Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 744

June 19, 2016

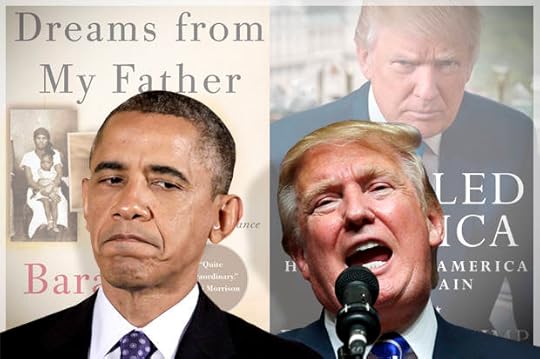

Communicator-in-chief: Where Obama’s rhetoric illuminated a complex world, Trump’s deceptive dialect dumbs down

Barack Obama, Donald Trump (Credit: Reuters/Yuri Gripas/Brian Snyder/Salon)

In America’s slow and steady move from a literary culture to an audio-visual culture with literary accessories like Twitter feeds and text messages, much of the nation has lost its appreciation for eloquence. Language is communicative, but in political or artistic context, it is also aspirational. The poetic grandeur of Lincoln’s “House Divided” address to the Illinois State Legislature, the sermonic beauty of King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, and the anthemic triumph of Kennedy’s inaugural address map a future of better and boundless possibility not merely with content, but with style of articulation. If Marshall McLuhan was right with his now clichéd proclamation that the “medium is the message,” it is not too damnable a distortion to apply his theory to rhetoric itself, and make the determination that political leaders have a message, and are able to delineate a vision of the world, not only with what they say, but the way in which they choose to say it.

In a devolution that puts to bed fanciful notions of progress, America has transitioned from eight years of one its most elegant and intelligent presidents to consideration of a man who, according to several studies, speaks at a fifth grade level. The right wing, often unable to recognize the sound of a sophisticated voice, consistently mocks Barack Obama for his use of a teleprompter, as if he is the first politician to give prepared remarks or that the teleprompter itself, as opposed to words printed on paper, is somehow worthy of ridicule. To actually gain insight into the rhetorical gifts of the current president, along with the insipid ramblings the Republican nominee for president, Americans should turn to the written word.

Barack Obama began his memoir “Dreams from My Father” with the following paragraph:

A few months after my twenty-first birthday, a stranger called to give me the news. I was living in New York at the time, on Ninety-fourth between Second and First, part of that unnamed, shifting border between East Harlem and the rest of Manhattan. It was an uninviting block, treeless and barren, lined with soot-colored walk-ups that cast heavy shadows for most of the day. The apartment was small, with slanting floors and irregular heat and a buzzer downstairs that didn’t work, so that visitors had to call ahead from a pay phone at the corner gas station, where a black Doberman the size of a wolf paced through the night in vigilant patrol, its jaws clamped around an empty beer bottle.

The paragraph reads like a passage from a fine novel. It describes a world of complexity and irony – not fit for simple explanations or prescriptions – but one where questions outnumber answers, and individuals must engage in the art of self-discovery, always turbulent and painful, to even hope to find clues in the intractable mysteries of life. It is literature. “Dreams from My Father” follows in similar style, and joins the tradition of memoir and novel attached to coming of age, formative experience, and individualistic transformation.

Donald Trump begins his latest book, charmingly titled “Crippled America,” with the following “sentences”:

Some readers may be wondering why the picture we used on the cover of this book is so angry and so mean looking. I had some beautiful pictures taken in which I had a big smile on my face. I looked happy, I looked content, I looked like a very nice person, which in theory I am. My family loved those pictures and wanted me to use one of them. The photographer did a great job. But I decided it wasn’t appropriate. In this book we’re talking about Crippled America—that’s a tough title. Unfortunately, there’s very little that’s nice about it. Hence, the picture on the cover. So I wanted a picture where I wasn’t happy, a picture that reflected the anger and unhappiness that I feel, rather than joy. There’s nothing to be joyful about. Because we are not in a joyous situation right now. We’re in a situation where we have to go back to work to make America great again. All of us. That’s why I’ve written this book. People say that I have self-confidence. Who knows? When I began speaking out, I was a realist. I knew the relentless and incompetent naysayers of the status quo would anxiously line up against me, and they have.

The world Trump depicts is simple, and for the simple-minded. The state of the country, and the world, is static and categorical. It is bad. It is terrible. He can make it good. Only he can make it good. He will make it great (the style is contagious).

Trump’s appeal is an indictment of the public education system of America, and the American cultivation of an anti-intellectual culture suspicious of eloquence and learnedness. It dates back to the 1950s when many American voters mocked and derided Adlai Stevenson as an “egghead,” as if having an educational pedigree was a liability. It is important to remember that Stevenson’s populist opponent was Dwight Eisenhower, a former general whose rhetoric reads like Shakespeare in comparison to the childlike incoherence of the average Trump speech.

Many defenders of Trump’s blather claim that he is speaking directly to his poorly educated constituency in a language that they can understand and appreciate. In that sense, Trump sympathizers will claim, it is a truly democratic act of charity for a man who has an Ivy League education to communicate, by design or default, with an elementary school style. Those who make this argument confuse pandering with leadership. Leaders should challenge, not coddle their audiences.

Trump’s dialect is deceptive, because it implies that complicated institutions need only the right authority figure to work smoothly in favor of the general public, and that the world is not always at contradiction, but that it is rather straightforward – like a formulaic television series. The continual debasement of language in American culture played right into Trump’s miniature hands. To track the preferred method of Internet argument from the popularity of blogs to the ubiquity of Twitter is to monitor a culture increasingly accustomed to short and simple explanations and rebuttals.

The rhetoric of Barack Obama – whether in oratorical high moments like the “Yes We Can” speech, the address at the memorial for the victims of the 2011 Tucson massacre, or the eulogy for Beau Biden – illustrates a “heretic against the religion of certainty,” as he called himself in “Dreams from My Father.” Obama’s evasion of category – in word and deed – frustrates both admirers and adversaries alike. His rhetoric speaks of a world in need of investigation, and a world in which workmanlike dedication to rational and thoughtful reform can likely lead to improvements, but there is no guarantee. Whether or not his policies followed through on his rhetoric is a debate that will long take place among historians and social critics, but one of the most important functions of the presidency is not just as commander-in-chief, but what one book calls “communicator-in-chief.”

