Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 55

June 4, 2018

Voter turnout is everything

Getty/Kena Betancur

This originally appeared on Robert Reich’s blog.

The largest political party in America isn’t the Democratic Party or the Republican Party. It’s the Party of Non-Voters.

94 million Americans who were eligible to vote in the 2016 election didn’t vote. That’s a bigger number than the number who voted either for Trump or for Clinton.

All of which means that voter turnout will determine who wins control of Congress next November, and who becomes president in 2020. Turnout is everything.

This is why it’s so important for you to vote — and urge everyone you know to vote, too.

Top Trending

Check out the major news stories of the day

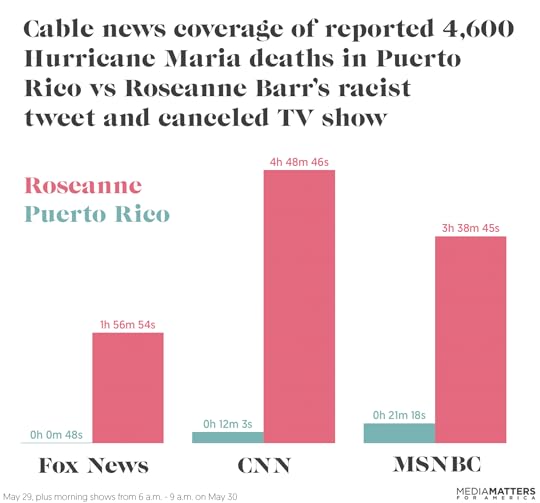

Study finds 5,000 people may have died from Hurricane Maria. Cable news focused on Roseanne

AP Photo/Carlos Giusti

This article originally appeared on Media Matters

On Tuesday, Harvard researchers published a study estimating that approximately 5,000 deaths can be linked to Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. The same day, ABC canceled Roseanne Barr’s eponymous show "Roseanne" after Barr sent a racist tweet about Valerie Jarrett, an adviser to former President Barack Obama. Cable news covered Barr’s tweet and her show’s cancellation 16 times as much as the deaths of U.S. citizens in Puerto Rico.

While the official death toll remains at just 64, the Harvard study, written up in The Washington Post, “indicated that the mortality rate was 14.3 deaths per 1,000 residents from Sept. 20 through Dec. 31, 2017, a 62 percent increase in the mortality rate compared with 2016, or 4,645 ‘excess deaths.’” BuzzFeed News, which also reported on the study, further explained that the researchers adjusted their estimate up to 5,740 hurricane-related deaths to account for “people who lived alone and died as a result of the storm” and were thus not reported in the study’s survey.

Cable news barely covered the report. The May 29 broadcasts of MSNBC combined with the network's flagship morning show the next day spent 21 minutes discussing the findings. CNN followed with just under 10 minutes of coverage, and Fox covered the report for just 48 seconds.

By contrast, cable news spent over 8 and a half hours discussing a tweet from Barr describing Jarrett, a Black woman, as the offspring of the Muslim Brotherhood and "Planet of the Apes" and the subsequent cancellation of her show.

Credit: Sarah Wasko/Media Matters

Media coverage of the crisis in Puerto Rico has been dismal since the hurricane hit; even when outlets reported on major scandals about the mismanaged recovery, the coverage was negligible and faded quickly.

Many in the media have been quick to label Barr’s obviously racist tweet as racist. But they've failed in their coverage of the mismanaged recovery in Puerto Rico, which is also explained — at least in part — by racism. The Root explained why “Puerto Rico’s crisis is not generally seen as a racial matter. But it should be.” Vox explained “the ways the island and its people have been othered through racial and ethnic bias” and noted that “both online and broadcast media gave Puerto Rico much less coverage, at least initially, than the hurricanes that recently hit Texas and Florida.” A Politico investigation found that “the Trump administration — and the president himself — responded far more aggressively to Texas than to Puerto Rico” in the wake of the hurricanes that devastated both. Trump tweeted just days after Hurricane Maria hit that Puerto Ricans “want everything to be done for them.” Only half of Americans are aware that Puerto Ricans are in fact U.S. citizens. And MSNBC contributor Eddie Glaude, chair of the Center for African-American Studies at Princeton University, pointed out, “When you think about 4,600 people dying — of color — dying in Puerto Rico, it reflects how their lives were valued, or less valued.”

Dina Radtke contributed research to this piece.

Top Trending

Check out the major news stories of the day

June 3, 2018

What corporate jet would Jesus buy?

Getty Images

It turns out that a televangelist who preaches that good health and financial prosperity go to the most devout of Christians isn’t asking his congregants to give him the money to buy a new $54 million corporate jet.

Instead, Louisiana televangelist Jesse Duplantis said in a video posted Saturday to his church website that he’s merely asking his followers to join him in “believing” that God will to grant him a Dassault Falcon 7X aircraft.

“I'm not asking you to pay for my plane,” Duplantis said in the video, as first reported by the New Orleans Advocate. “I’ve owned three planes. I don’t have four planes right now. I don’t have a fleet of planes. I have one plane and I’ve had it for 12 years, this one. And we’re giving this one away, because we believe in God for the 7X to come in.”

Duplantis is head of Jesse Duplantis Ministries, which operates out of a 21-year old church just west of New Orleans. His church produces a weekly televised broadcast and peddles books and CDs under self-help-y titles like “The Ministry of Cheerfulness” and “A Merry Heart Doeth Good Like Medicine.”

Though it has a following abroad, this brand of Christianity, known as prosperity theology, is a uniquely American phenomenon with roots in the emergence of Healing Revivals ministers in the 1950s America and the New Thought movement. Prosperity theologians are closely aligned and sometimes overlap with the beliefs taught through Charismatic Christianity, which promotes the belief in modern miracles such as healing through faith.

Leaders from various Christian denominations, including from within the Pentecostal community, have long criticized the theology as irresponsible and idolatrous. Secular critics abound and routinely accuse these ministers of exploiting religious belief for personal enrichment.

