Stephen W. Hiemstra's Blog, page 72

February 10, 2023

The Two Brothers

A soft answer turns away wrath,

but a harsh word stirs up anger.

(Prov 15:1)

By Stephen W. Hiemstra

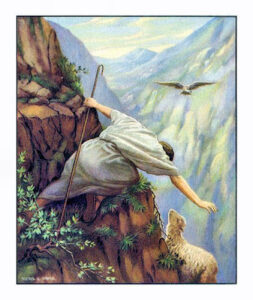

Jesus tells the story of a man with two sons, neither of whom loved their father. The younger son came to him one day and asked for his inheritance in cash. He then took the money, left town, and began living in style in a foreign country. This reckless lifestyle did not last long and soon the young man had to get a job. Not being a planner, he had to accept degrading work. As the son’s mind began to wander, he remembered his good life at home and resolved to beg his father to take him back as a household servant. When the father saw that his son was coming, he went out to meet him and wrapped his arms around him. As the son began to apologize for his horrible behavior, his father would hear none of it. He took his son; cleaned him up; and got him some new clothes (Gen 3:21). Afterwards, he threw a party for his son. Later, when his older brother came home and discovered the party, he became jealous and started behaving badly. But his father reminded him: “celebrate and be glad, for this your brother was dead, and is alive; he was lost, and is found.” (Luke 15:32)

The Parable of the Two Brothers, often called the Parable of the Prodigal Son, shows a young man going through a series of challenges—transitions—that enabled him to see his father with new eyes and to accept his father’s help. Without these challenges, he—like his older brother—would not have been able to bridge the gap between him and his father. Without his father’s acceptance, he could not have returned home.

Here we see the father’s love for his son as the catalyst for his son’s growth and maturity, a kind of coming-of-age story. By contrast, his older brother remained angry and stuck neither able to love either his brother nor his father, a pattern that today might be described as co-dependency. We might imagine that the boy’s absence helped the father move beyond a stricter parenting style that obviously failed to engender growth in the older brother.

Grace as Love

In the Parable of the Two Sons, the father models God’s grace in two paragrammatical cases represented by the two sons. In both cases, the father offers restorative justice—grace designed to allow growth—where he might have rendered criminal justice, had the sons not been in relationship.

Restorative justice makes sense to Christians because we have known Christ our entire lives, but it was new to Jesus’ audience, as we read: “This our son is stubborn and rebellious; he will not obey our voice; he is a glutton and a drunkard. Then all the men of the city shall stone him to death with stones.” (Deut 21:20-21) One reading of the passage—“but while he was still a long way off, his father saw him and felt compassion, and ran and embraced him and kissed him. (Luke 15:20)—is that the father was protecting his son from a community more accustomed to stoning rebellious sons than offering them restoration. Against this backdrop, the father’s response is unexpected, a radical departure from local custom.

The love that Jesus highlights in the parable is transformative because it allows renewal of relationship and the opportunity of personal growth, reminiscent of God’s request of Abraham: “Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you.”(Gen 12:1) Growth in relationship is a radical departure from a traditional society that more typically values loyalty in well-defined (static) relationships, not independence and growth in dynamic relationships.

In my own family, sons were expected to serve their fathers on the farm well into middle age. My grandfather broke with this tradition because his own ambition to attend college and study to become a pastor was not warmly embraced. Instead, he followed his own father into farming, a source of much resentment.

A Structural Interpretation

Craig Blomberg (2012, 197) classifies Jesus’ parables by their structure, not their content. He begins with an analysis of parables, like the Parable of the Two Brothers, writing:

“Many of Jesus’ parables have three main characters. Quite frequently, these include an authority figure and two contrasting subordinates. The authority figure, usually a king or master, judges between the two subordinates, who in turn exhibit contrasting behavior. These have been called monarchic parables.”

Here the authority figure is a father who has two sons. Blomberg (2012,200-201) sees one point for each character:

“(1) Even as the prodigal always had the option of repenting and returning home, so also all sinners, however, wicked, may confess their sins and turn to God in contrition. (2) Even as the father went to elaborate lengths to offer reconciliation to the prodigal, so also God offers all people, however undeserving, lavish forgiveness of sins if they are willing to accept it. (3) Even as the older brother should not have begrudged his brother’s reinstatement but rather rejoiced in it, so those who claim to be God’s people should be glad and not mad that he extends his grace even to the most undeserving.”

The extraordinary love of the father is unexpected, which hints that the parable is allegorical (Blomberg 2012, 204). The love offered by the father is also unconditioned, contrary to Jewish tradition. Because growing up and leaving home involves many forms of loss that must be grieved, such growth is difficult under the best of circumstances (Mitchell and Anderson 1983, 51). This makes Abraham’s journey of faith and ours all the more remarkable in this time when many turned the noun, adult, into a verb.

