Guy Tal's Blog, page 3

May 22, 2024

On Aesthetic Experiences

Note: My upcoming book, Be Extraordinary, is now available to pre-order!

Our ability to perceive quality in nature begins, as in art, with the pretty. It expands through successive stages of the beautiful to values as yet uncaptured by language.

—Aldo Leopold

Art and nature have this in common: they affect some people more profoundly than others. Upon encountering the same objects or events, some people may experience such elevated states as awe, reverence, flow, creative inspiration. Other people in the same circumstances, if they are not entirely oblivious to them, may respond to such encounters with little more than momentary reflexive acknowledgment, perhaps taking a snapshot by a Pavlovian possessive instinct, before moving on to other preoccupations, never experiencing more powerful, memorable, and transformative emotions. This commonality between experiences of art and experiences of nature is not surprising. Our intuitive perceptions of artistic objects and natural phenomena can both be considered aesthetic experiences.

Some thinkers considered aesthetic experience strictly as emotions inspired by beauty, but the diversity of opinions on this matter among philosophers and scholars suggests a broader definition: an aesthetic experience is the sum of emotions arising from sensory perceptions upon encountering something significant in the world—something beyond the ordinary. Such perceptions, in turn, may arise either from physical stimulation of our sensory organs or from mental (imagined) representations of such sensations.

Why are some people more responsive to aesthetic experiences than others? What makes the difference? Attitude does—more precisely, a predisposition to considering artworks and feats of nature as triggers and catalysts for intense emotional engagement, rather than as mere objects or events—as artifacts, anecdotes, chance occurrences. People predisposed to aesthetic experiences consider artworks and natural phenomena as things to be felt, not just recognized; assimilated, not just witnessed; actively contemplated, not just passively recognized; delineated from the stream of life, not contiguous with other—mundane, ordinary, tedious—things and events.

Those who reap the greatest inner rewards from art and nature—rewards such as awe, flow, reverence, inspiration, joy, creative energy—are those who intuitively savor—actively, consciously, deliberately—their encounters with art and natural phenomena, rather than as mere recognition (or even appreciation) of objects to be acknowledged passively among other distractions.

While these rewards are available to all, accomplishing them demands different degrees of effort from different people. Some are fortunate to have evolved a reverent attitude toward art and nature early in life. As adults, their minds are already trained to respond to aesthetic experiences naturally and intuitively. Others, who may have grown up without explicit prompting to, instruction in, or opportunities for reverent savoring of aesthetic experiences, still may—if they wish—train themselves by deliberate study and repeated exercise to become open and receptive to these experiences: to evolve consciously a natural instinct to stop, become conscious of and captivated by uncommon aesthetic phenomena as they presents themselves, direct attention and cognitive resources to experiencing them in all their richness and nuance without distraction, think about them, relate them to knowledge, memories, and emotions.

Alas, the distraction-rich world we live in makes such conscious practice more difficult today than it used to be, requiring greater discipline and discomfort to train one’s mind to a point where prolonged, reverent responses to art and nature arise intuitively and effortlessly. Still, it is not impossible, and has the potential to elevate and enrich life in profoundly enjoyable and meaningful ways.

I speak from experience. Art did not play a big role in my early life. But nature did. Only as an adult, I came recognize that nature and art could both give rise to profound aesthetic experiences—some overlapping, some unique to each. When I discovered that I may experience similar emotions and states of mind by beholding and contemplating artworks, music, and great writing—even if abstract and stylized as to be wholly separate from things in reality—as I did when encountering impressive, fascinating, inspiring feats of nature, my love of art took on the characteristics of my love of nature: it became an obsessive pursuit to learn more, to experience more, to understand more, to discover more, to feel more strongly about, to immerse myself in—repeatedly, and in disconnect from other aspects of life.

Regrettably, some go about seeking the inner rewards of art and nature in the wrong way. Rather than work on shaping their own attitudes and capacities for prolonged emotional, contemplative, engagement with aesthetic experiences—by constant learning and repeated exercise—they instead believe wrongly that they can shortcut their way to such states if they mimic the works and words of others. Arthur Schopenhauer described the folly of such thinking. He wrote:

The world in which a man lives shapes itself chiefly by the way in which he looks at it, and so it proves different to different men; to one it is barren, dull, and superficial; to another rich, interesting, and full of meaning. On hearing of the interesting events which have happened in the course of a man’s experience, many people will wish that similar things had happened in their lives too, completely forgetting that they should be envious rather of the mental aptitude which lent those events the significance they possess when he describes them; to a man of genius they were interesting adventures; but to the dull perceptions of an ordinary individual they would have been stale, everyday occurrences.

To my fellow naturalists, artists, photographers, writers, I recommend taking this as one of the greatest bits of advice I have to offer: don’t envy other people’s things, travels, products, or successes. Instead, seek people whose work and experiences seem to you most authentic and elevated, and envy their attitude, not their productions. Strive to feel like they do, to engage with the world as they do, to shape your own mind to yield you the same inner rewards as they experience, whatever your circumstances, medium, style, or product may be.

April 15, 2024

Something Is Different Today

Some of you likely noticed I failed to publish my regular monthly post in March. Between concentrated work to finish the manuscript of my upcoming book and certain unforeseen personal challenges, I found myself with a bad case of writer’s block. As (dubious?) compensation, I give you today more than twice my usual article word count.

Alas, as some of the causes of my block remain unresolved and as my next projects are still taking shape, I decided to reach for my usual block-breaking technique: switch from essay form to stream-of-consciousness form. I hope you find my belabored train (wreck?) of thought below at least somewhat interesting.

But first, a couple of (unsolicited) credits and recommendations:

After several years of intensive writing, my friend Colleen Miniuk recently announced the upcoming publication of her turbulent memoir, So Said The River , in which I happen to be a character.I recommend taking some time to read through the recent writings of Alberto Rodriguez-Garcia. I’ve had the pleasure of meeting Alberto on a photography workshop and was delighted to discover he is also an excellent writer. I found his posts thoughtful and honest, and relevant to anyone seeking meaning in photography (and in other pursuits).My thanks to my generous friend Jack Graham, who knows more about music than I ever will, for prompting my renewed interest in the works of composer Gustav Mahler, who I mention below.Until next time!

