Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 198

December 26, 2017

Trump is mad at Jeff Sessions for taking the job Trump offered him

Jeff Sessions; Donald Trump (Credit: Getty/Win McNamee)

The Trump administration experienced perhaps its roughest stretch during July 2017, when Trump and company stared down legislative and judicial defeats, major staff shake-ups and the lingering investigation into Russian collusion.

From the hiring (and firing) of former White House communications director Anthony Scaramucci, the departure of former White House Chief of Staff Reince Priebus, the home of President Donald Trump’s former campaign manager Paul Manafort being raided by the FBI, or the devastating health care defeat delivered by Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., the Trump White house looked as bleak as ever.

On July 26, one week prior to the FBI raid of Manafort’s house, Trump was seething with anger over the Russia investigation and how it dominated headlines, the Associated Press reported. Trump ripped into Attorney General Jeff Sessions for recusing himself from the ongoing Russia probe.

Though Sessions was one of the first mainstream Republicans to back Trump’s presidential bid, the relationship between the two reportedly strained around July. Incredibly, Trump went so far as to blame Sessions “in part” for the Alabama Senate special election loss Republicans suffered in early December, the AP reported — even though the senate vacancy was a direct result of Trump appointing then-Senator Jeff Sessions to Attorney General.

The AP reported, with no hint of irony:

… the rift between Trump and Sessions still has not healed. Recently, Trump bemoaned the Republicans’ loss in a special election in Alabama and in part blamed Sessions, whose departure from the Senate to head to Justice necessitated the election.

Several other incidents in July contributed to a massive White House shake-up and led to the ushering in of current Chief of Staff John Kelly, who has attempted to control and tamp down the flow of information to the White House.

Before Kelly began, Trump complained about then–White House press secretary Sean Spicer, and said he wasn’t doing a good job of defending him and did not “look the part,” the AP reported. So Trump brought in Anthony Scaramucci, “a rich, fast-talking New York hedge fund manager who excelled on television.” Reportedly, the president saw a mirror of himself in Scaramucci. Spicer quit hours after the White House hired Scaramucci.

What followed was perhaps the height of known White House internal conflict: a battle between Scaramucci and Priebus, in which Scaramucci promised to punish leakers. Both Scaramucci and Priebus would depart from the White House shortly thereafter.

Following Scaramucci’s expletive-filled interview with the New Yorker, Trump had enough. He “was unwilling to share the spotlight with an aide, and came to believe Scaramucci had forgotten his place,” the AP reported.

Trump also struggled to adhere the advice of Defense Secretary James Mattis and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, following a July 20 meeting in a room in the Pentagon known as “The Tank,” the AP reported. Trump resisted a surge of troops in Afghanistan, but eventually caved. The meeting, if anything, “also revealed the tensions within the administration between those from Washington’s national security establishment and those eager to pull back from international entanglements.”

The defeat of GOP health care efforts helped make July a devastating month for the Trump presidency. But the loss allowed the GOP and the White House to craft a strategy that eventually mustered up enough votes — albeit with 12 days to spare before the end of the year — to deliver Trump his first major legislative achievement.

With almost a full year in the books, the Trump presidency mostly stumbled and been bogged down by numerous scandals or incendiary unilateral decisions. The year will soon end, but more is sure to follow.

US to slash UN budget by more than $285 million after Israel vote

(Credit: AP Photo/Richard Drew)

The U.S. hasn’t been too generous to the United Nations this holiday season.

Following negotiations, the United States has announced it will slash budget obligations to the United Nations in 2018-2019 by more than $285 million, as the move has been looked at as an attempted show of strength by the Trump administration to those who oppose U.S. policy positions.

“The inefficiency and overspending of the United Nations are well known,” Nikki Haley, the U.S. ambassador to the U.N., said in a statement from the U.S. Mission on Sunday. “In addition to these significant cost savings, we reduced the U.N.’s bloated management and support functions, bolstered support for key U.S. priorities throughout the world, and instilled more discipline and accountability throughout the U.N. system.”

The statement continued, “We will no longer let the generosity of the American people be taken advantage of or remain unchecked. This historic reduction in spending – in addition to many other moves toward a more efficient and accountable U.N. – is a big step in the right direction.”

The U.S. is responsible for 22 percent of the U.N.’s operating budget, roughly $1.2 billion for 2017-2018, and is also responsible for 28.5 percent of peacekeeping operations under the U.N. charter, The Guardian reported.

But the announcement comes a week after Haley said the U.S. would “” in the lead up to the U.N. General Assembly’s vote, in which countries then overwhelmingly condemned President Donald Trump’s decision to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel.

Prior to the U.N. vote last week, Trump said at a cabinet meeting, “Let them vote against us,” The Guardian reported.

“We’ll save a lot. We don’t care. But this isn’t like it used to be where they could vote against you and then you pay them hundreds of millions of dollars,” Trump continued. “We’re not going to be taken advantage of any longer.”

Trump has, for the most part, been criticized for his Israel decision, but he repeatedly railed on the U.N. during his campaign as being far too dependent on U.S. funds. The timing of the budget cuts makes it clear that the Trump administration is willing to harm the standing of the U.N. — by cutting its contributions — so long as other nations stand opposed to U.S. decisions.

This latest Trump administration move is being called “just insane”

(Credit: AP Photo/Tanya Bindra, File)

MSNBC’s Joy Reid is fed up with the Trump administration and believes that while some of the administration’s decisions are “awful,” others are simply “just insane.”

