Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 269

October 16, 2017

The top 10 most underrated horror films

(Credit: Warner Bros. Pictures/IFC Midnight/IFC Films/Lions Gate Entertainment)

This list of underrated horror films is not necessarily determined by Rotten Tomatoes. Some of these films performed well on the critical aggregator and others did not, but the reality is that Rotten Tomatoes isn’t the end-all of what determines whether a certain movie is highly regarded.

In short, while many of the films listed below are there because they were critically panned, others appear on the list because they were praised but have not been popularly regarded as “classics,” even though they deserve that distinction. Either way, if you’re a fan of horror movies, you should check them out!

1. 1408: In light of how the “It” remake was a box office smash and received glowing critical reviews (in my opinion deservedly so), it’s appropriate to reevaluate “1408.” Although the movie also did well among critics and audiences, it has faded into obscurity in the decade since its theatrical release. This is one of those films in which, while no one single element stands out as superb, all of the parts come together in such a satisfying way that the movie leaves a strong emotional impression on the audience, particularly with John Cusack in the lead role as (what else?) a writer.

2. The Blob (1988 remake): If you’re a fan of Frank Darabont (“The Shawshank Redemption,” “The Mist,” “The Walking Dead”), then you should see this movie. In one of the few remakes that completely surpasses the original in every way, “The Blob” was co-penned by Darabont (along with director Chuck Russell, who horror fans may know from the beloved “A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: The Dream Warriors”) and contains all of his hallmarks: A small town of realistic characters, subplots involving character redemption, a ’50s B-movie vibe. Add state-of-the-art special effects that still hold up today and a breathless atmosphere that makes the film zip right by.

3. Dagon: It’s pretty amazing that more H. P. Lovecraft stories haven’t been adapted into feature films, considering that his stories seem tailor-made for cinema. The gothic visual style, the dread-laden atmosphere, the philosophical determinism and nihilism, the rich mythology filled with grotesque characters and malevolent ancient religions — all of the qualities that make Lovecraft’s stories endure after nearly a century are present in this Stuart Gordon film, one of four Lovecraft adaptations that he has made (including “Re-Animator,” “From Beyond” and a TV episode of “Masters of Horror” called “Dreams in the Witch-House”). It also has the single most graphic and psychologically disturbing death scene I’ve ever witnessed in a horror film, so consider yourself warned.

4. The Final: If you’ve ever been bullied, particularly as a teenager, you’ll strongly empathize with the perspective of the villains in this film. This isn’t to say I condone their actions — quite to the contrary, the movie works precisely because of how we initially sympathize with people who we soon deplore as irredeemable, sadistic monsters — but this is one of the better horror movies with a coherent and meaningful social message. What makes it fall short of greatness, alas, is that the scares themselves seem to be ripped out of Eli Roth’s “Hostel” films instead of being legitimately inspired on their own, although they do contain one clever twist. In the end, though, that doesn’t stop the movie itself from packing quite an emotional wallop.

5. Halloween III: Season of the Witch: There is a bit of a backstory to this movie’s infamous reputation. After the success of the first two “Halloween” films — both of which told the story of fictional serial killer Michael Myers — writers John Carpenter and Debra Hill wanted their third film to be a completely different story, with the goal of turning the “Halloween” franchise into an anthology series. The tale that they came up with was actually pretty interesting, involving an ancient pagan cult, a murder mystery, some child deaths (sorry softies, but I’m tired of kids always getting a pass in horror movies) and clever social commentary about the dangers of consumerism and our culture’s obsequious attitude toward corporations. There are also plot holes galore, so I’m not saying the movie is perfect, but I suspect it was rejected by audiences more because it didn’t contain Michael Myers than because of its own flaws.

6. Jason Goes To Hell: The Final Friday: This is the second “Friday the 13th” film to be self-labeled as the “final” one in the franchise, and like the first “final” movie (part four in the series), it did not conclude the Jason Voorhees story. That said, its unpopularity seems mostly driven by the fact that it discards the mythology established about Jason in the previous films — deformed child drowns at summer camp because of the counselors’ incompetence, then comes back as a slasher killer to avenge his mother (for more on her death, see the first movie) — and instead turns him into a demonic hell-worm who possesses bodies. Yeah, that’s a completely unnecessary twist, but that doesn’t mean the movie doesn’t work well on its own terms. Like “Halloween III: Season of the Witch,” this movie seems to have a bad reputation less because of its failures as a horror film and more because it deviated from a trusted formula. Analyzed on its own merits, the movie is still scary, contains likable characters and has some impressive gore effects.

7. Planet Terror: I still remember seeing this Robert Rodriguez gem during its first theatrical release in 2007, back when it was part of a “Grindhouse” double-feature with Quentin Tarantino’s “Death Proof.” While the Tarantino movie was a tribute to slasher and muscle car movies of the 1970s, “Planet Terror” was an uber-graphic zombie flick that paid homage to the gory exploitation fare from the 1970s and 1980s. It also contains a series of memorable performances from an all-star cast including Rose McGowan, Freddy Rodriguez, Michael Biehn, Josh Brolin and Bruce Willis, as well as creative gore effects and Rodriguez’s characteristically sharp dialogue. Watch while gnoshing on a pile of barbecue ribs if you can.

8. Stung: You could almost mistake “Stung” for a Sam Raimi or Robert Rodriguez film, assuming they decided to apply their over-the-top gore aesthetic to a story about killer mutant wasps. How can a gorehound not enjoy a movie in which giant wasps literally burst from the bodies of their hosts, sometimes still dripping half-skull here or there afterward? It also manages to avoid one of the most common pitfalls that often befalls creature features — namely, being chock-full of annoying and/or forgettable characters — and even has some slower moments that work quite well on a dramatic level.

9. Trick r’ Treat: This should be for Halloween what a film like “1776” is for the 4th of July. A series of stories told in a non-linear format reminiscent of “Pulp Fiction,” “Trick r’ Treat” is all about the spirit of Halloween. Even the main villain, Sam, is motivated by a desire to make sure that all of the inhabitants of a random American town abide by the rules of Halloween tradition. It’s pretty difficult to go into any further detail about the plot of “Trick r’ Treat” without spoiling major reveals, so suffice to say that if you see one movie on this list, it should be that one.

10. Would You Rather?: This isn’t just a horror movie with social commentary; the primary villain of the film — more so than the sadistic family that forces people to compete in a life-or-death game of Would You Rather? — is the system of income inequality that allows them to indulge in their cruel tradition. “Would You Rather?” also deserves points for being able to keep audiences wincing and on the edge of their seats despite showing very little blood or gore. The horror is instead derived from the psychological tension that comes from imagining one’s self being forced to make the same ethical and existential choices forced on the characters. In that way, “Would You Rather?” feels like a throwback to “The Twilight Zone” or “Alfred Hitchcock Presents.”

Trump’s most absurd comments from today’s press conference

(Credit: AP/Evan Vucci)

Rhetorically speaking, today’s press conference was textbook Trump: He bashed Hillary Clinton for her election loss, criticized former President Obama, praised himself, and went to great lengths to assure everyone of his “outstanding” relationship with Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell. Interestingly, Trump also stumbled over some of his responses and was called out for his lies and distortions.

When asked about American soldiers’ deaths in Niger, Trump touted his supposed morals by bragging that he made phone calls to the families of the fallen, unlike Obama and other previous presidents — in the process, making these soldiers’ deaths about himself.

“I will at some point during the period of time call the parents and the families because I have done that traditionally,” Trump said. “It’s a very difficult thing, now it gets to a point where you make four or five of them in one day, it’s a very, very tough day, for me that’s by far the toughest.”