—Guy

~~~

But I smile, and not only with my mouth. I smile with my soul, with my eyes, with my whole skin, and I offer these countrysides, whose fragrances drift up to me, different senses than those I had before, more delicate, more silent, more finely honed, better practiced, and more grateful. Everything belongs to me more than ever before, it speaks to me more richly and with hundreds of nuances. My yearning no longer paints dreamy colors across the veiled distances, my eyes are satisfied with what exists, because they have learned to see. The world has become lovelier than before.

—Hermann Hesse

Something is different today. Spring has arrived. By this I don’t just mean that the calendar has advanced past the vernal equinox, or that temperatures have remained consistently above freezing for a few days in a row, or that the desert is greening up and starting to bloom. What I mean is that it finally feels like spring. Every cell in my body feels quickened and awakened in synchrony with the emerging life in the desert around me.

How odd that such a familiar and predictable feeling, experienced so many times in so many places for so many years in so many lives I have lived, still catches me by surprise each time it happens. Unlike so many other experiences, repetition does not seem to diminish this feeling, the richness and intensity of it, the novelty of it, the exaltedness of it.

After spending the last few days exploring, my body pleasantly sore from the long hikes, I’ve decided to rest and putter around my camp today. I have been alone in the desert for nearly a week now, mindful of the phenomena of the season unfolding around me—the subtle changes in light, temperature, colors, sounds, and scents. Some plants are already in bloom, birds are chattering all around me, lizards pause occasionally from their busy scurrying to stare at me. As I settled in my camp chair with my morning coffee, in the quiet blue hour before dawn, not quite fully awake, I sensed something feels different today. Something important, I can tell. Although I can’t say I what it is yet. For now, I will savor it.

This much I do know: something has come to an end. Something is starting. Imaginary pensive music is playing quietly in my mind. Every sense is heightened. Every smell, every sound, every view means something beyond what it seems, beyond what it felt like yesterday. Each nuanced difference hints of a grand secret about to be revealed. It’s not a good or a bad feeling but it is far from benign, rife with anticipation, trepidation, excitement, curiosity. The plot is about to twist. The protagonist is always the last to know.

~~~

Reflecting on his career after several decades during which he established himself as one of the greatest photographers in history, Edward Steichen confessed, “When I first became interested in photography, I thought it was the whole cheese. My idea was to have it recognized as one of the fine arts. Today I don’t give a hoot in hell about it. The mission of photography is to explain man to man and each man to himself. And that is no mean function.”

When I first read Steichen’s words, perhaps two decades ago, I thought I understood what he meant to say. I didn’t quite agree with the idea that photography has any “mission.” Photography can serve so many purposes, practiced in so many ways, express so many things. Why would it need a mission? Why not many missions? Why would photography be expected to explain anything? Photography to me seemed as a means of expressing things I already knew and felt—things already obvious and visceral to me, needing no explanation.

In hindsight today I think I finally see that photography has in fact explained and clarified some things to me, about me. Steichen was right. Likewise, years ago, it would have seemed anathema to me to agree that photography is not “the whole cheese,” but now I, too, no longer “give a hoot in hell” about photography’s recognition as a fine art in any abstract, universal sense. I recognize my own work as art. I have shared in many writings what I mean by it. I strive to examine and to refine my views constantly as I gain new knowledge and experiences. Let others make up their own minds.

I have hinted in recent writings of changes, realizations, urges, epiphanies, questions, changing circumstance that are pointing me toward exploring new directions in the coming years. Doing “more of the same” when my work no longer feels novel and exciting has never appealed to me. “Boredom,” wrote Søren Kierkegaard, “is a root of all evil.” I agree. Boredom is wasted living.

Mary Oliver wrote, “The most regretful people on earth are those who felt the call to creative work, who felt their own creative power restive and uprising, and gave to it neither power nor time.” I can say with pride I do not belong in this regretful demographic. Several times before, when the sirens called, I have left home and country, lucrative careers, comfort, security, and formerly held beliefs, to heed the call. All involved struggle and anxiety. All have proven in hindsight to have been among the best decisions I’ve ever made. “Anxiety,” wrote Kierkegaard, “is the dizziness of freedom.” Freedom is about choices. The greater and more consequential the choice, the greater the anxiety: the cost of freedom. I will pay it. I always have. It was always worthwhile.

After recently submitting to the publisher the complete manuscript of my next book, Be Extraordinary: Philosophical Advice for Photographic (and Other) Artists, I decided to take some time to disconnect and to contemplate, to let my mind drift and see where it may want go when set free from obligations and expectations. It drifted to thoughts about beauty, inspired by music.

~~~

Philosopher Roger Scruton opened his book, Beauty: A Very Short Introduction [ad], with these words: “Beauty can be consoling, disturbing, sacred, profane; it can be exhilarating, appealing, inspiring, chilling. It can affect us in an unlimited variety of ways. Yet it is never viewed with indifference: beauty demands to be noticed; it speaks to us directly like the voice of an intimate friend.” Later in the book, he wrote: “Our need for beauty is not something that we could lack and still be fulfilled as people. It is a need arising from our metaphysical condition, as free individuals, seeking our place in a shared and public world. We can wander through this world, alienated, resentful, full of suspicion and distrust. Or we can find our home here, coming to rest in harmony with others and with ourselves. The experience of beauty guides us along this second path: it tells us that we are at home in the world, that the world is already ordered in our perceptions as a place fit for the lives of beings like us.”

Would it surprise you to know that beauty, which every one of us understands intuitively, cannot be defined in absolute, objective, measurable terms? Beauty is a matter of subjective perception and preferences. No doubt, some of these perceptions and preferences are shared by many people, but there are no criteria and no measurable qualities to distinguish unequivocally something as beautiful. Beauty is a quality our minds intuitively associate, based on a variety of subjective factors, with things in the world—not just with aesthetic things like works of fine art, certain colors, or designs, but also with faces, personalities, emotions, ethics, relationships, deeds, sensory perceptions, knowledge, mystical beliefs, ideas, even mathematical expressions.

It struck me recently that my passions in life—my keen interests in art, philosophy, science, and in certain experiences—are in fact not random or eclectic. They have a common denominator: the desire to experience as much beauty, in as many forms, and as intensely as my brain would allow. This is the desire that drives me to seek awe before sublime landscapes, behold great art, create photographs and poems, immerse myself in music, contemplate the implications of various interpretations of quantum mechanics or of certain mathematical theorems.

What does that have to do with photography or art or my creative aspirations in the years ahead? Everything. With this clarity about my overarching desire to induce and to experience profound beauty—as much, as often, and as powerfully as I can—several trains of thought suddenly and unexpectedly arrived at the same destination… while standing on a small desert peak, listening to the music of Gustav Mahler.

~~~

I left my camp early in the morning with the general intent of hiking around, up, and over the lower slopes of a small range of desert mountains, to see… well, whatever there was to see there. I didn’t know what path I would take, how long it would take, what plants or animals I might encounter, what geological or archaeological treasures I might discover. (I rarely do when I go hiking.) But one thing I did know—the music that will accompany me on at least part of this walk: Mahler’s symphony no. 2, known as “Resurrection.”

I was going to listen to the whole thing, but I especially anticipated listening to the 5th and final movement, which is to say I knew the emotional freight train I set in motion by my choice. Mahler composed the symphony such that its earlier movements gradually prepare listeners, creating for them a world of beauty, gentleness, drama, ups and downs, slowly detaching them from their everyday preoccupations and immersing them in transcendent music (in fact, music continuing the story he began with his first symphony, which ended with the death of a hero) before unleashing the powerful final movement. He jokingly told a friend once that if people knew in advance what’s coming, they might be worried for their eardrums.

