verse one talks of “pleas for mercy, while verse four cites the psalmist’s actual prayer: “O LORD, I pray, deliver my soul!”

So what brings joy to the psalmist? The Lord rescued him from death. Commentators believe Psalm 116 to be a crib notes version of Psalm 18 where King David recounts his own brush with death. Even more bone-crushing details can be found in 2 Samuel 22.

New Testament Cycle

Psalm 116’s personalized the Deuteronomic cycle and directly anticipated the New Testament and our salvation in Christ. In fact, if Jesus and the disciples sang Psalm 116 after the Last Supper, as was the custom during Passover, they took these very same vows and, in the resurrection, Jesus experienced God’s deliverance. Our redemption in Christ follows this same pattern. We sin; we get into trouble; we ask for forgiveness; Christ offers us redemption.

The key to understanding this parallel is to see sin as a form of oppression. We all experience besetting sins—addictions small and great–that we cannot shake on our own. If gluttony is one of the seven deadly sins, it is also a besetting sin that can destroy our self-esteem, ruin our health, and undermine our relationships. Just like the Midianites oppressed Israel, we can be oppressed by besetting sins and we need to cry out to the Lord for our forgiveness and salvation.

References

Brueggemann, Walter. 2016. Money and Possessions. Interpretation series. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press.

Wenham, Gordon J. 2012. Psalms as Torah: Reading Biblical Song Ethically. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic.

Deuteronomic Cycle

Also see:

The Face of God in the Parables

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/bugs_25, Signup

The post Deuteronomic Cycle appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

El Ciclo Deuteronómico

Nosotros amamos porque El nos amó primero.

(1 Juan 4:19)

Por Stephen W. Hiemstra

Si bien las historias de Abraham y del Éxodo ofrecen respuestas positivas de fe de al menos un remanente, el ciclo Deuteronómico dado por Moisés (Deut 30:1-3) y citado por Brueggemann (2016, 59) ofrece una respuesta alternativa. Aquellos que rechazan la fe reciben la maldición de la dispersión, un eco de la maldición de Caín (Gén 3,14). Aquí Este patrón se repite a lo largo del Antiguo y del Nuevo Testamento. Todos son llamados; no todos responden. De una manera u otra, a través de la instrumentalidad del Espíritu Santo, ¨Que ante mí se doblará toda rodilla, y toda lengua jurará lealtad.¨ (Isa. 45:23)

Ciclo en Jueces

El Ciclo Deuteronómico es especialmente prominente en el Libro de los Jueces. La historia de Gedeón es un ejemplo conocido. El ciclo comienza con el pecado y la maldición resultante. Leemos: “Entonces los Israelitas hicieron lo malo ante los ojos del SEÑOR, y el SEÑOR los entregó en manos de Madián por siete años.” (Jdg 6:1) Después de ser perseguidos por los madianitas, el pueblo clama al Señor en el versículo 6 y el Señor envía un ángel para llamar a Gedeón, quien está ocupado escondiendo trigo de los madianitas en un lagar (versículo 11).

Gedeón entonces reúne a trescientos hombres para luchar contra un ejército de madianitas descritos como langostas que asolaban la tierra, demasiado numerosos para ser contados. Respondiendo a una visión en un sueño, este equipo despertó a los madianitas en medio de la noche con trompetas y antorchas. Atemorizados, los madianitas comenzaron a matarse unos a otros en la oscuridad (Jue 7:22). De esta manera, el Señor liberó al pueblo israelita de la opresión de los madianitas.

Ciclo en los Salmos

El ciclo deuteronómico generalmente se aplica al pueblo de Israel en su conjunto y trae salvación de la opresión. Sin embargo, siguiendo el patrón establecido en el Salmo 18, el Salmo 116 aplica la salvación al individuo y no a la nación. El ciclo se puede resumir una vez más como cometer pecado, ganarse la maldición, clamar al Señor y luego ser redimido.

Los primeros cuatro versículos del Salmo 116 cuentan su historia:

“Amo al SEÑOR, porque oye mi voz y mis súplicas. Porque a mí ha inclinado su oído; Por tanto Le invocaré mientras yo viva. Los lazos de la muerte me rodearon, Y los terrores del Seol vinieron sobre mí; Angustia y tristeza encontré. Invoqué entonces el nombre del SEÑOR, diciendo: Te ruego, oh SEÑOR: salva mi vida.”