As communicator-in-chief, Barack Obama has attempted to elevate the discourse throughout a culture committed to lowering every standard of self-expression. Trump embraces the decline, and even enables people to feel good about becoming part of it. A significant part of the nearly universal contempt for “elites” in American politics is a discomfort with illustrations of intelligence. Rather than looking at the president as a person to whom people should aspire, too many Americans look at the president, as they did with George W. Bush, as someone they would “like to have a beer with.” Obama seems like a much more appealing barroom companion than Bush or Trump, but his language does not massage the insecurities of those who would make excuses for their ignorance. One need not graduate from Harvard Law or the Wharton School of Finance to claim intelligence or culture, but one needs to practice the discipline of intellectual rigor. Eloquent language emphasizes the necessity and nobility of that discipline, while ignorant language encourages a shallow culture of philistine complacency.

Oliver Jones, a brilliant Oxford graduate and British writer, offers an analysis, stunning in its depth and clarity, of Donald Trump in his new book, “Donald Trump: The Rhetoric.” The short exploration of Trump’s triumph manages to entertain, even as it terrifies. Jones writes that Trump is the “equivalent of an untrained actor stunning audiences with his artless sincerity.” He “speaks to a theoretical section of the electorate that is not politically aware, does not care too much about policy, has a simplistic view of politics and is unsympathetic towards political process and toward compromise.”

Trump’s style and message, in this sense above all others, contrasts with Obama, who always delivers his position with a package constructed out of the messy fibers of democracy – a language that underscores the complexity of the political process and necessity of ideological compromise.

The dichotomy and disparity separating the rhetoric of Trump and Obama is not merely contemporary. It flashes far back into the origins of democratic governance and balance of powers, always at odds against the tyranny of monarchy and the nightmare of mob rule. As Jones puts it, “Trump replaced the political virtues of Aristotle, Plato, and the founding fathers – sagacity and wisdom – with the virtues of the action movie hero: masculine indifference, anti-intellectualism, ‘guts’, and a steady source of one-line put downs.”

American rhetoric has always acted as host to a larger conflict of perceptive values. It is the language of the cheap adman, the conniving televangelist, and the demagogic politico. It is also the language of Jefferson, Lincoln, King, and Eleanor Roosevelt – the language of Whitman, Ellison, Dickinson, and Morrison.

Although Hillary Clinton lacks Obama’s sense of poetry and his inspired gift for oratory, she does, at least, communicate in the language of policy. Her language (and again, policy is a separate matter) communicates the challenge of the political process. It is difficult work to legislate and govern, and it requires an acrobatic mind able to adjust and adapt in an attempt to balance multiple tasks, duties and contradictions all at the same time.

Jesse Jackson, who has given some of the greatest speeches in political convention history, once explained that leaders should elevate people with their language, not speak down to them or even meet them where they are at. As much of the American public becomes politically illiterate, it is important to have a leader who will confront that illiteracy, and advantageously exercise the bully pulpit to enlarge the mind of the voter, and expand the possibilities of political understanding.

Obama, with his books, speeches and public persona, made a valiant effort in the art of civility and sophistication. Oliver Jones writes that Trump has mastered a message of “down-to-earth vulgarity.” He is the pop-cultural candidate – the candidate of the Kardashians, the mindless tweet, and the incoherent celebrity rant on social media. Far from offering the service of elevation, he can only speak down to people, and bring them, along with American political culture, down to the depths of his rhetorical gutter.

June 18, 2016

My father won’t read this, and that’s OK with me

For the past few years, I’ve had a tumultuous relationship with Facebook. A few days ago, I was reminded why.

I was at an afterthought of a campus fitness center, sandwiched between a ’90s step climber and the loudest treadmill known to man on a lonely spinning bike, pedaling my way through a 45-minute routine I’d internalized from the cycling studio I frequented before my husband I moved across the country. Want to see something comical? Find me on the bike, riding to the beat of my own drum. I have zero rhythm, so my self-directed spinning is a lot of erratic standing up and sitting down (“jumps”), clunking my sternum on the handlebars (“wide arm presses”), and running my legs like a rabid hamster on a wheel (“sprinting”).

Still, despite the general flailing quality of my workout, I sweated, got breathless, and achieved a mental state of honed motivation. Maybe it was the inspirational poster taped to the otherwise-blank wall my bike faced: a man’s long, brown forearm palms a ruddy basketball. Superimposed over the image are the words “Winners never quit and quitters never win.”

We have Vince Lombardi to thank for this kick-in-the-pants of a sentence—and as I slowed my pedaling (“this is how we go home,” I could hear my old spinning instructor yelling), I felt like I’d already won. So it wasn’t quitting when I looked at my phone, and it wasn’t quitting when I checked Facebook—that’s what I told myself. What was quitting was me abandoning the bike as I started to read the post of an acquaintance, a woman who had that day lost her dad.

“I didn’t expect to have such a short time with him,” the woman admitted. News like this always wrecks me—a week earlier, a man with whom I’d only occasionally played poker in grad school shared paragraphs about his just-deceased dad, paragraphs at which I wept until I finally quarantined myself in the bathroom—but this woman’s loss hit me more personally: her father and mine share the same first name.

I’d rather not mention that name. After all, one of the reasons I’ve long been freaked out about Facebook is because I was raised—by my parents, but especially by my dad—to be a private person.

How does that work for a writer? You might ask yourself. Not super well, is how I respond. And yet, surely Vince Lombardi has applicable wisdom: “The measure of who we are is what we do with what we have.” I’ve been fortunate enough to develop the confidence to believe that what I have is my mind and my voice, and for that I need to thank my dad.

He’s alive and well, I should add, but hey—there’s a fair chance he might not read this. I’m pretty sure a part of him still wishes I’d done something involving math. I have a solid suspicion that he only finds my writing when my mom shows it to him—and that’s okay.

***

When I was a kid, I saw other dads. They were everywhere, wearing Hawaiian shirts and mustaches, carrying wallets and drinking beers. They were at family gatherings, doling out noogies, stewing in corners. On television, they gave stumbling advice or blathered into obnoxious temper tantrums or flaunted their cosmic ineptitude at the flames of the charcoal grill. Sitcom dads got teased by wives and taunted by children until the moment of crisis, when violins swelled, and fatherly advice was proffered like Bactine for a skinned knee. It hurts but it’s good.

The dads I met in real life wore shirts and mustaches, too, but they also wore red vests and headdresses. My dad was one of them. For tens years, he and I participated in a program called Indian Princesses. Let’s not linger on the political incorrectness. Sponsored by the local YMCA, this father-daughter bonding jamboree was like Girl Scouts without the prissiness or the cookies. We held monthly meetings (crafts for the daughters, cigars for the dads) and went on campouts where we practiced archery, paddled aluminum canoes, rode slow horses, and climbed rock towers with names like Mount Wood.

