Marty Halpern's Blog, page 5

August 9, 2019

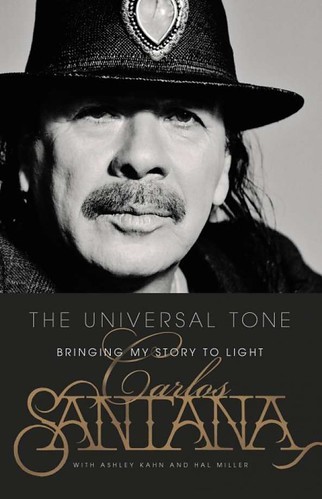

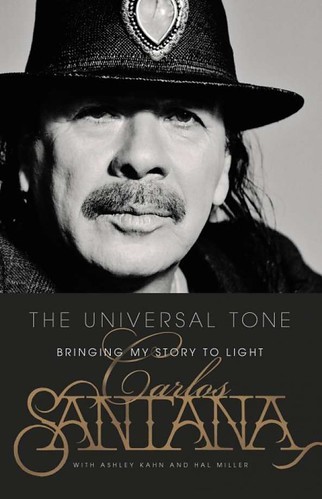

Chapter 20 Excerpt: The Universal Tone by Carlos Santana

If you haven't been keeping up on my blog post excerpts from Carlos Santana's autobiography,

The Universal Tone: Bringing My Story To Light

[image error], then here's a few significant points about the book:

If you haven't been keeping up on my blog post excerpts from Carlos Santana's autobiography,

The Universal Tone: Bringing My Story To Light

[image error], then here's a few significant points about the book:The book was published in 2014 by Little, Brown and Company. NPR (National Public Radio) named The Universal Tone one of its Best Books of 2014. It received a starred review in Kirkus (and anyone who knows Kirkus, knows that it's nearly impossible to even get reviewed by Kirkus!). And the book went on to win the American Book Award in 2015.

So, why aren't you reading this book already?

From Chapter 20:In a funny way, my life has always been local—everything that happens comes from where I am. John Lee Hooker was living in the [San Francisco] Bay Area at this time. He was the Dalai Lama of boogie. Shoot, he should have been the pope of boogie as far as I'm concerned. We got to know each other. A lot of times we'd be playing, and he'd say, "Carlos, let's take it to the street," and I'd say, "No, John, let's take it to the back alley," and he'd say, "Why stop there? Let's go to the swamp." I miss him so much.A John Lee boogie pulls people in as strongly as gravity holds them to this planet. He is the sound of deepness in the blues—his influence permeates everything. You can hear him in Jimi Hendrix's "Voodoo Child (Slight Return)" or in Canned Heat's boogies. That's nothing but John Lee Hooker. When you hear the Doors, that's a combination of John Lee and John Coltrane. That's what they do; that's the music they love....In '89 John Lee was local to the Bay Area. He was living not far from me, in San Carlos, which is near Palo Alto. We met a few times and talked, and at some point he actually invited me to his house for his birthday, which was the first time I really hung out with him. I brought a beautiful guitar to give him.When I walked in, I saw that everyone was watching the Dodgers on TV, because that's John Lee's favorite team. He was eating fried chicken and Junior Mints. No kidding—Junior Mints. He had two women on the left and two on the right, and they were putting the mints into his hands, which were softer than an old sofa. I stepped up and said, "Hi, John. Happy birthday, man. I brought you this guitar, and I wrote a song for you.""Oh, yeah?""It sounds like the Doors doing blues, but I took it back from them and I'm returning it to you and I'm calling it 'The Healer.'John Lee chuckled. He had a slight stutter that was very endearing. "L-L-Let me hear it."I started playing, and I made it up right on the spot—I knew how he did the blues, how he played and sang. "Blues a healer all over the world..." He took the song, and when he recorded it, he added to it in his own way. I said, "Okay, we've got to go to the studio with this, but I just want you to come at one or two tomorrow afternoon, because I don't want you to be there all day, man. I just want you to come in and just lay it. I'm going to work with the engineer—get the microphones ready, get the band to the right tempo. You just show up.""Okay, C-C-Carlos."When John Lee showed up we were ready. I got the band warmed up—Chepito, Ndugu, CT, and Armando—no bass, because Alphonso didn't make that gig. John Lee and Armando were checking each other out like two dogs slowly circling each other—they were the two senior guys there, and you could really tell that Armando needed to know who this new older guy was. He was looking at him slowly, all the way from his feet up to his hat. Just sizing him up. John Lee knew it, but he just sat there, tuning his guitar, chuckling to himself.Armando threw down the first card. "Hey, man, you ever heard of the Rhumboogie?" He was talking about one of the old, old clubs on the black music circuit in Chicago, opened by the boxer Joe Louis back before I was even born. John Lee said, "Yeah, m-m-man. I heard of the Rhumboogie." Armando had his hands on his waist like, "I got you now." He said, "Well, I played there with Slim Gaillard.""Yeah? I opened up there for D-D-Duke Ellington."I saw what was going on and stepped in. "Armando, this is Mr. John Lee Hooker. Mr. Hooker, Mr. Armando Peraza."We did "The Healer" in one take, and the engineer said, "Want to try it again?"John Lee shook his head. "What for?"I thought about it and said, "Would you mind going back in the booth, and when I point at you, would you be so gracious as to give us your signature—those mmm, mmm's?" John Lee chuckled again. "Yeah, I can do that." I said okay. That was the only thing he overdubbed that day—"Mmm, mmm, mmm.""The Healer" helped bring John Lee back for his last ten years. He had a bestselling album and a music video—everything he deserved. We started to hang out more and play together. I would see him in concert, too. He had a keyboard player for many years—Deacon Jones—who used to get up onstage and say, "Hey! You people in the front—you might need to get back a little bit, because the grease up here is hot. John Lee's about to come out!" I have so many stories like that as well as stories about John Lee calling me—sometimes during the day, but, like Miles [Davis] did, mostly late at night.I remember John Lee opening for Santana in Concord, California, and we had finished our sound check and he'd been waiting for me on the side of the stage. We were done, and he started talking to me while we walked away. The soundman came running up. "Mr. Hooker, we need you to do a sound check, too.""I don't need no sound check.""But we have to find out how you sound."John Lee kept walking. "I already know what I sound like." End of discussion.