Not to belabor the day’s experiences, having already taken up so much of your time, and knowing there’s nothing I can write that could compete with the music, amplified still further by the beauty of the desert, I’ll share a journal note I wrote upon arriving at the summit of a steep hill in the early afternoon, sore and exhausted after several hours of walking and a strenuous scramble, breathing the fragrant early spring air, beholding a vast view of the colorful desert with ominous clouds above and the drama of a small storm beginning to brew:

The music touches on everything: life’s adventures, struggles, gentleness, victories, defeats, tragedies, doubts, reprisals, and, finally, the agonizing and seemingly final triumph of death. But death is not the end. When the struggle ends in defeat and all is reduced to near silence, there still remains the calm, quiet, peaceful, beautiful music of eternity. In eternity death is not final. Everything returns. The story continues. [The philosophically minded may recognize here the influence of Friedrich Nietzsche’s much-misunderstood idea of “eternal recurrence.”]

So, what comes after death? Well, it’s called “the resurrection” for a reason. That’s what comes next. Remember Bob Dylan’s cutesy track, “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door”? Not Mahler. Mahler doesn’t knock. With an army of hundreds of instruments, vocalists, and musicians admonished to give it everything they’ve got, he is going to blast open the gates of heaven for all existence to come pouring back out. And does he ever!

The final notes are overwhelming. The singers are belting out: “Sterben werd’ ich, um zu leben! (I shall die in order to live!)” And then it’s over… and I’m left with the silence of the desert and the growing roar of the wind. Good f’n grief! I can feel my heart pounding, and not just from the physical exertion. I’m tearing up and vaguely conscious that my lips are whispering expletives I never intended to utter out loud.

Then, the question bubbled up in my mind: can I hope to express or to elicit an experience such as I just had in photographs? The humbling answer seemed absurdly obvious. If I could snap my fingers and instantly replace my skills as a photographer for equivalent skills as a musical composer, would I do it? This answer, too, now seems obvious: absolutely. Except that this was not always the case. A couple of decades ago, my answer would have been “absolutely not.”

What changed? Most obviously, I have. It may be an uncomfortable truth to some, but if one aspires to be a self-expressive artist (which I do)—to have one’s art express authentic thoughts, feelings, knowledge, personal philosophy evolved in the course of one’s life—then it stands to reason that as life changes, the art that expresses it must change, too. When an artist’s work remains consistent for any significant period, one of two things must be true: either the artist has ceased to be expressive (i.e., has gotten too comfortable with tried-and-true habits), or the artist has not evolved as a person during this time. The latter case is, as far as I can tell, theoretical. It is the mark of a self-expressive artist to not be consistent, to have distinctive “periods,” even to change course completely. As Aldous Huxley put it, “The only completely consistent people are the dead.”

So, how have I changed? In some ways, I have changed in response to the trials of life. I have always been restless and resistant to long-term planning, which is another way of saying that consistency as an aspect of lifestyle has never appealed to me. Just as important, I have always actively sought to examine and refine my personal philosophy, among other things by studying the writings of great thinkers. This can be a dangerous endeavor. If you go about it too obsessively, inevitably, every so often, you’ll learn of a better way to think about something important than the way you previously thought was correct. As Albert Camus put it, “a man is always a prey to his truths. Once he has admitted them, he cannot free himself from them.”

Wait, where was I? Oh yes, music. Oh, and now also philosophy.

~~~

Arthur Schopenhauer considered music as an embodiment of “things in themselves.” When music expresses beauty or sadness or exultation or any other feeling, it doesn’t refer to these qualities in relation to any one object or experience; it describes the very essence of beauty, sadness, exultation, regardless of where they may be found. Schopenhauer wrote, “That music acts directly upon the will, i.e., the feelings, passions, and emotions of the hearer, so that it quickly raises them or changes them, may be explained from the fact that, unlike all the other arts, it does not express the Ideas, or grades of the objectification of the will, but directly the will itself.”

[“The will” is Schopenhauer’s term for the force of endless, purposeless, constant striving that underlies all natural processes. Likewise, “Idea” is Schopenhauer’s term for reality as it presents itself to our minds and subjective perceptions. This, in turn, is a refinement of ideas originally expressed by his predecessor, Immanuel Kant, who distinguished between “noumena” (the true nature of reality, which is beyond our ability to know directly), and “phenomena” (reality as we perceive it, filtered through our human minds and senses).]

The effects of art—especially music—as Schopenhauer explained them relate to a key concept in the aesthetic philosophy of Kant. Kant claimed that to experience the highest form of beauty we are capable of, we must approach art with an attitude of “disinterestedness.” What he meant by that is that when we behold art, we must avoid considering any connection between the art and reality, and instead approach art purely as an aesthetic experience. That is, we must never think of visual art as “pictures of things in reality,” or of creative writings as “descriptions of events that occurred in reality,” and so on. Music holds a privileged position among the arts in the sense that it is purely expressed in form, without material contents, and therefore is completely detached from any specific object or event.

In Kant’s words: “The delight which we connect with the representation of the real existence, of an object is called interest . . . Now, where the question is whether something is beautiful, we do not want to know, whether we, or anyone else, are, or even could be, concerned in the real existence of the thing, but rather what estimate we form of it on mere contemplation.”

And what is photography (at least by design) if not the most “interested” artform there is? In terms of “interestedness,” we may even say that photography, which relies directly on objects in reality, is the polar opposite of music. This, in essence, is why photography can never “aspire to the condition of music” (an expression coined by famed art critic Walter Pater) as other arts do. It is why I believe no photograph can ever elicit the same emotional effects as music. (Admittedly, I am tempted to consider how, and why certain trained musicians, such as Ansel Adams, made the curious choice to switch from music to photography. But, seeing as I have already written 3,000 words, I will spare you… at least for now.)

~~~

With these realizations, a piece of the puzzle—what is different—fell into place for me. I have experienced what Pater described as, “the condition of music” in many forms: in music (of course), in poetry, in great writing, in cinema, in masterful paintings, in philosophical contemplation, in scientific knowledge, even in contemplating some mathematical works. In photography, I confess, I only experience this effect when revisiting some of my own most satisfying works, when they remind me of the intense emotional experiences of their making. Likely, this is one reason I find myself now considering other forms of artistic expression.

Something is different today. I think I’m starting to understand what it is. I will savor it.

