Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 221

December 3, 2017

Jet fuel from sugarcane? It’s not a flight of fancy

(Credit: AP Photo/Michael Probst, File)

The aviation industry produces 2 percent of global human-induced carbon dioxide emissions. This share may seem relatively small – for perspective, electricity generation and home heating account for more than 40 percent – but aviation is one of the world’s fastest-growing greenhouse gas sources. Demand for air travel is projected to double in the next 20 years.

Airlines are under pressure to reduce their carbon emissions, and are highly vulnerable to global oil price fluctuations. These challenges have spurred strong interest in biomass-derived jet fuels. Bio-jet fuel can be produced from various plant materials, including oil crops, sugar crops, starchy plants and lignocellulosic biomass, through various chemical and biological routes. However, the technologies to convert oil to jet fuel are at a more advanced stage of development and yield higher energy efficiency than other sources.

We are engineering sugarcane, the most productive plant in the world, to produce oil that can be turned into bio-jet fuel. In a recent study, we found that use of this engineered sugarcane could yield more than 2,500 liters of bio-jet fuel per acre of land. In simple terms, this means that a Boeing 747 could fly for 10 hours on bio-jet fuel produced on just 54 acres of land. Compared to two competing plant sources, soybeans and jatropha, lipidcane would produce about 15 and 13 times as much jet fuel per unit of land, respectively.

Creating dual-purpose sugarcane

Bio-jet fuels derived from oil-rich feedstocks, such as camelina and algae, have been successfully tested in proof of concept flights. ASTM International, a global standards development organization, has approved a 50:50 blend of petroleum-based jet fuel and hydroprocessed renewable jet fuel for commercial and military flights.

However, even after significant research and commercialization efforts, current production volumes of bio-jet fuel are very small. Making these products on a larger scale will require further technology improvements and abundant low-cost feedstocks (crops used to make the fuel).

Sugarcane is a well-known biofuel source: Brazil has been fermenting sugarcane juice to make alcohol-based fuel for decades. Ethanol from sugarcane yields 25 percent more energy than the amount used during the production process, and reduces greenhouse gas emissions by 12 percent compared to fossil fuels.

We wondered whether we could increase the plant’s natural oil production and use the oil to produce biodiesel, which provides even greater environmental benefits. Biodiesel yields 93 percent more energy than is required to make it and reduces emissions by 41 percent compared to fossil fuels. Ethanol and biodiesel can both be used in bio-jet fuel, but the technologies to convert plant-derived oil to jet fuel are at an advanced stage of development, yield high energy efficiency and are ready for large-scale deployment.

When we first proposed engineering sugarcane to produce more oil, some of our colleagues thought we were crazy. Sugarcane plants contain just 0.05 percent oil, which is far too little to convert to biodiesel. Many plant scientists theorized that increasing the amount of oil to 1 percent would be toxic to the plant, but our computer models predicted that we could increase oil production to 20 percent.

With support from the Department of Energy’s Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy, we launched a research project called Plants Engineered to Replace Oil in Sugarcane and Sorghum, or PETROSS, in 2012. Since then, through genetic engineering we’ve increased production of oil and fatty acids to achieve 12 percent oil in the leaves of sugarcane.

Now we are working to achieve 20 percent oil – the theoretical limit, according to our computer models – and targeting this oil accumulation to the stem of the plant, where it is more accessible than in the leaves. Our preliminary research has shown that even as the engineered plants produce more oil, they continue to produce sugar. We call these engineered plants lipidcane.

Multiple products from lipidcane

Lipidcane offers many advantages for farmers and the environment. We calculate that growing lipidcane containing 20 percent oil would be five times more profitable per acre than soybeans, the main feedstock currently used to make biodiesel in the United States, and twice as profitable per acre as corn.

To be sustainable, bio-jet fuel must also be economical to process and have high production yields that minimize use of arable land. We estimate that compared to soybeans, lipidcane containing 5 percent oil could produce four times more jet fuel per acre of land. Lipidcane with 20 percent oil could produce more than 15 times more jet fuel per acre.

And lipidcane offers other energy benefits. The plant parts left over after juice extraction, known as bagasse, can be burned to produce steam and electricity. According to our analysis, this would generate more than enough electricity to power the biorefinery, so surplus power could be sold back to the grid, displacing electricity produced from fossil fuels – a practice already used in some plants in Brazil to produce ethanol from sugarcane.

A potential US bioenergy crop

Sugarcane thrives on marginal land that is not suited to many food crops. Currently it is grown mainly in Brazil, India and China. We are also engineering lipidcane to be more cold-tolerant so that it can be raised more widely, particularly in the southeastern United States on underutilized land.

If we devoted 23 million acres in the southeastern United States to lipidcane with 20 percent oil, we estimate that this crop could produce 65 percent of the U.S. jet fuel supply. Presently, in current dollars, that fuel would cost airlines US$5.31 per gallon, which is less than bio-jet fuel produced from algae or other oil crops such as soybeans, canola or palm oil.

Lipidcane could also be grown in Brazil and other tropical areas. As we recently reported in Nature Climate Change, significantly expanding sugarcane or lipidcane production in Brazil could reduce current global carbon dioxide emissions by up to 5.6 percent. This could be accomplished without impinging on areas that the Brazilian government has designated as environmentally sensitive, such as rainforest.

In pursuit of ‘energycane’

Our lipidcane research also includes genetically engineering the plant to make it photosynthesize more efficiently, which translates into more growth. In a 2016 article in Science, one of us (Stephen Long) and colleagues at other institutions demonstrated that improving the efficiency of photosynthesis in lipidcane increased its growth by 20 percent. Preliminary research and side-by-side field trials suggest that we have improved the photosynthetic efficiency of sugarcane by 20 percent, and by nearly 70 percent in cool conditions.

Now our team is beginning work to engineer a higher-yielding variety of sugarcane that we call “energycane” to achieve more oil production per acre. We have more ground to cover before it can be commercialized, but developing a viable plant with enough oil to economically produce biodiesel and bio-jet fuel is a major first step.

Now our team is beginning work to engineer a higher-yielding variety of sugarcane that we call “energycane” to achieve more oil production per acre. We have more ground to cover before it can be commercialized, but developing a viable plant with enough oil to economically produce biodiesel and bio-jet fuel is a major first step.

Life after coal for in Germany

(Credit: AP)

It’s a sunny October day on the outskirts of the west German town of Bottrop. A quiet, two-lane road leads me through farm pasture to a cluster of anonymous, low-lying buildings set among the trees. The highway hums in the distance. Looming above everything else is a green A-frame structure with four great pulley wheels to carry men and equipment into a mine shaft. It’s the only visible sign that, almost three quarters of a mile below, Germany’s last hard coal lies beneath this spot.

Bottrop sits in the Ruhr Valley, a dense stretch of towns and suburbs home to 5.5 million people. Some 500,000 miners once worked in the region’s nearly 200 mines, producing as much as 124 million tons of coal every year.

Next year, that era will come to an end when this mine closes. The Ruhr Valley is in the midst of a remarkable transformation. Coal and steel plants have fallen quiet, one by one, over the course of the last half-century. Wind turbines have sprung up among old shaft towers and coking plants as Germany strives to hit its renewable energy goals.

But the path from dirty coal to clean energy isn’t an easy one. Bottrop’s Prosper-Haniel coal mine is a symbol of the challenges and opportunities facing Germany — and coal-producing states everywhere.

Around the world, as governments shift away from the coal that fueled two ages of industrial revolution, more and more mines are falling silent. If there’s an afterlife for retired coal mines, one that could put them to work for the next revolution in energy, it will have to come soon.

* * *

The elevator that carries Germany’s last coal miners on their daily commute down the mine shaft travels at about 40 feet a second, nearly 30 miles an hour. “Like a motorcycle in a city,” says Christof Beicke, the public affairs officer for the Ruhr mining consortium, as the door rattles shut. It’s not a comforting analogy.

