Marty Halpern's Blog, page 44

August 25, 2011

Alien Contact Anthology -- Story #17

For details on the previous sixteen stories, including the complete text for five of them (so far), please begin here.

"To Go Boldly"

by Cory Doctorow

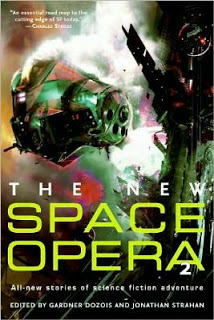

This story was originally published in The New Space Opera 2, edited by Gardner Dozois and Jonathan Strahan (HarperCollins/EOS, 2009), and is approximately 7,000 words in length. [Note, too, that the author did not split the infinitive in the story title! Kudos, Cory!]

This story was originally published in The New Space Opera 2, edited by Gardner Dozois and Jonathan Strahan (HarperCollins/EOS, 2009), and is approximately 7,000 words in length. [Note, too, that the author did not split the infinitive in the story title! Kudos, Cory!]

I first emailed Cory Doctorow toward the end of August 2008 about including a story of his in this anthology. The only alien contact story of his that I was familiar with at the time was "Craphound." When Cory responded, he informed me that he had just completed a draft of a new story, "To Go Boldly," which he attached to the email, that would be included in a forthcoming Dozois and Strahan anthology. One caveat: the book was scheduled for publication in July 2009, and the story could not be reprinted for six months. So I would be clear to use the story beginning in 2010. I told Cory that shouldn't be a problem, that it would probably be at least a year before my anthology was published. Well, here we are, three years later from that original email communication! Though, to be honest, I've already received a copy of the Alien Contact Advance Uncorrected Proof, and I hope to be showcasing the final cover art here "real soon now" -- seriously. And, of course, the anthology is still on schedule (as far as I know) for a November publication.

After reading only a few pages, I realized that "To Go Boldly" was a contemporary reboot (actually, I hate that term but what else is there?) of the "Arena" episode of Star Trek: The Original Series. The two main characters are Captain Reynold J. Tsubishi, commander of the APP ship Colossus II, and his B-string [second shift] commander, First Lieutenant !Mota, a member of the non-human race Wobblie -- "not a flattering name for an entire advanced starfaring race, but an accurate one, and no one with humanoid mouth-parts could pronounce the word in Wobbliese." Here is the scene in which the crew first encounters their adversary:

I asked Cory for some thoughts regarding his story, and here's what he wrote -- which quite surprised me:

I was expecting Cory to write something about the sardonic nature of his story, or its camaraderie with Star Trek's "Arena," but instead we get some strong words on the two cheats, or "miracles," to use Cory's word, in SF: FTL travel and transporters. But, getting back to the story and the yufo's use of the word "role-players," it appears the yufo thinks this is all a game anyhow. One more thing: this story is also an interesting exercise in the use of non-gender pronouns: "ze" and "zer."

One more excerpt from the story:

Cory releases most, if not all, of his work free online via Creative Commons licenses, and "To Go Boldly" is no exception. If you are a podcast junkie, or you would simply like to sit back, relax, and listen to this one particular story, StarShipSofa has the story available as part of their podcast program "Aural Delights No 110," which was released on November 25, 2009.

[Continue to Story #18]

"To Go Boldly"

by Cory Doctorow

This story was originally published in The New Space Opera 2, edited by Gardner Dozois and Jonathan Strahan (HarperCollins/EOS, 2009), and is approximately 7,000 words in length. [Note, too, that the author did not split the infinitive in the story title! Kudos, Cory!]

This story was originally published in The New Space Opera 2, edited by Gardner Dozois and Jonathan Strahan (HarperCollins/EOS, 2009), and is approximately 7,000 words in length. [Note, too, that the author did not split the infinitive in the story title! Kudos, Cory!] I first emailed Cory Doctorow toward the end of August 2008 about including a story of his in this anthology. The only alien contact story of his that I was familiar with at the time was "Craphound." When Cory responded, he informed me that he had just completed a draft of a new story, "To Go Boldly," which he attached to the email, that would be included in a forthcoming Dozois and Strahan anthology. One caveat: the book was scheduled for publication in July 2009, and the story could not be reprinted for six months. So I would be clear to use the story beginning in 2010. I told Cory that shouldn't be a problem, that it would probably be at least a year before my anthology was published. Well, here we are, three years later from that original email communication! Though, to be honest, I've already received a copy of the Alien Contact Advance Uncorrected Proof, and I hope to be showcasing the final cover art here "real soon now" -- seriously. And, of course, the anthology is still on schedule (as far as I know) for a November publication.

After reading only a few pages, I realized that "To Go Boldly" was a contemporary reboot (actually, I hate that term but what else is there?) of the "Arena" episode of Star Trek: The Original Series. The two main characters are Captain Reynold J. Tsubishi, commander of the APP ship Colossus II, and his B-string [second shift] commander, First Lieutenant !Mota, a member of the non-human race Wobblie -- "not a flattering name for an entire advanced starfaring race, but an accurate one, and no one with humanoid mouth-parts could pronounce the word in Wobbliese." Here is the scene in which the crew first encounters their adversary:

"Hail the yufo, Ms. De Fuca-Williamson."

The comms officer's hands moved over her panels, then she nodded back at Tsubishi.

"This is Captain Reynold J. Tsubishi of the Alliance of Peaceful Planets ship Colossus II. In the name of the Alliance and its forty-two member-species, I offer you greetings in the spirit of galactic cooperation and peace." It was canned, that line, but he'd practiced it in the holo in his quarters so that he could sell it fresh every time.

The silence stretched. A soft chime marked an incoming message. A succession of progress bars filled the holotank as it was decoded, demuxed and remuxed. Another, more emphatic chime.

"Do it," Tsubishi said to the comms officer, and First Contact was made anew.

The form that filled the tank was recognizably a head. It was wreathed in writhing tentacles, each tipped with organs that the computer identified with high confidence as sensory—visual, olfactory, temperature.

The tentacles whipped around as the bladder at the thing's throat inflated, then blatted out something in its own language, which made Wobbliese seem mellifluous. The computer translated: "Oh, for god's sake—role-players? You've got to be kidding me."

I asked Cory for some thoughts regarding his story, and here's what he wrote -- which quite surprised me:

I've always been frustrated by the lack of economic coherence in stories about interstellar empires, especially those who get TWO miracles: FTL travel and transporter beams (which are really matter assembler/disassemblers). At that point, you can go anywhere and make anything, so why would you refight any of the old colonial/conquest games? Not to say that there mightn't be some game to be played, but colonies and conquest are firmly grounded in the notion of strategic location and control of resources. All locations are approximately equivalent in an FTL universe and as to resources, they get a lot less urgent when you can instantiate any molecule on demand, using only (free) energy.

These stories are indictments of their authors and their fans -- they are embodiments of the science fictional premise that "all rules are local" and "no rule knows how local it is." To assume that an FTL/transporter universe would give rise to these old games is to assume a universality of greed, conquest and xenophobia -- that is, to project your own values on the universe and everyone who might someday inhabit it.

I was expecting Cory to write something about the sardonic nature of his story, or its camaraderie with Star Trek's "Arena," but instead we get some strong words on the two cheats, or "miracles," to use Cory's word, in SF: FTL travel and transporters. But, getting back to the story and the yufo's use of the word "role-players," it appears the yufo thinks this is all a game anyhow. One more thing: this story is also an interesting exercise in the use of non-gender pronouns: "ze" and "zer."

One more excerpt from the story:

"A warning shot, Lieutenant," he said, tipping his head to Deng-Gorinski. "Miss the yufo by, say, half a million klicks."

The click of Deng-Gorinski's talon was the only sound on the bridge, as every crewmember held zer breath, and then the barely detectable hap-tic whom as a torpedo left its bay and streaked off in glorious 3-D on the holotank, trailed by a psychedelic glitter of labels indicating its approach, operational status, detected countermeasures, and all the glorious, pointless instrumentation data that was merely icing on the cake.

