Marty Halpern's Blog, page 35

August 20, 2012

Does Google Dream of Electric Sheep?

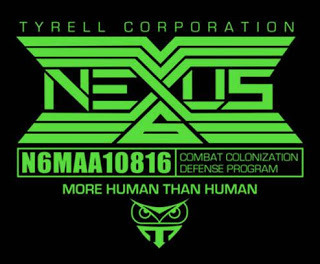

"Nexus 6 Replicants" graphic by Superior Graphix

I got the urge recently to reread Philip K. Dick's Do Android's Dream of Electric Sheep? as it's been about 20 years since I last read this wonderful novel. It's so much different than the movie Blade Runner, which is based on DADOES?

The novel doesn't have the visual impact of the movie, nor does it have the manic emotions and level of violence of the movie. The novel is a completely different [reading] experience -- and if you are a fan of the movie and have not read the novel, I encourage you to do so.

But the novel notwithstanding, I am a huge fan of Blade Runner and, in fact, I own three versions of the movie: the original version with the voice-over (on video), the Director's Cut and the Final Cut (both on DVD). One of my favorite scenes: following the fight between the replicant Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer) and Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford), on the rooftop, after Batty saves Deckard, when Batty could have easily just let Deckard fall to his death below. Batty, with symbolic white bird in hand, says to Deckard (and to everyone):

"I've seen things you people wouldn't believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I've watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhauser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain. Time to die."

PKD was offered $400,000 to write a novelization of the movie, but he refused, stating that the novel would remain as is and there would be no novelization. Now, to put that $400,000 in perspective: Since the film was released in June 1982, let's assume that the novelization offer was made in 1981. According to DollarTimes's inflation calculator, the inflation rate since 1981 is 3.15%; so $400,000 in 1981 is equivalent to $1,045,988.41 (let's not forget the 41 cents!) in 2012.

So, my question to you: Would you be willing able to turn down a million-plus dollars to maintain the integrity of your novel, your writing? Sorry, but I don't think so, not in this day and age of me, me, me....

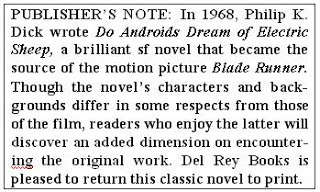

In the end, in 1982, Del Rey Books released a mass market paperback movie tie-in version of the novel, featuring the Blade Runner title and promo poster on the cover, with the subtitle -- Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? -- in parenthesis. And on the copyright page the following blocked text was added:

[Note: This too explains why there hasn't been a blog post since the beginning of the month....]

Since the N7 is made of Corning Glass (and not Gorilla Glass) -- and since I'm a firm believer in Murphy's Law -- I immediately applied a custom fit XO Skins screen protector to the device. It applied easily enough, but be sure to watch the manufacturer's video. Around the 43-hour mark, I was able to use the tab, but I still encountered some degradation in screen sensitivity. However, by 48 hours, all the micro bubbles had disappeared and the tab was good to go.

The first app I installed was the SwiftKey 3 keypad ($3.99). I'm a touch typist; on a familiar keyboard I can type over 70 wpm with about 98% accuracy. (I know this because a few years ago I applied for a contract position and had to take a bloody MS Office test and a typing test!) But on the N7 I'm having to use a single finger or, occasionally, both thumbs, and -- well, I'm all thumbs. But SwiftKey is awesome because it learns your vocabulary and anticipates what you will type next.

In a previous blog post, I wrote about my use of Calibre software for managing my ebook library. So I installed the Calibre Library app ($2.99), which essentially allows me to turn my desktop PC into a virtual server so that I can transfer ebooks wirelessly from my PC to the N7. No need to tether the N7 to the PC using the micro USB connector. As long as my PC and N7 are connected on the same wireless network, I'm in ebook heaven.

I use Amazon a lot -- a lot! So I wanted to install the Amazon Mobile app on the N7 so that I could search, compare prices, etc. Unfortunately, if I select that app on the Google Play store (the default for the N7), a notice appears informing me that the app is not compatible on the N7. However, I've read a lot of posts online from users who state the Amazon Mobile app works just fine on the N7, you just have to install it from the Amazon App Store instead of Google Play. However, there's a catch: to install an app from a source other than Google Play, in the N7's Settings, you have to enable the "Unknown sources" check box. So, once that check box is enabled, you can install the Amazon App Store app from Google Play, then go to Amazon.com and "Get now with 1-Click" the Amazon Mobile app. Open the Amazon App Store app on your N7, and you should see a notice that the Amazon Mobile app is ready to install. Did you get all that?

I've added quite a few other apps as well: the $25 of free Google Play money that came with the N7 purchase has covered everything so far, since the majority of the apps are free.

Next on my list is the Facedroid app ($1.99). I had an interesting albeit frustrating experience attempting to use Facebook on the N7 -- which has forced me to purchase an FB app. If you are an FB user, go to your page and look at it: If you enter a new update, the field has a "Post" button to click to actually post the update. However, select someone else's post on your wall and click in the Comment field. No "Post" button, because the way to enter a comment is to simply hit the "Enter" key on your keyboard when you are ready to post. The problem I encountered on the key pad is that there was no equivalent "Enter" key, so after typing my comment, I then realized that I wasn't able to post it. Plus, I couldn't enlarge any content on the screen so all the fonts were tiny, etc. Facebook has an official app, but from everything I've read, it sucks (and that's being polite). So that leaves Facedroid. It's not perfect, but the developers promise an upgrade optimized for the N7 within a couple weeks, at which time the price will supposedly increase as well. So buy now, and upgrade later.

I have the Pocket app to save web pages offline to read at a later time; I've also installed Pocket on my desktop and laptop so that I can sync across all devices: I save a web page to Pocket on my desktop, and read it later in the evening on the N7. Same for Evernote: install it on all devices and it syncs across all devices. This is a great pkg. for creating notes, lists, etc. If I read one of my offline web pages in Pocket and see something I would like to quote, say, on FB or in my blog, I can highlight any text or graphic and copy it to Evernote, where I can then enter notes, or even begin working on a blog post. Very cool.

Other apps I've installed include Feedly, for reading RSS feeds and blogs; it too syncs with Feedly running on my desktop; Avast Mobile Security; Easy Battery Saver; My Backup Pro ($4.99); ES File Explorer; WiFi File Transfer; and ezPDF Reader Form ($2.99); to name a few.

Obviously, since the N7 is a Google product (though it's built by ASUS, for whom I have a fondness as they are the makers of my most excellent Zenbook), all Google products: Google Drive, Gmail, Chrome, etc. are synced across all devices. On my N7, I can access any bookmark that I've previously saved in Chrome on my desktop, for example.

Apple Corp. may be the best company in terms of financial prowess, but I swear it will be Google that will take over the world.

Published on August 20, 2012 21:29

August 8, 2012

July Links & Things

The past five or so weeks have been very busy for me -- but having work to do is always a good thing: it helps to pay the bills. I completed a developmental edit on a manuscript for an unpublished author; I completed a line and copy edit on reprint anthology

The Apes of Wrath

for Tachyon Publications (edited by Rick Klaw); and lastly, I completed a comprehensive line and copy edit (and some content editing as well) on Kameron Hurley's

Rapture

for Tachyon Publications (edited by Rick Klaw); and lastly, I completed a comprehensive line and copy edit (and some content editing as well) on Kameron Hurley's

Rapture

, the final volume in her Bel Dame Apocrypha series, for Night Shade Books. Oh, and for my own personal reading (which occurs so seldom anymore), I read the omnibus edition of

Wool

, the final volume in her Bel Dame Apocrypha series, for Night Shade Books. Oh, and for my own personal reading (which occurs so seldom anymore), I read the omnibus edition of

Wool

by Hugh Howey -- one of the finest works of post-apocalyptic SF that I have read in years. I don't recall any typos at all, though there was the occasional dropped word, missing hyphenation, etc., but that's it. Imagine that -- and a self-published book, too!

by Hugh Howey -- one of the finest works of post-apocalyptic SF that I have read in years. I don't recall any typos at all, though there was the occasional dropped word, missing hyphenation, etc., but that's it. Imagine that -- and a self-published book, too!

