Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 723

July 10, 2016

Marketer-in-chief: Is Donald Trump only running for president to exploit the business opportunities?

Donald Trump (Credit: AP/John Minchillo)

Could it be possible that Donald Trump’s entire presidential candidacy was cooked up out of a grand marketing scheme?

It sounds like a wild conspiracy theory. But then there it is, right before our very eyes. Again and again, we see Trump standing before the global media cameras knowing full well that he would receive wall-to-wall coverage, and instead of talking about policy, he shamelessly hawks his own Trump products.

This may be the greatest free marketing campaign of all time.

A recent example of this was on full display with Trump’s surreal news conference at his golf course in Turnberry, Scotland. Trump was not in Scotland to meet with any foreign dignitaries. No, nothing like that. Trump flew to Scotland to attend the opening of his golf course.

Only hours before, Britain had plunged the world into turmoil with the Brexit vote to leave the European Union, but Trump had more important matters to announce to the world. Trump stood before the global media assemblage and delivered a lengthy sales pitch all about the luxury features of his new golf course.

“The hotel is built to the absolute highest standards of luxury,” he declared, “and the course is built to the absolute highest standards of tournament golf.” He described the new “incredible” luxury suites. “You should try and get to see the suites,” he continued, “because they are two of the most beautiful suites you’ll ever see.” He described the brand new sprinkler system and the several redesigned golf holes in his typical superlatives like “spectacular,” and “the greatest par 3 anywhere in the world,” and on and on.

He sounded like a used car salesman pitching brand-new tires and a recent paint job. But from a marketing perspective, Trump’s sales pitch for his new golf course reached millions of people all around the world, for free.

This spectacle was eerily similar to the bizarre infomercial press conference Trump put on a few months ago after his primary victories in Mississippi and Michigan. Trump took the podium in front of the media, but this time, he was surrounded by display racks filled with Trump products that are for sale to consumers. Cases of wine from the Trump Winery were on display. Crates of Trump bottled water were stacked up. Cuts of Trump steaks were carefully arranged on a wooden cutting board. Copies of Trump magazine were on hand. And then Trump crassly began hawking his products. He held up before the media cameras a recent issue of Trump magazine and proclaimed it to be “great.” He pointed to the racks of wine bottles and claimed that he makes “the finest wine, as good a wine as you can get anywhere in the world.” He declared that his winery is “the largest winery on the East Coast” and that it is “one of the great vineyards of all time.” Never mind that Trump himself does not drink alcohol. On display for all to see was a real huckster eager to sell anything to anyone who is gullible enough to fall for the sales pitch. Here was a guy who was simultaneously selling bottled water along with a presidential candidate.But perhaps Trump has in mind an even larger marketing strategy.Trump’s next major real estate development project is the October grand opening, just in time for the presidential election, of a new luxury hotel right in Washington, D.C., in the old post office building on Pennsylvania Avenue just down the way from the White House.

What better way to guarantee a stampede of customers for his new hotel than to be elected president? Just think of the possibilities here.

If Trump were elected president, the hotel bookings would be through the roof. Anyone and everyone traveling to Washington, D.C., to conduct official government business would, of course, wish to curry favor with the president of the United States, and one convenient way to achieve this would be to lodge their entire visiting delegation at the very hotel owned by the president.

President Trump would certainly know who was staying at his hotel – and who was not – and thus he would know full well who was or was not favoring his establishment.

Nothing needs to be said. No arrangements need to be made. No express quid pro quos are necessary. It’s simply obvious. Everyone will know that if they desire favors from President Trump, they must patronize Trump properties and buy Trump products. And just think of all the possibilities for large events at the hotel. What a fantastic opportunity for lobbying groups, industries, corporations and even individuals to funnel money to the president by selecting the president’s hotel for industry conventions, corporate functions and personal weddings. Come to think of it, these wonderful opportunities would not be limited to only Trump’s one hotel in Washington, D.C., but would apply to all of Trump’s properties around the nation. And around the world as well. President Trump would certainly know who was and was not booking events at his properties nationally and internationally. In fact, these wonderful opportunities would not be limited to only Trump’s hotels and golf clubs, but would apply to all of Trump’s products. National restaurant chains could begin offering Trump wines and steaks, retailers could start selling Trump ties, and just about anyone could start stocking Trump bottled water. The possibilities are endless. Perhaps Vladimir Putin could make a deal to begin importing Trump products into Russia. It is a marketer’s dream.Trump says that there would be no conflict of interest with his businesses if he were elected president because he would officially step down from his company and his adult children would run the business.Seriously? Does anyone actually believe this? The company is a private, closely held family business, and the money from the business would still flow into Trump’s immediate family. Does anyone actually believe that President Trump would have no idea what was going on inside his cherished business being run by his very own children?

C’mon.

Anyone who falls for that pitch deserves President Trump.

July 9, 2016

Online gambling’s weird new frontier: The $2.3 billion business of garishly painted virtual assault rifles

The AWP Dragon Lore skin. (Credit: YouTube/McSkillet)

If you’ve never played Counter-Strike, you might not know what a weapon skin is. If you haven’t used weapon skins, you likely don’t know about the $2.3 billion gambling industry that’s grown up around them.

And if you have no idea what any of these things are, you’re going to have a rough time deciphering the strange weapon skin gambling scandal currently roiling the competitive video gaming world. But the unfolding drama raises big questions about the roach-like immortality of online betting, and its ability to draw in minors with parents’ credit cards. No matter how regulators take action, it seems like there’s always a new way to gamble.

Already, two Counter-Strike stars are being sued by a parent on behalf of her child, who claims they fostered an illegal online gambling scene marketed to minors. And that could just be the beginning.

From The Start

The story starts, more or less, in 1998, when the new video game company Valve released its first game, Half-Life. The game was a huge hit with critics and gamers alike, and remains one of the most influential of all time. With such popularity came a community of modders: often-independent developers who used the core of Half-Life to build their own games.

Counter-Strike was one of the most successful of those mods, an online multiplayer game where players competed as either terrorists trying to complete an objective like planting a bomb, or as counter-terrorists trying to kill them and foil their plans. Counter-Strike was so popular, Valve quickly bought it and hired its developers, beginning a series of successful Valve-made Counter-Strike games.

Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (CS:GO), the latest in the series, didn’t initially do very well after its release in 2012. For much of its first year, the 13-year-old and 9-year-old previous versions were each more popular than the new game. But a year after CS:GO’s release, Valve introduced weapon skins, and it changed everything.

In-Game Gambling

In 2016, Valve is not just a game publisher, but also the creator of Steam, the most popular service for buying, downloading, and playing computer games, and a requirement for playing CS:GO. The nice thing about owning the platform is that getting gamers to buy things in games with real money is pretty easy. After all, they already gave Steam their credit card numbers to buy the game in the first place.

It only takes a couple clicks to get from a game of CS:GO to buying what’s known as a “crate,” a $3 shot at finding a rare weapon skin. Like buying a pack of Pokemon cards or baseball cards in days of yore, this is already a low-level sort of gambling. You hope for a holographic charizard or a Dragon Lore AWP skin (currently valued at $1,300), but you’re probably just getting a few magikarp or a 60 cent pistol skin. Steam also allows buying and selling of skins between members of its community (from which Steam takes a cut, of course), but it caps sale prices at $400, meaning the real money exchanges hands elsewhere.

Steam has faced criticism for this feature, especially due to the fact that anyone, including children, with access to a credit card or Paypal account can participate. The official minimum age for registering a Steam account is 13, but that limit is thwarted easily enough by entering whatever age the user wants to.