The torpedo closed on the yufo, drawing closer, closer…closer. Then—

Blink

"It's gone, sir." Deng-Gorinski's talons clicked, clicked. "Transporter beam. Picked it right out of the sky."

That's impossible. He didn't bother to say it. Of course it was possible: they'd just seen it happen. But transporting a photon torpedo that was underway and emitting its punishing halo of quantum chaff should have required enough energy to melt a star and enough compute-power to calculate the universe. It was the space-naval equivalent of catching a sword-blade between your palms as it was arcing toward your chest.

Cory releases most, if not all, of his work free online via Creative Commons licenses, and "To Go Boldly" is no exception. If you are a podcast junkie, or you would simply like to sit back, relax, and listen to this one particular story, StarShipSofa has the story available as part of their podcast program "Aural Delights No 110," which was released on November 25, 2009.

[Continue to Story #18]

Published on August 25, 2011 17:16

August 21, 2011

The Pen Is Mightier...

I credit my friend, the author Bruce McAllister, with helping me to name this blog More Red Ink. Of course, the idea indirectly came from Jeffrey Ford, when he included the Moses/God quote (you can read it in the right column, below the Blog Archive) in the acknowledgments to his first short fiction collection, The Fantasy Writer's Assistant and Other Stories, which I acquired and edited for Golden Gryphon Press (2002).

Bottom line, if you ever receive a marked up, edited manuscript from me, odds are pretty good that it will have its share of red ink. I've had some manuscripts in years past with so much red that it looked like I had bled all over the pages (i.e. I became so frustrated with the manuscript that I tried to commit suicide).

Seriously, I just wanted to give credit to my red pen of choice: the Pilot G2 Gel Ink Rolling Ball Fine Point. It doesn't get any better than that! My wife came home the other day from shopping and set down a package of the pens in front of me. She said they were on sale. I looked at this as her way of telling me that I should, well, work harder.

Bottom line, if you ever receive a marked up, edited manuscript from me, odds are pretty good that it will have its share of red ink. I've had some manuscripts in years past with so much red that it looked like I had bled all over the pages (i.e. I became so frustrated with the manuscript that I tried to commit suicide).

Seriously, I just wanted to give credit to my red pen of choice: the Pilot G2 Gel Ink Rolling Ball Fine Point. It doesn't get any better than that! My wife came home the other day from shopping and set down a package of the pens in front of me. She said they were on sale. I looked at this as her way of telling me that I should, well, work harder.

Published on August 21, 2011 19:52

August 19, 2011

"Texture of Other Ways" by Mark W. Tiedemann (Part 3 of 3)

Texture of Other Waysby Mark W. Tiedemann

[Continued from Part 2]

The oval-shaped room contained several comfortable chairs, three or four recorders, and a commlink panel. A curious flower-shaped mass on the ceiling apparently provided the unique environments for the species present.

The two people assigned to my group shook our hands quickly, smiling anxiously. We resisted the urge to telelog them to see why they were so nervous. Merril told us we had to trust them and do nothing to damage that trust.

The light dimmed when our counterparts entered. Our group had been assigned the Cursians. They were bulky, almost humanoid types. Their torsos began where knees should have been and their limbs looked like dense extrusions of rope. Individual tendrils would separate to perform the articulations of fingers, but they constantly touched themselves with them. No eyes that we could discern, but a thick mass of lighter tissue gathered in the center of the bumpy mass we thought of as its head. They wore threads of metal draped in complex patterns over their dense torsos. We were told that they breathed a compound of CO2, CH3, and CH5N. The air seemed to glow a faint green on their side of the room.

"We need to touch them," I said.

"That's not possible," one of the linguists said, frowning. "I mean…" She looked at her colleague. "Is it?"

"I don't think so," he said, and went to the comm. He spoke with someone for a few minutes, then turned back to us, shaking his head. "Not advised. There could be some leakage of atmospheres. Cyanide and oxygen are mutually incompatible. We don't know how dangerous it might be."

"Then we can't do this. We have to touch them."

"Shit," she said. "Why didn't anybody see this problem?"

He shrugged and returned to the comm.

We spent the rest of that day's session staring across the thin line of atmosphere at each other. I wondered if the Cursians were as disappointed as we.

* * *

The next day there was no session. Everyone had experienced a similar problem with their seti groups. In one case it was incompatible atmospheres, in another it was a question of microbe contaminants, in another it was just a matter of propriety. The sessions were canceled until some way of getting across the notion could be devised.

Before we could touch and share our logos, Admiral Kovesh ordered us separated.

"Once they make contact," she said, "this is how it will be. May as well start them now so they get used to it."

Merril protested, but we ended up in separate rooms anyway. The three of us huddled close together all through the night.

Admiral Kovesh came twice to wake us up and ask if we had sensed nothing, if perhaps we had picked up something after all, but we could only explain, as before, that to telelog it was necessary to touch, or the biopole could not be transferred—

She didn't want to hear that. The second time I told her that and she grew suspicious.

"Are you reading me?" she asked.

"Would you believe me if I said no?"

She did not come back that night.

* * *

Three days later we once more went to the meeting room. Now there was a solid transparent wall between the Cursians and us with a boxlike contraption about shoulder height that contained complex seals joining in its middle in a kind of mixing chamber. It was obvious that an arrangement had been made.

"How does it work?"

"As simple as putting on a glove," one of the liaisons said. "Just insert your hand here, shove it through until you feel the baffles close on your arm. Self-sealing. The touchpoint chamber will only allow one finger through. Is that enough?"

It was annoying and confusing that no one had asked us. But perhaps Merril had told them. In any event, yes, we told them, it was enough.

On the other side of the clear wall, one of the Cursians came forward. A limb jammed into its end of the box and a tendril separated and pushed through until a tip emerged into the central chamber. I looked at the other two, who touched my free hand and nodded. I put my hand into the box.

My finger poked through the last seal and the membrane closed firmly just below the second joint. The air in the chamber was cold and my skin prickled. I stared at the Cursian "finger" as it wriggled slowly toward the tip of my finger. I concentrated a biopole discharge there and when it touched me it was almost as if I could feel the colony surge from me to the Cursian. Imagination, certainly, I had never been able to "feel" the transfer; the only way any of us ever knew it had happened was when the colony established itself and began sending back signals.

There should have been a short signal, a kind of handshake that let us know it had been a successful transfer. I waited, but felt no such impulse.

I gazed through the layers of separation between us and wondered if it was feeling the same sense of failure. To come all this way, to prepare all your life for this moment, and then to find that for reasons overlooked or unimagined you have been made for nothing…I thought then that there could be no worse pain.

I was wrong.

* * *

Once an animal was released among us. A dog. I don't know if it had been intentional or an accident. You might be surprised at how many accidents happen in a highly monitored, overly secured lab. It seems sometimes that the more tightly controlled an environment is the more the unexpected happens. But in this case, I'm inclined to believe it was intentional, despite the reactions of our caretakers—especially Merril—when they discovered it.

The animal was obviously frightened. It didn't know where it was, or who we were. We thought perhaps that it was a seti, that maybe one had volunteered to come to us as a test, but that was quickly rejected when we accessed the library. The dog was only a pet, an assistant, a symbiote that had accompanied Homo sapiens sapiens on the long journey to the present. It whimpered a little when we cornered it and looked at us with hopeful, nearly trusting eyes. It needed assurance. It needed to know that it was welcome, that we would not harm it. We only intended to give it what it wanted.

The brief immersion in its thoughts came as a shock. The sheer terror it exuded surprised us, overwhelmed our own sense of security. When they took it away to be "put down," as Merril called it, several of us still wept uncontrollably from the aftershocks.

Batteries of tests followed to make sure no damage had been done. But the dog was dead.

* * *

It came gradually, a vaguely puzzled sensation, a What, where from, who? series of impressions. For a moment I nearly lost my despair.

Then a wave of nauseating rage washed through me. Revulsion, anger, rejection—like a massive hand trying to push me away. But I was chained to it and the more it pushed the more pain came through the connection. Sparks danced in my eyes. My skull felt ready to split and fall open. When I opened my eyes, I saw that I had slid to the floor, my hand still shoved through the trap.

