Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 222

December 2, 2017

The long, sudden metamorphosis of Radiohead

(Credit: AP/Bloomsbury Publishing/Salon)

Reaching the point where Thom could freely experiment with his voice wasn’t easy. At the time, the band members had been playing music with each other for 15 years (and had known each other for roughly 20), finally garnering enough cultural and financial clout to boast leverage within a conservative major label system. This was no small feat for a band only three albums deep into its career. Imposing neither pressure nor a deadline, EMI — the music group that owns Radiohead’s then record labels Parlophone and Capitol — granted Radiohead one of the rarest luxuries: artistic autonomy bankrolled by a major conglomerate.

It was interesting, then, how tentative everything was. Explained Ed in an interview with Spin,

Musically, I think we all came to it a bit vague. Thom didn’t know exactly what he wanted the new record to be either, but he did know what he didn’t want it to be, which was anything that smacked of the old route, or of being a rock’n’roll band. He’s got a low boredom threshold and is very good at giving us a kick up the ass.

Clearly, Radiohead were neither interested in recycling “OK Computer’s” winning formula nor in hitting the stage of Celebratory Rock Theater. Responding to Ed’s original idea of regressing their songs into three-minute “snappy” pop tunes, Thom told Q, “F**king hell, there was no chance of the album sounding like that. I’d completely had it with melody. I just wanted rhythm. All melodies to me were pure embarrassment.” If “Kid A” was going to be anything at all, it certainly wasn’t going to be “rock.” At one point, Thom even entertained the idea of changing the band’s name in order to demarcate an aesthetic break from their first three albums.

But contrary to popular opinion, Radiohead weren’t out to alienate fans. With fame comes imitation, and Radiohead had a hard time dealing with the many bands — Travis, Coldplay, Muse — lifting their aesthetic like free weights (and leaving the politics alone, of course). “[There] were lots of similar bands coming out at the time, and that made it even worse,” said Thom to The Wire. “I couldn’t stand the sound of me even more.” And the similarities didn’t go unspoken: While some felt guilty about it (“When we won best band at the Brit Awards, the first thing I did was apologize to Ed O’Brien,” said Coldplay’s Chris Martin), others couldn’t even tell the difference (“I think [Radiohead] sound like Muse,” quoth Weezer’s Rivers Cuomo). Björk, who around that time collaborated with Thom on the track “I’ve Seen It All” for director Lars von Trier’s “Dancer in the Dark,” spoke about this artistic appropriation on her website:

What really really hurts and I know I am speaking for a lot of people here, video directors, musicians, photographers and so on, is when a lifetime of work gets copied in 5 minutes with absolutely no guilt. That expression, ‘imitation is the sincerest form of flattery’ — it might be true, but it is the kind of flattery that robs you. I spoke quite a lot about this with Thom from Radiohead [a] couple of years ago, when every other singer on the radio was trying to be him, and he said it really confused him. After hearing all that, next time he stood by the [mic], he didn’t know anymore what was him and what was all those copycats. It is one of the reasons “Kid A” was so hard to make.

“Kid A,” then, could be seen as Radiohead’s opportunity to construct a new identity, to pacify a desire for change because stasis would’ve meant tailspinning into the same predictable cycles; it would’ve meant going through the motions; it would’ve meant accepting the mythology. “There was no sense of ‘We must progress’,” said Thom. “It was more like, ‘We have no connection with what we’ve done before.’” As bassist Colin Greenwood put it, “[We] felt we had to change everything. There were other guitar bands out there trying to do similar things. We had to move on.”

But if distancing themselves from their previous aesthetic was the mission, where would they go and how would they get there?

Despite the uncertainty in direction, Radiohead realized that aesthetic renewal would necessitate a renewed approach. “If you’re going to make a different-sounding record, you have to change the methodology,” said Ed. “And it’s scary — everyone feels insecure. I’m a guitarist and suddenly it’s like, well, there are no guitars on this track, or no drums.” Influenced in part by German Krautrock group Can’s approach to songwriting, Thom’s desire was to shape half-formed ideas — sometimes just a beat or an interesting sound — into songs. He wanted to stumble upon sonics rather than force them into existence. “When we started doing the recording properly, I bought a new notebook and put at the front, ‘Hoping for happy accidents,’ and that’s basically what we were trying to do.” And since Thom — at that point completely enamored with electronic artists like Aphex Twin and Autechre — wouldn’t be satisfied with “rock music,” the recording process was made even tougher. Said Godrich to Spin: “Thom really wanted to try and do everything different, and that was . . . bloody difficult.” “There was a lot of arguing,” he said to the New Yorker. “People stopped talking to one another. ‘Insanity’ is the word.”

After several failed attempts, the band eventually got fully behind Thom’s quest for “happy accidents,” and in addition to his own contributions, the floodgates opened wide for the other members: Rather than wielding his ax, Jonny was primarily arranging strings and playing the Ondes Martenot; Ed and drummer Phil Selway could be found creating sounds on keyboards and sequencers rather than on guitar or drums; and instead of simply playing bass, Colin “drunkenly played other people’s records over the top of what [they] were recording and said ‘it should sound like that’” (it’s Thom, not Colin, playing fuzz-bass on “The National Anthem”). It was all a bit scattershot: many tracks were written entirely in the studio, some were tried and just as quickly ditched, and still others didn’t even feature every member. At one point, Godrich (often dubbed Radiohead’s “sixth” member) split the band into two groups to create music separately, not allowing them to play acoustic instruments like drums or guitar. At another point, they considered using no guitars at all. “We had to unlearn, get out of the routine,” said Godrich.

