Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 742

June 21, 2016

The damage has been done: As Trump barrels toward defeat, he’s dragging the GOP to the extreme right on race

Donald Trump (Credit: Reuters/Nancy Wiechec)

Barring some kind of miraculous turnaround, it appears that the Donald Trump campaign is not just a failure, but a bona fide catastrophe.

New FEC filings show that Hillary Clinton has over 30 times as much money as he does, a situation that is unlikely to change, as reports suggest Trump is unwilling to do the boring work of fundraising. The campaign fired Corey Lewandowski as campaign manager, the kind of high profile panic reaction that tends to dissuade would-be donors even more. His campaign has a staff of 70 people, compared to the 700 currently in Clinton’s employ.

The Trump campaign is, as Jonathan Chait likes to call it, a garbage fire. More than that, there’s indications that, like most Trump endeavors before it, it’s a scam. Trump’s M.O., as reporting on everything from Trump University to his casino investments shows, is to dazzle gullible people into giving him money with a bunch of lies, and then to take the money and run, leaving his victims holding the bag.

The same philosophy seems to be underpinning the Trump campaign. He has repeatedly told flat-out lies in order to trick would-be donors into thinking his campaign is healthy, such as claiming on May 29th that “my campaign has perhaps more cash than any campaign in the history of politics” and, even after the FEC report came out, swearing on Fox News that “I have a lot of cash.” And, no surprise, he’s redirected at least $6 million back to his own companies,

But even though Trump’s campaign lands somewhere between a disaster and a grift, there is every reason to continue to worried about the dangers of the Trump campaign. No, not because he’s going to win — that’s increasingly hard to imagine, as he’s well behind Clinton and has no real resources to catch up — but because he’s laying down groundwork for future Republicans, who might be a lot more successful at using his campaign of white nationalist grievance.

We’ve seen this sort of thing before. In 1964, Barry Goldwater ran a campaign harnessing white grievance at desegregation. The campaign was famously a disaster, garnering less than 40 percent of the vote and only 52 electoral college votes. The obvious conclusion to make, at the time, would have been that racial resentment is a bad campaign strategy, something better left to the dustbin of history for Republicans who want to win future campaigns.

But what happened was that, instead of dumping the racial resentment angle, Republicans decided to go about it a different way. The plan was to keep the racism, but swaddle it in a thicker coat of plausible deniability. In 1968, what that meant, for Richard Nixon, was dropping more overt defenses of legal segregation and turning instead to more coded appeals to racism.

As Lee Atwater famously noted in a 1981 interview with political scientist Alexander Lamis:

You start out in 1954 by saying, “Nigger, nigger, nigger.” By 1968 you can’t say “nigger”—that hurts you, backfires. So you say stuff like, uh, forced busing, states’ rights, and all that stuff, and you’re getting so abstract. Now, you’re talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you’re talking about are totally economic things and a byproduct of them is, blacks get hurt worse than whites.… “We want to cut this,” is much more abstract than even the busing thing, uh, and a hell of a lot more abstract than “Nigger, nigger.”

Which is, of course, an apt description of how the Republican party went about things. Coding the racism in this way made it more socially palatable. Nixon’s “law and order” campaign played on white fears of black violence, all without saying so directly and he was able to win in a landslide, even with George Wallace playing the spoiler and sucking votes away on the right. Ronald Reagan built on that strategy, using rhetoric about “welfare queens” and “states rights” to signal racial attitudes, all without being too overt about it.

There’s no reason to think that this kind of thing can’t happen in some form again. Yes, Trump will lose in November. But the fact that he got this far in the first place, beating out seasoned politicians in a primary, will matter. Trump managed to get the Republican presidential nomination with an incompetent staff, no real fundraising prowess, and a candidate who is so narcissistic that it makes other politicians look like the humble servants they always claim to be.

He did it with one simple trick: Being racist as all get-out, which clearly wins big with the Republican base. Other Republicans, watching this go down, may very well be wondering how far you could get if you took Trump’s message, cleaned it up a bit, and put real organizational power behind it, instead of motley crew of hangers-on and your own children.

After all, that’s exactly what Nixon and Reagan did: Take the more overt racism fueling the Goldwater campaign, pretty up the rhetoric a bit, and win big.

There’s already indications that even as he’s going to lose, Trump’s rampage is tugging the Republicans rightward on the racism issue. Paul Ryan called Trump’s rhetoric “textbook” racism, but then continued to support Trump anyway. Overt racism used to be a deal breaker, but no more, I guess.

You see this process with the Republican obsession with magic words, too. Sure, Republicans were accusing President Obama of being afraid to say “radical Islam” before Trump, but he took it to the next level, implying that it’s because Obama is working for ISIS.

Now, most Republicans won’t go there, but Trump has opened a door. Now the accusations that Obama is somehow concealing something by not using magic words have grown more serious, with Paul Ryan openly accusing Obama of trying to “downplay and distract from the threat of radical Islamist extremism.” It’s the same accusation as Trump’s, that Obama is, for some dark reason, trying to hide the truth of the world. It’s just prettied up a little more, to sound a little less like a conspiracy theory, and therefore this talking point has more mainstream traction.

Now, there’s good reason to believe that this strategy may not work as well as it did in the past. The country is more racially diverse than it used to be. About 40% of white people voted for Obama, and if those voters were open to voting for a black president, odds are most won’t be interested in racist appeals, even if they are more coded than what Trump is offering.

But the fact remains that the Republican voting base sent a strong message to the party: They love racist appeals so much that they are willing to overlook the fact that they are coming from an orange-hued clown that is too lazy to do even the bare minimum to run a presidential campaign. The party will probably hear that and try to find a way to meet the base’s desires, but in a way that’s more elegant and professional than what Donald Trump is offering.

This one common childhood experience can traumatize you well into adulthood

In 2014, according to a United States national census, more than 11% of Americans relocated across state borders. In our mobile society, this might seem like par for the course—no cause for alarm. But what about the effects such internal migration has on children later in life? Washington Post writer Christopher Ingraham recently asked this very question. His conclusion: In the long run, it’s bad for the kids.

For the article, Ingraham drew on the findings of a recent study published by the American Journal of Preventive Medicine that addressed the effects of moving one’s family around. In the study, a team of researchers conducted a comprehensive analysis using information gathered from everyone in Denmark born between 1971-1997 (which is only marginally less impressive when you consider that the country is around a third the size of New York state.) The team looked at the ratio rates of “attempted suicide, violent criminality, psychiatric illness, substance misuse, and natural and unnatural deaths” within this data set.

Their conclusion? Based on the “uniquely complete and accurate registration of all residential changes in [Denmark’s] population,” the team found that moving during childhood was directly tied to an increase in all of these measured negative outcomes later in life. And repeated moves in the course of a year — even worse. The team further found that children are most vulnerable at ages 12-14, with those who moved at 14 experiencing double the risk of suicide by middle age.

As Ingraham duly noted, however, while the study took into account parents’ income and psychiatric history as a control, the data was unable to provide information on the reasoning behind the moves. Ingraham illustrated this flaw by pointing to previous research conducted in the United States, which shows that beyond the act of moving itself, environment plays a far greater role in childhood development and its implications for adulthood. In other words, the positive effects of moving during childhood to a less violent neighborhood far outweigh any negative consequences. Of course, this oversight could also be attributed to Denmark having a generally lower rate of violent crime.

One of the study’s findings likely to carry more weight locally in the U.S. and abroad concerns the effects of changing schools. For these purposes, the study only considered moves across municipal boundaries, which meant a change in the child’s school district. Here the authors concluded:

“Relocated adolescents often face a double stress of adapting to an alien environment, a new school, and building new friendships and social networks, while simultaneously coping with the fundamental biological and developmental transitions that their peers also experience.”