The brakes release and, for a moment, we bob gently on the end of the mile-and-a-half long cable, like a boat in dock. Then we drop. After an initial flutter in my stomach, the long minutes of the ride are marked only by a strong breeze through the elevator grilles and the loud rush of the shaft going by.

When the elevator finally stops, on the seventh and deepest level of the mine, we file into a high-ceilinged room that looks like a subway platform. One of the men who built this tunnel, Hamazan Atli, leads our small group of visitors through the hall. Standing in the fluorescent light and crisp, engineered breeze, I have the uncanny sense of walking into an environment that humans have designed down to the last detail, like a space station or a submarine.

A monorail train takes us the rest of the way to the coal seam. After about half an hour, we clamber out of the cars and clip our headlamps into the brackets on our hard hats. It is noticeably warmer here. There is a sulfurous smell that grows stronger as we walk down the slight incline toward the deepest point of our day, more than 4,000 feet below the surface, and duck under the first of the hydraulic presses that keep the ceiling from collapsing on us.

Because this seam is only about five feet high, we have to hunch as we move through the tunnel of presses, stepping through deep pools of water that swallow our boots. The coal-cutting machine is stalled today, otherwise it would be chewing its way along the 310-yard-long seam, mouthparts clamped to the coal like a snail to aquarium glass. The coal would be sluiced away on a conveyor belt to the surface, and the hydraulic presses would inch forward, maintaining space for the miners to work.

Instead, the mine is eerily quiet. Two miners, their faces black, squeeze past us. As we sit, sweating and cramped under the hydraulic presses, the bare ceiling above the coal seam gives up an occasional gasp of rock, showering down dust and debris.

Later, in a brightly lit room back on the surface, Beicke from the mining consortium asks me what I thought of the mine. I tell him that it seems like an extreme environment for humans. “Yes,” he nods, “it is like an old world.”

* * *

A few days earlier, Beicke and I had trekked to the top of a hill outside the long-shuttered Ewald Mine in Herten, a half-hour drive from Bottrop. We climbed a set of stairs to a platform with a view over the whole region, the fenced-off or leased-out buildings of the old mine sitting below us.

The Ruhr Valley encompasses 53 cities of Germany’s once-formidable industrial heartland, including Essen, Bochum, and Oberhausen. The whole region was once low-lying riverland, but these days large hills rear above the landscape. These are the heaps of rock removed from the mines, tons of slag excavated with the coal and piled up. It’s a stark visual reminder of what’s been emptied out from underneath.

As the mines have closed down, most of these heaps have been covered with grass, and many have been crowned with a statue or other landmark. On one hill outside Essen, there’s a 50-foot steel slab by the sculptor Richard Serra; on another, atop other heaps, wind turbines stand like giant mechanical daisies.

Germany has been hailed as a leader in the global shift to clean energy, putting aside its industrial past for a renewable future faster than most of the industrialized world. The country has spent more than $200 billion on renewable energy subsidies since 2000 (compare that to the United States, which spends an estimated $20 billion to subsidize fossil fuel production every year).

In 2011, Chancellor Angela Merkel’s government announced the beginning of a policy of “energiewende” to wean Germany off fossil fuels and nuclear power. Last year, wind, solar, and other renewables supplied nearly 30 percent of the country’s electricity. The goal now is to hit 40 percent in the next 10 years, while slashing carbon emissions 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2020.

That transition has happened alongside attempts to restore the Ruhr Valley’s landscape. For every hill raised above ground level, there is an accompanying depression where the land subsided as coal seams were emptied out. The land here sank as the coal seams closest to the surface were emptied out. Overall, the region has sunk about 80 feet.

Streams that enter the Ruhr Valley are no longer able to flow out the other side, Beicke explains, and now water pools in places it never used to. The mining company is responsible for pumping that water away, as well as pumping groundwater across the region, to keep the water table below the level of the existing mines. Any contaminated water in the old mines must be removed and treated to keep it from polluting the groundwater.

These are just a few of the mining company’s “ewigkeitsaufgaben” — literally, eternity tasks.

“As long as 5 or 6 million people want to live in this area, we will have to do that,” Beicke tells me, of the expensive water management. “Maybe 2,000 years in the future that will change, but until that happens, well.” He shrugs.

The government gives the mining consortium 220 million euros a year in subsidies to deal with all the consequences of coal mining. Unlike in the United States, where aging coal companies often sell off their assets or declare bankruptcy to dodge clean up bills, here the mining company will be pumping and treating water long after it has stopped being a mining company at all.

Despite a national commitment to a broad energy transition, many now think that Germany will fall short of its renewable energy targets, thanks to a number of confounding economic and social factors, including the continued use of a coal alternative called lignite, also known as “brown coal.” Germans have the highest electricity costs in Europe, and the rise of the country’s extreme right-wing party in the last election has been pinned, in part, on those high bills.

If Germany does continue to progress toward its climate goals, much of the new energy is sure to come from wind power. Germany has more wind turbines than any other country in Europe, many of them installed in the last six or seven years. But wind doesn’t blow consistently, so this shift has been a challenge for the electrical grid. Even slight disruptions in the power supply can have wide-ranging consequences.

As more wind turbines are turned on, and more coal plants are retired, this problem will only get bigger, and the challenge of storing all that intermittent energy will be even more important. Here’s where the country’s retired coal mines might prove useful again — as giant batteries for clean energy.

* * *

To turn a coal mine into a battery, all you need is gravity.

OK, you also need a lot of money (more about that later), but the basic principle is gravitational. When you lift a heavy object, it stores the power used to lift it as potential energy until it’s released and falls to the ground.

Let’s say the heavy object you’re lifting is water. When you want to store energy, you just have to pump the water uphill, into a reservoir. When you want to use that energy, you let the water flow back down through a series of turbines that turn the gravitational rush into electricity.

This is the basic plan André Niemann and Ulrich Schreiber conceived when they were dreaming up new ways to use old mines. It seemed intuitive to the two professors at the University of Essen-Duisburg: The bigger the distance between your upper and lower reservoirs, the more energy you can store, and what’s deeper than a coal mine?

Schreiber, a geologist, realized it was theoretically possible to fit a pumped storage reservoir into a mine, but it had never been done before. Niemann, a hydraulic engineer, thought the proposal was worth pursuing. He drummed up some research money, then spent a few years conducting feasibility studies, looking for a likely site in the Ruhr Valley and running the numbers on costs and benefits.

After studying the region’s web of fault lines and stratigraphic layers, Niemann’s team settled on the closing Prosper-Haniel mine. Their underground reservoir would be built like a massive highway tunnel, a reinforced concrete ring nine miles around and nearly 100 feet high, with a few feet difference in height from one side of the ring to the other to allow the water to flow, Niemann explains.

At max storage, the turbines could run for four hours, providing 800 megawatt-hours of reserve energy, enough to power 200,000 homes.

The appeal of pumped storage is obvious for Germany. Wind and sun are fickle energy sources — “intermittent” by industry lingo — and energy storage can help smooth out the dramatic spikes. When the wind gusts, you can stash that extra power in a battery. When a cloud moves over the sun, you can pull power back out. It’s simple and, as the grid handles more and more renewable energy, increasingly needed.

The only problem: It’s expensive.

As wind turbine and solar technologies have become cheaper, energy storage costs have stayed high. Pumped hydro, especially, requires a big investment up front. Niemann estimates it would cost between 10,000 and 25,000 euros per meter of tunnel just to build the reservoir, and around 500 million euros for the whole thing. Right now, neither the government nor the energy companies in the Ruhr Valley are willing to make that kind of investment.

“It’s not a business, it’s a bet, to be honest,” Niemann says with a shrug.

In spite of the increasing unlikelihood of the proposal becoming reality, delegations from the United States, China, Poland, France, South Africa, and Slovakia, among others, have visited Niemann and Schreiber in Essen to learn about mine pumped-storage. Virginia’s Dominion Energy has been studying the idea with the support of a Republican state senator, and a group from Virginia Tech paid a visit the week after I did.

