David Michael Newstead's Blog, page 6

December 5, 2024

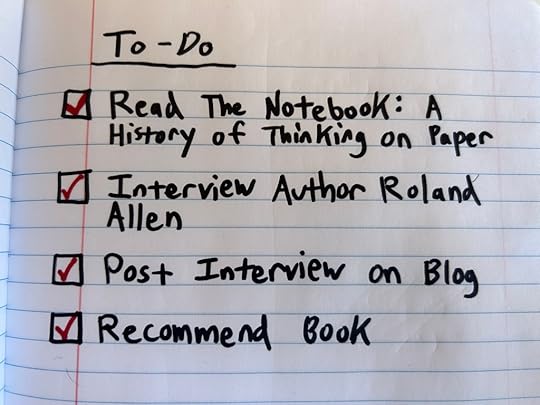

Interview: A History of Thinking on Paper

David Michael Newstead | The Philosophy of Shaving

The Notebook: A History of Thinking on Paper was released in September and it’s a fascinating exploration of the origins, highlights, and dynamic story of notebooks. Like a lot of people, I love my notebook, so I was eager to chat with author Roland Allen and hopefully learn something new about a fixture of daily life. Our conversation is below.

David Newstead: What surprised me is that I think I had taken notebooks for granted. You know, it’s hard to imagine the world without them. Cavemen didn’t have them, I know that. But I didn’t give much thought to the origins or any of the history behind it. So, it was very interesting for me to unpack that.

Roland Allen: Yeah, that’s very much where the book came from. This realization that we have a very simple, ordinary device, which somehow is invisible to people. They use it all the time, but they never really think about where it comes from or the fact that it might have a history.

David Newstead: If you had to estimate, how many notebooks would you say you have right now versus how many notebooks would you say you’ve had throughout your whole life?

Roland Allen: Well, I now use many more notebooks than I used to. I know from researching notebooks how to use notebooks more effectively and essentially the answer is often just use more of them. Because then you separate your notes from different pockets into different notebooks and they’re much easier to organize.

I’m working on another book at the moment and it’s basically one notebook per chapter. So, it’s about 10 notebooks, which are in active use just for that one book. But then looking back on other things, I’ve got 25 years of diaries. I’ve probably got about another 10 or 15 full kind of creative notebooks I guess and sketchbooks. It’s a stack. It’s not comical yet, but it will be quite soon!

David Newstead: Looking at the history you layout, could there have been a Renaissance without notebooks?

Roland Allen: It would have been very different. You’ve got two factors with the Renaissance I think. First thing, you’ve got the cash which is going around. So, this pays for all of the churches and the paintings and I guess the universities too, while you have these people researching humanist texts. Italy wouldn’t have been that rich if it wasn’t for its bankers and merchants and they needed notebooks to do their bookkeeping to make the money. So, I think that’s one important thing. The economy of Italy would have been completely different without notebooks. And I think that’s fairly uncontroversial.

And then the other view that I have, which is unproven or unprovable, but I strongly believe it, is that the actual visual artists we think of as Renaissance masters, they all learned how to draw I think on paper and probably in sketchbooks. And we know this, because they tell us that they did. I mean, Leonardo da Vinci said the way to learn to draw is to draw a lot in a notebook and always take a sketchbook with you. Another Florentine artist earlier says a very similar thing. Vasari, when he’s writing about the lives of the great artists, talks about them constantly drawing on bits of paper and in books. So, although we don’t really have the proof that that’s where they came up with things like perspective and realistic drawing and hatching, cross hatching. I don’t know if you draw yourself, but hatching is a really important technique. No one seems to have done it before about 1300 AD. So, I’m trying to convince myself that the sketchbook is crucial from a visual point of view, but the notebook definitely is from an economic perspective.

David Newstead: Well, I have to say some of the artwork and sketches and things you put together from those different notebooks from the Renaissance and beyond really stood out to me. To see the progression was really interesting. Were there any historical examples that you saw or read about that were your favorites while you were working on this?

