Stephen W. Hiemstra's Blog, page 75

December 20, 2022

Lewis Leaves Room for Miracles

C.S. Lewis. 1974. Miracles: A Preliminary Study (Orig Pub 1960). New York: HarperCollins.

Review by Stephen W. Hiemstra

Being open to miracles does not mean that one is gullible or prone to fits of fantasy. Resistance to the idea of miracles is perhaps more a product of accepting an overly deterministic view of science. If the image of science is crafted primarily in the mathematics of interplanetary motion, then clearly one expects the world to adhere to a level of precision that defies the imagination and exceeds normal expectations about how things really work.

Introduction

In his book, Miracles, C.S. Lewis (3-4) writes:

“This book is intended as a preliminary to historical inquiry. I am not a trained historian and I shall not examine the historical evidence for the Christian miracles. My effort is to put my readers in a position to do so.”

He defines the word, miracle: “to mean interference with Nature by supernatural power.” (5)

While I grant the ability of God to intervene in spectacular ways in our lives, more often I observe God’s provision in quiet acts timed to my advantage. I entered government service in the last pay period of 1983 after a long spell of unemployment due to a hiring freeze, which meant that I qualified for the older, more generous retirement system. Fast forward twenty years and I was able to retire and attend seminary primarily because I could afford to retire, which would not have been true if my employment had been delayed only a couple days—something of no concern to me back when I started. My retirement date was also accompanied by gratuitous timing to my benefit without foreknowledge or special effort on my part. Miraculous? Was God’s finger on the scales of time to advantage me? I have certainly felt so.

Lewis begins his book with a cite from Aristotle: “Those who wish to succeed must ask the right preliminary questions.” (1) He goes on to observe: “What we learn from experience depends on the kind of philosophy we bring to experience.” (2) Lewis’ insight here is remarkable because he is writing before the postmodern period was at all obvious when most people still believed in objectivity, a modern, not postmodern, idea. It is now recognized that what we observe cannot be separated from the concepts that we hold. The definition of a problem in the scientific method is the most difficult step in the process because without a problem definition one only has an undefined felt need. Clearly, Lewis was already aware of this problem, long before others clearly articulated it.

Background and Organization

Clive Staples Lewis (1898–1963) is one of the best-known authors of the twentieth century, writing both fiction and nonfiction books that have become Christian classics and made into movies. Lewis was educated at Oxford and later joined the faculty Works include the Chronicles of Narnia and Mere Christianity. I previously reviewed his memoir, Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life (link).

Lewis writes Miracles in seventeen chapters:

The Scope of this Book

The Naturalist and the Supernaturalist

The Cardinal Difficulty of Naturalism

Nature and Supernature

A Further Difficulty in Naturalism

Answers to Misgivings

A Chapter of Red Herrings

Miracles and the Laws of Nature

A Chapter Not Strictly Necessary

‘Horrid Red Things’

Christianity and ‘Religion’

The Propriety of Miracles

On Probability

The Grand Miracle

Miracles of the Old Creation

Miracles of the New Creation

Epilogue (vii-viii).

These chapters are followed by several appendices.

The Grand Miracle

Lewis is a nonlinear thinker and my impatient mind finds him inaccessible at times, but his logic is unassailable. Lewis reminds us that the heart of the Christian message is a miracle that is often referred to as the incarnation. He writes:

“God became Man. Every other miracle prepares for this, or exhibits this, or results from this…It relates not a series of disconnected raids on Nature but the various steps of a strategically coherent invasion—an invasion which intends complete conquest and occupation’. The fitness, and therefore credibility, of the particular miracles depends on their relation to the Grand Miracle; all discussion of them in isolation from it is futile.” (173)

Lewis’ insight here is prescient and it eludes even the agile-minded. Think about it—how many people don’t you know who claim the title of Christian, but refuse to accept Jesus’ miracles as anything other than window dressing. Thomas Jefferson, for example, rewrote his Bible, editing out anything he considered miraculous—why did he bother? Without Christ, there is no Bible and the heart of the Christian message is the miracle of Christ’s incarnation and his resurrection.

Assessment

C.S. Lewis’ book, Miracles, is itself a wonder. While I read this book in English for purposes of this review, I have used a Spanish edition for my devotions this fall. Lewis is thought provoking, which makes the book good for devotional use. Readers interested in particular biblical miracles may want to look elsewhere because Lewis’ purpose in writing is more fundamentally to explore the relationship of miracles to our scientific preconceptions and help us realize the limits to such preoccupations.