Some of the things they do are awful. And some are just insane. https://t.co/x2mYPb7V33

— Joy Reid (@JoyAnnReid) December 26, 2017

Reid had made reference to a recent report that the U.S. government lifted a moratorium imposed in 2014, which ended the funding of research that alters viruses in order to make them more lethal, as well as transmissible.

Some scientists have argued that they will now be able to use this research to potentially demonstrate “how a bird flu could mutate to more easily infect humans, or could yield clues to making a better vaccine,” The New York Times reported.

Critics, however, have expressed that experimenting with dangerous viruses could lead to serious risks, such as a widespread outbreak.

The Times elaborated:

Now, a government panel will require that researchers show that their studies in this area are scientifically sound and that they will be done in a high-security lab.

The pathogen to be modified must pose a serious health threat, and the work must produce knowledge — such as a vaccine — that would benefit humans. Finally, there must be no safer way to do the research.

The moratorium was originally placed on three diseases in Oct. 2014, which halted 21 projects and included the flu, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory system (SARS), the Times reported. This means that scientists were prohibited from making those viruses more deadly. Exceptions have been made for 10 of those projects in the years since the moratorium.

New regulations, however, apply to any and all pathogens, which could include, for example, “a request to create an Ebola virus transmissible through the air.”

Richard H. Ebright, a molecular biologist and bioweapons expert at Rutgers University, criticized the research efforts and said, “There’s less than meets the eye,” the Times reported.

Ebright felt the need for a panel review was necessary but explained he’d rather have independent reviews than ones conducted by the government, the Times reported. Ebright also said the rules should apply to all work and not just government-funded research and “clearer minimum safety standards and a mandate that the benefits ‘outweigh’ the risks instead of merely ‘justifying’ them.”

Why does Times Square drop a ball on New Year’s Eve?

(Credit: Getty/Dimitrios Kambouris)

Billions of people worldwide will be signaling the start of 2018 in less than a week on New Year’s Eve, by staring with great anticipation at a big glowing ball slowly dropping. Why do we do this? What is the history behind this tradition and what the heck is a “time ball” anyway?

According to the Times Square website, New Yorkers started celebrating New Year’s Eve in Times Square as early as 1904, partly thanks to Adolph Ochs, the publisher of the New York Times — which, in turn, was the namesake for Times Square. Ochs began scheduling fireworks to kick off the new year in 1904, to celebrate the inaugural year of The New York Times’ new location, but the city banned the fireworks by 1907. He had to find a better approach.

Enter the “time ball.”

Historically, time balls had nothing to do with New Year’s Eve. They had more to do with practical work than with celebration. In the 1800’s, before official time zones were in place, ships’ captains would use something called a chronometer to keep track of time. It was basically a big pocket watch, but seas get rough and sometimes inaccuracies arose from the delicate device losing its levels. If the device wasn’t calibrated, captains might lose track of their speeds or “going-rates” and risk being mired by large fish shoals that would slow down their trip.

England found a solution, allotting a specific time every day for sailors to essentially “sync their watches,” as we would do today. At 1:00 p.m., a ball would drop from a coastal naval observatory, that captains could see from their ships. The first one was installed at England’s Royal Observatory at Greenwich in 1833. Now captains would be able to set their chronometers more accurately.

When Ochs was looking for a replacement symbol of celebration when his firework plans were dashed, he spared no expense and arranged a bright, 700-pound time ball of iron and wood to be lowered from the tower of the Times building at midnight to ring in 1908. Now all those watching would know when New York officially began the new year. Times Square will continue this tradition for the 110th time on Sunday night.

December 25, 2017

The biggest labor stories of 2017

(Credit: AP Photo/Erik Schelzig, file)

The first year of any Republican presidential administration is sure to bring new attacks on unions and their allies. This year has seen plenty of anti-labor offensives, as well as inspiring fights and encouraging signs for the future.

The first year of any Republican presidential administration is sure to bring new attacks on unions and their allies. This year has seen plenty of anti-labor offensives, as well as inspiring fights and encouraging signs for the future.

Let’s start with the most over-blown “fake news” labor story of 2017: the asinine notion that Donald Trump has a cunning plan to cleave white working-class voters away from the Democratic party by protecting American jobs and giving unions a fair shake. From the coalmines of West Virginia to the Carrier plant of Indiana, Trump’s claims of saving jobs have been spectacles of hucksterism that resulted in fewer good jobs.

His invitation of building-trades leaders to the White House in his first week on the job—once seen as a canny exploitation of union leaders’ simmering resentment towards Democratic party indifference—is now understood as the gesture of a clueless buffoon struggling vainly to treat his new job like his business ventures. “Let’s bring in a few dealmakers and talk about construction projects,” he probably thought. “Maybe they have some good suggestions for how my idiot son-in-law might go about bargaining for peace in the Middle East.”

Meanwhile, his Department of Labor and National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) appointments, and the speed with which they are reversing any gains that workers made under the Obama administration, are all bog-standard right-wing moves. The official labor policies of the Trump administration are exactly the same as would have been Jeb Bush’s or Mitt Romney’s.

But workers refuse to wait until Trump is impeached, voted out or felled by his nauseatingly unhealthy diet. The year was marked by some impressive organizing campaigns that offer hope for the future.

Beating Trump in the rebel cities

Some of the most strategic organizing of this Trump moment has been focused on winning real gains for workers where we can: in our rebel cities and blue states. Alt-labor organizations have been leading this fight.