References

Blomberg, Craig L. 2012. Interpreting the Parables. Downers Grove: IVP Academic.

Mitchell, Kenneth R. and Herbert Anderson. 1983. All Our Losses; All Our Griefs: Resources for Pastoral Care. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press.

The Two Brothers

Also see:

The Face of God in the Parables

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/Janu_2023 , Signup

The post The Two Brothers appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

February 7, 2023

Plantinga Defends Confessional Faith, Part 3

Alvin Plantinga. 2000. Warranted Christian Belief. New York: Oxford University Press. (Goto Part 1; Goto Part 2)

Alvin Plantinga. 2000. Warranted Christian Belief. New York: Oxford University Press. (Goto Part 1; Goto Part 2)By Stephen W. Hiemstra

Alvin Plantinga begins his rebuttal of atheistic critiques citing the Apostle Paul’s words:

“For his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made. So they are without excuse.” (Rom. 1:20 ESV)

This is an interesting place to start because Paul goes on to share what is essentially the God’s curse for rejecting salvation under the new covenant in Christ. The curse is that the disbeliever is “given over to” (become a slave of) the desires of their own heart which has, of course, been corrupted by original sin. Paul’s assessment here is that disbelievers have specifically fallen into the sin of idolatry. This curse is not a random rant, as is often alleged.

Plantinga recaps the atheologian’s complaint with these words:

“What we saw is that this complaint is really the claim that Christian and other theistic belief is irrational in the sense that it originates in cognitive malfunction (Marx) or in cognitive proper function that is aimed at something other than the truth (Freud).” (167)

Behind modern atheism is a similar problem of idolatry where the idolatry is focused on technologies to manipulate creation physically (science) and other techniques (social, political, and psychological) to manipulate fellow human beings. It is interesting that only the church and faith could stand in the way of such Faustian manipulation.

Plantinga builds a conceptual model on the foundation articulated by Thomas Aquinas and John Calvin (A/C) based on Paul’s own words. The claim is offered that “there is a kind of natural knowledge of God.” (170). Calvin calls this knowledge sensus divinitatis which is:

“A disposition or set of dispositions to form theistic beliefs in various circumstances, in response to the sorts of conditions or stimuli that trigger the working of this sense of divinity.” (171)

Plantinga offers 6 characteristics of this sensus divinitatis model:

“ According to the A/C model, this natural knowledge of God is not arrived at by inference or argument…but in a more immediate way…In this regard, the sensus divinitatis resembles perception, memory, and a priori belief…”

“Proper Basicality with Respect to Justification. On the A/C model, then, theistic belief as produced by the sensus divinitatis is basic…As I argued above…it is really pretty obvious that a believer in God is or can be deontologically justified.”

“Proper Basicality with Respect to Warrant…Perceptual beliefs are properly basic in this sense: such beliefs are typically accepted in a basic way, and they often have warrant.”

“Natural Knowledge of God. This capacity for knowledge of God is part of our original cognitive equipment, part of the fundamental epistemic establishment with which we have been created by God.”

“Perceptual or Experiential Knowledge…knowledge of God ordinarily comes not through inference from other things one believes, but from a sensus divinitatis…To the believer, the presence of God is often palpable.”

“Sin and Natural Knowledge of God…this natural knowledge of God has been compromised, weakened, reduced, smothered, overlaid, or impeded by sin and its consequences.” (175-184)

Plantinga summarizes with these words:

“a belief enjoys warrant when it is formed by properly functioning cognitive faculties in a congenial epistemic environment according to a design plan successfully aimed at truth—which includes…the avoidance of error.” (184)

In a nutshell, God made us to accept belief in a natural, sober way and when we respond in faith our belief cannot be ridiculed as dysfunctional or in any way in error.

Plantinga then turns back to the atheological critics. For example, with respect to Freud, he writes:

“…according to the Heidelberg Catechism, the first thing [on coming to faith] I have to know is my sins and miseries. This isn’t precisely a fulfillment of one’s wildest dreams.” (195)

Obviously, sin is a problem for those who, like Freud, believe that faith is some kind of projection of desire onto God. Plantinga offers an interesting insight into sin’s pervasive and devastating impact on fallen humanity:

“Original sin involves both intellect and will, it is both cognitive and affective. On the one hand, it carries with it a sort of blindness, a sort of imperceptiveness, dullness, stupidity. This is a cognitive limitation that first of all prevents its victim from proper knowledge of God and his beauty, glory, and love; it also prevents him from seeing what is worth loving and what worth hating…But sin is also and perhaps primarily an affective disorder or malfunction. Our affections are skewed, directed to the wrong objects; we love and hate the wrong things.” (207-208).