Prominent leaders of the theology include Robert Gibson Tilton, Joel Osteen, Creflo Dollar and Kenneth Copeland. Both Copeland and Duplantis have defended their use of multi-million-dollar corporate jets. Earlier this year Copeland thanked his supporters for making the purchase of a Gulfstream V possible and asking for $2.5 million to upgrade the plane for international flights.

Perhaps Duplantis, the mansion-dwelling head of his eponymous ministries, needs a new set of wings (or probably not) but 12 years is not a very long time to operate a corporate jet. According to French aircraft manufacturer Dassault, 85 percent of all Falcons ever produced since the first one rolled off the assembly line in 1965, are still flying. Maybe Duplantis should ask his congregation to pray that he stick with the jet he had and maybe give more alms to the poor; God knows there arte plenty of them in Louisiana.

Top Trending

Check out the top news stories here!

A brief history of American winemaking

AP Photo/Elaine Thompson

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

The American love affair with wine dates back to the earlier European settlers in the 16th century, when they began making wine with a native grape known as muscadine.

Today every state produces wine, though almost half of the more than 9,700 wineries are based in California.

While I don’t own a winery, I do tend to a small hobby vineyard and make my own garagiste wine. I also study the wine business. In honor of National Wine Day, here’s a primer on the history of the U.S. wine industry.

Settlers on the vine

When Spanish explorer Ponce de Leon arrived in what is now Florida in 1513, he was followed a half century later by Spanish and French Huguenot settlers, who began making muscadine wine.

Efforts to plant the great wines of Europe – known as Vitis vinifera or classic grapes – failed because their rootstock couldn’t withstand attacks from pests like phylloxera, which thrive in wet climates.

An interesting historical footnote is that Thomas Jefferson attempted to establish a winery and plant Vitis vinifera vineyards in Virginia in the late 1700s and early 1800s. He was, like the others, unsuccessful due to attacks of black rot and phylloxera.

But that didn’t stop wineries from popping up all over the East Coast and Midwest, including in Wisconsin, Ohio and New Jersey. Because of the threat of phylloxera, they used grapes that are native to the U.S. such as Concord and Niagara or hybrids like Catawba and Marechal Foch, as they still do today.

Brotherhood Winery in New York, for example, established in 1839 and the oldest continually operated winery in the U.S., continues to use some native American grapes as well as the classic Vitis vinfera, especially Riesling.

So it wasn’t until Spanish Missionaries discovered the dry climate of New Mexico in 1629 with its sandy soils that the first Vitis vinifera vineyards were planted in what is now the United States. They planted Mission grapes brought over from Spain.

Wine comes to California

Wine didn’t come to California until 1769, when the Spanish started a mission in San Diego, with accompanying vineyards. As they settled further north, they established 20 more missions, concluding with one in Sonoma in 1823. Napa Valley began growing grapes in the 1830s.

Today, of course, due to its dry and sunny climate, which is perfect for grape growing, California produces more than 90 percent of U.S. wine.

In 2016, the U.S. produced 3 billion liters of wine, making it the fourth-largest in the world after Italy, France and Spain. At same time, Americans drink the most of any country – some 3.59 billion liters in 2016, or about 11.1 liters per person.

Jefferson, a passionate wine connoisseur, would be proud.

Liz Thach, Professor of Management and Wine Business, Sonoma State University

Top Trending

Check out what's trending in the news right now.

How to raise a lifelong learner

AP Photo/Stephan Savoia

This post originally appeared on Common Sense Media

"Look! When I mix these paints, I get a whole new color!" Hearing your kids get excited about learning feels like glitter bombs exploding in your heart. And it's confirmation that school and report cards are really only one sign that your kids are learning. While grades and test scores are important, what about the sparkle in their eyes when they discover a "new" bug in the backyard, see a painting that inspires some art of their own, and overcome frustration to go hand-over-hand across the monkey bars? In the end we want their love of learning to go beyond school and sustain them throughout their whole lives.

Unfortunately, lots of kids start to lose their passion for learning as they grow up. Some researchindicates that 40 percent of U.S. high school students have little or no interest in school. How do they get to that place? For some kids school becomes less about learning and more about achievement, right answers, and grades. When that happens, they can start to think learning isn't fun. And as they get older, they want to play it cool and avoid showing a sense of awe about pretty much anything — at least to us. Even kids with exceptional grades are sometimes in it for the letters on report cards and have lost sight of learning.

The good news is that even when kids claim they don't like to learn, they really do. Maybe their hand isn't the first to go up, maybe their grades (whether As or Fs) don't reflect what they know (and don't know), and maybe they can't articulate what they love to learn, but there are things we can do to combat this trend. And the media and technology that's literally at kids' fingertips can help. Though it's best to start encouraging kids to be lifelong learners when they're little, it's never too late. Here are some tips to keep your kid's love of learning alive:

Start early, inspire often

Babies and toddlers find everything fascinating: It's often enough just to play with sand, stack blocks, and even just stare at their hands. Parents can build on this natural inclination in lots of ways. First, you can share their wonder at the world. If your kid is amazed by a spider web or delighted by the garbage truck, let yourself mirror that enthusiasm and build on it by asking questions and noticing things: "The truck's wheels are circles. What other shapes do I see?" or "I wonder what kind of spider made this web."

Getting out into the world to have adventures is also a great way to inspire learning. Nature hikes, museums, road trips, and even your own street can have tons of opportunities to discover things and wonder at what you see. Other than showing and sharing excitement, parents can help kids make sense of what they experience. Watching, playing, exploring, and talking with your kid helps them connect some dots and continue a dialogue.

Using media to inspire learning

Reading to your kids not only inspires learning and lays a foundation for literacy, but if you comment and ask questions as you read, it shows kids that reading can be an active process.

And don't discount kids' favorite online pastimes, such as watching video clips on YouTube or social media as potential learning opportunities. Check out videos that examine unique concepts, such as the ones on Khan Academy, Vsauce, and SciShow. Ask kids what subjects they're interested in, what their friends are sharing, and what's trending to get ideas.

Model learning

In addition to being open about your own wonder and curiosity, you can also be a role model for the learning process. Once you're curious about something, what do you do next? We've gotten so used to Googling or simply asking Alexa for answers, but sometimes it's fun to ask more questions and try to figure things out without the help of technology. And sometimes, an unsolvable mystery is part of the fun!

