Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 242

November 12, 2017

Senators introduce bill to reduce “completely preventable waste”

(Credit: AP Photo/Andrew Harnik, File)

This story was co-published with NPR.

Two U.S. senators introduced legislation Tuesday requiring federal agencies to come up with solutions to the waste caused by oversized eyedrops and single-use drug vials, citing a ProPublica story published earlier this month.

The bipartisan effort by Sens. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., and Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, calls for the Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to come up with a plan to reduce the waste, which is estimated to cost billions of dollars a year.

“With the skyrocketing costs of prescription drugs, American taxpayers shouldn’t be footing the bill for medicine going to waste,” Klobuchar said in a press release announcing the bill, known as the Reducing Drug Waste Act of 2017. Sens. Dick Durbin, D-Ill., and Jeanne Shaheen, D-N.H., are co-sponsors of the legislation.

Grassley called it “common sense” legislation. “It’s no secret that wasteful health care spending is a significant contributor to the rising cost of health care in the United States,” he said in the release.

ProPublica’s story showed how drug companies force patients to pay for expensive liquid medications, such as eyedrops and cancer drugs, which are produced or packaged in ways that lead to waste. Drug companies have known for decades that eyedrops are larger than what the eye can hold — sometimes two or three times too big. As a result, the excess medication overflows the eye and runs down users’ cheeks or is ingested through their eye ducts. This waste causes some patients to run out of medicine before their insurers allow them to refill their prescriptions.

Some of the largest producers of eyedrops — from expensive vials for eye conditions like glaucoma to over-the-counter drops for dry eyes — have done research to show that smaller drops work just as effectively. But they have continued to produce larger drops. Novartis, owner of Alcon, one of the leading eye care companies, said the larger drop size allowed a margin of safety to help patients administer the drops. Other eyedrop makers declined to comment.

ProPublica also examined how the packaging of cancer drugs often results in some of the drug being tossed in the trash. The drug company Genentech, for example, switched earlier this year from sharable vials of its cancer drug Herceptin to single-use vials, causing excessive waste. One California cancer center estimated the change would lead to an average of $1,000 in wasted medicine per patient, per infusion. Patients are billed for such waste.

ProPublica also cited research led by Dr. Peter Bach, director of the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. Bach’s study, also reported in 2016 in The New York Times, found that single-use cancer vials wasted nearly $3 billion annually in cost increases and medicine that must be thrown away.

“From cancer drugs to expensive eye-drops, many drug companies insist on selling their products in excessively large, one-size-fits-all vials that contain more medicine than the average patient needs,” said Durbin, one of the lawmakers sponsoring the bill. “This is a colossal and completely preventable waste of taxpayer dollars, and it means American patients and hard-working families are paying for medication that gets tossed in the trash.”

The waste in the packaging of liquid medications is part of an ongoing ProPublica series. In recent months ProPublica has written about hospitals throwing away brand new supplies and nursing homes flushing perfectly good medication. We have also looked at drug companies combining cheap medications and charging a premium for it. And we explored the arbitrary way drug expiration dates are set, resulting in the disposal of tons of still safe and potent medication.

Bach’s study proposed making drug companies produce vials in additional sizes, so they could be delivered in a way that’s more efficient, or requiring drug companies to give rebates on unused medicine. He said it’s too early to know what the federal government’s solution would be, but the new bill is a positive step forward.

“This could be legislation that saves Medicare and sick patients a lot of money,” Bach says.

Dr. Alan Robin, a Baltimore ophthalmologist whose research was featured in ProPublica’s story, has been urging drug companies to reduce the size of their eyedrops for decades. When he heard Monday about the senators’ proposed legislation, he started to cry.

“I’m literally crying with joy,” Robin says. “I’m very concerned about both the cost issues associated with waste, the side effects on patients, and also the environmental impact of waste.”

What scientists know so far about Planet Nine

(Credit: Salon/Ilana Lidagoster)

Is there a ninth planet in our solar system? That’s a conclusion many astronomers are leaning toward, and scientist Jackie Faherty joined Salon’s Alli Joseph on “Salon Talks” to explain why.

Faherty is a senior scientist and senior education manager in the department of astrophysics and the department of education at the American Museum of Natural History, and she said that most of the evidence pointing to a ninth planet “comes from looking at objects that are in what’s called the Kuiper Belt. The Kuiper Belt is this belt of objects that’s out a little beyond Pluto, which is kind of leftover debris from when the solar system formed.”

Last year, two scientists published a study that investigated the elliptical orbits of six known objects in the Kuiper Belt. “Their orbits appear to be highly elliptical and the way they were orbiting gave evidence for something pushing on them,” Faherty said. “One thing that could be causing this gravitational perturbation on these objects would be another planet in our solar system that’s much farther away than all of the others.”

Watch the video above to find out how the size of this ninth planet compares to Earth and its location in the solar system. Watch the full “Salon Talks” conversation on Facebook to hear more about how the possible discovery of Planet Nine affects Pluto.

Tune in to SalonTV’s live shows, “Salon Talks” and “Salon Stage,” daily at noon ET / 9 a.m. PT and 4 p.m. ET / 1 p.m. PT, streaming live on Salon and on Facebook.

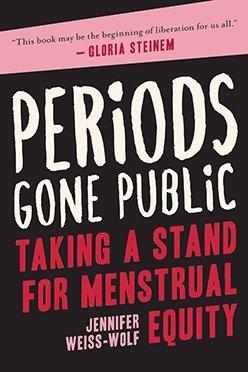

How I became a tampon tax crusader

(Credit: Salon/Ilana Lidagoster)

Menstruation is having its moment. Surfing the crimson wave of fame, so the period slang goes. I’m actually a bit of a latecomer to the conversation. It wasn’t that I previously avoided or had any particular aversion to it. As a mom of three teens, I’m open and pragmatic about everything they need to know. With friends, I am quick to commiserate over a menstrual mishap. I’ll gladly lend or borrow a tampon when the moment calls for it.

But periods as a matter of political discourse? The driver of a policy agenda? Period feminism? Quite honestly, not ideas I’d ever seriously entertained or even imagined.

That changed on January 1, 2015. As the New Year dawned, I felt in need of extra momentum, aiming for as much potential and purpose as I could muster. And so I trekked to Coney Island, Brooklyn with a cohort of friends (and hundreds of others) crazy enough to take a dip in the icy Atlantic Ocean. The Polar Bear Club New Year’s Day swim is one of New York City’s finest traditions — a raucous scene and freezing cold mishmash of quirkily costumed, skin-baring revelers.

When asked by a local reporter about why one would participate, my friend Peggy’s answer hit the nail on the head: “The camaraderie is almost inexplicable. Our group runs into the ocean holding hands. People think it’s crazy. And maybe it is. But it’s actually a very proactive, symbolic way to set an intention and direction for the remaining 364 days of the year. Like grabbing the year by the hand and saying, ‘This is how we’re gonna do this.’”

We took the plunge doing our very best Wonder Woman impersonations, four middle-aged women decked out in matching star-spangled swimsuits, wrist cuffs, and capes. I’ve always secretly revered the Amazonian warrior. (True fact: I hyphenated my name when I got married so I could claim the initials “WW.”) The superhero theme was absolutely part of the adrenaline-driven sprint into the sea that Peggy described. We shivered, even shimmered after a full body dousing with golden glitter, courtesy of a pack of urban mermaids in drag whose towels were parked next to ours on the beach.

Later on, once I thawed out and shook off all the sand and glitter, I logged on to Facebook to share my glorious photos of the day. And that was when I saw the post. An acquaintance, a local mom of two girls, announced her family’s drive to collect tampons and pads for our community food pantry. Their project was simply named, “Girls Helping Girls. Period.”