The Cursian rocked back and forth and side to side, serpentine digits writhing. Suddenly, it reared back and drove one of its limbs at the transparency. The impact shook the wall.

I heard swearing around me, terse words, orders, but none of it made sense. My language was gone. Words were only sound. In my head I knew only a vast and sour presence and I remembered the dog and its terror and I tried to stand, to pull my hand away.

I thought I had failed before. Now I knew what failure felt like. But it wasn't my failure.

Hands grasped my shoulders, another took my arm. I was pulled away. My hand came free, but it felt cold and numb. I stared at the seti. It extracted its own limb and stumbled away from the transparency and nearly collapsed on the floor. It looked tormented.

"D-don—don't—!" I tried to say, but my siblings were holding me and the biopole bled into them.

One screamed. The other jerked away, mouth open.

"Get them out of here!" someone shouted. "Now!"

More people crowded into the chamber and I was lifted onto a gurney. I couldn't stop feeling the awful violation the Cursian had emptied into me. I wanted to sleep. I wanted to die.

* * *

It happened to all of us. It grew worse as we came together.

Logos spread back and forth, colonizing and broadcasting. We didn't understand and that complicated it. We sought comfort from each other, but the enigma of alien rejection compounded, interfered.

It didn't end till we were sedated.

And then there were dreams…dreams of anxiety and suspicion and insult…dreams of dying…

* * *

They showed us vids later. I don't like watching them, but they make us see them, those of us who lived. The setis reacted. It's obvious now, after the fact. They recoiled. That's the only word I can think that fits. Recoiled. Some of them looked dead. Five of us died. Others wouldn't stop screaming.

There are images in my head and I'm frightened to share them. I look at my companions and can see that they, too, contain things they will not, cannot share. It hurts. I understand Admiral Kovesh's reaction to the logos. Nobody told us it might be like this. Perhaps we should have suspected because of the dog, but we had all dismissed that because it had been so disadvantaged compared to us, its mind couldn't comprehend what was happening. But we know now. It was so simple an oversight—or perhaps not, perhaps it was assumed to be impossible, part of the dilemma of the situation: How can you ask permission when you don't speak the language? That was, after all, our task—to ask them things. But no one had tried to tell them that we would invade their minds in order to do so. And when we did, they scarred us.

We can never live in each other's minds again. We are separate now because we fear each other. We fear what we contain. We fear what we might give ourselves. We do not understand.

The seti ships had moved into positions of defense by the time the marines got us back up to our ship. They were frightened. We had hurt them. They had hurt us. We will all of us have to learn a new way to trust.

Perhaps, I think, we fulfilled our mission anyway. We had believed we shared nothing with the seti, but that's wrong. We share fear. Humans have been basing relations on that for millennia.

A door opens and a marine comes in. She switches off the vid and pulls out a notepad.

"Admiral Kovesh says we have to see to it you get whatever you want," she says. She smiles at me and I'm startled at how pleased I am. "What's your name?" she asks.

I feel my smile fade.

"Name?"

[The End]

[Continue to Story #17]

---------------

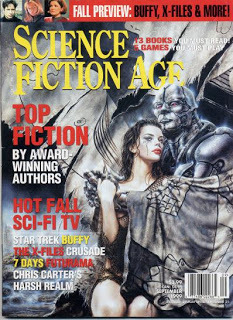

"Texture of Other Ways" is © 1999 by Mark W. Tiedemann and is reprinted here with permission of the author. The story was originally published in Science Fiction Age, September 1999.

"Texture of Other Ways" is one of 26 stories included in anthology Alien Contact, edited by Marty Halpern and forthcoming from Night Shade Books in November. For more information on this anthology, please start here.

Mark W. Tiedemann attended Clarion in 1988, and has sold over fifty short stories, to Asimov's, Fantasy & Science Fiction, Science Fiction Age, Tomorrow SF, Tales of the Unanticipated, and anthologies such as Universe 2, Vanishing Acts, Bending the Landscape, War of the Worlds: the Global Dispatches, and others.

In 2001 the first book of his Secantis Sequence was published: Compass Reach was a finalist for the Philip K. Dick Award. Two more novels followed: Metal of Night and Peace & Memory. In 2006, his standalone novel Remains was shortlisted for the James Tiptree Jr. Award.

While all this was going on, he joined the board of directors of the Missouri Center for the Book, the Missouri affiliate to the Library of Congress Center for the Book, an institution that works to promote and support the state literary heritage and the culture of the book. In 2005, he was elected its president. Though retired now, during his tenure, the Center advocated for and achieved the establishment of the first Missouri State Poet Laureate.

Mark has lived in St. Louis all his life, for the past thirty years with his companion, best friend, and first reader, Donna. He occasionally plays piano and guitar, doodles in idle moments, and is somehow, according to friends, still sane after all these years, a condition which could change at any moment.

[Continued from Part 2]

The oval-shaped room contained several comfortable chairs, three or four recorders, and a commlink panel. A curious flower-shaped mass on the ceiling apparently provided the unique environments for the species present.

The two people assigned to my group shook our hands quickly, smiling anxiously. We resisted the urge to telelog them to see why they were so nervous. Merril told us we had to trust them and do nothing to damage that trust.

The light dimmed when our counterparts entered. Our group had been assigned the Cursians. They were bulky, almost humanoid types. Their torsos began where knees should have been and their limbs looked like dense extrusions of rope. Individual tendrils would separate to perform the articulations of fingers, but they constantly touched themselves with them. No eyes that we could discern, but a thick mass of lighter tissue gathered in the center of the bumpy mass we thought of as its head. They wore threads of metal draped in complex patterns over their dense torsos. We were told that they breathed a compound of CO2, CH3, and CH5N. The air seemed to glow a faint green on their side of the room.

"We need to touch them," I said.

"That's not possible," one of the linguists said, frowning. "I mean…" She looked at her colleague. "Is it?"

"I don't think so," he said, and went to the comm. He spoke with someone for a few minutes, then turned back to us, shaking his head. "Not advised. There could be some leakage of atmospheres. Cyanide and oxygen are mutually incompatible. We don't know how dangerous it might be."

"Then we can't do this. We have to touch them."

"Shit," she said. "Why didn't anybody see this problem?"

He shrugged and returned to the comm.

We spent the rest of that day's session staring across the thin line of atmosphere at each other. I wondered if the Cursians were as disappointed as we.

* * *

The next day there was no session. Everyone had experienced a similar problem with their seti groups. In one case it was incompatible atmospheres, in another it was a question of microbe contaminants, in another it was just a matter of propriety. The sessions were canceled until some way of getting across the notion could be devised.

Before we could touch and share our logos, Admiral Kovesh ordered us separated.

"Once they make contact," she said, "this is how it will be. May as well start them now so they get used to it."

Merril protested, but we ended up in separate rooms anyway. The three of us huddled close together all through the night.

Admiral Kovesh came twice to wake us up and ask if we had sensed nothing, if perhaps we had picked up something after all, but we could only explain, as before, that to telelog it was necessary to touch, or the biopole could not be transferred—

She didn't want to hear that. The second time I told her that and she grew suspicious.

"Are you reading me?" she asked.

"Would you believe me if I said no?"

She did not come back that night.

* * *

Three days later we once more went to the meeting room. Now there was a solid transparent wall between the Cursians and us with a boxlike contraption about shoulder height that contained complex seals joining in its middle in a kind of mixing chamber. It was obvious that an arrangement had been made.

"How does it work?"

"As simple as putting on a glove," one of the liaisons said. "Just insert your hand here, shove it through until you feel the baffles close on your arm. Self-sealing. The touchpoint chamber will only allow one finger through. Is that enough?"

It was annoying and confusing that no one had asked us. But perhaps Merril had told them. In any event, yes, we told them, it was enough.

On the other side of the clear wall, one of the Cursians came forward. A limb jammed into its end of the box and a tendril separated and pushed through until a tip emerged into the central chamber. I looked at the other two, who touched my free hand and nodded. I put my hand into the box.

