Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 722

July 11, 2016

A frightening precedent: Can we talk about the Dallas police using a bomb robot to kill a man?

(Credit: AP/LM Otero)

The police shootings in Dallas last week were disturbing for a number of reasons. Most obviously, five officers lost their lives. Whatever your thoughts on police brutality or racism in the criminal justice system, there’s no justification for what happened. But last Thursday was also disturbing because of a dangerous precedent set by the Dallas Police Department. The lone gunman, Micah Xavier Johnson, was killed around 2:30 AM Friday morning after a protacted stand-off with the police. Trapped in the parking garage of a local college, Johnson negotiated for hours with the police, reportedly refusing to cooperate. Eventually, officers on the scene sent a robot into the garage and detonated an explosive device near the suspect, killing him instantly. “We saw no other option but to use our bomb robot,” said Dallas Police Chief David Brown. “Other options would have exposed our officers to grave danger.”

This was an extraordinary decision. It was the first time domestic police have used a lethal robot for the specific purpose of killing a suspect. As Seth Stoughton, a former cop and assistant professor of law at the University of South Carolina, told The Atlantic, “I’m not aware of officers using a remote-controlled device as a delivery mechanism for lethal force. This is sort of a new horizon for police technology. Robots have been around for a while, but using them to deliver lethal force raises some new issues.”

And those issues are fairly obvious. To begin with, this is a nation governed by laws, not men. And here an extra-judicial decision was made to kill a man. It’s easy to overlook this given the circumstances and the crimes, but this has to been seen in terms of the precedent it sets. Johnson was a clear threat, but he was also pinned down. There’s an enormous difference between killing a suspect while exchanging gunfire and methodically sending in a bot to execute him.

Johnson had a constitutional right to due process, no matter how despicable his crimes. If the police could have contained him or waited him out, we have to ask whether or not they had an obligation to do so. The use of deadly force absent the imminent threat of death is a violation of the constitution and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which the U.S. has ratified. The question thus becomes what constitutes an “imminent threat.” Here there is surely room for interpretation. But if Johnson was trapped in a garage and there were no civilians in the immediate area, that’s a difficult case to make. It’s not impossible, however.

Five officers had already been killed and several others were wounded. One can certainly argue an imminent threat existed, and as such the decision to use lethal force was justified, regardless of the method used. But the questions raised by this sort of technology remain. It’s not unlike the debate surrounding the use of drones against terror suspects. In both cases, these tools make killing remarkably easy. They also minimize the risks of police and soldiers while separating the killers from the killed. There’s both a spatial and moral distance here that makes it all the more urgent to discuss. When eliminating a suspect becomes risk-free, the temptations to act prematurely can be overwhelming. Which is precisely why this has to be thought through carefully. Technology has outpaced the law, and the events in Dallas are yet another reminder of this.

This incident also has to be viewed against the backdrop of police militarization in this country. Since the drug war exploded in the 1980s, police departments have assumed an increasingly militarized posture. Thanks to the “War on Terror” and the little-known National Defense Authorization Act, domestic police departments have used federal grants to procure surplus military equipment. (According to at least one report, that’s how the Dallas PD acquired the robot used to kill Johnson). Drones, tanks, bomb-resisting robots, and anti-ambush military vehicles have landed in the laps of local police, who’ve found ways to use use these weapons of war. Images of tear gas and cops in combat garb toting military-grade weapons on American streets has become commonplace. And unsurprisingly, with the rise in paramilitary tactics and military-style raids, incidents of excessive force and police brutality have spiked.

All of this has reshaped the culture of law enforcement. A warrior ethos has replaced a commitment to public service. It’s hard to overstate how dangerous that is. As Stoughton noted in his interview with The Atlantic, “The military has many missions, but at its core is about dominating and eliminating an enemy. Policing has a different mission: protecting the populace. That core mission, as difficult as it is to explain sometimes, includes protecting some people who do some bad things. It includes not using lethal force when it’s possible to not.”

It’s entirely possible (likely even) that the police did nothing wrong here. But we’ve clearly entered an ethical and legal gray area. Again, this isn’t about Johnson so much as the precedent his killing sets. I’ve no interest in defending him personally. This is about his rights as an American citizen and by extension the rights of all citizens. Agents of the state decided to kill a suspect on the scene without a trial and at a distance when perhaps other options were available. It’s easy to imagine a future scenario in which the threat is less clear and the decision more controversial. This is what we have to consider when discussing this issue.

A death-dealing robot is a weapon of war, not law enforcement. Placing it in the hands of cops and allowing them to determine on the spot when and how to use it is terrifying. It may be that the benefits of this technology exceed the risks, but that’s a conversation we’ve yet to have as a country. And even if that is the case, the public deserves to know the protocols and the chain of command. What are the parameters surrounding the use of killer bots? Who decides when they’re appropriate? If a teleoperated robot can be used to kill a suspect, can’t it also be used to neutralize him non-lethally? How do you determine which level of force is necessary?

These are questions that have to be asked, and the answers ought to concern liberals as much as conservatives. Anyone worried about state-sanctioned tyranny has reason to demand clarity here. Once more, the issue isn’t Micah Johnson. The issue is the erosion of due process and a nation in which domestic police are allowed to kill civilians remotely without judicial consent.

If there’s a slippier slope, I’ve yet to see it.

July 10, 2016

Not Quite “Brazil”: Meg Ryan, plastic surgery and my mother’s augmentation

Jim Broadbent and Katherine Helmond in "Brazil" (Credit: Universal Pictures)

In the movie “Brazil,” the main character’s mother purchases repeated plastic surgery until she becomes something grotesque, a symbol of our vanity gone monstrous and absurd.

In the celebrity world, plastic surgery is alive and well, as is the criticism flung toward those who use it. Meg Ryan’s recent “new look” has garnered a vitriolic critique on social media. Having never been anyone whose face would was the subject of social media, I can only assume that there is intense pressure in Hollywood to appear youthful. It’s true that we have a culture that puts enormous pressure on women to look young, and to have bodies that curve in a specific way. And yet, our society judges us for giving in to that pressure.

In my younger days, I was vehemently against any kind of body alteration, feeling that it was giving into valuing the superficial. I had read Naomi Wolf’s “The Beauty Myth,” and resented spending any money in the beauty industry. I stopped shaving my legs in protest, and rarely bought makeup However, I colored my hair, wore earrings in my pierced ears, and shoved contact lenses into my eyes. It was during this contradictory time that my mother got breast implants. My mother had been a flower child who hitchhiked across Europe, but that was years ago and she was in a different world now. One that involved a new husband, evenings out, and a new set of jugs. My siblings and I liked her new husband, Marv, although he was unlike anyone she’d dated before. For one thing, he had money. Something my mother had never had. And he had a terrible hairpiece, but we thought we could look past that.

My mother and I are both small breasted women, which has its challenges. Stylish shirts gap in the wrong places. Low cut sexy dresses hang loose. I have spent a fair amount of money on push up bras, “Miracle” bras, and inserts to shove into my bra to fill out certain styles. I don’t get to wear low cut shirts to show off my sexy cleavage, because isn’t any to show. This had bothered my mother her whole life. She took part of her savings, combined it with some of her husband’s money and bought herself implants. My sisters and I figured she paid for one boob and Marv paid for the other.