Talking through the learning process with your kid not only shows some ways learning can happen, but also that it's for grown-ups, too. This can be as simple as sharing what you're learning from a movie or TV show. It's especially great to walk kids through what happens when you hit obstacles. For example, if you're reading articles or manuals to learn a new skill at work or you're trying a new workout, talk through the tough parts and what you do to overcome obstacles: "I've never done this type of exercise, so I'm making lots of mistakes, but I asked for some help and am being a good friend to myself by being patient as I practice." And when you make mistakes, show how we can learn from them and sometimes even turn them into a "beautiful oops."

Using media to model learning

Find media you can use together. Seeing you learn something — for example while playing family games or trivia apps — demonstrates the process. Also consider watching movies and TV shows that help foster curiosity.

Show kids how to use references and research apps to gain a deeper understanding of a topic.

Don't be so sure

Too often, learning is about having the "right" answer, and adults are the keepers of knowledge. Instead of always being the expert, be an explorer with your kid and let them teach you along the way. If they stun you with knowledge and insights, don't just say, "wow, you're smart," since research shows empty praise can backfire. Reinforcing their effort and process with specific observations makes a bigger impact.

Even if you do have some hot wisdom to drop, try to stay open and curious about other positions or further facts about a topic. Foster problem solving and critical thinking by going deeper, examining opposing points of view, and finding connections. Asking, "what do you think?" is always a good place to start when a kid is curious about something to find out what they already know and where they want to go next.

And if there's a problem you can solve together — repairing a bookshelf, researching potential pets, using a new recipe — go for it! Working through steps, finding information, and untangling tricky moments shows kids that we keep learning throughout life.

Using media to explore what you don't know

Discover different angles or viewpoints — not to condone or justify things that oppose your values — but to help kids learn to think critically about what they see and hear. Read or watch current events together and fact-check the stories to discover additional information to inform your opinions.

Watch documentaries on various subjects such as history, animals, and space. Sharing new discoveries increases knowledge -- as well as bonding.

Go beyond subjects and skills

Sure, we want our kids to be great at math, reading, and science, but what about the so-called "soft skills" like kindness, empathy, and perseverance? While they can be hard to measure, we want our kids to keep learning about how to be the best human being they can be. Like more concrete skills, building these character traits lend themselves to modeling and narrating so kids can see how grownups work through interpersonal issues: "Someone at work said something that made me angry, so I had to use some chill skills to calm down, and then I used 'I' statements when I talked with her about it." Taking responsibility for mistakes, making amends, and showing self-awareness about strengths and weaknesses is also a good way to demonstrate how we keep working on ourselves and are never perfect.

Using media to foster soft skills

Check out our lists of TV shows and movies that emphasize specific character traits. Use the conversation starters in the "Talk to your kids About. . . " section of the reviews to reinforce messages.

Role model responsible online behavior so kids are respectful to others when they start interacting online. Digital citizenship skills as just as important as academic skills — not only for drama-free social lives, but also for kids' potential careers. Learn more social media basics to set your kids up for positive online experiences.

Keep it real, encourage autonomy, support self-reflection

It's important to let kids try things, fail, and try again. Even as they get older and want to attempt things on their own, you should still let them -- within reason, of course. Making choices and having some independence teaches them special lessons they can't get anywhere else, such as resilience.

When kids are mostly told what they need to learn in school, being able to explore their own interests can be really powerful. Not only can they piggyback on their own passions, but they can also learn things that are especially relevant to their real lives, like changing a tire, organizing a toy drive, or cooking.

It's also helpful to get kids to examine their own learning process. Self-reflection, mindfulness, and metacognition — understanding how you learn — let kids gain a deeper understanding of themselves and how to approach new topics and circumstances.

Using media to encourage kids to learn on their own

Let's say your teen is on Instagram marveling at Rihanna's new makeup line. Ask what sets it apart, how it's being marketed, and why Rihanna might be taking time to do it in the first place. Maybe you can tap into your teen's interests and turn them into a discussion about branding and being an entrepreneur.

Have a nightly challenge where everyone has to share one fascinating fact they learned that day at dinner. Twitter is a gold mine of facts. Try following: #AP_Oddities, Bill Nye the Science Guy, or #wokeletter.

Top Trending

Check out the major news stories of the day

Animal rights aren’t a priority — and it’s hard to imagine how they could be in a capitalist economy

Getty/Carl de Souza

I was talking to my friend the other day about her decision to stop eating meat and asked if she had made that choice for health reasons or ethical ones. She responded with an observation that stuck with me as I was writing this article — specifically, that it says a great deal about our culture that we find it easier, less shameful even, to justify not harming animals if we can claim to do so for selfish reasons, rather than selfless ones.

It's a valid point, but one that raises more questions than it answers. Why exactly do we feel the need, as a human society, to pooh-pooh the moral problems with mistreating animals?

This brings me to one of the big stories in science news right now. Nikos Logothetis, internationally acclaimed neuroscientist and a director at the Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics (MPI-Biocyb) in the small German city of Tübingen, was indicted in February for allegedly violating animal protection laws, according to Nature. The criminal case occurred after an animal rights group drew attention to undercover footage taken of Logothetis in 2014 that supposedly showed him mistreating research monkeys. Logothetis used to run a primate laboratory at MPI-Biocyb; because he studies how the brain makes sense of the world, his research inevitably led him to experiment on primates.

As a result of his indictment, Logothetis has been banned from both conducting experiments with animals and from supervising other scientists doing the same thing. MPI-Biocyb scientists have protested Logothetis' treatment, arguing that it denies him the right to be considered innocent until proven guilty (a court date hasn't been chosen yet) and that it leaves scientists vulnerable to any criticism from animal rights activists, no matter how irrational it might be. These are all potentially legitimate observations — if animal research is going to be common in these facilities, then scientists do need to be protected from facing consequences when claims against them are potentially spurious — yet it ignores the underlying issue at stake here.

That issue was inadvertently raised by Max Planck Society president Martin Stratmann, who told Nature that the consequences imposed on Logothetis were necessary because they "must uphold public trust that animal research is carried out properly." He added, "Any public perception that animals are being treated incorrectly will damage the image of animal research as a whole."

