Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 196

December 28, 2017

“Dr. Phil” show accused of supplying substance-addicted guest with vodka, Xanax

Phil McGraw (Credit: Getty/Ethan Miller)

According to a detailed report published on STAT Thursday, members of the production staff of the “Dr. Phil” program may have supplied alcohol and off-prescription pharmaceutical drugs to guests who appeared on the tough-love, personal-advice series to discuss their substance abuse.

Specifically and notably, guest Todd Herzog alleges that when he arrived to discuss his substance dependency with the show’s host, Phillip “Dr. Phil” McGraw, he found a bottle of vodka in his dressing room. Having drunk that, he says someone backstage gave him a Xanax. (The combination of benzodiazepines like Xanax and alcohol can be highly intoxicating and potentially lethal.)

When he appeared on camera for the taping of the episode, Herzog was inebriated to the point of incapacitation (“he had to be carried onto the set and lifted into a chair,” the report says). McGraw noted to the camera during the taping, “I’ve never talked to a guest who was closer to death.”

Other former guests visiting the show to discuss their issues with substance abuse spoke to STAT about their treatment by show staffers, which included forced 48-hour detoxes at hotel rooms apparently done without proper and certified medical supervision. One guest described buying heroin with the crew’s knowledge, being told where to score it on the street and then being followed by a crew taping the hunt for the deadly drug without intervening.

Throughout the report, representatives for McGraw — who has a PhD in clinical psychology but is not a medical doctor or educated in substance-abuse treatment — and staff members deny that guests were given access to drugs, suggest that the show provided them with adequate care, claim that various medical institutions provided them with oversight and, ultimately, shirk any responsibility of culpability for their guests’ actions either on or off set. STAT, through research, found these claims less than compelling.

When pressed, representatives for McGraw and the show changed their stories and claims throughout the report.

Interestingly, writers David Armstrong and Evan Allen say that some employees of “Dr. Phil” “raised alarms about the treatment of guests.” They continue, “In one lawsuit filed last year against McGraw and his production company in Los Angeles Superior Court, a former segment director, Leah Rothman, accused McGraw of false imprisonment for trapping employees in a room to threaten them over leaks to the media.”

The writers add that Rothman “also alleged that guests complained that their lives were ‘ruined.’ One guest attempted suicide after the show, according to a deposition with another staff member.” Indeed, while one of the guests Armstrong and Allen spoke with credited McGraw for saving her life, Herzog called his appearance “a complete bust.” He added that his experience with the show “didn’t help at all. Just ratings for him. People are going to him, like us, with serious, life-threatening problems looking for help. It just doesn’t happen.”

Dr. Jeff Sugar, an assistant professor of clinical psychiatry at the University of Southern California, called the show’s treatment of substance-addicted guest “a callous and inexcusable exploitation.” He added, “These people are barely hanging on. It’s like if one of them was drowning and approaching a lifeboat, and instead of throwing them an inflatable doughnut, you throw them an anchor.”

Again, anyone from the show speaking on the record to STAT denied all the allegations above, as did McGraw’s representatives.

McGraw has hosted the “Dr. Phil” show, in which he attempts to solve guests’ personal issues through his personal brand of uncompromising self examination and confrontational dialogue, since 2002. Before that, he was a frequent guest on Oprah Winfrey’s talk show.

While his approach has made his show wildly popular (and lucrative) and many guests and fans claim he has had a measurable positive impact on their lives, he has become a controversial figure to many. His methods and approach to psychological care have been called “unethical” and “incredibly irresponsible” by the National Alliance on Mental Illness. Others have offered less kind words.

Over the years a number of questionable actions have been taken by either McGraw or the staff of his show. For instance, in 2008, “Dr. Phil” supplied bail for six girls who had been arrested in connection with charges including kidnapping and assault, crimes that the girls themselves had documented on video. Apparently, a production member bailed them out in order to book them as guests.

In that same year, McGraw visited the hotel room of singer Britney Spears, then on a psychological hold after a breakdown, to discuss her mental state. “Rather than helping the family’s situation, the celebrity psychologist caused additional damage,” said a spokesperson for the Spears family at the time.

In 2016, McGraw attracted broad criticism for an episode featuring a visibly distressed and disoriented Shelly Duvall. Throughout the show, McGraw attempted — with much guilting — to enroll the actress for medical treatment at a clinic. At the end of the episode, it was revealed that the clinic had paid the “Dr. Phil” show a promotional fee for its inclusion in the broadcast. Claims of exploitation dogged McGraw soon after.

Law banning Mexican studies in Arizona public schools ruled unconstitutional

(Credit: Getty Images)

A federal judge formally, and permanently, issued a block on an Arizona law which banned ethnic studies from being taught across the state, after conservative lawmakers and educators went after a Mexican-American studies class being taught in Tucson public schools.

On Wednesday, December 27, Judge Wallace Tashima ruled that the 2010 law was unconstitutional and “not for a legitimate educational purpose, but for an invidious discriminatory racial purpose and a politically partisan purpose,” according to the Los Angeles Times. In a prior ruling from August, Tashima said that the law violated students’ First Amendment “right to receive information and ideas.”

The ruling follows a seven-year court battle between Tucson students and the state of Arizona. The Tucson Unified School District began teaching a curriculum on Mexican-American history, literature and art in 1998, according to the New York Times. However, state education chief Tom Horne was among one of many officials who felt that the Mexican-American program was “hateful” and akin to “the old South.” Horne was spurred to action by “Occupied America: A History of Chicanos,” a specific book in the curriculum which he took offense to because, as he felt, it implied that America was occupying Mexican land in an inherently racist move.

After the ban was passed, the school district was forced to drop the curriculum in 2012 in fear that Arizona officials would withhold 10 percent of funding from the district should they not comply with the law. In response, Tucson students brought about a lawsuit against the state’s board of education, explaining that the law “was racist and targeted Mexican Americans,” according to the LA Times.

While Tashima previously ruled that the ban was “motivated by racial animus,” state officials maintained that the law was intended to halt courses which “promote resentment toward a race or class of people or advocate ethnic solidarity instead of treating people as individuals,” according to the New York Times. Furthermore, advocates of the law felt ethnic studies racialize the classroom and the students.

“To teach kids that they’re victims and they can’t get ahead in life because somebody’s holding them down, I think it’s a mistake,” said John Huppenthal, a republican politician and former state senator who co-wrote the bill with Horne.

The Arizona Attorney General’s Office is unsure of its next move, though appealing the ruling is not entirely off the table.

“We will consult with the superintendent and see how she would like to proceed,” spokesman Ryan Anderson told the New York Times. “Additionally, we have an obligation to evaluate the likelihood of success on appeal for the individual findings.”

The issuance of the ban came the same year another Arizona state law ignited similar conversations on race and discrimination come into public consciousness. In 2010, legislators in that state signed SB 1070 into law, requiring police officers to “determine the immigration status of a person ‘where reasonable suspicion exists’ that the person is in the country illegally.” The law raised questions about how the United States defines undocumented immigrants and what it means to be and look “illegal.” That law is still in the process of being challenged.

It is not clear at this time if the Tucson school district will bring back the Mexican-American curriculum in the wake of the judge’s ruling.

Judge grants Rick Gates, indicted in Mueller probe, freedom to party on New Year’s Eve

Rick Gates (Credit: AP/Andrew Harnik)

Rick Gates, the former business associate of President Donald Trump’s campaign chair Paul Manafort, will be allowed to temporarily modify the terms of his house arrest in order to attend “events for the New Year’s holiday.”

Judge Amy Berman Jackson granted a motion filed by Gates’ defense in U.S. District Court, in Washington D.C., on Thursday afternoon. Gates, Trump’s former deputy campaign manager, requested that the terms of his house arrest be modified “for limited purposes so that he may accompany his family to events for the New Year’s holiday from Sunday, December 31, 2017 through Monday January 1, 2018,” documents showed.