I drove the four hours to stay with her and help her recuperate from the surgery while Marv was at work. She was sick, weak and in pain, her skin stretched mercilessly over her implants. I felt helpless trying to take her pain away, bringing her Jell-O, hot tea, a Percocet. I brought her icepacks which she held delicately over her swollen and disfigured chest. It was hard to imagine it looking normal, ever. At her follow up appointment with the surgeon, I glared at him with disgust. He didn’t wear a doctor’s coat, but a slick suit jacket. I loathed his tan skin. He reached his two hands out casually and forcefully adjusted my mother’s new breasts, causing her suck in her breath and stumble into me. On the way home I pulled over so she could vomit. I couldn’t figure out why she should do this to herself.

A few weeks after my mom’s surgery, my sisters and brother and I got together at my mom’s for the 4th of July. My brother and I rolled our eyes at my mom’s low cut shirt and booty shorts. When she and Marv walked out to the pool together he whispered, “Here come Rugs and Jugs.” Mom gathered my sisters and I up and dragged us into the bathroom where she flung off her shirt to show us her new tatas.

“What do you think?” she asked while I ducked my head to avert my eyes from my mother’s giant breasts.

“Do you think one is larger than the other?” she asked anxiously.

“Geez, Mom” said one sister. “When you do something, you go all out.”

I wasn’t interested in comparing sizes. I tried to make my way to the door, but it was too crowded to move in the bathroom. I glanced in the mirror and my mother’s breasts were looming.

“Oh, and while I’m thinking of it,” she said. “I can’t ever be cremated.”

“What?”

“Don’t cremate me. My boobs will explode.”

“Okay mom, got it.” I said. “Now, can I get out of here please?”

“I think Marv’s boob is bigger,” announced a second sister.

Later that night, while we were drinking wine out by the patio, my sister asked me how I was doing. I was confused.

“I was just worried that you might be feeling insecure about your own body, since Mom got her new boobs. I mean . . .” she stumbled awkwardly and then smiled at me over her own ample rack. “You’re boobs are just fine on you. You know you don’t need to get anything bigger.”

“I’m good,” I said. “Mom is insane, you know that.” Although for the first time, I did suddenly feel like my breasts had been insulted.

I mostly like the convenience of small breasts and when I need a push up bra, I just put one on. However, I do wax my eyebrows and upper lip, which hurts like hell and leaves my skin red and puffy for hours. I have spent precious time and money at the salon to color my hair. I don’t judge my mother as I once did, for changing her body. It’s been years since my mother’s implants. She doesn’t regret them, although she did stop wearing booty shorts and crop tops, thank god. I may not have understood her decision, but at the core of the issue is that it’s my mother’s body. What she chooses to do with it is her prerogative. Although she does still feel that one boob is bigger than the other. I still haven’t looked that closely.

Although the drive to remain youthful in Hollywood is frequently blamed for actors’ choices for to go under the knife, Meg Ryan’s “new look” doesn’t appear to be about looking youthful. Her face, in my opinion, doesn’t look younger or appear as though she’s trying to look like she’s 25, it’s just different. It’s as if she’d gotten tired of long hair and given herself a shag cut. Regardless of the motivation, the question remains – why do we care? Do we care because we love the face of “Sleepless in Seattle” or “When Harry Met Sally”? Have we so absorbed these movies into our consciousness that we feel we own the actor in some way? Somehow, we feel that her face belongs to us in some way, and Ryan’s choice to alter it feels to us as though she’s taken something from us. When my mother bought herself some new breasts, it felt a little like the hippie mother who took me to Renaissance festivals and sold ceramics was gone. But my mother’s body belongs to me no more than Meg Ryan’s face. So, let’s pass on the judgment. Get the boobs. Rip out the hair. Botox the lips. Or don’t. Whatever. Frankly, we should all have more important things to think about.

Naomi Ulsted is a fiction and memoir writer from Portland, Oregon where she also directs an educational training program for at-risk youth.

There will be another Trump: His views alienate some, but the ideas behind them represent every American’s worst fears

FILE - In this June 1, 2016, file photo, Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump wears his "Make America Great Again" hat at a rally in Sacramento, Calif. Trump’s “Make America Great Again” hats proudly tout they are “Made in USA.” Not necessarily always the case, an Associated Press review found. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong, File)

This piece originally appeared on BillMoyers.com.

June was not kind to Donald Trump. After a brief bump in the polls when he secured the status of presumptive nominee, The Donald’s numbers began their march to the basement. He now finds himself in a deeply unenviable position. An increasing number of pundits (and, judging by the numbers of them avoiding the upcoming party convention in Cleveland, politicians) are suggesting Trump’s candidacy could be a disaster on par with Republican Barry Goldwater’s landslide defeat in 1964 or Democrat George McGovern’s in 1972.

Writing off Trump might be presumptuous at this point, especially since the media and other experts missed almost every salient facet of Trump’s seemingly improbable rise. Yet even if his campaign encounters electoral bankruptcy in November, the specter of another Trumpian figure emerging in the future remains highly probable.

Consider the numbers: Between 1928 and 1979, the top 1 percent’s economic share declined in every single state, and between 1979 and 2007, the share of income going to the top earners increased in every state. In 19 states the top 1 percent of earners took in at least half of the total growth in income. The consequences of the 2007-08 financial crisis further exacerbated the situation: Between 2007 and 2010, median family income declined by almost 8 percent in real terms. Median net worth fell by almost 40 percent.

Yet with the stock market rebounding nicely (at least, until the Brexit) and unemployment seemingly on the decline, politicos saw nothing to disrupt a predictable genteel war between the Clinton and Bush dynasties — instead, the face behind “The Apprentice,” a businessman seemingly straight out of the Gordon Gekko era of the 1980s, emerged to trounce one of the largest fields of candidates in recent GOP history. He’s now the second-most likely person to become our next president. And while (not undeservedly) a large measure of reporting fixates on Trump’s wild remarks and nativist proposals, the economic dynamics that led to Trump’s candidacy are under-appreciated.

As Trump expertly demolished the GOP field, a coterie of the conservative establishment rushed to denigrate not just The Donald’s quixotic quest, but also his base (Kevin Williamson of National Review singled out) — a large chunk of the white electorate.

“The white middle class may like the idea of Trump as a giant pulsing humanoid middle finger held up in the face of the Cathedral, they may sing hymns to Trump the destroyer and whisper darkly about ‘globalists’ and — odious, stupid term — ‘the Establishment,’ but nobody did this to them,” Williamson wrote. “They failed themselves.”

Did they? Or did the people for whom they voted fail them? Starting with Ronald Reagan and continuing through the administrations of Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, recent presidents of both political parties arguably have championed America’s globalizing business interests over those of its workers.

While the recovery passes up wide swaths of America, the professional class of the Democratic Party looks to the stock market and to the select parts of the country where life is good and incomes are on the rise. For evidence, we need only to look to President Obama’s reassuring (albeit also self-serving) remark in his final State of the Union address: “Let me start with the economy, and a basic fact: The United States of America, right now, has the strongest, most durable economy in the world … anyone claiming that America’s economy is in decline is peddling fiction.”

The fact is that for Trump’s voters — and perhaps voters who have yet to decide how they will cast their ballots — that worldview is not fiction at all.