Here’s where any attempt to draw comparisons across the Atlantic gets complicated. In the United States, the federal government has been relatively hands-off in helping coal-dependent regions move on from the industries that fueled their way of life. In Germany, by contrast, there’s a broad agreement about the need to shift to renewable sources of energy. And yet, even with all that social, political, and economic foresight, important and necessary innovations remain stalled for lack of investment.

The Ruhr Valley is not Appalachia. And yet the two regions share key similarities that offer some important lessons about the a path to a cleaner, more sustainable future.

* * *

Dying industries take more than jobs with them. Towns built around a single industry, like coal mining, develop a shared identity. For many workers and their families, it’s not as simple as picking up and finding a new line of work when the mine closes. Mining is seen as a calling, an inheritance, and people want their way of life back.

That’s how residents of the Ruhr responded when coal jobs started to decline.

“For a long time, people thought the old times would come back, the old days would return,” says Kai van de Loo, an energy and economics expert for a German coal association in Essen. “But they can never come back.”

In the United States, of course, calls to bring back the old days often works wonders as a political sales pitch. Donald Trump campaigned for president on promises to stop the “war on coal” and revive the dying industry, and mining towns across the Rust Belt supported him.

In Pennsylvania’s Mon River Valley, home to a once-thriving underground mining complex bigger than Manhattan, mining continues to exert an oversized influence. Some 8,000 people work in coal in the state, a portion of the 50,000 coal jobs left in the United States. That’s a far cry from the 180,000 people who worked in the industry 30 years ago. worked in or around coal mines only 30 years ago.

And the legacy of coal mining on the landscape is hard to miss. Bare slag heaps rise above the trees, dwarfing the towns beside them. Maryann Kubacki, supervisor of East Bethlehem in Washington County, says that during rainy spells the township has to shovel the gritty, black runoff from their storm sewers.

But without the federal government leading the way with financial support as it has in Germany, getting these former coal towns on a new track is a daunting task. Veronica Coptis, director of the Center for Coalfield Justice in Pennsylvania, says that organizing people to put pressure on mining companies is a delicate matter. People don’t want to hear that coal is bad, or that its legacy is poisoned. “We want an end to mining,” she says, “but we know it can’t happen abruptly.”

Back in Germany, the mayor of Bottrop, Bernd Tischler, has been thinking about how to kick coal since at least the early 2000s, long before the federal government put an end date on the country’s mining. An urban planner by training, Tischler has a knack for long-range strategy. After he took office in 2009, Tischler thought Bottrop could reinvent itself as a hub of renewable energy and energy efficiency. He devised heating plants that run off methane collected from the coal mine, and made Bottrop the first town in the Ruhr with a planned zone for wind energy.

In 2010, Bottrop won the title of “Innovation City,” a model for what the Ruhr Valley cities could become. Bottrop now gets 40 percent of its energy from renewables, Tischler said, 10 percentage points above the national average.

Describing this transformation, Tischler makes it almost sound easy. I explain that the issue of coal seems to track larger divisions in the United States, and so discussions inevitably turn heated, emotional.

“In Bottrop, the people of course feared for the process of the end of the coal mining,” he said. But Tischler believes mining towns have an advantage that can help them adapt to change: They’re more cohesive. In the mines, people are used to working together and looking out for each other. Distrust is dangerous, even deadly.

The Ruhr cities absorbed waves of Polish, Italian, and Turkish laborers over the years. And they’ve managed to get along well, knitting a strong social fabric, Tischler said. In the past few years, Bottrop, a town of 117,000 people, has resettled thousands of Syrian refugees in new housing.

A strong social fabric isn’t enough to survive the loss of a major industry, of course. Some promising industry — technology and renewables in Bottrop’s case — has to be found to replace it.

“I think the responsibility of the mayors and the politicians is to change the fear into a new vision, a new way,” he says. “You can’t do it against your people; you have to convince your people. You have to work together with institutions and stakeholders that don’t normally work together, [so that] we are sitting in the same boat and we are rowing in the same direction.”

Reporting for this story was supported in part by the Heinrich Böll Stiftung Foundation.

Why teamwork is better than attempting lone heroism in science

(Credit: Shutterstock)

The best way for scientists — or anybody, really — to address shortcomings after experiencing failure is teamwork. And never has that been more clearly apparent than in the story of Doxil, the first nanomedicine, which failed multiple times before a resourceful team cracked the code.

The best way for scientists — or anybody, really — to address shortcomings after experiencing failure is teamwork. And never has that been more clearly apparent than in the story of Doxil, the first nanomedicine, which failed multiple times before a resourceful team cracked the code.

Nanomedicine is the application of nanoscale technologies (think about it as really, really tiny pieces of matter — 10,000 times smaller than a strand of hair or 100 times smaller than a red blood cell) for the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and study of disease and human health. It’s pretty successful at getting funded as well — privately held nanomedicine companies (such as Nanobiotix) are getting a lot of money — in the tens of millions of dollars — from pharmaceutical giants such as Pfizer and Merck.

But nanomedicine wasn’t always such a buzzworthy topic — it really hit the scene in the 1990s when an anti-cancer drug called Doxil became the first FDA-approved nanomedicine-based therapy thanks to a multinational team headed by biochemist Yechezkel Barenholz at Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

Decades in the making

Barenholz believed as far back as the late 1970s that chemotherapy could be improved by placing anti-cancer drugs in nanoscaled carriers made of lipids — the stuff that forms the membranes of all the cells in our body. Placing the free-floating drug molecules into carriers takes advantage of the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, in which nanosized particles in the blood stream should enter and accumulate in solid tumors more easily than in healthy tissue.

Placing drugs in nanocarriers would cause fewer side effects and require smaller doses

One of the characteristics of tumors is their rapid growth, causing blood vessels to grow abnormally, which results in tiny gaps in the vessel walls that nanoparticles can pass through easily. Another consequence of rapid growth is the suppression of “lymphatic drainage,” meaning that the lymph fluid in tumors can’t clear out waste products and nanoparticles as effectively as in healthy tissues, causing more accumulation in tumors than in the rest of the body. Ideally, placing the drugs in nanocarriers would cause fewer side effects and require smaller doses as a result.

Barenholz began to develop early prototypes of such a drug in 1979 with oncologist Alberto Gabizon. But in 1987, that trial drug, called OLV-DOX, failed its clinical trial. The carriers were too large; they didn’t have enough of the drug inside of them to be effective, and they were readily destroyed by the body’s immune system.

In the interim, though, Barenholz started a parallel project as part of a team. In 1984, after chatting with an old colleague from UC–San Francisco, Dimitri Papahadjopoulos, Barenholz was convinced to take a sabbatical at Papahadjopoulos’s startup, Liposome Technology Inc. (LTI) in California, on the condition that LTI would support the ongoing Doxil research at Hebrew University at the same time.

Second time’s the charm

In the 1990s, Barenholz and his team at LTI worked together on what they called “stealth liposomes.” An outer layer of a polymer called polyethylene glycol (commonly called PEG) was added to the lipid carrier to extend the circulation time of the liposomes. This polymer is very hydrophilic — it interacts well with water, so that the closely packed water molecules at the surface of the liposome will prevent the liposomes from interacting with any proteins or cells in the blood stream, allowing them to reach their intended target.

At the same time, Barenholz was working in his lab in Israel to figure out a way to make the nanocarriers smaller while still being able to put enough of the drug inside to make the treatment effective. These teams patented these new technologies by 1989, and the new and improved OLV-DOX, now called Doxil, began clinical trials in Jerusalem in 1991.

Barenholz leaves us with a lesson anyone can learn from

The rest is history. FDA approved in 1995, the team was excited to have brought the first nanomedicine to market. Even though another research and development company approached Barenholz with a large sum of money and royalties for the rights to the early Doxil prototypes, he stuck with LTI, believing that he would have more control and success with the team there. (LTI is part of Johnson & Johnson today.)