Roland Allen: Yeah. The problem I had with the book was keeping it down to under a million words and making it short enough to lift. Because every time I got into a notebook, I realized that I could basically write a whole book about it. But I guess, from that point of view, my favorites… the ones I really loved getting into it.

There’s the notebook of Michael of Rhodes who was a sailor from Venice around the year 1400 AD on. He had a very, very humble upbringing and he really dragged himself up by his bootstraps. I mean, possibly he might have been a slave as a boy. And by the end of his career, he was commanding fleets of the Venetian Navy, which was one of the most powerful navies in the world actually. So, he had this incredible career. He kept a notebook. It wasn’t a diary, but he collected things which interested him. He was fascinated by mathematics and arithmetic and math problems, so it’s full of things little mathematical brain teasers. It also has the signs of the Zodiac and his horoscope and prayer. It has instructions on how to sail from Venice and all sorts of routes he should take. And it has his resume, his curriculum vitae. And I think part of the reason he kept this book and made it was to show off to people his intelligence and his knowledge, his professional expertise and his career, so that he could go for a job interview, in effect, show them this book and say “I’ve worked here, here, and here. These are the captains I’ve sailed with. These are the people I know.” He would have used that experience and used his notebook to get his next job. So, I loved Michael’s notebook. After I had studied it for a while, like a lot of people, I really loved him. I thought he was an amazing character. It really came through. And notebooks do have this ability to bring their users to life, which was really lovely. In fact, I really enjoyed it. That’s one I really liked. And that’s very obscure.

A very well-known example, I thought of Darwin’s notebooks from his trips around the world with the Beagle. You have these tiny, tiny, very scrappy, very messy, little notebooks from the research trips he made. They’re tiny like literally the size of a deck of cards or an iPhone or a pack of cigarettes. That sort of size. He collected 14 of them and then, from the notes he made in them, he worked them up more neatly and used them with resources in his library. They led directly to On the Origins of Species by Means of Natural Selection, which is one of the most important scientific breakthroughs of all. So, you have this tiny collection of notebooks which would fit quite easily into a shoebox and they are the underpinning of this scientific idea, which nearly upends the way we think about everything.

David Newstead: Either from your work on the book or from book talks and interviews, what do you find is the most common misconception that you have to push back against?

Roland Allen: I wouldn’t say there are misconceptions. People love their notebooks and they are excited to know that there is a history to them and that they’re part of a tradition, if you like. So, I don’t really think that people have misconceptions about them, but I think people are always delighted to be surprised by what they didn’t know.

I’m always surprised by how late in the day people start keeping daily diaries, because it’s such a normal thing for us. The idea of a diary is very normal, you grow up with it. Even if you don’t keep a diary, no one thinks it’s a freakish thing to do. But it arrived very late in the day. People have only been doing it for about 400 years, which I find very surprising. Because it’s a very obvious thing to do if you have a notebook, I would say. So, that’s very surprising.

A lot of people instinctively feel that writing notes by hand is better than typing notes on a machine or a computer, which is the case. And we can now sort of prove it, because of all the scientific research into notetaking now. And people always like that as well. So, I wouldn’t say there are misconceptions, but there are areas of ignorance that people just don’t know about and people are always very happy to learn about.

David Newstead: For obvious reasons, I know why the book leans heavily on Italy and Western Europe and places like that. And I do recall the story in book about the Vietnamese cookbook. But can you speak at all to anything you might have researched or found regarding notebooks in oral traditions or indigenous cultures or just non-western origin stories?

Roland Allen: I think one of things that makes a notebook a notebook is that it has to be paper. It can big or small. It can be long or short. It can be four-pages or it can be hundreds of pages. But for me, it has to be paper. Paper has qualities that nothing else has, you know. It’s permanent. It’s very durable. It’s bright white. And you can mass produce it.

