Victor A. Davis's Blog: Mediascover

October 19, 2019

20/20 Challenge

Every year I participate in Goodreads’ Reading Challenge. For 2020, I’ll be doing something a bit different. I’ll be reading no new books for the whole year. Instead I’ve collected many of my all-time favorites and committed to re-reads only, because (wait for it) hindsight is 20/20 and I’m interested in exploring the headspace of re-discovery, particularly of books I read and fell in love with a very long time ago.

While probably impossible to create a definitive favorites list, and improbable to actually get my hands on all of them and read them all in a year, this is going to be a fuzzy challenge. Rather than a hard number, the goal is the concept: To reach back in time, pan through the silt for the nuggets, and create a space for myself to wander among my all time favorite worlds, characters, and writing styles for one whole year. The physical list will probably change as I go, but here’s where it stands as of this writing:

- Jonathan Livingston Seagull by Richard Bach

- Inferno by Dante Alighieri

- The Neverending Story by Michael Ende

- The Snow Child by Eowyn Ivey

...

Read More...

While probably impossible to create a definitive favorites list, and improbable to actually get my hands on all of them and read them all in a year, this is going to be a fuzzy challenge. Rather than a hard number, the goal is the concept: To reach back in time, pan through the silt for the nuggets, and create a space for myself to wander among my all time favorite worlds, characters, and writing styles for one whole year. The physical list will probably change as I go, but here’s where it stands as of this writing:

- Jonathan Livingston Seagull by Richard Bach

- Inferno by Dante Alighieri

- The Neverending Story by Michael Ende

- The Snow Child by Eowyn Ivey

...

Read More...

Published on October 19, 2019 10:55

•

Tags:

reading-challenge

November 30, 2018

Pan and the Observer

Many books feature a fascinating, enigmatic, larger-than-life hero. Think Huckleberry Finn, John Galt, or Atticus Finch. But stories are rarely told through these characters' eyes. They are so larger-than-life, so unrelatable, that the story must be told by a secondary character, someone emotionally conflicted, sensibly grounded, someone "normal," with more in common with the reader. Think Tom Sawyer, Dagny Taggart, or Scout. Taken too far, a poor enough writer can create a blank protagonist, totally void of personality or characteristics, on which the reader can imprint herself in order to follow the book's action.

Consider for a moment the following protagonists compared to their book's heroes:

Tom Sawyer to Huck Finn (Adventures of Tom Sawyer)

Dagny Taggart to John Galt (Atlas Shrugged)

Scout to Atticus Finch (To Kill a Mockingbird)

Narrator to Tyler Durden (Fight Club)

Jack Burden to Willie Stark (All the King's Men)

Nick to Peter Pan (The Child Thief)

Jack & Mabel to Faina (The Snow Child)

Lily to the Boatright Sisters (Secret Life of Bees)

Read on...

Consider for a moment the following protagonists compared to their book's heroes:

Tom Sawyer to Huck Finn (Adventures of Tom Sawyer)

Dagny Taggart to John Galt (Atlas Shrugged)

Scout to Atticus Finch (To Kill a Mockingbird)

Narrator to Tyler Durden (Fight Club)

Jack Burden to Willie Stark (All the King's Men)

Nick to Peter Pan (The Child Thief)

Jack & Mabel to Faina (The Snow Child)

Lily to the Boatright Sisters (Secret Life of Bees)

Read on...

Published on November 30, 2018 16:40

•

Tags:

books, hero-s-journey, heroes, monomyth

December 29, 2017

My Year in Books 2017

This year, my wife and I thru-hiked the Appalachian Trail, 2,189 miles from Northern Georgia to Northern Maine. Before setting out, I had this Huckleberry Finn-esque vision of what this would be like. It was cold when we started mid-February, so I imagined sitting around the fire huddled over our soups, then bundling up in our sleeping bags with a headlamp, reading and writing until we got tired. Come summer, I imagined lazy, two-hour lunch breaks and naptimes, sitting on a rock or fallen log or ledge overlooking some incredible vista or waterfall, reading a book, snacking on trail mix. Allow me to burst the bubble of whoever may also, quite sensibly, have this image. Walking two thousand miles is work. A fifteen mile day leaves you so exhausted that the setting-up-camp routine is the closest you get to decompression. Comically for an environment dominated by young men, sunset is affectionately referred to as "hiker midnight," when eyes get droopy and nearly everyone turns in for bed. We enjoyed maybe six campfires the whole trip: time-consuming, wasteful, unnecessary. All the spare time I never have in my regular life, I thought I'd have out on the trail, and devour books prodigiously. It doesn't happen. By the middle of Virginia, I had even let my journal lapse, thinking that forced, uninspired entries aren't worth it. I read nine books in six months, dismal. Once I got home in August, I read fifteen more through the end of the year.

I started with Deliverance, a good choice, I thought, hiking through the woods of North Georgia, where the book is set. Fortunately, we heard no banjo music. I reread Ender's Game, a good ol' standby and one of my all-time favorites. I found Galileo's Daughter, Girl with the Pearl Earring and Secrets of the Fire King on hostel bookshelves, swapping them out and carrying them with me. I bought The Sixth Extinction in Connecticut, and when we reached Williamstown, Massachusetts for a day of rest, I flipped to the bio page and realized I was reading this Pulitzer-prize-winning author's book in her own hometown! Most people stuck to smartphones out on trail, so to the extent they read anything, it was ebooks, audiobooks, and cached internet articles. I left the tech at home and actually carried my journals and 1-2 books with me, a fact that, if you do any long distance hiking, should certainly shock you. Yes, for the love of books, I always had an extra few pounds of paper on my back.