We had nicknames, too, like “Singing Bird” and “Screaming Eagle.” That was me and my dad, the quietest members of the “Arapaho tribe.”

To tell you the truth, I envied the other girls with their jouncy dads. Now, I’m in my thirties, and my peers are dads like those guys—they all majored in communications or marketing. The other Arapaho dads were outgoing and funny, especially “Hairy Chest,” who could send the entire tribe into a giggle fit with Elvis impersonations. I envied girls with braggy dads who boasted of their daughter’s accuracy at the rifle range; girls with lenient dads, who let their the daughters fork tunnels through mess hall mashed potatoes. I even envied the other dads, who encouraged me to goof around and my dad to crack a grin over late-night games of Hearts.

I’m not sure when the envying wore off, but one year it did, like a puddle on hot asphalt, gone in an instant. Perhaps I’d turned ten, a double-digit age that meant adult. Instead of wanting a dad who treated me like a princess—and not just like an Indian Princess, but a princess princess—I became grateful for the way my father held me to a higher standard.

That’s what it felt like, anyhow, when it was just the two of us in a canoe, paddling down the Rock River under the steady gaze of the towering statue, Black Hawk (or The Eternal Indian). Rowing is hard, and it’s especially hard when you’re a twelve-year-old girl who can’t even do a push-up. Other canoes ferried groups of four: two dads and two daughters so the Princesses wouldn’t have to do the grunt work. In our vessel, it was just Screaming Eagle and me.

My friends waved as they passed us by. I could hear them singing along with the Spice Girls and Green Day and No Doubt they played on their portable CD players. My hands were already blistering, I could tell; they smarted when I repositioned them on the oars. But even though we were perpetually getting lodged in rocks, the prow of our canoe smacking into sand and silt, even though our journey down the river took twice the time of the other Arapahos and sometimes we heard nothing but the sound of our paddles slapping the water, an invisible fish leaping, my dad and I were steering that boat together, Singing Bird and Screaming Eagle, fueled by the cans of Canfields Diet Crème Soda he’d stashed in the pockets of his windbreaker.

***

Winners never quit and quitters never win: My dad taught me there are so many ways to win every day. Winning is a personal matrix, the little choices that add up to character. Of course winning is reaching the top of Mount Wood before anyone else (the way my best friend did, dinging a hidden bell), but winning is also dealing with wet dock shoes when your daughter can’t get the hang of placing just the blade—and not the oar’s shaft—in the water. Winning is being together in the canoe.

Winning, my father taught me, is using one plate instead of two, is drinking the morning’s cold coffee instead of buying a Starbucks in the middle of the afternoon. Winning isn’t not procrastinating—winning is staying up all night when you have a project or a report due the next day, when you have a deadline, when you have the stamina to think a little harder. Winning, my dad taught me, is thinking, thinking not only in an intellectual context, but thinking about the person you want to be in this world.

Are you a person who’s ever had to buy a snack from the gas station? A person who’s been on a road trip and wondered about the cheapest snack? FYI, it’s the Planter’s peanut tube, $.59 for one or 2/$1, which is why you’ll always find a sleeve of Heat Peanuts in my glove compartment. Does my dad love peanuts? Not particularly. He loves the value of a dollar. Because a dollar isn’t just a dollar, but a thought, a question, a quandary, a choice: How do you want to use what you’ve earned?

There are all kinds of facts I could tell you about my father, but none of those would begin to explain why I feel closest to him in my family. He may know the least about me: I would be ashamed, for instance, if he knew how much money I’d spent on clothes, shoes, purses, even books—after all, I learned as a teenager, CDs were a waste. “What are you going to do with those?” my dad would ask me when I filled an under-the-bed plastic storage container with music. I was incredulous then—and incredulous again, last year, when I returned to my parent’s house and dumped all those CDs at Goodwill.

He doesn’t know my darkest secrets and, on the surface, we have so little in common. He likes ribs; I like tuna tartare. He likes “cocoa mocho frappuccinos”; I like espresso and water. He likes his half-acre of lawn; I like city blocks. His vices are seeing a rebirth (stop smoking, Dad); mine (ice cream has yet to find its way into my new refrigerator) are in constant curtailment. And yet when we talk on the phone, we can spend an hour comparing our dogs and our weather, our jobs and our politics, and I marvel that two people can feel so close. I wonder if he feels that way, too.

What, then, is that space between the river’s bottom and the froth the canoe leaves in its wake on the surface? If neither our secrets nor our affinities bind me and my father, what does? Somehow, that mysterious something seems bigger, and though I’m not a math person like my dad, I’m certain the middle darkness of a river encompasses its greatest area.

Is this nuance? Logic? Pondering? Or simple curiosity? Whatever that quality of thought is that leads me to ask questions about the top and the bottom, the end and the beginning—that quality of thought is a product of my dad, and it’s nothing I’d ever be able to fit into a Facebook post. After all, he would hate to think that strangers were learning so much about him.

This isn’t to begrudge those who share their losses on social media—it’s only to say I know, in the pit of my stomach, that when that time comes, for me to do so would be to wrong my dad.

For now, I say sorry. Because Father’s Day is coming and I can’t not think about how lucky I am to have the Dad I do. I want to honor our relationship—as quiet and indefinable as it might be—while he’s around to hear it. Yes, I’m thankful for his wisdom and quirks, grateful for everything he’s taught me about the world. But I’m also glad for everything he hasn’t taught me. He hasn’t taught me to be dependent on men; he hasn’t taught me to see myself as an enemy or a princess—in fact, by seeing me as a person with a mind and a heart rather than as a woman, he’s taught me to look past some of the most biological parts of myself.

Most days, I’m ambivalent-to-disinterested in starting a family. Show me a baby and, reflexively as a knee tapped with one of those tiny hammers, I’ll cringe. There’s only one thing that starts to sway me, and given the context of this confession, it should come as no surprise: it’s my father. I can see exactly one good thing about having children, and that the chance to introduce a young person to my dad.

He’s the sort of understated person who can’t be summed up in a Lombardi-ism. He’s not a coach or a champ, a jock or geek. He’s the quiet, goofy, introspective, dog-loving man who taught me to guard myself and my privacy, to honor my thoughts—and the man who grants me the courage to give all that away.

A modern-day Joseph McCarthy: Donald Trump is the latest in a long line of American demagogues

Donald Trump (Credit: AP/Michael Conroy)

There’s a virus infecting our politics and right now it’s flourishing with a scarlet heat. It feeds on fear, paranoia and bigotry. All that was required for it to spread was a timely opportunity — and an opportunist with no scruples.