March 7, 2019

I Already Won

When vision is marketed to win / there’s nothing in victory to desire. ~Wendell Berry

I have never entered my photographs into a contest. If I had to offer a formal reason, it would be this: competition introduces motivations and temptations that in my mind are incompatible with creative self-expression. Informally, I really don’t care what some random judge(s) may think about my work, and I don’t think there is anything for me to gain from having my work ranked against others’ by someone’s subjective opinion. Having accomplished sufficient knowledge and skill in operating my equipment and processing my images, I have no need to “measure up” or suggestions for “improvement.” Whatever inspiration I find in the works of others, doesn’t make me want to compete with them or to be like them.

Among other unfortunate effects of our achievement-driven attitude is that many are under the mistaken impression that competition and “winning” are essential to success and satisfaction. Studies show that this is not the case. Human beings are prone to hedonic adaptation—returning to our emotional baseline soon after a desired achievement has been accomplishment. A truly rewarding life is not one of anecdotal honors bestowed by others, but one of sustained interest and satisfaction, regardless of the judgment of others.

Another unfortunate effect of our brave new hyper-connected society is what’s now termed, fear of missing out (FOMO)—a form of (largely self-inflicted) anxiety that occurs when one is disconnected from others and fears that important and consequential things may happen without their knowing or participation. Rarely mentioned is the flip-side of such anxiety: the sense that a rewarding experience is not worth having if others don’t know you’ve had it. It’s no wonder that studies show a persistent decline in creativity in recent years.

Should you realize that you are prone to such feelings, resist them with all you have. If you hang the value of your experiences on the opinions of others; if you feel your life is so devoid of meaning in its own right that you must find meaning in what others are doing; or if you feel your living experience may be diminished if you miss something other people do, you will never—NEVER—be satisfied. If you’re afraid of missing out on things other people might do, you should be outright terrified of missing out on things you might be doing.

The most rewarding experiences in my life occur when others are not present to witness them, or even know that they happened. I don’t need awards or recognitions, and have no need or desire to compete with anyone. Why would I need to compete? I get to do what I love, to live and work and explore in a place I love, to be inspired often and without regard to who knows it, to enrich my knowledge and understanding of the world and of myself, to set my own schedule, to follow my whims almost any day.

Give the trophies to the less fortunate. I already won.

February 17, 2019

Washington / The art of the Landscape by Bruce Heinemann

Disclaimer: my friend, Bruce Heinemann, sent me a copy of his new book, which I feel is well worth recommending. I have absolutely no financial interest in the book.

***

Photography, among all of its noble characteristics is perhaps first, and foremost about relationships… between ideas, themes, colors, shapes, textures, metaphors. ~Bruce Heinemann

Although neither of us knew it at the time, Bruce and I found each other at a critical point for me, and was instrumental in my decision to become a full-time photographer and writer. Years ago, when I still had a corporate job, I had to attend some business-related training. As you can imagine, it was hardly an inspirational experience, at least until my first break, when I entered the break area at the training facility. There, on a small table, were a few tattered coffee-table books and magazines for use by anyone who needed respite from whatever class they were attending. Among these books, was Bruce’s book, The Art of Nature. I spent the rest of the training session waiting eagerly for breaks, when I could head for the break room and page through it.

The images in Bruce’s book touched me profoundly, for a reason I will explain in a bit. While still working through the training class, I decided to contact him to express my gratitude. If I recall, the subject of that email was something along the lines of, “inspiration in unlikely places.” To my delight, Bruce not only responded, but was gracious and friendly, and I was impressed by his kind and gentle manner, and by his obvious love for photography and for his home state of Washington, where the majority of his work was created. And so, we began a correspondence that lasted ever since, and I can say that just about every exchange I have ever had with Bruce left me feeling cheered and inspired by his calm and thoughtful manner. Not just a maker of beautiful photographs, Bruce is also a beautiful soul.

The reason I found Bruce’s work so compelling is that it radiated a sense of peace, no matter the subject or lighting conditions. I was accustomed to other kinds of coffee-table books, rich in impressive eye-popping scenics. I have rarely seen such collections of quiet and thoughtful work as I have in Bruce’s books—exactly what I needed at a time when life’s challenges were bearing down. What I found even more impressive, is Bruce’s ability to produce such quiet and engaging work in any light—from sunny days with clear blue skies, to complex patterns in trees and vegetation on overcast days or in the depths of the coastal rainforest.

Bruce’s new book: Washington / The art of the Landscape continues the same theme, this time with writings and musings by Bruce, himself. As you flip through the first pages, you will find those sunny-day scenes that are easily relatable to anyone and inspire a sense of inner joy. Then, as you flip through page after page, if you are a photographer of some experience, you will be impressed by Bruce’s ability to distill the proverbial “order out of chaos,” in complex and very satisfying intimate compositions.

Not to belabor my praise, I’ll let Bruce’s work speak for itself (see gallery at the bottom of this page). This is a hardcover coffee-table in the tradition of the old Sierra Club format, each photograph, presented with dignity, with wide margins, making it easy to contemplate and appreciate. A worthy addition to any collector of fine photography books.

(Click the book cover above to be redirected to Bruce’s website)

(Click the book cover above to be redirected to Bruce’s website)

Samples from the book:

February 12, 2019

The Meaningless Moment

As some readers may know, I am working on my next book manuscript, which is part of the reason I’ve been quieter than usual. The following is an essay from the current manuscript. It is adapted from an article I originally wrote for LensWork Magazine under the title, “The Insignificant Moment.”

***

The world we live in is a succession of fleeting moments, any one of which might say something significant.

~Alfred Eisenstaedt

Henri Cartier-Bresson described his approach to photography as, “the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event.” For Cartier-Bresson, the photograph serves as testimony to some “decisive moment”—a fleeting event recognized by the photographer as significant (by whatever criteria), and then plucked out of the stream of time to assume a fixed, timeless, existence. Susan Sontag expressed a similar sentiment, writing, “The force of a photograph is that it keeps open to scrutiny instants which the normal flow of time immediately replaces,” which, among other things, led her to conclude that, “To take a picture is to have an interest in things as they are, in the status quo remaining unchanged.”

In reading such accounts, it stood out to me that the characterization of photography solely as a means of commemorating and preserving visual snippets of ephemeral events is remarkably shortsighted and prejudiced. Such a view of photography ignores (or is ignorant of) the fact that non-representational photography has been common and widely accepted for prolonged periods (e.g., the decades in which Pictorialism thrived). Such a view also fails to recognize that photographs, other than just being taken from reality, can also be created such that they enlarge or transcend reality. Put simply, a photograph may be a record of some fact in reality (I’ll sidestep, for the sake of this discussion, the philosophical challenges involved in defining the term); it can also be something nonexistent in present reality until created, at which point the photograph itself becomes a fact in reality.

Photographers, even those adhering to some idea of purity of process, don’t need to limit their expressive powers to views already in existence; they also have the power to bring new views into existence. And, they can even do so by means accepted as being purely photographic.