Stats: 70/30 Male/Female authors (19 vs 8), 8885 pages (296/book), 12 days/book

~Awards~

Best Book of the Year: In Other Words by Jhumpa Lahiri -- So good, I read it twice, once on trail, once back at home when I could dog-ear, highlight, and take notes in it. The language (even translated) is luscious and simple. This is a masterful author at the top of her game bearing her soul.

Worst Book: Unabomber Manifesto by Ted Kasycinski -- Yes, I thought I'd have a peek inside this kook's head. He's a kook.

Most Overrated: March by Geraldine Brooks -- I only made it through the first two chapters, so it's not an objective opinion, but this Pulitzer-prize winner didn't grab me. (Runner-up: The Grapes of Wrath)

Best-Timed Read: Deliverance by James Dickey -- Don't pre-judge. This is a poet trying his hand at prose, absolutely nailing the language and taking you on a breathtaking thriller ride to the edge of survival.

Pinker Award: The Sixth Extinction by Elizabeth Kolbert -- Handily takes this coveted spot as the clearest science book that will change your worldview, in this case, about humans' impact on the biosphere. Runner-up: The Omnivore's Dilemma by Michael Pollan -- I've had this author on my radar for a while now, and he lives up to every expectation. Wile you're at it, search his name on Netflix and check out some great documentaries he's narrated!

I started with Deliverance, a good choice, I thought, hiking through the woods of North Georgia, where the book is set. Fortunately, we heard no banjo music. I reread Ender's Game, a good ol' standby and one of my all-time favorites. I found Galileo's Daughter, Girl with the Pearl Earring and Secrets of the Fire King on hostel bookshelves, swapping them out and carrying them with me. I bought The Sixth Extinction in Connecticut, and when we reached Williamstown, Massachusetts for a day of rest, I flipped to the bio page and realized I was reading this Pulitzer-prize-winning author's book in her own hometown! Most people stuck to smartphones out on trail, so to the extent they read anything, it was ebooks, audiobooks, and cached internet articles. I left the tech at home and actually carried my journals and 1-2 books with me, a fact that, if you do any long distance hiking, should certainly shock you. Yes, for the love of books, I always had an extra few pounds of paper on my back.

Stats: 70/30 Male/Female authors (19 vs 8), 8885 pages (296/book), 12 days/book

~Awards~

Best Book of the Year: In Other Words by Jhumpa Lahiri -- So good, I read it twice, once on trail, once back at home when I could dog-ear, highlight, and take notes in it. The language (even translated) is luscious and simple. This is a masterful author at the top of her game bearing her soul.

Worst Book: Unabomber Manifesto by Ted Kasycinski -- Yes, I thought I'd have a peek inside this kook's head. He's a kook.

Most Overrated: March by Geraldine Brooks -- I only made it through the first two chapters, so it's not an objective opinion, but this Pulitzer-prize winner didn't grab me. (Runner-up: The Grapes of Wrath)

Best-Timed Read: Deliverance by James Dickey -- Don't pre-judge. This is a poet trying his hand at prose, absolutely nailing the language and taking you on a breathtaking thriller ride to the edge of survival.

Pinker Award: The Sixth Extinction by Elizabeth Kolbert -- Handily takes this coveted spot as the clearest science book that will change your worldview, in this case, about humans' impact on the biosphere. Runner-up: The Omnivore's Dilemma by Michael Pollan -- I've had this author on my radar for a while now, and he lives up to every expectation. Wile you're at it, search his name on Netflix and check out some great documentaries he's narrated!

Published on December 29, 2017 07:59

January 11, 2017

My Year in Books: 2016

At the beginning of 2016 I set out to read a book a week. I failed. I read 50 of the 52 books I’d set out to read, but as you may imagine I’m hardly disappointed. Although I read only 4 books more than last year, I read longer books, a total of 12606 pages over last year’s 8903. Although this reflects an average length of only 250 pages, I’m happy with my decision to remain focused on short books, maximizing the variety of my experience. I did a slightly worse job at gender balancing, reading 34 male-authored books vs 16 female-authored as opposed to a 70/30 split last year. Overall I’m pleased with my results and a little wearied. 34 pages a day translates to about an hour of consistent time set aside for the hobby (reading before bed most nights, with the occasional 2-3 hour “curl-up” session). That means I spent 1/24th of my life last year reading books in addition to eating, working, sleeping, etc. That’s pretty substantial, and represents what feels like my realistic upper limit.

[ Read More... ]

[ Read More... ]

