Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 270

October 15, 2017

In Las Vegas, excess and fantasy bleed into tragedy

Fireworks explode over the Las Vegas Strip during a New Year's Eve celebration Sunday, Jan. 1, 2017, in Las Vegas. (AP Photo/John Locher) (Credit: AP)

In Sin City, people often do bad things to themselves.

Rather than deal with their lapses – moral, financial, marital – there’s a ready-made marketing slogan to fall back on: “What happens in Vegas stays in Vegas.”

It’s a way of permitting yourself to indulge, and Vegas casinos – built on a manic dynamic of gambling, sex and food consumption – make their owners billions of bucks off this mantra.

Although living a long 60-mile desert drive from the city, Stephen Paddock spent most of his time there gambling. How did a seemingly happy habitual casino player conjure up serial murder by killing and injuring hundreds using enough firepower to equip a small army?

As an urban sociologist, I’ve written about how Las Vegas operates as a “themed environment,” one that channels the power of fantasy to promote a form of boundless, excessive indulgence.

We may never know Stephen Paddock’s true motives. But what if his horrific act were to be interpreted through this lens of fantasy and indulgence?

The power of theme

The famous French literary critic Roland Barthes was the first to discuss the multilayered power of “the sign” as a myth that can project multiple meanings, while uniting them under the umbrella of a “megatheme.” For example, he saw the Eiffel Tower as a structure that fused early industrialization with modernity, as well as the international symbol of Paris.

The American semiotician Charles S. Peirce had a similar name for this phenomenon; he called it an “icon.” Think of the American flag. It means different things to different people and, simultaneously, the same thing to millions.

Any themed environment, from Disneyland to the Olive Garden, uses an overarching message to unite consumers around a single purpose, whether it’s a reverie of youthful innocence or the prospect of an abundant, family-style Italian dinner.

These signals – conveyed and repeated through architecture, design, advertisements, logos and slogans – have the power to attract large audiences in a way so that each individual can find something meaningful in the consumer experience.

Eat the most, spend the most, win the most…

I argue that in Las Vegas, the sign of “excess” is the unifying element of its themed environment. And I’ve compared its culture to that of Dubai, a Middle Eastern city that has experienced rapid development over the past 20 years.

Yet the two are distinct. In Dubai, excess is purely symbolic and simplistic, with every material object directly alluding to it. Hotel rooms cost thousands of dollars a night. They come with gold faucets, gold beds, gold bedding – gold everywhere.

You don’t need to be rich to go to Las Vegas. But its excess is palatable, with threads that work through a range of connotative associations. Buffets compete for the privilege of serving the most food; casinos promote games with the allure of “whale” level jackpots; luxury goods, gold or otherwise, saturate hotel rooms and shopping malls; and spectacular shows take place on a nightly basis. Excess in Las Vegas cues the lizard brain to indulge and spend.

Although people may imagine that they journey there to be winners, they are merely on a conveyor belt of excessive consumerism the moment they step off the plane. When casinos began a copycat period of renovations in the late 1970s, they started incorporating shopping malls and Godzilla-scale buffets, inventing a closed circuit of excessive spending.

Patrons take food from the buffet line at Las Vegas Hilton, which set a Guinness world record for the largest buffet in 2006.

Jae C. Hong/AP Photo

Today, fantasies of the Old West, Ancient Egypt, the circus and tropical paradise are built into casino environments that, at their core, simply offer different flavors of the same thing: manic gambling, eating, drinking and sex.

Perhaps this is why Ceasars Palace has no apostrophe after the “r.” In Las Vegas, everyone can be a Roman emperor, even if they cannot be an Arab prince.

We don’t know much about Stephen Paddock, the mass murderer. But we do know that he wagered excessive amounts of money every day. It was his way of life, and he could afford it.

Excess is also one way to end your life. Just look at “La Grande Bouffe,” James Gandolfini, Orson Welles or any celebrity who took what’s called an “overdose” to die.

Kill the most?

“Smokin’ Aces” was a 2006 Hollywood film directed and written by Joe Carnahan. It tells the story of an assortment of assassins who have been ordered to kill a Las Vegas entertainer set to testify against a casino mob boss. The heavily armed assassins converge on a hotel where the entertainer is holed up awaiting trial; one sets up a M82 50 caliber sniper rifle on a tripod, similar to Paddock. The ensuing mayhem results in at least 20 law enforcement officials and civilians dead or wounded.

Of course, this was only a fantasy. Nobody died. New York Times film critic A.O. Scott called it a “dumb film,” adding that it might cause “dumbness in others.” Carnahan, the auteur, went on to do two more “Smokin” films, so popular was the (dumb) original.

There’s something fitting about Las Vegas being a place where a fictional fantasy ended up mirroring tragic reality. In the wake of the shooting, conspiracy rumors abound. Law enforcement officials and the news media report little about Paddock’s motives. I don’t possess any more knowledge than they do.

However, I do wonder if Paddock, as he slapped those automatic rifles onto tripods, had Las Vegas-style excess – high stakes, big numbers, bright lights, the book of Guinness – dancing through his mind.

However, I do wonder if Paddock, as he slapped those automatic rifles onto tripods, had Las Vegas-style excess – high stakes, big numbers, bright lights, the book of Guinness – dancing through his mind.

Mark Gottdiener, Professor Emeritus of Sociology, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York

Having the sex talk early and often with kids is good

(Credit: AP Photo/Kristen Wyatt)

Parents may be uncomfortable initiating “the sex talk,” but whether they want to or not, parents teach their kids about sex and sexuality. Kids learn early what a sexual relationship looks like.

Broaching the topic of sex can be awkward. Parents may not know how to approach the topic in an age-appropriate way, they may be uncomfortable with their own sexuality or they may fear “planting information” in children’s minds.

Parental influence is essential to sexual understanding, yet parents’ approaches, attitudes and beliefs in teaching their children are still tentative. The way a parent touches a child, the language a parent uses to talk about sexuality, the way parents express their own sexuality and the way parents handle children’s questions all influence a child’s sexual development.

We are researchers of intimate relationship education. We recently learned through surveying college students that very few learned about sex from their parents, but those who did reported a more positive learning experience than from any other source, such as peers, the media and religious education.

The facts of modern life

Children are exposed to advertising when they’re as young as six months old – even babies recognize business logos. Researcher and media activist Jean Kilbourne, internationally recognized for her work on the image of women in advertising, has said that “Nowhere is sex more trivialized than in pornography, media and advertising.” Distorted images leave youth with unrealistic expectations about normal relationships.

Long before the social media age, a 2000 study found that teenagers see 143 incidents of sexual behavior on network television at prime time each week; few represented safe and healthy sexual relationships. The media tend to glamorize, degrade and exploit sexuality and intimate relationships. Media also model promiscuity and objectification of women and characterize aggressive behaviors as normal in intimate relationships. Violence and abuse are the chilling but logical result of female objectification.

While there is no consensus as to a critical level of communication, we do know that some accurate, reliable information about sex reduces risky behaviors. If parents are uncomfortable dealing with sexual issues, those messages are passed to their children. Parents who can talk with their children about sex can positively influence their children’s sexual behaviors.

Can’t someone else do this for me?

Sex education in schools may provide children with information about sex, but parents’ opinions are sometimes at odds with what teachers present; some advocate for abstinence-only education, while others might prefer comprehensive sex education. The National Education Association developed the National Sexual Health Standards for sex education in schools, including age-appropriate suggestions for curricula.

Peers become the key source of information if parents fail to talk to kids about sex.

VGStockstudio/Shutterstock.com

Children often receive contradictory information between their secular and religious educations, leaving them to question what to believe about sex and sometimes confusing them more. Open and honest communication about sex in families can help kids make sense of the mixed messages.

Parents remain the primary influences on sexual development in childhood, with siblings and sex education as close followers. During late childhood, a more powerful force – peer relationships – takes over parental influences that are vague or too late in delivery.