New Paint Jobs Change the Game

Weapon skins are simply paint jobs for the guns and knives in CS:GO. The normal guns in the game look like guns: gray, metallic, and that’s about it. With custom skins, bright pink, green, blue, red, and orange are popular colors, and dragons, skulls, swirls, and gradients are dominant motifs. This results in the gritty, realistic terrorists looking like they raided an Ed Hardy laser tag arena for their weapons. To this untrained observer, there’s no difference in beauty between a 60 cent skin and a $1,300 skin. That is, they seem equally ugly. And to be clear, different skins do not affect the game in any way.

Skins provide status symbols in a game that isn’t big on individuality. A rare skin is a sign of a dedicated player, and it provides an excellent visual identifier for the elite CS:GO players who participate in competitive matches for spectators, which itself is a major industry.

What skins really added was an easy way to gamble. Competitive matches helped turn skins from simple collectible items into a currency for gambling. Third-party sites appeared quickly, offering the ability to bet skins on games, turning them into a sort of currency. Top CS:GO teams make big money from gambling site sponsorships and the sale of stickers, another complex, lucrative virtual item that’s outside the scope of this story. At least one CS:GO team was even discovered betting on their opponent and purposefully losing a match in order to win tens of thousands of dollars in skins, resulting in the players being banned by Valve.

From that first virtual casino emerged a secondary casino: rather than collecting bets on CS:GO games, many newer sites allow players to bet their skins on a virtual coin flip. Two or more players face off by putting all their skins in a (virtual) pile, the site sets odds based on how much value each participant put in, declares one of them the winner by chance, and gives the winner all the skins. This is the type of gambling provided by the site CSGO Lotto, which is now the center of a corruption scandal.

The Scandal

Two popular YouTubers in the CS:GO community, Trevor “TmarTn” Martin and Tom “ProSyndicate” Cassell, were exposed over the Fourth of July weekend as the owners of CSGO Lotto. This is significant because they have both released multiple YouTube videos promoting the site, with no disclosure that they have any connection to it.

In a now-private video, Martin, the president of CSGO Lotto, introduced the site like this: “We found this new site called CSGO Lotto, so I’ll link it down in the description if you guys want to check it out. We were betting on it today and I won a pot of like $69 or something like that, so it was a pretty small pot, but it was like the coolest feeling ever. I ended up following them on Twitter and stuff, and they hit me up and they’re talking to me about potentially doing like a skin sponsorship.” Other videos with titles like “HOW TO WIN $13,000″ showed Martin and Cassell winning big on the site and also contained no disclaimer at the time.

The YouTube channel h3h3Productions built on work done by another YouTuber HonorTheCall to expose Martin and Cassell and explain the scandal in a well-researched video:

After his ownership of the site was revealed, Martin issued a non-apology on YouTube, insisting that it was “a matter of public record” that he owned the site, and that it should have been clear enough to his viewers. After the story broke, he appears to have gone back and edited the descriptions of his videos mentioning CSGO Lotto to add a disclaimer revealing his relationship to the site.

As this news was breaking, an unrelated YouTuber confessed in a video that a different gambling site, Steam Lotto, paid him to participate in and broadcast a rigged skin lottery for promotional purposes. His video revealed that this kind of rigging is possible, which opened the question of whether Cassell and Martin rigged the lotteries in their videos.

A class action lawsuit was filed July 7 by a woman on behalf of her minor son and anyone else affected, which names Martin, Cassell, CSGO Lotto, and Valve as defendants, and claims that “unlike traditional sports, the people betting on eSports are mostly teenagers.” The suit also says Valve “has knowingly allowed an illegal online gambling market and has been complicit in creating, sustaining, and facilitating that market.”

Ryan Morrison, an attorney who works on issues around video games, told PC Gamer it’s possible that Cassell and Martin could face penalties or asset seizures if the Federal Trade Commission takes an interest in the case as well.

Is Regulation Imminent?

Much of the attention to online gambling lately has focused on FanDuel and DraftKings, the two best-known daily fantasy sports companies. Daily fantasy sports sites take advantage of a 2006 law exempting fantasy sports from anti-gambling laws. But instead of players betting a small amount of money on a full season of football as in traditional fantasy sports, daily fantasy gamblers can lose hundreds or thousands of dollars in a day.

New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman shut daily fantasy betting down in his state for some time, but is about to be thwarted by the state legislature passing a bill to legalize the sites. Other states have attempted or implemented their own measures to either regulate and legalize or stop the industry. A top priority of regulation has been restricting gambling to those over 18 years old.

Counter-Strike skin betting has so far been untouched and unmentioned by regulators and lawmakers, which makes sense considering the odd little corner of the internet where it resides. But as increasingly large sums of money change hands, as evidence of rampant corruption mounts, and as more young children take up gambling and their parents take action, it’s going to be harder and harder to ignore.

Powerful crime drama “The Night Of” could be the hit HBO needs

Riz Ahmed and John Turturro in "The Night Of" (Credit: HBO)

Aspects of HBO’s limited series “The Night Of” are reminiscent of TV’s recent glorious past, when the so-called Golden Age of TV was newly hatched. It’s part premium cable homage to one of the medium’s perennially popular genres, the police procedural, but also a nod to the glory days of the network itself. The miniseries’ co-creator Richard Price wrote for “The Wire,” in which “Night Of” castmembers Michael Kenneth Williams and J.D. Williams also starred.

Before a viewer connects those dots, though, a different and more familiar name pops up in the opening credits: James Gandolfini. Tony Soprano himself has an executive producer credit.

Gandolfini played a huge role in making HBO the standard-setter for quality television drama, and “The Night Of” was meant to be his return to television, this time as rumpled, luckless attorney Jack Stone, as opposed to a mobster with anger management issues.

Had he lived to star in “The Night Of,” which premieres Sunday at 9 p.m., adding to the schedule may have proven to be a neat feat of programming kismet, seeing that HBO is in desperate need of a decent drama to step into the chasm “Game of Thrones” leaves whenever it’s not on the schedule. The channel still has brand cachet going in its favor, but suffered a blow to its rep when “True Detective” flamed out in season two after a bright freshman round, and “Vinyl” died out of the gate. It’s about to bid farewell to “The Leftovers,” which was more of a critical favorite than a hit with viewers. In essence, HBO needs its next great drama. Frankly, it needed it yesterday.

When Gandolfini died in 2013, “The Night Of” was put on hold, seemingly fated to float in development limbo (where, until recently, “Westworld” also hovered). Robert DeNiro briefly signed on to take Gandolfini’s role, but ultimately had to depart the project, leading producers to cast John Turturro – an actor whose build and comportment are nothing like the man for whom the part was originally intended.

Yet Turturro’s portrayal of Jack Stone helps to elevate the emotional and cultural complexity woven throughout this eight-episode limited series, making “The Night Of” into something much more than a cop drama with premium cable aspirations.

Place special emphasis on the word “helps” in that previous paragraph. Turturro may be the most recognizable face in the ensemble, but he’s not the whole show. Without Riz Ahmed’s riveting performance as accused murderer Nasir “Naz” Khan, the opening episode could have been pedestrian, even barely watchable at times.

“The Night Of” follows Naz, a first-generation American born of Pakistani parents, from the moment he makes the life changing decision to sneak out to a party. It’s a seemingly innocuous act for a young man, save for the fact that he takes his father’s taxi without obtaining permission.

His plans change when a beautiful girl (Sofia Black D’Elia) gets into the cab’s back seat and persuades him to spend the night with her instead. Their intoxicated interlude ends with him blacking out and waking up in her kitchen, only to discover that his one-night stand has been savagely stabbed to death. Every panicked decision Naz makes afterward buries him more deeply as the cops, led by legendary Detective Dennis Box (Bill Camp), gather more evidence implicating his guilt.

Ahmed, a relative newcomer, plays Naz at first like a calf rushed toward slaughter, blindly shuddering and stammering his way through the night in question and every moment that comes afterward. Circumstances crush him into something harder, but infinitely more lost.

