Guy Tal's Blog, page 4

September 19, 2018

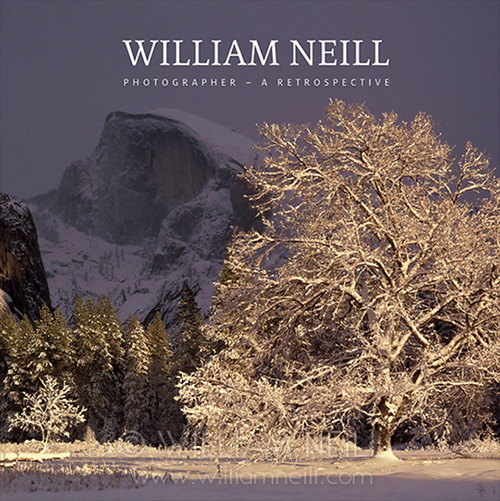

William Neill / Photographer – Retrospective

Searching for a respite from grief, I backpacked through the wilderness and scrambled up the peaks with a near-desperate vigor. Long, hard hikes temporarily soothed my pain and helped me to fall into exhausted sleep at night. At some deep level, the beauty of my surroundings seeped into my subconscious—the lush colors of a meadow dense with wildflowers, the energy of a lightning storm, the clarity of a turquoise lake, the splendid perspective from a mountain peak. ~William Neill

Note: I wrote this post to pay tribute to William Neill—a photographer whose work and writing influenced mine. I have not had the pleasure of meeting Neill in person, and I have absolutely no financial interest in the books I reference. However, I am both an admirer of Neill’s work, and a collector of photography books, which is why I am recommending his book, William Neill / Photographer — A Retrospective.

In my early days as a photographer (by which I mean the years after I recognized that photography has become more than just a casual hobby), there was no such thing as a public Internet, no cellular phones, and no easy means of sharing photographs with the world. Even after the advent of public Internet, when we still used dial-up modems (I’m sure those of my generation still remember the characteristic screeching sound of modems initiating a connection), bandwidth was limited, and the kinds of photographs we casually share today would have taken a long time to transmit. In those days, the predominant media for landscape photography were magazines and coffee table books. And I do miss those beautiful books.

One of those “must have” books, at least for landscape photographers in the American West, was Landscapes of the Spirit by William (Bill) Neill. The book is sadly out of print now, but is still available in eBook form. One thing that stood out to me in Landscapes of the Spirit was Neill’s introduction, in which he describes his path as a photographer, and how the tragic death of his brother influenced his work. In that, the book inspired me to not hold back, to be willing to “go there” when writing about some of my own work and the motivations behind it.

Neill did not rest on his laurels in the years since Landscapes of the Spirit. He is a long-time columnist for Outdoor Photographer Magazine, and has published a number of books over the years. The latest among these books—William Neill / Photographer — A Retrospective—deserves special mention. The Retrospective is an impressive book, both in appearance and in content. It is a beautifully printed, large (11.6″ x 11.6″) hardcover book, which is not common these days. Most important, because the publisher had gone out of business, only a limited number of copies remain. With introductions by Art Wolfe and writings by John Weller, as well as Neill himself, this is a very enjoyable book, and, to me, a bit of a throwback to the days when I loved spending intimate time with a large photo book—a much more satisfying experience (to me, at least) than watching images scroll by among myriad distractions on a social media stream.

The Retrospective includes some of the images in Neill’s original classic,Landscapes of the Spirit, and many more from recent years. It is a worthy tribute to a great photographer, and the best collection of his works in one volume. If purchasing directly from Neill, you will also have the benefit of having him autograph your copy.

UPDATE: When Bill read this post, he asked me to mention that he still has a few print copies of Landscapes of the Spirit. If interested, please contact Bill for information.

(Click image for more information on William Neill’s website)

(Click image for more information on William Neill’s website)

August 31, 2018

A Tombstone in Your Hands

My sincere gratitude to those of you who support this blog on Patreon.

For those who do not: if a small donation is within your budget, please consider becoming a patron.

Every little bit helps and is greatly appreciated.

Thank you!

Guy

Believe me, that was a happy age, before the days of architects, before the days of builders. ~Lucius Annaeus Seneca

Introducing his book, Desert Solitaire, Edward Abbey wrote, “most of what I write about in this book is already gone or going under fast. This is not a travel guide but an elegy. A memorial. You’re holding a tombstone in your hands.” Without intending it, I realized a few years ago that the same has become true of many of my photographs.

It is the nature of landscape photography that we often portray things prone to crumbling, erosion, death, or other forms of transformation or destruction attributed to natural forces. If it was not for these forces, the scenes we photograph themselves would not exist. But these are not the causes of the destruction that Abbey writes about. He is referring to the destruction of natural things—both physical and experiential—by humans, often for short-sighted or ignoble reasons. The same is true for those photographs I refer to above.

Some of my photographs inspired otherwise-uninspired photographers to sleuth the places where these photographs were made, to make copies of my compositions (and to claim these copies as their own), to claim bragging rights for having found my “secret” spots, to advertise these places to the world, and in so doing to unleash stampedes of yet more people—often other photographers—upon these places. On three occasions I can name, natural formations I discovered were destroyed by people, either by nefarious intent or by overuse, and I suspect I could find more if I scoured my archives. On other occasions, increased visitation also resulted in “development” of parking areas, toilet facilities, interpretive signs, “improved” roads and trails, disruptions to wildlife, regulations, and prohibitions (almost always limiting or eliminating camping).

Speaking about this concern with fellow photographers, outdoor writers, conservation advocates, employees of the National Park Service and of other agencies, a point commonly raised is this: to advertise and to “develop” these rare and wild places is a good thing because if more people see them, more people will become motivated to advocate for their preservation. Although not obvious, the first part of the argument, by virtue of being true, negates the second part, at least when it comes to truly wild and sensitive places. It’s true that social sharing, development, and increased use of a wild place means that more people will see it, but no people will ever again experience it as a wild place.

Conservation efforts require political action, and our political climate has become hostile to such efforts in recent years. Some claim that photographs of such places help conservation efforts. While it’s true that some photographs indeed play an important role in such efforts once they become politically feasible, the great majority of landscape photographs do not. Even if such places gain some form of legal protection, what ends up being preserved is not the place, but a different place—a place where experiences that were previously possible, no longer are.

One person suggested that I am being selfish in withholding information about certain places, denying others the experience that I had. This is an untenable argument because the experience I had was derived, in a large part, from discovering the place without having prior knowledge of it, and in equal part from the fact that when I discovered the place, it looked wild, sounded wild, smelled wild, and felt wild. To popularize such a place, is to guarantee that you will not have the same experience that I had. More than that, when such places become popular, the experience I had can no longer be had by anyone else, ever again.

To be selfish is to lack consideration for others. I don’t believe that I am being selfish by refusing to disclose such locations. In fact, I believe the exact opposite. By refusing to be complicit in making these places known and popular, let alone “developed,” I am preserving for others the ability to discover these places for themselves, and to experience them in their wild state, just as I have.

Indeed, who is more selfish? Is it the person who wishes to protect people’s ability to experience the thrill of discovery, the peace of being in a place unmarred by humanity, and the opportunity for solitude among wild beauty? Or is it the person who wishes to extinguish even the possibility of having such an experience, in place after place, until the experience can no longer be had at all?