The recording sessions resulted in roughly 30 completed songs, which Radiohead had the unenviable task of whittling down to a proper album length. After drafting more than 20 different track listings, any song that ultimately didn’t fit the continuity and flow from opening track “Everything in Its Right Place” was left off, most of which were released the following year on “Amnesiac” (though, even that album’s second track, “Pyramid Song,” was in the running for “Kid A” as late as the early summer of 2000). After several arguments and debates, Radiohead eventually agreed on a firm ten tracks that would make up “Kid A.”

How do I help my preschooler to discern fact from fiction?

(Credit: Screengrab via YouTube)

Little kids love playing make-believe. And there’s no reason to harsh their mellow. But there comes a time when you have to explain the difference between fact and fiction. Maybe an older sibling put a scary notion in their head. Maybe they’re trying to get away with a fib. Or maybe they caught wind of a tragedy in the news and you have to explain that it won’t hurt them. For some kids, fantasy-reality confusion can lead to nighttime fears and anxiety.

Keep in mind that small children are at a stage in their development that’s very concrete. They haven’t yet developed the ability to think in abstract terms, and they’re not super secure about the difference between fantasy and reality. Use visual examples of the ideas you’re trying to teach — and back off if you sense they’re not quite ready to give up their pretend world quite yet.

Start with what they know. Use ideas that they know are pretend, such as monsters or other fantastical creatures. Talk about how those things aren’t really real — they’re just ideas we’ve made up in our heads.

Relate their media to the real world. When a character does something realistic or a scene is realistic, make the connection for kids: “That’s how it would happen in real life.”

Compare and contrast. Use items that they’re familiar with, such as toy or food packaging, and ask kids to explain the similarities and differences between what’s inside and what’s pictured on the outside.

Talk about the differences between media and reality. When you’re reading together or watching TV, ask what would happen if someone really did what’s in the book or on the show.

Trump says he knew Michael Flynn lied to FBI when he fired him

(Credit: Getty/Drew Angerer/Salon)

In a tweet posted on Saturday afternoon President Donald Trump seemed to assert he fired his former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn because he knew he had lied to the FBI and Vice President Mike Pence.

“I had to fire General Flynn because he lied to the Vice President and the FBI. He has pled guilty to those lies. It is a shame because his actions during the transition were lawful. There was nothing to hide!” Trump tweeted.

I had to fire General Flynn because he lied to the Vice President and the FBI. He has pled guilty to those lies. It is a shame because his actions during the transition were lawful. There was nothing to hide!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) December 2, 2017

On Friday morning Flynn was charged, and then pleaded guilty to, “willfully and knowingly” making “materially false, fictitious, and fraudulent statements” to federal agents about his conversations with Russian ambassador Sergey Kislyak in late December 2016 during the presidential transition period.

For the most part the president has been quiet since the Flynn news broke but his tweet marks a startling admission, even for Trump family standards, and many have said it will only add to special counsel Robert Mueller’s case for obstruction of justice.

The public was told that Flynn had originally resigned in February because he lied to Pence about his conversations with Kislyak, but Trump has never previously mentioned he potentially knew anything Flynn told the FBI.

In the same month Trump met with then-FBI Director James Comey, and a memo written by Comey later revealed the president asked him to drop the investigation into Flynn. “I hope you can see your way clear to letting this go, to letting Flynn go,” Trump said, according to Comey’s memo.

Trump’s tweet clearly raises questions about if he knew Flynn had already lied to the FBI, which is exactly what his tweet asserted. Many journalists, legal experts and even lawmakers quickly pointed out that it only builds on Mueller’s ongoing investigation and his case for obstruction of justice.

Oh my god, he just admitted to obstruction of justice. If Trump knew Flynn lied to the FBI when he asked Comey to let it go, then there is your case. https://t.co/c6Wtd0TfzW — Matthew Miller (@matthewamiller) December 2, 2017

The time sequence as Trump now reports it CONFESSES that he KNEW Flynn had committed a major federal felony BEFORE firing Comey for refusing to let that criminal (Flynn) escape justice. That’s a confession of deliberate, corrupt obstruction of justice by @POTUS. QED! https://t.co/tSnnDho81q

— Laurence Tribe (@tribelaw) December 2, 2017

Trump’s claim today that he fired Flynn because of lies to FBI, as well as Pence, shows knowledge of lawbreaking he concealed – never before disclosed. — Richard Blumenthal (@SenBlumenthal) December 2, 2017

If that is true, Mr. President, why did you wait so long to fire Flynn? Why did you fail to act until his lies were publicly exposed? And why did you pressure Director Comey to “let this go?” https://t.co/Ea4kOBpWPv

— Adam Schiff (@RepAdamSchiff) December 2, 2017

…just couldn’t resist commenting on Flynn. Are you ADMITTING you knew Flynn had lied to the FBI when you asked Comey to back off Flynn??????????????????????????????????????????? https://t.co/HJWlUvC99F — Walter Shaub (@waltshaub) December 2, 2017

Feeling jealous during the holidays? That can be a good thing

(Credit: Getty/DNY59)

Ostentatious gifts and over-the-top celebrations can inspire distinctly unseasonal feelings of resentment, jealousy and envy during the holiday season.

If these feelings make some of us feel decidedly Grinch-like, then at least we can take some comfort from the fact that we are genetically hard-wired to respond this way. And if the role they played in hunter-gatherer societies is anything to go by, then socially corrosive traits like envy and jealousy were instrumental in molding the strong, highly cooperative communities that ultimately enabled our species’ extraordinary evolutionary success.

Evolutionary psychologists agree that traits that have run the mill of natural selection must ultimately be advantageous, or at the very least, benign. Unsurprisingly, they struggle to reconcile our more altruistic social virtues like generosity with our more selfish traits like envy, jealousy and greed.

The evolutionary benefits of our selfish traits at an individual level are obvious. They form part of a jigsaw of behavioral adaptations that energize individuals in the competition for resources and sexual partners, so enhancing our chances of finding a quality mate and successfully passing on our genes. We see this play out among other species all the time.