The Fair Workweek Initiative has been fighting the mostly non-union retail, fast-food and other minimum wage service industries that have kept their employees virtually on-call through abysmal short-staffing policies. From New York City to the entire state of Oregon, workers won new laws in 2017 that force employers to post work schedules at least one week in advance, pay workers surcharges for last-minute changes and abolish the prevalent practice of scheduling workers for “clopens” (working a first shift the morning after closing up).

The New York City fair scheduling ordinance was part of a comprehensive labor law passed by the city council in May. One part that will be watched closely by union allies and haters alike is a requirement that fast-food establishments create a mechanism to allow employees to make voluntary contributions from their paychecks to a qualified nonprofit to provide services and advocacy on their behalf.

This is dues check-off for Fight for $15, and that is amazing.

One of the biggest challenges for alt-labor is funding the work. Collecting voluntary membership dues from more than a few hundred of your most hardcore supporters is a massive challenge if you don’t have access to payroll deductions. Without those deductions, a union or workers center is relying on auto-renewing credit card contributions or Automated Clearing House direct deposit arrangements with members’ checking accounts.

Speaking from experience, even teachers bounce checks and miss credit card payments with distressing regularity in our new age of inequality.

If New York City’s voluntary-for-workers-but-legally-mandated-for-employers dues check-off system helps Fight for $15 find a sustainable funding stream, it will be a model for other rebel cities and eventually for federal legislation.

Also of note is the return of the big May 1 “Day Without Immigrants” protests that first rocked the country in 2006, this time as an obvious rebuke to our racist president. Not nearly enough attention was paid to the fact that in the midst of the May Day actions, immigrant workers and small business owners shut down the small city of Reading, Pa. in a general strike. The action was organized by Make the Road PA. In the endless organizing debates about the value of going wider vs. deeper with community organizing, Make the Road’s impressive action is a powerful example of what can be done with scant resources but long-term commitments in working-class communities.

The Empire strikes back

In July, the Trump administration officially abandoned Obama’s effort to double the minimum pay that salaried employees should legally be paid. That effort was spear-headed by Tom Perez, the most dogged Labor Secretary we’ve seen in half a century. It aimed to raise the wage of overworked employees classified as “professionals” and “supervisors” by corporations seeking to avoid paying overtime to the still-insufficient sum of $47,476. Many corporations—Walmart most prominently—raised their middle ranks’ pay in anticipation of the new rule. Fortunately, few companies have rescinded those raises now that they are no longer legally obligated to pay (probably out of fear of mass resignations and lawsuits).

Two months after this effort was ditched, the Supreme Court agreed to hear a lazy remake of a bad sequel of an attempt to force public sector unions to go “right-to-work” that had seemingly died along with Antonin Scalia. The new case, Janus vs. AFSCME, is wrong on facts and legal precedent. But it has the benefit of a stolen Supreme Court seat—and the blessing of the U.S. government, which has filed an amicus brief against the very concept of a strong labor movement.

More recently, the right-wing hack who Trump appointed to befoul the former office of Tom Perez declared his intent to restrict and over-regulate workers centers as if they were statutorily-recognized unions. This is an attempt to silence these shoestring budget organizations by making their boycott activities punishable by crippling multi-million dollar fines. As Sharon Block writes, it’s a back-handed compliment that corporate interests see these alt-labor groups as a threat to their agenda. It also shows why we need a new Labor’s Bill of Rights.

New hope in the private sector

Workers in the private sector continue to organize. Even where there are notable successes, there are also challenges related to how badly any Republican president can damage the legal paths to justice for workers.

Responding to tumultuous changes in their industry, journalists and other content producers for major media companies have been organizing at a rapid-fire pace. Journalists at Salon, The Intercept, Thrillist and Vox, video writers at Vice, and editorial producers at MTV News all organized with the Writers Guild of America East this year. Meanwhile, the reporters at the Los Angeles Times—long a bastion of anti-unionism—organized with the News Guild.

But, in a move that threatened to chill this organizing heat wave, billionaire Joe Ricketts abruptly shut down his Gothamist and DNAinfo news networks days after workers prevailed in an NLRB election. This move is perhaps the starkest example of how our labor-relations system is broken beyond repair — and why new models of worker representation are needed.

In higher education, following a frustratingly late-in-term Obama NLRB decision to restore the right of graduate employees to organize, graduate workers have begun to do so in great numbers. Graduate employees at American University, Brandeis, the University of Chicago and beyond have joined the ranks of adjuncts and other contingent faculty who organized with a crowded and competitive field of unions who seek to represent them.

There are varying degrees of resistance. Rare is the college that doesn’t at least put up a fancy F.A.Q. that bemoans the potential “diminishment of the collegial relationship between some students and their mentors.” But some universities — led by the Ivy Leagues — are refusing to bargain with certified unions or cooperate with the NLRB at all. They’re dragging out the clock, waiting for Trump’s board to overturn Obama’s precedent and strip grads of their organizing rights all over again.

To be clear, that means that the Ivy League universities—which tout themselves as bulwarks of liberal democracy — are appealing to an increasingly authoritarian Trump administration to rule that their employees have no rights.

Finally, as a part of their “Better Deal,” Senate Democrats introduced a comprehensive reform bill to reshape the National Labor Relations Act. It would ban “right to work,” restore workers’ right to engage in solidarity activism, expand the act to cover public sector workers and “independent contractors,” streamline union certification procedures and create financial penalties to bosses who willfully break the law.

