Matt Rees's Blog, page 33

October 28, 2009

The Real Iraq War: Michael Anthony’s Writing Life

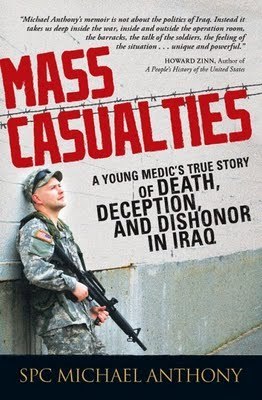

By now it’s no secret that the Iraq War has been a disillusioning experience for many of the U.S. servicemen sent there. The literature on the war has, so far, been mostly written by journalists. There’s plenty of it, and like most journalism it runs pretty mainstream and inoffensive, no matter how bloody the scenes depicted. But Michael Anthony, a veteran of the war, has a different perspective. His new book Mass Casualties: A Young Medic’s True Story of Death, Deception, and Dishonor in Iraq is the best account yet of a war that continues to cost lives and to sully the image of the democracy in whose name it was supposedly fought. It’s a subject I’ve thought about a great deal as I travel my corner of the Middle East and as I continue to encounter fighters – Israeli and Palestinian – who endure personal hardship and tormenting nightmares when they face the realities of war. So read the book. Meantime, here's Michael's Writing Life.

By now it’s no secret that the Iraq War has been a disillusioning experience for many of the U.S. servicemen sent there. The literature on the war has, so far, been mostly written by journalists. There’s plenty of it, and like most journalism it runs pretty mainstream and inoffensive, no matter how bloody the scenes depicted. But Michael Anthony, a veteran of the war, has a different perspective. His new book Mass Casualties: A Young Medic’s True Story of Death, Deception, and Dishonor in Iraq is the best account yet of a war that continues to cost lives and to sully the image of the democracy in whose name it was supposedly fought. It’s a subject I’ve thought about a great deal as I travel my corner of the Middle East and as I continue to encounter fighters – Israeli and Palestinian – who endure personal hardship and tormenting nightmares when they face the realities of war. So read the book. Meantime, here's Michael's Writing Life.How long did it take you to get published?

I started writing the book as soon as I returned home from Iraq. I wrote the first hundred pages in six months and then the last hundred pages in two days (for the first draft). I then spent several months editing and doing rewrites. In total, from starting to write until getting a book deal, it took one year (almost exactly).

Would you recommend any books on writing?

I’m sure there are some out there, but I’ve never read any books on writing. I can give you a few of my favorite books though; the ones that I place as the top tier of writing, and for me, I think reading books, with a great style and prose, can help your writing as well. My top books (not in any order): Atlas Shrugged, Catch 22, Catcher in the Rye, The Perks of Being a Wallflower.

What’s a typical writing day?

I usually spend my typical writing day, finding other things to do than write. I think part of the aspect of being a writer is having the discipline to actually sit down and write. I don’t write every day as most writers do, but when I do write, that’s all I do. For me, it’s not about quantity of time, but quality of time. I could write while doing laundry or watching television, but it wouldn’t be the same. When I do write, it’s all about the writing and nothing else, I throw myself into and sometimes I won’t shower or leave the house for days.

Plug your book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

My latest and first book is: Mass Casualties: A Young Medic’s True Story of Death, Deception, and Dishonor in Iraq. It is the true story of what goes on during war, and what went on over there. It’s not a pro war or anti war book, it’s simply a true war story. I think a lot of stories/movies/shows out there; paint this picture of the American Soldier as this romanticized heroic idea. What I wanted to do with my book was simply paint a picture of the American Soldier as a human. It goes back to the old saying: “I’d rather be hated for what I am, than loved for what I’m not.” If people really want to appreciate and support the troops, the least they can do is learn the real stories, and not just the ones they’re told by reporters or the military officials.

If you look at a majority of war books or movies out there, they all paint this perfect picture of war and its effects. For example, look at one of the long running war movie franchises: Rambo, starring Sylvester Stallone. Rambo goes off to war and comes home with severe post-traumatic stress disorder. Even with this PTSD, he still manages to be a hero, save a town or city from some disaster and at the end, still get the girl. But in reality, if a soldier comes home with severe PTSD, they kill themselves. End of movie, roll the credits.

The problem with romanticizing these soldiers and situations is that when they come home, no one understands what they went through and what it was really like. And because of this, today’s military has the highest suicide rates in thirty years. Since the Afghanistan war started, more active duty soldiers have killed themselves than have been injured or killed in Afghanistan—combined. This is why I think we need to give people the full picture of war, and not just the good stuff they want to know about.

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

My current, favorite, contemporary writer is: Stephen Chbosky, author of: The Perks of Being a Wallflower. For me, I just loved everything about that book, from the idea of it, to the way it was written.

How much research was involved in your book?

The vast majority of my book was based on my journals in Iraq, and because of this, the research involved was minimal. All I had to do was convert my illegible sometimes chaotic journal entries, into readable prose.

What’s the best idea for marketing a book you can do yourself?

Tell everyone you know, or have ever known, and then tell them to tell everyone they know. I now think everyone in my high-school class knows I have a book in bookstores. Social Media is a great thing, and don’t be afraid to go out there and use it. Also, I think getting other authors to review and/or comment on your work. I was able to get over thirty well accomplished people to review, comment on, and endorse my work; from famous politicians, to famous historians, psychologists, veterans and authors.

How many books did you write before you were published?

When I was sixteen I had written three books and two movies; it then took me five years to realize I wanted to be a writer.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

When I was younger, I once wrote a book from the perspective of a T-shirt. The book had a T-shirt as a main character and I followed him around and wrote about what he was thinking as the wearer of the shirt went around and did his daily duties.

October 27, 2009

That's my boy

I started to feel recently that my bio on www.mattbeynonrees.com was a bit over-serious. First of all, it was in the third person. I honestly never refer to myself in the third person (except when I'm shopping and I ask my wife "Would Matt Beynon Rees wear a shirt in this shade of pink?") Then I saw that the bio took my writing and -- worse still -- me, rather seriously. I prefer to make it clear that I can laugh at myself. So I changed the whole bio, adding some tidbits of my past which wouldn't make it onto a bio of the "He is the recipient of a Peepgass Fellowship for the Arts and divides his time between Bal Harbor and East 74th Street" type. Here's how it turned out:

Matt Beynon Rees

WHERE: I live in Jerusalem. I came here in 1996. For love. Then we divorced. But the place took hold. Not for the violence and the excitement that sometimes surrounds it, but because I saw people in extreme situations. Through the emotions they experienced, I came to understand myself.

BEFORE THE WRITING: There was never really a time before I wrote. I’ve been at it since I was seven (a poem about a tree, on the classroom wall with a gold star beside it.) But I arrived in the Middle East as a journalist with only a couple of published short stories to my name. First I wrote for The Scotsman, then Newsweek, and from 2000 until 2006 as Time Magazine’s Jerusalem bureau chief. I won some awards for covering the intifada. Yasser Arafat once tried to have me arrested, but I eluded him and decided to focus on fiction. I’d learned so much about the Palestinians – and about life – that didn’t fit into the limited world of journalism. So I wrote my Palestinian crime novels.

BEFORE JERUSALEM: I was born in Newport, Wales, in 1967. That’s my mother’s hometown; my father’s from Maesteg in the Llynfi valley. We moved around, to Cardiff and Croydon, then I studied English at Wadham College, Oxford University with Terry Eagleton as my tutor. Contemporaries may remember me as the fellow with bleached blonde hair at the bar of the King’s Arms in the company of the Irish porters from All Souls College. I did an MA at the University of Maryland and lived in New York for five years before I hit the Middle East.

WHERE THE BOOKS CAME FROM: I wrote a nonfiction account of Israeli and Palestinian society called Cain's Field: Faith, Fratricide, and Fear in the Middle East in 2004 (Free Press). I’m proud of it, because it really gets to the heart of the conflict here – it isn’t one of those notebook-dump foreign correspondent books.

I was looking for my next project and came up with the idea for Omar Yussef, my Palestinian sleuth, while chatting with my wife in our favorite hotel, the Ponte Sisto in the Campo de’Fiori in Rome. I realized I had become friends with many colorful Palestinians who’d given me insights into the dark side of their society. Like the former Mister Palestine (he dead-lifts 900 pounds), a one-time bodyguard to Yasser Arafat (skilled in torture), and a delightful fellow who was a hitman for Arafat during the 1980s. To tell the true-life stories I’d amassed over a decade, I decided to channel the reporting into a crime series. After all, Palestine’s reality is no romance novel.