So, I did a lot of research into the history of paper. And one of things which really surprised me is I couldn’t find it at all Arabic notebooks from the period before paper arrives in Europe. And I was utterly baffled by this. I work on the assumption that because they had paper in the Muslim world in the Caliphate, which was huge and it stretched all the way from Baghdad in the East to all of North Africa and most of Spain as well. They used paper all the time. And I’m sure that they had notebooks, but could I find any? I could not find any. And I spoke to really distinguished scholars in that field and they didn’t know of any either. And I was looking mainly at people who were Arabists or experts in Persian culture, because Persian culture really informs the Caliphate in this period. I found out much later that I was actually asking the wrong people. So, I wrote the book and it says at the end like “I’m baffled by the fact that I can’t find any Arabic notebooks. I can’t. You know because I’m sure that there’s a story there.”

And then, quite accidentally, I spoke to an expert in the Ottoman Empire which followed the Caliphate and was another Islamic Empire. And basically because the research is so much better in Turkey, I suddenly then found instances of people keeping personal poetry notebooks and notebooks of proverbs and things, which are very, very similar to zibaldoni which I wrote about. So unfortunately, this was too late and it didn’t go in the book. I’m glad I found it, but I wish I found it a year earlier. So, there’s definitely a whole Arabic culture or Muslim culture side of the story which is there to be told.

Now, where else does paper come from? It comes from China originally. It went roughly speaking from China to the Muslim world to Europe. So working back on that, you’d think that the Chinese would have had notebooks and again I’m sure that they must have. But I sat down with a Chinese researcher who speaks Mandarin and Cantonese and again it was impossible to work out the archives. It turns out that although the Chinese invented paper, they didn’t use paper for writing for a really, really, surprisingly long time. Like hundreds of years, it wasn’t that common to write on paper. I mean sometimes they did, but the most common uses for paper were for other things like wrapping parcels or they used it as a building material. So, they didn’t have notebooks. They used different things, which were made out of strips of bamboo. They didn’t really have paper notebooks. And it’s quite interesting that all of the words that they now have in Mandarin Chinese for exercise books and ledger, for diary, etc. They’re very recent words. They came in when Westerners turned up with their own paper notebooks. So, it seems as though they didn’t really use paper in the same way as we did in Europe. Although again, massive caveat, I just couldn’t find out about it. I tried as hard as I could. But there will be Chinese scholars out there who will probably be screaming at me.

So, in the book, I’m not talking about a world story. I’m talking about a story that starts in Europe and then takes over the world, because it does. Particularly, the way we use financial records. That really did take over the rest of the world in due course, for better or worse. So, those are the areas that I think other people should look at.

David Newstead: Thank you for that explanation. It’s very…

Roland Allen: Very long and tedious haha…

David Newstead: I mean, it’s an important question. It’s gets to the fact that if you’ve researched something, you can’t make declarations about something you “feel” exists, but can’t locate. It must have existed. So, I’m familiar with this dilemma. But hopefully that’ll inspire additional works and additional research for a fuller picture.

Roland Allen: I really hope so. I really hope so. And like I say, I’m fairly sure there is the work out there in Turkey that people have been looking at the Ottoman notebooks. I’m pretty sure all that’s there, I just came across it too late to go into the book.

David Newstead: I’m curious… Stepping out of the realm of the historical for a second. Because you’ve seen this progression of notebooks overtime, do you have any predictions about notebooks in the future for comparable periods of time?

Roland Allen: I don’t think they’re going to go away. And I think that there is going to be a bit of a reaction to all these digital devices. We’re seeing that. People fall in love with devices and social media and then they seem to fall out of love with them again. So, I don’t think the notebook is going anywhere. For instance, in education, my own kids have gone through middle and high school in the UK. My daughter, who’s now 21, her schools used their iPads a lot. Every student had an iPad and they built classes around their devices. I was very unhappy with that. It didn’t work for her. She did not learn well with an iPad. She worked much better earlier on in her life with exercise books and things like that.