I also attended Readercon in mid-July; there are aspects of Readercon that I truly enjoy, but too much of it is simply cliquish and pedantic -- and thus not my personal preference; but I attend roughly every other year for the sole purpose of seeing friends whom I would not ever see otherwise. But, it turned out that this year's Readercon wasn't so typical after all, as a lot of controversy ensued afterward. Just search for "Readercon controversy" in any search engine and you'll find enough links. Or, you could check out John Scalzi's blog post: he links to a list of "Readercon controversy" posts, and provides his own personal view on convention harassment. Bottom line: the Readercon board of directors reversed their initial decision regarding a Readercon attendee, and they have all resigned from their positions as directors. You can read the official public Readercon statement.

Now to resume my regularly (albeit late) scheduled programming: This is my monthly wrap-up of July's Links & Things. You can receive these links in real time by following me on Twitter: @martyhalpern; or Friending me on Facebook (FB). Note, however, that not all of my tweeted/FB links make it into these month-end posts. As with prior months, June was a busy month, so there is a lot of content here. Previous monthly recaps are accessible via the "Links and Things" tag in the right column.

If you are a Facebook user -- and a writer -- you may want to add the following group to your FB profile: OPEN CALL: SCIENCE FICTION, FANTASY & PULP MARKETS. The majority of posts are made by Cynthia Ward, publisher of Market Maven , but anyone can post an open call for genre submissions. There have been a half-dozen posts already today, which is fairly typical.

I recently critiqued a couple stories for a "new" writer, after which he contacted me about ways he might improve his grammar. I recommended that he read works by a few specific authors, one of which was Lucius Shepard. Shortly thereafter I read a blog post by Michael Swanwick (another author whose work I would highly recommend) in which he quoted a lengthy paragraph written by Lucius Shepard; in this paragraph, a tyrant's son restores a dragon skull. The paragraph is approximately 160 words, and includes very few adjectives and only two adverbs. As Michael says about the paragraph: "Beautiful stuff, eh?"

On Salon.com: In an article entitled "Thank you for killing my novel," author Patrick Somerville explains how the New York Times "panned my book, then had to correct the review to fix all their errors"; he then shares the email communication one of the book's characters (yes, that's right, a character from the book) had with an NYT editor. (via Curt Jarrell's Facebook page)

I do a lot of copy editing in my line of work, and if you've ever wandered just what a copy editor does -- a good copy editor -- then read this next link and be amazed: courtesy of Angry Robot Books (@angryrobotbooks). (also via Curt Jarrell's Facebook page)

I don't know whether to follow-up with another link on Angry Robot Books or another link on editing. Decisions, decisions....

Let's go with editing, first: author Rachel Abbott writes about the editing process: "great fun, or complete nightmare?" -- "...I was living under the misapprehension that when somebody edits your book, they find all the bits that could be better, and they rewrite them. Oh no. Nothing like that at all.... You get back your whole book with notes scribbled all over it.... Once I had got over the shock, it was an almost liberating experience." She discusses Point of View, Show and Tell, Emotion, Characters, Action, and Reading aloud. (via @lkblackburne)

Here's one more on editing (What do you expect? I'm an editor!): This blog post is from my friend (and fellow editor) Dario Ciriello on the "Slushpile and Editor Mind." Dario writes: "In my own experience with Panverse [an anthology series], I found that only about ten percent of submissions [nearly 500 novellas] need to be read beyond the first few paragraphs, and maybe only half of those to the end. Poor prose skills, muddled thinking, third-hand ideas, a gift for tedium, or simply the absence of anything interesting--all these, if present, will jump out at the editor in the first paragraph or two and earn you a swift rejection."

Now, back to Angry Robot Books, a publisher located in the UK: During the first week of July, Angry Robot initiated a new program, called Clonefiles, in which the publisher partners with an independent book store. The first bookstore was Mostly Books of Abingdon, Oxfordshire: When customers of Mostly Books purchase an Angry Robot title, they will receive at no extra charge a "DRM-free eBook version (the Clonefile) of the book as part of the sale, allowing them to read the novel on paper, on their Kindle, or on their ePub-based eBook reader." Kudos to Angry Robot for thinking outside the box. This program will be expanded to include other indie bookstores in the near future. (via @welovethisbook)

From The Christian Science Monitor blog: "Some good news for the book business -- BookStats, an annual survey that tracks the American publishing industry, finds that, contrary to doomsday predictions, bookstores and paper-and-ink books are still in demand." (via @HCIBooks1) [I'm shocked, shocked I say....]

In a blog post on book research -- "how far does author research need to go? -- author Joe McCoubrey writes: "It is self-evident that the more an author puts into a story, the more a reader will get out of it. Solid research will underpin the credibility of what lies between the covers of a book and help build the trust of those who are paying to be entertained and informed."

Via Digital Book World (@DigiBookWorld): The publishing/self-publishing industry was abuzz this past month over the news that author Penelope Trunk, having signed a contract (and collected an advance) with a mainstream publisher for a non-fiction title, determined that the publisher was incapable of successfully marketing her book in today's media-oriented and ebook-centric environment, and decided to self-publish the book instead.

The Turkey City Writer's Workshop, now in Austin, Texas, was founded in 1973 and is still active today. Two of its members (or former members), Bruce Sterling and Lewis Shiner, compiled the Turkey City Lexicon -- "The Workshop Lexicon is a guide (of sorts) for down-and-dirty hairy-knuckled sci-fi writers, the kind of ambitious subliterate guttersnipes who actually write and sell professional genre material. It's rough, rollicking, rule-of-thumb stuff suitable for shouting aloud while pounding the table" (from the second edition's introduction by Bruce Sterling) -- which is available online at the above link. (via @galleycat)

And finally, The Opinion Pages in The New York Times asks the most critical, all-consuming question of all time: "So what happens to all my Kindle e-books when I die?" (via @PYOEbooks)

for Tachyon Publications (edited by Rick Klaw); and lastly, I completed a comprehensive line and copy edit (and some content editing as well) on Kameron Hurley's

Rapture

for Tachyon Publications (edited by Rick Klaw); and lastly, I completed a comprehensive line and copy edit (and some content editing as well) on Kameron Hurley's

Rapture

, the final volume in her Bel Dame Apocrypha series, for Night Shade Books. Oh, and for my own personal reading (which occurs so seldom anymore), I read the omnibus edition of

Wool

, the final volume in her Bel Dame Apocrypha series, for Night Shade Books. Oh, and for my own personal reading (which occurs so seldom anymore), I read the omnibus edition of

Wool

by Hugh Howey -- one of the finest works of post-apocalyptic SF that I have read in years. I don't recall any typos at all, though there was the occasional dropped word, missing hyphenation, etc., but that's it. Imagine that -- and a self-published book, too!

by Hugh Howey -- one of the finest works of post-apocalyptic SF that I have read in years. I don't recall any typos at all, though there was the occasional dropped word, missing hyphenation, etc., but that's it. Imagine that -- and a self-published book, too!I also attended Readercon in mid-July; there are aspects of Readercon that I truly enjoy, but too much of it is simply cliquish and pedantic -- and thus not my personal preference; but I attend roughly every other year for the sole purpose of seeing friends whom I would not ever see otherwise. But, it turned out that this year's Readercon wasn't so typical after all, as a lot of controversy ensued afterward. Just search for "Readercon controversy" in any search engine and you'll find enough links. Or, you could check out John Scalzi's blog post: he links to a list of "Readercon controversy" posts, and provides his own personal view on convention harassment. Bottom line: the Readercon board of directors reversed their initial decision regarding a Readercon attendee, and they have all resigned from their positions as directors. You can read the official public Readercon statement.

Now to resume my regularly (albeit late) scheduled programming: This is my monthly wrap-up of July's Links & Things. You can receive these links in real time by following me on Twitter: @martyhalpern; or Friending me on Facebook (FB). Note, however, that not all of my tweeted/FB links make it into these month-end posts. As with prior months, June was a busy month, so there is a lot of content here. Previous monthly recaps are accessible via the "Links and Things" tag in the right column.