JUST IN: Rick Gates wants to be able to leave his house … and go to a New Year's Eve party?

https://t.co/OSLXnmHyg3 pic.twitter.com/GHORKYOF7A

— Chris Geidner (@chrisgeidner) December 28, 2017

Gates, however, will not be drifting too far from his home.

“The events are within the jurisdiction of the Eastern District of Virginia, less than 60 miles from Mr. Gates’s residence,” the documents read. “Mr. Gates requests a limited release to attend these events with his family before school resumes.”

Both Gates and Manafort were indicted by special counsel Robert Mueller in connection to the ongoing probe into the Trump campaign’s alleged ties with the Russian government. They have since been under house arrest and are facing with 12 counts, including conspiracy against the United States and money laundering.

It’s certainly not the first time Gates has sought to bend the rules of his house arrest, as he was able to leave home for a weekend in early December “to attend events for his children,” after helping secure his $5 million bail conditions, Politico reported. Judge Berman Jackson granted his motion then despite opposition from Mueller’s investigative team.

Manafort was also recently granted permission to spend his Christmas holiday in the Hamptons for five days. He was spotted in Washington, D.C. upon his return.

Trump attacks Anna Wintour, possibly confusing Vanity Fair with Vogue

Donald Trump, Anna Wintour (Credit: AP/Jeff Zelevansky)

Directly in-between tweeting about MS-13 and retail sales figures, Donald Trump used exactly 280 characters at exactly 10:24 AM EST Thursday to address the fallout from an ill-handled Vanity Fair video post in which writer Maya Kosoff suggested that former presidential candidate Hillary Clinton leave politics and resolve to take up knitting in the new year.

While many, including Salon, criticized both Kosoff and the Condé Nast publication that employs her for the off-tone, unfortunately-gendered attempt at breezy humor, Trump did not join that chorus of feminist critics. Instead, he focused on the current state he imagined the magazine’s management to be in following a statement the publication released Wednesday evening that said the video “was an attempt at humor and we regret that it missed the mark.”

On Thursday morning, the president wrote that “Vanity Fair, which looks like it is on its last legs, is bending over backwards in apologizing for the minor hit they took at Crooked H.” In this statement, “Crooked H,” would be winner of the popular vote in the 2016 presidential campaign, Hillary Clinton.

The commander in chief continued, “Anna Wintour, who was all set to be Amb to Court of St James’s & a big fundraiser for CH, is beside herself in grief & begging for forgiveness!”

Vanity Fair, which looks like it is on its last legs, is bending over backwards in apologizing for the minor hit they took at Crooked H. Anna Wintour, who was all set to be Amb to Court of St James’s & a big fundraiser for CH, is beside herself in grief & begging for forgiveness!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) December 28, 2017

While Anna Wintour is indeed the editorial director of all Condé Nast titles, she is less involved in the day-to-day operation of Vanity Fair and more involved with the magazine for which she is famously the editor-in-chief, Vogue. She may have had some hand in the statement in response to the public perception of the video, but it’s unlikely she even knew of that video’s creation until it had become an issue in the media. Hence, it’s hard to lay any of this at her feet.

It is true, as the president says, that many believed Wintour would have become the American ambassador to the UK (aka, the ambassador to the Court of St. James) either under Obama or Clinton, based in part on her fundraising efforts for the Democratic party. Under any presidential administration, ambassadorships to friendly nations are frequently sinecures awarded to loyal party donors.

There has been no evidence, however, that Wintour was in a deep state of emotional distress over response to the Vanity Fair video and perhaps lying in tears on her bathroom floor, eating Entenmann’s chocolate cake out of the box. The statement issued by Condé Nast is, at best, a non-apology and nowhere close to “begging for forgiveness.”

It is, as well, difficult to argue that Vanity Fair is “on its last legs.” While the full financials for all Condé Nast titles are kept private to the company, reports suggest that the glossy periodical enjoyed a circulation spike during the 2016 presidential campaign. Indeed, following one of Trump’s various negative tweets about the title, subscriptions reportedly surged.

As well, the magazine is now under a new editor-in-chief, Radhika Jones, who has taken over for the retired Graydon Carter. Experts on the industry expect good things from her.

Carter famously helped create the beloved Trump appellation “short-fingered vulgarian” when he was the editor of Spy in 1988. Carter claimed that Trump still sent him occasional letters containing photos of the future president’s hands in order to disprove the critique until as recently as 2015.

Finally, it’s confusing as to why Trump would attack Vanity Fair at all given that its writer was suggesting his primary bête noire, Clinton, should retire from politics. Perhaps it is less what the magazine said than the fact that it apologized for it that interests the president. Apologizing and admitting wrong, in the Trumpian mindset, are the worst sins of all.

While Trump’s battles with Vanity Fair have been many over the years, his conflict with Wintour is somewhat of a new thing, as Business Insider’s Brett LoGiurato helped point out with this tweet:

Of course these exist pic.twitter.com/4Mpwcyk8ks

— Brett LoGiurato (@BrettLoGiurato) December 28, 2017

Yes. Yes, of course they do.

New medical advances mark the end of a “diet wizard” reign

This Oct. 16, 2016, photo shows Nabisco’s booth at an annual dietitians' conference, where company representatives explained the health benefits of their products. The presence of major food companies underscored the conflict-of-interest issues in the nutrition field. (AP Photo/Candice Choi) (Credit: AP)

For many years, the long-term success rates for those who attempt to lose excess body weight have hovered around 5-10 percent.

In what other disease condition would we accept these numbers and continue on with the same approach? How does this situation sustain itself?

It goes on because the diet industry has generated marketing fodder that obscures scientific evidence, much as the Wizard of Oz hid the truth from Dorothy and her pals. There is a gap between what is true and what sells (remember the chocolate diet?). And, what sells more often dominates the message for consumers, much as the wizard’s sound and light production succeeded in misleading the truth-seekers in the Emerald City.

As a result, the public is often directed to attractive, short-cut weight loss options created for the purposes of making money, while scientists and doctors document facts that are steamrolled into the shadows.

We are living in a special time, though – the era of metabolic surgeries and bariatric procedures. As a result of these weight loss procedures, doctors have a much better understanding of the biological underpinnings responsible for the failure to lose weight. These discoveries will upend the current paradigms around weight loss, as soon as we figure out how to pull back the curtain.

As a dual board-certified, interventional obesity medicine specialist, I have witnessed the experience of successful weight loss over and over again – clinically, as part of interventional trials and in my personal life. The road to sustained transformation is not the same in 2018 as it was in 2008, 1998 or 1970. The medical community has identified the barriers to successful weight loss, and we can now address them.

The body fights back

For many years, the diet and fitness industry has supplied folks with an unlimited number of different weight loss programs – seemingly a new solution every month. Most of these programs, on paper, should indeed lead to weight loss. At the same time, the incidence of obesity continues to rise at alarming rates. Why? Because people cannot do the programs.

First, overweight and obese patients do not have the calorie-burning capacity to exercise their way to sustainable weight loss. What’s more, the same amount of exercise for an overweight patient is much harder than for those who do not have excess body weight. An obese patient simply cannot exercise enough to lose weight by burning calories.

Second, the body will not let us restrict calories to such a degree that long-term weight loss is realized. The body fights back with survival-based biological responses. When a person limits calories, the body slows baseline metabolism to offset the calorie restriction, because it interprets this situation as a threat to survival. If there is less to eat, we’d better conserve our fat and energy stores so we don’t die. At the same time, also in the name of survival, the body sends out surges of hunger hormones that induce food-seeking behavior – creating a real, measurable resistance to this perceived threat of starvation.

