Rod Miller's Blog, page 28

November 4, 2016

A pair to draw to.

There’s a long list of pairs who displayed a certain chemistry on the silver screen. Bogie and Bacall. Hope and Crosby. Bert and Ernie. Brad and Angelina. Andy Griffith and Don Knotts. Roy Rogers and Dale Evans. Woody and Buzz Lightyear. Lucille Ball and Vivian Vance. Jerry Lewis and Dean Martin.But for my money, the most enjoyable acting duo has to be Paul Newman and Robert Redford. Without them, I think Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid would be just another ordinary, everyday Western. But their rib-tickling repartee and witty quibbling made the characters come alive. They were likable, engaging, and altogether enjoyable. I suspect screenwriter William Goldman got a big kick out of seeing those two bring his words to life on the big screen. I still watch Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kidfrom time to time, and it’s as good today as it was back in 1969 when the world was a whole different place. Newman and Redford did it again in The Sting—an altogether different kind of movie and every bit as remarkable. Too bad they didn’t make more movies together. As a pair, they can’t be beat. Then again, there’s always Robert Duvall and Tommy Lee Jones as Gus McCrae and Woodrow Call….

Published on November 04, 2016 06:52

October 26, 2016

My Favorite Book, Part 3.

When my wife and I married lo these many years ago, included in the union was her full set of the Time-Life series The Old West. Now, many historians pooh-pooh the books, and there are some inaccuracies and exclusions and such. But when it comes to an overview of pretty much every aspect of the history of the American West, with volumes covering most major topics, the series is hard to beat. Over the years (and even now) I have spent many an hour both browsing the books at random and researching a particular subject. While the series may not be a good place to end your research, they represent a fine place to start.Included are works on cowboys, Indians, pioneers, ranchers, frontiersmen, Forty-Niners, Texans, trailblazers, gunfighters, Spaniards, and so on—more than twenty-five volumes in all, including a one-volume index that covers the whole set. The Old West isn’t the best thing my wife brought to our marriage, but it’s certainly one I’ve enjoyed—enough to be included among my favorite books.

Published on October 26, 2016 07:42

October 13, 2016

Lies They Tell Writers, Part 33: The “Western” is dead.

Ever since I started paying attention to books and such from a writer’s perspective, as well as a reader’s, I have heard over and over again that the Western is dead. This point of view, I think, results from the dominance of Westerns for decades, not only in books but in magazines, television series, and feature films. During the early to middle years of the twentieth century, Westerns—mostly of the shoot-’em-up variety—were everywhere you looked, and the genre dominated entertainment like no other has since.Folks who remember those days decry the lack of Westerns nowadays and mourn the relative dearth with predictions and forecasts of doom and gloom about the future (or lack thereof) of entertainment based in the American West.Don’t you believe it. While it is true that Westerns don’t dominate the market like they once did, and the popularity of Western stories in the traditional style has waned somewhat, there is still plenty of writing about the West out there. One element that keeps the Western alive and thriving is a more expansive—and realistic—view of the West among writers, publishers, and producers. And readers. Female characters have emerged into more prominent roles. Beyond horseback good guys vs. bad guy plots are stories about towns, trails, trade, and more. And the modern-day West has become the setting for stories that rely on the unique aspects of the region. Then there’s the fact that nonfiction about the West—both historical and contemporary—enjoys widespread popularity. Another factor is the spread of Westerns into other genres. You’ll find more and more mysteries, thrillers, romances, even science fiction set in the West. All in all, things look pretty good Out West, whether you’re a writer or reader who enjoys the landscapes, climates, economies, cultures, and history that make our region the defining facet of our country.

Published on October 13, 2016 05:00

October 2, 2016

Rawhide Robinson Rides On.