Overall the results of the research are pretty damning. How much they directly apply contextually to other countries such as the United States is less clear. The study’s authors conceded that “the findings may not apply universally beyond Denmark, although it seems likely that they are relevant to other western societies with similar drivers of residential mobility.”

It seems pretty logical that changing one’s living environment during the onset of puberty could have lasting psychological consequences, and families that need to do so should take into account the hardship it presents to their growing children. Any direct link to higher risks of other negative consequences later on in life may be harder to establish.

(If these findings do hold true for the United States, we could be looking at a pretty depressing sequel to Inside Out.)

June 20, 2016

“Orange Is the New Black” could help save trans inmate lives: Prisons continue to fail women like Sophia

Laverne Cox in "Orange Is the New Black" (Credit: Netflix)

“Ever seen me look this ravishing?” Sophia asks. Nicky, her former prison mate, responds with her trademark sarcasm, but even she can’t mask her shock at the horror she’s witnessing. “If we’re using ‘ravishing’ as a synonym for ‘horrendous,’ never,” Nicky says.

This scene is a standout moment from Netflix’s “Orange Is the New Black,” Jenji Kohan’s prison dramedy whose fourth season dropped on the streaming platform Friday. The acclaimed show takes a darker turn in the fourth season, detailing the everyday injustice of the prison system. After Litchfield becomes a for-profit institution, the prison becomes punishingly overcrowded; if you don’t get to the cafeteria early, you don’t get to eat breakfast or lunch at all. New inmates, unable to get work assignments, have no resources to buy tampons from commissary. They are, thus, forced to get creative about their hygiene needs.

Sophia Burset (Laverne Cox) is the face of that structural inhumanity. Played by Emmy nominee Laverne Cox, Sophia has been thrown into the Solitary Housing Unit (or “SHU”), allegedly “for her own protection.” As the only transgender inmate in Litchfield, she was the target of harassment and violence from other prisoners in the show’s previous season; this year, Sophia finds little comfort in solitary. The fluorescent light is kept on 24 hours a day, and she isn’t even given a blanket to keep warm. When Nicky finds her, Sophia claims she hasn’t slept in days.

Sophia’s powerful storyline is indicative of the grave abuses that transgender inmates face when housed in correctional facilities, whether it’s in the United States or abroad. Trans women, in particular, are frequently denied access to hormone therapy, gender reassignment surgery, or affirming health care. In addition, these inmates are often housed in men’s prisons, where they are likely to be abused or sexually assaulted. Many prisoners like Sophia will be isolated in solitary confinement for weeks, years, and sometimes even decades, which both increases the risk of serious psychological damage—and even suicide.

For trans people, the current state of mass incarceration amounts to cruel and unusual punishment. While things are slowly improving, transgender inmates remain locked away and ignored in a system that often refuses to recognize that they are human—let alone affirm their gender identity.

In 2016, the Department of Justice issued a groundbreaking memorandum stating its official policy that transgender inmates cannot be assigned to prisons based on their anatomy alone.

“The [Prison Rape Elimination Act] standards require that housing decisions for transgender prisoners be made on a case-by-case basis,” the National Center for Transgender Equality explained in a press release. “The new guidance makes clear that housing transgender people based solely on sexual anatomy is not ‘case by case.’ Instead, detention facilities must seriously consider all factors relevant to keeping a person safe, including their gender identity, the gender they live as, and their own view of where they would be safest.”

Prior to the DOJ decision, many states, including in Colorado and Pennsylvania, outright denied gender-affirming housing for trans inmates, while others—like Massachusetts—made subjective decisions based on the prisoner’s “biological gender presentation and appearance.” When the department’s guidelines were released, Harper Jean Tobin of the NCTE told Vocativ that the improper assignment of trans inmates is a “universal” problem with the U.S. Department of Corrections, one that extends to every state in the nation. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, there are around 3,200 trans people behind bars in the U.S.

But unfortunately, the DOJ guidelines are just that—guidelines. Detention centers can choose not to follow them. That’s a huge problem in a system rampant with routine human rights abuses, particularly against populations already vulnerable to harm.

In 2007, a study from the University of California Irvine found that 59 percent of transgender women are sexually assaulted while in prison, whereas just 4 percent among the general population report being raped by guards or other prisoners. The rate of trans sexual assaults is, thus, an astounding 14.75 times higher, and in many cases, these incidents occur with shocking regularity.

A trans inmate in the United Kingdom reported being raped “more than 2,000 times,” and in the U.S., Ashley Diamond sued the Georgia Department of Corrections, detailing years of “torture” in a men’s prison. As the New York Times reports, Diamond was raped seven times, mocked because of her gender identity, and frequently sent to the SHU for the crime of “pretending to be a woman.” Correctional officers repeatedly referred to her as a “he-she thing.” According to Diamond’s suit, she frequently tried to take her own life, even attempting to castrate herself.

Cases like these are extremely common in the prison system. A particularly egregious example is Passion Star, a trans inmate who was repeatedly harassed by guards, instructed to “suck dick” and “stop acting gay.” When Star was threatened by a gang member, she requested transfer to another cell to be kept safe from harm. Instead, officials did the opposite—moving her closer to her harasser.

In addition to being misgendered by officials and taunted by other prisoners, trans inmates are frequently denied hormone therapy, which can have extremely damaging effects on inmates’ health.

A 2014 survey from Black & Pink found that 44 percent of trans people in U.S. correctional facility are denied hormones, even if they were undergoing replacement therapy before being incarcerated. For those who are prescribed hormones, getting gender-affirming care can be a long, painful application process that can take months or years—in which trans people have to be sent to a series of specialists to diagnose them with gender dysphoria. Some of those physicians will even deny them treatment, as the Houston Press reports. When a transgender woman disclosed to a physician in Texas that she was bisexual, he turned her down—following a series of bizarre questions, like whether she had sex with children.

“For transgender men and women who rely on hormone therapy for both their mental and their physical health, this deprivation can have some serious consequences,” the Houston Press writes. This can include suicide attempts and other acts of self-harm. To fix those issues, they will either be given depression medication, thrown into a psych ward, or locked in solitary.

When solitary was originally instituted in prisons in the 1820s, it was seen as beneficial for inmates, even therapeutic. Correctional officers and wardens, as io9 reports, imagined that “prisoners would spend their entire day alone, mostly within the confines of their cells, ruminating about their crimes while distanced from negative external influences.” Solitary confinement was, thus, seen as a kind of zen center for those who pose a particularly high risk for violent behavior.

In truth, that’s not how solitary operates. As “Orange Is the New Black” points out, Solitary Housing Units are akin to hell on earth—where inmates are denied contact with other people, sleep, material comfort, or almost any form of entertainment. Some inmates may be allowed to have light reading material (Nicky gives Sophia a magazine to peruse), but a television? Forget about it.

The American Psychological Association notes that it’s being used with increasing frequency in recent years, and the sentences are getting longer. A 2013 report from Wired noted that the average inmate is held in solitary confinement for five years, and many of these inmates will be like Sophia, held to keep them out of harm’s way. (The practice is known as “administrative segregation.”) But over a period of years, that isolation and monotony can lead to “anxiety, panic, insomnia, paranoia, aggression and depression,” according to the APA. Many prisoners report having auditory and visual hallucinations or developing severe mental trauma.