Published on January 11, 2017 13:25

November 15, 2016

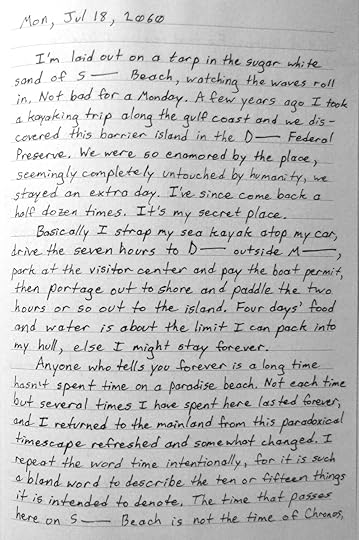

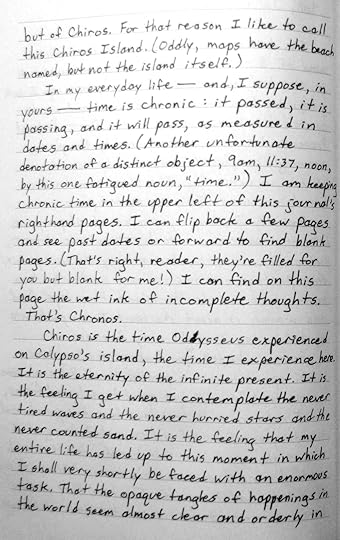

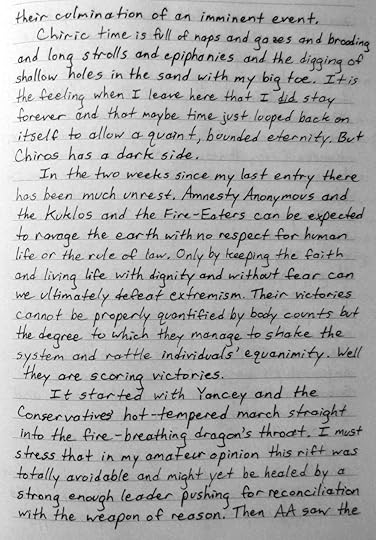

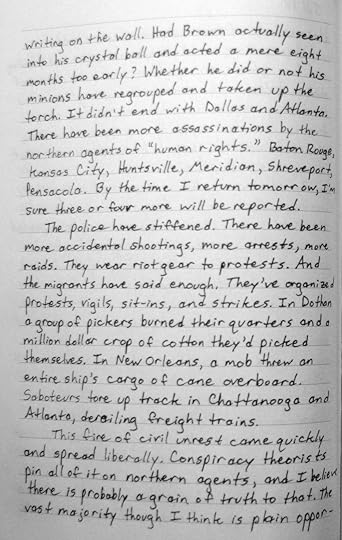

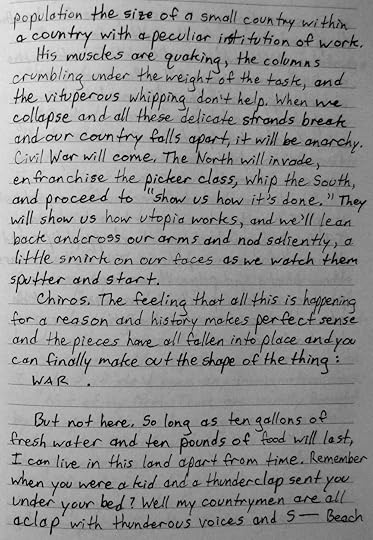

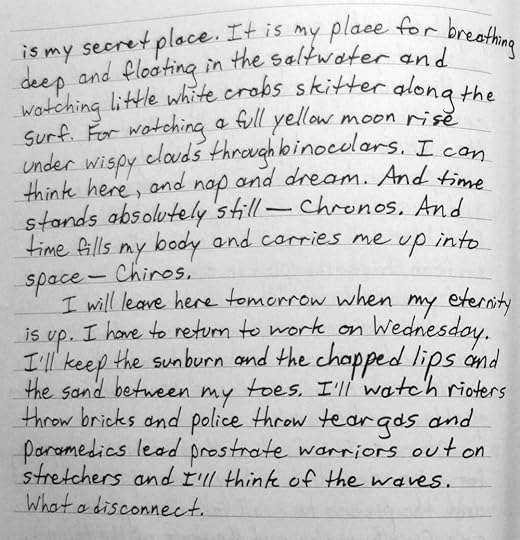

Dreams of Chiros

Published on November 15, 2016 09:02

•

Tags:

wick

October 12, 2016

The Writing Process

Most non-writers probably have a concept of writing as the art of making shit up. Shit that’s meaningful or entertaining, anyway. Some, like myself, disagree. This gets to the heart of the “in there” vs “out there” debate about creativity, best illustrated by mathematics. Are mathematical concepts such as π inventions of the human mind, or discoveries of the real world? If you were to poll mathematicians, most would probably say theirs is the process of discovering real world truths that are already “out there,” and that it takes a creative mind to endeavor on this process. I feel the same way about writing. Stories are not constructions made up out of thin air, constituted only by a writer’s creative thoughts. Unwritten stories already exist in the vast sea of our collective unconscious, and writers are those divers skilled at bringing them up.

The following excerpt from Stephen King’s On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft illustrates this superbly:

I agree with this sentiment because it’s been my experience in reading and writing. When I first read Atlas Shrugged (at the impressionable age of 15) I distinctly felt I’d discovered something, been made aware of an idea’s existence. In similar fashion, Watership Down got me thinking about how much of our psychology we inherited from our animal ancestors. I’ve never been drawn to serial works or “genre fiction,” that which feels like the same basic idea repeated ad nauseam in slightly different garb. And that’s the reason: If the idea is the same, why read 10 reboots of the same book?

This is what draws me to literary fiction. My personal definition of “literary fiction” is “that which does not fall into a genre.” It’s not all I read. I love The Cruelest Miles (nonfiction), Ender's Game (sci-fi), and Free Culture (legal). But East of Eden? The Snow Child? The Shell Collector? To me, there is a direct connection between great writing and its resistance to categorization. Each of my favorite books represent a solitary idea, something unique, original, and intuitive, despite my never having imagined it before reading the book.

When I write, it’s not good enough to write by inspiration. My brain is wired for writing. Every conversation I hold, every movie I watch, every book I read, I’m fictionalizing. I’m imagining spinoff ideas, ideas that would never be put to paper because they’ve already been done. Experiencing others’ fiction is like being led to the spot at which they found their fossil. It’s beautiful and intellectually gratifying, but it’s already dug up. My mind may go off on how I would have dug it up differently, but those thoughts are overshadowed by that satisfying feeling of place, of having planted my feet on these specific coordinates on the landscape of our collective unconscious. What are some of the plots of virgin soil I’ve found, some undug fossils? That’s the ultimate needle to thread. King’s fossil, to me, is an intuitive idea that’s compelling, nuanced, and totally original. The excitement I feel for synthesizing a story comes from the thought that no one else out there thought of this before. Obviously I can’t know this for sure, since it’s impossible to read every book ever written, but I do read extensively. If anybody is qualified to certify an idea as original, it’s an avid reader.