He then went on to (falsely) accuse Obama of not doing the same thing: “So the traditional way, if you look at President Obama and other presidents, most of them didn’t make calls, a lot of them didn’t make calls. I like to call when it’s appropriate when I think I’m able to do it.”

Later in the press conference, a reporter called him out on his claim that President Obama didn’t call the families of fallen soldiers. Trump then floundered: “I don’t know if he did. I was told that he didn’t often and a lot of presidents don’t, they write letters.” Then he praised himself again: “I do a combination of both, sometimes it’s a very difficult thing to do. President Obama I think probably did sometimes and maybe sometimes he didn’t. I don’t know, thats what I was told.”

And since the news has recently reported tensions between Trump and his colleagues, he decided to negate that news by bragging about his amount of friends. “I have a fantastic relationship with the people in the Senate and with the people in Congress. I’m friends with most of them, I can say, and I don’t think anybody can have much of a higher percentage.” But when pressed about the tension between him and the Democrats of the Senate, especially when it comes to a solution for DACA, Trump responded, “Well, I hope to have a relationship, but if we don’t — we don’t.”

He was also asked about his position on Roy Moore, the newly elected Alabama Senator who said homosexuality should be illegal and that Muslims should not be able to serve in Congress. Trump dodged the question, saying that the “people of Alabama, who I like very much, and they like me very much, they like Roy.” He also mentioned that he will be meeting with Senator Moore to “talk about a lot of different things.”

When asked about the sexual assault allegations that were made against him, Trump dismissed it as “totally fake news.”

He also responded to a question about the Russia investigation by saying that it’s “just an excuse for the Democrats losing the election” even though they “have a big advantage in the electoral college.”

He continued to bash Clinton when asked about her response to the NFL protests, in which she said the protests were not disrespectful to the country.

Unsurprisingly, he concluded the press conference by saying that NFL players who kneel should be suspended and that Clinton’s “statement in itself is very disrespectful to our country.”

Trump sticks by Steve Bannon, defends attacks against GOP

Donald Trump; Stephen Bannon (Credit: AP/Matt Rourke/Reuters/Carlo Allegri)

On Monday, President Donald Trump got a rare chance to play a conciliatory role as he defended his former top strategist Steve Bannon’s “war” against Republican elected officials whom he sees as insufficiently deferential to the president.

“Steve is very committed, he’s a friend of mine and he’s committed to getting things passed,” Trump told reporters at a briefing held in conjunction with a presidential cabinet meeting. “I know how he feels.”

Trump added later that while he has a “fantastic relationship” with Republicans in the Senate, “there are some Republicans, frankly, that should be ashamed of themselves.”

The president lashed out at Senate Republicans for failing to pass important legislation. “I’m not going to blame myself, I’ll be honest. They are not getting the job done. We’ve had health care approved and then you had a surprise vote by John McCain. We’ve had other things happen and they’re not getting the job done,” Trump told reporters.

Since being ousted from the White House, Bannon has returned to his former post as chairman of Breitbart News, the conservative website which he turned into a platform for extremist Republicans and white nationalists over the last several years. In his current effort against Republican elites, Bannon is attempting to get rid of the Senate filibuster and to dislodge the GOP’s Senate leader, Mitch McConnell.

On Sunday, Bannon told attendees at the Values Voters Summit, an annual gathering put on by the Christian supremacist group Family Research Council Action, that he was also opposing many Republican elected officials who have not feuded with the president because they refuse to stand up for him against critics, including Tennessee Sen. Bob Corker, who recently referred to the White House as an “adult daycare center.”

In his speech, Bannon implied that he would support challengers to Wyoming Sen. John Barrasso, Utah Sen. Orrin Hatch, Nebraska Sen. Deb Fischer, and Nevada Sen. Dean Heller.

“There’s time for mea culpa,” Bannon offered. “You can come to a stick [microphone] and condemn Sen. Corker.”

Should any of the above-named senators agree to defend Trump in public and to vote against McConnell and for getting rid of the filibuster, the Breitbart chairman said that maybe the people challenging them “may reconsider.”

“Until that time, they’re coming for you,” Bannon said over the weekend.

Trump seemed to approve of the idea on Monday.

“I can understand where Steve Bannon is coming from,” he said. “I can understand where a lot of people are coming from. Because I’m not happy about it and a lot of people aren’t happy about it.”

Trump then offered a rhetorical wink and nod: “Steve is doing what Steve thinks is the right thing.”

American-born jazz artist denied entry for brush with law 50 years ago

Alvin Queen (Credit: Wikimedia)

While President Donald Trump has faced public backlash and judicial pushback against his draconian immigration policies, it has only made him redouble. In order to bypass his proposed slate of travel restrictions — which many categorized as a religious ban — Trump ramped up the order to include countries like Venezuela, Chad and North Korea, which are not majority Muslim.

While many point to former President Barack Obama as the forerunner in ushering in harsh immigration and visa policies that have proved devastating to individuals and families, Trump has tried to top him (per usual). The effects of Trump tightening the reins on visas and immigration is being felt widely. While many policies remain unchanged, the way they are being executed and prosecuted is changing. Immigrants have more to fear on a daily basis, and those attempting to enter the United States through perfectly legal means find more barriers in their way.

Much of this has been done through orders and memos. Even more of it has been done through the president signaling his intentions to both agencies and individual officers who now seem willing and enthusiastic to forward his uncompromising, unmerciful vision of a virtual wall around our country, one that blocks out even innocuous and unthreatening guests.

Take the recent case of one jazz great, American-born drummer Alvin Queen. According to a press release, U.S. Homeland Security informed Queen that he will not be able to enter the country to perform at a concert in Washington, D.C. next month because of a brush with the law over 50 years ago. Queen was a legal minor at the time.

Queen, who held dual-citizenship until 2016, was informed by the department that he needs to apply for a waiver from Homeland Security. It is a process that could take months, which means he will not be able to participate in the “Jazz Meets France” concert in mid-November.

“Sadly, this doesn’t surprise me one bit,” Queen, 67, said in the press release. “I’ve spent months preparing for this concert. Dozens of others are also implicated in its planning. Funny thing, I gave up my U.S. passport to make life simpler at tax time. I never dreamed I would one day be denied entry, and with such ridiculous reasoning. I am frankly disgusted to be disrespected in this way, after a half century devoted to music.”

Queen regularly worked with the American government, as a cultural ambassador for the State Department, throughout numerous international tours and as a performer at the American International Jazz Day in Paris.

He says, his run-ins with the law in the late ’60s included a DWI charge and a minor drug offense. Both were brought to trial; both resulted in not-guilty verdicts. According to Queen, it was the odd fact that his fingerprints matched a 1967 FBI file that prompted the State Department to deny him entry.

If the alert and the ruling were a simple, innocent case of bureaucratic cross wiring, it would be something easily resolved. If it were something more malicious, it would be called out as against best practices. Things such as these, however, are not easily rectified in the age of Trump.

Queen, a black man playing black music, takes it even a step further. “I feel this is more about racial profiling than anything,” Queen said. “It’s all about trying to control everyone. I am not a criminal and in fact never was. When I became a Swiss citizen, I ‘became a criminal’ again in the eyes of U.S. law enforcement.” There’s no evidence that this is indeed the case, but its almost impossible to argue against the spirit of this in good faith.

He wonders, “If I was undesirable fifty years ago, why have I been issued a fresh passport every ten years for the past six decades?” Indeed, nothing about Queen has changed in that time. Nothing has changed about his history. It is only this country and its government that have shifted. The result is that a man who is in every cultural way a full American cannot get into the country. This is America eating itself out of spite.