El primer versículo aquí explica su alegría: “Amo al Señor, porque oye mi voz y mis súplicas. Porque a mí ha inclinado su oído.” De hecho, las traducciones españolas añaden la palabra SEÑOR, que no aparece en el hebreo original ni en el griego de la Septuaginta. El hebreo simplemente dice: “Yo he amado porque ha escuchado mi voz.” Escuchamos un eco del hebreo original en la primera carta de Juan: “Nosotros amamos, porque Él nos amó primero.” (1 Juan 4:19)

Pasando al versículo dos, el salmista reitera la importancia de ser escuchado y hace un voto: “Porque a mí ha inclinado su oído; por tanto le invocaré mientras yo viva.” Este voto es interesante porque si rezas o cantas este salmo, como es la costumbre, también repites este voto.

¿Por qué es tan importante para el salmista escuchar? Versículo tres reitera la respuesta tres veces: ¨Los lazos de la muerte me rodearon, Y los terrores del Seol vinieron sobre mí; Angustia y tristeza encontré.¨ En otras palabras, la muerte me había rodeado; el infierno había abierto sus puertas para atraerme; y yo estaba aterrorizado. La repetición nos asegura que los votos del salmista en el versículo dos no deben tomarse a la ligera.

El cuarto verso luego cierra el ciclo volviendo a la segunda mitad del verso uno. El versículo uno habla de súplicas de misericordia, mientras que el versículo cuatro cita la oración real del salmista: “Te ruego, oh SEÑOR: salva mi vida.” Nótese que nunca se nos dice qué pecado cometió el salmista que precipitó estos acontecimientos: el pecado se infiere, no se declara.

¿Qué le trae alegría al salmista? El Señor lo rescató de la muerte. Los comentaristas creen que el Salmo 116 es una versión de notas de cuna del Salmo 18, donde el rey David relata su propio encuentro con la muerte (2 Sam 22).

Ciclo del Nuevo Testamento

El Salmo 116 personalizó el Ciclo Deuteronómico y anticipó nuestra salvación en Cristo. De hecho, si Jesús y los discípulos cantaron el Salmo 116 después de la Última Cena, como era costumbre durante la Pascua, tomaron estos mismos votos y, en la resurrección, Jesús experimentó la liberación de Dios.

La clave para entender este paralelo es ver el pecado como una forma de opresión. Todos experimentamos pecados que nos acosan—adicciones pequeñas y grandes—que no podemos librarnos por nuestros propios medios. Si la gula es uno de los siete pecados capitales, también es un pecado acosador que puede destruir nuestra autoestima, arruinar nuestra salud y minar nuestras relaciones. Así como los madianitas oprimieron a Israel, nosotros podemos ser oprimidos por pecados que nos acosan, y necesitamos clamar al Señor por nuestro perdón y salvación.

El Ciclo Deuteronómico

Vea También:

Una Guía Cristiana a la Espiritualidad

Vida en Tensión

Otras Formas de Interactuar en Línea:

Sitio Web del Autor: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Sitio Web del Editor: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Boletín Informativo en: https://bit.ly/bugs_25 , Signup

The post El Ciclo Deuteronómico appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

July 1, 2025

Seger Reads Screenplays Deeply

Linda Seger. 2010. Making a Good Script Great. Los Angles: Silman-James Press.

Review by Stephen W. Hiemstra

The best editors that I have engaged have been script consultants. Their critiques of my scripts, called treatments,

“include: (1) your log line, which is the basis of your pitch, (2) the premise of your story, (3) your main characters, and (4) a very brief synopsis of the story itself.” (Baehr 2011, 190)

Linda Seger was a pioneer in the field of script consulting based on work gathered in 1976 in her dissertation.

In her book, Making a Good Script Great, Linda Seger writes:

“In my many years of experience, I’ve seen the same kinds of script problems occur again and again. Problems with exposition. Problems with structure, with shaping the story. Problems with momentum that can make the difference between a sale and another rejection letter, between commercial success and box-office failure.” (xix)

This book “takes you through the whole screenwriting process—from initial concept through final rewrite—providing specific methods that will help you craft tighter, stronger, and more salable scripts.” (back cover)

Background and OrganizationLinda Seger graduated from Colorado College, received a Masters of Arts from the Pacific School of Religion on Religion in Arts, and a doctorate from the affiliated Graduate Theological Union. She is an author and screenwriter.