Even if parents don’t feel competent in their delivery of sexual information, children receive and incorporate parental guidance with greater confidence than that from any other source.

Engaging in difficult conversations establishes trust and primes children to approach parents with future life challenges. Information about sex is best received from parents regardless of the possibly inadequate delivery. Parents are strong rivals of other information sources. Teaching about sex early and often contributes to a healthy sexual self-esteem. Parents may instill a realistic understanding of healthy intimate relationships.

Getting started

Maintaining an open, honest relationship with your children is key.

Pixelheadphoto digital skillet/Shutterstock.com

So how do you do it? There is no perfect way to start the conversation, but we suggest a few ways here that may inspire parents to initiate conversations about sex, and through trial and error, develop creative ways of continuing the conversations, early and often.

Several age-appropriate books are available that teach about reproduction in all life forms – “It’s Not the Stork,” “How to Talk to Your Kids About Sex” and “Amazing You!: Getting Smart About Your Body Parts”.

Watch TV with children. Movies can provide opportunities to ask questions and spark conversation with kids about healthy relationships and sexuality in the context of relatable characters.

Demonstrate openness and honesty about values and encourage curiosity.

Allow conversation to emerge around sexuality at home – other people having children, animals reproducing or anatomically correct names for body parts.

Access sex education materials such as the National Sexual Health Standards.

The goal is to support children in developing healthy intimate relationships. Seek support in dealing with concerns about sex and sexuality. Break the cycle of silence that is commonplace in many homes around sex and sexuality. Parents are in a position to advocate for sexual health by communicating about sex with their children, early and often.

The goal is to support children in developing healthy intimate relationships. Seek support in dealing with concerns about sex and sexuality. Break the cycle of silence that is commonplace in many homes around sex and sexuality. Parents are in a position to advocate for sexual health by communicating about sex with their children, early and often.

Veronica I. Johnson, Associate Professor, Counselor Education, The University of Montana and Guy Ray Backlund, Associate Professor, New Mexico State University

Not looking for love

(Credit: Getty/Georgijevic)

In a world of apps and customized everything, from Spotify playlists to Seamless suggestions, people expect all kinds of convenient services to come tailored to their specific interests. Meanwhile, or because of this, women in major metropolitan areas are having an increasingly difficult time meeting platonic friends.

While there are a number of dating apps and websites that exist for women on the go, the same isn’t true of quick, online ways to make friends. So women turn to whatever apps and forums they have at hand to try to find these elusive companions. In doing so, they reveal what “friendship” means in today’s app-cluttered world.

“I’ve tried apps targeted to meet friends with no luck!” writes “Looking for BFF,” a 29-year-old Astoria resident, in the “strictly platonic” women-for-women (w4w) personals section of Craigslist. “Maybe it’s not working for me to the full potential since I’m not paying a membership to meet friends. WTF!”

In this strictly platonic section of Craigslist, a website now mostly associated with sublet searching, you’ll find some strictly not platonic ads, requests for non-sexual cuddle partners, and offers of “discreet massages.” You’ll even find some thinly veiled recruitment posts for escorts and offers from cocaine dealers. Stuck between all that sit earnest posts written by women who are just trying to make real, platonic connections.

If you’re a woman, meeting men on Craiglist is scary because you don’t know what they might do to you in real life (see: Craigslist Killer, now a Lifetime movie). And as a woman, meeting women on the internet is scary because they might be men. Navigating the platform is tough, but women in major metropolitan areas brave it because making friends in the real world, and even other online realms, can be tougher than making a date or arranging a liaison.

Many earnest posters, like “Looking for BFF,” feel the need to explain why they’ve decided to post on Craigslist. Another post in the “strictly platonic, w4w” section, simply titled “Friendship” and written by a 26-year-old woman, describes her reasons by detailing her current friend group’s pattern of last-minute plan cancellations. She also lists her interests (“frozen yogurt, celebrity gossip, going to the park”) along with what she’s looking for (“has a few of my interests, lives in New York, New Jersey, or Connecticut”). Her lax standards point to a simple need for friends with some follow-through, which is hard to find when technology makes it so easy to both flake on plans and find better ones at the last minute.

Others who post in the platonic w4w section have more specific benchmarks for new friends, like “Artistic Partner in Crime,” who wants someone to “make feminist horror stories with.” As for why she’s posting on Craigslist, she writes, “Well, hey, if there’s a better way to find a creative other half, I’m all ears, but Craigslist has a lot of traffic right?”

Craigslist’s factsheet says that the website gets “more than 50 billion page views per month” and has “more than 60 million [users] each month in the US alone.” Of course, not all are on there looking for friends. But that’s still more users than there are on dating-and-now-also-networking-and-friend-finding app Bumble, which boasted 18 million users as of July 2017, according to the Guardian. Meanwhile, Meetup, an online forum for organizing group events, puts its members number at over 32 million, spanning 182 countries.

“Bumble somewhat is [useful for finding platonic same sex friendship],” a 27-year-old, female Craigslist-poster wrote to me, “but I find most women there are more concerned with finding a date.”

The 27-year-old posted in the platonic section of Craigslist because she’d recently moved — a common reason women search for friends online. Kellie, a 38-year-old Brooklyn transplant from California, used to just use Craigslist for her work (she’s an artist) and for dating/sex before she moved to New York and started posting in the “platonic w4w” section. But in this category, she has “not had the best luck.”

“I have one friend that I met [on Craigslist],” she said. “He never wanted anything from me, it was only a friendship, and that was great so we’re still in contact, but I have no female friends here.” Most men end up looking for more than friendship, and some women, too. “I was texting with [a woman from Craigslist] a little bit, but she ended up becoming very needy … I felt she was never going to leave me alone if I [met her in person]— constant texting, constant.”

Kellie now also uses Craigslist to meet clients in her work as what she calls a “chronovendor,” meaning she sells her time — what others might call a sex worker. “I’ve been told that I’m orally gifted, so I thought, I wonder if I can capitalize on that,” she said.

While Craigslist may not have led to close, female friendships for Kellie, it got her a new job selling “time” and even her current, serious partner (from one of the non-platonic sections). Kellie embraces the platform to meet people for an adventure, but other women in Kellie’s age range aren’t looking to step far outside their comfort zones. Several women I spoke to between ages 30 and 50, all of whom use Meetup to find female friends in major cities, expressed hesitancy when it came to Craigslist.

“I just don’t want to put myself in any type of danger,” said Nikki, who’s in her 30s and started the Ladies Who Brunch NYC Meetup. She prefers Meetup because it’s an organization with accountability, just like Laura, who’s in her 30s and founded the Unruly Women’s Club NYC. Both Nikki and Laura are ex-pats from the UK, like a couple of other Meetup organizers I spoke to in New York.

“Being a Brit, we don’t have [Craigslist] over there, so all that I would ever hear is like ‘somebody got murdered’ or ‘somebody got assaulted,’” said Laura, who lives in Jersey City. “I maybe looked at it when we [she and her husband] first moved here, and there are so many quite sexually aggressive things and terrible spelling, and it feels completely unregulated.”

Stefanie Raya, who’s in her mid-40s and leads the Austin, Texas-based Meetup group Women & Wine, echoed this sentiment. She ultimately noted the absence of “someone like me or my caliber” on Craigslist. Instead, Raya looks to her own Facebook to meet new friends by messaging “friends” in her area whom she’s never met in person and asking them for coffee. This way, she’s sure to meet someone who’s more on her level.

All of these female Meetup organizers used the phrase “like-minded” to describe what they are looking for in female friends. Like-minded sounds easy enough to find on Meetup, where users post profiles and can search by type of event. On Craigslist, nothing but location and general posting category narrows down your search.

Maybe women looking for friends on Craigslist aren’t as focused on “like-minded” in their searches. Or perhaps what makes them like those who respond to their ads is their mutual willingness to use Craigslist to meet strangers. They’re open to taking risks and having adventures, like Kellie, and even SM, a 23-year-old woman who’s used the platform to talk to strangers about her sexual experiences.

