David Michael Newstead's Blog, page 9

July 15, 2024

July 12, 2024

Things in Used Books

David Michael Newstead | The Philosophy of Shaving

Inscription inside the biography of a newspaper publisher:

Happy birthday, Grandma. Love, Tim.July 4, 2024

June 24, 2024

Things in Used Books

David Michael Newstead | The Philosophy of Shaving

An inscription in The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger:

Hello there loser! Thanks bunches for letting me use your book, I had to write an essay. Sad I know!Inside Neuromancer by William Gibson:

A concert ticket from 6/3/2002A movie stub from the 2002 film, Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron for the 2:10 PM showing on Friday 5/24/2002 at AMC Parkway Pointe in AtlantaJune 22, 2024

June 5, 2024

Tuberculosis in America

David Michael Newstead | The Philosophy of Shaving

Tuberculosis was once widespread in the United States. Even as the death toll declined overtime, it still killed 99,000 Americans in 1925, 33,900 in 1950, and 9,300 in 1963. Transmitted through coughing, the so-called White Plague was rampant in marginalized communities who were excluded from adequate medical services and more generally relegated to crowded, unsanitary living conditions. Because effective antibiotics were not developed until the 1940s and ’50s, reading about the treatments for tuberculosis in the first half of the century feels very Dickensian: bed rest, special diets, odd surgeries, and prescriptions for fresh air. This took place as the patient became thin and frail, weaker and more far gone. Many people didn’t survive.

Famously, the British author George Orwell died of TB, having been diagnosed at the end of 1947 and succumbing to the disease in January 1950. I believe Elizabeth’s ordeal followed a similar timeline from 1924 to 1926. In North Carolina specifically, the climate and the mountain air inspired the establishment of tuberculosis sanitoriums across the state, but it’s unlikely that Elizabeth’s family could have afforded such a facility. And as black Americans in the Jim Crow South, it’s even less likely they would have been welcomed at one.

According to one study, between 1910 and 1934, African American death rates for tuberculosis were more than triple that of white Americans nationally and sometimes 6 or 7 times greater depending on the location. So in 1926, the year Elizabeth passed away, that equated to 224.8 African American deaths from tuberculosis per 100,000 people. This made TB one of the leading causes of death for African Americans during that time period. And while statistics can be informative in one sense, they’re dehumanizing in another. Elizabeth was one of these patients. Hers is an identifiable, relatable story, but every number tallied here is an individual life stolen by illness and aided and abetted by society’s neglect.

Elizabeth’s condition would not have been difficult for doctors in her area to diagnose. In 1924, there was a documented rise in TB cases throughout North Carolina and she was among them. After her diagnosis, she was likely quarantined and spent the remainder of her life resting and hoping for a recovery that never arrived. One possibility I recently considered is that the reason all her friends’ mailing addresses were scribbled into her history textbook might have been so they could write letters to each other while she was out sick. Classes at St. Augustine’s School were fairly small and close-knit, so the sudden departure of another student would have been a big deal. One can only hope corresponding with her friends was a feature of her final days. For her family though, they could only look on as their daughter slowly died like so many others.

June 3, 2024

May 29, 2024

The Trajectory of a Book

David Michael Newstead | The Philosophy of Shaving

The book followed an unknowable path to get here. That began when this 730-page edition was published in 1914, the byproduct of two white American academics charting the history of Europe and the ancient world. James Harvey Robinson was a historian, James Henry Breasted an Egyptologist. Then, around 1923, a young black college student purchased the book for her history class at St. Augustine’s School in Raleigh, North Carolina. She took a pen and signed her name in bold ink along the interior edge of the cover’s endsheet. It reads – Elizabeth.

Elizabeth’s book is decorated with extensive notes in pen and pencil, cursive and print. Some of that has faded overtime, but her writing is still quite clear. The inside of the book also contains photographs, a postcard, and a letter as well as miscellaneous slips of paper. All these things provide a detailed, but incomplete jigsaw puzzle of this young woman’s life up until April 1, 1924. Tragically, Elizabeth’s college career was interrupted by tuberculosis and she eventually succumbed to that grueling illness at 20-years-old in 1926. In the aftermath, this book would become an unofficial time capsule and a snapshot of her life when it was still so full of potential. As far as I know, the rest of her personal belongings and any of her writing were lost to time except for this one object. Even contemporary databases only have minimal information about her and her family.