Notice the unspoken assumption that animal research can somehow be made savory, or at least minimally unsavory, if only the existing laws pertaining to animal rights are respected. This argument is the cousin of the one that my friend alluded to about how we are more respectful of policies that don't harm animals if they can be connected to human concerns — as opposed to caring about the suffering of the non-human creatures themselves. On both occasions — whether it's a vegetarian reassuring an omnivore that he or she is only avoiding animal-based foods for health reasons, or the lab owner telling the public that people need animal research so long as legal propriety is maintained — there is the unuttered but unmistakable rule that "practicality" somehow equals "allowing human beings to cause suffering to animals."

This assumption exists because we, as a species, have not evolved past an economy that renders animal rights at best irrelevant and at worst a dangerous (read: unprofitable) distraction.

When I say "economy" I refer to any economy in a market-based system, where supply and demand determines pricing and unprofitability is associated with failure. Within such a system, it makes sense that factory farms have become the norm, with the underlying ethic being the one summed up by National Hog Farmer in 1978:

"The breeding sow should be thought of, and treated as, a valuable piece of machinery whose function is to pump out baby pigs like a sausage machine."

This may seem monstrous, but makes sense from a cold business perspective. When no one is guaranteed a living and people need to eat, anyone who wishes to make a living in a culture that regularly consumes meat must produce his or her product as quickly and efficiently as possible. Similarly, when it comes to conducting scientific research on a number of subjects, using animal subjects is often cheaper and more reliable than alternative, less cruel methods that might exist.

When it comes to the amount of money being made or lost, the fact that these animals are suffering is totally meaningless. Because in our economy the financial bottom line is the only bottom line that counts, this means that animal suffering in the world as it exists today is itself totally meaningless, save to those with the heart to proactively care.

And yet, with the exception of a handful of advocacy groups, most of us don't like to think about animals suffering. It makes us uncomfortable. Even people who don't prioritize animal rights issues still dislike the idea of intelligent creatures spending their whole lives in squalid conditions, isolated from their own kind, in a constant state of physical and emotional pain.

Unless you're a sadist or a sociopath, that thought is a deeply upsetting one. Yet because our economy, and consequently our entire social structure, cannot exist without animals suffering, we have to find our way of making peace with the fact that the edifice of the modern human world is built on the foundation of animal suffering. The simplest way to do that is to simply act as though regarding animal rights as important is an ideal to be scorned — or, at the very least, quickly subsumed with reminders that human beings come first.

For the record, I don't write any of this from a holier than thou perspective. I eat meat on a regular basis, wear clothes made from animal skins and read scientific articles that provide me with knowledge gleaned at the expense of suffering creatures of all kinds. When I say that human beings are guilty of hurting animals in order to benefit ourselves as a species, I point the finger at myself as much as anyone else.

Similarly, I am not attempting to argue that the interests of human beings shouldn't be held in higher regard than those of animals. Although I suspect that quite often the interests of both could be paid sufficient respect if we didn't live in a culture where everyone needs to maximize their profit margins, I would agree that if there is a choice between slaughtering animals or letting human beings starve, or experimenting on animals versus providing people with the medicines they need, people must win each time.

My point here is merely that, even in a case like that of Logothetis, which seems to revolve around animal rights finally being respected, there is still an underlying cultural discomfort with the idea that we should actually care about how animals are treated. It is one that in the grander scheme of things has very little to do with Logothetis and his fellow scientists, who are most likely good, intelligent people who simply want to advance the frontiers of human knowledge and make the world a better place. Indeed, it has very little to do with any group of "good guys" or "bad guys."

The basic problem is that, because almost every human being lives in a world where they need to make money to survive, we have no choice but to mistreat animals, even though deep down most of us know that doing so is wrong. More likely than not, if human beings could evolve past a social system that demanded the consumption of goods and accumulation of wealth, we would come up with common-sense ways to meet our needs vis-à-vis animals while minimizing their suffering in the process.

Of course, if human beings could evolve past our dependency on currency-based social constructs, a whole lot of other problems would also be solved in the process. Since we're nowhere near achieving that distant nirvana, however, it seems like the best we can expect are the piecemeal statutes in nations like Germany that try to protect animals in whatever minor ways we can.

Aside from that, they're doomed.

Do you anger easily at dusk? So do most other people (and mice)

(Wikimedia)

This article originally appeared on Massive

You know the scenario — after a hard day at work, sometimes nothing sounds better than plopping down on the couch and relaxing in peace and quiet. Instead, you get home and are irritated to find that one of your roommates has left dishes piling up in the sink, and the other one wants to emotionally unload on you about a recent argument with a mutual friend. At any other time of day you might be able to let these things go, but right now you’re worried you might just lose it.

For many of us, this evening anger is a near daily occurrence. In this case, it could be that the stress of your workday or the fact that you skipped lunch is making you feel more likely to lash out. Another possible explanation is that your biological clock has decided that now is the time to act aggressively.

Scientists have long suspected that emotional states may be regulated in part by biological rhythms, and even Aristotle astutely observed that human temperament seemed to be influenced by time. The master circadian clock, which resides in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) located deep at the base of the brain, drives our biological rhythms. By integrating information about the cycle of light and dark in the environment and the body’s own internal state, the SCN sets the pace for important processes like sleep, metabolism, and hormone release on an approximately 24-hour schedule.

While the mechanisms the SCN uses to time these processes are areas of intense study, we have a comparatively poor understanding of if and how the SCN affects the regulation of emotion.

This lack of understanding has consequences — there’s a strong correlation between disruptions to the circadian system and several disorders associated with increased aggression. Few examples are as dramatic as sundowning syndrome, a mysterious phenomenon observed in Alzheimer’s and dementia patients in which fits of anger and delirium occur most frequently in the early evening.

Despite its importance, demonstrating a definitive role for the SCN in driving emotional rhythms in humans poses a number of technical challenges. As with many problems in neuroscience, scientists often turn to mouse models to drive progress.