In some of the last words of his reflective and personal review, Barenholz wrote that he wants to transfer his experience with Doxil development and eventual approval to researchers worldwide. He leaves us with an overarching lesson that anyone can learn from: collaboration is an essential part of successful science and is undervalued most of the time in the pursuit of great personal discoveries.

Prepper fertility: Family planning takes on a whole new meaning

(Credit: Salon/Ilana Lidagoster)

Valerie Landis was 33 when she froze her first set of eggs. “I had not been lucky in love,” she said. A long-term relationship begun in her early twenties had ended in her late twenties, and “approaching [her] thirties,” she thought, “I will be the candidate that will need egg freezing.”

Having worked in women’s health and fertility since her early twenties, Landis, who currently lives in Chicago, was more inclined than your average 20-something to come to this conclusion. But preparing for a future family without a partner and/or before the age of 30 is increasingly common. As women spend more time focusing on their careers and education than they do dating and family building, they’re starting to think about ways to ensure the latter can still take place down the road.

“When we started freezing eggs more than a decade ago, the average woman was in her late thirties,” said Dr. Alan Copperman, director of the Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility division at Reproductive Medicine Associates of New York, who sees higher numbers of younger patients every year. ”I think in part thanks to improvements in technology and clearly in response to social media and traditional media and celebrity endorsements, the average age continues to get lower.” In 2017, at RMA New York, the average age of female clients freezing their eggs was 35, which Dr. Copperman called “extraordinary.”

That average comes from the over 400 women who have undergone oocyte cryopreseveration at RMA New York, whose ages range from around 21 (usually women who have breast cancer or other medical diagnoses that could limit their future chances of conceiving) to forty-something. According to Dr. Copperman, 27 is the earliest age at which single women choose to freeze their eggs for elective reasons.

A number of factors contribute to younger women deciding to freeze their eggs. Better technology and lower cost are foremost among them, but what’s driving this prepper mentality is the idea that you can plan for your family in advance just as you can start early when planning for a career or retirement. In a world where parents prepare their pre-schoolers to get into Ivy League colleges, it’s not such a stretch to begin planning a family well before you’re in a position to start one.

Every woman is born with the total number of eggs she’s going to have in her lifetime, after all, and in the past few years, this fact has been resonating with younger and younger women who feel the need to control and organize more aspects of their lives — because they can.

“I know the word ‘empowered’ gets thrown around a lot,” said Copperman, “but it is in many cases empowering for a woman to control not only when she doesn’t get pregnant [via birth control] but when she does get pregnant.”

The prepper mentality isn’t just coming from young women. “What I’m finding is that parents are a huge driver of this, giving away egg freezing to their graduating daughters from college,” said Landis, especially when their daughters are entering demanding graduate programs like medical or law school. “It’s a way for parents to have a guarantee, or a chance, for them to be grandparents someday.”

* * *

Egg freezing has been around for decades, but it’s seen a gain in popularity since the development of vitrification. A flash freezing method that’s far more successful than the slow freezing technique previously used to preserve eggs, vitrification “really changed everything,” said Kristen Mancinelli, director of education at Extend Fertility. With vitrification, most frozen eggs survive once they’ve thawed — Mancinelli put the rate at about 92 percent.

Extend Fertility, a clinic in Midtown Manhattan, started as a referral service for women looking to freeze their eggs in 2004, before re-launching in 2016 to specifically accommodate women who were “thinking ahead” by exploring elective egg freezing. Having noticed a lack of services catering to “the young, healthy woman sitting awkwardly in the corner with all the couples trying to conceive” at most in-vitro fertilization clinics, said Mancinelli, the Extend team wanted to meet that growing demographic’s demand.

“The ideal age for egg freezing is between the ages of 20 to 35 years,” said Dr. Aimee Eyvazzadeh, a reproductive endocrinologist based in the Bay Area who throws egg freezing “parties” where women can learn more about the process. “I’ve been doing egg freezing parties for the past three years,” said Eyvazzadeh. “And in the beginning, many women were over 35 attending my parties. I just threw a party [with 52 attendees] and most were in their twenties or thirties.”

Egg freezing parties, similar to the Tupperware parties of yore, started gaining popularity around 2014, when Dr. Eyvazzadeh, who also goes by the moniker “egg whisperer,” started hosting hers. “For me, the whole big gimmick of the egg freezing party is not about freezing eggs; it’s only about education,” she explained. Most women don’t receive a lot of reproductive education until they’re actively trying to give birth — “here’s a condom, here’s how you put it on, good luck,” is how Landis described the extent of her school-age reproductive education — so more specialists are attempting to change this by speaking to younger women about their family planning options.

Then there are companies like Facebook, Google, and Apple, which have encouraged women to prep early for later pregnancies by covering the cost of egg freezing procedures. The tech world has been infatuated with later life prepping for some time. From strict regimens aimed at optimizing long-term health to striving for immortality, it’s not surprising the industry is facilitating this option for its employees.

Dr. Copperman encounters some of these women at his practice. “We’re seeing women who are 27 years old having these great benefits and saying, ‘Why wouldn’t I take advantage of this great opportunity? Who knows what will happen in the future?’”

And finally, there’s the increased fear of having children with developmental and cognitive disorders, which the Center for Disease Control says are on the rise. “I don’t think anyone wants to take any risks these days,” said Allison Charles, a speech-language pathologist operating in Philadelphia, of women preserving their eggs at younger ages. While she believes that what appears to be an increase in autism spectrum disorders is actually a broadening of the diagnostic criteria, to the public, it still looks “horrifying.”

“They don’t want any extra risk, such as age, to contribute to this possibility.”

* * *

Today, Valerie Landis counts herself as a “two-time egg freezer.” She underwent her second procedure when she was 35, at which time she was able to extract 13 eggs, 12 of which successfully froze. When she was 33, she was able to freeze 17 eggs.

“Earlier is better,” she said, explaining that her number of eggs declined even though she’d practiced a very healthy lifestyle those interim years, avoiding harmful activities like smoking in favor of a smoothie drinking. She currently uses her website, Eggsperience.com, and her podcast, Eggology Club, to “help inspire, teach, educate women about oocyte cryopreseveration.”

“I think of it as preventative medicine,” she said.

All-purpose, high-fidelity Bluetooth headphones on a budget

Picking the right pair of headphones can be tricky, and sometimes you need multiple pairs — a sweat-proof set for the gym, a plush pair for long plane trips and a different set for streaming your favorite tunes. Simplify with these Avantree AptX Low Latency Bluetooth Headphones, perfect for anything from gaming to movie watching to jamming out to your favorite songs.

These low latency Bluetooth headphones are perfect for any audio activity, delivering crisp treble, deep bass and superb clarity for an outstanding sound. Thanks to superior aptX audio technology, you won’t experience the lag time that sometimes happens with other Bluetooth sets — meaning your epic movie or workout session won’t be interrupted.

Set-up for headphones has never been any easier: just tap your smartphone to the headphones and they’ll automatically sync. Not into the whole wireless trend? There’s a 3.5mm line input that lets you adapt to wired audio sources. Plan on traveling this holiday season? These headphones have you covered: the ultra plush protein leather ear pads and adjustable headband are perfect for the most comfortable listening experience.

Gift yourself the audio experience you deserve: usually, these Avantree AptX Low Latency Bluetooth Headphones are $99.99, but you can get them now for $69.99. As a special offer to Salon readers, you can save an additional 15% off when you use coupon code: GIFTSHOP15 at checkout.

December 2, 2017

Monument offers glimpse of Britain’s neolithic civilization

An undated photo made available by the University of Birmingham, England, of Stonehenge where a hidden complex of archaeological monuments has been uncovered using hi-tech methods of scanning below the Earth's surface. (AP Photo/University of Birmingham, Geert Verhoeven) (Credit: AP)

This summer, the University of Reading Archaeology Field School excavated one of the most extraordinary sites we have ever had the pleasure of investigating. The site is an Early Neolithic long barrow known as “Cat’s Brain” and is likely to date to around 3,800BC. It lies in the heart of the lush Vale of Pewsey in Wiltshire, UK, halfway between the iconic monuments of Stonehenge and Avebury.