I was immediately captivated—and honestly, even mildly ashamed that I’d never, ever considered this before. If periods could be a hassle for me, someone with the means to have a fully stocked supply of tampons, it was nakedly, painfully obvious that for those who are poor, or young, or otherwise marginalized, menstruation could easily pose a real obstacle and problem. A self-aware, self-professed feminist, how had I managed to completely overlook this most basic issue?

I had to know more. And so, spent the rest of New Year’s Day obsessively scouring the Internet to see what I could find. Here’s what my Google search on the first day of 2015 turned up: It took some digging, but there was indeed reporting about the lack of access to menstrual products and adequate hygiene facilities in countries like India, Nepal, Kenya, Bangladesh, and other places—enough so that it had been recognized as a public health and human rights issue by the United Nations and the World Health Organization. The key culprits named included extreme poverty, lack of health education and sanitation, and an enduring culture of taboo and shame. Stories of creative enterprise and innovation to tackle this problem were prevalent, too.

Coverage of menstrual access issues for the poor in the United States was minimal, though there was one story that stood out. A few months prior, in August 2014, the Guardian published “The Case for Free Tampons” by Brooklyn-based writer Jessica Valenti. She wrote: “Menstrual care is health care, and should be treated as such. But much in the same way insurance coverage or subsidies for birth control are mocked or met with outrage, the idea of women even getting small tax breaks for menstrual products provokes incredulousness because some people lack an incredible amount of empathy . . . and because it has something to do with vaginas.”

A few more clicks revealed that her ideas had triggered a barrage of vitriol. And, yes, it clearly had something to do with vaginas. Outraged conservatives fired back across the Internet. Among them, Milo Yiannopoulos derided Valenti’s column as, “[a] volley of provocation, misandry, and attention-seeking from the far-left in a political atmosphere that rewards women . . . for demanding MORE FREE THINGS.” Valenti captured some of the many hundreds of crude responses on Storify, perhaps most neatly summarized by this tweet: “If you’re so worried abt tampon availability, maybe U need 2 stick a few fingers in UR you-know-what to stem the bleeding.” (Yeah, we-know-what. I guess that’s kind of the point.)

As for any systematic attention to the scope of this issue as a domestic matter? None at all. What I unearthed amounted only to an occasional blog post or lone call for donations by a local shelter or food pantry. Nothing that attempted to narrate, quantify, or formally document the potential problem, or—more disappointingly—even sought to identify or acknowledge it as one.

During the months that followed, my interest swelled. Truly, this issue struck me as one of the most vital outlets for my energy and skills—as a writer, lawyer, policy wonk, feminist, even as a mother. By day, my job at the Brennan Center for Justice, a think tank affiliated with New York University School of Law, had me contemplating the mechanics of achieving legal and democratic change in America. After hours, I kept reflecting on menstruation, placing it squarely in the context of social justice, civic participation, and gender equity. Before long, I began to connect with journalists, lawmakers, activists, and entrepreneurs, and found myself entrenched in a growing global network of people who were equally intrigued and motivated by the power of periods.

And so began the journey—from a freezing cold Wonder Woman on the beach, to the inauguration of what NPR came to call “The Year of the Period.” (One year later, almost to the minute, NPR made this declaration on New Year’s Eve, December 31, 2015.)

Today the landscape looks remarkably different. We’ve gone from zero to sixty, periods as a whisper or insult to the initiation of a full-blown, ready-for-prime-time menstrual movement. And thus unlocking a radical secret: half the population menstruates! There really are ways to address periods that are practical, proactive, and even political. In so doing, somehow we have achieved a level of discourse that has otherwise eluded society for nearly all of time. Periods have indeed gone public.

And with that, so too has my own story crystallized. I now believe unequivocally in the sheer sway of menstruation as a mobilizing force, so much so it has turned my world upside down. I have spent the last few years crisscrossing the globe to discuss menstruation with lawmakers and innovators, testify before legislatures, brief reporters and editors, speak at universities, and shout into megaphones at rallies. I’ve written op-eds and essays on the topic, even drafted model bills. I’ve met and joined forces with a diverse array of inspiring activists from Mumbai to Nairobi, London to Kathmandu, and New York City to Los Angeles.

Wonder Woman herself even came home to roost. Since that fateful New Year’s Day, I scored my own, admittedly oddball, alter ego and fighting persona. According to New York magazine, I morphed into the nation’s “tampon crusader.” Bustle went with “badass menstrual activist.” Tweeted at by the editors at Cosmo: “slayer of the tampon tax.” Slayer! Damn. Even my kids were impressed.

It has come together under an umbrella I call “menstrual equity.” And what I mean by the phrase is this: In order to have a fully equitable and participatory society, we must have laws and policies that ensure menstrual products are safe and affordable and available for those who need them. The ability to access these items affects a person’s freedom to work and study, to be healthy, and to participate in daily life with basic dignity. And if access is compromised, whether by poverty or stigma or lack of education and resources, it is in all of our interests to ensure those needs are met.

The inaugural political fights for menstrual equity in the United States thus far have been the push to eliminate sales tax on menstrual products (a.k.a. the “tampon tax”) and to ensure they are freely accessible to those most in need—low-income students, the homeless, the incarcerated. These campaigns have seen early success with surprisingly robust bipartisan support and interest. But that is only the beginning. A truly comprehensive menstrual equity agenda would eventually drive or help reframe policies that foster full participation and engagement in civic society—and that accept, even elevate, the reality of how menstruating bodies function.

The need for such perspective is increasingly urgent given today’s treacherous political environment. “The Year of the Period” is now saddled with the misogyny of and daily danger unleashed in the era of Trump. This American president, who has a history of openly bragging about sexual dominance—caught on tape boasting crassly how he’d grab women “by the p**sy”—singled out menstruation for a special dose of derision early in the 2016 campaign when he taunted then FOX News correspondent Megyn Kelly for having “blood coming out of her wherever.” The administration and current Congress remain hell-bent on trampling hard won protections for civil rights and reproductive freedom. Many statehouses, too, are emboldened to advance laws that profoundly compromise our health and bodily autonomy. The fact that we’ve begun to coalesce a successful movement around menstruation may be but one bit of hope—new blood (literally!) and momentum in the greater fight for our lives.

My activism has also led me to two issues that I hadn’t fully appreciated previously. First, the impact of menstruation on those who are transgender or gender nonconforming, and the default culture of their exclusion from the conversation. It is a challenge, given that the vast majority of people who have periods are cisgender women and girls, as well as that so much of menstrual taboo is rooted in ages-old misogyny. Ultimately, though, everyone and anyone who menstruates needs to be included in discussions and decisions about their own health.

The other is environmental—in particular, balancing the dangers of our nation’s throwaway culture and reliance on disposable products with helping the most vulnerable populations manage menstruation. The convenience of conventional tampons and pads can’t be understated. Reusable options like menstrual cups or cloth pads are often not feasible for those without access to basics like clean water, soap, and privacy; and products made with organic or all-natural ingredients can be prohibitively expensive. But it is critical to fight for safe, eco-friendly options for all. The impact of menstrual products on our bodies—and the entire planet—is decidedly a feminist and social justice issue.

At its core, a menstrual equity movement is about challenging us to face stigma head-on. And about advancing an agenda that recognizes the power, pride, and absolute normalcy of periods. Indeed, President Trump, we do have blood coming out of our wherever. Every month. It is not a secret.

As for me, it has been nearly three years since Wonder Woman made her first appearance on a cold Brooklyn beach. The moral of my own story just may be: don’t ever underestimate the determination of a woman with a cape. And a tampon.