Rawhide Robinson—that ordinary cowboy who often finds himself involved in the extraordinary—has been good to me. In his first appearance, Rawhide Robinson Rides the Range: True Adventures of Bravery and Daring in the Wild West , he won a Western Writers of America Spur Award. For his second novel, Rawhide Robinson Rides the Tabby Trail: The True Tale of a Wild West CATastrophe , he was a Spur Award Finalist and won a Western Fictioneers Peacemaker Award. I’m happy to announce that our cowboy hero will be back. I recently received signed contracts from Five Star Publishing for Rawhide Robinson Rides a Dromedary: The True Tale of a Wild West Camel Caballero. As you no doubt discern from the title, the adventure that’s the basis for this book has to do with camels. It was inspired by and is loosely—very loosely—based on the US Army’s attempt to acquire and employ camels in the southwestern deserts back in the nineteenth century. In its pages, Rawhide Robinson finds himself sailing the high seas, experiencing exotic Levantine ports of call, and forking a camel in the Texas outback. Of course Rawhide Robinson wouldn’t be Rawhide Robinson if he didn’t spend time around the campfire spinning tales about his supposed adventures and escapades. No release date as yet. I’ll keep you informed.

Published on October 02, 2016 07:05

September 25, 2016

My Favorite Book, Part 2

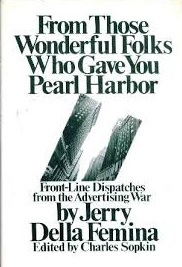

Long, long ago in a year that had a nine and a seven in it, I was working at a small television station in Idaho. I was a master control switcher, directed newscasts and interview shows, put together local commercials, dubbed videotapes, and performed various other production tasks. One day a coworker, who worked downstairs and wrote local commercials, left for a job in radio. “You have a degree in journalism,” the boss said. “You must know how to write. Do you want to write commercials?” I said yes. But I knew nothing about advertising—how and why it worked, who did it, where, how, or any of that stuff. Learning that stuff seemed like a good idea, so I visited the library and started home-schooling myself. One of the books I read was From Those Wonderful Folks Who Gave You Pearl Harbor, by an irreverent and accomplished New York City advertising agency copywriter (and later agency owner) named Jerry Della Femina. He made the advertising agency business sound fun—and frustrating, challenging, annoying, and exasperating. But mostly fun.The book led me to pursue work as an advertising agency copywriter. I’ve been at it nearly forty years since; now part-time. While not as glamorous as Madison Avenue, working at agencies in Idaho, Nevada, and Utah has been much as Della Femina described it in that influential book I count among my favorites. Besides all the fun, the job hasn’t involved much heavy lifting and seldom requires breaking a sweat. And, somehow, it led me to wonder—after writing advertising for some twenty years—if maybe I could write a poem. Now look.

Published on September 25, 2016 07:41

September 15, 2016

Lies They Tell Writers, Part 32: details, details, details.

Many writing instructors encourage, and many writers practice, descriptive writing rife with details. They’ll tell you descriptive details of people and places and things that involve all the senses make stories more interesting and help readers create mental pictures. I’ve heard “critics” in critique groups complain about lack of description of characters in the writing of others, and say that details about characters’ appearance and manner and such will help us “get to know them.”Maybe. Maybe not. There’s another approach—one I prefer—that gives lie to that norm. It is summed up admirably by these two simple rules:“Avoid detailed descriptions of characters.”“Don’t go into great detail describing places and things.” That rule goes on to advise avoiding such descriptions “unless you’re Margaret Atwood and can paint scenes with language. You don’t want descriptions that bring the action, the flow of the story, to a standstill.”I put those rules in quotation marks because they’re not mine. They belong to the late, great Elmore Leonard—author of many best-selling novels and winner of numerous literary awards, including the Owen Wister Award for Lifetime Achievement from Western Writers of America and induction into the Western Writers Hall of Fame. Leonard’s Western works include Last Stand at Saber River, Hombre, Valdez is Coming, and “Three Ten to Yuma.” He was also a giant in crime fiction, with several prize-winning novels (many that became movies) to his credit. His sparse, bare-bones style appeals to me. And, beyond avoiding bringing a story to a standstill with detailed descriptions, Leonard’s approach is more involving for readers—it allows us to participate in the story, to create our own mental pictures of people and places and things, rather than have them handed to us. In his award-winning and best-selling novel All the Pretty Horses, Cormac McCarthy—despite his ability to write florid descriptions—provides not a single clue as to the appearance of the book’s main characters, John Grady Cole and Lacey Rawlins. We could go on. The point is, there’s more than one way to write about people, places, and things. So don’t believe everything they tell you—at least not in every detail. There will be further discussion of this topic—in greater detail—to come.