That happens long after Turturro shuffles onto the scene, near the end of the pilot. From the moment he and Ahmed come together, “The Night Of” gains propulsion, powered by each actor’s respective talent for evoking poignancy. They’re deeply affecting in partnership, while also ably shouldering their respective halves of the story as the story progresses.

“The Night Of” is inspired by the five-episode first season of BBC’s “Criminal Justice,” which was created by screenwriter Peter Moffat, though it trades in a British kid for a wide-eyed business major living with his parents in Queens. Many structural elements remain the same, in that it takes us through a murder from every angle, from the beat cops and detectives building the case to the prosecutors and defense attorneys doing their best to destroy or free the accused.

The most moving moments take us into the lives of Stone and his client, Naz. Both Naz and the UK character upon which he was based (played by Ben Whislaw) come from working class families and fit the classic good boy archetype. He’s hard working and awkward, well-liked but socially on the fringes.

Turturro’s Stone lives with a terrible skin condition that makes him unable to wear closed shoes, adding to his abrasive personality. He’s accustomed to being underestimated; his ruddy, peeling feet and cheap outfits disgust people before he even starts talking, and his knowing this colors every interaction. Even his son is embarrassed by him.

But Stone and Naz are of a kind, both lost causes most are reluctant to champion, let alone touch. That Stone lands Naz’s case at all is chalked up to being in the right place at the right time. Meanwhile, Naz being a Muslim in post-9/11 New York adds a level of cultural and political fallout to his nightmarish journey, a facet lacking in the UK version.

“The Night Of’s” premiere clocks in at about 25 minutes longer that the first installment of “Criminal Justice,” which one could chalk up to the premium cable channel’s penchant of allowing auteurs to reveal character and plot detail at a luxurious (some would say plodding, if this weren’t HBO) pace.

But in this instance, there’s tremendous value in seeing Naz interact with his loving parents (Peyman Moaadi and Poorna Jagannathan) before he decides to sneak out in his dad’s cab. The crime he’s suspected of committing is a headline generator: a young man of Middle Eastern descent driving a cab suspected of butchering a rich white girl in one of Manhattan’s nicer neighborhoods.

Not only does Naz land a starring role on the cover of New York City’s tabloids, but Nancy Grace relishes passing judgment on him every night. Worse, it makes him a celebrity in Riker’s Island, where he falls into the hands of a convict at the apex of the jail’s social structure (Michael Kenneth Wiliams). The trial’s annihilating impact on his family only deepens the tale’s pathos.

In the midst of all this are a few humorous and humanizing elements, many of them involving an odd, somewhat symbolic subplot involving an abandoned cat that nobody wants, yet somehow insinuates itself into a main part of the story.

HBO subscribers can currently view “The Night Of” premiere on the channel’s online streaming service HBO Go, a smart tactic on HBO’s part given the episode’s deliberate pacing. Price and his co-creator Steven Zaillian (best known for writing “Schindler’s List”) lead us through every minute detail — every pause, misunderstanding and random interaction — that conspire to become the worst night of Naz’s life.

Zaillian, who directed the premiere, demonstrates an obsession with process that plays out in each episodes visuals. The camera hovers closely to Naz at every passing moment, at times glancing away for tight shots on the faces of passers-by who may or may not matter later on, or changing perspective to evoke a sensation of car crash voyeurism as Naz makes one bad decision after another.

The extra time Price spends guiding us into Naz’s life before the crime works pays off in later episodes, when the viewer is forced to confront the notion that the doe-eyed Naz might not be everything he initially seems to be.

Then again, maybe he is. That’s the trick “The Night Plays” on us; are we so keen to empathize with Naz that we don’t realize that his perspective might be unreliable? Or is the prosecution, led by a hardened district attorney (Jeannie Berlin), simply doing a great job of persuading the viewer and the jury to see things her way?

Immensely satisfying performances from the ensemble cast make this sense of ambiguity even sharper, particularly Camp, who plays Detective Box with a subtlety that leaves the viewer wondering as to his true feelings about his primary suspect. Glenne Headly also stands out as a polished, high-powered attorney who sees a PR opportunity in Naz’s case, which makes her only slightly less sharkish than Williams’s convict, whose designs on Naz grow more sinister with each passing chapter.

Tremendous portrayals by top-shelf talent are part of the HBO’s brand identity, key ingredients that made its finest dramas stand out on television. “The Night Of” has all the markers of being a drama evocative of what’s best about the medium. Even if it is a miniseries, it at least proves that HBO is still capable of delivering something distinct, powerful and true.

No transparency in Washington: How Senate members get away with burying campaign finances

FILE -In this Dec. 17, 2014 file photo, Sen. Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., talks about his agenda for a GOP-controlled Congress during an interview with The Associated Press on Capitol Hill in Washington. McConnell faces a nearly impossible task this election year: protecting Senate Republicans from the political upheaval of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign. Trump’s polar opposite in almost every way, the close-mouthed, uncharismatic 74-year-old finally got his dream job just last year and is trying to keep it, even if a Trump backlash provokes a Democratic tidal wave in November. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite, File)

This piece originally appeared on BillMoyers.com.

Last week, the books closed on the second quarter of fundraising for this year’s congressional candidates. On July 15, the latest campaign finance reports are due at the Federal Election Commission, giving the latest update on the money behind some of the people who want to represent us.

Why just “some?” Because, unlike candidates for every other federal office, those running for the 34 Senate seats up for election this year don’t have to file their forms electronically.

Yes, it’s true: In this, the 16th year of the 21st century, members and would-be members of the U.S. Congress’s upper chamber continue to send their campaign finance forms to the authorities on paper using the U.S. mail.

It’s egregiously inefficient, not to mention unecological, as the reports that have to be printed out generally run thousands of pages. It delays disclosure, and it costs taxpayers nearly $700,000 a year.

It has also produced rare bipartisan consensus on at least one campaign-finance reform bill: 45 members of the Senate, including such senior Republicans as Thad Cochran of Mississippi, Susan Collins of Maine, Rob Portman of Ohio and Chuck Grassley of Iowa, have signed on as cosponsors of the Senate Campaign Disclosure Parity Act, which would require Senate candidates, like candidates for the House and the White House, to file campaign finance disclosure forms electronically.

Despite this and despite the endorsement of the Federal Election Commission, an agency whose three Democratic and three Republican commissioners usually can’t agree on anything, the legislation — “a no-brainer,” in the words of its author, Sen. Jon Tester — has been languishing in legislative limbo for more than a decade. “None, zippo, none,” Tester says when asked if there has been any action on his latest version of the bill, introduced early last year. Pressed to say why, Tester gives a two-word answer.

“Mitch McConnell.”

McConnell, a Kentucky Republican, has been a fierce opponent of laws limiting campaign contributions and expanding campaign finance transparency since long before he became the Senate’s majority leader. But his opposition to this bill, which is backed by so many members of his own party and which hits the favorite GOP goals of increasing government efficiency and reducing government spending, remains mysterious. Tester said that McConnell has in the past put a hold on the bill, a parliamentary maneuver senators can use to discourage action on a measure. We’ve contacted McConnell’s office to request an explanation, but have not yet heard back.

In a budget document filed this year with Congress, the FEC recommends the Senate require e-filing and adds why: “Mandatory electronic filing for Senate reports will create considerable cost savings and will result in easier, more efficient dissemination of data.”

Unlike the electronic reports filed by House candidates, presidential candidates and a wide range of campaign committees — which can be downloaded within minutes of filing — Senate reports only have to be postmarked by the filing deadline, the FEC notes. They are mailed to the Secretary of the Senate, where staffers must then scan the reports — again, often thousands of pages — for transmission to the FEC, where it then can take up to 30 days to integrate them into searchable databases. Estimated cost is “at least $681,000 per year” for the FEC’s processing costs alone, the agency told Congress.