My finger poked through the last seal and the membrane closed firmly just below the second joint. The air in the chamber was cold and my skin prickled. I stared at the Cursian "finger" as it wriggled slowly toward the tip of my finger. I concentrated a biopole discharge there and when it touched me it was almost as if I could feel the colony surge from me to the Cursian. Imagination, certainly, I had never been able to "feel" the transfer; the only way any of us ever knew it had happened was when the colony established itself and began sending back signals.

There should have been a short signal, a kind of handshake that let us know it had been a successful transfer. I waited, but felt no such impulse.

I gazed through the layers of separation between us and wondered if it was feeling the same sense of failure. To come all this way, to prepare all your life for this moment, and then to find that for reasons overlooked or unimagined you have been made for nothing…I thought then that there could be no worse pain.

I was wrong.

* * *

Once an animal was released among us. A dog. I don't know if it had been intentional or an accident. You might be surprised at how many accidents happen in a highly monitored, overly secured lab. It seems sometimes that the more tightly controlled an environment is the more the unexpected happens. But in this case, I'm inclined to believe it was intentional, despite the reactions of our caretakers—especially Merril—when they discovered it.

The animal was obviously frightened. It didn't know where it was, or who we were. We thought perhaps that it was a seti, that maybe one had volunteered to come to us as a test, but that was quickly rejected when we accessed the library. The dog was only a pet, an assistant, a symbiote that had accompanied Homo sapiens sapiens on the long journey to the present. It whimpered a little when we cornered it and looked at us with hopeful, nearly trusting eyes. It needed assurance. It needed to know that it was welcome, that we would not harm it. We only intended to give it what it wanted.

The brief immersion in its thoughts came as a shock. The sheer terror it exuded surprised us, overwhelmed our own sense of security. When they took it away to be "put down," as Merril called it, several of us still wept uncontrollably from the aftershocks.

Batteries of tests followed to make sure no damage had been done. But the dog was dead.

* * *

It came gradually, a vaguely puzzled sensation, a What, where from, who? series of impressions. For a moment I nearly lost my despair.

Then a wave of nauseating rage washed through me. Revulsion, anger, rejection—like a massive hand trying to push me away. But I was chained to it and the more it pushed the more pain came through the connection. Sparks danced in my eyes. My skull felt ready to split and fall open. When I opened my eyes, I saw that I had slid to the floor, my hand still shoved through the trap.

The Cursian rocked back and forth and side to side, serpentine digits writhing. Suddenly, it reared back and drove one of its limbs at the transparency. The impact shook the wall.

I heard swearing around me, terse words, orders, but none of it made sense. My language was gone. Words were only sound. In my head I knew only a vast and sour presence and I remembered the dog and its terror and I tried to stand, to pull my hand away.

I thought I had failed before. Now I knew what failure felt like. But it wasn't my failure.

Hands grasped my shoulders, another took my arm. I was pulled away. My hand came free, but it felt cold and numb. I stared at the seti. It extracted its own limb and stumbled away from the transparency and nearly collapsed on the floor. It looked tormented.

"D-don—don't—!" I tried to say, but my siblings were holding me and the biopole bled into them.

One screamed. The other jerked away, mouth open.

"Get them out of here!" someone shouted. "Now!"

More people crowded into the chamber and I was lifted onto a gurney. I couldn't stop feeling the awful violation the Cursian had emptied into me. I wanted to sleep. I wanted to die.

* * *

It happened to all of us. It grew worse as we came together.

Logos spread back and forth, colonizing and broadcasting. We didn't understand and that complicated it. We sought comfort from each other, but the enigma of alien rejection compounded, interfered.

It didn't end till we were sedated.

And then there were dreams…dreams of anxiety and suspicion and insult…dreams of dying…

* * *

They showed us vids later. I don't like watching them, but they make us see them, those of us who lived. The setis reacted. It's obvious now, after the fact. They recoiled. That's the only word I can think that fits. Recoiled. Some of them looked dead. Five of us died. Others wouldn't stop screaming.

There are images in my head and I'm frightened to share them. I look at my companions and can see that they, too, contain things they will not, cannot share. It hurts. I understand Admiral Kovesh's reaction to the logos. Nobody told us it might be like this. Perhaps we should have suspected because of the dog, but we had all dismissed that because it had been so disadvantaged compared to us, its mind couldn't comprehend what was happening. But we know now. It was so simple an oversight—or perhaps not, perhaps it was assumed to be impossible, part of the dilemma of the situation: How can you ask permission when you don't speak the language? That was, after all, our task—to ask them things. But no one had tried to tell them that we would invade their minds in order to do so. And when we did, they scarred us.

We can never live in each other's minds again. We are separate now because we fear each other. We fear what we contain. We fear what we might give ourselves. We do not understand.

The seti ships had moved into positions of defense by the time the marines got us back up to our ship. They were frightened. We had hurt them. They had hurt us. We will all of us have to learn a new way to trust.

Perhaps, I think, we fulfilled our mission anyway. We had believed we shared nothing with the seti, but that's wrong. We share fear. Humans have been basing relations on that for millennia.

A door opens and a marine comes in. She switches off the vid and pulls out a notepad.

"Admiral Kovesh says we have to see to it you get whatever you want," she says. She smiles at me and I'm startled at how pleased I am. "What's your name?" she asks.

I feel my smile fade.

"Name?"

[The End]

[Continue to Story #17]

---------------

"Texture of Other Ways" is © 1999 by Mark W. Tiedemann and is reprinted here with permission of the author. The story was originally published in Science Fiction Age, September 1999.

"Texture of Other Ways" is one of 26 stories included in anthology Alien Contact, edited by Marty Halpern and forthcoming from Night Shade Books in November. For more information on this anthology, please start here.

Mark W. Tiedemann attended Clarion in 1988, and has sold over fifty short stories, to Asimov's, Fantasy & Science Fiction, Science Fiction Age, Tomorrow SF, Tales of the Unanticipated, and anthologies such as Universe 2, Vanishing Acts, Bending the Landscape, War of the Worlds: the Global Dispatches, and others.

In 2001 the first book of his Secantis Sequence was published: Compass Reach was a finalist for the Philip K. Dick Award. Two more novels followed: Metal of Night and Peace & Memory. In 2006, his standalone novel Remains was shortlisted for the James Tiptree Jr. Award.

While all this was going on, he joined the board of directors of the Missouri Center for the Book, the Missouri affiliate to the Library of Congress Center for the Book, an institution that works to promote and support the state literary heritage and the culture of the book. In 2005, he was elected its president. Though retired now, during his tenure, the Center advocated for and achieved the establishment of the first Missouri State Poet Laureate.

Mark has lived in St. Louis all his life, for the past thirty years with his companion, best friend, and first reader, Donna. He occasionally plays piano and guitar, doodles in idle moments, and is somehow, according to friends, still sane after all these years, a condition which could change at any moment.

Published on August 19, 2011 15:15

August 17, 2011

"Texture of Other Ways" by Mark W. Tiedemann (Part 2 of 3)

Texture of Other Waysby Mark W. Tiedemann

[Continued from Part 1]

Admiral Kovesh came over to meet us after the convoy arrived at the orbital platform. She was a tall, straight-backed woman with deep creases in her face and very pale eyes. I thought she looked perfect for her command.

"As soon as our counterparts signal us," she explained, "then you'll all be taken down by shuttle. The Forum negotiators are already here."

"Can we see the other ships?" I asked.

Kovesh frowned. "What—?"

"The seti ships."

"Oh. Of course. As soon as I've briefed you on procedures."

"We've already been briefed."

Kovesh looked at Merril, who seemed nervous.

"Before we left Earth," he said, "we were all given a thorough profile of what to expect. They know their mission, Admiral."

"I don't care what they were told on Earth. We're thirteen parsecs out and this conference is under my aegis."

Merril gave us an apologetic look. "I see. Well, perhaps you could let them take it directly?"

"How do you mean?"

Merril blinked. "They're telelogs, Admiral. It would be quicker, surer—"

"Not on your life."