THE NOVELS: The first novel, The Collaborator of Bethlehem (UK title The Bethlehem Murders), was published in February 2007 by Soho Press. In the UK it won the prestigious Crime Writers Association John Creasey Dagger in 2008, and was nominated in the US for the Barry First Novel Award, the Macavity First Mystery Award, and the Quill Best Mystery Award. In France it’s been shortlisted for the Prix des Lecteurs. New York Times reviewer Marilyn Stasio called it “an astonishing first novel.” It was named one of the Top 10 Mysteries of the Year by Booklist and, in the UK Sir David Hare made it his Book of the Year in The Guardian.

Colin Dexter, author of the Inspector Morse novels, called Omar Yussef “a splendid creation.” Omar was called “Philip Marlowe fed on hummus” by one reviewer and “Yasser Arafat meets Miss Marple” by another.

The second book in the series, A Grave in Gaza, appeared in February 2008 (and at the same time under the title The Saladin Murders in the UK). The Bookseller calls it “a cracking, atmospheric read.” I put in elements of the plot relating to British military cemeteries in Gaza in homage to my two great uncles, who rode through there with the Imperial Camel Corps in 1917. One of them, Uncle Dai Beynon, was still around when I was a boy, and I was named after him.

The third book in the series, The Samaritan’s Secret, was published in February 2009. The New York Times said it was “provocative” and it had great reviews in places I’d not have expected – The Sowetan, the newspaper of that S. African township, for example.

AROUND THE WORLD: My Omar Yussef Mystery series has been sold to leading publishers in 22 countries: the U.S., France, Italy, Britain, Poland, Spain, Germany, Holland, Israel, Portugal, Brazil, Norway, Denmark, the Czech Republic, Romania, Sweden, Iceland, Chile, Venezuela, Japan, Indonesia and Greece.

OMAR’S NEXT TRAVELS: THE FOURTH ASSASSIN, the fourth novel in my series, will be published in February 2010. In it, Omar visits the famous Palestinian town of Brooklyn, New York (there really is a growing community there in Bay Ridge), and finds a dead body in his son’s bed…

REACH ME AT: matt@mattbeynonrees.com.

Matt Beynon Rees

WHERE: I live in Jerusalem. I came here in 1996. For love. Then we divorced. But the place took hold. Not for the violence and the excitement that sometimes surrounds it, but because I saw people in extreme situations. Through the emotions they experienced, I came to understand myself.

BEFORE THE WRITING: There was never really a time before I wrote. I’ve been at it since I was seven (a poem about a tree, on the classroom wall with a gold star beside it.) But I arrived in the Middle East as a journalist with only a couple of published short stories to my name. First I wrote for The Scotsman, then Newsweek, and from 2000 until 2006 as Time Magazine’s Jerusalem bureau chief. I won some awards for covering the intifada. Yasser Arafat once tried to have me arrested, but I eluded him and decided to focus on fiction. I’d learned so much about the Palestinians – and about life – that didn’t fit into the limited world of journalism. So I wrote my Palestinian crime novels.

BEFORE JERUSALEM: I was born in Newport, Wales, in 1967. That’s my mother’s hometown; my father’s from Maesteg in the Llynfi valley. We moved around, to Cardiff and Croydon, then I studied English at Wadham College, Oxford University with Terry Eagleton as my tutor. Contemporaries may remember me as the fellow with bleached blonde hair at the bar of the King’s Arms in the company of the Irish porters from All Souls College. I did an MA at the University of Maryland and lived in New York for five years before I hit the Middle East.

WHERE THE BOOKS CAME FROM: I wrote a nonfiction account of Israeli and Palestinian society called Cain's Field: Faith, Fratricide, and Fear in the Middle East in 2004 (Free Press). I’m proud of it, because it really gets to the heart of the conflict here – it isn’t one of those notebook-dump foreign correspondent books.

I was looking for my next project and came up with the idea for Omar Yussef, my Palestinian sleuth, while chatting with my wife in our favorite hotel, the Ponte Sisto in the Campo de’Fiori in Rome. I realized I had become friends with many colorful Palestinians who’d given me insights into the dark side of their society. Like the former Mister Palestine (he dead-lifts 900 pounds), a one-time bodyguard to Yasser Arafat (skilled in torture), and a delightful fellow who was a hitman for Arafat during the 1980s. To tell the true-life stories I’d amassed over a decade, I decided to channel the reporting into a crime series. After all, Palestine’s reality is no romance novel.

THE NOVELS: The first novel, The Collaborator of Bethlehem (UK title The Bethlehem Murders), was published in February 2007 by Soho Press. In the UK it won the prestigious Crime Writers Association John Creasey Dagger in 2008, and was nominated in the US for the Barry First Novel Award, the Macavity First Mystery Award, and the Quill Best Mystery Award. In France it’s been shortlisted for the Prix des Lecteurs. New York Times reviewer Marilyn Stasio called it “an astonishing first novel.” It was named one of the Top 10 Mysteries of the Year by Booklist and, in the UK Sir David Hare made it his Book of the Year in The Guardian.

Colin Dexter, author of the Inspector Morse novels, called Omar Yussef “a splendid creation.” Omar was called “Philip Marlowe fed on hummus” by one reviewer and “Yasser Arafat meets Miss Marple” by another.

The second book in the series, A Grave in Gaza, appeared in February 2008 (and at the same time under the title The Saladin Murders in the UK). The Bookseller calls it “a cracking, atmospheric read.” I put in elements of the plot relating to British military cemeteries in Gaza in homage to my two great uncles, who rode through there with the Imperial Camel Corps in 1917. One of them, Uncle Dai Beynon, was still around when I was a boy, and I was named after him.

The third book in the series, The Samaritan’s Secret, was published in February 2009. The New York Times said it was “provocative” and it had great reviews in places I’d not have expected – The Sowetan, the newspaper of that S. African township, for example.

AROUND THE WORLD: My Omar Yussef Mystery series has been sold to leading publishers in 22 countries: the U.S., France, Italy, Britain, Poland, Spain, Germany, Holland, Israel, Portugal, Brazil, Norway, Denmark, the Czech Republic, Romania, Sweden, Iceland, Chile, Venezuela, Japan, Indonesia and Greece.

OMAR’S NEXT TRAVELS: THE FOURTH ASSASSIN, the fourth novel in my series, will be published in February 2010. In it, Omar visits the famous Palestinian town of Brooklyn, New York (there really is a growing community there in Bay Ridge), and finds a dead body in his son’s bed…

REACH ME AT: matt@mattbeynonrees.com.

October 23, 2009

All rise for the Palestinian anthem

A parody of a nationalistic Palestinian song ridicules the intractable dispute between Hamas and Fatah leaders. By Matt Beynon Rees - GlobalPost

RAMALLAH, West Bank — Last week, Hamas and Fatah were on the verge of an agreement to end more than two years of civil strife. Then Hamas tore it up, and both sides went back to tearing apart Palestinian politics.

The two main political factions, which respectively rule the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, have tortured and even killed each other’s members. Their dispute has also held up peace talks with Israel. That, you might think is nothing to sing about.

Unless you’re preparing a YouTube parody of a nationalistic Palestinian anthem with the intention of skewering leaders of the two sides as undemocratic schemers.

The parody, which was aired this week on the Arab satellite news channel Al Jazeera, bridged the otherwise intractable differences between Hamas and Fatah, uniting them in upright self-righteousness.

The clip takes the 75-year-old song “Mawteni” (My Homeland) and reworks some of the lines.

The first verse ought to go like this:

“My homeland, My homeland

Glory and beauty, Sublimity and splendor

Are in your hills, Are in your hills

Life and deliverance, Pleasure and hope

Are in your air, Are in your Air

Will I see you? Will I see you?”

Nothing there beyond the idealized boosterism of the average national anthem, as heard all over the world.