It’s exactly the bill we needed Jimmy Carter to sign into law in 1978.

I don’t mean to be churlish. These reforms would surely be helpful in restoring workers’ rights. But they also wouldn’t go far enough towards expanding the membership and political reach of unions in all states and all sectors of the economy as rapidly as we need if we’re going to stop the creeping spread of fascism.

For that, we need “all-in” systems of labor rights like just cause and sectoral labor standards. These ideas are being discussed in Washington. I’ve been in some of the conversations. Repealing Taft-Hartley, as the “Better Deal” would essentially do, is – amazingly – the centrist compromise within the Democratic establishment right now. Bigger and bolder reform ideas are possible!

There are two key dynamics at play. First, while the Republicans’ control Congress, any Democratic bill is a dead letter. This actually makes the next year an ideal time to float radical trial balloons, which, if they gain any traction could remain a part of the agenda in 2021. Second, the race for the Democratic presidential nomination is quickly shaping up into a race to the left, and most potential candidates want to make their mark on workers’ issues.

These political dynamics, plus continued on-the-ground organizing, are reasons for optimism in 2018.

How does your brain impact decision-making?

(Credit: Shutterstock/Salon)

Decisions span a vast range of complexity. There are really simple ones: Do I want an apple or a piece of cake with my lunch? Then there are much more complicated ones: Which car should I buy, or which career should I choose?

Neuroscientists like me have identified some of the individual parts of the brain that contribute to making decisions like these. Different areas process sounds, sights or pertinent prior knowledge. But understanding how these individual players work together as a team is still a challenge, not only in understanding decision-making, but for the whole field of neuroscience.

Part of the reason is that until now, neuroscience has operated in a traditional science research model: Individual labs work on their own, usually focusing on one or a few brain areas. That makes it challenging for any researcher to interpret data collected by another lab, because we all have slight differences in how we run experiments.

Neuroscientists who study decision-making set up all kinds of different games for animals to play, for example, and we collect data on what goes on in the brain when the animal makes a move. When everyone has a different experimental setup and methodology, we can’t determine whether the results from another lab are a clue about something interesting that’s actually going on in the brain or merely a byproduct of equipment differences.

The BRAIN Initiative, which the Obama administration launched in 2013, started to encourage the kind of collaboration that neuroscience needs. I just think it hasn’t gone far enough. So I co-founded a project called the International Brain Laboratory – a virtual mega-laboratory composed of many labs at different institutions – to show that the proverb “alone we go fast, together we go far” holds true for neuroscience. The first question the collaboration is tackling focuses on decision-making by the brain.

We know a lot, but not enough, about how the cogs all fit together.

Piyushgiri Revagar, CC BY-NC-ND

The brain’s decision team

Individual neuroscience labs have already uncovered a lot about how particular brain areas contribute to decision-making.

Say you’re choosing between an apple or a piece of cake to go with lunch. First, you need to know that apples and cake are the two options. That requires action from brain areas that process sensory information – your eyes see the apple’s bright red skin, while your nose takes in the sweet smell of cake.

Those sensory areas often connect to what we call association areas. Researchers have traditionally thought they play a role in putting different pieces of information together. By collating information from the eyes, the ears and so on, the association areas may give a more coherent, big-picture view of what’s happening in the world.

And why choose one action over another? That’s a question for the brain’s reward circuitry, which is critical in weighing the value of different options. You know that the cake will taste sweetly delicious now, but you might regret it when you’re heading to the gym later.

Then, there’s the frontal cortex, which is believed to play a role in controlling voluntary action. Research suggests it’s involved in committing to a particular action once enough incoming information has arrived. It’s the part of the brain that might tell you the piece of cake smells so good that it’s worth all of the calories.

Understanding how these different brain areas typically work together to make decisions could help with understanding what happens in diseased brains. Patients with disorders such as autism, schizophrenia and Parkinson’s disease often use sensory information in an unusual way, especially if it’s complex and uncertain. Research on decision-making may also inform treatment of patients with other disorders, such as substance abuse and addiction. Indeed, addiction is perhaps a prime example of how decision-making can go very wrong.

A lab collaborative spread around the world

Right now, neuroscientists are taking lots of closeup snapshots of what happens in particular areas of the brain when it makes a decision. But they aren’t coordinating with each other much, so these closeup pieces don’t fit together to give us the big picture of decision-making that we need.

That’s why a team of us joined up to form the International Brain Laboratory. With support from the International Neuroinformatics Coordinating Facility, the Wellcome Trust, and the Simons Foundation (also a funder of The Conversation US), we aim to create that big picture by designing one large-scale experiment that uses the exact same approach to study many different brain areas. Because the brain is so complex, we need the expertise of many different labs that each specialize in particular brain areas. But we need them to coordinate and use the same approach so that we can put all of their different pieces of the picture together.

We’re bringing together a team of 21 scientists who will work very closely to understand how billions of neurons work together in a single brain to make decisions. About a dozen different labs will each do part of one big experiment by measuring neuron activity in animals engaged in exactly the same game. Our team members will record activity from hundreds of neurons in each animal’s brain. We’ll collect tens of thousands of neuronal recordings that we can analyze together.

Keep it simple

In real-world decisions, you’re combining lots of different pieces of information – your sensory signals, your internal knowledge about what’s rewarding, what’s risky. But implementing that in a laboratory context is pretty hard.