Reading definitely feels like mining, in a way. I’m constantly dredging for new ideas, new ways of thinking of things, burning down my ever-expanding list of “must reads.” Lolita, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, The Child Thief, these are my greatest discoveries, amid a sea of good, bad, and okay books. Writing is like mining too. By living life to the fullest, full of love, travel, food, books, and nature, I am exploring my outer world and my own symbolic inner world. Amid this sea of symbols, some recombine in just the right way to suggest an original story. This is my conception of a muse. “She” is my capacity to recognize a diamond in the rough, a fossil worth digging up, and the experience I have of my outer, surrounding world informs the plot and setting, “getting it out of the ground as intact as possible.”

The following excerpt from Stephen King’s On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft illustrates this superbly:

“When, during the course of an interview for The New Yorker, I told the interviewer (Mark Singer) that I believed stories are found things, like fossils in the ground, he said that he didn’t believe me. I replied that that was fine, as long as he believed that I believe it. And I do. Stories aren’t souvenir tee-shirts or Game Boys. Stories are relics, part of an undiscovered pre-existing world. The writer’s job is to use the tools in his or her toolbox to get as much of each one out of the ground intact as possible. Sometimes the fossil you uncover is small; a seashell. Sometimes it’s enormous, a Tyrannosaurus Rex with all the gigantic ribs and grinning teeth. Either way, short story or thousand page whopper of a novel, the techniques of excavation remain basically the same.”

I agree with this sentiment because it’s been my experience in reading and writing. When I first read Atlas Shrugged (at the impressionable age of 15) I distinctly felt I’d discovered something, been made aware of an idea’s existence. In similar fashion, Watership Down got me thinking about how much of our psychology we inherited from our animal ancestors. I’ve never been drawn to serial works or “genre fiction,” that which feels like the same basic idea repeated ad nauseam in slightly different garb. And that’s the reason: If the idea is the same, why read 10 reboots of the same book?

This is what draws me to literary fiction. My personal definition of “literary fiction” is “that which does not fall into a genre.” It’s not all I read. I love The Cruelest Miles (nonfiction), Ender's Game (sci-fi), and Free Culture (legal). But East of Eden? The Snow Child? The Shell Collector? To me, there is a direct connection between great writing and its resistance to categorization. Each of my favorite books represent a solitary idea, something unique, original, and intuitive, despite my never having imagined it before reading the book.

When I write, it’s not good enough to write by inspiration. My brain is wired for writing. Every conversation I hold, every movie I watch, every book I read, I’m fictionalizing. I’m imagining spinoff ideas, ideas that would never be put to paper because they’ve already been done. Experiencing others’ fiction is like being led to the spot at which they found their fossil. It’s beautiful and intellectually gratifying, but it’s already dug up. My mind may go off on how I would have dug it up differently, but those thoughts are overshadowed by that satisfying feeling of place, of having planted my feet on these specific coordinates on the landscape of our collective unconscious. What are some of the plots of virgin soil I’ve found, some undug fossils? That’s the ultimate needle to thread. King’s fossil, to me, is an intuitive idea that’s compelling, nuanced, and totally original. The excitement I feel for synthesizing a story comes from the thought that no one else out there thought of this before. Obviously I can’t know this for sure, since it’s impossible to read every book ever written, but I do read extensively. If anybody is qualified to certify an idea as original, it’s an avid reader.

Reading definitely feels like mining, in a way. I’m constantly dredging for new ideas, new ways of thinking of things, burning down my ever-expanding list of “must reads.” Lolita, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, The Child Thief, these are my greatest discoveries, amid a sea of good, bad, and okay books. Writing is like mining too. By living life to the fullest, full of love, travel, food, books, and nature, I am exploring my outer world and my own symbolic inner world. Amid this sea of symbols, some recombine in just the right way to suggest an original story. This is my conception of a muse. “She” is my capacity to recognize a diamond in the rough, a fossil worth digging up, and the experience I have of my outer, surrounding world informs the plot and setting, “getting it out of the ground as intact as possible.”

Published on October 12, 2016 07:40

•

Tags:

short-story, writing

October 4, 2016

The Myth of Pure Evil

What does the Joker have in common with Michael Corleone?

Meet my two favorite villains of all time. From a creative writing perspective, I am fascinated by what makes these guys tick. They represent two conflicting ideas of what it means to be “evil,” and they also represent two very different ideas about how the world works.

[more...]

Meet my two favorite villains of all time. From a creative writing perspective, I am fascinated by what makes these guys tick. They represent two conflicting ideas of what it means to be “evil,” and they also represent two very different ideas about how the world works.

[more...]

Published on October 04, 2016 10:15

•

Tags:

evil, psychology, villains

August 14, 2016

Wrapping Up "Better Angels"

Review of The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

by Steven Pinker

(Previously: On Angels' Wings)

(Credit: All block quotes are excerpts from the book.)

Wrapping Up

This book has been about violence: its causes, its forms, its decline. It is only natural to ask, from our modern humanist vantage, “why is there violence?” Yet once these answers are understood, it’s far more difficult to answer “why is there peace?” Most would agree peace is preferable to war, but is that shared universal preference reason in itself for the decline of violence from ancient to modern times? Why do people think we live in the most violent of times, despite the stats? What role do literacy, wealth, trade, technology, cosmopolitanism, tolerance, and self-control play in the reduction of violence over time? Most importantly, where are we headed?