Ultimately, what all these women — Craigslist, Meetup and Bumble users alike — have in common is a desire to find friends who won’t flake on them, or get too busy. Nikki’s problem with some women on Meetup is that they use the platform for “window shopping.” They poke around different profiles and groups but never commit to one.

“A lot of women forget the great things women do when they work together,” said Nikki. She, and other women forced to odd corners of the internet to make friends in hectic cities, just want to make those great things happen.

They thought they were going to rehab. They ended up in chicken plants

(Credit: Reuters/Mike Blake)

The worst day of Brad McGahey’s life was the day a judge decided to spare him from prison.

McGahey was 23 with dreams of making it big in rodeo, maybe starring in his own reality TV show. With a 1.5 GPA, he’d barely graduated from high school. He had two kids and mounting child support debt. Then he got busted for buying a stolen horse trailer, fell behind on court fines and blew off his probation officer.

Standing in a tiny wood-paneled courtroom in rural Oklahoma in 2010, he faced one year in state prison. The judge had another plan.

“You need to learn a work ethic,” the judge told him. “I’m sending you to CAAIR.”

McGahey had heard of Christian Alcoholics & Addicts in Recovery. People called it “the Chicken Farm,” a rural retreat where defendants stayed for a year, got addiction treatment and learned to live more productive lives. Most were sent there by courts from across Oklahoma and neighboring states, part of the nationwide push to keep nonviolent offenders out of prison.

Aside from daily cans of Dr Pepper, McGahey wasn’t addicted to anything. The judge knew that. But the Chicken Farm sounded better than prison.

A few weeks later, McGahey stood in front of a speeding conveyor belt inside a frigid poultry plant, pulling guts and stray feathers from slaughtered chickens destined for major fast food restaurants and grocery stores.

There wasn’t much substance abuse treatment at CAAIR. It was mostly factory work for one of America’s top poultry companies. If McGahey got hurt or worked too slowly, his bosses threatened him with prison.

And he worked for free. CAAIR pocketed the pay.

“It was a slave camp,” McGahey said. “I can’t believe the court sent me there.”

Soon, it would get worse.

Across the country, judges increasingly are sending defendants to rehab instead of prison or jail. These diversion courts have become the bedrock of criminal justice reform, aiming to transform lives and ease overcrowded prisons.

But in the rush to spare people from prison, some judges are steering defendants into rehabs that are little more than lucrative work camps for private industry, an investigation by Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting has found.

The programs promise freedom from addiction. Instead, they’ve turned thousands of men and women into indentured servants.

The beneficiaries of these programs span the country, from Fortune 500 companies to factories and local businesses. The defendants work at a Coca-Cola bottling plant in Oklahoma, a construction firm in Alabama, a nursing home in North Carolina.

Perhaps no rehab better exemplifies this allegiance to big business than CAAIR. It was started in 2007 by chicken company executives struggling to find workers. By forming a Christian rehab, they could supply plants with a cheap and captive labor force while helping men overcome their addictions.

At CAAIR, about 200 men live on a sprawling, grassy compound in northeastern Oklahoma, and most work full time at Simmons Foods Inc., a company with annual revenue of $1.4 billion. They slaughter and process chickens for some of America’s largest retailers and restaurants, including Walmart, KFC and Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen. They also make pet food for PetSmart and Rachael Ray’s Nutrish brand.

Chicken processing plants are notoriously dangerous and understaffed. The hours are long, the pay is low and the conditions are brutal.

Men in the CAAIR program said their hands became gnarled after days spent hanging thousands of chickens from metal shackles. One man said he was burned with acid while hosing down a trailer. Others were maimedby machines or contracted serious bacterial infections.

Those who were hurt and could no longer work often were kicked out of CAAIR and sent to prison, court records show. Most men worked through the pain, fearing the same fate.

“They work you to death. They work you every single day,” said Nate Turner, who graduated from CAAIR in 2015. “It’s a work camp. They know people are desperate to get out of jail, and they’ll do whatever they can do to stay out of prison.”

To unearth this story, Reveal interviewed scores of former participants and employees, court officials and judges and reviewed hundreds of pages of court documents, tax filings and workers’ compensation records.

At some rehabs, defendants get to keep their pay. At CAAIR and many others, they do not.

Legal experts said forcing defendants to work for free might violate their constitutional rights. The 13th Amendment bans slavery and involuntary servitude in the United States, except as punishment for convicts. That’s why prison labor programs are legal. But many defendants sent to programs such as CAAIR have not yet been convicted of crimes, and some later have their cases dismissed.

“You’ve got to be kidding me,” Noah Zatz, a professor specializing in labor law at UCLA, said when presented with Reveal’s findings. “That’s a very strong 13th Amendment violation case.”

CAAIR has become indispensable to the criminal justice system, even though judges appear to be violating Oklahoma’s drug court law by using it in some cases, according to the law’s authors.

Drug courts in Oklahoma are required to send defendants for treatment at certified programs with trained counselors and state oversight. CAAIR is uncertified. Only one of its three counselors is licensed, and no state agency regulates it.

The program mainly relies on faith and work to treat addiction.

Sharon Cain runs the drug court in rural Stephens County and decides where to send defendants for treatment. She said state regulators don’t stop her from using CAAIR.

“I do what I wanna do. They don’t mess with me,” she said. “And I’m not saying that in a cocky way. They just know I’m going to do drug court the way I’ve always done it.”

The American Civil Liberties Union of Oklahoma now is considering legal action in response to Reveal’s reporting.

About 280 men are sent to CAAIR each year by courts throughout Oklahoma, as well as Arkansas, Texas and Missouri. Instead of paychecks, the men get bunk beds, meals and Alcoholics and Narcotics Anonymous meetings. If there’s time between work shifts, they can meet with a counselor or attend classes on anger management and parenting. Weekly Bible study is mandatory. For the first four months, so is church. Most days revolve around the work.

“Money is an obstacle for so many of these men,” said Janet Wilkerson, CAAIR’s founder and CEO. “We’re not going to charge them to come here, but they’re going to have to work. That’s a part of recovery, getting up like you and I do every day and going to a job.”

The program has become an invaluable labor source. Over the years, Simmons Foods repeatedly has laid off paid employees while expanding its use of CAAIR. Simmons now is so reliant on the program for some shifts that the plants likely would shut down if the men didn’t show up, according to former staff members and plant supervisors.

But Donny Epp, a spokesman for Simmons Foods, said the company does not depend on CAAIR to fill a labor shortage.

“It’s about building relationships with our community and supporting the opportunity to help people become productive citizens,” he said.

The arrangement also has paid off for CAAIR. In seven years, the program brought in more than $11 million in revenue, according to tax filings.

“They came up with a hell of an idea,” said Parker Grindstaff, who graduated earlier this year. “They’re making a killing off of us.”

Janet Wilkerson had a problem. As vice president of human resources for Peterson Farms Inc., she was having trouble filling the overnight shift at her chicken processing plants. The hours were long. The pay was low. And there never seemed to be enough workers.

Then a convicted meth dealer named Raymond Jones walked into her office in 2003 with a story and a proposal, according to a newspaper story at the time. After finding Jesus, Jones had overcome his addictions and decided to start a rehab. He asked Wilkerson to take a chance and hire his men. They were cheap, he promised, and they could work all hours. Their wages would fund his recovery program.

Wilkerson eagerly agreed. She called the arrangement a “win, win, win” for the men, chicken plants and Jones.

She was so taken with the idea that four years later, she created a nearly identical program of her own.

Her brother had died from alcoholism, and her husband’s drinking had nearly destroyed their marriage. She had long wanted to help others like them. The economics also made sense. The chicken plants needed workers, and Jones’ program was bringing in revenue of more than $2 million a year.