But Homo sapiens’ evolutionary success was a group effort. Our species would not be anywhere near as dominant as it is today had our ancestors spent all their energy strutting and fighting like stags in rut or if they cheerfully stole food from their neighbors’ plates the minute their backs were turned. Homo sapiens’ ascendance came about because we discovered how to bind ourselves to one another by forming successful co-operative groups and occasionally even “taking a hit for the team.” We all know from bitter experience that the short-term benefits of acting explicitly in one’s self-interest are almost always outweighed by the longer-term social costs of doing so.

Proponents of the famous “selfish gene” hypothesis take the view that that there is no such thing as altruism and that all apparently altruistic behaviors are at least indirectly self-interested. Other evolutionary psychologists like E.O Wilson suggest that we are simultaneously driven by selfish instincts to ensure the reproduction of our own genes and social instincts to support and protect broader groups that we identify with. The fact that these imperatives are sometimes at odds with each other, he argues, gives rise to the eternal inner conflict that is the “human condition” — itself one of the greatest spurs to ingenuity, artistry and ambition.

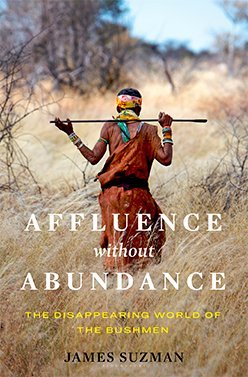

But there may be a simpler way to account for the endurance of these two contradictory evolutionary traits. We now know that our species has been around for at least 200,000 years, and that for 95 percent of that time we were hunter-gatherers, and almost certainly as socially capable and thoughtful as we are now. This means that we can infer how our prehistoric ancestors lived from anthropological studies of communities like the Ju/’hoansi Bushmen of the Kalahari, who continued to hunt and gather through much of the 20th century and whose encounter with modernity I have been documenting for the past 25 years.

Ju/’hoansi in the Kalahari occasionally have white Christmases too. In years when the November “little rain season” does not come, hot dry winds pick up the fine Kalahari sands and paint every tree, bush and shrub in a ghostly shade of white. This is the toughest time of year in the Kalahari. Temperatures soar upward of 100 degrees, forcing even the best heat-adapted animals to seek refuge under thinning trees while waiting for the “big rains,” which usually come in late January.

Yet even in this apparently bleak environment, the Ju/’hoansi hunter-gatherers were able to enjoy a form of affluence at this time of year, albeit one that is very different from that which we enjoy in our tinsel-decorated homes at Christmas.

Ju/’hoansi were once famous for turning established views of social evolution on their head. The first rigorous research into their economic behavior revealed that far from enduring a constant struggle to survive in this harsh environment, they were well-nourished, and healthy adults only worked around 15-17 hours per week. It was as a result of this that Marshall Sahlins, arguably the most influential American anthropologist of the last century, famously redubbed hunter-gatherers “the original affluent society.”

This research also revealed that Ju/’hoansi were able to do this because they were, in the words of the anthropologist Richard Lee, “fiercely egalitarian”: They had no formalized leadership institutions or governance structures, afforded no individuals any special status and were intolerant of show-offs. Consequently, no one bothered accumulating wealth or power, resources were shared and disputes over status never interfered with the general harmony of day-to-day life.

And there is no question that this system worked. The Ju/’hoansi’s ancestors hunted and gathered continuously in southern Africa for at least 150,000 years without enduring the kinds of catastrophic population bottlenecks as a result of famine, disease or war that shaped human history elsewhere. If we measure a civilization’s success by its endurance over time, this makes them the most enduring civilization in human history by a considerable margin.

But in a society with no formalized leaders, how did they enforce this egalitarianism?

The Ju/’hoansi are unequivocal in their answer to this question. Their egalitarianism was maintained not in spite of self-interest, but because of it.

This was best demonstrated by their treatment of good hunters. They were never praised for their successes, even if meat was by far the most valued of foods and even if the hunter had made a particularly spectacular kill. Instead, those due to share in the meat would mock the hunter’s skill and insult the meat he returned with, claiming it was rotten or old or foul tasting or insufficient.

For his part, the hunter was expected to be humble and self-deprecating whenever he presented a kill, even if it was something as magnificent as a giraffe.

During the 1960s, a Ju/’hoan man provided the anthropologist Richard B Lee with a particularly eloquent explanation of why they did this.

“When a young man kills much meat he comes to think of himself as a chief or a big man and he thinks of the rest of us as his servants or inferiors,” the man explained to Lee, “ we can’t accept this. . . . So we always speak of his meat as worthless. This way we cool his heart and make him gentle.”

This behavior was not limited to hunters. Similar insults and mockery were meted out to anyone who got too big for their leather sandals or encountered a sudden material windfall. Everyone in Ju/’hoan bands jealously scrutinized everybody else all the time. They took careful note of what others ate, what they owned, and most crucially of all, whether they had received a fair share.

And what in turn motivated them to “gentle” others in this way? Ju/’hoansi are unequivocal about this, too. Because whenever they imagine that someone had claimed more than their fair share or exercised too much influence, they became consumed by the negative emotions we associate with “envy” and “jealousy.”

The net result of this is that while Ju/’hoansi were as upset as we all are by the negative emotions we associate with traits like envy, they did not view them as negative traits. After all, if it wasn’t for traits like envy, then people wouldn’t share whatever they had or conduct themselves with the humility, self-awareness and empathy that binds us into strong, loyal and enduring communities.

