Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 56

June 2, 2018

Mystery of Earth’s missing nitrogen solved

AP/NASA

This article was originally published by Scientific American

Experts used to think nearly all nitrogen in soil came directly from the atmosphere, sequestered by microbes or dissolved in rain. But it turns out scientists have been overlooking another major source of this element, which is crucial to plant growth: up to a quarter of the nitrogen in soil and plants seeps out of bedrock, according to a study published in April in Science.

Apart from a few scattered studies, “the [research] community never thought to look at the rocks,” says lead study author Benjamin Z. Houlton, a global ecologist at the University of California, Davis. This discovery has implications beyond understanding the planet’s nitrogen cycle; it could also alter climate models. It suggests plants in certain areas may be able to grow faster and larger than previously thought and could thus absorb more carbon dioxide, Houlton says.

As global temperatures rise, calculating how much heat-trapping carbon dioxide plants soak up is becoming increasingly important. The exact amount remains uncertain, but Houlton notes that plants could provide “a little bit more of a cushion . . . to store our carbon pollution.”

Previous research had examined the balance between how much nitrogen in sediments makes it to the mantle (the layer below the earth’s crust) and how much volcanoes release into the atmosphere (which is 78 percent nitrogen). Beginning in the 1970s, a few studies showed that several types of sedimentary rock contain nitrogen from long-dead plants, algae and animals deposited on the ancient seafloor. A handful of papers suggested the element might leach into soil in certain places. But scientists did not follow up on these findings, and the amount of nitrogen released as rocks weather was thought to be insignificant. “It wasn’t entering into the paradigm of how we think the nitrogen cycle works,” Houlton says.

He and his colleagues published a study in 2011 in Nature finding that forest soils above sedimentary rock in parts of California contain 50 percent more nitrogen than in areas overlying igneous (volcanic) rock. They also found 42 percent more nitrogen in trees growing over sedimentary bedrock. Although the research suggested the element was making its way from rocks into soil and plants in a few specific areas, it did not show this to be a significant phenomenon worldwide.

In their new study, Houlton and his colleagues used California as a model geologic system because the state contains most of the planet’s rock types. They measured nitrogen levels in nearly 1,000 Californian samples and in others from around the globe. They then developed a computer model to calculate how quickly the earth’s rocks break down and release nitrogen into the soil.

Nitrogen liberated by weathering processes eventually makes its way to the ocean, where it is deposited in rocks as they form on the seafloor. Tectonic plate movement lifts up the rocks; they degrade and release their nitrogen, which gets absorbed by plants and animals and trapped in rocks again — perpetuating the cycle. Weathering can involve both physical breakdown — which is accelerated when rocks are thrust upward and exposed to the elements as mountain ranges — and chemical dissolution, such as when acidic rainwater reacts with compounds in rocks.

William Schlesinger, a biogeochemist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, N.Y., who was not involved in the study, says he once measured substantial nitrogen levels in rocks but did not “put two and two together.” He had assumed this was not a widespread or important source of the soil nutrient. But Schlesinger cautions against overinterpreting the significance of the new findings, noting that the amount of nitrogen entering soils via synthetic fertilizers dwarfs that from rocks. He thinks the discovery should be incorporated into global models for nitrogen and carbon but adds, “I don’t think it’s going to rewrite our understanding of climate change.”

Nevertheless, the findings explain puzzlingly high nitrogen levels in some soils. “Our study helps to resolve that gap between what the observations were saying and what the models were predicting,” Houlton says. These results are especially important in considering massive, nitrogen-rich forests in Canada and Russia, many of which overlie sedimentary formations.

Houlton says that the new study used rather conservative measurements of nitrogen in rocks and that the actual quantity is probably higher than his team calculated. “certainly humans and our activities have dramatically increased the amount of erosion,” which would boost nitrogen release through weathering, he says — and “we haven’t considered that in our study.”

Top Trending

Check out the major news stories of the day

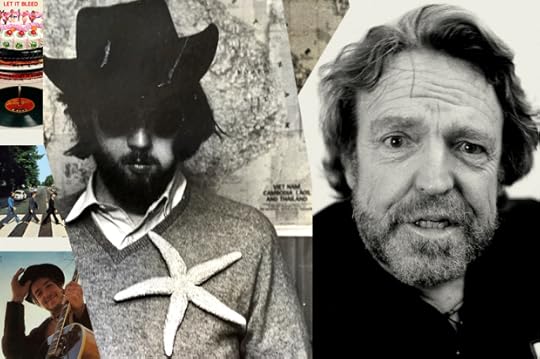

My long strange winter trip with John Perry Barlow, a legend in the making

Wikimedia/Joi Ito/Salon

On a windy October night in 1969, John Perry Barlow blew into our rented house on the Connecticut shore like a blast from the past and the future too. Dressed as usual in a leather coat and cowboy hat, he had a suitcase and backpack he’d lugged all the way from India, through JFK Airport and straight up the highway to this funky summer cottage on Long Island Sound where he’d never been before. How did he even find the place?

He looked exhausted but also wild-eyed, preternaturally awake, with an “aha” look on his face that had nothing to do with homecoming or navigation. He shrugged off his pack and extracted a bronze, nearly-life-sized head of a Buddha. When he handed it to me, I almost dropped the thing. It was heavy. Solid bronze? The neck of it had been sealed over with some thick, dark substance that had hardened almost into a kind of cement.

Barlow rubbed his finger on the dark, sealed neck, took a whiff of it and handed it to me to do the same. I couldn’t smell anything, and that was the point.

“The Customs guys checked it out for 10 or 15 minutes, sniffing it, handing it back and forth. They finally decided not to bother," he said. "The guys who sealed this up for me assured me it would harden up and give off no smell. One of their main ingredients was cow dung.”

Barlow rummaged around in the kitchen for tools, knives, drill bits, a hammer. Then he whittled and chipped at the dark neck of the bronze head. The sealing material began to fall off in pieces. After a while he finally cleared out the Buddha’s neck, reached inside and pulled out a wrapped package that turned out to be a kilo of Nepalese black hashish in a thick braided bundle, just under a foot long. To pack it tight and keep the hash from banging around in the Buddha’s brain, Barlow had stuffed the head with flaky, reddish-brown Indian ganja.

I had never seen that quantity of hash in one lump before. The smell was exotic and outrageous. Barlow loaded a pipe with some ganja and whittled off flecks of the hash to sprinkle on top.

“Man, this is the strongest stuff I ever…” I said.

Barlow smiled and nodded as I turned into a mute stone statue.

And that became a ritual whenever anyone visited that house. Often in the very first minutes, Barlow would unveil his great meteorite of hash, encourage his guests to sniff it, and then chip off bits into his pot-filled pipe. And the reaction was invariably the same, sometimes with red eyes and coughing.

“Jesus, that is the strongest shit I ever . . .”

And then language would disappear in smoke as paralysis set in. Barlow would nod and confirm the time it had taken from first inhalation to complete loss of mental and motor skills. It became a kind of test, an initiation to this lost house we had casually agreed to share for a season.

Barlow and I knew each other from college. We were among the stoners, booze hounds, skirt chasers and well-read wise-guy layabouts who survived the Vietnam War with college deferments, and the dark tide of existential angst with the help of lysergic acid. Barlow always had more money than most of us and ran a kind of salon in his large, funky apartment in town, where the music ran hot and indulgence of all substances was encouraged. On any given night any manner of passersby and hangers-on might be on hand there in any frame of mind.

Barlow and I agreed to rent a house together away from most friends and traffic in order to get some writing done. When he went off to South Asia, I rented a summer house in a colony of empty cottages on Long Island Sound. Most places there were uninsulated and boarded up tight, but one doctor thought he might as well get money for his place instead of letting it sit vacant all winter. So he and I struck a deal for nine months, September through May.