She writes in fourteen chapters:

Gathering ideasThe Three-act structure: Why You Needs It and What to Do with ItWhat do Subplots Do?Act Two—How to Keep it MovingEstablishing a Point of ViewCreating the SceneCreating a Cohesive ScriptMaking It CommercialBalancing Images and DialogueFrom Motivation to Goal: Finding Your Character SpineFinding the ConflictCreating Multidimensional and Transformational CharactersCharacter FunctionsA Case Study: Writer Paul Haggis in His Own Words (ix)These chapters are proceeded by acknowledgments, a preface, and Introduction, and followed by an index and an author about description.

Good how-to books are filled with helpful advice. Two areas that promoted edits to my current screenplay, Jeez and the Gentile, were focused on subplots and moving the Second Act along.

SubplotsI have heard the term, subplot, over and over, but I have never known what to make of it. Seger writes:

“Subplots are usually relationship stories, whereas the plot is usually an action story… The plot and the subplot then interweave. A good subplot not only pushes the plotline, it also interests it.” (50)

Seger goes on to explain:

“Just as the plot has a beginning, a middle, and an end, so too does a subplot. A good subplot also has a clear setup, turning points, developments, and a payoff at the end.” (53)

Seger uses the film, Good as it Gets (1997), to highlight subplots involving each of the characters in the film (55-60). The whole film moves forwards with these relational subplots. For example, who would imagine from the opening scenes that Melvin would turn out to love the dog or offer Simon an empty room to stay in or, for that matter, get the girl?

In my own screenplay, I realized that the climax to the relationship between two characters Tom and Leo, was implied, not stated, and the foundation of their companionship was also unstated in a short, descriptive scene. In my rewrite, I added dialog to this scene that acknowledged their commonality and they shared an emotional moment together rather than simply acting together in support of the climax to the main plot. The addition was only a couple of paragraphs, but it climaxed the subplot just before the climax to the main plot much like in action movies the hero always manages to say goodbye to his friends before the finale.

Second Act MovementAct Two in the three Act screenplay is where most of the action in a film occurs. In a 120-minute film, 60 minutes take place in Act Two with Act One and Three taking 30 minutes each. How does the author manage to keep the momentum moving?

Seger focuses on cause and effect, not speed. She writes:

“Momentum [is] the product of action-reaction scenes…An action point is a dramatic event (an action, not dialogue) that causes a reaction and, thus, drives the story forward. The reaction, in turn, usually causes another action.” (67)

This is not just another chase seen or another character gets shot. Breaking the cause-and-effect sequence are obstacles.

Seger lists complications, reversals, and twists as specific types of obstacles.

“A complication is an action point that doesn’t pay off immediately.” (72) In Tootsie (1982) Michael gets an acting job posing as a woman, but complications arise when he falls in love with a co-worker, Dorothy.

“The reversal…changes a story’s direction by 180 degrees.” (73) In Changeling (2008) Christine is told that her son, who has been kidnapped, has been found, but she learns that the boy found is not her son. However, this reversal makes the story because the boy found leads the authorities to her son.

A twist…pushes a story in a new direction because it reverses expectations.” (74) In Sixth Sense (1999) the child psychologist protagonist meets a patient who sees dead people, doesn’t believe him, but, in the end, we learn that the psychologist himself is actually dead, but he doesn’t know it—and neither do we. This twist sticks in your mind and makes the film a hit.

These obstacles to progress in resolving the plot provide detours that many times add color and real life to a story.

AssessmentLinda Seger in Making a Good Script Great has written a classic gem. Ron Howard, who famously acted as a teen in Happy Days (1974-84), wrote that he consults this book before each new film project that he directs. I believe it. Authors, screenwriters, and directors should read this book and be conversant in its contents.