"I assure you it's painless, Admiral—"

"I'm assured. The answer is no. Now, if you don't mind…"

I felt sorry for Merril. He meant well, but I was glad the Admiral refused. Merril had an exaggerated notion of what we did. People are really a muddle.

The Change was mechanistic. We aren't psychics in the traditional sense. That's why we're called telelogs rather than telepaths. At infancy we were implanted with a biopole factory, a device called the logos. The logos transfers a colony of biopole, which seats itself in the recipient brain, and starts setting up a temporary pattern analyzer. Very quickly—I'm talking nanoseconds—the colony establishes a pattern, sets up a transmission, and within moments the contents of the mind are broadcast to the primary logos.

But the contents!

To be honest, it is much easier for someone to simply tell me, verbally, than for me to try to make sense of all this clutter!

We grew up living in each other's minds, we know how we operate, but the rest of humanity? It's a miracle there's any order at all.

Still, Admiral Kovesh's reaction disturbed me.

* * *

The idea made elegant sense.

Humans can't communicate with the seti, and vice versa. There is no mutual foundation of language between us. Even the couple of humanoid ones have languages grown from linguistic trees sprouted in different soils. Nothing matches up except for a few snatches of mathematics, which was how we all managed to pick one system in which to have a meeting.

That and the evident desire on the part of the seti to figure out how to communicate demands a solution.

There are only two solutions. The first will take decades, maybe centuries, and that will be the construction of an object by object lexicon. State a word—or group of words or collection of sound-signifiers, which will only be valid for those species that use sounds for communication—and point at the thing to which it attaches. How this will work with abstracts no one knows.

The other solution is us.

We smiled at each other, passed along encoded biopole of self-congratulation and mutual support, broadcast positive logos. Of course, we thought, what better way to decode a completely alien language than to read the minds of the speakers?

We learned linguistics and practiced decoding language on native speakers of disparate human tongues. With difficulty we learned to decode the patterns into recognizable linguistic components and eventually came to speak the language ourselves. Navajo, Mandarin, !Kung, Russian, Portuguese, English—the hard part was finding speakers of all these languages who were not also fluent in Langish, official Panspeak. But there are enclaves and preserves and the subjects were found and we learned.

The only troubling part—and none of us actually brought this up, but I imagine we all thought it—was that all these languages are ultimately human languages. All grown from the same soil. Hardwired. At some level, then, all the same.

* * *

Details. Kovesh went over them again and again. All we wanted to do was see a seti ship. Until we learned our lessons that would wait. We worked our way through to our reward, then stood before the viewer and gazed at the array of ships.

A small platform orbited the planet. Clouds smeared across a cracked grey-blue surface of alkalis and yttrian earths. The clouds, we learned, came from fine oxide powders blown through the lithium-fluorine atmosphere. We wondered how anything could oxidate in such an atmosphere and were told that a complex form of lichen lived underground and released oxygen through the soil. The surface constantly eroded under the breezes and picked up the deposits of oxidated metals once exposed.

The seti ships orbited close to the platform. As distinct as each appeared, all shared one common trait. They were all shells, protection, walls between life and death.

But what marvelous walls!

I had thought our ships were beautiful, and I still do, but compared to the array of alien ships they seem so…expected. Some of the vessels actually resembled ships. Certain shapes lend themselves to travel, to containing biospheres against hard vacuum, so inevitably globes, discs, tubes, and boxes of various sizes repeat from species to species. But the lines…

The nearest group looked like giant gourds, sectioned by sharp lines emanating from a central locus into seven equal parts. As we watched, though, a segment would drift away from the main body, float to another body, and change places with another segment.

Beyond these, we saw an enormous mass like dirty gelatin. Pieces extruded, broke off, drifted among the other groups, returned to merge with the whole. The entire surface roiled and bubbled.

Then there were the candyfloss yachts catching the sunlight and glimmering along the countless threads that interlaced to form their conic assemblies…

We passed impressions among ourselves, all of them optimistic. We were here to learn to speak with these beings who built these lovely ships. Because we marvelled at what they had built we knew we would marvel at who they were, at what they were. We were a short flight from the fulfillment of our life's purpose.

* * *

Marines escorted us to our shuttles. The wide corridors of the ship suddenly felt tight. We stayed close together, hands touching, and said nothing. Even through the logos all we shared were vague assurances, the soldiers' stiff presence acting like a muffle on our enthusiasm.

Kovesh waited in the lead shuttle.

"A platoon is waiting on the surface," she said. "Each group will go down with an escort of three. I'll ride this one down. All the shuttles will maintain standby once we're down, so should anything arise we'll be able to get you off quickly."

Eleven of us in each group. I missed Merril. He rode down with a different shuttle. We sat in couches that faced across a narrow walkway from each other. One marine sat forward, the other aft, while Kovesh went up by the pilot.

There was no view outside. We held hands and looked across at ourselves and tried to imagine what happened from sounds and vibrations. We knew the moment the shuttle left the ship, we had all felt that characteristic sensation before. Then the soundless time of freefall…then the first brush of atmosphere…the shuttle bounced and we could hear a high-pitched whine through the bulkheads. An air leak? That meant a breach…but no alarms flashed, except the fear transmitted back and forth through our hands, building quickly to near panic until Kovesh came back and told us we would land in five minutes. The panic subsided like water sloshing back and forth until it loses momentum and finds equilibrium.

But our equilibrium now rested on a thin layer of anxiety.

A series of harsher sounds and heavier shocks followed. I squeezed the hands I held tight and they gripped me harder till my fingers began to go numb, till everyone's fingers tingled, and passed the sensation back and forth.

Then silence.

Kovesh stepped down the walkway between us. A few seconds later the hatch opened with a loud pneumatic hiss.

We waited. I imagined us as cargo, the marines our deliverers, and passed the thought along. A few smiles came back and we relaxed a little.

"All right," Kovesh snapped, leaning into the shuttle. "Stay close. The other shuttles are down now. You'll be taken to your temporary quarters."

Umbilicals attached the shuttle locks to the environ module. We stepped into a wide chamber, the support ribs naked against the walls and ceiling, the air chilled so that we could see our breath. We came together immediately, all thirty-three of us, in the center of the chamber, reestablishing contact as if we had been separated for days or years. Merril walked around our perimeter saying over and over that everything was all right, everything was fine.

I looked back to the locks then and saw marines standing at each. I searched the chamber for Admiral Kovesh and found her speaking to two men at the opposite end of the module. More marines flanked them. Then I noticed that marines stood against the walls all around us.

Merril continued his orbit, his reassurances, until Kovesh summoned him.

* * *

After the Change we laughed and cried together. Pain and pleasure became a shared thing, what one experienced cascaded through all of us. For a time there was concern that we would fail to individuate. It became necessary to shut us down from time to time, force us to form independent identities. It was a lot like learning to walk, then run, then walk and run in self-directed patterns, then integrate it all into an automatic decision-making hierarchy that worked without constant conscious monitoring. You don't think your way across a room, down a street, over a hill, or through a city, you just go in response to an abstract desire to go somewhere.

Eventually we developed individual traits, some degree of autonomy, but it never felt natural. Forced separation always hurt. Short periods of apartness were tolerable only because we knew we would be together again. Soon.

* * *

The meeting hall stood in the middle of a sodium-white field, gothic in proportion, elegant, delicate, emblematic. Its machinery encapsulated each group in an appropriate atmosphere, clearly seti tech. The marines had told us about it. They were disturbed, a bit awed.

"This is a formal occasion," Merril told us, "an introduction. You won't be doing anything here. We're just meeting the representatives."

We entered the central hall. Sounds echoed oddly, bouncing as it did through mixed gases. It felt as if we were immersed in an invisible sea.

The setis stood arrayed around the perimeter, formed up in loose groups, some of which contained more than one species. Some were bipeds, others without visible limbs, a few with no discernible "heads," and one that seemed nothing but a tangle of articulating limbs. The fields in which they stood refracted light differently. When they moved and the fields overlapped, colors warped out of true, bent, and dazzled.