The answers, briefly touched on in this post series, are enough to fill a very thick book. By page 481, I had realized I was reading one of the most influential books I would ever read, and learning a new worldview I’d be incorporating into my own. So I started over on page 1, highlighting and notating for the purpose of summarizing each chapter in this series. I read chapters here and there, interspersed with other books, because I knew that reading a 1341-page tome could burn me out. Luckily for me, on page 1018, chapter 10 closed and the next page started in on footnotes and citations. Surprise! I was finished before I knew what hit me. I picked up this book in February of 2015. Now, in July of the following year, laid out on the beach incidentally, I’m done.

I won’t waste space recapping my 11-post recap series. This is a large book because it contains a lot of information about the human condition, information not taught in history class. I’ve done my best to distill it to these blog posts, which I hope was not folly, but I know it would be folly to try to distill it in a single concluding paragraph. Bottom line is, watch the TED Talk, and read (or skim!) the rest of the posts in this series. I challenge anyone not to be blown away by this evidence-based approach to world history and human psychology. I hope that a handful of people at least make it through this series and pick up the book itself. Its 1000 pages of lucid explanation and shocking facts are sure to challenge you as it challenged me. To think differently, to be less nostalgic and more optimistic, to question assumptions, and to seek out facts to support (or bust!) deeply-held beliefs.

If all of this sounds intriguing, even counter-intuitive, watch Pinker’s TED Talk for a wonderful summary of the book.

(First: Review of the Preface)

by Steven Pinker

(Previously: On Angels' Wings)

(Credit: All block quotes are excerpts from the book.)

Wrapping Up

This book has been about violence: its causes, its forms, its decline. It is only natural to ask, from our modern humanist vantage, “why is there violence?” Yet once these answers are understood, it’s far more difficult to answer “why is there peace?” Most would agree peace is preferable to war, but is that shared universal preference reason in itself for the decline of violence from ancient to modern times? Why do people think we live in the most violent of times, despite the stats? What role do literacy, wealth, trade, technology, cosmopolitanism, tolerance, and self-control play in the reduction of violence over time? Most importantly, where are we headed?

Only preachers and pop singers profess that violence will someday vanish off the face of the earth. A measured degree of violence, even if only held in reserve, will always be necessary in the form of police forces and armies to deter predation or to incapacitate those who cannot be deterred. Yet there is a vast difference between the minimal violence necessary to prevent greater violence and the bolts of fury that an uncalibrated mind is likely to deliver in acts of rough justice.

The answers, briefly touched on in this post series, are enough to fill a very thick book. By page 481, I had realized I was reading one of the most influential books I would ever read, and learning a new worldview I’d be incorporating into my own. So I started over on page 1, highlighting and notating for the purpose of summarizing each chapter in this series. I read chapters here and there, interspersed with other books, because I knew that reading a 1341-page tome could burn me out. Luckily for me, on page 1018, chapter 10 closed and the next page started in on footnotes and citations. Surprise! I was finished before I knew what hit me. I picked up this book in February of 2015. Now, in July of the following year, laid out on the beach incidentally, I’m done.

I won’t waste space recapping my 11-post recap series. This is a large book because it contains a lot of information about the human condition, information not taught in history class. I’ve done my best to distill it to these blog posts, which I hope was not folly, but I know it would be folly to try to distill it in a single concluding paragraph. Bottom line is, watch the TED Talk, and read (or skim!) the rest of the posts in this series. I challenge anyone not to be blown away by this evidence-based approach to world history and human psychology. I hope that a handful of people at least make it through this series and pick up the book itself. Its 1000 pages of lucid explanation and shocking facts are sure to challenge you as it challenged me. To think differently, to be less nostalgic and more optimistic, to question assumptions, and to seek out facts to support (or bust!) deeply-held beliefs.

At least, they say, our ancestors did not have to worry about muggings, school shootings, terrorist attacks, holocausts, world wars, killing fields, napalm, gulags, and nuclear annihilation. Surely no Boeing 747, no antibiotic, no iPod is worth the suffering that modern societies and their technologies can wreak. And here is where unsentimental history and statistical literacy can change our view of modernity. For they show that nostalgia for a peaceable past is the biggest delusion of all.

If all of this sounds intriguing, even counter-intuitive, watch Pinker’s TED Talk for a wonderful summary of the book.

(First: Review of the Preface)

Published on August 14, 2016 10:09

•

Tags:

steven-pinker, the-better-angels-of-our-nature, the-new-peace, violence, war

August 9, 2016

On Angels' Wings

Review of The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

by Steven Pinker, Chapter 10

(Previously: Better Angels)

(Credit: All block quotes are excerpts from the book.)

Chapter 10: On Angels' Wings

“As man advances in civilization, and small tribes are united into larger communities, the simplest reason would tell each individual that he ought to extend his social instincts and sympathies to all the members of the same nation, though personally unknown to him. This point being once reached, there is only an artificial barrier to prevent his sympathies extending to the men of all nations and races.” ~Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man

Fun fact: IQ scores have been steadily rising, at a rate of about 3 points per decade, since standardized tests have been invented. “Mankind is Getting Smarter!” is an easy headline. But is it real?

As you know, “IQ,” or “Intelligence Quotient” is a measure of general intelligence calibrated as such that a score of 100 means “average” and +/- 15 points means roughly “below or above average.” (For the stat-savvy, 15 is the standard deviation.) So, the Flynn effect seems to posit that a person of today’s average intelligence would have been considered “above average” fifty years ago, and vice versa: an person of average intelligence fifty years ago would today be considered “below average.” What’s going on here? Is there a flaw in the testing, or the number crunching, or the sampling? Is “intelligence” a murky, ill-defined concept whose very definition is drifting with the times?