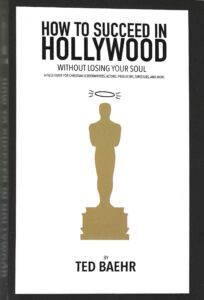

ReferencesTed Baehr. 2011. How to Succeed in Hollywood without Losing Your Soul: A Field Guide to Christian Screenwriters, Actors, Producers, Directors, and More. Camilla, CA: Movieguide Publishing.

Seger Reads Screenplays DeeplyAlso see:Books, Films, and MinistryOther ways to engage online:Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/bugs_25, Signup

The post Seger Reads Screenplays Deeply appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

June 30, 2025

Transitions: Monday Monologues (podcast), June 30, 2025

By Stephen W. Hiemstra

This morning I will share a prayer and reflect on the Exodus, Wandering, and Entry. After listening, please click here to take a brief listener survey (10 questions).

To listen, click on this link.

Hear the words; Walk the steps; Experience the joy!

Transitions: Monday Monologues (podcast), July 31, 2023

Also see:

The Face of God in the Parables

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/bugs_25, Signup

The post Transitions: Monday Monologues (podcast), June 30, 2025 appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

June 29, 2025

Wanderer’s Prayer

By Stephen W. Hiemstra

Almighty Father,

All praise and honor, power and dominion, truth and justice are yours because you remain with us during our painful transitions sheltering us from harm when we are most vulnerable.

Forgive us when we are not our best selves, letting others down and not living into our faith.

Thank you for your divine presence, faithful guidance, and protection when other friends fail us and we find ourselves in confusing times.

In the power of your Holy, help us to lean into our faith, living into our best selves, and listening to your faithful nudges. May we always find ourselves among your faithful remnant.

In Jesus’ precious name, Amen.

Wanderer’s Prayer

Also see:

The Face of God in the Parables

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/bugs_25, Signup

The post Wanderer’s Prayer appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

Oración de Errante

Por Stephen W. Hiemstra

Padre Todopoderoso,

Toda la alabanza y el honor, el poder y el dominio, la verdad y la justicia son tuyos porque permaneces con nosotros durante nuestras dolorosas transiciones, protegiéndonos del daño cuando somos más vulnerables.

Perdónanos cuando no damos lo mejor de nosotros mismos, decepcionamos a otros y no vivimos según nuestra fe.

Gracias por tu presencia divina, tu guía fiel y tu protección cuando otros amigos nos fallan y nos encontramos en momentos confusos.

Con el poder de tu Espíritu Santo, ayúdanos a alejarnos de nuestro ser natural y pecaminoso y a acercarnos a nuestro ser nuevo y fiel, y a escuchar tus fieles empujoncitos. Que siempre podamos encontrarnos entre tu remanente fiel.

En el precioso nombre de Jesús, Amén.

Oración de Errante

Vea También:

Una Guía Cristiana a la Espiritualidad

Vida en Tensión

Otras Formas de Interactuar en Línea:

Sitio Web del Autor: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Sitio Web del Editor: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Boletín Informativo en: https://bit.ly/bugs_25 , Signup

The post Oración de Errante appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

June 27, 2025

Exodus, Wandering, and Entry

Then he said, Your name shall no longer be called Jacob,

but Israel, for you have striven with God and with men,

and have prevailed.

(Gen 32:28)

By Stephen W. Hiemstra

The story of Abram serves as a introduction, precedent, or prequel to the story of Moses, who is the author of both. Savage (1996, 84-85) might describe it as a rehearsal story—a story from the past with current meaning. Due to the lengthy details given in the Abram narrative, we can intuit that Abram’s story had obvious meaning for Moses.

As the people of Israel left Egypt, they traveled to a land already promised to their ancestors, starting with Abram. But it was more than just land. Abram traveled to the Promised Land overcoming many obstacles obeying God’s command. Likewise, the story of Joseph, Abram’s great grandson, served to explain why they had become slaves in Egypt (Gen 37) and why their slavery was illegitimate (Exod 1:8). The stories in Genesis and Exodus are not randomly conceived.

The story of Moses begins with an enigmatic tale about recalcitrant midwives. Today we might describe their action as being faithful to the nudge of the Holy Spirit because they feared God more than the wrath of Pharaoh (Exod 1:17). God rewarded their faithfulness: “And because the midwives feared God, he gave them families.” (Exod 1:21) The text implies that they may have previously been barren or, at least, unable to children.