The characterization of photography as a means of fixing literal appearances at a point in time also implies that photographers can only be reactive, rather than proactive, in their work. But, of course, we know that the photographic medium offers a wide range of means to (paraphrasing Ansel Adams) depart from reality. I propose that even if just one such non-representational photograph exists, it is sufficient to declare that photographs should never be assumed to be representations of reality, unless explicitly presented as such. And I think it would not be an exaggeration to say that millions, if not billions, such photographs already exist, and that every one of us living in the industrial world likely sees at least one, and likely more, of these, every day.

Ansel Adams’s epiphany about visualizing photographs before making an exposure speaks directly to photography’s ability to depart from realistic representation. Implied in the definition of visualization—which is: seeing in the mind’s eye a finished image before making an exposure—is the fact that a visualized image has to be different from a view as-seen (otherwise, why would we need to visualize anything in the mind’s eye?). Visualization is not about seeing what is; it’s about imagining what can be—not just how things might look like to a random observer, but how things can be composed and processed to accomplish an expressive goal of the photographer’s conception.

In limiting photography to decisive moments, photographers become not only dependent on, but slaves to, circumstances: they are expected to wander the world, prepared to reach for the camera in the event that some fleeting significance outside themselves, which by random chance is also pre-expressed in some pre-arranged composition, presents itself. I don’t think even Cartier-Bresson could have characterized his earlier approach as such. The qualification of “earlier” is important, since he later changed his mind—in his later years, he became a painter, and in his words, “photography has never been more than a way into painting, a sort of instant drawing.”

If nothing else, things that can be recognized as significant in a fraction of a second must be simple enough to make such instant recognition possible. The more complex the significance, the longer it takes to recognize it and to consider compositions and processing decisions aimed at expressing it.

Perhaps lost in the discussion so far is the fact that significance is not a fixed quantity, and can be assigned consciously to anything. Why should a creative photographer not be free, as any creative artist is, to assign significance to any moment, for any reason? And who’s to say that significance only comes in moments? Should a photographer just give up on any significance that is not instantaneously recognized, or that persists independent of any decisive moment?

I am a contemplative photographer, in the sense that I consider consciously whatever significance I wish to express in a photograph until I am able to articulate this significance, if only to myself. Other than the initial recognition that a significant photograph may be possible, and some aspects of the mechanics of the photographic medium, nothing in my process happens in a fraction of a second. Once I recognize the opportunity to make a photograph, all the steps that follow are considered consciously, however long it takes. Perhaps this approach makes me miss some opportunities, but so what? I’m in it not just for the photograph, but also—more so—for the experience. Just as important, it also stands to reason that those who only photograph in response to fleeting events, never taking the time to explore a subject intently beyond first impressions, likely miss much more than I do.

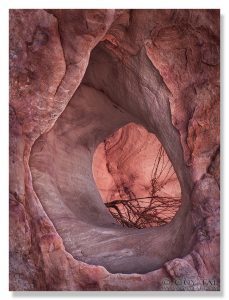

When I capture a photograph, it’s not because some serendipitous decisive event presented itself. Rather, it is the random moment when I feel prepared, having spent what time I needed to contemplate whatever called out—sometimes just whispered—to me. The camera doesn’t come into play until I’ve considered what I wish to express; until I’ve studied the scene to my satisfaction and determined the most effective composition, perhaps even returned to the scene several times to examine it at different times of the day (or the year) and under different light and weather conditions. I’m not prepared to capture anything until after I allow myself the time I need to form a clear visualized outcome in my mind (which I may later change), and after I’ve taken whatever time needed to tinker with my camera’s controls. There is nothing special, let alone decisive or significant, about the moment I trip the shutter.

Less obvious, but to me more important than whether a moment is decisive, significant, or just the random time when my preparations are complete, is the difference in attitude between recognizing something “in a fraction of a second,” versus taking whatever time I need to construct a photograph, first in the mind, then in the camera, and later in processing. The former implies the attitude of a hunter-gatherer, always on the lookout, ready to pounce. The latter is a meditative approach—an approach more conducive to mindfulness and flow—a progression of experience that amplifies and builds over time like a musical crescendo. To me, this approach culminates not only in “good” photographs, but also in richer and more memorable experiences that are considerably more rewarding to me than just making a “good” photograph.

January 2, 2019

The Element of Surprise

Nothing in the world is more exciting than a moment of sudden discovery or invention, and many more people are capable of experiencing such moments than is sometimes thought. ~Bertrand Russell

I’m delighted to see various “influencers” promoting the idea of not revealing location information. Recently, even a local tourism board (in Jackson Hole, WY) decided to create a campaign asking photographers to refrain from tagging locations. It’s a viewpoint I’ve been promoting for many years, and that at times elicited some heated responses. I don’t wish to rehash the same arguments again, but I do wish to point out the irrationality of one of the more commonly-mentioned counterpoints. Upon discovering some places, I had them to myself, not just to photograph but to experience and to be in. Some believe that my reluctance to make their location public is selfish. I suspect that those who hold such opinions may never have experienced the thrill of discovery; or if they did, they failed to consider it in their argument.

The experience of arriving at a known scenic location, and the experience of discovering such a location unexpectedly, are worlds apart. One would have to be emotionally numb to consider them as even similar, let alone interchangeable.

By not publicizing such locations, I am making it possible for others to also discover them as I did, to experience the same thrill as I have when first encountering them, to have these places to themselves as I have, to find them as pristine and as wild as I have. If I was to make such a place public and popular, none of these things will ever again be possible, for anyone. It is also likely that such popularity may have a detrimental effect to the ecosystems existing in such places. Which is the more selfish position?

There is no shortage of known locations where capturing spectacular, if uncreative, photographs is almost guaranteed. The same can’t be said about locations that are still wild and unknown.

I am fortunate to have had the experience of discovering several such places; and the memories of sudden awe when coming upon them are imprinted in my mind as vividly as those of my most cherished times. I may not know whether anyone before me has experienced the same surprise and amazement in the same places; but if someone has, I am grateful to that that person for leaving them as found—and as anonymous. I hope that if ever there is a next person to discover these places without expectation, that person will be similarly grateful for not knowing about them in advance.

You cannot plan an adventure any more than you can plan a surprise party for yourself. Adventure is the result of encountering something exciting and unexpected (and not always in good ways)—of discovering something new about the world, or about yourself, or about both.

Don’t spoil the surprise.

December 23, 2018

Twenty Eighteen

Vastness! and Age! and Memories of Eld!

Silence! and Desolation! and dim Night!

I feel ye now – I feel ye in your strength.

~Edgar Allan Poe

I was about to start this post saying that 2018 had been a year of formidable challenges and deep reflection, when I realized that these describe just as well every one of my years to date. The common denominator is obvious. The difference, as always, is not so much the what as it is the why and how. And these, I confess, I struggle to explain even as I write these words. But I’ll try.