Fox News viewers boycott Keurig after it pulls ads from “Hannity”

Sean Hannity (Credit: Getty/Nicholas Kamm)

Keurig could not have anticipated the firestorm it created Saturday when it instructed Fox News to pull its ads from airing on Sean Hannity’s program. The coffeemaker company informed Media Matters president Angelo Carusone that it made the move following Hannity’s defense of U.S. Senate candidate Roy Moore, who was accused last week of improper sexual conduct with a 14-year-old girl when he was 32.

Spread the word. @Keurig has done what many other big name advertisers, like Cadillac and E-Trade, have done and removed their ads from Hannity’s show. pic.twitter.com/EPywgjjAvL

— Angelo Carusone (@GoAngelo) November 11, 2017

Keurig joined a list of big-name brands that have taken their ads off Hannity’s show in 2017.

CONFIRMED: No more @etrade ads on Hannity’s show. You can move on to another advertiser. Your participation matters. Details + List (w/contacts): https://t.co/t8qllogMIi — Angelo Carusone (@GoAngelo) November 10, 2017

The Fox News host was not too pleased Saturday, to say the least, which became readily apparent when he started to indiscriminately retweet accounts that were tagging Keurig in its tweets.

Media Matters defended Menendez on sex with girls, plus Hillaryhttps://t.co/fRoulN7DAI@Keurig @23andMe @NaturesBounty @realtordotcom @georgesoros @seanhannity https://t.co/7e97h7bJ7y pic.twitter.com/qfHt7EKTcb

— Fire Maddow (@FireMaddow) November 12, 2017

The feud between Hannity and Keurig extended into the morning, when Fox News viewers began expressing their outrage by sharing videos of them destroying their coffeemakers.

Look what I found #BoycottKeurig #Keurig pic.twitter.com/P2BVRoxOjb — Reverend Bob Levy (@TheRevBobLevy) November 12, 2017

I pulled an “Office Space” with my Keurig… Would be a shame if everyone else joined me in the Keurig Smash Challenge #BoycottKeurig #IStandWithHannity #SundayMorning pic.twitter.com/yEADeRC006

— Angelo John Gage (@AngeloJohnGage) November 12, 2017

Liberals are offended by this video of a Keurig being thrown off of a building. Please retweet to offend a Liberal.#BoycottKeurigpic.twitter.com/0qbHlmyqcA — Collin Rugg (@CollinRugg) November 12, 2017

The bizarre campaign only drew ridicule from the rest of Twitter, who couldn’t believe that people would become so angry over a pulled media campaign.

RIGHT: destroy ur keurig to own the libs!

LIBS: buy more environment-destroying coffee pods to own the right!

ME: I would still like to see the piss tape plz

— KRANG T. NELSON (@KrangTNelson) November 12, 2017

Moore supporter: Hi I know this is a liberal bastion but I need coffee and I had to throw away my Keurig because feminism and liberal media made people gullible about relationships with fourteen year olds that really weren’t that bad

Barista: fuck this comp lit degree so hard

— Customary Popehat Behavior (@Popehat) November 12, 2017

Posting a Keurig-smashing video is virtue-signaling — Patrick Monahan (@pattymo) November 12, 2017

In response to the boycott, coffee maker @Keurig is coming out with a new flavor: Grounds for Impeachment. — Patrick S. Tomlinson (@stealthygeek) November 12, 2017

Wait wait wait, there’s a Keurig MACHINE? I’ve been eating them straight out of the pods!!

— Pixelated “Pixelated Boat” Boat (@pixelatedboat) November 12, 2017

November 11, 2017

How to survive Thanksgiving if you have to spend it with diehard Trump supporters

(Credit: Getty/Shutterstock/Photo montage by Salon)

For some of us, the approaching holidays are a time of dread. Beyond beloved traditions like overindulging on food, alcohol and shopping, for some people, it’s inevitably a time when they will clash with loved ones over politics. Plenty of Americans have family members with opposing political views, and Trump has made these divisions even more severe. If progressives are having trouble understanding the conservatives in our own families, how can we begin to empathize with Trumpers who don’t share our blood?

The sharp division in beliefs among Americans today has prompted some to search for solutions. Meet Narrative 4, which was launched five years ago with the goal of spreading the practice of “radical empathy” across the world using the act of storytelling. As the group’s founder, author of “Let The Great World Spin” Colum McCann, says, “every story has a place, even the stories we don’t like.” McCann proposes radical empathy as a way to actually make people listen to one another.

Those who live near or on college campuses may recognize the term, as radical empathy has taken off in universities in recent years. It entails literally placing oneself in another’s shoes by living in a person’s house, shadowing them or otherwise initiating close contact. Radical empathy means knocking down the walls that exist between yourself and another person to better understand them.

Narrative 4 brings radical empathy practice to schools, universities and workplaces in the form of workshops where participants follow a simple story exchange. Partners A and B share a story with one another; then, Partner A tells Partner B’s story to a group using the first person, as if B’s experiences actually happened to A. Then the two switch. Participants in Narrative 4’s radical empathy story exchanges say they often feel changed after the experience. “It’s changed my life for the better,” said Narrative 4 student ambassador Alondra Marmolejos. “It’s such a positive and beautiful thing.”

In these divisive political times, empathy is a more important skill than ever. Lee Keylock, Narrative 4’s director of global programs, agrees that using empathy to understand different political views is hugely important: “It’s one of our biggest priorities this year — it’s why our phones are ringing off the hook.”

While the group focuses on the exchange of stories individual-to-individual, their work frequently resonates with the larger project of spreading political empathy across parties. Perhaps their most well-known project is a collaboration with New Yorker Magazine last year, when Narrative 4 brought together a group of individuals with drastically opposing views on one of the most divisive issues in the U.S. today: gun control. Participants in the gun control radical empathy session included a prominent Second Amendment advocate, members of the police and Marines, a parent of Sandy Hook victims, and Samaria Rice, mother of Tamir Rice.

“People crave discourse,” said Keylock. “Debate isn’t the only way to go.”

Much of Narrative 4’s radical empathy practice focuses on students and young people. “It’s easier to get them when they’re young because they come with this fresh, open-minded attitude,” said Keylock. “They find they’re very similar to each other. Wheres as adults have had more time to become cynical. They think they need to be guarded.”

But older progressives can bring the practice into their own lives, too. “When I look at the news right now, there’s lots of shouting and name-calling and vilifying on both sides, and that includes the Democrats,” said Keylock. “When you start labeling people as an ideology, you’re not really seeing them as a person. Let’s face it, not every conservative voice is what they’ve been charged within the media, which is homophobic, racists, Islamophobic. That’s just not the case. There are narratives out there that are being missed, so you need to have an open mind.”

Since the 2016 election, a popular explanation for the surprising wave of Trump votes is that Trump tapped into fears and concerns of the white working class that Democrats have long ignored. Whether you give credit to that storyline or not, it seems true that Trump supporters felt their stories weren’t being heard or represented by the mainstream media, and in Trump, they saw a voice they believed would speak for them, misguided as that belief may seem. Keylock agrees with this analysis. “In my experience, one of the hardest voices to bring to the table is the conservative voice. Conservatives are a little scared to speak out because they feel like they get shafted.”

He continues: “What happened is that because of all the labeling, people like to dig their heels in the sand. If you ask a political question, people have their argument ready to roll. We don’t do that; we get people to share their personal stories, and we get them to sort of become lovestruck with each other. It’s amazing what happens. We get to some really deep places. We’ve started friendships among these political divides.”

He said hundreds of Narrative 4 story-exchange participants with opposing political views later become Facebook friends and now frequently defend one another’s political posts. It’s incredible to imagine people with different beliefs behaving civilly on the internet, where the cloud of anonymity turns humans into trolls. But Keylock says he’s seen it happen many times.