We’re hoping to recreate a mouse’s natural foraging experience. In real life, there are many different paths an animal can take as it navigates the world looking for something to eat. It wants to find food, because food is rewarding. It uses incoming sensory cues, like, “Oh, I see a cricket over there!” An animal might combine that with a memory of reward, like, “I know this area has lush berry bushes, I remember that from yesterday, so I’ll go there.” Or, “I know over here there was a cat last time, so I’d better avoid that area.”

Imagining the world from a mouse’s perspective is essential for International Brain Laboratory scientists when picking a lab task that mimics a real-world decision.

Elena Nikanorovna, CC BY-ND

At first pass, the setup we’re using for the International Brain Laboratory doesn’t look very natural at all. The mouse has a little device that it uses to report decisions – it’s actually a wheel from a Lego set. For example, it might learn that when it sees an image of a vertical grating and turns the wheel until the image is centered, it gets a reward. If you think about what foraging is – exploring the environment, trying to find rewards, making use of sensory signals and prior knowledge – this simple Lego wheel activity does capture its essence.

We really had to think about the trade-off between having a behavior that was complex enough to give us insight into interesting neural computations, and one that was simple enough that it could be implemented in the same way in many different experimental laboratories. The balance we struck was a decision-making task that starts simple and becomes more and more complex as an individual animal achieves different stages of training.

Even in the simplest, very earliest stage we’re looking at, where the animals are just making voluntary movements, they’re deciding when to make a movement to harvest a reward. I’m sure we can go much further, but even if that’s as far as we get, having neural measurements from all over the brain during a simple behavior like this will be very interesting. We don’t know how it happens in the brain that you decide when to take a particular action and how to execute that action. Having neural measurements from all over the brain of what happened just before the animal spontaneously decided to go and get a reward will be a huge step forward.

Anne Churchland, Associate Professor of Neuroscience, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

6 media resolutions every family should make in 2018

(Credit: Peter Essick)

If there’s one thing nearly every parent wants to get better at, it’s staying ahead of their kids when it comes to media and technology. From crazy YouTube videos to marathon Minecraft sessions to sexy selfies, kids are constantly testing the limits (and our patience) with new stuff they want to download, watch, and play. Even as we encourage our kids to use their devices for good (homework, making things, learning stuff), we still butt heads over safety, screen time, age-appropriate content, and the importance of making eye contact instead of staring at your screen when a human being is talking to you.

Well, 2018 can be the year you do things differently. Learning to live in harmony with media and tech — in a way that works for your family — is one of the most forward-thinking actions you can take as a parent raising kids in the digital age. Who knows? One of these may be the start of a new family tradition.

Commit to learning about one media item your kid is passionate about. If your mind tends to wander when your kid explains every detail of her latest Minecraft mod, catch yourself and tune back in. Whether it’s the latest YouTuber, a new app, a game, or a dank meme, it matters in their world. It’s a good sign if they’re sharing it with you because it means that they care about what you think. If you know a little something about the stuff your kid is into, it can spark conversations, lead to new media choices, and make it easier to manage (but you don’t need to tell your kid that).

Choose one night of the week to share YouTube videos with each other. More and more, kids are getting their entertainment, news, and pop culture infusion from YouTube. And half the posts that pop in our social media feeds have videos. Take a half hour to enjoy something silly, educational, or thought-provoking that caught your attention. (See our YouTube reviews for ideas.) YouTube has tons of great clips … and tons of iffy stuff. Watching your choices nudges your kids toward the types of videos you’d rather have them watch. And watching theirs clues you into their YouTube life.

Deal with the one thing that’s most frustrating about your kid’s media/tech. What didn’t work in 2017? Do you need better rules or limits? Do you need to make a space for charging phones outside the bedroom at night? Do you need to stop watching TV before school? Do you need your kid to be better about responding to your texts? Check out the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Family Media Use Plan worksheets to identify problem areas and solve them. Make a New Year’s resolution to fix a nagging issue that’s causing friction between you and your kid.

Lead by example by putting down your phone at a certain time every evening. Make an announcement when you shut down your devices. Your kids may roll their eyes, but it sends a strong message that you can set boundaries — and stick to them.

Put a new spin on the device-free dinner. If you’re already designating a night or nights as device-free, give yourself a pat on the back. How about taking it a step further and doing something that inspires closeness and conversation with kids? Some ideas: Pick a word of the day, play “two truths and a lie,” or talk about what you’d do if you won the lottery. Leave school, work, and chores to discuss after dinner.

Start a book club (with your kids). It’s so important to keep your kids reading. Strong readers do well in all school subjects. They also learn to focus for extended periods, a necessary skill in the world of bite-sized information. And reading together gives you a chance to discuss plot, characters, and themes that can apply to all aspects of life. There’s no shortage of book recommendations. You can get into a book series, whether you have little kids, tweens, or teens. Or you can introduce your kids to the great classics of English literature. Focus on one topic — for example, “What did you like best about the book?” Then use the conversation starters from our book reviews or look for discussion guides in the back of the book or online.

To benefit baby’s brain, read the right books at the right times

(Credit: Auditory Neuroscience Lab, Northwestern University via AP)

Parents often receive books at pediatric checkups via programs like Reach Out and Read and hear from a variety of health professionals and educators that reading to their kids is critical for supporting development.