Traits like envy were the “invisible hand” of the Ju/’hoan social economy. Yet it exerted its influence differently from the “invisible hand” famously imagined by Adam Smith in “The Wealth of Nations” that is invoked with such solemnity by the fiercest libertarians. For Smith, man “intends only his own gain,” but in doing so he is guided by an invisible hand “to promote an end which was no part of his intention.” And this end, according to Smith, is to “promote the interests of society” more effectively than “man” could, even if he had intended to. Smith believed that trade and enterprise in pursuit of personal enrichment and unburdened by regulatory interference ensured the fairest and most effective “distribution of the necessaries of life” and so advanced “the interests of society.”

Being a socially minded fellow, Adam Smith would be among the first to acknowledge that the contemporary economic world is a very different creature to the simple “merchants and mongers” he had in mind when he mused on the unintended benefits of self-interested commerce.

But ironically, even though Smith’s hidden hand does not apply particularly well to late capitalism, his belief that the sum of individual self-interests might enable the equitable “distribution of the necessaries of life” does apply well to hunter-gatherers. Except in hunter-gatherer societies “the hidden hand” manifested in jealousy and envy and the sum of individual self interests was a “fierce egalitarianism”.

Traits like envy still shape how we behave today in our complex highly networked societies because for most of human history they were evolutionarily advantageous.

This is why we still admire and respect humility, why we take such pleasure in seeing the mighty fall, why our children are so obsessively diligent when they are required to share a treat and why many of us feel awkward and uncomfortable when confronted by gold-plated ostentation. It is also why we respond so viscerally to inequality, why we regard narcissists as sociopaths and why demagogues are able to persuade us that elites — both real and imagined — must be brought to heel.

So if displays of excess during the holiday season put you in a foul mood, rather than suppressing your emotions, insult the turkey, mock the neighbors’ life-size animatronic Santa and scowl volubly if your gifts are not up to scratch, safe in the knowledge that even if it may not feel like it, if it wasn’t for behavior like this, we almost wouldn’t be celebrating the holidays in the first place.

How to break into the tech industry

Break into the tech industry by learning the skills you need to enter a pivotal role in any company, whether it’s a startup or established business. This eduCBA Project Management & Quality Management Bundle is a comprehensive training that focuses on the technical and practical components that make a strong project management hire, helping you jumpstart a lucrative new career.

This training includes 68 courses on project management, 22 on Quality Management, and 17 on Agile and Scrum methodology. While project management establishes a foundation for holistic strategies across all industries, quality management and Agile and Scrum methods focus on maintaining high quality and developing the most efficient processes. This training allows you to pursue any specialty or strategy you want to tackle, building your resume as you prep for in-demand certifications like PRINCE2, CBAP, PMP, and more.

Whether you’re applying Agile to your company’s software development approach, or using Scrum for sprint meetings and reviews working with cross-functional teams, you’ll understand how to assess and manage risk better while navigating the project lifecycle.

Take advantage of 1,450+ hours of training and change your career path: usually, this eduCBA Project Management & Quality Management Bundle is $2,249, but you can get it now for $39, or 98% off the usual price.

December 1, 2017

Drilling reawakens sleeping faults in Texas, leads to earthquakes

(Credit: Christopher Halloran via Shutterstock)

Since 2008, Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas and a handful of other states have experienced unprecedented surges of earthquakes. Oklahoma’s rate increased from one or two per year to more than 800. Texas has seen a sixfold spike. Most have been small, but Oklahoma has seen several damaging quakes stronger than magnitude 5. While most scientists agree that the surge has been triggered by the injection of wastewater from oil and gas production into deep wells, some have suggested these quakes are natural, arising from faults in the crust that move on their own every so often. Now researchers have traced 450 million years of fault history in the Dallas-Fort Worth area and learned these faults almost never move. “There hasn’t been activity along these faults for 300 million years,” says Beatrice Magnani, a seismologist at Southern Methodist University in Dallas and lead author of a paper describing the research, published today in Science Advances. “Geologically, we usually define these faults as dead.”

Since 2008, Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas and a handful of other states have experienced unprecedented surges of earthquakes. Oklahoma’s rate increased from one or two per year to more than 800. Texas has seen a sixfold spike. Most have been small, but Oklahoma has seen several damaging quakes stronger than magnitude 5. While most scientists agree that the surge has been triggered by the injection of wastewater from oil and gas production into deep wells, some have suggested these quakes are natural, arising from faults in the crust that move on their own every so often. Now researchers have traced 450 million years of fault history in the Dallas-Fort Worth area and learned these faults almost never move. “There hasn’t been activity along these faults for 300 million years,” says Beatrice Magnani, a seismologist at Southern Methodist University in Dallas and lead author of a paper describing the research, published today in Science Advances. “Geologically, we usually define these faults as dead.”

Magnani and her colleagues argue that these faults would not have produced the recent earthquakes if not for wastewater injection. Pressure from these injections propagates underground and can disturb weak faults. The work is another piece of evidence implicating drilling in the quakes, yet the Texas government has not officially accepted the link to one of its most lucrative industries.

Magnani and her colleagues studied the Texas faults using images of the subsurface similar to ultrasound scans. Known as seismic reflection data, the images are created by equipment that generates sound waves and records the speeds at which the waves bounce off faults and different rock layers deep within the ground. Faults that have produced earthquakes look like vertical cracks in a brick wall, where one side of the wall has sunk down a few inches so the rows of bricks no longer line up. Scientists know the age of each rock layer — each row of bricks — based on previous studies that have used a variety of dating techniques.

The seismologists compared images of faults in north Texas with images of other faults that have been active throughout geologic history. These active cracks are in the New Madrid Seismic Zone that encompasses parts of Missouri, Arkansas, Kentucky and Tennessee along the Mississippi River. New Madrid-area faults produced earthquakes as large as 7 or 8-magnitude in the early 1800s and have produced smaller quakes since then.

