Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 908

December 30, 2015

“Any body—every body—is a bikini body”: Women’s Health bans the phrases “Bikini Body” and “Drop Two Sizes” from its covers for good

You told us you don’t love the words shrink and diet, and we’re happy to say we kicked those to the cover curb ourselves over the past year. But we’re still using two other phrases—“Bikini Body” and “Drop Two Sizes”—that you want retired. Since our goal is always to pump you up, and never to make you feel bad, here’s our pledge: They’re gone. They’ll no longer appear on Women’s Health covers.The announcement comes after a year where body-positive activism, especially around the concept of what’s “acceptable” to wear according to your size, was prominent. In June, size 22 model Tess Holliday released a 16-second video for plus size clothing company SimplyBe, whose clothes range from sizes 10 to 32, in which she demonstrated in one simple step that all that’s needed for a “bikini body” is to wear one. Holliday was quoted on SimplyBe’s site saying, “All women need to do to get a bikini body is to put a bikini on, then they’re ready to hit the beach! There is no such thing as a perfect body and the hardest barrier for women to overcome is themselves. And no wonder, considering the skinny body ideals that are portrayed widely across the media today.” The blog Fat Girl Flow posted a photo essay of fat women in bikinis and dedicated it to “every fat babe who has felt under represented in the community because of the color of their skin, the size or shape of their body, their ability, or their gender. For the beauties with huge bellies and tiny legs, and the babes who can’t find their size even in the plus size section, it’s for the hairy babes, for the double chins and double bellies.” In July, Wear Your Voice magazine launched its #DropTheTowel campaign to encourage readers to “proudly proclaim that they are done hiding their already beautiful beach/pool/lake or otherwise summer body – and are ready to lose that cover-up and drop the towel!” Also in July, “Orange Is the New Black” actress Danielle Brooks donned a bikini as part of People Style Watch’s #LoveYourShape campaign. In August, the blog Fatshion Peepshow posted photos and inspiring quotes from 101 “body positive bikini babes.” And when Patrick Couderc, the managing director of Herve Leger in London, gave an interview stating that “voluptuous” women and those with “very prominent hips and a very flat chest” shouldn’t wear the company’s popular bandage dresses, he was met with a call for a boycott by comedian and actress Margaret Cho and a disavowal from parent company BCBGMAXAZRIA, which terminated his employment. In other words, it seems that Women’s Health has come to realize what many already know: Consumers, even health-conscious ones, even ones who may want to lose weight or have other specific fitness goals, don’t like being told that there’s something inherently wrong with their too-big bodies when they pick up a magazine. They want to be inspired to live healthfully at whatever size they are now, without the default assumption that certain sizes are inherently better than others. Laird states that outright, quoting a reader who told the magazine, “I hate how women’s magazines emphasize being skinny or wearing bikinis as the reason to be healthy.” While Laird’s stated promise is to remove the phrases from Women’s Health covers, not necessarily from inside the magazine’s pages, she did go so far as to write “Dear John” letters to each phrase, emphasizing her point. Of “bikini body,” she wrote, “You’re actually a misnomer, not to mention an unintentional insult: You imply that a body must be a certain size in order to wear a two-piece. Any body—every body—is a bikini body. You’ve got a shaming, negative undertone that’s become more than annoying.” This is a wonderful start toward creating a media landscape where women aren’t bombarded so blatantly with the message that they should constantly be trying to make themselves literally smaller in order to be “healthy.” By nixing “drop two sizes,” the magazine is openly acknowledging that not only can losing too much weight too fast be unhealthy, but also that there’s no standard one size fits all way of measuring health based on size, because everyone’s body works differently. Many observers have expressed cautious optimism about the Women’s Health announcement. After all, it’s one thing to take those provocative words off their covers, but that doesn’t mean they’ve conceded that women shouldn’t strive for what’s traditionally considered a “bikini-ready” body. They have, after all, advocated eating just 1,350 calories a day in an article titled “Safe Weight Loss: Get Bikini Ready in 7 Days.” At Refinery29, Health and Wellness Director Anna Maltby, who’s worked at both Men’s Health and an unnamed women’s health magazine, highlighted some of the things she hopes will go along with Women’s Health’s attention-getting change. “[W]hile I’m proud of the team at WH for making a splashy, body-positive statement like this — I’m not so quick to interpret this as an earth-shattering, needle-moving change in the vast and sinister world of body-shaming messages that women have to deal with daily. Are they still going to run diets inside? Are they still going to help you ‘target’ your ‘problem areas’? Let’s hope that as the negative messages on the cover begin to dwindle, so do the ones hiding behind it.” On social media, users applauded the decision with similar sentiments: https://twitter.com/wendymfelton/stat... https://twitter.com/langernutrition/s... On Instagram, the company Super Sister Fitness wrote that they also hate the term “bikini body”—even though they run a Bikini Bootcamp Challenge—and praised the magazine’s decision. They went on to say, “Our best-selling ‘Bikini Bootcamp’ program was never intended to be built around the phrase ‘Bikini Body’ and we still hate even having the word bikini in there at all.” They are considering changing the title, but cited a high SEO ranking for “bikini body” as the main impediment to doing so. Melissa Toler, a life and wellness couch who encourages people to break free from “food rules,” told Salon, “For the past few years, I've stopped buying health and fitness magazines like Shape and Women's Health because of the constant ‘lose weight,’ ‘drop two sizes,’ and ‘blast fat’ cover articles. It was the same old story every month repackaged with a new fit celebrity gracing the cover. Plus I was tired of getting a monthly reminder that there was something wrong with me and this magazine would help me fix it.” Toler is optimistic about this new look for Women’s Health, but is reserving judgment about its long-term impact. She continued, “So when I saw the decision by Women's Health, I was happy but a little skeptical. There's a trend in the diet and fitness industry where companies like Weight Watchers and Lean Cuisine are moving away from traditional weight loss marketing to putting a focus on the whole person, not just the numbers. But they continue to perpetuate diet culture in an effort to sell products. The Women's Health decision is a step in the right direction, but only time will tell if this is the real deal."Yesterday, Women’s Health editor in chief Amy Keller Laird made a bold announcement on the magazine’s website: They would no longer be using the phrases “bikini body” or “drop two sizes” on their covers. Taking cues from a reader survey, Laird wrote:

You told us you don’t love the words shrink and diet, and we’re happy to say we kicked those to the cover curb ourselves over the past year. But we’re still using two other phrases—“Bikini Body” and “Drop Two Sizes”—that you want retired. Since our goal is always to pump you up, and never to make you feel bad, here’s our pledge: They’re gone. They’ll no longer appear on Women’s Health covers.The announcement comes after a year where body-positive activism, especially around the concept of what’s “acceptable” to wear according to your size, was prominent. In June, size 22 model Tess Holliday released a 16-second video for plus size clothing company SimplyBe, whose clothes range from sizes 10 to 32, in which she demonstrated in one simple step that all that’s needed for a “bikini body” is to wear one. Holliday was quoted on SimplyBe’s site saying, “All women need to do to get a bikini body is to put a bikini on, then they’re ready to hit the beach! There is no such thing as a perfect body and the hardest barrier for women to overcome is themselves. And no wonder, considering the skinny body ideals that are portrayed widely across the media today.” The blog Fat Girl Flow posted a photo essay of fat women in bikinis and dedicated it to “every fat babe who has felt under represented in the community because of the color of their skin, the size or shape of their body, their ability, or their gender. For the beauties with huge bellies and tiny legs, and the babes who can’t find their size even in the plus size section, it’s for the hairy babes, for the double chins and double bellies.” In July, Wear Your Voice magazine launched its #DropTheTowel campaign to encourage readers to “proudly proclaim that they are done hiding their already beautiful beach/pool/lake or otherwise summer body – and are ready to lose that cover-up and drop the towel!” Also in July, “Orange Is the New Black” actress Danielle Brooks donned a bikini as part of People Style Watch’s #LoveYourShape campaign. In August, the blog Fatshion Peepshow posted photos and inspiring quotes from 101 “body positive bikini babes.” And when Patrick Couderc, the managing director of Herve Leger in London, gave an interview stating that “voluptuous” women and those with “very prominent hips and a very flat chest” shouldn’t wear the company’s popular bandage dresses, he was met with a call for a boycott by comedian and actress Margaret Cho and a disavowal from parent company BCBGMAXAZRIA, which terminated his employment. In other words, it seems that Women’s Health has come to realize what many already know: Consumers, even health-conscious ones, even ones who may want to lose weight or have other specific fitness goals, don’t like being told that there’s something inherently wrong with their too-big bodies when they pick up a magazine. They want to be inspired to live healthfully at whatever size they are now, without the default assumption that certain sizes are inherently better than others. Laird states that outright, quoting a reader who told the magazine, “I hate how women’s magazines emphasize being skinny or wearing bikinis as the reason to be healthy.” While Laird’s stated promise is to remove the phrases from Women’s Health covers, not necessarily from inside the magazine’s pages, she did go so far as to write “Dear John” letters to each phrase, emphasizing her point. Of “bikini body,” she wrote, “You’re actually a misnomer, not to mention an unintentional insult: You imply that a body must be a certain size in order to wear a two-piece. Any body—every body—is a bikini body. You’ve got a shaming, negative undertone that’s become more than annoying.” This is a wonderful start toward creating a media landscape where women aren’t bombarded so blatantly with the message that they should constantly be trying to make themselves literally smaller in order to be “healthy.” By nixing “drop two sizes,” the magazine is openly acknowledging that not only can losing too much weight too fast be unhealthy, but also that there’s no standard one size fits all way of measuring health based on size, because everyone’s body works differently. Many observers have expressed cautious optimism about the Women’s Health announcement. After all, it’s one thing to take those provocative words off their covers, but that doesn’t mean they’ve conceded that women shouldn’t strive for what’s traditionally considered a “bikini-ready” body. They have, after all, advocated eating just 1,350 calories a day in an article titled “Safe Weight Loss: Get Bikini Ready in 7 Days.” At Refinery29, Health and Wellness Director Anna Maltby, who’s worked at both Men’s Health and an unnamed women’s health magazine, highlighted some of the things she hopes will go along with Women’s Health’s attention-getting change. “[W]hile I’m proud of the team at WH for making a splashy, body-positive statement like this — I’m not so quick to interpret this as an earth-shattering, needle-moving change in the vast and sinister world of body-shaming messages that women have to deal with daily. Are they still going to run diets inside? Are they still going to help you ‘target’ your ‘problem areas’? Let’s hope that as the negative messages on the cover begin to dwindle, so do the ones hiding behind it.” On social media, users applauded the decision with similar sentiments: https://twitter.com/wendymfelton/stat... https://twitter.com/langernutrition/s... On Instagram, the company Super Sister Fitness wrote that they also hate the term “bikini body”—even though they run a Bikini Bootcamp Challenge—and praised the magazine’s decision. They went on to say, “Our best-selling ‘Bikini Bootcamp’ program was never intended to be built around the phrase ‘Bikini Body’ and we still hate even having the word bikini in there at all.” They are considering changing the title, but cited a high SEO ranking for “bikini body” as the main impediment to doing so. Melissa Toler, a life and wellness couch who encourages people to break free from “food rules,” told Salon, “For the past few years, I've stopped buying health and fitness magazines like Shape and Women's Health because of the constant ‘lose weight,’ ‘drop two sizes,’ and ‘blast fat’ cover articles. It was the same old story every month repackaged with a new fit celebrity gracing the cover. Plus I was tired of getting a monthly reminder that there was something wrong with me and this magazine would help me fix it.” Toler is optimistic about this new look for Women’s Health, but is reserving judgment about its long-term impact. She continued, “So when I saw the decision by Women's Health, I was happy but a little skeptical. There's a trend in the diet and fitness industry where companies like Weight Watchers and Lean Cuisine are moving away from traditional weight loss marketing to putting a focus on the whole person, not just the numbers. But they continue to perpetuate diet culture in an effort to sell products. The Women's Health decision is a step in the right direction, but only time will tell if this is the real deal."

Hillary Clinton is more right wing than you think: For progressives, a vote for her over Bernie Sanders is a waste

As 55 people died in Iraq on Saturday, the holiest day on the Shiite Muslim religious calendar, Sen. Hillary Clinton said that much of Iraq was "functioning quite well" and that the rash of suicide attacks was a sign that the insurgency was failing. "The fact that you have these suicide bombers now, wreaking such hatred and violence while people pray, is to me, an indication of their failure," Clinton said.Is there any justification for Clinton saying the Iraqi insurgency was failing, even after a full blown civil war had already commenced in Iraq? As for wealth inequality, a POLITICO article titled "Why Wall Street Loves Hillary" explains exactly why progressives are voting against their interests, in terms of wealth inequality, with a Clinton presidency:

While the finance industry does genuinely hate [Elizabeth] Warren, the big bankers love Clinton, and by and large they badly want her to be president.Is there a Clinton supporter on the planet who can explain why Wall Street bankers "badly want" her as president? As for her similarities to Republicans, it's alarming that Nixon biographer Evan Thomas (like Orlando Patterson) correlated Clinton's character to Nixon in a Wall Street Journal piece titled "Hillary Millhouse Nixon":

Lately, Mrs. Clinton has shown some Nixonian tendencies to try to stonewall and cover up. Her handling of the Clinton Foundation and email controversies is right out of the Nixon play book: Treat every new revelation as old news, attack the messenger as biased, reveal only what you have to — the old "modified, limited hangout," in the parlance of Nixon aide John EhrlichmanIt's telling that a Nixon biographer sees various similarities to Hillary Clinton. Like Thomas, I explained Clinton's correlation to Nixon in a Hill piece titled "If Nixon had email, he'd have been just like Hillary Clinton." In contrast, Bernie Sanders and his campaign are bolstered by genuine progressive ideals, not political expediency. A Boston Globearticle titled Bernie Sanders' surge is partly fueled by veterans explains the energy and enthusiasm of the Sanders campaign:

"He is revered," said Paul Loebe, a 31-year-old who served in both Iraq and Afghanistan during eight years of active duty... "He's very consistent with where he stands. He's the first politician that I've believed in my life."Like Mr. Loeb, Bernie Sanders is indeed the only politician I've ever trusted in my life besides Elizabeth Warren. Conversely, 61% of American voters distrust Clinton according to polls. Clinton as president can't influence the NRA, but she can utilize the AUMF to wage endless wars. Only Bernie Sanders upholds the progressive values many establishment Democrats like Clinton jettisoned for political power. For this reason, it's only logical to choose Sanders over Clinton, if ideals like ending perpetual war, wealth inequality, and racism mean anything to Democrats in 2016. (This article first appeared on The Huffington Post)

“We are refugees”: Rights groups rally against Obama admin’s planned mass deportation of Central American migrants

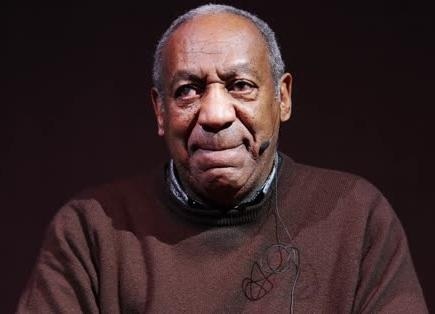

Bill Cosby still wins

It’s not too late: Why finally charging Bill Cosby in 2004 case is a victory for all victims of sexual abuse

To reiterate: This was in People magazine, published nationwide in December 2006. Four women said publicly, in major media outlets, that Bill Cosby had drugged and sexually assaulted them. This coverage was more recent and possibly more prominent that the coverage of the abuse allegations against Woody Allen."Basically nobody wanted to live in a world where Bill Cosby was a sexual predator," Scocca concluded. "It was too much to handle." Apparently not. Or maybe it was too much for people to handle in February of 2014, but by October of that same year, people were ready to listen. That's when comedian Hannibal Buress, likely inspired both by Scocca's piece and by interviews with two other accusers published in Newsweek, accused Cosby of being a rapist in his stand-up act. This blew the doors off the whole thing, causing a cascade of media attention, with dozens of women stepping forward and 35 of the agreeing to be interviewed, by name, for New York in July 2015. These charges are barely skating in under the statute of limitations, which has long passed for most of the accusations. It might seem excessive at this point to try to get this one at the last minute, especially considering Cosby's advanced age and the serious hit his reputation has taken. But in reality, this move is a crucial one. Cosby has been able to keep a lid on this for so long by being incredibly litigious. Just this month, Cosby sued a number of his accusers for defamation, demanding retractions of their public statements. Whether or not he can win that lawsuit is beside the point. The move seems to be more about using Cosby's immense wealth to intimidate his accusers into silence. But throwing money around in an attempt to silence people is a harder thing to pull off when you're being slapped in cuffs and made to do the perp walk. The sad fact of the matter is that Cosby isn't nuts in thinking that he could be successful by suing for defamation. While most in the media seem to grasp that it's nearly impossible for 50 women to all by nutty bitches who are making stuff up because women are crazy, the stereotype that women are inherently untrustworthy and prone to fabrication still has a strong hold over much of the public. A huge number of people still give one man's word more credibility than that of a busload of women's word, as evidenced by the standing ovations that Bill Cosby has been enjoying in his latest stand-up tour. Under the circumstances, it's not unreasonable to fear that he could have strong-armed a retraction out of his accusers, which in turn would help reinstate the myth that many to most women who accuse rape are just crazy women making stuff up. (Obviously, a small percentage of women who claim rape are lying, but the numbers are much smaller that much of the public believes.) Knee-capping his efforts by having an actual prosecutor, especially one close to home, filing charges is a huge victory against those efforts.