One of the questions that’s dogged me is what happened to this book for a century before I picked it up at a store’s sidewalk discount sale for $4? All I have are theories or, at best, educated guesses. Using records online, I’ve traced a number of possible trajectories as Elizabeth’s loved ones relocated over the years. Because the last of her immediate family members died in the 1950s, I searched under the assumption that other names referred to throughout her book are people who were most likely to have kept it. That may or may not be true, but there’s really nothing else to go on. Roderick, Foy, Fannie, Mrs. Mittie, Eugenia, Warren. Several stayed in North Carolina, but amidst their general movement North to Connecticut and New York, the book might have gone in that direction with them as reading material or a cherished personal keepsake.

The mystery is that none of the book’s identifiable prospective caretakers lived beyond the mid-1980s, which was six decades after Elizabeth’s death and forty years before I found it. That’s a very long time for it to be shuffled around different cities and boxes and bookstores. All the while, everything personal and significant placed between those pages sat undisturbed. I’m based in Washington DC, so whether the book spent all that time in North Carolina, New York, or somewhere else, it eventually made its way here. Perhaps one unknown elderly relative could have helped bridge that gap, but, at some point, the contents concerned a person even they weren’t likely to have ever met.

In reality, most books sit idly by and unopened most of the time. Could this have been one of them? In the last four decades or more, is it possible that no one looked at this book? I wish I knew. A multi-generational journey that I can only guess at brought this book to the present-day, almost exactly a hundred years from its last dated entry. That story contains everything written and unwritten about American history and about the lives of the people who held this object in their hands. Somehow, I have it for the time being, but, no matter what’s on the horizon, it’s always going to be Elizabeth’s. It always was.

May 20, 2024

American Time Capsule: 1924-2024

David Michael Newstead | The Philosophy of Shaving

My most random hobby is finding things in old books. Usually these are notes or bookmarks or little glimpses into the lives of the book’s previous owners. And as thought provoking as some of my past discoveries have been, nothing can compare to what I found this weekend. On Sunday, I was casually looking through an outdoor discount bin when I picked up Outlines of European History Part I by James Henry Breasted and James Harvey Robinson. This is a really beautiful book on western civilization from 1914 and the interior is basically an intact personal time capsule about one young black woman who attended college in the 1920s.

Elizabeth went to St. Augustine’s School in Raleigh, North Carolina, a private historically black Christian college that still exists today. She was from Chapel Hill and scattered throughout the book are her notes from history class written in the margins, a sheet of her math homework, various names and addresses of her friends, a postcard, a letter from her parents, and an envelope filled with photographs of St. Augustine’s students. A few pages are stained from the notebook paper that’s been wedged between them for a century. Sometimes, Elizabeth’s notes are written sideways or upside down, demonstrating that her history book doubled as a journal, notepad, or personal organizer whenever necessary.

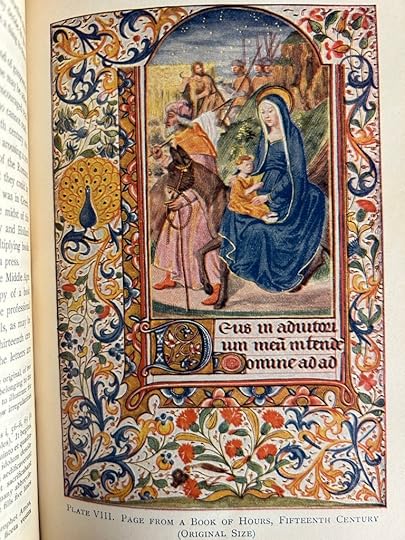

The book itself has great illustrations and covers a wider scope than the title might imply including Egypt, Babylon, Ancient Greece, Persia, cultural centers across Europe, and various religions as well with an impressive rendering of Mecca. On the back of one glossy page, Elizabeth wrote down some of her thoughts on life or perhaps notes from an inspirational lecture or sermon. It reads:

1. Life is what you make it

2. Climb through the rocks be rugged

3. Am I my brothers keeper?

4. Opportunity

5. Universal Peace

6. Lifting as we climb

7. He can who thinks he can

8. Capital Punishment

9. The Road to success is lush

10. Excelsior

Elsewhere in the book, there’s a folded piece of paper that was probably an inside joke passed to her during class:

Smiles, you stop making that noise.

All but one of the photographs inside were processed at Siddell Studio in Raleigh. There are faded pictures of four boys in St. Augustine’s apparel. Two are sitting on a stone wall. And three of them are posing by a tractor. One boy appears twice. Were any of these gentlemen Elizabeth’s boyfriend? It’s hard to say. The last photo is smaller than the others and has been cut or torn from another location. It shows a pretty and smiling young woman who I believe is Elizabeth.