Narrative 4 does not claim to have a 100 percent success rate when it comes to healing divides. Sometimes, two people can be so different in terms of their life experiences it’s simply impossible for them to empathize with one another. “Usually on the issue of guns,” Keylock said. “It’s very contentious. Sometimes it’s not the right time to bring people into a room together to do it — if you’ve lost a kid to gun violence, it’s hard for that person to even entertain the idea. On those issues, you need to give it more time. The more times you bring people together, the more success you have.”

But, Keylock continued, “Honestly, I’ve very rarely seen the impossible. Political divides can be turned around really quick.”

Keylock also shared advice for those of us with Trump supporters in our families as the holidays approach. “Empathy takes a massive amount of courage, even though it’s considered a soft skill. We have to be vulnerable, be ready to let go. You have to listen to what somebody is saying. That doesn’t mean accept it blindly, but you learn nothing from talking and everything from listening. All people’s stories matter.

“Go in, open your ears, watch your tone. Then tell them your story. A lot of these conversations are bred from fear and ignorance. That turns into hate later. But empathy is about being vulnerable and courageous, and listening and being present. Those are leadership skills. If you can’t do that, how can you lead your conversation forward?”

Also: “Breathe, meditate.”

Does American culture shame too much — or not enough?

(Credit: PathDoc via Shutterstock)

The word “shameless” is being tossed around an awful lot these days, which might speak to what many see as the country’s increasingly coarse, vitriolic political discourse. Perhaps, the thinking goes, American culture could use a dose of shame and humility.

But what about people harassed on social media, like Walter Palmer, the dentist who hunted and killed Cecil the lion? Sure, he might have exercised poor judgment. But was it poor enough that he deserved to have his wife and daughter not only shamed but threatened?

As I point out in my recent book “Shame: A Brief History,” the use of shame in American society has a clear historical arc.

But the role played by this emotion — which people feel when they’ve violated group standards — has also been complicated by several recent changes to the country’s legal, political and media ecosystems.

These shifts raise questions about how this powerful but unpleasant emotion should be handled in contemporary America.

A new, ‘enlightened’ direction

Western societies, including the American colonies, once relied heavily on shame. There was a deep belief in the importance of conformity to community stability. There was also a dearth of other resources we rely on today — such as policing — to enforce order.

Colonial Americans felt little compunction in imposing shame-based punishments like public stocks, whose replicas now amuse camera-toting tourists in New England. There was even a word no longer in use — “shamefast” — that described people who were mindful about avoiding shameful situations.

All this began to change in the late-18th century, when the currents of the Enlightenment started to spread throughout Western culture, and public leaders began to reevaluate the importance of human dignity.

Shaming, Founding Father Benjamin Rush wrote in 1787, “is universally acknowledged to be a worse punishment than death.”

Hyperbole aside, the actions of Americans started to reflect this new wisdom. Public stocks began to be abolished by law, beginning with Massachusetts in 1804. Parents were advised to avoid shaming their kids, lest it damage their confidence. (The popular use of the word “self-esteem” traces back to as early as 1856.)

Of course shame didn’t disappear; various people in positions of authority continued to deploy it, from boot camp drill sergeants to coaches of sports teams. Nonetheless, disapproval of shame-inducing tactics persisted. Schools gradually cleared out the most blatant practices (dunce caps, for example, were abandoned by the 1920s). All sorts of groups urged that people no longer be shamed for their sexual proclivities or their disabilities. A greater tolerance emerged that left people freer to accept treatment for psychological problems or to disclose their sexual identity.

In recent decades, psychology research has found that feelings of shame can demoralize people or generate aggression because they make individuals feel bad about themselves. (This differentiates shame from guilt, which, because it focuses on a person’s acts rather than his or her character, can lead to apology and redress.)

Today, public scholars like social work researcher Brené Brown continue to talk about these findings, urging those suffering from shame to throw the emotion aside and call their accusers to account — shaming the shamers, as it were.

Shame’s revival

The critical view of shaming in Western culture is now entrenched: While the behavior persists, it’s often condemned, and a variety of institutional changes, from grade inflation to prison reform efforts, limit its impact.

And this continues to change our society in important ways, loosening a number of traditional constraints that, if violated, used to lead to public shaming. Unmarried middle-class women can now proudly bear children, while public listing of school grades is outlawed.

Recently, however, attitudes toward shaming have shifted, even as the chorus of disapproval continues. According to a Google Ngram search, references to shame in written texts — in decline in the United States since the mid-19th century — have, in recent decades, increased far more than in other English-speaking countries.

Frequency of Shame in American English, 1800-2008, Google Ngram Viewer.

The result, at least implicitly, is a new debate, and another divide in American culture.

By my reading, three sources account for the change. First, a number of conservative judges in the 1960s ruled that shaming was an appropriate punishment for certain crimes like drunken driving or petty theft. The stocks haven’t been reintroduced and many higher courts have disputed the new enthusiasm, but many criminals have been required to put shaming signs in their cars or to stand in a mall with a sign proclaiming their wrongdoing.

Second, the notorious culture wars in the United States have produced partisan camps eager to shame their opponents. Even liberals, probably hostile to shaming in principle, join the parade, as in the ubiquitous (and so far abortive) efforts to shame our current president and his supporters.

Third, social media have unleashed a torrent of hatred, with fat-shaming and accusations of sexual impropriety, hypocrisy and racism flooding social networks. The efforts can hound victims out of their jobs, force them to relocate — even drive some to suicide.

Shame at a crossroads

These shifts have created a dilemma: Are we shaming enough, or too much?

Some observers, whether they’re concerned about loose sexual behavior or the greed of global capitalists (one of whom proclaimed that “shame is for sissies”), can make a good case for a more robust restoration of community shaming.

It might not mean returning to stocks and dunce caps, but society could do a better job defining what deserves to be shamed, while also setting limits. As American community life has atrophied, this ability seems to have weakened. We certainly seem to have lost the knack — available in more shame-based societies — of helping people recover from shame and become reintegrated into the community.

But what about protecting people against being forced to adhere to an unpleasant level of conformity? What about the cruelty and harshness of social media shaming, in which a misguided comment or mistake can end a career?

Admittedly, the unruly contemporary history of American shame more readily suggests problems than solutions. The country has lost both the comfortable reliance on shame of its colonial ancestors and the confident resistance to it of humanitarian reformers.

Admittedly, the unruly contemporary history of American shame more readily suggests problems than solutions. The country has lost both the comfortable reliance on shame of its colonial ancestors and the confident resistance to it of humanitarian reformers.

Peter Stearns, University Professor of History, Provost Emeritus, George Mason University

Can a long walk heal these veterans from their war demons?

"Almost Sunrise" (Credit: Thoughtful Robot Productions)

This weekend, Americans will celebrate those who have served in our armed forces for Veterans Day. Sacrifices made by veterans come in many forms, but seemingly least known among them is the threat of “moral injury,” a condition that affects over two million people struggling with the ethical ambiguities of war.

Produced by an individual’s conscience and belief that they’ve transgressed their moral compass and beliefs, the psychological trauma comes to stark view in the upcoming film “Almost Sunrise,” premiering on the PBS documentary series “POV.”

In the film, we meet two veterans, Tom Voss, who was deployed to Iraq from 2004-2005, and Anthony Anderson, who completed two tours in Iraq. So transformed by the searing events of war, the two felt compelled to walk 2,700 miles across the country, from their hometown Milwaukee all the way to California, in an attempt to heal themselves.

“I needed to do something to help myself,” Voss says in the film. “I needed to take a stand.” Anderson, still coming to grips with his wartime experience, agrees to join.