December 29, 2015

Best TV of 2015: The relationships, big and little, that made TV worth watching

The inmate I can’t forget: I thought prison inmates were the dregs of society, until I became one of them

“Bread and water.” This was dad’s response to my question about what prisoners ate. My childhood inquisitiveness was probably piqued from viewing a cartoon with men in black and white stripes toiling away on a chain gang. For years I thought that was the ultimate punishment for those serving time behind bars: dry, crumbling grains with lukewarm water. And I thought they deserved it. I thought that inmates were the dregs of society, the worst people that must be avoided at all costs. They were the men who tried to lure children away with large spiraling lollipops. They wore large overcoats, never shaved, and had yellow teeth with several metal caps. They were easily discernible, and were you to encounter one of these monsters, you would immediately know.

Over time my perception of prisoners changed, but not considerably. They were still the dregs of society. The mental image of an overcoat was replaced by skin coated with tattoos. Mainstream media didn’t help. Shows like “ America’s Most Wanted,” and “ Cops” helped solidify my impressions. A judgment-fueled conception about criminals helped me feel safe and better about myself. Little thought was dedicated to that far removed aspect of society. In my mind, prisoners still deserved “ bread and water.”

Years later I got to taste the incarcerated diet, and ironically it was extremely well balanced, probably more so than anything I had consumed since leaving my childhood home. Our two daily meals consisted of a carton of milk, animal protein, vegetables, and fruit. And there was bread- three pieces to mop up any lingering scraps that still clung to the tray (while the meals were balanced, they were always short on food).

The garb didn’t consist of the two-toned jumpsuits as I’d once seen. Instead, two pieces sets, “tops and bottoms,” came twice weekly with clothing exchange. The shirts and pants consisted of thick orange cloth. Many of the articles were very worn out from years of use. A good pair of pants could fetch several commissary items among the inmates who still prided themselves in appearance. I once wore a pair of pants for 6 months because they fit nicely.

But mostly what seemed different were my new peers. At first they fit the stereotypes that I had entertained for most of my life. I wasn’t one of them, at least in my own eyes. They did have the tattoos. Some were gang members. Many seemed scary. I kept to myself initially, immersing myself in a literary world on my bunk for the majority of each day. I only interacted if I had to, and even then I kept it brief. But eventually a combination of comfortability and boredom prevailed. My cell became my home, the dayroom my social outlet. Jail became my life, even if it was a temporary one. But most importantly, I made friends. These friendships challenged my concept of what a criminal was, and how the criminal justice system worked. Ultimately, they helped me understand that the larger narratives and policies associated with drug use and crime are not beneficial to helping those with addiction. It was through my friendships and experiences in jail that I learned that the criminology of drug use is flawed, and that the current approach to dealing with drugs via the penal system is antiquated, inhumane, and failing.

The initial person I bonded with was a man I shared a cell with for four months. He was my first real cellmate. Mike had tattoos from head to toe, or more literally, from neck to ankle. The homemade prison ink had faded and run together. Consequently, Mike had almost no exposed white skin. From afar his complexion resembled a graying bird turd. Mike had a lengthy blonde goatee and thinning hair on his scalp. His arms and legs were wrapped in thick layers of old muscle, muscle that was obtained from countless confined workouts. Mike was forty-two and had spent eighteen years of his existence behind a fence, iron-gate, or plexiglass door.

I’ll never forget our first handshake. The loudspeaker barked my cell assignment, “O’Connor, cell #6,” and I sauntered up the stairs to the upper tier. The door clicked open moments before reaching it. Mike stood alert and very present awaiting my entrance. We met eyes and executed an exceptionally formal and silent handshake. It simultaneously conveyed respect and obligation, with a twinge of defensiveness. Years later, I had a similar handshake with a Japanese girlfriend’s father. Both times I was terrified.

Over the ensuing months, I got to know Mike incredibly well, perhaps better than anyone I had known in the previous few years. Twenty-two hours per day in a six by fourteen foot space will do that. We laughed at each other’s farts, traded Star Trek books, cooked meals (mostly just top ramen and refried beans), and critiqued the weekly soaps on television.

During a visit with my lawyer, he asked me what the people I was spending my days with were like. He urged me to learn the details of their past. In retrospect, I believe it was an exercise to help me understand how fortunate I was. So at the behest of my lawyer, I questioned Mike about his family.

Mike’s upbringing was infinitely worse than mine. When Mike was still in his mother’s womb, she had caught his father cheating. Extremely upset, Mike’s mother took her two other children, Mike’s brother and sister, and sped away from the house in the family car. Down the street the car flipped, instantly killing Mike’s brother and sister, and placing his mother in the hospital for the rest of her life. She lost most of her brain function, and only lived through life support. Yet Mike was delivered without any complications. He was raised alone by his father, although his father never recovered emotionally from the accident. Mike said he was a “shadow of a man.” They visited his mother in the hospital for years, even though she was incapable of registering their presence. It goes without saying that Mike faced challenges that are foreign to most of us. I got the feeling he didn’t hit most of the milestones of childhood.

While our familial histories were vastly different, we shared the common bond of addiction. Many of our talks centered upon romancing the drug or reliving an intoxicated adventure. Occasionally, he would caution as to where my life was headed with such behavior, but I didn't heed his warnings. I’d generally dismiss such speak with a “Yeah, yeah” or “ I know, I know.” Then I would ask him to tell another story. I was fascinated by his life. I loved listening to him talk, and the more I learned about his story, the more my respect and fondness for him grew.

Mike had a deluge of court paperwork that he traveled with throughout his incarceration. It was one of the few ways that he could add some resistance to his workouts that the guards couldn't curtail. In other words, Mike would do bicep curls and tricep extensions with loads of legal papers because the prison could not dispose of them. His crimes literally made him stronger.

One day Mike shared some of his paperwork with me. One line in particular hit me hard. It was in brackets and it read: (Defendant laughs). It was Mike’s recorded reaction to the judge’s sentencing of fourteen years in prison. The legal system decreed many, many years in prison and Mike took it in stride. He laughed! I still remember looking at him after reading that line and thinking, “This guy is the man. He has got it all figured out. He is untouchable. Nobody can hurt him.” I desperately wanted to be like Mike. I wanted to laugh in the face of despair. I wanted to not care.

The problem was that he did care now. He wanted a better life, but it was too late. He had become a reliable person, the type of man that I would trust to watch my children, that I would lend the keys of my car to, that I would have check up on my family if I were away. Yet the wreckage of his past made it impossible for him to move on.

When I met Mike he was serving a 38-month prison sentence for $20 worth of heroin. His previous crimes had made it so any new crime garnered tremendously long sentences. When he was 18 years old he had robbed several video stores to support his drug addiction. He used a gun and a bandana, and was known in the papers as the “ video store bandit.” No one ever got hurt, but the three-month spree was enough to earn him that 14-year sentence. Upon release from prison he immediately went back to prison for a few years. He had been eating at a food court in a Target and seen a bag of cash sitting on the internal bank’s counter. Someone had left it on the counter after transporting it from a full register. Mike grabbed it and ran. His getaway vehicle was a bicycle; clearly the crime wasn’t well thought out. He didn’t make it far. His third crime was the possession of heroin. The other two crimes had earned him “strikes” because they were committed in California, one of the few states that still has the three-strike law.