The fact is that trans women—more than any other population—remain disproportionately likely to be subjected to these kinds of “preventative measures,” simply because they remain burdened by the gravest miscarriages of justice in the American penal system. Prison officials have no idea what to do with them, and rather than simply listening to what they need, it’s easier to ignore them and shut them away.

Although states like California and Texas have taken steps to amend these issues by providing surgery and hormones, respectively, to those who need them, too many localities lag far behind when it comes to providing the sweeping reforms trans people need.

What Sophia Burset is facing might be unimaginable, but for too many inmates, it’s not. It’s what thousand of trans people have to deal with every single day.

LeBron James, hometown hero: What the King and his championship mean to Cleveland

LeBron James answers questions as he holds his daughter Zhuri during a post-game press conference, June 19, 2016, in Oakland. (Credit: AP/Eric Risberg)

LeBron Raymone James stands six feet, 7.25 inches tall in bare feet, 6’8” when he’s wearing one of the 41 varieties of his signature kicks. He can make a vertical leap over the average six-year-old. He owns enough cars for his collection to be pronounced a “fleet.” He has an estimated net worth of $300 million. He can dunk a basketball with authority. In short, he and I have nothing in common.

The NBA is full of people who are nothing like the rest of us. And from the perspective of a business trying to secure a reverent fan base, that’s convenient. NBA players’ inherent dissimilarity from the world of five-figure-earning, normally sized folks makes it easier for us to raise them up and behold them as icons. The truly brilliant thing is how the NBA toes the line between embracing this notion and rejecting it, keeping its players distant enough for us to worship them and yet close enough for us to feel attached to them. There’s a cult of familiarity around these guys, which is perhaps why I find myself referring to LeBron as “LeBron” and not “James.” This is the appeal of the NBA: if I can wear his same shoes, maybe I can be raised up too.

Of course, this in itself reiterates how fundamentally distant from us these players are. Even as we feel drawn to our hometown heroes, we know, on some level, that this closeness is ultimately a fantasy. After all, we don’t regard the true, actual people in our lives as gods, as kings. But, for a moment, let’s choose not to care.

***

If you are a sports fan from Cleveland, there are a number of times when you have to suspend disbelief. When it’s been 52 years since any of your professional teams have won a championship, even attending a game is a repudiation of a certain reality. I grew up hearing about The Move, The Drive, The Fumble, The Shot. And I grew up fervently believing that those days were behind us, a part of our inherited history as a city, but merely our history, not our DNA.

And so the morning of July 8, 2010, I rose free of dread. It was the day of “The Decision,” the ESPN television special in which LeBron, a free agent, would announce with which team he’d be signing. Half an hour into the special, freelance sportscaster Jim Gray gets to the point. “The answer to the question everybody wants to know, LeBron: what’s your decision?”

The camera slowly zooms in on LeBron’s face. He’s wearing a purple gingham button-down, and when I think back on this moment, it’s the print I remember most vividly, blurring as the camera moves closer. “Um, this fall… man, this is… this is very tough,” he says, and watching at age 16, I felt as though I’d been sucker-punched in the gut with one of his own giant hands.

It’s not as though we could blame him for choosing Miami. He was 25 and looking for opportunities to pass the ball, looking for a chance to play for a team instead of carry one. But we burned his jersey anyway, tore down the massive poster that hung downtown. And then, four years later, LeBron announced he was coming back, all was forgiven, and we put a ten-story, welcome home banner right back up on the Sherwin-Williams building, across the street from Quicken Loans Arena.

Cut to the 2014 home opener versus the Knicks, the first game LeBron played back at the Q. The game is preceded, predictably, by much fanfare. Fans wave Cavs glowsticks. There’s a light display on the court in which a basketball morphs into the Cleveland skyline. And then suddenly the buildings fall away, all lights cut to black, and the video screen alights. Splashes of footage from each starting player’s hometown cut across the screen. We pass under the OH-State Route 2 sign for the “Downtown Cleveland” exit. We pull up to the Q. We follow power forward Kevin Love onto the court. “This is our house,” a voice booms over an image of the wine and gold Cavaliers flag. “And there’s one thing we all know…”

The background strings reach a crescendo and go quiet. And here at last, on our own screen again, is LeBron, wearing his gold Cavs jersey and holding a basketball in front of his chest, raising his eyes to the camera. “There’s no place like home,” he says, and the crowd erupts.

There’s a lot about being a LeBron fan from Cleveland that rings fair-weather. But listen to the fans at this moment and you can sense it, the earnestness of our loyalty. This is our man, and we will accept him back with open arms.

***

Of course, we all love the story of the homegrown, hometown sports hero saving the day. That’s not singular to Cleveland. But what’s notable about LeBron’s story is how the myth of the sports savior takes on the tenor of fact. It’s much easier to believe that one man can come save your city—this, mind you, is the city where Superman was conceived—when you’ve already seen the impact that one person can have here.

Taking a moment to ignore the fuzzy feelings he generates and instead examine the numbers, LeBron has had a measurable impact on the economic climate of Northeast Ohio. In 2010, before LeBron left, Cleveland’s convention and visitors bureau estimated that between the bars, the eateries, and the game itself, the average fan spent about $180 per game to see the Cavs at Quicken Loans Arena. For the four years LeBron was in Miami, attendance was down by an average of 4,000 each game: if we assume that fans’ spending habits wouldn’t have changed in those years, we can extrapolate that the city lost out on $720,000 per game in that span. When LeBron came back, downtown bars generated between 30 and 200 percent more revenue on game nights than they did the previous season.

True, the figures do get a little squishy when you consider where this money is coming from. Most folks coming downtown for games are from Northeast Ohio, so it’s not like this is money pouring into the region that wasn’t there before. Perhaps the biggest impact LeBron has had on Cleveland’s economy is simply keeping the seats filled at the Q. The Cavs place an 8% admissions tax on their tickets, all of which goes to Cuyahoga County and the city of Cleveland. In the Cavs’ final season without James, the Q had five sellout games, and the city and surrounding territory stood to take in $2.03 million. The next year, his first season back, all 41 home games were sellouts—and the region pulled in $3.66 million. And that’s not to mention LeBron’s salary. He pays over a million dollars a year in income taxes, half of which goes to greater Cleveland. In short, with LeBron on the team, the Cavs can afford to pay greater Cleveland an extra $2 million per year.

Obviously, LeBron James is not the only person doing good things for Cleveland. But he’s certainly the most famous. Consider, too, that when you do something good for Cleveland, the degree of your benevolence automatically magnifies. In a world that largely chooses to ignore Northeast Ohio, even thinking about Cleveland is itself an act of generosity.

In Cleveland, which lacks so many forms of wealth, your main social capital is your commitment to the city. For those of us who are young, who don’t have the lived, felt memories of when the Rust Belt was battered into the post-industrial age, that commitment takes the form of your undying faith and pride in the city. Did you go to the Flats before all the clubs came in? Have you frolicked in the Cuyahoga River, despite the fact that it’s so polluted it’s caught fire 13 times? Can you hold back your laughter about the fact that we have a city organization called Destination Cleveland, formerly known as Positively Cleveland, whose employees are paid in actual American dollars to spread good news about this region? Do you love this place enough to stay?

If you’re from greater Cleveland, it’s ingrained in you since you’re a kid: if you leave, you forfeit the opportunity to mean it when you say you love this place. (LeBron, born and raised in Akron, gets it: at one point during “The Decision,” he says, incredibly, “I never wanted to leave Cleveland.”) If you leave, you’ve already slapped the city in the face. There’s nothing left you can give. Except for one thing, which LeBron must have also known: If you leave, you’re imbued with the power to decide to come back.