Faithful Midwives

The recalcitrance of the midwives serves as a bridge between the stories of Abram and Moses. Pharaoh’s attempt to kill Hebrew boys stood as an impediment to God’s promise to Abram that: “I will make of you a great nation.” (Gen 12:2) Once the nation of Israel has grow in Egypt from an extended family into a nation, the story of Moses transports them to the Promised Land to accomplish God’s promise to Abram who now is truly Abraham “The father of a multitude of nations.” (Gen 17:5)

Moses’ Call

Moses’ journey of faith did not have a promising start. Abandoned by his mother on the Nile in a basket, adopted by Pharaoh’s daughter, and raised as prince of Egypt (Exod 2:3-10). The first thing we learn about Moses as a young man is that he murdered an Egyptian and had to flee for his life to the deserts of Midian, where he lived the life of a shepherd (Exod 2:12-16). It was from the desert that God called Moses from the burning bush (Exod 3).

Consider God’s instructions to Moses: “Come, I will send you to Pharaoh that you may bring my people, the children of Israel, out of Egypt.” (Exod 3:10) It would not be easy to return to Egypt, having murdered an Egyptian, and being already known within the household of Pharaoh. Imagine a convict returning to his hometown as a pastor, having been sent to prison for murder. Moses was not a credible witness among the Egyptians or his fellow Hebrews.

Transition from Jacob to Israel

Strife marked Jacob’s transition to faith (Gen 32:28). The same strife marked Israel’s departure from Egypt, sojourn in the desert, and entry into the Promised Land. It may have taken forty days for Moses to lead the people of Israel out of Egypt, but it took forty years to get the Egypt of out of the people (Bridges 2003, 43).

The three-way transition of faith is defined as a change broken up into three emotional phases required. By contrast, a change simply describes the difference between an old state and a new one.

In the first phase, change is forced on you, but your attention focuses on the things given up. In this first phase the people of Israel say to Moses: “Is it because there are no graves in Egypt that you have taken us away to die in the wilderness?” (Exod 14:11) Then, they complained about food: “We remember the fish we ate in Egypt that cost nothing, the cucumbers, the melons, the leeks, the onions, and the garlic.” (Num 11:5)

The second phase is the desert experience where one learns to depend on God (or not). Uncertainty and division mark this phase, but it is also a time of great opportunity for those who keep their heads in the midst of chaos. Consider the response of 10 out of 12 of the spies sent into the Promised Land: “And there we saw the Nephilim (the sons of Anak, who come from the Nephilim), and we seemed to ourselves like grasshoppers, and so we seemed to them.” (Num 13:33) For their lack of faith, God cursed the unfaithful among Israel to return to and die in desert over the next forty years (Num 14:26-33) Only Joshua and Caleb, who returned with a faithful report and were willing to rely on God, would enter the Promised Land (Num 14:6-9).

The final phase arises once plans are set and the light at the end of the tunnel comes into view. In Joshua, we read:

“After the death of Moses the servant of the LORD, the LORD said to Joshua the son of Nun, Moses’ assistant, Moses my servant is dead. Now therefore arise, go over this Jordan, you and all this people, into the land that I am giving to them, to the people of Israel.” (Josh 1:1-2)

For the people of Israel to possess the Promised Land, they must take it from the current residents. Joshua, who had been Moses’ right-hand man and leader of the military, was the ideal one to lead this effort (Exod 17:9).

Following the desert experience, the people of Israel were tough enough to pursue the path that God laid before them. The three-way transition—exodus, wandering, and entry—is not unlike a hospital visit—affliction, treatment, and recovery— or a college education—application, classes, and graduation. In each case, the middle of the transition is the hardest and, frequently, the most rewarding.

Faith does not come without travail. It is in this travail that we are open to the Holy Spirit, even if, as among the Hebrew spies, it is only a faithful remnant.

References

Bridges, William. 2003. Managing Transition: Making the Most of Change. Cambridge: Da Capo Press.

Savage, John. 1996. Listening and Caring Skills: A Guide for Groups and Leaders. Nashville: Abingdon Press.