The three strikes law in California was intended to curb habitual criminal offenders by offering increasingly sharp penalties for felons. It was originally passed as Proposition 184 in 1994, and it immediately began placing large numbers of people in prison for extraordinary lengths of time. In that sense, it worked. It did what it was supposed to do, put habitual offenders in prison. However, it failed in every other aspect. It didn’t reduce crime. It cost the state (and tax payers) exuberant amounts of money. It overcrowded the prison system. And it didn’t even deter people from striking out.

As for Mike, and the 38 month sentence he was serving for possession, it should be noted that this was a very merciful amount of time when compared with the criminals in similar situations who had gone before him. In Mike’s case, the judge “striked the strike in the interest of justice.” What this means was that the judge sentenced him without striking him out. This had become a more regular thing by this period (Mike was sentenced in 2004) because the prisons were becoming so overcrowded with people serving life sentences for possession.

The policy wasn’t formulated to warehouse non-violent criminals in prison for drug offenses, and sadly that was what it became, and still continues to be. I learned about the criminology of drug use by living, eating, and breathing with the victims of this failing legislation: those serving long-term prison sentences for drug related crimes.

When someone is in the throes of addiction, forethought and reason don’t motivate their actions. I found myself in horrible places as a result of my drug abuse. I was faced with legal predicaments that had the capability of removing me from society for an extremely long period of time. Luckily, I came from a family with resources and was able to have my case heard for all the nuances within it. Had Mike been able to receive the same legal aid that I did, I have no doubt that he would have gotten a much better deal, and ultimately a better life. Intelligent and empathic, he was a man who would have benefitted tremendously from therapy and substance abuse treatment for his drug addiction. Ironically, his only “substance abuse treatment” was incarceration.

The details of my own case are hazy; I have almost no recollection of my crime. I vaguely remember driving around with one of my roommates and asking him to pull over at a veterinarian’s office. The next thing I remember was waking up in a cell. The robbery I committed was done in a complete blackout. It was not even a subject of debate whether I was in the right state of mind during my crime. I made bail, which was considerable, and spent the next two years of my life as a resident of various inpatient treatment centers while I fought my case.

Eventually I signed a deal for 6 months of jail and an additional one-year of inpatient treatment, with a ten year suspended prison sentence if I violated the terms of my probation. The jail was easy, but the treatment wasn’t. I ran away, driven by a compulsion to get high. I didn’t care. No thought was wasted on the ten-year sentence that awaited me; I had the same mindset as Mike when he grabbed the bag of cash shortly after being released from prison. Eventually I was picked up on a warrant and the judge wasn’t as amenable as the district attorney had been when I signed my original deal.

But my family came to the rescue. They threw more resources at the problem, hired experts, and got the judge to review my case one more time. He showed leniency and gave me a one-year sentence with a mandate to complete a special type of treatment afterwards. I completed the program, although it took me years before I really made the transition to caring about my life. Yet when I finally made this transition, I wasn’t in prison serving a lengthy sentence for a relatively minor offense. I didn’t share Mike’s legal predicament simply because I had money.

When I went to jail, I thought that prisoners were sociopaths— cold calculating people incapable of empathy. I learned that is very far off from reality. Most prisoners end up behind bars as the result of a poor environment, mental illness, or substance abuse. For Mike and I, we were both sick people struggling with addiction who made impulsive choices that cost us heavily, however Mike paid much more dearly than I did.

It has been over ten years since I met Mike, yet I still think about him. He was the first person I knew from a multitude of prisoners who were good people but lost their lives to an overly punitive legal system. It saddens me to think of the scores of men and women across the nation who have little chance at redemption simply because we elect to contain the problem rather than solve it. This depressing fact has motivated me in part to take action in my own life. I returned to school to finish my bachelor’s degree, and am in the process of applying to doctoral programs in psychology with a concentration in forensics. Strangely, I’m attempting to return to the place that I once desperately wished to escape.