I am adamantly opposed to sharing information about such places in public, and to further development in wild lands. There is no shortage of already-developed scenic places—more than a person may visit in a lifetime of travel. Such places are maintained and managed for the purpose of visitation by those unable or unwilling to venture into the wild but still want a taste of it. That is a good thing! However, there are not many places left where one may still experience wildness, solitude, freedom from the congestion and noise of humanity, and freedom from humanity itself. I believe that such places should be left alone to remain wild. Paraphrasing Wallace Stegner, that only few people will ever visit such wild places is not a detriment—that is precisely their value, and what makes them wild to begin with.

Photographer Harold Feinstein made this beautiful statement: “Photography has been my way of bearing witness to the joy I find in seeing the extraordinary in ordinary life.” To those obsessed with finding “secret” spots at all cost and to copy other people’s compositions rather than pursue creative expression: consider that, in making certain places and certain composition overly popular, we have accomplished the opposite of finding extraordinary things in ordinary places—collectively, we made some extraordinary places, ordinary.

Some may argue (perhaps as a means of allaying guilt) that in this day of GPS and social media, the popularization of scenic wild places is inevitable—a matter of when, rather than if, leading to such rationalizations as, “someone will reveal the location of these places, anyway, so it may as well be me.” Even if true, I think that there is great value in delaying the inevitable for as long as possible, rather than hastening it.

A Tombstone In Your Hands

My sincere gratitude to those of you who support this blog in Patreon.

For those who are not: if a small donation is within your budget, please consider becoming patron.

Every little bit helps and is greatly appreciated.

Thank you!

Guy

Believe me, that was a happy age, before the days of architects, before the days of builders. ~Lucius Annaeus Seneca

Introducing his seminal book, Desert Solitaire, Edward Abbey wrote, “most of what I write about in this book is already gone or going under fast. This is not a travel guide but an elegy. A memorial. You’re holding a tombstone in your hands.” Without intending it, I realized a few years ago that the same has become true of many of my photographs.

It is the nature of landscape photography that we often portray things prone to crumbling, erosion, death, or other forms of transformation or destruction attributed to natural forces. If it was not for these forces, the scenes we photograph themselves would not exist. But these are not the causes of the destruction that Abbey writes about. He is referring to the destruction of natural things—both physical and experiential—by humans, often for short-sighted or ignoble reasons. This same is true for those photographs I refer to above.

Some of my photographs inspired otherwise-uninspired photographers to sleuth the places where these photographs were made, to make copies of my compositions (and to claim these copies as their own), to claim bragging rights for having found my “secret” spots, to advertise these places to the world, and in so doing to unleash stampedes of yet more people—often other photographers—upon these places. One three occasions I can name, natural formations I discovered were destroyed by people, either by nefarious intent or by leading to overuse, and I suspect I could find more if I scoured my archives. On other occasions, increased visitation also resulted in “development” of parking areas, toilet facilities, and interpretive signs, “improved” trails, disruptions to wildlife, regulations, and prohibitions.

Speaking about this concern with fellow photographers, outdoor writers, conservation advocates, employees of the National Park Service and of other agencies, a point commonly raised is this: to advertise and to “develop” these rare and wild places is a good thing because if more people see them, more people will become motivated to advocate for their preservation. Although not obvious, the first part of the argument, by virtue of being true, negates the second part, at least when it comes to truly wild and sensitive places. It’s true that social sharing, development, and increased use of a wild place means that more people will see it, but no people will ever again experience it as a wild place.

Conservation efforts require political action, and our political climate has become hostile to such efforts in recent years. Some claim that photographs of such places help conservation efforts. While it’s true that some photographs indeed play an important role in such efforts once they become politically feasible, the great majority of landscape photographs do not. Even if such places gain some form of legal protection, what ends up being preserved is not the place, but a different place—a place where experiences that were previously possible, no longer are.

One person suggested that I am being selfish in withholding information about certain places, denying others the experience that I had. This is an untenable argument because the experience I had was derived, in a large part, from discovering the place without having prior knowledge of it, and in equal part from the fact that that when I discovered the place, it looked wild, sounded wild, smelled wild, and felt wild. To popularize such a place, is to guarantee that you will not have the same experience that I had. More than that, when such places become popular, the experience I had can no longer be had by anyone else, ever again.

To be selfish is to lack consideration for others. I don’t believe that I am being selfish by refusing to disclose such locations. In fact, I believe the exact opposite. By refusing to be complicit in making these places known and popular, let alone “developed,” I am preserving for others the ability to discover these places for themselves, and to experience them in their wild state, just as I have.

Indeed, who is more selfish? Is it the person who wishes to protect people’s ability to experience the thrill of discovery, the peace of being in a place unmarred by humanity, and the opportunity for solitude among wild beauty? Or is it the person who wishes to extinguish even the possibility of having such an experience, in place after place, until the experience can no longer be had at all?

I am adamantly opposed to sharing information about such places in public, and to further development in wild lands. There is no shortage of already-developed scenic places—more than a person may visit in a lifetime of travel. Such places are maintained and managed for the purpose of visitation by those unable or unwilling to venture into the wild but still want a taste of it. That is a good thing! However, there are not many places left where one may still experience wildness, solitude, freedom from the congestion and noise of humanity, and freedom from humanity itself. I believe that such places should be left alone to remain wild. Paraphrasing Wallace Stegner, that only few people will ever visit such wild places is not a detriment—that is precisely their value, and what makes them wild to begin with.

Photographer Harold Feinstein made this beautiful statement: “Photography has been my way of bearing witness to the joy I find in seeing the extraordinary in ordinary life.” To those obsessed with finding “secret” spots at all cost and to copy other people’s compositions rather than pursue creative expression: consider that, in making certain places and certain composition overly popular, we have accomplished the opposite of finding extraordinary things in ordinary places—collectively, we made some extraordinary places, ordinary.

Some may argue (perhaps as a means of allaying guilt) that in this day of GPS and social media, the popularization of scenic wild places is inevitable—a matter of when, rather than if, leading to such rationalizations as, “someone will reveal the location of these places, anyway, so it may as well be me.” Even if true, I think that there is great value in delaying the inevitable for as long as possible, rather than hastening it.

August 14, 2018

Take Yourself Seriously

The serious photographer today should constantly be seeking new ways of commenting on a world that is newly understood. Constant creativity and innovation are essential to combat visual mediocrity. The photographic educator should appeal to the students of serious photography to challenge continually both their medium and themselves. ~Jerry Uelsmann

Some people say that you shouldn’t take yourself seriously. I think that you should. In fact, if you take anything seriously, it should be your self, since it is the self that decides what else to take seriously. But there is more to it.

Certainly, to not take yourself seriously makes life easier. It may save you from disappointment, it may liberate you from taking responsibility for things, it may help you rationalize taking the easy path, it may allow you to dismiss those nagging what-ifs, it may relieve you of some worries, and it may unburden you from caring too much about anything. And, when you excuse yourself from caring, you also spare yourself such undesired feelings as frustration, anger, envy, regret, disappointment, grief, obligation, guilt, and others.

So, why should you take yourself seriously? For starters, without taking yourself seriously, you don’t just spare yourself negative emotions, you also forfeit (at least in degree of intensity) positive feelings, starting with a sense of self-worth. Also, when you don’t take yourself seriously, the whole do-unto-others thing—considered by many to be the foundation for all human morality—breaks down. If you don’t take yourself seriously, doing the same unto others means you don’t take anyone else seriously, either, and some people are very much worth taking seriously.

Caring deeply (which is the product of taking something—and therefore also yourself—seriously) is the foundation for any kind of deeply emotional experience. To feel strongly about some thing or some person, to a point where it elevates your life in a way that you cannot accomplish on your own, you must care deeply about that thing. Therefore, to not take yourself seriously is also to deny yourself profound emotional—even spiritual—experiences.