There have been stretches of history when this virus lay dormant. Sometimes it would flare up here and there, then fade away after a brief but fierce burst of fever. At other moments, it has spread with the speed of a firestorm, a pandemic consuming everything in its path, sucking away the oxygen of democracy and freedom.

Today its carrier is Donald Trump, but others came before him: narcissistic demagogues who lie and distort in pursuit of power and self-promotion. Bullies all, swaggering across the landscape with fistfuls of false promises, smears, innuendo and hatred for others, spite and spittle for anyone of a different race, faith, gender or nationality.

In America, the virus has taken many forms: “Pitchfork Ben” Tillman, the South Carolina governor and senator who led vigilante terror attacks with a gang called the Red Shirts and praised the efficiency of lynch mobs; radio’s charismatic Father Charles Coughlin, the anti-Semitic, pro-Fascist Catholic priest who reached an audience of up to 30 million with his attacks on Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the New Deal; Mississippi’s Theodore Bilbo, a member of the Ku Klux Klan who vilified ethnic minorities and deplored the “mongrelization” of the white race; Louisiana’s corrupt and dictatorial Huey Long, who promised to make “Every Man a King.” And of course, George Wallace, the governor of Alabama and four-time presidential candidate who vowed, “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.”

Note that many of these men leavened their gospel of hate and their lust for power with populism — giving the people hospitals, schools and highways. Father Coughlin spoke up for organized labor. Both he and Huey Long campaigned for the redistribution of wealth. Tillman even sponsored the first national campaign-finance reform law, the Tillman Act, in 1907, banning corporate contributions to federal candidates.

But their populism was tinged with poison — a pernicious nativism that called for building walls to keep out people and ideas they didn’t like.

Which brings us back to Trump and the hotheaded, ego-swollen provocateur he most resembles: Joseph McCarthy, US senator from Wisconsin — until now perhaps our most destructive demagogue. In the 1950s, this madman terrorized and divided the nation with false or grossly exaggerated tales of treason and subversion — stirring the witches’ brew of anti-Communist hysteria with lies and manufactured accusations that ruined innocent people and their families. “I have here in my hand a list,” he would claim — a list of supposed Reds in the State Department or the military. No one knew whose names were there, nor would he say, but it was enough to shatter lives and careers.

In the end, McCarthy was brought down. A brave journalist called him out on the same television airwaves that helped the senator become a powerful, national sensation. It was Edward R. Murrow, and at the end of an episode exposing McCarthy on his CBS series See It Now, Murrow said:

“It is necessary to investigate before legislating, but the line between investigating and persecuting is a very fine one, and the junior senator from Wisconsin has stepped over it repeatedly. His primary achievement has been in confusing the public mind, as between the internal and the external threats of Communism. We must not confuse dissent with disloyalty. We must remember always that accusation is not proof and that conviction depends upon evidence and due process of law. We will not walk in fear, one of another. We will not be driven by fear into an age of unreason, if we dig deep in our history and our doctrine, and remember that we are not descended from fearful men — not from men who feared to write, to speak, to associate and to defend causes that were, for the moment, unpopular.”

There also was the brave and moral lawyer Joseph Welch, acting as chief counsel to the US Army after it was targeted for one of McCarthy’s inquisitions. When McCarthy smeared one of his young associates, Welch responded in full view of the TV and newsreel cameras during hearings in the Senate. “You’ve done enough,” Welch said. “Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last? Have you left no sense of decency?… If there is a God in heaven, it will do neither you nor your cause any good. I will not discuss it further.”

It was a devastating moment. Finally, McCarthy’s fellow senators — including a handful of brave Republicans — turned on him, putting an end to the reign of terror. It was 1954. A motion to censure McCarthy passed 67-22, and the junior senator from Wisconsin was finished. He soon disappeared from the front pages, and three years later was dead.

Here’s something McCarthy said that could have come straight out of the Trump playbook: “McCarthyism is Americanism with its sleeves rolled.” Sounds just like The Donald, right? Interestingly, you can draw a direct line from McCarthy to Trump — two degrees of separation. In a Venn diagram of this pair, the place where the two circles overlap, the person they share in common is a fellow named Roy Cohn.

Cohn was chief counsel to McCarthy’s Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, the same one Welch went up against. Cohn was McCarthy’s henchman, a master of dark deeds and dirty tricks. When McCarthy fell, Cohn bounced back to his hometown of New York and became a prominent Manhattan wheeler-dealer, a fixer representing real estate moguls and mob bosses — anyone with the bankroll to afford him. He worked for Trump’s father, Fred, beating back federal prosecution of the property developer, and several years later would do the same for Donald. “If you need someone to get vicious toward an opponent,” Trump told a magazine reporter in 1979, “you get Roy.” To another writer he said, “Roy was brutal but he was a very loyal guy.”

Cohn introduced Trump to his McCarthy-like methods of strong-arm manipulation and to the political sleazemeister Roger Stone, another dirty trickster and unofficial adviser to Trump who just this week suggested that Hillary Clinton aide Huma Abedin was a disloyal American who may be a spy for Saudi Arabia, a “terrorist agent.”

Cohn also introduced Trump to the man who is now his campaign chair, Paul Manafort, the political consultant and lobbyist who without a moral qualm in the world has made a fortune representing dictators — even when their interests flew in the face of human rights or official US policy.

So the ghost of Joseph McCarthy lives on in Donald Trump as he accuses President Obama of treason, slanders women, mocks people with disabilities and impugns every politician or journalist who dares call him out for the liar and bamboozler he is. The ghosts of all the past American demagogues live on in him as well, although none of them have ever been so dangerous — none have come as close to the grand prize of the White House.

Because even a pathological liar occasionally speaks the truth, Trump has given voice to many who feel they’ve gotten a raw deal from establishment politics, who see both parties as corporate pawns, who believe they have been cheated by a system that produces enormous profits from the labor of working men and women that are gobbled up by the 1 percent at the top. But again, Trump’s brand of populism comes with venomous race-baiting that spews forth the red-hot lies of a forked and wicked tongue.

We can hope for journalists with the courage and integrity of an Edward R. Murrow to challenge this would-be tyrant, to put the truth to every lie and publicly shame the devil for his outrages. We can hope for the likes of Joseph Welch, who demanded to know whether McCarthy had any sense of decency. Think of Gonzalo Curiel, the jurist Trump accused of persecuting him because of the judge’s Mexican heritage. Curiel has revealed the soulless little man behind the curtain of Trump’s alleged empire, the avaricious money-grubber who conned hard-working Americans out of their hard-won cash to attend his so-called “university.”