And my son, interestingly, is younger and he’s now 13 years old. The school is taking away their laptops and they’ve gone back to exercise books and copy books and writing everything by hand. The schools have now realized that these flashy digital devices, which are really expensive and bring all kinds of annoyances with them, aren’t actually as good for learning as writing things down by hand. So, I think that’s a really major step forward. There’s probably been this period for about 10 years when everyone’s been really excited about iPads.

David Newstead: Yeah, I grew up on some of the 1990s Star Trek shows. And it was funny to see that basically the precursor of an iPad was just worked into all those stories as a notebook and as a book and as an everything device. But it seems like a revelation that it’s just not inevitable that we use that especially if there are pros and cons to how it’s used.

Roland Allen: Across the board, I think people are realizing that.

David Newstead: I do some research myself and one thing that’s good to remember is that paper products are available decades later in a way that digital stuff just isn’t or is harder to locate years after the fact. Can you speak to that at all?

Roland Allen: Exactly! Look at the experience Walter Isaacson had when he was writing Steve Jobs’ biography. And they were just trying to get hold of Steve Jobs’ emails from just a few years earlier and it proved impossible for them to track down and get a hold of them. And that’s Steve Jobs! It’s pretty clear that we’re going to pretty much lose a lot of electronic records and communications overtime. Compare and contrast that with Leonardo da Vinci where Walter Isaacson was able to paint a really good picture of what da Vinci thought about based on his 13 or 15 surviving notebooks. It’s interesting as you say that digital stuff does decay overtime and becomes inaccessible.

David Newstead: Here’s another outside-the-box question. Sometimes notebooks feature in movies or TV shows or literature. Do you have any favorite depictions of those in media?

Roland Allen: The story I tell about Bruce Chatwin and his notebooks that has a very strong resonance with me. When I was younger, I guess 30 years ago, I loved Bruce Chatwin. Absolutely one of my favorite writers. Undoubtedly an incredible novelist and travel writer. The Songlines, which I think most people would say was his most important book. His masterwork. It’s really flawed. It’s got a massive central argument, which doesn’t really stand up when you look at it too hard. But the way he sells it to you is so convincing. It’s really quite a bit of work. And in that book, he makes his notebooks one of the central characters in effect. About two-thirds of the way through, he just breaks off and it just goes into a collection of snippets from his notebooks. And then, he goes back to the main narrative at the end. And that really stayed with me. That made a massive impression on me. So, Chatwin and his notebooks I guess are one of the things which must have always been at the back of my mind even before I started working on this. A big, massive caveat is that Bruce Chatwin is a compulsive liar. I mean, he really could not tell the truth more than about five minutes at a stretch. So everything you read that he has written, you have to take with a massive pinch of salt, keeping in mind this might not have happened. The way he talks about his life is just fantastic and inspiring.

David Newstead: Do you have any questions for me? Or is there anything that I didn’t ask about that you would want to touch on or emphasize to prospective readers?

Roland Allen: I’m really glad that you asked about what’s not in the book, because I feel quite badly about the stories of those Arabic notebooks in particular. I made sure that I sort of explained the situation in the book, but it’s good to know there’s a bit of interest there. No, we seemed to have talked about the beginning of the book and the end of it. Hopefully, people can discover some fun stuff in the middle.

David Newstead: Last question. I know you talked about Moleskines in the book, but do you have a favorite kind of notebook?