Footnotes

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/C._S._L....

Lewis Leaves Room for Miracles

Also see:

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/X-Mas2022 , Signup

The post Lewis Leaves Room for Miracles appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

December 19, 2022

Contending Grace: Monday Monologues (podcast), December 19, 2022

By Stephen W. Hiemstra

This morning I will share a prayer and reflect on Contending Grace. After listening, please click here to take a brief listener survey (10 questions).

To listen, click on this link.

Hear the words; Walk the steps; Experience the joy!

Contending Grace: Monday Monologues (podcast), December 19, 2022

Also see:

The Face of God in the Parables

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/X-Mas2022 , Signup

The post Contending Grace: Monday Monologues (podcast), December 19, 2022 appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

December 18, 2022

Prayer of Restoration

By Stephen W. Hiemstra

Father God,

All praise and honor, power and glory, truth and justice are yours, because you offer us shelter that allows us to grow and become adults in a world more accustomed to stunted youths and bitter relationships. Be ever near.

Forgive us our youthful arrogance, our prideful rebellion, our wanton covetousness.

Thank you for the gift of your son, our savior Jesus Christ, who lived teaching us to love one another, healed our wounds, died on the cross for our sins, and rose again from dead that we might have life.

In the power of your Holy Spirit, teach us to model the grace and love of Jesus Christ to all that we meet. Grant us a spirit of truth and holiness.

In Jesus’ precious name, Amen.

Prayer of Restoration

Also see:

The Face of God in the Parables

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/X-Mas2022 , Signup

The post Prayer of Restoration appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

December 16, 2022

Contending Grace

No servant can serve two masters, for either he will hate the one and love the other,

or he will be devoted to the one and despise the other.

You cannot serve God and money.

(Luke 16:13)

By Stephen W. Hiemstra

The Lazarus and the Rich Man is a parable in the form of a lengthy story of two men: a poor beggar named Lazarus and a rich man, who is not named. This parable appears only in Luke 16 and it follows another story about an unfaithful and unscrupulous manager. This prior story concludes with the above proverbial statement: You cannot serve God and money. The context of this prior story suggests that money-obsessed Pharisees are the ones in view being criticized in the above story and also the rich man in our parable.

If grace is an undeserved blessing, then the Parable of Lazarus and the Rich Man is a story of contending acts of grace. We read:

“There was a rich man who was clothed in purple and fine linen and who feasted sumptuously every day. And at his gate was laid a poor man named Lazarus, covered with sores.” (Luke 16:19-20)

Neither acts of God’s sovereign grace are initially explained, but we learn more about the rich man as the story unfolds. We read:

“The poor man died and was carried by the angels to Abraham’s side. The rich man also died and was buried, and in Hades, being in torment, he lifted up his eyes and saw Abraham far off and Lazarus at his side.” (Luke 16:22-23)

For a Jew accustomed to blessings for adhering to the law and curses for disobeying the law in this life and the next, as outlined in Deuteronomy 28, we sense bewilderment in the rich man’s eyes as he looks up from Hades to Lazarus enjoying Abraham’s bosom. This role reversal is unexpected and comes as a shock that the rich man questions Abraham and asks Abraham to warn his five brothers, to which Abraham responds: ”They have Moses and the Prophets; let them hear them.”(Luke 16:29)

Curiously, we are never told why Lazarus warranted heaven, only that the rich man failed to heed Moses and the Prophets’ teaching on how to deal with divine judgment. Given the context of the parable, however, we can surmise that we are to love God, not money (Luke 16:13), unlike the Pharisees. The quality of our relationship with God is the key.

Grace in the Parable

For Lazarus, grace means a reversal of fortunes in death. God takes pity on him in death for his undeserved suffering in life.

For the rich man, grace means prosperity in life with the caveat that he love God, not money, and heed Mose’s and the Prophets.

The story is silent on Lazarus’ relationship with God and attitude towards Moses and the Prophets, which reinforces the perception that the parable is directed at and critical of the Pharisees, as with the prior story.