While the American economy is indeed a relative bastion of stability compared with much of the world, a large portion of the population is experiencing a marked reversal of fortune. This is true both in the United States where labor, a traditional part of the Democratic base, is on the decline, and also throughout Europe, especially in places such as the Rust Belt towns of Great Britain that voted for “Brexit.” As economist Branko Milanovic points out, “For simplicity, these people may be called ‘the lower middle class of the rich world.’ And they are certainly not the winners of globalization.”

Thomas Frank’s poignant analysis captures the class divide for the Democrats: “Inequality is the reason that some people find such incredible significance in the ceiling height of an entrance foyer, or the hop content of a beer, while other people will never believe in anything again.”

That kind of despondency has fueled Trump’s apocalyptic populism. And despite his many repugnant policy positions, he’s hit the pulse of a large portion of America that is aware, quite correctly, that the middle class is fading — the real growing middle classes are in Asia today. When Trump says he’ll turn the GOP into a “worker’s party” and that NAFTA will be ended or renegotiated, economically left-behind workers in many states listen.

Trump’s voters can be found in regions of the country almost entirely bypassed by the post-Great Recession recovery. This covers a lot of territory: Between 2010 and 2014, almost 60 percent of counties witnessed more businesses closing than opening. That contrasts sharply with the period following the recession of 1990-91, when only 17 percent of counties continued to see declines in business establishments. In the aftermath of the Great Recession, a mere 20 counties produced half of the growth in new businesses.

The real danger is that the Democrats will win a runaway victory in November and fail to heed any of the lessons behind Trump’s rise. With Clinton’s campaign actively wooing disaffected Republicans, chances are considerable that the populist strands of both Trump and Bernie Sanders’s campaigns will receive little lip service. “If Hillary Clinton goes for the Republican support,” remarked longtime journalist Robert Scheer, “she will not be better. And then four years from now what Trump represents will be stronger.” Paul Ryan’s doubling down on austerity politics — the same ones thoroughly rejected by Republican voters in the primaries — will add fuel to the fire.

With the recent decision by Great Britain to leave the European Union, it seems that reactionary populism in the West has won a major victory — it should perhaps come as no surprise. A recent study by the Center for Economic Policy Research found that far-right parties gain the most politically in the wake of major financial crises. While the research focuses on Europe, it’s clear that the mix of populism and nativism brewing there is echoed by Trump here. And even if he loses in November, without a major change from both parties, someone else will tap into the vein of anger and discontentment that he’s so expertly mined.

The fight is far from over: Pro-choice advocates now must battle the mushrooming lies spread by media

(Credit: AP/Patsy Lynch)

It’s been nearly two weeks now since pro-choice advocates celebrated a decisive victory in the Supreme Court, when the 5-3 decision in Whole Women’s Health vs. Hellerstedt struck down both provisions of Texas’s House Bill 2 (HB2), one of many TRAP (Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers) laws that have swept the nation in the last five years. If left standing, HB2 would have closed the majority of abortion clinics in Texas, as it required abortion providers to have admitting privileges in a hospital no more than 30 miles away, and for abortions to only be performed in ambulatory surgical centers. Both of these requirements are not only

Both of these requirements are not only unnecessary for patient wellbeing, but also almost impossible for abortion providers to comply with, due to the expense of their implementation. And even worse, both provisions of the law were disguised as concerns for women’s health, but only served to advance an anti-abortion agenda. Pro-choice advocates rejoiced on June 27th because the Supreme Court recognized HB2’s false pretenses and put a stop to them, not just in this case, but in all similar cases to come.

In his opinion on behalf of the majority, Justice Stephen Breyer stated that, “neither of these provisions offers medical benefits sufficient to justify the burdens upon access that each imposes. Each places a substantial obstacle in the path of women seeking a previability abortion, each constitutes an undue burden on abortion access, and each violates the Federal Constitution.” Breyer’s words establish a precedent that any law that prevents abortion access under the guise of protecting women’s health is unconstitutional. Pro-choice advocates could not ask for a better outcome in this case, but what comes next? One thing is clear: the fight for reproductive rights for all women in America is far from over.

According to the Guttmacher Institute, there have been 107 TRAP laws passed in various states in 2016 alone and “from 2011 through 2015, states added, on average, 57 new [abortion] restrictions per year.” So HB2 is clearly one of many “undue burdens” on women’s reproductive rights. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s concurrent opinion in Whole Women’s Health vs. Hellerstedt attacked TRAP laws with her scathing dismissal of the proponents of HB2: “In truth, ‘complications from an abortion are both rare and rarely dangerous…Given those realities, it is beyond rational belief that HB 2 could genuinely protect the health of women, and certain that the law ‘would simply make it more difficult for them to obtain abortions.’”

Ginsburg makes it clear that HB2 was passed specifically to decrease abortion access, not to protect women’s health, as it claimed, and this combined with Justice Breyer’s assertion that HB2 did nothing to protect women’s health sets an important precedent that will affect other state’s regulations on abortion providers. Hopefully, this precedent will give those who are challenging many other TRAP laws, in many other states, the legal upper hand they need to strike them down.

It also finally changes the playing field: for the first time in decades, anti-abortion groups must play defense, as this case’s precedent throws dozens of similar state regulations on abortion into question. Since 1992’s Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey ruling set the precedent that abortion restrictions are okay as long as they don’t impose an “undue burden” on abortion access, anti-abortion advocates have used that as a justification for ever-increasing and increasingly outrageous abortion regulations. Whole Women’s Health vs. Hellerstedt finally clarified the meaning of an “undue burden” upon abortion access, destroying the anti-abortion campaign’s argument in the process, and giving pro-choice advocates a clear advantage in similar court cases to come.

With that in mind, the precedent this case sets is obviously huge, and its implications are already being seen: in the two weeks that have passed since HB2 was struck down, Alabama’s Attorney General ended an appeal to enforce an admitting privileges law very similar to HB2; the Supreme Court denied Mississippi and Wisconsin’s appeals to restore their also very similar admitting privileges laws; the Center for Reproductive Rights filed a lawsuit challenging seven (again, also similar…see a pattern here?) abortion regulations in Louisiana; Planned Parenthood has launched a campaign to take on similar laws in Arizona, Florida, Michigan, Missouri, Pennsylvania, Tennessee and Virginia; and a particularly outrageous set of abortion restrictions that would have banned all abortions of fetus’s with a disability or genetic abnormality in Indiana were blocked, and other restrictions in Indiana, including an ultrasound requirement for all abortions, are being challenged. If we can accomplish all this in just two weeks, then the legal tide must be turning. But the fight to turn the tide of public opinion is still vital and ongoing, as long-ago debunked myths about abortion are still accepted by many as facts, and the Supreme Court’s decision in Whole Women’s Health vs. Hellerstedt won’t change that overnight. Why are there still so many people who think abortion providers sell fetal tissue or that birth control can cause an abortion?

Part of the reason for widespread misinformation about abortion can be blamed on its media coverage, that too often presents myths as facts. Since 2011, there has been an unprecedented attack on abortion access from numerous TRAP laws, and public outrage has been stymied by the mass outpouring of inaccurate information about abortions. The religious right’s campaign against abortion access has been unfairly supported by the mainstream news media, who are supposed to provide the public with factual, unbiased information, but instead, have been consistently providing us with just the opposite. A Media Matters study of evening and prime-time news (on Fox News, CNN, and MSBNC) over a 14 month time period found that due to the dominance of anti-abortion speakers on mainstream news broadcasts, there has been more inaccurate information spread about abortions than ever before.