Exodus, Wandering, and Entry

Also see:

The Face of God in the Parables

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/bugs_25, Signup

The post Exodus, Wandering, and Entry appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

Éxodo, Errante, y Entrada

Y el hombre dijo: Tu nombre ya no será Jacob,

sino Israel (El que lucha con Dios),

porque has luchado con Dios y con los hombres,

y has prevalecido.

(Gen 32:28)

Por Stephen W. Hiemstra

La historia de Abram sirve como introducción a la historia de Moisés, quien es el autor de ambas. Por su extensión, podemos intuir que la historia de Abram y las que le siguieron tuvieron un significado especial para Moisés.

Cuando el pueblo de Israel salió de Egipto, viajó a una tierra ya prometida a sus antepasados, comenzando con Abram. Pero era más que sólo tierra. Abram superó muchos obstáculos al obedecer el mandato de Dios. Del mismo modo, la historia de José, bisnieto de Abram, sirvió para explicar por qué el pueblo de Israel se había convertido en esclavo en Egipto (Gén 37) y por qué su esclavitud era ilegítima (Éxodo 1:8). Las historias del Génesis y del Éxodo no fueron concebidas al azar, sino que sirvieron para ofrecer la esperanza de que la generación actual enfrentaría y superaría muchos obstáculos.

La historia de Moisés comienza con un relato enigmático sobre parteras recalcitrantes.

Hoy podríamos describir su acción como fidelidad al impulso del Espíritu Santo porque temían a Dios más que la ira del Faraón (Éxodo 1:17). Dios recompensó su fidelidad: ¨Y por haber las parteras temido a Dios, el prosperó sus familias.¨ (Éxodo 1:21)

El texto implica que es posible que anteriormente fueran estériles o, al menos, incapaces de tener hijos.

Parteras Fieles

La reticencia de las parteras sirve de puente entre las historias de Abram y Moisés. El intento del faraón de matar a los niños hebreos fue un impedimento para la promesa de Dios a Abram: ¨Haré de ti una gran nación¨ (Gén 12:2). Una vez que la nación de Israel creció en Egipto, pasando de ser una familia extensa a una nación, la historia de Moisés los transporta a la Tierra Prometida para cumplir la promesa de Dios a Abram, quien ahora es verdaderamente Abraham, ¨Padre de Multitud¨ (Gén 17:5).

El Llamado de Moisés

El camino de fe de Moisés no tuvo un comienzo prometedor. Fue abandonado por su madre en el Nilo en una cesta, adoptado por la hija del Faraón y criado como príncipe de Egipto (Éxodo 2:3-10). Lo primero que aprendemos sobre Moisés cuando era joven es que asesinó a un egipcio y tuvo que huir para salvar su vida a los desiertos de Madián, donde vivió la vida de un pastor (Éxodo 2:12-16). Fue desde el desierto que Dios llamó a Moisés desde la zarza ardiente (Éxodo 3).

Considere las instrucciones de Dios a Moisés: ¨Ahora pues, ven y te enviaré a Faraón, para que saques a mi pueblo, a los Israelitas, de Egipto.¨ (Exod 3:10) No sería fácil regresar a Egipto, después de haber asesinado a un egipcio y siendo ya conocido dentro de la casa del Faraón. Imaginemos a un convicto que regresa a su ciudad natal como pastor, después de haber sido enviado a prisión por asesinato. Moisés no fue un testigo creíble entre los egipcios ni entre sus compatriotas hebreos.

Transición de Esclavo a Libre

La salida de Israel de Egipto, su estancia en el desierto y su entrada a la Tierra Prometida marcaron una importante transición de fe. Puede que a Moisés le haya llevado cuarenta días sacar al pueblo de Israel de Egipto, pero le tomó cuarenta años de aceptar su identidad del pueblo como Israelis (Bridges 2003, 43).

Esta tres-manera transición de fe se define como un cambio dividido en las tres fases emocionales requeridas. Por el contrario, un cambio simplemente describe la diferencia entre un estado antiguo y uno nuevo.