When Magnani and her colleagues examined the New Madrid faults, they saw evidence of earthquakes—the horizontal rows of bricks were offset at the fault line — from the distant past into the present. But images of the north Texas faults showed zero disturbances in the last 300 million years.

The scientists then took another step to refine their results. Their seismic reflection data cannot pick up vertical offsets smaller than 15 meters, or about 49 feet. Yet the recent north Texas earthquakes were so small they caused offsets of just a fraction of a centimeter. The seismologists wanted to be sure these faults had not been producing this kind of tiny earthquake all along. They were able to do this because the offsets representing rock moved by quakes are cumulative: each new quake adds more distance. The researchers took the 300-million-year time span and calculated the maximum number of small to medium sized quakes it would take to produce a cumulative offset just shy of 15 meters. That fell into the range of 3,800 to 6,000 earthquakes — or, roughly, an earthquake every 50,000 to 79,000 years. Even if temblors occurred that frequently, the probability of a natural earthquake sequence occurring in north Texas in the previous 10 years was only one in 6,000 and the probability of two sequences was one in 60 million. Since north Texas has had five earthquake sequences during that 10-year span, the scientists write that it is “exceedingly unlikely” that the recent quakes were natural.

Mark Zoback, an expert on induced seismicity at Stanford University, says he agrees with the paper’s conclusions that the recent Texas quakes are likely tied to oil and gas production. But he would not describe the faults as completely dormant. A fault that produces earthquakes every 60,000 years is still an active fault, just one that ruptures very rarely, Zoback says. He also notes that the energy released in an induced earthquake comes from the earth — the result of tectonic stresses building up at the fault over geologic time — and not from the wastewater injections themselves. “The injections can’t put energy into the ground,” said Zoback. “The energy has to be there already and the injection just triggers its release.”

The ethical, sustainable chocolate you love may be a fraud

(Credit: Shebeko via Shutterstock)

Ten percent of products in the food and drink category are “adulterated or mislabeled,” according to a new study by Ecovia Intelligence, an ethical product research firm. Seafood, parmesan cheese, Kobe beef, herbal tea—all of these products were investigated and outed as oft-disguised and mis-marketed in Larry Olmstead’s 2016 food fraud expose, “Real Food/Fake Food: Why You Don’t Know What You’re Eating and What You Can Do About It.”

But what about labeled grocery products we’re conditioned to trust? Especially products that can charge a high premium for being “ethical” or “sustainable”? Chocolate, particularly, comes to mind. The bean-to-bar phenomenon can command upwards of $10 for a single chocolate bar, but are we really getting what we pay for? According to an April 2016 study on millennial purchasing habits, the artisanal-loving generation often fails to ask questions about the ethics of their chocolate sourcing, so we asked the questions ourselves.

First, what, other than an arbitrary label, qualifies chocolate as sustainable?

“I see the sustainability discussion from two angles, the socioeconomic — fair prices and labor practices — and the environmental — sound agricultural practices, biodiversity, etc.,” says Michael Laiskonis, creative director of the Institute of Culinary Education in New York City.

“Most cocoa farms throughout the world are small family holdings of just a few acres and their output, high costs and intensive labor required often mean cocoa farmers straddle established poverty lines,” he explains. “The complex collection and distribution system as cocoa beans travel from origin to factory to consumer compounds the issue of fair farmer prices, who are often left with the smallest portion of a chocolate bar’s retail price.”

Laiskonis says he’s personally unaware of any intentional food fraud or mislabeling in the chocolate industry, but that doesn’t mean it’s not happening.

“There are few, if any industry standards (government or self-imposed) when it comes to labeling and understanding the process and provenance of a bar,” Laiskonis explains, noting that a few label cues, like an origin or cocoa variety statement, grower information and insight into the manufacturing process can help guide consumers toward sustainable choices.

While third-party certifications like “Direct Trade,” “Fair Trade,” “Rainforest Alliance” and “organic” may be helpful, they’re also cost-prohibitive for small farmers, as well as ineffective, thanks to bureaucracy in several cocoa-growing parts of the world. Pricing can also be an effective way to sort through chocolate bars, knowing that some chocolatiers will inflate their prices because of the popularity of the fine chocolate market, but a cheap chocolate bar probably reflects cheaply sourced beans or low-quality chocolate.

The best way to feel confident that your chocolate is ethical and sustainable is to know your maker.

“I often advise that the more transparent, detailed and credible the story offered by the chocolate-maker, the better chance that the chocolate is of higher quality, produced with greater care, and ultimately, with a greater sense of ethical responsibility,” Laiskonis says.

In the case of Greg D’Alesandre, the chocolate sourcer and owner of bean-to-bar chocolatier Dandelion Chocolate, an annual public sourcing report (which includes where the beans come from, how much Dandelion pays and how the operation works) helps him connect to consumers on a traceable human level.

D’Alesandre spends over 20 weeks of the year traveling to visit producers in 25 different cocoa-growing countries in order to find the best possible cocoa for his business, so he can feel comfortable with the farms he’s buying from.

“Most people in the world are trying to do a great job at the thing that they’re doing,” D’Alesandre told AlterNet, on a rare week he was actually working from his headquarters in San Francisco. He gives producers the benefit of the doubt, building trust with them in order to “be as transparent as humanly possible.”

Knowing producers personally, and having point people around the world, allows him to communicate openly with his clients and create relationships. But, he admits, “Trust is a tricky thing,” adding that “some people look to certifications [for buying chocolate], but we have a personal relationship with the people that we work with. With a certification, people go to audit what’s going on. But it’s easy to lie to an auditor; it may be harder to lie to me. An auditor is checking on you; I am buying the beans — lying to me can put our business relationship at risk.” And with all the elements he inspects, he says, “lying would become laughably complex.”