Perhaps the most striking about the film is how it exposes the great dearth in psychological support for our returning soldiers. Tom and Anthony have few treatment options when they return from combat; there is simply no established system for helping veterans cope with their moral injuries.

Yet, as much as the film is a solemn and urgent request for greater mental health resources for our returning soldiers, it also paints an inspiring picture of two tireless veterans determined to confront their own demons. Along the way, they meet with various individuals who have therapeutic suggestions on how they can get better.

“Almost Sunrise” airs on PBS Monday, November 13 at 10 p.m. ET (check local listings). You can watch the full film on your local PBS station or online at pov.org/video.

Shaming harassers may stop employers from protecting them

Harvey Weinstein (Credit: AP/Richard Shotwell)

Since the Harvey Weinstein scandal broke, a growing number of workplace harassment victims have decided to go public. Since this used to be pretty rare, it marks an important shift.

Along with the torrent of harassment revelations through the #MeToo Twitter hashtag, employees have gone public with harassment accusations against top figures in journalism, state politics, the restaurant industry and even the labor movement.

Many are wondering if the #MeToo movement will offer lasting benefits for workers affected by harassment. I think it could.

After working as a lawyer defending companies in employment lawsuits and now as a researcher, I gained some insight into how employers make disciplinary decisions after an internal investigation – and why they have a tendency to keep high-ranking harassers on the payroll.

The increased willingness of victims to go public with their accusations, however, may change the way companies feel about protecting a big time harasser.

Employers’ free hand

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act prohibits workplace harassment on the basis of sex, race, national origin and religion.

However, unlike other forms of discrimination, employers are not strictly liable for harassment. Instead, under a Supreme Court doctrine known as the Faragher defense, employers can sometimes escape liability by providing an avenue to complain and taking reasonable measures to prevent or mitigate further harm after an employee complains. The Faragher defense is especially applicable where the employee fails to use that avenue or delays in doing so.

The Faragher defense gives employers a lot of flexibility on handling the harasser after an investigation, as long as they do something, however superficial, to prevent future harassment. Sociologist Lauren Edelman calls this window-dressing “symbolic compliance.” So if a company considers a high-ranking harasser to be a valuable player, punishment may be perfunctory.

A 2000 racial harassment case from the United States Court of Appeals, Tutman v. WBBM-TV, exemplifies this problem. That case involved a CBS producer who told an African-American camera operator named Robert Tutman to “get the f— out of my office before I pop a cap in your ass,” used the n-word with reference to a movie title and “pranc[ed] around, derisively caricaturing African-Americans.”

CBS investigated and gave the producer a written warning, made him attend a workshop and forced him to apologize. Its sole concession to Tutman consisted of an offer to change schedules so he and his harasser would not interact.

The court concluded that CBS was not liable for the producer’s harassment since it investigated and offered a schedule change. Tutman, fearful for his safety, did not return to work. The producer apparently continued to harass others.

This same story plays out in sexual harassment cases.

In Indest v. Freeman Decorating, a sales executive made multiple crude sexual remarks and gestures to a subordinate and reacted angrily when asked to stop. After investigating, the employer gave him a written reprimand and a one-week suspension.

Like Tutman, the victim was offered an assignment that avoided contact with the harasser. And like Tutman, the court dismissed the case, characterizing the employer’s response as “swift” and praising it for “nip[ping] a hostile environment in the bud.”

Actress Rose McGowan recently went public with her allegation that Harvey Weinstein raped her.

AP Photo/Paul Sancya

Why harassers gets favorable treatment

The Faragher defense is not available in all cases. Nevertheless, its application signals that courts are not especially concerned about harasser punishment in assessing an employer’s liability.

This frees employers to consider more prosaic concerns in deciding what to do with the harasser, such as profits and inconvenience. Sure, they could fire a high-flying harasser, but then they’d have to go through the expense, inconvenience and uncertainty of replacing him. Transferring or demoting such an employee is also considered impractical.

In my experience, employers also tend to be excessively worried about potential lawsuits from the harasser, for claims such as breach of contract and defamation. This concern derives less from the legitimacy of such claims – they are for the most part frivolous – but from the strong likelihood that a terminated harasser will hire a lawyer and threaten to sue.

When focusing primarily on the costs of terminating the harasser, the tidiest result is to leave the harasser in place. This may explain why executives felled by the more recent revelations withstood harassment accusations in years past.

Weinstein, for example, settled his way out of myriad harassment claims over several years. NPR vice president Mike Oreskes kept his job following a harassment complaint in 2015. Likewise, Amazon was apparently informed of harassment allegations against Roy Price in 2015 and retained him anyway. Susan Fowler’s harasser at Uber initially kept his job after she complained.

Victims suffer when harassers stay

Typically, employer policies and harassment training urge victims to report harassment. Victims who trust the organization enough to complain then often endure a disruptive investigation only to find their harasser’s position undisturbed. Victims may not even be informed of sanctions imposed on the harasser, since it is often treated as a matter of employee – that is, harasser – privacy.

For the victim, even vindication disappoints because the employer’s loyalty remains divided. The employer may protect you from the harasser, but it also protects the harasser from meaningful consequences.

Retaining high-ranking harassers can also limit a victim’s work opportunities. Good luck moving up in a division led by your harasser. While a victim might prefer a transfer or schedule change over continued dealing with the harasser, it is nevertheless the victim that bears the inconvenience and setback.

Keeping a harasser on the payroll is also shortsighted. Although the employer might protect the complainant from future harassment, it leaves other employees exposed.

How #MeToo might change the calculus

The #MeToo hashtag is remarkable because it could accomplish what the law has failed to do – change the way employers think about punishing harassers.

In a climate where victims speak freely, employers must now expect to publicly defend their employment decisions months or years later.

Any harassment victim is a future #MeToo, a latent public relations nightmare that could irreparably tarnish the brand. And in corporate America, the brand is a much larger asset than even the most powerful employee.

Elizabeth C. Tippett, Associate Professor, School of Law,University of Oregon

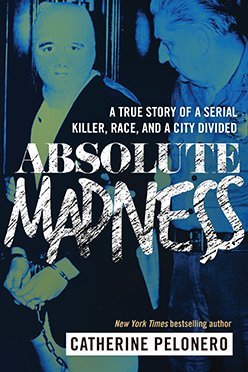

The night the .22-Caliber Killer was born

Joseph Christopher; A chalk line figure drawn by police showing where the body of Ernest Jones was found in Tonawanda, N.Y., Oct. 9, 1980. (Credit: AP/Salon)

MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 22, 1980

The gunshots were so loud, one of the witnesses said later, and so fast, the four cracking pops coming rapidly one after the other, it sounded as if someone were setting off firecrackers on her front lawn. Kids around here sometimes did that, especially around the Fourth of July. But July had come and gone. It was now late September and the nighttime summer shenanigans had ceased, returning the neighborhood to its normal after-dark quiet.

Looking out the window she could see nothing but her own startled reflection, due to the lights inside and the darkness beyond. She took a few quick steps, opened the door, and stepped out on the porch, the light from her home spilling onto the small front lawn. The yard was silent, undisturbed, empty except for the faded lawn ornaments and a fresh Go Buffalo Bills! sign staked in the grass. She saw no pops or flashes of firecrackers, no group of rowdy kids. At first she saw no one at all, until her eyes were drawn to light and movement in the distance.

Looking out the window she could see nothing but her own startled reflection, due to the lights inside and the darkness beyond. She took a few quick steps, opened the door, and stepped out on the porch, the light from her home spilling onto the small front lawn. The yard was silent, undisturbed, empty except for the faded lawn ornaments and a fresh Go Buffalo Bills! sign staked in the grass. She saw no pops or flashes of firecrackers, no group of rowdy kids. At first she saw no one at all, until her eyes were drawn to light and movement in the distance.