Grace in Relationship

The idea that God’s grace is dispensed in the context of relationship is explicit in the Parable of the Two Sons, usually called the Parable of the Prodigal Son. In the parable, the younger son asks for his inheritance early and uses it to engage in riotous living in a foreign country while the old son remains at home and works for this father. At this point, neither son loves his father. After ending up destitute, the younger son returns home to ask his father’s forgiveness which leaves the older son even more bitter, both at his brother and at his father for accepting him back. For the younger son, this episode represents a coming-of-age story where he learns to love his father, something that his older brother never manages (Luke 15:11-32).

In the Parable of the Two Sons, the father models God’s grace in two paragrammatical cases represented by the two sons. In both cases, the father offers restorative justice—grace designed to allow growth—where he might have rendered criminal justice, had the sons not been in relationship.

Restorative justice makes sense to Christians because we have known Christ our entire lives, but it was new to Jesus’ audience, as we read: “This our son is stubborn and rebellious; he will not obey our voice; he is a glutton and a drunkard. Then all the men of the city shall stone him to death with stones.” (Deut 21:20-21) One reading of the passage—“but while he was still a long way off, his father saw him and felt compassion, and ran and embraced him and kissed him. (Luke 15:20)—is that the father was protecting his son from a community more accustomed to stoning rebellious sons than offering them restoration. Against this backdrop, the father’s response is unexpected, a radical departure from local custom.

The grace that Jesus displays in the Parable of the Prodigal Son is transformative because it allows renewal of relationship and the opportunity of personal growth.

Contending Grace

Also see:

The Face of God in the Parables

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/X-Mas2022 , Signup

The post Contending Grace appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

December 13, 2022

Longfield Chronicles the Fundamentalist/Liberal Divide, Part 3

Bradley J. Longfield. 1991. The Presbyterian Controversy: Fundamentalists, Modernists, and Moderates. New York: Oxford University Press. (Go to Part 1; Part 2)

Bradley J. Longfield. 1991. The Presbyterian Controversy: Fundamentalists, Modernists, and Moderates. New York: Oxford University Press. (Go to Part 1; Part 2)

Review by Stephen W. Hiemstra

The Scot’s Confession of 1560, which is included in the Book of Confessions of the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. (PCUSA), outlines three conditions for a true church. A true church is one where the word of God is rightly preached, the sacraments rightly administered, and church discipline rightly administered.

Fundamentals of Faith

When the PCUSA abandoned its ordination requirements centered on the 5 fundamentals of the faith in 1925, it effectively lost the ability to distinguish itself as a true church as defined in its own confessions. The boundaries between church and society were fuzzed because of doctrinal diversity and with the passage of time the fuzz grew as elders were elected and pastors ordained that held increasingly diverse views. In effect, Presbyterians began a transition from being a reformed, confessional church to being a church united primarily in a common polity . This fundamental change, which is often misunderstood and frequently denied, Longfield articulates primarily in terms of the person of a pugnacious son of the South, J. Gresham Machen.

Longfield sees Machen differing from his opponents in the Presbyterian controversy in a number of ways, most importantly philosophically. He writes:

“The education Machen received at Princeton complemented and refined the religious heritage of his boyhood. Like the Thornwellian theology of the Southern Presbyterians, Princeton held tightly to the doctrines of the Westminster [confession] divines undergirded by Common Sense philosophy and the Baconian method. The Princeton Theology insisted on the primacy of ideas in religion and stood firmly for a strict doctrine of biblical inerrancy. Additionally, Princeton adhered to the traditional Reformed belief that Christians must strive to bring all of culture under God’s rule….Princeton was a bastion of Calvinist orthodoxy in an increasingly hostile world…” (40)

Old School Presbyterianism, as articulated by James Henley Thornwell was strictly confessional and viewed theology as “a positive science grounded in observation and induction, consisting of facts arranged and classified according to the necessary laws of the human mind.” (33) This philosophy, known as Scottish Common Sense Realism, maintained that: ”we can and do know the real world directly through our senses… [and that] Anyone in right mind… knew that the objective world, the self, causal relationships, and moral principles existed.” (34) Following Thornwell, Machen firmly believed that once the facts were known irrefutable conclusions (events not interpretations) could be drawn (222) [4.

Machen’s focus on correct doctrine, as embodied in the confessions, flowed immediately from his philosophical presuppositions (223). Obviously, from Machen’s perspective, deviating from correct doctrine was not only wrong; it was immoral, because it led one away from God. In some sense, a liberal was anyone who deviated from correct doctrine.