This isn’t the 1950s, Tester notes dryly. “We have the ability now to file electronically, save money, save work and let people know immediately who gave what to whom.”

In some ways, Tester seems an unlikely campaign finance reformer. As chairman of the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee, he’s one of his party’s top fundraisers this cycle, and a very successful one at that. As of its latest filing, the DSCC had raked in more than $88 million for the 2016 cycle, putting Tester nearly $20 million ahead of the counterpart at the National Republican Senatorial Committee, Sen. Roger Wicker (a Mississippi Republican who has co-sponsored Tester’s e-filing bill).

Yet Tester, a pro-gun Democrat who has won two hotly contested (and, for Montana, high-dollar) elections in a coal state, says he yearns for shorter campaigns and less time calling wealthy potential donors. “People think I spend more time on the phone than I do,” he said. “But even spending a minute a day on this stuff is a minute less than you spend doing policy or thinking about the farm.”

As the last part of that remark suggests, Tester, who will turn 60 next month, definitely does not fit the standard Inside-the-Beltway mold. He still raises grains, peas and beans on a tract of land that has been in his family for generations. Lest the organic farmer label make you think granola and Birkenstocks, Tester sports a flat-top haircut (the elaborately mustachioed barber who buzzes it for $8 was featured in not one but two of the senator’s campaign ads). And for trips back to Washington, he and his wife — his high-school sweetheart, Sharla — pack a valise filled with meat they butchered themselves. “Then we know what we’re eating, he told NPR last year.

Tester started his public career in the town of Big Sandy, which despite its name boasted a population of 598 in the last census. A high-school music teacher (he switched from saxophone to trumpet after losing three fingers in an accident at the family butcher shop as a youngster) before becoming a full-time farmer, Tester served 10 years on the local school board before being elected to the state Senate.

He traces his views on the unhealthy influence of money on politics to the populist tradition of his home state, which enacted ultra-strict limits on campaign contributions after an 1899 vote-buying scandal, only to see those limits thrown out by the Supreme Court after the 2010 decision in Citizens United v. FEC.

Although he says doesn’t “know [if] it will drive people to vote a certain way at the polls,” Tester supports campaign finance reform because “it’s the right thing to do.”

“People want to know what their elected officials are doing, and I don’t think we should be ashamed of what we are doing,” he says. “I think we ought to tell people. And if they don’t like it, they can tell us. It’s a good system.”

Moving campaign finance legislation forward will require more “public pressure” than currently exists, Tester says. “People don’t think their opinion counts, but it does.”

What kind of pressure? “Emails or phone calls or regular mail. Whenever there’s roundtable discussions, there are people there that bring it up. Whenever there are open meetings, there are people there that bring it up,” Tester says. “That is how you get to a point where you can make a difference.” The demonstrations staged by Democracy Spring and Democracy Awakening were fine, but “it’s better if we hear it at home.”

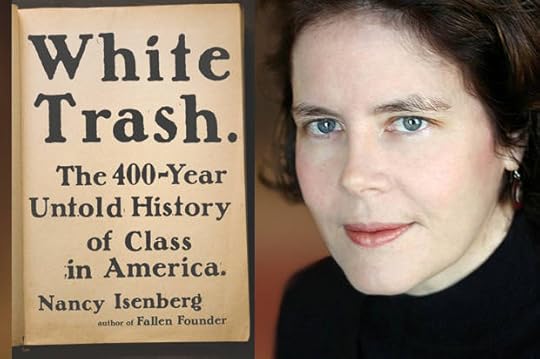

The deep roots of “white trash” in America: “Not only are we not a post-racial society, we are certainly not a post-class society”

Nancy Isenberg (Credit: Penguin/Mindy Stricke)

Nancy Isenberg’s book “White Trash” begins by looking at the characters in “To Kill a Mockingbird.” Both the book and the movie play with the divide between Atticus Finch, who is saintly and proper, and the poor white family, the Ewells, whose daughter’s false rape accusation is at the story’s center, as an example that there are two kinds of white people in the South. The book has been on Isenberg’s curriculum for 15 years, as part of a history class called “Crime, Conspiracy, and Courtroom Dramas,” which she teaches at Louisiana State University.

From “Mockingbird,” Isenberg’s book travels back to the first English arrivals on the American shore, tracing four centuries of how we talk and think about class (and race) in our most unequal union. It’s a bracing, sometimes upsetting read, beginning with its name, a term which still causes deep offense in some quarters.

When did you first start working on the idea of the “poor white” or “poor white trash?”

When you’re a historian, you gravitate toward certain issues. Part of it has to do with my graduate training; my first book dealt with race, class and gender. But it also had to do with when I was working on “Madison and Jefferson,” which I coauthored with Andrew Burstein. I became very aware of the importance of how Jefferson talked about the poor. He has this amazing line where, at the same moment that he’s calling for the education of the poor, something the Virginia legislature would reject, he refers to the poor as “rubbish.”

I became interested in figuring out the language: how do Americans talk about the poor? And then I realized that this is connected to the larger problem Americans have about class, that they believe a myth. We are told over and over again by writers, sometimes journalists, but mainly politicians, that we are an exceptional country, that we embrace the American dream. And what’s that rooted to this idea that we believe in social mobility. And we think that that idea, that promise, goes all the way back to the American revolution, that at that moment we broke free from the British system and that somehow we unburdened ourselves from the English class system. Now this is a problem that Americans have – they often prefer the myth over reality.

I began to look more closely at how Americans talk about class. There are a long list of slurs and of terms such as waste people, vagrants, rascals, rubbish, lubbers, squatters, crackers, clay-eaters, degenerates, rednecks, and of course, trailer trash. And you’ll see that just by paying attention to the words people use … what comes up over and over again, is the way the discussion of class throughout our history has forced on the centrality of land and land ownership, as well as what I call breeds, or breeding. And both of these big concepts come from the British. For example, the early indentured servants, the poor who the British wanted to dump into British colonial America, they were called waste people. And where does that term come from? It comes from the idea of waste land.

If a rich field, a productive field, is the sign of success, then fallow and untilled soil, soul that is ignored, the scrubby, swampy, completely worthless tract of land, is what waste land was. We forget – through most of our history we were an agrarian nation. That means that land ownership was the most important marker for designating an individual – and course we’re talking about, primarily, men – it was the most important signifier of civic identity, it was the first way to measure who had the right to vote, it also was a measure of independence. Americans didn’t believe everybody was free, you were only free if you had the economic wherewithal to control your destiny and where did that come from? It came from owning land.

It’s interesting, because you talk about the fact of owning land versus not, but you also talk about the very type of land: the idea that if you come from poor soil, weak soil, soil without nutrients, it also by osmosis makes you weak, less than vigorous, with these markers of poverty on your body. And this sort of leads to the eugenics idea of breeding, and good blood and bad blood.

The idea that the quality of the soil determines the quality of the people is an old English idea. And it also ties into ideas of demography. Another English idea is that the wealth and the strength of the nation are based on the size of its population. And how do you get a large population? By healthy land, healthy soil. So, those ideas are really important. And it becomes a common way to dismiss the poor. Part of it is that they are denied opportunities to buy the land, they’re always on the worst land, the marginalized land. But it’s also this idea that you do receive an inheritance. And this is another English idea I focus on – not only bloodlines, and lineage, and pedigree, but inheritance – this is what lays the foundation for the eugenics movement. Another theme the English were obsessed with was pedigree, and so these ideas become really central in the 19th century, to talk about race and to talk about poor whites, because they begin to be seen in the early 19th century as clinical specimens.