If you are a Facebook user -- and a writer -- you may want to add the following group to your FB profile: OPEN CALL: SCIENCE FICTION, FANTASY & PULP MARKETS. The majority of posts are made by Cynthia Ward, publisher of Market Maven , but anyone can post an open call for genre submissions. There have been a half-dozen posts already today, which is fairly typical.

I recently critiqued a couple stories for a "new" writer, after which he contacted me about ways he might improve his grammar. I recommended that he read works by a few specific authors, one of which was Lucius Shepard. Shortly thereafter I read a blog post by Michael Swanwick (another author whose work I would highly recommend) in which he quoted a lengthy paragraph written by Lucius Shepard; in this paragraph, a tyrant's son restores a dragon skull. The paragraph is approximately 160 words, and includes very few adjectives and only two adverbs. As Michael says about the paragraph: "Beautiful stuff, eh?"

On Salon.com: In an article entitled "Thank you for killing my novel," author Patrick Somerville explains how the New York Times "panned my book, then had to correct the review to fix all their errors"; he then shares the email communication one of the book's characters (yes, that's right, a character from the book) had with an NYT editor. (via Curt Jarrell's Facebook page)

I do a lot of copy editing in my line of work, and if you've ever wandered just what a copy editor does -- a good copy editor -- then read this next link and be amazed: courtesy of Angry Robot Books (@angryrobotbooks). (also via Curt Jarrell's Facebook page)

I don't know whether to follow-up with another link on Angry Robot Books or another link on editing. Decisions, decisions....

Let's go with editing, first: author Rachel Abbott writes about the editing process: "great fun, or complete nightmare?" -- "...I was living under the misapprehension that when somebody edits your book, they find all the bits that could be better, and they rewrite them. Oh no. Nothing like that at all.... You get back your whole book with notes scribbled all over it.... Once I had got over the shock, it was an almost liberating experience." She discusses Point of View, Show and Tell, Emotion, Characters, Action, and Reading aloud. (via @lkblackburne)

Here's one more on editing (What do you expect? I'm an editor!): This blog post is from my friend (and fellow editor) Dario Ciriello on the "Slushpile and Editor Mind." Dario writes: "In my own experience with Panverse [an anthology series], I found that only about ten percent of submissions [nearly 500 novellas] need to be read beyond the first few paragraphs, and maybe only half of those to the end. Poor prose skills, muddled thinking, third-hand ideas, a gift for tedium, or simply the absence of anything interesting--all these, if present, will jump out at the editor in the first paragraph or two and earn you a swift rejection."

Now, back to Angry Robot Books, a publisher located in the UK: During the first week of July, Angry Robot initiated a new program, called Clonefiles, in which the publisher partners with an independent book store. The first bookstore was Mostly Books of Abingdon, Oxfordshire: When customers of Mostly Books purchase an Angry Robot title, they will receive at no extra charge a "DRM-free eBook version (the Clonefile) of the book as part of the sale, allowing them to read the novel on paper, on their Kindle, or on their ePub-based eBook reader." Kudos to Angry Robot for thinking outside the box. This program will be expanded to include other indie bookstores in the near future. (via @welovethisbook)

From The Christian Science Monitor blog: "Some good news for the book business -- BookStats, an annual survey that tracks the American publishing industry, finds that, contrary to doomsday predictions, bookstores and paper-and-ink books are still in demand." (via @HCIBooks1) [I'm shocked, shocked I say....]

In a blog post on book research -- "how far does author research need to go? -- author Joe McCoubrey writes: "It is self-evident that the more an author puts into a story, the more a reader will get out of it. Solid research will underpin the credibility of what lies between the covers of a book and help build the trust of those who are paying to be entertained and informed."

Via Digital Book World (@DigiBookWorld): The publishing/self-publishing industry was abuzz this past month over the news that author Penelope Trunk, having signed a contract (and collected an advance) with a mainstream publisher for a non-fiction title, determined that the publisher was incapable of successfully marketing her book in today's media-oriented and ebook-centric environment, and decided to self-publish the book instead.

The Turkey City Writer's Workshop, now in Austin, Texas, was founded in 1973 and is still active today. Two of its members (or former members), Bruce Sterling and Lewis Shiner, compiled the Turkey City Lexicon -- "The Workshop Lexicon is a guide (of sorts) for down-and-dirty hairy-knuckled sci-fi writers, the kind of ambitious subliterate guttersnipes who actually write and sell professional genre material. It's rough, rollicking, rule-of-thumb stuff suitable for shouting aloud while pounding the table" (from the second edition's introduction by Bruce Sterling) -- which is available online at the above link. (via @galleycat)

And finally, The Opinion Pages in The New York Times asks the most critical, all-consuming question of all time: "So what happens to all my Kindle e-books when I die?" (via @PYOEbooks)

Published on August 08, 2012 16:27

August 5, 2012

Firefly-class Serenity

"They" say a picture is worth a thousand words, but in this case, this one photo is simply not enough to do justice to this amazing wonderwork: a minifig-scale model of the Serenity spacecraft created with Legos. That's right, boys and girls: Legos!

This model was recently featured on io9:

The designer is 37-year-old Adrian Drake. According to Adrian, the model took 475 hours to build over a span of 21 months; it measures 7 feet 2 inches in length, weighs 135 pounds, and contains approximately 70,000 lego pieces. Adrian states that he spent $800.00 specifically for the model in addition to the "many many many thousands of dollars I've spent on Lego over the years."

Adrian debuted the Serenity on August 4 at Brickfair in Chantilly, Virginia. And to get a sense of the size of this model, you need to see this picture, taken at the Brickfair:

But even this photo doesn't do this masterpiece justice -- because... the interior features the bridge (in fact, Wash has his toy dinosaur to hand), crew accommodations, the dining room, and cargo bay, plus Inara's shuttle. And, the cargo bay and Firefly drive light up.

Seeing is believing: Adrian has posted a 31-photo Flickr set entitled "Serenity Construction," and the coup de grâce: a 75-photo Flickr set featuring a look at the finished model, inside and out, from every angle imaginable.

Please do check out these 106 photos, which showcase Adrian Drake's Serenity.

Now, who's for getting out their Lego sets?

Published on August 05, 2012 15:35

July 23, 2012

More Alien Contact Anthology PR

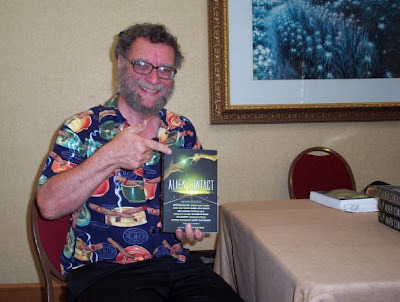

Michael Swanwick, author of the story "A Midwinter's Tale," doing his best PR routine for Alien Contact

at Readercon, Burlington (Boston), Massachusetts, Friday, June 13, 2012. [Note the stack of ACs on the table next to Michael!]

at Readercon, Burlington (Boston), Massachusetts, Friday, June 13, 2012. [Note the stack of ACs on the table next to Michael!]And speaking of PR:

If you are interested in reviewing the Alien Contact anthology, please contact me: you can post a comment below or, if you would prefer a private email, just click on "View my complete profile" for a link to my email addy. I can provide a print copy, a PDF file, a Kindle ebook, or Nook/Sony/Kobo ebook. In your comment or email, please include a link to your book review site or, if you review for another resource, a link to one of your reviews. And if you have any questions, you now know how to contact me.

Published on July 23, 2012 19:55

July 21, 2012

"One" by George Alec Effinger (Part 3 of 3)

One

by George Alec Effinger

[Continued from Part 2]

"I have strange thoughts, Jessica," he admitted to her, one day during their ninth year of exploration. "They just come into my head now and then. At first I didn't pay any attention at all. Then, after a while, I noticed that I was paying attention, even though when I stopped to analyze them I could see the ideas were still foolish."

"What kind of thoughts?" she asked. They prepared the landing craft to take them down to a large, ruddy world.