Robert Hastings Nichols, a professor at Auburn Theological Seminary in New York City, drafted a formal statement of the liberal positon in the PCUSA in 1923. The paper, which argued for theological diversity within the bounds of evangelical theology, evolved into the Auburn Affirmation and was endorsed by 174 signatories (79). The affirmation basically said that 5 fundamentals of the faith offered only one theory allowed by the scripture (77-79).

In other words, for the liberal no one, objective reality existed—history was not a matter of facts, but of interpretations (89). The emphasis was on religious experiences, not historical events such as found in the Bible (90-91). Writing about Henry Sloane Coffin, Longfield writes: “the Bible was not the ultimate authority for the Christian, Jesus alone was the Word of God; the Bible simply contained the Word.” (91)

At the end of Presbyterian Controversies, Bradley Longfield prods the PCUSA to “affirm a normative middle theological position with clear boundaries.” (235) The focus among evangelicals on the inerrancy of scripture and the doctrine of divine inspiration of scripture provide the boundaries on Biblical interpretation suggested.

The weakness in the evangelical position is philosophical: very few PCUSA pastors and theologians today subscribe to Scottish Common Sense Realism. If to be postmodern means to believe that scripture can only be interpreted correctly within its context, then we are all liberals in a Machen sense [5]. A strong, confessional position requires philosophical warrant—a philosophical problem requires a philosophical solution—which we can all agree upon[6]. In the absence of philosophical warrant and credibility, the confessions appear arbitrary—an act of faith [7]. In a practical, denominational sense, the philosophical diversity that characterizes the denomination makes it unlikely that boundaries can be agreed upon even if those boundaries are based on a shared history.

Clearly, Longfield’s book is an interesting read, very relevant to current controversies, and certainly worthy of ongoing study.

Footnotes

“The notes of the true Kirk, therefore, we believe, confess, and avow to be: first, the true preaching of the Word of God, in which God has revealed himself to us, as the writings of the prophets and apostles declare; secondly, the right administration of the sacraments of Christ Jesus, with which must be associated the Word and promise of God to seal and confirm them in our hearts; and lastly, ecclesiastical discipline uprightly ministered, as God’s Word prescribes, whereby vice is repressed and virtue nourished.” (PCUSA 1999, 3.18)

In 2012 at the General Assembly in Pittsburg, PA (which I attended), for example, the stated clerk opined before the entire body that the Book of Order need not comply with requirement of the Book of Confessions. They served different functions. This opinion paved the way, in part, for that body to endorse the ordination of homosexuals.

Very ironically, from the perspective of the liberal-fundamentalist divide, Scottish Common Sense Realism was foundational in the development of the scientific method. By contrast, the liberal philosophical position, borrowing heavily from Darwinian evolution—hence, the term progressive, actually undermined scientific advancement inasmuch as it came to question the existence of objective reality—a trend in thinking that later matured into postmodernism. If one does not believe in one, objective reality, then why invest time and money in researching it?

William Jennings Bryan, for example, also maintained that “true science and the bible could not disagree.” (56)

[5] The other tell that one has slid into a liberal leaning is the focus off of theology and onto experience. Liberal theology focus on feeling rather than thinking which reflects a debt to the romanticism of the 19th century. For the liberal, God is experienced through feelings, not through the mind. This makes it unreproduceable among and between individuals. By this lining of reasoning, we can have common experiences of God through service, crises, and mission trips, but we will have trouble describing what just happened. This makes agreement on and adherence to language, creeds and confessions difficult. Words denoting theological concepts become squishy. We like feeling words like progress, spirituality, and love which are hard to define; we have trouble with thinking words like creed, morality, and duty which have specific content.

[6] Plantinga (2000) attempts to fill this philosophical gap by offering the concept of warrant. He argues from a postmodern perspective that warrant is a reasonable standard for justifying Christian belief. The modern perspective of requiring logical proof, which is also not attained by the critics themselves, is argued not to be a reasonable standard on which to base judgment.

[7] My belief is that the existence of one God is obvious from the existence of only one set of physical laws in the universe. In some sense, the existence of one objective truth immediately follows from God’s immutability. Relative truth is more of an optical illusion.

References

Plantinga, Alvin. 2000. Warranteed Christian Belief. New York: Oxford University Press.

Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PC USA). 1999. The Constitution of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.)—Part I: Book of Confession. Louisville, KY: Office of the General Assembly.