In a new study published in Nature Neuroscience, a team based at Harvard Medical School demonstrated that mice are more likely to attack other mice during the early evening than at other times of day, suggesting aggressive behavior occurs with a daily rhythm. Importantly, the group discovered a circuit connecting the SCN to neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH), a brain region previously shown to drive attack behavior in mice. This is the first demonstration of a mechanism for the SCN in the regulation of aggression.

The team’s first step was to confirm that indeed aggressive behavior displays a daily rhythm. To do this, they used the resident-intruder model, in which an “intruder” mouse is introduced into the home cage of a “resident” mouse, prompting the resident to defend its territory. By studying the frequency and intensity of the resident’s attacks on intruders at different times of day, the team found that aggressive behavior was most likely to occur about an hour after the lights turned off, even more so than at other points during the night.

Now that the researchers had demonstrated aggression occurred with a predictable rhythm, they could begin to manipulate neurons in an effort to characterize the neural circuit mediating the rhythmic behavior. They started by disrupting the release of the neurotransmitter GABA from neurons in the subparaventricular zone (SPZ), a well-known relay station connecting the SCN to several other parts of the brain. The rhythm of aggression completely disappeared from the SPZ-disrupted mice, and they became more aggressive overall.

Because GABA acts as a signal for neurons to decrease their activity, the researchers hypothesized that the SPZ might be inhibiting the activity of the VMH at different times of day, thus driving the rhythm of aggressive behavior. To test their idea, the researchers infected SPZ neurons with light-sensitive proteins that allowed them to selectively activate or silence their activity with lasers, and simultaneously recorded electrical responses in VMH neurons. They found that the SPZ was inhibiting the VMH more strongly at times they predicted based on the mouse’s behavioral rhythm, and that this timing information came from neurons in the SCN.

After taking a closer look at the VMH neurons mediating attacking behavior, the researchers found that the SPZ projected to not just one, but two distinct groups of VMH neurons, demonstrating the existence of two parallel pathways by which the SCN could drive rhythms of aggression. When researchers used DREADDS to acutely activate this second group of VMH neurons, the average resident mouse spent considerably more time attacking an intruder mouse, and did so much more rapidly.

Overall, the experiments suggest that the newly discovered circuit acts to curb aggression in the early morning, and that disrupting it drives a mouse to attack. This idea leads the authors to propose that the ability to control this circuit would grant control over aggressive behavior. In the future, such an ability may serve as an important therapeutic tool for disorders like sundowning syndrome, which the authors also suggest could be caused by a compromise of this circuit in neurodegenerative diseases.

It remains to be seen whether a similar functional circuit exists in humans, and it’s certainly reasonable to question the resemblance between aggressive behavior in mice and people. However, these results provide a nice biological context for several recent behavioral studies providing more evidence for rhythms of aggression in humans. One such study examined the emotional content in a set of over 800 million Tweets posted by Twitter users in the UK over the course of four years, and found that anger and several other emotions displayed both daily and seasonal rhythms.

While there’s still a lot of work to do, the finding that emotions are rhythmically modulated will be important to consider, not only in how we think about mental health and neurological disease, but also in our daily social interactions.

Retta on why she’s “So Close to Being the S**t, Y’all Don’t Even Know”

AP/Brent N. Clarke

Retta, who played Donna on “Parks and Recreation” and currently stars in "Good Girls," sat down with me for a recent episode of "Salon Talks" to share her hilarious journey to Hollywood and stories from her new memoir “So Close to Being the Sh*t, Y'all Don't Even Know.”

Retta tells me about why she abandoned her medical school plans and chased her dream of starring in her own sitcom instead. Plus, she opens up about race and finding her own voice in the industry. This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

How did the book come about?

I got a call one day from someone who claimed to be my lit agent. I was like, “I’ve never written a book. How do I have a lit agent?”

They’re everywhere.

It was the department within my agency. And she said there’s an editor who thinks you should write a book, let’s set up a meeting. So we set up the meeting, we talked about a bunch of different things and then I left. And she said you have to do a book proposal. And I was like, “Oh.” I was heading back to Vancouver to go shoot "Girlfriends' Guide to Divorce" and while I was there I was so frustrated. It was a lot of work to do a book proposal. It stressed me out.

It’s a lot of work! You need comp titles, you need an overview of what the book is going to be about . . .

The first chapter, the last chapter. And I said, “I can’t do this. I don’t have the energy or the patience.” She was like, “All right, well I’ll go back to them and tell them and we’ll resurface at another date.” Then she said, “What if they offered you money to do the book?” I said, “Well if they pay me I’ll do the job.”

They offered me money and I was like, “OK.” That’s how it happened. They were like, “Here’s some money go write this book.” So I wrote the book and took the money.

Watch our full conversation with Retta

The "Parks & Rec" and "Good Girls" star talks about her career and new book

At that moment did you feel like it was something that you really needed to say when you got the opportunity, or did it just come gradually over time?

Well, when I was writing the original book proposal — that never got finished — that’s when I thought about what should be in this book, what this should be. But because I was having so many struggles with it, I let it go. Once they said, “OK, here’s the money, do the book,” I really had to sit down. Dibs Baer would interview me. She had originally sent me this long list of topics of things that happen in someone’s life: mom, dad, brothers, and sisters, just words and lists, and I would go through and decide what stories I wanted to tell and pull from her list. Then once I had made a compilation of all the stories I wanted to tell that’s when I was like, “Oh, this story is telling how close to being the shit I am.”

So that’s what I wanted to get into. How did you come up with that title? Because I think it’s so important.

The book was done before I did the title. Once it was done I felt like that’s what this book is saying, talking about how cool is my life. I’m not on top of the list of actors that they’re going to for these big movies but I’ve hustled enough that my name is known and I get to do cool things. I get to go to the Golden Globes. One of the chapters in the book is how I’ve gotten to go to "Hamilton" as a result of being on shows that people like and that’s why they know me. It was after I’d written the book that I was like, this book basically is talking about how close I am to being the shit.

You actually are really popular and successful and have a great career. So from the perspective of a lot of people trying to get into the industry, they’re saying, “Retta is the shit.”

When you’re in it you realize how much you’re not the shit. You realize . . .