Let’s consider a standard sample question: What do a fox and a rabbit have in common? If you said “they’re both mammals” then congratulations, you would have gotten that question right on a standard IQ test. Why is this a measure of “intelligence”? And if it is, then what is “intelligence”?

Sound like this is hearkening back to earlier posts regarding the book’s themes? IQ tests, whose scores have been drifting upwards decade after decade, “tap abstract, formal reasoning.” They measure one’s ability to detach oneself from “one’s own little world” and consider “hypothetical worlds.” IQ scores and the Flynn effect therefore quantify our capacity for reason and empathy! [insert caveats here] A connection between increasing capacity for empathy and decreasing rates of violence would be tenuous at best, but it’s interesting to consider. Experts tend to explain the Flynn effect in terms of education. Schoolkids learn more about “how to think” in the classrooms of today. That equips them to answer questions like “Cat is to mouse as cow is to what?” better than questions like “What states would you pass through driving due south from Columbus, Ohio?” While both test for a kind of synthesis of knowledge, one taps more into an innate ability than innate knowledge. That ability, that capacity to reason, to abstract, and to empathize (to explore hypothetical worlds) is what is driving IQ scores up. Better and more widespread schooling is probably the main driver. It is worth noting, also, that people are getting better at answering certain kinds of questions, not all questions across the board. It is not “general intelligence” that is necessarily increasing, the innate potential of the human brain, as dictated by genetics.

What other trends, besides education, reason and empathy, have been major driving factors of peace? Pinker details three more: the leviathan, trade, and feminism. Recall from a previous chapter that the leviathan refers to Hobbes’s idea of a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence as a deterrent against infighting. It’s why legal cases are referred to not as “Alice vs Bob” but as “The People” or “The State” vs Bob. In feudal and tribal societies, scores were settled privately which led to bloody cycles of violent vendettas and the kind of “self-help justice” seen in ganglands and warlord & mafia-controlled failed states. The consolidation of power by kings (and their eventual evolution into governments) led to a decrease in this kind of violence by punishing the kind of infighting that suppressed the common wealth. Trade is the other major driver of peace. Plunder is expensive, as is occupation, so when nations lay down there arms in order to trade they share what social scientists call a “peace dividend.” Lastly, the statistics confirm our intuitions that violence is disproportionately dominated by males. There is a large correlation (cause may go both ways!) between peace and women’s rights. More inclusive, egalitarian societies tend to be more peaceful, and more violent societies tend to eschew the rights of women and minority groups.

If all of this sounds intriguing, even counter-intuitive, watch Pinker’s TED Talk for a wonderful summary of the book.

(Next: Wrapping Up)

by Steven Pinker, Chapter 10

(Previously: Better Angels)

(Credit: All block quotes are excerpts from the book.)

Chapter 10: On Angels' Wings

“As man advances in civilization, and small tribes are united into larger communities, the simplest reason would tell each individual that he ought to extend his social instincts and sympathies to all the members of the same nation, though personally unknown to him. This point being once reached, there is only an artificial barrier to prevent his sympathies extending to the men of all nations and races.” ~Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man

Fun fact: IQ scores have been steadily rising, at a rate of about 3 points per decade, since standardized tests have been invented. “Mankind is Getting Smarter!” is an easy headline. But is it real?

As you know, “IQ,” or “Intelligence Quotient” is a measure of general intelligence calibrated as such that a score of 100 means “average” and +/- 15 points means roughly “below or above average.” (For the stat-savvy, 15 is the standard deviation.) So, the Flynn effect seems to posit that a person of today’s average intelligence would have been considered “above average” fifty years ago, and vice versa: an person of average intelligence fifty years ago would today be considered “below average.” What’s going on here? Is there a flaw in the testing, or the number crunching, or the sampling? Is “intelligence” a murky, ill-defined concept whose very definition is drifting with the times?

Let’s consider a standard sample question: What do a fox and a rabbit have in common? If you said “they’re both mammals” then congratulations, you would have gotten that question right on a standard IQ test. Why is this a measure of “intelligence”? And if it is, then what is “intelligence”?

Luria transcribed interviews with Russian peasants in remote parts of the Soviet Union who were given similarities questions like the ones on IQ tests:

Q: What do a fish and a crow have in common?

A: A fish—it lives in water. A crow flies. If the fish just lies on top of the water, the crow would peck at it. A crow can eat a fish but a fish can’t eat a crow.

Q: Could you use one word for them both [such as “animals”]?

A: If you call them “animals,” that wouldn’t be right. A fish isn’t an animal and a crow isn’t either…. A person can eat a fish but not a crow.

Luria’s informants also rejected a purely hypothetical mode of thinking—the stage of cognition that Jean Piaget called formal (as opposed to concrete) operations.

Q: All bears are white where there is always snow. In Novaya Zemlya there is always snow. What color are the bears there?

A: I have seen only black bears and I do not talk of what I have not seen.

Q: But what do my words imply?

A: If a person has not been there he cannot say anything on the basis of words. If a man was 60 or 80 and had seen a white bear there and told me about it, he could be believed.

Flynn remarks, “The peasants are entirely correct. They understand the difference between analytic and synthetic propositions: pure logic cannot tell us anything about facts; only experience can. But this will do them no good on current IQ tests.” That is because current IQ tests tap abstract, formal reasoning: the ability to detach oneself from parochial knowledge of one’s own little world and explore the implications of postulates in purely hypothetical worlds.