In one instance, D’Alesandre was relieved that a farm in the Dominican Republic informed him that a fermentory mixed its beans with another farm’s beans, making the cocoa to be used in the Dandelion bar a combination of blended beans rather than “single reserve.” D’Alesandre still purchased the beans, labeled the chocolate bars accordingly, and continued his relationship with the farm.

Because he only visits most of his producers one week out of the year or less, D’Alesandre knows that the other 51 weeks of the year could potentially look very different at the site, but still attributes on-the-ground research to knowing the true origin of a chocolate bar (he said some large companies, like Valrhona, excel at this).

“It’s much more about me understanding the people who we’re working with, to make sure that we have aligned values,” D’Alesandre said. “I rarely run into people who have any ill intent. They are sustenance and crop farmers trying to produce good cacao — the land is their livelihood.”

Certifications can be prohibitively expensive for farmers, so D’Alesandre will also look to see how well they’re treating the environment and using their land, avoiding burning crops and using chemical pesticides and fertilizers. Most likely, the farmers can’t afford chemicals, nor would they want to use them, as chemicals don’t help cocoa grow any faster. D’Alesandre also evaluates how money is distributed among workers, especially based on the cost of labor in each region.

To determine pricing for his chocolate, he looks at what “people need to survive” in a given area—not the standard rate companies are willing to pay for cocoa — in order to keep business ethical and sustainable. “That’s the biggest reason we have the sourcing program we have; [we don’t use] what the world market says is ‘fair.'”

To know if your chocolate is ethically, humanely and sustainably sourced, the best and perhaps only verifiable way is to see the production with your own eyes. With social media, that has become more doable, but the next best thing is speaking with your chocolatier or producer of bean-to-bar chocolate. D’Alesandre can tell detailed stories about the locations he’s visited, and he’s not going to sugarcoat the situations in cocoa farms across the planet.

While he’s never witnessed slave labor or forcible child labor on his site visits, he says it’s common to see children working with their families on their family farms. “In some countries, there are no schools; the kids are working with their families on the farm and they don’t perceive it as ‘labor,'” explains D’Alesandre. “There’s no other option for what to do with their child, but they want them to have an education and a better life.” Supporting ethical, sustainable small business can hopefully boost a local economy and lead to educational opportunities further down the line.

More than anything, knowing the reality of the everyday lives of the people growing and selling the cocoa will verify what a $10 bar of chocolate truly is. “[Some] people travel for an exotic vacation, rather than seeing what’s actually on the ground,” says D’Alesandre. “It’s just a nice story to tell, until you talk to the people who are actually involved.”

Melissa Kravitz is a writer in New York City who writes about food and culture for First We Feast, Thrillist, Elite Daily, Edible, and other publications.

Capture amazing aerial photography with this powerful drone

You know that incredible aerial footage you see on film, on television and in ads everywhere? Now you can capture that same unbelievable footage — plus be in charge of the artistic direction with this TRNDlabs Spectre Drone.

You get to enjoy an unprecedented amount of control and stability when you fly, whether you’re a beginner or expert flier. There are four high-speed propellors and an HD camera that would make the best smartphones envious, so you can take your aerial photography to the next level. And thanks to an impressive 50-meter range, you can explore and watch a live feed using the accompanying Spectre app.

For the adrenaline junkies looking to impress with a few neat party tricks, there’s a 6-axis gyro sensitivity that lets you do 360º flips with precision and power. Plus there are cutting-edge fly assist features including enhanced auto take-off and landing, and the ability to hold its altitude means you can still enjoy stability no matter what flips you’re trying to land. You can even use the built-in LED lights to fly at night!

Use this drone to adventure to spaces you couldn’t ordinarily go: usually, this TRNDlabs Spectre Drone is $149.99, but you can get it now for $92.99 — that’s further reduced from the original sale price of $99.99.

James Franco sticks the landing in “The Disaster Artist”

Dave Franco and James Franco in "The Disaster Artist" (Credit: A24)

With the release of “The Disaster Artist,” the film based on the book of the same name by Greg Sestero and Tom Bissell, James Franco is actually generating Oscar buzz for playing Tommy Wiseau, the writer, director, producer and star of arguably the greatest bad movie of all time, “The Room.”

“The Room,” for those who don’t know, is a cult film like no other. In their book, Sestero and Bissell describe the film as an act of “cinematic hubris,” made in 2003 for $6 million of Wiseau’s money. (Although no one knows how Wiseau came by his fortune, a bank teller assures a check-cashing crew member that Wiseau’s account is a “bottomless pit.”) The film earned $1,800 at the box office during its two-week, Oscar-qualifying run in Los Angeles in 2003, and received reviews only a masochist would read. Wiseau promoted the film with an expensive billboard in Los Angeles for five years. The signage features Wiseau’s visage, the title, credits, website and (Tommy’s) phone number.

His efforts eventually paid off. A cult of fans formed around the film after the theater posted a “no refund” sign, which dared viewers to sit through the entire film.

It slowly caught on, and monthly midnight screenings of the film began along with celebrities holding private “Room” parties to share their enthusiasm for this craptacular film. The enjoyment of the film comes from the absolute earnestness of its awfulness. “The Room” is completely without irony — and some would insist without logic — which is what makes it unintentionally hilarious.

As Sestero and Bissell write in their book, this vanity project became “a blockbuster . . . [just] not in the way Tommy had envisioned.” They describe it as “a drama that is a comedy that is also an existential cry for help that is finally a testament to human endurance.”

“The Room” asks fans, in Wiseau’s unidentified accent,* to play catch football in tuxedos in the alley, grimace at the sight of his naked ass, groove to the slow-jam music, and throw spoons at the screen because Wiseau’s lame efforts at production design have a framed photo of spoons on a table in Johnny and Lisa’s apartment. Sure, the script is a collection of non sequiturs, plot holes and variations on Tommy’s classic refrain, “Hi, doggie!” and more. But as Tommy famously declared on set, “Continuity is in your forehead!” Detractors can simply “leave your stupid comments in your pocket,” as Mark says in Wiseau’s “Tennesee [sic] Williams-inspired” script.