All of this rightly smacks of the quest narrative, or maybe the quest narrative turned hero’s journey. For me, it conjures up a maudlin image of a clutch of beleaguered Clevelanders stretching out their calloused hands toward LeBron, himself in the middle of his trademark chalk dust clap, descending from lake-effect clouds. The problem is that this understanding of LeBron’s return—here is our prodigal son, or maybe our prodigal father, back to save us again—oversimplifies the reasons why we welcomed him back instead of shunned him. It wasn’t just because we believed in him. His homecoming flipped the order of things on its head: his choice to come back to Cleveland meant that he believed in us.

***

Most icons, in our minds, are made of marble. They’re larger than life, or at least certainly larger than us, and they don’t regard us personally, or in real time, or even at all. But LeBron seems to have put a significant amount of effort into crafting a persona that is almost comically engaged with his fans, even beyond the typical Instagram or Twitter tactics. On the website for his I PROMISE initiative, which is sponsored by the LeBron James Family Foundation and which will provide some 2,300 kids eventual full scholarships to the University of Akron, he writes monthly messages to his sixth grade mentees and signs off, “Your friend.” An excerpt from a March 2015 entry about responding to failure with hard work reads, “I want you to be as proud of me as I am of you (for the record, that’s impossible because NO ONE is as proud of someone as I am of you).” The same website boasts an entire section called “MOM’S FUN FACTS,” in which, ostensibly, Gloria James shares tidbits about young LeBron’s habits and preferences. “Like all kids,” writes Ms. James, “LeBron enjoyed cartoons when he was growing up. His favorite Super Hero was Batman. Still to this day he loves Batman.”

For a celebrity, to be known is to play without the protective shield of mystery. For himself, LeBron has willingly shattered it. An icon does not send cupcakes to his neighbors as an apology for the increased traffic caused by his arrival, as LeBron did. An icon does not cycle with you, as LeBron does each summer, or share your love of Batman. But this is why Cleveland works so well as the backdrop to the LeBron spectacle: every time he thinks about us, every evening he spends in our city, he earns cred, simply because most citizens of the world actively try not to do those things. That he is still here means he still regards us highly. And so, paradoxically, the very thing that lifts him up to messiah-level is his closeness to us.

In the second century, Emperor Hadrian was known for traveling to every province of the Roman Empire on foot. Really, he rode on horseback, but he’d dismount a mile or so out of town and hoof it the rest of the way, so the effect was the same. He wanted to be seen as just another citizen of the empire, but at the same time, the fact that it was so notable a thing for him to do dispels that very notion. And, true, LeBron’s familiarity loses some of its punch when you consider the possibility—honestly, the likelihood—that it’s all part of the act. I was raised in the most doggedly optimistic city in America. A family friend from ten blocks down, a grown, reasonable man, last year earnestly posited to me that the reason why the Cavs had lost a string of recent games was because our team was too good, all of a sudden, and coach David Blatt didn’t know what to do with all that talent. But I live on the East Coast now and some of its culture has seeped into my veins—love of seafood, respect for variable topography, a healthy amount of abject cynicism—and with some distance from home I can’t help but wonder if we, the fans, aren’t the ultimate fabricators here, fashioning an idol who believes in us right back. Is being a LeBron fan in Cleveland simply a means to bear out our own self-importance, as a community sans any quantifiable means of assuring ourselves?

Because here’s the thing: LeBron is not one of us. He makes national news for sending cupcakes, and those cupcakes came in varieties that were designed in his honor. He makes headlines for doing yoga, for dancing, for not wearing a headband one day, for playing the violin, for biking to work. And if I’m being honest with myself, there’s no way his mother actually wrote those fun facts on his website.

But of course, Clevelanders already know this. We’re not naïve; we know he’s got a whole different experience from those of most folks in our city. He doesn’t personally have to face the blight or navigate the crumbling public transit, doesn’t personally have to worry when the CPD pulls him over. He’s the King, after all. The beauty, though, lies in how he navigates this tension, how he’s figured out how to move about the world and the city such that most of the time, there is no tension at all.

And so the other way to understand our veneration for LeBron, then—the beautifully un-cynical, Midwestern way—is to recognize that in worshiping him for simply believing in Cleveland again, we have quietly decided to place the emphasis not on celebrity or status but on faith. The question of whether or not it’s all a sham or a PR stunt at the end of the day is made irrelevant, overshadowed by the purest form of being a fan that you’ll ever find.

His fans get it, even the ones who live outside of Northeast Ohio. It turns out that to cast off all the cynicism and loudly, wholeheartedly believe in where you come from is not, in fact, Midwestern, but actually just feels nice.

***

As any sports fan knows, there are two distinct ways to cheer on your team. The first is your standard shout-your-lungs out adoration. And then the other is when it gets serious, when there’s only a few seconds left and you’re minimally down, or tied, and you stand up, and things are still quiet, and there’s something at stake. To be a Cleveland fan is to have the tensest of those moments pass into a tiny sigh every single time. Which is exactly the opposite of what happened last night when Kyrie Irving made a superhuman three-point shot and the clock ticked down to 0 in the Cavaliers’ Game 7 win over the Golden State Warriors.

The city and its sports teams have historically paralleled each other. After World War II, Cleveland’s economy flourished. Our population peaked. The Indians won the Series in ’48. The Browns dominated in the ‘50s. And then: white flight, free trade, shrinking opportunities in manufacturing. To close out 1978, we became the first major city in the U.S. to default on our federal loans. Our baseball stadium, and then the city itself, was deemed The Mistake on the Lake.

But that was a while ago. Nobody from Northeast Ohio is all that concerned about making our city seem revitalized; it already is. We’re home to world-renowned hospitals, a booming local food scene, the largest theater complex outside New York. Our metropolitan school system has made unprecedented improvements. Old news, all of this—but still, there was the nagging thorn in our side that was this 52-year-long championship drought, and thus, somehow, the need to defend ourselves.

Growing up, I’d let myself imagine what it’d be like if we won anything. It was a brief exercise; it’s difficult to picture without any historical context. All of the folks on my block who are old enough to actually remember a championship (Browns, 1964) are at the stage of their lives when they’ve already begun to forget. And so I wondered: Do we riot? Do we cry? Where do we congregate—right outside the arena, or two blocks away at Public Square, or over on East 4th? Do we host parties on the Rapid, using the train tracks as a parade route? Where even is our parade route?

There’s no real existential calamity going on here, obviously. Yes, we were the city with the longest championship drought, and that was a huge part of our municipal DNA, but nobody’s experiencing any identity crisis because of last night. We are simply, for the first time in generations, very, very happy.

And, too, the even more obvious and even more crucial point stands that it’s just basketball. To concern ourselves with wins and losses, when the loss of a game is of a gravity so many orders of magnitude removed from the loss of a life—or the loss of 50 lives, that devastating loss of security and freedom and vibrant human beings—even calling it by the same name rings profane. Cleveland’s actual problems—harboring a crime rate that’s 129% of the national average, or housing a police department that the Department of Justice investigated and found reprehensible, to name two—are complicated. Civic identity is itself complicated. It’s tempting to look to something as simple and constant as sports in order to determine how you measure up. But it’s not insignificant. A championship for Cleveland allows us to confirm for ourselves that, yes, we’ve made it; that yes, we were broken, but now we are not, or at the very least we are on our way.

LeBron is what permits Clevelanders to make sense of ourselves in this manner. He has engineered his cult of celebrity such that to be a true fan of LeBron James is simply to stand by him. And in return, you will be able to cling to the very statistically probable notion that he is glad to stand by you. We are all, it turns out, witnesses. We are Believeland.