But here’s the Youtube/Al Jazeera version:

“My homeland, My homeland

Curse and perversity, Plague and hypocrisy

Are in your hills, Are in your hills

Tyrants and oppressors, Cunning not fidelity

Are in your sanctuary, Are in your sanctuary”

Against a backdrop of images of Fatah and Hamas leaders, the spoof goes on to state that political chiefs “want/to live like slaves/which is certain shame for us.”

The clip, which has been posted in two versions on YouTube, has been viewed by more than 120,000 people online in the last month. Al Jazeera aired it in the middle of a talk show debate between a Fatah leader and a Hamas official.

Both men responded with shock.

Nasser al-Qudwa, a senior Fatah official and Yasser Arafat’s nephew, told the Al Jazeera presenter that broadcasting the song was “an unprecedented regression.”

A Palestinian student journalist in Nablus on Tuesday announced his intention to sue Al Jazeera for broadcasting the clip, which he characterized as a slur on Palestinian nationhood. Ghaith Ghazi, who works at the An-Najjah University radio station, told a Palestinian news site that the anthem has a “psychological and emotional impact on the Arab peoples, especially the Palestinians.”

Perhaps Ghazi is particularly sensitive about “Mawteni,” because its lyrics were written in 1934 by another Nablus resident, Ibrahim Touqan. A Lebanese composer added the music and for many years it was seen as the anthem of the Palestinians.

It was taken up by other Arab countries too and was for a time the anthem of Iraq after the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime. It’s also an official anthem in Syria and Algeria, which use it to show solidarity with the Palestinians.

It’s not to be confused with the official Palestinian national anthem “Biladi” (My Country).

"Biladi" was made the anthem in 1996, when it was adopted by the Palestinian National Council, the Palestine Liberation Organization’s main legislative body.

Here’s the first verse of "Biladi":

"With my determination, my fire and the volcano of my revenge

With the longing in my blood for my land and my home

I have climbed the mountains and fought the wars

I have conquered the impossible, and crossed the frontiers"

The current Palestinian leadership doesn’t exactly measure up to those lyrics, either. Watch out for a cruel internet spoof to the tune of “Biladi,” no doubt.

Meanwhile, Hamas rejected a deal brokered by Egypt to end the long civil conflict with Fatah, though Fatah had signed on to the agreement last week.

Officials from both sides said they expected soon to be called to Cairo for further negotiations. No doubt, they’ll both continue singing the same song.

RAMALLAH, West Bank — Last week, Hamas and Fatah were on the verge of an agreement to end more than two years of civil strife. Then Hamas tore it up, and both sides went back to tearing apart Palestinian politics.

The two main political factions, which respectively rule the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, have tortured and even killed each other’s members. Their dispute has also held up peace talks with Israel. That, you might think is nothing to sing about.

Unless you’re preparing a YouTube parody of a nationalistic Palestinian anthem with the intention of skewering leaders of the two sides as undemocratic schemers.

The parody, which was aired this week on the Arab satellite news channel Al Jazeera, bridged the otherwise intractable differences between Hamas and Fatah, uniting them in upright self-righteousness.

The clip takes the 75-year-old song “Mawteni” (My Homeland) and reworks some of the lines.

The first verse ought to go like this:

“My homeland, My homeland

Glory and beauty, Sublimity and splendor

Are in your hills, Are in your hills

Life and deliverance, Pleasure and hope

Are in your air, Are in your Air

Will I see you? Will I see you?”

Nothing there beyond the idealized boosterism of the average national anthem, as heard all over the world.

But here’s the Youtube/Al Jazeera version:

“My homeland, My homeland

Curse and perversity, Plague and hypocrisy

Are in your hills, Are in your hills

Tyrants and oppressors, Cunning not fidelity

Are in your sanctuary, Are in your sanctuary”

Against a backdrop of images of Fatah and Hamas leaders, the spoof goes on to state that political chiefs “want/to live like slaves/which is certain shame for us.”

The clip, which has been posted in two versions on YouTube, has been viewed by more than 120,000 people online in the last month. Al Jazeera aired it in the middle of a talk show debate between a Fatah leader and a Hamas official.

Both men responded with shock.

Nasser al-Qudwa, a senior Fatah official and Yasser Arafat’s nephew, told the Al Jazeera presenter that broadcasting the song was “an unprecedented regression.”

A Palestinian student journalist in Nablus on Tuesday announced his intention to sue Al Jazeera for broadcasting the clip, which he characterized as a slur on Palestinian nationhood. Ghaith Ghazi, who works at the An-Najjah University radio station, told a Palestinian news site that the anthem has a “psychological and emotional impact on the Arab peoples, especially the Palestinians.”

Perhaps Ghazi is particularly sensitive about “Mawteni,” because its lyrics were written in 1934 by another Nablus resident, Ibrahim Touqan. A Lebanese composer added the music and for many years it was seen as the anthem of the Palestinians.

It was taken up by other Arab countries too and was for a time the anthem of Iraq after the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime. It’s also an official anthem in Syria and Algeria, which use it to show solidarity with the Palestinians.

It’s not to be confused with the official Palestinian national anthem “Biladi” (My Country).

"Biladi" was made the anthem in 1996, when it was adopted by the Palestinian National Council, the Palestine Liberation Organization’s main legislative body.

Here’s the first verse of "Biladi":

"With my determination, my fire and the volcano of my revenge

With the longing in my blood for my land and my home

I have climbed the mountains and fought the wars

I have conquered the impossible, and crossed the frontiers"

The current Palestinian leadership doesn’t exactly measure up to those lyrics, either. Watch out for a cruel internet spoof to the tune of “Biladi,” no doubt.

Meanwhile, Hamas rejected a deal brokered by Egypt to end the long civil conflict with Fatah, though Fatah had signed on to the agreement last week.

Officials from both sides said they expected soon to be called to Cairo for further negotiations. No doubt, they’ll both continue singing the same song.

October 21, 2009

“ME” doesn’t stand for Middle East

One of the advantages of being an author in an “exotic” locale is that people visit and want to hear from you as someone who knows the place well. It’s also one of the disadvantages.

Last Friday night, I drove out to Ein Kerem to meet one such group of visitors from Reboot, a U.S. organization that brings together mostly liberal – and certainly not conventional-thinking – Jews to discuss issues related to Judaism and Israel. It turned out to be one of those occasions where I take a certain amount of pleasure in the people I meet, but am also reminded why I chose to spend my days alone with imaginary characters.

Ein Kerem is an old village on the edge of Jerusalem that’s less regimented in its architecture and layout than the neighborhoods of the city built in the last 60 years. John the Baptist was born there. So was my son, because there’s now a hospital overlooking the valley with its collection of churches, convents and restaurants. When I arrived, I stood by my car for a few minutes watching a desert fox prowl the street, its brush silhouetted against the lights of the hospital.

The Reboot people had spent the day being spat upon by ultra-Orthodox Jews who objected to their visit to a religious neighborhood of Jerusalem. The previous day a friend of mine who works with asylum seekers had shown them around a Tel Aviv slum where illegal immigrants from Africa and the Far East congregate.

In the private house where Reboot had arranged for the dinner, I went out to the garden with the 15 members of the group. The owner of the house started telling them about the village. She began with the fact that it had been home to Palestinian Arabs. She didn’t mention that in 1948 a massacre in a nearby village lead them to flee. One of the “Rebooters” called her on it: “What happened to the Arabs?”

Nothing wrong with that, except that it wasn’t really a question – he could’ve guessed the answer. There was a tone of self-righteous confrontation to which I’m deeply attuned after 13 years here.

Well, not as deeply attuned as I thought. Because then I made my mistake.

I’d been asked to speak about “Jerusalem and what it means to the Jews.” God knows why. But I never turn down an audience when there’s a chance of plugging my books. My mistake was to say that I’d be prepared to talk about broader political issues than Jerusalem.

I can do that perfectly well. For several hours in fact I discussed the changes – for the worse – in the chances for peace over the years. The growth of Israeli settlements, in the face of agreements to which Israel is a signatory. The sense among senior Palestinian politicians that they can let peace talks languish because time is somehow on their side. Everyone behaving as though the problems they’re prolonging will disappear.

But people don’t know the energy it costs me to discuss this shit. And after 13 years here that’s what it is. Shit.