It was a small two-bedroom, a few hundred feet from the water’s edge, sparsely furnished, but with a functional bathroom, kitchen and fireplace. To pay my rent I got a job as a daily reporter on the state desk of the Hartford Courant. I started out in a bureau on the shore, which was when I rented the house. But soon enough I had to report to work in Hartford most days, a 40-minute commute from our house. I had hoped to write fiction in my spare hours but my job took much more time and energy than I had imagined.

The doctor who rented me the cottage came by a few weeks later to check up on things. Barlow had not yet arrived and I hadn’t changed much of anything in the place. I was basically camping, only there long enough to sleep. I usually made myself breakfast but not evening meals. Everything looked OK to him, so he didn’t bother coming by again until spring. By then it was much too late.

A few days after Barlow’s return from India, a U-Haul truck pulled up to the cottage full of his stuff from storage. Like a magic box on wheels, it disgorged his 1250cc BMW motorcycle, a couple of ornate chairs, his stereo system and large library of LPs, an extensive wardrobe with many pairs of cowboy boots, various books and unassorted treasures including a huge Nazi flag, bright red with a black swastika inside a white circle. Neither an anti-Semite nor a violence-prone right-winger, Barlow must have acquired it purely for its shock value. He promptly draped it over the couch in the living room, where it remained.

One of the benefits of Barlow’s deep pockets was listening to great sounds as he went on a buying spree of the best music of the moment, artists and tunes I had never heard before, which played in that house over and over again all winter, until I knew them all and their order on the albums. "The Band" was a favorite, with its incredible harmonies and driving organ beneath and beyond the melody, the album photos making them look like 1890s members of the Wild Bunch, our co-conspirators in that mad, mad season on the shore.

A drawback of Barlow’s wealth, however, was his method of splitting expenses. I didn’t mind coughing up half the rent and utilities. But he posted a blank paper on the kitchen wall with our names on each side of a line down the middle. On his side he jotted prices of expensive steaks and bottles of whiskey, the kind of stuff I couldn’t possibly afford and seldom got to taste anyway, as JPB rapidly consumed what he bought. After some acrimony this practice ended.

We quickly fell into a kind of routine. I would wake up around 10 a.m., make coffee and stagger out to my car for the 40-minute drive to work. I would often work until the 11 p.m. deadline for the morning edition, grab a drink in town, and then drive back to our house, which would usually be percolating in high gear at the midnight hour. It was weird to enter the dark, silent suburb of shuttered cottages and then see the lights and hear the raucous party sounds — "Suite: Judy Blue Eyes" by Crosby, Stills & Nash was in rotation — coming from our place, the only open grave in the cemetery.

Anything might be happening and anyone might be there swilling booze, smoking dope, talking trash over the music, laughing and flirting if women were around. Any food on hand wasn’t fancy and didn’t last long. If we found something to burn in the fireplace we burned it, but wood was hard to come by since these were summer homes and none of us actually made much effort to buy any. Occasionally someone might stagger and fall against a table or chair. If the furniture broke, we most often fed it to the fire, with disparaging remarks about how tacky it was and how the landlord would never miss it. Despite the rudimentary insulation, the place stayed chilly and needed all the warming it could get.

Very often the hour grew too late and the visitors became much too impaired to drive off anywhere, so there were often crashers in chairs, on the floor, and for one lucky person (or two) a relatively comfy spot on the couch, though that was also under the Nazi flag. Instead of our attempted isolation providing peace for creativity, it merely created an inconvenient distance between our place and the rest of the so-called civilized world.

I would often have to tiptoe among the fallen on my way out to my car in the morning. I learned early on not to try to stay up with the all-nighters. The walls of that place were thin, so the music (cue: Bob Dylan's "Country Pie") and the conversation — not to mention the sex — was impossible not to hear. But stoned exhaustion was usually enough to knock me out, even on the craziest nights.

Barlow enjoyed hosting, however casually, and could be an amusing raconteur, though his stories almost always centered on himself. As long as I had known him, Barlow had a strong aspiration to be legendary in some way or another. He just hadn’t quite figured out how yet. He sometimes said he wished he was an old man — a strange desire, it seemed to me. But I think what he meant was that as an elder he would have the gravitas to speak and act from his no-doubt already-established legendary status. He and Bob Weir of the Grateful Dead were friends from boarding school and Barlow got the Dead to come to our small college to play high-energy, spaced-out open-ended concerts. But he and Weir had not yet started writing songs together.

One of his fanciful schemes was to host a Grateful Dead concert at his family’s ranch in Wyoming for free, to attract as many fans as possible. If half a million Deadheads showed up, as hippies did at Woodstock earlier that summer, the crowd would outnumber the citizens of Wyoming and could elect Barlow governor of the state, who could then proclaim new levels of freedom and license. Thus the chatter of Babylon, babbling on. Neil Young’s first album, released earlier that year, had an instrumental track called “The Emperor of Wyoming.” Coincidence? Definitely.

What we knew every minute of every day and night that year was that war was raging in Vietnam, a so-called “discretionary conflict” — unrelated to the defense or well-being of the United States — in which U.S. troops were torturing and murdering Vietnamese villagers and destroying their lands and in which we, as young men between the ages of 18 to 26, were expected to make ourselves available to participate in these atrocities. It was painful, criminal and outrageous.

And we were dedicated not simply to avoiding conscription into the Vietnam debacle but to protesting against it in any way we could.

It quickly became my mission as a daily news reporter to make the readers of the Hartford Courant eat the war for breakfast every morning with their cereal and coffee. I covered anti-war demonstrations and interviewed anti-war protestors as much as I could, often at Yale University in New Haven, a hotbed of Vietnam War resistance. I tried to find novel ways to approach war issues, like my interview with the Yalie heir to the Pillsbury Foods fortune who used his clout as a stockholder in companies making profits from the war to pressure them to change their policies. When Students for a Democratic Society held their convention at Yale around Christmas I lambasted them in print for their disorganization and internecine power struggles, which had rendered them impotent as an effective anti-war power.

Barlow and I and other friends drove to Washington for the Nov. 15, 1969, Anti-War Moratorium, still believed to be the largest anti-war demonstration of all, with an estimated half a million protestors on hand -- almost as many people as attended the Trump Inaugural. We drove down from Connecticut in my VW camper van, with tunes like "Here Comes the Sun" blasting, joints and booze passing around, picking up hitchhikers along the way, usually hippie types, but also one clean-shaven dude in a pea coat who turned out to be a pharmacist’s mate in the U.S. Navy. He had pockets full of pills of many colors and seemed to know what they were for or might do. As the driver, I had to refrain, confining myself to weed and booze for safety’s sake.

It was a wild trip through Manhattan and suburban Philadelphia to see friends, and a bit like a bus as people got on or off. Most of us made the entire journey to D.C., where it was a joyous relief to be among so many like-minded souls, all demanding U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam, immediate cease-fire and peace. Lots of smiling faces and good vibes and right-minded women. Heartening to feel that our tribe of peace-lovers was so numerous and strong.

Another memorable field trip later that same month was up to Boston Garden to see the Rolling Stones. Thanks to friendly connections we had good seats. B.B. King opened and he was truly incredible. We didn’t really want him to stop. But then the Stones tore the place apart, with lots of their hits up to and including “Let It Bleed,” another album we imbibed incessantly in our Connecticut summer/winter hideaway. At one point someone lifted a dwarf up on to the stage, long-haired and decked out like the rest of us, who had no arms or legs. His handlers leaned him against a Marshall amp. As Jagger danced and pranced up to and around him, and Keith Richards drifted often near the ecstatic fellow in apparent homage, making him part of the act. Also, in the audience, 15 or 20 rows back from the stage was a nearly seven-foot-tall man perfectly garbed as Abraham Lincoln.