Longfield Chronicles the Fundamentalist/Liberal Divide, Part 3

Also see:

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/X-Mas2022 , Signup

The post Longfield Chronicles the Fundamentalist/Liberal Divide, Part 3 appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

December 12, 2022

Great Physician: Monday Monologues (podcast), December 12, 2022

By Stephen W. Hiemstra

This morning I will share a prayer and reflect on Great Physician. After listening, please click here to take a brief listener survey (10 questions).

To listen, click on this link.

Hear the words; Walk the steps; Experience the joy!

Great Physician: Monday Monologues (podcast), December 12, 2022

Also see:

The Face of God in the Parables

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/thanks_22, Signup

The post Great Physician: Monday Monologues (podcast), December 12, 2022 appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

December 11, 2022

Prayer for Spiritual Healing

By Stephen W. Hiemstra

Almighty God, Great Physician, Spirit of Truth,

All power and dominion, honor and glory, and truth and justice are yours because you hear our afflictions, heal our diseases, and free us from fear. Be ever near.

Forgive our weaknesses, our gullibility, and inability to say no to sin. Be ever near.

Thank you for the many blessings, the blessings we see, and the blessings hid from our eyes when we are simply faithful. Be every near.

In the power of your Holy Spirit, turn our eyes away from sin, heal our bodies, and bring us closer to you in good times and bad.

In Jesus’ precious name, Amen.

Prayer for Spiritual Healing

Also see:

The Face of God in the Parables

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/thanks_22, Signup

The post Prayer for Spiritual Healing appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

December 9, 2022

Sin as Sickness

Those who are well have no need of a physician,

but those who are sick.

I have not come to call the righteous

but sinners to repentance.

(Luke 5:31-32)

By Stephen W. Hiemstra

Jesus’ Parable of the Doctor and the Sick is found in three Gospels (Mark 2:17. Matt 9:12-13, Luke 5:31-32). In each case, the parable is paired with a statement about his mission: “I have not come to call the righteous but sinners to repentance.” This pairing converts the parable into a doublet, a form of Hebrew poetry, where the first phrase is rephrased by the second. In other words, the healthy are righteous while the sick are sinners. Jesus’ role in this parable doublet is that of a physician.

We witness another example of this pairing of healing and forgiveness of sin in the healing of the paralytic, also found in three Gospels (Mark 2:9, Matt 9:5, Luke 5:23) and in each case found close to the Parable of the Doctor and the Sick. The key phrase in each account is: “Which is easier, to say to the paralytic, Your sins are forgiven, or to say, Rise, take up your bed and walk?” (Mark. 2:9) The argument is from the greater (physical healing) to the lesser (forgiveness of sin). The question is rhetorical because Jesus already knows what he will do.

The grace extended to the paralytic serves an important didactical point: Jesus has the power to forgive sins, as suggested in the Parable of the Doctor and the Sick (Luke 5:32). This is a claim to divinity, as noted in Mark’s Gospel: “Who can forgive sins but God alone?” (Mark 2:7) This is an example of a miracle functioning as a sign of God’s presence because only gracious and loving God would countermand the rules of the universe to heal someone. The only request made of the paralytic was to: “Rise, pick up your bed and go home.” (Luke 5:24)

Sin as an Illness

It is interesting that Jesus treats sin as an illness, much like the modern parallel of treating addictions as an illness. If sin is an illness, the shame is relinquished and the sinner is allowed to accept forgiveness. Shame is normally a barrier to healing and forgiveness as those responsible are excluded from normal relationships with family and community.

Georges (2017, 10-11) sees three spiritual cultures that appear as responses to sin: guilt, shame, and fear:

Guilt-innocence cultures who focus on an individual’s response to law breaking and the pursuit of justice.

Shame-honor cultures who focus on fulfilling group expectations and restoring honor when norms are violated.

Fear-power cultures who focus on fear of evil and seek power over the spiritual world through magic, spells, curses, and rituals.

Treating sin as a sickness in a guilt-innocence culture relieves one of a legal violation, in an honor culture one is relieved of shame, and in a fear culture one is relieved of a curse. In each case, treating sin as an illness allows healing to take place that might otherwise not be possible as those in power loose their claim on the sinner.

The impact of treating sin as an illness is particularly important in dealing with besetting sins. These are sins with the characteristics of addiction that trap and enslave us over long periods of time. Here we find things like sexual sins, sins involving money and power over others, and attitudes that preclude forgiveness.