As the evening drew on, I found myself subject to a familiar feeling. Sapped of energy, tightness at the back of my jaw, wanting to fall off my chair. I’d connected with a few members of the group. But still others wanted answers to questions which have no answer (unless you think, for example, that the world just hates Jews and wants Israel gone, or that Muslims are born crazy.) I suppose I ought to have said that politicians disgust me and let’s quit talking politics… Let’s talk about how you build a sentence. What it’s like to bury yourself in a novel for months at a time. How different a culture looks when you put aside politics and try to imagine the taste of hummus on a tongue that recalls a time when your mother fed it to you as a baby.

It’s not for nothing that the people closest to me at the table were the ones with which I connected and the ones at the farthest end asked questions on an impersonal political level. At the far end of the table I probably seemed like a lecturer, rather than the actual human being visible to those sitting close to me.

I wrote my novels to escape this sort of dialogue. I wanted to show the human concerns of the Palestinians I’d come to know, rather than the stereotypes of their political portrayal.

Why? Because politics in the Middle East goes around in circles. Circles of victimization, everyone competing to show that they’re misunderstood and that they suffer more than the other side of the conflict. Refusing to see the other side as human.

The longer I’m here the less interested I am in exploring that. Palestinians are people to me – not symbols of victimization and oppression. Israelis, too. To a novelist, people can be characters. To a politician, they’re only ever symbols and numbers to be shunted about or used.

When I talked to the Rebooters, I was able to explain this, but only when the conversation turned to my books. It’s fair enough that most of them hadn’t yet read my books and that they returned to political issues and media coverage of the conflict.

As I drove home through the empty streets of a quiet Jerusalem already six hours into the Jewish Sabbath, I realized that I turned to novels because I’d come to know myself well. I didn’t want to turn my attention outward as a journalist, to record the emotional responses of others. I wanted to take readers into my characters’ heads – and, of course, into mine. Into the extreme experiences and emotions I’d gone through covering the intifada, learning about the real Palestinian culture. I decided that I would no longer speak about political issues, except where they touched upon the content of my Palestinian crime novels.

From now on, the Middle East is me.

(I posted this on the International Crime Authors Reality Check blog.)

Last Friday night, I drove out to Ein Kerem to meet one such group of visitors from Reboot, a U.S. organization that brings together mostly liberal – and certainly not conventional-thinking – Jews to discuss issues related to Judaism and Israel. It turned out to be one of those occasions where I take a certain amount of pleasure in the people I meet, but am also reminded why I chose to spend my days alone with imaginary characters.

Ein Kerem is an old village on the edge of Jerusalem that’s less regimented in its architecture and layout than the neighborhoods of the city built in the last 60 years. John the Baptist was born there. So was my son, because there’s now a hospital overlooking the valley with its collection of churches, convents and restaurants. When I arrived, I stood by my car for a few minutes watching a desert fox prowl the street, its brush silhouetted against the lights of the hospital.

The Reboot people had spent the day being spat upon by ultra-Orthodox Jews who objected to their visit to a religious neighborhood of Jerusalem. The previous day a friend of mine who works with asylum seekers had shown them around a Tel Aviv slum where illegal immigrants from Africa and the Far East congregate.

In the private house where Reboot had arranged for the dinner, I went out to the garden with the 15 members of the group. The owner of the house started telling them about the village. She began with the fact that it had been home to Palestinian Arabs. She didn’t mention that in 1948 a massacre in a nearby village lead them to flee. One of the “Rebooters” called her on it: “What happened to the Arabs?”

Nothing wrong with that, except that it wasn’t really a question – he could’ve guessed the answer. There was a tone of self-righteous confrontation to which I’m deeply attuned after 13 years here.

Well, not as deeply attuned as I thought. Because then I made my mistake.

I’d been asked to speak about “Jerusalem and what it means to the Jews.” God knows why. But I never turn down an audience when there’s a chance of plugging my books. My mistake was to say that I’d be prepared to talk about broader political issues than Jerusalem.

I can do that perfectly well. For several hours in fact I discussed the changes – for the worse – in the chances for peace over the years. The growth of Israeli settlements, in the face of agreements to which Israel is a signatory. The sense among senior Palestinian politicians that they can let peace talks languish because time is somehow on their side. Everyone behaving as though the problems they’re prolonging will disappear.

But people don’t know the energy it costs me to discuss this shit. And after 13 years here that’s what it is. Shit.

As the evening drew on, I found myself subject to a familiar feeling. Sapped of energy, tightness at the back of my jaw, wanting to fall off my chair. I’d connected with a few members of the group. But still others wanted answers to questions which have no answer (unless you think, for example, that the world just hates Jews and wants Israel gone, or that Muslims are born crazy.) I suppose I ought to have said that politicians disgust me and let’s quit talking politics… Let’s talk about how you build a sentence. What it’s like to bury yourself in a novel for months at a time. How different a culture looks when you put aside politics and try to imagine the taste of hummus on a tongue that recalls a time when your mother fed it to you as a baby.

It’s not for nothing that the people closest to me at the table were the ones with which I connected and the ones at the farthest end asked questions on an impersonal political level. At the far end of the table I probably seemed like a lecturer, rather than the actual human being visible to those sitting close to me.

I wrote my novels to escape this sort of dialogue. I wanted to show the human concerns of the Palestinians I’d come to know, rather than the stereotypes of their political portrayal.

Why? Because politics in the Middle East goes around in circles. Circles of victimization, everyone competing to show that they’re misunderstood and that they suffer more than the other side of the conflict. Refusing to see the other side as human.

The longer I’m here the less interested I am in exploring that. Palestinians are people to me – not symbols of victimization and oppression. Israelis, too. To a novelist, people can be characters. To a politician, they’re only ever symbols and numbers to be shunted about or used.

When I talked to the Rebooters, I was able to explain this, but only when the conversation turned to my books. It’s fair enough that most of them hadn’t yet read my books and that they returned to political issues and media coverage of the conflict.

As I drove home through the empty streets of a quiet Jerusalem already six hours into the Jewish Sabbath, I realized that I turned to novels because I’d come to know myself well. I didn’t want to turn my attention outward as a journalist, to record the emotional responses of others. I wanted to take readers into my characters’ heads – and, of course, into mine. Into the extreme experiences and emotions I’d gone through covering the intifada, learning about the real Palestinian culture. I decided that I would no longer speak about political issues, except where they touched upon the content of my Palestinian crime novels.

From now on, the Middle East is me.

(I posted this on the International Crime Authors Reality Check blog.)

Published on October 21, 2009 23:48

•

Tags:

appearances, check, crime, east, fiction, international, israel, jerusalem, jews, journalism, middle, omar, palestinians, reality, religion, writers, yussef

October 16, 2009

Affable and trim

The last couple of articles about me and my books focus on the fact that I'm rather happy. In this month's Hadassah Magazine, I'm "affable and trim." High school friends reading this on Facebook may wonder where the affability was back then...

Profile: Hadassah Magazine October 2009 Matt Beynon Rees By Leora Eren Frucht

Only gritty, dark crime fiction could evoke the corruption—and hope—in Palestinian society, believes one former foreign correspondent, now a best-selling mystery writer.

The morning sun streams through the windows that frame the Mount of Olives to the east and the hills of Bethlehem to the south. Photographs of a smiling mother and baby flash, one after the other, on a computer screen. The only sign of anything sinister in this cheerful room is the stainless-steel dagger lying in its open, velvet-trimmed case on the desk.

It is here, in this modest fifth-floor apartment in the southern Jerusalem neighborhood of San Simon, that plans for diabolical schemes of extortion, brutal torture and gruesome murders have been concocted.

With a swift motion, a tall, fair-skinned man grabs hold of the dagger. His piercing pale blue eyes sparkle with anticipation as he turns the shiny weapon slowly in his hands.

“It really is amazing,” he says with a satisfied grin, then adds, in a faint Welsh accent, “I never imagined that it would all go so well.”

Meet Matt Beynon Rees, winner of the The Crime Writers’ Association John Creasey New Blood Dagger and creator of Omar Yussef, literature’s first (and only) Palestinian detective.

Rees, a Welsh-born journalist, won the prestigious British award—an actual dagger, granted to a first-time crime novelist—for his 2007 The Collaborator of Bethlehem (Mariner), in which Yussef makes his debut.