Let me end my summary at this point.

Alvin Plantinga’s Warranted Christian Belief provides the reader with an interesting rebuttal to the main complaints of the modern atheists—Marx, Freud, and, to a lesser extent, Nietzsche—about faith. None appeal to scientific knowledge in their complaints; in fact, they offer little real evidence for their characterizations of faith. Religious faith is justified and immune from slander when approached soberly and in full knowledge of alternatives. While a typical reader would probably enjoy a thumbnail sketch of these arguments, Plantinga’s thoroughness offers comfort for those afflicted by the apologetic passions.

Plantinga’s work has one implication that deserves thought. If the modern critique of the Christian faith washes out ultimately as nothing more than unsophisticated slander, then philosophies and actions predicated on that slander are themselves without warrant—nothing more than rabbit-hole and, in some cases, a nightmare. What fruit has come of it that deserves saving and what fruit should be discarded? (Luke 76:43-44)

Having crawled out of the rabbit-hole and dusted ourselves off, what would hitting the reset button look like?

“Claiming to be wise, they became fools, and exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images resembling mortal man and birds and animals and creeping things. Therefore God gave them up in the lusts of their hearts to impurity, to the dishonoring of their bodies among themselves, because they exchanged the truth about God for a lie and worshiped and served the creature rather than the Creator…” (Rom. 1:22-25 ESV) That is, by giving them over to their own desires, they receive the pagan’s curse.

Goethe’s Faust (1806) sells his soul to the devil in exchange for access to all knowledge, especially transcendental knowledge (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Goethe%2...).

Plantinga Defends Confessional Faith, Part 3

Also see:

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/Janu_2023 , Signup

The post Plantinga Defends Confessional Faith, Part 3 appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

February 6, 2023

Love: Monday Monologues (podcast), February 6, 2023

By Stephen W. Hiemstra

This morning I will share a prayer and reflect on the Good Samaritan. After listening, please click here to take a brief listener survey (10 questions).

To listen, click on this link.

Hear the words; Walk the steps; Experience the joy!

Love: Monday Monologues (podcast), February 6, 2023

Also see:

The Face of God in the Parables

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/Janu_2023 , Signup

The post Love: Monday Monologues (podcast), February 6, 2023 appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

February 5, 2023

Prayer for Love

By Stephen W. Hiemstra

Almighty Father,

All glory and honor, power and dominion, truth and justice are yours, because you first loved us for while we were yet sinners you sent Christ to die for us (Rom 5:8).

Forgive our hardened hearts. Our unwillingness to love as Jesus taught.

Thank you for the many blessings of this life: our families, our health, our work, and the many benefits of modern technology.

In the power of your Holy Spirit, open our hearts, enlighten our thoughts, strengthen our hands in your service.

In the precious name of Jesus, Amen.

Prayer for Love

Also see:

The Face of God in the Parables

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/Janu_2023 , Signup

The post Prayer for Love appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

February 3, 2023

The Good Samaritan Revisited

O LORD God of heaven, the great and awesome God

who keeps covenant and steadfast love with those

who love him and keep his commandments.

(Neh 1:5)

By Stephen W. Hiemstra

The fourth characteristic of God in Exodus 34:6 is love. The word, hesed (חֶ֥סֶד), translated as steadfast love (ESV), long-suffering (KJV), or lovingkindness (NAS) means: “obligation to the community in relation to relatives, friends, guests, master and servants; unity, solidarity, loyalty” (HOLL). Alternatively, it can be translated as “goodness, kindness.” (BDAG 3279) The meaning of the Greek word used to translate hesed in the Septuagint, πολυέλεος, is unknown.

The Greek word for love (ἀγαπάω) in the New Testament is the same in John and Matthew’s Gospels, and means: “to have a warm regard for and interest in another, cherish, have affection for, love” (BDAG 38.1). The Hebrew word for agape love is: אָהַ֙בְתָּ (ahabet Gen 22:2), not hesed. Agape love is clearly distinguished from romantic (eros) and brotherly (philos) love, because the Greek language has separate words for each, but agape love and philos love both serve an erotic usage in the Song of Solomon (Sol 1:2-1:3), which adds to the confusion over love’s definitions.