Wilkerson had the connections to make it happen. In addition to working in human resources at Peterson Farms, she also moonlighted as a spokeswoman for Simmons Foods and other top poultry companies. Wilkerson enlisted her assistant and another poultry executive and brought Jones along as a $250,000-a-year consultant.

Then she pitched the idea to her bosses. The companies wouldn’t have to pay workers’ compensation insurance, payroll taxes or medical care. They could replace the workers for any reason at any time. Like a temp agency, her program would pay for everything; the men just needed to work.

Simmons signed on. Later, Crystal Lake Farms and Tyson Foods Inc. did, too.

Jones agreed to introduce Wilkerson and her business partners to court officials. But his reputation was deteriorating. Plant supervisors said Jones’ workers sometimes would show up high. Workers complained that Jones wasn’t feeding them.

Wilkerson vowed to make her program better. She and her partners hired away one of Jones’ top managers and used men from his program to build their first dormitory. They worked for free, as community service. Then she stopped paying Jones and they parted ways.

By 2010, hundreds of men poured into CAAIR from courts across Oklahoma. So did the money, allowing the Wilkersons – Janet as CEO and her husband, Don, as vice president of operations – to draw combined salaries of $168,000 a year, nearly four times the median household income in their area.

That’s when Brad McGahey arrived.

At Simmons Foods, McGahey first went to work in evisceration, suctioning guts and blood out of slaughtered chickens speeding past him on metal hooks. Then he became a grader, arranging raw breasts, thighs and legs into orderly piles as they moved up a conveyor belt to packaging. It was monotonous work.

Growing up in the country, McGahey wasn’t bothered by the sight of dead animals. He’d gutted catfish and skinned deer all his life. But the first time he stepped into the Simmons plant, the stench of chicken blood and feces was overpowering.

“I almost threw up,” he remembered.

On May 27, 2010, three months into his time at CAAIR, something went wrong.

A machine dumped a mountain of parts onto the conveyor belt, causing chicken to pile up faster than he and his co-worker could sort it. As they plunged their hands into the heap of cold parts, McGahey remembers hearing a scream. His co-worker’s rubber glove was caught in the conveyor belt.

McGahey grabbed the woman’s arm, wresting her hand free. But the machine snagged his own hand. In a matter of seconds, McGahey’s wrist was jerked backward, lodged in the seams of the conveyor belt as it hurtled toward a narrow stainless steel chute overhead. Someone yanked the emergency kill cord, which should have stopped the machine, McGahey recalled. But it raced upward, dragging him along with it.

He felt a flash of panic. Then an excruciating crunch.

Medical notes later would say McGahey suffered a “severe crush injury.” The machine smashed his hand, breaking several bones and nearly severing a tendon in his wrist. When he finally yanked his wrist free, his hand was bent completely backward. The pain was so bad that he nearly fainted.

A nurse at the plant took one look at him and called CAAIR.

“The kid’s hand is mangled!” he recalled the nurse screaming into the phone. “He needs help!”

McGahey expected an ambulance. Instead, one of CAAIR’s top managers picked him up at the plant and drove him to the local hospital. Doctors took X-rays of McGahey’s hand, gave him a splint and ordered him not to work.

Back at CAAIR, he spent a sleepless night cradling his throbbing hand. He figured it would take months to heal and planned to rest. But CAAIR’s administrators would have none of it.

They called McGahey lazy and accused him of hurting himself on purpose to avoid working, former employees said. CAAIR told him that he had to go back to work – either at Simmons or around the campus until his hand healed, which wouldn’t count toward his one-year sentence.

Wilkerson said she doesn’t remember the specifics of McGahey’s case but acknowledged that CAAIR has given such ultimatums before.

“You can either work or you can go to prison,” McGahey remembered administrators telling him. “It’s up to you.”

He already had made up his mind.

“I’ll take prison over this place,” he said. “Anywhere is better than here.”

Most men sent to CAAIR are addicted to alcohol, meth, heroin or pain pills. They are usually young, white and can’t afford stays in private rehab programs.

Inside CAAIR’s dormitories, Bible verses and Simmons Foods posters line the walls. Participants usually sleep six to a room, crammed onto wooden bunk beds. They attend church services in a common room down the hall, decorated with quilts and wooden crosses.

During the one-year program, the men can’t have cellphones or money. If they relapse or break the rules, they can be kicked out or punished with extra time. In 2014, CAAIR reported that about 1 in 4 men completed the program.

Former employees said work takes priority over everything. If counseling or classes interfered with the job, the decision was clear. “It’s work,” said Aaron Snyder, who participated in the program and later worked as a dorm manager. “You’re going to work.”

The men also perform free labor for CAAIR’s founders, family and friends. A group of men said they helped remodel the Wilkersons’ master bedroom. Another said he helped one of their daughters pack boxes and move. Still others worked on an egg farm owned by the Wilkersons’ other daughter. The program told the courts that it was community service, according to employees.

The strict regimen has helped some men get clean. Those who arrive without a home, steady employment or food said they find their basic needs met at CAAIR. Those who complete the program without breaking any rules are eligible for a gift of $1,000 when they graduate.

“I have to say CAAIR was the hardest thing to do in my life,” said Bradley Schott, who graduated in 2014. “I went to basic training at 16. And (Army) Ranger school. And it wasn’t as hard as CAAIR, mentally or physically. But it saved my life.”

Jim Lovell, CAAIR’s vice president of program management, said there’s dignity in work.

“If working 40 hours a week is a slave camp, then all of America is a slave camp,” he said.

Men who were injured while at CAAIR rarely receive long-term help for their injuries. That’s because the program requires all men to sign a formstating that they are clients, not employees, and therefore have no right to workers’ comp. Reveal found that when men got hurt, CAAIR filed workers’ comp claims and kept the payouts. Injured men and their families never saw a dime.

Brandon Spurgin was working in the chicken plants one night in 2014 when a metal door crashed down on his head, damaging his spine and leaving him with chronic pain, according to medical records. CAAIR filed for workers’ compensation on his behalf and took the $4,500 in insurance payments. Spurgin said he got nothing.

Janet Wilkerson acknowledged that’s standard practice.

“That’s fraudulent behavior,” said Eddie Walker, a former judge with the Arkansas Workers’ Compensation Commission. He said workers’ comp payments are required to go to the injured worker. “What’s being done is clearly inappropriate.”

Three years later, Spurgin’s still in pain and can no longer hold a full-time job.

In addition to injuries, some men at CAAIR experience serious drug withdrawal, seizures and mental health crises, according to former employees. But the program doesn’t employ trained medical staff and prohibits psychiatric medicine.

A judge in Tulsa sent Donald Basford to CAAIR in 2014 despite a documented history of severe mental health problems. The 36-year-old quickly unraveled, repeatedly complaining to staffers that he was “losing it” without his medication, Snyder, the former employee, recalled.

Basford ran away and was found dead inside a car in a church parking lot a few weeks later, according to an autopsy report. Medical examiners found no drugs in his badly decomposed body and weren’t able to determine Basford’s cause of death.

Other CAAIR men who had mental breakdowns or manic episodes were kicked out, according to former employees, opening the door for them to be sent to prison.

“You just don’t do that to people who obviously need some kind of help,” Snyder said. “It’s not right.”

When the Oklahoma Legislature created the state’s drug court requirements 20 years ago, it was part of a growing realization nationwide of the costs – both financial and human – of handing down long prison sentences for drug-related charges.

In drug court, judges are required to put defendants through treatment rather than prison. Follow the rules, and defendants can have their cases dismissed.

Lawmakers wanted to ensure the quality of treatment, so they wrote an important provision into state law: Drug courts must use treatment providers inspected and certified by the state Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services.

But affordable treatment is in short supply. Drug court defendants have waited up to nine months for a bed in a residential treatment facility, meanwhile relapsing or languishing in jail. As a result, some courts turn to uncertified programs such as CAAIR, even though it might violate the law, according to the law’s authors.