Seeing Jesus as a dispenser of grace, healing, and forgiveness places him at a cultural-spiritual vortex, which remains illusive even today. It is no wonder that Jesus’ life was in danger the more real his healing miracles became (e.g. Mark 3:1-6).

References

Georges, Jayson. 2017. The 3-D Gospel: Ministry in Guilt, Shame, and Fear Cultures. Time Press.

Sin as Sickness

Also see:

The Face of God in the Parables

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/thanks_22, Signup

The post Sin as Sickness appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

December 6, 2022

Longfield Chronicles the Fundamentalist/Liberal Divide, Part 2

Bradley J. Longfield. 1991. The Presbyterian Controversy: Fundamentalists, Modernists, and Moderates. New York: Oxford University Press. (Go to Part 1; Part 3)

Bradley J. Longfield. 1991. The Presbyterian Controversy: Fundamentalists, Modernists, and Moderates. New York: Oxford University Press. (Go to Part 1; Part 3)

Review by Stephen W. Hiemstra

After sensing a call to pastoral service in 2004 my first response was to attend an inquirer’s weekend at Princeton Theological Seminary (PTS) in Princeton, NJ. I was never more excited in my entire life. Still, tension clouded my excitement—I had waited months to attend the Passion of the Christ produced by Mel Gibson with fellow seminarians. Who would come with? On Saturday night when 60 inquirers were asked who wanted to attend only one other student responded. (The others preferred to attend a play named after a female body-part). I eventually wrote PTS off my list of prospective seminaries, but not for a lack of interest.

My Saturday night disappointment at PTS trivially highlights tensions in the PCUSA that were already evident in the 1920s. Longfield highlights 3 significant disputes within the church over the period from 1922 through 1936: ordination requirements, the mission of Princeton Seminary, and the orthodoxy of the Board of Foreign Missions (4). Let me address each briefly in turn.

Ordination Requirements

Longfield dates the Presbyterian controversy to a sermon preached by Dr. Harry Emerson Fosdick on May 21, 1922 at the First Presbyterian Church in New York City entitled: “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?” (9) The sermon turned on knowing the difference between a fundamentalist and a liberal Presbyterian.

At that time, a candidate for ordination in the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. (PCUSA) had to subscribe to the 5 fundamentals of the faith:

The inerrancy of scripture;

The virgin birth of Jesus;

The doctrine of substitutionary atonement (Christ died for our sins);

The bodily resurrection of Christ; and

The miracle-working power of Christ (9, 78).

These requirements were instituted in 1910 by the General Assembly of the PCUSA. Thus, a fundamentalist was not a pejorative term at that point; it simply meant that one met the requirements for ordination.

By contrast, Fosdick saw liberals as: “sincere evangelical Christians who were striving to reconcile the new knowledge of history, science, and religion with the old faith.” (9). The liberal view of scripture was not inerrancy, but “the progressive unfolding of the character of God and that development, not supernatural intervention, was God’s way of working out his will in the world.” (10) Note the influence of evolution on the liberal interpretation of scripture (12-15).

Harry Emerson Fosdick

Fosdick resigned his pulpit at First Presbyterian Church on October 22,1924 to avoid censure (126-127), but was immediately called to pastor Park Avenue Baptist Church. Notwithstanding, in 1925 a special commission of the General Assembly relinquished the 5 fundamentals of the faith as an ordination requirement (161). Moderator Charles R. Erdman engineered the change out of a belief that: “Christian living had precedence over matters of precise doctrine…any man good enough to go to heaven…is good enough to be a member of our church” (141-142). In other words, practical theology trumped systematic theology—previously the hallmark of reformed theology since the reformation.

Reorganization of Princeton Theological Seminary

The College of New Jersey (later called Princeton College) was chartered in 1746 on account of the expulsion of a young student named David Brainard from Yale College who said in private conversation that one of his tutors had “no more grace than a chair”. Brainard had the support of the Presbytery, but Yale refused to readmit him (Piper 2001, 128, 156). In 1812, Princeton Theological Seminary (PTS) was organized separately from Princeton College, in part, because modern universities no longer considered theology one of the sciences and certainly not “The Queen of the Sciences”, as it was known in the Middle Ages.