For example, Media Matters found that 70% of appearances on Fox News (including hosts, guests, etc.) identified as anti-choice or made anti-choice statements; out of all appearances on MSNBC, Fox News, and CNN, 40% identified as anti-choice, 62% were male, and only 17% of all appearances on all three networks identified as pro-choice. Even more shocking is this finding: “705 statements containing inaccurate abortion-related information aired on Fox News,” whereas only 158 statements on Fox News contained accurate information. Essentially, the news coverage on abortion props up TRAP laws by spreading inaccurate information about abortion-related issues. How can we hope to remove the unfair stigma attached to abortion if the public isn’t even given the correct information?

You wouldn’t know it from the biased media coverage, but public opinion on abortion has changed significantly over the years. A recent Bloomberg Politics national poll that found that 67% of Americans agreed with a woman’s right to choose and with the 1973 Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade, and in a VOX/PerryUndem poll, 70% of respondents believed that more Americans identified as pro-choice than pro-life. But still, the mainstream news media is telling a different, inaccurate story. As we move forward, pro-choice advocates need to be mindful of this media bias and the problems it creates. 1 in 3 women have abortions, and the time has come to end the stigma of the procedure.

The only way to truly protect women’s reproductive health rights is to end abortion stigma by changing the popular narrative about abortion, and the only way to do that is to ensure that news outlets provide factual information to the public. Until the general public has consistent access to accurate information about abortion, then how can we truly have widespread access to abortion rights? The pro-choice movement should now focus its efforts not only on repealing TRAP laws in other states, as it has already begun to do, but also on changing the narrative about abortion, and that starts with holding the mainstream media accountable for their biased, inaccurate coverage.

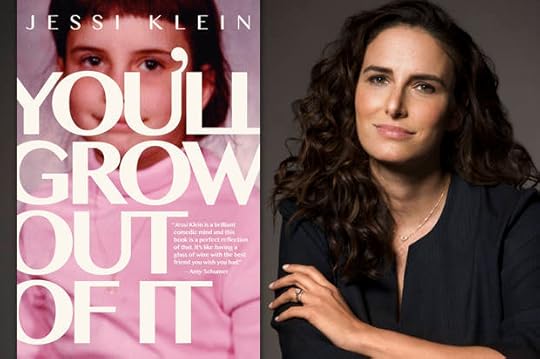

Jessi Klein really wants you to get the epidural: “There’s pressure on all women that’s absurd”

Jessi Klein (Credit: Robyn Von Swank)

Jessi Klein is your imaginary BFF. She’s the Emmy and Peabody Award-winning head writer for “Inside Amy Schumer,” and has in other incarnations been a standup comic and a writer for “Saturday Night Live.” She is beautiful and successful. She’s also a woman who can — and does, in her funny, brutally honest first book, “You’ll Grow Out Of It” — admit to feeling like “dogshit” on a red carpet and to thinking about Gwyneth Paltrow “all the time and sometimes… right before I go to sleep,” and devote an entire chapter of her work to multiple entreaties to “Get the Epidural” because, as she explains, “No one ever asks a man if he’s having a ‘natural root canal.'” She is smart and eminently grownup and so refreshingly devoid of BS it’s hard not to feel hungry when you get to the last page of her book (due out Tuesday).

Fortunately, she spoke to Salon via phone recently and gave us a little more of her wisdom, humor, and solid advice about getting the epidural.

Why did you decide to write a book? What drew you to memoir?

Part of it was that I didn’t think I was writing a memoir. I see why people look at it that way, but in my head that’s not what I was writing. I was like, “Oh, i’m just going to write these funny essays and some of them are about me, and some of them are more observational,” but I didn’t feel like I was sitting down to do an accounting of my entire life. If you were to ask me today, “Do you want to write a memoir?” I would say no.

And yet there’s a lot of really intense, intimate stuff in there about dirtbags you dated and trying to get pregnant and other really personal things.

My very honest answer is that it was a combination of trying to sort things out for myself, but also that maybe I can make other people who are going through something similar feel less alone.

There is an entire culture in dealing with infertility issues. I spent a relatively short time in it, because people spend years and years in it. But it was painful in many ways, and at times funny, and at times embarrassing. There are so many forums and books and Web sites where people are sharing the pain they’re in and everyone’s kind of looking for reassurance — and that is all good. But I never found anyone talking in a tone of voice that I totally related to. Even though I felt deeply upset and deeply sad, I still wanted to laugh at it. And I was of two minds about having a kid. I didn’t sense from anyone else that there was a permission to think, “Well, I guess if I didn’t have a biological kid, it’d be okay.” Maybe I felt that way and maybe other people don’t feel that way. I just missed humor in dealing with it. At the same time, I had many days I felt totally humorless about it. I don’t mean to be judgmental of anyone going through that. It’s horrible. And the secret of the Internet is that very few people come back to tell the good news. So I always heard the saddest stories.

One thing I really hated the most when I was going though it was that lots of people would say, “Don’t worry, it’ll happen.” I was like, actually, I don’t know it’ll happen. I personally know lots of people for whom it never happened, despite trying things I never even had to go through. I felt like what would make me feel really better was for someone to just be comforting and be with me in the discomfort.

You don’t need someone to fix it. You don’t need someone to make it okay. You need someone to just be say, “Wow, that sounds really hard.” So how did you balance writing about those hard things in your with other parts about how much you love Anthropologie?

I do love Anthropologie. I make my living writing comedic things but my personal sensibility — a lot of what I consume in terms of TV and books is stuff that’s actually pretty dramatic. I enjoy things most when they’re both, because I feel both all the time. I’m able to do what I do in part because I grew up with a sense of humor being a coping mechanism through which I see the world. I’m also coping with feelings that are pretty dark. It’s about making people feel understood and less alone. The things we’re most scared of being alone with are sadness or isolation of some kind, and it’s important to know that other people are feeling it too.

Right — sometimes you go on social media or look at your friends’ Facebook pages and you feel like everybody else is crushing it. You get this distorted sense that everybody else is having this amazing experience in life and you’re the only one struggling with heartbreak or frustration. That’s why I wanted to ask you about the “Dogshit” chapter.

That’s one of my favorite chapters in the book. I’m 40. I’m old enough to know that when you talk to anyone that everyone’s pretty miserable. There are wakeup moments that you have as you go through adulthood where you realize you never know what’s going on. But I feel bad for people who are growing up on social media, where it’s this constant bullshit parade of images.

Speaking of growing up, my favorite three words in the whole book are, “Get the epidural.”

Yay! If there is one thing that comes out of this book that I want to have a life outside, it’s for that chapter to be dispersed. And I know it’ll make so many people angry and I think that’s, for me, good.

This cult of competitive motherhood is really bad.

I hope that this is the flip side of the Internet’s “Everything is amazing.” I do feel like there is a movement of private groups where moms are really sharing, “Oh, it’s a shit-show.” People are really open, and it’s great when they’re open about how hard it is. People just go on at 2 in the morning and they’re like, “I’m really struggling.” I really struggled, and I still really struggle.

I also feel lucky because I’m in a culture where I’m friendly with a lot of people who share similar views on how much bullshit there is around competitive motherhood. But I recognize that’s probably not most people’s experience. There’s pressure on all women that’s absurd.

It’s like what you talk about in the book about Anthropologie. I want to live in Anthropologie, but my life is like Sears.