Particularly when they talk about the clay eaters and the sand hillers, they are identified by their yellow skin, which is equated to tallow or parchment – this is a theme that picks up later, that poor whites are not quite white. And their children are seen as talking on the qualities of the poor soil they live on. Their hair is compared to crops, because it’s bright white. They’re seen as a strange breed apart. And that’s also really important for class, because what it means is that there’s no point in giving the poor charity, because they’re trapped, their fate is set, their destiny is set, because they pass on these qualities, these traits, form one generation to the next.

One of the other really strange things that I think we’ve forgotten about the way in which race and class get intertwined. If you look at the embrace of social Darwininsm and evolutionary theory, and again this is building on the old ideas of animal husbandry, that you can breed people the way you breed dogs, there is the idea that poor whites are evolutionarily backward, they are unevolved people. And this particularly gets attached to those who live in Appalachia, the hillbilly. At the end of the 19th century there’s an attempt to recover these people as a kind of purer Anglo Saxon, that they have been protected from being corrupted. But the dominant theme is that they have not evolved at all.

There’s this idea that the poor white is marked by the connection to this terrible land and this bad inheritance, but at the same time there’s this anxiety that some of them could pass into respectable society, and then bear children that would take you back, and that’s what leads to the sterilization movement.

Yes, this is a really disturbing thing, and it also similar to race. The idea of passing goes back to the English idea of class passing – the servant who marries the lord – that same fear becomes really important, particularly at the beginning of the 20th century, and it overlaps with the eugenics movement. One of the things I focus on is the racial integrity act of 1924, which is passed in Virginia, and it’s a perfect example. Because what is acknowledged by elites and the middle class is that if you look at where poor whites live and socialize, they’re more likely to interact with free blacks, so their fear is that somehow that if we don’t clearly distinguish who can marry who, which is what the racial integrity act does, and we make sure that we designate all people who supposedly have black blood, and red blood, because they became equally concerned about Native Americans, there’s also this equally important fear that blacks and Native Americans are more easily going to have sex with poor whites, and then the poor white will rise up and contaminate the middle class and the upper class. What we’ve forgotten about is that this obsession with pedigree, this obsession with controlling the boundaries between not only races but classes, is a really central part of our past and our history.

This goes hand in hand with this myth that we’re a socially mobile country. So, we say that social mobility is a good thing, but if people were truly socially mobile, it terrifies people who are at the top of the heap.

Right. There’s this strange idea – I talk about this particularly in the 1960s and early 70s – suddenly the middle class has become boring. And if you think about the language of assimilation, what that means is that you erase all the traces, anything that would be seen as contributing in a negative way to society. You have to fit in, so that means you have to adopt the dominant language, you have to dress a certain way. And this is across the board of how we measure assimilation.

But in the ’60s and ’70s, suddenly the middle class is being associated with TV dinners, and all Americans somehow want to rediscover their roots. And this is linked to Alex Haley discovering his African roots, and Jewish writers who looked at the New York Jewish ghetto praised the idea of [as one wrote] of having “a ghetto to look back to.” “But while it’s nice when the ghetto is in the past, or the people coming over on Ellis Island are at a distance, people are still very fearful about living next to someone who isn’t of the same class or the same background.

So, the other thing I talk about is that class has a geography. Not only has our country particularly since the World War II period, where you have the rise of suburbia and the middle class, reinforced racial segregation, we’ve also imposed class zoned neighborhoods. And what could be a better way of ensuring that people are divided, that people measure each other by the value of the land that they own – owning a home is still considered the most important measure of being in the middle class.

The pedigree issue, not only does it raise the importance of the eugenics movement – and I highlight that this wasn’t a marginal movement, it was promoted by academics, politicians, prominent speakers, president Theodore Roosevelt was a eugenicist, and by 1931 you have 27 states that had sterilization laws on the books, so this was not a marginal movement. But when we pay attention to pedigree, that explains why this movement could be so widespread and so popular and so readily accepted as a justifiable way for Americans to protect the population. And we know that this is still with us today. This is one of the things I’ve been noticing about Donald Trump. He’s obsessed with pedigree! It starts with birtherism and his attacks on President Obama. It’s played out when he attacks the judge, and claims this guy couldn’t make a decision because of his Mexican heritage. And now he’s been going after Elizabeth Warren and calling her Pocahontas and claiming any of her claims to Native American background is a lie, is a fraud.

But at the same time, Trump appeals to voters who some people might call white trash voters. He embodies this kind of excess that you talk about when writing about Dolly Parton, Tammy Faye Baker. He’s tacky. He’s like a caricature of a rich person that appeals to poor people.

Right. And this is one other thing I talk about: the problem of our American democracy. And we can take it back to Andrew Jackson. An Australian writer wrote in 1949 that we don’t have a real democracy, we have what’s called a democracy of manners. Which means that people will accept huge disparities of wealth, but they will vote for someone who pretends to be just like us. And how do politicians do that? In Trump’s case, he steps down from his penthouse, puts on his bubba cap, and yes, he sounds as if he’s someone who could work on the docks, the fact that he refuses to ever be polite – which as we know, in terms of the old measure of social breeding, politeness was the most important marker of class status.

Early on he was seen as cornering the white trash vote, his rabble rousing and race-baiting was inciting the revenge of the lower classes. But the problem with that is that someone like Nate Silver has argued that Trump’s voters are wealthier than either Clinton’s or Sanders’s constituencies. So we have two things going on. The visual images of the rallies and the racial tension, which I wrote about for Salon, harkens back to people like [early 20th century Mississippi Governor] James Vardaman, who engaged in this kind of race-baiting, who pitted poor whites against blacks. And he has tapped into class fears and anxieties, particularly in his emphasis on global grade. I think his wall, his famous wall which will never be built, what it really represents is not only the fear of poor immigrants from Mexico and south American coming into the country and creating job competition and lowering the wages of typical Americans, but it’s also a metaphor for keeping jobs in this country, there’s a certain isolationism that’s very appealing to voters who are attracted to Donald Trump.

One thing I’ve always been curious about was that, while there have always been poor white people in every part of this country, at some point the idea of poor whites, of “poor white trash,” became a Southern thing. How did that happen? And why, now, do so many who reclaim that identity – no matter where they live – look to the South, to the confederate flag for instance, as a symbol of their heritage?

You’re right. One of the things I’m trying to emphasize is that poor white trash comes out of the rural notion of talking about the poor. There are differences when we deal with the urban poor as opposed to the rural poor. We have to remember that rural poverty isn’t just restricted to the South, but the reason it becomes identified with the South has more to do with politics. I talk about the importance of the sectional controversy in the middle of the 19th century, the rise of Abraham Lincoln’s Republican Party. The made the argument of free soil, and it goes back to James Oglethorpe, the founder of Georgia, that when you have a slave society where slave owners become the most powerful class, they monopolize the land, and that hurts the ability of poor whites to experience social mobility. That idea starts with Oglethorpe, it’s repeated by Ben Franklin and Thomas Jefferson, and then it reemerges as part of the Free Soil party and the Republican Party. And what they argue is that slavery’s not only wrong because it oppresses slaves, but it undermines the ability of poor white men to achieve economic independence and also to achieve social mobility.

It’s actually ironic that working class men would want to embrace the confederacy, because one of the things I highlight about the confederacy is that it very much relied on reinforcing a racial and a class hierarchy, and this is a hangover from the antebellum period. The planter elite saw themselves as very much to the manor born. They assumed that they were the class that should exercise political power and rule. They began to defend the idea that a born to rule elite should control southern states, and particularly South Carolina, and they are very dismissive of poor whites. Not only was it reinforced during the confederacy, it existed before the confederacy.

So the confederacy is one of the most elitist political systems that we’ve had in this country. To assume that somehow the confederacy embraced poor whites, it even goes against the history of how the conscription laws worked. As we know the poor always suffer the worst during wars: they lose their land, they’re the ones who are put on the front lines, and you have high numbers of poor whites who desert from the confederacy because they don’t think it’s fighting for their interests.