We spread out. Their designated speakers separated from their parties and approached the center. The light was coppery, liquid. Pride welled up within us. We had trained for this, been created for this, designed for this.

Sound washed through the hall. Bass, treble, mixes of tone that verged on music, then slid away into barely ordered chaos…they spoke! We touched hands, passed our impressions down the line, always with the underthought that this is what we had come to solve.

The human delegates stood up, then, and read from a prepared statement. We heard little of it. The setis held our attention. This was all politics, this meeting. A show. It was being recorded, we knew, and would be used later, excellent press. The real work would be done under less dramatic circumstances. But this alone seemed worth the journey. If we could freeze the moment like this…it was perfect, just as it was. Uncomplicated by articulation.

We gazed across the hall at each other. I felt nothing at that instant but anticipation.

* * *

Of course it made perfect sense. We couldn't do what was required all bunched together in a group, mingled with all the seti at once. The cascade of impressions would ruin the uniqueness of each language. We had to isolate each seti and work on its language apart from the rest. Perfectly reasonable.

"There are five major groups," Ambassador Sulin explained. "Rahalen, Cursian, Vohec, Menkan, and Distanti. There are numerous other allied and nonaligned races, some of them present, but from what we've been able to determine, these five are the primary language groups. Translate these and we can communicate with most of the others."

He cleared his throat and glanced at Merril. "I didn't expect them to be so young," he said.

"It was in the précis we sent," Merril said, frowning.

"Yes, but…well." He shrugged and looked at us. "Each team will contain five people. Two linguists and three of you. We're not sure how many individuals will attend each seti representative, but the work rooms aren't that large, so we don't expect much more on their part. Now, what we want is for you to choose a back-up group among yourselves for each language. When you come out of a session, you go immediately to that group and work over what you've, uh, learned. Don't cross-reference with the other groups, please, not until we've got some kind of handle on each language."

"The setis communicate among themselves, don't they?" I asked.

"Yes, as far as we know."

"Then they already have a common set of referents. Wouldn't it be sensible to try to find that first?"

"Good question. But what we want is to have some basis of understanding for each group individually first. Then we can go on from there."

"But—"

"This is the procedure we will use."

"Uh," Merril said, "Ambassador, it's just that the idea of separation is unpleasant for them."

"Then they'll have to get used to it."

* * *

[Continue to Part 3]

---------------

"Texture of Other Ways" is © 1999 by Mark W. Tiedemann and is reprinted here with permission of the author. The story was originally published in Science Fiction Age, September 1999, and will be included in anthology Alien Contact, edited by Marty Halpern and forthcoming from Night Shade Books in November.

[Continued from Part 1]

Admiral Kovesh came over to meet us after the convoy arrived at the orbital platform. She was a tall, straight-backed woman with deep creases in her face and very pale eyes. I thought she looked perfect for her command.

"As soon as our counterparts signal us," she explained, "then you'll all be taken down by shuttle. The Forum negotiators are already here."

"Can we see the other ships?" I asked.

Kovesh frowned. "What—?"

"The seti ships."

"Oh. Of course. As soon as I've briefed you on procedures."

"We've already been briefed."

Kovesh looked at Merril, who seemed nervous.

"Before we left Earth," he said, "we were all given a thorough profile of what to expect. They know their mission, Admiral."

"I don't care what they were told on Earth. We're thirteen parsecs out and this conference is under my aegis."

Merril gave us an apologetic look. "I see. Well, perhaps you could let them take it directly?"

"How do you mean?"

Merril blinked. "They're telelogs, Admiral. It would be quicker, surer—"

"Not on your life."

"I assure you it's painless, Admiral—"

"I'm assured. The answer is no. Now, if you don't mind…"

I felt sorry for Merril. He meant well, but I was glad the Admiral refused. Merril had an exaggerated notion of what we did. People are really a muddle.

The Change was mechanistic. We aren't psychics in the traditional sense. That's why we're called telelogs rather than telepaths. At infancy we were implanted with a biopole factory, a device called the logos. The logos transfers a colony of biopole, which seats itself in the recipient brain, and starts setting up a temporary pattern analyzer. Very quickly—I'm talking nanoseconds—the colony establishes a pattern, sets up a transmission, and within moments the contents of the mind are broadcast to the primary logos.

But the contents!

To be honest, it is much easier for someone to simply tell me, verbally, than for me to try to make sense of all this clutter!

We grew up living in each other's minds, we know how we operate, but the rest of humanity? It's a miracle there's any order at all.

Still, Admiral Kovesh's reaction disturbed me.

* * *

The idea made elegant sense.

Humans can't communicate with the seti, and vice versa. There is no mutual foundation of language between us. Even the couple of humanoid ones have languages grown from linguistic trees sprouted in different soils. Nothing matches up except for a few snatches of mathematics, which was how we all managed to pick one system in which to have a meeting.

That and the evident desire on the part of the seti to figure out how to communicate demands a solution.

There are only two solutions. The first will take decades, maybe centuries, and that will be the construction of an object by object lexicon. State a word—or group of words or collection of sound-signifiers, which will only be valid for those species that use sounds for communication—and point at the thing to which it attaches. How this will work with abstracts no one knows.

The other solution is us.

We smiled at each other, passed along encoded biopole of self-congratulation and mutual support, broadcast positive logos. Of course, we thought, what better way to decode a completely alien language than to read the minds of the speakers?

We learned linguistics and practiced decoding language on native speakers of disparate human tongues. With difficulty we learned to decode the patterns into recognizable linguistic components and eventually came to speak the language ourselves. Navajo, Mandarin, !Kung, Russian, Portuguese, English—the hard part was finding speakers of all these languages who were not also fluent in Langish, official Panspeak. But there are enclaves and preserves and the subjects were found and we learned.

The only troubling part—and none of us actually brought this up, but I imagine we all thought it—was that all these languages are ultimately human languages. All grown from the same soil. Hardwired. At some level, then, all the same.

* * *

Details. Kovesh went over them again and again. All we wanted to do was see a seti ship. Until we learned our lessons that would wait. We worked our way through to our reward, then stood before the viewer and gazed at the array of ships.

A small platform orbited the planet. Clouds smeared across a cracked grey-blue surface of alkalis and yttrian earths. The clouds, we learned, came from fine oxide powders blown through the lithium-fluorine atmosphere. We wondered how anything could oxidate in such an atmosphere and were told that a complex form of lichen lived underground and released oxygen through the soil. The surface constantly eroded under the breezes and picked up the deposits of oxidated metals once exposed.

The seti ships orbited close to the platform. As distinct as each appeared, all shared one common trait. They were all shells, protection, walls between life and death.

But what marvelous walls!

I had thought our ships were beautiful, and I still do, but compared to the array of alien ships they seem so…expected. Some of the vessels actually resembled ships. Certain shapes lend themselves to travel, to containing biospheres against hard vacuum, so inevitably globes, discs, tubes, and boxes of various sizes repeat from species to species. But the lines…

The nearest group looked like giant gourds, sectioned by sharp lines emanating from a central locus into seven equal parts. As we watched, though, a segment would drift away from the main body, float to another body, and change places with another segment.

Beyond these, we saw an enormous mass like dirty gelatin. Pieces extruded, broke off, drifted among the other groups, returned to merge with the whole. The entire surface roiled and bubbled.

Then there were the candyfloss yachts catching the sunlight and glimmering along the countless threads that interlaced to form their conic assemblies…

We passed impressions among ourselves, all of them optimistic. We were here to learn to speak with these beings who built these lovely ships. Because we marvelled at what they had built we knew we would marvel at who they were, at what they were. We were a short flight from the fulfillment of our life's purpose.

* * *

Marines escorted us to our shuttles. The wide corridors of the ship suddenly felt tight. We stayed close together, hands touching, and said nothing. Even through the logos all we shared were vague assurances, the soldiers' stiff presence acting like a muffle on our enthusiasm.

Kovesh waited in the lead shuttle.

"A platoon is waiting on the surface," she said. "Each group will go down with an escort of three. I'll ride this one down. All the shuttles will maintain standby once we're down, so should anything arise we'll be able to get you off quickly."