"The Healer," John Lee Hooker, featuring Carlos Santana:

Published on August 09, 2019 08:32

August 6, 2019

Chapter 19 Excerpt from: The Universal Tone by Carlos Santana

I've been gracing this blog with excerpts from Carlos Santana's autobiography,

The Universal Tone: Bringing My Story To Light

[image error], published in 2015 by Little, Brown and Company. There is so much rich material in this book that I'm actually having difficulty deciding what to post since I don't want the publisher (or Carlos himself) chastising me for quoting too much material! But if you enjoy the music of Santana, if you enjoy autobiographies, if you enjoy reading about a person's spiritual journey, then this is the book for you.

I've been gracing this blog with excerpts from Carlos Santana's autobiography,

The Universal Tone: Bringing My Story To Light

[image error], published in 2015 by Little, Brown and Company. There is so much rich material in this book that I'm actually having difficulty deciding what to post since I don't want the publisher (or Carlos himself) chastising me for quoting too much material! But if you enjoy the music of Santana, if you enjoy autobiographies, if you enjoy reading about a person's spiritual journey, then this is the book for you.From Chapter 19:In 1987, when Sal [Salvador, Carlos's son] was just four, I was jamming in the studio with CT [Chester Thompson, keyboard player] when one of those magic moments happened. But the engineers were still messing with calibrating something, and we wanted to record what we were doing right then. "Hit RECORD right now! Get this on tape, man — I don't care how you do it" So we got it on a two-track reel-to-reel — one track for CT, one for me. Just as I played the last note and it faded, the tape ran out — flub, flub, flub. Years later I found out that one of Stevie Ray Vaughan's blues was recorded exactly the same way — suddenly, on the spot, on a two-track reel-to-reel. And just as he played the last lick, the same thing happened — the tape ran out. The really weird thing? It was the same engineer both times — Jim Gaines.I have to say a word about Jim and the other engineers Santana has been blessed to have in the studio and sometimes on the road. Fred Catero, Glen Kolotkin, Dave Rubinson, Jim Reitzel — they've all been instrumental in our success through the years, and I feel they all need to be honored. Jim Gaines worked with so many great artists, from Tower of Power to Steve Miller to Stevie Ray Vaughan, before he came to us. He brought a really earthy quality to the sound and did what he did without any ego — he was a pleasure to work with. He was with Santana just as things were going from analog to digital, so he helped with that transition and was as great with the computer as he was with the knobs. Recording technology was up to thirty-six tracks at that time, before Pro Tools came around, but he was really patient and knew what to say and when to say it in a very gentle way that would help make the music a lot more flowing.After that jam with CT in '87, Jim gave me a cassette of it, and I left it in the car. The next day Deborah [Carlos's wife at that time] went shopping in that car, and when she came back she asked me, "Why don't you play like that?" There was that question again, the one she asked after the Amnesty International concert — sometimes she'd say that and I'd have to think, "What does she mean?" Before I said anything she was already asking me the name of the song on the cassette."What song?""You know, that song you played with CT. I heard it and couldn't drive. I had to pull over."I decided to call it "Blues for Salvador," not only for Sal but also because San Salvador was going