The energy at Boston Garden that night was electric, kicking off the tour that would end in disaster weeks later in Altamont, California, where Hell’s Angels acting as “security” beat a man to death as Mick Jagger watched in horror from the stage. The documentary by the Maysles brothers, “Gimme Shelter,” is a spellbinding account of that tour and its tragic climax, that seemed in some ways invited by the Stones’ anarchic energy. The love-and-peace honeymoon between Woodstock in August and Altamont in December was brief indeed.

Barlow was supposed to be working on a novel he had started at college. Thanks to his Pulitzer Prize-winning mentor, novelist Paul Horgan, Farrar, Straus and Giroux had optioned Barlow’s partial manuscript for a thousand bucks, to be completed ASAP. In Barlow’s mythic memoir, he claims his option money was $5,000. But Barlow’s style was hyperbolic at the soberest of times. His bona fide accomplishments never seemed quite enough (to him) to impress people. So he gilded the lily at almost every turn. Thus his inflated novel option comes out to five times its actual amount. Maybe he believed it. One friend told him he needed a hyperbolectomy, which made Barlow laugh.

In his “fictionalized memoir” (is there another kind?), he claims he took “a thousand acid trips.” But even Barlow’s avowed good friend Timothy Leary probably never got close to imbibing that much, and he started years before JPB. Such consumption would require an acid trip almost every week for 20 years, or two a week for 10 years, a physiological improbability to put it mildly. Barlow makes other casual claims that ought to be marked in the text with HA! — short for Hyperbole Alert — such as being student president at a college that had no such office. Barlow was well aware of his tendency but did not think of himself as a liar, merely a fabulist. Caveat lector!

The trip to India had rearranged Barlow’s psyche. He was no longer the man who had written the opening chapters of a novel to which he could not now relate. Having no idea how to resolve that problem, Barlow embraced every possible distraction. For no good reason he came along to an interview I had with the author Norman O. Brown. And he consistently took his own drug consumption level one step beyond, shooting methedrine instead of taking it orally like the rest of us. He would boogie through an entire Taj Mahal concert or ride his BMW like a bat out of hell, letting the wind blow through his brain. He had been counting on early novelistic success to propel him forward on his quest for legendary status. Coming to terms with that impossibility must have been difficult for him, but he would soon find other venues in which to shine.

The long snowy winter made the summer cottage appear to float in a deep white vacuum. All the seasonal restaurants and stores were closed. No plow removed snow from the roads leading to our lost suburb. Marooned though we were, the party continued through the profligate winter into spring, when the melting snow turned the earth around us muddy and there came a reckoning of sorts. Feeling shell-shocked and feverish, having had my fill of what had become a grim psychic experiment, I quit my job and went to visit a woman I knew in a far-away place. So I was not on hand the day the landlord showed up.

When Barlow and others had asked me what kind of doctor he was, I’d said he was probably a dentist. That’s what he looked like to me, though I really had no idea. It turned out he was a psychiatrist. I was out of the country when the good doctor dropped by to visit his summer place. But the house was far from empty, or quiet, thanks to King Crimson. He must have been surprised to see several cars in the drive he didn’t recognize, along with a very large motorcycle. He called out my name, causing panic. The most urgent need was to remove all illegal substances from sight. One of our friends met the man outside in front of the house to stall his progress. Learning he was the landlord and believing him to be a dentist, our friend proceeded to open his mouth and ask about a troublesome wisdom tooth.

Puzzled and not pleased, the doctor hurried inside, where another of our friends dove on the couch and wrapped himself in the Nazi flag, though its identity probably did not escape the notice of this Jewish shrink. He also began to realize that, beneath the pile of filthy rubble in the kitchen sink and the strange “art” hung on the walls in place of his own kitschy souvenir collection and the slovenly rubble strewn in every corner, some furniture appeared to be missing.

He looked quickly into both messy bedrooms then hurried out behind the house, where another friend was trying to straighten up. At the sight of the doctor, this friend approached him pointing to his open mouth and mumbling an incoherent plea for advice. Red-faced and shaking with rage, but clearly outnumbered, our landlord beat a hasty retreat, out to his car and down the road, as full-blown panic set off a frenzy of people scooping up forbidden items, stuffing them into car trunks and back seats and driving quickly away.

Of course, Barlow overcame this minor setback on his otherwise upward trajectory toward his destiny. He would write lyrics to Dead songs, marry and have children, rub shoulders with the famous, declare cyberspace free and independent, help found several organizations promoting that freedom, become a Harvard Fellow and TED talker, divorce and find true (if doomed) love and generally morph into the legend he had always wanted to become.

Though a prolonged old age was sadly denied him, Barlow did enjoy decades as a sage. And his digital afterlife will no doubt live long and prosper. The breadth and depth of his obituaries, from the New York Times to the Guardian, from the Economist to Rolling Stone, and in various tech magazines, show that he succeeded in his ambition.

But there was one genuinely horrific bit of blowback from our winter on the north shore of the Sound. Our psychiatrist landlord -- always looking for more income -- worked for the Draft Board, vetting candidates for military service who seemed to have psychiatric problems. As we later learned from friends, the doctor inevitably asked these potential draftees, most all of whom were hoping to evade the clutches of the military machine, whether or not they knew Barlow or me. If they did, their interview ended abruptly and they were declared 1-A prime rib, ready to serve.

Though Barlow and I survived our time together and our self-imposed disorientation, others may have paid dearly for our careless pleasures.

And for that, and that only, I am sorry beyond words.

Jerry Garcia: The anti-celebrity celebrity

Why our selfie culture needs the Grateful Dead

Will Silicon Valley’s new company towns end up as failed utopias?

AP

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Willow Village is a community planned for a 59-acre site in California’s Silicon Valley, between Menlo Park and East Palo Alto.

It will have housing, offices, a grocery store, a pharmacy, and its developers say, maybe even its own cultural center.

There’s one notable thing about Willow Village that makes it different from other new communities in America: It is being developed by Facebook.

Willow Village evokes “company towns” of the past, once built by corporations to both house and keep tabs on employees. And projects like Willow Village also follow the legacy of utopian communities in the United States.

American history is filled with towns, conceived and built to realize specific theological worldviews, at times linked with faith in capitalism and the power of technology. Like these utopian communities, Willow Village speaks of its founders’ desire to correct imagined social problems by reinventing social life.

But those earlier utopian communities and company towns foundered, either from labor strife or lack of leadership. Will the same thing happen to Facebook’s experiment in designing and building a community?

And considering the many recent controversies Facebook has had with its social network, do we want them controlling our physical environments, too?

Improving on human nature

I am a scholar who has researched digital culture. As I’ve argued elsewhere, social media companies often position their projects as socially beneficial, as if human nature could be perfected through engineering and planning.

Juan Salazar, a Facebook public policy manager, claims that Facebook’s goal for Willow Village “is to strengthen the community”: “We want a more permeable relationship, where we engage more. The parks, the grocery store, are places to congregate together, to build a sense of place.”

Salazar’s comment implies that, without Facebook’s corporate engineering, these spaces for community would not exist on their own, or at least can be improved by corporate intervention. Planning, policy and even some government functions, then, would be transferred from democratically elected officials to private corporations.

Facebook proposed Willow Village in 2017 as a redevelopment of the former Menlo Science & Technology Park. Initially named the “Willow Campus,” Facebook’s community, which will include 1,500 apartments, is a response to the exorbitant cost of living in Silicon Valley. The median home price in the San Jose metro region in 2017 was US$1,128,300.

Willow Village is one of a number of planned communities that tech firms want to build to provide housing, primarily for their own employees.

Google plans to build between 5,000 and 9,850 homes on its property in Mountain View, near Menlo Park. Google’s community will include retail stores and entertainment.

Consequences questioned

There are many criticisms of these plans.

As The New York Times has reported, Willow Village will most likely displace a largely Hispanic community, one of the poorest in Silicon Valley.