Queen knows it. “If someone wants to apologize to me and make this right, fine. But I’m not holding my breath,” he says. “In the meantime, I’ll bring my music, this American art form, to every other country in the world. I know they like me in Canada. I’ll start there.”

The empire comes home, and every city is a battlefield

(Credit: Reuters/Jessica Rinaldi)

“This… thing, [the War on Drugs] this ain’t police work… I mean, you call something a war and pretty soon everybody gonna be running around acting like warriors… running around on a damn crusade, storming corners, slapping on cuffs, racking up body counts… pretty soon, damn near everybody on every corner is your f**king enemy. And soon the neighborhood that you’re supposed to be policing, that’s just occupied territory.”— Major “Bunny” Colvin, season three of HBO’s The Wire

I can remember both so well.

2006: my first raid in South Baghdad. 2014: watching on YouTube as a New York police officer asphyxiated — murdered — Eric Garner for allegedly selling loose cigarettes on a Staten Island street corner not five miles from my old apartment. Both events shocked the conscience.

It was 11 years ago next month: my first patrol of the war and we were still learning the ropes from the army unit we were replacing. Unit swaps are tricky, dangerous times. In Army lexicon, they’re known as “right-seat-left-seat rides.” Picture a car. When you’re learning to drive, you first sit in the passenger seat and observe. Only then do you occupy the driver’s seat. That was Iraq, as units like ours rotated in and out via an annual revolving door of sorts. Officers from incoming units like mine were forced to learn the terrain, identify the key powerbrokers in our assigned area, and sort out the most effective tactics in the two weeks before the experienced officers departed. It was a stressful time.

Those transition weeks consisted of daily patrols led by the officers of the departing unit. My first foray off the FOB (forward operating base) was a night patrol. The platoon I’d tagged along with was going to the house of a suspected Shiite militia leader. (Back then, we were fighting both Shiite rebels of the Mahdi Army and Sunni insurgents.) We drove to the outskirts of Baghdad, surrounded a farmhouse, and knocked on the door. An old woman let us in and a few soldiers quickly fanned out to search every room. Only women — presumably the suspect’s mother and sisters — were home. Through a translator, my counterpart, the other lieutenant, loudly asked the old woman where her son was hiding. Where could we find him? Had he visited the house recently? Predictably, she claimed to be clueless. After the soldiers vigorously searched (“tossed”) a few rooms and found nothing out of the norm, we prepared to leave. At that point, the lieutenant warned the woman that we’d be back — just as had happened several times before — until she turned in her own son.

I returned to the FOB with an uneasy feeling. I couldn’t understand what it was that we had just accomplished. How did hassling these women, storming into their home after dark and making threats, contribute to defeating the Mahdi Army or earning the loyalty and trust of Iraqi civilians? I was, of course, brand new to the war, but the incident felt totally counterproductive. Let’s assume the woman’s son was Mahdi Army to the core. So what? Without long-term surveillance or reliable intelligence placing him at the house, entering the premises that way and making threats could only solidify whatever aversion the family already had to the U.S. Army. And what if we had gotten it wrong? What if he was innocent and we’d potentially just helped create a whole new family of insurgents?

Though it wasn’t a thought that crossed my mind for years, those women must have felt like many African-American families living under persistent police pressure in parts of New York, Baltimore, Chicago, or elsewhere in this country. Perhaps that sounds outlandish to more affluent whites, but it’s clear enough that some impoverished communities of color in this country do indeed see the police as their enemy. For most military officers, it was similarly unthinkable that many embattled Iraqis could see all American military personnel in a negative light. But from that first raid on, I knew one thing for sure: we were going to have to adjust our perceptions — and fast. Not, of course, that we did.

Years passed. I came home, stayed in the Army, had a kid, divorced, moved a few more times, remarried, had more kids— my Giants even won two Super Bowls. Suddenly everyone had an iPhone, was on Facebook, or tweeting, or texting rather than calling. Somehow in those blurred years, Iraq-style police brutality and violence — especially against poor blacks — gradually became front-page news. One case, one shaky YouTube video followed another: Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Philando Castile, and Freddie Gray, just to start a long list. So many of the clips reminded me of enemy propaganda videos from Baghdad or helmet-cam shots recorded by our troopers in combat, except that they came from New York, or Chicago, or San Francisco.

Brutal Connections

As in Baghdad, so in Baltimore. It’s connected, you see. Scholars, pundits, politicians, most of us in fact like our worlds to remain discretely and comfortably separated. That’s why so few articles, reports, or op-ed columns even think to link police violence at home to our imperial pursuits abroad or the militarization of the policing of urban America to our wars across the Greater Middle East and Africa. I mean, how many profiles of the Black Lives Matter movement even mention America’s 16-year war on terror across huge swaths of the planet? Conversely, can you remember a foreign policy piece that cited Ferguson? I doubt it.

Nonetheless, take a moment to consider the ways in which counterinsurgency abroad and urban policing at home might, in these years, have come to resemble each other and might actually be connected phenomena:

*The degradations involved: So often, both counterinsurgency and urban policing involve countless routine humiliations of a mostly innocent populace. No matter how we’ve cloaked the terms — “partnering,” “advising,” “assisting,” and so on — the American military has acted like an occupier of Iraq and Afghanistan in these years. Those thousands of ubiquitous post-invasion U.S. Army foot and vehicle patrols in both countries tended to highlight the lack of sovereignty of their peoples. Similarly, as long ago as 1966, author James Baldwin recognized that New York City’s ghettoes resembled, in his phrase, “occupied territory.” In that regard, matters have only worsened since. Just ask the black community in Baltimore or for that matter Ferguson, Missouri. It’s hard to deny America’s police are becoming progressively more defiant; just last month St. Louis cops taunted protestors by chanting “whose streets? Our streets,” at a gathering crowd. Pardon me, but since when has it been okay for police to rule America’s streets? Aren’t they there to protect and serve us? Something tells me the exceedingly libertarian Founding Fathers would be appalled by such arrogance.

*The racial and ethnic stereotyping. In Baghdad, many U.S. troops called the locals hajis, ragheads, or worse still, sandniggers. There should be no surprise in that. The frustrations involved in occupation duty and the fear of death inherent in counterinsurgency campaigns lead soldiers to stereotype, and sometimes even hate, the populations they’re (doctrinally) supposed to protect. Ordinary Iraqis or Afghans became the enemy, an “other,” worthy only of racial pejoratives and (sometimes) petty cruelties. Sound familiar? Listen to the private conversations of America’s exasperated urban police, or the occasionally public insults they throw at the population they’re paid to “protect.” I, for one, can’t forget the video of an infuriated white officer taunting Ferguson protestors: “Bring it on, you f**king animals!” Or how about a white Staten Island cop caught on the phone bragging to his girlfriend about how he’d framed a young black man or, in his words, “fried another nigger.” Dehumanization of the enemy, either at home or abroad, is as old as empire itself.

*The searches: Searches, searches, and yet more searches. Back in the day in Iraq — I’m speaking of 2006 and 2007 — we didn’t exactly need a search warrant to look anywhere we pleased. The Iraqi courts, police, and judicial system were then barely operational. We searched houses, shacks, apartments, and high rises for weapons, explosives, or other “contraband.” No family — guilty or innocent (and they were nearly all innocent) — was safe from the small, daily indignities of a military search. Back here in the U.S., a similar phenomenon rules, as it has since the “war on drugs” era of the 1980s. It’s now routine for police SWAT teams to execute rubber-stamped or “no knock” search warrants on suspected drug dealers’ homes (often only for marijuana stashes) with an aggressiveness most soldiers from our distant wars would applaud. Then there are the millions of random, warrantless, body searches on America’s urban, often minority-laden streets. Take New York, for example, where a discriminatory regime of “stop-and-frisk” tactics terrorized blacks and Hispanics for decades. Millions of (mostly) minority youths were halted and searched by New York police officers who had to citeonly such opaque explanations as “furtive movements,” or “fits relevant description” — hardly explicit probable cause — to execute such daily indignities. As numerous studies have shown (and a judicial ruling found), such “stop-and-frisk” procedures were discriminatory and likely unconstitutional.