through some hard times then, with an earthquake and a civil war. That song inspired my last solo album as Carlos Santana. I love it because it has Tony Williams on it, and more of Buddy Miles's singing, and that band — CT, Alphonso, Graham, Raul, Armando, and the rest. I dedicated the album to Deborah, and the song "Bella," for Stella [Carlos's oldest daughter], is on there, too."Blues for Salvador" won a Grammy as the year's best rock instrumental performance — the first Santana Grammy, but not the last.Please feel free to scroll back through my blog posts for previous excerpts....

Published on August 06, 2019 16:45

July 31, 2019

July 27, 2019

Another Excerpt from: The Universal Tone by Carlos Santana

And yet another excerpt from

The Universal Tone: Bringing My Story To Light

[image error], an autobiography by musician Carlos Santana.

And yet another excerpt from

The Universal Tone: Bringing My Story To Light

[image error], an autobiography by musician Carlos Santana.From Chapter 9 yet again:I remember one time in 1988 I got into Chicago around five o'clock and was checking in to an airport hotel. The phone was already ringing in my room when I put the key in the door—it was Buddy [Guy]. "Hey, Santana! Listen, Otis [Rush] and I, we're waiting on your ass here. You got a pen? Write down this address and come on over."The address was that of the Wise Fools Pub, and I didn't waste any time. I got there early enough, when the place was only half full— Otis hadn't actually showed up yet, so Buddy and I took some solos, and we were just killing it. Then suddenly I saw that cowboy hat and toothpick come out of the shadows. It was like a scene in a movie. Otis looked around and walked through the crowd like he was in no hurry at all. This was his turf. He grabbed his guitar and stepped into the single spotlight, which hit his face in a very dramatic way. He leaned into the microphone and said: "Give them a hand, ladies and gentlemen!" Then quietly, almost to himself, he said, "Stars, stars, stars..."It was like Otis was saying, "Oh, yeah? You think these guys were good?" He plugged in and didn't even sing—he just went straight into round after round of an instrumental blues that showed us who the star really was. He was in the middle of a solo and hit a lick that had Buddy and me screaming like shrimp on a Benihana grill. We couldn't believe what he was able to get out of each note. It was like getting a real long piece of fresh sugarcane and peeling it with your teeth to get into the middle, where the sugar is, and the sound it makes when you suck the sap out of it and the juice starts running down your chin and onto your hands. That's what it was like when Otis was hitting those notes—nothing sounds or tastes better than that!Over the years I've gotten to know Otis and let him know how important his music is to me. He's not one for compliments, though—the first time we met at the Fillmore, I told him how incredible he sounded. His reply was, "Man, I got a long way to go." What—you? The guy who made "All Your Love (I Miss Loving)" and "I Can't Quit You Baby"? I think he's just one of those brothers who has a hard time validating his own gift, who's distant in his mind from his soul—except when he's playing. Not long ago Otis had a stroke, and he can't play anymore, and I make it a point to stay in touch, send his family a check twice a year, and let him know how much he's loved. He was never really one for words, but he'll still get on the phone and say, "Carlos, I love you, man." What can I say? He changed my life.[1]

---------------Footnote:

[1] The Universal Tone was published in 2014; blues legend Otis Rush passed away on September 29, 2018.