This is so far the fourth iteration of this post, and the only one that trusted friends did not suggest I refrain from making public. I may explain the reasons at some later time, if and when I feel more confident in my desire and ability to do so. Alas, it is my nature to find comfort in the fact that the great majority of my life unfolds away from public view. Also, I am of a generation (perhaps the last) that still values privacy. So, without going into detail, I will mention that in the past few years I’ve been struggling with an illness whose implications I am still learning and coming to terms with. Among other things, it has affected my productivity and my ability to work on a couple of projects (primarily books) I had hoped to finish this year, and that will be pushed into 2019.

Several people asked me when/whether I plan to publish another essay book. Rest assured, a manuscript is already written. There is still a fair amount of editing and design work remaining, but the text is nearly finished. I will, of course, provide updates as I have them.

Photographically, to my surprise more than anyone else’s, 2018 has so far been my most productive year. To give you a sense, I made almost twice as many images this year as I have in 2016, and just over 40% more than I have in 2017. Of course, volume is not necessarily correlated with quality, but I am cautiously optimistic that the reason I felt more motivated to photograph has to do with new treatment and medication I started around March of this year.

I find it odd to confine life events and creative evolution to the arbitrary boundaries of a calendar year, but, as I have noted before, I welcome the excuse to pause and examine the progress, trends, and implications of my experiences in the past months. I believe my work this year, perhaps as a result of dealing with some formidable setbacks, has continued to grow more intimate and expressive. I feel that I have also made progress in my studies of visual expression and in finding ways to apply new knowledge in my work.

This past year, I have also began to emphasize in my teachings such topics as creativity and self-expression. It is my sense that, as digital technology has drawn many people to photography in the past 10-15 years, and as many of these people have now reached the fabled “10,000 hours,” there is a growing interest in finding some “next level.”

I’m not sure when it happened, but it seems that I and some of my contemporaries have become sufficiently old (hopefully, also more experienced, perhaps even wiser) as to now be considered as the previous generation. I take it as both a sign of maturity, an affirmation that my path (random as it was) has been rewarding and useful, and as an indication that it is time for me to consider new priorities. Competition has never interested me much, not in business, not in art, not really in anything. With the privilege of having accumulated some knowledge and experience, I find interest in the works of some younger photographers, and I believe it is important to offer these photographers whatever support and encouragement I can.

Of course, I would be remiss to not also acknowledge my previous generation—those lions of photography who set for me and my contemporaries a truly honorable example, being paragons of outdoor ethics, conservation, promoters of photography as art, and pioneers in creating the very business I am now in. You (hopefully) know who you are. Thank you!

For what it’s worth, my generation has experienced the revolutions of the Internet and digital photography, among many others. Perhaps less obvious, but in my lifetime there has also been tremendous progress in art and science, much of which is relevant to photographers and that I believe is worth teaching. On the other hand, in my lifetime the planet has lost more than half its wildlife in what is now considered the sixth great extinction event in Earth’s history, largely attributed to the antics of my fellow hairless apes. Lest we forget or become too complacent in our intellect or beliefs, consider that extinction, arguably, is the most natural thing to happen to any species. Whether humanity persists beyond the next few decades or centuries may be a matter of some speculation, but that should not distract each of us from considering with great seriousness the unrelenting hourglass of our days and moments.

Last but not least, some of you have generously signed up as patrons of my work, using the website Patreon. I am neither wealthy enough nor vain enough to turn down financial support offered in good faith, and I am sincerely grateful. I am also grateful to all who took the time to read my books, to express thoughts about my work, and to subscribe to the publications I contribute to. Whether your support is financial or other, please accept my thanks. I hope I can continue to earn your interest.

You may browse my work from 2018, along with hundreds of previous works using the Image Stream feature on my website. Additional changes, collections, etc., are in the works.

I wish you a peaceful rest of the year, and a wonderful New Year.

Better Than Gold

Better Than Gold

November 21, 2018

Time to Exhale

What can we do but keep on breathing in and out, modest and willing, and in our places? ~Mary Oliver

It may be that the last couple of years have been the most difficult in my life. I may elaborate on the reasons in a future post, but I will say now that my recent time in the canyons was as emotional as any I have spent in this desert. After a roller coaster of a year, coming to terms with an illness, and other surprises—pleasant and otherwise—I needed the comfort of things familiar and beautiful. I needed to meander in the red glow, to be isolated from the trials of life in a world of peaceful sounds, delicate scents, and endless nuanced sensations for which no words exist. I needed to return to the world of the canyon.

Despite the ongoing drought and the poor shape of deciduous trees in the local mountains, the cottonwoods in the deep canyons put on a memorable display of autumn color, each leaf still clinging to a tree now the color of a ripe lemon. Recalling the memories of thoughts and sensation, I can almost sense the radiant light and soft breeze against my skin, like the touch of a healer—barely felt but undeniably radiating energy and comfort.

After so many years in this beautiful desert, I have become aware of even the smallest changes. If I saw nothing else, the qualities of sunlight and the delicate smells would be enough to know that it is autumn. This has been an unusually good year for rabbitbrush; water in the creeks appears clearer and more emerald in tone than it does in other seasons; the path of water has shifted a bit as rocks and stumps rearranged by the summer monsoon floods (very few of which we had this year). I feel proud to have evolved such a close relationship with this desert as to notice such things. It is this awareness, honed and refined in the course of decades, that makes these places feel so welcoming and familiar to me. But of course these places are never without mystery and secrets, never familiar enough as to not surprise on occasion with new visions and revelations. I sometimes wonder whether those photographers who hop frantically from one place to another, never staying longer than it takes to make a few photographs, ever get to feel such a connection with a place. I, too, was once enchanted with stories of travels to exotic places. I thought that to see more of the surface of the world was the way to become more enlightened about its nature. That was before I learned how much lies beneath the surface.

Good to Be Back

The turning of the leaves may be the most obvious sign of the season, but the canyons hold many secrets, some only knowable to those who spend a great amount of time with them. For example, for a period of about four weeks each autumn, patches of exposed earth above the canyon floors come alive with dense, soft, and vibrant grasses, combed into sinuous fractal patterns by meandering winds. I wonder how many people know the plush feeling of walking barefoot on these verdant mats. After the long drive on a bumpy dirt road, and the obligatory difficult entry into the canyon—part of the reason I have only twice in two decades found other people’s footprints in it, and never in its side-canyons, I walked the wash until I reached water and big trees, and made my camp in a protected alcove near a patch of these ephemeral grasses, across from a hackberry tree guarding the entrance to the alcove.

This is no ordinary alcove. Unlike the gaping openings of most sandstone alcoves, this one hides behind a rincon—an island of rock remaining after the creek abandoned its old course and carved a new one. The original channel, likely short lived as it is rather narrow, cut at the base of the sandstone cliff, creating a rounded chamber, only some twenty feet wide, its floor now covered in soft grass illuminated by a narrow beam of warm sunlight. This, too, only happens for about a month in autumn as the sun is lower and further south in the sky than it is in summer, when this alcove gets no direct sunlight at all. All this I learned some years ago, and have returned to spend a night or two in this place almost every year since. “Welcome back,” it whispered to me, “you are home now and everything is ok.”