Since then, the affable and trim Rees has cast the stocky, ex-alcoholic Yussef as the star of two more detective novels set in Gaza and Nablus respectively (A Grave in Gaza, Mariner; and The Samaritan’s Secret, Soho Press), with another—The Fourth Assassin—due out in February. The books have been published in 22 countries, earning lavish praise from critics; French daily L’Express dubbed Rees “The Dashiell Hammett of Palestine.”

The novels are more than just well-crafted whodunits. Rees uses Yussef to shine a light on Palestinian society, exposing the traditions, tensions and ties that determine how people act. The reader is led through the squalid refugee camps of Gaza, opulent palaces of corrupt Palestinian power brokers and the alleyways of Nablus’s casbah, which fill with the aroma of knafeh pastry and cardamom by day and empty out at night, when only gunmen prowl its premises. Rees paints a raw, revealing and, at times, alarming portrait of Palestinian society.

“We all think we know Palestinians, whichever stereotype we choose to ascribe to them—victims or terrorists. I want to show that we don’t know them at all,” says Rees, 42. He is sipping an espresso in the study of the apartment he shares with his American-born wife, Devorah Blachor (currently working on her first mystery novel), and their 2-year-old son, Cai (the name means “rejoice” in Welsh).

Rees grew up in a nonreligious Protestant home in Cardiff, South Wales, and says he never imagined he would end up in Jerusalem, let alone become an award-winning mystery writer and documenter of Palestinian reality. The only connection he had to the region are two great-uncles, both coal miners, who fought in General Edmund Allenby’s Imperial Camel Corps, which arrived in Jerusalem in 1917. “Both were injured,” he says. “One had his finger bitten off by a Turk. The other, whom I recall from my childhood, used to get drunk on Christmas, drop his pants and show us the scar where he got shot, in Betunia, which was near Ramallah. You could say my fascination with the region began there,” quips Rees. He pays homage to them in his second book, in which a British war cemetery in Gaza features prominently.

Like his camel-cavorting ancestors, Rees landed in Israel by chance. After studying English language and literature at Oxford, he completed a degree in journalism at the University of Maryland and covered Wall Street for five years, a period he recalls with little enthusiasm. When his American fiancée got posted as a foreign correspondent in Jerusalem, Rees joined her. The two married and subsequently divorced, with Rees remarrying a few years later. But his path was set. He, too, began working as a Jerusalem-based foreign correspondent, first for The Scotsman, then for Newsweek; in 2000, he became Middle East bureau chief for Time magazine.

If Wall Street had dulled his senses, covering the Palestinian beat heightened them: “I felt so alive, everything was so exotic to me—the sights, the sounds. I love the dirt and the dust and the way people speak to each other.”

Rees soon realized that much of what intrigued him about Palestinian society was beyond the scope of traditional journalism. But, he says, “If it didn’t mention the peace process, it wasn’t of interest to my editors.

“Most journalists are really political scientists: They want to write about the peace process and interview the prime minister,” he continues. “I don’t really care about that. I’ve always felt more like an anthropologist. I’m more interested in how people live their lives, what they eat, how their culture shapes them.” To that end, Rees learned basic Hebrew and Arabic.

“Matt has an old-fashioned reporter’s empathy that enables readers to know what his subjects are thinking—without the sheen of postmodern cynicism that characterizes so many foreign correspondents,” says Matthew Kalman, a Jerusalem-based freelance foreign correspondent who has worked with Rees. “[He:] realized early on that reporting the Palestinian-Israeli conflict is extremely superficial…. Most of the foreign media is only interested in a cowboys and Indians story.”

In 2004, Rees published a highly acclaimed nonfiction account of Israeli and Palestinian society entitled Cain’s Field: Faith, Fratricide, and Fear in the Middle East (Free Press), but felt that his effort was not adequate. “I think people want to read about the Middle East, but not in a starchy, nonfiction tone,” he notes.

Rees decided to try his hand at a novel. The Collaborator of Bethlehem was inspired by a specific incident: the cold-blooded killing of one Palestinian by another, a militia man, who accused his victim of collaborating with Israel—knowing full well that the man was innocent.

“The dirtiness of the story made me think it’s so complex that only in a novel can you get those shades of gray, in terms of people’s motivations,” says Rees, who had been dabbling in fiction since childhood. “And it had to be a crime novel because it’s a real gangster reality—not a place for a romance novel.” So, in 2006, after selling the rights to the book, Rees quit Time to write fiction full-time.

Fiction, that is, to a point. The mystery series is based, in part, on actual events and people, including Yussef, a 56-year-old history teacher at a United Nations-administered girls’ school in the Dehaisha refugee camp south of Bethlehem. The pudgy, often breathless grandfather (whose favorite granddaughter builds him a Web site for The Palestine Agency for Detection) is no suave sleuth, but a kind of accidental hero. Driven by a deep sense of integrity, he seeks the truth and tries to fight growing corruption and violence in the West Bank and Gaza Strip—often at considerable personal risk.

“Yussef is based on a friend who lives in Dehaisha refugee camp whom I have known for over 10 years,” says Rees. “He is very much like the character in the book—quite acerbic and very intelligent. He gets very frustrated seeing how corruption and criminality are destroying a society that he loves very much.”

Are there many Omar Yussefs in Palestinian society?

“There are many who have the same basic discontents about the corruption and violence,” he says, “but there are not that many who take action because most feel trapped.” In a telling example of this, in one novel, a man who protests the use of his rooftop to shoot at Israelis meets an untimely fate. “But there are Palestinians who are trying to change things in very small ways,” Rees continues, adding a note of optimism: “I made Omar a teacher because he represents the possibility that the next generation will be different.”

Jamil Hamad, Time’s veteran Palestinian correspondent, says that several Palestinians have shared with him their respect for Rees’s depiction of their society. “I have received calls from other Palestinians here,” Hamad says, “and from Arabs in Jordan, Syria, Egypt and North Africa who say they are very grateful to him for painting a realistic portrait of Palestinians and are proud of the books.”

Yussef’s adversaries—ruthless heads of militias and security forces, weapons smugglers and crooked politicians—make for a colorful cast of bad guys based on real people whom Rees got to know while researching his novels and during his journalistic days. Military Intelligence Chief General Husseini, a character in A Grave in Gaza, is renowned for his particular method of torture: slicing off the tips of prisoners’ fingers. The person and method are real, though the name given to the style of torture—a Husseini manicure—is Rees’s invention.

In researching the novels, Rees spent entire days and nights hanging out with gunmen, most of whom have since been killed—either by Israeli forces or by other Palestinians. Nearly all of them lived with the knowledge that a violent death was imminent.

“It is almost as though they are ghosts when they are alive,” he says. “It feels eerie to have met someone who was as good as dead anyway.”

And because his sinister types are based on portraits of real individuals, he believes that he is able to present complex, nuanced antagonists, rather than cartoon “bad guys.”

“I feel like if you’re a writer and you can ‘know the minds of many men,’ you can tell their story as though it was emerging from your own emotions,” explains Rees, quoting The Odyssey.

“When I was in a refugee camp in the middle of the night, talking to people from Hamas and Fatah who expected to die at any moment, I think I got some insight into the minds of many men,” concludes Rees, whose neutral foreign looks and identity helped him gain access to his subjects and win their trust.

“I think through these novels he is reporting the conflict in a different and exceptional way,” says Hamad. “He’s not just writing a novel—he’s reporting the story. Matt is one of the few journalists I work with who is always capable of ‘digesting’ it properly, meaning he has no illusions.”

Rees’s literary heroes are the classic detective writers Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. “I love the gritty realism, but I also love the way in which Chandler writes,” he says. “I think he is the greatest stylist of American literature.”

That gritty realism is a hallmark of the Omar Yussef series, which is littered with corpses but also boasts more subtle touches like a swarm of flies that follows the protagonist throughout his sojourn through the filth—both material and moral—of Gaza.

Rees’s own life is a sharp contrast from that of his characters. Every morning, he does a few yoga stretches and writes standing up for several hours at his raised computer terminal. He swims, works out, does Pilates and meditation. He also plays bass in a local band and delights in his toddler son. “I feel younger all the time,” he says happily. He is currently learning piano as part of the research for his new historical novel that evolves around the musical scene in 19th-century Vienna. “I needed a short break from Omar Yussef to refresh myself,” he says.

In The Fourth Assassin (Soho Press), Rees set the action in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, an area with a growing expatriate Palestinian community, to help American readers “understand the reality of the Muslim minorities living among them.”