Gillette checked both pressure suits and stowed them aboard the lander. "Sometimes I get the feeling that there aren't any other people anywhere, that they were all the invention of my imagination. As if we never came from Earth, that home and everything I recall are just delusions and false memories. As if we've always been on this ship, forever and ever, and we're absolutely alone in the whole universe." As he spoke, he gripped the heavy door of the lander's airlock until his knuckles turned white. He felt his heart speeding up, he felt his mouth going dry, and he knew that he was about to have another anxiety attack.

"It's all right, Leslie," said Jessica soothingly. "Think back to the time we had together at home. That couldn't be a lie."

Gillette's eyes opened wider. For a moment he had difficulty breathing. "Yes," he whispered, "it could be a lie. You could be a hallucination, too." He began to weep, seeing exactly where his ailing mind was leading him.

Jessica held him while the attack worsened and then passed away. In a few moments he had regained his usual sensible outlook. "This mission is much tougher than I thought it would be," he whispered.

Jessica kissed his cheek. "We have to expect some kind of problems after all these years," she said. "We never planned on it taking this long."

The system they were in consisted of another class-M star and twelve planets. "A lot of work, Jessica," he said, brightening a little at the prospect. "It ought to keep us busy for a couple of weeks. That's better than falling through null space."

"Yes, dear," she said. "Have you started thinking of names yet?" That was becoming the most tedious part of the mission—coming up with enough new names for all the stars and their satellites. After eight thousand systems, they had exhausted all the mythological and historical and geographical names they could remember. They now took turns, naming planets after baseball players and authors and film stars.

They were going down to examine a desert world they had named Rick, after the character in Casablanca. Even though it was unlikely that it would be suitable for life, they still needed to examine it firsthand, just on the off chance, just in case, just for ducks, as Gillette's mother used to say.

That made him pause, a quiet smile on his lips. He hadn't thought of that expression in years. That was a critical point in Gillette's voyage; never again, while Jessica was with him, did he come so close to losing his mental faculties. He clung to her and to his memories as a shield against the cold and destructive forces of the vast emptiness of space.

Once more the years slipped by. The past blurred into an indecipherable haze, and the future did not exist. Living in the present was at once the Gillettes' salvation and curse. They spent their time among routines and changeless duties that were no more tedious than what they had known on Earth, but no more exciting either.

As their shared venture neared its twentieth year, the great disaster befell Gillette: on an unnamed world hundreds of light-years from Earth, on a rocky hill overlooking a barren sandstone valley, Jessica Gillette died. She bent over to collect a sample of soil; a worn seam in her pressure suit parted; there was a sibilant warning of gases passing through the lining, into the suit. She fell to the stony ground, dead. Her husband watched her die, unable to give her any help, so quickly did the poison kill her. He sat beside her as the planet's day turned to night, and through the long, cold hours until dawn.

He buried her on that world, which he named Jessica, and left her there forever. He set out a transmission gate in orbit around the world, finished his survey of the rest of the system, and went on to the next star. He was consumed with grief, and for many days he did not leave his bed.

One morning Benny, the kitten, scrabbled up beside Gillette. The kitten had not been fed in almost a week. "Benny," murmured the lonely man, "I want you to realize something. We can't get home. If I turned this ship around right this very minute and powered home all the way through null space, it would take twenty years. I'd be in my seventies if I lived long enough to see Earth. I never expected to live that long." From then on, Gillette performed his duties in a mechanical way, with none of the enthusiasm he had shared with Jessica. There was nothing else to do but go on, and so he did, but the loneliness clung to him like a shadow of death.

He examined his results, and decided to try to make a tentative hypothesis. "It's unusual data, Benny," he said. "There has to be some simple explanation. Jessica always argued that there didn't have to be any explanation at all, but now I'm sure there must be. There has to be some meaning behind all of this, somewhere. Now tell me, why haven't we found Indication Number One of life on any of these twenty-odd thousand worlds we've visited?"

Benny didn't have much to suggest at this point. He followed Gillette with his big yellow eyes as the man walked around the room. "I've gone over this before," said Gillette, "and the only theories I come up with are extremely hard to live with. Jessica would have thought I was crazy for sure. My friends on Earth would have a really difficult time even listening to them, Benny, let alone seriously considering them. But in an investigation like this, there comes a point when you have to throw out all the predicted results and look deep and long at what has actually occurred. This isn't what I wanted, you know. It sure isn't what Jessica and I expected. But it is what happened."

Gillette sat down at his desk. He thought for a moment about Jessica, and he was brought to the verge of tears. But he thought about how he had dedicated the remainder of his life to her, and to her dream of finding an answer at one of the stellar systems yet to come.

He devoted himself to getting that answer for her. The one blessing in all the years of disappointment was that the statistical data were so easy to comprehend. He didn't need a computer to help in arranging the information: there was just one long, long string of zeros. "Science is built on theories," thought Gillette. "Some theories may be untestable in actual practice, but are accepted because of an overwhelming preponderance of empirical data. For instance, there may not actually exist any such thing as gravity; it may be that things have been falling down consistently because of some outrageous statistical quirk. Any moment now things may start to fall up and down at random, like pennies landing heads or tails. And then the Law of Gravity will have to be amended."

That was the first, and safest, part of his reasoning. Next came the feeling that there was one overriding possibility that would adequately account for the numbing succession of lifeless planets. "I don't really want to think about that yet," he murmured, speaking to Jessica's spirit. "Next week, maybe. I think we'll visit a couple more systems first."

And he did. There were seven planets around an M-class star, and then a G star with eleven, and a K star with fourteen; all the worlds were impact-cratered and pitted and smoothed with lava flow. Gillette held Benny in his lap after inspecting the three systems. "Thirty-two more planets," he said. "What's the grand total now?" Benny didn't know.

Gillette didn't have anyone with whom to debate the matter. He could not consult scientists on Earth; even Jessica was lost to him. All he had was his patient gray cat, who couldn't be looked to for many subtle contributions. "Have you noticed," asked the man, "that the farther we get from Earth, the more homogeneous the universe looks?" If Benny didn't understand the word homogeneous, he didn't show it. "The only really unnatural thing we've seen in all these years has been Earth itself. Life on Earth is the only truly anomalous factor we've witnessed in twenty years of exploration. What does that mean to you?"

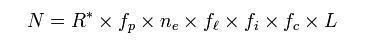

At that point, it didn't mean anything to Benny, but it began to mean something to Gillette. He shrugged. "None of my friends were willing to consider even the possibility that Earth might be alone in the universe, that there might not be anything else alive anywhere in all the infinite reaches of space. Of course, we haven't looked at much of those infinite reaches, but going zero for twenty-three thousand means that something unusual is happening." When the Gillettes had left Earth two decades before, prevailing scientific opinion insisted that life had to be out there somewhere, even though there was no proof, either directly or indirectly. There had to be life; it was only a matter of stumbling on it. Gillette looked at the old formula, still hanging where it had been throughout the whole voyage. "If one of those factors is zero," he thought, "then the whole product is zero. Which factor could it be?" There was no hint of an answer, but that particular question was becoming less important to Gillette all the time.

* * *

And so it had come down to this: Year 30 and still outward bound. The end of Gillette's life was somewhere out there in the black stillness. Earth was a pale memory, less real now than last night's dreams. Benny was an old cat, and soon he would die as Jessica had died, and Gillette would be absolutely alone. He didn't like to think about that, but the notion intruded on his consciousness again and again.

Another thought arose just as often. It was an irrational thought, he knew, something he had scoffed at thirty years before. His scientific training led him to examine ideas by the steady, cold light of reason, but this new concept would not hold still for such a mechanical inspection.

He began to think that perhaps Earth was alone in the universe, the only planet among billions to be blessed with life. "I have to admit again that I haven't searched through a significant fraction of all the worlds in the galaxy," he said, as if he were defending his feelings to Jessica. "But I'd be a fool if I ignored thirty years of experience. What does it mean, if I say that Earth is the only planet with life? It isn't a scientific or mathematical notion. Statistics alone demand other worlds with some form of life. But what can overrule such a biological imperative?" He waited for a guess from Benny; none seemed to be forthcoming. "Only an act of faith," murmured Gillette. He paused, thinking that he might hear a trill of dubious laughter from Jessica's spirit, but there was only the humming, ticking silence of the spacecraft.