“That is insanity gone to sea,” former state Sen. Dick Wilkerson said when told of Reveal’s findings. (He is not related to CAAIR’s founder.) “That’s illegal. They can’t do that. That is the law, and it has to be followed.”

In Pontotoc County, Judge Thomas Landrith sometimes uses CAAIR in place of certified treatment. He said there’s never a wait list, and it costs the courts and state nothing.

“We tried to get residential treatment programs down here, but we never could really pull it off,” he said. “So recovery programs kind of fit that niche.”

Other judges said they were unaware of the law or have found ways around it.

Tulsa’s drug court, which sends the most defendants to CAAIR, said the law permits judges to use uncertified programs, as long as it’s not for treatment.

“The referral is to assist the participants in developing good job skills, life skills, work ethics and personal care skills,” said Vicki Cox, court administrator. “Participants are not sent to CAAIR for drug or alcohol treatment.”

But Reveal found that Tulsa’s drug court staff repeatedly described CAAIR as treatment in court records. Cox dismissed that as a record-keeping error.

Oklahoma’s Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services funds and monitors drug courts. The agency knows that judges are using uncertified providers such as CAAIR, but officials say there’s little they can do. All they can do is cut some of the funding to drug courts that use those programs. But that’s little disincentive to judges.

No drug court judge has ever been disciplined for using uncertified programs, according to the Oklahoma Council on Judicial Complaints.

Brad McGahey went straight from CAAIR to a Marshall County jail cell. Because he failed to complete the program, he had violated the rules of his probation. The judge sentenced him to a year in state prison.

McGahey was released after two months due to prison overcrowding.

His injury had not improved. One minute, his hand throbbed with pain. The next, it tingled and went numb. Sometimes it turned blue.

He found a lawyer and went to court for workers’ compensation. The process was slow, and CAAIR fought him every step of the way. In court in 2012, the program’s attorneys argued that McGahey’s recurring symptoms weren’t the result of the accident in the chicken plant.

“If you want to get a lie detector test up here, I’ll pay for it,” McGahey blurted in the middle of his testimony. “I know what happened. … I ain’t no liar, and you’re calling me one.”

The judge sided with McGahey. “Sounds like you’ve succeeded successfully in delaying the treatment for this person, counselor,” the judge told CAAIR’s attorney.

Three years after the accident, McGahey finally got his surgery. But it didn’t help.

“I believe that we got to Bradley so late in his treatment … that Bradley is going to have a permanent problem with his hand,” the doctor wrote in a status update to the court in September 2013.

McGahey grew depressed. He sold his four-wheeler to pay off his $500-per-month child support debt. He tried welding for two weeks, but his hand injury got in the way. He sought out other opportunities, such as trading and selling used cars, junk and metal. But something always went wrong, and he got into more trouble with the law.

When CAAIR’s attorney offered a settlement, McGahey took it. In 2014, he got a lump sum of $11,000.

But today, the pain persists. All that seems to help, McGahey says, are pain pills.

Every morning and throughout the day, McGahey chugs a can of Dr Pepper with hydrocodone pills. When his doctor cut him off from his various medications, McGahey found another doctor to write a prescription.

Before CAAIR, McGahey had no interest in drugs. Now, he says he can’t live without them

“I’m addicted to them pills,” McGahey said. “I have to take them.”

As McGahey sat on a plastic chair in front of his mother’s house, littered with items scavenged from garage sales, he remembered when he still had the use of two hands, when he was good at rodeo and could work on his family’s farm.

“When you can’t do something you love and it’s the only thing you ever known, then it’s taking part of your life away from you,” he said. “I’ve accepted it now and learned how to do with what I got. I just don’t want to see it ruin somebody else’s life.”

Courts still send defendants to CAAIR, and the program is expanding. Simmons Foods even donated funds for a third dormitory to house dozens more men.

“I was walking in the parking lot of the Simmons plant, and (Chairman) Mark Simmons told me he needed more men,” Wilkerson told a local reporter at the ribbon-cutting ceremony in 2015. “I told him to build me another dorm.”

CAAIR is now planning a fourth dormitory. It’s supposed to be the biggest yet.

October 14, 2017

Sleeping on your back increases risks of stillbirth

(Credit: Anna Jurkovska via Shutterstock)

Pregnancy and Infant Loss Awareness day on Oct. 15, 2017 draws our attention to a bleak statistic — an estimated one in four pregnancies end in a loss. Many of these are early miscarriages. But in Canada about one in 125 pregnancies end in a stillbirth — that is, the death of a fetus in utero after 20 weeks gestation.

Countries such as Korea and Finland have much lower rates of stillbirth, so we know that there is more we can do to prevent it. There is research on the risk factors that increase the chances of a stillbirth. Yet many pregnancy guides do not give enough information about stillbirth, in the belief that women do not want to be frightened about pregnancy loss.

Information about how to prevent stillbirth needs to get into the hands of women who need it, even if it leads to an uncomfortable conversation. As a medical librarian, my job is to connect people to trusted information about their health. When dealing with a taboo topic, such as stillbirth, this is even more challenging as both health care providers and women might be afraid of increasing anxiety, rather than improving health.

We also want to ensure that women who have had a stillbirth in the past and may have slept on their back do not feel guilt over doing so. I know, because I myself have had a stillbirth. With the passage of time, I cannot honestly answer how I might have slept that night when my twins died, but it is still something that worries me.

While some risk factors are not things most pregnant women can change, there are two very simple things women can do, to lower the odds.

1. Count the kicks

There are two methods described in the medical literature about how to count your baby’s kicks: the Sadovsky method and the Cardiff method. In the Cardiff method, you count 10 movements and record how much time it takes for you to reach 10. In the Sadovsky method, you are asked to count how many movements you feel within a specific time frame, usually 30 minutes to two hours. In either case, the most important consideration is that you should be aware of your baby’s normal movements.

Any decrease in fetal movement should prompt a phone call or visit to your health care provider immediately. We don’t shame people for seeking medical advice when they have chest pains. Reduced fetal movements are similar to chest pains — a warning sign that something could be wrong. See your doctor or midwife and don’t delay or feel guilty for taking up their time!

2. Don’t sleep on your back

At last month’s International Stillbirth Alliance conference, several researchers presented information to show that back sleeping increased the risk of stillbirth.

In the first study, researchers in New Zealand put 10 pregnant women who were otherwise healthy into MRI scanners, to see if they could see changes in blood flow when they were lying on their backs or on their left side. They found that cardiac output (how efficiently the heart pumps blood) was the same in both positions.

However the blood flow and diameter of the inferior vena cava were reduced when lying on their backs. This affects how blood flows back to the heart from the body. The researchers speculate that this might contribute to stillbirths in some instances.

The second study, also from New Zealand, placed 30 pregnant women in a sleep lab. They monitored their breathing and position throughout the night to see if there was a relationship between lying on their backs and measured breathing. While none of the women met the criteria for sleep apnea, they didn’t breathe in as deeply when they were lying on their backs.

Lastly, researchers in the UK interviewed over 1000 women about their sleep practices before pregnancy, during pregnancy and the night before their stillbirth (for those who had suffered one) or the interview (for women who had not suffered one). The women who had gone to sleep on their backs while pregnant were twice as likely to have had a stillbirth then women who had gone to sleep on their left side.

All of this was a follow up to earlier research which had proposed the same hypothesis, that sleeping on your back increased the risk.

Women need accurate health information

Delivering timely information to prevent stillbirth is important, and withholding information out of a fear you’ll frighten women is patronising at best and potentially dangerous at worst.

What’s more, witholding information does little in an era where most people can get online and are not always equipped to evaluate what information is useful and how to put it into context. Health care providers can do more to partner with librarians on delivering evidence-based information to their patients. This is certainly true with information about pregnancy, but also in many areas of health where the information that needs to be delivered is complex, and requires more time to be evaluated than is available to most doctors.

Women deserve better communication about their health and the health of their babies when pregnant. While counting kicks and sleeping on your left side aren’t a guarantee that you’ll have a safe and healthy pregnancy, they are easy, low cost ways to reduce the risk.