A melodramatic love triangle, “The Room” concerns Johnny (Wiseau), a man whose world crumbles after he learns his fiancée, Lisa (Juliette Danielle), is having an affair with his best friend, Mark (Greg Sestero).

There are other memorable characters who enter “The Room,” from Lisa’s mom (Carolyn Minnott), who “definitely has breast cancer,” to Denny (Philip Haldiman), a man-child who owes money to Chris-R (Dan Janjigian). “What kind of money?!” Lisa asks in the film’s famous rooftop scene. It is one of the many questions in the film that go unanswered.

“The Room” is so bad it’s great. Wiseau’s cinematic masturbation creates a kind of Stockholm syndrome for the viewer who becomes awestruck by it. The film’s devotees are known as “Roomies”

One of the people enchanted by “The Room” is James Franco. When he decided to embark on making “The Disaster Artist,” and playing Wiseau, one imagines Franco getting as excited as Wiseau did with Sestero. James likely asked his brother Dave, a fellow “Roomie,” to make the film with him just as Wiseau asked Sestero. In fact, one can imagine James coaxing Dave with a “Let’s do this!” and pinky swearing to see the film through as Tommy (James Franco) and Greg (Dave Franco) do in the film “The Disaster Artist.” (The pinky swearing is not in Sestero’s book.)

If Greg drinks Tommy’s Kool-Aid (if not his milkshake) for “The Room,” Franco has done the same thing with “The Disaster Artist.” Franco is committed to inhabiting “Planet Tommy” with a go-for-broke work ethic as well as dyed long black hair, an indeterminate accent and non sequiturs.

The actor/director Franco has had mixed success in his adaptation of books into films. His William Faulkner and Cormac McCarthy dramas, “As I Lay Dying” and “Child of God,” respectively, are ambitious, but difficult. Franco’s foray into making films about films begat the documentary “Interior. Leather Bar.,” which reimagined William Friedkin’s “Cruising.” It was a curious misfire.

But with his turn as Tommy Wiseau in “The Disaster Artist,” Franco may have found an appropriate vehicle for his specific talents. Playing Wiseau allows Franco to act hammy, bare his ass, and crave approval — all things Franco does often and well.

Wiseau’s fearlessness is something Sestero admires in the book, and Franco seems to have Wiseau’s ambitions without self-awareness down pat.

How else to excuse Franco’s exhaustingly relentless career act of performance art that has him as an NYU student, an artist, an author, an actor, a writer, a director and more.

Perhaps it is the shameless need to expose themselves that also drives Wiseau and Franco to each show their ass in their films. Viewers wince at and mock the age-unidentified Wiseau’s bare derriere in “The Room.” As Sestero recounts in “The Disaster Artist,” Wiseau’s insistence on having an open (not closed) set during his love scenes was cringe-inducing for cast and crew. That Franco as Wiseau has an extended meltdown wearing only a cock sock in “The Disaster Artist” seems to be equally vain and self-serving. Although to Franco’s credit, he plays it for laughs, not gasps.

Restraint is not something either Wiseau or Franco have much of. Then again, both performers are ridiculed as much as they are respected.

Wiseau, before he was (in)famous, “acted like he was famous,” according to Sestero. Franco never seemed to miss an opportunity to be in the spotlight, either. There is a kind of “Look at me!” quality to Franco’s “The Disaster Artist”: Franco the filmmaker showcases memorable scenes of Wiseau in “The Room” side-by-side with scenes he re-created almost exactly for “The Disaster Artist.” These clips are terrific, and very amusing, but they also feel like Franco — like Wiseau before him — is seeking approval from everyone for his efforts.

Reading the book “The Disaster Artist” one gets the sense of how desperately Tommy wants to be loved and taken seriously. Wiseau is needy, selfish and pathetic. But Sestero feels empathy for his lost, lonely friend who does actually realize his improbable dream.

This friendship forms the emotional core of Franco’s “The Disaster Artist” as well. It is perhaps why the film is so satisfying, in its way. “The Disaster Artist” celebrates and satirizes its hero at the same time. Franco’s canny performance walks that fine line, going back and forth, taunting the audience to admire him like we do Wiseau.

*When I interviewed Wiseau for the Philadelphia City Paper in January 2012 and asked about his accent and where he was from — a question that still remains largely unanswered today — he said: “I grew up New Orleans, but used to live in France. My uncle used to work in Petroleum. Now I am an American and proud of it. People say I exaggerate my accent. I like sports.”

The antidote to “Nazi next door” profiles

Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus (Credit: Screengrab Bethesda Softworks)

You’ve just arrived in Roswell, N.M. You’re undercover, disguised as a firefighter, whose mission is to detonate a nuclear bomb (housed in a dummy fire extinguisher) in an underground Nazi facility directly below Area 51. As you walk the streets, you notice two hooded Klan members (in full KKK attire) in broad daylight, casually chatting. The KKK run much of the U.S. now that the Nazis are in charge. Off in the distance, a Nazi parade passes. You can hear over a P.A. system: “Die Bürger of Roswell, be united. Remember our motto: One world. One future. One leader.”

A few minutes later, in a Nazi-American diner, you pull out your gun and start mowing down Nazi officers. This is the beginning of “Wolfenstein 2: The New Colossus,” a new first-person-shooter video game that puts you in the shoes of a resistance leader fighting back against the Nazi takeover of the United States. And what better way to push back against the normalization of white supremacists and Nazi sympathizers than with a video game that normalizes killing (virtual) Nazis?