As in my experience in Iraq, so here on the streets of so many urban neighborhoods of color, anyone, guilty or innocent (mainly innocent) was the target of such operations. And the connections between war abroad and policing at home run ever deeper. Consider that in Springfield, Massachusetts, police anti-gang units learned and applied literal military counterinsurgency doctrine on that city’s streets. In post-9/11 New York City, meanwhile, the NYPD Intelligence Unit practiced religious profiling and implemented military-style surveillance to spy on its Muslim residents. Even America’s stalwart Israeli allies — no strangers to domestic counterinsurgency — have gotten in on the game. That country’s Security Forces have been training American cops, despite their long record of documented human rights abuses. How’s that for coalition warfare and bilateral cooperation?

*The equipment, the tools of the trade: Who hasn’t noticed in recent years that, thanks in part to a Pentagon program selling weaponry and equipment right off America’s battlefields, the police on our streets look ever less like kindly beat cops and ever more like Robocop or the heavily armed and protected troops of our distant wars? Think of the sheer firepower and armor on the streets of Ferguson in those photos that shocked and discomforted so many Americans. Or how about the aftermath of the tragic Boston Marathon Bombing? Watertown, Massachusetts, surely resembled U.S. Army-occupied Baghdad or Kabul at the height of their respective troop “surges,” as the area was locked down under curfew during the search for the bombing suspects.

Here, at least, the connection is undeniable. The military has sold hundreds of millions of dollars in excess weapons and equipment — armored vehicles, rifles, camouflage uniforms, and even drones — to local police departments, resulting in a revolving door of self-perpetuating urban militarism. Does Walla Walla, Washington, really need the very Mine Resistant Ambush-Protected (MRAP) trucks I drove around Kandahar, Afghanistan? And in case you were worried about the ability of Madison, Indiana (pop: 12,000), to fight off rocket propelled grenades thanks to those spiffy new MRAPs, fear not, President Trump recently overturned Obama-era restrictions on advanced technology transfers to local police. Let me just add, from my own experiences in Baghdad and Kandahar, that it has to be a losing proposition to try to be a friendly beat cop and do community policing from inside an armored vehicle. Even soldiers are taught not to perform counterinsurgency that way (though we ended up doing so all the time).

*Torture: The use of torture has rarely — except for several years at the CIA — been official policy in these years, but it happened anyway. (See Abu Ghraib, of course.) It often started small as soldier — or police — frustration built and the usual minor torments of the locals morphed into outright abuse. The same process seems underway here in the U.S. as well, which was why, as a 34-year old New Yorker, when I first saw the photos at Abu Ghraib, I flashed back to the way, in 1997, the police sodomized Abner Louima, a Haitian immigrant, in my own hometown. Younger folks might consider the far more recent case in Baltimore of Freddie Gray, brutally and undeservedly handcuffed, his pleas ignored, and then driven in the back of a police van to his death. Furthermore, we now know about two decades worth of systematic torture of more than 100 black men by the Chicago police in order to solicit (often false) confessions.

Unwinnable Wars: At Home and Abroad

For nearly five decades, Americans have been mesmerized by the government’s declarations of “war” on crime, drugs, and — more recently — terror. In the name of these perpetual struggles, apathetic citizens have acquiesced in countless assaults on their liberties. Think warrantless wiretapping, the Patriot Act, and the use of a drone to execute an (admittedly deplorable) American citizen without due process. The First, Fourth, and Fifth Amendments — who needs them anyway? None of these onslaughts against the supposedly sacred Bill of Rights have ended terror attacks, prevented a raging opioid epidemic, staunched Chicago’s record murder rate, or thwarted America’s ubiquitous mass shootings, of which the Las Vegas tragedy is only the latest and most horrific example. The wars on drugs, crime, and terror — they’re all unwinnable and tear at the core of American society. In our apathy, we are all complicit.

Like so much else in our contemporary politics, Americans divide, like clockwork, into opposing camps over police brutality, foreign wars, and America’s original sin: racism. All too often in these debates, arguments aren’t rational but emotional as people feel their way to intractable opinions. It’s become a cultural matter, transcending traditional policy debates. Want to start a sure argument with your dad? Bring up police brutality. I promise you it’s foolproof.

So here’s a final link between our endless war on terror and rising militarization on what is no longer called “the home front”: there’s a striking overlap between those who instinctively give the increasingly militarized police of that homeland the benefit of the doubt and those who viscerally support our wars across the Greater Middle East and Africa.

It may be something of a cliché that distant wars have a way of coming home, but that doesn’t make it any less true. Policing today is being Baghdadified in the United States. Over the last 40 years, as Washington struggled to maintain its global military influence, the nation’s domestic police have progressively shifted to military-style patrol, search, and surveillance tactics, while measuring success through statistical models familiar to any Pentagon staff officer.

Please understand this: for me when it comes to the police, it’s nothing personal. A couple of my uncles were New York City cops. Nearly half my family has served or still serves in the New York Fire Department. I’m from blue-collar, civil service stock. Good guys, all. But experience tells me that they aren’t likely to see the connections I’m making between what’s happening here and what’s been happening in our distant war zones or agree with my conclusions about them. In a similar fashion, few of my peers in the military officer corps are likely to agree, or even recognize, the parallels I’ve drawn.

Of course, these days when you talk about the military and the police, you’re often talking about the very same people, since veterans from our wars are now making their way into police forces across the country, especially the highly militarized SWAT teams proliferating nationwide that use the sorts of smash-and-search tactics perfected abroad in recent years. While less than 6% of Americans are vets, some 19% of law-enforcement personnel have servedin the U.S. military. In many ways it’s a natural fit, as former soldiers seamlessly slide into police life and pick up the very weaponry they once used in Afghanistan, Iraq, or elsewhere.

The widespread perpetuation of uneven policing and criminal (in)justice can be empirically shown. Consider the numerous critical Justice Department investigations of major American cities. But what concerns me in all of this is a simple enough question: What happens to the republic when the militarism that is part and parcel of our now more or less permanent state of war abroad takes over ever more of the prevailing culture of policing at home?

And here’s the inconvenient truth: despite numerous instances of brutality and murder perpetrated by the U.S. military personnel overseas — think Haditha (the infamous retaliatory massacre of Iraqi civilians by U.S. Marines), Panjwai (where a U.S. Army Sergeant left his base and methodically executed nearby Afghan villagers), and of course Abu Ghraib — in my experience, our army is often stricter about interactions with foreign civilians than many local American police forces are when it comes to communities of color. After all, if one of my men strangled an Iraqi to death for breaking a minor civil law (as happened to Eric Garner), you can bet that the soldier, his sergeant, and I would have been disciplined, even if, as is so often the case, such accountability never reached the senior-officer level.

Ultimately, the irony is this: poor Eric Garner — at least if he had run into my platoon — would have been safer in Baghdad than on that street corner in New York. Either way, he and so many others should perhaps count as domestic casualties of my generation’s forever war.

What’s global is local. And vice versa. American society is embracing its inner empire. Eventually, its long reach may come for us all.

We know terrifyingly little about how our bodies respond to pollutants, but that’s changing

(Credit: Brian Graitwicke/Massive)

Bad news: unless you live in a bubble, you are full of contaminants. Somewhat more reassuring news: every other living creature on Earth seems to share this condition with you.