So if it’s 1861 and you’re a poor white person, you’re going to be very wary of the confederacy, because they’re trying to recruit you to this war because you’re going to be cannon fodder. But if it’s 1961 and you’re a poor white, you might fly the confederate flag because you’re so threatened by the civil rights movement.

Again, it goes back to the fact that most Americans don’t know their history. Or the history they’ve been told has been grossly distorted. When writing about the civil rights movement, I focus a lot on Little Rock, Arkansas, and Governor Orval Faubus. First of all, he’s attacked as a hillbilly and seen as poor white trash. But he’s more than willing to fan the flames of race and class tension. And he can do that in Little Rock, because part of what we often miss from that history is that there were three high schools in Little Rock. There was the elite white school called Cadillac High, which was not integrated, and then there was an all-black school, and then there was a poor working-class high school, Central High School, which was the one that was chosen for desegregation. And he exploited that. On the verge of the first day of school, he claimed that poor whites were going to come from around the state of Arkansas, and they’re going to come in droves, and we’re going to have a race war.

And it also goes back to the confederacy, because when the confederate elites began to feel threatened by mass desertions,there was even talk of taking the vote away from some of the poor whites who were allowed to vote. But they decided we’d better not do that because then they won’t fight in the war. But at the same time they start trying to come up with a rationale to convince poor whites to fight for the confederacy, and the argument that they make is that poor whites don’t fight for the confederacy they’re going to lose out on their end, they’re going to drop down to the level of free blacks or slaves. And again, there’s this idea of pitting these two groups against each other, but it also completely contradicted the way the south and the Southern elite really felt about poor whites. Because in the antebellum period they felt their slaves were more valuable than poor white, because slaves at least contributed to the economy.

So we have to realize that first of all poor whites are not always the enemies of black Americans. Because at times they lived next to each other, they socialized with each other. But it’s a very, very effective tool for politicians when they feel the elite is threatened to focus on pitting those on the lower ranks of society against each other. And this has been used again and again. Why do you have all these negative terms for the poor, why do these ideas persist? Because to project hated onto the lower classes is a very effective way to transfer the problem, to blame the poor. Not only do you say they’re lazy and deserve their fate, it makes everyone else less accountable. It’s so fascinating how these ideas go all the way back to the 18th century.

For example, in 1790 John Adams argued that Americans not only scrambled to get ahead but they needed someone to disparage. “There must be one,” he wrote, “indeed, who is the last and lowest of the human species.” His argument is exactly what Lyndon Johnson said, when he talked about the racism of poor whites: “If you can convince the lowest white men he’s better than the best colored man, he won’t notice you’re picking his pocket. Hell, give him somebody to look down on, and he’ll empty his pockets for you.”

People will tolerate having people above them, they’ll defer to an elite class, just as long as they have someone beneath them. We forget the psychological power of that. Americans like the rhetoric of equality but they don’t like it when it’s real, and they don’t really defend it when it comes to how can we create an equal society. When it’s so easy to dismiss different groups, usually in very shallow ways, just as a way for us who are of the middle class to feel that somehow we deserve what we have. We always want to mask it, we always want to rationalize it, but it’s been with us and it’s still with us. Not only are we not a post-racial society, we are certainly not a post-class society.

Before Tony Soprano, there was “Seinfeld”: “It turns out we love nothing more than terrible people, but at that time it was unheard of”

Jerry Seinfeld and Jason Alexander in "Seinfeld" (Credit: NBC)

It went from unlikely and invisible to being one of the most written about – and for a while, overhyped – television shows in history. But now, almost two full decades after its final season, we have enough distance to assess “Seinfeld.” Jennifer Keishin Armstrong’s new book “Seinfeldia: How a Show About Nothing Changed Everything” takes a detailed look at the making of the show, as well as the afterlife of its actors and fans.

“Seinfeldia” examines how the comic energy between Jerry Seinfeld and Larry David led to them scripting a show they dreamed up as a TV version of Samuel Beckett: Seinfeld described it as “Two guys talking.” In some ways, the show never changed – even if it became four people talking – but it also ended up subverting a number of television traditions during its nine seasons.

Salon spoke to Armstrong, a former Entertainment Weekly staffer who has also written a book about “The Mary Tyler Moore Show,” from New York. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

It’s funny looking back: “Seinfeld” is hugely popular, hugely influential. But when it started out, people were kind of worried that it would even survive at all, not just its creators but people at the network. What were they worried about and how long did they worry about it?

If you go back and watch the pilot episode, with no disrespect meant, I think you can see what they were worried about. It’s a little… It’s not all there yet. It’s funny, but it’s a lot quieter, the characters aren’t fully developed yet. And it doesn’t really seem like it has that specific point of view that we came to know as “Seinfeld.” It really was what they pitched, which is, you know, they said it’s two guys talking. It’s a lot more “two guys talking” and not a lot else. So, that’s the thing they were worried about.

But they liked Jerry Seinfeld, they knew that, that’s why they signed him. They felt like it was funny, they felt there was something there. If you go back and look at the show dates, it’s like there was one episode the first year [“The Seinfeld Chronicles,” as the pilot was called, was released in 1989, almost a year before the next episode would air as “Seinfeld”], four episodes the second year, 12 the third. They were very cautious. So they were worried for some time in that sense. They were hedging their bets. They made the first season, and put them out in the middle of the summer to see how it went.

Specifically, your book says that they were worried it was too New York Jewish, right?

Yes, yes, exactly. It does have that. If there is a sensibility it has, it is, for lack of a better way of saying it, it is very specifically New York Jewish guys kind of talking about their neuroses. There’s a lot of Woody Allen feel to the early ones especially, to the point that Jason Alexander said he auditioned as Woody Allen because he didn’t know what else to do. So that was what they were worried about, but it turns out, at least as the show developed, it really transcended [that]. I think that the more specific you are as a character and setting, as long as you’re doing a good job, the more universal it ends up feeling because it feels real. And I think that’s what came through to people.

The famous line about the show is one that you use in your subtitle — that it was “a show about nothing.” Where did that term come from and was it fair?

So that is from one of my favorite parts of the show, which is the arc when Jerry and George pitch a sitcom within a sitcom that is quite clearly, “Seinfeld.” But it’s called “Jerry,” and they pitch it to NBC, and they kind of use a lot of their own origin story in this plot. And “the show about nothing” really comes from what it is essentially a pithy, cleaned up, more zingy version of their original pitch, which was “two guys talking.” “Two guys talking” isn’t as funny to say.

But they came up with this idea that it was a show about nothing, it was about just your daily life. By all accounts of the people I talked to, it seemed like there were some regrets on this side of the show, that that phrase stuck so much. But you never know, and that really does sum up the show in one way. It’s what made it different. I mean, it did get a little wacky, but it wasn’t like “I Love Lucy” where they put her in these extraordinary situations that would never happen. It was about the irritations of everyday life. And that’s really what they meant by that.

That said, I think the reason a lot of people didn’t like the catchphrase is that they tackled a lot of issues. It was about real life, it was inspired almost exclusively by things that had happened to the writers, and so it doesn’t feel like nothing to [them]. That’s the whole point of the show, that it blows up these tiny things to be these epic storylines because that’s how they feel to us when they happen to us.

You describe the writing and the craft that went into every episode. I guess each episode was about 22 minutes if you take the commercials out, and it seems like the process was incredibly rigorous. Was there something different about the way the show was put together that made it successful, in other words, beside the fact that you had good actors and smart people writing it? Was there something else that contributed to it becoming the biggest comedy of the last quarter-century?