"A single act of creation, on Earth," said Gillette. "Can you imagine what any of the people at the university would have said to that? I wouldn't have been able to show my face around there again. They would have revoked every credential I had. My subscription to Science would have been canceled. The local PBS channel would have refused my membership.

"But what else can I think? If any of those people had spent the last thirty years the way we have, they'd have arrived at the same conclusion. I didn't come to this answer easily, Jessica, you know that. You know how I was. I never had any faith in anything I hadn't witnessed myself. I didn't even believe in the existence of George Washington, let alone first principles. But there comes a time when a scientist must accept the most unappealing explanation, if it is the only one left that fits the facts."

It made no difference to Gillette whether or not he was correct, whether he had investigated a significant number of worlds to substantiate his conclusion. He had had to abandon, one by one, all of his prejudices, and made at last a leap of faith. He knew what seemed to him to be the truth, not through laboratory experiments but by an impulse he had never felt before.

For a few days he felt comfortable with the idea. Life had been created on Earth for whatever reasons, and nowhere else. Each planet devoid of life that Gillette discovered became from then on a confirming instance of this hypothesis. But then, one night, it occurred to him how horribly he had cursed himself. If Earth were the only home of life, why was Gillette hurtling farther and farther from that place, farther from where he too had been made, farther from where he was supposed to be?

What had he done to himself—and to Jessica?

"My impartiality failed me, sweetheart," he said to her disconsolately. "If I could have stayed cold and objective, at least I would have had peace of mind. I would never have known how I damned both of us. But I couldn't; the impartiality was a lie, from the very beginning. As soon as we went to measure something, our humanity got in the way. We couldn't be passive observers of the universe, because we're alive and we're people and we think and feel. And so we were doomed to learn the truth eventually, and we were doomed to suffer because of it." He wished Jessica were still alive, to comfort him as she had so many other times. He had felt isolated before, but it had never been so bad. Now he understood the ultimate meaning of alienation—a separation from his world and the force that had created it. He wasn't supposed to be here, wherever it was. He belonged on Earth, in the midst of life. He stared out through the port, and the infinite blackness seemed to enter into him, merging with his mind and spirit. He felt the awful coldness in his soul.

For a while Gillette was incapacitated by his emotions. When Jessica died, he had bottled up his grief; he had never really permitted himself the luxury of mourning her. Now, with the added weight of his new convictions, her loss struck him again, harder than ever before. He allowed the machines around him to take complete control of the mission in addition to his well-being. He watched the stars shine in the darkness as the ship fell on through real space. He stroked Benny's thick gray fur and remembered everything he had so foolishly abandoned.

In the end it was Benny that pulled Gillette through. Between strokes the man's hand stopped in midair; Gillette experienced a flash of insight, what the oriental philosophers call satori, a moment of diamond-like clarity. He knew intuitively that he had made a mistake that had led him into self-pity. If life had been created on Earth, then all living things were a part of that creation, wherever they might be. Benny, the gray-haired cat, was a part of it, even locked into this tin can between the stars. Gillette himself was a part, wherever he traveled. That creation was just as present in the spacecraft as on Earth itself: it had been foolish for Gillette to think that he ever could separate himself from it—which was just what Jessica had always told him.

"Benny!" said Gillette, a tear streaking his wrinkled cheek. The cat observed him benevolently. Gillette felt a pleasant warmth overwhelm him as he was released at last from his loneliness. "It was all just a fear of death," he whispered. "I was just afraid to die. I wouldn't have believed it! I thought I was beyond all that. It feels good to be free of it."

And when he looked out again at the wheeling stars, the galaxy no longer seemed empty and black, but vibrant and thrilling with a creative energy. He knew that what he felt could not be shaken, even if the next world he visited was a lush garden of life—that would not change a thing, because his belief was no longer based on numbers and facts, but on a stronger sense within him.

* * *

It made no difference at all where Gillette was headed, what stars he would visit: wherever he went, he understood at last, he was going home.

[End]

---------------

"One" is copyright © 1995 by the Estate of George Alec Effinger and is reprinted here by permission of Barbara Hambly and the GAE Estate. The story was originally published in New Legends, edited by Greg Bear (Legend Press UK, 1995), and is currently available in the short story collection George Alec Effinger Live! from Planet Earth (Golden Gryphon Press, 2005).

(Golden Gryphon Press, 2005).

George Alec Effinger completed the Clarion class of 1970, and had three stories in the first Clarion anthology, edited by Robin Scott Wilson (1971). Though his first novel, science fiction/fantasy pastiche What Entropy Means to Me (1972), was a Nebula Award nominee, his finest novels are the noir, hardboiled, near-future cyberpunk "Budayeen" series: Hugo and Nebula finalist When Gravity Fails (1987), Hugo finalist A Fire in the Sun (1989), and The Exile Kiss (1991). Following the example of his first mentors, Damon Knight and Kate Wilhelm, Effinger helped other New Orleans writers through sf/fantasy writing courses at UNO's Metropolitan College from the late 1980s to 1996, and a monthly writing workshop he founded in 1988, which continues to meet regularly. After a lifetime filled with chronic pain and chronic illness, he died peacefully in his sleep in New Orleans on April 27, 2002.

by George Alec Effinger

[Continued from Part 2]

"I have strange thoughts, Jessica," he admitted to her, one day during their ninth year of exploration. "They just come into my head now and then. At first I didn't pay any attention at all. Then, after a while, I noticed that I was paying attention, even though when I stopped to analyze them I could see the ideas were still foolish."

"What kind of thoughts?" she asked. They prepared the landing craft to take them down to a large, ruddy world.

Gillette checked both pressure suits and stowed them aboard the lander. "Sometimes I get the feeling that there aren't any other people anywhere, that they were all the invention of my imagination. As if we never came from Earth, that home and everything I recall are just delusions and false memories. As if we've always been on this ship, forever and ever, and we're absolutely alone in the whole universe." As he spoke, he gripped the heavy door of the lander's airlock until his knuckles turned white. He felt his heart speeding up, he felt his mouth going dry, and he knew that he was about to have another anxiety attack.

"It's all right, Leslie," said Jessica soothingly. "Think back to the time we had together at home. That couldn't be a lie."

Gillette's eyes opened wider. For a moment he had difficulty breathing. "Yes," he whispered, "it could be a lie. You could be a hallucination, too." He began to weep, seeing exactly where his ailing mind was leading him.

Jessica held him while the attack worsened and then passed away. In a few moments he had regained his usual sensible outlook. "This mission is much tougher than I thought it would be," he whispered.

Jessica kissed his cheek. "We have to expect some kind of problems after all these years," she said. "We never planned on it taking this long."

The system they were in consisted of another class-M star and twelve planets. "A lot of work, Jessica," he said, brightening a little at the prospect. "It ought to keep us busy for a couple of weeks. That's better than falling through null space."

"Yes, dear," she said. "Have you started thinking of names yet?" That was becoming the most tedious part of the mission—coming up with enough new names for all the stars and their satellites. After eight thousand systems, they had exhausted all the mythological and historical and geographical names they could remember. They now took turns, naming planets after baseball players and authors and film stars.

They were going down to examine a desert world they had named Rick, after the character in Casablanca. Even though it was unlikely that it would be suitable for life, they still needed to examine it firsthand, just on the off chance, just in case, just for ducks, as Gillette's mother used to say.

That made him pause, a quiet smile on his lips. He hadn't thought of that expression in years. That was a critical point in Gillette's voyage; never again, while Jessica was with him, did he come so close to losing his mental faculties. He clung to her and to his memories as a shield against the cold and destructive forces of the vast emptiness of space.

Once more the years slipped by. The past blurred into an indecipherable haze, and the future did not exist. Living in the present was at once the Gillettes' salvation and curse. They spent their time among routines and changeless duties that were no more tedious than what they had known on Earth, but no more exciting either.