Published on July 27, 2019 15:11

July 26, 2019

More from: The Universal Tone by Carlos Santana

Still reading -- and thoroughly enjoying -- the Carlos Santana autobiography entitled

The Universal Tone: Bringing My Story To Light

[image error].

Still reading -- and thoroughly enjoying -- the Carlos Santana autobiography entitled

The Universal Tone: Bringing My Story To Light

[image error].Here's yet another excerpt, this one from Chapter 9:

At Woodstock, I think Santana played a great show, but I do not think Santana was responsible for all that happened afterward. That's like a cork floating on top of a wave in the middle of the sea, bobbing up and down and telling itself it's controlling the entire ocean—that's an ego out of control.There were a lot of things that nobody planned at Woodstock but that made it work for us. If we hadn't stayed in the town of Woodstock for the week before the festival, we probably would have gotten stuck in traffic and showed up late or not made it at all. And if some groups hadn't been late getting up there, we wouldn't have gone on early in the day and we could have gotten caught in the rain later that day and had our show messed up or even been electrocuted or forced to quit. And if any of that happened, maybe "Soul Sacrifice" would not have made it into the Woodstock movie and nobody would have seen us.There were a lot of angels stepping in and making a way for us—the more time goes by, the more I can say that with clarity and confidence. I'll say it again: the one angel who deserves the most credit is Bill Graham. He got us the gig when nobody had heard of us. We had just finished our first album, but it hadn't been released. When Michael Lang, who was producing the festival, asked Bill for his help, Bill told him, "Okay, this is a big endeavor. I'll help you with my connections and my people. They know how to do this. But you need to do something for me—you need to let Santana play.""Okay, but what's Santana?""You'll see."

Published on July 26, 2019 17:41

July 25, 2019

Rutger Hauer (January 23, 1944–July 19, 2019)

In Memory of Rutger Hauer

I've seen things you people wouldn't believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain. Time to die.

Published on July 25, 2019 12:11

July 24, 2019

Still Reading: The Universal Tone by Carlos Santana

Continuing from my previous blog post on Carlos Santana's autobiography,

The Universal Tone: Bringing My Story To Light

[image error]....

Continuing from my previous blog post on Carlos Santana's autobiography,

The Universal Tone: Bringing My Story To Light

[image error]....From Chapter 7:...I had been so excited to see [B. B. King] for the first time in February of 1967. Finally, the teacher I had started with and kept coming back to was coming to the Fillmore! The first time I had heard his music was in Tijuana at Javier's house—all those LPs on the Kent and Crown labels.B. B. was the headliner after Otis Rush and Steve Miller. Another great triple bill. I was there for the opening night. Steve was great, Otis was incredible, and then it was B. B.'s band onstage, vamping. (Later on, I learned what his close friends call him—just B.—but in my mind he will always be Mr. King.) Then B. walked onstage, and Bill Graham went up to the mike to introduce him: "Ladies and gentlemen, the chairman of the board—Mr. B. B. King!"It was like it had all been planned to build up to this. Everything just stopped, and everyone stood up and applauded. For a long time. B. hadn't even hit a note yet, and he was getting a standing ovation. Then he started crying.He couldn't hold it in. The light was hitting him in such a way that all I could see were big tears coming out of his eyes, shining on his black skin. He raised his hand to wipe his eyes, and I saw he was wearing a big ring on his finger that spelled out his name in diamonds. That's what I remember most—diamonds and tears, sparkling together. I said to myself, "Man, that's what I want. This is what it is to be adored if you do it right."Gregg, Carabello and I saw B. in concert when he came back in December of '67, and I was able to study him almost in slo-mo, waiting for him to hit those long notes of his. I was thinking, "Okay, here it comes—he's going to go for it. There it is. That note just freaked out everybody in the place, man." People were in the hallelujah camp. I noticed that just before he would hit a long note, B. would scrunch up his face and body, and I knew he was going to a place inside himself, in his heart, where something moved him so deeply that it was not about the guitar or the string anymore. He got inside the note. And I thought, "How can I get to that place?"