The light came from the tall overhead lamps in the parking lot of the Tops grocery store directly across the street from her house, brighter and casting a wider beam than the aging streetlights that lined the block. The movement came from a single person, a slight figure who suddenly darted through an opening in the fence that separated the parking lot from her street, Floss Avenue. The man — she had the impression it was a male — wore a dark hooded jacket. As he emerged from the fence, he ran across Floss Avenue in her direction. Veering to his left, he pulled the hood tighter around his head as he ran up Floss toward East Delavan Avenue, disappearing past darkened houses.

It all happened very quickly.

The witness, whose name was Barbara Wozniak, and who didn’t realize at the time that she was in fact a witness to something of importance, remained at her door for a moment longer, staring in the direction where the man had run. Nothing happened. There was no one around; all was quiet again. Directly south of her home sat Genesee Street, a main thoroughfare that ran all the way from downtown Buffalo through the east side of the city and out to the suburbs. Even Genesee Street seemed unusually still. Then again, it was 10 p.m. or close to it on a Monday night, a school night, and it had been raining on and off for hours. Hardly the kind of weather for strolling or sitting on the porch. The peaceful stillness that had now returned was more typical than the odd popping sounds and the figure running off into the dark.

Barbara assumed he was some kid who had set off firecrackers in the parking lot and she didn’t give it much thought, particularly with the silence that followed. The rising crime rate around the neighborhood had made residents a bit more alert, but this seemed inconsequential. She went back inside, closing her front door against the drizzle and the dark, and returned to watching “Monday Night Football” with her brother.

By the time the sirens shrieked and the news vans arrived, Barbara Wozniak had all but forgotten about the firecrackers, and she didn’t make a connection between the figure in the hoodie and the sudden commotion in the Tops parking lot.

Despite what Barbara Wozniak would eventually tell them about the loudness of the gunshots, police were not finding anyone at the scene who had heard them at all.

The entrance to the Tops grocery store was less than 50 feet from where the Buick Century sedan was parked. Lieutenant William Misztal and patrolman Warren Lewis pulled into the parking lot in car L12E at 9:50 p.m., no more than two or three minutes after hearing the call from dispatch. Lieutenant Misztal and Officer Lewis were assigned to precinct 12. The shooting had occurred within the boundaries of the neighboring sixteenth precinct, but Misztal and Lewis had responded because of both the serious nature of the call and the location in particular. This Tops market regularly employed off-duty police officers as security guards. Misztal’s first thought was that this must be an officer-involved shooting; either a police officer had shot someone or been shot himself.

Alvin Pustulka was waiting in the parking lot and waved the blue and white police cruiser over to where the Buick Century was parked, by the fence that divided the lot from residential Floss Avenue. Pustulka was a police officer out of a precinct in South Buffalo but worked security at this Tops on the east side of the city as a second-front job. As Pustulka explained to Lieutenant Misztal, he had not been involved in the shooting, nor had he witnessed it. A young man had run into the store and told him that someone had been shot outside.

Despite having been just inside the store entrance, Al Pustulka had not heard any gunshots or anything else out of the ordinary before the young man had rushed in to tell him of the shooting. He had seen this same young man exit the store only a minute before and had therefore been a little suspicious, wondering at first if this was some sort of a ruse to get him outside. Pustulka had followed the young man to the green Buick Century where he observed the victim, another young male, sitting in the driver’s seat. Seeing that the young man in the Buick had indeed been shot, Pustulka had rushed into the store and told the manager to call 911 before returning to the lot to stand watch over the victim, who was unresponsive.

Peering inside the Buick, Lieutenant Misztal noted that the young man had been shot at least once in the left side of his face. The blood had thickened already, but the victim, eyes open wide and pupils dilated, was still trying to breathe.

Misztal radioed for an ambulance and a tow truck, and told dispatch to notify Homicide and the Evidence Unit.

Detective John Regan arrived within minutes of the call and noted right away that the Buick looked brand new, a 1980 or possibly even one of the first 1981 models, fresh off an assembly line in Detroit. Even in the dark, the exterior looked sleek, unblemished, and the interior was pristine, except for the fresh heavy bloodstains that soaked the upper portion of the driver’s seat and headrest.

The driver’s window was open, as it must have been when the shooting occurred. There was no broken glass anywhere. There were, however, some shell casings: one on the ground, one on the driver’s side floor, and one on the rear seat of the Buick. To Detective Regan they looked like shells from a .22 caliber firearm of some kind. No weapon was present. It seemed that the shell casings were all that had been left behind from the shooting, aside from the bloody Buick Century and of course the victim, an unconscious black male with multiple gunshot wounds to the head.

This was not the scenario John Regan had expected. Regan and his partner, Detective Melvin Lobbett, had just settled down in front of the TV set at the thirteenth precinct, eating a late dinner of submarine sandwiches and watching “Monday Night Football,” when the call came of a man shot in the Tops parking lot at 2094 Genesee Street.

Details from the radio call had been sparse. Male in vehicle with gunshot wound to the head. No mention of an arrest. Regan had figured it was a suicide. The organized gang violence that exploded on urban streets in the 1980s and ’90s had not yet come. In 1980, it made sense to assume a lone male found shot in a car likely meant a suicide, more so now perhaps than ever before, given Buffalo’s dire and ever worsening economic crisis. Another depressed guy, out of work and out of hope. It wasn’t uncommon for suicides to happen this way, lives taken in parked cars or motel rooms to spare family members from finding the body.

After arriving at the scene, however, Regan immediately realized that this was not a despondent soul who had decided to end it all. Someone else had made that decision. Multiple bullets had struck him in the face and head. Fired at close range. Intended to kill.

Whoever the shooter was and whatever had led up to the murder, the fact he hadn’t bothered to pick up his shell casings was a plus for investigators. The task now for detectives John Regan and Melvin Lobbett was to find out exactly what had happened. From the start, getting any useful information proved a challenge.

The people closest to it all, the ones inside the Tops market — and eventually, in desperation, police would track down every soul who had been there that night — had heard nothing at all. Despite the proximity, not a single employee or patron had been aware of what was happening outside, least of all Larry Robinson, the young man who had alerted Officer Pustulka. Robinson now sat shaking in the drizzly night air, speaking as calmly as he could with police.

“I don’t know what happened,” Larry said, looking at the official faces standing above him. John Regan noted how Robinson rubbed his forehead, as if he were trying to rub out what he had seen in the Buick. Who could blame him? To Detective Regan’s veteran eye, there was no evasiveness here, no disingenuous performance; Larry Robinson was genuinely shaken to the core.

“I don’t know what happened. He was fine. We were talking. I went inside the store . . .” Larry paused. He seemed to be trying to make sense of it himself. “I don’t know what happened,” he repeated. “I didn’t even know anything was wrong until I saw the blood . . .”

An hour earlier, Larry Robinson had been on his way here, the Tops market on Genesee Street. Larry was 24 years old. He lived nearby. He had been walking near the intersection of Genesee and Fillmore when he saw Glenn drive by in the Buick. Larry had waved and Glenn had pulled over and offered him a ride. Glenn agreed to take him to Tops, where Larry planned to withdraw some money at the store’s service counter.

Glenn, the young man whose heart paramedics were now furiously trying to restart, was only an acquaintance, Larry told police. Just a guy from the neighborhood. How old is he? Larry didn’t know. Where was he coming from? Larry didn’t know that either. Like he kept telling them, Glenn was just someone he knew from the block, one of those guys who’s always just around. They didn’t travel in the same circles nor did they have the same friends, but you get to know people’s names and faces when they live in your neighborhood. Where Glenn lived was about the only solid detail Larry could offer. He gave them an address and added that he thought Glenn lived with his parents. An officer was dispatched to the home.