When you take something seriously, you become invested in that thing; you become interested in it, and motivated to make the most of your relationship to, or with, it. To take yourself seriously means to not settle for a mediocre existence, no matter how easy or carefree*; you gain the strength to not yield to lesser temptations and to not take the easy path if greater rewards may be found by investment of effort. To take yourself seriously means to seek to elevate yourself emotionally and intellectually, and to strive for a more meaningful living experience. Without taking yourself seriously, you may never muster the courage to take risks in order to better yourself or the things you care about.

To not take yourself seriously, and to avoid living deeply, while certainly easier than finding some comfortable niche and to persist there, is also to not make the most of your living moments and the opportunities available to you within the blink of existence that is your lifetime.

If photography is an important part of your life, I believe that the more seriously you take yourself, the more serious you should be about photography, too. It is a simple case to make: if you feel that photography makes your life better, then the more you invest in photography, the more photography will give you back in return. Being a voluntary activity, if photography did not reward you for time invested, I suspect that you would not be a photographer.

Photography can be a wonderful pastime, but it can also be a means to much greater and more rewarding ends. Why not make the most of it?

I write this after having been rebuked for being “too serious” in my writing, advised to “lighten up,” and asked, “what’s wrong with just having fun?” I think that the word “just” within the question, likely used without considering its implications, is ironic. But I think that there is a bigger issue at play, which is the attitude of some to gain popularity by appealing to people’s innate instinct to follow the path of least resistance.

For myself, I can only express my gratitude that no one—especially those in positions of influence—convinced me to “just have fun” in my early years as a photographer, when I was still struggling with doubts about how I should pursue photography. What I gained from nearly three decades of photographing seriously—with dedication and dignity, and striving to understand as much about photography and its expressive power as I could—is many orders of magnitude more rewarding than “just having fun.”

To those who wish to become more serious—about photography or anything else—but struggle to find the first, or next, step, I offer this advice: seek out places, activities, and people you feel are worth caring about; and among these find those things or persons who can challenge you, and let them.

* I expect that some who are committed to philosophies proclaiming that one’s goal in life should be to avoid suffering, and/or that the self is an illusion, may bristle at this notion. I address these philosophies, and why I disagree with them, in my upcoming book (expected to be published next year).

July 26, 2018

Making Memories

If I summon up those memories that have left with me an enduring savor, if I draw up the balance sheet of the hours in my life that have truly counted, surely I find only those that no wealth could have procured me. ~Antoine de Saint-Exupery

I went to visit with the canyon that has been a friend to me for all these years—the first of many canyons I came to know in this desert that is now my home, where I spent my first of many nights gazing into the cosmos through the arc of an alcove and felt free for the first time in my life; the canyon where, in the course of decades, I have come, time and again, to heal and to renew, to contemplate the great questions of life, to break down and to grieve, or for no reason at all—the canyon where the life I live today had begun.

Strange thing, a canyon: a place made of absence, the space between the cliffs—the nothing that is something.

I came burdened with the melancholy that has taken over my life about two years ago, when I contracted a mysterious illness.

I came burdened with the melancholy that has taken over my life about two years ago, when I contracted a mysterious illness.

I like to joke, sometimes, that I experienced my mid-life crisis when I was 19 (I was a conscripted soldier then). By that accounting, I am already on borrowed time. Awareness of my mortality has been a constant preoccupation since my teenage years, and I have made my peace with it long ago. At times I even yearned for it. Places like this canyon are where I—the person that I am today—was born, and where I hope I’ll someday spend my last moments of life. So much in theory. In truth, when I am in such places, I feel more alive and more grateful for my life than anywhere else.

My favorite tree may be the cottonwood. At times, I have been deeply enamored with aspens and ponderosa pines and others, although such affairs were always short-lived, usually lasting only until a time when find myself again in the company of a gnarled old cottonwood. The canyon is home to some of my favorite cottonwoods.

In an interview by the Smithsonian about his portfolio of cottonwood photographs, after expressing of his concern for the diminishing natural beauty of the West, Robert Adams was asked, “What is your basis of hope?” His response, in summary, was that he was hopeful because of “other people’s caring.” In a sense, I may be Adams’s antithesis: I am not hopeful, exactly because of other people’s uncaring. It is odd to me that, although Adams claims to be hopeful, his photographs to me are tinged with sadness. His work portrays in a decidedly-unflattering manner, human incursions into the Western landscape. While I, devoid of hope and riddled with pervasive sadness, find solace and meaning in beauty. I deliberately photograph those things—those achingly beautiful things—that persist defiantly in the face of such human incursions that Adams photographs, and as far away from these incursions as I can venture.

But enough of that. It’s time to walk.

Descending from the canyon rim by way of a small tributary, I enter the canyon. The mid-July heat made heavier by humidity from recent rains, and the familiar blend of smells characteristic of these riparian environments, overwhelm my senses. After walking in the relentless morning sun, I am drenched with sweat by the time I reach the blissful shade of the cottonwoods and canyon walls, wash my face and dip my feet in the stream. Last time I was here, the creek was iced over, the trees were bare, and all was silent—the kind of perfect and austere silence only possible when many miles away from humans and from the strongholds of humanity, in the desert, in winter. Now the place is alive with the songs of birds, the cawing of ravens, lizards in the undergrowth, the trickle of water, and the whisper of a light breeze in the verdant trees.

Descending from the canyon rim by way of a small tributary, I enter the canyon. The mid-July heat made heavier by humidity from recent rains, and the familiar blend of smells characteristic of these riparian environments, overwhelm my senses. After walking in the relentless morning sun, I am drenched with sweat by the time I reach the blissful shade of the cottonwoods and canyon walls, wash my face and dip my feet in the stream. Last time I was here, the creek was iced over, the trees were bare, and all was silent—the kind of perfect and austere silence only possible when many miles away from humans and from the strongholds of humanity, in the desert, in winter. Now the place is alive with the songs of birds, the cawing of ravens, lizards in the undergrowth, the trickle of water, and the whisper of a light breeze in the verdant trees.

In his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, Nelson Mandela wrote, “There is nothing like returning to a place that remains unchanged to find the ways in which you yourself have altered.” I realize that, in a sense, I am also the antithesis to Mandela: I don’t recall ever being to a place that remained unchanged from one visit to the next, nor feeling that I have not altered from one day to the next. Especially in places such this, I become acutely aware of how I have altered because, like me, these places morph and transform constantly with the passage of time and the cycles of seasons, with weather and erosion and light. What can I say? I have always been a dialectic and a recluse—it’s just how I’m wired—and in my current incarnation, I have never felt the slightest temptation to be anything else. To me, there is no greater freedom than freedom from other people, and I don’t expect to ever write an autobiography. My life, other than those aspects of it I choose to share in my work, is nobody’s business. But still, without a doubt, there are at least some dimensions of this place, and of me, that remain unchanged even as appearances do.

At the base of a cliff, a large Sacred Datura in bloom calls out to me, its large flowers as white and velvety as a fairy’s gown. I stick my nose into one of them to inhale its sweetness, and am instantly filled with a rush of memories, so numerous and vivid that I feel compelled to sit by the blooming plant to parse them out, to give each due attention, returning on occasion to smell another flower, and another. Most, as it turns out, take me to other times and other places in this desert. A few reach farther and deeper, to other lives—mine and others’—and those, upon further contemplation, bring tears to my eyes. Raising my head to look down the winding corridor ahead, the red rock, the trees, the water, tears of sadness are soon replaced with tears of gratitude. The effort of the walk in, the soreness and the sweat, no longer are part of my experience. I am in the world of the canyon, in body and mind.