And we can hope there still remain in the Republican Party at least a few brave politicians who will stand up to Trump, as some did McCarthy. This might be a little harder. For every Mitt Romney and Lindsey Graham who have announced their opposition to Trump, there is a weaselly Paul Ryan, a cynical Mitch McConnell and a passel of fellow travelers up and down the ballot who claim not to like Trump and who may not wholeheartedly endorse him but will vote for him in the name of party unity.

As this headline in The Huffington Post aptly put it, “Republicans Are Twisting Themselves Into Pretzels To Defend Donald Trump.” Ten GOP senators were interviewed about Trump and his attack on Judge Curiel’s Mexican heritage. Most hemmed and hawed about their presumptive nominee. As Trump “gets to reality on things he’ll change his point of view and be, you know, more responsible.” That was Sen. Orrin Hatch of Utah. Trump’s comments were “racially toxic” but “don’t give me any pause.” That was Tim Scott of South Carolina, the only Republican African-American in the Senate. And Sen. Pat Roberts of Kansas? He said Trump’s words were “unfortunate.” Asked if he was offended, Jennifer Bendery writes, the senator “put his fingers to his lips, gestured that he was buttoning them shut, and shuffled away.”

No profiles in courage there. But why should we expect otherwise? Their acquiescence, their years of kowtowing to extremism in the appeasement of their base, have allowed Trump and his nightmarish sideshow to steal into the tent and take over the circus. Alexander Pope once said that party spirit is at best the madness of the many for the gain of a few. A kind of infection, if you will — a virus that spreads through the body politic, contaminating all. Trump and his ilk would sweep the promise of America into the dustbin of history unless they are exposed now to the disinfectant of sunlight, the cleansing torch of truth. Nothing else can save us from the dark age of unreason that would arrive with the triumph of Donald Trump.

Sexless in the city: This couple is young, crazy in love and asexual

(Credit: Aces Wild)

Levi Shaolin Back and Bauer McClave have been a couple for more than two years and are very much in love.

“We’re so cute it’s disgusting,” McClave said about her relationship with Back. The two are like any other couple — except they don’t have sex. But that doesn’t mean the two aren’t physically affectionate. They still love to cuddle and kiss.

McClave, who founded a group for asexuals called ACES, was overjoyed when she met and fell for Back, another asexual-identified person, because from the start there was no expectations for sex.

We interviewed the couple, that called sex “kinda sexy and kinda gross” to find out more about their romance. Watch.

“Rough and raw and strange”: The Felice Brothers on their new album, Dylan comparisons and making “a very modest living” at music

The Felice Brothers

There are a lot of bands playing acoustic guitars and oddball folk instruments these days, but few of them make music as consistently memorable and varied as The Felice Brothers do. Raised in the Catskill Mountains, not far from where Bob Dylan recovered from his motorcycle crash and recorded “The Basement Tapes,” the group moved to New York, where they busked in the subway and developed an urban temperament.

The band’s records have been consistently strong, and their new one, “Life in the Dark,” which Yep Roc releases next Friday, keeps the quality high: Opening with the raucous, accordion-driven “Aerosol Ball,” it includes a hooky number called “Plunder” and closes with the melancholy “Sell the House.” Somehow, the group seems perfectly at home with each style: They never seem to be faking it.

We spoke to James Felice – who handles much of the musical side of the band and plays accordion and piano – from his home near the Hudson River in Kingston, New York. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Let’s talk about the record first: Part of what strikes me is that the album is loose, a little off-balance, a little scruffy. Is that something you try for, or something you don’t try for that just happens?

I think it’s the result of the way we recorded this record, which was very quickly, with no budget, by ourselves. We were listening back to what we recorded when we first started – we weren’t sure whether we were making an album or demos; we just threw up some mics – and we loved it. We loved that it was rough and raw and strange and ragged. We knew that the songs were so good that it didn’t really matter – we could have cleaned it up and brought it to a real studio. But we thought what we were doing in that room had something to it.

You did this in a barn or something?

In a garage. Some friends of ours own a farm, and there’s a garage bay, so we did it in there.

You play the accordion, right? How do you figure out which songs want an accordion, and which songs don’t? Or does everything benefit from an accordion?

Either everything benefits, or everything loses out when the accordion’s on. Some of it was out of necessity: I was recording the band the same time we were playing live, and sometimes I had a piano that was farther from the computer than I needed to be when I needed to hit play and stuff. So I played the accordion instead.

Huh – deep musical reasoning loses to convenience.

Yeah.

The band is known as being rustic and folky, but I think punk rock has been an inspiration as well. Was that an inspiration at the beginning, or did it show up later? Does it still matter to you guys?

I think so – I think from the beginning we saw ourselves, at least at the beginning, as more punk than folk. Punk rock with more acoustic instruments. But we grew up listening to a lot of folk music – I listened to more folk growing up.

I don’t know what our aesthetic was. We didn’t know what we were doing, and we didn’t care. We just wanted to play music no matter what. So that’s what we did. I think that’s punk in a way, for sure.

From the beginning – and it’s true again of the new record – you’ve been compared to The Band and Dylan’s “Basement Tapes.” I know it drove you crazy for a while – does it still?

I think we’re over it! It must be true if it’s been 10 years and people are still saying it. I remember when we made our first record, and were compared to The Band, I had never even heard The Band’s records! So I was surprised. But then we started listening to The Band’s records and said, “Yeah, these guys do sound a lot like us!”

I mean, I still haven’t listened to “The Basement Tapes” all the way through. I just never got around to it. But I love The Band, I love those musicians – they recorded music in the same place where we grew up. I have a lot of respect for those guys.

So it doesn’t drive me crazy anymore. I think for a while it did. No one wants to be compared to anything. Everyone wants to think they’re the first person to do anything. But you realize after a while that that’s just not the case.

Do you feel like you’re part of a larger movement of roots bands that includes Dave Rawlings and Gillian Welch, and Dawes, and other acoustic acts? Or do you feel like you’re off on your own?

I feel like we’re off on our own; because we live out in the middle of nowhere, we don’t interact too much with anyone else. We’ve played shows with Dawes and Rawlings and all those guys, here and there. But we live in upstate New York – we’re pretty isolated. On a musical level, I guess we’re all cut from the same cloth, one way or the other.

I know at least some of the guys in the band are interested in American history. Does the recent political craziness remind you of any other historical eras? Does it interest you?

It’s definitely interested me – I’ve become fully entranced by the whole thing. Since right before the primaries started, I became really interested in politics. Who’s that crazy populist lunatic from Louisiana – Huey Long? I’ve read about him.