Plans like Facebook’s and Google’s evoke cities and neighborhoods built by, for instance, railroad magnate George Pullman or chocolate tycoon Milton Hershey. While envisioned as communities with “no poverty, no nuisances, no evil,” in Hershey’s words, these cities in fact were characterized by strikes, private police forces and bloody clashes between workers and management. Similar stories can be told of other company towns, such as Gary, Indiana, or Lowell, Massachusetts.

Silicon Valley has long been hostile toward organized labor. This leads to concerns that Google and Facebook’s new communities could engage in versions of the anti-labor practices of company towns throughout history, updated to include digital surveillance and technological means of control.

Will connecting solve problems?

Company towns have never lived up to their mission of social perfection.

Yet Facebook and Google, like many tech companies, say their purpose is socially beneficial. John Tenanes, Facebook’s vice president for real estate, told The New York Times, the apartments in Willow Village “are a starting point.” He added, “I would hope we could do more. We’re solving a problem here.”

While this quote seems innocuous, it reflects what critic Evgeny Morozov has termed “solutionism.” The goal of solving problems isn’t the problem. Rather, it’s that technological solutions circumvent governmental institutions.

Says Morozov: “We are abandoning all the checks and balances we have built to keep our public officials in check for these cleaner, neater, more efficient technological solutions.”

Specifically, social media companies often frame social problems as a lack of connectivity, which can be solved with technologies designed to foster social interconnection. In my research, I’ve followed how attitudes toward social connection have changed over time in American history.

As I charted this history, I found that this perspective draws on beliefs that emerged in the wake of the Great Depression. Prior to the Depression, social, technological and economic connectivity were feared by many Americans as a socialist means for restricting individual freedom. In a nutshell, connection meant organizing, which meant socialism.

It was only after the Depression that networked connection became widely imagined as a solution to a range of social ills.

But social connectivity was not always feared. Willow Village shares an outlook with other, much earlier, planned communities: A utopian worldview has been central for countless communities and towns founded across America in the 1800s. These towns were precursors of the larger, post-Depression embrace of connectivity. Many of these communities were isolated reactions against capitalism, founded with socialist guiding principles.

This isn’t to suggest that all of these communities were socialistic, however. A community closer to Willow Village can be seen in the model of the Oneida community in upstate New York, where capitalism was central to its utopia and was a way of distributing Christ’s energy to others, via the market.

Most of these utopian communities failed. Whether because of internal disputes over religious orthodoxy or money, few managed to last longer than a few years. Most that did endure only did so until their founder’s death. Without an authoritative social vision, the community fell apart.

So there’s been a long history in which social vision is shaped into ways of planning and living in America. The actual existence of these communities, however, has been marked by struggle and conflict.

The modern utopian community

In my research, I’ve argued that connecting via social media and circulating personal information is imagined as a means to achieve a kind of spiritual perfection today. Being connected to Facebook at all times, not just via their platforms, is imagined by those in Silicon Valley – sometimes implicitly, sometimes explicitly – to have an intrinsic social benefit.

Given how these visions are now shaping the planning of actual communities, this can be thought of as a reinvention of citizenship – and not metaphorically.

Facebook and Google are proposing, and occasionally entering into, partnerships with local governments, taking over numerous tasks once the responsibility of elected officials. This includes not only dictating housing policy, but also, for example, funding the police. Social media corporations are working to act in the roles once held by the state and government.

The threat is not that this is new. The legacy of company towns, for instance, tells us that corporations have often tried to subvert democracy with their own “governmental” agencies.

The problem is that this model now reflects a view popular in Silicon Valley that sees tech companies as progressive agents solving problems beyond governmental oversight. This worldview, in part, descends from the long history of utopian communities.

We will most likely see more of these projects and partnerships. But here’s the catch, and the threat: When they do this, elected officials cede power to companies that are not, like them, democratically accountable.

Grant Bollmer, Assistant Professor of Communication, North Carolina State University

Top Trending

Check out what's trending in the news right now.

Brian Eno’s Oblique Strategies: the famous deck of cards behind “Another Green World”

WIkimedia/Bloomsbury Publishing/Salon

Excerpted from “Brian Eno’s Another Green World” by Geeta Dayal (Continuum, 2009). Reprinted with permission from Bloomsbury Publishing.

"Another Green World" is the first Eno record which credits “Brian Eno,” not the otherworldly, vaporous “Eno’’ he had been referred to on previous records. It’s also the first Eno album that gives an explicit credit to the Oblique Strategies cards on the back cover sleeve.

Eno and his artist friend Peter Schmidt released the Oblique Strategies cards in 1975, when they realized that they had both been independently developing sets of ideas to help themselves come up with creative solutions to trying situations. “The Oblique Strategies evolved from me being in a number of working situations when the panic of the situation—particularly in studios—tended to make me quickly forget that there were others ways of working, and that there were tangential ways of attacking problems that were in many senses more interesting than the direct head-on approach,” explained Eno in an interview with Charles Amirkhanian in 1980.

The most clear antecedent to the Oblique Strategies cards was John Cage’s adoption of the ancient Chinese divination system, the I Ching, to make musical decisions. Some other related concepts to the Oblique Strategies were the Fluxus movement’s fanciful and inventive “Fluxkits” and Fluxus boxes—one particularly inspired example of these boxes, by George Brecht, was called the “water yam” box. The boxes often contained cards with witty sayings or specific instructions.

Another possible predecessor to the Oblique Strategies cards was the media theorist Marshall McLuhan’s “Distant Early Warning” cards, issued in 1969. Some of McLuhan’s cards, which were printed on a regular deck of poker cards, had quotes from other thinkers (one card read “Propaganda is any culture in action”—Jacques Ellul); others had classic McLuhan quotes (the ten of diamonds read “The medium is the message”); a king card read “In the world of the blind, the one-eyed man is a hallucinated idiot’’; the nine of spades sported the ominous warning “With data banks we are taped, typed and scrubbed.”

Cage’s I Ching methodology was graceful and complex, and McLuhan’s Distant Early Warning cards bordered on plain goofy—almost like fortune-cookie fortunes from some bizarro media-studies universe. The Oblique Strategies cards, meanwhile, had a specific, utilitarian purpose. The quirky cards were designed to help artists and musicians get out of creative ruts and loosen up in the studio. Each Oblique Strategy had a different aphorism: “Accept advice,” read one. “Imagine the music as a series of disconnected events,” read another. “Humanize something free of error.”

Percy Jones had strong memories of the Oblique Strategies cards being shuffled and drawn during the recording sessions on various occasions. “The first time he did it, I thought we were going to have a game of poker or something,” Jones said, chuckling. “I had no idea what was going on.”

While the cards could be useful tools, the instructions on the cards were indeed followed to the letter—sometimes with potentially disastrous results. “If the cards foretold that something had to be erased or turned upside down, they were,” said Barry Sage. If a song was being worked on intensely, and a card that was drawn suddenly proclaimed that the tapes had to be deleted, they were.

Eno’s playfulness in the studio was key. “My quick guide to Captain Eno: play, instinct/intuition, good taste,” wrote Robert Fripp in an e-mail. “Eno demonstrated his intelligence by concentrating his interests away from live work; and his work persists, and continues to have influence. The key to Brian, from my view, is his sense of play. I only know one other person (a musician) who engages with play to the same extent as Brian. Although Eno is considered an intellectual, and clearly he has more than sufficient wit, it’s Brian’s instinctive and intuitive choices that impress me. Instinct puts us in the moment, intellect is slower.”