Time to keep walking.

Rounding a sweeping gooseneck curve, I arrive at a large pool, now in shade after having been exposed to the sun in the hours before. Without a moment’s thought, as has been my custom when visiting here in the warm seasons, I remove my pack and my clothes and dive in. The water’s temperature is perfect to refresh after a long walk in the heat, but not too cold as to shock. After the recent floods, the water is deeper than usual, and I swim around, pausing to watch crawdads struggle up the small waterfall feeding the pool, and fallen leaves gliding down it.

Refreshed from my swim, I walk around to let the breeze and the sun dry me before resuming my walk. With time to study the rock and the plant life, I am delighted to find a small bat sleeping below a small ledge, and a few red monkeyflowers peeking from hanging gardens of maidenhair ferns.

Entering a narrower part of the canyons, the trees disappear, and the walls grow closer and taller. Every curve radiates a golden glow as reflected sunlight bounces off the red walls. The creek now flows over bare rock, the water weaving in smooth, sensuous, fluted pathways under my feet.

At a confluence with a small, unnamed, tributary, I leave the main channel and hike to an ancient Native American dwelling. All signs suggest it is a very old one, perhaps occupied by early Puebloan or Fremont people, making it as old as a thousand years, perhaps a couple of centuries beyond. Faded figures are pecked into the wall, difficult to discern at first—bighorn sheep, a snake (perhaps), and other figures I cannot identify, suggesting that this may even be an Archaic site, potentially dating the site as far back as ten thousand years or more. Someone more knowledgeable than me may be able to tell for sure, but other than a degree of curiosity, it doesn’t matter much to me. I am more interested in how these people lived than in who they were. Admittedly, my interest in human cultures—past and present—has always been more anthropological than tribal.

At a confluence with a small, unnamed, tributary, I leave the main channel and hike to an ancient Native American dwelling. All signs suggest it is a very old one, perhaps occupied by early Puebloan or Fremont people, making it as old as a thousand years, perhaps a couple of centuries beyond. Faded figures are pecked into the wall, difficult to discern at first—bighorn sheep, a snake (perhaps), and other figures I cannot identify, suggesting that this may even be an Archaic site, potentially dating the site as far back as ten thousand years or more. Someone more knowledgeable than me may be able to tell for sure, but other than a degree of curiosity, it doesn’t matter much to me. I am more interested in how these people lived than in who they were. Admittedly, my interest in human cultures—past and present—has always been more anthropological than tribal.

I return to my canyon and proceed further, stopping on occasion to stuff my backpack into a dry bag as I traverse some of the deeper pools. Despite the higher-than-normal water level, I am able to keep my head above water and my feet on the ground, although my clothes are completely soaked. No matter. Things dry quickly in the dry desert air.

In the early afternoon what were previously light cirrus clouds have morphed into thicker, grayer, and more menacing cumulus. It is monsoon season. A flash flood is a not-uncommon thing here in the summer months and into autumn, usually in the afternoon. Time to get out of the narrows. At the top of a steep and grassy sandy hill nestled at the nave of a hairpin curve in the canyon, is a deep alcove—my home for the night. No tent is needed. No sooner than my bed is made—a cushy inflatable pad and a light sleeping bag—a drizzle begins. Good timing.

Thunder is booming. I unpack the overstuffed sandwich I prepared before leaving my camp on the rim as the air becomes rich with the scents of wet earth and desert plants. Leaning against a large rock, I watch as a veil of thin trickles forms over the mouth of the alcove.

Muffled echoes of water and wind emanating from the canyon sound eerily like human voices. I’ve experienced this phenomenon enough times as to not be jarred by it.

I had hoped to see a flash flood coming down the canyon and waterfalls cascading over the cliffs, but the rain is soon over. As if on cue, the moment the rain stopped, a canyon wren bursts into bold cascading song reverberating off the canyon walls. Hard to believe that such a tiny bird can sing with such power.

I leave my pack and descend into the canyon again, mindful to remain close, where I can reach safety at the hint of a coming flood. Red spotted toads have appeared from wherever they were hiding. I spend the afternoon engaging in my usual canyon silliness—walking barefoot in the water and among the soft grasses, listening to music, making notes, conversing (or at least pretending to) with wrens and ravens, drawing the curiosity of lizards as they approach me gingerly when I am sitting perfectly still.

Evening finds me reading in my sleeping bag. As darkness sets, I prepare my little stove within reach for the morning coffee and watch as planets and stars begin to appear. I smile as I hear the familiar hooting of a great horned owl somewhere down the canyon. He, or she, will entertain me several more times in the coming hours.

I’m prepared to stay a couple of days if the weather looks threatening, but by morning the sky is a cloudless blue. After a quick breakfast I repack my belongings for the walk back. I take my time, savoring the sights and the scents, breaking often to examine rocks and critters, to let my sore back rest, or to just sit in some shaded spot to breathe in the desert.

In the late afternoon, not far from my vehicle and feeling a little adventurous, I decide to scramble up a steep chute and to walk the rest of the way along the rim, looking down at the creek and the cottonwoods. The effort proves greater than I had anticipated, and I feel proud and relieved when to emerge at the top. Storm clouds had gathered again and I enjoy the cooling breeze and the occasional drizzle.

Arriving at my vehicle, tired and overwhelmed with the experiences and beauty of the hike, I drive to stand of junipers, now richly fragrant after the rain. My small truck camper feels like a luxurious palace after a night in the alcove. After washing up and changing into dry and clean-smelling clothes, I set about cooking dinner, replaying in my mind the events, sights, sounds, and smells of the previous couple of days, glad and grateful for these new additions to my trove of favorite memories.

I consider whether words can fully describe such experiences and conclude that some things can’t be entirely learned from second-hand accounts, no matter how eloquent, and can only be known by in-person experience, and I feel grateful yet again.

July 5, 2018

The Implicit Contract

A work of art is the unique result of a unique temperament. Its beauty comes from the fact that the author is what he is. It has nothing to do with the fact that other people want what they want. Indeed, the moment that an artist takes notice of what other people want, and tries to supply the demand, he ceases to be an artist. ~Oscar Wilde

There are two magazines that I contribute to regularly—LensWork, and On Landscape. They are different publications in many ways (one is a printed magazine, the other electronic; one focuses on landscape photography, the other inclusive of all genres; etc.). Both publications are created and curated with care and passion by their publishers, and both are subscription-based, rather than being funded by advertising, making them a pleasure to read without distraction. More to the point of this post, these publications have another thing in common, which is this: both foster serious and intelligent discussion and commentary about photography beyond just technical topics.

I was pleased that my recent article in On Landscape, titled, “Morality and Realism in Photography,” elicited some excellent and well-thought-out responses and led to an offline discussion with the publisher, Tim Parkin, that resulted in a follow-up article written by Tim, titled, “Realism and Honesty in Photography.” In his article, Tim proposes that there is an implicit contract between photographers and viewers, which he describes as “the ‘fair’ expectation that what you are being presented with meets certain criteria even though there is no explicit contract.”

I believe that such an implicit contract in photography exists (or should exist) only in some contexts, and that there is no such contract that applies unequivocally to all photographs. To the point of this article: I believe that there is no such implicit contract when it comes to photographs intended as art (indeed, to anything intended as art).