Third, the microbiota in our guts are different, such that “a calorie is a calorie” no longer holds true. Different gut microbiota pull different amounts of calories from the same food in different people. So, when our overweight or obese colleague claims that she is sure she could eat the same amount of food as her lean counterpart, and still gain weight – we should believe her.

Lots of shame, little understanding

Importantly, the lean population does not feel the same overwhelming urge to eat and quit exercising as obese patients do when exposed to the same weight loss programs, because they start at a different point.

Over time, this situation has led to stigmatizing and prejudicial fat-shaming, based on lack of knowledge. Those who fat-shame most often have never felt the biological backlash present in overweight and obese folks, and so conclude that those who are unable to follow their programs fail because of some inherent weakness or difference, a classic setup for discrimination.

The truth is, the people failing these weight loss attempts fail because they face a formidable entry barrier related to their disadvantaged starting point. The only way an overweight or obese person can be successful with regard to sustainable weight loss, is to directly address the biological entry barrier which has turned so many back.

Removing the barrier

There are three ways to minimize the barrier. The objective is to attenuate the body’s response to new calorie restriction and/or exercise, and thereby even up the starting points.

First, surgeries and interventional procedures work for many obese patients. They help by minimizing the biological barrier that would otherwise obstruct patients who try to lose weight. These procedures alter the hormone levels and metabolism changes that make up the entry barrier. They lead to weight loss by directly addressing and changing the biological response responsible for historical failures. This is critical because it allows us to dispense with the antiquated “mind over matter” approach. These are not “willpower implantation” surgeries, they are metabolic surgeries.

Second, medications play a role. The FDA has approved five new drugs that target the body’s hormonal resistance. These medications work by directly attenuating the body’s survival response. Also, stopping medications often works to minimize the weight loss barrier. Common medications like antihistamines and antidepressants are often significant contributors to weight gain. Obesity medicine physicians can best advise you on which medications or combinations are contributing to weight gain, or inability to lose weight.

Third, increasing exercise capacity, or the maximum amount of exercise a person can sustain, works. Specifically, it changes the body so that the survival response is lessened. A person can increase capacity by attending to recovery, the time in between exercise bouts. Recovery interventions, such as food supplements and sleep, lead to increasing capacity and decreasing resistance from the body by reorganizing the biological signaling mechanisms – a process known as retrograde neuroplasticity.

Lee Kaplan, director of the Harvard Medical School’s Massachusetts Weight Center, captured this last point during a recent lecture by saying, “We need to stop thinking about the Twinkie diet and start thinking about physiology. Exercise alters food preferences toward healthy foods … and healthy muscle trains the fat to burn more calories.”

The bottom line is, obese and overweight patients are exceedingly unlikely to be successful with weight loss attempts that utilize mainstream diet and exercise products. These products are generated with the intent to sell, and the marketing efforts behind them are comparable to the well-known distractions generated by the Wizard of Oz. The reality is, the body fights against calorie restriction and new exercise. This resistance from the body can be lessened using medical procedures, by new medications or by increasing one’s exercise capacity to a critical point.

[image error]Remember, do not start or stop medications on your own. Consult with your doctor first.

David Prologo, Assistant Professor, Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences, Emory University

Trump vows to kill 50 years of federal protections

(Credit: Getty/Mandel Ngan)

President Trump wants to set the regulatory clock back to 1960, and last week he acted it out for the cameras.

Wielding a pair of golden scissors at a White House photo op, he cut red tape strung around two stacks of paper. One was a small pile of some 20,000 pages representing the amount of regulations in 1960; the other a mound of more than 185,000 pages representing those of today.

“We’re getting back below the 1960 level,” Trump declared, “and we’ll be there fairly quickly.”

#trump photo op. for repealing regulations-comparing 1960's to present. More regs needed as more people, climate change, internet, equal rights, mining, green policies, cell phones. Simple-minded approach to complex ever changing world. Remember, the dinosaurs could not adapt. pic.twitter.com/6PgpEIv4Ii

— Across the Wall (@theviewblog) December 17, 2017

There’s only one problem. That mountain of paper Trump used as a prop symbolizes hard-won measures that protect us.

To refresh the president’s memory, back in the 1960s, smog in major U.S. cities was so thick it blocked the sun. Rivers ran brown with raw sewage and toxic chemicals. Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River and at least two other urban waterways were so polluted they caught on fire. Lead-laced paint and gasoline poisoned children, damaging their brains and nervous systems. Cars without seatbelts, airbags or safety glass were unsafe at any speed. And hazardous working conditions killed an average of 14,000 workers annually, nearly three times the number today.

In response, Congress enacted the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, Safe Drinking Water Act and other landmark pieces of legislation to protect public health and safety. Some of those laws also created the Consumer Product Safety Commission, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), National Highway Traffic Safety Commission, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, and other federal agencies to write and enforce safeguards.

None of those laws, or the regulations they spawned, existed in 1960.

Trump Grew Up on Dirty Air

Trump should remember quite well what it was like in the 1960s. After all, he lived in New York, at the time one of the dirtiest cities in the country. Garbage incinerators routinely rained ash on city streets, while coal- and oil-fired power plants spewed a noxious mix of sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxide and toxic metals. John V. Lindsay, the city’s mayor from 1966 to 1973, famously quipped, “I never trust air I can’t see,” but it was no laughing matter. On Thanksgiving weekend the year Lindsay took office, the smog was so bad it killed some 200 people.

The waterways coursing around the city’s boroughs, especially the Hudson River, were just as filthy. In 1965, then-New York Gov. Nelson Rockefeller accurately called the Hudson “one great septic tank.” Indeed, 170 million gallons of raw sewage fouled the river daily while factories along its banks treated it as a waste pit. A General Motors plant in Sleepy Hollow, 27 miles north of New York City, poured its paint sludge directly into the river. Even worse, General Electric manufacturing plants in Fort Edwards and Hudson Falls dumped about 1.3 million pounds of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), a probable human carcinogen, into the river over a 30-year period ending in 1977. Since 1984, a 200-mile stretch of the river from Hudson Falls to Manhattan’s southern tip has been on the EPA’s Superfund program list of the country’s most hazardous waste sites.

Protections Prevent Disease and Save Lives

Fast forward to today. By and large, the environmental laws Congress began passing in the 1970s have been remarkably successful.

Thanks to the Clean Water Act, for example, tens of billions of pounds of sewage, chemicals and trash have been kept out of U.S. waterways since it was enacted 45 years ago. In New York City, harbor water quality has improved so much that humpback whales have returned for the first time in a century.

Thanks to the Clean Air Act, nationwide emissions of six common pollutants — carbon monoxide, lead, nitrogen dioxide, ozone, particulate matter (soot) and sulfur dioxide — plunged 70 percent on average between 1970 and 2015.

New Yorkers are breathing easier, too. On Earth Day last April, the city’s health department released a report announcing that air pollution in the Big Apple is at the lowest level ever recorded. Between 2008 and 2015, nitrogen dioxide and particulate matter declined 23 percent and 18 percent, respectively, while sulfur dioxide levels plummeted 84 percent after the city and state tightened heating oil rules.

That’s all good news for public health. In 2010 alone, according to an EPA study, Clean Air Act programs that reduced levels of fine particulate matter and ground-level ozone prevented an estimated 160,000 premature deaths, 130,000 heart attacks, and 1.7 million asthma attacks across the country.

These accomplishments, however, do not mean it’s time to eliminate or weaken environmental safeguards. There is still much left to do. Consider that in just one year — 2015 — polluters dumped more than 190 million tons of toxic chemicals into waterways nationwide; at least 5,000 community drinking water systems violated federal lead regulations; and some 116 million Americans lived in counties with harmful levels of ozone or particulate matter pollution, which have been linked to lung cancer, asthma, cardiovascular damage, reproductive problems and premature death.