Many writing instructors encourage, and many writers practice, descriptive writing rife with details. They’ll tell you descriptive details of people and places and things that involve all the senses make stories more interesting and help readers create mental pictures. I’ve heard “critics” in critique groups complain about lack of description of characters in the writing of others, and say that details about characters’ appearance and manner and such will help us “get to know them.”Maybe. Maybe not. There’s another approach—one I prefer—that gives lie to that norm. It is summed up admirably by these two simple rules:“Avoid detailed descriptions of characters.”“Don’t go into great detail describing places and things.” That rule goes on to advise avoiding such descriptions “unless you’re Margaret Atwood and can paint scenes with language. You don’t want descriptions that bring the action, the flow of the story, to a standstill.”I put those rules in quotation marks because they’re not mine. They belong to the late, great Elmore Leonard—author of many best-selling novels and winner of numerous literary awards, including the Owen Wister Award for Lifetime Achievement from Western Writers of America and induction into the Western Writers Hall of Fame. Leonard’s Western works include Last Stand at Saber River, Hombre, Valdez is Coming, and “Three Ten to Yuma.” He was also a giant in crime fiction, with several prize-winning novels (many that became movies) to his credit. His sparse, bare-bones style appeals to me. And, beyond avoiding bringing a story to a standstill with detailed descriptions, Leonard’s approach is more involving for readers—it allows us to participate in the story, to create our own mental pictures of people and places and things, rather than have them handed to us. In his award-winning and best-selling novel All the Pretty Horses, Cormac McCarthy—despite his ability to write florid descriptions—provides not a single clue as to the appearance of the book’s main characters, John Grady Cole and Lacey Rawlins. We could go on. The point is, there’s more than one way to write about people, places, and things. So don’t believe everything they tell you—at least not in every detail. There will be further discussion of this topic—in greater detail—to come.

Published on September 15, 2016 07:51

September 5, 2016

My Favorite Book, Part 1.

Readers—and writers—are often asked to name their favorite book. The question leaves most of us, it seems, struggling for an answer. Here’s why. A friend sent me an article a while back in which a writer was asked to write about her favorite book. She concluded that there have been several books that were her favorites at various times of life. That sounds right to me. And I would add that most of those favorites remain favorites. There are books I read decades ago that I go back to and enjoy all over again. There are others that stick in my memory that I haven’t re-read, but plan to someday. And there are books I enjoyed at the time, but not enough to be my “favorite.”Back in my high school years, perhaps as early as junior high, I engaged in what we would now call “binge reading” the short novels of John Steinbeck. Of Mice and Men. Cannery Row. Tortilla Flat. The Red Pony. The Pearl. I read those, and others, back then and I have read them over and over since. Later, I likewise enjoyed his longer books—East of Eden, The Grapes of Wrath, The Winter of Our Discontent, Travels with Charley…. I have read those and others more than once, and will likely read them again.Steinbeck is, perhaps, the first writer I read whose way of writing I noticed. Beyond the stories, beyond the characters, I enjoyed the words he chose and the way he assembled those words into phrases and sentences that, despite what they said, were engaging all on their own and a joy to read. They were then, and they still are. Given all that, I guess my favorite book is Tortilla Flat. Or The Red Pony. Or something else by John Steinbeck.Or maybe something else altogether. It all depends.

Published on September 05, 2016 06:41

August 26, 2016

Sitting in judgment.

Literature is art. And art is, to some degree, subjective. What’s good and what isn’t is very much a matter of taste. That’s why I am always surprised when asked to judge a writing contest. To think someone, somewhere, thinks my literary palate is refined enough to pass judgment on a passel of poems or collection of fiction always astonishes me. But they ask. I’ve been asked over the years by organizations as various as a cowboy cultural society from Canada, the outfit that runs the National Finals Rodeo, statewide writers’ groups from at least three states and a double handful of smaller groups from various localities, an international society of professional writers, and more than a few poetry performance competitions. What’s more surprising is that many of them ask me back.It isn’t always easy trying to be objective about something so subjective. But there are certain standards that ought to apply—basic things like spelling, syntax, structure, grammar, form, composition, communication, and such. Poorly proofed and edited works are easily discarded. After that, it can get tough. A story that grabs and won’t let go. Clever use of language. Word choice. Originality. Rhythm. Pace. Use of literary technique. And on and on, into demonstrations of skill that are hard to define—but you know them when you read them. It’s a pleasure to reward creativity, skill, effort, and accomplishment. And while it is never pleasant to quickly cast aside an entry that doesn’t measure up—sometimes mere pages past the cover—you do what you have to do. As my friend Dusty Richards says, which he says the late, great Elmer Kelton said: “You don’t have to drink a whole bottle of whiskey to know it’s bad.”