A Beautiful Mess

I thought about remaining in place, to just rest and recuperate for a couple of days. But the call of yet greater walls and larger trees was impossible to resist. I wanted to venture further away from the morass of memories and emotions that marked the months before. And so, I spent my second day walking for nearly ten hours to the lower, deeper, more mysterious reaches of the canyon. This place is so rarely visited that it is likely that much the local wildlife has never crossed paths with a human being.

You may find places somewhat similar in appearance that are much easier to get to, but appearances are a small part of the experience of the desert. I don’t know that there is a word to describe the mix of feelings inspired by remoteness. Perhaps it is an emotion in itself, known only to few. To a recluse like me, it is one of the most comforting feelings there are: the practically certain knowledge that I am alone, removed from the mass of humanity, and that no other person is to be found within many miles. Like the difficult entry protecting the wildness of the canyon, this sense of blissful remoteness also is protected by barriers—inner ones. Finding comfort in such places is only possible after one has transcended the anxiety that afflicts most people in such places. Not me. I know of this anxiety only by hearsay. This is where I feel most at home.

Her Majesty

As I walk, I delight in the iridescent film lining the creek’s shallow edge—a phenomenon once known to few but that has now become a magnet for photographers. Good? Bad? As I like to say, there is one correct answer to almost any question—it depends. Rounding a corner, a solitary giant of a tree appears in the nave of a curve in the canyon, spreading its great limbs like arms protecting weaker and more fragile beings—shrubs and lizards and birds and me. Without thought, I whisper, “good morning, your majesty.” I remove my pack, savoring the sense of relief, and spend some time getting reacquainted with some rocks. I then devour an early lunch at the foot of the great tree, my small world bathed in vibrant warm colors and intricate detail as if lit by some red sun. My meager sandwich in this place rewarding in ways that can never be accomplished in even the most fancy of restaurants.

In a wide section of the lower canyon, walled by cliffs hundreds of feet tall, a paradise of desert life thrives, hidden among steep precipices like the mythical Shangri-La, and just as difficult to find. Enormous cottonwood trees spread their canopies above the rich tapestry of desert plants, a crystalline stream flows through fluted waterways, forming a chain of small pools nestled in basins of polished red rocks. It is inevitable that after some time spent in such a place, one is likely to at least consider not leaving, not rejoining the hives of humanity. I can think of no sense—not sight, not smell, not hearing, not touch, and not even taste—in which any city can surpass this wild and delicate paradise. A dry piece of bread tastes better here than any creation of any great chef consumed in a city. To me, that is. I must be cautious not to tempt too many to seek this place. I chuckle as I remember seeing new signs in the area stating unequivocally, “you could die here.” I suspect this is meant to intimidate, but I can’t help the thought that to die here would not be the worst of fates.

Just above a downstream confluence with another canyon, my home for the night is in another grassy clearing, this one under a pair of old trees, surrounded by vibrant skunkbush and allowing long views up and down the canyon. Tomorrow I will traverse the deep pools separating me from the confluence, and make my way back up the other canyon.

It may seem abrupt to end the story here, to not mention the contemplation and the soul-searching and the crying, but the next two days were, in so many wonderful ways, more of the same. I think that if Henri Cartier-Bresson, master of the “decisive moment,” was to join me on one of these hikes, he would die of boredom. Nothing here happens decisively, nothing demands quick action, nothing breaks the soothing flow of water and time, the curving walls always disappearing around some bend, obscuring what surprises and beauty may lie beyond. Maybe I really shouldn’t go back. Maybe next time.

Who will tell whether one happy moment of love or the joy of breathing or walking on a bright morning and smelling the fresh air, is not worth all the suffering and effort which life implies. ~Erich Fromm

The Front Porch

October 11, 2018

Experiences, Not Moments

Under this fine rain I breathe in the innocence of the world. I feel colored by the nuances of infinity. At this moment I am one with my picture. We are an iridescent chaos… ~Paul Cézanne

I recall the satisfying fatigue permeating my body as I arrived at my campsite after wrapping up a workshop. Alone again in the desert, I wandered among the sparse tall grasses surrounding my camp. I felt rewarded to have the world to myself—the comforting views of familiar geology and flora, the wonderful smells of desert plants after the rain, the silence, the breeze on my skin, the play of sunbeams and cloud shadows projected on the giant screen of red cliffs before me, the mind relaxing into solitary normalcy after a few days among people.

And then, a sudden realization. Looking toward the setting sun through the glowing grasses, enchanted by the ethereal glow and the slow rhythmic swaying of the delicate stems, I had, as they say, “a moment.” A vivid memory emerged—a childhood meander in another field, in another life. So complete and visceral was the recollection that for a brief period I was that child again, seeing, thinking, feeling, as I had all those years ago. I was struck by the sense of intense fascination with the world that marked so many of my earliest experiences in the wild. My present self was still there, observing, recalling, and jarred by remembered sensations I have long forgotten I could feel. A grim realization soon emerged—how removed I’ve become from the purity and power of such feelings in the course of becoming an adult.

Surprised, I stopped in my tracks. I wanted to sustain the mix of emotions I have not felt in a long time, and to regain the ability to experience the world with such wonder again as a matter of course. Can I? I felt the sting of tears about to form, and I let them. In the course of seconds, or perhaps minutes, more memories and sensations emerged as I looked into the aura of tiny halos among the grasses. I had lost sense of time. My mind transfixed, enchanted, surprised and overwhelmed by the magnitude of emotions and questions, by the memory of what I was and what I became, and by anxiety and hope for what I may yet become.

But of course, I did not really have a moment. There are no moments. Moments exist in theory alone. To live, to feel, to experience, to think, is to be in a constant state of becoming. It is the dialectic nature of living, and why a living experience cannot be contained in a moment any more than a movie can be contained in a single frame.

Alfred Stieglitz pondered the ability of images to convey faithfully all dimensions of an experience. He referred to this ability as equivalence. He wrote, “What is of greatest importance is to hold the moment, to record something so completely that those who see it will relive an experience of what had been expressed.” Alas, what Stieglitz is describing is only possible to an extent, and not a great one at that. A singular moment cannot contain the richness of an experience. However, a moment of encounter with a photograph may prompt a new experience—the experience of the viewer, rather than that of the photographer.

The viewer may glean, infer, guess, or make up dimensions of the perceived experience based on a momentary impression. If the photographer is skilled in the art of self-expression, the viewer may perhaps even try to relate to the thoughts and sensations expressed, and to assimilate them into subjective sensibilities. But, while sharing some commonalities, the viewer’s experience and the photographer’s experience are never the same. It is the challenge of the expressive photographer to find sufficiently universal metaphors so as to keep the two experiences sufficiently similar in their important details.