Eleven of us in each group. I missed Merril. He rode down with a different shuttle. We sat in couches that faced across a narrow walkway from each other. One marine sat forward, the other aft, while Kovesh went up by the pilot.

There was no view outside. We held hands and looked across at ourselves and tried to imagine what happened from sounds and vibrations. We knew the moment the shuttle left the ship, we had all felt that characteristic sensation before. Then the soundless time of freefall…then the first brush of atmosphere…the shuttle bounced and we could hear a high-pitched whine through the bulkheads. An air leak? That meant a breach…but no alarms flashed, except the fear transmitted back and forth through our hands, building quickly to near panic until Kovesh came back and told us we would land in five minutes. The panic subsided like water sloshing back and forth until it loses momentum and finds equilibrium.

But our equilibrium now rested on a thin layer of anxiety.

A series of harsher sounds and heavier shocks followed. I squeezed the hands I held tight and they gripped me harder till my fingers began to go numb, till everyone's fingers tingled, and passed the sensation back and forth.

Then silence.

Kovesh stepped down the walkway between us. A few seconds later the hatch opened with a loud pneumatic hiss.

We waited. I imagined us as cargo, the marines our deliverers, and passed the thought along. A few smiles came back and we relaxed a little.

"All right," Kovesh snapped, leaning into the shuttle. "Stay close. The other shuttles are down now. You'll be taken to your temporary quarters."

Umbilicals attached the shuttle locks to the environ module. We stepped into a wide chamber, the support ribs naked against the walls and ceiling, the air chilled so that we could see our breath. We came together immediately, all thirty-three of us, in the center of the chamber, reestablishing contact as if we had been separated for days or years. Merril walked around our perimeter saying over and over that everything was all right, everything was fine.

I looked back to the locks then and saw marines standing at each. I searched the chamber for Admiral Kovesh and found her speaking to two men at the opposite end of the module. More marines flanked them. Then I noticed that marines stood against the walls all around us.

Merril continued his orbit, his reassurances, until Kovesh summoned him.

* * *

After the Change we laughed and cried together. Pain and pleasure became a shared thing, what one experienced cascaded through all of us. For a time there was concern that we would fail to individuate. It became necessary to shut us down from time to time, force us to form independent identities. It was a lot like learning to walk, then run, then walk and run in self-directed patterns, then integrate it all into an automatic decision-making hierarchy that worked without constant conscious monitoring. You don't think your way across a room, down a street, over a hill, or through a city, you just go in response to an abstract desire to go somewhere.

Eventually we developed individual traits, some degree of autonomy, but it never felt natural. Forced separation always hurt. Short periods of apartness were tolerable only because we knew we would be together again. Soon.

* * *

The meeting hall stood in the middle of a sodium-white field, gothic in proportion, elegant, delicate, emblematic. Its machinery encapsulated each group in an appropriate atmosphere, clearly seti tech. The marines had told us about it. They were disturbed, a bit awed.

"This is a formal occasion," Merril told us, "an introduction. You won't be doing anything here. We're just meeting the representatives."

We entered the central hall. Sounds echoed oddly, bouncing as it did through mixed gases. It felt as if we were immersed in an invisible sea.

The setis stood arrayed around the perimeter, formed up in loose groups, some of which contained more than one species. Some were bipeds, others without visible limbs, a few with no discernible "heads," and one that seemed nothing but a tangle of articulating limbs. The fields in which they stood refracted light differently. When they moved and the fields overlapped, colors warped out of true, bent, and dazzled.

We spread out. Their designated speakers separated from their parties and approached the center. The light was coppery, liquid. Pride welled up within us. We had trained for this, been created for this, designed for this.

Sound washed through the hall. Bass, treble, mixes of tone that verged on music, then slid away into barely ordered chaos…they spoke! We touched hands, passed our impressions down the line, always with the underthought that this is what we had come to solve.

The human delegates stood up, then, and read from a prepared statement. We heard little of it. The setis held our attention. This was all politics, this meeting. A show. It was being recorded, we knew, and would be used later, excellent press. The real work would be done under less dramatic circumstances. But this alone seemed worth the journey. If we could freeze the moment like this…it was perfect, just as it was. Uncomplicated by articulation.

We gazed across the hall at each other. I felt nothing at that instant but anticipation.

* * *

Of course it made perfect sense. We couldn't do what was required all bunched together in a group, mingled with all the seti at once. The cascade of impressions would ruin the uniqueness of each language. We had to isolate each seti and work on its language apart from the rest. Perfectly reasonable.

"There are five major groups," Ambassador Sulin explained. "Rahalen, Cursian, Vohec, Menkan, and Distanti. There are numerous other allied and nonaligned races, some of them present, but from what we've been able to determine, these five are the primary language groups. Translate these and we can communicate with most of the others."

He cleared his throat and glanced at Merril. "I didn't expect them to be so young," he said.

"It was in the précis we sent," Merril said, frowning.

"Yes, but…well." He shrugged and looked at us. "Each team will contain five people. Two linguists and three of you. We're not sure how many individuals will attend each seti representative, but the work rooms aren't that large, so we don't expect much more on their part. Now, what we want is for you to choose a back-up group among yourselves for each language. When you come out of a session, you go immediately to that group and work over what you've, uh, learned. Don't cross-reference with the other groups, please, not until we've got some kind of handle on each language."

"The setis communicate among themselves, don't they?" I asked.

"Yes, as far as we know."

"Then they already have a common set of referents. Wouldn't it be sensible to try to find that first?"

"Good question. But what we want is to have some basis of understanding for each group individually first. Then we can go on from there."

"But—"

"This is the procedure we will use."

"Uh," Merril said, "Ambassador, it's just that the idea of separation is unpleasant for them."

"Then they'll have to get used to it."

* * *

[Continue to Part 3]

---------------

"Texture of Other Ways" is © 1999 by Mark W. Tiedemann and is reprinted here with permission of the author. The story was originally published in Science Fiction Age, September 1999, and will be included in anthology Alien Contact, edited by Marty Halpern and forthcoming from Night Shade Books in November.

Published on August 17, 2011 14:49

August 15, 2011

Alien Contact Anthology -- Story #16: "Texture of Other Ways" by Mark W. Tiedemann (Part 1 of 3)

Following is story #16 from my forthcoming anthology Alien Contact, to be published in November by Night Shade Books. For more information on this anthology, and to see the first 15 stories, please begin here.

"Texture of Other Ways"

by Mark W. Tiedemann

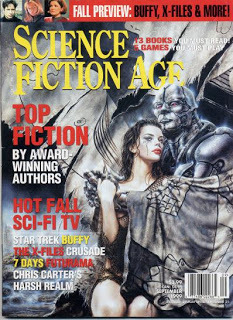

This story was originally published in the September 1999 issue of

Science Fiction Age

1, and is approximately 5,700 words in length.

This story was originally published in the September 1999 issue of

Science Fiction Age

1, and is approximately 5,700 words in length.

In my first blog post on the Alien Contact anthology on November 23, 2010, I asked readers -- and authors -- to recommend stories. Mark W. Tiedemann was one of the responders, and in addition to recommending a Philip K. Dick story, he also, thankfully, recommended his own story "Texture of Other Ways."

I wanted a story for the anthology that focused on human-alien communication. I've read enough stories in which the aliens easily communicate with humans because they've been studying our language for years, or decades, or even centuries. And though I read quite a few stories that approached the human-alien communication issue differently, I selected "Texture of Other Ways." I asked Mark to share some thoughts with us on the story:

So how is this story different in terms of human-alien communication? The humans selected to meet with the aliens are "telelogs." As the narrator states later in the story: "We aren't psychics in the traditional sense. That's why we're called telelogs rather than telepaths. At infancy we were implanted with a biopole factory, a device called the logos. The logos transfers a colony of biopole, which seats itself in the recipient brain, and starts setting up a temporary pattern analyzer. Very quickly—I'm talking nanoseconds—the colony establishes a pattern, sets up a transmission, and within moments the contents of the mind are broadcast to the primary logos." So we have this unique group of humans able to communicate amongst themselves as telelogs. And, by the way, these humans will be meeting with multiple alien species representing five primary language groups. But then, as the author states, let's just bypass language altogether.