Covenantal Love

The covenantal context of Exodus 34:6 makes it clear that the hesed love in view here is not a generic agape love, but a more specific covenantal love focused on keeping one’s promises (Hafemann 2007, 33). We honor God and our neighbor by treating them with respect and keeping our word, especially when it hurts. Just like when we get married we assume a heart-felt relationship, but we depend on our spouse to keep their promises.

The ethical image of God is a hot-button issue today because of the proclivity of many pastors and Christians to view God exclusively through the lens of love, as we read repeatedly through the writings of the Apostle John: “Anyone who does not love does not know God, because God is love.” (1 John 4:8). Matthew’s double love command is likewise frequently cited:

Teacher, which is the great commandment in the Law? And he said to him, You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind. This is the great and first commandment. And a second is like it: You shall love your neighbor as yourself. On these two commandments depend all the Law and the Prophets. (Matt 22:36-40)

Agape love is less helpful in understanding God’s character because of the wild definitions of love floating around in postmodern culture (e.g. Rogers 2009, 52-65) and the wide scope in Hebrew and Greek usage. Confusion over the meaning of love was already present in the first century, which we know because the Apostle Paul devoted an entire chapter to its definition in his letter to the church at Corinth (1 Cor 13), a city infamous for prostitution.

In the Old Testament, God interacts with his people primarily through the giving of covenants. Hafemann (2007, 21) writes:

God’s relationship with the world and his people is not a theoretical abstraction, not is fundamentally a subjective experience. Rather, with salvation history as its framework, this relationship is expressed in and defined by the interrelated covenant that exist through the history of redemption.

Among the many allusions to covenant making in the Bible, none is more detailed than covenant with Moses.

God’s Mercy Precedes His Love

Bonhoeffer (1976, 50) offers an important insight here: “No one knows God unless God reveals Himself to him. And so none knows what love is except in the self-revelation of God. Love, then, is the revelation of God.” The fact that mercy, not love, is the first characteristic of God reinforces the idea that love requires an interpretation beyond the agape love that so many cherish. When we say that Jesus died for our sins, we experience his love by means of (or through the instrument of) his mercy. The point that mercy is more primal in the biblical context than love is also reinforced in Jesus’ Beatitudes: mercy is listed; love is not (Matt 5:3-11). When we experience God’s love through his mercy, covenant-keeping love, not agape love, is in focus.

The Good Samaritan

Jesus introduces the Parable of the Good Samaritan in response to a question posed by an attorney over how to inherit eternal life (Luke 10:25). Jesus asks the attorney to answer his own question and the attorney cites the double-love command: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind, and your neighbor as yourself.” (Luke 10:27) Jesus accepts this answer, but the attorney wants to know more, picking nits and asking: “Who is my neighbor?” (Luke 10:29)

This context is important because it specifically addresses the problem with interpreting God’s love. When the Samaritan stops to attend to the wounds of the man beaten by robbers, it is an example presumably of offering love to an enemy, because the man beaten is presumed to have been a Jew and Jews hated Samaritans (Matt 5:43-46). Because the Samaritan is still likely at risk of suffering the same fate and there is no presumption that the Samaritan would serve as a first-century emergency medical technician, the parable has an eschatological tinge to it—it is like the clouds part and we briefly glimpse heaven itself.

The parable is more than a simple metaphor or simile because whole groups of people are symbolized—robbers, Samaritans, priests, Levites, innkeepers—making the parable more of a brief morality play. In the core story there is also an echo of the story of Cain and Abel (Gen 4) because Samaritans and Jews can be thought of as estranged brothers who have been reunited in love (1 Kgs 12).

The Good Samaritan Revisited

Also see:

The Face of God in the Parables

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/Janu_2023 , Signup

The post The Good Samaritan Revisited appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

January 31, 2023

Plantinga Defends Confessional Faith, Part 2

Alvin Plantinga. 2000. Warranted Christian Belief. New York: Oxford University Press. (Goto Part 1; Goto Part 3)

Alvin Plantinga. 2000. Warranted Christian Belief. New York: Oxford University Press. (Goto Part 1; Goto Part 3)

By Stephen W. Hiemstra

Alvin Plantinga sees two basic classes of objections to Christian faith since the Enlightenment:

The first objection he calls the de facto arguments—objections to the truth of Christian belief.

The second objective he calls de jure arguments—objections often harder to pin down—more like innuendo than like a serious philosophical critique.

He further breaks down the de jure objection into 3 categories: Christian belief is unjustified, irrational, and unwarranted (viii-x). Let me address each of these 4 arguments in turn.

De Facto Objections to Faith

The most widely known de facto objection to faith is based on suffering (viii), but Plantinga sees these arguments as well known and straightforward to address (ix).