So what now? We’ll cheer, we’ll cry, we’ll pack the streets. Somehow, we’ll dance on top of a fire truck. There’ll be the parade, and we’ll buy our championship gear. But after that, I don’t really know what we’ll do. We’re done hoping. We’re done praying. We can do whatever we want. And so my guess is we’ll probably return to what we do best: we’ll look out at our city and look forward to next year, to the season opener, to LeBron’s signature chalk clap before the game, all of us throwing up our hands not in resignation but in praise.

The damsel in distress trap: How “Penny Dreadful” betrayed Vanessa Ives

Eva Green as Vanessa Ives in "Penny Dreadful" (Credit: Showtime/Jonathan Hession)

In last night’s series finale of “Penny Dreadful,” Vanessa Ives—who had collapsed in recent episodes from the nuanced powerhouse at the center of supernatural London to the sort of two-dimensional Gothic heroine that inspired her—meets her maker. Quite literally, in fact. Her almost-lover (and long-fated protector) Ethan returns to London to save her from her bargain with Dracula, only for her to announce sadly that she can’t be saved. After Ethan shoots her at her own request, she collapses in his arms, her filmy white gown billowing around her, and announces happily she’s seen The Lord.

It’s a marvelously Gothic image. And it’s a terrible conclusion to Vanessa’s story.

Since “Penny Dreadful”’s pilot three seasons ago, death has always been in the cards for Vanessa. That, too, was sometimes literal, thanks to her tarot cards—one of this show’s many visual touchstones for faith, and one of its many gleeful touches of Victoriana. As one might expect from a show named after cheap Victorian supernatural thrillers, creator John Logan delighted in all the trappings of its nineteenth-century inspirations: this London was packed with sinister ballrooms, crooked alleys, blood-spattered theaters, foreboding museums, and gruesome waxworks. Vanessa and company were haunted by shadowy specters and witch spells and millenia-old prophecies from a possessed monk, and also by the inescapable ghosts of their own mistakes. (Again, sometimes literally; “Penny Dreadful” doesn’t miss a trick.) It was a stylized darkness that reminded us our heroes were dealing with supernatural forces that were not only dangerous, but perfectly at home in an age where mental institutions were as bad as anything Hell could find. Whenever Vanessa was possessed by the Devil—which happened with notable regularity, as befits a penny dreadful—the first horror was always the moment you realized how easily the Devil handles Victorian small talk.

But what initially made the show such a success was the ways it used its Victorian trappings as restrictions for its characters to push against. Some of those archetypes were no-brainers that powered the archly Victorian side of things: Dorian Gray was fated to be a malevolent louche, and Vanessa’s surrogate father Malcolm was a selfish Great White Hunter hollowed out by hunger for recognition. But some were allowed to struggle with the archetypes that spawned them: Victor Frankenstein’s questionable parenting became a conduit through which “Penny Dreadful” examined the suffocating Nice Guy patriarchy, and Lily—his victim-turned-enemy-turned-victim—emerged from the early docile days of her afterlife as a virago bent on avenging every woman who’d suffered at the hands of a man.

The coup de grace, of course, was Vanessa Ives. Courted by the devil from outside, and haunted by the devil within, she was the series’ unabashed icon. Anchored by a tour de force performance by Eva Green, Vanessa hides almost endless complexity. She’s more terrified of happiness than of things that stalk the darkness; she can’t admit to Malcolm that she’s lonely, but she seeks out Frankenstein’s Creature to debate theology and poetry (that old Victorian small talk). And though she suffered all-too-human doubts, her stony determination to vanquish the devil always materialized when all hope was lost. Anyone who’s seen Eva Green’s baleful stare doesn’t forget it; this was a woman out to conquer.

Vanessa’s faith was integral to her character. As a Catholic amid Protestants and skeptics, the rituals of her religion often crossed the line into protective witchcraft; her sigil was the scorpion, but she made the sign of the cross as often as she drew her talisman. Much of the third season (not to mention the series) has been devoted to the tension between Vanessa and that faith: whether it’s enough to save her, how much of it she can compromise and still keep her soul. And after losing her faith last season, she starts to see psychiatrist Dr. Seward to try to find strength in herself. (In true Victorian form, the therapist is the descendant of the good witch who’d changed the course of Vanessa’s life…and looked exactly like her.) The season’s fourth episode, “A Blade Of Grass,” overtly answered the question of how far Vanessa’s come by trapping her in memories of her time in the asylum, and revealing that the Devil was haunting her in ways she didn’t remember at the time. At the climax of the episode, she staunchly confronts both incarnations of the Darkness. She’s at her nadir, exhausted from Victorian medical torture and trapped inside her own mind, but when the Devil asks how she dares defy him, she has an answer: “I am nothing. I am no more than a blade of grass. But I am.” It’s enough; she wins.

This isn’t the same woman who, three episodes later, shows up at Dracula’s doorstep to kill him and succumbs forever less than five minutes later. So what happened?

In an object lesson for adaptations everywhere, the meta-narrative of Victoriana simply overtook its characters. It’s happened before that the series’ love of Gothic trappings swallowed individual psychology and subversive narratives; Malcolm’s partner Sembene never rose above the Mystical Other stereotype. But though Logan’s fascination with the dark side of Victoriana had served the story well in the past, it seems that in the end, the needs of the Gothic outweighed its own heroine’s journey. It’s not that she died; it’s been understood since Vanessa stared down her first vampire that this was dangerous work and death lurked around every corner. It’s that what happened to her was a defeat for the sake of another archetypal narrative; it’s that, in a show that’s been so fixed on the idea of women wielding power, the patriarchy won in overtime. When Vanessa can’t resist Dracula, it’s not because her character is struggling—it’s because we know Dracula always wins fair lady. It’s because the Gothic heroine who’s tasted of the dark is doomed.

Does Vanessa find agency in her death? Yes — as Logan himself explained to Variety, her choice pulls back the End of Days. But it has shockingly little emotional power. Vanessa disappears from the two episodes leading up to these finale moments, leaving others to fight the battles while she waits in an actual ivory tower for her saintly end. The moment is tragic — the death of a heroine is always meant to be tragic — but the scene seems cut from a different story than the season’s first half, and the overall effect of her death is merely bafflement.

It’s not as if the show is unaware of the power of its own subtext, either. In the penultimate episode, the captive Lily convinces Victor to abandon Dr. Jekyll’s complacency serum and let her go, explicitly claiming that even scarred and suffering women deserve to be themselves—nothing more nor less—and to live however they can. On a technicality, the show delivers that for Vanessa, who chooses her death. But the Vanessa who was a blade of grass is already long gone, and with it goes much of the series’ power. “Penny Dreadful” was at its best when using its most complex characters to poke holes in the Victorian patriarchy; in the end, it wants so badly to be Victorian (a funeral, a Creature, a Wordsworth poem whispered at a grave) that it forgets to be itself.

Religious faith is always going to be a tricky narrative to resolve. A handful of other shows are tackling the fall from grace and its aftermath, and all have had to negotiate how much space to devote to old-fashioned ideas of religion as protection: “Lucifer,” “The Leftovers” and “Bates Motel” question the limits of faith in a world filled with flawed humanity. “Penny Dreadful” engaged Vanessa’s faith with the gusto of a show that planned to tackle the theological gauntlet—and when faith failed her, it turned to a blithely Satanist idea of free will as the ultimate master, and belief in oneself the ultimate religion. It was an incredible setup for the final showdown between good and evil. But for all its good intentions, “Penny Dreadful,” like so many other Victorian stories, just couldn’t resist a damsel in distress.