You’re not ordering bald eagle meat with like a side of lobster.

So there’s no toilet in my trailer? No? OK, all right. [Laughs.]

People on the outside of the industry assume certain things. They see you on TV, they think you’re rich. I’m like, oh no, I have to hustle. I’m in between seasons. I am not earning money. I get a few residual checks for certain things but I’m not earning money. I came home from Atlanta after we finished the season and I told my agent and my publicist and my manager, I was like, “We’ve got to find me work until I go back to work.”

That happened to me before. I was on CNN twice and then I was back in my projects and it was like, “Shouldn’t you be in the Hamptons?” I was like, “Isn't it winter?” Then I was like, “No.” They didn’t even pay for that at that particular time.

Right, exactly.

So knowing those levels and understanding those levels of success, does that motivate you and make you work extra hard?

One hundred percent. Chris Rock said he bought his house and that forced him to hustle because he had to pay for the house. It’s one of those things where I want to work but I have a lot of responsibilities now. So my thing is, “Hey Holly, we need to find me some work before I go back shooting in August,” because I have responsibilities. I have parents and things to take care of.

Now you have the confidence to be able to get out there and do the work. When you started out you read about this opportunity you had to be in "Dreamgirls," to play Effie —

To audition.

— to audition for that role, but you psyched yourself out of that. Tell us about that experience.

I’d never understood the phrase "a fear of success." I never got it. And then I was at a point where I was actually getting auditions and my manager had said, “There’s a big audition coming up; it’s for 'Dreamgirls,' the role of Effie.” I knew the story. I knew I would have to sing and dance. I would have to be dressed like the two other girls in the group. In my head, I have a bad ankle so I’m like, “Those girls wear heels. There’s no way I’m going to wear heels. Then I’m so much bigger than the other girls, how are they going to find clothes and we’re wearing matching outfits.” I was so green I didn’t know that they made the clothes for you to wear on the show.

So you thought they went to Nordstrom to go get them?

I thought they were going to have to go to Nordstrom and find a line that has a size 26 and a size 2 — as if — but I just didn’t know. In my head, I was like, there’s no way. I don’t want to be the problem. I’ve got this bad ankle, and dancing is going to be hard and I certainly can’t wear heels. So are they going to shoot me from the knees up?

All these things are running through my head and because of these things I didn’t go to the audition. I kept putting it off. They kept asking, “When can you go in?” I was like, “Oh, I have a scene next week.” In that time they had a show to cast, they had a movie to cast and so they cast it with Jennifer Hudson. So I never went in for the audition.

What do you think was the root of that fear?

A fear of being the problem. I don’t want to be seen as the problem on set. Not that they would see me as a diva — certainly not, because nobody knew who I was — but I didn’t want to be the person that they had to stop rehearsals for because I had to ice my ankle.

Because you can’t get the two-step right.

No, I could get the two-step right.

OK.

Being on my feet for a long time. I can dance, OK.

So do you feel like that could ever happen to you again or now you’re in 100 percent control of that?

I’m sure I’ll have moments of fear, but in my head now it’s like, you came to this city for a reason and the process is auditioning. I’d love to get to the place where I don’t have to audition anymore, because I don’t like auditioning, but I know that I have to do it and so I’m just going to do it. I’m not going to sit in the corner with a stomach ache like “urgh” because you’re sick that you have to do it, but you’re sick that you’re not doing it, so you might as well do it and live with that sickness.

Did you ever audition for a role that you thought that you weren’t going to get and ended up getting it?

Yes, once, and it was a small role. The audition was in Santa Monica, parking was bad and I was like, parking is the worst in this area and I’m not looking to get a ticket. So I kept saying I can’t go in, I can’t go in, and it was right after I had injured my ankle so I was in a boot. I was like, “I’m in this cast. I can’t go in.” And they are like, “That might work for the role.” Anyway, I went in. I parked on the street and I ran in and I was like, “Hey, I’m parked illegally. I can only stay here for a few minutes. So if I can get in that would be great -- otherwise I’m going to have to leave.”

Did they know you?

Mm-mm. They put me in really quick, and it was a small part — it wasn’t for a major lead — and I ended up booking it. I knew for sure that I wasn’t going to get it because I was like, I don’t want a ticket. I’m broke and I can’t afford tickets in Santa Monica.

Hollywood has a history of being racist, [of] typecasting black people. Do you feel like with all these different movements [for diversity] that it’s getting better?

For me, it’s better. I don’t know that it’s better for everybody. But I’ve been lucky enough. My last three gigs have been headed by writers who haven’t chosen to put me into that small box. I used to go out for the same audition: the same nurse, the same secretary, the same meter maid, the sassy black girl who’s funny. I did that for a long, long time. And then my last three big jobs have been for writers — Mike Shaw, Marti Noxon and Jenna Bans — who saw me as a whole person and not adjectives.

One of the things that you talked about that I really think is informative and invaluable is this idea of you learning that you being yourself is the best thing you can do on stage. You don’t have to pander to a black audience because you think that’s what they want. You don’t have to pander to a white audience because you think that’s what they want. Retta just has to be Retta. At what moment did you discover that?

I used to fear the black audience, and this was earlier on in my stand-up career. I did a show with — it might have been Sheryl Underwood.

This was a college gig and the audience was mostly white and I opened for Sheryl at the time. I remember watching Sheryl just be herself and killing in this room. I was like, “Oh, you should just be yourself.” I’ve seen it where I’ve done black rooms where I was like, “I don’t know if I’m urban enough for this room.” Then I’d watch white comics get up and decimate a room. I was like, “That person is just being themselves.”

That’s how I feel with your book, too. A lot of the writing is just straightforward and it feels like we’re having a conversation with you.

That was very important to me. I wanted it to sound like myself, and so — I’m like “yessssss” and “yessssss biiiiiiitch” — I put a lot of i's in "biiiiiiitch" when I type it, about six or seven.

Unless it’s not too intense, then it’s just four. I’m like, “biiiitch.”

It was very important to me to sound like myself because I fell like sometimes you won’t get it unless it sounds like me. You don’t get the personality, and I feel the personality is as important as the story.