If You Can’t Kill ’Em, Just Don’t Enforce ’Em

Fortunately, it will be very difficult for the Trump administration to roll back 50 years’ worth of congressionally mandated rules protecting the public from industrial poisons, harmful drugs, adulterated food and defective products. Trump’s regulation czar conceded the point immediately after the December 14 White House photo op.

“I think returning to 1960s levels would likely require legislation. It’s hard for me to know what that looks like,” said Neomi Rao, director of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs at the Office of Management and Budget. “Deregulation also takes time. If we’re doing something consistent with the law, it takes time to reduce rules.”

In the meantime, the Trump administration is resorting to the next best—or worst—thing, depending on your perspective: It has cut back dramatically on enforcing environmental laws.

A recent New York Times investigative report compared the number of enforcement actions filed in the first nine months of the Trump EPA with what the two previous administrations did over the same time period. Under Scott Pruitt, the EPA initiated about 1,900 cases, about a third fewer than under Lisa Jackson, President Obama’s first EPA administrator, and about a quarter fewer than under Christine Todd Whitman, who directed the agency under President George W. Bush and was not known for aggressive enforcement.

The Times also found that the Trump EPA is reluctant to seek civil penalties. In its first nine months, the agency tagged polluters for about $50.4 million for violations. Adjusted for inflation, that amounts to roughly 70 percent of what the Bush EPA levied and only about 39 percent of what the Obama EPA sought over the same time frame.

To make matters worse, Pruitt is threatening to cut off funding for the Justice Department’s Environment and Natural Resources Division, which files lawsuits on behalf of the EPA’s Superfund program to force polluters to cover the cost of cleaning up contaminated sites. In recent years, the EPA has reimbursed the division more than $20 million annually.

In an apparent attempt to blunt criticism, Trump acknowledged at last week’s photo op that purging a half century of protections could have an adverse impact, and he assured Americans that he would not let that happen.

“We know that some of the rules contained in these pages have been beneficial to our nation, and we’re going to keep them,” he said. “We want to protect our workers, our safety, our health, and we want to protect our water, we want to protect our air, and our country’s natural beauty.”

Somehow, I’m not convinced. Given the president’s penchant for lying, his administration’s abysmal track record, and now his avowed intention to kill nearly 90 percent of federal regulations, the smoke Trump is blowing is as thick as 1960s New York smog.

Elliott Negin is a senior writer at the Union of Concerned Scientists. His articles have appeared in the Atlantic Monthly, Columbia Journalism Review, The Hill and many other publications.

December 27, 2017

Why aren’t Hollywood films more diverse?

(Credit: AP Photo/Reed Saxon, File)

In 2014, a hacker group leaked confidential information from Sony Pictures Entertainment, including a controversial email written by an unnamed producer.

In the email, which went viral, the producer questioned the decision to cast Denzel Washington as the lead in “The Equalizer”:

“I believe that the international motion-picture audience is racist – in general, pictures with an African-American lead don’t play well overseas… But Sony sometimes seems to disregard that a picture must work well internationally to both maximize returns and reduce risk, especially pictures with decent-size budgets.”

Many actors, activists and newspapers have raised concerns related to diversity in Hollywood films. Several organizations, including blackfilm.com and the Geena Davis Institute, now actively monitor and promote diversity in media.

But was the Sony producer onto something in raising concerns about the biases of moviegoers abroad? Is it possible that the lack of nonwhite and female lead characters in Hollywood films is driven, in part, by economic concerns from movie studios? Our analysis of more than 800 films sampled between 2005 and 2012 suggests the answer is “yes.”

Who’s in the movies

Research suggests that films suffer from demographic disparities.

In one study, researchers at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism analyzed the demographic characteristics of over 11,000 speaking characters in hundreds of films and television series released in 2014. Approximately 75 percent of all actors involved were white. Meanwhile, 12 percent were black, 6 percent Asian, 5 percent Hispanic/Latino and 3 percent were identified as Middle Eastern or “other.”

We looked at the top-grossing films each year from 2005 to 2012, using information from Box Office Mojo, IMDB, The New York Times movie reviews and Rotten Tomatoes. Our data include the 150 top films each year that were distributed domestically and abroad, excluding G-rated and animated films.

Just 28 percent of movies in our sample had a female first lead character. Only 19 percent had a nonwhite first lead character.

These figures are in stark contrast to the demographics of the U.S. population. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, approximately 51 percent of the U.S. is female and 35 percent is nonwhite or Hispanic.

Consumer tastes

Recently, film studios have faced more intense competition from independent filmmakers, increased globalization and streaming video sources. In this environment, film studios may be inclined to supply movies with characteristics that appeal to more consumers and increase profits.

Since international box office revenue is now more than twice as large as domestic revenue, the economic incentive for studios to cater to the preferences of international audiences is larger than ever. The top five international box office markets are China, Japan, the U.K., France and India.

Does consumer discrimination in these markets explain the underrepresentation of female and nonwhite actors in Hollywood films?

We analyzed the potential gender and racial biases from the consumer side through their influence on box office revenue, both domestically and internationally. We looked at the relationship between cast demographics and theater audiences, controlling for other factors that may affect a movie’s success, such as production budgets, release timing, genre, critic ratings and star power.

There’s significant evidence that a film cast’s racial diversity negatively affects international box office performance. By our estimates, a 10 percentage point increase in racial cast diversity leads to 17 percent less international revenue, even after controlling for key film characteristics. This effect disappears in the domestic market.

Similarly, adding just one nonwhite lead actor led to a 40 percent decrease in international revenue.

However, we did not find any link between gender diversity and movie revenue. Productions with a female lead character fared as well economically outside the U.S. as those with a male lead.

International audiences

The results provide convincing evidence that studio executives have legitimate concerns about the relationship between diversity and revenue.

The negative effects of nonwhite characters on profits could explain the racial disparity observed in Hollywood films. In that case, it could be argued that consumer prejudice leads to roles that favor white actors more, because the increased revenue is attractive to studio executives.

Most movies make a lot more foreign revenue than domestic revenue, but movies with diverse casts can struggle abroad, even if they are incredibly successful domestically. For example, 2012’s “Think Like a Man” made US$91.5 million in the domestic market but just $4.5 million in the international market. “The Help,” a 2011 Academy Award-winning period drama, made $169.7 million in the domestic market compared to $46.9 million in the international market.

This doesn’t mean that preferences of studio executives are not at all responsible for the demographic disparity, but it does suggest that market forces are at least partly responsible.

Consumer tastes are a likely factor driving studios’ preference of nonwhite underrepresentation in movies. The revenue implications of international audience preferences are simply too large for studios to ignore.

Consumer tastes are a likely factor driving studios’ preference of nonwhite underrepresentation in movies. The revenue implications of international audience preferences are simply too large for studios to ignore.

Roberto Pedace, Professor of Economics, Scripps College

Is Bitcoin enabling right-wing extremists?

(Credit: Julia Tsokur via Shutterstock)

Political movements typically rely on public and private donations, but a new report in the Washington Post suggests that Bitcoin — the hot cryptocurrency so much in the news lately — is enabling right-wing and alt-right extremist groups.

According to the report, the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) is tracking an estimated 200 Bitcoin wallets owned by right-wing extremists. Researchers in the report say they’ve specifically seen an increase in people on the far right moving their assets into the digital currency, and using it “for ordinary business purposes.”

“Bitcoin is allowing people in the movement to go beyond cash in an envelope or a check,” Heidi Beirich, head of the Intelligence Project at the SPLC, told the Post. “It’s really a godsend to them.”