You can look at Donald Trump and see all kinds of terrible reflections in him, or the worst part of our past and of Europe’s past.

Does the extremism in the race seem funny to you, or scary, or some mix of both?

At first it was funny – I was very entertained by the entire Republican primary race. It was hilarious. Trump was the worst of them by far – and when he won, it was funny for a minute. But now it’s definitely becoming concerning. And I become infuriated when I hear him speak… It hurts my head. I was just thinking about this this morning – it makes me mad to think about him.

He does have a funny delivery, doesn’t he? He speaks in a few words at a time, repeats the same few words – “It’s gonna be beautiful! Wonderful! Great!”

His vocabulary is minuscule, what he says is idiotic… I know more about history than he does – and I don’t know that much. It drives me bonkers. The elevated language of an Obama is such an interesting thing. I have a lot of respect for educated people: I’m not really one, I never really went to college. But I love reading well-written political thought. I love reading Teddy Roosevelt, his speeches, Lincoln, all those guys.

To actually read what Trump says – it’s mind boggling, it’s childish and inane the way he comes across… I don’t like the guy, I gotta say.

Let’s close with music. Some musicians this week have complained about YouTube and streaming. Your band goes back about a decade, so you started recording post-Napster, in a period where record stores were disappearing and album sales falling off. What kind of impact has the Web had on you? Do you ever wish you’d been in a band in an earlier era?

I do sometimes wish that people bought our records. It was a more lucrative profession to be in.

I don’t know if we would be a band if there was no such thing as the Internet, because we basically needed it to get started – to spread the word. I remember when we had MySpace. We’d spend hours – we would sneak into this computer lab at the college we lived next to, and we would friend people on MySpace, or like them, or something, for the Felice Brothers page. We’d go to Ryan Adams’ page, and like-minded artists’, for hours: We got a lot of fans that way. And booking shows, communicating with other people, and getting our music out there was because of the Internet.

But we don’t really make any money selling music. There’s five adult men in the band, and we make a very modest living. We still make a living, which is awesome, but we don’t make any money from selling CDs – we make all of our money from touring, and the occasional getting a song on a TV show sorta thing.

So the Internet helped you establish yourself, but made it harder, in some ways, to keep going.

I think it’s allowed a lot more bands to get out there, but not quite as many seem to be thriving. It’s nice to imagine being in the ’70s again.

“How to Make White People Laugh”: Comedian and author Negin Farsad on fighting Islamophobia, one “bacon test” at a time

Negin Farsad (Credit: Ryan Lash)

New York City-based comedian, writer and director Negin Farsad’s debut nonfiction book, “How to Make White People Laugh” (Hachette Book Group, 2016), is best described as memoir meets social-justice-comedy-manifesto.

A former TEDFellow, director and star of the popular documentary “The Muslims are Coming!” and the upcoming film “3rd Street Blackout,” Farsad has dedicated her career to the idea that making people laugh will, eventually, lead to a cultural shift.

Her illuminating memoir offers a frank and hilarious conversation about growing up as an Iranian-American Muslim woman in a post-9/11 world, as well as what it means to have a hyphenated identity. It’s at once a comedy and a reflection on the power of comedy to initiate social change — with plenty of research, graphs, images, and footnotes to back it up. Salon spoke with Farsad about her career as a social justice comedian, and what inspired her debut.

How did you get into social justice comedy?

After I went to graduate school for African-American studies and Public Policy, I got a job as a public policy analyst for the City of New York. I always wanted to work as a public servant and figure out ways to do right by the world. For me, being a comedian felt really selfish because it didn’t seem to fit into the realm of “giving back.” When I left to do comedy full-time I thought about how I could use it as a platform to advance social justice issues.

“How to Make White People Laugh” is filled with ideas about identity, social justice theory, and humor, based on your career as a comedian and filmmaker. What inspired you to write the book?

It’s funny, because I’ve made four feature films, and I’ve done a bunch of TV writing and stand-up, and I’ve never felt constricted by the format of genre or medium. I think what’s interesting about writing a book is that you can say anything you want. That’s not even the case with stand-up, where you have to be very concise and there are certain rules you have to follow, like a particular number of jokes per minute. In a book, the format is so flexible, it’s really exciting, which is one of the reasons I wanted to be able to do this project in the first place.

In your book, you talk about growing up identifying with the struggle, but not yet relating it with your own identity, and as a result latching onto the dominant minority group around you. When did you really start identifying yourself as Iranian-American Muslim?

I always did, but in terms of where I was putting my energy I was like oh no, I fight for the black struggle; that’s what I do. I went to grad school in the aftermath of 9/11, and at a certain point I remember feeling that the mood in the country was becoming very anti-Muslim. I saw things going awry and people talking about Muslims in a weird way, and there was the War on Terror and the Axis of Evil, and that’s when I started feeling like, I can also fight for this other struggle, and that I have a legitimate voice in that, too.

But even before that, my parents came to the U.S. during the Iranian hostage crisis, and it was already very anti-Iran, so they went through a lot of that stuff. I was a baby at the time and grew up with this story, so I always felt like my parents came into an unwelcoming situation.

So it was a matter of connecting the dots between your identity and larger social justice causes?

Yeah, and also realizing that this deep desire for fighting for African-American rights is just another side of the coin of fighting against Anti-Muslim rhetoric.

You open your book by joking, “Like most comedians, I have a masters degree in African American studies.” But more seriously, how would you say the academic training and education has contributed to your work as a comedian?

It’s not like you need to have a Masters in Public Administration or African-American studies to be a comedian, but I don’t regret doing any of the schooling. I think more broadly speaking, I do use it, and it helps me approach issues more critically. I feel like every time I sue the MTA, for example, I’m utilizing an aspect of this training.

Last year I did a Bacon Test with MoveOn.org where I asked people if they were Muslim, and if they said no, I would say, “Prove it!” and they’d have to eat from a pile of bacon. If they wouldn’t, I had them sign a Muslim registry. It was basically in response to Trump’s proposed policies of the ban on Muslims. I thought, OK, if you want to put Muslims on a registry we’re going to need some kind of religious test, and this project was the logical extension of that policy proposal. We don’t even have enough money in the budget for the kind of bacon we’re talking about.

So in response to the question, having this background and approach lets me take issues like these and really think about how they would be implemented as a policy, comedically.

Many people talk about how comedy can be an effective tool for breaking down stereotypes, and you’ve talked about how this fuels your work. After working as a comedian for about a decade, and touring all over the U.S., how do you think comedy can initiate social change?