Read the story for yourself here on More Red Ink, which I am posting in its entirety, in three parts, with the kind permission of the author. Enjoy.

Texture of Other Ways

by Mark W. Tiedemann

(© 1999 by Mark W. Tiedemann.

Reprinted with permission of the author.)

The media followed our course from colony to colony all the way out to Denebola, where the conference was held. Our ship moved magisterially into and out of dock at each port, unnecessarily slow. At first it amused us, but after ten such stops it became ridiculous. We wanted to huddle in our quarters, close together, and ignore the hectoring questions, the lights, the monitors, the enforced celebrity.

Merril, our liaison, did his best to mollify us and satisfy them, but in the end his efforts always came up short. It occurred to me that the public nature of the project was a mistake, but when I gave this notion to the rest they shrugged together and said it wasn't our mistake.

Earth to Median, halfway to the Centauri group; on to Centauri Transit Station; then to Procyon and on to Epsilon Eridani and Tau Ceti. We bypassed Eurasia, the colony at 40 Eridani. We were never told why. But we stopped at 82 Eridani, the colony of Eridanus. Aquas, Fomalhaut, Nine Rivers, Millennium, and Pollux.

Pan Pollux proved the worst. We felt like curiosities under glass for the wealthy patrons of the resorts. Till then I'd always believed people had a finer appreciation of the difference between the merely unusual and the special. We gathered together in the lounge and formed a cluster in the center of the floor and communed with each other, playing games of dancing from mind to mind, chasing ideas back to their sources, switching perspectives, and seeing how many we could be at one time. In the middle of this probes managed to sneak in past our security. I'm still convinced this was allowed to happen. The Forum counted on a rich political reward from our mission and the temptation to exploit us through any media outlet available was irresistible. Poor Merril, he believed in his job, tried ardently to meet its requirements, but there was only so much he could do in the face of the great need of human polity. We were ostensibly the saviors of humankind, it was necessary that our march toward Golgotha be witnessed.

All the probes saw, though, was a group—thirty-three of us—sitting tightly together on the floor of our lounge, eyes closed, heads bobbing slightly, here and there drool from a mouth, the twitch of a limb, perhaps an occasional tuneless hum. What the viewing public must have thought of its savior! Their fate in the hands of—what?

* * *

When they changed me there was no question of choice. Seven hundred days old, you don't even realize that the world isn't part of you, much less that it doesn't care. Understanding that only discreet parts of it care is something that comes much later, if at all. It's a sophisticated distinction, this sorting out, a concept constantly threatened by the fact that even the caring parts probably don't care about you. But in time we all learn that everything around us, everything that happens, is organized into packets of information and those packets can be assembled by consciousness into something that has order and meaning. A fiction, perhaps, and it's a question whether the boundaries that keep everything apart are internal or external. An academic question, of no real consequence.

Unless those boundaries disappear.

When they changed me—and the others, all thirty-three of us—several of those boundaries vanished and had to be replaced by something else, a different method of perception and ordering. At seven hundred days old I didn't "understand" this—none of us did—all we could do was react. There is a murk at the bottom of my memory that intrudes from time to time into my dreams, but which I assiduously avoid contemplating most of the time. I tell myself that this swamp is the residue of my reaction. I tell myself that. On the rare occasions when I conjure enough courage to be determinedly self-analytical I think—I believe—that it is the residue of thirty-three reactions. Then I wonder how we all sorted ourselves out of the mix. Then I wonder if we ever did. Then I stop thinking about it.

* * *

Our ship met with a convoy halfway from Pan Pollux to Denebola. You never really see ships at dock, each one is berthed separately in the body of the station. Once in a while another ship leaves dock at the same time you do and you get to see one of them against the stars. I sometimes think these vessels are the most beautiful objects humans ever built. Elegant, powerful, freighted with every aspect of our natures—hope, pride, ambition, curiosity, wonder, and fear. When the convoy gathered around us we stared at the two dozen ships.

"Whales."

"No, methane floaters."

"A school of armor."

I listened to the ripple of comparisons, trying to decide which one fit best. None really did. Whales in space? Too many lines, dark masses, geometries. Methane floaters drifted with the currents of their atmospheres, virtually helpless to control direction. These moved with power, purpose, a logical order to the way they arranged themselves around us, protecting us.

"Admiral Kovesh's task force," Merril announced. "They'll be our escort to Denebola."

"Will there be seti task forces there, too?" I asked.

Merril frowned slightly, clasped his hands behind his back the way he did when something made him uneasy. "I expect so."

I looked back at the Armada ships, excited at the prospect of comparing human and alien.

* * *

There was a reporter from the Ares-Epsilon NewsNet that kept up with us from Sol to Nine Rivers. He must have interviewed every one of us by then, some twice. On our last interview I decided to go for shock, to see how he'd react.

"The development of telepaths is a radical step in human evolution," he said. "According to scientists, we've been capable of such a step for a long time but we've refrained. Why do you think it took a First Contact situation to push us into it?"

"Fear."

"Fear? In what way?"

"They couldn't talk to the seti, so the Armada started planning for war. It's that simple. Say something we understand or we'll shoot. The Pan Humana wanted to believe the human race was beyond ancient formulas for defending the cave, but it's been centuries since words failed to convey meaning, so the old ways had been forgotten."

His eyes brightened. This was better than the prepared statements we'd been delivering all along.

"Then the seti showed up and the race panicked. Not one word made sense. You're right, we've been capable of producing telepaths—actually, the term is telelog, there's a difference—for a long time. But people are afraid of the idea. That's the only real area of privacy, your thoughts. But when the Chairman, the Forum, and the Armada realized that the most insurmountable problem confronting them with the setis was language, they seized the opportunity. It was a question of weighing competitive fears. Of course, fear of the alien won out."

"Yes, but in a very fundamental way, you're alien, too."

"But at least we look human."

I don't think his report ever made it onto the newsnets. He didn't continue on with us after Nine Rivers.

* * *

Denebola is a white, white sun, forty-three light-years from Earth. It shepherds a small herd of Jovians and two hard planets, none of which is hospitable to human life without considerable manipulation. As far as I have learned, no plans have been made to terraform.

I always wondered why Denebola. Well, it is right out there at the limit of our expansion. There are a few colonies further out, but in the pragmatic way such things are judged by the Forum they don't count because they're too tenuous. But we didn't pick Denebola. They did. The setis.

Stars have many names and now that we've met our neighbors I'm sure the number will increase again. Denebola has three that I consider ironically appropriate. Denebola itself is from the Arabic Al Dhanab Al Asad, the Lion's Tail. But there's another Arab name for it, Al Sarfah, the Changer. I like that better, it seems more relevant to my own situation, to our situation. The place of changes, changes wrought by the place itself.

The third name? Chinese, Wu Ti Tso, Seat of the Five Emperors.

* * *

[Continue to Part 2]

---------------Footnote:

1. Science Fiction Age was a very fine SF magazine that got away... It was started by Sovereign Media in November 1992 and ran through May 2000. Through the magazine's entire run, Scott Edelman served as the editor. Though profitable at the time of its demise, SF Age, unfortunately, wasn't sufficiently profitable for Sovereign Media. By the way, Sovereign Media also published Realms of Fantasy magazine, beginning in October 1994, and then canceling the magazine with the April 2009 issue due to "plummeting newstand sales." However, RoF was purchased by a new publisher who, at the end of 2010, sold the magazine to yet a third publisher. SF Age was not as fortunate, which led to Scott Edelman's Second Rule of Publishing: "Make sure you retain the rights to your magazine." [Note: I have been copyediting Realms of Fantasy magazine since the October 2009 issue.]

"Texture of Other Ways"

by Mark W. Tiedemann

This story was originally published in the September 1999 issue of

Science Fiction Age

1, and is approximately 5,700 words in length.

This story was originally published in the September 1999 issue of

Science Fiction Age