It had a really weird writing process that I don’t know if any other show had. They didn’t have a writers’ room where everybody would get together and bounce things off each other. A writer would have to get four different storylines, one for each character, approved first. You’d have to catch Larry and Jerry, pitch them, and get then approved. Then you have a storyline, and you have to map them together. Then you have to bring them together at the end, which was kind of their signature thing.

Larry and Jerry would take your first storyline and smoosh is down: You had what you thought was 22 minutes of material, and they say, “This should all take place in the first third. Now go figure out the rest of the show.” That meant it was super densely packed with stuff. It moved and moved and moved.

Where do you see the influences of “Seinfeld” these days in shows that are popular? In the age of “Game of Thrones,” is “Seinfeld” still relevant?

I love thinking about it, especially shows like that next to each other. They’re both television. That’s weird.

Right, they really do seem like totally different art forms.

Yeah. “Seinfeld” wasn’t the first to do this, but it’s among the best, and it really elevated the form of television. Period. Larry David said, “I think this can be an art form. Not just stupid, throwaway trash.” So that’s the first part; he wanted to do something really smart and he proved that smart was mainstream, and that was a hard thing that NBC was resisting. They never liked to say it that way. It happened back in the ’70s too. They never have faith in America. America likes to feel smart, and this show helped do that and helped usher in an era where everything is trying to be smart, and art, almost to an exhausting degree.

So there’s that, and there’s also things like the antihero, which is a mainstay of our TV right now. It turns out we love nothing more than terrible people, but at that time it was unheard of. And this is four terrible people; let’s keep it real, you know?

They’re sympathetic in some ways but they’re sort of selfish and unpleasant as well.

Right. Tony Soprano gets most of the credit, but they proved it first that America is fine with that. In fact, they showed why it’s fun to have unlikeable characters: it’s because they can do things that you wouldn’t do. That’s why we like Tony Soprano, but that’s also why we like George Costanza.

I think there’s a self-consciousness to the show about TV and consumerism. Do you see that as well?

Yeah, for sure. I think in terms of the ’90s, it’s a real Gen X kind of show. We just loved that show. Even though it was made by Baby Boomers, it’s like the first that Gen X could sort of claim. That’s a very Gen X and ’90s approach, to have that super-conscious media-saturated feeling to it.

We were just talking about that arc where they make the show that is the show you’re watching. We see that constantly now — “30 Rock” — but at the time, that was another thing that wasn’t done as much. And now we’re so aware of television and how it works and we’re so proud of ourselves for being so smart, but this really did that first.

It also reminded me of another thing, which is that I think Larry David is among our first name-brand showrunners. People didn’t even know that word before. “Showrunner,” that’s a crazy word. The cool kids knew who Larry David was before “Curb Your Enthusiasm.” That’s something that’s now very common. We know who makes all of our shows, but that wasn’t as common back then.

Do you have favorite episode?

One of my favorites is a pretty early one called “The Jacket,” where Jerry’s jacket lining is pink and white stripes. There’s so many great things about this episode. It has the added bonus of having the only appearance of Elaine’s father. It’s true of all parents, when you get good parent characters — they kind of explain a lot.

And he has the added bonus of being based on the writer Richard Yates, too.

Yes, yes! That is the greatest part. He’s a cantankerous old author; what I love about it is the way it plays his masculinity against this new generation. “Why are you having a Coke? Real men drink Scotch!”

The right wing’s projection and obsession: Their hunger to pervert Black Lives Matter rises after Dallas

Joe Walsh (Credit: AP/Charles Rex Arbogast/Emily Schmall/Photo montage by Salon)

On Thursday, there were peaceful marches and vigils across the United States to protest the video-recorded killings of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, as well as the broader pattern of unwarranted violence and abuse by the country’s police officers against African-Americans and other people of color.

Unfortunately, one such march in Dallas descended into chaos and death when a sniper launched a coordinated attack on the police officers working the event. Five police officers were subsequently killed and seven wounded. Two members of the public, including Shetamia Taylor, who was hit while shielding her four children from the fusillade of bullets, were also wounded.

One of the suspected snipers, Micah Xavier Johnson, apparently told police that his motivations for committing this act of domestic terrorism were “to kill white people…especially cops.” Johnson would later be killed by a Dallas police department SWAT team.

The right-wing media, as well as other conservative opinion leaders, immediately pounced on the tragic events in Dallas. The images of police being fired upon by snipers, black and brown protesters, and a deep hostility to the Black Lives Matter movement are an intoxicating political cocktail that racially resentful, bigoted and authoritarian conservatives seem unable to resist.

For example, former United States congressman and right-wing radio show host Joe Walsh said via Twitter that:

“This is now war. Watch out Obama. Watch out black lives matter punks. Real America is coming after you,”

After deleting this message, Walsh continued with:

“I wasn’t calling for violence, against Obama or anyone. Obama’s words & BLM’s deeds have gotten cops killed. Time for us to defend our cops.”

The semiotics of Walsh’s missives is not complicated. The “us” and the “our” are thinly veiled references to white, right-wing Christians. The suggestion that America’s heavily armed and militarized police, a group rarely held accountable for their misdeeds, need “defending” begs the question, “from whom?”

Walsh’s efforts to link President Barack Obama and the Black Lives Matter movement to the violent actions of Micah Xavier Johnson and his confederates is delusional, unfounded, and a product of the right-wing conspiracy-paranoid imagination.

Right-wing propaganda site The Drudge Report announced that “Black Lives Kill.” The The New York Post echoed these sentiments with a front-page headline that read “Civil War.”

In all, these are none too subtle efforts to inspire fear and terror about a fictional “race war” by black people against White America and the excreta of white supremacist novels such as the infamous Turner Diaries repackaged as faux “journalism” and “analysis” by the right-wing chattering classes.

These responses by the right-wing media to the tragic events in Dallas are also acts of projection and obsession.

The obsession can be seen in how from (at least) the 1960s onward to the present moment of Donald Trump, movement conservatives have used the language of “black crime” and images of “urban riots” to scare the white “silent majority” in order to win elections.

Bill O’Reilly and other commentators at Fox News and elsewhere are obsessed with depicting the Black Lives Matter movement as “violent terrorists” who “hate the police,” are “anti-white,” and are also “un-American.”

They are also obsessed with the so-called “Ferguson Effect.”

These obsessions are based on lies and falsehoods.

Black Lives Matter is a multiracial and peaceful civil rights movement and network of activists and social change workers. It does not use or endorse violence.

There is no reliable, systematic evidence to support the existence of the “Ferguson Effect”; There is no “war” on America’s police.

White anxieties about an anti-white “race war” in America are an act of extreme psychological projection. Historically, it is not white people who should be afraid of African-Americans, but rather, African-Americans and other people of color who should be in terror of white folks.

Racial violence and terrorism in the United States has almost exclusively been waged by white people as a group against people of color. This pattern is part of the foundational character and history of a country that was born into existence by the genocide of First Nations peoples and the enslavement of blacks.

The Ku Klux Klan was and likely remains the largest terrorist group in American history. From the end of the Civil War through to Reconstruction and the 25 years that followed, it is estimated that the Ku Klux Klan and other white terrorists killed 50,000 black Americans across the South.

After World War I, white Americans participated in racial pogroms and other acts of mass violence against black Americans in cities such as Chicago, Tulsa, East Saint Louis, Washington, D.C., and Rosewood, Florida. This violence does not include the hundreds of black communities and neighborhoods that were subjected to white ethnic cleansing across the United States during the 19th and 20th centuries.

Almost 100 years later, blacks and other people of color remain much more likely to be the victims of racially motivated hate crimes than are whites.

To move forward after the Dallas shootings and the video-recorded killings of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile requires that the American people reject the lies and obsessions that are being spun out of whole cloth by a right-wing media that is more interested in ginning up racial animosity and violence for profits and attention than it is in acting responsibly.