I don’t relate to a lack of vulnerability. I probably felt differently about it at one point in my life and now I feel pretty fiercely committed to sharing all of those moments that are less than perfect. Perfection is always a lie.

Relatedly, no one has ever summed up how I feel about Gwyneth Paltrow better than you have.

She is at the center of everything we have been talking about. She’s a person and she is a human being who is infuriating but she’s clearly been though painful things in her life. I do think about her more than is sane. I wish I looked like her. I think she’s super beautiful. I think she’s a really good actress. But I do not know her. She does, as someone who’s been a GOOP reader from the beginning, seem like this woman does feel this really intense pressure to be perfect in a way that explodes your mind. I definitely have a lot of questions for her.

So what is your next adventure after this book?

I had a crazy year. I won’t say it was a bad year; there were things that were great and things that were bad, but it was really full on. In a weird way, the book is coming at a moment when some of the stuff is settling down. I kind of want to not know the next thing. I’m in the stage where I just want to lie around and dream a little bit. If I could just be carried around on the shoulders of the epidural crowd, I’ll have achieved everything I set out to do.

Sia doesn’t want to be famous: Considering how we treat women like Margot Robbie and Renée Zellweger, who can blame her?

Margot Robbie; Sia; Renee Zellweger (Credit: AP/Reuters/Kevork Djansezian/Rich Fury/Charles Sykes/Photo montage by Salon)

Sia is the most famous woman in the world that most people wouldn’t recognize if she passed them on the street.

Since launching her comeback in 2011 with the David Guetta-produced “Titanium,” the Australian singer-songwriter (née Sia Furler) has amassed an enviable string of Top 40 hits, including “Chandelier,” “Elastic Heart,” and “Cheap Thrills,” which currently sits at no. 6 on the Billboard Hot 100. She has worked with artists as diverse as The Weeknd, Eminem, Flo Rida, and Giorgio Moroder and written songs for Katy Perry (“Double Rainbow”), Carly Rae Jepsen (“Boy Problems”), Beyoncé (“Pretty Hurts”), and Britney Spears (“Perfume”).

But if Sia’s ambition and prolific output are unmatched in modern pop music, there’s one thing that is rarely part of the conversation: the way she looks. The singer regularly hides her face behind a oversized, two-toned wig when she performs live, adorned with a giant black bow. The choice is reminiscent of artists like Daft Punk and MF Doom, who mask themselves when performing to disappear inside their personas.

Sia presents herself as a cipher, frequently using reality star and dancer Maddie Ziegler (who shot to fame at the age of eight on Lifetime’s “Dance Moms”) as her stand-in. There’s a performance art aspect to the gesture, as if she’s killing the self in order to best express the universal truths of her music. Although “Chandelier” deals with the singer’s history of alcoholism, the top-10 hit is expertly designed to be the soundtrack to your life, the song you listen to when you cross the finish line at your local 5K.

But for Sia, masking is both an artistic statement and a pragmatic decision.

Working with some of the biggest names in the industry, the singer has learned a lot about what it means to be famous, and she’s clearly taken notes. Beyoncé Knowles-Carter, her frequent collaborator, exercises tight control over her public image (even having images of herself on the Internet she doesn’t like removed) as a way to maintain privacy. You only know about Beyoncé what she wants you to know—which, especially for someone of her worldwide renown, is very little.

“If anyone besides famous people knew what it was like to be a famous person, they would never want to be famous,” Sia wrote in a Billboard op-ed. She compared fame to “the stereotypical highly opinionated, completely uninformed mother-in-law character and apply it to every teenager with a computer in the entire world.”

“If I were famous, I might want to see what is happening on the news channel, or on CNN.com,” Sia continued. “But I couldn’t. Because I would know that I might run into that mother-in-law there, sharp-tongued and lying in wait for my self-esteem. And she’s not just making cracks about dying before I give her some grandkids, she’s asking me if I’m barren. She’s asking me whether I’m ‘so unattractive under those clothes that her son/daughter doesn’t want to fuck me anymore,’ or if I’m ‘so dumb I don’t know what a dick is and how to use it.’”

By making herself invisible, Ms. Furler has managed to sidestep the pervasive sexism famous women are subjected to in the media, in which their looks (or rather their relative fuckability) is treated as the only thing that’s important. This isn’t a hypothetical thought experiment. For women like Sia, Renée Zellweger, and Margot Robbie, it’s a daily reality.

Zellweger, once a household name after a string of roles in hits like “Jerry Maguire,” “Chicago,” and “Cold Mountain,” took a six-year hiatus from acting after 2010’s little-seen “My Own Love Song,” a biopic of George Hamilton. The 47-year-old actress returned to the public eye two years ago on the red carpet of the 2014 Elle Women in Hollywood Awards. The appearance stoked public outcry when it appeared that the Oscar-winner, like many actresses before her, had gone under the knife, debuting a new look.

Many argued that if she looks different than she used to, she must be a different person. “Can I still call you Renee Zellweger?” asked The Atlantic’s Megan Garber. “Are you still Renee Zellweger? … Was it Botox? Or an eye lift? Or a cheek lift?”

In the past two years, those questions have been treated as the only questions, with Zellweger’s face subjected to intense scrutiny every time the public is reminded she exists. Most recently, longtime Entertainment Weekly critic Owen Gleiberman, now the senior film critic at Variety, revived the interrogation of her looks in a misguided op-ed about the trailer for “Bridget Jones’ Baby,” the forthcoming installment in the British rom-com series. (This is despite the fact the trailer technically debuted months ago.)

“I didn’t stare at the actress and think: She doesn’t look like Renée Zellweger,” Gleiberman said. “I thought: She doesn’t look like Bridget Jones! Oddly, that made it matter more. Celebrities, like anyone else, have the right to look however they want, but the characters they play become part of us. I suddenly felt like something had been taken away.”

Gleiberman is a good critic, but he falls into a trap that’s very common when we’re discussing famous women: The rest of Zellweger’s life is treated as much less interesting than how she looks.

Think about it. You’re sitting down with Renée Zellweger, and you have the chance to talk to her about her long, varied career in film. She’s been successful for over two decades, working with A-listers like Tom Cruise, Matthew McConaughey, Nicole Kidman, Bradley Cooper, Catherine Zeta-Jones, George Clooney, and Russell Crowe. She’s won three Golden Globes and managed to stay on top despite the fact that Hollywood looks at aging actresses as kindling to keep the young warm. What would you want to know? There’s certainly no shortage of material.

Gleiberman, though, repeatedly downplays her accomplishments, portraying her as an ordinary girl who stumbled onto her fame (or as he puts it, “had been plucked from semi-obscurity by the movie gods”). Because she’s a beautiful woman who, alas, doesn’t look like Christy Turlington, she’s treated as an anomaly and an aberration—but most of all, a cautionary tale.

“Zellweger, as much or more than any star of her era, has been a poster girl for the notion that each and every one of us is beautiful in just the way God made us,” he writes.

A similar thing happened to Margot Robbie when she was interviewed by Rich Cohen in an interview for Vanity Fair. Robbie, a tremendous talent, has become one of the most sought-after actresses in the business after her breakout role in Martin Scorsese’s “The Wolf of Wall Street.” She’s starred in seven movies in the last two years, nearing Jessica Chastain-levels of ubiquity, and will be one of a handful of women to topline her own superhero film when the planned spinoff to “Suicide Squad,” in which she plays Harley Quinn, hits theaters.