The pro-reading message is getting through to parents, who recognize that it’s an important habit. A summary report by Child Trends, for instance, suggests 55 percent of three- to five-year-old children were read to every day in 2007. According to the U.S. Department of Education, 83 percent of three- to five-year-old children were read to three or more times per week by a family member in 2012.

What this ever-present advice to read with infants doesn’t necessarily make clear, though, is that what’s on the pages may be just as important as the book-reading experience itself. Are all books created equal when it comes to early shared-book reading? Does it matter what you pick to read? And are the best books for babies different than the best books for toddlers?

In order to guide parents on how to create a high-quality book-reading experience for their infants, my psychology research lab has conducted a series of baby learning studies. One of our goals is to better understand the extent to which shared book reading is important for brain and behavioral development.

What’s on baby’s bookshelf

Researchers see clear benefits of shared book reading for child development. Shared book reading with young children is good for language and cognitive development, increasing vocabulary and pre-reading skills and honing conceptual development.

Shared book reading also likely enhances the quality of the parent-infant relationship by encouraging reciprocal interactions – the back-and-forth dance between parents and infants. Certainly not least of all, it gives infants and parents a consistent daily time to cuddle.

Recent research has found that both the quality and quantity of shared book reading in infancy predicted later childhood vocabulary, reading skills and name writing ability. In other words, the more books parents read, and the more time they’d spent reading, the greater the developmental benefits in their 4-year-old children.

This important finding is one of the first to measure the benefit of shared book reading starting early in infancy. But there’s still more to figure out about whether some books might naturally lead to higher-quality interactions and increased learning.

Babies and books in the lab

In our investigations, my colleagues and I followed infants across the second six months of life. We’ve found that when parents showed babies books with faces or objects that were individually named, they learn more, generalize what they learn to new situations and show more specialized brain responses. This is in contrast to books with no labels or books with the same generic label under each image in the book. Early learning in infancy was also associated with benefits four years later in childhood.

Our most recent addition to this series of studies was funded by the National Science Foundation and just published in the journal Child Development. Here’s what we did.

First, we brought six-month-old infants into our lab, where we could see how much attention they paid to story characters they’d never seen before. We used electroencephalography (EEG) to measure their brain responses. Infants wear a cap-like net of 128 sensors that let us record the electricity naturally emitted from the scalp as the brain works. We measured these neural responses while infants looked at and paid attention to pictures on a computer screen. These brain measurements can tell us about what infants know and whether they can tell the difference between the characters we show them.

We also tracked the infants’ gaze using eye-tracking technology to see what parts of the characters they focused on and how long they paid attention.

The data we collected at this first visit to our lab served as a baseline. We wanted to compare their initial measurements with future measurements we’d take, after we sent them home with storybooks featuring these same characters.

We divided up our volunteers into three groups. One group of parents read their infants storybooks that contained six individually named characters that they’d never seen before. Another group were given the same storybooks but instead of individually naming the characters, a generic and made-up label was used to refer to all the characters (such as “Hitchel”). Finally, we had a third comparison group of infants whose parents didn’t read them anything special for the study.

After three months passed, the families returned to our lab so we could again measure the infants’ attention to our storybook characters. It turned out that only those who received books with individually labeled characters showed enhanced attention compared to their earlier visit. And the brain activity of babies who learned individual labels also showed that they could distinguish between different individual characters. We didn’t see these effects for infants in the comparison group or for infants who received books with generic labels.

These findings suggest that very young infants are able to use labels to learn about the world around them and that shared book reading is an effective tool for supporting development in the first year of life.

Tailoring book picks for maximum effect

So what do our results from the lab mean for parents who want to maximize the benefits of storytime?

Not all books are created equal. The books that parents should read to six- and nine-month-olds will likely be different than those they read to two-year-olds, which will likely be different than those appropriate for four-year-olds who are getting ready to read on their own. In other words, to reap the benefits of shared book reading during infancy, we need to be reading our little ones the right books at the right time.

For infants, finding books that name different characters may lead to higher-quality shared book reading experiences and result in the learning and brain development benefits we find in our studies. All infants are unique, so parents should try to find books that interest their baby.

My own daughter loved the “Pat the Bunny” books, as well as stories about animals, like “Dear Zoo.” If names weren’t in the book, we simply made them up.

It’s possible that books that include named characters simply increase the amount of parent talking. We know that talking to babies is important for their development. So parents of infants: Add shared book reading to your daily routines and name the characters in the books you read. Talk to your babies early and often to guide them through their amazing new world – and let storytime help.

Lisa S. Scott, Associate Professor in Psychology, University of Florida

Danger in my belly: I know where Donald Trump’s tribal rhetoric can lead

People walk through burning refuse in Dadaab, Kenya the world's biggest refugee complex August 20, 2009 in Dadaab, Kenya (Credit: Getty/Spencer Platt)

I am black. I am a Muslim. I am a war survivor and I am a refugee turned writer from Somalia who now lives in the U.S. Like you, I am a two-legged human creature. America is not a distant hope for me or, for the refugees across the United States, but it is a warm and peaceful home. Life has taught me that it is easy to destroy a nation, but it is very hard to build it up.

Somalia, the country of my birth, is now on the list of banned countries for those wishing to enter the U.S. My own mother, who is a naturalized citizen, currently lives in Somalia. As her first son, I had seen the gory of war, the agony of refugee camps, but, thanks be to God, she and I made it to America in July 1993. We felt safe and made cold New England our new home. With the rise of President Donald Trump’s America, that sense of belonging is now dimmed.