Bad news: unless you live in a bubble, you are full of contaminants. Somewhat more reassuring news: every other living creature on Earth seems to share this condition with you.

Both terrifying and unifying, widespread contamination in humans and wildlife arises due to the slow and constant accumulation of chemicals in living creatures from their surrounding environment and diet, in a pathway known as bioaccumulation. Virtually everything you or any other living creature do contributes to this buildup: consumer products, food, textiles, building materials, household dust, drinking water, surface water, deep water, soil, and even air have all been found to contain multitudes of human-created chemicals. A recent study has even found microplastic fibers in municipal drinking water supplies across the country and globe.

Despite our chemical-laden lifestyles, we have almost no comprehensive idea how the accumulation of these compounds impacts living creatures, particularly wildlife, beyond acute effects. Yes, some chemicals have been shown to cause cancer or seriously mess up hormone production in humans or wildlife. But most chemicals in the environment primarily act by changing or weakening organisms’ overall health in ways that don’t outright kill them.

This poor understanding stems from the fact that it is difficult to pin down definitive or causal relationships between pollution and its consequences when so many other factors could be at play in complex living systems. When a human gets cancer or a bird is having trouble laying eggs, it is nearly impossible to parse out how contaminants contributed in conjunction with variables like age, genetic inclination, nutritional state, and other environmental stressors.

Yet the challenging nature of the problem hasn’t dissuaded researchers from broaching it, and we are slowly starting to better understand how contaminants impact living beings. One recent study in particular helps highlight just how far we’ve come in understanding the sub-lethal metabolic effects contaminants have on wildlife.

Adapting to pollution, but at what cost?

The international team, led by Nishad Jayasundara of the University of Maine at Orono, focused on the mummichog, a common and well-studied fish that primarily lives in estuaries, marshes, and coastal environments. Mummichogs have long demonstrated a unique ability to adapt to polluted environments, with various lab and field research documenting genetic and physical adaptions to a variety of contaminants like heavy metals, pesticides, and other organic chemicals.

The team built upon this prior research by taking advantage of a natural experiment ongoing in the Elizabeth River along the coast of Virginia. Mummichog populations in the Elizabeth inhabit differently contaminated sub-environments within the larger river system. The team collected live fish from sites known to contain high, medium, and low levels of polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), a toxic and carcinogenic pollutant. The fish were then allowed to acclimate to environmental conditions in captivity before undergoing comprehensive evaluation.

After the acclimation period, the researchers first focused on genetics, and used previously existing work to identify genes that are different in contaminated and uncontaminated fish. They specifically looked at genes related to metabolism. From there, it was time for fish “Olympics.” The researchers made the fish swim until tired while measuring their oxygen consumption, metabolic rate, swimming ability, and tolerance to increased temperatures. The results of these measurements were fed into a statistical model to extrapolate how differential fish physical fitness impacts how the fish moves and responds within its environment.

So, this is a fish treadmill.

Using this multi-tiered strategy, the researchers described how pollution had cumulative effects at the levels of DNA, animal, and ecosystem. They found something surprising. Mummichogs deal with PAH exposure by changing their gene makeup.

Let that sink in a minute: fish DNA actually changes to cope with polluted environments. This alters metabolism and energy allocation, thereby compromising the fish’s ability to deal with other stressors in their environment. In this study, fish from polluted environments were less able to cope with increased temperatures; this has huge implications in a warming world where climate change is at work to increase water temperatures around the globe.

This is also troubling because mummichogs are considered extremely habitat-flexible, dealing with wide ranges in temperature and salinity. If any creature should be able to cope with thermal stress, it’s these guys. Additionally, the modeling work suggested the compounded effects of altered genes, metabolism, and coping ability translates to fish being less capable of finding and traveling to an optimum environment, meaning contaminant exposure has the potential to alter the very way fish interact with the surrounding environment.

How does pollution effect the rest of us?

But what about all the wildlife that’s bigger than the size of a finger? How do contaminants sublethally impact cats, pigs, sharks, weasels, deer, or seabirds? Unfortunately, when larger creatures are factored into the conversation, we are reminded that we understand close to zilch when it comes to sublethal impacts of contaminants in wildlife.

A recent study focusing on Arctic seabirds embodies such existing gaps and highlights how tough it is to figure out how contaminants are undermining wildlife processes and function. Few studies have tackled contaminant impacts on metabolism in birds, thanks to how hard it is to compare features of very different species, as well as the fact that studying live creatures in the wild is much harder than analyzing samples. Those that have forged ahead looking at bird hormone production and metabolism have seen conflicting results.

So there is scant consensus regarding how birds metabolically respond to contaminant burdens. An international team led by biologist Pierre Blévin, of the Centre d’Etudes Biologiques de Chizé in France, recognized this uncertainty and implemented a study in an effort to better understand how contaminants are related to energy use in live birds. The team captured black-legged kittiwakes, a type of Arctic seabird, during their chick rearing season on Svalbard in Norway and took blood samples from captured birds for contaminant and hormone analysis. The birds were then rushed back to the lab via boat to take respirometry measurements. Respirometry essentially measures carbon dioxide respiration and oxygen consumption over time, allowing calculation of metabolic rate.

Unfortunately, no clear picture emerged. The researchers found that different groups of contaminants were associated with variable metabolic rate and hormone levels. Increased concentrations of banned chlorine-based compounds, like pesticides or PCBs, were associated with decreased metabolic rate and hormone levels, while currently used perfluorinated chemicals, used as water repellants, were associated with an increased metabolic rate only in females.

These inconsistent results provide more questions than answers in terms of parsing out the greater impact of contaminants on birds. If organochlorine and perfluorinated compounds have opposite effects on metabolism, does this mean they cancel each other out? What is the net effect on bird energy use and what does this mean for bird migration? These birds migrate thousands of miles; do contaminant metabolic artifacts impact these feats?

It’s hard to say: wild animals that live longer lives come with a history full on unknown events that may easily confound snapshots of metabolic rate or contaminant signature obtained within a study. In terms of methodology, transporting large wild animals alive for metabolism measurements is extremely time-consuming, expensive, and location-dependent, not to mention a permitting nightmare depending on the study location. This contrasts starkly with research solely measuring contaminant body burdens, which just uses tissue from dead animals. This is exponentially more straightforward, and cheaper, hence the abundance of reports describing contaminant levels in animals with little indication of how found chemicals are impacting the animal or its day to day function.

Still, these sorts of studies should not be avoided, but rather viewed as a challenge. The need to comprehend contaminant impacts in humans and wildlife only continues to grow, as thousands of chemicals are introduced each year to replace banned compounds or for novel applications, adding to the inundating chemical soup surrounding us.

* * *

Peer commentary

We asked other consortium members to respond with some commentary to this article. In a very small way, this is how peer-review works in scientific journals. We wanted to give you a taste of what scientific discussion looks like! If you want to know more, feel free to contact the scientists directly via Twitter.

Kelsey Lucas: Contamination is a serious problem in all sorts of environments, as captured in the mummichog and bird studies described here. We should also remember that these problems can exist over multiple scales: in time based on the rate of spreading or breakdown of chemicals, in size based on who takes in contaminants how these are passed through a food chain, and in space, like how plastics in the ocean surface are being concentrated and passed to the seafloor.

The confusing results from the Arctic birds provide a great example of the difficulties in interpreting what exactly contaminants are doing, but answering the questions that emerged will likewise be a challenge. The ethics of giving animals contaminants is dicey at best, making it difficult to tease apart the individual outcomes of multiple contaminants working in tandem. The work presented here is fundamental to our understanding of these processes, and I hope that we’ll be able to find acceptable ways to build upon it – and ultimately, find ways to mitigate the damage.