To suggest that artists, in any medium, should tailor their work to viewer expectation is to suggest that art should become stagnant. This is because all advances in art and artistic expression originated with artists who defied conventions, broke with traditions, and did things in new ways. In that sense, novel exceptions are to the evolution of art what mutations are to the evolution of life—not always successful, but wen they are, leading to new forms.

It can be said that we have an implicit contract with news media to be truthful in their reporting, although we know that some of them, by design, offer biased and sometimes even false views. We may believe that we have an implicit contract with physicians to treat everyone equally, but such a view does not reconcile with some surveys, such as one that found physicians less likely to prescribe certain drugs to family members than to random patients for the same condition. We want to believe that we have an implicit contract with law enforcement officers and with the judicial system to treat the everyone fairly and equally, but studies show significant biases (racial, demographic, etc.) in the likelihood of being arrested for certain crimes, and in the severity of court-imposed penalties. To wit, trusting an implicit contract without further critical assessment may lead to error and disappointment.

When it comes to photography, I agree completely that viewers have a legitimate expectation—an implicit contract with the photographer—that what they are shown is a truthful representation (to the extent that this is possible). And certainly, when such an expectation is not met, viewers have every right to be upset and to feel like they have been deceived.

However, when it comes to art, there is no such contract—no legitimate expectation of truthful representation. Indeed, if all one could do with photography is to represent appearances as anyone else would see them, photography would be a decidedly-unsuitable medium for art. Art, deriving from the same origin as “artificial,” by any formal definition, is a product of human skill and imagination, and is not strictly defined by any other criteria. Skill and imagination are what philosophers call “necessary and sufficient conditions” for something to be considered art. More explicitly, truthfulness, however you choose to define it, is not one of these conditions.

Where there is an implicit contract that is not honored, the injured party has a legitimate reason to feel deceived. But to suppose there is an implicit contract where there is no plausible reason to assume so, is to be gullible or at least uninformed. For a variety of reasons, such misinformation is more pervasive in photography (when used to make artistic creations) than in other media. As such, I consider it my duty as a photographer who considers himself an artist, to inform that such a contract should not be assumed for any photograph presented as art. And I urge my fellow photographic artists to similarly step up. Misinformation among potential audience for photographic art is not in our favor and may lead to preventable disappointment.

As I wrote in my On Landscape article, “Readers know to apply different modes of appreciation to works of journalism and to works of fiction. Moviegoers can easily tell the difference between a documentary film and a fictional one. There is no reason why these same people can’t be encouraged to make the same distinctions when studying photographs.” Not only will such educated viewers be less prone to disappointment, but they also will expand the range of rewards they will get from photography. The fact that a fictional novel is not as truthful as an academic textbook does not make one unequivocally “better” than the other, but it does mean that the two should be read with different expectations and reward readers in different ways. Photography has a broad range of expression—both factual and expressive. To allow people to persist in their belief that photographers are only “allowed” to use a small part of that range is not only detrimental to artistic expression, but it also is untenable: photographs that do not represent “real” appearances not only exist but are common, and there is nothing and no one who can change that. We should stop pretending that this is not the case, or that this is a bad thing.

With that said, I would like to explain the extent of what Ansel Adams called “departure from reality” in my own work, and without judgment of other people’s work who may choose differently. I consider my photographs as visual journal entries. Personal journals describe real events, but they do so in a subjective way: they not only express what happened, but how it affected the writer. In a personal journal, the event and the feelings it inspired in the writer are both true, even if another person may have had a different impression of the same event.

I don’t photograph to make photographs, nor to commemorate events just because their appearance is attractive. I photograph to express moods inspired by encounters with things and places that are personally meaningful to me. As such, I have no reason to depart too far from the sources of my inspiration, however what I choose to show you and how I choose to portray it are entirely subjective and not likely to match what you would have seen or felt in the same circumstances.

Allow me to also address the ignorant stigma of “manipulation.” All art, being by definition a product of human skill, is manipulation. A view occurring naturally or randomly, presented without application of human creativity, by definition is not art. What may not be obvious from this definition is that a photographer’s primary tool for manipulation is visual composition: the deliberate arrangement of visual elements within the frame by such choices as perspective, what lens to use, what lighting or weather conditions to match with a given subject or scene, and others. All such decisions and techniques are innate to the photographic process and require no means other than a camera and lens; and all can be used to express things that are truthful and things that are not.

Processing the captured photograph is a secondary means for manipulating photographs. In my work, my purpose in applying processing tools is not solely aesthetic appeal. Rather, my purpose is to arrive at the (truthful) emotional effect I experienced and wish for my images to impart, using the (real) properties—colors, textures, lines, etc.—of the things in my photographs. Note that this does not mean that I portray these things as-is. I will emphasize and enhance those aspects of the captured photograph, so they best fit my expressive goal, but I—by choice—will not to create images from arrangements that are not possible in a single photograph. This is because what I wish to express ensues directly from real things.

These are choices I make to match my reasons and purpose in practicing photography, and not because I feel bound by any implicit contract. Others may, and do, make different choices or have different purposes in photography. So long as such photographs are presented as art, no implicit contract can be assumed, because to do so is gullible and will almost always lead a viewer to incorrect assumptions.

June 26, 2018

Transitions

This article was created from notes I prepared for a talk about my evolution as a photographer. I hope it may be useful to those pursuing a similar journey.

My wish is to offer original content on this blog, free from advertising and other annoyances. Please consider supporting me on Patreon, or using the Donate link on the right, if you prefer PayPal. Every little bit helps, and very much appreciated.

Landscape: only your immediate experience of the detail can provide the soil in your soul where the beauty of the whole can grow. ~Dag Hammarskjöld

Like most photographers, art was not on my mind when I first picked up a camera. The transition occurred slowly, without deliberation or sudden epiphanies. For much of my life, art was a distant notion: I never played a musical instrument, never painted, and only visited museums on school trips. In school, I focused on grades; in the military on maintaining my sanity; in the academy I had no focus at all; and, as a young adult, my primary preoccupation became whatever job I happened to hold. With one glaring exception, I convinced myself that I loved whatever I happened to be good at and that earned me praise—being a good student, a good teacher, a good technologist, a good manager. The exception? I was never a good soldier.

I feel like I have been different people at different times. Still, one thread ties everyone and everything that I have ever been: the awe, fascination, and peace I always feel in wild places, away from the pettiness and banality of so many human endeavors, away from the cacophony of cities, away from the odd rituals of society. These places and my experiences in them remind me of myself, and allow me to be myself. They are where I go to heal, to set aside the bothersome tasks of life, to contemplate big questions and important decisions. Whatever forces dwell in such places never fail to provide me with solace when I need it, always elevate my spirit and allow me to think clearly and to feel without reservation or pretense.

For more than three decades, I’ve been making photographs on solitary explorations. Early on, I sought to just share with others the things I came across that I considered beautiful or interesting. I recall, after each trip, placing my exposed film in a paper envelope and slipping it through the night deposit slot at the local photo lab. After a day or two of nervous anticipation I’d pick up the developed slides and rush to find a quiet place to review them. For many years, other than my times in the wild, those were the most pleasurable moments of my photographic process. The wait sweetened the joy, and the slides were their own reward.