But of course, Cohen is much more interested in the 25-year-old’s eyes (described as “painfully blue”) than he is her career. “She is 26 and beautiful, not in that otherworldly, catwalk way but in a minor knock-around key, a blue mood, a slow dance,” he writes. “She is blonde but dark at the roots. She is tall but only with the help of certain shoes. She can be sexy and composed even while naked but only in character.”

Cohen doesn’t get around to calling Robbie “ambitious” (while comparing her to a Martian) until 14 sentences in, after he’s already spent 185 words committing a random act of rhetoric foreplay.

The profile is reminiscent of a scene from “Galaxy Quest,” in which Sigourney Weaver’s character, Gwen DeMarco, complains about the kinds of questions she gets asked in interviews. Gwen claims that a recent profile of her in TV Guide amounted to “six paragraphs about my boobs and how they fit into my suit.” She said, “No one even bothered to ask me what I do on the show.” (This actually happened to Jeri Ryan, who played a borg on “Star Trek: Voyager.”)

As Emma Gray pointed out in the Huffington Post, such treatment of famous women is so common it could be a meme generator—from pop singer Sky Ferreira being reduced to her “sex appeal” in L.A. Weekly (it’s even in the headline!) to a description in Esquire of Megan Fox as “a screensaver on a teenage boy’s laptop, a middle-aged lawyer’s shower fantasy.” These are beautiful women, sure, but they are lots of things, masses of cells and contradictions who are more than digital avatars. But rarely are they allowed to be three-dimensional and real.

What does it take for women to be seen as professionals and industry leaders, rather than objects for male consumption? Sia did so by taking her body of out the public conversation, even though what she looks like isn’t technically a mystery. (A simple Google search will unveil the woman behind the curtain.) But by making that secondary, Ms. Furler has forced the public to do something we so rarely do when it comes to women’s artistry—focus on the music itself.

“I was at Target the other day buying a hose and nobody recognized me and my song was on the radio,” Furler told Chris Connelly of “Nightline” back in 2014. “And I thought, ‘Okay, this experiment is working.’”

If only every famous woman had the luxury to disappear behind their work.

A fear not shared by all Americans: The privilege of knowing you’ll never be a police brutality victim

(Credit: Reuters/Eric Thayer)

Alton Sterling’s 15-year-old son breaking down and crying during a press conference in the wake of the killing of his father by a Baton Rouge police officer.

A 4-year-old girl in the back seat of a car witnessing a police officer kill her mother’s boyfriend.

These are things that my white children will never experience. They don’t have to worry about their father being slammed to the ground by officers of the law and then shot. They don’t have to worry about me being pulled over and then shot through an open car window for carrying a licensed concealed weapon.

The preparatory narrative that many black adults must have with the younger generation explaining how they should react when a police officer stops them. My children will never have to prepare for the inevitability of being harassed or harmed by the law because of the color of their skin.

And the true sorrow of these United States is that it’s likely that children like Trayvon Martin, Jordan Davis, and Tamir Rice heard “The Talk,” but to no avail—white supremacy and American violence was much bigger than them.

For over a decade now I have taught a survey of American literature, from its beginnings to 1900, at Denison University. Teaching this course is a constant reminder to me of how violent our American narrative is. It is also a reminder of how much work has been done to change that and how much work we have to do.

I always end the course with W.E.B. DuBois who addresses a future America by announcing in “The Souls of Black Folk” that race would be the central problem of the 20th Century. For DuBois being a “problem” is both a struggle and a challenge, but by focusing on that dilemma he tells readers that in this country black people must be ever-mindful of white supremacy.

“The Souls of Black Folk,” like much of DuBois’s work, is infused with the kind of pragmatic realism embedded in “The Talk.” DuBois had to be pragmatic, had to live in the real world, because he lived in Atlanta at a time when it was deemed okay to display the knuckle bones of a black man in a grocery store—a man named Samuel Hose who had been beaten, had his fingers, ears, and genitals cut off, his face skinned, and then was set on fire.

DuBois is not the only example of a black writer engaging with the future in the present in order to prepare a younger generation for what they will encounter. So many African American writers are haunted by this struggle that it seems like a central trope in African American literature. It’s found in the work of Ernest Gaines, Toni Morrison, James Baldwin, Frederick Douglass, and even in the work of eighteenth-century writers like Prince Hall. It likely resonates in oral histories shared among enslaved peoples. Ta-Nehisi Coates’s letter to his son, “Between the World and Me,” carries this trope into the present.

The message is clear: you must prepare to live in a racist world. You must be on guard. You must always know that your life is not your own. To not be so is to be naïve and short-sighted; it is to put yourself and your community in jeopardy.

There is no such trope in white American literature, and there is no such thing as “The Talk” for white children.

The story that most white children hear in America is noticeably different — it is one of progress, of comfort, of the false idea that we are moving gracefully toward a more multicultural society from a satisfactory, comfortable present.

And yet, the violence of slavery and white supremacy have defined and shaped our present; they have shaped what it means to be white in this country. These violent legacies persist in our systems of policing and education, housing and health care. They persist in the sorrow felt by Alton Sterling’s son and in the experience, the burden, that 4-year old girl will have to carry with her forever.

As long as that kind of violence pervades our culture, we are lost.

And until white people understand what has been so absent from their realities, from their educations, we can’t possibly understand or work as allies. Until white people can talk to their children about those things—about the violence we are shielded from—there’s no future.

Video’s role in tragedy: How snapping photos or shooting videos helps police and the public alike

Diamond Reynolds, the girlfriend of Philando Castile, weeps during a press conference at the Governor'sResidence in St. Paul, Minn., Thursday, July 7, 2016. Philando Castile was shot in a car Wednesday night by police in the St. Paul suburb of Falcon Heights. Police have said the incident began when an officer initiated a traffic stop in suburban Falcon Heights but have not further explained what led to the shooting. (Leila Navidi/Star Tribune via AP)

This piece originally appeared on The Conversation.

With three billion camera-equipped cellphones in circulation, we are awash in visual information. Cameras are lighter, smaller and cheaper than ever and they’re everywhere, making it possible for nearly anyone to watch, create, share and video.

One of the most dramatic ways camera proliferation is changing our lives is in the area of law enforcement. Dashcams have been around for years and are increasingly popular. President Obama called for local departments to start equipping officers with badge cams. Citizens, too, have cameras, usually in their smartphones, but increasingly on their own dashboards. Yet even with all this footage, we are often in the dark about what really happens during police encounters (although videos were captured of this week’s murders of Philando Castile and Alton Sterling).

For the past three years, I’ve been studying the police accountability movement and the role that video has played in fueling activism by citizens concerned about criminal justice policies in their communities. “Cop-watching,” as it’s known informally, cannot be understood without also studying the way the law enforcement community uses video. As a result, my work has taken me to courtrooms, police stations and city streets where citizens and police are watching each other through their camera lenses.

Multiple perspectives, one timeline

A recent research project I conducted with my husband, David Alan Schneider, showed how this worked in a courtroom. We examined the way video evidence played out in a criminal courtroom. On January 1, 2012, as a woman under arrest by Austin, Texas, police called for help, Iraq War veteran-turned-activist Antonio Buehler pulled his phone out to photograph the scene. He ended up getting arrested himself, and put on trial for allegedly interfering with police work.