Kevin Pels: It would be interesting to know, in a species-specific fashion (not practical, I know), what contaminants have longer in vivo half-lives. I’d guess the polychloro/fluoro compounds, which are relatively inert, stick around in circulation in many species, but the endocrine effects would vary. Birds present a more complicated study as they could sequester contaminants on their feathers/skin and ingest or absorb them. Additionally, they represent a more direct route for contaminants into the human food chain than one might think – gull eggs are considered a delicacy in the UK. If short-sighted people don’t care about ecology, maybe their interest is piqued when it circles back to human health.

Do people like government “nudges”? Study says yes

(Credit: CSA-Plastock via iStock/Salon)

On Oct. 9, Richard Thaler of the University of Chicago won the Nobel Prize for his extraordinary, world-transforming work in behavioral economics. In its press release, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences emphasized that Thaler demonstrated how nudging – or influencing people while fully maintaining freedom of choice – “may help people exercise better self-control when saving for a pension, as well in other contexts.”

In terms of Thaler’s work on what human beings are actually like, that’s the tip of the iceberg – but it’s a good place to start.

In 2008, Thaler and I wrote “Nudge,” emphasizing the massive potential of seemingly small interventions that steer people in particular directions but that also allow them to go their own way. That’s how a GPS nudges. Other common nudges include a calorie label, a reminder that you have a doctor’s appointment next week, a warning that a product contains peanuts and so-called default rules, such as automatically shifting a small percentage of your salary to a pension program unless you opt out.

Some skeptics have raised concerns that nudging can be akin to manipulation. My research shows most people disagree – and welcome nudges that help them live better lives.

The FDA uses cigarette warnings to nudge behavior.

AP Photo/Evan Vucci

A world of nudges

In numerous nations, public officials have been drawn to nudges, especially in recent years.

In the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, the Netherlands and many other nations, officials have used nudges to implement public policies. Examples include disclosing information about the ingredients of food, providing fuel economy labels on cars, offering warnings about cigarettes and distracted driving, automatically enrolling people in pension plans, and requiring disclosures about mortgage payments and credit card usage. With an emphasis on poverty and development, the World Bank devoted its entire 2015 report to behaviorally informed tools, with a particular focus on nudging. Examples cited include setting defaults that encourage saving and texting reminders to help people to pay bills on time.

The reason for the mounting interest is clear: If governments can achieve policy goals with tools that do not impose high costs – while preserving freedom of choice – they will take those tools seriously.

But governments also care what citizens actually think. Do they approve of nudges?

My research, analyzed in my book, “The Ethics of Influence,” supports a single and perhaps surprising conclusion: In many nations, strong majorities favor nudges – certainly of the kind that have been seriously proposed, or acted on, by actual institutions in recent years. My surveys show that people like mandatory calorie labels. They favor graphic health warnings for cigarettes. They approve of automatic enrollment in savings plans. In general, they like nudges that promote healthy and safety, and have no ethical complaints.

In the United States and Europe, Professor Lucia Reisch of Copenhagen Business School and I have found that this enthusiasm usually extends across standard partisan lines. In the United States, it unifies Democrats, Republicans and independents. This is an important finding, because it suggests that most people do not share the concern that nudges, as such, should be taken as manipulative or as an objectionable interference with autonomy. By contrast, a lot of people object to mandates and bans, apparently on the ground that they limit freedom.

When nudging goes wrong

At the same time, most people reject nudges that are taken to have illegitimate goals. Nudges that favor a particular religion or political party will meet with widespread disapproval, even among people of that very religion or party.

This simple principle justifies a prediction: Whenever people think that the motivations of public officials are illicit, they will disapprove of the nudge. To be sure, that prediction might not seem terribly surprising, but it suggests an important point, which is that people will not oppose nudges as such. Everything will turn on what they are nudging people toward.

Most people also oppose nudges that they see as inconsistent with the interests or values of the people whom they affect.

If public officials nudge people to give money to a cause they dislike, citizens will disapprove. More surprisingly, they will also dislike it if officials adopt a default rule by which citizens automatically give their money to a good charity. Apparently people think that if they are going to give to charity or lose some of their money, it had better be a result of a conscious choice. By contrast, most people favor automatic voter registration and automatic enrollment in pension plans and green energy, apparently because citizens think that those nudges are in most people’s interests.

Why we need more nudging

Simple as they are, these principles capture most people’s ethical judgments in many nations (including the United States and Europe): Nudges are acceptable, even wonderful, if they will promote people’s health, safety or welfare. They are unacceptable if they have illegitimate goals or if they would compromise the interests or values of the people they affect.

It is true, of course, that surveys cannot settle the ethical issues. We need to investigate the ethical issues in some depth. As “The Ethics of Influence” shows, that investigation requires us to investigate some big philosophical issues, involving human welfare, human autonomy and human dignity.

One of my conclusions is that if we really care about welfare, autonomy and dignity, nudging is often required on ethical grounds. We need a lot more of it. The lives we save may be our own.

One of my conclusions is that if we really care about welfare, autonomy and dignity, nudging is often required on ethical grounds. We need a lot more of it. The lives we save may be our own.

Cass Sunstein, University Professor, Harvard University.

October 15, 2017

In most schools, gifted students with learning disabilities are left behind. Not here

(Credit: Jackie Molloy/Narratively)

A group of seven and eight-year-old kids cluster around tables, solving math problems designed for students five grades ahead of them. They’re asked to add and subtract different amounts of minutes from a specific time, and are timed on how fast they can solve the problems. “So, if it’s 10:15 a.m. and you move 450 minutes into the future, what time is it? Then move 105 minutes back. What time is it now? Go!”

A tiny whiz kid tackles these problems with ease, which thrills him. Standing at about three-foot-eleven, his leg is as wide as some adults’ wrists. Unable to sit still, the invitation to show off his strategy on the board in the front of the room is met with a leap and a sprint.

“What’s the difference between this time and this number? You’ve got to subtract the fifteen minutes from 10:15 and then write the rest out as an equation,” he explains proudly. “I’m so good at this now I can see the equation in the first second! If you guys want to get fast at doing this, this is what you’ve got to do. You’ve got to use this strategy!”

Read more Narratively: An Aging Mother’s Animated Love Letter to Her Autistic Son

The kids in this class are not just exceptionally smart. They’re “twice exceptional,” or “2e,” a term that refers to students who are academically gifted and also have learning disabilities.

A co-teacher and a learning specialist accompany the head teacher in this classroom at the Lang School in Manhattan’s Financial District, an institution dedicated to twice exceptional kids. The learning specialist is consoling a girl in the corner who has been crying for over a half hour. This is a normal occurrence. She suffers from anxiety so debilitating she can’t function in a more conventional school.

Although the notion of being well above average in certain academic areas but an underperformer in others doesn’t seem too novel, twice exceptionality is rarely represented in academic literature. Compared to the amount of study and research devoted to special education and gifted education, twice exceptional education receives barely a peep. Many special and gifted education practitioners do not even know the term.

Read more Narratively: The Brutal Excommunication of a Christian Homeschooling Pioneer

The federal government doesn’t track twice exceptionality, but, beginning in 2008, the state of Minnesota researched it during a five-year study of public primary school children. The study determined 14 percent of the gifted students studied were also learning-disabled. (The National Association for Gifted Children defines “gifted” children as having “outstanding levels of aptitude or competence in one or more domains” including math, music, language, painting, dance or sports.)