Roland Allen: I do! Yeah. Moleskines launched I think in 1997 and then they came out in other places in Europe in the late ‘90s. And I remember buying my first Moleskine. I know where I was when I saw it – this hugely expensive, black, sleek, mysterious, kind of monolith object. Very, very stylish. Very cool. And I bought it and like a lot of other people then did not know what to do with it at all. And I sort of half used it. But then I started keeping a diary. And then, I started keeping a diary in Moleskine journals. I really, really liked them. I have four of those. Tiny, tiny writing. Hundreds and hundreds of words on them. And then, the pages weren’t quite big enough, so I went to Leuchtturm journals because the pages are a little bit bigger! And then, I just filled them as well. Then, I needed a different thing. So, I needed to get a page for a day. I found that the best diaries, which were a page for a day with lots of space. There’s a brand of Japanese notebook called the Stalogy notebook and that’s what I use most often. They have amazing paper! Japanese paper is phenomenal. It’s so fine and light and also tough, really smooth. And these Stalogy notebooks are beefy-bound as well so they don’t fall apart, which is a problem I had with Moleskines. They always ended up covered in tape. The Japanese ones are much tougher. Yes, I heartily endorse the A5 368-page Stalogy notebook. Really wonderful product and that’s my favorite.

David Newstead: Nice! Well, I really appreciate your time. I hope book tours, book talks, interviews, and everything keep going well. It’s a great book. And congratulations on getting it over the finish line.

Roland Allen: Thank you very much, David. I really appreciate that. Very nice to talk to you.

November 27, 2024

Michael Winslow’s Typewriter History

November 21, 2024

In Memory

November 15, 2024

Things in Used Books

David Michael Newstead | The Philosophy of Shaving

A partially filled in business calendar from 1997 owned by someone named LarryA printed off map of Azerbaijan inserted into an atlasAn insane amount of notes inscribed in the margins of a book about the artist Pieter ClaeszA floppy disk for the 1987 video game by Sierra entitled Police Question: The Pursuit of the Death AngelA Book of the Month Club pamphlet from 1952 about Frederick Lewis Allen’s The Big Change, inside the book itselfA newspaper map of London from 1931A computerized paper punch card for the Georgetown University Library circa 1970sA large post-it note taped to the interior back cover, drawing out the family tree of the British monarchySomeone’s business card from NASAAn etching of a Roman coinNovember 4, 2024

November 1, 2024

What’s the Matter with Kansas?

David Michael Newstead | The Philosophy of Shaving

There’s a book I hate called What’s the Matter with Kansas? How Conservatives Won the Heart of America. It came out during the Bush administration. Although books about a specific presidency don’t usually age well, I think this one is noteworthy and maybe even important. I hate it, because it’s super pretentious. That doesn’t mean the author is wrong though. At least, he is right about some things, but not always in the way he might have hoped. The book is about American populism. Kansas, the center of the heartland and a stand-in for all red states in the book, has a history of populism going back more than a century to the days of Eugene Debs. Yet, Kansas voters in 2004 and today tend to vote more conservative. How can this be, the author wonders, citing all the contradictions of average Americans supporting the Republican Party: corporate interests with a family values façade. Then, he pieces together the politics and populism that Kansas voters should support. He writes:

American conservatism depends for its continued dominance and even for its very existence on people never making certain mental connections about the world, connections that until recently were treated as obvious or self-evident everywhere on the planet. For example, the connection between mass culture, most of which conservatives hate, and laissez-faire capitalism, which they adore without reservation. Or between the small towns they profess to love and the market forces that are slowly grinding those small towns back into the red-state dust — which forces they praise in the most exalted terms.

Looking back on it now, many of the observations in the book turned out to be a canary in the coal mine, just another indicator foreshadowing the country’s current trajectory. Residents of red states like Kansas did eventually turn against the hypocrisies of that version of the Republican Party the author rails against. After several wars, the Great Recession, the opioid epidemic, and more, support diminished. Or morphed, more accurately. Things changed. But the populism that people drifted towards didn’t turn out to be what idealistic outsiders wanted it to be. We didn’t travel back in time or transform into the mythically perfect populists of a hundred years ago. The country was radically different. Then, culture wars, social media, and endless partisanship unleashed a new phase in American politics, which is ironically just our oldest and worst demons in updated, annoying packaging. And populism, according to any of its wide-ranging definitions, seems especially unconcerned with how people should feel and should think and act and vote. Real people feel and think and act in as many contradictory ways as they want to. Where exactly they leaves us after every election is worth plenty of thought and, at this point, not much condescension.