It has long been assumed that Neolithic long barrows are funerary monuments; often described as “houses of the dead” due to their similarity in shape to long houses. But the limited evidence for human remains from many of these monuments calls this interpretation into question, and suggests that there is still much to be learned about them.

In fact, by referring to them as long barrows we may well be missing the main point. To illustrate this, our excavations at Cat’s Brain failed to find any human remains, and instead of a tomb they revealed a timber hall, suggesting that it was very much a “house for the living”. This provides an interesting opportunity to rethink these famous monuments.

The timber hall at Cat’s Brain was surprisingly large, measuring almost 20 metres long and ten metres wide at the front. It was built using posts and beamslots, and some of these timbers were colossal with deep cut foundation trenches, so that it’s general appearance is of a robust building with space for considerable numbers of people. The beamslots along the front of the building are substantially deeper than the others, suggesting that its frontage may have been impressively large, monumental in fact, and a break halfway along this line indicates the entrance way.

An ancient ‘House Lannister’?

Timber halls such as these are an aspect of the earliest stages of the Neolithic period in Britain, and there seems little doubt that they were created by early pioneer Neolithic people. Frequently, they appear to have lasted only two or three generations before being deliberately destroyed or abandoned. These houses need not be dwellings, however, and given their size could have acted as large communal gathering places.

It is worth briefly pausing here and thinking of the image of a house – for the word “house” is often used as a metaphor for a wider social group (think of the House of York or Windsor, or – if you’re a Game of Thrones fan like me – House Lannister or House Tyrell).

In this sense, these large timber halls could symbolize a collective identity, and their construction a mechanism through which the pioneering community first established that identity. We may imagine a variety of functions for this building, too, none of which are mutually exclusive: ceremonial houses or dwellings for the ancestors, for example, or storehouses for sacred heirlooms.

From this perspective, it is not a huge leap of the imagination to see them as containing, among other things, human remains. This does not make them funerary monuments, any more than churches represent funerary monuments to our community. They were not set apart and divided from buildings for the living, but represented a combination of the two – houses of the living in a world saturated with, and inseparable from, the ancestors.

These houses would have been replete with symbolism and meaning, and charged with spiritual energy; even the process of building them is likely to have taken on profound significance. In this light, then, it is interesting to note that towards the end of our excavations this summer, just as we were winding up, we uncovered two decorated chalk blocks that had been deposited into a posthole during the construction of the timber hall.

The decoration on these blocks comprises deliberately created depressions and incised lines, which have wider parallels at other early Neolithic sites, such as the flint mines of Sussex.

The marked chalk blocks.

University of Reading, Author provided

Controversy often surrounds decorated chalk pieces; chalk is soft and easily marked and some people suggest that they are “decorated” with nothing more than the scratchings of badgers. But there is no doubt that the Cat’s Brain marks are human workmanship and the discovery should spark a fresh investigation into decorated chalk plaques more widely.

Imbued with power

For the moment, the original purpose of the carvings remains obscure, but clearly they were of significance. They will have had meaning and potency to the people that created them, and by depositing them in a posthole the building itself may have been imbued with that power, as well as marking it with individual or community identity. The discovery adds to the way we understand these monuments and weight to the argument that these buildings represent more than just “houses of the dead”.

Over time, deep ditches were dug either side of the timber hall at Cat’s Brain and the quarried chalk may have been piled over the crumbling building after it had gone out of use, closing it down and transforming the house from a wooden structure into a permanent earthen monument; the shape and symbolism of which will have been known to all who saw it. With this transformation, the identity of this early Neolithic group was finally and permanently inscribed upon the landscape.

Now, with this investigation, we have been granted a glimpse of the lives and beliefs of our ancestors nearly 6,000 years ago.

The excavations at Cat’s Brain, including the decorated chalk blocks, featured on “Digging for Britain” on BBC4 on Wednesday, November 22.

The excavations at Cat’s Brain, including the decorated chalk blocks, featured on “Digging for Britain” on BBC4 on Wednesday, November 22.

Jim Leary, Director of Archaeology Field School, University of Reading

How to explain “Coco’s” lessons to your kids

"Coco" (Credit: Walt Disney Studios)

“Coco” is Pixar’s vibrant, emotional film about the Day of the Dead. This tribute to Mexican traditions and customs has some sad moments, especially for those who’ve lost beloved relatives. But it also has powerful themes of perseverance, teamwork, and gratitude, and it encourages audiences to love and appreciate their family and to follow their dreams, all of which means there’s plenty for families to talk about after watching this Common Sense Seal-honored film. Try these discussion questions for kids:

Families can talk about the popularity of stories about young characters who must go on a dangerous journey to find out about themselves. What does Miguel learn in Coco? How do his experiences in the Land of the Dead help him grow?

Talk about the movie’s theme of family duty vs. personal ambition (and following your dreams). Which characters in Coco are role models, and which character strengths do they demonstrate?

Did you think any parts of the movie were scary? How much scary stuff can young kids handle? Who do you think is the ideal audience for this movie? Why?

Did you already know about the Day of the Dead? If not, what did you learn about the holiday? How does your family pay tribute to relatives and loved ones after they’ve passed away? Which other Mexican traditions and values does the movie promote? Which holidays, music, and other cultural traditions do you celebrate with your family?

Did you notice that characters speak both English and Spanish in the movie? Would you like to learn a second language? For bilingual families: Why do you think it’s important/useful to speak two languages? How does that connect you with your heritage — and your family?

“Bunk”: From P.T. Barnum to the post-truth age

Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News by Kevin Young (Credit: Graywolf Press)

These days renowned poet and cultural critic Kevin Young is one of the most reviled and dismissed of figures: He’s a learned expert on fakery. The author of “Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News” began the book six years ago, long before “fake news” became a depressingly common pejorative. But at the time, Donald Trump was well into his insistent perpetuation of the “birther” lie questioning the legitimacy of then-President Barack Obama’s birth certificate — a story concocted out of thin air that attracted millions of believers.

“I do think there’s a certain savviness to be able to recognize the way people want a good story, and I think that we underestimate that,” Young told Salon in a recent interview. “And what I call the narrative crisis of the past few decades is something that politicians have really capitalized on. You see it now all the time.

“For me, the focus is not measured by what someone intends, but by its harm and by the way that it affects us,” he added. “However you feel politically, the kind of discourse is such that it is filled with these divisions.”

To say “Bunk” feels more necessary and relevant this week would be to completely disregard the events of the week prior, and the week before that. Any given week, really, stretching back to Nov. 9, 2016. This interview was conducted within days of the Washington Post’s catching an operative from James O’Keefe’s Project Veritas attempting to insert a false story into the publication. The foiled con was intended to discredit the extensive reporting the Post has published about women coming forward to accuse Alabama Senate candidate Roy Moore of child molestation.

Days before that, Trump asked Americans to doubt their own eyes and ears by trying to deny his appearance in the famous “Access Hollywood” recording that appeared in October 2016, in which he uttered the words “grab ‘em by the pussy.”

Young had a mountain of material to work with from before all of that, evidenced in the fact that the annotations for “Bunk” required nearly 100 pages of the book. But our current battle for reality and truth strikes him as more troubling than the sideshow hoaxes of the past.

“If we think of how fake news is used, just as a term, it kind of has this double meaning,” Young said. “On the one hand, fake news is actually something that’s happened. There are stories being pushed out, whether it’s ‘Pizzagate’ or the ‘bots who infiltrated the last election and pushed out fake, targeted information. That’s a real thing that happened, and a troubling one. At the same time fake news becomes, and Trump employs it this way, an epithet used against news one doesn’t like. Both are troubling in their own way.”

The fact that “Bunk” consists of 576 pages, including 20 photographs from traveling sideshow exhibits, illustrations of supposed societies living on the moon and other assorted fraudulent hokum, should tell you just how much fakery is part of our shared history.