One objection has to do with discussing God’s transcendence. Citing Gordon Kaufman (1972, 8), for example, Plantinga writes:

“The central problem of theological discourse, not shared with any other ‘language game’ is the meaning of the term ‘God’. ‘God” raises special problems of meaning because it is a noun which by definition refers to a reality transcendent of, and thus not locatable within, experience.”

Plantinga turns this argument on its head asking—did Kaufman (or, for that matter, Kant who he is paraphrasing) show (or prove) that this critique has any real merit? (5; 31) This same response to other objections phrased primarily as slander or innuendo aimed at believers or God himself. Plantinga observes: ”If God is omnipotent, infinitely powerful, won’t he be able to manifest himself in our experience, bring it about that we experience him?” (34)

In another example, when Freud objects to Christian faith because it is likely wish fulfillment, Plantinga asks: what is the problem? Are you saying faith is like to be false? (x) It is hard to rebut a poorly articulated criticism which takes more the form of an ad hominine attack than a philosophical claim about truth. It is like the television show that repeatedly (and disproportionally) pictures Christian pastors as unsophisticated or morally corrupt, but offers no information to support for the implied character assassination—repeating a claim does not strengthen its merits, but it does wear out those targeted.

The implication in Plantinga’s rebuttal is that Christians are frequently too polite to unmask unfair criticism designed primarily to intimidate or shame believers. Perhaps, for this reason, Plantinga focuses more on the 3 de jure objections (63).

Christian Faith is Unjustified

Plantinga notes that critics claim that is unreasonable or unjustified, but the precise nature of their objection is unclear—it lacks cogence. What exactly is the question?

He observes that the 3 traditional proofs of God’s existence—the cosmological, teleological, and ontological arguments—provide a prima facia argument for God’s existence and basically rebut this criticism (68).

Plantinga explores the requirements of evidentialism, which argues: “that belief in God is rationally justifiable or acceptable only if there is good evidence for it. (70; 82) He then observes that John Lock offers 4 kinds of knowledge:

“Perceiving the agreement or disagreement of our ideas.” [judgment?]

“…propositions about the contents of your own mind…”

“…knowledge of other things of external objects around you.”

“…demonstrative knowledge…know by a proportion by deducing it…” (75-77)

After a lengthy discussion of the classical requirements of evidentialism, Plantinga finds no de jure question to suggest that Christian faith is unjustified (107).

Christian Faith is Irrational

Plantinga asks: “what is it for a belief to be rational?” He observes these forms of rationality:

“Aristoltelian rationality, the sense in which, as Aristole said, Man is a rational animal…

Rationality as a proper function [not dysfunction or pathology 110];

Rationality as within or conforming to the deliverance of reason;

Means-ends rationality, where the question is whether a particular means someone chooses is , in fact, a good means to her ends; and

Deontological rationality [or justification].” (109)

In his review of these different definitions of rationality, he finds “not much of a leg to stand on.” (135) One point that would suggest a rational criticism is when someone loves another person or people group sacrificially. If I put myself at risk in becoming a missionary to a dangerous place or people group, then in a real sense I am acting sub-rationally and those disadvantaged by my actions may criticize my rationality (or my motives) in various ways.

Christian Faith is Unwarranted

Plantinga observes that atheologians (Freud, Marx, Nietzsche) have criticized Christian belief as irrational but not in the sense described above—Nietzsche, for example, referred to Christianity as a slave religion (136). Freud described Christianity as “wish-fulfillment” and as an illusion serving not a rational purpose, but serving psychological purposes (142). In Marx’s description of religion as “the opium of the people” suggests more a type of cognitive dysfunction (141).

Plantinga concludes:

“when Freud and Marx say that Christian belief or theistic belief or even perhaps religious belief in general is irrational, the basic idea is that belief of this sort is not among the proper deliverances of our rational faculties.” (151)

Plantinga accordingly concludes that the real criticism of “Christian belief, whether true or false, is at any rate without warrant.” (153; 163). In this context, warrant means:

“…a belief has warrant only if it is produced by cognitive faculties that are functioning properly, subject to no disorder or dysfunction—construed as including absence of impedance as well as pathology.” (153-154)

Plantinga’s strategy in analyzing the atheologian complaints accordingly is to discuss what they are not saying—not complaining about evidence, not complaining about rationality in the usual sense, not offering evidence that God does not exist—to eliminate the non-issues. What remains as their complaint is a twist on rationality—actually more of a rant—you must be on drugs or out of your mind—which is not a serious philosophical complaint except for the fact that so many people repeat it. So Plantinga politely calls this complaint a charge of cognitive dysfunction.