“What we talked about was the work”: The nourishing intimacy of the writer-mentor relationship

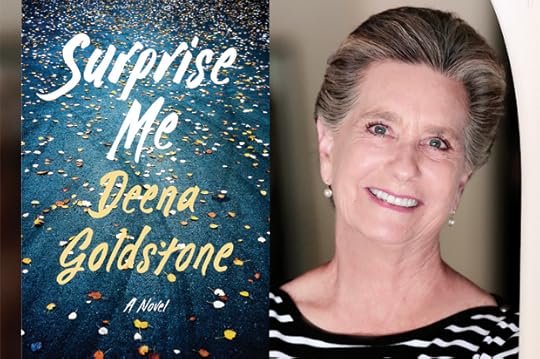

Deena Goldstone (Credit: Patricia Williams)

The day I met the man who would change my life, I was told I had one hour with him and that was all. I was a young writer, struggling to master a very demanding form – screenwriting, and he was a revered screenwriter with awards and spectacularly acclaimed movies in his resume. Just his name conjured up for me the kind of writing I most hoped to emulate – subtle, moving, powerful.

The producers who had hired me had “notes”. In Hollywood, euphemisms are generally employed so instead of saying, “We hate this first draft you’ve turned in,” they usually say “It’s a good start but we have some ‘notes.’” And then they schedule a meeting in which they proceed to tell you everything that could be conceivably wrong with your screenplay. A screenwriter usually leaves those meetings bloodied and beaten down.

This time, however, the notes were to be delivered by the revered writer. He had an advisory position with the company which was employing me and would occasionally comment on scripts as they came in. His office was on the Twentieth Century Fox Studios lot, and I was told the day and time of the meeting and that he would be expecting me.

As I walked the hushed and carpeted second floor hallway of the Executive Office Building at Fox, the only sounds the soft clacking of typewriter keys and the faint ringing of phones behind closed doors, I struggled to damp down my anxiety. Surely this wonderful writer would see all the flaws and every bit of awkwardness in the script I had turned in, only my second assignment as a screenwriter. The first hadn’t gone well at all and I doubted my ability to write this script, a fear I had admitted to no one but which consumed me each morning as I sat down to write.

I found his office door, and gathering my courage, opened it to find the revered screenwriter across the room, sitting behind a heavy wooden desk loaded with stuff – papers, small disparate objects, books, screenplays. I was immediately struck by how attractive he was. About 50 when we first met, he had a New England face composed of angles and planes. His hair was graying and full and unruly. It was his eyes which reassured me though – they were kind and held sadness.

He introduced himself and motioned to a small sofa positioned against a wall. I sat down and watched him rummage through his over laden desk for my screenplay.

“I liked the blackbirds,” he said, his eyes sorting through the mess in front of him. “They were unexpected.” And then he looked up at me, “I always like to be surprised when I read.”

The blackbirds were a detail, a small moment in a hundred and twenty page script about a teenager who is sent to prison for essentially being stupid and drifting along with a boy who was up to no good. In prison she begins an affair with a guard and gives birth to a baby behind bars. It was a true story I had spent months researching — meeting the girl, spending time in each of the three prisons she lived in, traveling the state in which all this had happened. I had made sure to put into the script as many of the real details as I could. I was convinced they made the story authentic and were far better than anything I could conjure up. But the screenwriter glossed over all that to focus on one of the scenes I had invented — “Tell me about the birds.”

I described pulling up outside the first prison set in a vast, flat landscape of marshes and seeing the large birds – they might have been crows — spread out across the empty land, and how I thought to put them in an early scene when the boy and girl first meet. What if I had the boy throw rocks at the birds and the girl stops him and the birds fly up in the air in alarm? Wouldn’t you learn something about those two people?

His eyes never left my face as I spoke. “Okay,” he said, “you need to get that kind of life into the rest of the screenplay.” But how, I wanted to ask but didn’t. The how was my job.

Instead he asked me questions – “Why does this girl go along with this boy when she knows he’s bad news? Why does she start up with the guard who fathers her child? Does she fall in love with him? How does she find the courage to sue the state to keep her child?” I answered the ones I could and told him I’d think about the others.

The hour passed so quickly, and the questions themselves seemed, somehow, to point the way for me. I stood up, mindful that my allotted time was over, and thanked him.

And then he astonished me by saying, “You need to rewrite the beginning, up to those birds, and bring those pages back to me next week.”

“Oh, no, I couldn’t ask you to take any more of your time —“

“Do you think I’m going to let you write a wonderful script…”

I am?

“ … and not be part of it?”

What? I was speechless.

“Next week. Does the same time work for you?”

I nodded, dumbfounded by his generosity.

And so I came back the next week and the week after that and the week after that, always with fresh, tentative pages I had struggled over in the intervening days. He would read them and we would talk. He never told me what to write and I never heard a word of criticism, only what he liked or what he wanted to know more about. We worked together for almost a year, just the two of us, in that small office at Fox, in that way. That was the only time we saw each other, the only time we talked. And what we talked about was the work.

There was something very akin to raising a child in what we were doing. We were nurturing this entity, our script, into being; understanding it in ways no one else could, loving it because we were nurturing it. There’s an intimacy to that kind of work.

But there was more, and here it gets even trickier to describe. We fell a little bit in love with each other during that year. But why? What was the particular alchemy which created first interest (why did he agree to work with me?), then trust (why could I willingly give him every meager, hard won page of script every week and know it would be received with care?), and then finally a very particular kind of love between us?

I don’t have a good answer. But isn’t that the way of love? It’s impossible to describe to others but is indisputably known to the participants.

If I had to put a label on the whole process, I would say he had mentored me and I had learned well. He had held a steadfast belief that I would find a way to write something “surprising” and worthy and so I had.

At the end of the year, we had a new screenplay. I turned the script into the company and the movie was eventually made. But that was the least important part of it all. What my screenwriter had given me far outweighed the modest movie which was made from my script.

There was a moment towards the end of our time together when we argued over the necessity of a comma in a line of dialogue. For close to twenty minutes! As we went back and forth, I realized there was more at stake than the comma. I was declaring ownership of the work, because here I was defending the placement of a comma. A comma! That was the moment I finally knew who I was — a writer, a writer who had just produced this script and it was good, just the way it was.

Over the next few years, he got married and then I did. I had my daughter. Both our lives got busier, more crowded, but we knew that we could always reach out to the other. And always, it was about the work.

Our roles changed a bit. He sent me screenplays he was working on to read and talk with him about. I continued to send him my work from time to time, when I was struggling or, sometimes, simply when I was proud. Gratitude became part of our equation, both of us supremely grateful to have the other to call on, to know that despite whatever else happened in our lives, which we rarely talked about, rarely shared, we would be the constant for the other. Over thirty years later, it is still about the work.

I understood that absolutely one night a year or so ago. I had had my first book published, a collection of short stories, and was having a reading in Santa Monica, blocks from his house. Now my revered screenwriter is in his late eighties and lives alone after the death of his wife. I invited him to the reading but didn’t expect him to show up. He didn’t like to leave the house, that I knew. He had read the book and loved the stories. He had communicated all that to me. That was enough.

But as the small crowd filtered into the room, I looked up from the lectern to see a distinguished older man, handsome still, sporting a cane now, and smiling tentatively as he stood at the back of the room. He had come! It had been so many years since I had seen him. Emails had replaced visits and phone calls and then, there he was.

“You came?!” I said as I embraced him. “You surprised me and came!”

He understood immediately the reference – to the blackbirds, to the beginning of our relationship – and his smile broadened.