The “Wolfenstein” video game franchise began in 1992 — back when Nazi-killing wasn’t controversial at all — with “Wolfenstein 3D,” developed by iD Software. That 1992 MS-DOS game, along with 1993’s “Doom,” popularized the first-person-shooter genre, in which the player takes the perspective of the character, centering the view around a gun. The 1992 game (which is now playable in your browser) puts you in the shoes of Allied spy William “B.J.” Blazkowicz as he escapes a Nazi castle. After his escape, B.J. uncovers the Nazi plot to conscript an undead mutant army. The game concludes with a battle against Adolf Hitler in a robot suit (more popularly known as “Mecha-Hitler”) wielding four gatling guns.

Fast forward from 1992 to 2017. MachineGames develops “Wolfenstein 2: The New Colossus,” at a tumultuous moment in U.S. history: Tiki torch–wielding far-right rallies, a president who thinks white supremacists have valid grievances, and the rising prominence of far-right fringe figures like Richard Spencer have created a toxic cloud of Nazi-sympathizer stink lingering over America. “Wolfenstein 2″ is an odd mirror on our reality: Set in 1961, yet in an alternate universe where the Nazis won World War II, “Wolfenstein 2” follows the same protagonist as the first game, B.J. Blazkowicz, as he attempts to undo the Nazi occupation of America.

It’s more than just a shooter about a latent rebellion, though. B.J. Blazkowicz symbolizes a number of different American values. He protects a ragtag group of German resisters (acting under the name of the real-life German resistance group, the Kreisau Circle) and a Black Panther-esque American resistance group rescued from their hideout in the Empire State Building. These plot points solidify B.J.’s desire to protect the diverse and multicultural heritage of the United States, despite the fact that in this alternate reality, the nation doesn’t exist anymore.

Thus, “Wolfenstein 2” is a cathartic outlet for our country’s current crises. The company behind the game also executed the perfect marketing scheme for its brutally violent Nazi-killing simulator. Witness this marketing video depicting a Nazi being punched in-game, accompanied by the text “There is only one side.” Does this remind you of current events?

There is only one side. #NoMoreNazis #Wolf2 pic.twitter.com/7Ctu265Mus

— Wolfenstein (@wolfenstein) October 15, 2017

Another tweet from the game makers directly calls out the presidency — this one features the text “Make America Nazi-Free Again” running over the video.

Make America Nazi-Free Again. #NoMoreNazis #Wolf2 pic.twitter.com/52OESypw4P

— Wolfenstein (@wolfenstein) October 5, 2017

Beyond “Wolfenstein’s” Twitter leaning into current-day political issues, there’s also marketing materials like this irreverent trailer, in which Wayne Newton’s lounge classic “Danke Schoen” plays in the background of a bloody montage of shooting, disintegrating and mutilating Nazis. What does it mean when, in 2017, a video game has a stronger condemnation of Nazis than the U.S. president?

Hidden within the game are explicit digs at contemporary alt-right and white supremacist leaders. An in-game newspaper (which you can find as a collectible) headline reads “Meet The Dapper Young KKK Leader With A Message Of Hope.” Shrewd commentators have noticed that this is almost certainly a dig on Richard Spencer, as it seems to reference an October 2016 Mother Jones article headlined, “Meet The Dapper White Nationalist Who Wins Even If Trump Loses.”

In a Rolling Stone interview with Pete Hines, vice president of marketing at Bethesda Softworks (distributor for “Wolfenstein 2”), Hines states:

Nazis are bad, and in Wolf II you get to kick their asses and it’s fun. There are actual Nazis marching openly on the streets of The United States of America in 2017. BJ would not be OK with that – we are not ok with that — and the marketing reflects that attitude. When you have an opportunity to take a public stand against Nazis emerging in America, that’s an opportunity that shouldn’t be passed up.

Interestingly, Hines also says that the game was not intended to be a direct commentary on today’s political climate; perhaps that was a calculated political statement on his part. Still, the game is screamingly relevant, and its marketing tactics are unique for an industry that tries to play it safe (at least overtly) when it comes to politics. For instance, the original announcement trailer for Ubisoft’s unreleased game “Far Cry 5″ stirred up controversy when viewers noticed how its antagonists — a cult in the heartland of Montana — resembled real-life Christian extremists. The gaming community has a reputation for harboring far-right sentiment (see: Gamergate); hence, this plot point stirred controversy. Some fans called for “Far Cry 5″ to be canceled, claiming they were – as Americans – being insulted. Game maker Ubisoft could have doubled-down on the obvious – but supposedly coincidental – parallels to real-life politics; indeed, calling out the antagonistic, bigoted qualities of Christian extremists seems pretty uncontroversial. But Ubisoft instead took the easy way, denying any direct correlation between current events and its game. Avoiding this easy opening to take a stand — despite having such a politically charged basis for a game — is frustrating in an industry that is known for being infected with sexist, even regressive cultural politics.

Which is what makes “Wolfenstein 2″ so unique among video games. And while the game has a fairly normalized, surface-level machismo, in the case of the genre and subject matter, “Wolfenstein 2” seems justified in this regard. Yes, “Wolfenstein” as a series epitomizes the type of jingoism that many first-person shooters adversely portray. But it has a right to do so. To the question “Should we punch Nazis?” “Wolfenstein’s” answer is: Yes, because f**k Nazis.

Lately, there’s been a creepy trend of media outlets attempting to humanize Nazis and white supremacists; this was evident in the recent brouhaha over a New York Times profile of an avowed white nationalist, which took pains to describe said white nationalist’s love of “Seinfeld” and paint a loving portrait of how he “sauté[ed] minced garlic with chili flakes.” But “Wolfenstein” takes the opposite tack: no humanization here. Just good ol’ fashioned Nazi-killing. Maybe the New York Times should take a page from “Wolfenstein’s” book.