But if not for the accelerated rate of information dispersal in the modern age, the book would have been shorter by around 70 pages. “I thought I’d nearly finished this book — filled with hoaxers and impostors, plagiarists and phonies,” he writes near the opening of chapter 19, “but as soon as I had sent a draft to my publisher, elated and relieved, Rachel Dolezal raised up her faux-nappy head. Now I have to take time to write about her too?”

Young is primarily known as a poet and his first major work of nonfiction prose, 2012’s “The Grey Album: On the Blackness of Blackness,” joined a body of work that includes 10 books of poetry. In addition to his role as poetry editor of the New Yorker, he’s also the director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

“Bunk” represents the culmination of Young’s fascination with story, history and culture, and it is without question a poetic take on a difficult, fraught topic. The book’s density is in its language as well as its breadth, as Young engages with the mind-reeling nature of the subject matter by lyrically connecting irrefutable fact to astounding fictions, illustrating many times over the power hoaxing has to defy logic and reason.

“Poets often are dealing with history and are thinking about the way history moves across us, and we move in it,” Young explained. “Certainly the poets I love do that in different ways. Even the idea of an epic, Ezra Pound’s definition of an epic is a poem containing history.

“I’m not a historian,” Young continued. “I know historians. I’ve worked with them. They have a really powerful way of looking at the world, and I think so do poets. And we have a way, I think, of making connections and thinking about them. I think it is a poet’s book. I hate to say that, but I do think it has those kinds of leaps and connections that I think, I find in good poetry.

Dolezal, unfortunately for Young, is a stanza that snugly fit into the epic he’d already built; she’s a tremendous example of what Young describes as the hoax’s ability to “plagiarize pain.”

In “Bunk,” Young traces the current bamboozlement effectuated by the flimflam artists on Capitol Hill and in the White House back to P.T. Barnum and one of his earliest greatest shows, an act starring a black woman named Joice Heth. In 1835, Barnum claimed Heth, who may have been his slave, was George Washington’s nursemaid. This would have made Heth more than 161 years old.

The act was as wildly popular as the penny press’s perpetuation of a hoax that convinced the public that a scientist (who wasn’t actually a scientist and, indeed, did not truly exist) had viewed fantastic creatures living on the surface of the moon.

All of this is captured in the first chapter of “Bunk,” titled “The Age of Imposture.” Through the many pages following, Young traces our culture’s embrace of hoaxing from the past through the present, from sideshows through spiritualism, from the earliest works of science fiction through fabricated tales masquerading as journalistic pieces and memoirs revealed to be pure fiction.

“When I started, I thought these things would be true six years ago, and then they came more and more true in our current era, in a sense,” he said. “And the more I’ve gone around and thought about it, the more the analogies between what was happening in 1835 with Barnum, and the Moon Hoax or blackface, which was invented then, and I’ve never heard anyone try to connect blackface to this hoax tradition. And pseudoscience, too. All those things were happening almost literally to the year in the mid-1830s.”

Not only does he name many of the fakers who made headlines for making up stories — Lance Armstrong, Ruth Shalit, Jayson Blair, James Frey, the gang’s all here! — he calls back to a depressing refrain about the basis for fakeouts past, present and likely future. All of them are based in our country’s obsession and fear about race and racial stratification. Indeed, Young also explores the way that the very concept of race and the categorizations that are with us to this day are completely made up.

“It’s not an accident that the [social media] bots from the last election were racialized or fake radicals, fake black groups,” he said. “All this kind of stuff, I’m sad to say, is very much in the tradition of the hoax.”

Barnum’s presence hovers throughout the book like a specter until “Bunk” arrives at its conclusion — “The Age of Euphemism,” the post-fact world we’re living in now. Days before Trump’s inauguration, he points out in “Bunk,” the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey circus shut down forever.

“The elephant in the room,” he writes, “is that what people say they want, and what they are willing to pay for, are often at odds.”

Now there’s some cold hard truth in a post-truth age.

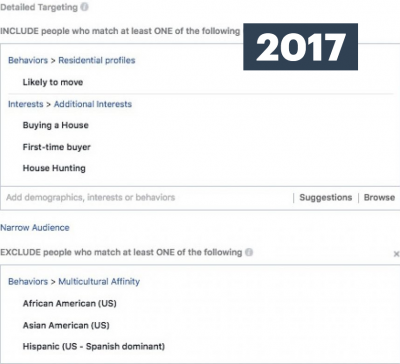

ProPublica: Why we had to buy racist, sexist, xenophobic, ableist, and otherwise awful Facebook ads

(Credit: Shutterstock)

Last week, we bought more than a dozen housing ads excluding categories of people explicitly protected by the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

Last week, we bought more than a dozen housing ads excluding categories of people explicitly protected by the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

Were these actual ads? No. And as someone who’s spent the past month on a New York City apartment hunt, I’m pretty confident that no one would mistake our “real estate company” for an actual brokerage.

But here’s the question: could they have been real? Yes — and our ability to limit the audience by race, religion, and gender — among other legally protected attributes — points to the same problem my colleagues Terry Parris Jr. and Julia Angwin reported out a year ago, exciting much outrage from people who care about fixing discriminatory housing practices. Here’s what they tested last year:

Their work put Facebook on the defensive. It put out a statement that “discriminatory advertising has no place on Facebook.” In February, the company announced that it had launched a system to catch problematic housing ads and “strengthen enforcement while increasing opportunity on Facebook.” Meanwhile, Facebook has amped up its efforts on real estate this year. You can see housing ads all over Marketplace, a slick Craigslist-like section of the site. Facebook recently partnered with real brokers at Zumper and Apartment List, and it has announced it will be rolling out new features over the coming months. With that in mind — and fresh off our other Facebook ad portal investigation into “Jew haters” — we wanted to know whether it had actually fixed the problem. So we more or less repeated the exercise:

Our ads skated right through the approval process. Again. Approved in under two minutes. It wasn’t just this ad. We also managed to buy ads excluding users based on religion, family status, national origin, sex, race, ability, and more — every group that’s supposed to be protected under major housing laws. Facebook apologized profusely for what it called “a technical failure,” and promised — again — to strengthen its policies and hire more reviewers. I want to answer a question that has been posed by quite a few people on social media in response: Why would ProPublica take out discriminatory ads?

Sure, Facebook, who’s surprised? But what the heck is up with ProPublica?!

— Mary Christopher (@MaryChr01644671) November 21, 2017

It’s a fair question. Let’s be clear: we don’t take the decision to buy a fake ad for non-existent housing lightly, and it is against our newsroom’s policy to impersonate for the sake of newsgathering. But there was no other way for us to test the fairness of Facebook’s ads. And our disturbing findings suggest that, even if Facebook has the best intentions and just overlooked a technical glitch, somebody on the outside has to watch its advertising platform more closely than it seems to do itself.

We had a lot of conversations internally about the best and most ethical ways to do this. Here’s how our editor-in-chief Stephen Engelberg puts it:

“Social networking platforms like Facebook are enormously powerful in shaping the modern world. In this instance, we viewed the public interest in testing its promises about discriminatory advertising as sufficiently important that it outweighed the possibly detrimental effect. Remember, we canceled these ads as soon as they were accepted so that the likelihood they would be seen by anyone was remote. In our judgment, placing this ad was far less deceptive than a reporter posing as someone else, a practice we continue to bar under virtually all imaginable circumstances.”

Meanwhile… if you see any eyebrow-raising ads or advertising categories on your Facebook feed this shopping season, let us know. We’re gathering political ads, and we want to stay on top of ads for housing, employment and credit as well. Clearly, this is a story that requires persistence.