But the viewer can never be certain of meanings inferred from visual metaphors. Lacking the specificity of words, visual metaphors are ambiguous by nature. It is precisely this ambiguity that lends photography expressive powers beyond just illustrative ones. It is the quality that liberates photography from the tyranny of objective reality, and that allows photographs to prompt stories of the photographer’s making, rather than the camera’s.

The flow of time cannot be arrested. A moment in itself is meaningless and minuscule—a quanta of experience imperceptible to the senses. This may seem an odd realization for a photographer. Consider some writings on the importance of moments in photography, which may seem in contradiction. For example, Susan Sontag, in her book, On Photography (a scathing critique of the medium), wrote, “All photographs are memento mori. To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.” She was wrong. To see a photograph is far from participating in another’s story—it is to stop that story and to branch out a new story in which the viewer exists, judges, and brings personal sensibilities and interpretations not shared by the photographer. To freeze a moment is to take that moment out of context, to sever it from the preceding events and from those that will follow—to make irrelevant the passage of time.

Edward Steichen correctly observed, “Photography is a medium of formidable contradictions.” He then explained erroneously, “It [photography] is easy because its technical rudiments can readily be mastered by anyone with a few simple instructions. It is difficult because […] the photographer is the only imagemaker who begins with the picture completed. His emotions, his knowledge, and his native talent are brought into focus and fixed beyond recall the moment the shutter of his camera has closed.” Wrong. After the shutter is closed, there remains a boundless array of creative, expressive possibilities still available to the photographer to influence a viewer’s perception. The photographer may continue to refine, to rethink, and to remake a photograph for years and decades after the film or sensor had been exposed.

There is no moment, at least not in the sense of something representing an experience. There are stories continuously unfolding—the story of the photographer, the stories of the things portrayed, the story of the time in which the photograph was captured, the story of the viewer, the story of the viewer upon seeing the photograph, and so on. Each time the photograph is viewed, all stories converge to a subjective perception in the mind that viewed it. As Sally Mann wrote, “All perception is selection, and all photographs—no matter how objectively journalistic the photographer’s intent—exclude aspects of the moment’s complexity. Photographs economize the truth; they are always moments more or less illusorily abducted from time’s continuum.”

Some consider realism to be photography’s greatest strength, but it is also true that the expectation of realism, in expressive contexts, may be photography’s greatest handicap. The more realistic the photograph, the less expressive it is of the thoughts and personality of the photographer—the things not in front of the lens, not reflecting light, not even having material qualities. This is not to say that photography is incapable of portraying such things, but it is to say that an expressive photograph must be, in the words of Ansel Adams, a “departure from reality.” And I agree completely with another of Adams’s assertions, which is this: “Most creative photographs are departures from reality and it seems to take a higher order of craft to make this departure than to simulate reality.”

What can be easier in photography than to portray things as they are? Conversely, what can be more challenging in photography than to express things of the photographer’s mind—personal and intangible things not detectable by optics and sensitized materials—within the naive expectation of objective, realistic representation? To accomplish such expression within some “decisive moment,” is patently impossible. A decisive moment is either entirely a product of circumstances outside the photographer’s control (and therefore not expressive of the photographer’s mind), or it is an idea arising in the mind of the photographer and that, within the moment, has no tangible qualities perceptible by others. Self-expression cannot be abstracted to that degree. There must be a what, a why, and a how to have experience, and an investment of skill to express it; all amounting to a complex and prolonged succession of moments before the photograph is even perceived by another (who, in turn, will require another sequence of moments to recognize, process, and experience it).

I believe that the fallacy of “freezing a moment” is the reason so many photographers restrict their work to objective representation. Attempting to transcend such objectivism by freezing a moment is an exercise in frustration, and likely also to diminish the very experience the photographer wished to express. An expressive photograph is not the product of a moment, it is a continuity of an experience. To be expressive, the camera should not be considered a scalpel to carve out some moment from reality; it should be considered a means of overlaying reality with subjective meaning—a means of mindfully and deliberately constructing meaning by way of composing skillfully chosen visual metaphors as the experience unfolds.

Moments give rise to experiences. Experiences give rise to life. Life gives rise to art.

September 22, 2018

Earning Your Medals

By offering here something of my understanding of photography, I can continue to earn the images that I have been given. ~Minor White

There is a tendency among photographers to seek definitive, objective, answers to ambiguous and subjective questions—a futile endeavor, to be sure. One such question that arises with some regularity is this: what makes a great photograph?

In the way I approach my photography and in the way I appreciate the photography of others, a great photograph is not the same thing as a photograph of something great. This is because, to me, art worthy of being considered great should be an expression of the greatness of the artist.

When it comes to artistic expression, not all greatness is the same. Some photographs may be considered great by virtue of requiring great skill, great effort, or great luck to accomplish. But those images I consider the greatest are those that, above all else, result from great creativity, great power of expression, and great depth of feeling. These qualities are not qualities of the things photographed, they are expressions of qualities of the mind of the artist.

I’m hardly knowledgeable enough to use sports metaphors, but these thoughts occurred to me during the last Olympic games: I can beat Usain Bolt to the finish line on any race, and I can adorn my display case with more gold medals, in swimming or any other sport, than Michael Phelps. I can do the former by driving a car to the finish line, instead of running; and the latter by having someone make me copies of whatever medals I want. Will I be worthy of the same honors as Bolt and Phelps just by virtue of reaching the finish line first or possessing some number of medals? What makes such athletes worthy of being considered great is not merely the fact that they crossed the finish line first, but the way in which they did so: by honing their skills over years of training, by perseverance and fortitude, and by proving their superior abilities.

Regrettably, in the judgment of the greatness of photographs, taking shortcuts to the finish line and boasting about metaphorical “forged medals,” often make no difference in the judgment of artistic merit. Photographs are rarely evaluated on their originality, or by the degrees of creativity, self-expression, and cognitive effort, that went into their making. Most often, photographs are evaluated by their aesthetic appeal alone.

Is it any wonder that so many take the easy route to the finish line, when the judges don’t seem to care if you ran or drove to get there? One has to do little more than to follow directions and to make copies of others’ compositions to win the same accolades and prestige as the original, if not more.

Today, just about anything can be stamped, “art,” and be considered valid as such, at least by some. Although we may argue about what makes art good or bad or great, none of us is empowered to decide for others what is or is not art. Therefore, the designation of a thing as a work of art, in itself, is meaningless. Whether a photograph is art is less important than whether the photographer is an artist. Art is art, just like a medal is a medal, but if you own a medal without earning it—without years of training, without running a race, without dipping a toe in a pool, without playing a game—can you call yourself an athlete?