According to SPLC research, 14.88 bitcoins were paid to Andrew Anglin, editor of the Daily Stormer, a notorious neo-Nazi online publication. The transaction was made on Aug. 20, according to the report, when Anglin was “scrambling” to recover from his publication having been evicted from multiple web-hosting services. The number 14.88 is an apparent reference to a Nazi slogan that is 14 words long and also to the use of 88 as a code for “Heil Hitler.” (H is the eighth letter of the alphabet.) That amount of bitcoins was reportedly worth around $60,000 at the time. The payment was made by an anonymous source, according to cybersecurity researcher John Bambenek, who tracks Bitcoin transactions.

Anglin, in a phone interview, confirmed to the Post that he uses Bitcoin almost exclusively. “Bitcoin has helped out a lot,” he said.

“The alt-right likes Bitcoin the same way criminals and people on the dark Web like Bitcoin,” Bambenek told the Post. “It’s a great way to move around assets, especially when you’re under the threat of investigation.

Bambenek has created a Twitter bot called the Neonazi BTC Tracker, which automatically tweets every transaction made to or from 13 accounts he believes are affiliated with “known extremists and their websites.”

It’s worth mentioning, as Bambenek pointed out, that Bitcoin’s history is deeply rooted in criminal activity and the Dark Web. On the now-shuttered online black market known as the Silk Road, users conducted all transactions with bitcoins. Before it became a modern-day lottery ticket and an investment fund commodity, Bitcoin was a medium for illegal or dubious transactions.

Bitcoin’s DNA makeup seems to draw a certain crowd. As the Washington Post explained, an anonymous computer programmer calling himself Satoshi Nakamoto created the cryptocurrency in 2009. Unlike traditional currencies, Bitcoin is an intangible currency backed by no government and no bank. It relies on mathematical calculations derived from countless computers around the world and is nearly impossible to monitor or regulate.

While Bitcoin is often associated with the Silicon Valley crowd and tech world, it’s unclear whether the currency will follow suit in the movement to ban extremist groups from digital platforms. In August, the internet domain registrar GoDaddy kicked the Daily Stormer off its system, saying that the publication incited “violence against people.” WordPress, a widely used content management system for websites, removed the alt-right group Vanguard America after the Charlottesville rally last summer. But Bitcoin is not a company, and it’s not clear that banning individuals from using the currency is even possible. Responsibility for such a decision would presumably lie with the Bitcoin exchanges, which have their own issues to confront.

Best essays of 2017: The mothering class

(Credit: Getty/IP Galanternik D.U.)

The house was a green ranch, in a neighborhood of wealth that strives to appear modest. It was unlike the Section 8 apartment complex I grew up in, where new trucks had bumper stickers that said, My Kid Beat Up Your Honor Student. But on the scale of expansive houses I would come to learn as a babysitter, the home was average. The boy answered the front door and said his name. He could have said, Charlie, except it was less childlike, a name between Charlie and Henry. He was barefoot and there was white between his toes. I noted that the previous babysitter had not been diligent with sunscreen.

My dad’s in the back, he said.

The fireflies, which I called lightning bugs, were the only awe I felt that summer in Ohio. No sunshine opened through the clouds, which would give beauty to the heat. I’d lived like this all summer long. I’d lived like this for 19 years.

I had interviewed with the family over the phone at the start of the summer and spoke only to the father. He asked the usual questions and I gave sufficient answers. I had been a babysitter many times.

The boy led me down the hall, passed the front room, with its polished maple floors and empty interior, except for a few boxes. He led me past a kitchen, a clean, unnoteworthy kitchen, to the back of the house, a second living room, with gray carpet, an oversized chair, an overstuffed sofa and a television above the mantel.

His dad was not in the second living room but in a different room, and he came out through a hallway and apologized for not answering the door.

He had dark curly hair. He was as short as my ex, with a paunch, too, as my ex had.

I’ll be back at 5. He reads these books. You can go outside.

He kissed his son on the forehead, who said bye, who was casual about being left alone with a stranger. Not desperate.

The front door clicked shut.

Would you like to see my trucks?

Sure, I said.

He may have said instead, Want to play soccer?

Sure, I would have said.

We went outside, kicked a ball, walked in the grass, looked at mushrooms sprouting between the driveway and the curb.

* * *

I had gotten a call that May from my father. He said he was taking a vacation. An unplanned vacation. He was a man that did not travel unless he had to.

Where are you? I asked.

Oh, somewhere. Memphis!

On the phone his voice was light. His voice was so light it could float away.

I don’t have a phone number now! I’ll call you again soon! Love you!

I heard the clink of my father hanging up the pay phone.

* * *

When the father returned, the boy and I were in the backyard. I noted that the father drove a grey Saab from the ’90s, the kind that resembled a brain with an exaggerated frontal lobe. My ex had this car, too, with red velvet seats that stunk. He bought it because it had style, despite the poor reviews, which I read aloud to him from a consumer reporting guide. The car was always broken — an oil leak, a slipping transmission — and it was one of many things he desired not because they were sturdy but because they were beautiful. An aesthete, I’d say now. Considering my interest in him, I was an aesthete, too.

* * *

A week before I began babysitting the boy, I packed my suitcase, four boxes of books and my toothbrush when a letter arrived for my live-in boyfriend from Vanna White, courtesy of Newark, New Jersey, and I knew this letter was from an ex-girlfriend, who was not-Vanna White, whose name was a day of the week. Inside the envelope, I imagined, were blurry naked pictures of her. I did not open it.

The advice to leave him came from my mother, who called 10 minutes after the letter from not-Vanna White was slipped in the mail slot and onto the living room floor, what I already knew landing at my feet. I was afraid of being pushed down, of being held underwater.

Leave, my mother said.

When?

Now. Pack your bags.

Listen, my mother said, it’s like this. . . .

My mother said Listen, it’s like this often. Her summarizing was mostly about men but once she got sober her summarizing was mostly about self-actualization.

I left the ex that afternoon. I drove to an apartment complex near campus and failed to hold back tears in the apartment manager’s office. The manager had lollipop red hair and an inch of white roots. She said, We’ll take care of you. The studio apartment she assigned me looked out onto a parking garage.

For the rest of that summer, I would arrive at the boy’s house in the near dark, 6 a.m., and stay until 3 or 4 in the afternoon. He was too old to nap and was not to watch more than 20 minutes of television. Normal things I knew from babysitting similar families that year. I brought a bag of crayons, markers and sketch pads, encouraged by the babysitting agency, who gave me a bag with the agency’s name. They needed three references to hire me and I gave them the names of two aunts and my mother, all who had different last names than my own. I instructed my references to say I had babysat their children, which was true, but to not mention our relation.

Why not? my mother asked.

Because you are my mother. They think you are biased.

I couldn’t use the names of mothers I had babysat for who were not related to me because those mothers had long moved away from the apartment complex, in the transient way of apartment complexes. People rarely stayed beyond the one-year lease and often had to leave before the year was up, losing their deposit because the women had been fired from their jobs. Women lost their service jobs when their children were sent home sick from school and they had to call off too many times. Even if I had their contact information, though, I thought they were not classy enough — the language I used then — to impress the babysitting agency.

Always leave the house cleaner than when you arrived, the agency said. Offer the child something from your bag when you get there, so the parents see the child is excited to see you. This was how I learned to look like a nurturing, competent babysitter.

* * *

Midmornings babysitting I was tired — so was the boy. Afternoons we both gained energy from knowing our day together would soon be over. We went to the pool, we read books, we kicked the soccer ball, we made lunch.

What does your father do? I asked one day, wagering he would not tell his father about my rude inquiry.

He gives drugs.

Oh, I said.

* * *

As a child, when people asked what my father’s profession was I said he was a salesman.

What does he sell? the person — a teacher, a basketball coach — would ask.

Beauty supplies, I would say.