Sound like this is hearkening back to earlier posts regarding the book’s themes? IQ tests, whose scores have been drifting upwards decade after decade, “tap abstract, formal reasoning.” They measure one’s ability to detach oneself from “one’s own little world” and consider “hypothetical worlds.” IQ scores and the Flynn effect therefore quantify our capacity for reason and empathy! [insert caveats here] A connection between increasing capacity for empathy and decreasing rates of violence would be tenuous at best, but it’s interesting to consider. Experts tend to explain the Flynn effect in terms of education. Schoolkids learn more about “how to think” in the classrooms of today. That equips them to answer questions like “Cat is to mouse as cow is to what?” better than questions like “What states would you pass through driving due south from Columbus, Ohio?” While both test for a kind of synthesis of knowledge, one taps more into an innate ability than innate knowledge. That ability, that capacity to reason, to abstract, and to empathize (to explore hypothetical worlds) is what is driving IQ scores up. Better and more widespread schooling is probably the main driver. It is worth noting, also, that people are getting better at answering certain kinds of questions, not all questions across the board. It is not “general intelligence” that is necessarily increasing, the innate potential of the human brain, as dictated by genetics.

What other trends, besides education, reason and empathy, have been major driving factors of peace? Pinker details three more: the leviathan, trade, and feminism. Recall from a previous chapter that the leviathan refers to Hobbes’s idea of a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence as a deterrent against infighting. It’s why legal cases are referred to not as “Alice vs Bob” but as “The People” or “The State” vs Bob. In feudal and tribal societies, scores were settled privately which led to bloody cycles of violent vendettas and the kind of “self-help justice” seen in ganglands and warlord & mafia-controlled failed states. The consolidation of power by kings (and their eventual evolution into governments) led to a decrease in this kind of violence by punishing the kind of infighting that suppressed the common wealth. Trade is the other major driver of peace. Plunder is expensive, as is occupation, so when nations lay down there arms in order to trade they share what social scientists call a “peace dividend.” Lastly, the statistics confirm our intuitions that violence is disproportionately dominated by males. There is a large correlation (cause may go both ways!) between peace and women’s rights. More inclusive, egalitarian societies tend to be more peaceful, and more violent societies tend to eschew the rights of women and minority groups.

If all of this sounds intriguing, even counter-intuitive, watch Pinker’s TED Talk for a wonderful summary of the book.

(Next: Wrapping Up)

Published on August 09, 2016 11:03

•

Tags:

steven-pinker, the-better-angels-of-our-nature, the-new-peace, violence, war

July 26, 2016

Better Angels

Review of The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

by Steven Pinker, Chapter 9

(Previously: Inner Demons)

(Credit: All block quotes are excerpts from the book.)

Chapter 9: Better Angels

“[It] cannot be disputed that there is some benevolence, however small, infused into our bosom; some spark of friendship for human kind; some particle of the dove, kneaded into our frame, along with the elements of the wolf and serpent. Let these generous sentiments be supposed ever so weak; let them be insufficient to move even a hand or finger of our body; they must still direct the determinations of our mind, and where every thing else is equal, produce a cool preference of what is useful and serviceable to mankind, above what is pernicious and dangerous.” ~David Hume, An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals

All throughout this book, empathy is touted as the greatest contributor to peace in a society. Adam Smith doubted it. He proposed a charming “Little Finger Paradox” that goes such: If a natural disaster were to befall a foreign people you would probably feel sorry for them but lose no sleep over it, being so far removed from your own daily life. Yet if some personal “disaster” were to befall you, such as losing your little finger in an accident, such a thing would dominate your thinking, your speech, your actions, and sustain a sense of anguish in you for quite some time. Suppose then that you were offered a bargain of sacrificing your little finger in order to save millions from some far-off disaster. Most people would accept such a sacrifice, not necessarily out of a sense of grandiosity, but of reason: one individual’s little finger is worth far less than millions of strangers’ lives. Why the disconnect? His “paradox” asks why our emotions (indifference vs agitation) are so varied from a reasoned comparison. Of course, it’s no paradox at all, it merely highlights the fact that emotion (including sympathy) is a biological function of a self-interested animal, and that reason is something that transcends evolution.

While there are several better angels in the human constitution, Pinker declares reason the king of them all. Reason is what allows us to analyze moral puzzles like the above from a disinterested bird’s eye view before making decisions that affect us personally. In the world of abstract reason, “my little finger” and “a disaster claiming millions of lives” can be represented as “a small loss for X” vs “a great loss for millions of Y” and this abstraction, from “me vs you” and “us vs them” to a generic “X vs Y” is the engine at the heart of empathy. The ability to step outside yourself and see the world through the eyes of those around you (and others far away!) leads to an attitude of “there but for fortune go I.” It is reason, therefore, that underlies the philosophies of secular humanism and classical liberalism. (“Classical” used here to distinguish enlightenment thinking from the modern political use of the word “liberal.”)

What about morality? Most of us have an instinctive understanding of crime and mayhem as being committed by a small group of people driven by motives of pure evil and hatred. In effect, we project our shadow (to borrow a term from Jung) on those we dislike, misunderstand, or are suspicious of, and consider “them” living in a separate world completely cordoned off from our own, living by principles completely antithetical to our own. This is “morality.” The idea that some core set of principles guides the better angels of our natures and those that stray from those principles or were never taught them are unhuman and descend into a life of darkness. Immoral individuals can only be “saved” from darkness by instilling in them the right principles, and if they cannot be saved, they ought to be oppressed, resisted, vilified, and excoriated. The central problem with morality is this all or nothing approach to the way we treat people. Shared cultural values place a stranger within your circle of empathy, and there are no holds barred regarding the treatment of those outside of it.