White conservatives are quite fond of the slogan “All Lives Matter.” This slogan is fundamentally dishonest because it dismisses the unique perils and existential threats that black and brown people experience in the United States. But perhaps, “All Lives Matter” could be salvaged in service to the common good.

In the aftermath of the Dallas sniper attacks, and the police killings this week of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, “All Lives Matter” could be used to remind the general public that the lives of America’s police officers and its citizens should have equal weight and value. Anything less is unjust, anti-democratic, and will only further an immoral state of affairs where too many of America’s police treat people of color and members of other marginalized groups as second-class citizens in their own country.

Death in Dallas and America’s existential crisis: Our new “civil war” over the nature of reality

(Credit: Reuters/Rick Wilking)

After a week of shocking and polarizing violence in America, which featured two black citizens shot dead by police in ambiguous circumstances and ended with Thursday night’s sniper killings of five police officers in Dallas (apparently by a lone African-American gunman), we are badly in need of some perspective. Unfortunately, perspective is exactly what we lack in our broken-down republic, although you could just as well say that we’ve got too much of it. Different Americans, and different groups of Americans, perceive different realities, and can barely be said to inhabit the same country.

That fact lies at the heart of our deepening national crisis, which goes beyond political disagreement or racial conflict into existential or epistemological realms. There was nothing exceptional about this week’s body count, sadly, although the Dallas attacks unquestionably got the entire nation’s attention. But certain aspects of our current situation are new and striking. There was a certain grim hilarity to Donald Trump’s post-Dallas Facebook lament that “Our nation has become too divided,” which is roughly like Count Dracula complaining that all the pretty girls in Transylvania have become vampires. But you can’t argue with the sentiment. We are an intensely divided country — in terms of race, culture and ideology, of course, but also in terms of basic facts and how to understand them. This profound disconnection is not without precedent, because American history is full of echoes. History also teaches us that such division holds great danger.

There’s no neutral high ground that can offer you or me or anyone else some clear vision of this week’s tragic events, or the painful decades and centuries that led up to them. When you’re in the middle of a crisis about the fundamental nature of your country and where it’s going, nobody gets to stand outside it. Very likely no such view from above was ever possible, but in the days of Edward R. Murrow or Walter Cronkite we convinced ourselves it was. I recently had lunch with the legendary television producer Norman Lear, whose 1970s sitcoms sometimes attracted 50 million viewers or more. He told me he felt a responsibility to reach viewers who were nothing like him, and who disagreed with him about every possible issue. Lear’s most famous creation, Archie Bunker, was a racist, sexist and homophobic bigot, portrayed with immense compassion and complexity.

For better or worse, we have abandoned the notion of a shared mainstream culture and embraced a radical subjectivity worthy of 1980s critical theory. Experts and authority figures can be cast aside anytime we don’t like what they say; science is understood as a matter of opinion, and the difference between science and opinion is itself a matter of opinion. Some aspects of that iconoclasm have been healthy, like the realization that we have all been shaped by cultural forces we may not perceive, and that none of us is free of bias. But the technology that has connected us and made us so self-aware has also isolated us in electronic cocoons that magnify our existing prejudices and reflect them back at us. Archie Bunker minus the running arguments with Meathead, plus Fox News, leads to Donald Trump.

President Obama, who has had plenty of practice making somber speeches in the wake of national tragedies, did his best to play unifier-in-chief this week. He has long since learned it’s a lost cause. Both in his earlier remarks about the killings of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile and in his Friday morning comments after the Dallas attack, Obama sought to stress abstract principles that nearly everyone claims to believe in: Fairness and justice, along with the idea that there is no excuse for cold-blooded murder. As he knows all too well, there will be widely divergent views about what “fairness” and “justice” mean in practice in these cases. I couldn’t help thinking of the central theme of James McPherson’s magisterial Civil War history “Battle Cry of Freedom”: The Union and the Confederacy both believed they were fighting for freedom, but understood that word in radically different and mutually contradictory ways.

That’s why I wasn’t as horrified as some people were by the New York Post’s “CIVIL WAR” front-page headline after the Dallas shootings. In a bizarre and no doubt accidental fashion, it pointed at the truth. I don’t disagree that the phrase was reckless and irresponsible, or that it tried to stoke white fears that Dallas was the beginning of a race war rather than an isolated crime committed by a disturbed individual with a high-powered rifle. The Post has a long history of siding with New York cops even in the most egregious cases of abuse, and has devoted considerable energy to depicting Black Lives Matter and other protest movements as homegrown terrorists. (Years after the black and Latino young men known as the Central Park Five had their convictions in an infamous 1989 rape case thrown out, the paper occasionally recycles arguments that they were guilty after all.)

But without meaning to, the Post’s headline writers illuminated a crucial historical analogy: The last time our country was this badly divided, torn between incompatible visions of our nation’s core identity and future destiny, we wound up fighting the bloodiest war in our history, whose wounds have never entirely healed. (Even after all the carnage of the 20th century, approximately half of all Americans who have died in wars died in the Civil War.) I’m not suggesting that a second Civil War is likely to happen anytime soon, or at least not one that looks anything like the first one. It might be more accurate to say that we’ve been fighting it for the last 20 years, in the cultural sphere and the media and on the Internet, and that it’s beginning to leak into the physical world as well. If we understand the Civil War in the terms Lincoln used at Gettysburg — as an existential conflict that nearly destroyed the nation — well, we’re getting closer to that every day.

In his ascent to the presidency, Obama modeled himself on Lincoln a bit too obviously, and maybe he resembles the Great Emancipator in a way he never anticipated, as a central symbol and principal flashpoint of American division. It’s easy, and perhaps cathartic, to mock people who tell pollsters they’re still not quite convinced, after eight years of deadpan Oval Office cool, that Obama’s not a Muslim. (Or right-wing media figures who say that at any rate he likes Muslims too much.) But the novelty has pretty well worn off, and such suspicions point vividly at the fact that there is no mutually agreed-upon reality in America. This problem is definitely bigger than America; some British commentators have described the Brexit vote as an exercise in “post-factual politics,” an angry protest against the status quo that flies in the face of all available evidence. But our country exhibits an advanced form of the disease: We find ourselves, pretty much, in post-factual reality.

No doubt it’s overstating the case to say that America has a white reality and a black reality, which are mutually contradictory and rarely overlap, but it’s not overstating by much. Most whites perceive law enforcement as even-handed and fair-minded, and believe the unnecessary use of lethal force is a rare and unfortunate event. Law-abiding citizens, of whatever color, have nothing to fear from the cops, and those who suggest otherwise are stirring up trouble and apologizing for thugs. African-Americans, of almost any class or economic background, are alert to a long history of official racism and police brutality that may have altered its form and terminology but keeps recurring, year after year, in dozens or hundreds of cases that end with black bodies dead in the street. No matter how clear-headed I think I am about that divide, my lived reality is that I will never fear for my life if I get pulled over for a traffic infraction.

As we can see from the reactions to this week’s dreadful events on the competing news channels and social media, it’s not overstating the case at all to say that we have a “liberal” reality and a “conservative” reality. (I would argue that both words have been stripped of their original meanings and are virtually useless, but never mind.) In one version, the greatest nation in the world has come under sustained attack both at home and abroad, and its enemies — big-government socialists, the identity-politics thought police, Black Lives Matter, feminists and gays and Spanish-speaking immigrants and “radical Islam” and Barack Hussein Obama — share a common agenda and are quite likely working together. In another, evil corporations and embittered white racists have forged a nightmare coalition devoted to rolling back every progressive reform of the last 80 years and turning 21st-century America into a “Doctor Who”-style mashup of Victorian England, “Leave It to Beaver” and “The Handmaid’s Tale.”