At this point, Plantinga has defined the de jure criticism of atheologians in a manner which can now be properly evaluated in philosophical sense. The problem is not a problem per se with the existence of God (a metaphysical issue), but with the process of accepting a belief (an anthropological issue). This definition both clarifies and simplifies the development of a response.

In part 3 of this review, I will examine his response to this problem statement.

Footnotes

Taylor (2006, 113) writes: “God’s existence can be explained by the fact that he is perfect in nature and therefore necessarily existent.”

Taylor (2006, 127) writes: “The traditional design argument focuses on things in nature that appear to be designed.” Complexity in nature points to a grand designer the way that finding a watch on the beach points to the watch maker.

“Anselm defined God as that than which nothing greater can be conceived” which is the most common ontological argument for God’s existence (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ontologi...).

Plantinga notes that an illusion, in contrast to a delusion, is not necessarily false (139).

References

Kaufman, Gordon. 1972. God the Problem. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Taylor, James W. 2006. Introducing Apologetics: Cultivating Christian Commitment. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic.

Plantinga Defends Confessional Faith, Part 2

Also see:

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/Janu_2023 , Signup

The post Plantinga Defends Confessional Faith, Part 2 appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

January 30, 2023

Applying Patience: Monday Monologues (podcast), January 30, 2023

By Stephen W. Hiemstra

This morning I will share a prayer and reflect on Applying Patience. After listening, please click here to take a brief listener survey (10 questions).

To listen, click on this link.

Hear the words; Walk the steps; Experience the joy!

Applying Patience: Monday Monologues (podcast), January 30, 2023

Also see:

The Face of God in the Parables

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/Janu_2023 , Signup

The post Applying Patience: Monday Monologues (podcast), January 30, 2023 appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

January 29, 2023

Monica Prayer

By Stephen W. Hiemstra

Loving father,

All glory and honor, power and dominion, truth and justice are yours, because you created us ex-nihilo, out of nothing, and, when we strayed, you patiently sent your son, Jesus Christ, to rescue us from our brokenness and sin, like the patient prayer of Saint Augustine’s mother, Monica.

Forgive our impatience, our unwillingness, to follow your example and our perennial blaming of you for bad choices that we have made.

Thank you for the many blessings and your patient willingness to offer us light in the night-time of our obstinate youth.

In the power of your Holy Spirit, turn our hearts to your example of patience. Remove the blinders of failing youth and grant us eyes that see, ears that hear, and hands that serve in the midst of much hardship.

In Jesus’ precious name, Amen.

Monica Prayer

Also see:

The Face of God in the Parables

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/Janu_2023 , Signup

The post Monica Prayer appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

January 27, 2023

Applying Patience

You also, be patient.

Establish your hearts,

for the coming of the Lord is at hand.

(Jas 5:8)

By Stephen W. Hiemstra

In the parables examined, we begin to see the importance of God’s patience.

In the Parable of the Two Builders, we find patience associated with good planning and expert workmanship. The expert builder plans for the flood that, though unexpected, is expected over the long haul. Laying a foundation on a rock speaks directly to the current concern about global warming because greater turbulence in weather is at the heart of the concern.

In the Parable of the Sower, we see that the occupation of the farmer requires patience. Farming requires patient planning and a willingness to invest time and effort in a crop that is from the outset hidden. What impatient person would save the seed from the previous harvest, prepare the soil, weed around the plants, and wait for months for a new harvest?

In the Parable of the Talents, we learn to take risks to advance the Kingdom of God while we wait patiently for the Lord’s return. Attitude matters. A fearful person is not likely to take risks for an uncertain outcome and the rate of return is substantially diminished just because of their fear. God’s abundant generosity allays our fear and permits us to prosper in good times and bad.

In the Parable of the Ten Virgins, we again see the need to plan patiently for every contingency. The urgency of our patient planning is shown to be the key to entrance into the wedding feast, a metaphor for heaven. Anyone who has helped prepare a wedding can attest to the eagerness and foolishness of emotionally-charged young people. Even in periods of utter spontaneity, we are cautioned to plan ahead.

Patience in the Early Church

Lessons about patience played an important role in the history of the church. Alan Kreider (2016, 1-2) observes:

“Patience was not a virtue dear to most Greco-Roman people and it has been of little interest to scholars of early Christianity. But it was centrally important to early Christians…The sources rarely indicate that the early Christians grew in number because they won arguments instead they grew because their habitual behavior (rooted in patience) was distinctive and intriguing. Their habitus…enabled them to address intractable problems that ordinary people faced in ways that offered hope.”