Elizabeth’s parents wrote to her on Monday night March 31, 1924 in a letter that’s postmarked April 1 at 7:30 am. The stationary was purchased at R.W. Foister Stationary and Kodak in Chapel Hill. Neither of her parents had above a sixth grade education and they were writing to their daughter in college. Below I include excerpts from the letter that stood out to me for social and historical significance, but I’ve omitted people’s last names. Her mother wrote:

My Dear Daughter,

Your letter received found us up and on the job as we will; but always tired, we were beginning to feel a little uneasy thinking you were sick. Glad you are well and trust you will continue. I didn’t think the vaccination would take since your arm was so bad last year. The measles, mumps, and whooping cough is raging around here. Old Roderick is running the extractors at the laundry. I don’t know how long he will stay. I guess Ed has gone to Baltimore he has gone somewhere… …

You say you weigh 125 lbs. The next news you know you will be a big “fat woman” crowding your drawers, ha! ha! You had better look out.

Elizabeth’s father wrote his own separate page to her after some teasing from his wife:

The O.C.J. school closes about May the 15. Your brother is doing very well, but plenty room for improvement. The Pylicans had a parade yesterday and I saw Mrs. Mittie at church, but forgot to tell her you dreamed about her. I have seen Fannie and Foy and told both of them what you said. Old Foy just cackled. I haven’t seen Ragalee since I heard from you. The days are growing longer and the nights shorter and it is beginning to get warm. I am tired and getting sleepy too now so I will say good night. Be good. Take care. Papa.

Then, her mother returned at the end to close out the letter:

Cousin Eugene and her Shark sends love, also Mrs. Eliza, Old Flassie, Viola, and several others…

With love and best wishes,

Lovingly Mother

There was a gap of a several hours between when I first poured through the contents of this book and when I finally got home and was able to research things more extensively. In between, I found myself wondering about Elizabeth and what kind of life she led in the ensuing years. I imagined all kinds of possibilities. And even though I didn’t realistically expect her to still be alive, what I learned later that night changed my whole impression of this artifact.

The information contained in this book stops at the end of March 1924. Elizabeth’s younger brother died from meningitis at age 16 in the middle of April that year about two weeks after the letter was sent. Not long after that, Elizabeth passed away at 20-years-old in February 1926 of tuberculosis. I admit I was taken aback by this and it shattered whatever expectations I had although maybe it shouldn’t have. Elizabeth’s mother talked about viruses ravaging the community. And local newspapers at the time called it an epidemic.

I had to reflect on all this and what it meant. Honestly, I’m still doing that. Elizabeth’s parents lived for another 20 and 30 years with her mother spending her last decade on Earth alone, the last member of her immediate family. That poor woman. I understand it’s not particularly relevant to this, but my father died of meningitis. That was sudden and horrific in the 1990s. How much worse would it have been in the 1920s for a southern black family? The papers only hint at the scale with several death notices throughout the year of her brother’s passing. And I strongly suspect that none of those notices were for black people, which would obscure the true toll of the outbreak. In contrast, tuberculosis is a slower, more heart wrenching killer. Elizabeth’s illness referred to in the letter might have been the earliest symptoms.

Everything else I have to say is really just speculation. I went back and searched for some of the other names that were mentioned, hoping to find an identifiable relative who would maybe want the book and the letters. The larger mystery though is the story of the book itself. Who would have kept it for so long with all these things in it? And then how did it end up at a used bookstore? My only real theory relates back to that envelope full of photographs. Instead of Elizabeth’s address on the back of the envelope, it was for someone named Warren from Chapel Hill. Was he one of the boys in the picture? And if so, did he save Elizabeth’s history book after she died? I don’t have an answer. All I know is this collection of things stayed loosely bundled together for a hundred years. And any answer I consider about someone who knew and loved Elizabeth for the rest of their lives still couldn’t account for more recent decades. The likeliest possibility is that sentimental items get saved, then end up in a box in basements or attics. Eventually, it’s all too much and whoever is left to go through a lifetime’s worth of stuff just donates it all, because everyone who knew what it was is gone.

In spite of that all too common phenomenon, not everything is lost. Pieces of our lives endure just as Elizabeth’s life endured. She was from Chapel Hill, North Carolina. She went to St. Augustine’s. She was studious and happy and someone somehow held onto her memory for as long as they possibly could.