A fifth novel will probably unfold in the Old City of Jerusalem and will be the first to include Israeli characters. Rees purposely kept Israelis out of the previous books in which the numerous instances of kidnapping, extortion and murder are almost all committed by Palestinians against other Palestinians. “Part of my goal is to show it is not enough for the Palestinians to say ‘We’re the victims,’” he says. “Palestinians have to take some responsibility. That is what Omar Yussef stands for. When the police won’t solve a murder, Yussef feels he has to do it.”

How long can the series go on? “As long as the publishers want more,” he says, smiling hopefully. “I would like to take Omar throughout the Arab world.

“It’s not difficult to come up with the stories,” he continues. “Palestinians keep giving me material by killing each other and by moving from one disaster to another,” he adds, sounding much like his ever-acerbic but still optimistic Omar Yussef.

Profile: Hadassah Magazine October 2009 Matt Beynon Rees By Leora Eren Frucht

Only gritty, dark crime fiction could evoke the corruption—and hope—in Palestinian society, believes one former foreign correspondent, now a best-selling mystery writer.

The morning sun streams through the windows that frame the Mount of Olives to the east and the hills of Bethlehem to the south. Photographs of a smiling mother and baby flash, one after the other, on a computer screen. The only sign of anything sinister in this cheerful room is the stainless-steel dagger lying in its open, velvet-trimmed case on the desk.

It is here, in this modest fifth-floor apartment in the southern Jerusalem neighborhood of San Simon, that plans for diabolical schemes of extortion, brutal torture and gruesome murders have been concocted.

With a swift motion, a tall, fair-skinned man grabs hold of the dagger. His piercing pale blue eyes sparkle with anticipation as he turns the shiny weapon slowly in his hands.

“It really is amazing,” he says with a satisfied grin, then adds, in a faint Welsh accent, “I never imagined that it would all go so well.”

Meet Matt Beynon Rees, winner of the The Crime Writers’ Association John Creasey New Blood Dagger and creator of Omar Yussef, literature’s first (and only) Palestinian detective.

Rees, a Welsh-born journalist, won the prestigious British award—an actual dagger, granted to a first-time crime novelist—for his 2007 The Collaborator of Bethlehem (Mariner), in which Yussef makes his debut.

Since then, the affable and trim Rees has cast the stocky, ex-alcoholic Yussef as the star of two more detective novels set in Gaza and Nablus respectively (A Grave in Gaza, Mariner; and The Samaritan’s Secret, Soho Press), with another—The Fourth Assassin—due out in February. The books have been published in 22 countries, earning lavish praise from critics; French daily L’Express dubbed Rees “The Dashiell Hammett of Palestine.”

The novels are more than just well-crafted whodunits. Rees uses Yussef to shine a light on Palestinian society, exposing the traditions, tensions and ties that determine how people act. The reader is led through the squalid refugee camps of Gaza, opulent palaces of corrupt Palestinian power brokers and the alleyways of Nablus’s casbah, which fill with the aroma of knafeh pastry and cardamom by day and empty out at night, when only gunmen prowl its premises. Rees paints a raw, revealing and, at times, alarming portrait of Palestinian society.

“We all think we know Palestinians, whichever stereotype we choose to ascribe to them—victims or terrorists. I want to show that we don’t know them at all,” says Rees, 42. He is sipping an espresso in the study of the apartment he shares with his American-born wife, Devorah Blachor (currently working on her first mystery novel), and their 2-year-old son, Cai (the name means “rejoice” in Welsh).

Rees grew up in a nonreligious Protestant home in Cardiff, South Wales, and says he never imagined he would end up in Jerusalem, let alone become an award-winning mystery writer and documenter of Palestinian reality. The only connection he had to the region are two great-uncles, both coal miners, who fought in General Edmund Allenby’s Imperial Camel Corps, which arrived in Jerusalem in 1917. “Both were injured,” he says. “One had his finger bitten off by a Turk. The other, whom I recall from my childhood, used to get drunk on Christmas, drop his pants and show us the scar where he got shot, in Betunia, which was near Ramallah. You could say my fascination with the region began there,” quips Rees. He pays homage to them in his second book, in which a British war cemetery in Gaza features prominently.

Like his camel-cavorting ancestors, Rees landed in Israel by chance. After studying English language and literature at Oxford, he completed a degree in journalism at the University of Maryland and covered Wall Street for five years, a period he recalls with little enthusiasm. When his American fiancée got posted as a foreign correspondent in Jerusalem, Rees joined her. The two married and subsequently divorced, with Rees remarrying a few years later. But his path was set. He, too, began working as a Jerusalem-based foreign correspondent, first for The Scotsman, then for Newsweek; in 2000, he became Middle East bureau chief for Time magazine.

If Wall Street had dulled his senses, covering the Palestinian beat heightened them: “I felt so alive, everything was so exotic to me—the sights, the sounds. I love the dirt and the dust and the way people speak to each other.”

Rees soon realized that much of what intrigued him about Palestinian society was beyond the scope of traditional journalism. But, he says, “If it didn’t mention the peace process, it wasn’t of interest to my editors.

“Most journalists are really political scientists: They want to write about the peace process and interview the prime minister,” he continues. “I don’t really care about that. I’ve always felt more like an anthropologist. I’m more interested in how people live their lives, what they eat, how their culture shapes them.” To that end, Rees learned basic Hebrew and Arabic.

“Matt has an old-fashioned reporter’s empathy that enables readers to know what his subjects are thinking—without the sheen of postmodern cynicism that characterizes so many foreign correspondents,” says Matthew Kalman, a Jerusalem-based freelance foreign correspondent who has worked with Rees. “[He:] realized early on that reporting the Palestinian-Israeli conflict is extremely superficial…. Most of the foreign media is only interested in a cowboys and Indians story.”

In 2004, Rees published a highly acclaimed nonfiction account of Israeli and Palestinian society entitled Cain’s Field: Faith, Fratricide, and Fear in the Middle East (Free Press), but felt that his effort was not adequate. “I think people want to read about the Middle East, but not in a starchy, nonfiction tone,” he notes.

Rees decided to try his hand at a novel. The Collaborator of Bethlehem was inspired by a specific incident: the cold-blooded killing of one Palestinian by another, a militia man, who accused his victim of collaborating with Israel—knowing full well that the man was innocent.

“The dirtiness of the story made me think it’s so complex that only in a novel can you get those shades of gray, in terms of people’s motivations,” says Rees, who had been dabbling in fiction since childhood. “And it had to be a crime novel because it’s a real gangster reality—not a place for a romance novel.” So, in 2006, after selling the rights to the book, Rees quit Time to write fiction full-time.

Fiction, that is, to a point. The mystery series is based, in part, on actual events and people, including Yussef, a 56-year-old history teacher at a United Nations-administered girls’ school in the Dehaisha refugee camp south of Bethlehem. The pudgy, often breathless grandfather (whose favorite granddaughter builds him a Web site for The Palestine Agency for Detection) is no suave sleuth, but a kind of accidental hero. Driven by a deep sense of integrity, he seeks the truth and tries to fight growing corruption and violence in the West Bank and Gaza Strip—often at considerable personal risk.

“Yussef is based on a friend who lives in Dehaisha refugee camp whom I have known for over 10 years,” says Rees. “He is very much like the character in the book—quite acerbic and very intelligent. He gets very frustrated seeing how corruption and criminality are destroying a society that he loves very much.”

Are there many Omar Yussefs in Palestinian society?

“There are many who have the same basic discontents about the corruption and violence,” he says, “but there are not that many who take action because most feel trapped.” In a telling example of this, in one novel, a man who protests the use of his rooftop to shoot at Israelis meets an untimely fate. “But there are Palestinians who are trying to change things in very small ways,” Rees continues, adding a note of optimism: “I made Omar a teacher because he represents the possibility that the next generation will be different.”

Jamil Hamad, Time’s veteran Palestinian correspondent, says that several Palestinians have shared with him their respect for Rees’s depiction of their society. “I have received calls from other Palestinians here,” Hamad says, “and from Arabs in Jordan, Syria, Egypt and North Africa who say they are very grateful to him for painting a realistic portrait of Palestinians and are proud of the books.”