Think about it. The upper class of Roman society was known, not for patience, but for drunken orgies. In such a society, people offering sober, patient assistance to those victimized by such leaders would stand out and garner admiration. Kreider (2016, 19) writes:

“When people seek to follow Christ, according to Origen. God forms them into people who embody this patience. Christ’s followers are not in a hurry; they listen carefully the the word is read and preached, and they patiently call to account straying Christians who attend worship services irregularly. Patient believers trust God. When they are subjected to peritential discipline, they patiently bear the judgments made about them, where they have been rightly or wrongly deposed.’”

The nature of Christian worship is to engender patience and habits that improve daily life.

While worship can impart good habits, Donald Dayton (2005, 122-123) observed that periods of revival of the faith are often followed by reversals as “children growing up under such restraints experience them primarily as factors aliening them from their peers and society.” In seminary I noticed a stark difference in the attitude of preachers kids from missionary kids in which the preachers kids exhibited the response noted by Dayton while the missionary kids more clearly witnessed the fruit of their parent’s sacrifices and developed a strong faith of their own.

Current Backsliding

If modeling God’s patience is of immediate personal benefit, as demonstrated in research associated with the Marshmallow Test, and long term benefit to the church, as argued in Kreider’s study of the early church, why is our society so negligent in teaching personal discipline to our own children? This backsliding on patience can be attributed to the influence of cell phones, advertising to promote mindless purchasing, and the coronavirus pandemic on children’s own behavior. Or it may be simply a byproduct of inattention and parental prioritizing of other goals. One way or another, the impatience that we routinely observe today is clearly detrimental to the spiritual life and to the prudence use of resources in daily living. And our children’s test scores show it.

Example of Saint Augustine

Rather than end this reflection on a sour note, let me turn back the clock to another period when impatience seemed rampant.

Saint Augustine lived in the fourth century in North Africa and was the model of crass Roman debauchery by his own admission as a young man. Augustine (Foley 2006, 10) pictures himself as an initially lazy student who received frequent beatings, but we are quickly introduced to a pious Monica, his mother, who seeing her son engaging in self-destructive and sinful behavior resorted to unceasing prayer. Augustine writes:

“The mother of my flesh was in heavy anxiety, since with a heart chaste in Your faith she was ever in deep travail for my eternal salvation, and would have proceeded without delay to have me consecrated and wash clean by the Sacrament of salvation.” (Foley 2006, 12)

Still, it is paradoxical to observe one of the great philosophers of the church saying: “I disliked learning and hated to be forced to it.”(Foley 2006, 13). Although Augustine was schooled in rhetoric, like todays attorneys, he was by his own admission not converted with arguments, but by the patient prayers of a devout mother, Monica.

Reference

Dayton, Donald W. 2005. Discovering An Evangelical Heritage (Orig. Pub. 1976). Peabody: Hendrickson.

Foley, Michael P. [editor] 2006. Augustine Confessions (Orig Pub 397 AD). 2nd Edition. Translated by F. J. Sheed (1942). Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

Kreider, Alan. 2016. The Patient Ferment of the Early Church. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic.

Applying Patience

Also see:

The Face of God in the Parables

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/Janu_2023 , Signup

The post Applying Patience appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

January 24, 2023

Plantinga Defends Confessional Faith, Part 1

Alvin Plantinga. 2000. Warranted Christian Belief. New York: Oxford University Press. (Goto Part 2; Goto Part 3)

Alvin Plantinga. 2000. Warranted Christian Belief. New York: Oxford University Press. (Goto Part 2; Goto Part 3)

By Stephen W. Hiemstra

Part 3 of my Longfield review ended with a rather frustrating assessment:

“The weakness in the evangelical position is philosophical: very few PCUSA pastors and theologians today subscribe to Scottish Common Sense Realism. If to be postmodern means to believe that scripture can only be interpreted correctly within its context, then we are all liberals in a Machen sense. A strong, confessional position requires philosophical warrant—a philosophical problem requires a philosophical solution—which we can all agree upon. In the absence of philosophical warrant and credibility, the confessions appear arbitrary—an act of faith.”

For most of the period since 1925, evangelicals have had a bit of a philosophical inferiority complex—having to take on faith that the confessional stance of the church since about the fourth century was not defensible in a rigorous philosophical sense. It is at this point that Alvin Plantinga’s Warranted Christian Belief becomes both an important and interesting read.