I might talk about when I was 7, this boy’s age, and how my father drove into Cincinnati, Detroit and once St. Louis to the strip malls with beauty supply stores, how he sold do-rags and acrylic nails, but the money, the real money, was in clippers. I told this story long into adulthood and made it a light story about a man selling beauty.

My mother was 28 when I was 11; my father was 30. As a child, he did not wear his retainer after braces, so his two front teeth were crooked, and one could see that his acne had been as pernicious as mine. My father carried acrylic nails in fake crocodile cases that shut with two brass latches. He was late for the sales appointments he arranged and smoked cigarettes in the Chevy Cavalier, speeding and cursing on the highway about the other drivers who were making him late. Once, in a motel in Michigan before a sales appointment, I told my father he had a very large pimple on his forehead. Fix it, he said. I applied my tinted acne cream. An hour later, in the storeowner’s office, as I sat in a chair looking at a “Calvin and Hobbes” comic the owner offered me, sympathetically, the pimple was bulbous and orange and did not match his skin tone at all, for which I felt responsible.

After the sales appointment, my father took me to a Chinese restaurant at a mall. The restaurant looked down on the first-floor shoppers and had black cloth napkins. That afternoon my father showed me how to place the napkin on my lap, how to use chopsticks — the pointer finger as the guide — and another day, which fork one begins a meal with.

You’ll need to know this one day, he said.

But I know how to eat, I said, possessive of the way that I had learned already while also enjoying the fanciness.

* * *

Pharmacist? I asked the boy.

Anesthesiologist, the boy said. It was a word I did not know.

The boy did not ask what my parents did because he was a child and had not yet learned the reciprocal requirement of the formally causal conversation of certain social classes. I found this aspect of children to be a comfort.

* * *

When playing with the boy, I thought of the ex. Had I acted too harshly, too abnormally, disappearing from the apartment without giving a warning? His coming home from work to me and all my things gone, calling and calling, until my phone’s mailbox was full. I felt excited when his number appeared on my phone, but I never answered his calls and I did not listen to the messages.

We’d moved in together rashly a year ago, the summer before, between my freshman and sophomore year of college. He had introduced himself by first and middle name because he thought his last name sounded too pedestrian. His band had just signed to Duran Duran’s record label, a detail he was not modest about sharing and in his attire, too, he effected Britain of a different era. I wanted to be that confident. He deepened his voice when answering the phone and ordering at fast food drive-throughs. People frequently thought, from his voice, that he was a woman. He had the most delicate fingers. In those days, in the middle of America, he was the closest to a woman I would venture.

I bailed on a shared apartment near the campus with my friends my sophomore year to live with him in a historic building in a neighborhood with sushi restaurants and cafes. My father said I was making a big mistake, that I was too young to live with a boyfriend and that he would not give me any money as long as I lived with him. If you are going to make adult decisions, you are going to pay for them, he said.

Once we lived together, my ex inquired why I did not wear dresses, why I did not wear tights, and asked if I wanted to cut my hair into a bob. I was to be the 1960s school girl muse. When this felt wrong, I reminded myself about his limp, an outward vulnerability that irritated him. As a young child, he fell down the stairs; his father did not believe it hurt as much as he said, and the bone healed incorrectly. A military doctor reset his hip but his legs maintained a noticeable length difference into adulthood. In the hospital bed as a child he watched the Monkees perform. It was his origin story of becoming a musician. I used it as an empathy touchstone when he was unkind. But we fought. He said things like, Only one of us in this relationship can be in a band. Commenting on my appearance or my friends was one thing, but attempting to squelch my ambitions was something I had been trained to see was very wrong. When my stepmother called and asked how I was doing, that my dad was wondering about me, I said I was great.

One warm June morning at the boy’s house the phone rang and the answering machine picked up.

Namaste, the answering machine said, in the father’s voice.

Hi, this is Kate. Call me.

An hour later, the phone rang again.

Hi, Kate again. Just call whenever you have time!

Mornings, these calls continued. Variations on the caller’s name and how unimportant it was that he call her. Until one day.

This is Kate. I’ve been trying to reach you. Why aren’t you returning my calls? Please call me.

The urgency of the woman’s voice unnerved me. The boy and I looked at one another as Kate spoke, then looked back at the television. In the gray living room, slurping cereal, watching the allowable 20 minutes of cartoons, we did not discuss this woman.

* * *

My ex called mostly at night, when I was at Larry’s bar with Keith, an older student who worked at the record shop and grew tomatoes on his rooftop. My ex, who played music around town, knew him and called him the Missing Link. Keith and I snuck into apartment complex pools after the bars closed and had Lucinda Williams sing-alongs with his friends. When his friends left and I held back, he told me of his fondest memories. His mother reading to him in a rocking chair before bed. Sweet, ordinary memories that were not ordinary to me and therefore alienating. He asked me to stay over. Though I wanted to, I said no.

Just lie with me, he said.

The Missing Link, I heard the ex say.

I returned to my studio apartment in the blue light of early morning, the air sweetened by the doughnut shop’s first batch. I broke my vegetarian diet at the sight of a gas station corn dog. The more Keith called the less I went to Larry’s. I was not ready for anyone to be nice to me.

* * *

By day I cared for the boy.

In July about a month into babysitting, the boy’s father called. He gave me an address and said the boy would be at a different house on Tuesdays and Thursdays.

It was a dark brick house on a treelined cul-de-sac. The rooms contained the things that would have felt homey and lived in if somewhere else— dishes in the china cabinet, rugs on the floors, a cat meowing from behind the laundry room door.

Where is your mom? I asked.

Upstairs.

When I looked upward, to the ceiling, the boy added: Sleeping.

She was always upstairs sleeping, but I met her once, near the end of the summer.

The boy was at the kitchen table and I had just turned on the overhead light. We were arguing over if he would read for his assigned mandatory 30-minute reading period a rhyming board book or an early reader chapter book. He wanted the rhyming board book, which he recalled from memory instead of reading. In it green alligators jumped. It was a stupid book.

So you’re the babysitter, his mother said, coming into the kitchen with an empty glass.

At the sight of his mother, the boy curled into and against her as if he were a cat.

The mother looked nothing like him. Where he was brown with dark eyes, thick as his father was, she was pale and thin, her face sagged, her skin nearly translucent, her voice weak. Even her smile was translucent.

The mother got ice from the freezer, a Coke can from the cabinet and poured the soda over the ice.

My mother taught me to sprinkle salt on my Coke, she said, sprinkling salt on the top of her glass of Coke. It makes it taste better.

She let her son hug her legs and waist, as far as he could reach. She patted his back.

After a while but not too much longer, she went upstairs.

Was his mother ill? Did she have cancer? Did the father give her drugs? Did the father feel guilty that she was addicted, guilty he was leaving her, and once when I saw him come by in the midday was it to ease her pain or his own? Perhaps instead it was the memory of my own parents scrambled up into the story I was telling myself about this family.

I was ashamed of my childhood, ashamed of my own stories. A casual conversation about family with a stranger gave me confusion and anxiety. Perhaps because of this desire to be rid of them, the memories came unbidden when I babysat the boy. My father had not called in two months and I worked through my memories to piece together where he might be.

Between junior high and high school, my father moved from an apartment into a house. The house grew full: a surround sound stereo, a large screen television and food he never had as a child. Steak, two knife sets, a pepper grinder, four champagne flutes, a pool table, a hot tub, a Cadillac in the driveway of the house he paid for in cash. He was gone in the evenings and early mornings and slept until the afternoon. He had stacks of twenties and hundreds wrapped with produce rubber bands in his top dresser drawer, which I found when I was looking for a pair of socks to take to basketball practice. When he was home, my father’s house was a revolving set of men. In they came light, handling the faux leather briefcases that once held beauty supplies. Out they went 15 minutes later. I missed seeing the women on the acrylic nail packages.