“Of course I came,” he said as he returned my embrace, “You did such good work.”

Trump delegate calls on Ann Coulter, others to attack church with “blessed Ramadan” sign

The pastor of a small church in Pennsylvania was attacked by a Donald Trump delegate to the Republican convention who was incensed by a sign “wishing a blessed Ramadan to our Muslim neighbors.”

Rev. Christopher Rodkey’s of St. Paul’s United Church of Christ received a threatening voicemail over the weekend from a Trump delegate who berated the pastor for daring to speak positively about what he described as a “godless” and “pagan” religion.

“Pastor, I got your telephone number off the church’s voicemail,” Matthew Jansen, Trump delegate and Spring Grove Area district board member, began in one of at least two voicemails he left the Dallastown pastor over the weekend.

“It’s unbelievable that you would welcome them and wish them a ‘blessed Ramadan.’ Are you sick? Is there something wrong with you?” Jansen asked the pastor in a yelling rant, calling the sign “despicable.”

Jansen made good on his threat, posting a picture of the St. Paul’s Church sign as well as the phone number to the church on Twitter:

"Choose your battles but if this is your hill here is the churchs' # 717-244-2090." @AnnCoulter pic.twitter.com/k5HkYmwwyv

— Matthew Jansen (@TheMattJansen) June 11, 2016

While it doesn’t look like Jansen’s call to arms has reached Coulter (yet), his followers have reportedly continued to harass the church throughout the weekend.

After the church’s pastor identified the source of the original threatening call (Jansen did not leave his name or contact information in the first voicemail), he went public. The pastor published the recording of Jansen’s berating voicemail, contacted the Spring Grove Area School District and wrote an op-ed for the local paper reaffirming his solidarity with the Muslim community:

At first, I thought, ironically, he is spreading the message of tolerance. But then the phone started ringing. I had to disconnect the phone and answering machine at church. As I write this, five days later, we’re still getting calls.

Yes, Mr. Jansen had encouraged people to harass a local congregation for speaking words of tolerance.

Yes, York County, this is who we have elected to represent you at one of the major party’s conventions this summer and who we have elected to a school board, which makes policies for the education of children and teenagers.

A look into Mr. Jansen’s Twitter account is helpful in terms of context; the profanity can’t really be shared in the newspaper. Muslims, here called “Mohammedeans” pejoratively, are “invaders” and “need to be arrested and deported NOW!” The “damned” Muslims are pedophiles, terrorists and welfare-grabbing “parasites.” Trivial and flippant concern about “race baiting” and women’s rights. Empty — I assume — threats to riot at the RNC convention. Same-sex parents are “disgusting and wrong.”

From a school board member!

And this is just some of what’s been tweeted since June 1.

The cowardly and frightened message, veiled as belligerent alpha-male baiting left on my phone’s voicemail, makes a whole lot of sense knowing the context from where it comes. His Twitter directly represents the very definition of islamophobia as a fear.

But what concerns me most is that this is who York County has selected to represent at the Republican National Convention. This is who a local school district has elected on a school board: someone who hates Muslims, despises gays and calls some parents “disgusting and wrong.”

“This isn’t about me and him or the church and him. When I saw what was on his Twitter page, that’s what alarmed me, and he continued to put things on there. That’s between him and school board,” Rev. Rodkey told the York Daily News. “This is a church that is interested in religious tolerance.”

Still, Jansen continued to defend his harassment campaign in the face of public outing.

St. Paul’s sign “was over the top as far, as I was concerned,” Jansen told the York Daily News over the weekend, adding that he believed the message to be “blasphemous.”

But by Monday morning, Jansen had posted a message on Twitter saying, “I do apologize for venting to the church. I was out of line.”

Jesus died for hardline islamist just like he did me. I do apologize for venting to the church. I was out of line. https://t.co/ZhT2vOXufI

— Matthew Jansen (@TheMattJansen) June 20, 2016

“I’m going to practice forgiveness and move on,” Rev. Rodkey told the York Daily News Monday.

Jansen, for his part, offered a pray to a Muslim organization:

I will take a close look at your organization. And I will pray for your safety. https://t.co/6gliDOTYvE

— Matthew Jansen (@TheMattJansen) June 20, 2016

"No you're not the only one John. Very unsettling." https://t.co/hBUDTuK22i

— Matthew Jansen (@TheMattJansen) June 20, 2016

Good guy with a gun: “Free State of Jones” trailers raise on-going questions about film violence

Matthew McConaughey in "Free State of Jones" (Credit: STX Productions)

Fans of history, the Civil War, and serious acting have a lot of reason to look forward to “Free State of Jones,” a film due this month that tells the story of a Mississippi farmer who leads an armed rebellion against the Confederacy. Directed by Gary Ross (“The Hunger Games”), the film is based on the life of Newton Knight, a Confederate soldier who argued that the war was about making poor people fight to keep the slaveholder class rich; he enlisted local farmers and slaves to resist the Confederate army, leading to numerous violent clashes and, later, the declaration of a free integrated community in Jones County, Miss.

It sounds fascinating even before you know that Knight is played by a grizzly bearded Matthew McConaughey, who makes stirring speeches about how “every man’s a man,” designed to inspire his troops.

The problem, or at least the dissonant element, with the trailers released on the movie is that there is gun violence in almost every scene. And the guns are presented as justice-bringing saviors. “The last time I checked, the gun don’t care who’s pulling the trigger,” Knight tells a man surprised to see young girls aiming rifles at him. And black, white, women, men, young, old – everyone seems to be shooting in these trailers.

Of course, there’s no way to recount this tale without showing guns. But if the movie is as bloody as the trailer suggests, it could be a disturbing presence so soon after the Orlando massacre, and with images of gun violence in the minds of so many potential audience members.

It raises two questions. First, will people be shaken up by the violence here? “Free State of Jones” does not seem to be as graphically, gleefully violent as Quentin Tarantino’s movies. But Americans have gotten more and more addled by the steady drumbeat of shootings – which reached a new level of bloodshed with the Pulse massacre. Orlando, coming so soon after the San Bernardino terror, has disturbed people in a very deep way. So far there has not been a significant discussion about the role of violence in movies, TV, and video games, but it could still happen: Amy Schumer has just removed a scene of gun violence from a film she is working on with Goldie Hawn. (Schumer has said she was devastated when two people were shot at a screening of “Trainwreck,” a film she directed, last summer.)

Second, should filmmakers limit the violence in their movies? The research is not conclusive, but some of it seems to chronicles the damage that media violence does to the brains of young people. “Denial is a powerful tool,” says a Psychology Today story about an Indiana University study. “Just like smokers who have a developed rationality on why it’s okay to keep puffing away, many parents/people will take the same stance on media violence with a plethora of reasons as to why it’s really no big deal.”

The larger problem, of course, is that it’s impossible – and repressive – to tell studios to stop making violent movies. Whether we’re talking legally — U.S. law gives freedom of speech a pretty central place – or economically — the studios make an enormous amount of money from their most violent films – a wholesale rethinking of cinematic gun violence is not bloody likely.

But if a significant portion of the audience loses its fondness for movie violence, and chooses to see other films, or filmmakers followed Schumer’s lead and removed a scene here and there, Hollywood would start to move in the right direction rather than the drift toward nastier and nastier that it seems to be on.

As for “Free State of Jones,” the movie looks good. Maybe its story needs all of the guns and cannons and killings. But here’s hoping that filmmakers – and people who cut trailers – will adapt to the post-Orlando world a little bit.