The philosophical problem is more specifically found in epistemology—how do we know what we know? Because Christianity is a religion based on truth claims, epistemology is not just nice to know—it is core tenant of the faith. For example, Jesus said:

“If you abide in my word, you are truly my disciples, and you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.” (John 8:31-32 ESV)

Being unable after 1925 to agree on the core confessions of the denomination, the Presbyterian Church (USA) and evangelicals more generally were placed on the defensive. Faith increasingly became private matter as more and more the denomination withdrew from public life, from active evangelism and missions, and from teaching about morality. Later, unable to meet the modern challenge, the denomination came to be coopted by postmodern philosophies—if faith is simply a strongly held value, then it will crumble when confronted with more deeply held beliefs.

Introduction

Into this crisis of faith, Plantinga defines his work in these terms:

“This book is about the intellectual or rational acceptability of Christian belief. When I speak here of Christian belief, I mean what is common to the great creeds of the main branches of the Christian church.” (vii)

Notice that Plantinga has to both specify that he is writing about epistemology (theory of knowledge)—“intellectual or rational acceptability of Christian belief”— and specify what Christianity is—“what is common to the great creeds”. Plantinga expands on this problem saying:

“Is the very idea of Christian belief coherent?…To accept Christian belief, I say, is to believe that there is an all-powerful, all-knowing, wholly good person (a person without a body) who has created us and our world, who loves us and was willing to send his son into the world to undergo suffering, humiliation, and death in order to redeem us.” (3)

In other words, in his mind the measure of the depth of this crisis of faith extends to the very definition of the faith.

Background and Organization

Alvin Plantinga wrote Warranted Christian Belief while working as the John A O’Brien Professor of Philosophy at the University of Notre Dame [2]. He writes in 14 chapters divided into 4 parts:

Part 1: Is There a Question? (pages 1-66)

Kant

Kaufman and Hicks

Part 2: What is the Question? (67-166)

Justification and the Classical Picture

Rationality

Warrant and the Freud-and-Marx Compliant

Part 3: Warranted Christian Belief (167-356)

Warranted Belief in God

Sin and Its Cognitive Consequences

The Extended Aquinas/Calvin Model: Revealed in Our Minds

The Testimonial Model: Sealed in Our Hearts

Objections

Part 4: Defeaters (356-499)

Defeaters and Defeat

Two (or More) Kinds of Scripture Scholarship

Postmodernism and Pluralism

Suffering and Evil

Plantinga lays out his argument in a lengthy preface and follows his chapters with an index.

Plantinga’s book focuses on two main points which he describes as:

“An exercise in apologetics and philosophy of religion” where he answers a “range of objections to the Christian belief”; and

“An exercise in Christian philosophy…proposing an epistemological account of Christian belief from a Christian perspective.” (xiii)

In other words, Plantinga responds to objections the faith and lays out a model for understanding the philosophical acceptability of faith—an idea that he calls “warrant”. Plantinga defines warrant as:

“warrant is intimately connected with proper function. More fully, a belief has warrant just it is produced by cognitive process or faculties that are functioning properly, in a cognitive environment that is propitious for the exercise of cognitive powers, according to a design plan that is successfully aimed at the production of true belief.” (xi)

The core discussion of warrant lays out what he refers to as the Aquinas/Calvin model of faith. He writes: “Thomas Aquinas and John Calvin concur on the claim that there is a kind of natural knowledge of God.” (170). This innate knowledge of God given at birth he refers to as a “sensus divinitatis” which is triggered by external conditions or stimuli, such as a presentation of the Gospel (173).

Assessment

Alvin Plantinga’s Warranted Christian Belief is an important contribution to epistemology because he meets the objections to faith head on and offers a plausible explanation for why Christian faith is reasonable, believable, and true. Christians need to be aware of these arguments both to know that their faith is defensible and to share this defense when questions arise.

Part of this argument is that if the existence of God cannot be logically proven and cannot be logically disproven then it is pointless to talk about logical proofs—the modern challenge to faith is essentially vacuous—empty without philosophically based merit. Faith rests on what is more reasonable and more consistent with experience—what beliefs are warranted, not mathematical proofs. From Plantinga’s perspective, we accordingly do need not be defensive about our faith.

In this review, I have outlined Plantinga’s basic presentation. In part 2, I will review the arguments against faith and, in part 3, I will look at Plantinga’s model of faith in greater depth.

Footnotes

Longfield Chronicles the Fundamentalist/Liberal Divide in the PCUSA, Part 3 (http://wp.me/p3Xeut-11i)

[2] http://philosophy.nd.edu/people/alvin....

In financial modeling of complex firms, the rule of thumb is that it takes a model to kill a model—managing the firm without a model threats firm profitability and ultimate survival.

Plantinga Defends Confessional Faith, Part 1

Also see:

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/Janu_2023 , Signup

The post Plantinga Defends Confessional Faith, Part 1 appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.