“I’m not drinking right now”: Sometimes even non-alcoholics need to stop

***

Here’s what I’ve learned since I haven’t been drinking. Please note that I don’t say, “Since I got sober,” or even “Since I stopped drinking.” I say, “I’m not drinking right now.” More on this in a minute. Being with a bunch of people who are drinking was a lot more fun when I was drinking. I hang out in the same living rooms now that I hung out in then, back when I was drinking and laughing in a pleasant state of soft-focus. But now I’m sipping Perrier, laughing lamely, wondering what’s so funny. And wondering whether, when I was drinking, I slurred my words and got so vehement about nothing and was as difficult to connect with — as unreachable! — as my drinking friends are. As my abstinent months march on, I’m also noticing there’s usually a person or two or five in those living rooms who are abstaining from buzz beverages, too. Were the water drinkers there all along and I’m just noticing them now, the way you start seeing orange cars when you buy one? Have I simply shifted my attention away from the wild bunch and toward the “program people” in the room? Is sobriety a new L.A. fad — is sober the new drunk? Despite my tiny tendency to be dramatic, I’ve restrained myself from announcing my temporarily sober status. No Facebook posts, no tweets. When people offer me drinks, I simply say, “I’m not drinking right now.” Surprisingly, nearly everyone responds the same way. “That’s so great!” “What’s so great about it?” I ask, hoping to be convinced that my unpleasant experiment has some kind of unseen greatness to it. “I wish I could stop drinking.” “Why?” I ask. Pensive face, resigned shrug, sip of Malbec. “It would be good for me.” “I’d lose weight.” “I’d stop driving drunk.” “Why don’t you, then?” “I will, someday.” “I’ve tried. I couldn’t stick to it.” “I’d never make it through a day without my wine.” Another surprise, less than delightful: Not drinking is making me gain weight. When I first stopped, my friends squealed, “You’re gonna get so skinny!” (Did I mention I live in a city whose initials stand for Lifetime Anorexia?) I might be happily making my friends’ worst fears come true, if only I hadn’t traded my old lovers (Helena, alcohol) for my new ones (Ben, Jerry). Not my fault, the NIMH says. Deprived of alcohol’s feel-good dopamine surge, the body craves another source. “Sugar … releases opioids and dopamine and thus might be expected to have addictive potential.” Oh, joy: I’m not even an addict (more on this soon, as promised) but now I have to kick two drugs. My two favorite drugs. Just swell. For better and worse, online dating is out now, too. I don’t like the kind of people who meet for coffee. I like the kind of people who meet for drinks. Why, then, you might ask, are you putting yourself through this? I ask that of myself multiple times each day. I don’t know. No, really. I don’t. And I’m good with that. Maybe I’ve been in La-La too long, but I believe in not knowing. Some of the best things in my life have happened following oh-so-rare episodes of waiting-and-seeing, instead of my usual rushing-to-resolve-it-already. I stopped, initially, to give Helena and me our best shot. I continue to test the notion that my life — that I — might be better off, today or forever, without alcohol. I can always have a drink. I can’t always not-have-had a drink. Despite my resistance to sobriety as more than a brief experiment, I cannot deny the improvements as well as the discomforts not-drinking has brought me. I sleep better when I don’t attempt to douse my lifelong insomnia with a very tall nightcap. I’ve been more productive, since now I can work after dinner, so I’m making more money. I’m saving money, too: Even at five bucks a pint, Ben & Jerry’s is cheaper than Hendrick’s. I’ve grown closer to some of the other non-drinkers in the room and in “the rooms.” Sober people, I’ve discovered, tend to make really, really good friends — whatever makes them sober also makes them honest, direct and self-aware. I’m a better friend to myself, now, too. I keep hold of the things I think and feel after cocktail hour, the ideas I have, instead of losing them in a haze of table-dancing. At my age, improved memory is a benefit beyond AARP’s wildest promises. So, yes: It’s great, what I’m doing, even though I don’t know why I’m doing it, or for how long, or what, exactly, is so great about doing it. I do know this: I’m proud of myself. Waking up in the morning, knowing that I resisted Hendricks' siren call last night, is the opposite of how I feel, wincing at the empty Peanut Butter Core pint in last night’s trash. So shoot me: I still don’t think I’m an alcoholic. The NIH might not agree. “The term 'addiction,'” it says, “implies psychological dependence and thus is a mental or cognitive problem, not just a physical ailment.” Based on the fact that I stopped drinking and can’t, according to my own criteria, start again, I’ve diagnosed myself, instead, as what the CDC calls an “excessive” or “problem drinker” — now, a “problem not-drinker.” A November 2014 CDC study of excessive alcohol consumption in the United States concluded, “It is often assumed that most excessive drinkers are alcohol dependent. However … Most excessive drinkers (90%) did not meet the criteria for alcohol dependence.” That’s the CDC’s good news (for me). The bad news (for all of us): “Excessive alcohol consumption is responsible for 88,000 deaths annually.” I can vividly imagine those deaths. Because when I was drinking, even after the advent of Uber, I often drove buzzed — and by “often” I mean three or more nights a week. The fact that I never hurt myself or anyone else (to my impaired knowledge), or got stopped by the cops on one of the many occasions when my blood alcohol level would have sent me to jail, now seems nothing short of miraculous. So. Huh. Whether or not I’m an alcoholic, what I take from the science is that if I can’t drink “moderately” (the word that would be voted “least likely to succeed as Meredith’s lifestyle” by my friends, sober and not), I’m a problem drinker. And if I’m a problem drinker, I shouldn’t drink at all. That’s a problem for me. Because I still want to drink. I still plan to drink. Every day I think, “This is the day I get to have a martini.” Not just any martini, mind you, but a Hendrick’s martini, two ounces—no, four—shaken till nearly frozen, lovingly poured into an angular, tall-stemmed, arms-wide-open glass. I swoon, even now, at the thought of it. And then I think, “Get real. You don’t want one martini. You want a date with the bottle.” And so I sigh and go about my business, hoping that tomorrow will be the day I get to have a martini without having a problem.It started out as a night like many others. I was making dinner for Helena, the woman I’d been dating for a while. Candles flickered, curls of steam rose from prettily composed plates. It was my favorite moment of the day, neither too early nor too late to reasonably pour myself a drink. “Can I make you a cocktail?” I asked Helena, knowing that she’d say no. I’d suspected from the start that she and I weren’t it, that click-into-place fit, and this was one of the reasons. She didn’t dance on tables or quit jobs impulsively and she didn’t drink. A shared split of good Champagne to celebrate a book deal or a sweet summer night, sure. A few sips of one of my signature cocktails at one of my signature drinking-and-dinner parties, maybe. But she didn’t get wild and rowdy, laugh so hard she spit gin through her nose, text me first thing in the morning to ask what kind of damage she’d done the night before. You know what I mean. She didn’t drink. “I want to talk about your drinking,” Helena said. And right then and there, with our steaks au poivre cooling on our plates and a freshly shaken basil martini warming in my hand, I lost my amateur drinking status. Before we continue, a few words about me. Child of the '60s, uncomfortably past midlife, overly therapized, perennial seeker of all kinds of truth. Denial, delusion? Not my brand. I’m a memoirist and a journalist; for Christ’s sake, I wrote a book about addiction. So I paid attention when my alcohol consumption started escalating a few years ago, along with my affection for — or was it dependence on — the warm, loose, truthy-blurty blur that followed a cocktail or three. A series of recent losses (marriage, dear friend, beloved dad) had left me reeling, relocated and lonely in Los Angeles, where carbs are contraband, cocktails are compulsory, and everything stops for Happy Hour, every day of the week. Like a U-Haul lesbian couple, alcohol and I got serious fast. I cycled rapidly from wine with dinner to nightly complicatedly crafted cocktails, shaken and stirred by L.A.’s hippest mixologists, or homemade with ingredients I grew and brewed myself and consumed in my Silver Lake bungalow, with new friends or, more often, alone. “Seeker of truth,” remember? It concerned me, how much I loved to drink. So I started administering this little self-exam. I’d compare myself to the alcoholics I knew, ticking off the differences between us. I’d never had a blackout, or an overdose, or even a hangover. My drinking had never caused me to say anything I wish I hadn’t, or fall down, or puke. Unlike an alcoholic, I’d never lost anything to my drinking — time, a job, a relationship, my car keys. I’d never gotten a DUI. Most significantly — and this was my bright-line test, the notion to which I clung when I found myself counting down to happy hour at odd hours of the day —no one had ever expressed concern about my drinking. How could I have a drinking problem, when my drinking had never bothered me or anyone else? Until tonight. “You’re a different person when you drink,” Helena said. Everything in me rose up in rebellion against the sickening realization that I’d just flunked my own sobriety test. My bright line had been irrevocably crossed. Only one thing could restore me and my martini to our comfort zone. Helena had to take it back. “Of course I’m different when I drink,” I said. “That’s the whole point of drinking. Why would I consume all those liquid calories if I wanted to stay the same?” “You’re distant when you drink,” she said. “Unreachable. It makes me feel alone.” I extended my gently sweating martini glass, a three-olive branch. “Don’t feel alone,” I enticed her in my festive-sexy voice. “Drink with me.” Helena shook her pretty head. “I don’t want to be around you when you’re drinking. I don’t care what you do when you’re alone or with your friends, but from now on you can either drink, or you can spend time with me.” That’s what I get for dating a party-pooper, I thought — noting that I was taking full responsibility for my actions, something, I reminded myself, no addict would ever do. Looking longingly at my untouched, beckoning cocktail, I made a snap decision, drew a new bright line. Unlike an alcoholic, I could control my drinking. I could choose a relationship over a drink. Secret bonus fact: like a Skid Row drunk, my “punishment” lacked teeth. Not drinking on the nights I saw Helena would surely help me shed my “gin belly.” Also, truth be told, I preferred drinking alone. I agreed to Helena’s terms, and she didn’t question my compliance. She knew me to be a promise keeper, a maker of decisive moves. I stashed my martini in the fridge for later, when I was alone, and poured us each a tall, sparkly, boring-ass glass of Perrier. A few nights later Helena and I were at a bar with friends, waiting for our dinner table. Catching Helena’s not-happy glance, I followed her eyes to the half-drunk martini in front of me. Two shocks hit me, hard. I’d broken a promise, the one thing I’d always promised myself I wouldn’t do. And I had, in fact, chosen a cocktail over a relationship — and over my own integrity. This moment of truth happened in January. Four months later, Helena and I are friends, not lovers. And I haven’t had a drink since that night.***