As their shared venture neared its twentieth year, the great disaster befell Gillette: on an unnamed world hundreds of light-years from Earth, on a rocky hill overlooking a barren sandstone valley, Jessica Gillette died. She bent over to collect a sample of soil; a worn seam in her pressure suit parted; there was a sibilant warning of gases passing through the lining, into the suit. She fell to the stony ground, dead. Her husband watched her die, unable to give her any help, so quickly did the poison kill her. He sat beside her as the planet's day turned to night, and through the long, cold hours until dawn.

He buried her on that world, which he named Jessica, and left her there forever. He set out a transmission gate in orbit around the world, finished his survey of the rest of the system, and went on to the next star. He was consumed with grief, and for many days he did not leave his bed.

One morning Benny, the kitten, scrabbled up beside Gillette. The kitten had not been fed in almost a week. "Benny," murmured the lonely man, "I want you to realize something. We can't get home. If I turned this ship around right this very minute and powered home all the way through null space, it would take twenty years. I'd be in my seventies if I lived long enough to see Earth. I never expected to live that long." From then on, Gillette performed his duties in a mechanical way, with none of the enthusiasm he had shared with Jessica. There was nothing else to do but go on, and so he did, but the loneliness clung to him like a shadow of death.

He examined his results, and decided to try to make a tentative hypothesis. "It's unusual data, Benny," he said. "There has to be some simple explanation. Jessica always argued that there didn't have to be any explanation at all, but now I'm sure there must be. There has to be some meaning behind all of this, somewhere. Now tell me, why haven't we found Indication Number One of life on any of these twenty-odd thousand worlds we've visited?"

Benny didn't have much to suggest at this point. He followed Gillette with his big yellow eyes as the man walked around the room. "I've gone over this before," said Gillette, "and the only theories I come up with are extremely hard to live with. Jessica would have thought I was crazy for sure. My friends on Earth would have a really difficult time even listening to them, Benny, let alone seriously considering them. But in an investigation like this, there comes a point when you have to throw out all the predicted results and look deep and long at what has actually occurred. This isn't what I wanted, you know. It sure isn't what Jessica and I expected. But it is what happened."

Gillette sat down at his desk. He thought for a moment about Jessica, and he was brought to the verge of tears. But he thought about how he had dedicated the remainder of his life to her, and to her dream of finding an answer at one of the stellar systems yet to come.

He devoted himself to getting that answer for her. The one blessing in all the years of disappointment was that the statistical data were so easy to comprehend. He didn't need a computer to help in arranging the information: there was just one long, long string of zeros. "Science is built on theories," thought Gillette. "Some theories may be untestable in actual practice, but are accepted because of an overwhelming preponderance of empirical data. For instance, there may not actually exist any such thing as gravity; it may be that things have been falling down consistently because of some outrageous statistical quirk. Any moment now things may start to fall up and down at random, like pennies landing heads or tails. And then the Law of Gravity will have to be amended."

That was the first, and safest, part of his reasoning. Next came the feeling that there was one overriding possibility that would adequately account for the numbing succession of lifeless planets. "I don't really want to think about that yet," he murmured, speaking to Jessica's spirit. "Next week, maybe. I think we'll visit a couple more systems first."

And he did. There were seven planets around an M-class star, and then a G star with eleven, and a K star with fourteen; all the worlds were impact-cratered and pitted and smoothed with lava flow. Gillette held Benny in his lap after inspecting the three systems. "Thirty-two more planets," he said. "What's the grand total now?" Benny didn't know.

Gillette didn't have anyone with whom to debate the matter. He could not consult scientists on Earth; even Jessica was lost to him. All he had was his patient gray cat, who couldn't be looked to for many subtle contributions. "Have you noticed," asked the man, "that the farther we get from Earth, the more homogeneous the universe looks?" If Benny didn't understand the word homogeneous, he didn't show it. "The only really unnatural thing we've seen in all these years has been Earth itself. Life on Earth is the only truly anomalous factor we've witnessed in twenty years of exploration. What does that mean to you?"

At that point, it didn't mean anything to Benny, but it began to mean something to Gillette. He shrugged. "None of my friends were willing to consider even the possibility that Earth might be alone in the universe, that there might not be anything else alive anywhere in all the infinite reaches of space. Of course, we haven't looked at much of those infinite reaches, but going zero for twenty-three thousand means that something unusual is happening." When the Gillettes had left Earth two decades before, prevailing scientific opinion insisted that life had to be out there somewhere, even though there was no proof, either directly or indirectly. There had to be life; it was only a matter of stumbling on it. Gillette looked at the old formula, still hanging where it had been throughout the whole voyage. "If one of those factors is zero," he thought, "then the whole product is zero. Which factor could it be?" There was no hint of an answer, but that particular question was becoming less important to Gillette all the time.

* * *

And so it had come down to this: Year 30 and still outward bound. The end of Gillette's life was somewhere out there in the black stillness. Earth was a pale memory, less real now than last night's dreams. Benny was an old cat, and soon he would die as Jessica had died, and Gillette would be absolutely alone. He didn't like to think about that, but the notion intruded on his consciousness again and again.

Another thought arose just as often. It was an irrational thought, he knew, something he had scoffed at thirty years before. His scientific training led him to examine ideas by the steady, cold light of reason, but this new concept would not hold still for such a mechanical inspection.

He began to think that perhaps Earth was alone in the universe, the only planet among billions to be blessed with life. "I have to admit again that I haven't searched through a significant fraction of all the worlds in the galaxy," he said, as if he were defending his feelings to Jessica. "But I'd be a fool if I ignored thirty years of experience. What does it mean, if I say that Earth is the only planet with life? It isn't a scientific or mathematical notion. Statistics alone demand other worlds with some form of life. But what can overrule such a biological imperative?" He waited for a guess from Benny; none seemed to be forthcoming. "Only an act of faith," murmured Gillette. He paused, thinking that he might hear a trill of dubious laughter from Jessica's spirit, but there was only the humming, ticking silence of the spacecraft.

"A single act of creation, on Earth," said Gillette. "Can you imagine what any of the people at the university would have said to that? I wouldn't have been able to show my face around there again. They would have revoked every credential I had. My subscription to Science would have been canceled. The local PBS channel would have refused my membership.

"But what else can I think? If any of those people had spent the last thirty years the way we have, they'd have arrived at the same conclusion. I didn't come to this answer easily, Jessica, you know that. You know how I was. I never had any faith in anything I hadn't witnessed myself. I didn't even believe in the existence of George Washington, let alone first principles. But there comes a time when a scientist must accept the most unappealing explanation, if it is the only one left that fits the facts."

It made no difference to Gillette whether or not he was correct, whether he had investigated a significant number of worlds to substantiate his conclusion. He had had to abandon, one by one, all of his prejudices, and made at last a leap of faith. He knew what seemed to him to be the truth, not through laboratory experiments but by an impulse he had never felt before.

For a few days he felt comfortable with the idea. Life had been created on Earth for whatever reasons, and nowhere else. Each planet devoid of life that Gillette discovered became from then on a confirming instance of this hypothesis. But then, one night, it occurred to him how horribly he had cursed himself. If Earth were the only home of life, why was Gillette hurtling farther and farther from that place, farther from where he too had been made, farther from where he was supposed to be?

What had he done to himself—and to Jessica?

"My impartiality failed me, sweetheart," he said to her disconsolately. "If I could have stayed cold and objective, at least I would have had peace of mind. I would never have known how I damned both of us. But I couldn't; the impartiality was a lie, from the very beginning. As soon as we went to measure something, our humanity got in the way. We couldn't be passive observers of the universe, because we're alive and we're people and we think and feel. And so we were doomed to learn the truth eventually, and we were doomed to suffer because of it." He wished Jessica were still alive, to comfort him as she had so many other times. He had felt isolated before, but it had never been so bad. Now he understood the ultimate meaning of alienation—a separation from his world and the force that had created it. He wasn't supposed to be here, wherever it was. He belonged on Earth, in the midst of life. He stared out through the port, and the infinite blackness seemed to enter into him, merging with his mind and spirit. He felt the awful coldness in his soul.