Published on August 26, 2016 05:38

August 18, 2016

Two-gaited horses.

While growing up in the ’50s and ’60s, we watched a lot of Westerns on television at my house. Dad, who was an inspired horseman and worked as a cowboy as often as not, got a kick out of them. He more or less saw them as comedies. The stereotypical characters and guns that never needed reloading and repetitive stories were part of that. But, mostly, it was the horses. While he never said so, he probably believed the casting directors who hired equines must have specified that only two-gaited horses need apply. A brief explanation: where we come from out West, horses travel with four basic gaits—walk, trot, lope, and run. (Elsewhere, lope and run are often referred to as canter and gallop.) But if you believed what you saw on the screen, horses have only two gaits: walk and run. Sometimes, a “cowboy” (which, on television, included all kinds of characters who wouldn’t know which end of the cow gets up first) would mount up in town and walk his horse down the street (about the only time TV horses were seen to walk). But more often, he would swing into the saddle and lay the spurs to his horse and race off down the street at a dead run raising a cloud of dust. And he would run his horse nonstop along wagon roads, up mountain trails, across wide deserts, through streams, and everywhere else he went until reining up in a sliding stop at his destination. It’s likely that horses with stars in their eyes back then rehearsed the walk only briefly and ignored the trot and lope altogether, concentrating on the endless run in order to secure a part in a television horse opera. Real horses, if they watched their on-screen counterparts, probably grinned at their high-speed antics like Dad did. The lengthy horseback sequences in the Coen brothers’ version of True Grit are among many reasons I admire that movie. Endless plodding (at a walk) across the landscape might seem tedious for some to watch. But it doesn’t hurt to give viewers a taste of the monotony that traveling horseback can be. Of course, folks who know horses know you can (and do) trot or lope at times to change things up a bit—you just won’t see it happen on TV.

Published on August 18, 2016 09:11

August 4, 2016

Lies They Tell Writers, Part 31: Don’t sweat the small stuff.

I lied in the title. No one knowledgeable, to my knowledge, tells writers to ignore the essentials—small stuff—like spelling and grammar and basic facts in manuscripts and books.But as often as those things are ignored nowadays, you’d think it was part of the curriculum somewhere. Time was, it was so difficult to find a spelling error in a published book that it was noteworthy. No longer. With the advent of do-it-yourself self-publishing, the proliferation of small presses who can’t afford copy editors and proofreaders, and even the staff cutbacks at major publishers, errors of the simplest kind now slip through regularly. As I write this I am in the middle of a novel I was asked to review, and on several occasions the author has called those leather straps you use to control a horse “reigns.” It’s a homonym, sure, but it’s such a ridiculous error there’s no excuse for it. Likewise his saying a just-planted wheat field had been “sewn.” That one had me in stitches. Then there are incorrect facts, if such an oxymoron exists. Some time back I read a novel by an author who has written many, many paperback Westerns for major publishers. And yet he continually referred to the “traces” on a harnessed team as if they were the lines (or reins, if you’d rather, but lines is the more common term). “Traces” are something else altogether on a harness, and he ought to know the difference—or not use the word if he doesn’t. We all make mistakes. But there are mistakes, and there are mistakes. Sometimes writing instructors will tell you to blow by that simple stuff in the initial draft in order to get the story down. But that is with the expectation that you’ll go back and fix it. Unfortunately, too many authors—and publishers—don’t fix it. And that shows a lack of respect for readers. Of all things, a writer ought to be literate.

Published on August 04, 2016 06:22