Some public-school students who are eligible for special education can have Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) developed, but many schools don’t have the resources to match twice exceptional students’ more complex requirements. Assistance may be needed for challenges with focus, organization, motivation, time management, anxiety, depression, motor skills, speech skills, memory, and socialization — as well as teaching designed for gifted students.

* * *

The Lang School was founded by Micaela Bracamonte, a 52-year-old mother who was concerned that her own twice exceptional children weren’t getting the attention and support they needed — and it’s one of just ten schools (all private) in the U.S. exclusively serving twice exceptional students.

Read more Narratively: The Veteran Saving His Comrades from Addiction By Embracing Their “Dysfunctional” Side

As a twice exceptional student herself, Bracamonte’s own academic life, growing up in Bethesda, Maryland, was one of frustration, rebelliousness and conflict, fueled by a lack of support for her twice exceptionality. She could speak three languages by first grade, but was held back because she couldn’t recall the alphabet in order. By third grade, she’d read many of her school’s textbooks, but was still not allowed to advance.

As the anger from being misunderstood and alienated mixed with intellectual boredom, year after year, Bracamonte began to detest social convention and authority. She turned to athletics, pouring 30 hours a week into gymnastics and track and field training, but with bitterness. When she was about to get first, second, or third place in a race — when there was something at stake — she would stop just short of the finish line and walk off the track.

“I wanted to make a point,” she says. “I wanted my coaches and school to know I didn’t care about them, or the medals, or the accolades.”

She believed school failed her, and that pain didn’t fade. Watching her children experience similar issues lit a fire in her.

Bracamonte’s older son, Julien, 18, began his academic career in public school, where his combination of ADHD and a high IQ forced his teachers to confront a challenge they were never trained to meet. Julien was always getting up and walking around the room, a thinking tool for him but a distraction for others in that particular environment.

“Sometimes I feel I need to move around,” Julien says. “I get how that can be disruptive but sometimes I need that.”

One year, his teacher placed a rocking chair in the back of the classroom and forced Julien to sit in it at all times. She dismissed him from school at noon every day, stating that he’d already absorbed the material anyway. It became clear “normal” school was just not a viable option for him.

Bracamonte’s younger son, Pascal, 13, was in public school for kindergarten, where the math and reading were much too simple for him, but he too has ADHD. He was enrolled at Lang by first grade.

“The math is actually hard for me now,” Pascal says, “which is good because I do really enjoy math. I studied trigonometry all of last year.”

* * *

In 2007, Bracamonte decided she’d had enough of watching her sons repeat the miserable experiences she’d had in public school, so she decided to start a new school that would cater to both their gifts and their challenges.

“I found myself spending so much time jerry-rigging my two twice exceptional kids’ educations that I created a school setting in the basement of our house, started inviting other kids into it, hired teachers, trained them, and started getting trained myself as a teacher,” Bracamonte explains. “I realized I was doing a damn good job at it, actually. So I started an official school.”

Bracamonte and her husband, Andreas Olsson, now Lang’s Director for Systems and Education, decided against having a third child or buying a house so they could personally finance the school’s creation. Bracamonte traded her career as a journalist for an obsession with creating the best twice exceptional school possible, crediting her journalistic inquiry — and severe ADHD — for her success.

After hiring an education attorney to assist with writing the school’s charter, applying for and receiving 501(c)(3) non-profit status, they found commercial real estate. The space had to meet legal guidelines for a school’s architecture, so the attorney recommended an architect to hire.

Bracamonte assembled a Board of Directors consisting of some of the Northeast’s most experienced twice exceptional experts, and hired the teachers who performed best in her home-school. She then called many child psychologists to pitch Lang as a resource for the appropriate patients. Exhausted, dejected parents of twice exceptional children were overjoyed.

“I couldn’t imagine what we would have done if Lang wasn’t an option,” Joel Brenner said, mother of Micah, nine, a fourth grader with Asperger syndrome who has been a Lang student since kindergarten. “They get him and have given him an incredible sense of ‘I can do this.’”

Classes filled up. By then, it was 2009.

Lang’s tuition for twice exceptional students is $60,000 per school year, with roughly 40 percent of the student body receiving a reduced rate whereby the school is compensated the difference by New York City’s Department of Education.

Under Bracamonte’s direction, a key focus of the Lang School is to find a student’s strengths and build as much of their curriculum around them. The goal is for the student to capitalize on these strengths so they are capable of specializing in a certain area, but also to feel intrinsic motivation to cultivate more compensatory skills in other areas.

Bracamonte taught a screenwriting class with two students where one always struggled with writing. He was known among the teachers and students more for his quantitative skillsets.

“So all we did was write dialogue, because he’s a hell of a talker, and I scribed for him,” Bracamonte explains. “In an hour, we wrote a seven-minute screenplay. I’ve convinced this kid he’s a writer. His language use is magical. Step by step, I can see this kid doing this for a living. He just can’t figure out how to get it on paper on his own yet. Our job is to build that bridge.”

Lang became a lab to test out both tried-and-true and the latest research-driven methods in special education and gifted education. But Bracamonte didn’t have formal teaching credentials such as a degree in education (and still doesn’t) or prior teaching experience.

“I think I’m very lucky to not have education credentials.” Bracamonte says. “I don’t feel I’m lacking something. I’m actively avoiding them, because I don’t want to get locked into that mindset. You learn by doing, working tirelessly, self-reflection, asking questions and taking things to the next level. I’m open to risk, very comfortable with it and I tend to confront challenges head on.”

But while self-taught Bracamonte improvised with the structure and vision for the Lang School’s curriculum, pulling in new research from gifted, special and general education, some of her board members – mainstays in the twice exceptional educator community who have those education credentials Bracamonte says she can do without – wanted to stick with more time-tested methods.

Bracamonte is quick to point out that most on her staff are highly credentialed but, despite that, constructing an expertized school wasn’t her way. She continued developing an institution that was experimental compared to other twice exceptional schools, and tensions with those members of the board flared – they are no longer affiliated with Lang.

One former board member, who asked not to be identified because she did not want to jeopardize relationships in the community, said Bracamonte would not acknowledge consensus educational principles, and was overly distrustful of the rest of the twice exceptional community.

“Micaela’s brilliant, she’s a visionary, but she’s very unpredictable,” she said.

Bracamonte believes the twice exceptional community has an “old guard,” as she put it: “folks involved with other twice exceptional schools, folks on my original Board, folks who have an old-fashioned, not child-centric, not parent-centric, rather elitist view of education. So I feel our school is headed towards some new territory.”

She believes the twice exceptional model her school is building for its students is potentially paradigm shifting. By studying the New York City Department of Education’s data on test scores, gifted students and Individualized Education Programs, she estimates there are at least 50,000 twice exceptional students in New York City. This doesn’t count students unrecognized because of cultural, language or economic reasons. But she knows how hard it is to run a highly unconventional school that causes even some in her niche to be skeptical.

“I know the population is huge. I know the possibilities are great. I know the scale could be large. I will work hard and continue to work hard until I’m not working anymore. We’ll see where this goes.”

How to combat racial bias: Start in childhood

(Credit: Getty/FatCamera)

Racial bias can seem like an intractable problem. Psychologists and other social scientists have had difficulty finding effective ways to counter it – even among people who say they support a fairer, more egalitarian society. One likely reason for the difficulty is that most efforts have been directed toward adults, whose biases and prejudices are often firmly entrenched.

My colleagues and I are starting to take a new look at the problem of racial bias by investigating its origins in early childhood. As we learn more about how biases take hold, will we eventually be able to intervene before any biases become permanent?