His work in an underground economy gave me money for braces, books, Accutane, aspirational clothes, standardized tests and college applications. When I completed my FAFSA he made $13,000 annually from his work as a beauty salesman. My father’s money gave me access to basketball camps, where I studied parents distinct from my own who went to every practice and hovered over their daughters with sports drinks, sandwiches and praise. My father would appear after a game and say loudly that I was robbed of some ref’s call, but for the most part my parents left me to my thoughts. At night if I was bored, I knew what bar to call to ask when my father was coming home.

Meanwhile, my mother lived in the Section 8 apartment complex on the other side of town that I thought of as home. Once when I was in high school, my 7-year-old brother called his dad and said our mother was in her bedroom with the door locked. Her ex husband, whom she had separated from years before, broke down the door. He slammed his pistol against her arms and legs. My brother stood in the doorway of our mother’s bedroom and said, Dad. Please. When his son touched his arm, he put down the gun. My mother prosecuted.

I quit coming around much, despite knowing what my brothers were witnessing. The guilt would get in the way of my achievement. I worked it out of my mind.

* * *

One day in early August, I arrived to the green house and the father was in a room I never entered. The door was open. I saw a pillow on the floor, a Buddha statue in the corner, a sliding glass door. It felt quiet in the house then, peaceful, and I was jealous or inspired or a combination. I could not tell the difference. I knew the Buddha from a comparative religion class. I did not know about the association with American wealth.

Sorry, he said, apologizing for not greeting me at the door. I was meditating.

I wanted to fuck the father. I was not sure why. It was a vague wish. What I wanted was his desire and my domination of his desire. The Amanda or the Kate on the phone wanted him, too, and he still was not returning their calls.

Or maybe he was. The women no longer called in the mornings. Was he a newly divorced father with a dying spouse, who meditated and worked at the hospital, or a doctor with power, slowly killing his wife with drugs while he went out with Kate?

God rest your sundials, permit what has blossomed to rot on fruit or vine, whoever is alone now will always be so. That was what I remembered from reading that summer of other people’s children and other people’s lives, who knew nothing of my own. I drank their infused water, ate their organic berries, listened with strained attention to their classical CDs, studied their houses and gleaned what ascension looked like.

The summer came to an end. The boy’s regular nanny returned from her pregnancy leave. He started second grade. I started my junior year of college. I rarely thought about the boy and the father. My father came back from his trip. When I came home for Christmas my junior year of college I noticed there was a hole in the hallway ceiling near his bedroom. The reason for the hole haunted me, but I never asked about it.

By the start of my senior year, I moved out of the studio and back in with the ex. I worked part-time at an optical shop billing insurance companies. The ex worked as a therapist for autistic children during the day and in the evenings sold vintage synthesizers on eBay that were already broken but which he claimed, when the buyer complained, had been damaged in shipping. His reviews on eBay were poor. He asked to use my account. We acquired a Saint Bernard. I told myself I’d take a year off from school and accepted a full-time position at the optical shop. I graduated from college.

In the fall of my first year with a college degree, the optical shop smelled like cow manure. Across the street from the shop was a field, the final grazing place for the cows before slaughter. On one of those fall, peat-mossy-cow-manure mornings, I looked up from my desk through the reception window to see a familiar brown face, a cute twirl of front teeth. The father.

How are you? he asked.

I felt myself newly in my body, corporeal. It was a word I learned from studying for the GRE, because I, the babysitter, was getting out of Ohio.

When the father asked how I was I said, I’m good, not thinking of how I actually felt. One was good or one was well, if they wanted to be hoity-toity, but one was never bad or terrible, and one never told a bad or terrible story, unless one was peculiar, which was frowned upon.

How are you?

He answered within the acceptable range. He was smiling. And then he added, But his mother died six months ago, and frowned and motioned behind him to the boy, who had been there all along, a large distance from his father.

I’m sorry to hear that, I said, saying what I said before I had lost a child, before I knew what loss was.

This boy was 7, maybe 8, and now he was 9 or 10, and he wore the same green T-shirt and striped shorts from the summer I babysat him.

Someone behind the father said, Excuse me. It was a woman wearing frameless glasses with orange temples in a durable, lightweight, surgical-grade plastic — I still remember the marketing language for that brand — and a thick gray bob, the usual customer to this boutique eyewear store. I wrote the woman’s name on the sign-in sheet for her two o’clock appointment.

The father took a step back, said, I’m sorry.

I nodded no, as if to say, no need to apologize.

I told the woman to make herself comfortable.

An optician fit the father’s glasses. The optometrist handed me a prescription. The phone rang.

The father slipped farther and farther away, until he was waving goodbye, until he was out the door, down the sidewalk and out of the parking lot.

The woman chose her glasses and left the store. I was at the desk processing insurance claims when the store owner put his hands on my shoulders and gave a lingering squeeze.

How’s it going? he said.

Before I worked here I was the babysitter for the owner’s children, too. When he sat on the sofa and tied his shoes before leaving for work, I watched his arms flex and looked away when he noticed my looking, but looked back to see him smiling to himself.

Good, I said.

He had never put his hands on me in this way. I had given my two week’s notice that week.

I stiffened and did not look up from the insurance paperwork. Now that he was offering what I thought I wanted, I knew it was not what I wanted. He was a proxy for what I wanted — my own power — and acting on his request would only slump my position further down the ladder I was climbing. He lifted his hands off my shoulders.

The front door jingled open. I heard his shoes on the carpet and his welcome to a new customer.

Well, I said to myself.

Well, I repeated, a correction I would make again and again.

* * *

On one of the last days of that summer with the boy, I took him to the country club swimming pool. It was early for me, perhaps 10 a.m. and the air was not yet suffocating. I was tired and hung over from a night out. The pool was not yet crowded. The boy asked me to play in the water with him, and I kept putting him off, saying, In a minute. I wanted to read a gossip magazine and ruminate about my ex. I wanted to close my eyes under black sunglasses.

Please, he asked.

I got in the water, but only up to my waist.

He wore water goggles. I tossed sinking toys into the water and he dove and caught them.

Come down with me? he asked and pointed to the slide.

I shook my head no. It would mean that I had to walk across the pool and climb the stairs and slide down and anyway wasn’t a pool in summer designed for parents and babysitters to have some quiet time alone while a lifeguard made sure everyone did not drown?

I’ll watch you from here, I said.

After a few more pleadings, he got out of the pool and walked across the edge of the water. I saw another woman, a mother, with her child in the water. They were having so much fun. She smiled into his face and lifted him into the air.

The boy turned to look back at me to see if I was watching. Inspired, in a melancholy way, by the mother, I smiled and waved back. When it was his turn, he looked to me and I waved again. He slid down fast, slid under the water, and I like to think that when he came up I had swum across the pool to meet him.

But I’m not sure if I did.

* * *

Warshing the dishes ended with my father’s Appalachian accent. I uprooted it from my lexicon. He rarely leaves his house and men do not appear with briefcases. The hole in the hallway is patched up. He has diabetes and tells certain stories over and over. He smiles and drinks beer as he tells them. The saddest one goes, I knew I raised my daughter right if she never came back.

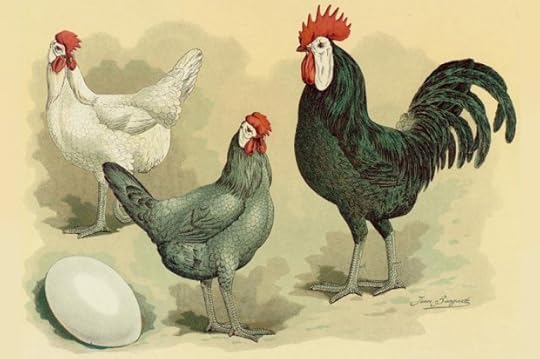

The legend of Big Chicken

(Credit: Wikimedia)

I’m in Tennessee visiting my family for the holidays. I lived here until a few years ago, on a chicken farm only a mile or so from where I sit writing this. The farm is gone now; the family has moved closer to town, but my memory of the years we spent there is strong.