So that was a game changer for you?

Yes, but I feel I decided that a long time ago. I feel I decided that when I joined Twitter. I made a conscious decision to be myself on Twitter even though I worked for a network TV show and I didn’t know if they’d want me cursing so much, but I curse. I know that’s what I do.

They say Facebook is the place where you lie to your friends and Twitter is the place where you tell the truth to complete strangers.

Right, yes. That’s exactly what I do.

Now you have these experiences and you’ve traveled to these places and you’ve paid a lot of dues. What type of advice would you give to a person who was on the verge of giving up if you had to talk to them based on your own experiences?

The thing that got me through getting to where I am is belief. I feel like you have to just know it’s going to happen. You have to accept it in your skin. I didn’t know when I would get to where I wanted to be. I just knew it was going to happen and I knew I was going to have to hustle. When I was sleeping on a friend’s floor and eating ramen noodles with American cheese —

Ramen noodles is the official food of the oppressed. I’ve never met a person with a come-up story that didn’t have —

Ten packs for a dollar.

I like hot sauce sauce in mine. I might be bougie. When I get paid, I throw eight shrimps in there. Not the little hard frozen ones — what do you call that, when you suck all the juice out of something?

Dehydrated.

Little dehydrated shrimps. That can’t be shrimp.

I don’t even remember. I was going to say I don’t even remember that.

Maybe that's like an East Baltimore thing.

It’s strictly American cheese.

I think because I always believed it that the struggle portion of it wasn’t that hard. I was like, this is what it is -- you’re supposed to struggle. You rarely hear that someone stepped off a plane and got put in "Jurassic Park." It’s work.

I knew that I had to go through some things. I didn’t know exactly what, but I knew in my head this is supposed to be hard. So as long as you know it’s going to happen, it makes the hard part bearable. When you’re feeling like you’re on the verge of going home you have to take an inventory of is it really what you want? Because if it is you’re not going to leave.

Does that struggle become obsolete once you actually have some success, or do you have days where you’re like, I used to sleep on the floor and eat filthy noodles?

It comes up when I’m in situations where we get a restaurant bill and everybody owes $150 and I’m like, “Daaamn, remember the ramen?” I do remember it for sure. But I don’t look on it as a bad time, because I had fun. That was another thing — I always needed to have fun. So I was around people that I enjoyed being around. I would go to bars that my friends worked at because I knew I could get a hook-up on my bill, that kind of thing.

It’s good to have friends who work at bars.

For sure. I recommend it.

Summer is truffle hunting season in the Umbrian countryside

Elizabeth Minchilli

If someone told me that one day I would have too many truffles, I would have checked to see if they had a fever. Too many truffles? Is that like having too many oysters? Or too much champagne? Is that really a thing?

Now, however, that I live in the land of truffles, I’ve discovered that it is, in fact, a thing. And that thing is good.

Let me backtrack a bit. When I say that I live in the land of truffles, I don’t mean Rome, obviously. I’m referring to our home in Umbria. And while I’ve always loved truffles, it was in Umbria that I learned that truffles are not always meant to be consumed in thin slices in rarefied restaurants, but something that you could actually order up at a truck-stop diner.

I first learned about local truffles from my neighbor Marisa, who lives down the road from us, on a working farm. Since the day we moved in, she would gift me things like a goose or rabbit, a dozen eggs, or a bag full of freshly harvested wild chicory. But one day she came over with a sack of truffles. Needless to say, I was shocked.

A word about these truffles. When most people think of truffles they imagine pale slivers being shaved off a precious tuber in an expensive restaurant. As the waiter shaves, you are mentally adding up just how much that heavenly pasta or risotto will cost. And cost it does. But those are usually white truffles from Alba, in Piemonte, or black truffles from Perigord in France, and are quite a different animal from what Marisa was handing over.

As I took the precious gift from her hands I was a bit taken aback by the cold. The plastic bag was frosty and closed with one of those twisty metal things. Not very ceremonious for what I thought of as a priceless tuber.

“Sono scorzone.” “They are scorzone,” Marisa explained, implying that they were nothing to get that worked up about. But even frozen, and even through the bag, I could smell their intense aroma. “They’re good for pasta, but put them in the freezer right away, that way they will stay fresh.”

What I had was a pound of summer truffles (tuber aestivum vitt). And as I soon learned not all truffles are created equal. As it turns out these truffles are readily “findable” all over Umbria, from the end of May to the end of August. And the thing that makes them easier to find compared to their more expensive fall and winter cousins, is their intense smell, which also makes them perfect for cooking. While the more prized varieties may have a more intense taste, the aroma of the summer truffles stands up to heat, which makes it a favorite with chefs both local and not. But you do have to use quite a few to make an impact—which explained Marisa’s gracious gift of plenty.

To get the full effect you have to use a heavy hand. The locals know this, and you will never see them shaving them onto anything, unless it’s as a final garnish. They use them by the handful, and treat them almost like a vegetable. An expensive vegetable, but a vegetable.

* * *

As it turned out, my life as the recipient of truffle gifts was only just beginning. While I put up with hunters with guns traipsing through our property on their way to shoot rabbits, pheasants, and the odd boar (it’s part of the local traditions, I’ve gotten over it), I actually welcome the truffle hunters. First of all: cute dogs. While truffles used to be hunted by pigs, today all truffle hunters use dogs to sniff out their harvest. And if the “real” hunting dogs are skittish and intensely focused on their prey, truffle dogs are a completely different story. They are often coddled and have close working relationships with their owners and cozy up to random humans (errant American women going gaga over their cuteness included). So I’m always up for a visit from a truffle hunter.

Also? Most of the truffle hunters that I run into on or near our house are doing it for the fun of it. They are not professional truffle gatherers and so are not only willing to chat about their hobby, but almost always dig into their pockets to hand over a half-dozen lumpy, muddy orbs.

While I, too, am the proud owner of a cute mutt, little did I know he had anything in common with his working brethren.

Until one day, when Pico was eight years old, he decided, out of the blue, that he was a truffle dog. At least for two days at the end of August. One day, coming back from his early morning walk on his own on our property, he returned to the back door with a huge truffle in his mouth.