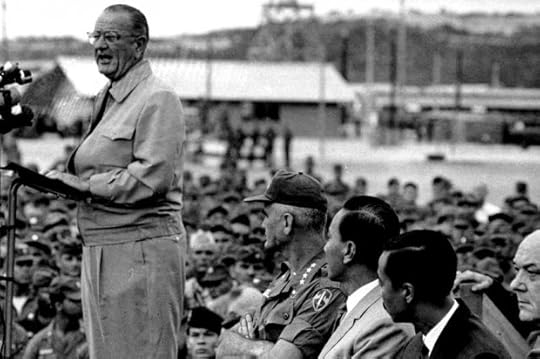

Lyndon Johnson in Vietnam: The turning point of the ’60s

President Johnson stands before american Troops at Cam Ranh Bay while visiting South Vietnam, Oct. 26, 1966. (Credit: AP)

The great nocturnal invasion of American homes began at dusk on a Monday evening in October 1966 along the East Coast and spread inexorably westward during the next three hours. For the 187 million Americans living in the United States, the invasion centered around strange creatures almost universally smaller than an average adult human being. These miniature creatures dressed in bizarre clothing depicting other times, other places, even other dimensions. Miniature females sought entry into homes dressed as pint-sized versions of America’s favorite women with supernatural powers—Samantha Stevens of “Bewitched,” or, as the companion/servant/nightmare of an American astronaut, a being from a bottle known as “Jeannie,” played by Barbara Eden. Diminutive male invaders often wore the green face of bumbling giant Herman Munster or the pointed ears of the science officer of the USS Enterprise, Mr. Spock. These miniature invaders were sometimes accompanied by still youthful but taller adolescents who may or may not have worn costumes as they chaperoned their younger siblings but invariably seemed to be holding a small box equipped with earplugs that allowed these teens to remain connected to the soundtrack of their lives, the “Boss Jocks” or “Hot 100” or “Music Explosion” radio programs.

These teenagers were different forms of invaders in the adult world of late 1966, as they seemed semipermanently attached to their transistor radios, spending four, six, or even eight hours a day listening to rapid-fire disc jockeys who introduced, commented upon, and played current hits such as “Last Train to Clarksville” by the Monkees, “96 Tears” by ? and the Mysterians, “Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow?” by the Rolling Stones, and “Reach Out I’ll Be There” by the Four Tops.

As the miniature “home invaders” were often invited by their “victims” into their living rooms to receive their candy “payoffs,” they encountered adults watching “The Lucy Show,” “Gilligan’s Island,” “The Monkees” and I Dream of Jeannie. The fact that nearly half of Americans in 1966 were either children or teenagers made it extremely likely that at least one or possibly even two of the programs airing on the three major networks would feature plotlines attractive to youthful viewers.

The most famous home that received the costumed “invaders” was 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. Three years earlier that address had featured two young children as its residents, but the current residents were now looking forward to becoming first-time grandparents after the recent wedding of their daughter. While Lady Bird Johnson welcomed the diminutive visitors who passed through far more security than average homes, President Lyndon Baines Johnson was recovering from the massive jet lag and exhaustion incurred during a recent 10,000-mile odyssey across the Pacific Ocean.

A few days before Halloween, Lyndon Johnson had become the first president since Franklin Roosevelt to visit an active battle zone by traveling to a war-torn South Vietnam. While a quarter century earlier Roosevelt had been ensconced in the intrigue-laden but relatively secure conference venue of Casablanca, Johnson’s Air Force One had engaged in a rapid descent toward Cam Ranh Bay in order to minimize the time the president could be exposed to possible Viet Cong ground fire.

Johnson, dressed in his action-oriented “ranch/country” attire of tan slacks and a matching field jacket embossed with the gold seal of the American presidency, emerged from the plane with the demeanor of a man seeking to test his mettle in a saloon gunfight. Standing in the rear of an open Jeep, the president clutched a handrail and received the cheers of seven thousand servicemen and the rattle of musketry down a line of a nine-hundred-man honor guard. Meanwhile, a military band played “The Yellow Rose of Texas.” Johnson’s speech—considered by many observers to have been his best effort in three years in office—compared the sweating suntanned men in olive drab fatigues to their predecessors at Valley Forge, Gettysburg, Iwo Jima, and Pusan. He insisted that they would be remembered long after by “a grateful public of a grateful nation.”

Now, at Halloween, Johnson had returned to the White House, more determined than ever to (in his sometimes outlandish “frontier speak” vocabulary) “nail the coonskin to the wall” in concert with a relatively small but enthusiastic circle of allies, including Australia, South Korea, the Philippines, and Thailand. All were dedicated to thwarting a Communist takeover of South Vietnam and possibly much of Southeast Asia. While European allies had decided to sit out this conflict, Johnson had been able to forge an alliance in which young men from Melbourne, Seoul, and Manila were joining American youths from Philadelphia to San Diego in a bid to prevent North Vietnam and its Viet Cong allies from forcibly annexing a legitimate but often badly flawed South Vietnamese entity.

Unlike Halloween of 1942, when even the youngest trick-or-treaters had some semblance of knowledge that their nation was involved in a massive conflict that even affected which toys they could buy, what was for dinner, or whether they would have the gasoline to visit their grandparents, the United States in October 1966 displayed little evidence that a war was on. Neighborhood windows did not display blue or gold stars signifying war service. Dairy Queen stands did not run out of ice cream due to a sugar shortage, McDonald’s restaurants were in the process of offering even larger hamburgers than their initial 15-cent versions, and there were no contemporary cartoon equivalents of the Nazi-Japanese stereotypes in the old Popeye and Disney cartoons. In October of 1966, “The War” still primarily referenced the global conflict of a generation earlier. Names such as Tet, Hue, My Lai, and Khe San were still obscure words referenced only as geographical or cultural terms by a minority of young soldiers “in the country” in South Vietnam.

Halloween 1966 was in many respects a symbolic initiation of the long 1967 that my new book, “1967,” will chronicle. Post-World War II American culture had gradually chipped away the edges of the traditional January 1 to December 31 annual calendar. Nearly sixty million American students and several million teachers had begun the 1967 school year in September as they returned to classes in a new grade. The burgeoning television industry had essentially adopted the same calendar, as summer reruns ended soon after children returned to school, so that the 1967 viewing season began several months before New Year’s Day. Car manufacturers began discounting their 1966 models in the autumn as new 1967 autos reached the showroom far ahead of calendar changes. While the college basketball season did not begin until December, about three weeks later than its twenty-first-century counterpart, the campaigns for the National Hockey League 1967 Stanley Cup and the corresponding National Basketball Association Championship title began far closer to Halloween than New Year’s Day. This reasonable parameter for a chronicle of 1967 would seem to extend roughly from late October of 1966 to the beginning of the iconic Tet Offensive in Vietnam during the last hours of January 1968.

While the undeclared conflict in Vietnam had not yet replaced World War II as the war in many Americans’ conscious thought, no sooner had the president returned from Southeast Asia than a new threat to Johnson’s presidency emerged. Since his emergence as chief executive in the wake of the Kennedy assassination three years earlier, Johnson had driven a balky but Democratic-dominant Congress to one of the most significant periods of legislation activity in the nation’s history. Bills enacting civil rights legislation, aid to schools, public housing subsidies, highway construction, space exploration, and numerous other projects wended their way through Congress, often in the wake of the president’s controversial treatment of uncommitted lawmakers through a combination of promises and goadings. By the autumn of 1966, supporters and opponents of the Johnson’s Great Society began to believe that, for better or worse, the president was beginning to envision a semipermanent social and political revolution in which current laws would be substantially enhanced while new reforms xvi prologue autumn were proposed and enacted. However, a week after Halloween, this prospect collided with a newly emerging political reality.

The Goldwater-Johnson presidential contest two years earlier had not only resulted in the trouncing of the Arizona senator, but essentially provided the Democrats with a two to one majority in both houses of Congress. While some northern Republican lawmakers were more politically and socially liberal than a number of Southern Democrats, party discipline still obligated these southern politicians to support their leader. At least in some cases, the Great Society legislation kept churning out of the Congress, notably with the startling 100 to 0 Senate vote for the 1965 Higher Education Act. Now, as Americans voted in the 1966 elections, the seemingly semi-moribund GOP came back dramatically from its near-death experience.