The jury watched three videos and listened to multiple versions of what happened that night. Police alleged that Buehler lunged at them menacingly — he argued that he was the one assaulted. Another bystander, across the street, had also filmed the scene, showing officers throwing Buehler to the ground. Police dashcam video showed part of the start of the woman’s drunk-driving arrest and included some of the audio. A surveillance camera from the nearby convenience store bore silent witness and showed where Buehler’s car was in relation to the rest of the action.

Three videos and three narratives, but time passes along only one line. By incorporating the other evidence into what they saw, and tying everything to that one timeline, the jury came up with yet another constructed narrative, acquitting Buehler.

The famous Rodney King case in 1991 that acquitted four officers and sparked riots in Los Angeles shows just how important the timeline is to our ideas of reality and truth. When the video is played in real time, the scene is devastating — officers are seen swarming the truck driver and striking him swiftly and repeatedly.

But defense attorneys for the officers never played the video straight through — instead they stopped and started it second by second. With the images taken out of context and isolated from the timeline, the moments shown seemed more defensible. The jury, left with competing narratives and a set of images detached from the timeline, found in favor of the officers.

Documenting police work

Video’s combination of timeline with visual information has significant implications for the current debate about badge-cams, dash-cams and cop-watching. When it comes to really figuring out what happened, more cameras are helpful — multiple perspectives tied to the timeline present a narrative that better mimics the way we move through the world. We don’t stand in one place, like a surveillance camera, nor do we hold our focus on one spot. We look close, we scan and move. For the sake of really understanding an event, the more video, the better. And as demonstrated by the Facebook video Castile’s girlfriend, Diamond Reynolds, took during his murder, livestream might be the best.

From a public policy perspective, this is expensive and complicated. Much depends on who controls the cameras and the resulting videos. Dashcams only show what was in front of the car. Like most of the video from the drunk-driving arrest in Buehler’s case, the confrontation between Sandra Bland and a Texas police officer happened outside the camera’s range. Badge-cams can show what was in front of an officer, but they come with a long list of other considerations: privacy for certain kinds of crime victims and the officers themselves; protocols for when and how to turn them on and off; and storage and distribution procedures for the millions of hours of video they will eventually collect.

Citizen videos have provided some of the most dramatic and troubling evidence of police misconduct, but by nature are happenstance and the result of being on location at a particular moment. Based on my own research, it’s clear that cop-watching video only captures events of note once in a while — their work is most effective as a preventative. This “sousveillance” movement is conceived as a way for the public to monitor and keep a check on power, serving as a sort of democratized fourth estate.

Do cameras lie?

My interest in video has grown out of my first career as a TV journalist and a lifelong interest in how photography conveys reality, which is not nearly as simple as it seems. True, cameras perfectly capture the light waves from a scene in front of them in ways that we could never duplicate by drawing or painting. Cameras can provide extraordinary evidence, which is why police and crime scene investigators document everything, why journalists use cameras as documentary tools and why citizen journalists are able to gain credibility for their own investigations.

Yet anyone who has ever looked at photos someone else took of them at the party last weekend and thought to themselves “I don’t look like that!” can relate to the way a camera distorts and flattens a scene. There’s much more, though. Consider the way photographers work, using their own bodies to capture a particular perspective, with lenses that do what our eyes cannot, framing a scene in a way that captures certain elements but not others. Those are just some of the decisions that happen before the darkroom or Photoshop stage, when images are cropped, enhanced and sometimes distorted in misleading ways.

Then there are the ways our brains mislead us, because images work differently in our heads than language does. Pictures seem to take a faster highway, metaphorically speaking, inspiring emotional responses faster than language and its logical reasoning. They seem to work in our memories differently than words do. Add to this the way photographic images feel real, and it becomes easier to understand why images can be very convincing even when we know we’re being manipulated by special effects in a movie or an ad that shows a cupcake that’s simply too perfect to be true — but now we’re hungry.

Video offers up its own set of real and unreal characteristics. We’ve all seen the way editing can change the nature of a soundbite or a TV story — the now-discredited attack video about Planned Parenthood is a perfect example of how scenes can be deliberately distorted. Yet unedited, raw video, while subject to all the limitations of cameras generally, usually adds not just images but also audio to the timeline. Still images offer up a form of visual reality. Raw, unedited video shows us what happened in what order, and that means it provides its own version of a story.

Unedited, raw video is a “triple threat” for public safety. It has the visual presence of photography; the power of language in its audio; and the ultimate, unyielding evidence offered by the timeline. The public must demand transparency and input for the way police and any other branches of government creates, stores and distributes it. The public must exercise its right to video police and other public servants working in public spaces. Cameras may not lie, but people do all the time. While it’s not infallible, video offers an invaluable way to find the — the tragedies this week are more than enough evidence of that.

Sanders’ victory: How Bernie ended the Cold War in 2016

Bernie Sanders (Credit: Reuters/Mary Schwalm)

I can remember the exact moment when it occurred to me that the Cold War was finally over. It was about three months ago, at an event for prospective university students and their parents; at the end, a smart, energetic college senior took questions from the audience. When asked to describe the political climate on campus, she said it was broad and inclusive, featuring conservatives, Trump supporters, liberals, progressives, and, as she put it, “democratic socialists like me.” She wasn’t trying to be provocative. No one in the audience batted an eye. She referred to socialism in a purely neutral, descriptive way, and everyone moved on. The lingering effects of Cold War ideology had finally faded away.

The Sanders campaign is about to end in defeat, and with his expected endorsement of Hillary Clinton, Bernie will finally fall in line with the Democratic Party establishment. But his surprisingly popular movement has achieved something remarkable – it marks the end, in a cultural sense, of the Cold War. Though that struggle between capitalism and communism formally ended 25 years ago, the effects of the conflict continued to warp our political culture long afterward, forestalling any meaningful discussion of democratic socialism. Long embraced in Europe, “socialism” in America was too often falsely equated with “communism,” which was inextricably tied to the gulag, Stalin’s show trials, and Soviet imperialism, among other outrages. The real end of the Cold War would mean an end to its distorting influence on our domestic political culture, and it finally came in 2016, precipitated by the unlikely combination of the financial crisis and Bernie Sanders. A self-identifying democratic socialist has won twenty-three major-party primaries or caucuses, an outcome unthinkable even a few years ago.

Before this presidential election cycle, conventional wisdom suggested that socialists in America tended to be cranks, out-of-touch college professors, or both, populating the margins of our political culture. But thirteen million people just voted for Sanders in the primaries, and he won states in New England, the midwest, the plains, and the Pacific northwest. Starting with little money, no name recognition, and few endorsements, he took Hillary Clinton, who had lots of all of those things, nearly to the wire.

Until now, self-identifying socialists went exactly nowhere in U.S. elections. In recent decades, Democrats with national aspirations even tried to avoid the “liberal” label; “socialist” was unimaginable. As early as 1906, the title of German sociologist Werner Sombart’s study of American exceptionalism famously asked “Why is there no socialism in the United States?” It’s a difficult question to answer, but it’s clear that more recently, since World War II, Cold War ideology and fairy tales of American rugged individualism combined to create a culture that lumped together repressive one-party dictatorships and national health insurance. Democratic socialism wasn’t discussed in any productive way, tainted as it was by its supposed connection to the evil communist enemy. That’s changing.