In fact, that’s me in the photograph, feeding the chickens one afternoon. And yes, that’s a smile of pride brightening my aging visage. The truth is, I loved those chickens. We averaged about 200 of them every year, eight or ten different breeds who laid eggs in about seven different colors: white, brown, blue, green, olive, pink and a deep mahogany the color of a CEO’s desk. We sold them to a local organic food place in Nashville called the Turnip Truck. Our eggs flew off the shelves. One reason: Parents snapped them up because kids loved to pick out their own special eggs in the morning. Plus, they were actually good for you.

The chickens lived in two chicken houses I built, one of them on an old steel trailer I traded for a .22 Luger pistol over in Murfreesboro. Our two flocks had the run of about three acres around the house. They would gallop down the ramps out of the chicken houses in the morning just after dawn, when the ground was still wet with dew, and immediately start pecking at worms that had emerged overnight. Then it was off to the races, eating-wise. Caterpillars, seeds, ticks, mosquitoes, the occasional butterfly and even a nice fat lizard every once in a while. Then at dusk both flocks would make their way back to their chicken houses and we would lock them up for the night against predators. Same thing all over again the next morning, and the next and the next and the next.

It was a farm, and they weren’t pets; they were livestock. But we loved those chickens, and it hurt when a hawk or a fox or a coyote would take one of them, leaving a pile of feathers where once a proud hen had strode the land. We would replenish the flocks once a year with a shipment of new chicks from a supplier out in Iowa, and raise them up and introduce them into the flocks, and our lives and their lives would go on. Legions of words have been marched across the page over the years describing life on the farm . . . the seasons . . . the animals . . . the backbreaking labor . . . the thrill of new life and the heartbreak when lives are lost. I can attest that every single word ever written about farming is true. You love it and hate it in equal measure, but one thing is for sure. A farm replenishes you every single day like almost nothing else on the earth.

We took an oath right from the beginning that we would follow the law of the farm and not get too close to our chickens, because we knew we would lose some of them and moving on would be necessary. For a long time, we followed that rule absolutely.

Then, late one afternoon on a cold February day, I was standing at the kitchen sink slicing vegetables for dinner when something caught my eye. There were three windows in the kitchen: one above the sink, one in the back door and one in the kitchen breakfast nook. I leaned over the sink and took a good look out the window. There were always chickens in the side yard, and I didn’t want to be day-dreaming if a hawk or coyote were menacing the flock. But there were no signs of a predator. The chickens were pecking away; the roosters weren’t sounding off; the peacocks were sashaying around showing off and not announcing a threat with their incredible fog-horn voices. I went back to slicing.

There it was again! A flash of something caught my eye. I looked out the window. Didn’t see a thing. Again! I saw it again! OK, I thought. I’m not imagining things. I stood there at the sink and turned my head so I could see it plainly, whatever it was. And then I saw her. A chicken was sitting on the top fence rail just to the right of the kitchen door and she was jumping up, flapping her wings wildly, then landing atop the fence. She did it again! And this time I saw that she had her head turned and she was looking in the window. She did it again! I tried to force the thought from my mind . . . she was a chicken after all . . . but it was obvious she was trying to get my attention.

So I walked around the counter and opened the back door. It was a White-Faced Black Spanish, quite a regal black bird with a flash of white on either side of her head. When she spied me at the open door, she immediately flew down off the fence and marched straight over and hopped up the back steps and walked right past me into the kitchen, clucking softly to herself. She walked a few feet into the kitchen and spread her wings and fluffed her feathers and looked straight up at me, clucking. I walked over and picked her up and held her under my left arm and stroked the back of her neck.

“What are you doing in here, big chicken?” I asked stupidly.

She clucked and I could feel her muscles relax under my arm. I grabbed a kitchen towel and walked into the living room where the news was purring on the TV. Sitting down on the couch, I spread the towel across my lap (chickens have a habit of depositing poop wherever they are, including your lap, so it’s necessary to protect yourself). She didn’t hesitate for a second. She thrust her legs straight out behind her and lay herself out, extending her neck across my right thigh, and she went right to sleep.

I don’t know how long I sat there like that, stroking the back of her neck. I was astounded, struggling to wrap my head around the behavior of this gorgeous black chicken. It was as if she knew exactly what she was doing . . . as if she had a plan or something . . . and now she was where she wanted to be. Not outside in frigid February weather, but inside, on my lap, comfortably warm and sound asleep.

After a while the kids came downstairs and saw me sitting there with her. No chicken had ever behaved like that before. It was charming and wonderful in a way that’s hard to express. And it definitely wasn’t farming. Then the kids got hungry, and I had to pick her up and carry her outside and put her back down among the flock and get back to cooking supper.

You can no doubt guess what happened the next afternoon. Same thing. Big Chicken — yes, our whole farm-rules thing fell apart and we named her — jumping up from the fence, looking in the window. Me opening the door, she marching in, clucking and fluffing. Me picking her up and carrying her into the living room. She going to sleep on my lap.

This went on for a couple of days, and then one afternoon I went out to get in the car and drive down to the end of our private road to pick up the kids from the school bus. Big Chicken was waiting for me and jumped into the front seat of the car and quickly took a spot in the passenger foot well. She rode down to the corner with me, I parked and picked her up, and together we waited for the bus. When the kids got in, she happily took her place on the floor and we drove back to the house, parked, and we all got out. Big Chicken included.

Our little journey to the corner together continued for I don’t recall how long — maybe a couple of weeks. So did our sojourn on the sofa every evening: Big Chicken happily snoozing on my lap, me watching talking heads babbling on MSNBC. Then one afternoon, Big Chicken wasn’t outside the window jumping up and down. I went outside and looked around for her but couldn’t find her anywhere. Maybe she was just hungry, still pecking away for food. Next day, same thing: no Big Chicken.

We knew what happened. Big Chicken was among the breeds who like to sleep up in trees at night. Rare breed chickens are way smaller and lighter than conventional American chickens, the kind you see pictured on egg cartons. They can fly for short distances and they can reach the lower branches of trees where they perch for the night. Only one problem: owls. We had lost tree-perching chickens to owls before, and so it was that we lost Big Chicken. I have to tell you, it was heartbreaking. That chicken was something to behold, and her behavior was so out there, you couldn’t help but love her. We never found her body or even a pile of feathers, which wasn’t uncommon with owls. They would often carry off their prey and have their meal somewhere else. But we never forgot Big Chicken, the hen who caused us to break our farmers’ pledge and drop our guards and take her as a pet.

I don’t think about Big Chicken all the time, but the memory of her came to me recently as I was contemplating our behavior as boys and girls, men and women — even those of us who are older men and older women. Isn’t that a bit like what we do? Jump up in the air and fluff our feathers, trying to get each other’s attention? Isn’t that what we were doing, really, when we walked down a school hallway gazing longingly at the gorgeous girl standing at her locker or the cute guy hanging out on the steps of the A Building? Didn’t we look down the bar on a winter night and see each other and long to be in each other’s arms on a nice comfortable sofa? Isn’t what we’re doing online, jumping up and down and trying to get a look through each other’s windows? Laptop screen, smartphone, tablet — it’s all glass, all windows into worlds we would rather be in than the one we’re stuck in.

Isn’t that what we all want? To be Big Chicken? To be taken inside where it’s warm and cozy and to lean our heads on another’s shoulder? Could it be true that we haven’t evolved much beyond a White-Faced Black Spanish hen on a Tennessee chicken farm? And really, isn’t that quite wonderful?

I’m a retired chicken farmer, and that’s what I think.