Yussef’s adversaries—ruthless heads of militias and security forces, weapons smugglers and crooked politicians—make for a colorful cast of bad guys based on real people whom Rees got to know while researching his novels and during his journalistic days. Military Intelligence Chief General Husseini, a character in A Grave in Gaza, is renowned for his particular method of torture: slicing off the tips of prisoners’ fingers. The person and method are real, though the name given to the style of torture—a Husseini manicure—is Rees’s invention.

In researching the novels, Rees spent entire days and nights hanging out with gunmen, most of whom have since been killed—either by Israeli forces or by other Palestinians. Nearly all of them lived with the knowledge that a violent death was imminent.

“It is almost as though they are ghosts when they are alive,” he says. “It feels eerie to have met someone who was as good as dead anyway.”

And because his sinister types are based on portraits of real individuals, he believes that he is able to present complex, nuanced antagonists, rather than cartoon “bad guys.”

“I feel like if you’re a writer and you can ‘know the minds of many men,’ you can tell their story as though it was emerging from your own emotions,” explains Rees, quoting The Odyssey.

“When I was in a refugee camp in the middle of the night, talking to people from Hamas and Fatah who expected to die at any moment, I think I got some insight into the minds of many men,” concludes Rees, whose neutral foreign looks and identity helped him gain access to his subjects and win their trust.

“I think through these novels he is reporting the conflict in a different and exceptional way,” says Hamad. “He’s not just writing a novel—he’s reporting the story. Matt is one of the few journalists I work with who is always capable of ‘digesting’ it properly, meaning he has no illusions.”

Rees’s literary heroes are the classic detective writers Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. “I love the gritty realism, but I also love the way in which Chandler writes,” he says. “I think he is the greatest stylist of American literature.”

That gritty realism is a hallmark of the Omar Yussef series, which is littered with corpses but also boasts more subtle touches like a swarm of flies that follows the protagonist throughout his sojourn through the filth—both material and moral—of Gaza.

Rees’s own life is a sharp contrast from that of his characters. Every morning, he does a few yoga stretches and writes standing up for several hours at his raised computer terminal. He swims, works out, does Pilates and meditation. He also plays bass in a local band and delights in his toddler son. “I feel younger all the time,” he says happily. He is currently learning piano as part of the research for his new historical novel that evolves around the musical scene in 19th-century Vienna. “I needed a short break from Omar Yussef to refresh myself,” he says.

In The Fourth Assassin (Soho Press), Rees set the action in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, an area with a growing expatriate Palestinian community, to help American readers “understand the reality of the Muslim minorities living among them.”

A fifth novel will probably unfold in the Old City of Jerusalem and will be the first to include Israeli characters. Rees purposely kept Israelis out of the previous books in which the numerous instances of kidnapping, extortion and murder are almost all committed by Palestinians against other Palestinians. “Part of my goal is to show it is not enough for the Palestinians to say ‘We’re the victims,’” he says. “Palestinians have to take some responsibility. That is what Omar Yussef stands for. When the police won’t solve a murder, Yussef feels he has to do it.”

How long can the series go on? “As long as the publishers want more,” he says, smiling hopefully. “I would like to take Omar throughout the Arab world.

“It’s not difficult to come up with the stories,” he continues. “Palestinians keep giving me material by killing each other and by moving from one disaster to another,” he adds, sounding much like his ever-acerbic but still optimistic Omar Yussef.

October 15, 2009

Location, location

Writers live in their heads. What may be travel to you is location-scouting for me. In some ways, I’m never where I am. I’m imagining that place on the page in a future book. It won’t exist until I’ve written about it.

I was standing on a deserted bridge across the Rhine in the Swiss town of Rheinfelden a couple of weeks ago in the evening twilight. The river flowed very fast. The rain was steady. It patterned the field-grey surface of the water in scattered patches, so that it seemed as though the current slid beneath thin sheets of slow-moving, melting ice.

A woman went by on a bicycle, its tires making a subdued splatter in the puddles. Along one bank, a row of medieval buildings backed onto the river, overhanging it like the brighter constructions of Florence leaning toward the Arno. Somewhere on the other bank, a train went by. In the middle of the river, the 100-year-old bridge touched the head of a small wooded island. I went into the stand of pines.

“This is where they’ll meet,” I thought.

I don’t yet know who “they” are. I know that one of them is my father. Will be my father. I have in mind a plot, you see, for a thriller set in Italy and quiet points north. With the main character based on my father, who did secret work for the British government when I was growing up and traveled frequently in such places.

I don’t yet know quite how that plot will play out. In many respects, the places I find will build the plot for me. They’ll give me exciting spots that are spurs to action scenes. They’ll show me clandestine places that demand secret meetings. They’ll lead me to introspective moments for my characters.

Novels have to bubble like this for years. Just because I’m writing a book a year doesn’t mean that’s how long a book takes. Each of my Palestinian crime novels is based on ideas that fermented over more than a decade as a foreign correspondent here in Jerusalem. The novel I just shipped off to my agent, which is set in central Europe in 1791, was a seed planted in conversations with my wife while we traveled in Austria and the Czech Republic in 2003.

When my second novel, “A Grave in Gaza”, was published, people asked me if I’d been to Gaza especially for the book. Well, I made a couple of return trips to check that I remembered locations correctly. But I’d been in Gaza at least a few days a month – often more – for 11 years, by the time I wrote that book in 2006. If I hadn’t, a few days or even weeks scouting around Gaza wouldn’t have been enough.

Sometimes I see this fictionalizing of the reality around me as a psychological flaw. On the island in the Rhine, I might just as easily have thought “Oh, how peaceful. How lucky I am to be traveling at someone else’s expense in places I’d never otherwise have been. How wonderful that this is called work, that I can feel a creative surge here in this place.” I might also have looked at my watch and thought, “I’m lonely. At home now it’ll be the boy’s bathtime. Soon he’ll be in bed.”

I thought all of those things. But they won’t put words on the page or bread on the table.

I wandered up the main street of old Rheinfelden, cobbled and slick and empty. I stopped into a men’s store and bought a lightweight, blue raincoat.

“This is what he’ll wear.”

Back to the Hotel Schuetzen. I ate two little round steaks of Seeteufel. The frothy yellow vinegar sauce on the fish was one of the most delicious things I’ve ever tasted. I almost thought, “This is what he’ll eat.” But the character I envisage will be on a British government salary, so he’ll have to be a little more frugal. I was pleased, instead, to think: “This is the life, Matthew, my boy. This is the bloody life.”

(I posted this earlier today on the International Crime Authors Reality Check blog.)

I was standing on a deserted bridge across the Rhine in the Swiss town of Rheinfelden a couple of weeks ago in the evening twilight. The river flowed very fast. The rain was steady. It patterned the field-grey surface of the water in scattered patches, so that it seemed as though the current slid beneath thin sheets of slow-moving, melting ice.

A woman went by on a bicycle, its tires making a subdued splatter in the puddles. Along one bank, a row of medieval buildings backed onto the river, overhanging it like the brighter constructions of Florence leaning toward the Arno. Somewhere on the other bank, a train went by. In the middle of the river, the 100-year-old bridge touched the head of a small wooded island. I went into the stand of pines.

“This is where they’ll meet,” I thought.

I don’t yet know who “they” are. I know that one of them is my father. Will be my father. I have in mind a plot, you see, for a thriller set in Italy and quiet points north. With the main character based on my father, who did secret work for the British government when I was growing up and traveled frequently in such places.

I don’t yet know quite how that plot will play out. In many respects, the places I find will build the plot for me. They’ll give me exciting spots that are spurs to action scenes. They’ll show me clandestine places that demand secret meetings. They’ll lead me to introspective moments for my characters.

Novels have to bubble like this for years. Just because I’m writing a book a year doesn’t mean that’s how long a book takes. Each of my Palestinian crime novels is based on ideas that fermented over more than a decade as a foreign correspondent here in Jerusalem. The novel I just shipped off to my agent, which is set in central Europe in 1791, was a seed planted in conversations with my wife while we traveled in Austria and the Czech Republic in 2003.

When my second novel, “A Grave in Gaza”, was published, people asked me if I’d been to Gaza especially for the book. Well, I made a couple of return trips to check that I remembered locations correctly. But I’d been in Gaza at least a few days a month – often more – for 11 years, by the time I wrote that book in 2006. If I hadn’t, a few days or even weeks scouting around Gaza wouldn’t have been enough.