Throughout its history PTS defended Old School Presbyterianism which taught strict Calvinism, opposed the teaching of Darwin, and defended scriptural inerrancy (22, 133). Princeton Theology, as it was known, made PTS the standard-bearer of fundamentalist theology in the PCUSA. The point man during this controversy was Professor J. Gresham Machen who described PTS as “a lighthouse of orthodoxy in an increasingly secular world.” (169)

J. Gresham Machen

After the General Assembly abandoned the 5 fundamentals of the faith in 1925, attention shifted to PTS and Machen, who had so staunchly defined those fundamentals. Having lost the battle in the denomination, Machen’s promotion to Professor of Apologetics and Christians Ethics at PTS, which had been offered by the board of directors, would not likely be confirmed by the General Assembly (161,163). In 1926, the General Assembly appointed a special committee to study at PTS. In 1929, the General Assembly adopted a reorganization plan which strengthened the office of the president and merged the board of directors and the trustees into a single committee.

While no changes were proposed to the PTS charter or mission, the new committee included two liberals (out of 33) who had signed the Auburn Affirmation (a liberal manifesto; 173). Machen and three other PTS faculty members responded by leaving to organize a new seminary to carry on the traditions of the Old Princeton known as Westminster Theological Seminary which was set up in Philadelphia, PA (176).

Board of Foreign Missions

Foreign missionary activity reached an all-time high in the late nineteenth following the formation in 1886 of the Student Volunteer Movement (SVM), essentially the missionary agency of the Young Men’s Christian Organization (YMCA). SVM’s founding following a call by Dwight Moody to: “The evangelization of the world in this generation.” (18, 185). Between 1886 and 1936, roughly 13,000 missionaries were recruited. An important leader in the SVM was Robert E. Speer who personally recruited 1,100 undergraduates for missions during his last two years at PTS (186).

Speer was a charismatic and pragmatic leader. Longfield writes:

“Speer’s emphasis on a simple Christocentric gospel, conducive to Christian unity and missionary success, his disparagement of systematic theology, and his understanding of the church as a missionary body persisted throughout his career.” (188)

Speer’s theological pragmaticism likely alienated him from Machen who in 1933 organized an Independent Board for Presbyterian Foreign Missions, a move opposed by Speer. The Independent Board was eventually shut down by the General Assembly (180). Speer retired in 1937.

Longfield dates the close of the Presbyterian Controversy in 1936 following Machen’s death in 1935 and the formation of the Presbyterian Church in American in 1936 (213). While in this review I have focused on the decisions reached during this controversy, Longfield goes further. Part 3 of this review will look at the ideas motivating these decisions and some of their implications.

Footnotes

The Vagina Monologues (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Vagi...).

I was working full-time in federal service at that time. PTS and the other Presbyterian seminaries focused on providing a full-time, residential seminary experience.

Also see: Longfield Surveys Interface of Presbyterians and Culture, Part 2 (http://wp.me/p3Xeut-Tp).

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Em...

Today, we might describe that tutor as an atheist but in 1746 such a charge would be considered slander even if true.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theology

Calvinists subscribed to a systematic understanding of theology summarized in the acronym, TULIP. TULIP stands for Total depravity, Unconditional election, Limited atonement, Irresistible grace, and Perseverance of the saints (Sproul 1997, 118).

References

Piper, John. 2001. The Hidden Smile of God: The Fruit of Affliction in the Lives of John Bunyan, William Cowper, and David Brainerd. Wheaton: Crossway Books.

Sproul, R.C. 1997. What is Reformed Theology: Understanding the Basics. Grand Rapids: BakerBooks.

Longfield Chronicles the Fundamentalist/Liberal Divide, Part 2

Also see:

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/thanks_22, Signup

The post Longfield Chronicles the Fundamentalist/Liberal Divide, Part 2 appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

December 5, 2022

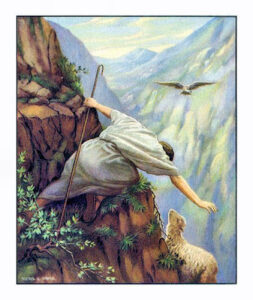

Lost Sheep: Monday Monologues (podcast), December 5, 2022

By Stephen W. Hiemstra

This morning I will share a prayer and reflect on Lost Sheep. After listening, please click here to take a brief listener survey (10 questions).

To listen, click on this link.

Hear the words; Walk the steps; Experience the joy!

Lost Sheep: Monday Monologues (podcast), December 5, 2022

Also see:

The Face of God in the Parables

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/thanks_22, Signup

The post Lost Sheep: Monday Monologues (podcast), December 5, 2022 appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.