En la primera fase, se te impone el cambio, pero tu atención se centra en las cosas que renunciaste. En esta primera fase, el pueblo de Israel le dijo a Moisés: ¨¿Acaso no había sepulcros en Egipto para que nos sacaras a morir en el desierto?¨ (Exod 14:11) Luego se quejaron de la comida: ¨Nos acordamos del pescado que comíamos gratis en Egipto, de los pepinos, de los melones, los puerros, las cebollas y los ajos.¨ (Num 11:5)

La segunda fase es la experiencia del desierto donde se aprende a depender de Dios (o no). La incertidumbre y la división marcan esta etapa, pero también fue un momento de grandes oportunidades para quienes mantuvieron la cabeza fría en medio del caos. Consideremos la respuesta de diez de los doce espías enviados a la Tierra Prometida: ¨Vimos allí también a los gigantes (los hijos de Anac son parte de la raza de los gigantes); y a nosotros nos pareció que éramos como langostas; y así parecíamos ante sus ojos.¨ (Num 13:33) Por su falta de fe, Dios maldijo a los infieles entre Israel para que regresaran y murieran en el desierto durante los siguientes cuarenta años (Núm14:26-33). Sólo Josué y Caleb, quienes regresaron con un informe fiel y estuvieron dispuestos a confiar en Dios, entrarían en la Tierra Prometida (Núm 14:6-9).

La fase final surge una vez que se han establecido los planes y aparece la luz al final del túnel. En Josué leemos:

¨Después de la muerte de Moisés, siervo del SEÑOR, el SEÑOR habló a Josué, hijo de Nun, y ayudante (ministro) de Moisés, y le dijo: Mi siervo Moisés ha muerto. Ahora pues, levántate, cruza este Jordán, tú y todo este pueblo, a la tierra que Yo les doy a los Israelitas.¨ (Jos 1:1-2)

Para que el pueblo de Israel posea la Tierra Prometida, debe arrebatársela a los residentes actuales. Josué, quien había sido la mano derecha de Moisés y líder del ejército, era el ideal para liderar este esfuerzo (Éxodo 17:9).

Después de la experiencia del desierto, el pueblo de Israel fue lo suficientemente fuerte como para seguir el camino que Dios puso ante ellos. La tres-manera transición—éxodo, estancia en desierto, y entrada—no es muy distinta a una visita al hospital—aflicción, tratamiento y recuperación—o a una educación universitaria—solicitud, clases y graduación). En cada caso, la parte intermedia de la transición es la más difícil y, con frecuencia, la más gratificante.

Éxodo, Errante, y Entrada

Vea También:

Una Guía Cristiana a la Espiritualidad

Vida en Tensión

Otras Formas de Interactuar en Línea:

Sitio Web del Autor: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Sitio Web del Editor: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Boletín Informativo en: https://bit.ly/bugs_25 , Signup

The post Éxodo, Errante, y Entrada appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

June 24, 2025

Baehr on Film Industry: Look before You Leap

Ted Baehr. 2011. How to Succeed in Hollywood without Losing Your Soul: A Field Guide to Christian Screenwirters, Actors, Producers, Directors, and More. Camilla, CA: Movieguide Publishing.

Review by Stephen W. Hiemstra

Working from home during the COVID pandemic, I became a full-time author. To spice things up, I spent more time translating my books and began writing fiction. Then, I turned to screenwriting.

Why? Being a recovering economist, I focused on my market. Hispanics read more than Angelos. Women read more than men. As a guy, I started screenwriting because guys (my natural audience) don’t read—they watch movies.

IntroductionSo, how does a Christian author break into Hollywood?

Author Ted Baehr writes:

“How to Succeed in Hollywood will tell you what you need to know about: telling stories though the mass media of entertainment: how to use your faith to change the culture of Hollywood; and how to make a creative contribution to the whole world. This book will show you how to develop your screenwriting, acting, directing, producing, and behind-the-scenes interests, to make Hollywood and the world better places for our children and grandchildren.” (xvii)

Baehr engages in much storytelling and didactive reasoning, but communicates most effectively through recounting interviews with Christian industry participants from across the spectrum of jobs in the entertainment industry.

As founder of Movieguide, an online film reviewing organization, Baehr’s motivation is clear:

“The average child sees 40,000 hours of media by the time they are seventeen years old, compared with 11,00 hours in school, 2,000 hours with parents, and 800 hours in church (if they go for an hour every Sunday).” (xxvii)

Having come to faith because of a movie (The Cross and the Switchblade), I am living testimony to the influence of faith-based entertainment.