For a while Gillette was incapacitated by his emotions. When Jessica died, he had bottled up his grief; he had never really permitted himself the luxury of mourning her. Now, with the added weight of his new convictions, her loss struck him again, harder than ever before. He allowed the machines around him to take complete control of the mission in addition to his well-being. He watched the stars shine in the darkness as the ship fell on through real space. He stroked Benny's thick gray fur and remembered everything he had so foolishly abandoned.

In the end it was Benny that pulled Gillette through. Between strokes the man's hand stopped in midair; Gillette experienced a flash of insight, what the oriental philosophers call satori, a moment of diamond-like clarity. He knew intuitively that he had made a mistake that had led him into self-pity. If life had been created on Earth, then all living things were a part of that creation, wherever they might be. Benny, the gray-haired cat, was a part of it, even locked into this tin can between the stars. Gillette himself was a part, wherever he traveled. That creation was just as present in the spacecraft as on Earth itself: it had been foolish for Gillette to think that he ever could separate himself from it—which was just what Jessica had always told him.

"Benny!" said Gillette, a tear streaking his wrinkled cheek. The cat observed him benevolently. Gillette felt a pleasant warmth overwhelm him as he was released at last from his loneliness. "It was all just a fear of death," he whispered. "I was just afraid to die. I wouldn't have believed it! I thought I was beyond all that. It feels good to be free of it."

And when he looked out again at the wheeling stars, the galaxy no longer seemed empty and black, but vibrant and thrilling with a creative energy. He knew that what he felt could not be shaken, even if the next world he visited was a lush garden of life—that would not change a thing, because his belief was no longer based on numbers and facts, but on a stronger sense within him.

* * *

It made no difference at all where Gillette was headed, what stars he would visit: wherever he went, he understood at last, he was going home.

[End]

---------------

"One" is copyright © 1995 by the Estate of George Alec Effinger and is reprinted here by permission of Barbara Hambly and the GAE Estate. The story was originally published in New Legends, edited by Greg Bear (Legend Press UK, 1995), and is currently available in the short story collection George Alec Effinger Live! from Planet Earth

(Golden Gryphon Press, 2005).

(Golden Gryphon Press, 2005).George Alec Effinger completed the Clarion class of 1970, and had three stories in the first Clarion anthology, edited by Robin Scott Wilson (1971). Though his first novel, science fiction/fantasy pastiche What Entropy Means to Me (1972), was a Nebula Award nominee, his finest novels are the noir, hardboiled, near-future cyberpunk "Budayeen" series: Hugo and Nebula finalist When Gravity Fails (1987), Hugo finalist A Fire in the Sun (1989), and The Exile Kiss (1991). Following the example of his first mentors, Damon Knight and Kate Wilhelm, Effinger helped other New Orleans writers through sf/fantasy writing courses at UNO's Metropolitan College from the late 1980s to 1996, and a monthly writing workshop he founded in 1988, which continues to meet regularly. After a lifetime filled with chronic pain and chronic illness, he died peacefully in his sleep in New Orleans on April 27, 2002.

Published on July 21, 2012 15:10

July 19, 2012

"One" by George Alec Effinger (Part 2 of 3)

One

by George Alec Effinger

[Continued from Part 1]

He remembered how excited they had been about the mission, some thirty years before. He and Jessica had put in their application, and they had been chosen for reasons Gillette had not fully understood. "My father thinks that anyone who wants to go chasing across the galaxy for the rest of his life must be a little crazy," said Jessica.

Gillette smiled. "A little unbalanced, maybe, but not crazy."

They were lying in the grass behind their house, looking up into the night sky, wondering which of the bright diamond stars they would soon visit. The project seemed like a wonderful vacation from their grief, an opportunity to examine their lives and their relationship without the million remembrances that tied them to the past. "I told my father that it was a marvelous opportunity for us," she said. "I told him that from a scientific point of view, it was the most exciting possibility we could ever hope for."

"Did he believe you?"

"Look, Leslie, a shooting star. Make a wish. No, I don't think he believed me. He said the project's board of governors agreed with him and the only reason we've been selected is that we're crazy or unbalanced or whatever in just the right ways."

Gillette tickled his wife's ear with a long blade of grass. "Because we might spend the rest of our lives staring down at stars and worlds."

"I told him five years at the most, Leslie. Five years. I told him that as soon as we found anything we could definitely identify as living matter, we'd turn around and come home. And if we have any kind of luck, we might see it in one of our first stops. We may be gone only a few months or a year."

"I hope so," said Gillette. They looked into the sky, feeling it press down on them with a kind of awesome gravity, as if the infinite distances had been converted to mass and weight. Gillette closed his eyes. "I love you," he whispered.

"I love you, too, Leslie," murmured Jessica. "Are you afraid?"

"Yes."

"Good," she said. "I might have been afraid to go with you if you weren't worried, too. But there's nothing to be afraid of. We'll have each other, and it'll be exciting. It will be more fun than spending the next couple of years here, doing the same thing, giving lectures to grad students and drinking sherry with the Nobel crowd."

Gillette laughed. "I just hope that when we get back, someone remembers who we are. I can just see us spending two years going out and coming back, and nobody even knows what the project was all about."

Their good-bye to her father was more difficult. Mr. Reid was still not sure why they wanted to leave Earth. "A lot of young people suffer a loss, the way you have," he said. "But they go on somehow. They don't just throw their lives away."

"We're not throwing anything away," said Jessica. "Dad, I guess you'd have to be a biologist to understand. There's more excitement in the chance of discovering life somewhere out there than in anything we might do if we stayed here. And we won't be gone long. It's field work, the most challenging kind. Both of us have always preferred that to careers at the chalkboards in some university."

Reid shrugged and kissed his daughter. "If you're sure," was all he had to say. He shook hands with Gillette.

Jessica looked up at the massive spacecraft. "I guess we are," she said. There was nothing more to do or say. They left Earth not many hours later, and they watched the planet dwindle in the ports and on the screens.

The experience of living on the craft was strange at first, but they quickly settled into routines. They learned that while the idea of interstellar flight was exciting, the reality was duller than either could have imagined. The two kittens had no trouble adjusting, and the Gillettes were glad for their company. When the craft was half a million miles from Earth, the computer slipped it into null space, and they were truly isolated for the first time.

It was terrifying. There was no way to communicate with Earth while in null space. The craft became a self-contained little world, and in dangerous moments when Gillette allowed his imagination too much freedom, the silent emptiness around him seemed like a new kind of insanity or death. Jessica's presence calmed him, but he was still grateful when the ship came back into normal space, at the first of their unexplored stellar systems.

Their first subject was a small, dim, class-M star, the most common type in the galaxy, with only two planetary bodies and a lot of asteroidal debris circling around it. "What are we going to name the star, dear?" asked Jessica. They both looked at it through the port, feeling a kind of parental affection.

Gillette shrugged. "I thought it would be easier if we stuck to the mythological system they've been using at home."

"That's a good idea, I guess. We've got one star with two little planets wobbling around it."

"Didn't Apollo have... No, I'm wrong. I thought—"

Jessica turned away from the port. "It reminds me of Odin and his two ravens."

"He had two ravens?"

"Sure," said Jessica, "Thought and Memory. Hugin and Munin."

"Fine. We'll name the star Odin, and the planets whatever you just said. I'm sure glad I have you. You're a lot better at this than I am."

Jessica laughed. She looked forward to exploring the planets. It would be the first break they had in the monotony of the journey. Neither Leslie nor Jessica anticipated finding life on the two desolate worlds, but they were glad to give them a thorough examination. They wandered awe-struck over the bleak, lonely landscapes of Hugin and Munin, completing their tests, and at last returned to their orbiting craft. They sent their findings back to Earth, set out the first of the transmission gates, and, not yet feeling very disappointed, left the Odin system. They both felt that they were in contact with their home, regardless of the fact that their message would take a long time to reach Earth, and they were moving away too quickly ever to receive any. But they both knew that if they wanted, they could still turn around and head back to Earth.

Their need to know drove them on. The loneliness had not yet become unbearable. The awful fear had not yet begun.

The gates were for the use of the people who followed the Gillettes into the unsettled reaches of the galaxy; they could be used in succession to travel outward, but the travelers couldn't return through them. They were like ostrich eggs filled with water and left by natives in the African desert; they were there to make the journey safer and more comfortable for others, to enable the others to travel even farther.