Sometimes I see this fictionalizing of the reality around me as a psychological flaw. On the island in the Rhine, I might just as easily have thought “Oh, how peaceful. How lucky I am to be traveling at someone else’s expense in places I’d never otherwise have been. How wonderful that this is called work, that I can feel a creative surge here in this place.” I might also have looked at my watch and thought, “I’m lonely. At home now it’ll be the boy’s bathtime. Soon he’ll be in bed.”

I thought all of those things. But they won’t put words on the page or bread on the table.

I wandered up the main street of old Rheinfelden, cobbled and slick and empty. I stopped into a men’s store and bought a lightweight, blue raincoat.

“This is what he’ll wear.”

Back to the Hotel Schuetzen. I ate two little round steaks of Seeteufel. The frothy yellow vinegar sauce on the fish was one of the most delicious things I’ve ever tasted. I almost thought, “This is what he’ll eat.” But the character I envisage will be on a British government salary, so he’ll have to be a little more frugal. I was pleased, instead, to think: “This is the life, Matthew, my boy. This is the bloody life.”

(I posted this earlier today on the International Crime Authors Reality Check blog.)

US unhappy over Hamas-Fatah deal

The planned agreement goes some way toward validating Hamas control of the Gaza Strip. By Matt Beynon Rees - GlobalPost

RAMALLAH, West Bank — Warring Palestinian factions Hamas and Fatah have drafted an agreement to end their two-year civil war. But U.S. diplomats oppose the deal. Here’s why.

The planned agreement, a copy of which GlobalPost obtained from senior Palestinian officials this week, goes some way toward validating Hamas control of the Gaza Strip. The 25-page document in Arabic also orders Palestinian security forces, currently being trained by a U.S. general, to “respect the right of the Palestinian people to resist and to defend the homeland and the citizens,” suggesting that attacks against Israeli targets won’t be countered.

The agreement could be a major setback to the Obama administration’s attempt to get recalcitrant Israeli and Palestinian negotiators back into peace talks. Israel is not likely to strike a deal with Fatah if it believes its "partners" in the "peace process" are making nice to Hamas.

The measures laid out in the document suggest Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas has succumbed to recent domestic pressure over his handling of a U.N. report critical of Israel’s tactics in the war in Gaza at the turn of the year. Abbas was criticized for dropping plans to push for hearings against Israel at the International Court of Justice in The Hague over the U.N. report. He has revived those plans, but now also risks a confrontation with the U.S. over a deal that concedes much ground to the Islamist party.

Fatah officials say they signed the agreement already this week, though they added that the text of the deal hasn’t been made public. Hamas has yet to sign the document. By Oct. 25, according to the document, Abbas will ink an order scheduling elections for June next year.

Hamas drove Abbas’s Fatah faction out of the Gaza Strip by force of arms in spring 2007, when the Islamist party also controlled parliament and the prime minister’s post. Since then, Abbas has ruled from Ramallah with a prime minister Hamas says is illegitimate. Both sides have tortured opponents and, according to human rights groups, Hamas has murdered Fatah supporters in Gaza. (The text obtained by GlobalPost includes provisions for the release of political prisoners by both sides.)

The tension between the two factions has been a factor in the stalled peace talks with Israel. The U.S. has pushed for a deal that would end the civil conflict, though Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said in Ramallah earlier this year that any agreement must not allow Hamas a role in Palestinian government. Since Fatah was driven out of Gaza, it has paid wages to government workers there, but ordered them to stay at home.

In repeated negotiations under the auspices of the United States' Egyptian allies, Fatah appears now to have conceded a governing role to Hamas. The agreement calls for a “joint committee” to act as a transitional government over the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. The committee would be staffed by Fatah and Hamas officials.

That would probably mean government workers in Gaza would go back to their desks, working under Hamas rule — something the U.S., which along with the European Union pays much of their salaries, opposes.

The agreement calls for “a culture of tolerance, affection and reconciliation.” Before signing the deal, Abbas slipped in some less than affectionate rhetoric about Hamas Tuesday in Jenin. He called Hamas’s Gaza Strip an “Emirate of Darkness.”

The newly decreed tolerance doesn’t seem to extend to Israel either. Resistance to Israel’s occupation must be respected by Palestinian security forces, the document says.

That won’t sit well with General Keith Dayton, the U.S. adviser who has transformed the Palestinian security forces over the last year. Israeli military chiefs acknowledge that cooperation with Palestinian troops has never been better and have consequently removed a number of checkpoints on key West Bank arteries.

The proposed agreement appears to turn back the clock to the days of Yasser Arafat’s regime in the 1990s, when senior Palestinian security officials were never quite sure if they were supposed to arrest militants — to protect the peace agreement with Israel — or let them engage in valid “resistance” against Israeli targets. Under such circumstances, Israel’s newfound confidence in the Palestinian security forces would be dented and Dayton’s good work would be set back.

U.S. Mideast envoy George Mitchell reportedly communicated Washington’s opposition to Egyptian intelligence chief Omar Suleiman over the weekend, according to reports in the Israeli media. The U.S. Embassy was not available for comment on this issue.

However, analysts here concur that the U.S. wouldn’t be likely to oppose all elements of the agreement. In particular the proposals for the elections next year favor Fatah. The number of parliamentary seats selected by proportional representation is to be increased. In the 2006 elections, Hamas won largely because it did well in seats selected by district.

That’s not going to be enough to get Mitchell to buy it. But it may already be too late for him to stop it.

RAMALLAH, West Bank — Warring Palestinian factions Hamas and Fatah have drafted an agreement to end their two-year civil war. But U.S. diplomats oppose the deal. Here’s why.

The planned agreement, a copy of which GlobalPost obtained from senior Palestinian officials this week, goes some way toward validating Hamas control of the Gaza Strip. The 25-page document in Arabic also orders Palestinian security forces, currently being trained by a U.S. general, to “respect the right of the Palestinian people to resist and to defend the homeland and the citizens,” suggesting that attacks against Israeli targets won’t be countered.

The agreement could be a major setback to the Obama administration’s attempt to get recalcitrant Israeli and Palestinian negotiators back into peace talks. Israel is not likely to strike a deal with Fatah if it believes its "partners" in the "peace process" are making nice to Hamas.

The measures laid out in the document suggest Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas has succumbed to recent domestic pressure over his handling of a U.N. report critical of Israel’s tactics in the war in Gaza at the turn of the year. Abbas was criticized for dropping plans to push for hearings against Israel at the International Court of Justice in The Hague over the U.N. report. He has revived those plans, but now also risks a confrontation with the U.S. over a deal that concedes much ground to the Islamist party.

Fatah officials say they signed the agreement already this week, though they added that the text of the deal hasn’t been made public. Hamas has yet to sign the document. By Oct. 25, according to the document, Abbas will ink an order scheduling elections for June next year.

Hamas drove Abbas’s Fatah faction out of the Gaza Strip by force of arms in spring 2007, when the Islamist party also controlled parliament and the prime minister’s post. Since then, Abbas has ruled from Ramallah with a prime minister Hamas says is illegitimate. Both sides have tortured opponents and, according to human rights groups, Hamas has murdered Fatah supporters in Gaza. (The text obtained by GlobalPost includes provisions for the release of political prisoners by both sides.)

The tension between the two factions has been a factor in the stalled peace talks with Israel. The U.S. has pushed for a deal that would end the civil conflict, though Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said in Ramallah earlier this year that any agreement must not allow Hamas a role in Palestinian government. Since Fatah was driven out of Gaza, it has paid wages to government workers there, but ordered them to stay at home.

In repeated negotiations under the auspices of the United States' Egyptian allies, Fatah appears now to have conceded a governing role to Hamas. The agreement calls for a “joint committee” to act as a transitional government over the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. The committee would be staffed by Fatah and Hamas officials.

That would probably mean government workers in Gaza would go back to their desks, working under Hamas rule — something the U.S., which along with the European Union pays much of their salaries, opposes.

The agreement calls for “a culture of tolerance, affection and reconciliation.” Before signing the deal, Abbas slipped in some less than affectionate rhetoric about Hamas Tuesday in Jenin. He called Hamas’s Gaza Strip an “Emirate of Darkness.”