Along with a stressful career and the rise of what later became “social media,” came a dark age of creative adolescence. The frustrations of corporate life would not be contained to time spent at the office and, for more than a decade, bitterness infected almost all aspects of my life. Photography, practiced hurriedly and in short spurts, became a trophy hunt focused on the outcome rather than the experience. Despite insisting that photography was my “creative outlet,” in fact it was a means for commanding attention, for competing and impressing and making others envious. Perhaps some perversion of logic in my mind believed that if others thought I lived a meaningful and purpose-driven life, that was a good enough substitute to actually living a meaningful and purpose-driven life. The value I placed on my forays into the places I loved became dependent on the images I was able to bring back. I no longer “wasted” time idling in thought, admiring intimate subtleties, or contemplating life, as I have in my younger years, roaming alone in places that no longer exist. I was consumed by an incessant and insatiable quest for the next “keeper.” On any given outing, I was in a mad rush to get to the “right” place at the “right” time for the “right” light. And, sure enough, I got the “right” photograph, but I came back no more inspired than when I left. My images in those days were aesthetically pleasing but meant little as works of creative expression. Their appearance—bold and sharp, but lacking in grace, subtlety, and nuance—reflected the uninspired person I became. At times, I would come home from the most sublime of places feeling angry and bitter if the sunrise was not picture-perfect or if clouds did not materialize as I had hoped. In fact, my anger had little to do with photography and more with the visceral sense of the diminishing hours separating me from the Monday morning commute and the work week to follow.

But, on occasion, I still experienced meaningful moments. These often correlated with the rare opportunity to spend prolonged time away from the office, with times of great sadness or happiness that overshadowed for a period the nagging of mundane concerns, and with the pondering of important life decisions and significant events. Those images were of a different nature—they were distinctively quiet and somewhat abstract, the circumstances of their making infinitely more memorable.

I realized, not for the first time, the destructive effect of attempting to live as someone that I was not, forcing myself into the expectations of others, blindly accepting the imperatives of competition and one-upmanship dictated by the ever-rushed result-driven corporate life that consumed most of my waking hours. It took me some years to finally admit to myself that in my pursuit of financial success, I had strayed from the path I vowed to pursue after I left the military and my homeland. More important, I suppressed the memory of the reasons for these decisions—perhaps the greatest and most hard-won life lessons I ever learned.

One memorable Saturday, tired and frustrated after a long week at work, I sat on my basement floor with a large trash bag and several filing boxes filled with slides. Some hours later I had culled several thousand of them. As I studied page after page, memories came to life—times, both happy and sad; people and places and events and discoveries. From among the thousands of images of generic sunrises and sunsets and iconic postcard compositions, emerged the few that filled me with pride and sent my heart soaring; that reminded me of moments and lessons and experiences I cherished, and of everything that was important and memorable in those years. They were not images of grand scenes or majestic feats of geography and light. Rather, they were private mementos—simple and honest and quiet and profound. They were also reflections of someone that I missed—someone that I used to be and whose voice still echoed from the far recesses of distant memories. By the time I had gone through all the boxes and purged them of everything that was not me, I was in tears. With these realizations came a paralyzing fear that life as a professional adult may mean losing, for the rest of my days, the essence of the proud and defiant person who was willing to risk all for a chance at a meaningful life. I felt an overwhelming desire to return to the wild, humbled and grateful, in search of peace and answers and courage.

Shortly after, I resigned my lucrative corporate job and went to live in the desert. The (now considerably repressed) cynic in me is well aware of the myth of a thinker going into the desert for answers or redemption, and you will be well within your rights to stop here and dismiss it as a cliché. But if you are still reading I will give you at least one reason to continue, which is this: it worked.

Desert Bliss

Prints available for purchase.

I stopped photographing the same things that others did and began to venture into anonymous places—places that harbored secrets and quiet beauty, where new lessons awaited and where I could be by myself. On many such excursions I made no photographs at all, but I always gained from the experience. I sought remote settings where I could just sit and contemplate in quiet reverence. I spent nights under the stars for the sheer joys of looking out into the universe, listening to the sounds and silences of the wild and letting my thoughts wander. I ventured out in every kind of weather and terrain, not for the chance of “good” light, but to indulge in primal wildness, to exercise and saturate every sense as intensely as I could bear, and to savor the intoxicating taste of freedom.

More and more, my images reflected moods and stories, rather than places and things. I lost interest in all social and competitive aspects of photography and, instead, found my life enriched by the mere practice of it. I sought to learn about the things that made images meaningful and how I could better express the depth of emotion I felt when making them. It was then that I began to refer to my work as art without the nagging sense that it may not be worthy of the term. In embracing art, I gradually began to understand its power in articulating and expressing my most intimate and personal stories, to myself before anyone else.

I was a writer before I became a “serious” photographer, and I knew how much more expressive writing can be when the writer is versed not only in the descriptive powers of words, but also in their aesthetics. A good metaphor can express more in a sentence than didactic prose can express in an entire page. I already knew how to express myself creatively in words; and despite an ever-increasing interest in photography, writing still seemed to me a more distinguished medium for personal expression. In order to consider photography as important as writing, it needed to transcend the limitations of language (for the philosophically-minded: yes, Wittgenstein had something to do with that realization): it needed to be able to express things inexpressible in words.

When I realized that I wanted to do more with my photographs than to document the places I’ve been to and the things I’ve seen, I found myself at a loss for direction. I knew the power of expressive images from previous encounters with great photography, and I set out to decipher what it was that made them so moving—the visual language in which they were expressed. In the beginning, I was like a toddler learning awkwardly to communicate my desires. I knew how to utter simple nouns and adjectives—tree, colorful, sunrise, pretty, rock—and, like a toddler, I also knew how to crank up the volume and demand attention through extreme perspectives and retina-scorching colors. But, these were not expressive of the intimate interactions I have with the wild. Like anyone learning a new language, I did not know how to express subtlety, complexity, and nuance; how to extend the scope of my visual stories beyond momentarily satisfying anecdotes. I wanted to widen the plots of my stories beyond simplistic utterances like “look at this view,” or “here’s something pretty.” I needed to expand my visual vocabulary—I needed to learn the visual equivalents of grammar and punctuation, symbols, metaphors, rhyme. I knew what a visual depiction looked like, but what does a visual poem look like? a visual novel? a visual haiku?

Of course, I knew how to make beautiful records of already-beautiful subjects. I also knew that I could impress with feats of skill and technology and artificial visual effects; but those were still far removed from the emotions, thoughts, and revelations I experienced and wanted to relay in my images, and that made them my stories, distinct from those of others who may have also visited the same places.

Searching for insight, I studied the journals and biographies of artists I admired, and academic texts about art history and composition and visual perception. Most of these were not specific to photography, and so I also learned a bit about the mechanisms of human vision, and bits of disciplines sometimes grouped as cognitive science—particularly philosophy, psychology, and neuroscience. The more I read and researched, the more the language of images began to take shape. I discovered how visual relationships can translate into emotions, how the direction of lines can affect mood and imply motion and force, and how colors and angles and shapes and patterns and textures and visual relationships assume weight and meaning.

With the knowledge I acquired, I strived to create images that were more than just aesthetic or interesting—images that could speak to my intimate impressions of, and in, the land, beyond just superficial aesthetics. I wanted to make images that reflected a lasting and complex relationship that evolved in the course of decades, through times of bliss and conflict, love and fear and pain—a relationship as meaningful to me as any I’ve had with another person. I realized that I had to separate my own stories from those inherent in the things I photographed and to look inward.

My goal became to evolve my relationship with wild places; to experience and then to express in photographs the dimensions of my experiences that I found worthy of expression—moods, revelations, discoveries, inspirations, musings, and lessons arising from my encounters and interactions with the wild.