Women deserve better communication about their health and the health of their babies when pregnant. While counting kicks and sleeping on your left side aren’t a guarantee that you’ll have a safe and healthy pregnancy, they are easy, low cost ways to reduce the risk.

Amanda Ross-White, Health Sciences Librarian, Nursing and Information Scientist, Queen’s University, Ontario

Ask your kid’s school these essential student privacy and safety questions

(Credit: iStockphoto/skynesher)

Some schools use a little technology: a few educational apps to mix things up, maybe a weekly trip to the computer lab. Some use a lot: one-to-one device programs, class management systems, and automated grade-reporting. Many districts are even adopting schoolwide networks with names you’ll recognize, such as Google Classroom and the Facebook-engineered Summit Learning System. Time will tell if all this technology better prepares students for a digital world. But one thing is true: If it’s digital, it uses data, and that means your kid’s information is more valuable — and more vulnerable — than ever. Schools need to safeguard student privacy as fiercely as a mama bear — and you, as the parent, need to know how they’re doing it. Here are the right questions to ask, and the answers you should expect, to make sure any tech your kid uses at school is protecting your kid’s privacy.

How does the school decide if the educational software or apps it uses protect my kid’s privacy?

Your kid’s school should review the privacy policies of any software or device that requires your kid to log in with a screen name and password. You can ask for a copy of the product’s privacy policy, or you can talk to the teacher or your principal to get assurances that they know what they’re doing.

What you should hear in the school’s answer:

Stored data is encrypted, password protected, and only available to certain administrators who need it for educational purposes. Ask who that person is.

Companies don’t collect more information than they need for educational purposes — and those reasons are clearly and narrowly defined. Keep an eye out for requests for personal information that don’t seem relevant to education (for example, your religious beliefs).

Companies don’t trade or sell student info to others. If you suspect your kid’s information has been sold (because you’re receiving ads in the mail, etc.), notify your school administrator.

More than one person (for example, a teacher, administrator, and an IT professional) reviews the companies’ policies. Ask for their names in case you need them.

Even better: The company supplying the software has undergone some sort of third-party vetting or evaluation process — such as the evaluation offered by Common Sense Media’s Privacy Initiative. The list of companies and software used is frequently updated and accessible to parents and students. Find out where the list is.

What information does the school collect and how is it stored?

Schools need to offer a clear educational purpose for any personal information it asks for. (Social Security numbers are an example of information many schools have collected in the past, but not any longer because they couldn’t justify the educational purpose of collecting that data.)

What you should hear in the school’s answer:

The school asks for basic identification only — for example, name, address, and phone number.

The school encrypts any information it receives and uses security procedures to protect any data in transit. That means no one can read the information without authorized security clearance and a password. Ask how they do this.

Even better: The school restricts access to information solely to those who need to know it — for example, only a school nurse has access to medical information, via passwords, technical controls, or other physical safeguards. The school deletes information once it is no longer needed for your kid’s education or required to be kept by state or federal law. Ask exactly when your kid’s information will be deleted.

Who can get access to the school’s list of students and their contact information?

Federal law limits who can get access to a school’s directory of basic stuff like your kid’s name, address, telephone number, and other general information.

What you should hear in the school’s answer:

Schools comply with the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) by notifying parents of any information that they collect and what directory information includes, as well as providing parents the choice to to opt out.

The method of notification is up to the school, so ideally they should use methods that will get your attention, such as a letter sent home that you have to sign. Ask how they notify parents: by email, a letter home, etc.?

Even better: Under FERPA, schools are actually allowed to disclose certain directory information without your consent. A yearbook publisher, a class-ring manufacturer, and military recruiters are a few examples of outside organizations to which the school can send directory information. But some of this information is fairly personal, including place of birth, honors, awards, and dates of attendance. A school that’s being careful will ask for consent before disclosing this or any other information. Ask if your school does this.

How do I provide consent for my student to use software at school?

The school, the district, or an authorized teacher should ask parents to provide consent if any software or applications used in the classroom will collect information from students. Any notice to parents should include how they can provide consent and what practices they are consenting to.

What you should hear in the school’s answer:

Ideally, schools offer easily accessible and flexible opt-in and opt-out consent options — not merely one blanket form that opts you into, or out of, everything.

Some schools offer a checklist that lets you choose which information to share with which third parties. For example, you may feel comfortable sharing your student’s name and address with the developer of your kid’s reading software application, but you may not feel comfortable sharing your student’s dates of attendance.

Or even though the school is allowed to share directory information with your kid’s after-school program, it gives you the option not to. Ask how your school manages distributing this information.

What’s the school’s policy on Bring Your Own Device (BYOD)?

BYOD programs are a lower-cost way for schools to integrate technology into the classroom. But tablets and laptops store a lot of sensitive information, including personal data (name, address, etc.), raw data such as performance reports, and “cookies” — the personal identifiers that track your student’s path around the internet. Also, many students may not have reliable broadband internet access at home in which to complete online assignments, so BYOD should be used in conjunction with other programs at school.

What you should hear in the school’s answer:

The school vets the privacy policies of all third-party programs installed on your student’s devices and makes sure that they comply with the Children’s Online Privacy and Protection Act (COPPA). Look up any app the school recommends on Common Sense Media or Common Sense Education to double-check its practices.

Even better: The school doesn’t have the right to search your student’s device, use monitoring software, track its location, or remotely access the device’s camera. Ideally, the school uses a separate wireless network for students than for teachers, which adds another layer of security to students’ information. Ask if they follow these privacy and security best practices.

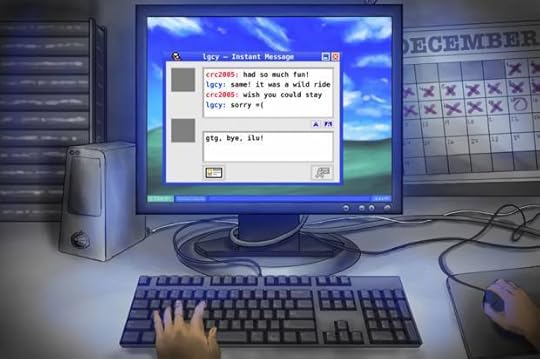

My so-called online life: Coming of age in the AIM era

Old School AOL Instant Messenger (Credit: Salon/Ilana Lidagoster)

I’m in the dark family room, bouncing on my heels in the computer chair, leaning toward the monitor, slugging a can of Halfway to Heaven — the nickname the girls I’m IM-ing have for Diet Mountain Dew. My dad is on the couch, and I shrink the chat windows whenever I hear his knees creak. On TV, “Top Gun” plays on mute; by the mantle, the Airedale sleeps; the only sound in our house beside those knees is my fingers staccato on the keyboard.

“That’s all homework?” my dad asks during a commercial. “What are you doing, Jo?”

Jo? I think. Who’s Jo?

My first AIM username was Gucci60525 — my zip code plus a nod to “Spiceworld” (“Should I wear the little Gucci dress, the little Gucci dress, or the little Gucci Dress?”). When I outgrew Posh Spice, I slunk into Hollygolightly6985; with the release of “Man on the Moon,” I goofed into Kaufmaniac6985; when I’d memorized “American Beauty,” I snagged Spacey6985. My last username was pennylane6985: equal parts The Beatles and “Almost Famous.” By that time — I was a junior in high school — I’d traded the Halfway to Heaven for espresso and vanilla cloves.

* * *

The news arrived last week, as unwelcome as a chat invite from your best friend’s mom: AOL was shutting down AIM, its messaging service. Cue sign-off sound effect, the Internet responded, eulogizing the service that introduced the world to buddy lists, away messages, and profiles, with a pastiche of levity, longing and lovingly-excavated personal ephemera. The tributes are warranted. AIM paved the way for text messaging, Facebook, and beyond — all without (at least in the earliest years) profile pics. In “The Rise and Fall of AIM, the Breakthrough AOL Never Wanted,” Jason Abbruzzese reported that, at its peak, AIM drew “as many as 18 million simultaneous users.”