Eno is popularly characterized as a brainy studio boffin, an egghead theorist and solemn architect of “sonic landscapes”; meanwhile, his friends and collaborators describe him as lighthearted and fun to be around, with a relaxed, anything-goes attitude—both in the studio and in life. How to reconcile these two poles? Leo Abrahams, who worked with Eno on a number of recent recording projects, said that he’d observed Eno working on two different levels. “When I see him work on things that are on the more ambient levels of what he does—like the album "Neroli" or certain things that were on his last record, or the J. Peter Schwalm stuff—that’s when you’d almost see that reputation of the boffin, if you like, being justified, because there are certain things he knows how to do with instruments and effects that nobody else knows how to do,” Abrahams said. “It’s amazing watching him fashion that; I think that’s a lot closer to his visual work, which again is extremely painstaking. But then again, when I see him working on songs–more song-based records—he’s really hands-on, and not at all precious about sounds. He likes things to be distorted and he likes things to sound really rough, and he does lots of things that an engineer will say ‘That’s wrong, you can’t do that!’ He likes to sing with the speakers blaring out, so you hear the music in the background of all the vocal tracks and stuff, just because he doesn’t like using headphones. It’s a deceptively slapdash approach, if you know what I mean. It’s quite rock and roll, and it’s not what you’d expect from the person who made things like "Music for Airports" or "77 Million Paintings." A similar thing was said by Rhett Davies; he described to me a few of the situations of what it was like in the studio, and it just sounds like a huge amount of fun, basically, and very experimental and not so boffin-esque and not so painstaking.”

Eno mixed it up in the studio at around the time of "Another Green World" in other ways. “Sometimes you’d be into something really intense, you’d be working on a piece of music and discussing it, and then he’d say: ‘Anybody want some cake?’” said Percy Jones. “Eno would pull out a cake and he’d cut up slices of cake, and everyone would eat some cake, and then we’d forget all about the creative process!”

David Bowie's pop culture legacy

The Brooklyn Museum exhibit “David Bowie is” follows the multi-faced Bowie through every phase of his career

“I am not food correct,” says Eddie Hernandez, chef and author of “Turnip Greens & Tortillas”

Angie Mosier

I’m a born again Southern boy.

I live in a city where I can listen to a bluegrass band on one night, and on another night I can go hear the blues. During football season I cheer for my two home teams — the UGA Bulldogs and the Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets — except when they play each other, and then I am a Tech fan all the way.

When I have a few days off, one of my favorite things to do is take a long, slow drive on the back roads of rural Georgia, along the bayous of Louisiana, or through the mountains of Tennessee. Wherever I go, I stop at every little café and roadside stand I can to try the fried chicken, the barbecue, the boudin sausage, or whatever it is the locals eat. As I taste, I start to get ideas about how I would recreate them — my way. In Nashville I try the famous hot fried chicken at a place called Hattie B’s and think how it would taste cut into strips and wrapped in a tortilla together with lime and jalapeño mayonnaise and shredded lettuce to cool the spice.

So what if it doesn’t work out? I will try it again until I get it right, or I will move on to the next thing. That is how I educate myself. I am not afraid to fail. Since I was a boy, I have always loved to figure out how to take things apart and put them back together — whether it was a truck engine or a tamale.

I have no family photographs to show because my family didn’t own a camera. We didn’t keep scrapbooks. I only have my cooking to trigger the memories. I was born in Monterrey, Mexico, one of the largest cities in the country. It lies in the foothills of the Sierra Madre Oriental about 115 miles from the Texas border. We lived in a working-class neighborhood of cement-block houses occupied by big families — up to thirty people. Every morning as we kids walked to school — we walked pretty much everywhere — there would be five, ten, fifteen moms out sweeping the streets, criticizing our wardrobes.

“Why are you wearing that shirt?” “I hope you changed your socks!”

My mother fed our family home-cooked food every day. We had lunch between twelve and one, and dinner between six and seven. Always. If you weren’t there, you would either have to heat your meal up yourself, if there was anything left, or go hungry. The other kids and I did our share of arguing and fighting, but never at the table. That was our time to sit down together in peace.Everything we ate was fresh. No one had gardens in my neighborhood, other than maybe some herbs or chiles in pots, because it was the big city and there wasn’t space. Instead the mothers went to the market every day. They bought what looked good to them and was a good price.

Our markets were nothing like the mainstream supermarkets in the U.S. They were more like open-air farmers’ markets with butcher shops, bakeries, and stalls filled with tomatoes, fresh corn, avocados, peppers, cabbages, zucchini, mangoes — you name it. Living in a climate that rarely dips below 70 degrees, even in winter, we were used to having access to a huge assortment of fresh produce year-round. Most people didn’t have refrigerators in their homes, and in poor rural areas, that’s often still the case. Electronics had to be imported and were very expensive. My family was fortunate enough to have those appliances. We even had a blender! But we still shopped daily. It was our way of life.

My dad was a mechanic. He worked on a steam engine in the railyard, and I watched him with fascination. He wore suits every day to work and came home covered in diesel oil, looking like he just crawled out of the earth. After he showered, he would put on a fresh suit and go out looking like a million bucks. I was nine when he died.

I lived with my mother and grandmother, neither of whom had a husband. Then my stepfather, Leonardo, came into the picture. And when he and my mother had kids — five of them — I couldn’t help feeling neglected. I started to make my own course in life.

My mother’s brother was like a father figure to me. Uncle José taught me mechanical skills like welding, bolting, and painting cars. He also taught me a lot about food. We ate things no one would eat but us — like goats’ brains. He would buy whole pine nuts for us to crack and eat.

He never bought them shelled because he thought it was more fun to crack them ourselves. When I got older, we liked to drink and listen to music together. But it was my grandmother who gave me the desire to learn to cook. Her name was Consuela, but everybody called her Chelo. She was a strong-willed entrepreneur who owned seven different bars and convenience stores around Monterrey. One place was three doors down from where we lived. It didn’t have a name. Everyone just knew it as Chelo’s place. As a kid I hung out there.Nobody messed with Chelo.

She was a big woman, at least 5 foot 8, with blond hair and blue eyes. Her voice could make grown men run. We used to joke that she’d never die because neither God nor the devil would take her. She knew how to handle all kinds of situations. But whenever she raised her voice to me, I raised mine back. I think she liked that. We respected each other.

I’m not going to say Chelo was a chef, because back then there was no such thing as a chef. Everybody just cooked. Guys who would go to her pub for a beer liked the fact that they could get a good meal and free homemade snacks there. She was big on fresh food, and she never made the same things two days in a row. I loved watching Chelo cook things that I had never seen anyone else make. Pickled pork skin was one of my favorites.

In Mexico it’s a good bar food and a side dish for tacos. I would ask her to make some just for me. But she would say, “If you want to eat it, then learn how to make it yourself, because I’m not going to be here one day and who is going to cook it for you?” And so I learned, and eventually became pretty good at it. I taught myself to drive a truck when I was twelve, and Chelo would send me to the market to pick up groceries.

I got my first job delivering newspapers when I was thirteen, and when I was fifteen, I bought a car and opened a torta stand on the street. I made a pot of carnitas — pork meat simmered in oil until tender — and served it on bread three different ways: with cold salsa made with tomatoes and chiles; with cooked salsa; and plain, with just some chopped avocado. It looked fancy but it was as simple as could be.

Recipe for chicken green-chili potpie in puffy tortilla shells

Many customers have told me this is the best potpie they’ve ever tried. The creamy chicken and vegetable filling, punched up with sour cream, fresh thyme, and jalapeños, is hard to beat. But what really makes it memorable is the presentation. Instead of a traditional crust, I drop flour tortillas one at a time into hot oil for just a minute, long enough for them to puff up and turn golden brown. Then I carefully crack the tops open and spoon the filling in. I recommend using La Banderita tortillas, as they are a little thicker than other brands and puff up better. If you don’t want to mess with the hot oil, you can substitute baked puff pastry shells or even hot biscuits for the tortillas.