October 31, 2024

October 25, 2024

Don’t Stop Thinking About Tomorrow

David Michael Newstead | The Philosophy of Shaving

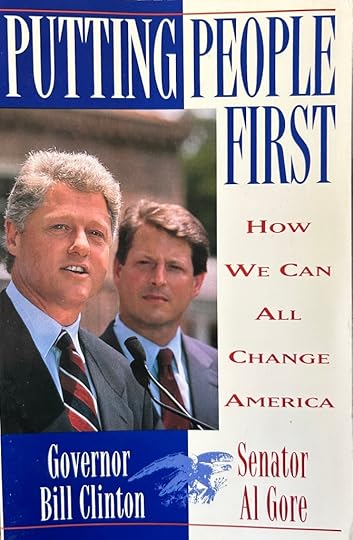

It’s entertaining to look back at predictions and plans for the future. In the 1992 presidential election, Bill Clinton and Al Gore released a book called Putting People First: How We Can All Change America. I flipped through an old copy in a little free library and among all their bold campaign promises from back then was this one:

Create a national information network to link every home, business, lab, classroom, and library by the year 2015.

Well, good news. We did it! 2015 seems comically distant from 1992 in almost every way. Luckily, the internet arrived ahead of schedule and probably a little different than people would have expected. Still, it’s a piece of presidential history I think about every now and then, when a better world seemed as simple as connecting everyone.

October 17, 2024

The Book Detective

David Michael Newstead | The Philosophy of Shaving

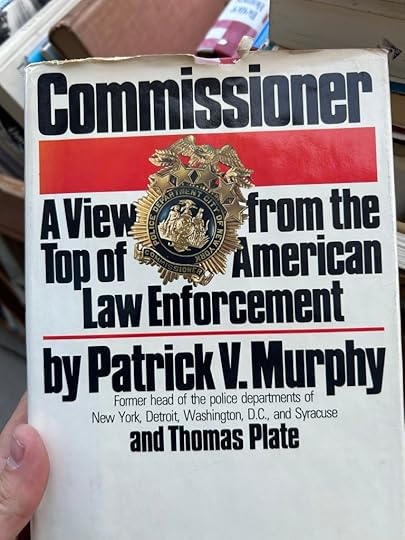

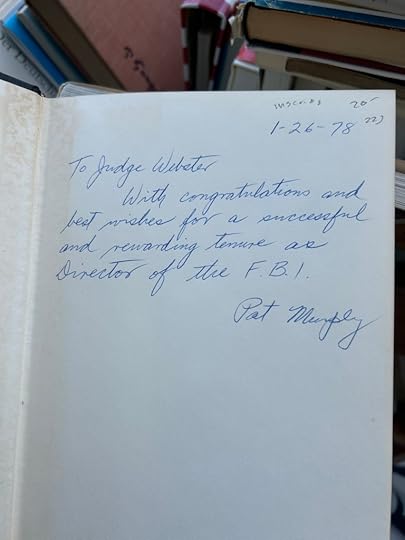

I picked up an old book, because it had an interesting cover – Commissioner: A View from the Top of American Law Enforcement. This 280-page publication recounts the experiences of Patrick V. Murphy who served as the police chief of Syracuse, Detroit, New York City, and Washington DC in the 1960s and ’70s. In this copy, the author wrote a personal inscription on the inside cover. It’s dated January 1978 and addressed to Judge Webster. His inscription reads:

With congratulations and best wishes for a successful and rewarding tenure as Director of the F.B.I.

Who is Judge Webster? At the time, William H. Webster was a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit. As indicated, President Carter appointed him to be the head of the F.B.I. in 1978, a role he held for a decade before being appointed head of the C.I.A. in 1987 by President Reagan. Webster is the only person to have led both agencies. The book didn’t contain any other notes or inscriptions. Patrick V. Murphy died in 2011. William H. Webster turned 100 years old in March 2024.