I learned from Abbruzzese that a subset of those users worked on Wall Street. This surprised me until I realized what young women like me, who were becoming teenagers at the end of the ’90s, had in common with those brokers: We too were trading futures and commodities, but on AIM the potential gains were our teenage selves.

What does it mean when a technology that shaped your identity dies? Who did we become as users of those technologies? And what does it mean now that our messaging is stitched to our phone numbers, our Facebook profiles, our flesh-blood-and-birthdate selves? Perhaps it’s easy to dismiss our AIM ancestry, merely a blip in the Intro to Social Media textbooks. Maybe it’s tempting to consider our emo away messages with bemusement (I’m looking at you, Wall Street), our screen names with a *head slap* — until you remember that all we had were away messages and usernames. I fear being so flip with the tools I — we — used to construct our most intimate identities.

I fell in love with two kinds of people on AIM: vaguely athletic nerd-boys and girls with eating disorders. My buddy list was filled out by others — the cool kids I knew in AP Art History, the runners who inside-out French-braided my hair before meets — but the anorexic girls I counted as my best friends and the boys I liked were the people I wanted to talk to, along with the “fishys,” a subset built out of the pro-recovery eating disorder website Something Fishy, women across the country whose lives, like mine at the time, were ruled by scales, laxatives and therapists.

Illness was one common tongue; sex was another. As a young woman, AIM helped me be fluent in both. It let a generation communicate in ways that would’ve been mortifying, sappy, or straight-up taboo in high school, that big top of real life.

* * *

In the summer of 1999, before I began ninth grade, I took a typing class. The instructor sidled behind the swivel chairs, watching our hands beneath cardboard boxes designed to hide the keyboard. You stuck your hands in like Audrey Hepburn tempting the oracle in “Roman Holiday”; you hoped you knew home row, had learned the raised dash on the letter J.

That class taught me to type fast, but AIM taught me to type faster. I had to keep up when MacRed451 called me “Babe.” (He was my best friend’s cousin, his screen name a result of the self-reported fact that he enjoyed “macking” on the ladies.) I liked how InchoatusMcGee sent passages from John Irving novels, and I liked responding with debased lines from the annals of Henry Miller. At the same time, ElleGirl40 might be telling me about the lock her parents affixed to the medicine cabinet. PurpleHaze203 would be sending pain-stoppering lyrics from the Black Crowes: sometimes, we took our correspondence offline, and she sent me long letters on paper licked with marijuana smoke and cotton candy perfume.

She didn’t sound so stressed about her eating disorder away from AIM. I noticed how, when I was depressed, I showered a lot in real life; on AIM, I tried to talk about it.

Depressed, starving, smart, bookworm, babe: I could be many versions of myself when I was IM-ing, and I could cultivate each one with the sort of care there wasn’t room for in high school. You didn’t have that freedom when you passed a note; there wasn’t the same thrill of anonymity over the phone. Real life was a rush, but AIM invited you to think on the fly. Wittiness, sarcasm and sagacity were rewarded. The banter reminded me of a game my brother and I used to play in the family room, when we were home alone: Don’t Touch the Ground.

You moved one piece of furniture to the next, watching normal things like couch arms and chair backs morph beneath you.

Words did that on AIM: they changed, grew potent, gathered a charge. Words that sounded dumb in real life could be sexy (like babe); words that would be hard to utter over the phone (like, I threw up my dinner) appeared in the chat window as though from another pair of hands. Words grew, too. When my friends and I began dating, we developed a color code so we could report on our sexual activities. Pink was kiss.

And words could stand in for things I’d never do or say in real life. ((hugs)), I’d type to the Fishys, even as I knew, if I ever were to meet any of them, I’d be terrified to crush them. “Tell me what it’s like to masturbate,” I’d ask the guy friends I knew liked moxie. I heard about vacuum cleaners, mirrors, shampoo bottles, feeling powerful and strange. Of course, nothing was going to happen as a result of these interactions — right? — but it felt like anything could.

* * *

It’s hard to shake the tastes you develop early. Even today, a message from a certain guy friend or a woman (always with an eating disorder) will leave me staring at my phone screen, heart pounding, wishing I could see if I’d made a shrouded cameo in their away message.

My friends and I saved our chats in a folder in our email. We printed them out and studied them at sleepovers like we were annotating “Lady Lazarus” or acting out “Cosmo Confessions.” Juicier than the messages we received from boys were the phrases that sprung from our keyboards, those impulse-cured expressions of our most ardent hearts.

It was good to be sardonic and sincere, flirty and vulnerable. It was good to feel that our identities were tied to our bodies when, on AIM, our bodies were invisible. The newness of this made even the frightening realities of being a young woman less perilous: PrettyInPink700 told me how a guy fingered her on the catwalk stretching over the Stevenson toll way; another, Cinderstella14, flirted her way into a phone call with a 34-year-old man.

Of course, my parents detested it. Recently, I spoke with my mother, who confessed that she’d asked my father and my uncle to retrieve my messages from the hard drive of the family PC. The two of them — engineers both — failed. What would they have seen had they succeeded? A lot of ellipsis. A lot of swearing. Every color in the rainbow (plus black and gray). Song lyrics, novel quotes, admissions of love, lurf and luff.

When my mother told me about the snooping, my whole spine bristled, the way it would, 15 years ago, when I sensed my father stirring as I typed. I didn’t tell her that. She had been worried about me, she said, and I couldn’t blame her. Then her voice changed; I could tell she was as disappointed because she sighed. *Le sigh* my friends and I used to write on AIM. *Le sigh.* My mother sounded older, beat, the way I felt. “When you closed out of those windows, everything was gone.”

How “customer experience” became crucial to online business

(Credit: AP Photo/Ted S. Warren)

Annual online retail or “e-tail” sales now exceed $19 billion in Canada, AUS$21 billion in Australia, US$410 billion in the United States, and US$1 trillion in China.

In the United States, conventional retail is growing but e-tail is growing four times as fast. Amazon already captures 43 per cent of American online retail sales, and it continues to expand into new retail categories, such as groceries, and new countries, including Australia. Other e-tailers such as Wish are also growing rapidly.

In response, brick-and-mortar retailers are enhancing their online offerings. For example, Walmart and Loblaws now allow customers to “click-and-collect” by buying online and picking up their purchases in-store.

But e-tail isn’t easy. One challenge is foreign competition. Statistics Canada reports that 40 per cent of Canadian online sales come from foreign sources. That could increase if the renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement winds up raising online duty-free limits.

For e-tailers, growth is not simply a matter of advertising more through Facebook or Google keyword searches. The fundamental problem is that only 2.5 per cent of retail website visitors purchase something.

Converting those browsers into buyers is difficult. To succeed, retailers need to tailor their websites and strategies to their target customers, whether they’re across town or across oceans.

Confident and trusting consumers?

The foundation for successful online retail is consumer confidence and trust. A multi-nation study, carried out by researchers from the Goodman School of Business at Brock University, found that consumers who feel confident using the internet generally view e-commerce more favourably. Likewise, consumers are more likely to buy from e-tailers they trust. If consumers lack confidence or retailers have bad corporate reputations, those must be fixed first.

With that foundation in place, companies can then turn their attention to the way their websites are designed. To encourage online shopping, websites should be useful: Do they have the products customers want? They should also be user-friendly: Is it easy for customers to find products and place orders?

For consumers with ample internet experience, usefulness has a greater impact on purchasing. For those with less experience, user-friendliness is more important.

Fun or functional designs?

Beyond those basics, web designers must make many other decisions. Another study shows the “best” choices depend on customers’ needs and wants.

For example, some consumers want to experience a sense of growth and accomplishment. These shoppers prefer web pages with colourful pictures and emotional language. They also like descriptions of the product’s performance or the pleasure it offers. Their favourite e-tail sites combine these features to make shopping fun.