Glenn Dunn did indeed live with his parents. Glenn was only 14 years old. He had just begun his freshman year at nearby Kensington High School.

Larry Robinson meanwhile explained to Detective Regan and colleagues that he had only accepted the ride from Glenn because of the car. It was really sharp looking, roomy and plush, and it had that unmistakable new-car smell, a scent Larry didn’t come across very often. He didn’t know many people who had new cars, much less a $10,000 Buick.

That was easy enough for police to believe. Expensive new cars were generally not found in driveways over here on Buffalo’s east side. Crumbling houses and overcrowded flats, yes. Poverty, unemployment, and deprivation, sure. The east side had plenty of all that.

It hadn’t always been this way, of course. In fact, it had been anything but this way. Within living memory of many of its dwindling residents, Buffalo had been the picture of urban American prosperity, known for its robust industry, splendid architecture, and forward-thinking innovations. Buffalo had entered the 20th century as the eighth largest city in the United States with a short but impressive legacy. Proximity to Canada — coupled with widespread antislavery sentiment among the populace — had allowed the city to play a notable role in the Underground Railroad, aiding the escape of fugitive slaves in defiance of federal law. (An article in the New York Times on September 8, 1855, criticized Buffalonians for their open and stubborn refusal to cooperate with the Fugitive Slave Act.) Presidents Grover Cleveland and Millard Fillmore had both lived in Buffalo, as had authors Mark Twain and F. Scott Fitzgerald.

The city’s key waterways had made it a prime location for industrial development, generating employment for many and great wealth for some. Frederick Law Olmsted had developed the city’s picturesque park system while major buildings and illustrious mansions had been designed by the foremost architects of the time, with no expense or luxury spared. Early in the century, Buffalo had the most widespread use of electrical lighting in the nation, courtesy of hydroelectric power from Niagara Falls, and at one point boasted more paved roads than New York City.

* * *

The opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1959 rendered Buffalo’s industrial waterways obsolete, landing the first major blow in what proved to be an intense downward economic spiral. Industries closed or downsized in rapid succession over the next two decades, disfiguring the Queen City of the Great Lakes into a pitiful picture of the American rust belt. Perhaps even more remarkable than the change itself had been how fast things had gone to hell.

John Regan had grown up in the city’s First Ward, a solidly Irish working-class neighborhood south of downtown. Regan was 38 years old and had been a detective since 1971. He had entered the Buffalo Police Academy in 1962, mainly because he needed a job and had no interest in college or a trade. Now he thanked God he’d chosen a profession in which he didn’t have to worry about his employer shutting down or moving out of state. Many of his boyhood friends had not been so lucky. As a result, there were fewer and fewer of them around.

The 1970s had been the worst. The city had lost almost a quarter of its population in that ten-year span, mostly middle-class people leaving for opportunities in other states or fleeing to suburbs to escape the decay and rising crime in the city, not to mention the oppressive dark mood. There were actually billboards that read, Will the last person to leave Buffalo please turn off the lights?

In truth, the decline could be traced not to the evaporation of a single industry but to a variety of shifting technologies and calamitous policy decisions, the combination of which had effectively stripped Western New York of both its economy and charm. Olmsted parks had been carved through with expressways. Neighborhoods of single-family homes had been bulldozed to make way for high-rise public housing projects. Skyrocketing taxes — the highest in the nation — were the icing on the lousy cake. Buffalo thus began the 1980s with a population of 357,870, a good portion of whom were living below the poverty line and a great many of whom were living with constant uncertainty and fear.

The east side, where Detective John Regan and his colleagues now found themselves working not a suicide but a crime scene, had perhaps been hit harder by the downturn than anywhere else. The changes here had been especially dramatic, both economically and demographically.

The east side had one of the highest crime rates in the city, although this particular area, the easternmost point near the city line, was not among the most stricken. It was, however, undergoing a major racial transition.

Up until a dozen years ago, the neighborhood had been largely populated by families with working-class Italian roots, surrounded by larger sections of residents with German and Polish ancestry. Though never a high-end part of town, it had been comfortable and safe, at least for residents who looked and lived like their neighbors, which was pretty much everybody. Things were changing, though.

As the city’s African American population grew — and as civil rights legislation had legally broken the boundaries of where they were permitted to live — black families had gradually begun moving from “their own” section of the lower east side (the area where blacks had traditionally lived since the 1800s) into adjoining communities. Throughout the 1970s, more and more black families had moved into homes vacated by whites.

There still were, of course, white residents to be found here, many of them from older generations who stubbornly resisted the efforts of their children or grandchildren to relocate them to suburbs like Amherst or Kenmore. They proudly declared that they had lived here for decades, refusing to move while at the same time lamenting the demise of the neighborhood, wistfully recalling how “it used to be so nice over here . . .”

The victim in this shooting fit the profile of both the typical resident and typical victim of crime on the east side. Glenn Dunn was black, as was his traveling companion, Larry Robinson.

According to Larry there had been nothing remarkable about the ride he and Glenn had taken that night in the Buick. Not until Glenn revealed to him that the car was stolen.

They had been riding around for a while, just enjoying a leisurely cruise, when Glenn hit him with this news. He hadn’t given Larry any details about the car theft, and Larry hadn’t asked for any. He didn’t want to know. It was after learning this that Larry asked Glenn to stop at the store, as he had intended to do all along. He was already in the hot car now. Might as well get the errand done and then have Glenn drop him off at home. They pulled up in front of the store and Larry hopped out. Glenn promised to wait for him.

No more than 10 or 15 minutes had passed before Larry exited the store. He didn’t see Glenn or the Buick at first, but looking around he spotted the car parked by the fence. Larry called Glenn’s name as he walked toward the car. Glenn did not respond. Larry approached the driver’s side, where Glenn was sitting behind the wheel. He called to him again, louder this time, but Glenn only moaned.

Glenn was sitting very still, staring straight ahead at the windshield. Larry reached in, nudged his shoulder. Glenn’s head tipped to the right and Larry saw what looked like blood. He also noticed a hole in the side of Glenn’s head.

Larry ran back to the store and alerted the police officer.

That was all he knew.

Stolen car. Bingo, thought John Regan.

There were a few auto-theft rings operating on the east side. Glenn Dunn must have been involved. And gotten on somebody’s bad side.

But still, something didn’t fit. Regan had never known the car-theft rings to exact this kind of revenge, an execution-style hit. And if they were going to deal with an errant member that way, it didn’t seem likely they’d kill him in one of the cars, if for no other reason than it ruined the inventory.

Had Glenn Dunn been an informant, killed for working with the cops on the side? A quick call to the robbery division could answer that, and did. No one in robbery had ever heard of Glenn Dunn. It looked like the Buick Century was his first stolen car. And quite likely his last, considering the severity of the bullet wounds.

As detectives were listening to Larry Robinson give his account of his last ride with Glenn Dunn, a woman named Madona Gorney sat in her idling car. Her groceries were in the trunk; she was ready to drive home. But she hesitated, staring at the flashing lights through her rain-streaked front windshield. She wanted to talk to the police. The store manager had fluffed off her inquiries and told her not to bother the officers. Still, something made her feel that she should. She didn’t know exactly what was going on but thought maybe she should tell them about the black man she saw standing under the lamppost when she had pulled into Tops. She didn’t see him now. And that car that the police were gathered around; it hadn’t been there when she pulled in. Madona also recalled the odd man who had been sitting outside the store entrance when she went in, the young white guy wearing glasses and a blue jacket, with a paper bag by his feet and such a dazed look on his face. He had not looked well to her, not at all.