When the final votes were tallied, the Republicans had gained eleven governorships that added to the fifteen they already held, which now meant that the majority of states were led by a GOP chief executive. The relatively modest party gain of three Senate seats was overshadowed by a spectacular increase of forty-seven seats in the House of Representatives, which more than repaired the damage of the 1964 fiasco. Newspapers and news magazines featured stories purporting that “the GOP wears a bright new look.” Politics in ’66 sparkled the political horizon with fresh-minted faces, and the 1966 election has made the GOP presidential nomination a prize suddenly worth seeking. The cover of Newsweek displayed “The New Galaxy of the GOP” as “stars” that “might indeed beat LBJ in 1968.”

This cover story featured George Romney, “the earnest moderate from Michigan”; Ronald Reagan, “the cinegenic conservative from California”; and other rising stars of the party. Edward Brooke, the first African American US senator since Reconstruction, “Hollywood handsome” Charles Percy from Illinois, Mark Hatfield of Oregon, and even the newly energized governor of New York, Nelson Rockefeller, were all mentioned. Notably absent from this cover story “galaxy” was the man who easily could have been in the White House in autumn 1966, Richard M. Nixon. According to the news media, the former vice president’s star seemed to be shooting in multiple directions. One article dismissed him as “a “consummate” old pro “who didn’t win anything last week and hasn’t won on his own since 1950,” while another opinion held that the Californian had emerged as “the party’s chief national strategist” as he urged the formula of running against LBJ and in turn most accurately predicted the results.

All around the nation, analysis of the 1966 election supplied evidence that the Democratic landslide of two years earlier was now becoming a distant memory. Only three Republican national incumbents running for reelection lost their races across the entire nation. Republicans now held the governorships of five of the seven most populated states. Romney and Rockefeller had secured 34 percent of the African American vote in their contests, and Brooke garnered 86 percent of the minority vote in his race.

While the GOP had lost 529 state legislature seats in the legislative fiasco of 1964, they had now gained 700 seats, and a Washington society matron described the class of new Republican legislators as “all so pretty” due to their chiseled good looks and sartorial neatness—“there is not a rumpled one in the bunch.” Good health, good looks, and apparent vigor seemed to radiate from the emerging leaders of the class of 1966.

George Romney, newly elected governor of Michigan, combined his Mormon aversion to tobacco and spirits with a brisk walk before breakfast to produce governmental criticism of the Vietnam War that caught national attention. His Illinois colleague, Senator Charles Percy, was described as a “Horatio Alger” individual, a self-made millionaire with the “moral fibers of a storybook character.” The equally photogenic Ronald Reagan looked a good decade younger than his birth certificate attested, and alternated stints in his government office with horseback riding and marathon wood-chopping sessions. All of these men were beginning to view 1967 as the springboard for a possible run at the White House, especially as the current resident of that dwelling seemed to be veering between a brittle optimism and a deep-seated fear that the war in Southeast Asia was about to unravel the accomplishments of his Great Society.

While the new galaxy of emerging Republican stars was reaping widespread public attention after the election of 1966, two men who had come closer to actually touching the stars were gaining their own share of magazine covers and media attention.

James Lovell and Buzz Aldrin spent part of late 1966 putting exclamation points on Project Gemini, the last phase of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s plan to fulfill John F. Kennedy’s challenge to land Americans on the moon before the 1960s ended. One of the iconic photos of late 1966 occurred when Lovell snapped a photo of Aldrin standing in the open doorway of their Gemini spacecraft, with the Earth looming in the background. James Lovell Jr. and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin were marking the end of the run-up to the moon that had been marked by the Mercury and Gemini projects and which were now giving way to the Apollo series, which would eventually see men setting foot on the moon.

Journalists in late 1966 chronicled the sixteen astronauts who traveled eighteen million miles in Earth orbits as participants of “Project Ho-Hum,” or engaged in clocking millions of miles with nothing more serious than a bruised elbow.”

Life columnist Loudon Wainwright compared the almost businesslike attitude of both the astronauts and the American public in 1966 to six years earlier, when citizens waited anxiously for news of a chimpanzee who had been fired 414 miles out into the Atlantic. They admired its spunk on such a dangerous trip, then prayed for Mercury astronauts who endured the life-and-death drama of fuel running low, hatches not opening properly, and flaming reentries that seemed only inches from disaster. Now, in 1966, James Lovell, who had experienced eighty-five times more hours in space than John Glenn a half decade earlier, could walk down the street virtually unnoticed. By late 1966, American astronauts seemed to be experiencing what one magazine insisted was “the safest form of travel,” but only days into the new year of 1967 the relative immunity of American astronauts would end in flames and controversy in the shocking inauguration of Project Apollo.

Late 1966 America, to which Lyndon Johnson returned from Vietnam and James Lovell and Buzz Aldrin returned from space, was a society essentially transitioning from the mid-1960s to the late 1960s in a decade that divides, more neatly than most, into three relatively distinct thirds. The first third of this tumultuous decade extended roughly from the introduction of the 1960 car models and the television season in September of 1959 and ended, essentially, over the November weekend in 1963 when John F. Kennedy was assassinated and buried.

This period was in many respects a transition from the most iconic elements of fifties culture to a very different sixties society that did not fully emerge until 1964. For example, the new 1960 model automobiles were notable by their absence of the huge tail fins of the late 1950s, but were still generally large, powerful vehicles advertised for engine size rather than fuel economy. Teen fashion in the early sixties morphed quickly from the black leather jacket/poodle skirts of Grease fame to crew cuts, bouffant hairdos, penny loafers, and madras skirts and dresses. Yet the film “Bye Bye Birdie,” a huge hit in the summer of 1963, combined a very early sixties fashion style for the teens of Sweet Apple, Ohio, with a very fifties leather jacketed and pompadoured Conrad Birdie in their midst.

Only months after “Bye Bye Birdie” entered film archives, the mid-sixties arrived when the Beatles first set foot in the newly named John F. Kennedy airport in New York, only a few weeks after the tragedy in Dallas. As the Beatles rehearsed for the first of three Sunday night appearances on “The Ed Sullivan Show,” boys consciously traded crew cuts for mop-head styles and teen girls avidly copied the styles of London’s Carnaby Street fashion centers. By summer of 1964, “A Hard Day’s Night” had eclipsed Birdie in ticket sales and media attention.

While the early sixties were dominated by the splendor and grandeur of the Kennedy White House, the wit and humor of the president, the effortless style of Jacqueline Kennedy, and the vigor of a White House of small children, touch football, and long hikes, the mid-sixties political scene produced far less glamour in the nation’s capital. Ironically, Lyndon Johnson was far more successful in moving iconic legislation through a formerly balky Congress, yet the Great Society was more realistic but less glamorous than the earlier New Frontier. While the elegantly dressed Jack and stunningly attired Jackie floated through a sea of admiring luminaries at White House receptions, Johnson lifted his shirt to display recent surgery scars and accosted guests to glean legislative votes while the first lady did her best to pretend that her husband’s antics had not really happened.

Much of what made mid-sixties society and culture fascinating and important happened well outside the confines of the national capital. Brave citizens of diverse cultures and races braved fire hoses and attack dogs in Selma, Alabama, to test the reach of the Great Society’s emphasis on legal equality, while television networks edged toward integrating prime-time entertainment. Those same networks refought World War II with “Combat,” “The Gallant Man,” “McHale’s Navy,” and “Broadside.” James Bond exploded onto the big screen with “From Russia With Love,” “Goldfinger,” and “Thunderball,” and the spy genre arrived on network television with “The Man from U.N.C.L.E.,” “Get Smart,” and even “Wild, Wild West.”

The mid-sixties soundtrack rocked with the sounds of Liverpool and London as the Beatles were reinforced by the Rolling Stones, the Zombies, the Kinks, the Troggs, and the Dave Clark Five. American pop music responded with Bob Dylan going electric with “Like a Rolling Stone” and the Beach Boys’ dreamy “Pet Sounds.” Barry McGuire rasped out the end of civilization in “Eve of Destruction,” while the Lovin’ Spoonful posed a more amenable parallel universe with “Do You Believe in Magic?”