The movie section of the Google Play store is a good example of pleasure-oriented design. Shoppers can watch previews, read and write reviews and rent movies.

By contrast, some shoppers say they want their shopping experience to feel secure and responsible. They want to avoid negative outcomes, such as accidentally ordering the wrong size or version of a product.

These negative-avoiding shoppers prefer pages with practical layouts and clear menus. They also like descriptions that emphasize product functions and reliability. Their favourite sites make shopping efficient.

Amazon’s site fits into this category. It offers many ways to search for products and suggests additional related products the shopper may like.

The best retail websites focus on one shopper type or the other — they don’t try to please both. Some customers dislike seeing the other type’s features, or get confused by the contradictions between them. For example, negative-avoiding shoppers not only prefer seeing more functional features, they also prefer seeing fewer fun ones.

Retailers wanting to reach both groups may need multiple sites. For example, Dell has different designs for its business and consumer web pages.

Available or habitual?

Online retailers should also support shopping via smartphones and tablets to build their business. Mobile or “m-commerce” offers consumers even more access or “ubiquity,” allowing them to shop for anything, anywhere, anytime. But research published earlier this year indicates that the best way to promote these services depends on customers’ previous m-commerce experience.

Some customers are relatively inexperienced with mobile shopping. To reach them, retailers’ advertising should explain the availability and convenience this service offers.

Retailers should engage with experienced mobile shoppers more directly, so that it becomes a habit. These consumers take availability as a given and respond to nudges like coupons, memberships and reward programs. Amazon Prime is a great example of this approach. The goal is to keep people coming back often, and inspire their friends to shop too.

Basic marketing, updated

While online shopping behaviours do vary from country to country, what matters more to e-tailers are the features of the individual market segments. For example, some developed countries, such as Canada, still have consumers with little e-commerce experience. Likewise, some consumers in less developed countries, such as India, are sophisticated online shoppers.

Even with the latest trends and technology, retailers still need to know their customers to be successful. But e-tail requires the retailer to know a different set of things about their customers and to use different methods. The winning e-tailers will be those that use targeted offerings — whether through design or incentives — to capture consumers’ hearts and minds.

Even with the latest trends and technology, retailers still need to know their customers to be successful. But e-tail requires the retailer to know a different set of things about their customers and to use different methods. The winning e-tailers will be those that use targeted offerings — whether through design or incentives — to capture consumers’ hearts and minds.

“We could all be potential refugees”: Ai Weiwei on the epic journey of “Human Flow”

An old woman in Kutupalong-Camp in Ukhia, Bangladesh in "Human Flow" (Credit: Amazon Studios)

In a statement by Ai Weiwei regarding the selection of his documentary “Human Flow” for the 44th Telluride Film Festival, he wrote, “I grew up living as a refugee within my own country. As a young man, I participated in the first student movements demanding democracy and artistic freedom in China.”

Ai’s statement further explains that he has been an activist for several years. “In 2011, I was arrested and secretly imprisoned for 81 days by the Chinese authorities and falsely accused of crimes. For five years my passport was withheld from me and I was prohibited from leaving China, all the while living under constant government surveillance.”

These facts are not mentioned in “Human Flow,” but the film — an intimate epic — is influenced by them. Ai shot 900 hours of footage and conducted 600 interviews over the course of a year, and edited the film over six months. His lyrical and raw documentary takes a quiet, contemplative approach to the complex topic of people who leave their homeland to escape persecution. As one interviewee eloquently states, “No one leaves their country lightly.”

“Human Flow” is at once observational, impressionistic and immersive. The film features overhead shots that make refugees in a camp seem like ants in a colony, then zooms in to the reality on the ground.

Ai offers portraits of individuals and close-ups of children that illustrate the humanity, shame, dignity and pride as they struggle against the elements and disease. There are long tracking shots of refugees marching down a street, glimpses of detention centers and vivid images of Africans crammed in a too-small boat.

There are two scenes in this sprawling, extraordinary documentary that are especially notable and emotional. One involves Ai exchanging a passport with a refugee named Mahmoud; the other has the filmmaker comforting a woman who is seeking asylum. These, along with many other moments in the film, put a face on those who are often rendered nameless in news coverage.

Ai met with Salon at the Telluride Film Festival to discuss “Human Flow.”

What I most admire about your film is the approach you took to making “Human Flow.” Can you talk about how you designed the film and how it would look or “feel?”

Thank you. It’s not a historical kind of film. It’s really about personal moments. My early experiences were with my father, who was exiled for 20 years because he was a poet. I grew up in a kind of camp. We had to dig a hole in the earth. We stayed in that kind of condition for five years. My father started cleaning the villagers’ toilets. He was seen as someone who doesn’t belong to the society. My classmates would throw stones at my father. That connection maybe gives me a sensitivity about a huge amount of people being pushed away from their homes and having to find a new location. Their journey is about who they are, why they become like this, and is there any possibility for them to survive this?

There is very little knowledge about global politics when you come from a communist society like China, where education and information is limited. But as an artist, I have so much curiosity, and I have long fought with authoritarian societies for freedom of speech, so I wanted to learn more. The film was my journey to visit those places and get the history and literature and poetry, and the statistics from the U.N. and human rights organizations and the news. I read all the news about refugees — that’s how I started.

From the beginning, I sensed this is a topic that is much greater than I am capable of doing as an individual. But I wanted to get involved. I wanted to jump in.

I remember the first time I went to Lesbos [Greece] and we took a boat out and saw a dinghy in the middle of the ocean. We approached it and I asked the captain if I could jump into the boat. Half of the air had disappeared, but he said okay.

I was sitting in the boat, and it was safe, though people had already been rescued, or gone, or disappeared into the ocean. I saw this children’s milk bottle, a Bible, some wallets, right in the middle of the ocean. I got a sense of what it’s like to be someone in this same condition, trying to escape and survive. That moment, I said, I have to set up a camera team in Lesbos and start to record everything. We never saw this as a feature film. We just wanted to record it as evidence.

Yes, evidence. There was an art exhibit you once made that featured refugees’ shoes. It gave you a real sense of the human element.

Once you see them, you are terribly shocked by the situation but also touched, because they are so human. Look at their eyes, how they deal with their children or carry older people on these journeys. It’s epic, and about humanity.

It’s about their dignity.

I could be one of these people. If I had a boy, I’d carry him and jump on a boat and leave everything behind. You want to protect them. But of course, so many people drown in the ocean because there is no safe passage. You see how desperate people are. Those faces were the ones I wanted to talk to and share my feelings with you.

But at the same time, you feel the struggle, and you can’t really help them. Their journey is much longer than you can imagine. It’s a real journey of death. That first generation of people cannot really become a part of society, or a new society. The children, if they are lucky, can get some education, but in most cases and in many locations, you never have a day of school.

They are very brave and capable and determined to establish a new life. They are not interested in somebody giving them mercy or money. They are very proud people with great dignity. They understand life more than most common people. But who is going to have them? Or make it possible for them to restart? That’s a question that’s very hard to answer.

What decisions did you make about where you shot?

We read the news every day. I picked tweets from the news I read [which scroll across the film] that relate to all the issues of the refugees. Every morning, I woke up and followed the news.

You showed the condition of the camps in a granular sense and in great overhead shots, showing us what we generally don’t see in a news report.

We have a very zoom-in lens, and we have iPhone images where we almost touched the subject, but sometimes we needed to pull out to relieve ourselves from this human struggle — to see humans as part of the earth’s movement, or part of nature — to put it into another perspective that overcomes a simple political struggle to see human’s activity. There is the religious argument that human beings, from a certain height, are all the same.

I like the idea one woman says that the people in charge should live in refugee tents. Or when another interviewee says we should send politicians who don’t agree with human rights into space. Your film is political and wants to foment change, but the resources are limited. How do you want people to respond to the film?