Here’s what I’ve learned since I haven’t been drinking. Please note that I don’t say, “Since I got sober,” or even “Since I stopped drinking.” I say, “I’m not drinking right now.” More on this in a minute. Being with a bunch of people who are drinking was a lot more fun when I was drinking. I hang out in the same living rooms now that I hung out in then, back when I was drinking and laughing in a pleasant state of soft-focus. But now I’m sipping Perrier, laughing lamely, wondering what’s so funny. And wondering whether, when I was drinking, I slurred my words and got so vehement about nothing and was as difficult to connect with — as unreachable! — as my drinking friends are. As my abstinent months march on, I’m also noticing there’s usually a person or two or five in those living rooms who are abstaining from buzz beverages, too. Were the water drinkers there all along and I’m just noticing them now, the way you start seeing orange cars when you buy one? Have I simply shifted my attention away from the wild bunch and toward the “program people” in the room? Is sobriety a new L.A. fad — is sober the new drunk? Despite my tiny tendency to be dramatic, I’ve restrained myself from announcing my temporarily sober status. No Facebook posts, no tweets. When people offer me drinks, I simply say, “I’m not drinking right now.” Surprisingly, nearly everyone responds the same way. “That’s so great!” “What’s so great about it?” I ask, hoping to be convinced that my unpleasant experiment has some kind of unseen greatness to it. “I wish I could stop drinking.” “Why?” I ask. Pensive face, resigned shrug, sip of Malbec. “It would be good for me.” “I’d lose weight.” “I’d stop driving drunk.” “Why don’t you, then?” “I will, someday.” “I’ve tried. I couldn’t stick to it.” “I’d never make it through a day without my wine.” Another surprise, less than delightful: Not drinking is making me gain weight. When I first stopped, my friends squealed, “You’re gonna get so skinny!” (Did I mention I live in a city whose initials stand for Lifetime Anorexia?) I might be happily making my friends’ worst fears come true, if only I hadn’t traded my old lovers (Helena, alcohol) for my new ones (Ben, Jerry). Not my fault, the NIMH says. Deprived of alcohol’s feel-good dopamine surge, the body craves another source. “Sugar … releases opioids and dopamine and thus might be expected to have addictive potential.” Oh, joy: I’m not even an addict (more on this soon, as promised) but now I have to kick two drugs. My two favorite drugs. Just swell. For better and worse, online dating is out now, too. I don’t like the kind of people who meet for coffee. I like the kind of people who meet for drinks. Why, then, you might ask, are you putting yourself through this? I ask that of myself multiple times each day. I don’t know. No, really. I don’t. And I’m good with that. Maybe I’ve been in La-La too long, but I believe in not knowing. Some of the best things in my life have happened following oh-so-rare episodes of waiting-and-seeing, instead of my usual rushing-to-resolve-it-already. I stopped, initially, to give Helena and me our best shot. I continue to test the notion that my life — that I — might be better off, today or forever, without alcohol. I can always have a drink. I can’t always not-have-had a drink. Despite my resistance to sobriety as more than a brief experiment, I cannot deny the improvements as well as the discomforts not-drinking has brought me. I sleep better when I don’t attempt to douse my lifelong insomnia with a very tall nightcap. I’ve been more productive, since now I can work after dinner, so I’m making more money. I’m saving money, too: Even at five bucks a pint, Ben & Jerry’s is cheaper than Hendrick’s. I’ve grown closer to some of the other non-drinkers in the room and in “the rooms.” Sober people, I’ve discovered, tend to make really, really good friends — whatever makes them sober also makes them honest, direct and self-aware. I’m a better friend to myself, now, too. I keep hold of the things I think and feel after cocktail hour, the ideas I have, instead of losing them in a haze of table-dancing. At my age, improved memory is a benefit beyond AARP’s wildest promises. So, yes: It’s great, what I’m doing, even though I don’t know why I’m doing it, or for how long, or what, exactly, is so great about doing it. I do know this: I’m proud of myself. Waking up in the morning, knowing that I resisted Hendricks' siren call last night, is the opposite of how I feel, wincing at the empty Peanut Butter Core pint in last night’s trash. So shoot me: I still don’t think I’m an alcoholic. The NIH might not agree. “The term 'addiction,'” it says, “implies psychological dependence and thus is a mental or cognitive problem, not just a physical ailment.” Based on the fact that I stopped drinking and can’t, according to my own criteria, start again, I’ve diagnosed myself, instead, as what the CDC calls an “excessive” or “problem drinker” — now, a “problem not-drinker.” A November 2014 CDC study of excessive alcohol consumption in the United States concluded, “It is often assumed that most excessive drinkers are alcohol dependent. However … Most excessive drinkers (90%) did not meet the criteria for alcohol dependence.” That’s the CDC’s good news (for me). The bad news (for all of us): “Excessive alcohol consumption is responsible for 88,000 deaths annually.” I can vividly imagine those deaths. Because when I was drinking, even after the advent of Uber, I often drove buzzed — and by “often” I mean three or more nights a week. The fact that I never hurt myself or anyone else (to my impaired knowledge), or got stopped by the cops on one of the many occasions when my blood alcohol level would have sent me to jail, now seems nothing short of miraculous. So. Huh. Whether or not I’m an alcoholic, what I take from the science is that if I can’t drink “moderately” (the word that would be voted “least likely to succeed as Meredith’s lifestyle” by my friends, sober and not), I’m a problem drinker. And if I’m a problem drinker, I shouldn’t drink at all. That’s a problem for me. Because I still want to drink. I still plan to drink. Every day I think, “This is the day I get to have a martini.” Not just any martini, mind you, but a Hendrick’s martini, two ounces—no, four—shaken till nearly frozen, lovingly poured into an angular, tall-stemmed, arms-wide-open glass. I swoon, even now, at the thought of it. And then I think, “Get real. You don’t want one martini. You want a date with the bottle.” And so I sigh and go about my business, hoping that tomorrow will be the day I get to have a martini without having a problem.It started out as a night like many others. I was making dinner for Helena, the woman I’d been dating for a while. Candles flickered, curls of steam rose from prettily composed plates. It was my favorite moment of the day, neither too early nor too late to reasonably pour myself a drink. “Can I make you a cocktail?” I asked Helena, knowing that she’d say no. I’d suspected from the start that she and I weren’t it, that click-into-place fit, and this was one of the reasons. She didn’t dance on tables or quit jobs impulsively and she didn’t drink. A shared split of good Champagne to celebrate a book deal or a sweet summer night, sure. A few sips of one of my signature cocktails at one of my signature drinking-and-dinner parties, maybe. But she didn’t get wild and rowdy, laugh so hard she spit gin through her nose, text me first thing in the morning to ask what kind of damage she’d done the night before. You know what I mean. She didn’t drink. “I want to talk about your drinking,” Helena said. And right then and there, with our steaks au poivre cooling on our plates and a freshly shaken basil martini warming in my hand, I lost my amateur drinking status. Before we continue, a few words about me. Child of the '60s, uncomfortably past midlife, overly therapized, perennial seeker of all kinds of truth. Denial, delusion? Not my brand. I’m a memoirist and a journalist; for Christ’s sake, I wrote a book about addiction. So I paid attention when my alcohol consumption started escalating a few years ago, along with my affection for — or was it dependence on — the warm, loose, truthy-blurty blur that followed a cocktail or three. A series of recent losses (marriage, dear friend, beloved dad) had left me reeling, relocated and lonely in Los Angeles, where carbs are contraband, cocktails are compulsory, and everything stops for Happy Hour, every day of the week. Like a U-Haul lesbian couple, alcohol and I got serious fast. I cycled rapidly from wine with dinner to nightly complicatedly crafted cocktails, shaken and stirred by L.A.’s hippest mixologists, or homemade with ingredients I grew and brewed myself and consumed in my Silver Lake bungalow, with new friends or, more often, alone. “Seeker of truth,” remember? It concerned me, how much I loved to drink. So I started administering this little self-exam. I’d compare myself to the alcoholics I knew, ticking off the differences between us. I’d never had a blackout, or an overdose, or even a hangover. My drinking had never caused me to say anything I wish I hadn’t, or fall down, or puke. Unlike an alcoholic, I’d never lost anything to my drinking — time, a job, a relationship, my car keys. I’d never gotten a DUI. Most significantly — and this was my bright-line test, the notion to which I clung when I found myself counting down to happy hour at odd hours of the day —no one had ever expressed concern about my drinking. How could I have a drinking problem, when my drinking had never bothered me or anyone else? Until tonight. “You’re a different person when you drink,” Helena said. Everything in me rose up in rebellion against the sickening realization that I’d just flunked my own sobriety test. My bright line had been irrevocably crossed. Only one thing could restore me and my martini to our comfort zone. Helena had to take it back. “Of course I’m different when I drink,” I said. “That’s the whole point of drinking. Why would I consume all those liquid calories if I wanted to stay the same?” “You’re distant when you drink,” she said. “Unreachable. It makes me feel alone.” I extended my gently sweating martini glass, a three-olive branch. “Don’t feel alone,” I enticed her in my festive-sexy voice. “Drink with me.” Helena shook her pretty head. “I don’t want to be around you when you’re drinking. I don’t care what you do when you’re alone or with your friends, but from now on you can either drink, or you can spend time with me.” That’s what I get for dating a party-pooper, I thought — noting that I was taking full responsibility for my actions, something, I reminded myself, no addict would ever do. Looking longingly at my untouched, beckoning cocktail, I made a snap decision, drew a new bright line. Unlike an alcoholic, I could control my drinking. I could choose a relationship over a drink. Secret bonus fact: like a Skid Row drunk, my “punishment” lacked teeth. Not drinking on the nights I saw Helena would surely help me shed my “gin belly.” Also, truth be told, I preferred drinking alone. I agreed to Helena’s terms, and she didn’t question my compliance. She knew me to be a promise keeper, a maker of decisive moves. I stashed my martini in the fridge for later, when I was alone, and poured us each a tall, sparkly, boring-ass glass of Perrier. A few nights later Helena and I were at a bar with friends, waiting for our dinner table. Catching Helena’s not-happy glance, I followed her eyes to the half-drunk martini in front of me. Two shocks hit me, hard. I’d broken a promise, the one thing I’d always promised myself I wouldn’t do. And I had, in fact, chosen a cocktail over a relationship — and over my own integrity. This moment of truth happened in January. Four months later, Helena and I are friends, not lovers. And I haven’t had a drink since that night.***