When I was doing the MTA poster, people would ask me all the time, “Do you really think a poster is going to change people’s attitudes?” and I would be like, “No, I don’t.” The way I see it is, someone sees a poster and they have a chuckle and then someone else sees it and has another chuckle, and if you add up all of these moments, and I’m talking in the millions, that’s when you start seeing a cultural shift.

So I’m not changing anybody this one time with this one encounter, but over a period of time, if enough people are doing this kind of work, with multiple encounters and multiple engagements, I think all of these things will add up to social change. And I really do think people can change, which is why I have a section in the book on the “Reform Haters.” They’re a really interesting category; these are people who were so identified with their position and then eventually came to disavow it. That’s amazing. Human beings have the capacity to do that.

Words matter: Trump’s taking a dangerous path with his demonization of Muslims and other groups

Donald Trump (Credit: AP/Chuck Burton)

Shortly after last weekend’s tragic mass shooting at the Pulse dance club in Orlando by a homophobic Islamic terrorist, Donald Trump, the presumptive GOP nominee, quickly doubled down on rhetoric that had prompted numerous commentators to call the billionaire demagogue a fascist earlier this year. Even though the terrorist, Omar Mateen, was an American citizen born in New York, Trump once again called for a ban on Muslims entering the country, while fear-mongering about refugees and the screening process in a rambling speech full of blatant and egregious lies.

As I noted on Tuesday, Trump’s irrational and impulsive response to the shooting will only help the Islamic extremists who practice a form of theocratic fascism themselves — by alienating the world’s 1.6 billion Muslims, the majority of whom strongly reject violence and terrorism. Like the Islamic State, Trump accepts and promotes the “clash of civilizations” narrative, and he is playing right into the terrorist organization’s hands.

Trump (and Republicans) seem determined to learn absolutely nothing from the latest attack, not least the need for common sense gun control measures that would help prevent someone like Omar Mateen from buying guns — particularly assault weapons that serve only one purpose: to kill.

Instead, Trump is peddling the same asinine policies that he has been touting over the past year; policies that have a strong emotional appeal, but are widely rejected as absurd and foolish by most experts. Throughout his campaign, Trump has frequently submitted plans that were obviously thought up on the spur-of-the-moment, usually in response to a major news event. The most notorious knee-jerk policy was his aforementioned Muslims ban, which the billionaire thought up shortly after the San Bernardino shooting. After slightly backtracking on this plan last month and claiming it was just a “suggestion,” the billionaire is now aggressively promoting it again and congratulating himself after Orlando.

Trump’s impulsive need to put forward a major plan of action whenever something happens in the news, without any due consideration for whether the policy is legal or constitutional or even practical (indeed, Trump seems unable to consider whether one of his brilliant ideas would actually exacerbate problems) brings to mind what the late novelist and professor Umberto Eco called the “cult of action for action’s sake” in his 1995 essay “Ur-Fascism.”

In this frenzied mindset, critical “thinking is a form of emasculation,” while action is “beautiful in itself,” and “must be taken before, or without, any previous reflection.” Naturally, “distrust of the intellectual world has always been a symptom of Ur-Fascism.”

In the same essay, Eco goes on to list various properties (14 in total) of Ur-Fascism (or “Eternal Fascism”), many of which correspond with the Trump campaign and the “alt-right” movement that has formed around it. While Eco notes that different fascist movements do not share every feature, they do share a “family resemblance,” a concept first popularized by Ludwig Wittgenstein. The novelist defines eternal fascism as a “fuzzy totalitarianism, a collage of different philosophical and political ideas, a beehive of contradictions” (it is almost as if he were describing Trump’s politics).

The most apparent themes of the Trump campaign have been nationalism, xenophobia, the scapegoating of religious minorities (i.e. Muslims), the rejection of diversity, and the anti-intellectual backlash against the “politically correct” liberal elite, which tends to mean experts (e.g. climate scientists), professionals, and academics. Above all, any kind of cultural differences or political disagreements are seen as treasonous or “un-American,” which arises from what Eco calls the “fear of difference.”

“In modern culture the scientific community praises disagreement as a way to improve knowledge. For Ur-Fascism, disagreement is treason,” he writes. “Besides, disagreement is a sign of diversity. Ur-Fascism grows up and seeks for consensus by exploiting and exacerbating the natural fear of difference. The first appeal of a fascist or prematurely fascist movement is an appeal against the intruders. Thus Ur-Fascism is racist by definition.”

The intruders and enemies are everywhere in Trump’s paranoid worldview. The “criminal” and “rapist” Mexicans are stealing American jobs, the world’s 1.6 billion Muslims are resolute on killing Americans and infidels, the foreigners (e.g. Chinese) are laughing at us and ripping us off in trade deals. In the Trumpian perspective, every single problem that America faces can be explained by some insidious outsiders who are determined to humiliate America’s proud heritage and history of “winning.” Which leads us to another feature of Ur-Fascism: social frustration.

“One of the most typical features of the historical fascism was the appeal to a frustrated middle class, a class suffering from an economic crisis or feelings of political humiliation, and frightened by the pressure of lower social groups.”

Sadly, many members of the white working (and middle) class have been particularly susceptible to Trump’s demagoguery, especially if they are straight males (according to a recent Bloomberg poll, a whopping 63 percent of women say they could never vote for Trump). While it’s true that a great deal of these people have been negatively impacted by globalization, and have valid grievances when it comes to trade deals like NAFTA and the TPP, the Trumpist rage seems to be motivated more by accelerating equality for women, people of color, and the LGBT community, as well as the diminishing privilege that white males have long had in society.

Finally, the Trump movement is united by national identity (of course, national identity does not mean all Americans, but those who Sarah Palin refers to as “real Americans” — after all, Omar Mateen was an American citizen). According to Eco, national identity is reinforced by a nations real or imagined enemies:

“The only ones who can provide an identity to the nation are its enemies. Thus at the root of the Ur-Fascist psychology there is the obsession with a plot, possibly an international one. The followers must feel besieged. The easiest way to solve the plot is the appeal to xenophobia. But the plot must also come from the inside: Jews are usually the best target because they have the advantage of being at the same time inside and outside.”

For Donald and his legions, it is the Muslims, Mexicans and Chinese who are cunningly plotting against us on a global scale.

Fascism is ultimately more of a pathology than an ideology, engendered by destructive passions, fueled by resentment, bitterness and fear. The Trump movement has revitalized a dormant impulse in American politics, one that is as prone to paranoia as it is to violence and bigotry. And while it seems unlikely that Trump will win in November, the neo-fascist movement that he has breathed new life into is just as unlikely to go away after 2016.