1 (3-pound) chicken, cut into pieces

1 tablespoon plus 1 teaspoon salt

3 tablespoons butter

1½ cups chopped carrots

1 cup chopped onions

1 cup chopped celery

2 jalapeños, stemmed and minced (remove some or all of the seeds and membranes for less heat)

1 tablespoon minced fresh thyme leaves

¾ teaspoon minced garlic

2 cups heavy cream

1 cup sour cream

1 cup grated white American cheese

3 to 4 tablespoons Blond Roux (below)

2 cups frozen peas, thawed

8 (6-inch) flour tortillas, such as La Banderita

Vegetable oil for frying

½ cup roasted, peeled, stemmed and chopped jalapeños (remove some or all of the seeds and membranes for less heat) (or use canned Ortega)

Place the chicken pieces and 1 tablespoon of the salt in a large pot, cover with water, and bring to a boil.

Reduce the heat to maintain a simmer and cook just until the chicken is tender, about 30 minutes.

Remove the chicken from the pot and cool slightly. Reserve 2 cups of the stock for the gravy. Remove and discard the skin and bones. Shred the meat and set aside.

Melt the butter in the pot over medium heat. Add the carrots, onions, celery, jalapeños, and remaining 1 teaspoon salt and cook, stirring frequently, for 5 to 7 minutes, until the onion is translucent. Add the thyme and garlic and cook for 1 minute. Add the reserved stock, cream, and sour cream. Bring to a boil and cook for 2 minutes. Stir in the cheese and cook until melted.

Lower the heat to medium. Stir in 3 tablespoons of the roux, and simmer, stirring frequently, for 3 minutes. Stir in a little more roux if needed until the mixture reaches the desired thickness. Add the shredded chicken and the peas, lower the heat, and simmer for 3 minutes. Taste and adjust the seasonings as desired. Keep warm.

To make the puffy tortillas: Line a platter with paper towels. Heat 1 1/2 inches of oil in a Dutch oven or other large, heavy pot over high heat to 400 degrees. Add the tortillas, one at a time. Let each cook for about a minute, until puffed up and lightly browned, spooning oil over the top as they cook (do not flip). Remove to the paper towel–lined platter to drain. Allow the oil to return to 400 degrees between each tortilla.

To serve, poke a hole in the top of each tortilla, ladle 1 to 1 1/2 cups of the chicken mixture into the hole and garnish with the roasted jalapeños.

Blond Roux

Makes about 1/3 cup or enough to thicken 1 quart of liquid.

I like sauce and gravy—and lots of it. You can thicken sauces and gravies with a paste of flour (or cornstarch) and cold water, or make a beurre manié the way the French do, by blending softened butter and flour with your fingers or a spoon, and stirring in bits at the end of the cooking. You have to be very careful with the methods, though, because if you don’t cook the sauce long enough, it will have a raw flour taste. But you will never have this problem if you make a blond, or white, roux, as cooks do in Louisiana. In a blond roux, the butter and flour mixture is cooked, and it thickens without imparting much flavor and with little risk of lumps forming. Unlike the more time-consuming dark roux used for gumbo, this cream-colored roux is hard to mess up and takes only a few minutes to make.

4 tablespoons (½ stick) unsalted butter

6 tablespoons all-purpose flour

Melt the butter in a small saucepan set over medium heat. Add the flour all at once and whisk vigorously until smooth. When the mixture thins and starts to bubble, reduce the heat to low.

Cook for 1 or 2 minutes, whisking slowly, until the mixture smells nutty and toasty and is still lightly colored. Cook for 2 more minutes, stirring occasionally.

Cool at least to room temperature before adding to hot liquids. The roux stores well, tightly covered, in the refrigerator for up to 1 month.

For 1 cup roux: 12 tablespoons butter and 1 cup plus 2 tablespoons all-purpose flour (Thickens 3 quarts liquid.)

For 1/4 cup roux: 3 tablespoons butter and 4 tablespoons plus 2 teaspoons all-purpose flour (Thickens 3 cups liquid.)

Excerpted from "Turnip Greens & Tortillas," © 2018 by Eddie Hernandez & Susan Puckett. Reproduced by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. All rights reserved.

Top Trending

Check out the top news stories here!

After Janus, should unions abandon exclusive representation?

Getty/Phillip Nelson

This article originally appeared in In These Times

The Supreme Court is set to issue a ruling on Janus v. AFSCME, which could have far-reaching consequences for the future of public-sector unions in the United States. The case has sparked a wide-ranging debate within the labor movement about how to deal with the “free-rider problem” of union members who benefit from collective bargaining agreements but opt-out of paying dues. We asked three labor experts to discuss what’s at stake in the case and how they each think unions should respond.

Kate Bronfenbrenner is director of labor education research at Cornell University, Chris Brooks is a staff writer and organizer with Labor Notes and Shaun Richman is a former organizing director at the American Federation of Teachers.

Chris Brooks: The way I see it, right-to-work presents two interlocking problems for unions. The first is that unions are legally required to represent all workers in a bargaining unit that the union has been certified to represent, and in open shops the Duty of Fair Representation (DFR) requires unions to expend resources on non-members who are covered by that contract. This is commonly known as the free rider problem and it gets a lot of attention, for good reason.

The second problem is that open shops also undermine solidarity by pitting workers who pay their fair share to support the union against those who do not. This is the divide-and-conquer problem.

So the free rider problem is institutional: the union has to expend all these resources fighting on behalf of workers who are not members and do not pay dues. And the divide-and-conquer problem is interpersonal: when workers do not all support the union this results in union and non-union members developing adversarial attitudes toward each other which undermines the ability for collective action.

If you believe that the source of a union’s strength is its ability to unite workers in common fights to better their conditions on the job and in the community, then the divide-and-conquer problem is a real impediment to union power. Yet, the free rider problem gets far more attention from union leaders and activists than the divide-and-conquer problem. This is especially true in the discussion around whether unions should ditch exclusive representation and pursue a members-only form of unionism.

In my opinion, most arguments in support of kicking out free riders actually reinforces the employers' logic — turning union membership into a personal choice and unions themselves into competing vehicles for individualized services rather than vehicles for broad class struggle. So by focusing on the free rider problem to the exclusion of the divide-and-conquer problem, unions run the danger of turning inward and representing a smaller and smaller number of workers rather than seeking to constantly expand their base in larger fights on behalf of all workers in an industry.

Shaun Richman: I had an article published in The Washington Post and I admit it was too cute by half partly because I was trying to amplify what I think was actually the strongest argument that AFSCME is making in the case itself, which is that the agency fee has historically been traded for the no strike clause and if you strike that there is the potential for quite a bit of chaos. So I wanted to put a little bit of fear to whoever might potentially have the ear of Chief Justice Roberts, as crazy as that may sound. But I also wanted to plant the seed of thinking for a few union rebels out there. If the Janus decision comes down as many of us fear then the proper response is to create chaos.

If the entire public sector goes right to work, unions will never look the same. So, then, the project of the left should be “what do we want them to look like?” and “what will drive the bosses craziest?” I've written about this before and Chris has responded at In These Times. There are three things that I am suggesting will happen — two of which, and I think Chris agrees, are sort of inevitable and not particularly desirable. The third part is not inevitable and depends a lot on what we do as activists.

If we lose the agency fee, some unions will seek to go members-only in order to avoid the free rider problem, and that's a lousy motivation. I'm not encouraging that, but I think it's also inevitable. Once you have unions representing these workers over here but not those workers over there, it's also inevitable that you wind up with competitor unions vying for the unrepresented. And the first competitor unions are going to be conservative. These already exist. They're all over the South and they compete against the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) and National Education Association (NEA) in many districts and they offer bare bones benefits and they promote themselves on “we're not going to support candidates who are in favor of abortions and we'll represent you if you have tenure issues.” That's also bad but also inevitable.