Keep Walking

June 2, 2018

On Awe and Cynicism

There are moments, and it is only a matter of a few seconds, when you feel the presence of the eternal harmony … A terrible thing is the frightful clearness with which it manifests itself and the rapture with which it fills you … During these five seconds I live a whole human existence, and for that I would give my whole life and not think that I was paying too dearly. ~Fyodor Dostoevsky

A few days ago, I watched with great interest a presentation by artist Benjamin Grant, sponsored by the Long Now Foundation. Among other topics, Grant discussed the feeling of awe, saying that “awe happens when you are exposed to something perceptually vast,” which may explain the circumstances in which one may experience awe, but not what awe is or what it feels like. It made me think of my own experiences of (what I believe to be) awe and the ways in which these experiences influenced my thoughts, my decisions, and consequently my life.

Considering that our languages have evolved over tens of thousands of years, and how central emotions are to our experience, you might expect that we’d have a clear and unambiguous way to define and describe such things as awe, but that is not the case. In fact, we do not even have precise terms for every variation of emotion that we are capable of feeling, let alone strict definitions. As it turns out, awe—like other emotions, and also like art—is something that cannot be faithfully described to one who has not experienced it. There is no expression, no description, no metaphor, no illustration, or any other means by which one person can fully communicate to another what it feels like to be awed, awestruck, or awe-inspired. To truly know the experience of awe, one must experience awe. But although the experience of awe cannot be accurately described, it can be explained.

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines awe as, “an emotion variously combining dread, veneration, and wonder …” A seminal work by psychologist Robert Plutchik, referred to as “the wheel of emotions,” consists of eight basic emotions—joy, trust, fear, surprise, sadness, disgust, anger, and anticipation—in various degrees of intensity. The model also defines other emotions as combinations of these basic eight. By this model, awe is described as a combination of fear and surprise. At their most intense, fear becomes terror, and surprise becomes amazement.

One thing all definitions of awe have in common, and that may not be intuitive, is that in addition to such things as surprise, wonder, and reverence, awe also involves an overwhelming sense of something ominous—dread, fear, terror. The word awe, itself, is derived from an Old Norse term—agi—meaning “freight.”

The reason that awe involves a degree of fear is that awe ensues out of experiences that force you to construct a new way of understanding something and how you relate to it, whether you previously believed you had such an understanding (now rendered untenable by the experience) or not. If the thing that awed you also challenged some belief or conviction, it will either affirm that conviction unequivocally, or serve as definitive proof that the conviction—perhaps even the foundations upon which you constructed a world view, a philosophy, an ideology, an understanding, a framework for actions and decisions, or even a way of life—is not what you thought it to be.

By sheer overwhelming power, the experience of awe robs you of the ability to maintain any semblance of cognitive dissonance, or to resort to motivated reasoning, about the thing that awed you—whether a view, a work of art, a written account, a person, a realization, an idea, a revelation, or a discovery.

I think that Grant’s definition of awe as the experience of being exposed to something perceptually vast, is lacking. This is because not all people are similarly impressed with vastness. Awe is a sense of encountering something that overwhelms your ability to dismiss it or to divert attention away from it—an experience so powerful that you are incapable of ignoring it. It forces you to acknowledge a new presence in your life, and to concede that there is no plausible way for you to rationalize the experience within the limits of knowledge and beliefs you held up to that encounter.

The experience of awe makes possible but two intellectually honest outcomes: despair, if the experience robbed you of something dear (hence the term, awful); or reverence, if the experience opened your eyes to meaning and beauty beyond what you thought possible, expanded your perception beyond its former boundaries, perhaps even set you free from a great burden.

Do not confuse something awe-inspiring with something that is merely inspiring. Inspiration is not the same as awe. Unlike inspiration, awe is not altogether (or at all) a pleasant sensation, and not necessarily an impetus to creative action. It may lift you to heights you did not know were possible, or it may render your perception of your life up to that point as meaningless waste.

When experiencing awe, your mind is confronted with incredible new knowledge and understanding, and it needs to reconcile this new knowledge into the way you perceive the world, and yourself. To be awed is to gain a new perspective—a vantage point you did not have before—from which to measure the world and the values of things, as well as the truthfulness of prior knowledge and beliefs. You are given new data points to feed into the equations by which your mind creates perceptions and understanding. Sometimes you are even given new equations.

Plutchik’s wheel of emotions suggests that the opposite of awe (a combination of fear and surprise), is aggressiveness (which the model defines as a combination of anger and anticipation), but I think that in a practical sense the opposite of awe is, in fact, cynicism (defined by the model as a combination of disgust and anticipation). I mention above those people who may be unimpressed with vastness. These people are cynics, and the worst among them are those that are not only dismissive of awe and other emotions, but who have so trained their minds as to be incapable of feeling them beyond a certain threshold, or at all.

To clarify, being cynical on occasion is considered a trait of intelligent people, or at least of people who score high on IQ tests. But intelligence is not one thing. The intelligence measured by IQ tests is not the same as what’s known as emotional intelligence, or social intelligence, or other forms of intelligence suggested by various models. If a person is only intelligent in the sense of scoring high on an IQ test but is lacking in other forms of intelligence, that person may be considered “smart,” but still be incapable of the richness of life as experienced by those in whom various types of intelligence are better balanced. The person I refer to here as a cynic is one whose relationship to the world is entirely devoid of intense feelings.

As awe involves fear, it is understandable that people will be motivated to avoid it, but those who avoid awe knowing that its other component is amazement, either do not understand the transforming power of amazement or are unwilling to pay its price. Cynics are people who, knowingly or unknowingly, punish themselves by favoring emotional safety and ease over vulnerability, and in so doing deny themselves not only pain and grief, but also the most beautiful things that a person may experience.

The irony of cynicism is that it does not only shield one from intense suffering, but also from such things as intense joy, reverence, and love. As such, cynicism is at best a weak defense, and in some ways no defense at all. The cynic diminishes things to a point where they cease to have emotional implications, and can thus be joked about or altogether ignored, no matter how elevated or terrible they may be. It is a means of attenuating the very sensations of being alive to a point where they become benign, and the living experience is diminished and impoverished. And there is no greater fool than a smug cynic, taking comfort in shields of indifference and humor, not realizing that they are in fact the walls of a prison in which one may live but not fully experience life.

Those who experienced awe, even terrible awe, often are inspired to the point of obsession to seek it again, and again. This is because, once experienced, any life devoid of awe seems inferior to, and undesirable in comparison with, any life that does, even if wretched. This is because any life devoid of awe, knowing what it is, can at best hope to substitute wretchedness for anxiety, envy, frustration, and regret. And where one may still find meaning and moments of joy in wretchedness, these things cannot be experienced (certainly not to the same degree) in a life consumed by relentless frustration, no matter how prosperous.

A cynic may live a life as if it had no purpose. Certainly we may argue about what purpose for a life may be considered worthy, but to do so misses the obvious, which is this: the purpose of life, before anything else, is to be lived. Therefore, the more intensely one lives, the more life’s purpose is fulfilled.

May 16, 2018

Photography and Place

I seek out places where it can happen more readily, such as deserts or mountains or solitary areas, or by myself with a seashell, and while I’m there get into states of mind where I’m more open than usual. I’m waiting, I’m listening. I go to those places and get myself ready through meditation. Through being quiet and willing to wait, I can begin to see the inner man and the essence of the subject in front of me. ~Minor White

It seems to me that people who love the outdoors and spend considerable time in the wild fall somewhere between two extremes: those who go to places to do things in them, and those who go to places to be in them. I am the latter.