Measuring racial bias

When psychology researchers first began studying racial biases, they simply asked individuals to describe their thoughts and feelings about particular groups of people. A well-known problem with these measures of explicit bias is that people often try to respond to researchers in ways they think are socially appropriate.

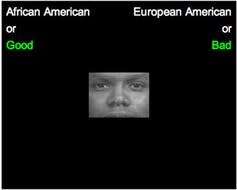

The kind of sorting task the Implicit Association Test presents to get at biases participants may not even be aware of.

Project Implicit

Starting in the 1990s, researchers began to develop methods to assess implicit bias, which is less conscious and less controllable than explicit bias. The most widely used test is the Implicit Association Test, which lets researchers measure whether individuals have more positive associations with some racial groups than others. However, an important limitation of this test is that it only works well with individuals who are at least six years old – the instructions are too complex for younger children to remember.

Recently, my colleagues and I developed a new way to measure bias, which we call the Implicit Racial Bias Test. This test can be used with children as young as age three, as well as with older children and adults. This test assesses bias in a manner similar to the IAT but with different instructions.

Here’s how a version of the test to detect an implicit bias that favors white people over black people would work: We show participants a series of black and white faces on a touchscreen device. Each photo is accompanied by a cartoon smile on one side of the screen and a cartoon frown on the other.

Example of a screen a child would see.

Gail Heyman, CC BY-ND

In one part of the test, we ask participants to touch the cartoon smile as quickly as possible whenever a black face appears, and the cartoon frown as quickly as possible whenever a white face appears. In another part of the test, the instructions are reversed.

The difference in the amount of time it takes to follow one set of instructions versus the other is used to compute the individual’s level of implicit bias. The reasoning is that it takes more time and effort to respond in ways that go against our intuitions.

Do young children even have racial biases?

Explicit racial biases have been documented in young children for many years. Researchers know that young children can also show implicit bias at the earliest ages that it has been measured, and often at rates that are comparable to those seen among adults.

Some studies suggest that precursors of racial bias can be detected in infancy. In one such study, researchers measured how long infants looked at faces of their own race or another race that were paired with happy or sad music. They found that 9-month-olds looked longer when the faces of their own race were paired with the happy music, which was different from the pattern of looking times for the other-race faces. This result suggests that the tendency to prefer faces that match one’s own race begins in infancy.

These early patterns of response arise from a basic psychological tendency to like and approach things that seem familiar, and dislike and avoid things that seem unfamiliar. Some researchers think that these tendencies have roots in our evolutionary history because they help people to build alliances within their social groups.

However, these biases can change over time. For example, young black children in Cameroon show an implicit bias in favor of black people versus white people as part of a general tendency to prefer in-group members, who are people who share characteristics with you. But this pattern reverses in adulthood, as individuals are repeatedly exposed to cultural messages indicating that white people have higher social status than black people.

A new approach to tackling bias

Researchers have long recognized that racial bias is associated with dehumanization. When people are biased against individuals of other races, they tend to view them as part of an undifferentiated group rather than as specific individuals. Giving adults practice at distinguishing among individuals of other races leads to a reduction in implicit bias, but these effects tend to be quite short-lived.

Children used an app that assessed their implicit racial bias.

Li Zhao, CC BY-ND

In our new research, we adapted this individuation approach for use with young children. Using a custom-built training app, young children learn to identify five individuals of another race during a 20-minute session. We found that 5-year-olds who participated showed no implicit racial bias immediately after the training.

Although the effects of a single session were short-lived, an additional 20-minute booster session one week later allowed children to maintain about half of their initial bias reduction for two months. We are currently working on a game-like version of the app for further testing.

Just one step along the way to a more egalitarian society.

AP Photo/Ted S. Warren

Only a starting point

Although our approach suggests a promising new direction for reducing racial bias, it is important to note that this is not a magic bullet. Other aspects of the tendency to dehumanize individuals of different races also need to be investigated, such as people’s diminished level of interest in the mental life of individuals who are outside of their social group. Because well-intended efforts to reduce racial bias can sometimes be ineffective or produce unintended consequences, any new approaches that are developed will need to be rigorously evaluated.

And of course the problem of racial bias is not one that can be solved by addressing the beliefs of individuals alone. Tackling the problem also requires addressing the broader social and economic factors that promote and maintain biased beliefs and behaviors.

And of course the problem of racial bias is not one that can be solved by addressing the beliefs of individuals alone. Tackling the problem also requires addressing the broader social and economic factors that promote and maintain biased beliefs and behaviors.

Gail Heyman, Professor of Psychology, University of California, San Diego

10 websites every school computer lab should bookmark

This Monday, March 30, 2015 photo shows a Hisense Chrome laptop in San Francisco. (Credit: AP)

When kids visit the computer lab after school, they’re usually there to finish homework and pass the time productively, so you want them to access the best tools possible. These math, reading, news, and reference websites can help kids practice skills, find facts, and explore cool topics. And if you have a kid who’s clamoring to get on the computer as soon as the last bell rings, these sites can satisfy the hankering for screen time and offer educational opportunities – all at once! (Some of these sites have a subscription fee and offer special packages for schools, but most are available for home use, too.)

Starfall.com, grades K–2, free-to-try, $35/year for more content

As one of the best early-reader sites around, Starfall.com has activities, videos, and solid phonics practice to get kids reading. Kids work at their own pace and have access to different kinds of text to help them foster a lifelong love of reading.

Khan Academy, grades K–12, free

Step-by-step videos and practice exercises make this a deserved staple in the academic website hall of fame. Every type of math is covered here in addition to computing, science, and history. Though it’s best when kids already understand the concepts and just need help with the nitty-gritty, this resource gives kids access to independent, self-paced learning.

IXL, grades K–12, $9.95/month

With both reading and math practice, this site adapts to your kid’s progress without a lot of distractions. It’s mostly focused on drills, so it’s best for kids who already understand basic concepts but still need feedback.

BrainPOP Jr., grades K–3, free-to-try, $9.45/month

With videos and games about language arts, math, and more, this is a good site for kids to explore either for targeted practice or just for fun. Because it has lots of audio, nonreaders and beginning readers can navigate easily.

Arcademic Skill Builders, grades 1–6, free, more customization for $20/year

Fun games, multiplayer mode, and helpful feedback let kids play as they learn with this set of games. Kids won’t care that the games are aligned to national education standards, but parents and teachers will!

BJ Pinchbeck’s Homework Helper, grades 2–12, free

From geography to mythology, this site offers a wide variety of topics and links so kids don’t have to wade through a confusing Google search results page. It’s possible to navigate away from the original links to other places on the web, so it’s best used with some guidance.

Newsela, grades 2–12, free

This site is all about making current events accessible to every reader. Instead of a one-size-fits-all approach, Newsela offers the same article at different reading levels so kids can get the information they’re interested in without unnecessary frustration. There’s also an annotation feature for kids doing research and a Spanish section.

Digital Public Library of America, grades 5–12, free

If your kid needs some very specific information, a time line, or a primary source, this is the site to use. Though it’s not little-kid-friendly, its resources are deep and wide. Here, kids doing research can practice using a search tool effectively and receive tons of search results that might be hard to dig up on the internet at large.

Google Art Project, grades 7–12, free

Budding artists can look through thousands of pieces of fine art and curate their own collections. The accompanying lessons and activities round out the experience and let kids interact with the art in different ways. From Monet to Warhol, this resource covers a lot of ground and can inspire all manner of makers.

Shmoop, grades 9–12, $24.68/month

With everything from test prep to CliffsNotes-style guides, this site not only delivers the goods but serves it up with a spoonful of sarcasm, making it more amusing for teens to use. And even though the content is humorous, it’s all written by folks with advanced degrees, so it’s both appealing and accurate.