The third step, which is not inevitable but we need to consider in this moment, is at what point do new opposition groups break away from the existing formal union? When do we just break the exclusive model and compete for members and workplace leadership? Can we get to a point where on the shop floor level you've got organizations vying for workers' dues money and loyalty based on who can take on the boss in a better fight or who can win a better deal on the basis of we're going to be less confrontational (which, I think, there are a lot of workers whom that appeals to as much as I don't like that idea)? But the chaos of the employer not being able to make one deal with one union that settles everything for three or five years — that's just the sort of chaos that the boss class deserves for having pursued this whole Friedrichs and now Janus strategy.

Kate Bronfenbrenner: I have a different perspective that has to do with having looked at this issue over a longer period of time and also having witnessed the UK labor movement wrestle with exclusive representation when their labor law changed. First, I believe there is a third thing that right to work does that is missing from your analysis. Right to work gives employers another point to intimidate, coerce, and threaten employees about being part of the union, all of which employers find much more difficult to do in a union or an agency shop.

My research suggests that employers will act the same way now they do in the process of workers becoming members as they do during an organizing drive. The historical trade-off for unions was that the price of exclusive representation was Duty of Fair Representation (DFR) and unions saw DFR as a burden.

Those of us who were progressives saw that Duty of Fair Representation was the best thing that ever happened to unions because DFR said that unions had to represent women, people of color, the LGBT community, and you couldn't discriminate against part time versus full time. Historically it was used to force the old guard had to give up domination of unions and to fight for for union democracy because the simplest basis of DFR is the concept of good faith. If used effectively it would be the thing that could break the hold of the mob, or the old guard, or just white men. So you have to remember when you give up exclusive representation you could lose DFR. I can tell you that women and people of color are not going to want to give it up. And I think the fact that the two of you didn't think of that is probably because you have not been using that in your roles, but it is central to those who are fighting if you are dealing with members who are fighting discrimination in your union, the whole DFR exclusive representation is absolutely critical.

Brooks: Kate, am I wrong that the actual court case establishing the DFR in exclusive representation comes out of the Railway Act, where a local was refusing to represent Black workers?

Bronfenbrenner: Historically, but it kept being reinforced over and over again in cases involving most collective bargaining laws. It's been reinforced over and over again that the trade-off for exclusive representation that the DFR is tied with exclusive representation.

Richman: Yeah, it was the entire thrust of the NAACP workplace strategy before the 1960’s—that the labor law could be a civil rights act as long as we could win DFR. Herbert Hill wrote a great book about it ("Black Labor and the American Legal System"). I would also recommend Sophia Z. Lee's "The Workplace Constitution," which explores that history and makes a compelling argument for returning to a strategy of trying to establish constitutional rights in the workplace through the labor act.

Bronfenbrenner: Right. So union workers had protection for LGBTQ workers under DFR long before any other workers did because you could not discriminate on the basis of any class under duty of fair representation. Now whether workers knew that, whether their unions would represent them, is another matter but if you were a union worker or a worker who knew about it, this was where you fought it. So that was very important.

And the third thing that I wanted to say that related to this was that there is a long history in the public sector of independent unions, of company unions, acting as if exclusive representation didn't exist, where there would only be one member and employers would recognize the “union” establishing a contract bar so no other union could come in.

In the 1980s and 1990s, public sector unions assumed that they were winning decertification elections rather than the independent unions and discovered that they weren't. Soon enough they realized that the problem was that they weren't doing a good enough job of representing their members. Workers were not voting for the company unions, which were little more than law firms or insurance companies. They were voting against the poor representation.

The prevalence of these independents is a long running problem that existed before and after exclusive representation, and it exists when there are agency fees and when there are not. Poor enforcement by the NLRB and the difficulty of tracking down these front groups that are not really unions is a much bigger issue that comes out of a divided public sector, and exclusive representation has nothing to do with it.

Brooks: I think right-wing groups are trying to capitalize on the history of company unions and fragmentation in the public sector. The State Policy Network (SPN) has a nationally coordinated strategy that builds on right-to-work laws to further bust unions. One of the tactics their member organizations, which exist in all fifty states, are pursuing is so-called “workers' choice” legislation. This legislation allows unions to maintain a limited form of exclusivity, but with no duty of fair representation. Unions must still win a certification election to be the sole organization bargaining with the employer, but workers can opt out of the union and seek their own private contract with the boss outside of the collective bargaining agreement.

Requiring a certification election for collective bargaining also saves employers from having a situation where multiple unions can simultaneously pursue separate bargaining agreements for the same group of workers, a legal can of worms that corporations don’t want to open. SPN affiliates tout this legislation as a solution to the free rider problem for unions, since they have no duty to represent non-members, but it also incentivizes employers to bribe and cajole individual workers away from the union.

Employers could offer bonuses to workers if they drop union membership and call it “merit pay.” I don’t think that corporate advocacy groups like the SPN would be promoting this legislation unless they believed it would further weaken unions and fragment the labor movement.

The SPN is also actively organizing these massive opt-out campaigns, where they encourage workers to “give themselves a raise” by dropping union membership. They even have a nationally coordinated week of action called National Employee Freedom Week that eighty organizations participate in. In fact, the SPN think tanks work hand-in-glove with a host of independent education associations — which are basically company unions, purporting to represent teachers while advancing the privatization agenda. In Georgia, Mississippi, Missouri and Texas, these independent education associations claim to be larger than the AFT and NEA affiliates.

So in those places where unions are really strong, there is a high likelihood that we will see an increase in company unions that are working closely with State Policy Network affiliates to further divide workers on the job.

Richman: Chris, what you're describing are things that are mostly going to happen anyway, if we lose Janus. That SPN opt-out campaign is going to happen. The legislation you describe is not inevitable. I agree we dig a hole for ourselves if the only reason we want to “kick out the scabs” is so we don't have to represent them in grievances. Because that lays the groundwork for making a union-busting bill seem like a reasonable compromise.

If we lose Janus, unions will never look the same. It's at moments like this when we have to critically evaluate everything. What do we like about unions and our current workers' rights regime? What don't we like and what opportunities has this created for us to at least challenge that?

For me, the opportunity is to think about having multiple competitive unions on the shop floor. I don't think of this as a model that will lead to multiple contracts. It might lead to no contracts. Everything that I've written on this subject so far has been with the assumption that ULP protections against discrimination remain in place so that the boss can't give one group of workers a better deal because they picked one union over another (or no union at all). If a boss makes a deal with any group of workers or imposes new terms because a union got bargained to impasse, everybody gets the same thing.

Under a competitive multiple union model, I think no strike clauses become basically unenforceable. And these no strike clauses have become really deadly for unions in ways we don't want to acknowledge. Currently, the workers who should be the most emboldened at work, because they're protected by a union, have a contract that radically restricts their ability to protest. It's not just strikes. It curtails the ability to do slow down actions, and malicious compliance, and it forces the union rep to have to rush down to the job and tell their members, you have to stop doing this. And they end up feeling bitter toward the union leadership as much — if not more — than the boss for the conditions that were agitating them still being in place. And then their "my union did nothing for me" stories carry over to non-union shops. Every organizer has heard them.

We need to bring back the strike weapon. And that's far easier said than done. But it's really hard to do when you're severely restricted in your ability for empowered workers to set an example for unorganized workers in taking action and winning.

And, Kate, I have considered the DFR. I can't imagine a world of multiple competitive unions in a workplace where there wouldn't be at least one union that says we're going to be the anti-racist union, we're going to be the feminist union, and we're the union for you. Without DFR, you’re right, there's no legal guarantees. But someone steps into the vacuum and my hope is that at least creates the potential for militancy when militancy is called for in the workplace. With all the other messiness.

There's going to be plenty of yellow unions and the boss is going to bring back employee representation programs and company unions and all of that. But that mess is exactly what they deserve. They've forgotten that exclusive representation is the model that they wanted — we didn’t, necessarily — in the 1940s and 1950s.