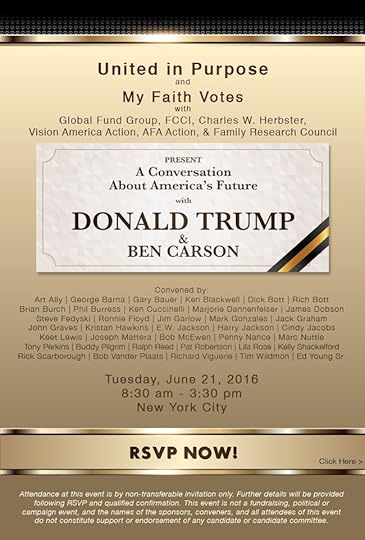

Trump courts the homophobes: He says he stands with LGBTs, but now he’s meeting with anti-gay Christian leaders

James Dobson, Donald Trump, Tony Perkins (Credit: AP/Susan Walsh/Charles Rex Arbogast/Reuters/Brian Frank)

In the days after the Orlando shooting, Donald Trump has been busy positioning himself as a great champion for LGBT Americans, claiming during a speech last Monday that he, not Hillary Clinton is “really the friend of women and the LGBT community” and claiming, during the middle of last week, that the “LGBT community, the gay community, the lesbian community — they are so much in favor of what I’ve been saying over the last three or four days”.

This is, of course, a ridiculous lie, as actual LGBT leaders hastened to make it clear that they do not support Donald Trump for president. But now there is more evidence, besides common sense, that Trump’s posturing this past week is nothing but an opportunistic gambit.

Tuesday, Trump is having a closed-door meeting in New York City with a coalition of Christian right leaders, titled “A Conversation About America’s Future with Donald Trump and Ben Carson.” The meeting was first reported a month ago, and while the guest list has been secretive, reports indicate that it’s a veritable who’s who of the nation’s sex police and LGBT haters, such as the Southern Baptist Convention head Ronnie Floyd and Focus on the Family’s James Dobson.

KFSM out of Arkansas got a screenshot of the RSVP page, with a list of some prominent attendees. There are no real surprises on this list, which is composed of anti-choice and anti-gay heavies in the Christian right world.

The Family Research Council (FRC) has confirmed they play a role in the organizing of the conference, which makes sense, their president, Tony Perkins, has been working closely with Ben Carson. This is especially troubling, as the FRC is so toxic in its anti-gay bigotry that the Southern Poverty Law Center deemed them a hate group.

Perkins is particularly fond of using demonizing, hateful rhetoric about gay people, saying they are “hateful” and “vile”, and that they have an “emptiness within them” because they are “operating outside of nature”.

He’s also compared being gay to being a terrorist, saying that terrorism is “a strike against the general populace simply to spread fear and intimidation so that they can disrupt and destabilize the system of government” and “That’s what the homosexuals are doing here to the legal system.”

Despite being such a noxious bigot, Perkins gets on TV a lot, usually by toning down the rhetoric and pretending he’s not a stark raving hater. But, after such the vicious crime against LGBT people in Orlando, it appears at least one network is realizing that such a bigot is not the person you want to turn to in times like these.

As Zack Ford at Think Progress reports, ABC News initially had Perkins on their list of guests for “This Week”. The inclusion triggered a massive outcry from pro-gay groups, who did not think it appropriate to have someone who hates gay people on air to talk about a murderous incident aimed at gay people. The liberal Christian group Faithful America put out a petition asking ABC to drop Perkins because he “has repeatedly accused gay men of molesting children”.

ABC quietly dropped Perkins from the line-up.

But it appears that Trump, despite wanting to appear friendly to LGBT people, doesn’t seem to worry about how it looks to meet up with Perkins and a huge cluster of anti-gay conservatives. The Marriott Marquis in Times Square confirmed that the meeting is still scheduled for Tuesday.

As of publication time for this article, neither the Trump campaign nor My Faith Votes, which organized the meeting, have responded to requests for comment.

Ironically, the pressure last month was not on Trump to avoid meeting with anti-gay bigots, but more on these Christian conservative leaders not to meet with Trump. Understandably, many in the evangelical community are wary of tying themselves to a candidate who, for all that he claims to be a devout Christian, clearly does not darken the doors of church enough to understand even the most basic aspects of his religion.

The criticism was enough to drive Ronnie Floyd, the president of the Southern Baptist Convention, to defend himself in a May editorial for Fox News.

“While I have no intention of endorsing Donald Trump — or any other candidate for that matter — I believe it is incumbent upon me to learn all I can about each candidate and their platform,” Floyd wrote.

Floyd added that he would “would be willing to also meet with Hillary Clinton”, but there have been no efforts from Christian right forces to make such a meeting happen.

Now the shoe is on the other foot, and it’s Trump who should be warier about the company he keeps.

Michelangelo Signorile of the Huffington Post wrote a piece, published June 10, warning that Trump’s quiet alliances with anti-LGBT groups showed that Trump “very much will be a force against LGBT equality if elected president”. That was two days before the Orlando shooting dramatically reminded the country that anti-gay bigots are not harmless cranks, and that poisonous anti-LGBT rhetoric has real consequences for real people.

Now Trump is pretending, oh so conveniently, to be a friend to LGBT people. But someone who actually cared would not have this meeting. Just as Trump is happy to exploit bigotry against immigrants, Muslims, women, and black people, he is happy to exploit bigotry against LGBT people in order to get votes. Any lip-flapping to the contrary is just more of the same old lies that Trump loves spewing.

Joe Biden blasts Trump without once mentioning his name: The “insecurity of a bully” is not “what has always made America great”

Joe Biden (Credit: AP/Diego Corredor)

Without ever mentioning his name, Vice President Joe Biden used another one of his major policy addresses to take shots at presumptive Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump.

“Wielding the politics of fear and intolerance, like proposals to ban Muslims from entering the United States or slandering entire religious communities as complicit in terrorism, calls into question America’s status as the greatest democracy in the history of the world,” Biden said during an address to the Center for New American Security on Monday.

“As we continue to urge our allies to do more, generating our closest partners as liabilities is a serious and tragic mistake,” the vice president continue, alluding to the GOP’s controversial candidate. “Our values are what draws the world to our side.”

“That’s what has always made America great,” he said. “Not empty bluster. Not a sense of entitlement that fundamentally disrespects our partners. Not the attitude and insecurity of a bully.”

“If we build walls and disrespect our closest neighbors, we will quickly see all this progress disappear,” Biden argued, forcefully pushing back against Trump’s campaign of bigotry. “Alienating 1.5 billion Muslims–the vast, vast majority of whom, at home and abroad, are peace-loving–will only make the problem worse. It plays into the narrative of extremists”:

“Some of the rhetoric I’m hearing sounds designed to radicalize all 1.4 billion” Muslims around the world, Biden said:

Adopting the tactics of our enemies — using torture, threatening to kill innocent family members, indiscriminately bombing civilian populations — not only violates our values, it’s deeply, deeply damaging to our security.

[…]

Why in God’s name are we giving them what they want?

Biden argued that Trump’s campaign is likely to cause “a return of anti-Americanism and a corrosive rift throughout our hemisphere.”

“I’ve never been more optimistic about America’s capacity to lead our world to a more peaceful and prosperous future. But our leadership does not spring from some inherent American magic — it never has,” Biden said, warning against the potential the U.S. could “squander all of our hard-earned progress.”

Instead of Trump’s “sound-bite solutions in a world defined by complexity,” Biden argued, it is “our willingness to see challenges on the horizon and step forward to meet them first, our ability to lead by example and draw partners to our side. That’s what has always made America great.”