The fact is that 99% of crime and mayhem is perpetuated in the name of morality, not sadism. Consider: terrorists consider themselves soldiers; most gang violence is perpetuated in the defense of honor and retribution; many murders are crimes of passion, and most murderers maintain their innocence for the duration of their incarceration (“he made me do it”). So for starters, the facts are not with morality. The illusion of morality contains at its heart the very key to transcending it: What are those core principles, if not lighthouses designed to steer us away from our own impulses? Does the very existence of “thou shalt not kill” imply the existence of the killing instinct within us? Don’t we all have the capacity to kill under the right circumstances, say, if defending our family from a home invader or if dropped into enemy territory in wartime? Enter reason: All human beings, regardless of their cultural values, share a common set of motives and emotions, encoded in human DNA. We are angered by an insult, saddened by death and injury, envious of those who have more, and long for the respect and adoration of others, to name a few. These are the “X’s and Y’s” that make human beings interchangeable when analyzing hard moral questions: How would I react if my spouse was shot? My house burned? My city flooded? My country bombed? If I were born in a dictatorship?

(Next: On Angels' Wings)

by Steven Pinker, Chapter 9

(Previously: Inner Demons)

(Credit: All block quotes are excerpts from the book.)

Chapter 9: Better Angels

“[It] cannot be disputed that there is some benevolence, however small, infused into our bosom; some spark of friendship for human kind; some particle of the dove, kneaded into our frame, along with the elements of the wolf and serpent. Let these generous sentiments be supposed ever so weak; let them be insufficient to move even a hand or finger of our body; they must still direct the determinations of our mind, and where every thing else is equal, produce a cool preference of what is useful and serviceable to mankind, above what is pernicious and dangerous.” ~David Hume, An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals

All throughout this book, empathy is touted as the greatest contributor to peace in a society. Adam Smith doubted it. He proposed a charming “Little Finger Paradox” that goes such: If a natural disaster were to befall a foreign people you would probably feel sorry for them but lose no sleep over it, being so far removed from your own daily life. Yet if some personal “disaster” were to befall you, such as losing your little finger in an accident, such a thing would dominate your thinking, your speech, your actions, and sustain a sense of anguish in you for quite some time. Suppose then that you were offered a bargain of sacrificing your little finger in order to save millions from some far-off disaster. Most people would accept such a sacrifice, not necessarily out of a sense of grandiosity, but of reason: one individual’s little finger is worth far less than millions of strangers’ lives. Why the disconnect? His “paradox” asks why our emotions (indifference vs agitation) are so varied from a reasoned comparison. Of course, it’s no paradox at all, it merely highlights the fact that emotion (including sympathy) is a biological function of a self-interested animal, and that reason is something that transcends evolution.

While there are several better angels in the human constitution, Pinker declares reason the king of them all. Reason is what allows us to analyze moral puzzles like the above from a disinterested bird’s eye view before making decisions that affect us personally. In the world of abstract reason, “my little finger” and “a disaster claiming millions of lives” can be represented as “a small loss for X” vs “a great loss for millions of Y” and this abstraction, from “me vs you” and “us vs them” to a generic “X vs Y” is the engine at the heart of empathy. The ability to step outside yourself and see the world through the eyes of those around you (and others far away!) leads to an attitude of “there but for fortune go I.” It is reason, therefore, that underlies the philosophies of secular humanism and classical liberalism. (“Classical” used here to distinguish enlightenment thinking from the modern political use of the word “liberal.”)

What about morality? Most of us have an instinctive understanding of crime and mayhem as being committed by a small group of people driven by motives of pure evil and hatred. In effect, we project our shadow (to borrow a term from Jung) on those we dislike, misunderstand, or are suspicious of, and consider “them” living in a separate world completely cordoned off from our own, living by principles completely antithetical to our own. This is “morality.” The idea that some core set of principles guides the better angels of our natures and those that stray from those principles or were never taught them are unhuman and descend into a life of darkness. Immoral individuals can only be “saved” from darkness by instilling in them the right principles, and if they cannot be saved, they ought to be oppressed, resisted, vilified, and excoriated. The central problem with morality is this all or nothing approach to the way we treat people. Shared cultural values place a stranger within your circle of empathy, and there are no holds barred regarding the treatment of those outside of it.

The fact is that 99% of crime and mayhem is perpetuated in the name of morality, not sadism. Consider: terrorists consider themselves soldiers; most gang violence is perpetuated in the defense of honor and retribution; many murders are crimes of passion, and most murderers maintain their innocence for the duration of their incarceration (“he made me do it”). So for starters, the facts are not with morality. The illusion of morality contains at its heart the very key to transcending it: What are those core principles, if not lighthouses designed to steer us away from our own impulses? Does the very existence of “thou shalt not kill” imply the existence of the killing instinct within us? Don’t we all have the capacity to kill under the right circumstances, say, if defending our family from a home invader or if dropped into enemy territory in wartime? Enter reason: All human beings, regardless of their cultural values, share a common set of motives and emotions, encoded in human DNA. We are angered by an insult, saddened by death and injury, envious of those who have more, and long for the respect and adoration of others, to name a few. These are the “X’s and Y’s” that make human beings interchangeable when analyzing hard moral questions: How would I react if my spouse was shot? My house burned? My city flooded? My country bombed? If I were born in a dictatorship?

The world has far too much morality. If you added up all the homicides committed in pursuit of self-help justice, the casualties of religious and revolutionary wars, the people executed for victimless crimes and misdemeanors, and the targets of ideological genocides, they would surely outnumber the fatalities from amoral predation and conquest. The human moral sense can excuse any atrocity in the minds of those who commit it, and it furnishes them with motives for acts of violence that bring them no tangible benefit.

(Next: On Angels' Wings)

Published on July 26, 2016 15:23

•

Tags:

steven-pinker, the-better-angels-of-our-nature, the-new-peace, violence, war

Mediascover

I like to blog about books, technology, self-publishing, the writing process, copyright issues, and my reading experiences.

- Victor A. Davis's profile

- 67 followers