In September 1993 I started Bedford High School, where on my first day the school hired Estee, an English as a second language teacher for me. Staffers bought a blue flag with a white star in the middle and they told me that I was a Somali-American. In a way, this restored the dimmed identity of my fractured life. The school exposed me to books: “The Old Man and the Sea” by Ernest Hemingway, “The Scarlet Letter” by Nathaniel Hawthorne, “The Autobiography of Malcolm X” as told to Alex Haley and “The Things They Carried” by Tim O’Brien.

The first word I felt in love with in the English language was “preposterous.” There was something about this word that I liked. In Somalia, a country with a single race, a single religion and single tribe but with many clans, the war between clans was beyond preposterous. I never asked God for membership in the tribe I was born into. God chose it through my father, and the fact that my siblings and I belonged to the clan of our dead father was definitely preposterous.

The hideous walk in the jungle between Kenya and Somalia was preposterous. The refugee camp was preposterous. Seeing dead people was preposterous. New England’s cold weather was preposterous; but I yearned to see the snow fall from the sky. The dream I carried to America was preposterous. Having to learn a new language and a new culture was preposterous. Working for 15 years and discovering that I was a black man in America was beyond preposterous.

Above all, President Trump’s immigration ban has been the most preposterous thing of all my life, whereby America’s 70 years’ worth of post-World War II prestige is being damaged on a global scale. But since hope was all I carried to America, I am hopeful that the voices of reasons and intellect will prevail over the demagoguery.

The fast-moving situation with regard to President Trump’s executive order temporarily banning people from seven majority-Muslim countries from entering the U.S., combined with his Twitter rhetoric, is not only creating doubt and fear in the heart of refugees, but it is also labeling Muslim Americans as terrorist sympathizers. For the first time since I walked on the clean American soil, I feel a danger in my belly. I am now afraid for all the Muslim refugees who left their countries because of war and who came to America to seek a better life. And I know a lot about the danger of labeling a group of people as a threat that needs to be contained and removed from society.

In 1990, I was 13 years old. At the time, my world was about skipping school, flirting with girls, raising pigeons and playing soccer under the magnificent Mogadishu blue sky. I knew nothing about what was simmering behind the lips of the people. My father had died a year earlier, but as part of Somali culture, my younger siblings and I belonged to our dead father’s clan. President Siad Barre had ruled Somalia for more than 20 years, and he, too, belonged to our clan.

The Somali economy was struggling and people were hurting. Jobless men often sat in groups in front of the teahouses. As they played cards, they started to blame the ruling clan for their economic ills. Politicians picked up the blame game and politicized it. It wasn’t long before the men’s tea talks over poker turned into fistfights in the markets. Frustrated men began to engage in drive-by shootings on innocent people. The murder rates went up. As people’s internal hate simmered, conflict on a larger scale erupted in the streets of Mogadishu in December 1990.

A boy, a next-door neighbor, came to my house holding an AK47. He came to kill me because I was no longer his friend. I, along with my family, was among those who were libeled as being part of the enemy clan. The threat of murder hung over my family until we made a hasty departure — to anywhere. We fled our three-bedroom villa in Mogadishu, leaving behind a little of everything: my birdhouse, the chicken coop, Bella and Bilan (our goats), a broom, a wheelbarrow, examination papers, a bulky briefcase, my red typewriter, photographs, and the wooden chair with stretched animal skin that my father used to sit on before he died.

Our precious lives were more important than worldly things. In the same year, that boy who wanted to kill me lost his own life. Our lives had been like a lick of flame from hellfire. Somalia is still burning. In the end, there were no victors but only victims.

I called my mother this morning. We talked about how unlucky we were to have experienced the war in Somalia and the possible upcoming conflict. She expressed her fear as she questioned our peaceful stay in the United States and, though I shrugged off her concerns, I fully understood her. As survivors of Somalia’s catastrophic civil war, we could see the danger that lies in the uncontrolled tongue and we have seen this before.

She told me about how for three years the rain refused to fall and that the soil in Somalia is dried. The crops, the camels, the goats, the sheep and the cows are dying in masses. A poor mother with three orphan children recently died of starvation. As she spoke of the carnage from the prolonged dry season, I thought about the impending devastation from global warming, of Somalia is also a victim.

Like many naturalized citizens, I was rescued by America from the decay of the refugee camps and exposed to literature. The danger is no longer in our bellies. It is out in the open because President Trump has made it OK to express it openly as he advocates, among other things, fear of Muslim refugees in the name of safety for the homeland. If the flame of rhetoric is not contained, I fear for my America. I owe at least to write to her about what I know.

Until Harvey Weinstein, accusations against Trump were forgotten

Donald Trump (Credit: Getty/Chung Sung-Jun)

By and large, 2017 was a year of reckoning for men who have sexually harassed and assaulted women. But 2017 was also the year evening programming on cable news forgot about the women who said President Donald Trump sexually assaulted them.

Over the past year, we’ve seen powerful men lose their jobs and reputations after women and men cameforward telling their stories of harassment and assault. One man whose reckoning has yet to come, however, is the president of the United States. By October 2016, at least 20 women had said then-candidate Trump engaged in sexual misconduct, including 12 nonconsensual physical encounters. The accusations largely came after a video clip emerged of Trump admitting to sexual assault in 2005.