Each time the Gillettes left one star system for another, through null space, they put a greater gulf of space and time between themselves and the world of their birth. "Sometimes I feel very strange," admitted Gillette, after they had been outbound for more than two years. "I feel as if any contact we still have with Earth is an illusion, something we've invented just to maintain our sanity. I feel like we're donating a large part of our lives to something that might never benefit anyone."

Jessica listened somberly. She had had the same feelings, but she hadn't wanted to let her husband know. "Sometimes I think that the life in the university classroom is the most desirable thing in the world. Sometimes I damn myself for not seeing that before. But it doesn't last long. Every time we go down to a new world, I still feel the same hope. It's only the weeks in null space that get to me. The alienation is so intense."

Gillette looked at her mournfully. "What does it really matter if we do discover life?" he asked.

She looked at him in shocked silence for a moment. "You don't really mean that," she said at last.

Gillette's scientific curiosity rescued him, as it had more than once in the past. "No," he said softly, "I don't. It does matter." He picked up the three kittens from Ethyl's litter. "Just let me find something like these waiting on one of these endless planets, and it will all be worthwhile."

Months passed, and the Gillettes visited more stars and more planets, always with the same result. After three years they were still rocketing away from Earth. The fourth year passed, and the fifth. Their hope began to dwindle.

"It bothers me just a little," said Gillette as they sat beside a great gray ocean, on a world they had named Carraway. There was a broad beach of pure white sand backed by high dunes. Waves broke endlessly and came to a frothy end at their feet. "I mean, that we never see anybody behind us, or hear anything. I know it's impossible, but I used to have this crazy dream that somebody was following us through the gates and then jumped ahead of us through null space. Whoever it was waited for us at some star we hadn't got to yet."

Jessica made a flat mound of wet sand. "This is just like Earth, Leslie," she said. "If you don't notice the chartreuse sky. And if you don't think about how there isn't any grass in the dunes and no shells on the beach. Why would somebody follow us like that?"

Gillette lay back on the clean, white sand and listened to the pleasant sound of the surf. "I don't know," he said. "Maybe there had been some absurd kind of life on one of those planets we checked out years ago. Maybe we made a mistake and overlooked something, or misread a meter or something. Or maybe all the nations on Earth had wiped themselves out in a war and I was the only living human male and the lonely women of the world were throwing a party for me."

"You're crazy, honey," said Jessica. She flipped some damp sand onto the legs of his pressure suit.

"Maybe Christ had come back and felt the situation just wasn't complete without us, too. For a while there, every time we bounced back into normal space around a star, I kind of half-hoped to see another ship, waiting." Gillette sat up again. "It never happened, though."

"I wish I had a stick," said Jessica. She piled more wet sand on her mound, looked at it for a few seconds, and then looked up at her husband. "Could there be something happening at home?" she asked.

"Who knows what's happened in these five years? Think of all we've missed, sweetheart. Think of the books and the films, Jessie. Think of the scientific discoveries we haven't heard about. Maybe there's peace in the Mideast and a revolutionary new source of power and a black woman in the White House. Maybe the Cubs have won a pennant, Jessie. Who knows?"

"Don't go overboard, dear," she said. They stood and brushed off the sand that clung to their suits. Then they started back toward the landing craft.

Onboard the orbiting ship an hour later, Gillette watched the cats. They didn't care anything about the Mideast; maybe they had the right idea. "I'll tell you one thing," he said to his wife. "I'll tell you who does know what's been happening. The people back home know. They know all about everything. The only thing they don't know is what's going on with us, right now. And somehow I have the feeling that they're living easier with their ignorance than I am with mine." The kitten that would grow up to be Benny's mother tucked herself up into a neat little bundle and fell asleep.

"You're feeling cut off," said Jessica.

"Of course I am," said Gillette. "Remember what you used to say to me? Before we were married, when I told you I only wanted to go on with my work, and you told me that one human being was no human being? Remember? You were always saying things like that, just so I'd have to ask you what the hell you were talking about. And then you'd smile and deliver some little story you had all planned out. I guess it made you happy. So you said, 'One human being is no human being,' and I said, 'What does that mean?' and you went on about how if I were going to live my life all alone, I might as well not live it at all. I can't remember exactly the way you put it. You have this crazy way of saying things that don't have the least little bit of logic to them but always make sense. You said I figured I could sit in my ivory tower and look at things under a microscope and jot down my findings and send out little announcements now and then about what I'm doing and how I'm feeling and I shouldn't be surprised if nobody gives a damn. You said that I had to live among people, that no matter how hard I tried, I couldn't get away from it. And that I couldn't climb a tree and decide I was going to start my own new species. But you were wrong, Jessica. You can get away from people. Look at us."

The sound of his voice was bitter and heavy in the air. "Look at me," he murmured. He looked at his reflection and it frightened him. He looked old; worse than that, he looked just a little demented. He turned away quickly, his eyes filling with tears.

"We're not truly cut off," she said softly. "Not as long as we're together."

"Yes," he said, but he still felt set apart, his humanity diminishing with the passing months. He performed no function that he considered notably human. He read meters and dials and punched buttons; machines could do that, animals could be trained to do the same. He felt discarded, like a bad spot on a potato, cut out and thrown away.

Jessica prevented his depression from deepening into madness. He was far more susceptible to the effects of isolation than she. Their work sustained Jessica, but it only underscored their futility for her husband.

* * *

[Part 3 forthcoming]

---------------

"One" is © 1995 by the Estate of George Alec Effinger and is reprinted here by permission of Barbara Hambly and the GAE Estate. The story was originally published in New Legends, edited by Greg Bear (Legend Press UK, 1995) and is currently available in the short story collection George Alec Effinger Live! from Planet Earth (Golden Gryphon Press, 2005).

(Golden Gryphon Press, 2005).

by George Alec Effinger

[Continued from Part 1]

He remembered how excited they had been about the mission, some thirty years before. He and Jessica had put in their application, and they had been chosen for reasons Gillette had not fully understood. "My father thinks that anyone who wants to go chasing across the galaxy for the rest of his life must be a little crazy," said Jessica.

Gillette smiled. "A little unbalanced, maybe, but not crazy."

They were lying in the grass behind their house, looking up into the night sky, wondering which of the bright diamond stars they would soon visit. The project seemed like a wonderful vacation from their grief, an opportunity to examine their lives and their relationship without the million remembrances that tied them to the past. "I told my father that it was a marvelous opportunity for us," she said. "I told him that from a scientific point of view, it was the most exciting possibility we could ever hope for."

"Did he believe you?"

"Look, Leslie, a shooting star. Make a wish. No, I don't think he believed me. He said the project's board of governors agreed with him and the only reason we've been selected is that we're crazy or unbalanced or whatever in just the right ways."

Gillette tickled his wife's ear with a long blade of grass. "Because we might spend the rest of our lives staring down at stars and worlds."

"I told him five years at the most, Leslie. Five years. I told him that as soon as we found anything we could definitely identify as living matter, we'd turn around and come home. And if we have any kind of luck, we might see it in one of our first stops. We may be gone only a few months or a year."

"I hope so," said Gillette. They looked into the sky, feeling it press down on them with a kind of awesome gravity, as if the infinite distances had been converted to mass and weight. Gillette closed his eyes. "I love you," he whispered.

"I love you, too, Leslie," murmured Jessica. "Are you afraid?"

"Yes."

"Good," she said. "I might have been afraid to go with you if you weren't worried, too. But there's nothing to be afraid of. We'll have each other, and it'll be exciting. It will be more fun than spending the next couple of years here, doing the same thing, giving lectures to grad students and drinking sherry with the Nobel crowd."

Gillette laughed. "I just hope that when we get back, someone remembers who we are. I can just see us spending two years going out and coming back, and nobody even knows what the project was all about."

Their good-bye to her father was more difficult. Mr. Reid was still not sure why they wanted to leave Earth. "A lot of young people suffer a loss, the way you have," he said. "But they go on somehow. They don't just throw their lives away."