Why now? The simple passage of time is part of the story. There are currently millions of young voters, among whom Sanders was highly popular, who were born after the Cold War was over. To many of them, the face of socialism is a scruffy grandpa type with a Brooklyn accent and promises of debt-free education, not, say, a mustachioed mass murderer. And as someone who teaches college undergraduates, based on numerous conversations with students, I can confirm that Sanders’s socialism doesn’t bother them at all.

In addition to the distance provided by passing years, the sorry state of our capitalist system set the scene. Wall Street deregulation, nakedly corrupt campaign finance rules, and sharply rising inequality have taken their toll on our social fabric, and triggered a loss of faith in our institutions. And none of us should be surprised that in the wake of the entirely avoidable Great Recession, people are looking for alternatives; more promises of tax cuts aren’t so convincing anymore. A democratic socialist suddenly seems to make a lot of sense to a lot of people, and for good reason.

Throughout the primary, as those people began to support Sanders in significant numbers across the country, they tended to be caricatured in the media as naïve idealists. Clinton voters, on the other hand, were supposedly pragmatic and sensible, choosing to support an electable candidate with workable ideas. But this is wildly unfair.

Like every candidate, Sanders has his weaknesses on policy matters, and it’s fair enough to criticize his lack of specifics in some cases. But ideologically speaking, European-style democratic socialism offers more realistic solutions to many of our national problems than Clintonian neoliberalism. As Sanders was perfectly willing to point out in the campaign, the countries that embrace his kind of socialism tend to be the most prosperous, happiest, most equitable, safest, healthiest places on earth. The neoliberal, globalist vision embraced by many mainstream Democrats and Republicans, both Clintons included, is mostly fantasy. Sanders voters were ready to embrace democratic socialism not because they’re wild-eyed idealists, but because it works.

Of course, the United States, as we are constantly reminded, is not Denmark. And Bernie’s success does not mean that a wave of socialism is about to transform our political culture. After all, he lost. And the word socialist hasn’t completely been stripped of negative connotation for everyone. There are still people who aren’t sure what the word means, but like to throw it around as an insult. And confused Tea Partiers like to denounce President Obama as a socialist/communist/Nazi, among other nonsensical things. But in the past year or so, Democratic primary voters got a chance to seriously consider some ideas put forth by a democratic socialist, and liked them. This seems to indicate that we can at least have productive discussions that involve the word socialism from now on. Clinton’s conversion to the Sanders-like “new college compact” is an indication of the practical effect of the Sanders campaign, and a laudable one at that. In the bigger picture, it seems that Americans can now finally discuss and debate socialism and sometimes even cast a meaningful vote for a socialist in a major election. The Cold War is finally over. And it’s about time.

“A Trump speech is just a story starring Trump”: Science proves The Donald is a textbook narcissist

Donald Trump (Credit: Reuters/Lucy Nicholson)

Many people have pointed out that Donald Trump is a narcissist, but what does that actually mean? The late Theodore Millon, one of the co-developers of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, devised the subtypes of personality disorders and described the attributes of the “unprincipled narcissist” disorder as: deficient conscience; unscrupulous, amoral, disloyal, fraudulent, deceptive, arrogant, exploitive; a con artist and charlatan; dominating, contemptuous, vindictive. These personality attributes shape behavior patterns which, in the unprincipled narcissist, tend toward self-absorbed egotism. Symptoms include an excessive need for admiration, disregard for others’ feelings, an inability to handle criticism, and a sense of entitlement.

Identifying an unprincipled narcissistic disorder sheds a lot of light on Trump’s actions. For instance, his apologists are forever praying for and assuring themselves that soon Trump will stop promoting patently egregious lies, and that soon, very soon, Trump will pivot and become more presidential; and soon, very soon, Trump will quit attacking his former and now vanquished Republican rivals and move on to the main task of demonizing Hillary; and soon, surely, very, very soon, Trump will seriously up his campaign game. Nope. None of that is going to happen. They don’t understand the self-absorbed egotism that is the fundamental driving essence of Trumpness.

Noticing the lies and shifting policy positions misses the point. A Trump speech is just a story starring Trump. To Trump, lies are not bad in the sense that there are negative moral attributes attached to them. Lies are just convenient tools that he uses to stroke his self-indulgent puffery, to incite his followers, or to provide a means of damaging his opponents. There are no moral components in Trump’s considerations about whether to say a particular thing or not, only whether a narrative will advance Trump’s ambitions as he sees them at that time. So Ted Cruz’s dad was in on the Kennedy assassination, Barack Obama was complicit in the Orlando terrorist attack, Hillary Clinton sold uranium to the Russians, the United States is allowing in hundreds of thousands of immigrants from the Middle East without any background checks at all, and on and on and on. So many lies that teams of fact-checkers can’t keep up any more than Ethel and Lucy could package all the chocolates.

Similarly, positions on issues are not conclusions derived from analysis of facts and ideas from the perspective of some foundational political principles. Issues themselves are ephemera swirling around in his “great” mind like pieces of flotsam and jetsam in a hurricane, flashing in and out of his stream of consciousness and available to be bent into whatever position is advantageous to him at that particular point in time. The position isn’t about the issue; it’s about Trump. It’s about the self-absorbed egotism. It’s the greatness of being Trump in the moment that is the driving motivation, so positions on issues are not fixed if Trump wants to tell the story a little differently, and lies are unbad if Trump needs to tell them to keep the self-aggrandizing tale going.

Given the utter disregard for the necessity of dealing in what other people think of as “things that are true,” coupled with a similar disregard for fixed positions on issues, every Trump speech is subject to a kind of political Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle in that it is not possible to measure both the momentum of the speech as Trump winds up his audience and his fixed position on any issue under discussion. If parts are true, then great! What a coincidence! If parts are not really, actually true, they should be, and that’s close enough for Trump. That’s why Trump doesn’t like to use teleprompters. The scripted speech on the teleprompter interferes with tangents he can wander down, expressing the true wonder of himself.

Another key feature of Trump’s particular personality disorder is his pronounced vindictiveness. Some Republicans wonder aloud why Trump keeps attacking other Republicans and doesn’t move on from the primaries mindset to the main-event general election. He cannot. He has been dissed not only by the effrontery of being opposed, but after the vanquishing of his enemies, they still refuse to endorse him. Intolerable! Disqualify them from ever running for office again, ban reporters who ask confrontational questions, blacklist newspapers, vow to change the libel laws so that he can sue more easily. He can’t stop and he can’t control it.

And so it goes in the Grand Old Party, which has seen fit in past elections to threaten the country with contenders to be president of the United States and leader of the free world such as Sarah Palin, Michele Bachmann, Herman Cain, Tom Tancredo, Sam Brownback, Rick Perry, Ben Carson, Rick Santorum, Ted Cruz, Mike Huckabee and Carly Fiorina, each of whom brought in their own coterie of followers who proved by their support that they have a very limited capacity to rationally analyze the consequences of their actions balanced by an almost unlimited degree of gullibility. Perfect marks to be conned, lied to and cheated.

We are just a few short weeks from when Chief Birther Donald Trump, an unscrupulous, amoral, vindictive, con man, sweeps into Cleveland and becomes the scariest and most profoundly unqualified person to ever be nominated by a political party in the history of the United States.

The Republican Party will pay a heavy price when America rallies against him.