While I have read and reviewed many books on screenwriting, Baehr’s book is the first to outline and describe the entire process of financing, creating, and distributing a film.

Background and OrganizationTed Baehr (1946+) graduated from Dartmouth College, studied law at New York University, and wrote his doctorate at Belhaven College in Jackson, Mississippi. He is best known as the Chairman of the Christian Film and Television Commission and founder of Movieguide, which reviews films from a Christian perspective.

Baehr writes in fourteen chapters:

SECTION I: FOUNDATIONS

There’s no business like show businessIn the beginningPlaces, pleaseIf it’s not on the page…Lord of the box office: Making sure your script pays offUnderstanding your audienceSECTION II: STEP-BY-STEP

The ProducersThe art of the dealFrom soup to nutsLights, camera, actionCutSnapshotsMovers and shakersConclusions (xi).These chapters are preceded by an introduction and followed by an epilogue, glossary, notes, and index. Interviews from more than twenty-eight Hollywood professionals were woven into these chapters. Those that I had heard of previously included Pat Boone and Jane Russell.

A Bit of HistoryChristians have been involved presenting the Gospel through the movie industry from its infancy. Baehr chronicles films about Jesus starting in 1897. One of the early films was the silent film, King of Kings, by Cecil B. De Mille (1927; 22). Between 1933 and 1966, every script was reviewed by representatives of the Roman Catholic Church, the Southern Baptist Church, and the Protestant Film Office following the Motion Picture Code that detailed what could and could not be included in a film (26-27).

Does it matter?

Baehr observes:

“Already the United States is considered by many to be the most immoral country in the world. Movies are often re-edited to include more sex and violence when released in the U.S. market. For example, the Australian release of the movie Return to Snowy River shows the hero and heroine getting married, while the U.S. release, portrays the couple co-habiting without marriage.” (30)

In my own experience, I noticed that Mexican Telenovelas (in Spanish) frequently depict people in tough spots consulting with their priest or pastor, while American films (in English) show such people heading to a bar. In Puerto Rico, my friends typically spoke politely in Spanish but reverted to English when they want to curse.

It matters.

Baehr writes: “movies and television programs are firstly entertainment, and secondly, vehicles to communicate and contain artistic elements.” (61) “Hollywood is our ambassador to the whole world.” (31). Apparently, the world gets it and they do not like what they see.

One of the most dramatic examples of a film affecting behavior came when Walt Disney released Bambi(1942). The year before its release, deer hunting was a $9.5 million business. The following year it earned only $4.1 million in tags, permits, and hunting trips (145). Revenues were more than cut in half—not bad influence for an animated film targeting kids.

StatisticsCommunicating is basic to the human experience. Baehr reminds us that in the Garden of Eden, “God tasked Adam with naming all the animals.” (144) Communicating with film, however, remains a daunting experience.

Baehr reports that the average movie takes nine years from start to finish (150). Over 300,000 scripts are written every year, but less than 300 movies open each year in theaters. In other words, only one in a thousand scripts is produced and distributed at a cost in 2010 dollars of $104 million. Authors often take years to get a script right. (151).

TreatmentBaehr makes an interesting suggestion. “To avoid read bias, it is very important to prepare your own treatment and present it along with your script.” (190) This point stuck out to me because I have found that script consultants are the best editors and the form of their feedback is a treatment.

So, what is a treatment?

Baehr writes:

“A treatment should include: (1) your log line, which is the basis of your pitch, (2) the premise of your story, (3) your main characters, and (4) a very brief synopsis of the story itself.” (190).

By contrast, most editors have trouble moving beyond offering line editing and identifying mistakes. Script editors are qualitatively better to the point that adapting your novel as a screenplay is a good way to solicit cheap and insightful feedback.

AssessmentTed Baehr’s book, How to Succeed in Hollywood without Losing Your Soul, provides an introduction to working the film industry from a Christian perspective. The writing is accessible, the stories insightful, and the perspective enlightening. The interviews with industry professionals add a sense of reality to it that I have not seen anywhere else. Screenwriters and other entertainment professions will want to take note.

Baehr on Film Industry: Look before You LeapAlso see:Books, Films, and MinistryOther ways to engage online:Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/bugs_25, SignupThe post Baehr on Film Industry: Look before You Leap appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.