Here’s what I’ve learned since I haven’t been drinking. Please note that I don’t say, “Since I got sober,” or even “Since I stopped drinking.” I say, “I’m not drinking right now.” More on this in a minute. Being with a bunch of people who are drinking was a lot more fun when I was drinking. I hang out in the same living rooms now that I hung out in then, back when I was drinking and laughing in a pleasant state of soft-focus. But now I’m sipping Perrier, laughing lamely, wondering what’s so funny. And wondering whether, when I was drinking, I slurred my words and got so vehement about nothing and was as difficult to connect with — as unreachable! — as my drinking friends are. As my abstinent months march on, I’m also noticing there’s usually a person or two or five in those living rooms who are abstaining from buzz beverages, too. Were the water drinkers there all along and I’m just noticing them now, the way you start seeing orange cars when you buy one? Have I simply shifted my attention away from the wild bunch and toward the “program people” in the room? Is sobriety a new L.A. fad — is sober the new drunk? Despite my tiny tendency to be dramatic, I’ve restrained myself from announcing my temporarily sober status. No Facebook posts, no tweets. When people offer me drinks, I simply say, “I’m not drinking right now.” Surprisingly, nearly everyone responds the same way. “That’s so great!” “What’s so great about it?” I ask, hoping to be convinced that my unpleasant experiment has some kind of unseen greatness to it. “I wish I could stop drinking.” “Why?” I ask. Pensive face, resigned shrug, sip of Malbec. “It would be good for me.” “I’d lose weight.” “I’d stop driving drunk.” “Why don’t you, then?” “I will, someday.” “I’ve tried. I couldn’t stick to it.” “I’d never make it through a day without my wine.” Another surprise, less than delightful: Not drinking is making me gain weight. When I first stopped, my friends squealed, “You’re gonna get so skinny!” (Did I mention I live in a city whose initials stand for Lifetime Anorexia?) I might be happily making my friends’ worst fears come true, if only I hadn’t traded my old lovers (Helena, alcohol) for my new ones (Ben, Jerry). Not my fault, the NIMH says. Deprived of alcohol’s feel-good dopamine surge, the body craves another source. “Sugar … releases opioids and dopamine and thus might be expected to have addictive potential.” Oh, joy: I’m not even an addict (more on this soon, as promised) but now I have to kick two drugs. My two favorite drugs. Just swell. For better and worse, online dating is out now, too. I don’t like the kind of people who meet for coffee. I like the kind of people who meet for drinks. Why, then, you might ask, are you putting yourself through this? I ask that of myself multiple times each day. I don’t know. No, really. I don’t. And I’m good with that. Maybe I’ve been in La-La too long, but I believe in not knowing. Some of the best things in my life have happened following oh-so-rare episodes of waiting-and-seeing, instead of my usual rushing-to-resolve-it-already. I stopped, initially, to give Helena and me our best shot. I continue to test the notion that my life — that I — might be better off, today or forever, without alcohol. I can always have a drink. I can’t always not-have-had a drink. Despite my resistance to sobriety as more than a brief experiment, I cannot deny the improvements as well as the discomforts not-drinking has brought me. I sleep better when I don’t attempt to douse my lifelong insomnia with a very tall nightcap. I’ve been more productive, since now I can work after dinner, so I’m making more money. I’m saving money, too: Even at five bucks a pint, Ben & Jerry’s is cheaper than Hendrick’s. I’ve grown closer to some of the other non-drinkers in the room and in “the rooms.” Sober people, I’ve discovered, tend to make really, really good friends — whatever makes them sober also makes them honest, direct and self-aware. I’m a better friend to myself, now, too. I keep hold of the things I think and feel after cocktail hour, the ideas I have, instead of losing them in a haze of table-dancing. At my age, improved memory is a benefit beyond AARP’s wildest promises. So, yes: It’s great, what I’m doing, even though I don’t know why I’m doing it, or for how long, or what, exactly, is so great about doing it. I do know this: I’m proud of myself. Waking up in the morning, knowing that I resisted Hendricks' siren call last night, is the opposite of how I feel, wincing at the empty Peanut Butter Core pint in last night’s trash. So shoot me: I still don’t think I’m an alcoholic. The NIH might not agree. “The term 'addiction,'” it says, “implies psychological dependence and thus is a mental or cognitive problem, not just a physical ailment.” Based on the fact that I stopped drinking and can’t, according to my own criteria, start again, I’ve diagnosed myself, instead, as what the CDC calls an “excessive” or “problem drinker” — now, a “problem not-drinker.” A November 2014 CDC study of excessive alcohol consumption in the United States concluded, “It is often assumed that most excessive drinkers are alcohol dependent. However … Most excessive drinkers (90%) did not meet the criteria for alcohol dependence.” That’s the CDC’s good news (for me). The bad news (for all of us): “Excessive alcohol consumption is responsible for 88,000 deaths annually.” I can vividly imagine those deaths. Because when I was drinking, even after the advent of Uber, I often drove buzzed — and by “often” I mean three or more nights a week. The fact that I never hurt myself or anyone else (to my impaired knowledge), or got stopped by the cops on one of the many occasions when my blood alcohol level would have sent me to jail, now seems nothing short of miraculous. So. Huh. Whether or not I’m an alcoholic, what I take from the science is that if I can’t drink “moderately” (the word that would be voted “least likely to succeed as Meredith’s lifestyle” by my friends, sober and not), I’m a problem drinker. And if I’m a problem drinker, I shouldn’t drink at all. That’s a problem for me. Because I still want to drink. I still plan to drink. Every day I think, “This is the day I get to have a martini.” Not just any martini, mind you, but a Hendrick’s martini, two ounces—no, four—shaken till nearly frozen, lovingly poured into an angular, tall-stemmed, arms-wide-open glass. I swoon, even now, at the thought of it. And then I think, “Get real. You don’t want one martini. You want a date with the bottle.” And so I sigh and go about my business, hoping that tomorrow will be the day I get to have a martini without having a problem.

I’m a pedophile, but not a monster

We're re-running this story as part of a countdown of the year's best personal essays. To read all the entries in the series, click here.

I was born without my right hand. As a child, this deformity quickly set me apart from my peers. In public I wore a prosthesis, an intimidating object to other youngsters because of its resemblance to a pirate’s hook. Even so, I wore it every day; I felt inadequate without it. I was shy, uncoordinated and terrible at sports, all of which put me on the outs with other boys my age. But I was good at drawing and making up stories for my own entertainment, and I spent more and more time in my own head, being a space adventurer or monster wrangler or whatever character I could think up. These would ultimately prove to be useful skills, but for now they only served to further alienate me from other kids. On top of it all, I still struggled with bladder control—likely due to my heaping pile of insecurities, to which this problem only added more—well into my elementary school years.But none of this would compare to the final insult the universe would deal me. I’ve been stuck with the most unfortunate of sexual orientations, a preference for a group of people who are legally, morally and psychologically unable to reciprocate my feelings and desires. It’s a curse of the first order, a completely unworkable sexuality, and it’s mine. Who am I? Nice to meet you. My name is Todd Nickerson, and I’m a pedophile. Does that surprise you? Yeah, not many of us are willing to share our story, for good reason. To confess a sexual attraction to children is to lay claim to the most reviled status on the planet, one that effectively ends any chance you have of living a normal life. Yet, I’m not the monster you think me to be. I’ve never touched a child sexually in my life and never will, nor do I use child pornography.

But isn’t that the definition of a pedophile, you may ask, someone who molests kids? Not really. Although “pedophile” and “child molester” have often been used interchangeably in the media, and there is some overlap, at base, a pedophile is someone who’s sexually attracted to children. That’s it. There’s no inherent reason he must act on those desires with real children. Some pedophiles certainly do, but many of us don’t. Because the powerful taboo keeps us in hiding, it’s impossible to know how many non-offending pedophiles are out there, but signs indicate there are a lot of us, and too often we suffer in silence. That’s why I decided to speak up.