Among those who venture out intending to do things you will find mountain climbers and mountain bikers, river runners and trail runners, and yes—most of those who may describe themselves as avid nature or landscape photographers. In common to all is that they often define themselves, and consider themselves members of tribes, founded around an activity: I am a climber; I am a hiker; I am a photographer.

Among those who venture to places to be in these places—a minority to be sure—you will rarely find such clear-cut allegiances. Here you will find more nebulous self-characterizations: mountain bums and desert rats, artists and wanderers, and no small number of those who eschew labels altogether: I am me; I do what I love; I am a member of the community of life; I am more than I can begin (or care) to explain.

Among the do crowd, there are those seeking the thrill of “extreme” activities, and among the be crowd you will find those satisfied with the mere sensation of deep peace that, ironic for a social species, can only be accomplished in disconnect from the human world—virtual and artificial even without the aid of computers. Here, too, I am among the latter. I often wonder if the need for extreme thrill in concentrated doses is an inevitability for those who yearn for the wild but are forced by circumstances to spend the majority of their days in professional confinement, and need to pack as much as possible into short forays. I indulged in such activities on occasion. I am a mediocre and ungraceful climber, and can use a rope when walking is not an option; I can usually emerge upright from moderate river rapids in my kayak; and I can drive an off-road vehicle over challenging terrain. But I never enjoyed these things as ends in themselves, only as means to other experiences: ways to get to places worth getting to, so I can be in them.

Outdoor photographers, like other enthusiasts of wild places, naturally fall somewhere along the doing/being continuum, too. There are those who venture out primarily to pursue photographs, and who are disappointed if an excursion does not yield “keepers;” and those who wander the wild with no expectation or plan, in hope of discoveries, revelations, and meaningful experiences, and for whom a photograph, should one even present itself, is a bonus—a fortuitous expression of an experience worth remembering: something felt, and not just something seen. You probably guessed it: I am the latter.

It may seem odd for a so-called “professional” photographer to treat making photographs as a secondary (at best) priority when going about the world. Indeed, I have heard the argument that planning yields results and that “photography by walking around” is an unproductive mode of work. Alas, while perhaps a handicap to my inner photographer, to me the walking around part is considerably more important and satisfying than the photography part. And planning, I find, is perhaps the best way to deny myself the thrill of discovery—and the thrill of knowing that discovery is possible—without which my experience is greatly diminished. Indeed, without the depth of thoughts and feelings that ensue in the course of random wandering, punctuated on occasion by a surprise encounter with something unexpected, it is unlikely that I’ll be motivated to make photographs to begin with. I don’t want to make pictures of things; I want to make pictures about things—the kind of things that elevate my living experience. No experience, no pictures. At least not ones I find sufficiently satisfying to warrant carrying a camera.

Such is the danger of labels. Those who consider me only as a photographer, let alone a “professional photographer,” may find some value in my work, which I certainly appreciate, but they will not understand my reasons for making it. This is not to imply that there is anything “wrong” with such perceptions, only that they are incomplete, and in my opinion worth venturing beyond. In appreciating the works of others that I find interesting and appealing, I’m always interested to know the context in which they were created: the motivations, the thoughts, the emotions, and the sensibilities that brought these works into being. Some in the so-called “art world” may bristle at such an admission. To them, a work is to be understood on its own merits, require no explanation beyond what is integral to it—art for art’s sake. But my experience is that such formalism ultimately is a hindrance to greater appreciation.

To those still concerned with the “professional” aspect of what I do, I suggest that of the many reasons to make a creative, expressive, work, whether or not it was created by a professional should matter very little to anyone other than the tax authorities. I am a person who appreciates and does a lot of things, some to generate income and some to make my life richer and more interesting. Certainly, there’s a degree of overlap, but more important is how the two balance and feed off each other: what I do makes me a more inspired person, and being inspired makes me want to do more. And I know from experience that this cycle breaks when the two activities—those that generate income and those that enrich life—are not pursued in proper proportions or with insufficient investment of time and self.

It is the tragedy that our species, endowed with such depth of intellect and emotions, often is enslaved by our more primitive drives: competition, possession, tribalism, and so on. As a result, so many measure the worth of their physical life with an abundance of hedonic comforts, and live their emotional life vicariously through the experiences of (sometimes fictional) others. In realizing such things, some further handicap their living experience by extinguishing emotions with cynicism, and accepting as given such things as anxiety, dissatisfaction, and fear of change. It is becoming tragically clear that our intellectual superiority over other life has become a sword sharper than we can be trusted to yield.

It is Tuesday morning and these words come into my mind as I gaze into a canyon of astounding scale and beauty. I occupy a vantage point that no human has likely had in decades, perhaps centuries. The air is heavy with the sweetness of flowering cliffrose and mahonia; the silence interrupted by the occasional chirping of birds and the whispers of desert breeze among the pinyon pines. Such thoughts rarely occurred to me on other Tuesday mornings, en route to some office or store, attending to the challenges and frustrations of traffic and people trying to go about their day, set against the audible background of an ever-present disjointed cacophony, and the distinctive smells of a human city. Despite engaging the senses, such experiences to me always felt like sensory deprivation when juxtaposed against the magnitude of feelings experienced in the silence and peace of humanless places—the places where I feel I belong—more so than anywhere else—and that I occasionally photograph.

March 18, 2018

Casualties of Progress

The following article is based on one originally published in On Landscape Magazine. It is my hope that readers who appreciate high-quality content, hand-picked by photography-savvy editors, and free of advertising, consider subscribing to independent, subscriber-supported publications of this kind.

Unfortunately what we call progress is nothing but the invasion of bipeds who do not rest until they have transformed everything into hideous quays with gas lamps—and, what is still worse, with electric illumination. What times we live in! ~Paul Cézanne

It seems odd that, at a time when photography is more popular and more widely practiced than ever, and on the heels of some of the greatest advances in photographic technology, some adamantly proclaim that photography is dead. More bizarre is that fact that we continue to see such baiting headlines despite the fact that similar proclamations were made many times in the past, often in times of marked increases in the popularity and ease of making photographs, and proven false time and again.

Clearly, in the minds of some, photography has lost some of its luster for a variety reasons—whether it is the ease and abundance of phone cameras or the proliferation of selfie-sticks; or because someone paid an egregious amount of money for a picture of a potato; or because someone tried to hype a common image of an oft-photographed view as an original masterpiece of fine art. To those perturbed by such things I suggest considering a simple question, which is this: why should these have any bearing on the way that you practice photography?

Sometimes, as the saying goes, the more things change the more they stay the same. In 1899, around the time when Kodak began mass-producing inexpensive and easy-to-use cameras, Alfred Stieglitz—the preeminent American photographer of his day—noticed a similar trend. He wrote, “the placing in the hands of the general public a means of making pictures with but little labor and requiring less knowledge has of necessity been followed by the production of millions of photographs. It is due to this fatal facility that photography as a picture-making medium has fallen into disrepute in so many quarters.”

But Stieglitz was a visionary who dedicated much of his life to the promotion of photography as an art form. He followed with this statement, which is as relevant today as it was when written almost 120 years ago: “Nothing could be farther from the truth than this, and in the photographic world to‐day there are recognized but three classes of photographers—the ignorant, the purely technical, and the artistic. To the pursuit, the first bring nothing but what is not desirable; the second, a purely technical education obtained after years of study; and the third bring the feeling and inspiration of the artist, to which is added afterward the purely technical knowledge. This class devote the best part of their lives to the work, and it is only after an intimate acquaintance with them and their productions that the casual observer comes to realize the fact that the ability to make a truly artistic photograph is not acquired offhand, but is the result of an artistic instinct coupled with years of labor.”