Bronfenbrenner: I wouldn't be ready to throw out DFR. I think that there is too little democracy, and too much discrimination in the labor movement. At this time, we already have right to work in most of the public sector and most of the public sector doesn't allow strikes, but workers still strike. We see that workers are willing to strike even if they are not allowed to strike, as evidenced by all these teachers, and we have to remember the strike statistics in this country only report strikes that are over 1,000 workers and most workplaces are under 1,000. We have a lot more strikes than are reported.

The labor movement is not going to strike more just because you get rid of no strike clauses. Teamsters had the ability to strike as the last step of their grievance procedure for decades and they never went on strike. I think what is more important is the question of what is going to change the culture and politics of the labor movement. I don't think changing the right to strike is going to do it.

What is going to make unions actually fight back even on something like fighting on Janus? They're not even getting in the streets on Janus, so what makes you think they're actually going to strike on issues in the workplace? We need to think about why workers and unions are so hesitant to strike. I do not believe that chaos necessarily is going to happen. I think employers are much more prepared for this. I think what will happen is that the unions that have been effective and have been working with their members and educating their members and involving their members will be fighting back and the ones that have been sitting back and not doing anything will continue to sit back and not do anything and some will die.

The problem with getting rid of exclusive representation is that some unions are going to think “aha this is what I'm going to do, this is an easy way out,” the same way people used to think "oh it's easier to organize in health care, oh it's easier to organize in the public sector, so rather than organize in my industry, which is hard, I'm going to go try health care or the public sector.” But they found that "why can't I win organizing teachers the same way that AFT does" or "why can't I win organizing in health care the same way SEIU is doing" and they discovered that it's not quite as easy as it looks.

Brooks: Yeah, I think Kate's point is really important: in a right-to-work setting, the employer anti-union campaign never ends. The boss is constantly trying to convince and cajole workers into dropping union membership. And employer anti-union campaigns are really effective, which is why unions don't win them very often.

If the Supreme Court rules against unions in Janus, anti-union campaigns are only going to gain strength. So, my fear, Shaun, is that you are being overly romantic. I just don't think left-wing unions are going to suddenly emerge and step into the void left by business-as-usual unionism. If that was the case, then why hasn't that already happened with the 90 percent of workers that don't have any union at all?

Richman: The structure is a trap, and exclusive representation is part of that. I don't think we have a crisis of leadership. I want to turn to the private sector because most of the potential hope in abandoning exclusive representation is in the private sector. Look at the UAW and their struggles at Volkswagen and at Nissan, which Chris is intimately familiar with. I think all three of us could find fault in their organizing strategy and tactics. Kate, I think you have more grounds than anyone in the country to be frustrated because you've scientifically proven what it takes to win and most unions have ignored that research for decades! But a third of the workers at Nissan want to have a union. To do so, they have to win an exclusive representation election where the entire power structure of the community comes down on their heads arguing keep the UAW out of the South.

If they had eked out an election win and managed to win a contract a year down the line, at the end of the day they get the obligation of having to represent everyone and probably the one-third of the workers who wanted the union all along are the only ones that join. That’s insane. Charles Morris threw out this theory a decade ago, in "The Blue Eagle at Work," about how the NLRA was not intended to have these winner-take-all exclusive representation elections. The point of the NLRA was merely to say to employers anywhere there's a group of workers that say hey we're a union you must bargain with them in good faith. He argues that pathway is still open to unions. To the best of my knowledge a few unions politely asked the NLRB for their opinion on that a couple of times rather than all of us demanding that should be a valid pathway for union representation.

If you can win that exclusive representation election, you should win it, and you should also be saddled with the burdens of DFR. But why can't, and why shouldn't, the UAW file a petition at every auto factory in the country right now and say we have members here and you need to bargain with us over their working conditions? And why shouldn't other unions jump into the fray and claim to represent their portion of the workers and drive those non-union companies nuts with a bunch of unions placing demands on them, and organizing to take action?

I think the work that Organization United for Respect (OUR) is doing at Wal-Mart is a good example of that. They by no means have a majority of the workers at Wal-Mart. They are in a few strategic locations. They are a nuisance to the company. They just won a right that workers are allowed to wear union buttons on the shop floor. Wal-Mart has given workers raises in response to their agitation. I'm not suggesting that that model is perfect or what we should all be doing, but I am saying that this should be an avenue open to us. And it only becomes open to us if we're willing to experiment more with abandoning exclusive representation where it doesn't work for us.

I would argue that in 90% of private sector workplaces where winning these elections is not possible it's not working for us currently.

Bronfenbrenner: The comprehensive campaign-organizing model should be part of every organizing effort. Workers are protected under the NLRA when they engage in concerted activity and, as I say in all my organizing research, the union should be acting like a union from the beginning of the campaign. Unions should also be organizing around workplace problems and going to the employer and engaging in actions during the organizing campaign. I've been saying for 30 years that you don't wait to start acting like a union until you win. But there is serious pushback against that element of my model from many organizers.

Unions are very hesitant to start taking on the employer before they win the majority. But there are unions that do that. It's not just OUR. It’s Warehouse Workers United, SEIU 32BJ, RWDSU, Communications Workers, the Teamsters. All have run campaigns where they begin taking on the employer before the union has been recognized or certified. The unions that have been doing comprehensive campaigns are doing it in bargaining and it's being done in organizing by the unions who are winning in organizing. So they're not waiting until they win.

Richman: Thirty or forty years into people getting really serious about organizing as a science and as a craft, the fact that most unions still haven’t embraced an organizing model. . .

Bronfenbrenner: People have been serious about organizing as a craft from the beginning. It's just that no one wrote very good books about what they did. The IWW and the UAW organizers, and the textile organizers, they were organizing using the same strategies that are being done now. No one wrote good books about what they did.

Richman: Sure, that's fair. But the fact that unions are not following an organizing model that’s informed by your research and other unions' best practices suggests it's not a matter of culture but the legal framework that we find ourselves trapped in. Most of the pressure on a union leader is to bring back good contracts for the members you currently represent and keep winning re-election. So that puts more resources into grievance handling and bargaining and it leads to the cost cutting in organizing campaigns.

Bronfenbrenner: I disagree. For the last three decades servicing and education budgets have been cut while huge amounts of the labor movement’s financial and staff resources have been shifted into labor law reform. And I can tell you because I'm part of the debate they don't want to have about what they they need to do to change to organize. But most either think they are doing everything they can, or it is too hard to do anything different. It is the law that is the problem.

Either way the shared understanding is that unions should put resources into politics and in getting labor law reform because trying to do comprehensive organizing campaigns we’re asking them to do is “too difficult.” But they're not putting resources into grievance handling anymore. They are putting it into politics and labor law reform.

Richman: The approach to labor law reform has been too much about trying to preserve the system. The opportunity of the moment is to think beyond the boundaries of the workplace. Enterprise level bargaining has been killing us since the 1970s. As long as union membership is tied to whether or not some group of workers voted to form a union sometime in the past within the four walls of your workplace, that just incentivizes the offshoring and contracting out that's really what has decimated the labor movement.

Humpty Dumpty is sitting on the wall and if Neil Gorsuch and John Roberts kick him off I am not particularly interested in being one of the king's horses and men trying to put him together again. At that point the system is fundamentally broken and we need new demands about what kind of system we want and new strategies about how we exploit the brokenness of the system to make them regret what they have done.

Exclusive representation — combined with agency fee and DFR — worked for a long time. But if you knock one piece out, it all falls apart. We shouldn't be pining for bygone days. We need to be thinking forward about what opportunities this creates. I hope that some people get inspired to try something as crazy as the IWW saying fuck it, we're going to organize in different workplaces and agitate for work slowdowns and try to gain a few members in a few places we don't care about expenditures of resources and dues. We're going to create some chaos.