The ambulance carrying Glenn Dunn had already departed for the hospital and John Regan was preparing to follow when Lieutenant Misztal brought a young man over to speak with him. He was a slender white kid with a mop of dark brown hair. He said his name was Kenny Paulson. He was 17 years old and lived a few houses down on Floss. He said he had been in the parking lot, coming out of the store, you know, when he saw a man walk up to that car, the one the police now had cordoned off, and shoot the driver.

Kenny Paulson described it for him. The guy who got shot, the black guy, was standing next to his car smoking a cigarette when Kenny first saw him. He tossed the cigarette and got in the driver’s seat. About a minute later another guy, a white guy, walked up and shot him through the open window, then ran away.

He hadn’t heard any arguing. He hadn’t heard either of them say anything, in fact. The white guy just walked up, shot the guy in the car, and left. Kenny had been close enough to see the fireballs bursting from the barrel of the gun.

After the shooter took off there was no one else around — except for the guy in the car, of course, who didn’t move or make any sound that he could hear. Scared, Kenny immediately ran home. Shortly after, though, he thought he’d better come back and tell the police what he had seen.

Detective Regan thanked him for coming back. He could understand why the kid’s first instinct was to run home. It must have been a pretty shocking sight, especially for a teenager.

Regan had him tell the story again. Kenny Paulson had no idea what kind of a gun it was, but he described the shots as four quick, loud blasts.

Once again, he described the yellow flash of fire from the barrel, the way the shooter had walked up to the car, and the direction that he ran.

When it came to describing the shooter himself though, beyond saying he was a white guy, Kenny could not be at all specific. He was quite vague, in fact, not even willing to commit to whether the man was short or tall, thin or heavyset. He couldn’t remember what the guy was wearing. He wasn’t sure what color his hair may have been. He just didn’t have any descriptive details for them at all. He even seemed sketchy on whether the shooter was indeed white.

At the time, Regan had no reason to believe Kenny was lying.

How to survive an all-nighter

(Credit: Salon/Ilana Lidagoster)

When a recent study carried out by researchers at the University of Rochester Medical Center in New York showed how the brain uses sleep to flush the cerebrospinal fluid present in the extracellular space and rid itself of toxic molecules, it raised the debate again about the importance of sleep in our lives.

This is more of an academic question. As technology drives connectivity and shrinks the traditional differences between night and day, more and more of us find that we have to work across time zones and through the night in order to make crucial deadlines.

Companies that outsource workers, rely on staff to put in extra time or have a far-flung, international network of peers find themselves debating the wisdom of the proverbial “sleep is for the weak” slogan. At stake is nothing less than their survival.

The argument goes that if sleep is a critically important component of high-level brain function then companies whose staff is sleep-deprived are laboring under a competitive disadvantage. Sleep-starved employees make suboptimal decisions that result in an accumulation of errors. Let a sufficient number of errors accumulate in your day-to-day operations, and very soon they begin to weigh against you. Critical deadlines are missed, contracts are cancelled, fresh opportunities are not seen quickly enough and even threats to the business are not noticed until it is too late.

Any business can survive only so much damage before its brand is tarnished, its reputation is dented, trust evaporates and it finds itself with demoralized, tired staff, a shrinking market share and in urgent need of restructuring.

Yet despite the growing body of evidence that points toward the many cognitive and health benefits of sleep, the reality of daily working life and the ever-expanding awake cycle are pointing the other way. Our modern lifestyle is unlikely to change toward any kind of normative day/night cycle. Our pace of life is not going to suddenly decelerate and we are not ever likely to unplug from each other and the internet just because the sun has gone down.

So clearly we must do something that takes into account everything we know about sleep and sleeplessness and work out a solution that allows us to toil through the night without impairing our physical or cognitive capabilities. The answer to our predicament comes from the most unlikely quarter: snipers and elite Special Forces. These are combatants whose mental and physical skills have been honed to a fine edge and yet which have to go through the seemingly blunting process of sleepless days and nights and still perform at peak when called upon. How do they succeed without losing their vital edge?

Studies have shown that a sleepless night elevates the dopamine levels in the brain, leading to a heightened sense of euphoria. But, at the same time, sleep deprivation shuts down the brain’s key planning and decision-making regions (the prefrontal cortex) while activating more primal neural functions such as the fight-or-flight reflex in the amygdala region of the brain.

It may sound like it’s impossible to go through an all-nighter and still function adequately the next day, but it actually isn’t. Vietnam marine sniper Carlos Hathcock did it in a now legendary three-day crawl to successfully complete his mission. Elite soldiers who go through Survival, Evasion, Resistance, Escape (SERE) training have to learn how to manage extreme sleep deprivation.

So when you have no choice, here are four things you can do that will temporarily allow you to brush off the debilitating effects of sleep deprivation and function well.

1. Stock up your sleep reserves

It may not always be possible to plan this step, but sleeping enough the nights that lead up to a sleepless night makes it easier to pull off an all-nighter because your brain has that extra capacity to absorb the stress it undergoes.

In a pinch, sleep experts suggest grabbing what they call a “prophylactic nap.” At the Dayton VA Medical Center, researchers associated with Wright State University have carried out studies to determine the best protocol for weathering a sleepless night without suffering ill effects in terms of performance. In a study titled “The use of prophylactic naps and caffeine to maintain performance during a continuous operation” they detailed how their group of 24 young adult males, when put through a sleepless 24-hour period where their mental alertness and performance was monitored against baseline readings and a control group, managed to maintain near-optimum efficiency through a regime of strategic napping and caffeine intake.

The power-nap-and-a-strong-espresso strategy was found to be most effective when the nap was no more than 90 minutes long and the coffee intake was spaced out to help boost alertness when the effects of the nap were beginning to wane. Sara Mednick, an assistant professor at the University of California, Riverside, who’s been studying the ability of naps to restore the brain to near-normal baseline performance, cites how her studies show that napping produces the same sleep-stage-specific enhancements as an overnight sleep.

2. Have a stimulant ready

Wars may be won by bravery and they may require weaponry, but they run on coffee. There is no nine-to-five in battle. And, just like when a crisis hits in a business environment, when things break on the battlefield all hands are called to the task irrespective of the time of day or the kind of week they may have had. Snipers report having a strategic relationship with coffee. “If you need to stay up all night and are on lookout, you need to have coffee on hand. But that also means you can’t go on drinking coffee all day, every day, like water. Keep it in reserve. Come off it if you need a day before your all-nighter. Then it will work best for you,” says Mark, a sniper.

3. Stay off the carbs

If you’re preparing for an all-nighter and want your brain to function at peak then you should know that a large, carb-heavy meal will most probably lead to a crash as its “good mood” feeling kicks in. Snipers know that you need to fuel up for combat operations, so they pile in some calories to keep them going — but they avoid anything that’s really carb-rich.

4. Stay active

Snipers on duty have an active lifestyle as part of their everyday work. They constantly have to work on their fitness so they do not have to specifically schedule physical activity before they go on a mission. It’s not quite the same for the rest of us, who sit behind desks looking at screens all day, drive everywhere and try to fit in exercise once or twice a week. Here’s some advice from Mark, who is with the 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit: “Try to get some exercise in before an all-nighter — nothing that would exhaust you, so stay away from all the heavy stuff, but a workout that makes you sweat a bit and lights up your brain makes you feel energized and ready for anything. Plus, when you are actually pulling an all-nighter, try to be active. Do a few push-ups or stand up and walk about. All of this stimulates the body and keeps the mind alert.”

So next time you have the prospect of an all-nighter staring you in the face, you’ll be ready to tackle it like a seasoned warrior, shaking off its ill effects and retaining your edge.