Published on July 24, 2019 19:11

July 19, 2019

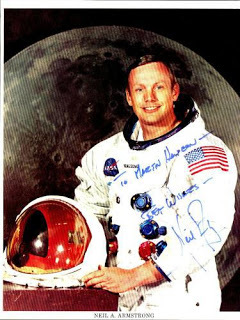

Apollo 11 Moon Landing: July 20, 1969

Published on July 19, 2019 19:36

Now Reading: The Universal Tone by Carlos Santana

Subtitled "Bringing My Story To Light," this is musician Carlos Santana's life story. His life began in Autlán, Mexico; he came of age in Tijuana; eventually ended up in San Francisco; and now he inhabits the entire world.

Subtitled "Bringing My Story To Light," this is musician Carlos Santana's life story. His life began in Autlán, Mexico; he came of age in Tijuana; eventually ended up in San Francisco; and now he inhabits the entire world.The Universal Tone [image error] was published by Little, Brown and Company in 2014. It's a massive book, totaling 536 pages, and that's not counting the numerous pages of photographs, dating back to Santana's childhood. The book was one of NPR's Best Books of 2014 and winner of the 2015 American Book Award. The Universal Tone also received a starred review in Kirkus (and anyone who knows Kirkus knows that it is nearly impossible to even get reviewed by Kirkus, let alone receive a starred review!)

Here are a few select excerpts from the book; these all focus on Santana's music influences and learning:

From Chapter 3:The blues is a very, very no-nonsense thing. It's easy to learn the structure of the songs, the words and the riffs, but it's not like some other styles of music—you can't hide behind it. Even if you are a great musician, if you want to really play the blues you have to be willing to go to a deeper place in your heart and do some digging. You have to reveal yourself. If you can't make it personal and show an individual fingerprint, it's not going to work. That's really where you find the magnificence in the simple three-chord blues, in the fingerprints of blues guitarists like T-Bone Walker, B. B. King, Albert King, Freddie King, Buddy Guy, and all the cats from Chicago—Otis Rush, Hubert Sumlin.There's a lot of misunderstanding about the blues. Maybe it's because the word means so many things. The blues is a musical form—twelve bars, three chords—but it's also a musical feeling expressed in what notes you play and how you play each note. The blues can also be an emotion or a color. Sometimes the difference is not so clear. You can be talking about the music, then the feeling, then what's in the words of a song. John Lee Hooker singing, "Mmm, mmm, mmm—Big legs, tight skirt / 'Bout to drive me out of my mind..." It's all the blues.

From Chapter 4:Charlie Parker said, "If you don't live it, it won't come out of your horn." I began to live my life, and my own sound began to come out of that closet and out of my guitar. It took a while—lots of gigs in Tijuana and in San Francisco. Lots of life experiences—growing up, leaving home, and coming back. Then, ultimately, leaving home for good.When you take your time and listen to the real blues guys, you discover that each one has his own sound and you can recognize them by things they do, all while realizing that they don't repeat themselves. When you really dig into a blues it's like riding a horse bareback in the night under full moonlight. The horse takes off, and he doesn't throw you off. You go up and down and flow with the rhythm of the ride, go through all these changes, and never repeat yourself.

Also from Chapter 4:I started to learn about phrasing, mainly from singers. Even today, as much as I love T-Bone or Charlie or Wes or Jimi, it's singers more than other guitar players that I like to hang with. If I want to practice or just get reacquainted with my instrument, I think it's best to hang with a singer. I don't sing, but I will put on music by Michael Jackson and I'll be right there with his phrasing, like a guided missile—I'll do the same thing with Marvin Gaye and Aretha Franklin. Or Dionne Warwick's first records—my God. So many great guitarists play a lot of chords and have great rhythm chops, and I can do that. But instead of worrying about chords or harmony, I'll just try matching Dionne's vocal lines, note for note.I began to really learn about soloing and respecting the song and the melody. I think too many guitar players forget that and get stuck in the guitar itself, playing lots of notes—"noodling," I call it. It's like they're playing too fast to pay attention. Some people thrive on that, but sooner or later the bird's got to land in the mist and you got to play the melody. Imagine if the song was a woman—what would she say? Did you forget me? Are you mad at me?I still hear what Miles Davis used to say about musicians who play too much: "You know, the less you play the more you get paid for each note."