Obama, the funniest president: Laughter isn’t just the best defense—it’s a powerful image strategy, too

Barack Obama on "The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon" (Credit: NBC)

Now that President Obama’s departure from the White House is in sight, it is time for an appreciation of one under-reported aspect of his character that I suspect we will all miss no matter who is president this time next year. (It’s going to be Hillary Clinton.)

Obama is really damn funny.

I don’t mean he’s funny in that he is a ridiculous or easily caricatured figure. He may be the first president of my lifetime who comedians have never been able to draw a bead on the way they could with every other Oval Office occupant of the last 50 years. Phil Hartman’s renditions of Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton are still hilarious a good 30 and 25 years later, respectively. Dana Carvey’s take on George H.W. Bush still feels dead-on. Even Will Ferrell’s lazy interpretation of George W. Bush works because the president himself came off as being lazy and disinterested for his entire eight years in office.

No, Obama is a genuinely funny performer who has gotten better over the course of his presidency. Watch some of his speeches at the annual White House Correspondents Dinner and compare, say, 2009 to 2016. Or watch this great spoof in which he plays Daniel Day-Lewis playing Barack Obama. He’s got excellent timing and a relaxed bearing. He makes the smart choice to play the absurd premise straight up. As far as Steven Spielberg comedies go, it’s a hell of a lot funnier than “1941.”

Like many performers, it helps to hand Obama a decent script. But he’s good even when you don’t. The jokes in his WHCD speeches are often hacky and obvious, but he still sells them. The infamous Buzzfeed selfie-stick video from early in 2015 doesn’t have much of a script, but the president somehow finds some humor in it.

Or stick him with an inferior co-star like John Boehner or Jimmy Fallon. Yes, Jimmy Fallon is actually less funny and entertaining than the president when the latter has appeared on “The Tonight Show” to slow-jam the news. Maybe NBC should give Obama the show after his term ends. He might need something to do, at least until he and Michelle move back to Chicago in a couple of years and he joins a touring troupe at Second City.

Granted, your appreciation of Obama’s humor likely depends on your political leanings. I doubt, for example, that Orly Taitz ever laughed at any of the birther jokes with which he has peppered his annual routines at the WHCD, or that featured as the culmination of this bit he taped for a televised celebration of Betty White’s 90th birthday. It’s tough for people to laugh at themselves, particularly if it gets in the way of self-righteous zealotry.

Part of the reason Obama has become our funniest comedic performer president is opportunity, of course. His time in office coincided with an explosion in online video and TV, and his administration more than any other has eschewed traditional media to help him get his message out. For example, his appearance on “Between Two Ferns” with comedian Zach Galifianakis was intended to inform people about the launch of healthcare.gov. But it’s true that he is also a relaxed performer in a way that George W. Bush, who also had some similar outlets available to him during the last decade, never was. If you doubt that, here is Bush at the 2007 WHCD dinner, reading a joke-filled speech with all the aplomb of a little kid forced to put on a suit and spend Sunday in church.

This being politics, there is probably something in the content of Obama’s performance reel that is offensive or cringe-worthy for everyone. Opponents of drone warfare might wince, as I did, re-watching his 2010 WHCD speech when he joked about sending a Predator drone after the Jonas brothers if they so much as looked at his daughters. I’m sure a lot of people got angry at the end of the 2014 WHCD speech, months after the difficult rollout of healthcare.gov, when Kathleen Sebelius walked out onstage and pretended to help the president fix a balky video of himself. “That’s not funny! People suffered,” I imagine wingnuts yelling at the screen as they watch it.

Some of this criticism is sour grapes, the long-standing right-wing belief that in Obama, those damn Democrats elected a man who cares more about preening for the camera than governing. (This line of thought is particularly ironic, considering the current Republican presidential nominee.) But – and it pains me to admit that conservatives are even in the same zip code as a smart idea – there is a kernel of truth here, not about Obama specifically but about what we demand of our presidents when they stand before us in all their guises.

In the modern presidency, image is king. Administrations obsess over approval ratings, particularly when re-election is coming up. Projecting likability, that vaporous and subjective quality, becomes more important than anything. We ask that presidents comfort us with their seriousness, inspire us with bravery, and entertain us with their jokes. We demand that they be humans and superheroes all at the same time. We put them in positions where the only choices are awful and then complain when they pick one.

Laughter is the great agent of disarmament of criticism. Yet I’ll still miss Obama’s performances when he’s gone. He was better at it than anyone else we’re likely to see.

Sex by the numbers: This is how many partners men and women average in a lifetime

(Credit: oleg66 via iStock/Salon)

Sex is a sticky enough subject as is. But complicating matters is the idea that, in general, we need to partner up to get the deed done. There are those who stick to one lover and there are others who opt for more. Unfortunately, some see sex as a numbers game, and a high score doesn’t always get you a winning ticket.

According to a survey of more than 2,000 people in the U.S. and Europe, men believe women who have had 14 partners or more are “too promiscuous.” Women thought the same of men who have had 15 partners or more.

The survey, conducted by SuperDrug Online Doctor, found men to be more likely than female participants to inflate the number of sexual partners they’ve had. Women, on the other hand, were more likely to deflate the number of partner’s they’ve bedded. The majority of both genders (67.4 percent of women and 58.6 percent of men) claim they’ve never lied about the number of people they’ve slept with. Whether or not that’s a lie is up to you to decide.

On the other side of the spectrum, men believe 2.3 partners is too conservative, while women think 1.9 is the threshold for too few.

According to the guys surveyed, the “ideal” number of partners for women is an average of 7.6. Women answered similarly, citing 7.5 partners to be a good number to cap it at. Interestingly enough, women reported having had more sexual partners overall than men, with an average of 7 to date. The men surveyed averaged about 6.4 partners.

Other interesting findings are listed below:

31.2 percent of female participants feel it is appropriate to share details about sexual history within the first month of meeting a potential partner. 33.8 percent of men feel the same.

People from the U.K. lead the way with the most partners, averaging seven sexual partners. Respondents from Italy averaged only 5.4 sexual partners

People in first-place Louisiana averaged nearly six times as many sexual partners as residents of bottom state Utah: 15.7 compared with 2.6

Over half of respondents said they would be very unlikely to walk away due to a partner’s conservative past, and another 15 percent said they would be somewhat unlikely. Only 8 percent reported they would be somewhat or very likely to end a relationship due to this issue

Of people with 15 or more sexual partners, 13 percent reported having ever been diagnosed with an STI—the highest proportion.

The survey does reconfirm findings in previous research, which suggests that millennials are actually having less sex than the generations that came before them. Gen X-ers bed an average of 10 people throughout their lifetimes, while the baby boomers are believed to have had up to 11 partners.