For real!

And then, two days later, while our gardener was digging up an old bush, Pico came running over, started digging, and came up with three more truffles.

After that burst of energy, Pico has pretty much taken it easy since then, mostly napping on various couches and certainly not out truffling, which is actually a good thing, because we don’t have a truffle license. Like any other form of hunting, truffle hunting is tightly controlled. There is an exam and specific tools to use so that the grounds are not damaged.

Getting back to the whole pig thing: no, there are no pigs rooting around for roots. It’s a dog-eat-truffle world in the Umbrian countryside, and teaching your dog not to eat the truffles, but just show you where they are, is the aim. Truffle dogs are much prized in Italy, as are the areas where truffles are found. In fact, whenever I tell Italians this story about Pico, they sort of look over their shoulder, and then whisper back to me, “You really shouldn’t tell people this story.” Why? Evidently someone might swoop in and kidnap my pooch. Since he’s mostly on the couch asleep I think we are pretty safe from any potential malfeasance.

But truffle dogs are a very big deal and while the Lagotto Romagnolo is probably the best-known breed, it’s mostly sought after since it is easy to train. Hunters in Umbria will start training dogs as puppies, teaching them to go after the scent of truffle, rewarding them with chunks of cheese or hot dogs (which taste infinitely better than the lumpy black things they dig up). Most hunters will tell you that while male dogs have a better nose, females are easier to train.

Driving around Umbria in the fall, you are likely to see cars parked randomly by the side of the road, left by hunters as they head into the woods to search. And there is a lot of hunting that goes on in the wild. But these days there is quite an industry—especially in Umbria—of truffle groves.

No, truffles aren’t growing on trees. But they do tend to grow under specific types of trees. Oaks mostly. Truffles are actually a type of mushroom that grows underground in a symbiotic relationship with roots of trees. In Umbria they are most often found beneath oaks, and not far from Spanish broom. Not too long ago, European researchers realized that the spores of truffles could be inoculated into the roots of host trees. The trees are then planted—much like a fruit orchard—except in this case the “fruit” is beneath the ground, and you still need a dog to help you find them.

Excerpted from "Eating My Way through Italy: Heading Off the Main Roads to Discover the Hidden Treasures of the Italian Table" by Elizabeth Minchilli. Copyright © 2018 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Griffin.

Top Trending

Check out the top news stories here!

June 2, 2018

Exploring how brains grow could help explain autism

Shutterstock/DedMityay

This article originally appeared on Massive.

Approximately 24.8 million people worldwide are diagnosed with some form of autism, according to a 2015 report, exhibiting social disconnection, communication issues, and repetitive behaviors due to brain connections going kaput sometime during the organ’s development. We began learning in the 1970s that differences in brain development and genetics were primarily responsible for autism, and since then researchers have been racing to better understand its the biological basis.

In this context, a small brain structure regulating our emotional responsiveness and social behavior called the amygdala has long been a subject of research. Recently, studies discovered a relationship between the amygdala’s size and autism.

In autistic children up to five years of age, the amygdalae were typically bigger than those in neurotypical children, and the size correlated with severity of their behavioral differences. However, in adolescents and adults, the amygdala size was similar (or even smaller) in autistic cases than it was in non-autistic individuals.

MRI scans revealed that amygdalae volume increased with age in neurotypical people. In contrast, the brain’s emotion regulator stopped growing beyond childhood in autistic subjects. Why is the amygdala growing under most conditions? Why is it big in autistic kids but then doesn’t grow?

To understand this, a group of researchers from the University of California-Davis recently conducted an extensive study on the amygdalae of neurotypical and autistic individuals of different ages. They knew about the growth pattern of amygdalae in both populations. But this volume increase of an organ can happen for many reasons – for example, increase in size of individual cells, multiplication of the main or supporting cells etc.

The UC Davis researchers hypothesized that, in this case, the growth probably had to do with the neurons – the brain’s smallest, excitable units transmitting and receiving nerve impulses. They found fewer neurons in autistic adults in a previous study. To verify this and look inside the amygdalae, they collected brains of deceased neurotypical and autistic donors aged two to 48 years from the National Institute of Health’s NeuroBioBank, Autism BrainNet, and the Autism Celloidin Library. Then they sorted the brains they collected into three groups based on age: kids (ages 2 to 13), teenagers (14-20) and adults (over 21) and sliced them to reach the deeper regions where the amygdala resides.

Once exposed, the researchers dyed the amygdala regions and used two different labels to identify immature and fully developed neurons. There is a sub-region in the amygdala called the paralaminar nucleus that is known to be rich in immature neurons at birth. This means that in later stages of human development, if there is a need for new fully functional neurons, this region could serve as a source.

Upon labelling the immature neurons in all the available amygdalae, the researchers found that their numbers decrease with age irrespective of the presence of autism. The researchers then started looking for fully developed (i.e., mature) neurons. They found higher mature neuron numbers with increasing age in the neurotypical individuals group. In autistic cases, there were more mature neurons in kids, but the numbers dropped significantly with age.

Taken together, the results indicate that in non-autistic people, immature neurons decrease with age and that correlates with an increase in mature neurons in the amygdala. In the case of autism, there is age-related decline of immature as well as mature neurons, with the latter being abnormally high in children. This pattern suggests that neuron degradation over time may be a possible basis for the development and persistence of autism. The high mature neuron numbers in autistic children imply abnormal development of their amygdalae before and after birth as well as, most likely, hyperactive amygdalae. This could mean that neuron death is due to imbalanced excitation over time.

The new research shows for the first time a correlation between neuron numbers, amygdala size, and autism. But scientists still don’t know the exact cause. What are the processes that precisely drive the high neuron number in autistic infants and children? Are the immature neurons really serving as the pool for mature neurons? Is this pattern observed in other neuropsychiatric disorders involving the amygdala as well, like depression, bipolar disorder, or anxiety disorder?

Exploring the roots of this growth trajectory could not only explain the underlying basis for such related abnormal brain conditions, but also throw light on specific points when the typical development phase changes that could be critical for designing treatments.

Top Trending

Check out what's trending in the news right now.