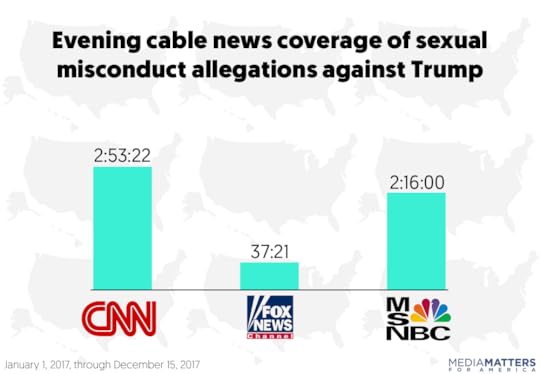

A Media Matters analysis found that the stories these women told about Trump’s alleged — and admitted — sexual misconduct were largely forgotten by evening cable news hosts and guests in 2017, especially on Fox News. Moreover, the overwhelming majority of coverage came only after The New York Times initially reported on Harvey Weinstein’s history of sexual harassment and assault, which precipitated a wave of coverage about dozens of men who now stand credibly accused of sexual misconduct.

This study found:

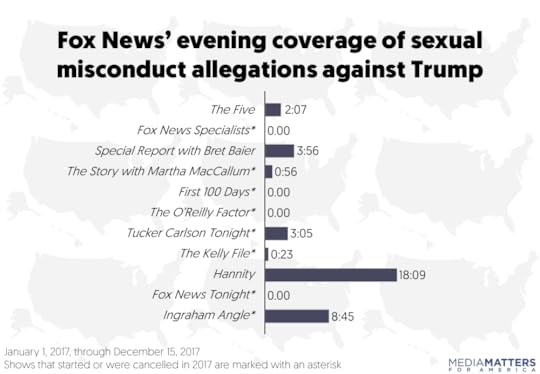

Fox News spent less than 40 minutes on Trump’s sexual misconduct in 2017

Most of the discussions of Trump’s sexual misconduct took place after reporting about Harvey Weinstein’s history of sexual harassment and assault

Fox News spent less than 40 minutes on Trump’s sexual misconduct in 2017

Between January 1 and December 15, 2017, evening Fox News programs spent a total of 37 minutes and 21 seconds on the women who said Trump assaulted or harassed them.

John Whitehouse / Media Matters

In contrast, CNN spent 2 hours, 53 minutes, and 22 seconds on the allegations, while MSNBC spent 2 hours and 16 minutes discussing them.

John Whitehouse / Media Matters

While many shows ignored and minimized the allegations against Trump, some of his most ardent defenders on Fox faced them head-on to merely dismiss them out of hand.

On the December 13 edition of Fox News’ The Ingraham Angle, host Laura Ingraham attempted to discredit the allegations against Trump, asking, “If someone accused of you something from 20 years ago and you denied it … would it be fair for people to say, God, he’s accused?”

And on the November 16 edition of Fox News’ Hannity, host Sean Hannity alleged that the women who spoke out against Trump said they were “taken out of context purposely by The New York Times.”

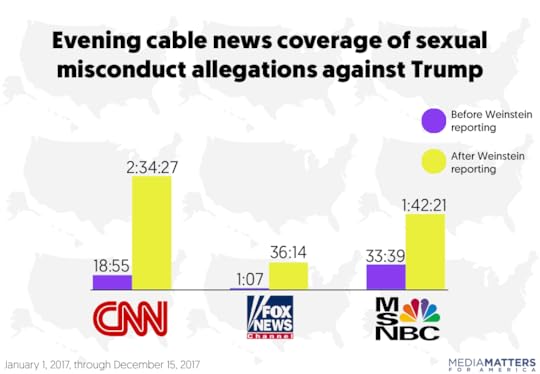

Most of the discussions of Trump’s sexual misconduct took place after reporting about Harvey Weinstein’s history of sexual harassment and assault

The vast majority of the reporting on the accusations made against Trump on evening cable news took place after The New York Times reported on October 5 about Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein’s history of sexual harassment and assault. The so-called “Harvey effect” spurred women to come forward to discuss their experiences of sexual violence. In turn, the reporting on Weinstein also appeared to create an opening for cable news to bring up the allegations made against the president. In the nine months before The New York Timesreported on Weinstein, evening cable news spent less than an hour discussing the allegations made against Trump. However, in about 2 1/2 months after the Times reported on Weinstein, evening cable news devoted nearly five hours to reporting on the accusations against Trump.

John Whitehouse / Media Matters

For many survivors across the country, it’s nearly impossible to forget that 20 women have reported sexual harassment and assault committed by our president, who has admitted to such behavior. Cable news shouldn’t forget about it, either.

Methodology

Media Matters searched Nexis for mentions of “Trump” within 50 words of all permutations of “assault,” “rape,” “harass,” “grope,” “grab,” “sexual,” or “allege” that took place on evening ( 5 p.m. to 11 p.m.) programs on CNN, MSNBC, and Fox News between January 1 and December 15, 2017. For inclusion in this study, segments had to feature a significant discussion of the allegations made against Trump.

We defined a “significant discussion” as one of the following:

a segment where the allegations against Trump were the stated topic of discussion;

a segment in which two or more speakers discussed the allegations; or

a host monologue during which the allegations were the stated topic of discussion.

Qualifying segments were then timed using iQ media. Repeated segments were not counted. Teasers for upcoming segments were also not counted.

* Due to substantial reorganization of Fox News’ programming during the study period, programs that were either added or removed from the network during the study period are marked with an asterisk.