Published on July 19, 2019 10:55

July 14, 2019

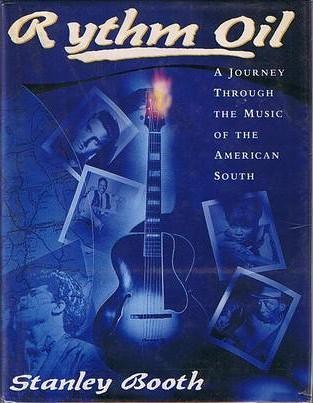

Now Reading: Rythm Oil by Stanley Booth

Stanley Booth is a writer, a researcher, a journalist, a chronicler of an era of music...Each of the chapters in this book were previously published in various magazines, including Esquire, Saturday Evening Post, Playboy, Rolling Stone, Atlantic Weekly, and the Village Voice, to name a few. One chapter on Elvis Presley, however, contains an opening paragraph that was not safe for publication in Esquire back in 1976, and thus held back from the original article (and probably wouldn't be safe for publication today, either).

Stanley Booth is a writer, a researcher, a journalist, a chronicler of an era of music...Each of the chapters in this book were previously published in various magazines, including Esquire, Saturday Evening Post, Playboy, Rolling Stone, Atlantic Weekly, and the Village Voice, to name a few. One chapter on Elvis Presley, however, contains an opening paragraph that was not safe for publication in Esquire back in 1976, and thus held back from the original article (and probably wouldn't be safe for publication today, either).Rythm Oil is subtitled "A Journey Through the Music of the American South": In addition to Elvis, there are chapters on old bluesmen Furry Lewis and Mississippi John Hurt, Otis Redding, Rufus Thomas and daughter Carla Thomas, The Flying Burrito Brothers, the Janis Joplin Revue, and more (I haven't finished the book yet!).

"What became Stax records began in 1958 with a one-track tape recorder owned by a white brother and sister, Jim Stewart and Estelle Axton [1], and located in Brunswick, Tennessee, behind the Satellite Dairy, a take-out ice-cream parlor. Estelle was a grammar-school teacher and Jim was a bank teller and a country fiddle player. They had little knowledge of what they were getting into, but they had incredible luck. For one example, Estelle's son Packy rehearsed on weekends at the Dairy with the Royal Spades, a rhythm and blues band of white Messick High School students that would develop into the Mar-Keys, the Stax house band. For another, in 1960 they found an empty movie theater that rented for $100 a month – the Capitol at 926 East McLemore – in a black South Memphis neighborhood. And Rufus Thomas brought the first hit to Stax. Thomas, who had started out on Beale Street at the age of six playing a frog in a show at the Grand Theater, had been a Rabbit's Foot Minstrel, MC at the Midnight Rambles, half the dance team of Rufus and Bones, a local radio announcer, and the first person to have a hit on the Sun label, 'Cause I Love You,' a regional sensation sung by Rufus and his daughter Carla, was followed by the first national hit on Stax – 'Gee Whiz' – a solo by Carla, who had written it when she was about fifteen....

In October of 1962 Stax released its first Otis Redding record, made in half an hour at the end of a Johnny Jenkins session....

There was a feeling in the air that summer [1967] – the summer of Monterey, of Sergeant Pepper, of LSD – that people were coming together, red and yellow, black and white, in peace and love.

In December Otis Redding would record 'Dock of the Bay.' None of us knew what was coming.[2]

In the wake of Martin Luther King's death, the climate for an integrated business in a black neighborhood changed, even on East McLemore Avenue. The front door of Stax, which had always been left open – Carl Cunningham, the Bar-Kays' drummer, had come in one day with a shoeshine kit and stayed to become a musician – was locked. Then one day it was locked for good. Today Stax is a crumbling shell. It was as if Stax had such good luck in the beginning that when at the end the bad luck came it was annihilating."— Stanley Booth

Rythm Oil was published in 1991 by Pantheon Books. The hardcover edition is out of print, but the book is readily available in trade paperback from Amazon[image error] or your bookseller of choice.

---------------

Footnotes

[1] Stax is an acronym formed from the first two letters of Jim Stewart's and Estelle Axton's last names.

[2] Otis Redding died in a plane crash on December 10, 1967, along with the five teenage members of his backing band, the Bar-Kays.

Published on July 14, 2019 14:22