The Discovery of an Alternate Sexuality:

Many gays begin to recognize their sexual preferences sometime around puberty, if not before. For me it was the same. I was about 12 when the first inklings of a sexual preference bubbled up in me, though at the time I thought little of it. As I turned 13 it occurred to me that what I initially took as a phase had begun to solidify into something more troubling. Even so, at this point I could still convince myself that I was within the realm of normalcy. Then something happened that all but removed my ability to continue this self-denial: my Eureka Moment.

One day, as I was sketching in my grandparents’ living room, a neighbor of theirs came to visit with his seven-year-old daughter in tow. At first I hadn’t noticed her because she was quiet. I only heard my grandpa and his neighbor chatting in the kitchen while I sketched. Soon the little girl walked into the dining room and stood at the archway entrance to the living room, watching me draw. I can still see her today in my mind’s eye: dressed in blue jeans and a nearly matching denim jacket, with pristine blue eyes and a halo of wispy blond curls framing her face. She seemed somehow larger than life and almost ancient in the way she stood so perfectly still. Then, just like that, she was gone; she and her father left. That singular moment, though it could scarcely have lasted more than a few minutes, has become seared into my memory.

He Touched Me:

So how had this happened? Well, I have a pretty good idea. When I was seven years old, I was fondled in the front yard of my grandparents’ home by a man I barely knew. It was a one-time event in my life and not a particularly traumatic one. A man I’ll call Hans, a German who was acquainted with my uncle and aunt from when they lived in Nuremberg, had come to visit America. He spent a day and a night at their place, and they lived next door to my family along with my grandparents, who shared their two-story brick house. That day, the man lingered in the house with my grandma, who was stuck with him while everyone else had gone to work, and as neither could speak the other’s language, it quickly became uncomfortable for both.

Grammy’s solution was to send Hans outside with one of the grandkids. As I happened to be in the room at the time, I was assigned the task. “Take him out and show him Papa’s garden,” she told me. “Tell him the names of the vegetables. He’d probably enjoy that.” I agreed. Besides, even though I knew not a whit of German, I was very much at ease in Hans’s presence. He was painfully thin, with a messy mop of hair and large glasses. I should point out that the men in my life, including my father, were gruff blue-collar types who could intimidate me. Hans was different: gentle, soft-spoken and appealingly awkward—a lot like me!

I took the man’s right hand with my left (my good hand) and led him out into the garden, which took up most of the front lawn at my grandparents’ place. I escorted my new friend down the rows of veggies, calling out each one as we passed it, and Hans would gleefully parrot the names. This went on until we made our way through the entire garden. I was proud to find myself educating an adult rather than the other way around. When the English lesson was over, Hans plopped himself down on a patch of earth near the garden and patted the spot next to him, indicating he wanted me to sit there. I did. I couldn’t believe this peculiar man I barely knew was so eager to connect with me, the weird little kid nobody liked. It felt good.

For long minutes we simply enjoyed each other’s company. Then, out of the blue, Hans slipped a hand into my shorts, even though we were only about 30 feet from the poorly paved country road that meandered through this stretch of country. This went on for several minutes. I was confused but not frightened or troubled. The only thing I could think to say while this was happening was “Peepee,” continuing the English lesson with my pet name for my genitalia even in the midst of my own abuse. Hans chortled and repeated the word: “Peepee.” Eventually this came to an end, and Hans, having gotten what he wanted, shooed me away. I can’t imagine why it didn’t occur to him that I would immediately rat him out; maybe he knew and just didn’t care. Anyway, he could hardly ask me not to, could he? I raced back to Grammy and promptly informed her of what had happened. She deliberated over what to do, in the end asking me to keep it a secret from everyone, including my parents, and ordering me to stay away from Hans. No authorities were called, and life went on as usual. Hans stayed that evening with my uncle and aunt and left the next day. I never saw him again.

Ultimate Causes:

It’s easy to assume that pedophilia is always the result of some early sexualization or abuse, and certainly there seems to be a connection in some cases. However, evidence suggests there’s no magic bullet that pedophilia can be traced back to. For every pedophile who was sexually abused as a child there’s another who wasn’t. Likewise, most abuse victims never manifest pedophilic desires. Some researchers surmise that pedophilia can be traced back to genetics. Others believe the cause is congenital, and still others that it’s environmental. Personally, I think the ultimate cause is likely some combination of those, and that it varies from person to person.

Another issue is the role feelings of inadequacy play in forming our sexuality. Pedophilia may not arise from such fears (otherwise there’d be a lot more pedophiles), but those fears can certainly reinforce it. I think it’s safe to say that many pedophiles have deep-seated feelings of inferiority in one way or another, or at least we did when our sexuality was forming, and this becomes a downward spiral during puberty and beyond. Anything can be the trigger of this: disabilities, weight issues, or just general feelings of unattractiveness to peers. These feelings can be influential on one’s developing sexuality, such that even the severe cultural taboo is not enough to override it. Indeed, the taboo itself can negatively influence these vulnerable children.

I recall an event from when I was 11, sitting in the family jeep with my dad and his friend Andy when a news piece on the radio reported the sexual abuse of a girl, to which my dad said to his friend something like, “They should take people like that and place weights on top of their genitals until they smash.” Pretty horrific imagery for an 11-year-old to process, and I couldn’t help but sympathize with the abuser. After all, I could recall my own molestation perfectly, and I hardly felt it warranted that kind of response.

The bile has only multiplied since then, and I believe all that hatred just serves to reinforce pedophilia in youngsters predisposed to it. It’s a form of cognitive bias called the Backfire Effect or polarization. Everyone does this to some extent. When challenged on deeply held beliefs, no matter how uncertain or incorrect they may be, we tend to dig in our heels. With sexuality, that effect is likely magnified because there’s a physiological component, a drive every bit as powerful as belief. In essence, your brain knows what it likes and isn’t going to take no for an answer. For that reason, the nature or nurture question with respect to sexual preference is ultimately irrelevant—it becomes all but hardwired soon enough, until it’s all you know. And it’s self-reinforcing, no matter how much you wish to dig it out. Eventually it all tangles together with the rest of who you are.

Getting Schooled:

Things went along OK until I was two years away from graduating college. I began to smoke pot, a drug I’d experimented with after high school but didn’t much care for then. I didn’t like it the second time around either; it made me anxious more often than not. But I did it anyway, largely because many people I respected smoked it, and I wanted to be more like them. I was trying desperately to reshape my identity before I was thrown out into the real world. I’d even begun working out, lifting weights and exercising to get in better shape. On the outside I might’ve seemed pretty normal, but on the inside I was screaming in terror at the prospect of having to “grow up” and be “normal”—which to me meant getting a real job, finding a girlfriend, eventually getting married and raising a family. Oh, I wanted to be normal, believe me, yet I knew myself well enough to know I wouldn’t be able to carry that charade off for long, and every fiber of my being resisted the forced transformation.

After graduation I fell into the deepest pit of despair imaginable, one that lasted several years, and I’ve only just begun to pull myself out of it. You can’t experience that much blind terror and pain for that long without being seriously impacted by it. I still worked out every other day, so I was hurting constantly, since depression saps your brain of the feel-good chemicals that helps to counteract pain; but I felt something, and that was better than the emotional numbness that had overtaken me. Thus, my project to remake myself into a regular person a complete failure, I retreated inward like a kicked dog, often spending days on end in my bedroom. At the nadir of my depression I was contemplating suicide daily; some days I could think of little else. I found some relief in opiates, which I had to obtain illegally because doctors won’t prescribe them for depression and anxiety. The occasional hydrocodone gave me a moment of respite from the agony I was going through. I’d tried antidepressants, but they were a joke.

In the midst of that dark era in my life, I discovered an unhealthy pedophile forum. Nothing illegal was happening there, but many of its most influential members were pro-contacters, meaning they believed that sex with children was theoretically OK and supported the elimination of age of consent laws. That forum still exists and I won’t name it here, but suffice it to say, I found myself taking up the same pro-contacter chants, if only to feel like I belonged somewhere. At the time it was all that was available in terms of an actual pedophile community, and I had nothing left to lose by joining the cause, misguided though it was, and even decided to out myself on that forum. Over the ensuing years, though, I was often at odds with the pro-contacters and flitted in and out of their clique; I wanted desperately to be friends with people who shared my sexual orientation, even if they held crazy beliefs, but I could never quite reconcile with their viewpoint.